Teaching Nonfiction Writing

Discover effective strategies to develop non-fiction writing skills in the classroom, empowering students to become confident and independent writers.

Nonfiction writing helps students share their ideas and understanding. critical thinking and information skills matter more than ever. Students need to write clearly about facts and real topics to succeed in school and beyond.

To write good nonfiction, students need the right tools and techniques. Developing strong nonfiction writing skills requires practice and guidance. Using text features, picking interesting topics, and adding visual aids all help students organise their thoughts. Confidence grows when students get the right scaffolding at each step.

This article covers key strategies for teaching nonfiction writing. We look at approaches for both younger and older students, plus ways to blend traditional writing with digital tools.

Nonfiction writing plays a key role in education. One good way to teach it is through read-alouds. Teachers can show students how nonfiction texts are built. These sessions spark discussions and help students understand nonfiction structure.

Today's classrooms have access to many nonfiction books. A classroom library filled with nonfiction gives students a chance to explore different styles. As students read more nonfiction, they learn to navigate these texts with confidence.

Choosing books that match students' interests boosts engagement. When reading feels relevant, students enjoy it more. Research shows that students who read a wide range of nonfiction build stronger vocabulary and knowledge.

The practical applications of nonfiction writing extend far beyond the classroom walls. In today's digital age, students regularly encounter and create informational texts through social media posts, blog entries, and online discussions. Teaching strategies that emphasise nonfiction writing help students navigate this landscape critically, enabling them to distinguish between reliable sources and misinformation whilst developing their own credible voice.

Effective classroom practice demonstrates that nonfiction writing instruction strengthens students' analytical thinking skills. When pupils engage with explanatory texts, persuasive essays, and investigative reports, they learn to evaluate evidence, construct logical arguments, and synthesise information from multiple sources. These cognitive processes support student development across the curriculum, particularly in subjects requiring critical analysis and problem-solving.

Moreover, nonfiction writing serves as a powerful tool for inclusive education. Unlike creative writing, which may favour students with particular imaginative strengths, informational writing offers multiple pathways for success. Students can excel through research skills, logical reasoning, or clear exposition, making writing instruction more accessible to diverse learners and building confidence across different learning styles.

