Socratic Teaching Techniques for Effective Learning

Discover effective Socratic teaching techniques to enhance critical thinking and student engagement through open-ended questions and dynamic dialogues.

Discover effective Socratic teaching techniques to enhance critical thinking and student engagement through open-ended questions and dynamic dialogues.

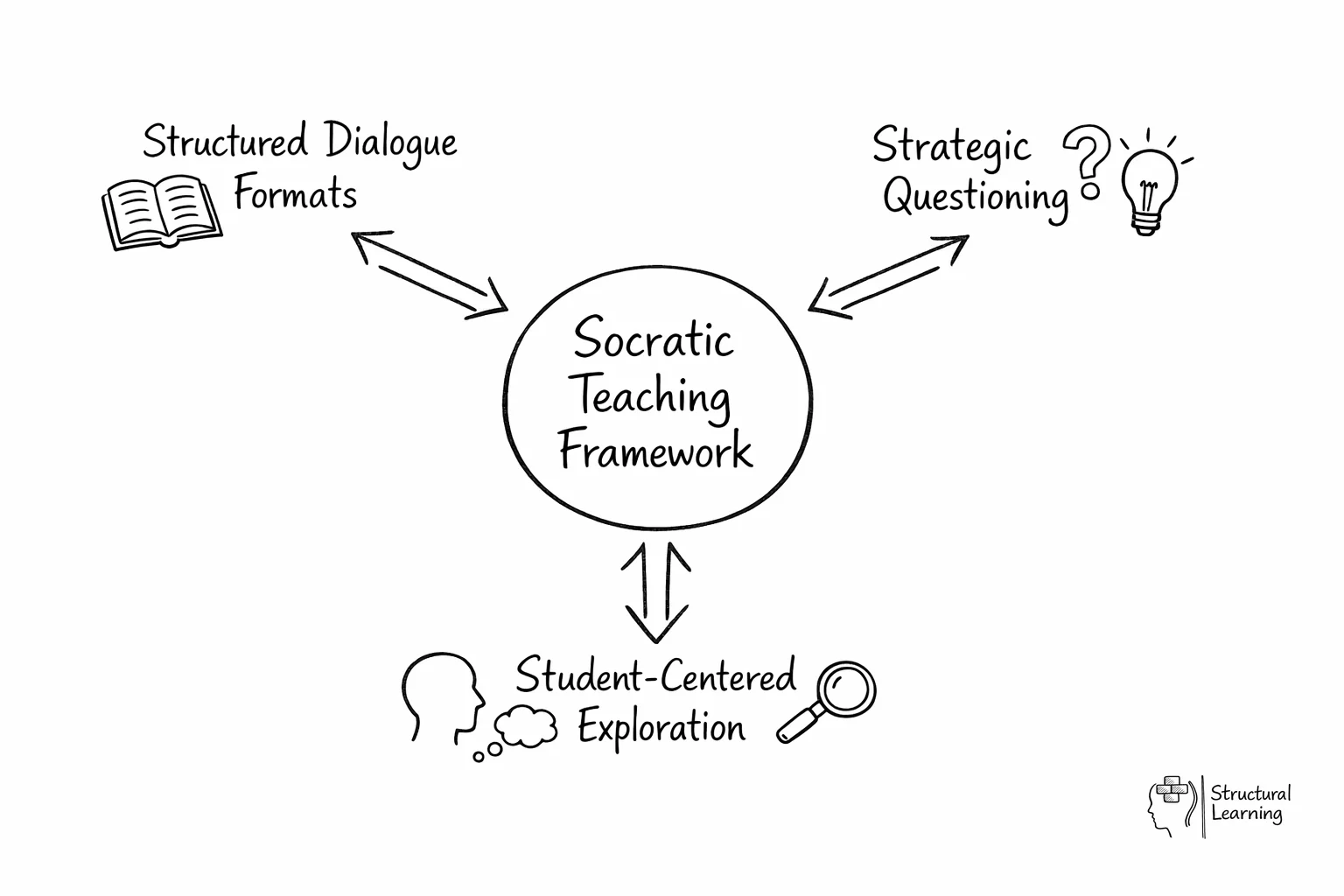

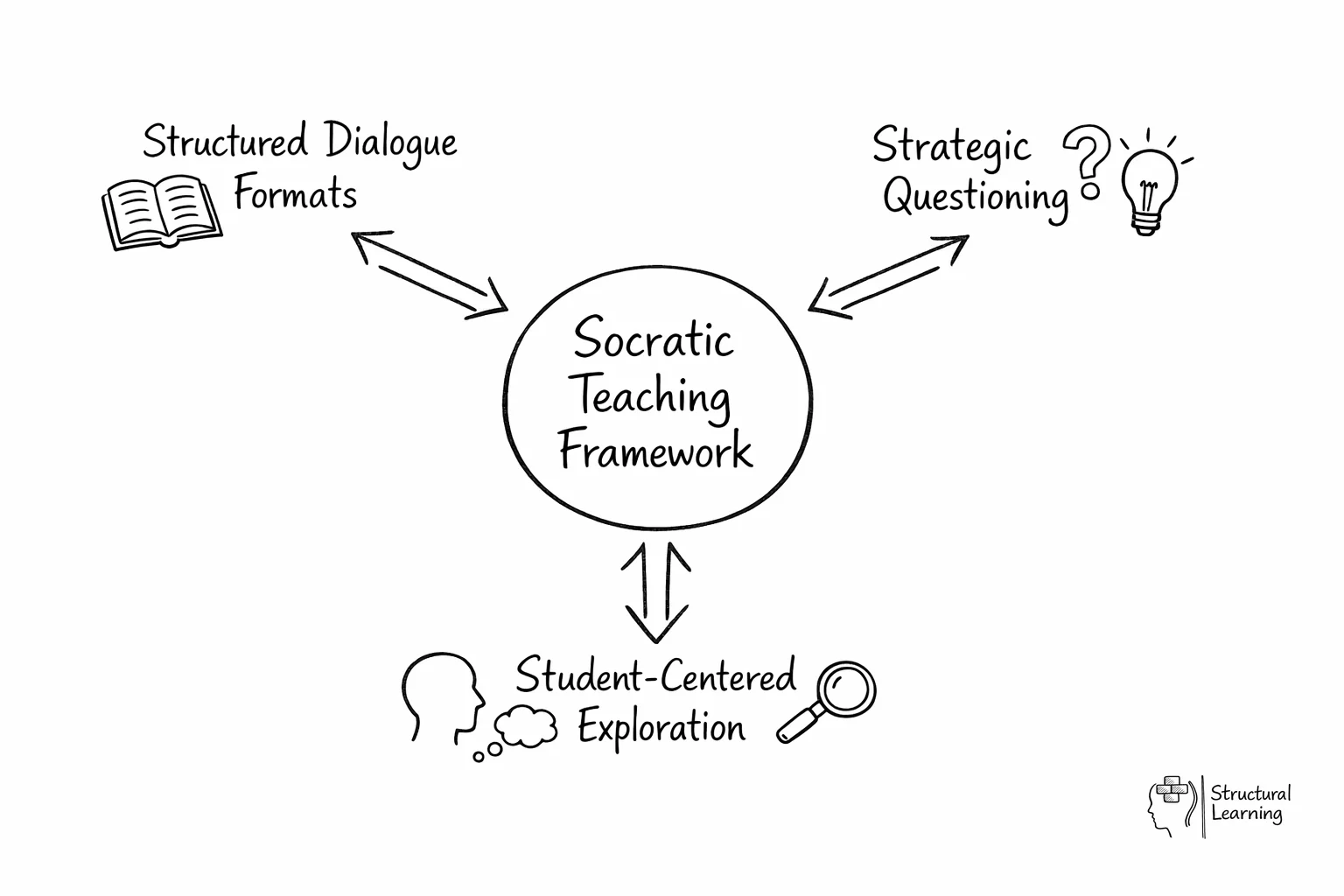

The Socratic Process transforms your classroom into a space for productive discussion. This active learning technique uses well-designed questions to help students examine their thinking and build understanding through dialogue. You ask, students respond, and together you explore ideas that sit beneath surface-level knowledge.

