Working Memory: A teacher's guide

Discover how understanding working memory transforms your teaching effectiveness. Learn to spot cognitive overload signs and design lessons that work for all pupils.

Discover how understanding working memory transforms your teaching effectiveness. Learn to spot cognitive overload signs and design lessons that work for all pupils.

Working memory (AI tools that respect working memory limitations) is one of the eight executive functions considered necessary for cognitive processes and is central to understanding the psychology of learning. Working memory is the ability to hold information in mind and manipulate it at the same time.

Working memory is important because it helps us process information Working memory is the brain's short-term memory. It helps us remember things we're learning . Working memory is important because it allows us to process information quickly and efficiently.

When we learn something new, our brains store it temporarily in our working memory. We use this temporary storage to keep track of the information until we've learned it well enough to retain it permanently in long-term memory.

Moving information from working memory into long-term storage requires deliberate encoding strategies. Research on encoding strategies for long-term learning identifies techniques such as elaboration, organisation, and visual imagery that help transform fleeting thoughts into durable memories. Teachers who understand these processes can design activities that promote deep encoding rather than superficial processing.

Executive functions, such as working memory, play a crucial role in our ability to learn and process information. They are responsible for our ability to plan, organise, and carry out tasks. Working memory, in particular, allows us to hold information in our minds while we work on other tasks.

It is also important for decision-making, problem-solving, and critical thinking. By improving our executive functions, we can enhance our cognitive abilities and improve our overall performance in work and daily life.

This means that when we learn something new, we need to be able to hold onto the information in our working memory for a period of time. This is where the concept of rehearsal We rehearse information over and over again until we've memorized it. The more times we practice, the better we become at remembering it.

When working memory is strong, we're able to pay attention to multiple things at once, remember where we left off when reading, and keep track of our thoughts and feelings. Students who struggle with working memory often find themselves overwhelmed by the amount of material they need to learn, especially in the early years of school.

They may be unable to retain information long enough to complete assignments, and they may not understand concepts well enough to apply them to real-life situations.

This article will provide you with a teachers' perspective about how the findings from cognitive psychology and Baddeley's working memory model can be applied to classroom practices . Small changes to the way we teach can enable us to get the most out of our students' working memory and achieve long-term learning.

