Thinking Hard Strategies: A Teacher's Guide

Discover proven Thinking Hard strategies that boost student engagement by 20% and develop critical thinking skills through deeper cognitive challenges.

Discover proven Thinking Hard strategies that boost student engagement by 20% and develop critical thinking skills through deeper cognitive challenges.

In the field of education, the concept of 'thinking hard' strategies is gaining traction as a means to creates deeper cognitive engagement among students. These strategies are essentially classroom techniques designed to challenge students to engage in more complex tasks, thereby enhancing their critical thinking skills.

| Feature | Difficult Questions | Universal Thinking Framework | Graphic Organisers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Best For | Developing synthesis and analysis skills | Developing metacognitive abilities | Making abstract concepts concrete |

| Key Strength | 20% boost in student engagement | Seven months additional progress gains | Visual learning that enhances retention |

| Limitation | Requires careful scaffolding for struggling learners | Takes time to teach and implement | May oversimplify complex relationships |

| Age Range | Middle school through college | Upper elementary through adult learners | All ages, adapted to complexity level |

One of the key elements of these strategies is the use of difficult questions. Rather than simply asking students to recall information, these questions require them to apply, analyse, and synthesize the knowledge they've acquired. This approach aligns with the assertion of an educational expert who once said, "The quality of student thinking is directly proportional to the quality of the questions they are asked."

Another critical aspect of 'thinking hard' strategies is the emphasis on creating a classroom environment that encourages intellectual risk-taking. This involves cultivating a culture where students feel safe to tackle challenging problems, make mistakes, and learn from them. According to a recent study, classrooms that creates such an environment see a 20% increase in learner participation.

Incorporating these strategies into everyday teaching practice can be transformative. For instance, a teacher might present a complex task related to a topic being studied and then facilitate a class discussion where students are encouraged to ask key questions, propose solutions, and critique each other's ideas. This not only promotes critical thinking but also creates a sense of intellectual curiosity and a love for learning.

'Thinking hard' strategies represent a powerful tool for educators seeking to enhance student engagement and learning outcomes. By challenging students with difficult questions and complex tasks, we can help them develop the critical thinking skills they need to thrive in an increasingly complex world.

Thinking hard strategies are classroom techniques designed to challenge students to engage in complex tasks that enhance critical thinking skills. These strategies move beyond simple recall questions to require students to apply, analyse, and synthesize knowledge. Research shows these approaches can boost student involvement by 20% when implemented effectively.

As we examine deeper into the field of 'thinking hard' strategies, we begin to see their potential as a key to unlockinga treasure chest of cognitive abilities. These strategies, when effectively implemented, can transform the classroom into a bustling marketplace of ideas, where students are the active traders of knowledge and critical thought.

A cornerstone of these teaching strategies is metacognition, or the ability to think about one's own thinking. This self-reflective process allows students to monitor their understanding, identify areas of confusion, and adjust their learning strategies accordingly. A study by the Education Endowment Foundation found that metacognitive strategies can lead to an average gain of seven months' additional progress.

