Inquiry Cycle

Explore inquiry cycles in education. Engage students with real-world problems as they ask questions, gather information, and present their findings effectively.

Explore inquiry cycles in education. Engage students with real-world problems as they ask questions, gather information, and present their findings effectively.

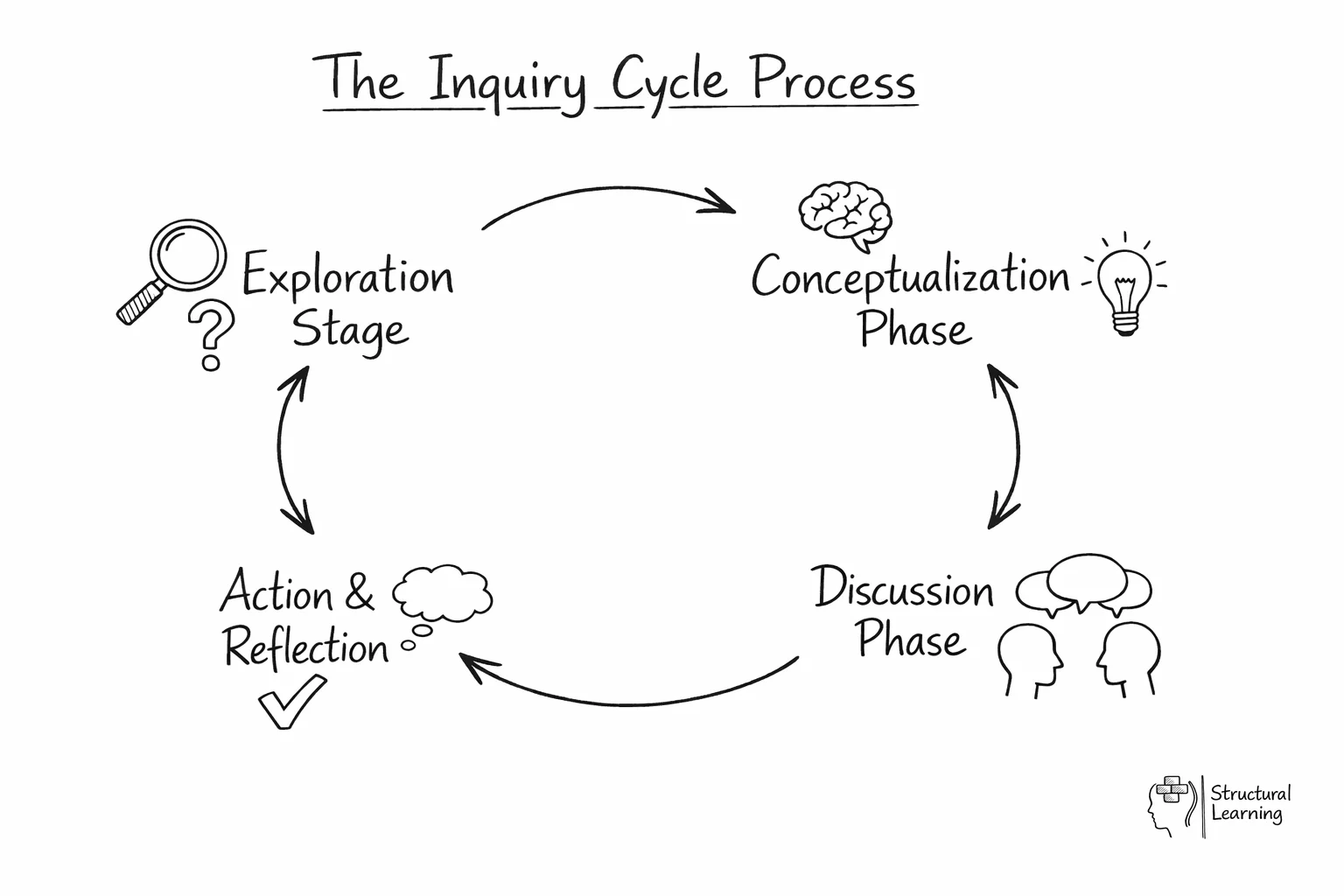

