Dysgraphia: A teachers guide

Discover effective strategies to understand and assist children with dysgraphia. Enhance support for those facing writing challenges.

Discover effective strategies to understand and assist children with dysgraphia. Enhance support for those facing writing challenges.

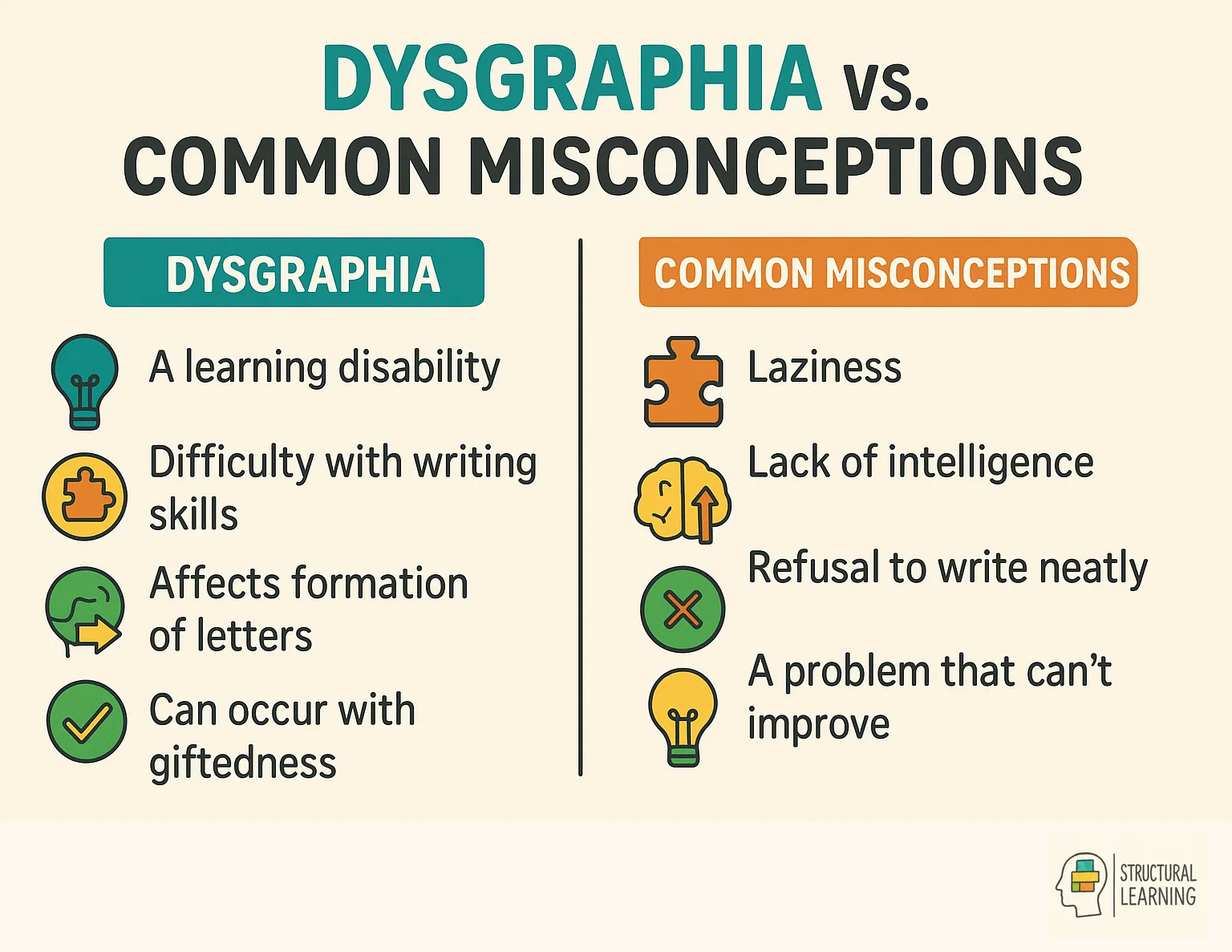

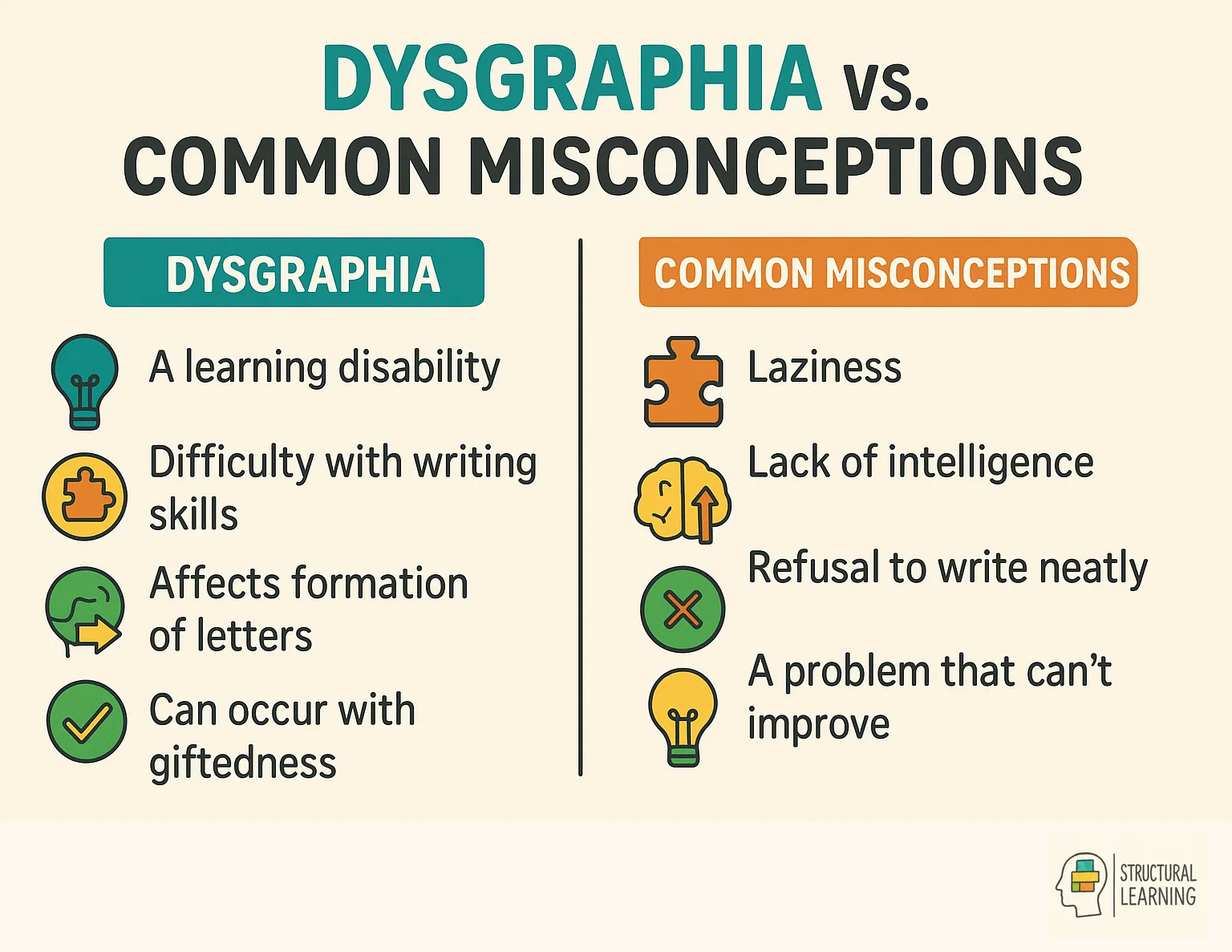

Dysgraphia is one of the more commonly overlooked specific learning difficulties, often occurring alongside conditions like dyslexia and dyscalculia. At its core, dysgraphia is a neurological difference that affects how children produce and work with written words. In school, this can show up in ways that are easily mistaken for carelessness or lack of effort, but the underlying issue is far more complex.