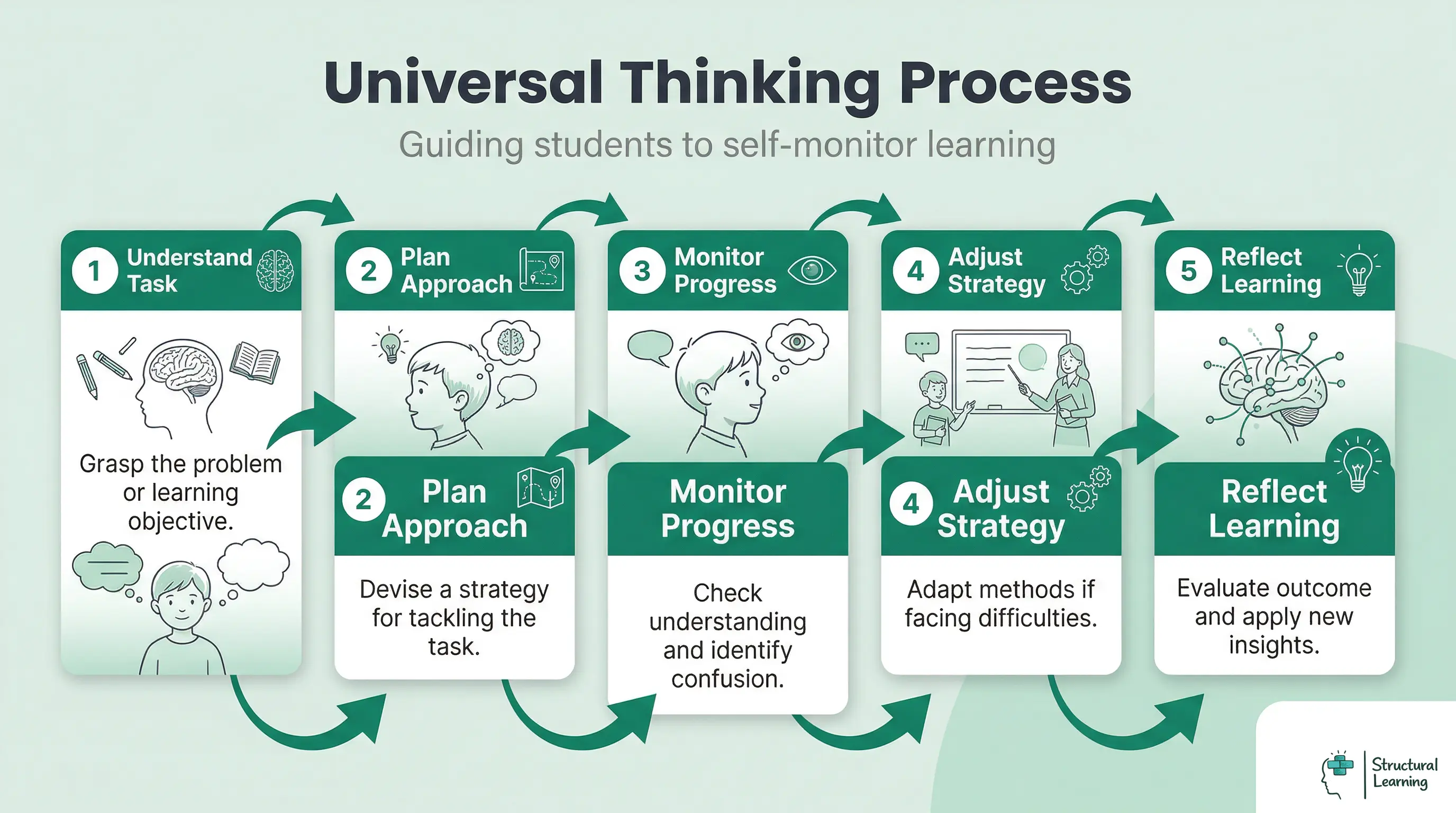

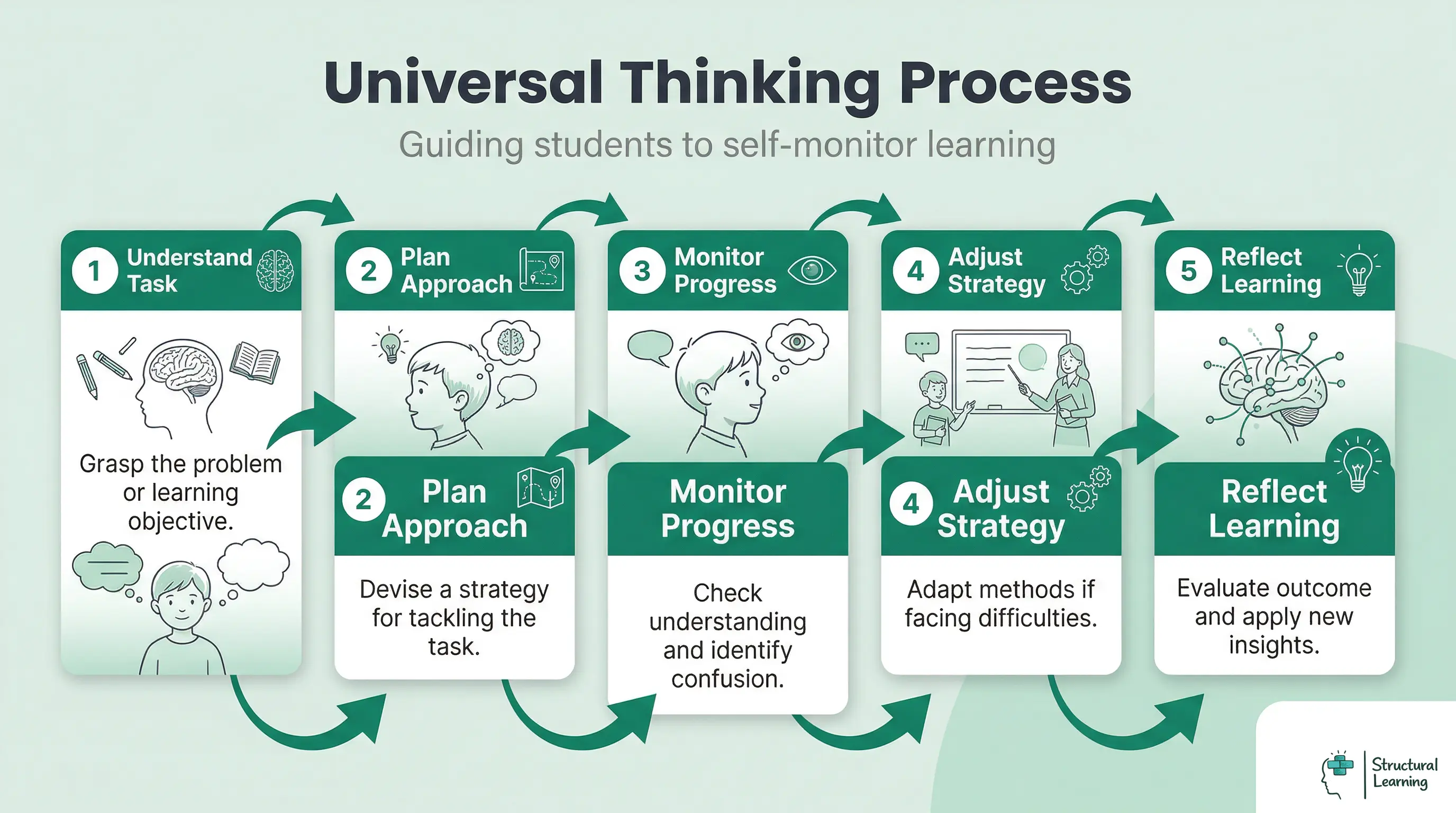

The Universal Thinking Framework is a powerful tool that can be used to creates metacognition. This framework provides a structured approach to thinking, helping students navigate complex tasks and reflective questions. It's like a roadmap for the mind, guiding students throughthe twists and turns of critical thought.

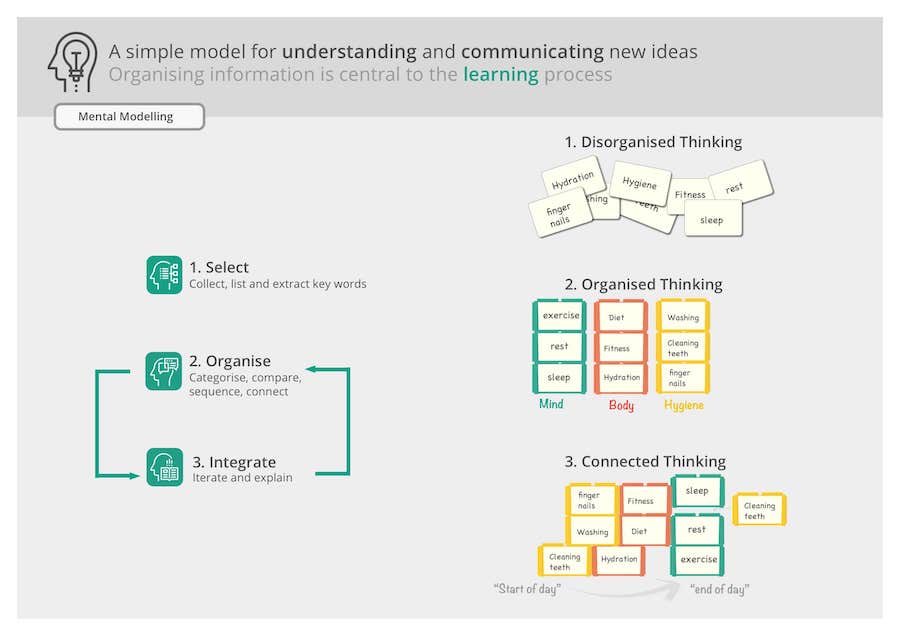

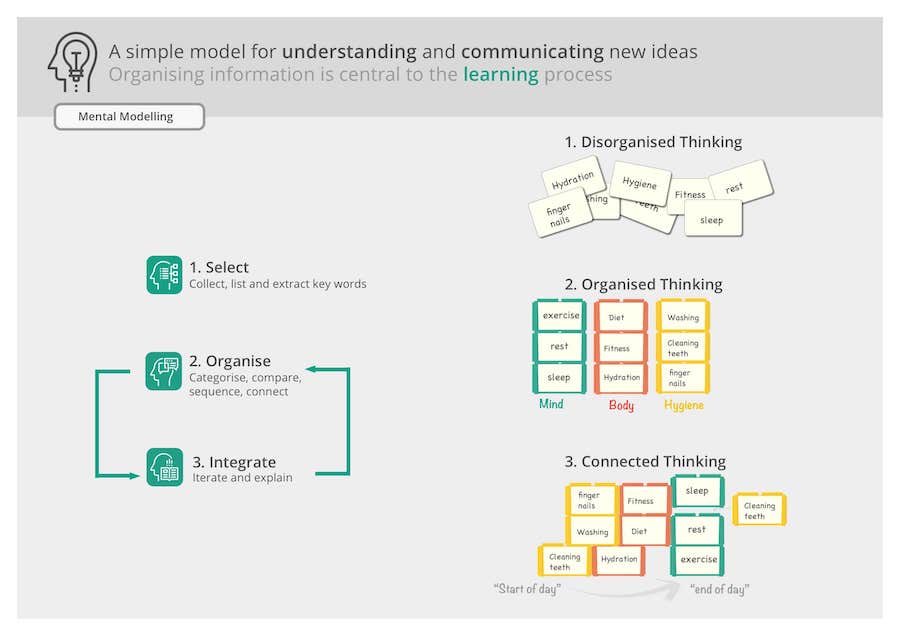

Graphic organisers are another effective learning strategy that can be used to support 'thinking hard' strategies. These visual tools help students organise their thoughts, making abstract ideas more concrete and manageable. According to Evidence-Based Education, the use of graphic organisers can increase student achievement by 29 percentile points.

Ultimately, the power of 'thinking hard' strategies lies in their ability to make the most of lesson time. By challenging students to engage deeply with the material, these strategies not only enhance learning outcomes but also creates a lifelong love for learning.