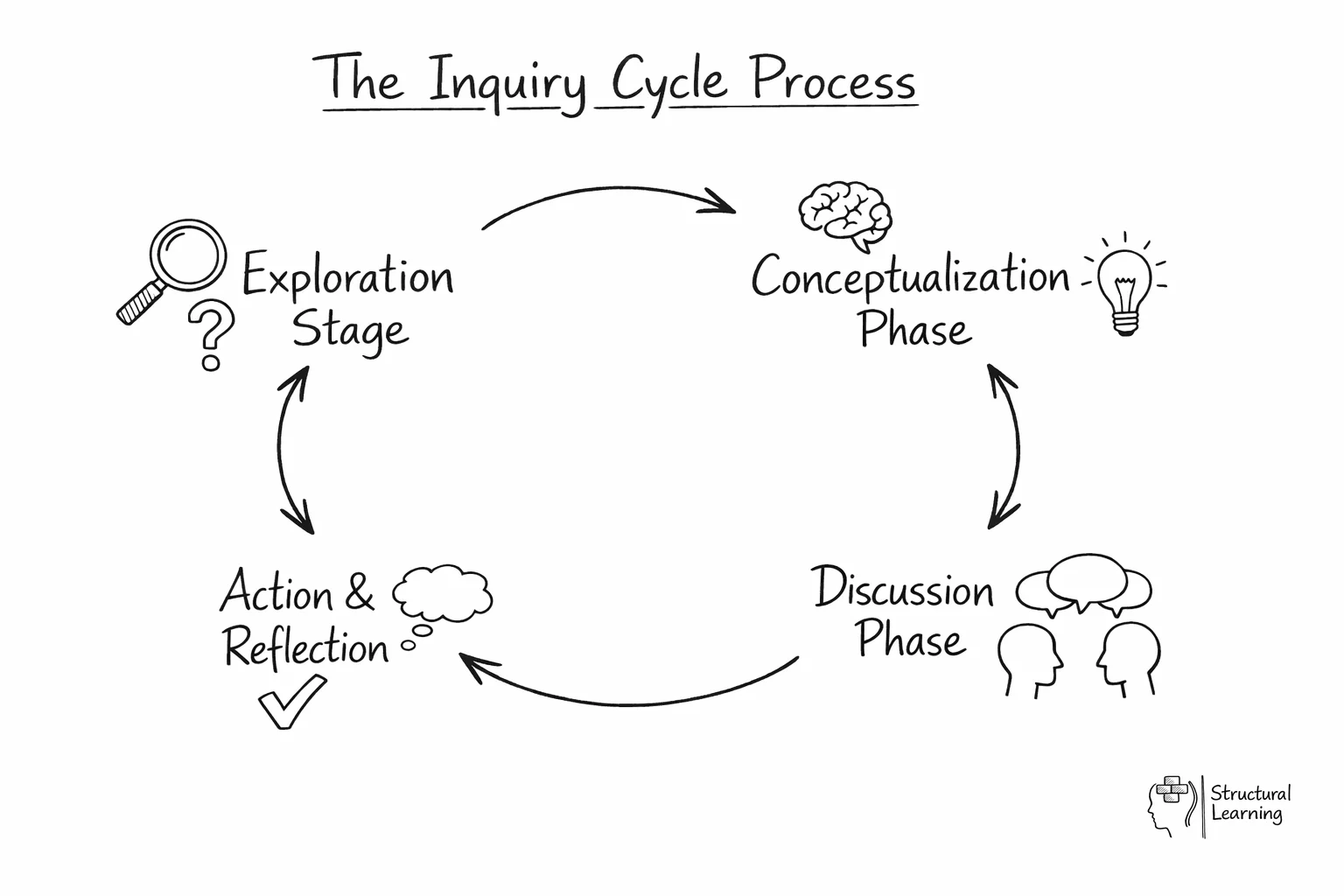

Inquiry is a process of learning that is active, helping and ongoing. It can be viewed as a process, cyclical, not necessarily linear yet structured and iterative. Inquiry learning is designed to tap into a young person's curiosity and creativity as it encourages them to view their learning through a conceptual lens.