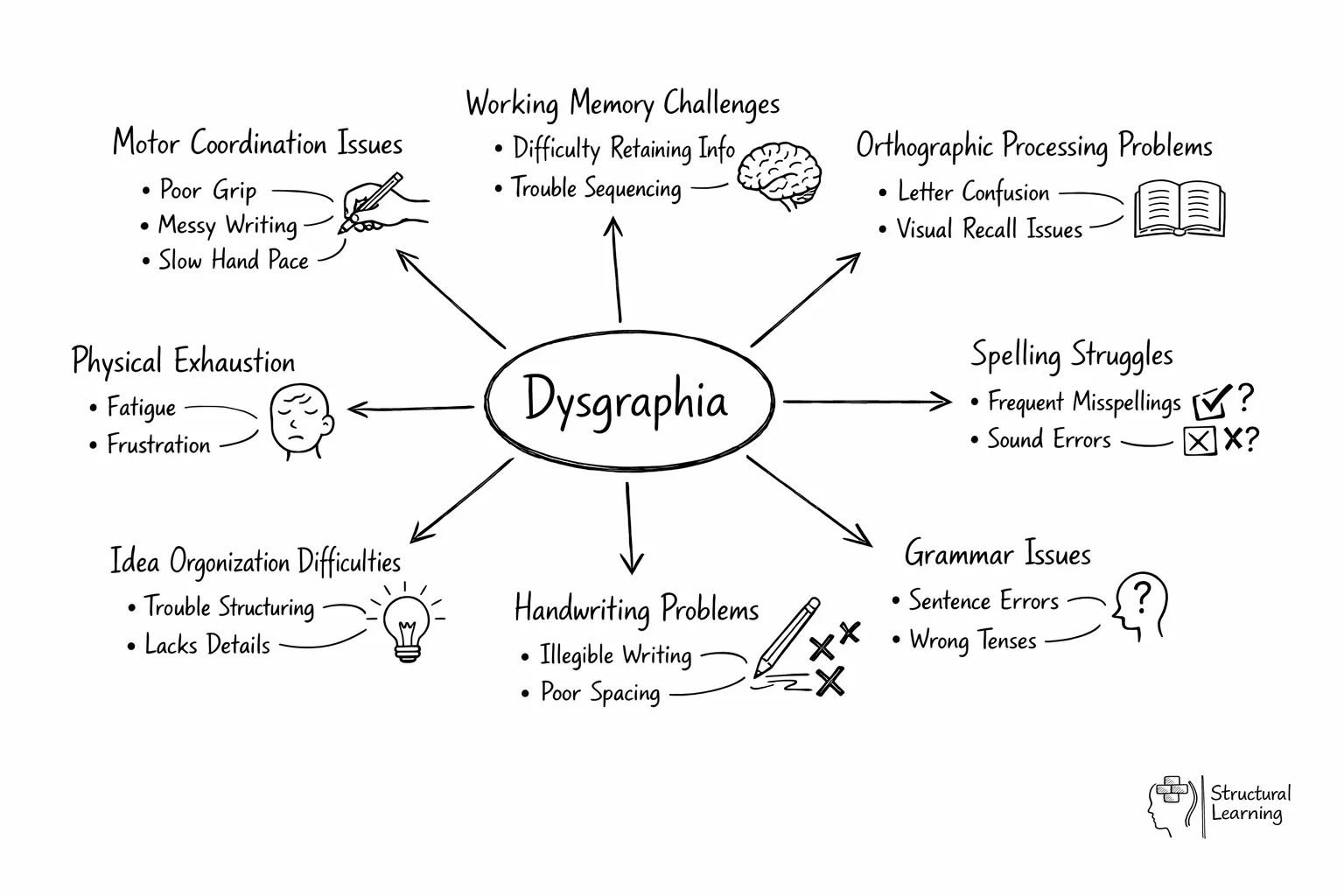

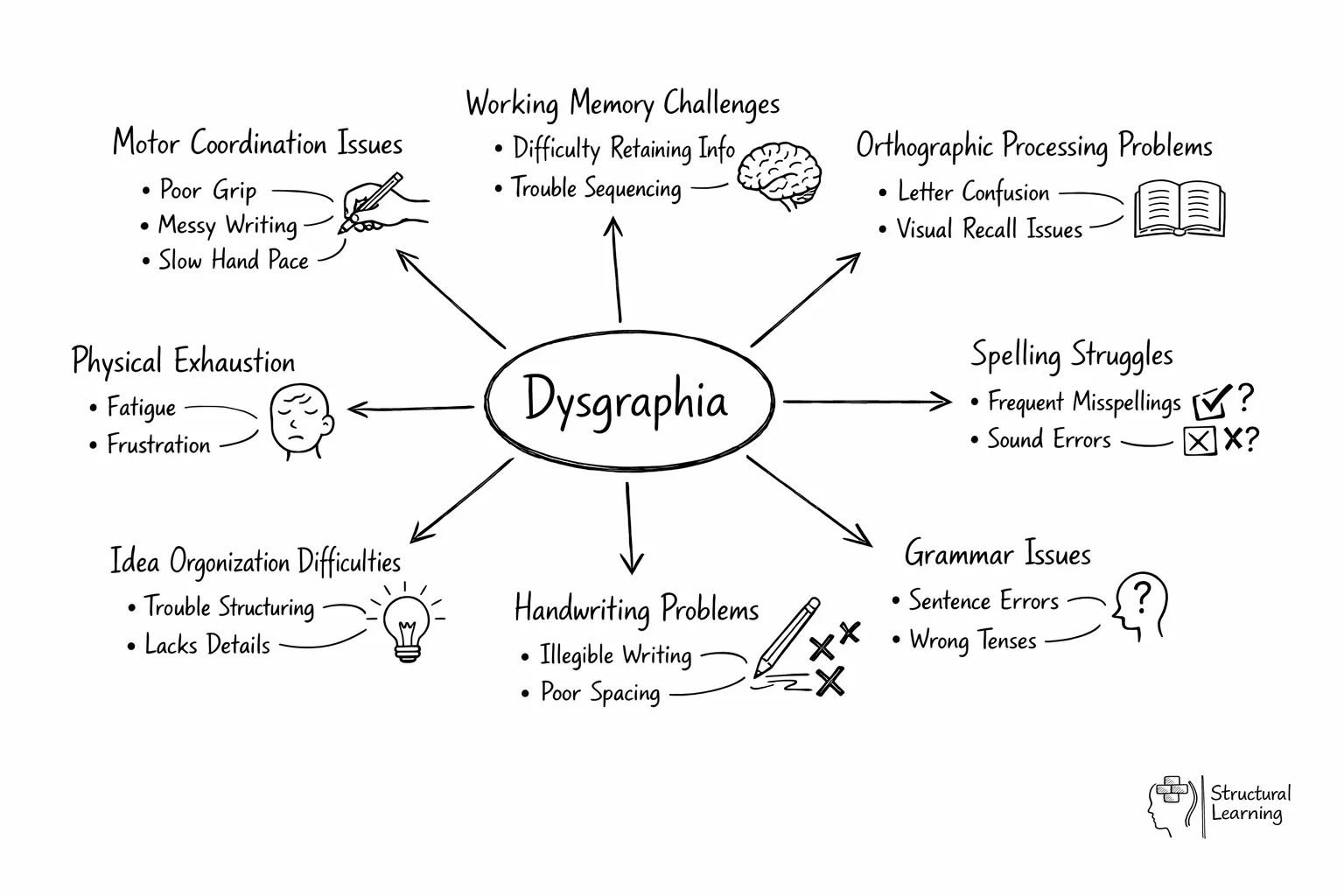

Children with dysgraphia may struggle with handwriting, spelling, grammar, and sentence construction. These difficulties are often caused by a combination of challenges with motor coordination, working memory, and orthographic processing, the ability to recognise and mentally store the visual patterns of words. For some pupils, the act of writing is physically exhausting. For others, it’s the organisation of ideas and language that breaks down.

It’s not just about messy writing. Pupils with dysgraphia may have difficulty recalling what letters look like (a breakdown in orthographic coding) or sequencing their thoughts into legible, logical sentences. Even when they use computers or speech-to-text tools, the cognitive demands of structuring their thinking into written form can still create a barrier to achievement.

As a teacher, it’s crucial to distinguish between students who can’t write and those who won’t. A child with dysgraphia often has rich, imaginative thoughts, but the moment they’re asked to write them down, the bottleneck appears. Supporting these learners isn’t about lowering expectations, it’s about giving them the scaffoldingto express what they know in ways that workfor them.

A child with dysgraphia might have a slower writing pace compared to their age milestone. That will have an impact on how they write down their ideas. They will also struggle with spelling, which will make it more difficult for them to form the letters in words. Because of their slower writing pace, they are having trouble putting their thoughts into words in this situation. Not because the child has problems organising their thoughts into writing.

Furthermore, some students may have writing difficulties not because they have dysgraphia, but because they have developmental coordination disorder (DCD), which affects both gross and fine motor skills.

The intelligence of the children is unaffected by dysgraphia. The main source of the difficulty is a motor skills issue. Support and accommodations at home and school can help to improve that.

Developmental dysgraphia differs from dyslexia in certain ways. Children with dyslexia may struggle with their reading skills, but because both dysgraphia and dyslexic symptoms might be similar to each other, such as spelling difficulties, it is possible to confuse one of these learning disorders with the other. A child could experience both problems. As a result, handle the child's case individually. One child may have dyslexia and ADHD, whilst another child may have dyslexia and dyscalculia. Therefore, address each child's difficulty with individual provision.

Children with dysgraphia have been shown to have problems with two cognitive abilities: auditory and visual processing.