Teachers increase cognitive engagement by shifting from recall questions to synthesis questions that require deeper thinking. The Universal Thinking Framework helps students think about their own thinking process, leading to seven months of additional academic progress. Creating challenging tasks that connect to real-world applications also significantly enhances cognitive effort.

Building on the foundation of 'thinking hard' strategies, we can further enhance cognitive effort by incorporating a variety of techniques into the learning process. These strategies act as a toolbox, each tool designed to stimulate different aspects of cognitive effort and promote deep thinking.

By incorporating these strategies into the classroom, we can create an environment that not only promotes 'thinking hard', but also creates a culture of curiosity and lifelong learning.

Effective techniques include using difficult questions that require analysis and synthesis rather than simple recall. Block Building and graphic organisers help students visualize complex concepts and make abstract ideas tangible. Teachers should also incorporate metacognition exercises where students reflect on their thinking processes.

In the field of 'thinking hard' strategies, critical thinking holds a special place. It's the art of analysing, evaluating, and creating, going beyond mere recall of facts to a deeper understanding of concepts. As we've seen with the Structural Learning's Block Building Strategy and the use of graphic organisers, visual thinking strategies can play a significant role in promoting critical thinking.

Visual mapping of concepts helps learners externalise their thinking and identify connections — an approach known as Map It in the Structural Learning framework.

One such strategy is Dual Coding. This approach combines verbal and visual information to enhance understanding and recal l. It's like having a conversation with a picture, where the image and words work together to tell a more complete story.

Thinking Maps, another visual tool, can also be used to promote critical thinking. These diagrams represent different cognitive processes and can be used to visually organise and connect ideas. They're like the blueprints of thought, providing a clear structure for complex thinking processes.

Oracy, the ability to express oneself fluently and grammatically in speech, is another critical aspect of critical thinking. It's about more than just speaking; it's about communicating effectively, presenting arguments, and engaging in meaningful discussions. Techniques such as talk partners and structured dialogues can be used to promote oracy in the classroom.

Finally, promoting independent learning is a key aspect of effective teaching. By encouraging students to take ownership of their learning, we can creates a sense of curiosity and a desire to engage in higher-order thinking. This could involve setting challenging tasks, providing opportunities for self-reflection, or using alternative thinking strategies to explore different perspectives.

By integrating these techniques and approaches into our teaching strategies, we can help students not only think hard, but also think critically, creatively, and independently.

Rigorous thinking improves problem-solving by forcing students to work through complex challenges rather than relying on memorized solutions. This approach builds neural pathways that transfer to new situations and problems. Students who regularly engage in challenging cognitive tasks develop stronger analytical skills and creative problem-solving approaches.

In the journey of developing critical thinking, we must not overlook the importance of problem-solving skills. As we've seen with independent learning, students who are equipped with the ability to tackle problems head-on are more likely to succeed acadically and beyond.

One of the key classroom strategies to boost problem-solving skills is the use of rigorous thought, a concept championed by educators like Ron Berger and Doug Lemov. This involves pushing students to think deeply and critically about a topic, rather than simply accepting information at face value.

A unit of study, for example, might involve a series of factual questions that require students to apply their knowledge in new and challenging ways. This active strategy encourages students to engage with the material, rather than passively absorbing it.

Structural Learning's Block Building Strategy is a prime example of this approach. By physically manipulating blocks to represent different aspects of a problem, students are encouraged to think critically and creatively about the task at hand.

Moreover, alternate thinking strategies can also be employed to boost problem-solving skills. For instance, students might be encouraged to approach a problem from a different perspective or to use a different method to find a solution.

By integrating these strategies into our teaching, we can help students not only to think hard, but also to solve problems effectively and creatively.

Research demonstrates that classrooms developing intellectual risk-taking see a 20% increase in active learning. Studies show that students using metacognitive frameworks gain seven months of additional academic progress compared to traditional methods. The quality of student thinking directly correlates with the complexity and quality of questions they encounter.

Building on the power of rigorous thought and problem-solving skills, examine into the cognitive science that underpins these effective thinking strategies. The human brain is a complex organ, and understanding how it processes and retains information can greatly enhance our teaching methods.

One of the key concepts in cognitive science is the idea of a schema, a mental framework that helps us organise and interpret information. When we learn something new, we either assimilate it into an existing schema or accommodate it by adjusting our schema or creating a new one. This process of assimilation and accommodation is at the heart of deeper thinking and learning.

Metacognitive strategies, which involve thinking about one's own thinking, can also play a crucial role in effective learning. By reflecting on how they are learning, students can identify the optimal strategy for a given task and adjust their approach as needed.

Interleaved strategy, for example, involves switching between different types of tasks or topics in a single study session. This approach has been shown to improve long-term retention and transfer of skills. In fact, a study found that students who used interleaved practice performed 43% better on a post-test than those who used blocked practice.

Alternative strategies, such as using visual aids or real-world examples, can also be effective in helping students understand complex concepts. These strategies can be particularly useful in subjects like science and math, where abstract concepts can be difficult to grasp.

Understanding the science behind effective thinking strategies can help us design more effective teaching methods and promote deeper, more lasting learning.