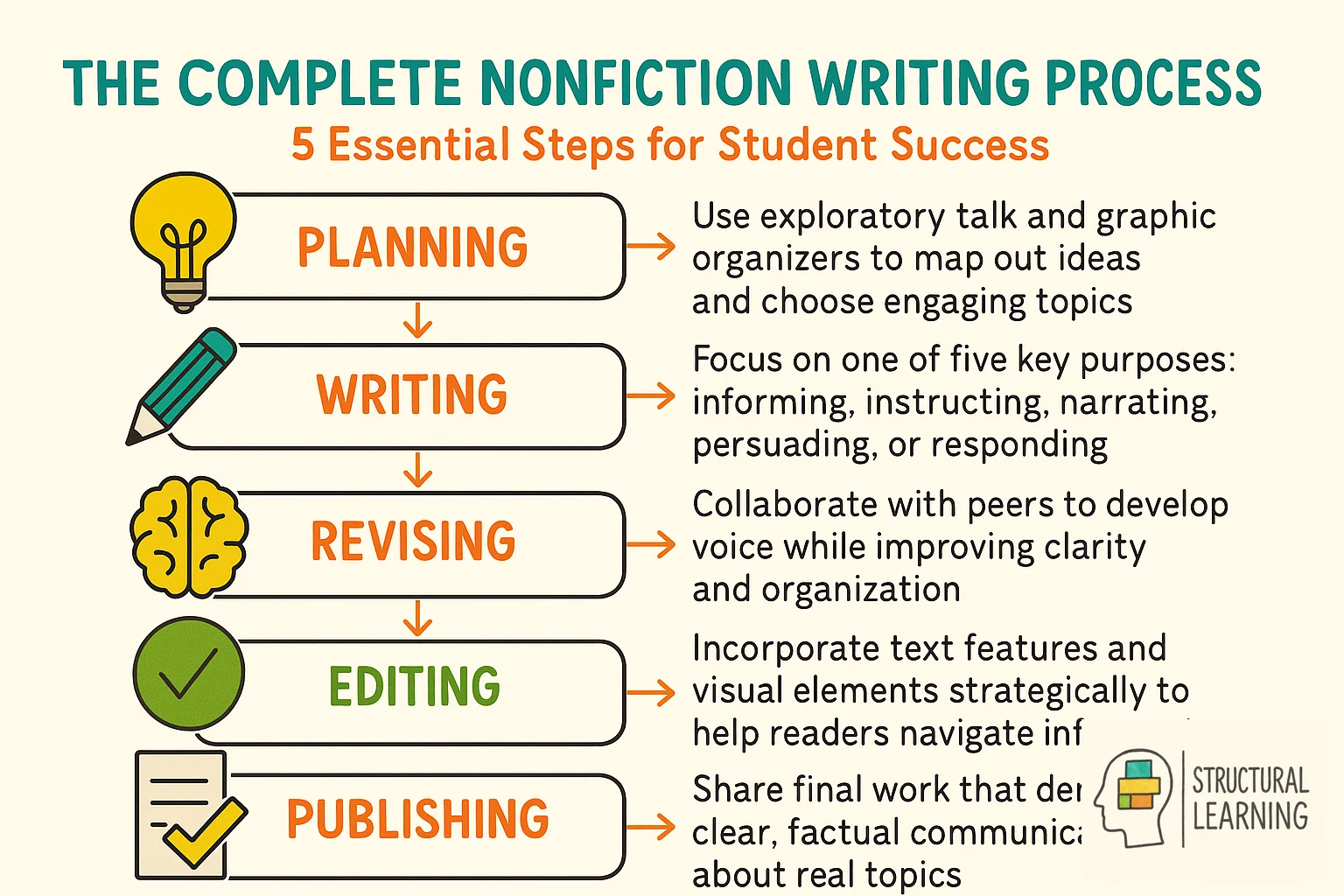

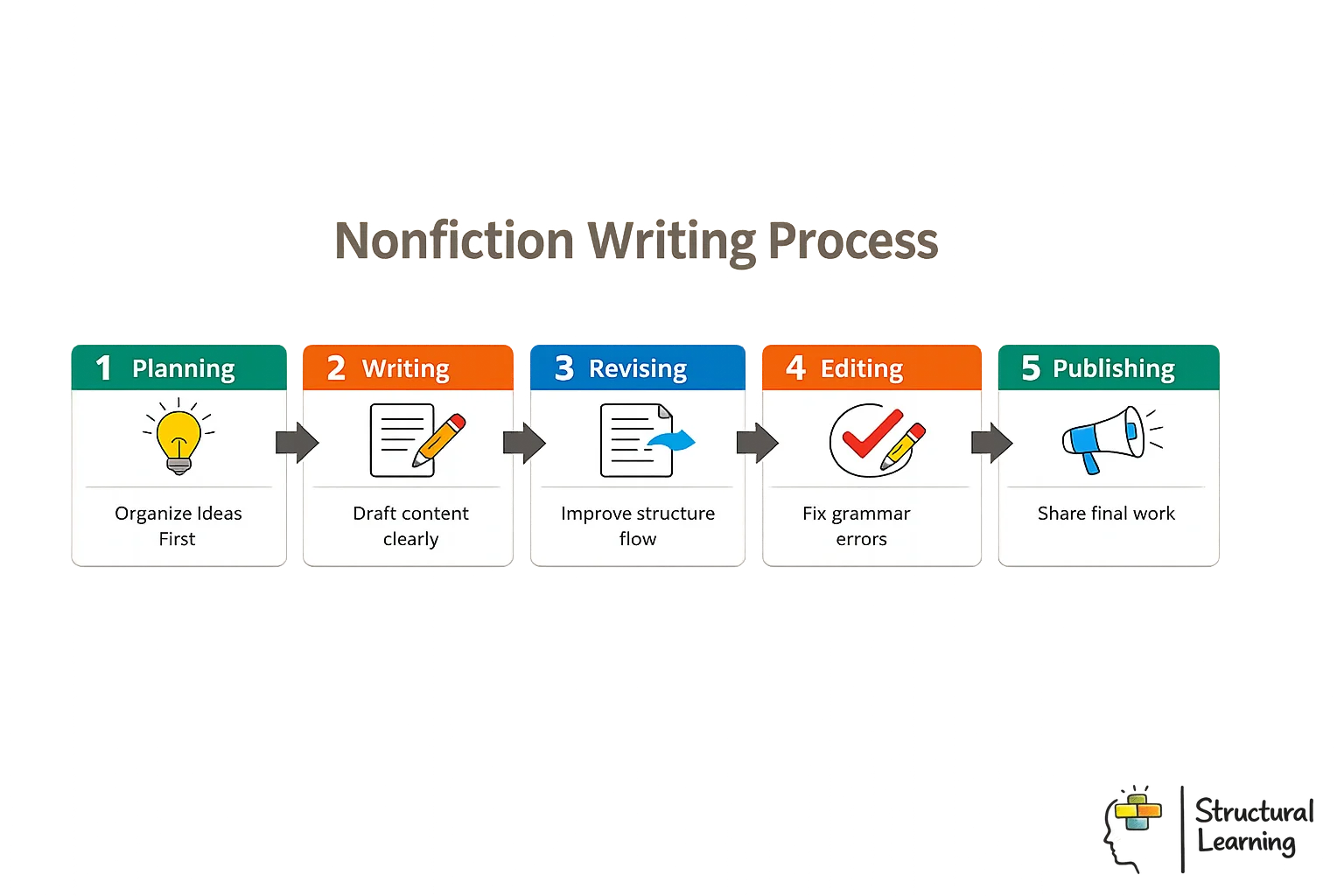

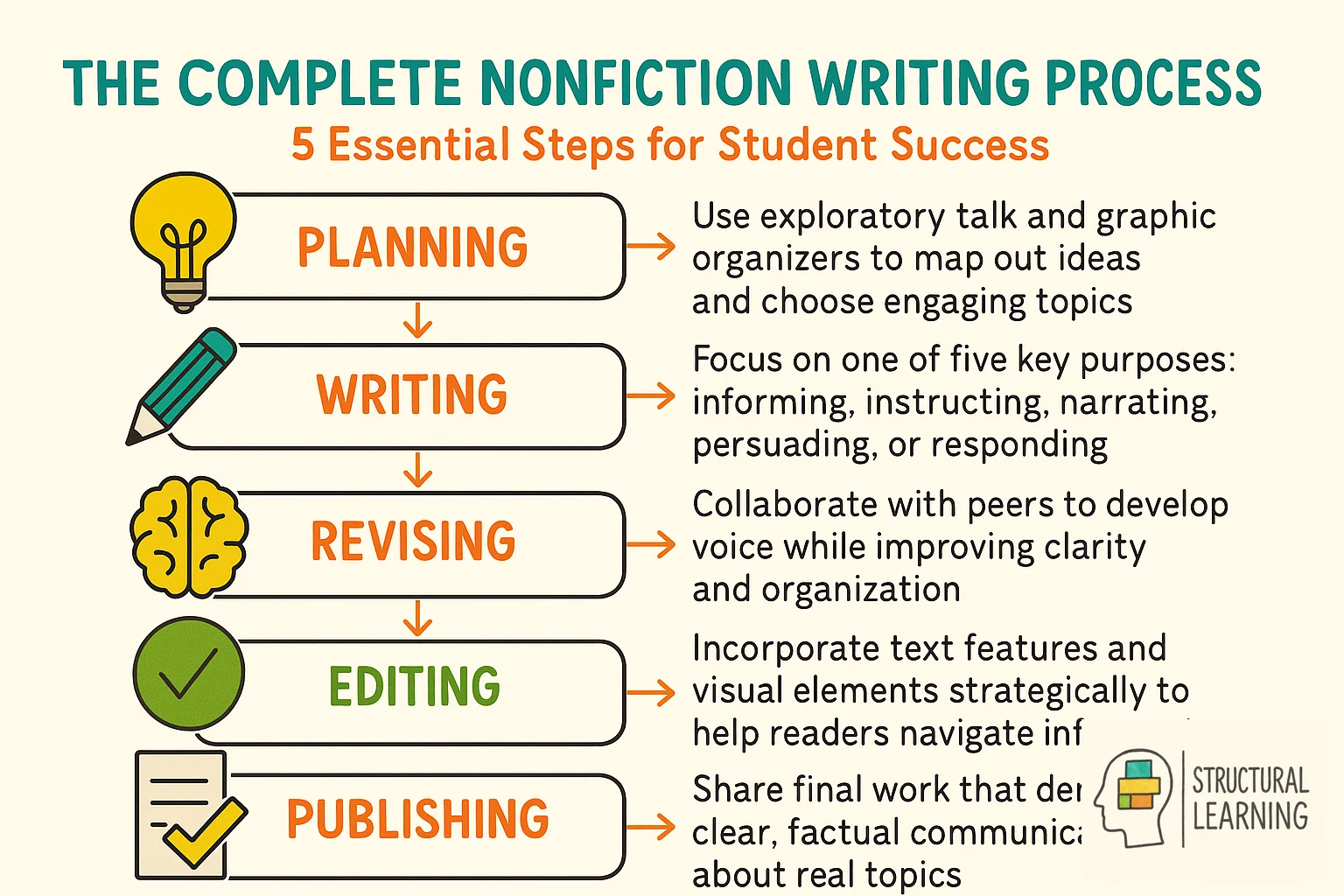

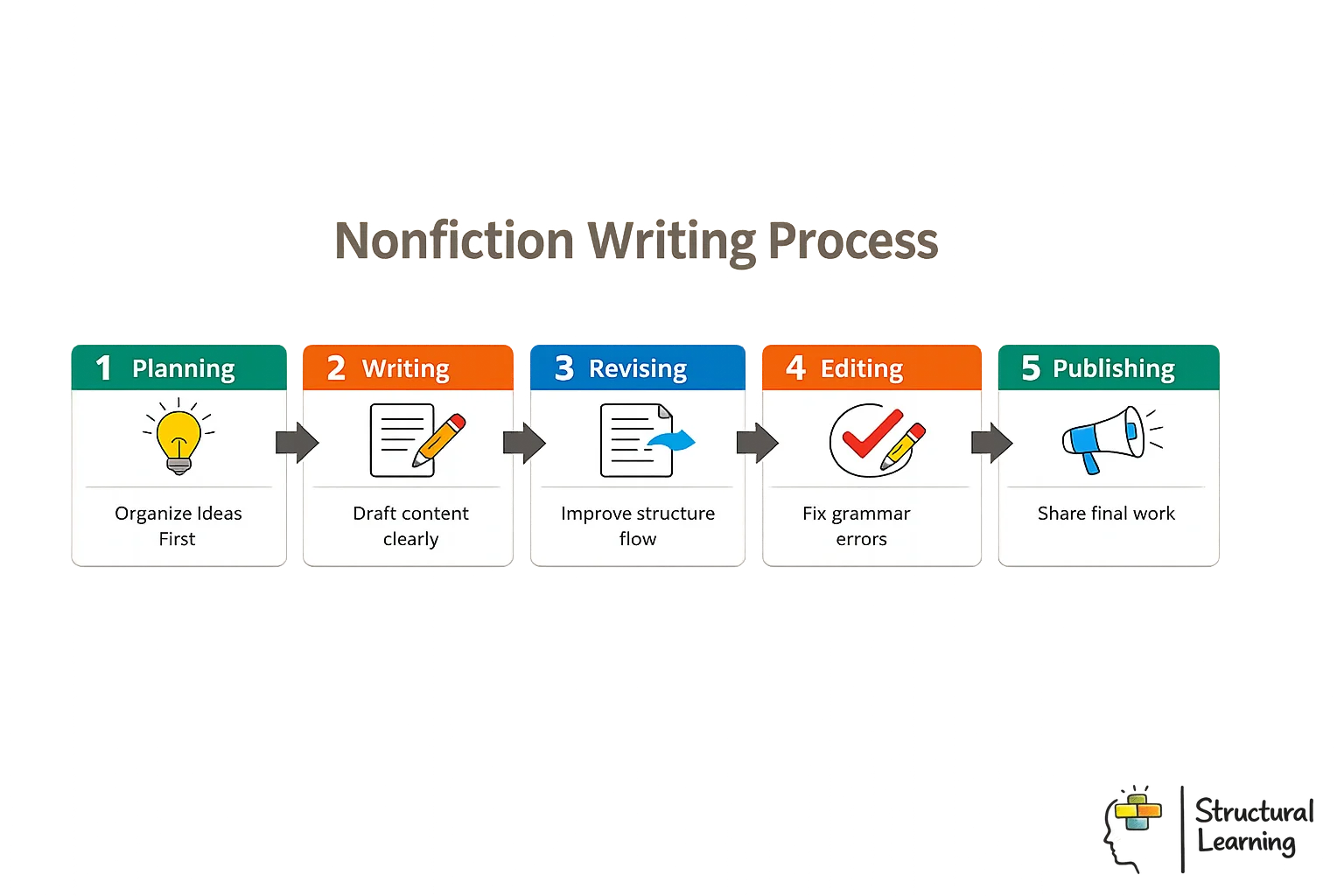

Teaching nonfiction writing involves several skills: planning, writing, revising, editing, and publishing. Each step matters. Teachers should cover the whole process, not just one part.

Teachers can help by giving students chances to explore real-world texts together. This builds both research and writing skills. Lessons work best when organised around five main purposes: informing, instructing, narrating, persuading, and responding.

Finding topics that interest students is key to keeping them motivated. Teaching summary writing helps students learn to be clear and focused when working with nonfiction texts.