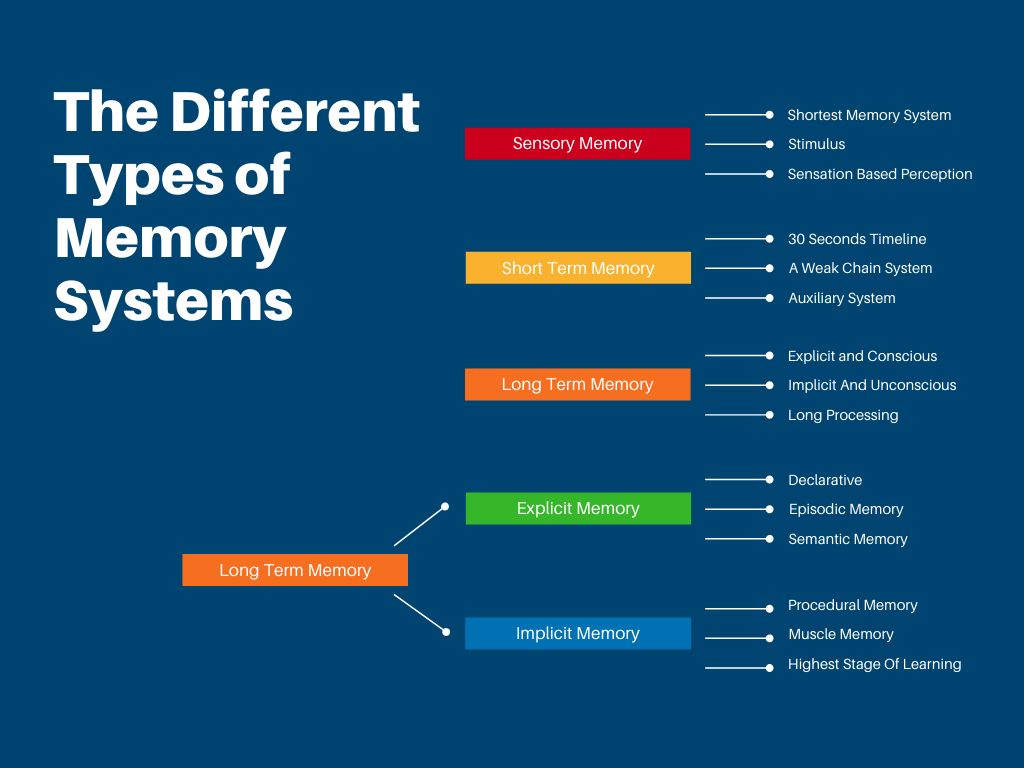

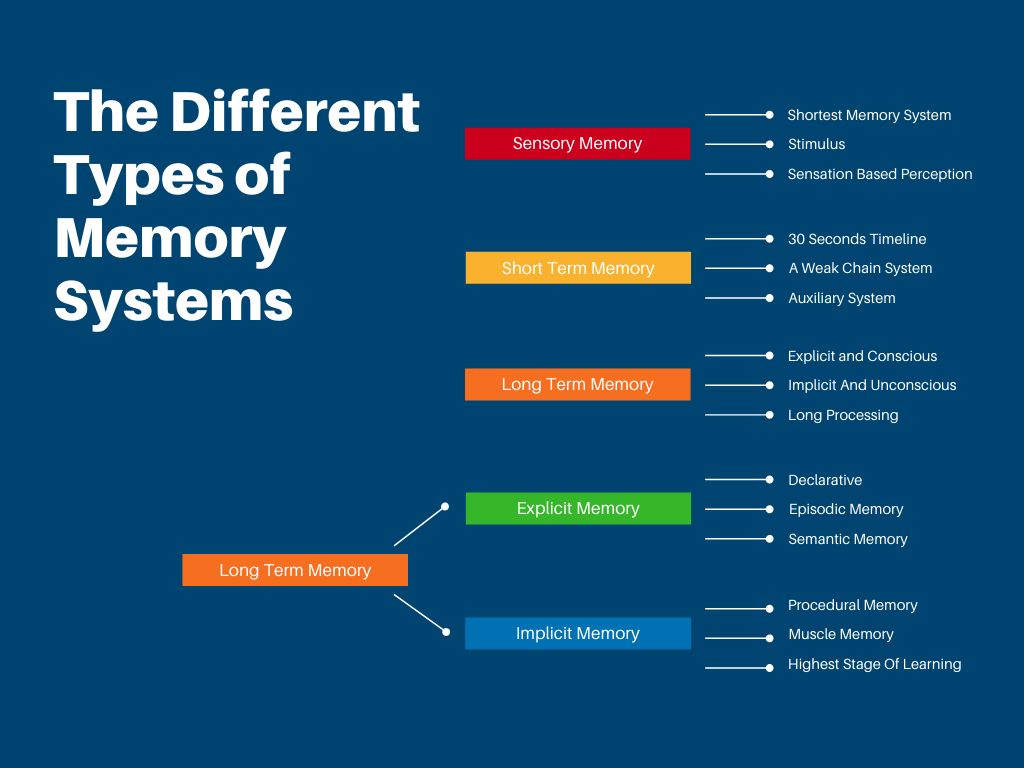

The main types of memory include sensory memory (1-2 seconds), working memory (15-30 seconds), and long-term memory (potentially permanent storage). Working memory acts as the critical gateway between sensory input and long-term storage, allowing us to manipulate information while learning. Teachers need to understand these distinctions to design lessons that effectively move information through each memory stage.

According to the multi-store model of memory, we have three types of memory that are defined by the differences in their duration and capacity:

Our sensory memory processes everything in our environment. There is too much information for us to have conscious awareness of it and it can only remain in our sensory memory for less than a second. We are constantly bombarded with information from our senses; our sensory memory works hard to filter that information and determine if enough for our attention and to be granted access to our short-term memory.

Once information has been deemed important enough to enter our short-term memory, executive processes take over to help us retain and manipulate that information. These processes include attention, rehearsal, and organisation.

Attention allows us to focus on the information we need to remember, while rehearsal helps us repeat the information to ourselves to strengthen its retention.

organisation involves categorising and grouping information to make it easier to remember and recall later on. Without these executive processes, our working memory would not be able to function effectively.

When we actively pay attention to information, it enters our short-term memory where it can stay for up to 30 seconds without too much effort. There are individual differences in the capacity of our short-term memory but most people can retain between 5 and 9 chunks of information at any given time (you may have seen this referred to as '7 plus or minus 2'). Information will leave our short-term memory quickly if it is not processed in some way.

We will see later that repeating information using our inner voice (subvocal rehearsal) or processing the information in a meaningful way (elaborative rehearsal) are two of the cognitive processes required to move information into our long-term memory.

In addition to our general short-term memory capacity, we also have a specialised form of short-term memory called visual short-term memory. This type of memory allows us to hold onto visual information, like images or shapes, for a brief period of time. Studies have shown that visual short-term memory capacity is limited to around 3-4 visual items at a time. This is why we may struggle to remember a long string of numbers or a complex image unless we have a way to process and encode that information into our long-term memory.