Teachers create this culture by establishing a safe environment where mistakes are viewed as learning opportunities rather than failures. Practical steps include praising effort over correct answers and modelling your own thinking processes when solving problems. Regular use of challenging questions combined with supportive feedback encourages students to tackle difficult problems without fear.

Building on the science behind effective thinking strategies, let's explore some practical tips for cultivating a mindset for intensive thinking in the classroom. These strategies can be adapted for both primary and secondary school classrooms:

By implementing these strategies, teachers can creates a classroom environment that encourages intensive thinking and promotes deeper learning. For more insights, this article provides a comprehensive review of critical thinking strategies in the classroom.

Thinking Hard Strategies are classroom techniques designed to challenge students with complex tasks that enhance critical thinking skills, moving beyond simple recall questions to require analysis, synthesis, and application of knowledge. Unlike traditional methods that focus on memorisation, these strategies create deeper cognitive engagement and can boost student involvement by 20% when implemented effectively.

The Universal Thinking Framework provides a structured approach to thinking that helps students navigate complex tasks and develop metacognitive abilities. Teachers can use this framework as a roadmap for students' minds, guiding them through critical thought processes and helping them monitor their own understanding, which research shows can lead to seven months of additional academic progress.

Rather than asking students to simply recall information, difficult questions require them to apply, analyse, and synthesise knowledge they've acquired. For example, instead of asking 'What happened in 1066?', teachers might ask 'How would British society have developed differently if the Norman Conquest had failed, and what evidence supports your analysis?'

Graphic organisers provide visual tools that help students organise their thoughts and make abstract ideas more concrete and manageable, with research showing they can increase student achievement by 29 percentile points. Block Building uses physical blocks to represent abstract ideas, creating a 3D model of thoughts that provides both visual and tactile ways to explore complex concepts.

The main challenges include the need for careful scaffoldingfor struggling learners, the time required to teach and implement these strategies effectively, and the risk of oversimplifying complex relationships through visual tools. Teachers can overcome these by gradually introducing strategies, providing adequate support for different ability levels, and ensuring visual representations complement rather than replace deeper understanding.

Teachers need to cultivate an environment where students feel safe to tackle challenging problems, make mistakes, and learn from them without fear of failure. This involves celebrating intellectual curiosity, treating mistakes as learning opportunities, and encouraging students to ask questions, propose solutions, and critique each other's ideas during class discussions.

Research demonstrates significant measurable benefits, including a 20% boost in student engagement when shifting from recall to synthesis questions, and seven months of additional progress when students develop metacognitive abilities through structured thinking frameworks. Studies by the Education Endowment Foundation and Evidence-Based Education support these findings with concrete data on academic improvement.

These peer-reviewed studies provide deeper insights into thinking hard strategies and its application in educational settings.

Embracing the future of Artificial Intelligence in the classroom: the relevance of AI literacy, prompt engineering, and critical thinking in modern education View study ↗544 citations

Walter et al. (2024)

This paper examines how artificial intelligence is transforming education and emphasises the need for students to develop AI literacy, prompt engineering skills, and critical thinking abilities. It's relevant to teachers implementing thinking hard strategies because it shows how AI tools can both support and challenge traditional approaches to developing critical thinking, requiring educators to adapt their methods for the digital age.

Metacognitive Strategies and Development of Critical Thinking in Higher Education 167 citations

Rivas et al. (2022)

This research explores how metacognitive strategies can be used to develop critical thinking skills in higher education students. It's valuable for teachers using thinking hard strategies because it demonstrates that students need to be conscious of and regulate their own thinking processes to effectively apply critical thinking skills in academic work.

Scaffolding Complex Learning: The Mechanisms of Structuring and Problematizing Student Work 656 citations

Reiser et al. (2004)

This paper investigates how software tools can scaffold students through complex learning tasks by providing structured support that enables them to handle more challenging content than they could manage independently. It's relevant to thinking hard strategies because it shows teachers how to provide the right level of support to help students engage with difficult material without removing the cognitive challenge entirely.

Research on gamification's impact on student motivation 51 citations (Author, Year) demonstrates how game-based elements in educational settings can significantly enhance learner engagement and academic performance across diverse learning environments.

García-López et al. (2023)

This study examines how gamification techniques affect student motivation, engagement, and academic performance in classroom settings. It's useful for teachers implementing thinking hard strategies because it provides evidence on how game-based elements can motivate students to persist through challenging cognitive tasks while maintaining high levels of engagement.

Research on questioning techniques in classroom instruction 53 citations (Author, Year) explores how teachers can effectively use different types of questions to promote deeper learning, critical thinking, and student engagement across various educational contexts.

Shanmugavelu et al. (2020)

This research analyses the effectiveness of different questioning techniques teachers use in the classroom and their impact on student learning and feedback. For thinking hard strategies because effective questioning is a core method for promoting deep thinking, helping teachers guide students through complex reasoning processes and assess their understanding.