Dysgraphia affects 5% to 20% of all children. Learning disabilities such as dysgraphia, dyslexia, and dyscalculia are more likely in children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or ADD.

Dysgraphia, as previously stated, is primarily concerned with learning difficulties with writing skills. It is difficult to detect or recognise learning disabilities at an early age. Even if there are symptoms, most testing is performed when the child is 6 or 7 years old. If a child of four years old is still struggling with writing or reading skills, this could be a warning sign. On the other hand, the child may just need more time to master this ability. As a result, most learning disabilities are formally diagnosed by the age of six.

However, it is critical to recognise these indicators and create an early intervention objective for the abilities that must be improved.

Many warning indicators that a child may have dysgraphia are as follows:

Not all of these symptoms will be seen in the child. It varies from child to child, and these symptoms can sometimes be linked to other learning issues. However, it is critical to monitor these indications and act accordingly until a formal assessment of the child can be performed.

There are various types of dysgraphia. To comprehend what the child is suffering from, it is necessary to have a general understanding of those sorts. Although a formal diagnosis is necessary, but having a general awareness of dysgraphia may benefit the child's progress.

Dysgraphia is classified into five types:

1. Dyslexic Dysgraphia:

This sort of dysgraphia has trouble with written work; they have difficulty writing in a clear manner. However, their copying skills would be at an average level and readable. Spelling skills may be impacted in this instance. They have difficulty writing alone. For example, children may find it difficult to write the word "cat" on their own. They will, however, be able to copy it clearly. Fine motor abilities are normally in this type.

note that just because a child has dyslexia dysgraphia does not mean he or she is dyslexic. Dyslexia is another type of learning disability, but this one is called "dyslexia dysgraphia." 'Butter', for example, is one word, and 'fly' is another. When I combine the two words, they form the word 'butterfly.' This is the case with dyslexia dysgraphia type.

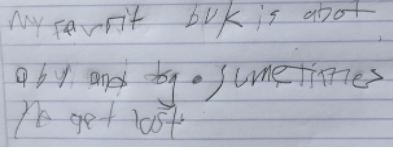

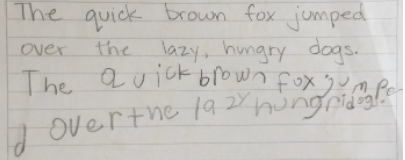

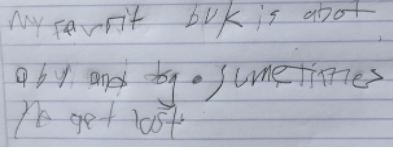

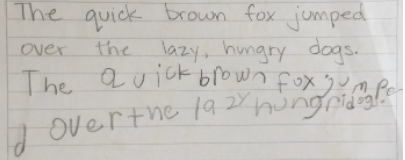

Here is an example of dyslexia dysgraphia:

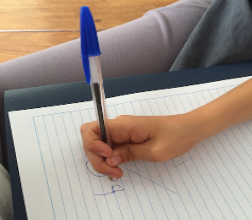

2. Motor Dysgraphia:

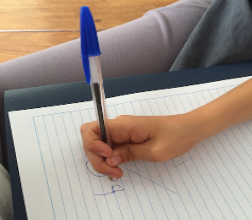

In this type the child may have poor pencil grip and fine motor skills. Although it may take more time and effort, the child may be able to write letters and numbers in the correct formation. Spelling abilities are unaffected by this type of dysgraphia and is usually at an average range.