If we want to keep information for longer than 30 seconds, we must move it into our long-term memory. This is where information is filed, ready for us to retrieve when we need it. New information is linked with previous learning from related topics to help us retrieve it more effectively in the future. There seems to be no limit to the capacity or duration of our long-term memory. However, having a limitless amount of information means that it can be difficult or sometimes impossible to retrieve a precise piece of information when it is needed.

When learning, activate long-term memory in order to retain information for a longer period of time. This can be done by connecting new information to existing knowledge or experiences, or by repeating the information multiple times in order to strengthen the neural connections in the brain. By actively engaging with the material and making associations with what you already know, you can help transfer the information from short-term memory to activated long-term memory, improving your ability to recall it later on.

If you have read any of my previous articles, you will know that I like to define learning as a permanent addition to the long-term memory that can be readily available when it is needed.

Learning is a two-stage process:

For information to enter the long-term memory, it must be processed by the short-term memory. In the multi-store model of memory, the short-term memory represents a store of information; it does not consider the structure or the cognitive processes required to transfer information into the long-term memory. Baddeley developed the working memory model to address this issue and it is now considered to be an essential component to cognitive development.

| Component | Function | Capacity | Classroom Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Central Executive | Controls attention, coordinates subsystems, manages cognitive processing | Limited attentional resources | Reduce distractions; avoid split attention; sequence tasks rather than multitask |

| Phonological Loop | Processes verbal and acoustic information through inner speech rehearsal | ~2 seconds of speech; ~7 items | Use chunking for verbal instructions; allow rehearsal time; minimise irrelevant speech |

| Visuospatial Sketchpad | Processes visual and spatial information; mental imagery | ~3-4 visual objects | Support verbal with visual; use diagrams and models; reduce visual clutter |

| Episodic Buffer | Integrates information across subsystems and connects to long-term memory | ~4 integrated chunks | Activate prior knowledge; make connections explicit; use stories and narratives |

Based on Baddeley & Hitch's Working Memory Model (1974, updated 2000). Understanding these components helps teachers design instruction that works with, rather than against, cognitive limitations.