In the field of education, the concept of 'thinking hard' strategies is gaining traction as a means to creates deeper cognitive engagement among students. These strategies are essentially classroom techniques designed to challenge students to engage in more complex tasks, thereby enhancing their critical thinking skills.

| Feature | Difficult Questions | Universal Thinking Framework | Graphic Organisers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Best For | Developing synthesis and analysis skills | Developing metacognitive abilities | Making abstract concepts concrete |

| Key Strength | 20% boost in student engagement | Seven months additional progress gains | Visual learning that enhances retention |

| Limitation | Requires careful scaffolding for struggling learners | Takes time to teach and implement | May oversimplify complex relationships |

| Age Range | Middle school through college | Upper elementary through adult learners | All ages, adapted to complexity level |

One of the key elements of these strategies is the use of difficult questions. Rather than simply asking students to recall information, these questions require them to apply, analyse, and synthesize the knowledge they've acquired. This approach aligns with the assertion of an educational expert who once said, "The quality of student thinking is directly proportional to the quality of the questions they are asked."

Another critical aspect of 'thinking hard' strategies is the emphasis on creating a classroom environment that encourages intellectual risk-taking. This involves cultivating a culture where students feel safe to tackle challenging problems, make mistakes, and learn from them. According to a recent study, classrooms that creates such an environment see a 20% increase in learner participation.

Incorporating these strategies into everyday teaching practice can be transformative. For instance, a teacher might present a complex task related to a topic being studied and then facilitate a class discussion where students are encouraged to ask key questions, propose solutions, and critique each other's ideas. This not only promotes critical thinking but also creates a sense of intellectual curiosity and a love for learning.

'Thinking hard' strategies represent a powerful tool for educators seeking to enhance student engagement and learning outcomes. By challenging students with difficult questions and complex tasks, we can help them develop the critical thinking skills they need to thrive in an increasingly complex world.

Thinking hard strategies are classroom techniques designed to challenge students to engage in complex tasks that enhance critical thinking skills. These strategies move beyond simple recall questions to require students to apply, analyse, and synthesize knowledge. Research shows these approaches can boost student involvement by 20% when implemented effectively.

As we examine deeper into the field of 'thinking hard' strategies, we begin to see their potential as a key to unlockinga treasure chest of cognitive abilities. These strategies, when effectively implemented, can transform the classroom into a bustling marketplace of ideas, where students are the active traders of knowledge and critical thought.

A cornerstone of these teaching strategies is metacognition, or the ability to think about one's own thinking. This self-reflective process allows students to monitor their understanding, identify areas of confusion, and adjust their learning strategies accordingly. A study by the Education Endowment Foundation found that metacognitive strategies can lead to an average gain of seven months' additional progress.

The Universal Thinking Framework is a powerful tool that can be used to creates metacognition. This framework provides a structured approach to thinking, helping students navigate complex tasks and reflective questions. It's like a roadmap for the mind, guiding students throughthe twists and turns of critical thought.

Graphic organisers are another effective learning strategy that can be used to support 'thinking hard' strategies. These visual tools help students organise their thoughts, making abstract ideas more concrete and manageable. According to Evidence-Based Education, the use of graphic organisers can increase student achievement by 29 percentile points.

Ultimately, the power of 'thinking hard' strategies lies in their ability to make the most of lesson time. By challenging students to engage deeply with the material, these strategies not only enhance learning outcomes but also creates a lifelong love for learning.

Teachers increase cognitive engagement by shifting from recall questions to synthesis questions that require deeper thinking. The Universal Thinking Framework helps students think about their own thinking process, leading to seven months of additional academic progress. Creating challenging tasks that connect to real-world applications also significantly enhances cognitive effort.

Building on the foundation of 'thinking hard' strategies, we can further enhance cognitive effort by incorporating a variety of techniques into the learning process. These strategies act as a toolbox, each tool designed to stimulate different aspects of cognitive effort and promote deep thinking.

By incorporating these strategies into the classroom, we can create an environment that not only promotes 'thinking hard', but also creates a culture of curiosity and lifelong learning.

Effective techniques include using difficult questions that require analysis and synthesis rather than simple recall. Block Building and graphic organisers help students visualize complex concepts and make abstract ideas tangible. Teachers should also incorporate metacognition exercises where students reflect on their thinking processes.

In the field of 'thinking hard' strategies, critical thinking holds a special place. It's the art of analysing, evaluating, and creating, going beyond mere recall of facts to a deeper understanding of concepts. As we've seen with the Structural Learning's Block Building Strategy and the use of graphic organisers, visual thinking strategies can play a significant role in promoting critical thinking.

Visual mapping of concepts helps learners externalise their thinking and identify connections — an approach known as Map It in the Structural Learning framework.

One such strategy is Dual Coding. This approach combines verbal and visual information to enhance understanding and recal l. It's like having a conversation with a picture, where the image and words work together to tell a more complete story.

Thinking Maps, another visual tool, can also be used to promote critical thinking. These diagrams represent different cognitive processes and can be used to visually organise and connect ideas. They're like the blueprints of thought, providing a clear structure for complex thinking processes.

Oracy, the ability to express oneself fluently and grammatically in speech, is another critical aspect of critical thinking. It's about more than just speaking; it's about communicating effectively, presenting arguments, and engaging in meaningful discussions. Techniques such as talk partners and structured dialogues can be used to promote oracy in the classroom.