3. Spatial Dysgraphia:

Usually, a visual-spatial impairment is connected to this kind of dysgraphia. A child can deal with direction, size, shapes, distance, and time with the help of their visual-spatial skills. For instance, determining the distance between objects. As a result, the child's written and coping skills may be unclear, but his or her spelling skills and finger-tapping speed will not be affected. The child may struggle with using spaces between lines, words, and letters. In addition to that having difficulty following the line.

4- Phonological Dysgraphia:

The difficulties with spelling and writing are related to this sort of dysgraphia. In this situation, the child might struggle to write words using phonetic knowledge and may have trouble writing words that are unknown to them. The child could also struggle to remember phonemes and combine words correctly. For instance, the word "h-a-t" could be pronounced as "h-t-a."

5- Lexical Dysgraphia:

If the sounds and letter patterns are presented and linked in an uncomplicated manner, the child has normal spelling ability. However, the child may struggle to spell irregular words like "was," "said," and so on.

There are various sorts of tests used to diagnose dysgraphia. This section will go over more of these tests.

1- Assess the Mechanics of Writing

Fourth Edition of Witten Language (TWOL-4). It primarily assesses the child's ability to write sentences logically, employing vocabulary, spelling, and punctuation. This test can be performed as early as the age of nine.

WJ IV and WIAT-III are two other comparable tests.

This test is crucial because if the student lacks to apply or retain the taught principles of punctuation, grammar, and spelling, writing will be difficult to them to write their thoughts and the reader will have a hard time understanding the student's ideas.

2- Assess the Thematics

Fourth Edition of Written Language (TOWL-4). At the age of nine, this exam can be administered. It primarily assesses the child's written composition abilities, sentence structure, vocabulary, and narrative composing abilities. Additionally, it evaluates the child's command of spelling, grammar, punctuation, and vocabulary.

The writing sample subtest of the Woodcock-Johnson IV Test of Achievement (WJ IV) and the essay composition section of the Wechsler Individual Achievement Test, Third Edition (WIAT, III) are tests that are comparable to it. At school age, any student can take any of these exams.

This test is significant because it assesses writing abilities and allows the child to express their opinions in writing. Understanding the sort of learning difficulty requires understanding the child's writing skills. As previously stated, there are five types of dysgraphia, and difficulties with writing might be caused by any of them.

3- Assess Fine Motors Skills

Grooved Pegboard is a test that can be used to evaluate fine motor skills. This test is suitable for children aged 5 to 18. This exam primarily assesses the strength of the hand's tiny muscles, in addition to eye-hand coordination skills. Similar tests include the Purdue Pegboard, which may be administered to children aged 5 to 18, and the NEPSY-II Visuomotor Precision subtests, which can be administered to children aged 3 to 16.

One of the most common reasons of dysgraphia is a deficit with fine motor skills. Better motor abilities enable the child to hold a pencil or an object. Slower muscle tones or physical problems can make writing process difficult. The assessor will collect the results of each test after completing them, together with the findings of any additional tests. A test that evaluates expressive language abilities, such as oral vocabulary, need to be done. It might take a few weeks to complete each of these assessments, after which the assessor would collect all of the data to write the final report.

The most effective strategies include providing alternative ways to demonstrate knowledge through oral presentations or visual projects, breaking writing tasks into smaller chunks with frequent breaks, and using graphic organisers to help structure thoughts before writing. Teachers should also allow extra time for written work, teach keyboarding skills early, and provide lined paper with raised lines or highlighted margins to improve spatial awareness. These accommodations reduce the cognitive load of writing while still allowing students to express their understanding.

Supporting students with dysgraphia in the classroom requires thoughtful adjustments that cater to their specific needs. Below are seven strategies to creates inclusivity and help these students thrive.

By applying these strategies, teachers can support nonfiction writers and pupils working with informational texts, helping them overcome challenges while building confidence and independence in the classroom.

Teachers can create dysgraphia-friendly environments by providing flexible seating options including slanted writing surfaces and pencil grips, displaying visual aids for letter formation and common spelling patterns, and establishing quiet spaces for focused writing tasks. The classroom should include easily accessible assistive technology like word processors with spell-check and speech-to-text software, along with alternative materials such as graph paper and wide-ruled notebooks. Most importantly, creates a culture where different writing speeds and styles are accepted and where effort is valued over perfection.

For learners with dysgraphia, schools can provide effective support by addressing the root causes of the disorder. Dysgraphia affects a person's ability to write due to difficulties with their spatial perception, writing movements and slow writing speed. Linguistic dysgraphia, a type of dysgraphia, can also impact executive functions and spatial planning, affecting a student's ability to express their thoughts in writing. As such, schools can support these learners by providing them with specialised assistance from special education teachers and professional school psychologists.

Schools can also provide interventions aimed at addressing the difficulty of handwriting in children with dysgraphia. For example, they can provide exercises focused on the development of motor skills, visual-spatial perception, and writing movements. The support must be personalized to each individual's needs and challenges by creating an individualized education plan (IEP). This includes identifying specific goals, objectives, and action plans for each child.

Finally, creating a positive learning environment where children with neurodevelopmental disorders feel comfortable and supported is crucial. Providing assistive technology, such as voice-to-text programs or dictation software, can also help to mitigate the effects of dysgraphia. In sum, schools can help support children with dysgraphia by working with them, their families, and their healthcare providers to provide specialised interventions that meet their unique needs, while also creating a supportive and inclusive learning environment.

Teachers should start with evidence-based resources from organisations like the International Dyslexia Association and Understood. org, which provide practical classroom strategies and case studies. Academic journals such as Learning Disabilities Research & Practice offer research-backed interventions, while books like 'The Source for Dyslexia and Dysgraphia' by Regina Richards provide comprehensive guides to identification and support. Professional development courses through organisations like Learning Disabilities Association offer certification programs specifically focused on supporting students with written expression difficulties.

These studies collectively highlight the significance of early diagnosis, targeted intervention, and the role of technology and occupational therapy in managing and improving handwriting skills in children with dysgraphia.

1. Handwriting development in grade 2 and grade 3 primary school children with normal, at risk, or dysgraphic characteristics(A. Overvelde & W. Hulstijn, 2011)

Summary: This longitudinal study found that dysgraphia significantly decreased from 37% to 6% from grade 2 to grade 3. Handwriting quality improved substantially in at-risk and dysgraphic children, indicating that consistent dysgraphia needs thorough evaluation for appropriate diagnosis.