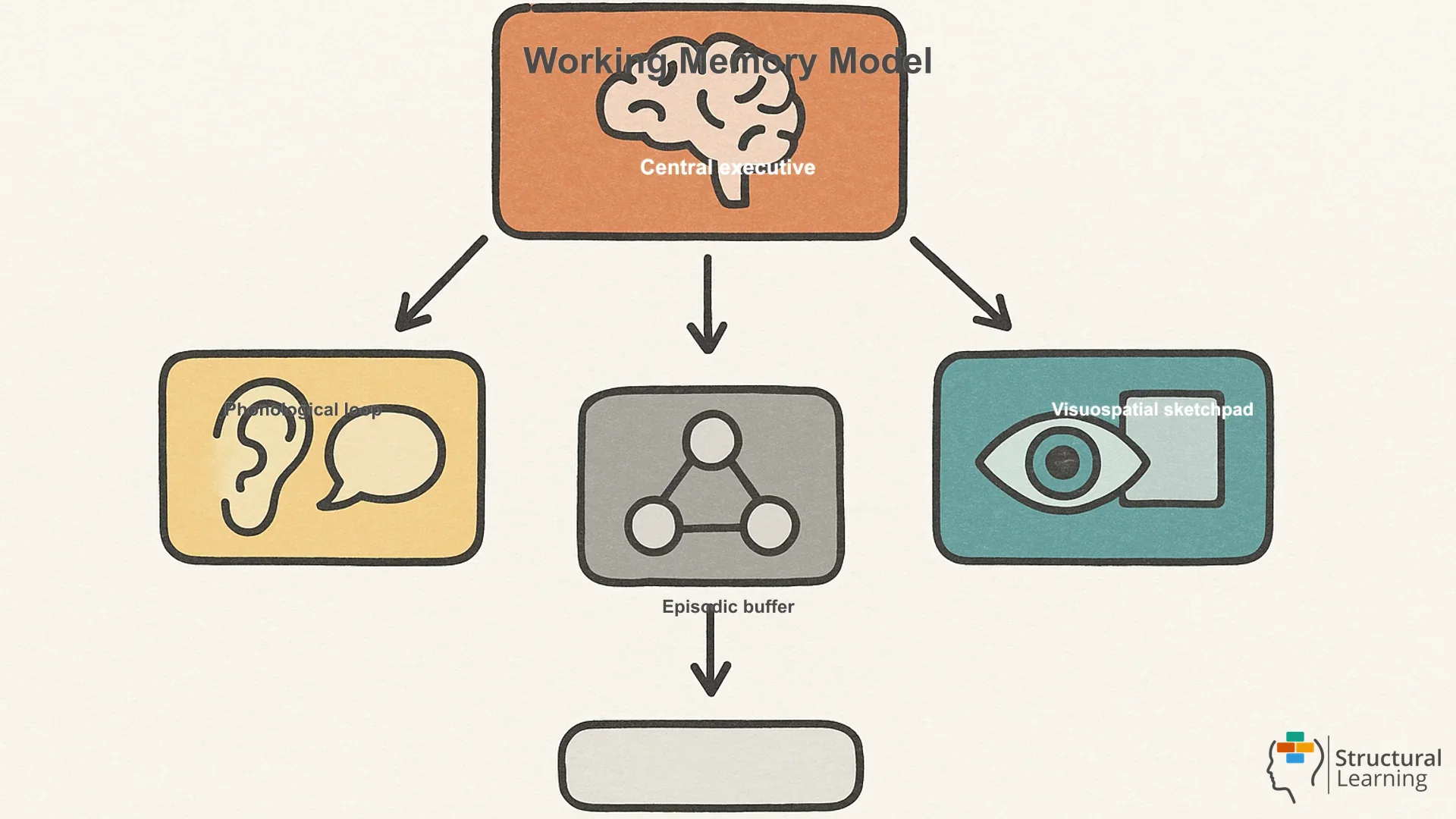

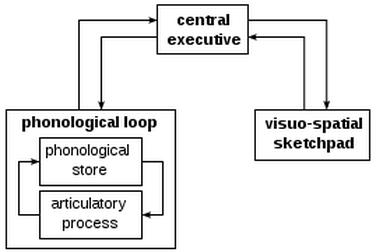

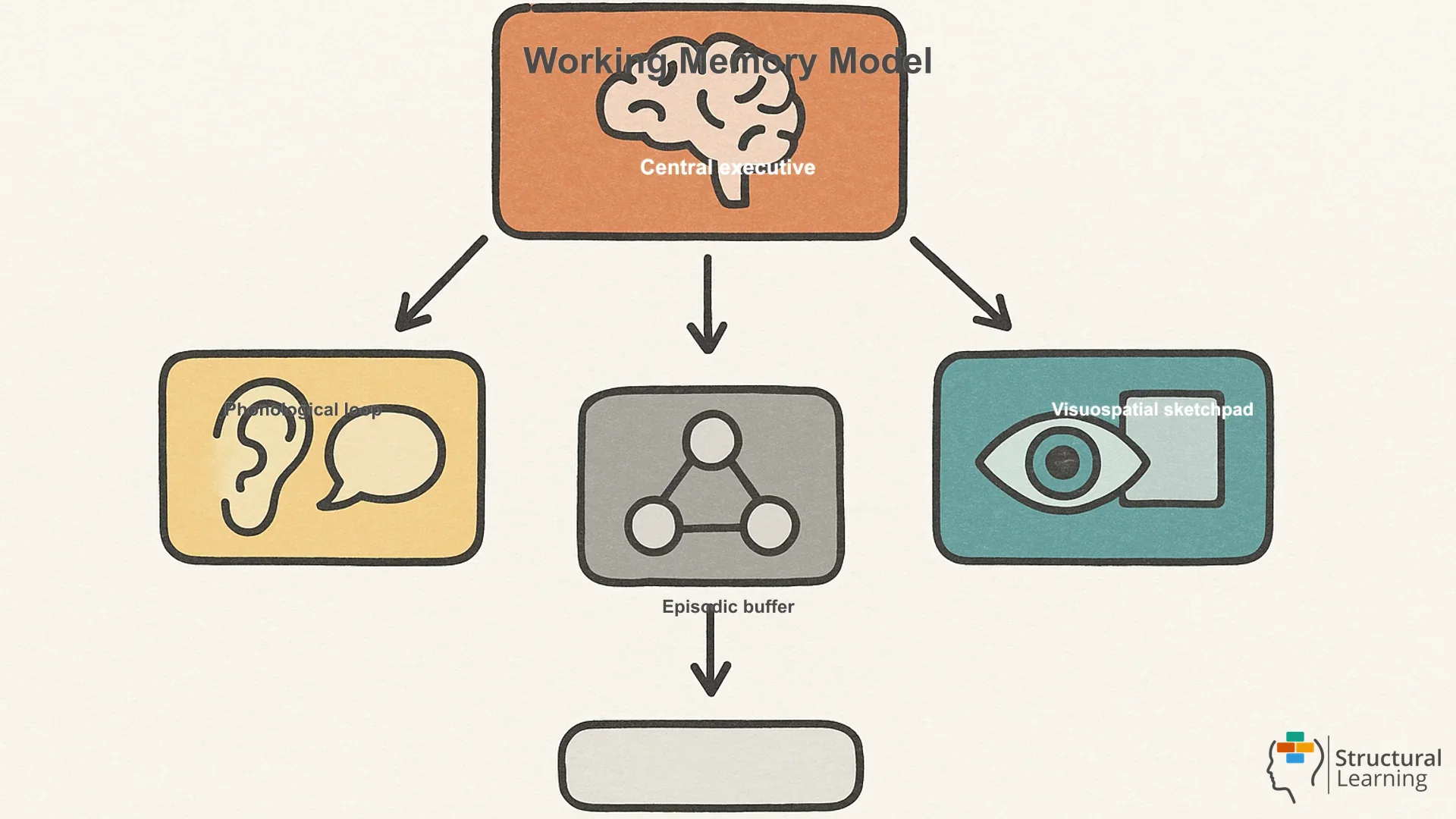

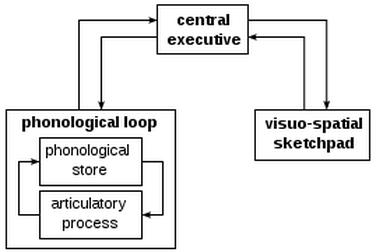

Baddeley's original model of the working memory was a multicomponent model consisting of three elements:

Brain imaging studies and research involving patients with brain damage led to the addition of a fourth component:

Brain research has supported the use of a multicomponent model of the working memory by identifying four distinct areas in the brain that are associated with each component. The prefrontal cortex is home to the central executive, the phonological loop is found in the left temporal lobes, the visuospatial sketchpad occupies the right parietal cortex, and the episodic buffer is in the parietal cortex.

It is exciting to see physical evidence for a theoretical model that was originally created by observing memory performance on simple memory tasks. The working memory is a gateway to the long-term memory. It is fascinating to study because it lends itself so well to practical interpretations that can make real differences to long-term learning and memory capacity.

I have described each part of the multicomponent model in more detail below.

The phonological loop is used to encode speech sounds and ‘hears’ your inner voice when you read text. It is used to complete verbal tasks, for language processing, and language comprehension. In the classroom, the phonological loop that is likely to be used most often. It is needed to read text, listen to the teacher and give verbal responses.

It can be used to transfer information to the long-term memory through subvocal rehearsal, repetition using our inner voice.

The visuospatial sketchpad encodes visual information, such as colour, images and location. Our visuospatial memory is part of the elaborative rehearsal process that transfers information to our long-term memory. For students, this happens when they:

The central executive is used to complete cognitive tasks by monitoring and coordinating the other components in the working memory. It is used for decision-making and to determine where we should direct our attention. When students appear to have selective attention, it may that the central executive is trying to control too many cognitive processes at one time.