Finally, promoting independent learning is a key aspect of effective teaching. By encouraging students to take ownership of their learning, we can creates a sense of curiosity and a desire to engage in higher-order thinking. This could involve setting challenging tasks, providing opportunities for self-reflection, or using alternative thinking strategies to explore different perspectives.

By integrating these techniques and approaches into our teaching strategies, we can help students not only think hard, but also think critically, creatively, and independently.

Rigorous thinking improves problem-solving by forcing students to work through complex challenges rather than relying on memorized solutions. This approach builds neural pathways that transfer to new situations and problems. Students who regularly engage in challenging cognitive tasks develop stronger analytical skills and creative problem-solving approaches.

In the journey of developing critical thinking, we must not overlook the importance of problem-solving skills. As we've seen with independent learning, students who are equipped with the ability to tackle problems head-on are more likely to succeed acadically and beyond.

One of the key classroom strategies to boost problem-solving skills is the use of rigorous thought, a concept championed by educators like Ron Berger and Doug Lemov. This involves pushing students to think deeply and critically about a topic, rather than simply accepting information at face value.

A unit of study, for example, might involve a series of factual questions that require students to apply their knowledge in new and challenging ways. This active strategy encourages students to engage with the material, rather than passively absorbing it.

Structural Learning's Block Building Strategy is a prime example of this approach. By physically manipulating blocks to represent different aspects of a problem, students are encouraged to think critically and creatively about the task at hand.

Moreover, alternate thinking strategies can also be employed to boost problem-solving skills. For instance, students might be encouraged to approach a problem from a different perspective or to use a different method to find a solution.

By integrating these strategies into our teaching, we can help students not only to think hard, but also to solve problems effectively and creatively.

Research demonstrates that classrooms developing intellectual risk-taking see a 20% increase in active learning. Studies show that students using metacognitive frameworks gain seven months of additional academic progress compared to traditional methods. The quality of student thinking directly correlates with the complexity and quality of questions they encounter.

Building on the power of rigorous thought and problem-solving skills, examine into the cognitive science that underpins these effective thinking strategies. The human brain is a complex organ, and understanding how it processes and retains information can greatly enhance our teaching methods.

One of the key concepts in cognitive science is the idea of a schema, a mental framework that helps us organise and interpret information. When we learn something new, we either assimilate it into an existing schema or accommodate it by adjusting our schema or creating a new one. This process of assimilation and accommodation is at the heart of deeper thinking and learning.

Metacognitive strategies, which involve thinking about one's own thinking, can also play a crucial role in effective learning. By reflecting on how they are learning, students can identify the optimal strategy for a given task and adjust their approach as needed.

Interleaved strategy, for example, involves switching between different types of tasks or topics in a single study session. This approach has been shown to improve long-term retention and transfer of skills. In fact, a study found that students who used interleaved practice performed 43% better on a post-test than those who used blocked practice.

Alternative strategies, such as using visual aids or real-world examples, can also be effective in helping students understand complex concepts. These strategies can be particularly useful in subjects like science and math, where abstract concepts can be difficult to grasp.

Understanding the science behind effective thinking strategies can help us design more effective teaching methods and promote deeper, more lasting learning.

Teachers create this culture by establishing a safe environment where mistakes are viewed as learning opportunities rather than failures. Practical steps include praising effort over correct answers and modelling your own thinking processes when solving problems. Regular use of challenging questions combined with supportive feedback encourages students to tackle difficult problems without fear.

Building on the science behind effective thinking strategies, let's explore some practical tips for cultivating a mindset for intensive thinking in the classroom. These strategies can be adapted for both primary and secondary school classrooms:

By implementing these strategies, teachers can creates a classroom environment that encourages intensive thinking and promotes deeper learning. For more insights, this article provides a comprehensive review of critical thinking strategies in the classroom.

Thinking Hard Strategies are classroom techniques designed to challenge students with complex tasks that enhance critical thinking skills, moving beyond simple recall questions to require analysis, synthesis, and application of knowledge. Unlike traditional methods that focus on memorisation, these strategies create deeper cognitive engagement and can boost student involvement by 20% when implemented effectively.

The Universal Thinking Framework provides a structured approach to thinking that helps students navigate complex tasks and develop metacognitive abilities. Teachers can use this framework as a roadmap for students' minds, guiding them through critical thought processes and helping them monitor their own understanding, which research shows can lead to seven months of additional academic progress.

Rather than asking students to simply recall information, difficult questions require them to apply, analyse, and synthesise knowledge they've acquired. For example, instead of asking 'What happened in 1066?', teachers might ask 'How would British society have developed differently if the Norman Conquest had failed, and what evidence supports your analysis?'

Graphic organisers provide visual tools that help students organise their thoughts and make abstract ideas more concrete and manageable, with research showing they can increase student achievement by 29 percentile points. Block Building uses physical blocks to represent abstract ideas, creating a 3D model of thoughts that provides both visual and tactile ways to explore complex concepts.

The main challenges include the need for careful scaffoldingfor struggling learners, the time required to teach and implement these strategies effectively, and the risk of oversimplifying complex relationships through visual tools. Teachers can overcome these by gradually introducing strategies, providing adequate support for different ability levels, and ensuring visual representations complement rather than replace deeper understanding.