Text features serve three main purposes: they help readers find information, deepen understanding, and expand knowledge on the topic. Visual features like photos, illustrations, and graphics spark prior knowledge and encourage questions.

Graphic organisers help students identify and use good reading strategies. Think of them as maps through complex information. Games and activities that teach text features make learning fun and memorable.

When nonfiction topics connect to students' lives and interests, motivation rises. Regular exposure to nonfiction helps students get better at navigating different formats and structures.

Working together on nonfiction texts helps students develop their voice while improving clarity and organisation. Rich discussions build vocabulary and content knowledge, setting a strong foundation for reading comprehension.

The Structural Learning Toolkit helps students become confident nonfiction writers. Here are key approaches from the toolkit:

Exploratory talk: Questioning and discussing ideas before writing helps students develop their thoughts. Talk tools encourage students to share ideas about different types of nonfiction. These discussions prepare students to write more effectively.

Visual planning: Graphic organisers help students map out their ideas so information flows logically. This is especially useful for nonfiction writing where complex content needs clear organisation. Oracy skills developed through discussion also support students with special educational needs in expressing their understanding.

Effective implementation begins with introducing students to text structure templates that correspond to different types of nonfiction writing. For persuasive essays, teachers might provide frameworks highlighting claim, evidence, and counterargument sections, whilst explanatory texts benefit from chronological or sequential organisers. These visual scaffolds help students understand how information flows logically within different genres, making the writing process more manageable and purposeful.

Regular practice with structural frameworks also develops students' critical reading skills alongside their writing abilities. When students recognise organisational patterns in published texts, they can apply these same structures to their own compositions with greater confidence. Teachers can enhance this connection by using mentor texts that exemplify clear structural patterns, encouraging students to analyse how professional writers organise their ideas before attempting similar approaches in their own work.

The benefits extend beyond immediate writing improvement, as students develop transferable skills for academic success across subjects. History essays, science reports, and geography investigations all require similar organisational thinking, making structural learning a valuable cross-curricular tool that supports student development throughout their educational journey.

Effective assessment of nonfiction writing requires a multifaceted approach that evaluates both content accuracy and writing craft. Research by Graham and Perin demonstrates that students benefit most from feedback that addresses specific elements such as organisation, evidence use, and clarity of argument. Teachers should develop rubrics that explicitly outline expectations for genre-specific features, whether assessing persuasive essays, explanatory texts, or research reports. This targeted approach helps students understand the distinct requirements of different nonfiction forms.

Formative feedback proves more valuable than summative assessment alone in developing student writing competency. Two-stars-and-a-wish feedback structures work particularly well for nonfiction pieces, allowing teachers to highlight successful elements whilst providing focused improvement targets. Peer assessment activities, when scaffolded with clear criteria, enable students to recognise effective techniques in others' work and transfer these insights to their own writing. Audio feedback can be especially powerful for nonfiction assessment, as teachers can explain complex reasoning about evidence selection or structural choices more efficiently than through written comments.

Successful nonfiction writing instruction integrates assessment throughout the writing process rather than only at completion. Conference-style discussions during drafting stages allow teachers to guide students' research choices, help them evaluate source credibility, and support their developing arguments. This ongoing dialogue transforms assessment from judgement into genuine learning support, developing student confidence in tackling challenging nonfiction writing tasks.

Effective nonfiction writing instruction requires flexible approaches that accommodate the diverse learning profiles found . John Sweller's cognitive load theory demonstrates that students process information differently, suggesting that teachers must vary their instructional methods to prevent overwhelming learners whilst maintaining appropriate challenge levels. For students with additional learning needs, this might involve breaking complex writing tasks into smaller, sequential steps, whilst advanced learners benefit from extended research opportunities and sophisticated organisational structures.

English as an Additional Language (EAL) students require particular consideration in nonfiction writing instruction. Research by Pauline Gibbons shows that providing language frames and sentence starters helps these learners access content whilst developing academic writing conventions. Visual supports, such as graphic organisers and topic-specific vocabulary walls, enable EAL students to focus on content development rather than struggling with linguistic structures alone.

Practical differentiation strategies include offering choice in writing formats (reports, explanations, or persuasive texts), adjusting research requirements based on reading levels, and implementing peer collaboration structures. Teachers can also differentiate assessment by focusing on individual progress rather than comparing all students against identical criteria, ensuring that every learner experiences success whilst working towards increasingly sophisticated nonfiction writing skills.