It is devised in ways that allow young people to take action and lead their learning through actively participating in the process. This enables young people to shift from passive to active learning as they are encouraged to ask questions, look into issues and solve problems using real-world situations and scenarios.

The educator creates environments for the learner to understand the why and how as well as the what. The learner is therefore provided with opportunities to collaborate, self-manage, self-reflect, investigate, communicate and show independence and confidence when doing so.

Characteristics of inquiry-based learning

Inquiry-based learning features and highlights such things as questioning, researching, creative thinking, critical thinking and solving problems. Learning is centred around the whole child in complete ways and educates them from within. It places the learner at the centre of learning and helps them through a process of inquiry, action and reflection that is ongoing and interactive.

Inquiry is very well suited to concept-based approaches. The marriage it creates can be a powerful experience for a learner in ways that allow for higher cognitive thinking skills to be utilised through inquiry. This also will increase the learner's engagement.

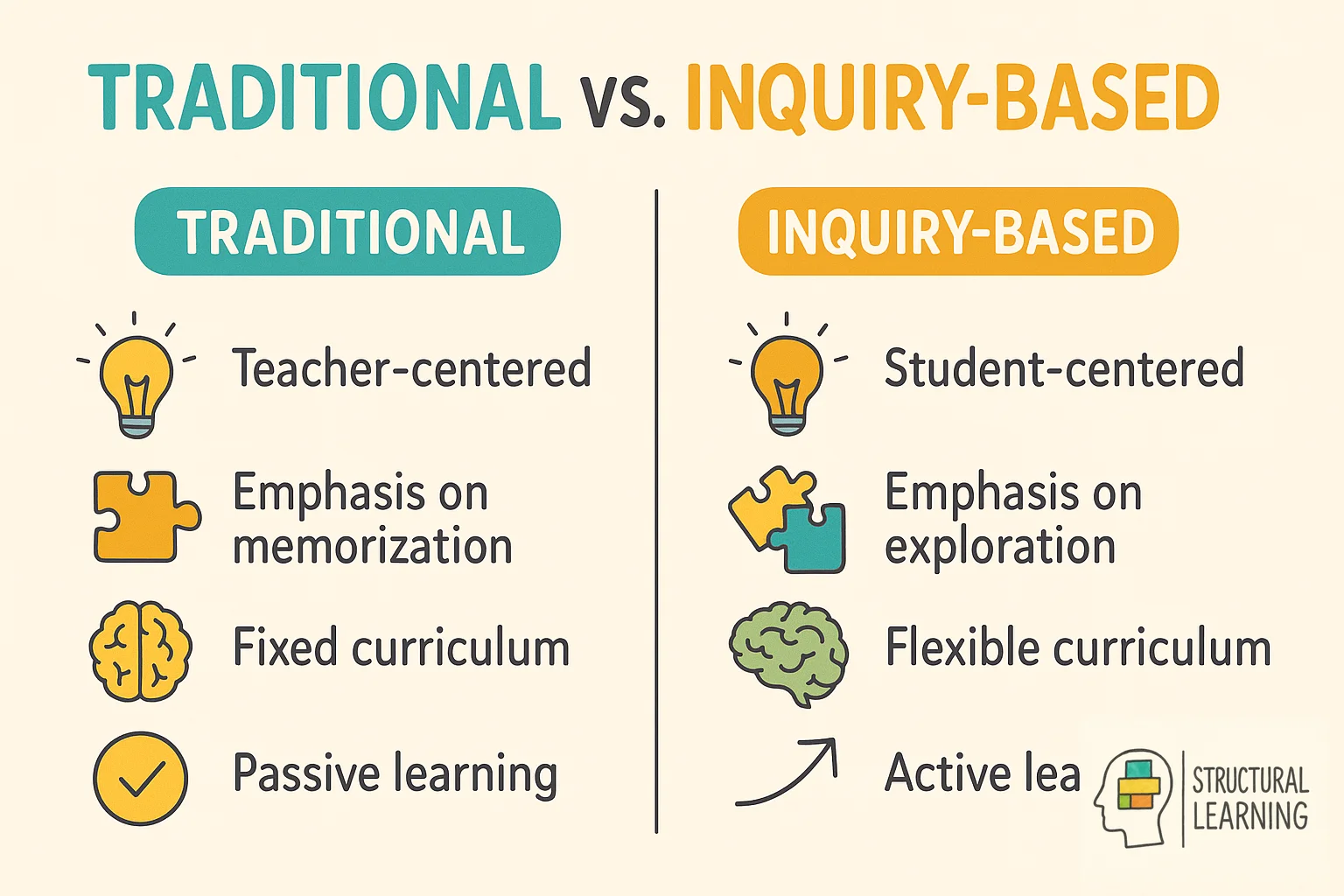

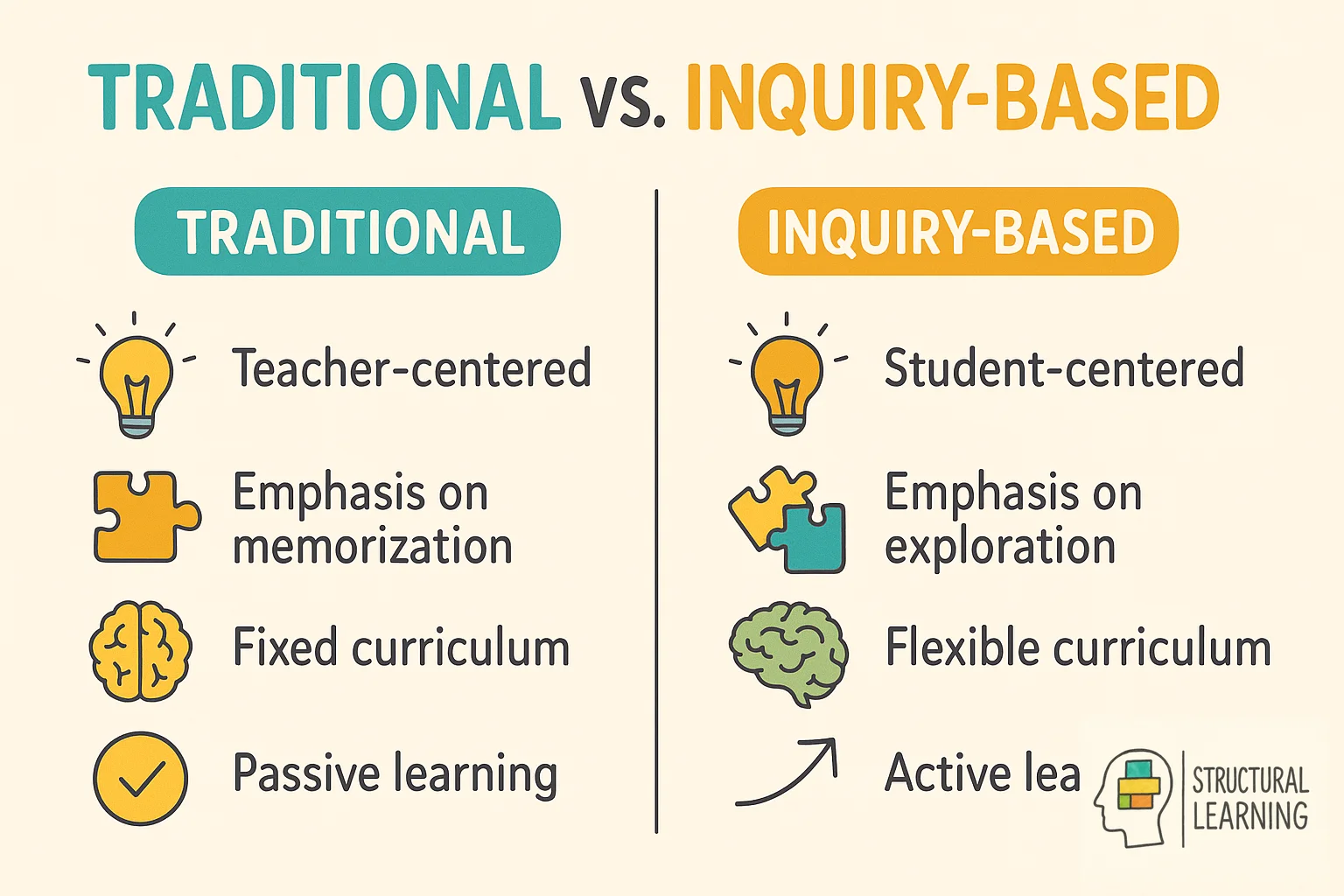

This is not to say that students do not search for facts and use various skills to do so when using more traditional teaching methods which have value but this alone is not enough. The learner should have opportunities to investigate through inquiry that is beyond facts by delving deeper using higher-order thinking and questioning to reach a conceptual understanding.