Teachers need to cultivate an environment where students feel safe to tackle challenging problems, make mistakes, and learn from them without fear of failure. This involves celebrating intellectual curiosity, treating mistakes as learning opportunities, and encouraging students to ask questions, propose solutions, and critique each other's ideas during class discussions.

Research demonstrates significant measurable benefits, including a 20% boost in student engagement when shifting from recall to synthesis questions, and seven months of additional progress when students develop metacognitive abilities through structured thinking frameworks. Studies by the Education Endowment Foundation and Evidence-Based Education support these findings with concrete data on academic improvement.

These peer-reviewed studies provide deeper insights into thinking hard strategies and its application in educational settings.

Embracing the future of Artificial Intelligence in the classroom: the relevance of AI literacy, prompt engineering, and critical thinking in modern education View study ↗544 citations

Walter et al. (2024)

This paper examines how artificial intelligence is transforming education and emphasises the need for students to develop AI literacy, prompt engineering skills, and critical thinking abilities. It's relevant to teachers implementing thinking hard strategies because it shows how AI tools can both support and challenge traditional approaches to developing critical thinking, requiring educators to adapt their methods for the digital age.

Metacognitive Strategies and Development of Critical Thinking in Higher Education 167 citations

Rivas et al. (2022)

This research explores how metacognitive strategies can be used to develop critical thinking skills in higher education students. It's valuable for teachers using thinking hard strategies because it demonstrates that students need to be conscious of and regulate their own thinking processes to effectively apply critical thinking skills in academic work.

Scaffolding Complex Learning: The Mechanisms of Structuring and Problematizing Student Work 656 citations

Reiser et al. (2004)

This paper investigates how software tools can scaffold students through complex learning tasks by providing structured support that enables them to handle more challenging content than they could manage independently. It's relevant to thinking hard strategies because it shows teachers how to provide the right level of support to help students engage with difficult material without removing the cognitive challenge entirely.

Research on gamification's impact on student motivation 51 citations (Author, Year) demonstrates how game-based elements in educational settings can significantly enhance learner engagement and academic performance across diverse learning environments.

García-López et al. (2023)

This study examines how gamification techniques affect student motivation, engagement, and academic performance in classroom settings. It's useful for teachers implementing thinking hard strategies because it provides evidence on how game-based elements can motivate students to persist through challenging cognitive tasks while maintaining high levels of engagement.

Research on questioning techniques in classroom instruction 53 citations (Author, Year) explores how teachers can effectively use different types of questions to promote deeper learning, critical thinking, and student engagement across various educational contexts.

Shanmugavelu et al. (2020)

This research analyses the effectiveness of different questioning techniques teachers use in the classroom and their impact on student learning and feedback. For thinking hard strategies because effective questioning is a core method for promoting deep thinking, helping teachers guide students through complex reasoning processes and assess their understanding.

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/thinking-hard-strategies#article","headline":"Thinking Hard Strategies","description":"Discover proven Thinking Hard strategies that boost student engagement by 20% and develop critical thinking skills through deeper cognitive challenges.","datePublished":"2023-05-26T15:07:38.987Z","dateModified":"2026-03-02T11:00:51.313Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/thinking-hard-strategies"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/69733788e156fc2ff27491ed_69733783e04d553853f3e800_thinking-hard-strategies-illustration.webp","wordCount":3265},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/thinking-hard-strategies#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"Thinking Hard Strategies","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/thinking-hard-strategies"}]},{"@type":"FAQPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/thinking-hard-strategies#faq","mainEntity":[{"@type":"Question","name":"What exactly are Thinking Hard Strategies and how do they differ from traditional teaching methods?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Thinking Hard Strategies are classroom techniques designed to challenge students with complex tasks that enhance critical thinking skills, moving beyond simple recall questions to require analysis, synthesis, and application of knowledge. Unlike traditional methods that focus on memorisation, these "}},{"@type":"Question","name":"How can teachers implement the Universal Thinking Framework in their everyday lessons?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"The Universal Thinking Framework provides a structured approach to thinking that helps students navigate complex tasks and develop metacognitive abilities. Teachers can use this framework as a roadmap for students' minds, guiding them through critical thought processes and helping them monitor their"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What are some practical examples of 'difficult questions' that promote deeper thinking?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Rather than asking students to simply recall information, difficult questions require them to apply, analyse, and synthesise knowledge they've acquired. For example, instead of asking 'What happened in 1066?', teachers might ask 'How would British society have developed differently if the Norman Con"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"How do graphic organisers and Block Building strategies help students with abstract concepts?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Graphic organisers provide visual tools that help students organise their thoughts and make abstract ideas more concrete and manageable, with research showing they can increase student achievement by 29 percentile points. Block Building uses physical blocks to represent abstract ideas, creating a 3D"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What are the main challenges teachers face when implementing Thinking Hard Strategies, and how can they overcome them?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"The main challenges include the need for careful scaffoldingfor struggling learners, the time required to teach and implement these strategies effectively, and the risk of oversimplifying complex relationships through visual tools. Teachers can overcome these by gradually introducing strategies, pro"}}]}]}