This approach works across wide ranges of subjects and age groups. Students make claims with examples, test their reasoning, and experience productive discomfort as they question what they thought they knew. The method thrives on collaborative inquiry rather than direct instruction.

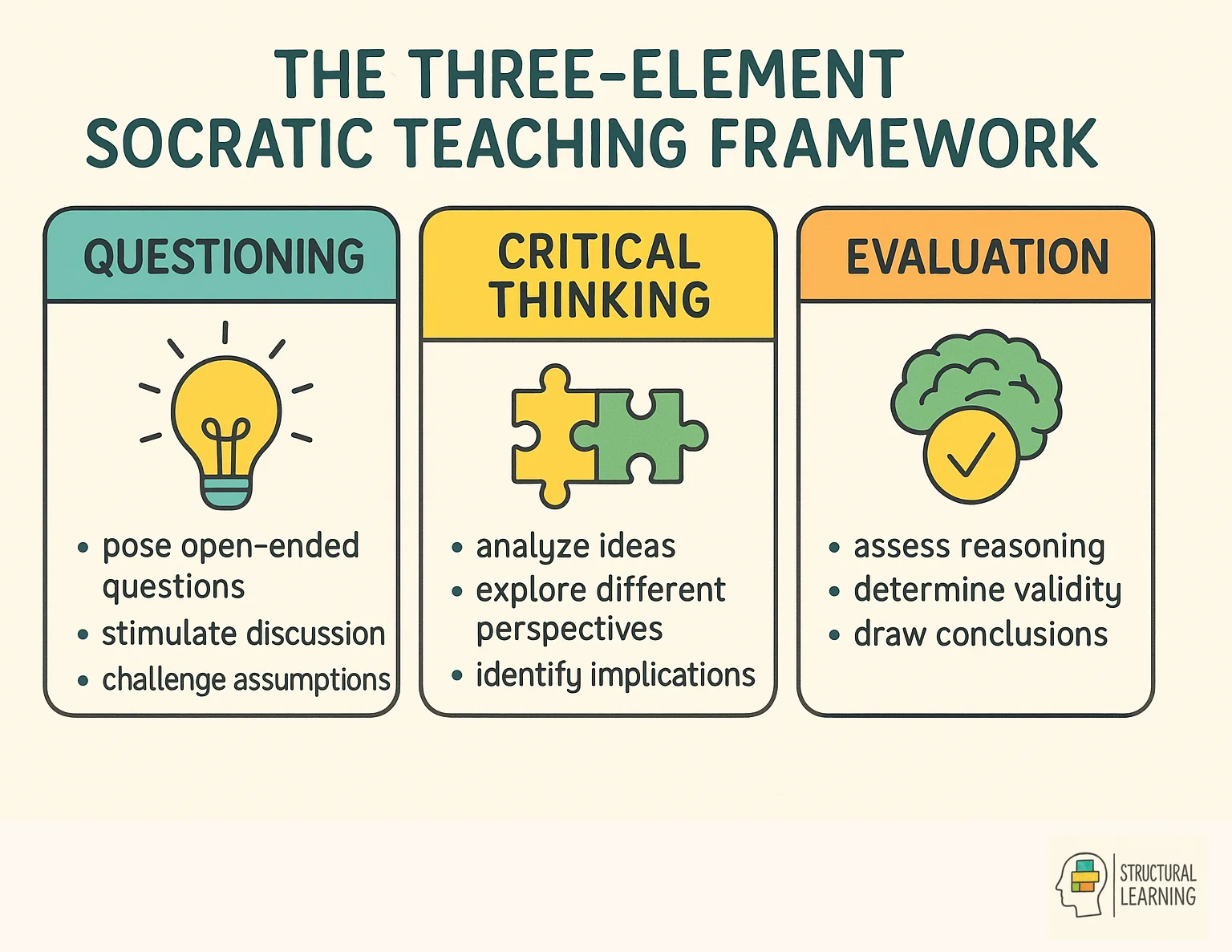

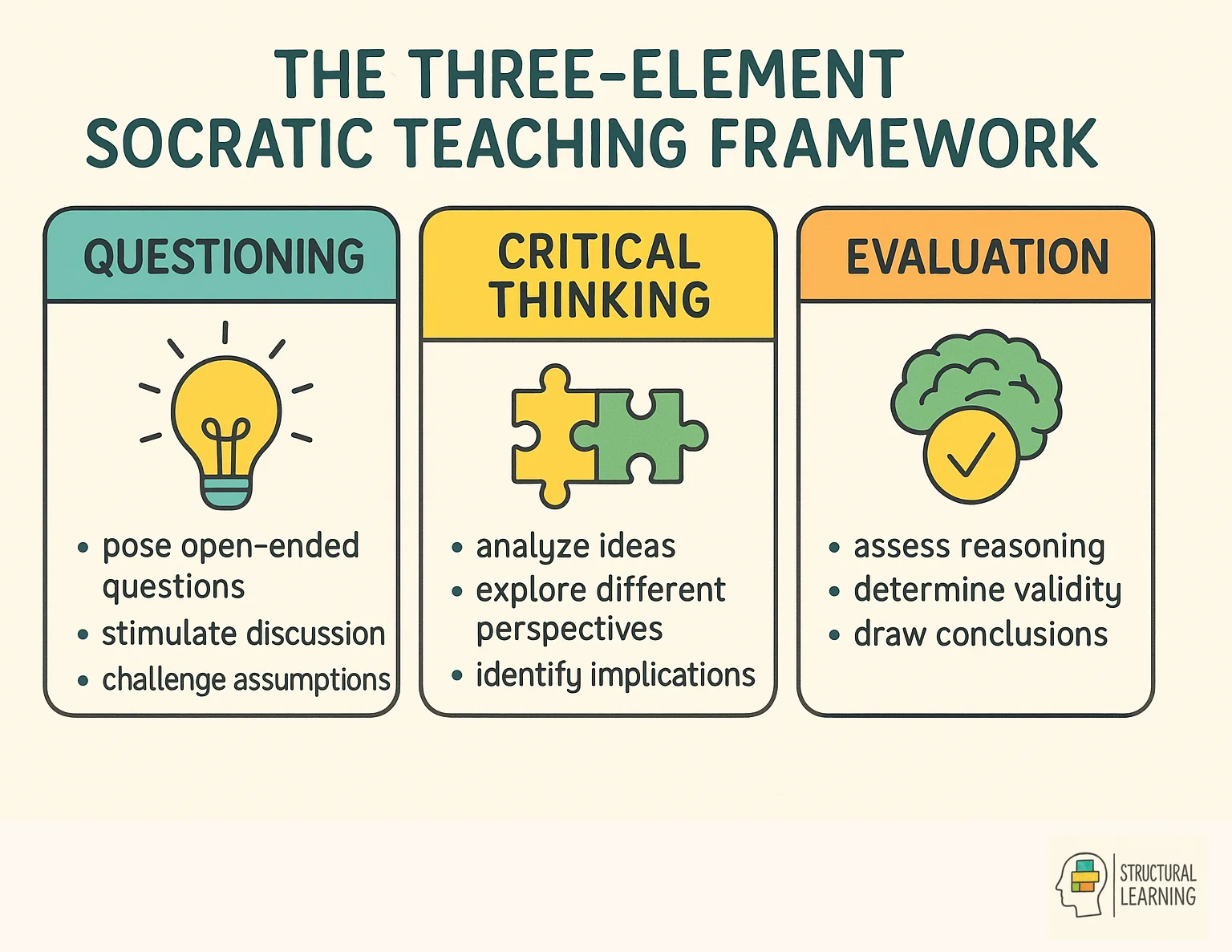

Three key elements make the Socratic Process effective in your classroom:

The technique originated with the Greek philosopher Socrates, who claimed to know nothing but used questioning to expose gaps in others' knowledge. Teachers today apply this method to help students think independently and critically about complex ideas.

Law schools rely heavily on Socratic questioning to sharpen analytical skills, but the method works equally well in primary schools, secondary classrooms, and any setting where you want students to think rather than simply absorb. The process requires patience and practise, yet the payoff comes when students begin asking their own probing questions and taking intellectual risks.

In essence, the Socratic method is a pedagogical approach that encourages students to engage in critical thinking and to discover answers by themselves through a series of methodical and reflective questions. Socratic questioning serves as a powerful tool to dissect complex ideas, explore into assumptions, and break down conceptual frameworks.

In the classroom, this technique prompts students to question their own knowledge and convictions, consequently encouraging intellectual humility and the ability to scrutinize and refine their understanding. Moreover, the role of the teacher in this methodology shifts from being the conveyor of knowledge to a facilitator of dialogue, championing the art of inquiry over simply delivering content.

The process capitalizes on active learning, where students' insights unfold as they articulate responses to carefully crafted questions. Law schools, in particular, often employ this method to sharpen a law student's ability to analyse and argue effectively, evidencing the process's versatility across different fields of study.

The roots of the Socratic Process are firmly planted in the rich soil of ancient Greece, introduced by the philosopher Socrates as a way to challenge and expand the horizons of human understanding. Socrates himself claimed to know nothing, but through his skilled line of inquiry, he prompted those around him to reconsider their beliefs and the extent of their knowledge.

Teachers today bring this historical legacy into their classrooms by adopting Socrates's approach to draw out insights from students through a collaborative and open-ended dialogue. The method resists the notion of spoon-feeding facts; instead, it endeavors to bring forth an individual's innate wisdom and to channel it into a vigor for life-long learning.

This approach has stood the test of time for its effectiveness in promoting critical thinking and for enabling students to take ownership of their intellectual growth.

Russell's philosophy enhances modern teaching by emphasising rigorous questioning and logical analysis, which directly supports educators in implementing more effective Socratic dialogue techniques in contemporary classrooms. Russell's philosophy, centred on the importance of questioning assumptions and underlying beliefs, complements the fundamental objective of the Socratic method, which is to challenge presuppositions and encourage higher-order thinking.

Russell's contributions to the Socratic teaching method emanate from his persistent emphasis on critical thinking and inquiry-based learning. He championed the view that education should not merely be about the absorption of facts, but rather, a process of exploration led by probing questions that challenge existing assumptions and creates independent thought.

In practical classroom applications, Russell's philosophy translates into specific questioning techniques that encourage students to examine the foundations of their beliefs. Teachers can implement his approach by asking students to identify the evidence supporting their initial responses, then probing deeper with questions like "What assumptions are we making here?" or "How might someone with a different perspective view this issue?" This systematic doubt-casting mirrors Russell's analytical method whilst maintaining the supportive environment essential for productive classroom discussions.