Nonfiction writing presents unique challenges that differ significantly from creative writing tasks. Students often struggle with selecting and organising relevant information, particularly when transitioning from narrative structures they know well to expository formats. Research by cognitive scientist John Swales demonstrates that students frequently attempt to apply story-telling techniques to informational texts, resulting in chronological organisation rather than logical argument structures. Additionally, many learners find difficulty in adopting an appropriate academic tone whilst maintaining reader engagement.

Effective solutions begin with explicit instruction in text structures before students attempt independent writing. Introduce graphic organisers that match specific nonfiction formats, such as cause-and-effect charts or compare-and-contrast matrices. Provide sentence stems and transitional phrases to support students in connecting ideas logically. For tone development, share exemplar texts and guide students through identifying formal versus informal language choices, helping them recognise how word selection impacts credibility and clarity.

Implement scaffolded practice opportunities that gradually release responsibility to students. Begin with collaborative research and outline creation, then progress to independent writing with teacher conferencing. Regular peer review sessions, focused on specific criteria such as evidence quality or paragraph organisation, help students internalise nonfiction conventions whilst developing critical evaluation skills essential for their own revision process.

Effective nonfiction writing instruction requires teachers to recognise that different genres demand distinct structural frameworks and cognitive approaches. Research by Kellogg and Raulerson demonstrates that students benefit significantly when teachers explicitly model genre-specific organisational patterns, such as the chronological structure of narrative nonfiction versus the problem-solution framework common in persuasive writing. Each genre carries unique conventions that students must master: explanatory texts require clear topic sentences and supporting evidence, whilst biographical writing demands careful sequencing of events and character development techniques.

Teachers should introduce genre characteristics through mentor texts that exemplify strong structural elements, allowing students to analyse and internalise patterns before attempting their own writing. For instance, when teaching report writing, students might examine how professional writers use headings, subheadings, and topic sentences to guide readers through complex information. This analytical approach, supported by Graham and Perin's research on effective writing instruction, helps students understand that structure serves purpose rather than existing as arbitrary rules.

Practical classroom implementation involves creating genre-specific writing frames and checklists that students can reference during drafting and revision. Teachers might develop separate rubrics for different genres, emphasising the particular strengths each form requires, such as vivid description in travel writing or logical argumentation in opinion pieces.

Nonfiction writing helps students share their ideas and understanding. critical thinking and information skills matter more than ever. Students need to write clearly about facts and real topics to succeed in school and beyond.

To write good nonfiction, students need the right tools and techniques. Developing strong nonfiction writing skills requires practice and guidance. Using text features, picking interesting topics, and adding visual aids all help students organise their thoughts. Confidence grows when students get the right scaffolding at each step.

This article covers key strategies for teaching nonfiction writing. We look at approaches for both younger and older students, plus ways to blend traditional writing with digital tools.

Nonfiction writing plays a key role in education. One good way to teach it is through read-alouds. Teachers can show students how nonfiction texts are built. These sessions spark discussions and help students understand nonfiction structure.

Today's classrooms have access to many nonfiction books. A classroom library filled with nonfiction gives students a chance to explore different styles. As students read more nonfiction, they learn to navigate these texts with confidence.

Choosing books that match students' interests boosts engagement. When reading feels relevant, students enjoy it more. Research shows that students who read a wide range of nonfiction build stronger vocabulary and knowledge.

The practical applications of nonfiction writing extend far beyond the classroom walls. In today's digital age, students regularly encounter and create informational texts through social media posts, blog entries, and online discussions. Teaching strategies that emphasise nonfiction writing help students navigate this landscape critically, enabling them to distinguish between reliable sources and misinformation whilst developing their own credible voice.

Effective classroom practice demonstrates that nonfiction writing instruction strengthens students' analytical thinking skills. When pupils engage with explanatory texts, persuasive essays, and investigative reports, they learn to evaluate evidence, construct logical arguments, and synthesise information from multiple sources. These cognitive processes support student development across the curriculum, particularly in subjects requiring critical analysis and problem-solving.

Moreover, nonfiction writing serves as a powerful tool for inclusive education. Unlike creative writing, which may favour students with particular imaginative strengths, informational writing offers multiple pathways for success. Students can excel through research skills, logical reasoning, or clear exposition, making writing instruction more accessible to diverse learners and building confidence across different learning styles.

Teaching nonfiction writing involves several skills: planning, writing, revising, editing, and publishing. Each step matters. Teachers should cover the whole process, not just one part.

Teachers can help by giving students chances to explore real-world texts together. This builds both research and writing skills. Lessons work best when organised around five main purposes: informing, instructing, narrating, persuading, and responding.