Inquiry-based learning is a modern pedagogical approach practised by many educators. Within the International Baccalaureate programmes, Inquiry-Based learning and Concept-Based Approaches are integrated within their programmes. The educator puts inquiry into use, by guiding the learners. They will introduce concepts through a Statement of Inquiry and relate these to topics by posing broad questions as well as providing opportunities for the learner to pose their questions that will shape their inquiry. This in turn creates more student-centred learning that puts the learner at the centre.

All aspects of the process are connected and aligned. This allows the learner to have a voice and choice during the process of investigating and when presenting their findings. Problems might arise, in a traditional classroom environment which is modelled on content and skills alone and where the educator could be doing all the thinking for the learner. It might even be the case that they are working harder than the learner as the learning is heavily teacher-centred.

Inquiry-based learning (IBL) offers a robust framework for developing student engagement and motivation. By integrating the Cycle of Inquiry into the learning process, educators can create dynamic environments that encourage questioning, probing, and deep exploration. Here, we explore the core features and impacts of IBL, focusing on the phases of inquiry and their benefits to student learning.

Inquiry-based learning shifts the educator's role from a traditional lecturer to a facilitator of learning. The teacher becomes a guide, supporting students as they navigate the inquiry cycle. This involves:

By embracing this facilitative role, educators helps students to take ownership of their learning and develop the skills necessary to thrive in a rapidly changing world.

The Inquiry Cycle can be applied across diverse subjects and age groups. Here are a few examples:

While the benefits of inquiry-based learning are clear, implementing it effectively can present challenges. These may include:

To address these challenges, educators can:

By proactively addressing these challenges, educators can successfully implement inquiry-based learning and reap its numerous benefits.