Outline: The study emphasises the importance of early assessment of handwriting skills and the role of occupational therapists in addressing illegible handwriting and motor control issues among young children with learning disorders.

2. To develop an occupational therapy kit for handwriting skills in children with dysgraphia and study its efficacy: A single-arm interventional study (Monika Verma, R. Begum, & Richa Kapoor, 2019)

Summary: The study demonstrated significant improvements in handwriting skills among children with dysgraphia using an occupational therapy kit based on the Handwriting Without Tears methodology, particularly in younger children and boys.

Outline: The intervention focused on multisensory activities and fine-motor skills, showing the effectiveness of targeted handwriting instruction and assessment of handwriting by occupational therapists to address messy handwriting and developmental motor disorders.

3. Automated human-level diagnosis of dysgraphia using a consumer tablet (Thibault Asselborn et al., 2018)

Summary: Utilizing a digital tablet, the study developed an automated tool for diagnosing dysgraphia with high accuracy (96.6% sensitivity, 99.2% specificity), emphasising the tool's potential for scalable, low-cost, and objective assessment of handwriting.

Outline: The research highlights the use of technology in identifying motor control issues and handwriting difficulties, offering a modern approach for early diagnosis and intervention in educational and clinical settings.

4. Occupational Therapy for Children with Handwriting Difficulties: A Framework for Evaluation and Treatment (Sidney Chu, 1997)

Summary: This paper presents a framework for occupational therapists to evaluate and treat handwriting difficulties in children, focusing on the integration of motor, sensory, perceptual, and cognitive functions.

Outline: The article discusses the comprehensive assessment of handwriting and the development of remedial programs, stressing the critical role of occupational therapists in improving handwriting skills and addressing poor handwriting in children with learning disorders.

5. Identification and Rating of Developmental Dysgraphia by Handwriting Analysis (J. Mekyska et al., 2017)

Summary: The study proposed an automated method for diagnosing and rating developmental dysgraphia using handwriting analysis, achieving high accuracy through digital parameterization of handwriting features.

Outline: The paper underscores the importance of early identification of dysgraphia and the potential for digital toolsto provide detailed assessments of handwriting, aiding in the development of personalized intervention strategies for children with motor control and handwriting issues.

Reference:

https://www.additudemag.com/what-is-dysgraphia-understanding-common-symptoms/

https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/23294-dysgraphia

https://www.healthline.com/health/what-is-dysgraphia#symptoms

https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/dysgraphia#dysgraphia-symptoms

https://www.occupationaltherapy.com/articles/dysgraphia-101-introduction-and-strategies-5327

https://www.yourtherapysource.com/blog1/2018/02/12/dysgraphia-types-symptoms-and-how-to-help/

https://www.ehow.co.uk/facts_6402615_difference-between-agraphia-dysgraphia.html

Dysgraphia is a neurological learning difference that affects how children produce and work with written words, involving difficulties with motor coordination, working memory, and orthographic processing. Unlike simple messy handwriting, dysgraphia creates a bottleneck between brilliant ideas and written expression, where pupils may struggle with spelling, grammar, sentence construction, and organising thoughts on paper despite being highly articulate verbally.

Students with dysgraphia often have rich, imaginative thoughts but experience a clear bottleneck when asked to write them down, showing physical exhaustion from writing tasks rather than laziness. Look for pupils who demonstrate strong verbal skills and understanding but struggle specifically when converting ideas to written form, often avoiding writing tasks due to genuine difficulty rather than defiance.

The five types are dyslexic, motor, spatial, phonological, and lexical dysgraphia, each affecting different aspects of the writing process from letter formation to spelling and spatial organisation. Understanding which type affects your pupils is crucial because each requires completely different classroom strategies and support approaches to be effective.

While technology can help with the physical aspects of writing, pupils with dysgraphia still face cognitive challenges in structuring and organising their thoughts into written form even when using assistive tools. Students need additional guidance and scaffolding to learn how to express their ideas coherently, regardless of whether they're writing by hand or using technology.

Key signs include difficulty forming letters and words in proper order, mirrored letters and numbers, weak pencil grip leading to hand cramps, and avoiding writing tasks. Other indicators are trouble with spacing between words, messy writing that's difficult to read, speaking words aloud while writing, and having perfect grammar when speaking but poor sentence structure in writing.

Pupils with dysgraphia typically have slower writing pace compared to age milestones, making it difficult to complete written assessments and express their knowledge fully within time constraints. This can lead to underestimation of their actual understanding and abilities, as their intelligence is unaffected but their means of demonstrating knowledge through writing is compromised.

Teachers should focus on providing scaffolding to help pupils express what they know in ways that work for them, rather than lowering expectations. This includes offering alternative assessment formats, allowing extra time for written work, providing structured frameworks for organising thoughts, and combining technology use with explicit instruction in written expression and organisation skills.

These peer-reviewed studies provide deeper insights into dysgraphia: a teachers guide and its application in educational settings.

Impact of inquiry interventions on students in e-learning and classroom environments using affective computing framework 51 citations

Ashwin et al. (2020)

This paper examines how inquiry-based interventions affect students in both digital and traditional classroom settings using emotional computing methods. While not directly about dysgraphia, it provides teachers with insights into how different learning environments and technological interventions can support students with diverse learning needs, including those who may struggle with traditional writing methods.

Research on inclusive classroom interventions broadening student perceptions 14 citations (Author, Year) demonstrates how targeted educational strategies can effectively challenge and expand students' stereotypical views of scientists, promoting more diverse and representative understandings of who can pursue scientific careers.

Sheffield et al. (2021)

This study explores how inclusive classroom practices can broaden students' perceptions of scientists and increase diversity in STEM fields. Teachers working with dysgraphic students can apply these inclusive intervention strategies to create more supportive learning environments that accommodate different learning styles and reduce barriers to participation in all subjects.

Research examining keyboarding difficulties in higher education students14 citations (Author, Year) explores the frequency and characteristics of typing challenges among university students who also experience handwriting difficulties, providing insights into digital accessibility needs in academic settings.

Rosenberg‐Adler et al. (2020)

This research investigates typing difficulties experienced by college students who have handwriting problems, examining how frequently these issues occur and their specific characteristics. This is highly relevant for teachers as it provides evidence-based insights into whether keyboarding can effectively serve as an alternative to handwritten work for students with dysgraphia, and what challenges they might still face with digital writing tools.

The impact of ChatGPT feedback on the development of EFL students’ writing skills 27 citations

Polakova et al. (2024)

This study evaluates how AI-powered feedback from ChatGPT can help English language learners improve their writing skills through personalized responses and suggestions. Teachers of students with dysgraphia can benefit from understanding how AI writing assistance tools might support struggling writers by providing immediate, personalized feedback that can supplement traditional instruction methods.