Russell's emphasis on intellectual courage also provides a framework for managing the discomfort students often experience when their preconceptions are challenged through Socratic inquiry. Educators can explicitly acknowledge this discomfort as a natural part of learning, helping students understand that questioning familiar ideas strengthens rather than undermines genuine knowledge. By creating classroom cultures where uncertainty is viewed as an opportunity rather than a failure, teachers embody Russell's vision of education as intellectual liberation rather than indoctrination.

Effective Socratic teaching requires careful planning and execution. Here are some practical tips to help you implement this method in your classroom:

While the Socratic method can be incredibly effective, be aware of potential pitfalls:

Extensive research demonstrates that Socratic teaching techniques significantly enhance students' critical thinking abilities and academic outcomes. Studies by educational researchers including Paul and Elder have shown that students exposed to systematic questioning develop stronger analytical skills, with improvements in reasoning capabilities that transfer across subject areas. Additionally, research conducted by Chin and Osborne reveals that classrooms employing Socratic dialogue show increased student participation rates and deeper conceptual understanding compared to traditional lecture-based approaches.

The cognitive benefits extend beyond immediate learning gains. Bloom's taxonomy research indicates that Socratic questioning naturally guides students through higher-order thinking processes, moving from basic recall to analysis, synthesis, and evaluation. Furthermore, studies on classroom engagement consistently show that inquiry-based discussions increase student motivation and retention rates, as learners become active participants rather than passive recipients of information.

In practical terms, educators implementing Socratic methods report measurable improvements in student performance on assessments requiring critical analysis. Research by Fisher and Frey demonstrates that students who regularly engage in structured questioning activities show enhanced problem-solving skills and greater confidence in expressing complex ideas. These evidence-based outcomes provide compelling justification for incorporating Socratic techniques into daily classroom practice across all subject areas.

Assessing student learning during Socratic discussions requires moving beyond traditional evaluation methods towards more nuanced observation techniques. Rather than focusing solely on correct answers, teachers should evaluate the quality of student reasoning, their ability to build upon others' ideas, and their willingness to revise thinking when presented with new evidence. David Boud's research on formative assessment emphasises that meaningful evaluation occurs through ongoing dialogue rather than summative judgements.

Practical assessment strategies include maintaining observational notes during discussions, tracking how students frame questions, and documenting moments when learners demonstrate metacognitive awareness. Teachers can create simple rubrics that measure critical thinking indicators such as evidence use, logical connections between ideas, and respectful challenge of peers' perspectives. Additionally, brief reflective writing exercises immediately following Socratic sessions allow students to articulate their thinking process and identify knowledge gaps.

To ensure equitable assessment, consider implementing participation portfolios where students collect examples of their contributions over time, including written reflections on their evolving understanding. This approach accommodates different communication styles whilst maintaining rigorous academic standards. Regular peer feedback sessions also provide valuable assessment data, as students often recognise quality reasoning in their classmates' contributions that teachers might miss during fast-paced discussions.