Finding topics that interest students is key to keeping them motivated. Teaching summary writing helps students learn to be clear and focused when working with nonfiction texts.

Text features serve three main purposes: they help readers find information, deepen understanding, and expand knowledge on the topic. Visual features like photos, illustrations, and graphics spark prior knowledge and encourage questions.

Graphic organisers help students identify and use good reading strategies. Think of them as maps through complex information. Games and activities that teach text features make learning fun and memorable.

When nonfiction topics connect to students' lives and interests, motivation rises. Regular exposure to nonfiction helps students get better at navigating different formats and structures.

Working together on nonfiction texts helps students develop their voice while improving clarity and organisation. Rich discussions build vocabulary and content knowledge, setting a strong foundation for reading comprehension.

The Structural Learning Toolkit helps students become confident nonfiction writers. Here are key approaches from the toolkit:

Exploratory talk: Questioning and discussing ideas before writing helps students develop their thoughts. Talk tools encourage students to share ideas about different types of nonfiction. These discussions prepare students to write more effectively.

Visual planning: Graphic organisers help students map out their ideas so information flows logically. This is especially useful for nonfiction writing where complex content needs clear organisation. Oracy skills developed through discussion also support students with special educational needs in expressing their understanding.

Effective implementation begins with introducing students to text structure templates that correspond to different types of nonfiction writing. For persuasive essays, teachers might provide frameworks highlighting claim, evidence, and counterargument sections, whilst explanatory texts benefit from chronological or sequential organisers. These visual scaffolds help students understand how information flows logically within different genres, making the writing process more manageable and purposeful.

Regular practice with structural frameworks also develops students' critical reading skills alongside their writing abilities. When students recognise organisational patterns in published texts, they can apply these same structures to their own compositions with greater confidence. Teachers can enhance this connection by using mentor texts that exemplify clear structural patterns, encouraging students to analyse how professional writers organise their ideas before attempting similar approaches in their own work.

The benefits extend beyond immediate writing improvement, as students develop transferable skills for academic success across subjects. History essays, science reports, and geography investigations all require similar organisational thinking, making structural learning a valuable cross-curricular tool that supports student development throughout their educational journey.

Effective assessment of nonfiction writing requires a multifaceted approach that evaluates both content accuracy and writing craft. Research by Graham and Perin demonstrates that students benefit most from feedback that addresses specific elements such as organisation, evidence use, and clarity of argument. Teachers should develop rubrics that explicitly outline expectations for genre-specific features, whether assessing persuasive essays, explanatory texts, or research reports. This targeted approach helps students understand the distinct requirements of different nonfiction forms.

Formative feedback proves more valuable than summative assessment alone in developing student writing competency. Two-stars-and-a-wish feedback structures work particularly well for nonfiction pieces, allowing teachers to highlight successful elements whilst providing focused improvement targets. Peer assessment activities, when scaffolded with clear criteria, enable students to recognise effective techniques in others' work and transfer these insights to their own writing. Audio feedback can be especially powerful for nonfiction assessment, as teachers can explain complex reasoning about evidence selection or structural choices more efficiently than through written comments.

Successful nonfiction writing instruction integrates assessment throughout the writing process rather than only at completion. Conference-style discussions during drafting stages allow teachers to guide students' research choices, help them evaluate source credibility, and support their developing arguments. This ongoing dialogue transforms assessment from judgement into genuine learning support, developing student confidence in tackling challenging nonfiction writing tasks.

Effective nonfiction writing instruction requires flexible approaches that accommodate the diverse learning profiles found . John Sweller's cognitive load theory demonstrates that students process information differently, suggesting that teachers must vary their instructional methods to prevent overwhelming learners whilst maintaining appropriate challenge levels. For students with additional learning needs, this might involve breaking complex writing tasks into smaller, sequential steps, whilst advanced learners benefit from extended research opportunities and sophisticated organisational structures.

English as an Additional Language (EAL) students require particular consideration in nonfiction writing instruction. Research by Pauline Gibbons shows that providing language frames and sentence starters helps these learners access content whilst developing academic writing conventions. Visual supports, such as graphic organisers and topic-specific vocabulary walls, enable EAL students to focus on content development rather than struggling with linguistic structures alone.

Practical differentiation strategies include offering choice in writing formats (reports, explanations, or persuasive texts), adjusting research requirements based on reading levels, and implementing peer collaboration structures. Teachers can also differentiate assessment by focusing on individual progress rather than comparing all students against identical criteria, ensuring that every learner experiences success whilst working towards increasingly sophisticated nonfiction writing skills.