Teng et al. (2024)

This research examines how students' working memory, language proficiency, and self-regulation strategies affect their writing performance in multimedia environments. Teachers can use these findings to better understand the cognitive factors that influence writing difficulties in students with dysgraphia and develop targeted strategies that account for working memory limitations and help students develop better self-monitoring skills.

Dysgraphia is one of the more commonly overlooked specific learning difficulties, often occurring alongside conditions like dyslexia and dyscalculia. At its core, dysgraphia is a neurological difference that affects how children produce and work with written words. In school, this can show up in ways that are easily mistaken for carelessness or lack of effort, but the underlying issue is far more complex.

Children with dysgraphia may struggle with handwriting, spelling, grammar, and sentence construction. These difficulties are often caused by a combination of challenges with motor coordination, working memory, and orthographic processing, the ability to recognise and mentally store the visual patterns of words. For some pupils, the act of writing is physically exhausting. For others, it’s the organisation of ideas and language that breaks down.

It’s not just about messy writing. Pupils with dysgraphia may have difficulty recalling what letters look like (a breakdown in orthographic coding) or sequencing their thoughts into legible, logical sentences. Even when they use computers or speech-to-text tools, the cognitive demands of structuring their thinking into written form can still create a barrier to achievement.

As a teacher, it’s crucial to distinguish between students who can’t write and those who won’t. A child with dysgraphia often has rich, imaginative thoughts, but the moment they’re asked to write them down, the bottleneck appears. Supporting these learners isn’t about lowering expectations, it’s about giving them the scaffoldingto express what they know in ways that workfor them.

A child with dysgraphia might have a slower writing pace compared to their age milestone. That will have an impact on how they write down their ideas. They will also struggle with spelling, which will make it more difficult for them to form the letters in words. Because of their slower writing pace, they are having trouble putting their thoughts into words in this situation. Not because the child has problems organising their thoughts into writing.

Furthermore, some students may have writing difficulties not because they have dysgraphia, but because they have developmental coordination disorder (DCD), which affects both gross and fine motor skills.

The intelligence of the children is unaffected by dysgraphia. The main source of the difficulty is a motor skills issue. Support and accommodations at home and school can help to improve that.

Developmental dysgraphia differs from dyslexia in certain ways. Children with dyslexia may struggle with their reading skills, but because both dysgraphia and dyslexic symptoms might be similar to each other, such as spelling difficulties, it is possible to confuse one of these learning disorders with the other. A child could experience both problems. As a result, handle the child's case individually. One child may have dyslexia and ADHD, whilst another child may have dyslexia and dyscalculia. Therefore, address each child's difficulty with individual provision.

Children with dysgraphia have been shown to have problems with two cognitive abilities: auditory and visual processing.

Dysgraphia affects 5% to 20% of all children. Learning disabilities such as dysgraphia, dyslexia, and dyscalculia are more likely in children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or ADD.

Dysgraphia, as previously stated, is primarily concerned with learning difficulties with writing skills. It is difficult to detect or recognise learning disabilities at an early age. Even if there are symptoms, most testing is performed when the child is 6 or 7 years old. If a child of four years old is still struggling with writing or reading skills, this could be a warning sign. On the other hand, the child may just need more time to master this ability. As a result, most learning disabilities are formally diagnosed by the age of six.

However, it is critical to recognise these indicators and create an early intervention objective for the abilities that must be improved.

Many warning indicators that a child may have dysgraphia are as follows:

Not all of these symptoms will be seen in the child. It varies from child to child, and these symptoms can sometimes be linked to other learning issues. However, it is critical to monitor these indications and act accordingly until a formal assessment of the child can be performed.

There are various types of dysgraphia. To comprehend what the child is suffering from, it is necessary to have a general understanding of those sorts. Although a formal diagnosis is necessary, but having a general awareness of dysgraphia may benefit the child's progress.

Dysgraphia is classified into five types:

1. Dyslexic Dysgraphia:

This sort of dysgraphia has trouble with written work; they have difficulty writing in a clear manner. However, their copying skills would be at an average level and readable. Spelling skills may be impacted in this instance. They have difficulty writing alone. For example, children may find it difficult to write the word "cat" on their own. They will, however, be able to copy it clearly. Fine motor abilities are normally in this type.

note that just because a child has dyslexia dysgraphia does not mean he or she is dyslexic. Dyslexia is another type of learning disability, but this one is called "dyslexia dysgraphia." 'Butter', for example, is one word, and 'fly' is another. When I combine the two words, they form the word 'butterfly.' This is the case with dyslexia dysgraphia type.

Here is an example of dyslexia dysgraphia:

2. Motor Dysgraphia:

In this type the child may have poor pencil grip and fine motor skills. Although it may take more time and effort, the child may be able to write letters and numbers in the correct formation. Spelling abilities are unaffected by this type of dysgraphia and is usually at an average range.

3. Spatial Dysgraphia:

Usually, a visual-spatial impairment is connected to this kind of dysgraphia. A child can deal with direction, size, shapes, distance, and time with the help of their visual-spatial skills. For instance, determining the distance between objects. As a result, the child's written and coping skills may be unclear, but his or her spelling skills and finger-tapping speed will not be affected. The child may struggle with using spaces between lines, words, and letters. In addition to that having difficulty following the line.

4- Phonological Dysgraphia:

The difficulties with spelling and writing are related to this sort of dysgraphia. In this situation, the child might struggle to write words using phonetic knowledge and may have trouble writing words that are unknown to them. The child could also struggle to remember phonemes and combine words correctly. For instance, the word "h-a-t" could be pronounced as "h-t-a."

5- Lexical Dysgraphia:

If the sounds and letter patterns are presented and linked in an uncomplicated manner, the child has normal spelling ability. However, the child may struggle to spell irregular words like "was," "said," and so on.

There are various sorts of tests used to diagnose dysgraphia. This section will go over more of these tests.

1- Assess the Mechanics of Writing

Fourth Edition of Witten Language (TWOL-4). It primarily assesses the child's ability to write sentences logically, employing vocabulary, spelling, and punctuation. This test can be performed as early as the age of nine.

WJ IV and WIAT-III are two other comparable tests.

This test is crucial because if the student lacks to apply or retain the taught principles of punctuation, grammar, and spelling, writing will be difficult to them to write their thoughts and the reader will have a hard time understanding the student's ideas.

2- Assess the Thematics

Fourth Edition of Written Language (TOWL-4). At the age of nine, this exam can be administered. It primarily assesses the child's written composition abilities, sentence structure, vocabulary, and narrative composing abilities. Additionally, it evaluates the child's command of spelling, grammar, punctuation, and vocabulary.

The writing sample subtest of the Woodcock-Johnson IV Test of Achievement (WJ IV) and the essay composition section of the Wechsler Individual Achievement Test, Third Edition (WIAT, III) are tests that are comparable to it. At school age, any student can take any of these exams.