The versatility of Socratic questioning techniques becomes particularly evident when applied across different academic disciplines, each offering unique opportunities for deep inquiry-based learning. In mathematics and sciences, teachers can guide students through problem-solving processes by asking "What patterns do you notice?" or "How might we test this hypothesis?" rather than immediately providing formulae or answers. Literature and history lessons benefit from questions such as "What evidence supports this character's motivation?" or "How might different perspectives change our understanding of this historical event?" These subject-specific applications demonstrate how strategic questioning can transform passive knowledge absorption into active intellectual engagement.

Implementing Socratic methods across the curriculum requires careful consideration of cognitive load, as Allan Collins' research on cognitive apprenticeship suggests. Art and music teachers might begin with observational questions like "What emotions does this piece evoke, and what specific elements create that response?" before progressing to more complex analytical discussions. Science educators can scaffold inquiry by starting with concrete observations before moving to abstract theoretical concepts, ensuring students build understanding progressively rather than becoming overwhelmed by complexity.

Successful cross-curricular implementation involves adapting questioning pace and depth to match both subject matter and student readiness levels. Teachers should prepare layered question sequences that can accommodate different learning speeds whilst maintaining rigorous intellectual challenge across all disciplines.

The Socratic method offers a powerful approach to developing critical thinking and promoting deeper understanding in the classroom. By shifting from a traditional lecture-based format to a dialogue-driven approach, teachers can helps students to take ownership of their learning and develop essential skills for success in the 21st century.

Embracing the Socratic method requires a commitment to creating a student-centred learning environment, where intellectual curiosity is celebrated, and inquiry is valued above rote memorisation. By incorporating these techniques into your teaching practice, you can transform your classroom into a vibrant hub of intellectual exploration and discovery. Remember, the goal is not to impart knowledge, but to ignite a lifelong passion for learning.

To begin your journey with Socratic teaching, start small and build confidence gradually. Choose a familiar topic for your first Socratic discussion, perhaps one where students already have some background knowledge. Prepare open-ended questions that encourage exploration rather than seeking single correct answers. For example, instead of asking "What caused World War I?", try "What conditions might lead a society to choose war over peaceful solutions?" This shift in questioning techniques immediately improves the conversation from recall to analysis.

Establish clear ground rules for classroom discussions that emphasise respectful listening and thoughtful response. Encourage students to build upon each other's ideas using phrases like "I'd like to add to what Sarah said.." or "That makes me think about..". When students struggle to respond, resist the urge to provide immediate answers. Instead, rephrase questions or break complex ideas into smaller components. Remember that productive silence often indicates deep thinking rather than confusion.

Monitor your progress by observing changes in student engagement and the quality of their questions. Successful inquiry-based learning manifests when students begin questioning each other spontaneously and demonstrate curiosity beyond the prescribed curriculum. Document what works well in your specific context, as effective Socratic method implementation varies considerably between different classroom environments and student populations.

Critical thinking through dialogue

Socratic questioning encompasses six distinct types that challenge thinking systematically: clarification questions, probing assumptions, seeking reasons and evidence, exploring viewpoints and perspectives, examining implications and consequences, and questioning the question itself. Each type serves a specific purpose in deepening critical thinking and uncovering logical fallacies.

Clarification questions help students think more carefully about exactly what they are asking or thinking about. These foundational questions use basic 'tell me more' prompts that encourage deeper exploration. Examples include 'What do you mean by that?', 'Can you give me an example?', and 'Could you rephrase that in another way?'. When students struggle to articulate ideas clearly, clarification questions reveal gaps in understanding whilst helping them refine their thinking.

Questions that probe assumptions ask students to examine the underlying beliefs supporting their arguments. Every argument rests on assumptions, often unexamined ones. By asking 'What could we assume instead?', 'How can you verify or disprove that assumption?', or 'Why would someone make this assumption?', teachers help students recognise that their starting points might not be as solid as they initially believed. This recognition opens space for considering alternative perspectives.

Questions that probe reasons and evidence dig into the justifications students offer for their claims. People frequently use un-thought-through or weakly understood supports for their arguments. Examples include 'What evidence supports your answer?', 'What would be an example?', 'How do you know this is accurate?', and 'What are the strengths and weaknesses of that evidence?'. These questions develop students' capacity to distinguish between strong and weak reasoning.

Questions about viewpoints and perspectives encourage students to consider alternative positions. By asking 'How might someone else respond to that?', 'What would be an alternative?', or 'What is another way to look at this?', teachers help students move beyond their initial viewpoints. This type of questioning particularly supports development of empathy and cultural awareness, as students learn to consider how different backgrounds and experiences shape understanding.

Questions about implications and consequences push students to think beyond immediate conclusions. 'What are the implications of that?', 'If this is true, what else must be true?', 'What effect would that have?', and 'Who benefits from this?'. These questions develop students' capacity for systems thinking, helping them recognise that ideas and actions have ripple effects extending far beyond their immediate scope.

Questions about the question itself represent the most meta-cognitive level. By asking 'Why do you think I asked this question?', 'What does this question assume?', or 'Is there a better question we should be asking?', teachers help students develop awareness of how questions themselves shape thinking. This highest level of Socratic questioning develops students' capacity to monitor and regulate their own thought processes.

Fishbowl discussions (also called Socratic Circles) arrange students in two concentric circles where the inner circle actively discusses whilst the outer circle observes, takes notes, and provides feedback. Groups typically switch positions midway through, ensuring all students experience both active discussion and reflective observation roles.

Setting up a fishbowl requires arranging six to twelve chairs in an inner circle with sufficient space around them for remaining students to observe. This number allows for a range of perspectives whilst still giving each inner-circle participant opportunity to speak. The inner circle (the 'fish') actively discusses a text, question, or problem, whilst the outer circle observes patterns, contributions, and group dynamics.

Unlike traditional teacher-led discussions, fishbowl participants do not raise hands or call on names. Members of the inner circle speak directly to one another, building on each other's ideas, asking follow-up questions, and challenging assumptions. The teacher acts as facilitator rather than discussion leader, intervening only to redirect if needed or to mark transition points. This structure places students genuinely in control of the intellectual work.

The outer circle plays an equally important role through active observation. Students on the outside take notes on key ideas, track who speaks and what they contribute, identify patterns in the discussion, and notice gaps in the conversation. Some teachers assign specific observation tasks: tracking types of questions asked, noting evidence cited, monitoring how students build on others' ideas, or observing non-verbal communication. This structured observation develops meta-cognitive awareness about what effective discussion looks and sounds like.

After ten to fifteen minutes, teachers typically announce 'Switch', at which point listeners enter the fishbowl and speakers become the audience. Some teachers allow 'tapping in', where outer-circle students can gently tap inner-circle students' shoulders when they wish to join the discussion, creating more fluid movement between circles. Each rotation method offers different benefits: fixed switches ensure equal participation time, whilst tap-ins reward students who have something urgent to contribute.

Following the discussion, structured debriefing proves essential. The outer circle shares observations about patterns, strengths, and areas for growth. Inner-circle participants reflect on their experience and what made discussion challenging or productive. The teacher can then facilitate meta-discussion about discussion itself, helping students identify specific strategies that deepened their thinking. Over time, students internalise these strategies and apply them in other contexts.