Successfully implementing inquiry cycles within the constraints of the National Curriculum requires strategic planning and flexible approaches that honour both student curiosity and statutory requirements. At Key Stage 1, a Year 2 geography unit on local environments can transform from traditional worksheet activities into genuine inquiry when students generate their own questions about why certain plants grow in their school grounds. Teachers can scaffold this process by providing question stems such as "I wonder why.." or "What would happen if.." whilst ensuring coverage of curriculum objectives around identifying seasonal changes and describing geographical features. Research by Murdoch (2015) demonstrates that even young learners can engage in sophisticated thinking when given appropriate frameworks, with teachers reporting increased engagement and deeper conceptual understanding when inquiry approaches replace transmission-style teaching.

Time management represents one of the most significant challenges teachers face when adopting inquiry-based approaches, particularly given the pressures of SATs preparation and curriculum coverage. The solution lies in integrated inquiry blocks that weave together multiple subjects around compelling questions. A KS2 example might involve Year 5 students investigating "How did the Industrial Revolution change our local area?" which simultaneously addresses history objectives about Britain's settlement by Anglo-Saxons and Scots, geography skills in using maps and fieldwork, and English requirements for researching and presenting information. Rather than allocating separate lessons to each subject, teachers can dedicate two-week inquiry cycles where students spend 90 minutes daily exploring different aspects of their central question, with mini-lessons embedded to teach specific skills as they become relevant to student investigations.