This test is significant because it assesses writing abilities and allows the child to express their opinions in writing. Understanding the sort of learning difficulty requires understanding the child's writing skills. As previously stated, there are five types of dysgraphia, and difficulties with writing might be caused by any of them.

3- Assess Fine Motors Skills

Grooved Pegboard is a test that can be used to evaluate fine motor skills. This test is suitable for children aged 5 to 18. This exam primarily assesses the strength of the hand's tiny muscles, in addition to eye-hand coordination skills. Similar tests include the Purdue Pegboard, which may be administered to children aged 5 to 18, and the NEPSY-II Visuomotor Precision subtests, which can be administered to children aged 3 to 16.

One of the most common reasons of dysgraphia is a deficit with fine motor skills. Better motor abilities enable the child to hold a pencil or an object. Slower muscle tones or physical problems can make writing process difficult. The assessor will collect the results of each test after completing them, together with the findings of any additional tests. A test that evaluates expressive language abilities, such as oral vocabulary, need to be done. It might take a few weeks to complete each of these assessments, after which the assessor would collect all of the data to write the final report.

The most effective strategies include providing alternative ways to demonstrate knowledge through oral presentations or visual projects, breaking writing tasks into smaller chunks with frequent breaks, and using graphic organisers to help structure thoughts before writing. Teachers should also allow extra time for written work, teach keyboarding skills early, and provide lined paper with raised lines or highlighted margins to improve spatial awareness. These accommodations reduce the cognitive load of writing while still allowing students to express their understanding.

Supporting students with dysgraphia in the classroom requires thoughtful adjustments that cater to their specific needs. Below are seven strategies to creates inclusivity and help these students thrive.

By applying these strategies, teachers can support nonfiction writers and pupils working with informational texts, helping them overcome challenges while building confidence and independence in the classroom.

Teachers can create dysgraphia-friendly environments by providing flexible seating options including slanted writing surfaces and pencil grips, displaying visual aids for letter formation and common spelling patterns, and establishing quiet spaces for focused writing tasks. The classroom should include easily accessible assistive technology like word processors with spell-check and speech-to-text software, along with alternative materials such as graph paper and wide-ruled notebooks. Most importantly, creates a culture where different writing speeds and styles are accepted and where effort is valued over perfection.

For learners with dysgraphia, schools can provide effective support by addressing the root causes of the disorder. Dysgraphia affects a person's ability to write due to difficulties with their spatial perception, writing movements and slow writing speed. Linguistic dysgraphia, a type of dysgraphia, can also impact executive functions and spatial planning, affecting a student's ability to express their thoughts in writing. As such, schools can support these learners by providing them with specialised assistance from special education teachers and professional school psychologists.

Schools can also provide interventions aimed at addressing the difficulty of handwriting in children with dysgraphia. For example, they can provide exercises focused on the development of motor skills, visual-spatial perception, and writing movements. The support must be personalized to each individual's needs and challenges by creating an individualized education plan (IEP). This includes identifying specific goals, objectives, and action plans for each child.

Finally, creating a positive learning environment where children with neurodevelopmental disorders feel comfortable and supported is crucial. Providing assistive technology, such as voice-to-text programs or dictation software, can also help to mitigate the effects of dysgraphia. In sum, schools can help support children with dysgraphia by working with them, their families, and their healthcare providers to provide specialised interventions that meet their unique needs, while also creating a supportive and inclusive learning environment.

Teachers should start with evidence-based resources from organisations like the International Dyslexia Association and Understood. org, which provide practical classroom strategies and case studies. Academic journals such as Learning Disabilities Research & Practice offer research-backed interventions, while books like 'The Source for Dyslexia and Dysgraphia' by Regina Richards provide comprehensive guides to identification and support. Professional development courses through organisations like Learning Disabilities Association offer certification programs specifically focused on supporting students with written expression difficulties.

These studies collectively highlight the significance of early diagnosis, targeted intervention, and the role of technology and occupational therapy in managing and improving handwriting skills in children with dysgraphia.

1. Handwriting development in grade 2 and grade 3 primary school children with normal, at risk, or dysgraphic characteristics(A. Overvelde & W. Hulstijn, 2011)

Summary: This longitudinal study found that dysgraphia significantly decreased from 37% to 6% from grade 2 to grade 3. Handwriting quality improved substantially in at-risk and dysgraphic children, indicating that consistent dysgraphia needs thorough evaluation for appropriate diagnosis.

Outline: The study emphasises the importance of early assessment of handwriting skills and the role of occupational therapists in addressing illegible handwriting and motor control issues among young children with learning disorders.

2. To develop an occupational therapy kit for handwriting skills in children with dysgraphia and study its efficacy: A single-arm interventional study (Monika Verma, R. Begum, & Richa Kapoor, 2019)

Summary: The study demonstrated significant improvements in handwriting skills among children with dysgraphia using an occupational therapy kit based on the Handwriting Without Tears methodology, particularly in younger children and boys.

Outline: The intervention focused on multisensory activities and fine-motor skills, showing the effectiveness of targeted handwriting instruction and assessment of handwriting by occupational therapists to address messy handwriting and developmental motor disorders.

3. Automated human-level diagnosis of dysgraphia using a consumer tablet (Thibault Asselborn et al., 2018)

Summary: Utilizing a digital tablet, the study developed an automated tool for diagnosing dysgraphia with high accuracy (96.6% sensitivity, 99.2% specificity), emphasising the tool's potential for scalable, low-cost, and objective assessment of handwriting.

Outline: The research highlights the use of technology in identifying motor control issues and handwriting difficulties, offering a modern approach for early diagnosis and intervention in educational and clinical settings.

4. Occupational Therapy for Children with Handwriting Difficulties: A Framework for Evaluation and Treatment (Sidney Chu, 1997)

Summary: This paper presents a framework for occupational therapists to evaluate and treat handwriting difficulties in children, focusing on the integration of motor, sensory, perceptual, and cognitive functions.

Outline: The article discusses the comprehensive assessment of handwriting and the development of remedial programs, stressing the critical role of occupational therapists in improving handwriting skills and addressing poor handwriting in children with learning disorders.

5. Identification and Rating of Developmental Dysgraphia by Handwriting Analysis (J. Mekyska et al., 2017)

Summary: The study proposed an automated method for diagnosing and rating developmental dysgraphia using handwriting analysis, achieving high accuracy through digital parameterization of handwriting features.

Outline: The paper underscores the importance of early identification of dysgraphia and the potential for digital toolsto provide detailed assessments of handwriting, aiding in the development of personalized intervention strategies for children with motor control and handwriting issues.