The final addition to the working memory model, the episodic buffer, may be the most important and complex part of the model. It creates and retrieves memories of experiences and acts as an intermediatory stage between the short-term memory and the long-term memory. The episodic buffer is thought to control processes using a multidimensional code, which is how it is able to integrate information from different components of the working memory as well as the long-term memory.

Working memory has two critical limitations: capacity (typically 5-9 items) and duration (15-30 seconds without rehearsal). These limitations mean multi-step instructions often fail because students forget earlier steps while processing later ones. Additionally, working memory capacity varies significantly between students, with some holding only 3-4 items compared to others managing 8-9.

Baddeley's working memory model improves our understanding of how information is processed in the short-term memory and transferred to the long-term memory. Research supports the existence of distinct components and has also been used to demonstrate the limitations of our working memory. All of the separate stores have limited capacities; when one store becomes overloaded with information, performance on memory tasks drops significantly and transfer to the long-term memory becomes much harder.

Imagine how it feels to read a passage of text when someone is talking to you. Your attention is divided and you can't focus on either one as much as you want to because your phonological loop is overloaded. As teachers, we must consider the demands being placed on students' working memory when they are in our lessons to ensure effective and long-term learning can take place.

To improve your ability to recall information, try rehearsing it out loud. Doing so forces you to repeat the information over and over again, helping you memorize it.

Another way to improve your ability to remember information is to use spaced repetition software. Spaced repetition software automatically tests your knowledge periodically and provides feedback on whether you're retaining the information correctly.

Spaced repetition software can be used to study vocabulary words, math formulas, or any type of content. To use it effectively, simply input the information you wish to review and let the software test you periodically.

If you find yourself struggling to remember something, try reviewing it later. Reviewing information after a delay makes it easier to remember.