Assessment within inquiry cycles demands a shift from traditional testing towards authentic assessment strategies that capture both process and product. Portfolio-based assessment works particularly well, where students document their learning journey through photographs of investigations, reflective journals, and evidence of their evolving understanding. At KS3, science teachers can implement peer assessment protocols where students evaluate each other's experimental designs against criteria they've helped to establish, developing both scientific thinking and metacognitive skills. The Assessment Reform Group's research emphasises that formative assessment practices, including student self-assessment and goal setting, significantly enhance learning outcomes when integrated into inquiry approaches rather than bolted on afterwards.

Differentiation within inquiry cycles requires careful scaffolding that maintains high expectations whilst providing appropriate support for learners across the ability spectrum. Tiered questioning strategies prove particularly effective, where all students engage with the same central inquiry but access it through different entry points. In a Year 4 mathematics investigation exploring patterns in nature, higher attaining students might investigate Fibonacci sequences in sunflower heads, whilst those requiring additional support focus on identifying and extending simpler repeating patterns in leaf arrangements. Teaching assistants can be trained to facilitate thinking partnerships where students articulate their reasoning to peers, providing natural differentiation as students learn from each other's perspectives whilst developing communication skills valued across the curriculum.

Integration with existing schemes of work becomes smooth when teachers identify the conceptual threads that run through their planned curriculum and use these as the foundation for inquiry questions. A Year 6 unit combining history and English might centre on the concept of "legacy" with students investigating "What legacies did the Ancient Greeks leave us?" This approach allows teachers to maintain their familiar planning structures whilst elevating student engagement and ownership. Professional learning communities within schools can support this transition by collaborative planning sessions where teachers identify natural inquiry opportunities within their existing medium-term plans, sharing successful strategies and troubleshooting challenges together. The key lies in starting small, perhaps with one inquiry cycle per term, building confidence and expertise before expanding the approach across more areas of the curriculum.

The Inquiry Cycle provides a powerful framework for transforming education. By shifting the focus from rote memorisation to active exploration, we can helps students to become critical thinkers, problem-solvers, and lifelong learners. The teacher, in turn, evolves into a guide, nurturing curiosity, developing collaboration, and creating environments where students can thrive.

As educators, embracing inquiry requires a willingness to step outside our comfort zones and trust in the power of student-led learning. While challenges may arise, the rewards are immense: increased student engagement, deeper understanding, and the development of essential skills for navigating an ever-changing world. By incorporating the Inquiry Cycle into our teaching practices, we can cultivate a generation of curious, creative, and confident individuals who are prepared to make a positive impact on the world.

Inquiry is a process of learning that is active, helping and ongoing. It can be viewed as a process, cyclical, not necessarily linear yet structured and iterative. Inquiry learning is designed to tap into a young person's curiosity and creativity as it encourages them to view their learning through a conceptual lens.

It is devised in ways that allow young people to take action and lead their learning through actively participating in the process. This enables young people to shift from passive to active learning as they are encouraged to ask questions, look into issues and solve problems using real-world situations and scenarios.

The educator creates environments for the learner to understand the why and how as well as the what. The learner is therefore provided with opportunities to collaborate, self-manage, self-reflect, investigate, communicate and show independence and confidence when doing so.

Characteristics of inquiry-based learning

Inquiry-based learning features and highlights such things as questioning, researching, creative thinking, critical thinking and solving problems. Learning is centred around the whole child in complete ways and educates them from within. It places the learner at the centre of learning and helps them through a process of inquiry, action and reflection that is ongoing and interactive.

Inquiry is very well suited to concept-based approaches. The marriage it creates can be a powerful experience for a learner in ways that allow for higher cognitive thinking skills to be utilised through inquiry. This also will increase the learner's engagement.