Successful Socratic discussions require explicit preparation including teaching the method's purpose and structure, establishing ground rules for respectful dialogue, providing advance organisers for note-taking, and ensuring students have thoroughly engaged with source materials before discussion begins.

Begin by explaining what the Socratic method is, why you are using it, and how it differs from traditional classroom discussion. Many students have experienced only teacher-led question-answer exchanges where they compete to provide correct answers. Socratic discussion operates differently: there may be no single correct answer, disagreement is expected and valued, and thinking aloud is more important than polished responses. Making these differences explicit prevents confusion and anxiety.

Establish clear norms for respectful intellectual dialogue. Ground rules might include listening fully before responding, building on others' ideas, disagreeing with ideas rather than people, supporting claims with evidence from texts, asking genuine questions rather than making statements disguised as questions, and sharing airtime equitably. Co-constructing these norms with students increases buy-in. Display them prominently during discussions and reference them when intervening to redirect.

Provide scaffold materials that reduce cognitive load and allow students to focus on thinking. Allow students to have all their notes and texts on their desks during discussions. Provide graphic organisers such as Venn diagrams or fishbone diagrams to help students compare viewpoints and map reasoning visually. Some teachers provide sentence stems that support different discussion moves: 'I agree with [name] because..', 'I see it differently because..', 'That reminds me of..', 'What evidence supports that?'. These tools particularly support students still developing academic language or those with processing differences.

Ensure students have genuinely engaged with source materials before discussion. Surface-level preparation produces surface-level discussion. Assign pre-discussion tasks such as annotating texts, generating questions, identifying confusing passages, or writing initial position statements. Check that students have completed this preparation; beginning a Socratic discussion when students have not read wastes everyone's time and teaches them that preparation is optional.

Start with lower-stakes practice before attempting high-stakes discussions of complex or controversial topics. Use Think-Pair-Share activities where students discuss with partners before sharing with the whole class. Try brief Socratic exchanges focused on a single question or short passage. Build up to extended Socratic seminars as students develop discussion skills and confidence. This gradual release helps students experience success early, increasing their willingness to take intellectual risks later.

Common challenges in Socratic teaching include student reluctance to participate, discussions veering off-topic, dominant voices overshadowing quieter students, and managing controversial topics respectfully. Each challenge requires specific strategies that maintain the method's integrity whilst ensuring all students can engage productively.

When students are quiet or reluctant to participate, start small and build confidence gradually. Begin with pair discussions or small groups before whole-class seminars. Use wait time generously, allowing five to ten seconds of silence after asking questions. This extended pause signals that you value thoughtful responses over quick answers. Privately check in with reluctant students to understand barriers: some may need more preparation time, clearer expectations, or assurance that risk-taking is safe in your classroom.

Create a genuinely safe environment where all ideas are respected. This does not mean accepting inaccurate information unchallenged, but it does mean treating tentative thinking with curiosity rather than judgment. Model intellectual humility by acknowledging when you do not know something or when a student's point causes you to reconsider. When students see you treating uncertainty as normal rather than shameful, they become more willing to think aloud themselves.

When discussions go off-track, gently redirect without shutting down student initiative. Use a 'parking lot' to capture tangential ideas worth addressing later. Keep the main question visible throughout discussion and periodically refer back to it. Ask redirecting questions such as 'How does this connect to our original question?' or 'Let's pause and summarise where we've been before moving forward'. Occasional tangents can yield valuable insights; the art lies in distinguishing productive exploration from unproductive wandering.

Managing dominant voices requires proactive planning, not reactive intervention. Structure discussions to ensure equitable participation: use talking chips (each student gets a limited number of contributions), implement rotation systems where students speak in order around the circle, or designate discussion roles (questioner, evidence-seeker, connector, challenger). Track participation patterns and share data with students, helping them become aware of whose voices are heard frequently and whose rarely. Frame this as a collective responsibility rather than blaming individuals.

When teaching controversial topics, establish ground rules specifically for sensitive discussions. Distinguish between debate (trying to win) and dialogue (trying to understand). Require students to accurately represent opposing viewpoints before critiquing them. Use sentence stems that promote perspective-taking: 'From this viewpoint..', 'People who believe this might argue..', 'The evidence for this position includes..'. Consider using text-based discussions where students analyse others' arguments rather than immediately sharing personal positions, creating space for thinking before committing to stances.

Socratic teaching adapts successfully to online environments through asynchronous discussion forums with structured questioning prompts, synchronous video seminars using breakout rooms, and pre-recorded videos that model Socratic reasoning. Each format requires modifications to traditional in-person protocols whilst preserving the method's core elements.

Asynchronous discussion forums offer unique advantages for Socratic dialogue. Students have time to think deeply before responding, can craft more carefully reasoned arguments, and can engage with course materials whilst composing responses. Structure forums around central questions or dilemmas. Require initial posts within the first few days, then follow-up responses engaging with classmates' ideas. Explicitly prompt Socratic moves: 'Challenge an assumption in another student's post', 'Ask a clarifying question', 'Provide evidence supporting or contradicting a claim'.

Frame short videos around one central question or dilemma. Begin by asking 'What do you think?' and then walk through possible reasoning paths, highlighting common misconceptions before presenting robust interpretations. This format models Socratic thinking aloud, helping students understand the internal dialogue involved in critical thinking. Follow videos with reflection prompts or discussion questions that students explore asynchronously or in synchronous sessions.

Synchronous video discussions using platforms such as Zoom can replicate many aspects of in-person Socratic seminars. Arrange participants in a video gallery view to approximate circle seating. Use breakout rooms to create smaller fishbowl groups where students can speak more easily than in large full-class discussions. Assign some students to the main room (inner circle) and others to a waiting room or with cameras off (outer circle observers), then switch midway through. Use chat functions strategically: outer-circle students can type observations or questions whilst inner-circle discusses.

Manage participation in video discussions through visible tracking systems. Share a simple spreadsheet showing who has spoken and how many times. Use reaction buttons or hand-raising features, but periodically cold-call students who have not yet contributed, giving them brief notice: 'Ahmed, I'll come to you in a moment. What are your thoughts on this question?'. This approach balances volunteer enthusiasm with ensuring quieter voices are heard.

Online environments create particular challenges for building the trust necessary for vulnerable intellectual risk-taking. Invest extra time establishing classroom culture through icebreakers, small-group work, and low-stakes initial discussions. Use private messaging to check in with students who seem disengaged. Record discussions (with student permission) and review them together, analysing what made particular moments productive. This meta-reflection helps online learners develop discussion skills they cannot observe in person.

The Socratic Process transforms your classroom into a space for productive discussion. This active learning technique uses well-designed questions to help students examine their thinking and build understanding through dialogue. You ask, students respond, and together you explore ideas that sit beneath surface-level knowledge.

This approach works across wide ranges of subjects and age groups. Students make claims with examples, test their reasoning, and experience productive discomfort as they question what they thought they knew. The method thrives on collaborative inquiry rather than direct instruction.

Three key elements make the Socratic Process effective in your classroom:

The technique originated with the Greek philosopher Socrates, who claimed to know nothing but used questioning to expose gaps in others' knowledge. Teachers today apply this method to help students think independently and critically about complex ideas.