Writing down information also gives you a visual cue to remind you of the information. So next time you forget something, take notes instead of trying to remember it.

Cognitive load theory explains how working memory limitations affect learning by categorising mental effort into intrinsic (task difficulty), extraneous (poor instruction design), and germane (building schemas) loads. When total cognitive load exceeds working memory capacity, learning stops completely. Teachers can improve learning by reducing extraneous load through clear instructions and breaking complex tasks into smaller chunks.

Cognitive Load Theory has influenced my teaching more than any other area of psychology or CPD activity. It is concerned with maximising the efficiency of the working memory and consequently improving learning.

Although each component of the working memory has a limited capacity, the overall capacity of the working memory can be increased when two or more of the components are used simultaneously ( dual coding). Information will be encoded into the long-term memory more effectively if it is processed by more than one store. This can be achieved by:

Most importantly, Cognitive Load Theory emphasises the need to reduce all unnecessary pressure on the working memory and avoid the cognitive overload of any one store. At all times during a lesson, we should consider what we want our students to be attending to, and ensure that we are not distracting them with any redundant or distracting information at the same time.

Something every teacher has been guilty of is talking when there is text on the board; these both require the attention of the phonological loop and neither will get the attention it deserves. We can avoid this problem by only talking when the board is blank or displaying images and remaining silent when there is text on the board or students are reading or writing.

Teachers should chunk information into groups of 3-4 items, provide visual supports alongside verbal instructions, and build in processing time every 15-20 minutes. Effective strategies include using step-by-step visual guides, teaching one concept thoroughly before adding complexity, and providing worked examples. Regular checks for understanding help identify when students' working memory is overloaded before they fall behind.

Students, teachers and families can use Cognitive Load Theory to create environments where learning and revision can occur more effectively. Keep in mind the features and limitations of the working memory, try to use two stores simultaneously and only ever use each store for one task at a time.

When teaching:

Teaching students about working memory helps them recognise when they're cognitively overloaded and develop personal strategies like note-taking or asking for repetition. Students who understand their memory limitations become more effective learners by breaking tasks down independently and seeking help before frustration sets in. This metacognitive awarenesstransforms struggling students into strategic learners who actively manage their cognitive resources.

The working memory and Cognitive Load Theory are accessible concepts for students to understand. It is easy to demonstrate what happens when you overload the phonological loop: ask students to read a passage of writing while they repeat the word 'the' out loud. Students enjoy learning about the working memory because it explains some of the difficulties they experience during lessons and provides concrete ways in which they can improve learning.

The following advice is for students to maximise the efficiency of their working memory.

When learning:

Working memory is the bottleneck of learning, limiting students to processing 5-9 items for just 15-30 seconds, making instructional design crucial for student success. Teachers must recognise that what appears as inattention or laziness often indicates working memory overload, requiring modified instruction rather than repetition. Understanding and accommodating working memory limitations transforms teaching from information delivery to strategic cognitive management.

Having an awareness of how our memory works and knowing the limits of our working memory can help students and teachers to make small changes to the way they work to significantly improve learning. Throughout each lesson ask yourself 'what do I want my students to be thinking about now?' and 'what part of their working memory are they going to be using?'. Answering these questions will make it clear whether you need to do anything differently to allow their working memory to effectively complete the task you need it to be doing.

Context about the author: Zoe Benjamin is a secondary school teacher with a background and degree in Mathematics and Psychology. Having previously been Head of Mathematics and teacher of Psychology and Physics, I am now responsible for the quality of teaching and learning across all subjects and teachers' professional development. I have found cognitive psychology and education research to be invaluable in my current role.

If you would like to introduce your students to cognitive load theory, you are welcome to show them this short video that I produced for our students and teachers. Connect with Zoe @HeathfieldLearn or learning@heathfieldschool.net

These practical working memory strategies help teachers reduce cognitive load and support all learners, particularly those with limited working memory capacity. Implementing these techniques improves learning by aligning instruction with how memory actually works.

Working memory capacity is relatively fixed, but teachers can dramatically improve learning by reducing unnecessary cognitive load and improving how information is presented. These evidence-based working memory interventions benefit all students, with particularly significant impact for those with working memory difficulties including students with ADHD, dyslexia, and developmental language disorder.

These practical steps help teachers design lessons that respect working memory limitations and maximise learning retention across all key stages.

During a Year 7 geography lesson on river processes, Mrs Johnson introduces erosion by showing one image, explaining one process, then asking pupils to draw and label it before moving to transportation. She notices three pupils looking confused, so immediately provides a visual diagram and reduces the task to just labelling, recognising their working memory has reached capacity.