Reference:

https://www.additudemag.com/what-is-dysgraphia-understanding-common-symptoms/

https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/23294-dysgraphia

https://www.healthline.com/health/what-is-dysgraphia#symptoms

https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/dysgraphia#dysgraphia-symptoms

https://www.occupationaltherapy.com/articles/dysgraphia-101-introduction-and-strategies-5327

https://www.yourtherapysource.com/blog1/2018/02/12/dysgraphia-types-symptoms-and-how-to-help/

https://www.ehow.co.uk/facts_6402615_difference-between-agraphia-dysgraphia.html

Dysgraphia is a neurological learning difference that affects how children produce and work with written words, involving difficulties with motor coordination, working memory, and orthographic processing. Unlike simple messy handwriting, dysgraphia creates a bottleneck between brilliant ideas and written expression, where pupils may struggle with spelling, grammar, sentence construction, and organising thoughts on paper despite being highly articulate verbally.

Students with dysgraphia often have rich, imaginative thoughts but experience a clear bottleneck when asked to write them down, showing physical exhaustion from writing tasks rather than laziness. Look for pupils who demonstrate strong verbal skills and understanding but struggle specifically when converting ideas to written form, often avoiding writing tasks due to genuine difficulty rather than defiance.

The five types are dyslexic, motor, spatial, phonological, and lexical dysgraphia, each affecting different aspects of the writing process from letter formation to spelling and spatial organisation. Understanding which type affects your pupils is crucial because each requires completely different classroom strategies and support approaches to be effective.

While technology can help with the physical aspects of writing, pupils with dysgraphia still face cognitive challenges in structuring and organising their thoughts into written form even when using assistive tools. Students need additional guidance and scaffolding to learn how to express their ideas coherently, regardless of whether they're writing by hand or using technology.

Key signs include difficulty forming letters and words in proper order, mirrored letters and numbers, weak pencil grip leading to hand cramps, and avoiding writing tasks. Other indicators are trouble with spacing between words, messy writing that's difficult to read, speaking words aloud while writing, and having perfect grammar when speaking but poor sentence structure in writing.

Pupils with dysgraphia typically have slower writing pace compared to age milestones, making it difficult to complete written assessments and express their knowledge fully within time constraints. This can lead to underestimation of their actual understanding and abilities, as their intelligence is unaffected but their means of demonstrating knowledge through writing is compromised.

Teachers should focus on providing scaffolding to help pupils express what they know in ways that work for them, rather than lowering expectations. This includes offering alternative assessment formats, allowing extra time for written work, providing structured frameworks for organising thoughts, and combining technology use with explicit instruction in written expression and organisation skills.

These peer-reviewed studies provide deeper insights into dysgraphia: a teachers guide and its application in educational settings.

Impact of inquiry interventions on students in e-learning and classroom environments using affective computing framework 51 citations

Ashwin et al. (2020)

This paper examines how inquiry-based interventions affect students in both digital and traditional classroom settings using emotional computing methods. While not directly about dysgraphia, it provides teachers with insights into how different learning environments and technological interventions can support students with diverse learning needs, including those who may struggle with traditional writing methods.

Research on inclusive classroom interventions broadening student perceptions 14 citations (Author, Year) demonstrates how targeted educational strategies can effectively challenge and expand students' stereotypical views of scientists, promoting more diverse and representative understandings of who can pursue scientific careers.

Sheffield et al. (2021)

This study explores how inclusive classroom practices can broaden students' perceptions of scientists and increase diversity in STEM fields. Teachers working with dysgraphic students can apply these inclusive intervention strategies to create more supportive learning environments that accommodate different learning styles and reduce barriers to participation in all subjects.

Research examining keyboarding difficulties in higher education students14 citations (Author, Year) explores the frequency and characteristics of typing challenges among university students who also experience handwriting difficulties, providing insights into digital accessibility needs in academic settings.

Rosenberg‐Adler et al. (2020)

This research investigates typing difficulties experienced by college students who have handwriting problems, examining how frequently these issues occur and their specific characteristics. This is highly relevant for teachers as it provides evidence-based insights into whether keyboarding can effectively serve as an alternative to handwritten work for students with dysgraphia, and what challenges they might still face with digital writing tools.

The impact of ChatGPT feedback on the development of EFL students’ writing skills 27 citations

Polakova et al. (2024)

This study evaluates how AI-powered feedback from ChatGPT can help English language learners improve their writing skills through personalized responses and suggestions. Teachers of students with dysgraphia can benefit from understanding how AI writing assistance tools might support struggling writers by providing immediate, personalized feedback that can supplement traditional instruction methods.

Teng et al. (2024)

This research examines how students' working memory, language proficiency, and self-regulation strategies affect their writing performance in multimedia environments. Teachers can use these findings to better understand the cognitive factors that influence writing difficulties in students with dysgraphia and develop targeted strategies that account for working memory limitations and help students develop better self-monitoring skills.

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/dysgraphia#article","headline":"Dysgraphia: A teachers guide","description":"Discover effective strategies to understand and assist children with dysgraphia. Enhance support for those facing writing challenges.","datePublished":"2022-10-13T18:20:28.419Z","dateModified":"2026-01-26T10:09:32.212Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/dysgraphia"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/695268a043ac9a07f315674f_6952689c729b40e95eab8191_dysgraphia-infographic.webp","wordCount":4031},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/dysgraphia#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"Dysgraphia: A teachers guide","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/dysgraphia"}]},{"@type":"FAQPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/dysgraphia#faq","mainEntity":[{"@type":"Question","name":"What is dysgraphia and how does it differ from just messy handwriting?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Dysgraphia is a neurological learning difference that affects how children produce and work with written words, involving difficulties with motor coordination, working memory, and orthographic processing. Unlike simple messy handwriting, dysgraphia creates a bottleneck between brilliant ideas and wr"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"How can teachers distinguish between a student who can't write versus one who won't write?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Students with dysgraphia often have rich, imaginative thoughts but experience a clear bottleneck when asked to write them down, showing physical exhaustion from writing tasks rather than laziness. Look for pupils who demonstrate strong verbal skills and understanding but struggle specifically when c"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What are the five different types of dysgraphia and why does this matter for classroom support?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"The five types are dyslexic, motor, spatial, phonological, and lexical dysgraphia, each affecting different aspects of the writing process from letter formation to spelling and spatial organisation. Understanding which type affects your pupils is crucial because each requires completely different cl"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"Why isn't providing technology like laptops or speech-to-text software enough to support pupils with dysgraphia?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"While technology can help with the physical aspects of writing, pupils with dysgraphia still face cognitive challenges in structuring and organising their thoughts into written form even when using assistive tools. Students need additional guidance and scaffolding to learn how to express their ideas"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What early warning signs should teachers look for to identify potential dysgraphia in their pupils?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Key signs include difficulty forming letters and words in proper order, mirrored letters and numbers, weak pencil grip leading to hand cramps, and avoiding writing tasks. Other indicators are trouble with spacing between words, messy writing that's difficult to read, speaking words aloud while writi"}}]}]}