Nonfiction writing presents unique challenges that differ significantly from creative writing tasks. Students often struggle with selecting and organising relevant information, particularly when transitioning from narrative structures they know well to expository formats. Research by cognitive scientist John Swales demonstrates that students frequently attempt to apply story-telling techniques to informational texts, resulting in chronological organisation rather than logical argument structures. Additionally, many learners find difficulty in adopting an appropriate academic tone whilst maintaining reader engagement.

Effective solutions begin with explicit instruction in text structures before students attempt independent writing. Introduce graphic organisers that match specific nonfiction formats, such as cause-and-effect charts or compare-and-contrast matrices. Provide sentence stems and transitional phrases to support students in connecting ideas logically. For tone development, share exemplar texts and guide students through identifying formal versus informal language choices, helping them recognise how word selection impacts credibility and clarity.

Implement scaffolded practice opportunities that gradually release responsibility to students. Begin with collaborative research and outline creation, then progress to independent writing with teacher conferencing. Regular peer review sessions, focused on specific criteria such as evidence quality or paragraph organisation, help students internalise nonfiction conventions whilst developing critical evaluation skills essential for their own revision process.

Effective nonfiction writing instruction requires teachers to recognise that different genres demand distinct structural frameworks and cognitive approaches. Research by Kellogg and Raulerson demonstrates that students benefit significantly when teachers explicitly model genre-specific organisational patterns, such as the chronological structure of narrative nonfiction versus the problem-solution framework common in persuasive writing. Each genre carries unique conventions that students must master: explanatory texts require clear topic sentences and supporting evidence, whilst biographical writing demands careful sequencing of events and character development techniques.

Teachers should introduce genre characteristics through mentor texts that exemplify strong structural elements, allowing students to analyse and internalise patterns before attempting their own writing. For instance, when teaching report writing, students might examine how professional writers use headings, subheadings, and topic sentences to guide readers through complex information. This analytical approach, supported by Graham and Perin's research on effective writing instruction, helps students understand that structure serves purpose rather than existing as arbitrary rules.

Practical classroom implementation involves creating genre-specific writing frames and checklists that students can reference during drafting and revision. Teachers might develop separate rubrics for different genres, emphasising the particular strengths each form requires, such as vivid description in travel writing or logical argumentation in opinion pieces.

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/teaching-nonfiction-writing#article","headline":"Teaching Nonfiction Writing","description":"Discover effective strategies to develop non-fiction writing skills in the classroom, empowering students to become confident and independent writers.","datePublished":"2024-09-09T11:31:50.708Z","dateModified":"2026-01-26T10:09:32.212Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/teaching-nonfiction-writing"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/6950287f39b8b4221b94e01f_oqk0id.webp","wordCount":2428},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/teaching-nonfiction-writing#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"Teaching Nonfiction Writing","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/teaching-nonfiction-writing"}]},{"@type":"FAQPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/teaching-nonfiction-writing#faq","mainEntity":[{"@type":"Question","name":"What are the five key purposes that should organise nonfiction writing instruction?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"The five main purposes are informing, instructing, narrating, persuading, and responding. Teachers should structure their lessons around these purposes rather than focusing on isolated writing skills. This approach helps students understand why they are writing and provides clear frameworks for diff"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"How can teachers effectively use read-alouds to support nonfiction writing instruction?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Teachers should use read-alouds to demonstrate how nonfiction texts are structured and organised. These sessions help students understand text features whilst building vocabulary and sparking discussions about the content. Regular exposure through teacher-led reading helps students navigate nonficti"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What role do visual elements and text features play in student nonfiction writing?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Visual elements like illustrations, labels, captions, and graphics serve three main purposes: helping readers find information, deepening understanding, and expanding knowledge on topics. Students should learn to use these features strategically to help readers navigate their writing. Combining text"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"How can exploratory talk improve students' nonfiction writing before they begin drafting?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Encouraging students to discuss their ideas before writing helps them develop clearer thinking and organise their thoughts more effectively. These rich discussions build vocabulary and content knowledge whilst helping students find their voice. Talk tools and collaborative exploration prepare studen"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What practical strategies work best for helping younger students develop nonfiction writing skills?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Younger students benefit from scaffolding approaches that include collaborative research activities and extended writing units focused on specific nonfiction types. Teachers should adapt lessons designed for Years 4 to 8 and provide hands-on tools like block building kits to help students physically"}}]}]}