Law schools rely heavily on Socratic questioning to sharpen analytical skills, but the method works equally well in primary schools, secondary classrooms, and any setting where you want students to think rather than simply absorb. The process requires patience and practise, yet the payoff comes when students begin asking their own probing questions and taking intellectual risks.

In essence, the Socratic method is a pedagogical approach that encourages students to engage in critical thinking and to discover answers by themselves through a series of methodical and reflective questions. Socratic questioning serves as a powerful tool to dissect complex ideas, explore into assumptions, and break down conceptual frameworks.

In the classroom, this technique prompts students to question their own knowledge and convictions, consequently encouraging intellectual humility and the ability to scrutinize and refine their understanding. Moreover, the role of the teacher in this methodology shifts from being the conveyor of knowledge to a facilitator of dialogue, championing the art of inquiry over simply delivering content.

The process capitalizes on active learning, where students' insights unfold as they articulate responses to carefully crafted questions. Law schools, in particular, often employ this method to sharpen a law student's ability to analyse and argue effectively, evidencing the process's versatility across different fields of study.

The roots of the Socratic Process are firmly planted in the rich soil of ancient Greece, introduced by the philosopher Socrates as a way to challenge and expand the horizons of human understanding. Socrates himself claimed to know nothing, but through his skilled line of inquiry, he prompted those around him to reconsider their beliefs and the extent of their knowledge.

Teachers today bring this historical legacy into their classrooms by adopting Socrates's approach to draw out insights from students through a collaborative and open-ended dialogue. The method resists the notion of spoon-feeding facts; instead, it endeavors to bring forth an individual's innate wisdom and to channel it into a vigor for life-long learning.

This approach has stood the test of time for its effectiveness in promoting critical thinking and for enabling students to take ownership of their intellectual growth.

Russell's philosophy enhances modern teaching by emphasising rigorous questioning and logical analysis, which directly supports educators in implementing more effective Socratic dialogue techniques in contemporary classrooms. Russell's philosophy, centred on the importance of questioning assumptions and underlying beliefs, complements the fundamental objective of the Socratic method, which is to challenge presuppositions and encourage higher-order thinking.

Russell's contributions to the Socratic teaching method emanate from his persistent emphasis on critical thinking and inquiry-based learning. He championed the view that education should not merely be about the absorption of facts, but rather, a process of exploration led by probing questions that challenge existing assumptions and creates independent thought.

In practical classroom applications, Russell's philosophy translates into specific questioning techniques that encourage students to examine the foundations of their beliefs. Teachers can implement his approach by asking students to identify the evidence supporting their initial responses, then probing deeper with questions like "What assumptions are we making here?" or "How might someone with a different perspective view this issue?" This systematic doubt-casting mirrors Russell's analytical method whilst maintaining the supportive environment essential for productive classroom discussions.

Russell's emphasis on intellectual courage also provides a framework for managing the discomfort students often experience when their preconceptions are challenged through Socratic inquiry. Educators can explicitly acknowledge this discomfort as a natural part of learning, helping students understand that questioning familiar ideas strengthens rather than undermines genuine knowledge. By creating classroom cultures where uncertainty is viewed as an opportunity rather than a failure, teachers embody Russell's vision of education as intellectual liberation rather than indoctrination.

Effective Socratic teaching requires careful planning and execution. Here are some practical tips to help you implement this method in your classroom:

While the Socratic method can be incredibly effective, be aware of potential pitfalls:

Extensive research demonstrates that Socratic teaching techniques significantly enhance students' critical thinking abilities and academic outcomes. Studies by educational researchers including Paul and Elder have shown that students exposed to systematic questioning develop stronger analytical skills, with improvements in reasoning capabilities that transfer across subject areas. Additionally, research conducted by Chin and Osborne reveals that classrooms employing Socratic dialogue show increased student participation rates and deeper conceptual understanding compared to traditional lecture-based approaches.

The cognitive benefits extend beyond immediate learning gains. Bloom's taxonomy research indicates that Socratic questioning naturally guides students through higher-order thinking processes, moving from basic recall to analysis, synthesis, and evaluation. Furthermore, studies on classroom engagement consistently show that inquiry-based discussions increase student motivation and retention rates, as learners become active participants rather than passive recipients of information.

In practical terms, educators implementing Socratic methods report measurable improvements in student performance on assessments requiring critical analysis. Research by Fisher and Frey demonstrates that students who regularly engage in structured questioning activities show enhanced problem-solving skills and greater confidence in expressing complex ideas. These evidence-based outcomes provide compelling justification for incorporating Socratic techniques into daily classroom practice across all subject areas.

Assessing student learning during Socratic discussions requires moving beyond traditional evaluation methods towards more nuanced observation techniques. Rather than focusing solely on correct answers, teachers should evaluate the quality of student reasoning, their ability to build upon others' ideas, and their willingness to revise thinking when presented with new evidence. David Boud's research on formative assessment emphasises that meaningful evaluation occurs through ongoing dialogue rather than summative judgements.

Practical assessment strategies include maintaining observational notes during discussions, tracking how students frame questions, and documenting moments when learners demonstrate metacognitive awareness. Teachers can create simple rubrics that measure critical thinking indicators such as evidence use, logical connections between ideas, and respectful challenge of peers' perspectives. Additionally, brief reflective writing exercises immediately following Socratic sessions allow students to articulate their thinking process and identify knowledge gaps.

To ensure equitable assessment, consider implementing participation portfolios where students collect examples of their contributions over time, including written reflections on their evolving understanding. This approach accommodates different communication styles whilst maintaining rigorous academic standards. Regular peer feedback sessions also provide valuable assessment data, as students often recognise quality reasoning in their classmates' contributions that teachers might miss during fast-paced discussions.

The versatility of Socratic questioning techniques becomes particularly evident when applied across different academic disciplines, each offering unique opportunities for deep inquiry-based learning. In mathematics and sciences, teachers can guide students through problem-solving processes by asking "What patterns do you notice?" or "How might we test this hypothesis?" rather than immediately providing formulae or answers. Literature and history lessons benefit from questions such as "What evidence supports this character's motivation?" or "How might different perspectives change our understanding of this historical event?" These subject-specific applications demonstrate how strategic questioning can transform passive knowledge absorption into active intellectual engagement.

Implementing Socratic methods across the curriculum requires careful consideration of cognitive load, as Allan Collins' research on cognitive apprenticeship suggests. Art and music teachers might begin with observational questions like "What emotions does this piece evoke, and what specific elements create that response?" before progressing to more complex analytical discussions. Science educators can scaffold inquiry by starting with concrete observations before moving to abstract theoretical concepts, ensuring students build understanding progressively rather than becoming overwhelmed by complexity.

Successful cross-curricular implementation involves adapting questioning pace and depth to match both subject matter and student readiness levels. Teachers should prepare layered question sequences that can accommodate different learning speeds whilst maintaining rigorous intellectual challenge across all disciplines.

The Socratic method offers a powerful approach to developing critical thinking and promoting deeper understanding in the classroom. By shifting from a traditional lecture-based format to a dialogue-driven approach, teachers can helps students to take ownership of their learning and develop essential skills for success in the 21st century.