Working memory is the ability to hold information in mind and manipulate it simultaneously, lasting 15-30 seconds with a capacity of 5-9 chunks of information. Unlike sensory memory (1-2 seconds) or long-term memory (permanent storage), working memory acts as the critical gateway that allows us to process and manipulate information whilst learning. Ly the brain's workspace where we actively engage with new information before it either disappears or moves to long-term storage.

Working memory overload often appears as inattention, but it's actually cognitive overwhelm where pupils seem unable to follow instructions or complete tasks. Students may struggle to retain information long enough to finish assignments, become easily overwhelmed by the amount of material, or fail to understand concepts well enough to apply them. Teachers should look for patterns where pupils appear distracted or confused, particularly when given multi-step directions or complex tasks.

Multi-step instructions exceed the 7-item capacity limit of working memory, causing pupils to forget earlier steps whilst processing later ones. This creates a bottleneck effect where even capable students struggle to follow through with tasks successfully. Teachers should break complex instructions into smaller chunks, provide written reminders, or teach one step at a time to avoid overwhelming pupils' working memory capacity.

Chunking involves breaking information into smaller, manageable pieces that fit within working memory's 30-second time limit and 5-9 item capacity. Teachers can implement this by presenting information in small segments, using visual organisers to group related concepts, and ensuring pupils master one chunk before introducing the next. This prevents cognitive overload and allows information to be processed more effectively for long-term retention.

Drill practice can overwhelm struggling students' already limited working memory capacity, leading to frustration rather than learning. Cognitive psychology suggests using elaborative rehearsal and meaningful processing instead of simple repetition, connecting new information to existing knowledge. Teachers should focus on encoding strategies like elaboration, organisation, and visual imagery that help transform information into durable long-term memories.

Teachers need to use deliberate encoding strategies such as elaboration, organisation, and visual imagery rather than relying on simple repetition. This involves connecting new information to students' existing knowledge, using meaningful contexts, and providing multiple ways to process the same information. Activities should promote deep encoding by encouraging students to actively manipulate and relate information rather than just memorise it superficially.

Teachers should limit lessons to working memory's 30-second processing window by presenting information in small chunks and avoiding cognitive overload. They can provide written instructions alongside verbal ones, use visual aids to support processing, and build in regular pauses for consolidation. Additionally, connecting new learning to pupils' existing knowledge helps activate long-term memory and creates stronger neural pathways for future retrieval.

These peer-reviewed studies provide deeper insights into working memory: a teacher's guide and its application in educational settings.

The Cambridge Handbook of Working Memory and Language 19 citations

Schwieter et al. (2022)

This comprehensive handbook examines how working memory functions in both first and second language learning, processing difficulties, and training interventions. It provides teachers with re search-based insights into how working memory limitations can affect students' language development and offers evidence-based strategies for supporting multilingual learners in the classroom.

Is Cognitive Training Effective for Improving Executive Functions in Preschoolers? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis 132 citations

Scionti et al. (2020)

This meta-analysis reviews 32 studies examining whether cognitive training programs can improve executive functions in preschool children aged 3-6 years. The findings help teachers understand the effectiveness of working memory and executive function interventions for young learners, providing guidance on evidence-based approaches to support cognitive development in early childhood education.

Research on working memory and classroom attention 25 citations (Author, Year) examines how cognitive processes mediate inattentive behaviours in boys with ADHD during classroom instruction, providing insights into the underlying mechanisms that affect academic engagement and learning outcomes.

Orban et al. (2017)

This study investigates how working memory deficits contribute to inattentive behaviours in boys with ADHD during classroom instruction. It helps teachers understand the connection between working memory challenges and attention problems, offering insights into why some students struggle to stay focused during lessons and how to better support them.

Following instructions in a virtual school: Does working memory play a role? 87 citations

Jaroslawska et al. (2015)

This research examines how working memory affects students' ability to follow multi-step instructions in realistic virtual classroom environments. The study provides teachers with valuable insights into why some students struggle with complex directions and offers evidence-based understanding of how working memory limitations impact everyday classroom tasks.

Research on working memory and hippocampal function 103 citations (Author, Year) explores the intricate relationship between these two critical components of human cognition, examining how the hippocampus supports working memory processes and contributes to temporary information storage and manipulation.

Baddeley et al. (2011)

This paper explores the relationship between working memory and the hippocampus, examining how these brain systems work together to support learning and memory. It provides teachers with foundational knowledge about the neurological basis of working memory, helping them understand the biological mechanisms underlying students' learning processes.

Working memory (AI tools that respect working memory limitations) is one of the eight executive functions considered necessary for cognitive processes and is central to understanding the psychology of learning. Working memory is the ability to hold information in mind and manipulate it at the same time.