This is not to say that students do not search for facts and use various skills to do so when using more traditional teaching methods which have value but this alone is not enough. The learner should have opportunities to investigate through inquiry that is beyond facts by delving deeper using higher-order thinking and questioning to reach a conceptual understanding.

Inquiry-based learning is a modern pedagogical approach practised by many educators. Within the International Baccalaureate programmes, Inquiry-Based learning and Concept-Based Approaches are integrated within their programmes. The educator puts inquiry into use, by guiding the learners. They will introduce concepts through a Statement of Inquiry and relate these to topics by posing broad questions as well as providing opportunities for the learner to pose their questions that will shape their inquiry. This in turn creates more student-centred learning that puts the learner at the centre.

All aspects of the process are connected and aligned. This allows the learner to have a voice and choice during the process of investigating and when presenting their findings. Problems might arise, in a traditional classroom environment which is modelled on content and skills alone and where the educator could be doing all the thinking for the learner. It might even be the case that they are working harder than the learner as the learning is heavily teacher-centred.

Inquiry-based learning (IBL) offers a robust framework for developing student engagement and motivation. By integrating the Cycle of Inquiry into the learning process, educators can create dynamic environments that encourage questioning, probing, and deep exploration. Here, we explore the core features and impacts of IBL, focusing on the phases of inquiry and their benefits to student learning.

Inquiry-based learning shifts the educator's role from a traditional lecturer to a facilitator of learning. The teacher becomes a guide, supporting students as they navigate the inquiry cycle. This involves:

By embracing this facilitative role, educators helps students to take ownership of their learning and develop the skills necessary to thrive in a rapidly changing world.

The Inquiry Cycle can be applied across diverse subjects and age groups. Here are a few examples:

While the benefits of inquiry-based learning are clear, implementing it effectively can present challenges. These may include:

To address these challenges, educators can:

By proactively addressing these challenges, educators can successfully implement inquiry-based learning and reap its numerous benefits.

Successfully implementing inquiry cycles within the constraints of the National Curriculum requires strategic planning and flexible approaches that honour both student curiosity and statutory requirements. At Key Stage 1, a Year 2 geography unit on local environments can transform from traditional worksheet activities into genuine inquiry when students generate their own questions about why certain plants grow in their school grounds. Teachers can scaffold this process by providing question stems such as "I wonder why.." or "What would happen if.." whilst ensuring coverage of curriculum objectives around identifying seasonal changes and describing geographical features. Research by Murdoch (2015) demonstrates that even young learners can engage in sophisticated thinking when given appropriate frameworks, with teachers reporting increased engagement and deeper conceptual understanding when inquiry approaches replace transmission-style teaching.

Time management represents one of the most significant challenges teachers face when adopting inquiry-based approaches, particularly given the pressures of SATs preparation and curriculum coverage. The solution lies in integrated inquiry blocks that weave together multiple subjects around compelling questions. A KS2 example might involve Year 5 students investigating "How did the Industrial Revolution change our local area?" which simultaneously addresses history objectives about Britain's settlement by Anglo-Saxons and Scots, geography skills in using maps and fieldwork, and English requirements for researching and presenting information. Rather than allocating separate lessons to each subject, teachers can dedicate two-week inquiry cycles where students spend 90 minutes daily exploring different aspects of their central question, with mini-lessons embedded to teach specific skills as they become relevant to student investigations.

Assessment within inquiry cycles demands a shift from traditional testing towards authentic assessment strategies that capture both process and product. Portfolio-based assessment works particularly well, where students document their learning journey through photographs of investigations, reflective journals, and evidence of their evolving understanding. At KS3, science teachers can implement peer assessment protocols where students evaluate each other's experimental designs against criteria they've helped to establish, developing both scientific thinking and metacognitive skills. The Assessment Reform Group's research emphasises that formative assessment practices, including student self-assessment and goal setting, significantly enhance learning outcomes when integrated into inquiry approaches rather than bolted on afterwards.