Embracing the Socratic method requires a commitment to creating a student-centred learning environment, where intellectual curiosity is celebrated, and inquiry is valued above rote memorisation. By incorporating these techniques into your teaching practice, you can transform your classroom into a vibrant hub of intellectual exploration and discovery. Remember, the goal is not to impart knowledge, but to ignite a lifelong passion for learning.

To begin your journey with Socratic teaching, start small and build confidence gradually. Choose a familiar topic for your first Socratic discussion, perhaps one where students already have some background knowledge. Prepare open-ended questions that encourage exploration rather than seeking single correct answers. For example, instead of asking "What caused World War I?", try "What conditions might lead a society to choose war over peaceful solutions?" This shift in questioning techniques immediately improves the conversation from recall to analysis.

Establish clear ground rules for classroom discussions that emphasise respectful listening and thoughtful response. Encourage students to build upon each other's ideas using phrases like "I'd like to add to what Sarah said.." or "That makes me think about..". When students struggle to respond, resist the urge to provide immediate answers. Instead, rephrase questions or break complex ideas into smaller components. Remember that productive silence often indicates deep thinking rather than confusion.

Monitor your progress by observing changes in student engagement and the quality of their questions. Successful inquiry-based learning manifests when students begin questioning each other spontaneously and demonstrate curiosity beyond the prescribed curriculum. Document what works well in your specific context, as effective Socratic method implementation varies considerably between different classroom environments and student populations.

Critical thinking through dialogue

Socratic questioning encompasses six distinct types that challenge thinking systematically: clarification questions, probing assumptions, seeking reasons and evidence, exploring viewpoints and perspectives, examining implications and consequences, and questioning the question itself. Each type serves a specific purpose in deepening critical thinking and uncovering logical fallacies.

Clarification questions help students think more carefully about exactly what they are asking or thinking about. These foundational questions use basic 'tell me more' prompts that encourage deeper exploration. Examples include 'What do you mean by that?', 'Can you give me an example?', and 'Could you rephrase that in another way?'. When students struggle to articulate ideas clearly, clarification questions reveal gaps in understanding whilst helping them refine their thinking.

Questions that probe assumptions ask students to examine the underlying beliefs supporting their arguments. Every argument rests on assumptions, often unexamined ones. By asking 'What could we assume instead?', 'How can you verify or disprove that assumption?', or 'Why would someone make this assumption?', teachers help students recognise that their starting points might not be as solid as they initially believed. This recognition opens space for considering alternative perspectives.

Questions that probe reasons and evidence dig into the justifications students offer for their claims. People frequently use un-thought-through or weakly understood supports for their arguments. Examples include 'What evidence supports your answer?', 'What would be an example?', 'How do you know this is accurate?', and 'What are the strengths and weaknesses of that evidence?'. These questions develop students' capacity to distinguish between strong and weak reasoning.

Questions about viewpoints and perspectives encourage students to consider alternative positions. By asking 'How might someone else respond to that?', 'What would be an alternative?', or 'What is another way to look at this?', teachers help students move beyond their initial viewpoints. This type of questioning particularly supports development of empathy and cultural awareness, as students learn to consider how different backgrounds and experiences shape understanding.

Questions about implications and consequences push students to think beyond immediate conclusions. 'What are the implications of that?', 'If this is true, what else must be true?', 'What effect would that have?', and 'Who benefits from this?'. These questions develop students' capacity for systems thinking, helping them recognise that ideas and actions have ripple effects extending far beyond their immediate scope.

Questions about the question itself represent the most meta-cognitive level. By asking 'Why do you think I asked this question?', 'What does this question assume?', or 'Is there a better question we should be asking?', teachers help students develop awareness of how questions themselves shape thinking. This highest level of Socratic questioning develops students' capacity to monitor and regulate their own thought processes.

Fishbowl discussions (also called Socratic Circles) arrange students in two concentric circles where the inner circle actively discusses whilst the outer circle observes, takes notes, and provides feedback. Groups typically switch positions midway through, ensuring all students experience both active discussion and reflective observation roles.

Setting up a fishbowl requires arranging six to twelve chairs in an inner circle with sufficient space around them for remaining students to observe. This number allows for a range of perspectives whilst still giving each inner-circle participant opportunity to speak. The inner circle (the 'fish') actively discusses a text, question, or problem, whilst the outer circle observes patterns, contributions, and group dynamics.

Unlike traditional teacher-led discussions, fishbowl participants do not raise hands or call on names. Members of the inner circle speak directly to one another, building on each other's ideas, asking follow-up questions, and challenging assumptions. The teacher acts as facilitator rather than discussion leader, intervening only to redirect if needed or to mark transition points. This structure places students genuinely in control of the intellectual work.

The outer circle plays an equally important role through active observation. Students on the outside take notes on key ideas, track who speaks and what they contribute, identify patterns in the discussion, and notice gaps in the conversation. Some teachers assign specific observation tasks: tracking types of questions asked, noting evidence cited, monitoring how students build on others' ideas, or observing non-verbal communication. This structured observation develops meta-cognitive awareness about what effective discussion looks and sounds like.

After ten to fifteen minutes, teachers typically announce 'Switch', at which point listeners enter the fishbowl and speakers become the audience. Some teachers allow 'tapping in', where outer-circle students can gently tap inner-circle students' shoulders when they wish to join the discussion, creating more fluid movement between circles. Each rotation method offers different benefits: fixed switches ensure equal participation time, whilst tap-ins reward students who have something urgent to contribute.

Following the discussion, structured debriefing proves essential. The outer circle shares observations about patterns, strengths, and areas for growth. Inner-circle participants reflect on their experience and what made discussion challenging or productive. The teacher can then facilitate meta-discussion about discussion itself, helping students identify specific strategies that deepened their thinking. Over time, students internalise these strategies and apply them in other contexts.

Successful Socratic discussions require explicit preparation including teaching the method's purpose and structure, establishing ground rules for respectful dialogue, providing advance organisers for note-taking, and ensuring students have thoroughly engaged with source materials before discussion begins.

Begin by explaining what the Socratic method is, why you are using it, and how it differs from traditional classroom discussion. Many students have experienced only teacher-led question-answer exchanges where they compete to provide correct answers. Socratic discussion operates differently: there may be no single correct answer, disagreement is expected and valued, and thinking aloud is more important than polished responses. Making these differences explicit prevents confusion and anxiety.

Establish clear norms for respectful intellectual dialogue. Ground rules might include listening fully before responding, building on others' ideas, disagreeing with ideas rather than people, supporting claims with evidence from texts, asking genuine questions rather than making statements disguised as questions, and sharing airtime equitably. Co-constructing these norms with students increases buy-in. Display them prominently during discussions and reference them when intervening to redirect.

Provide scaffold materials that reduce cognitive load and allow students to focus on thinking. Allow students to have all their notes and texts on their desks during discussions. Provide graphic organisers such as Venn diagrams or fishbone diagrams to help students compare viewpoints and map reasoning visually. Some teachers provide sentence stems that support different discussion moves: 'I agree with [name] because..', 'I see it differently because..', 'That reminds me of..', 'What evidence supports that?'. These tools particularly support students still developing academic language or those with processing differences.

Ensure students have genuinely engaged with source materials before discussion. Surface-level preparation produces surface-level discussion. Assign pre-discussion tasks such as annotating texts, generating questions, identifying confusing passages, or writing initial position statements. Check that students have completed this preparation; beginning a Socratic discussion when students have not read wastes everyone's time and teaches them that preparation is optional.

Start with lower-stakes practice before attempting high-stakes discussions of complex or controversial topics. Use Think-Pair-Share activities where students discuss with partners before sharing with the whole class. Try brief Socratic exchanges focused on a single question or short passage. Build up to extended Socratic seminars as students develop discussion skills and confidence. This gradual release helps students experience success early, increasing their willingness to take intellectual risks later.

Common challenges in Socratic teaching include student reluctance to participate, discussions veering off-topic, dominant voices overshadowing quieter students, and managing controversial topics respectfully. Each challenge requires specific strategies that maintain the method's integrity whilst ensuring all students can engage productively.

When students are quiet or reluctant to participate, start small and build confidence gradually. Begin with pair discussions or small groups before whole-class seminars. Use wait time generously, allowing five to ten seconds of silence after asking questions. This extended pause signals that you value thoughtful responses over quick answers. Privately check in with reluctant students to understand barriers: some may need more preparation time, clearer expectations, or assurance that risk-taking is safe in your classroom.

Create a genuinely safe environment where all ideas are respected. This does not mean accepting inaccurate information unchallenged, but it does mean treating tentative thinking with curiosity rather than judgment. Model intellectual humility by acknowledging when you do not know something or when a student's point causes you to reconsider. When students see you treating uncertainty as normal rather than shameful, they become more willing to think aloud themselves.

When discussions go off-track, gently redirect without shutting down student initiative. Use a 'parking lot' to capture tangential ideas worth addressing later. Keep the main question visible throughout discussion and periodically refer back to it. Ask redirecting questions such as 'How does this connect to our original question?' or 'Let's pause and summarise where we've been before moving forward'. Occasional tangents can yield valuable insights; the art lies in distinguishing productive exploration from unproductive wandering.

Managing dominant voices requires proactive planning, not reactive intervention. Structure discussions to ensure equitable participation: use talking chips (each student gets a limited number of contributions), implement rotation systems where students speak in order around the circle, or designate discussion roles (questioner, evidence-seeker, connector, challenger). Track participation patterns and share data with students, helping them become aware of whose voices are heard frequently and whose rarely. Frame this as a collective responsibility rather than blaming individuals.

When teaching controversial topics, establish ground rules specifically for sensitive discussions. Distinguish between debate (trying to win) and dialogue (trying to understand). Require students to accurately represent opposing viewpoints before critiquing them. Use sentence stems that promote perspective-taking: 'From this viewpoint..', 'People who believe this might argue..', 'The evidence for this position includes..'. Consider using text-based discussions where students analyse others' arguments rather than immediately sharing personal positions, creating space for thinking before committing to stances.

Socratic teaching adapts successfully to online environments through asynchronous discussion forums with structured questioning prompts, synchronous video seminars using breakout rooms, and pre-recorded videos that model Socratic reasoning. Each format requires modifications to traditional in-person protocols whilst preserving the method's core elements.

Asynchronous discussion forums offer unique advantages for Socratic dialogue. Students have time to think deeply before responding, can craft more carefully reasoned arguments, and can engage with course materials whilst composing responses. Structure forums around central questions or dilemmas. Require initial posts within the first few days, then follow-up responses engaging with classmates' ideas. Explicitly prompt Socratic moves: 'Challenge an assumption in another student's post', 'Ask a clarifying question', 'Provide evidence supporting or contradicting a claim'.

Frame short videos around one central question or dilemma. Begin by asking 'What do you think?' and then walk through possible reasoning paths, highlighting common misconceptions before presenting robust interpretations. This format models Socratic thinking aloud, helping students understand the internal dialogue involved in critical thinking. Follow videos with reflection prompts or discussion questions that students explore asynchronously or in synchronous sessions.

Synchronous video discussions using platforms such as Zoom can replicate many aspects of in-person Socratic seminars. Arrange participants in a video gallery view to approximate circle seating. Use breakout rooms to create smaller fishbowl groups where students can speak more easily than in large full-class discussions. Assign some students to the main room (inner circle) and others to a waiting room or with cameras off (outer circle observers), then switch midway through. Use chat functions strategically: outer-circle students can type observations or questions whilst inner-circle discusses.

Manage participation in video discussions through visible tracking systems. Share a simple spreadsheet showing who has spoken and how many times. Use reaction buttons or hand-raising features, but periodically cold-call students who have not yet contributed, giving them brief notice: 'Ahmed, I'll come to you in a moment. What are your thoughts on this question?'. This approach balances volunteer enthusiasm with ensuring quieter voices are heard.

Online environments create particular challenges for building the trust necessary for vulnerable intellectual risk-taking. Invest extra time establishing classroom culture through icebreakers, small-group work, and low-stakes initial discussions. Use private messaging to check in with students who seem disengaged. Record discussions (with student permission) and review them together, analysing what made particular moments productive. This meta-reflection helps online learners develop discussion skills they cannot observe in person.

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/socratic-teaching-techniques-for-effective-learning#article","headline":"Socratic Teaching Techniques for Effective Learning","description":"Discover effective Socratic teaching techniques to enhance critical thinking and student engagement through open-ended questions and dynamic dialogues.","datePublished":"2024-05-21T15:23:56.457Z","dateModified":"2026-01-26T10:09:32.212Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/socratic-teaching-techniques-for-effective-learning"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/6951121b3530614965ba6466_b59c1t.webp","wordCount":6034},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/socratic-teaching-techniques-for-effective-learning#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"Socratic Teaching Techniques for Effective Learning","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/socratic-teaching-techniques-for-effective-learning"}]},{"@type":"FAQPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/socratic-teaching-techniques-for-effective-learning#faq","mainEntity":[{"@type":"Question","name":"What exactly is the Socratic Process and how does it differ from traditional questioning techniques?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"The Socratic Process is an active learning technique that uses well-designed questions to help students examine their thinking and build understanding through dialogue, rather than simply testing recall of facts. Unlike traditional questioning that often seeks specific correct answers, Socratic ques"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"How can teachers implement the Three-Element Socratic Teaching Framework in their classrooms?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Teachers can implement the framework by establishing structured dialogue formats like Socratic seminars and Socratic Circles, where students take ownership of conversations within a clear format. They should develop strategic questioning patterns that guide without telling, probing assumptions and e"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What age groups and subjects can effectively use Socratic teaching techniques?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"The Socratic method works across wide ranges of subjects and age groups, from primary schools to secondary classrooms and beyond. Law schools rely heavily on Socratic questioning to sharpen analytical skills, whilst literature and humanities classes use it to engage with philosophical discourse and "}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What are the main benefits students gain from Socratic teaching approaches?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Students develop critical thinking skills that transfer beyond the classroom, learning to make claims with examples and test their reasoning through collaborative inquiry. The method fosters intellectual humility and the ability to scrutinise and refine their understanding, encouraging students to q"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What challenges might teachers face when implementing Socratic methods and how can they overcome them?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"The process requires significant patience and practise, as teachers must learn to guide discussions without directly providing answers, which can feel uncomfortable initially. Teachers may struggle with shifting from their traditional role as knowledge deliverer to becoming a dialogue facilitator, r"}}]}]}