Differentiation within inquiry cycles requires careful scaffolding that maintains high expectations whilst providing appropriate support for learners across the ability spectrum. Tiered questioning strategies prove particularly effective, where all students engage with the same central inquiry but access it through different entry points. In a Year 4 mathematics investigation exploring patterns in nature, higher attaining students might investigate Fibonacci sequences in sunflower heads, whilst those requiring additional support focus on identifying and extending simpler repeating patterns in leaf arrangements. Teaching assistants can be trained to facilitate thinking partnerships where students articulate their reasoning to peers, providing natural differentiation as students learn from each other's perspectives whilst developing communication skills valued across the curriculum.

Integration with existing schemes of work becomes smooth when teachers identify the conceptual threads that run through their planned curriculum and use these as the foundation for inquiry questions. A Year 6 unit combining history and English might centre on the concept of "legacy" with students investigating "What legacies did the Ancient Greeks leave us?" This approach allows teachers to maintain their familiar planning structures whilst elevating student engagement and ownership. Professional learning communities within schools can support this transition by collaborative planning sessions where teachers identify natural inquiry opportunities within their existing medium-term plans, sharing successful strategies and troubleshooting challenges together. The key lies in starting small, perhaps with one inquiry cycle per term, building confidence and expertise before expanding the approach across more areas of the curriculum.

The Inquiry Cycle provides a powerful framework for transforming education. By shifting the focus from rote memorisation to active exploration, we can helps students to become critical thinkers, problem-solvers, and lifelong learners. The teacher, in turn, evolves into a guide, nurturing curiosity, developing collaboration, and creating environments where students can thrive.

As educators, embracing inquiry requires a willingness to step outside our comfort zones and trust in the power of student-led learning. While challenges may arise, the rewards are immense: increased student engagement, deeper understanding, and the development of essential skills for navigating an ever-changing world. By incorporating the Inquiry Cycle into our teaching practices, we can cultivate a generation of curious, creative, and confident individuals who are prepared to make a positive impact on the world.

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/inquiry-cycle#article","headline":"Inquiry Cycle","description":"Discover the power of inquiry cycles in the classroom. Learn how to engage students with real-world problems, guide them through the process of asking...","datePublished":"2024-06-08T09:39:27.474Z","dateModified":"2026-01-26T10:09:32.212Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/inquiry-cycle"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/69502b28eec84d0e91692ca2_pcneyt.webp","wordCount":3337},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/inquiry-cycle#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"Inquiry Cycle","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/inquiry-cycle"}]},{"@type":"FAQPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/inquiry-cycle#faq","mainEntity":[{"@type":"Question","name":"Why is inquiry important?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Inquiry is very well suited to concept-based approaches. The marriage it creates can be a powerful experience for a learner in ways that allow for higher"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What exactly is an inquiry cycle and how does it differ from traditional teaching methods?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"An inquiry cycle is an active, cyclical learning process that places students at the centre of their education, encouraging them to ask questions, investigate issues, and solve problems using real-world scenarios. Unlike traditional content-focused teaching where students passively receive informati"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"How can teachers practically implement the three phases of inquiry in their classrooms?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Teachers can implement inquiry through the Exploration Stage, Conceptualisation Phase, and Discussion Phase by introducing concepts through a Statement of Inquiry and posing broad questions that guide student investigation. They should create opportunities for students to pose their own questions, w"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What are the main benefits students gain from participating in inquiry-based learning cycles?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Students develop enhanced cognitive processing skills through analysis, evaluation, and synthesis activities that build robust conceptual understanding beyond mere facts and skills. They experience increased engagement and motivation through autonomy and AI-enabled personalised learning experiences,"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What challenges might teachers face when transitioning from traditional to inquiry-based learning approaches?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Teachers may struggle with shifting from being the centre of learning to becoming facilitators, as traditional teacher-centred classrooms often have educators doing more thinking than the students themselves. Creating safe learning spaces where students feel comfortable taking intellectual risks and"}}]}]}