Working memory is important because it helps us process information Working memory is the brain's short-term memory. It helps us remember things we're learning . Working memory is important because it allows us to process information quickly and efficiently.

When we learn something new, our brains store it temporarily in our working memory. We use this temporary storage to keep track of the information until we've learned it well enough to retain it permanently in long-term memory.

Moving information from working memory into long-term storage requires deliberate encoding strategies. Research on encoding strategies for long-term learning identifies techniques such as elaboration, organisation, and visual imagery that help transform fleeting thoughts into durable memories. Teachers who understand these processes can design activities that promote deep encoding rather than superficial processing.

Executive functions, such as working memory, play a crucial role in our ability to learn and process information. They are responsible for our ability to plan, organise, and carry out tasks. Working memory, in particular, allows us to hold information in our minds while we work on other tasks.

It is also important for decision-making, problem-solving, and critical thinking. By improving our executive functions, we can enhance our cognitive abilities and improve our overall performance in work and daily life.

This means that when we learn something new, we need to be able to hold onto the information in our working memory for a period of time. This is where the concept of rehearsal We rehearse information over and over again until we've memorized it. The more times we practice, the better we become at remembering it.

When working memory is strong, we're able to pay attention to multiple things at once, remember where we left off when reading, and keep track of our thoughts and feelings. Students who struggle with working memory often find themselves overwhelmed by the amount of material they need to learn, especially in the early years of school.

They may be unable to retain information long enough to complete assignments, and they may not understand concepts well enough to apply them to real-life situations.

This article will provide you with a teachers' perspective about how the findings from cognitive psychology and Baddeley's working memory model can be applied to classroom practices . Small changes to the way we teach can enable us to get the most out of our students' working memory and achieve long-term learning.

The main types of memory include sensory memory (1-2 seconds), working memory (15-30 seconds), and long-term memory (potentially permanent storage). Working memory acts as the critical gateway between sensory input and long-term storage, allowing us to manipulate information while learning. Teachers need to understand these distinctions to design lessons that effectively move information through each memory stage.

According to the multi-store model of memory, we have three types of memory that are defined by the differences in their duration and capacity:

Our sensory memory processes everything in our environment. There is too much information for us to have conscious awareness of it and it can only remain in our sensory memory for less than a second. We are constantly bombarded with information from our senses; our sensory memory works hard to filter that information and determine if enough for our attention and to be granted access to our short-term memory.

Once information has been deemed important enough to enter our short-term memory, executive processes take over to help us retain and manipulate that information. These processes include attention, rehearsal, and organisation.

Attention allows us to focus on the information we need to remember, while rehearsal helps us repeat the information to ourselves to strengthen its retention.

organisation involves categorising and grouping information to make it easier to remember and recall later on. Without these executive processes, our working memory would not be able to function effectively.

When we actively pay attention to information, it enters our short-term memory where it can stay for up to 30 seconds without too much effort. There are individual differences in the capacity of our short-term memory but most people can retain between 5 and 9 chunks of information at any given time (you may have seen this referred to as '7 plus or minus 2'). Information will leave our short-term memory quickly if it is not processed in some way.

We will see later that repeating information using our inner voice (subvocal rehearsal) or processing the information in a meaningful way (elaborative rehearsal) are two of the cognitive processes required to move information into our long-term memory.

In addition to our general short-term memory capacity, we also have a specialised form of short-term memory called visual short-term memory. This type of memory allows us to hold onto visual information, like images or shapes, for a brief period of time. Studies have shown that visual short-term memory capacity is limited to around 3-4 visual items at a time. This is why we may struggle to remember a long string of numbers or a complex image unless we have a way to process and encode that information into our long-term memory.

If we want to keep information for longer than 30 seconds, we must move it into our long-term memory. This is where information is filed, ready for us to retrieve when we need it. New information is linked with previous learning from related topics to help us retrieve it more effectively in the future. There seems to be no limit to the capacity or duration of our long-term memory. However, having a limitless amount of information means that it can be difficult or sometimes impossible to retrieve a precise piece of information when it is needed.

When learning, activate long-term memory in order to retain information for a longer period of time. This can be done by connecting new information to existing knowledge or experiences, or by repeating the information multiple times in order to strengthen the neural connections in the brain. By actively engaging with the material and making associations with what you already know, you can help transfer the information from short-term memory to activated long-term memory, improving your ability to recall it later on.

If you have read any of my previous articles, you will know that I like to define learning as a permanent addition to the long-term memory that can be readily available when it is needed.

Learning is a two-stage process:

For information to enter the long-term memory, it must be processed by the short-term memory. In the multi-store model of memory, the short-term memory represents a store of information; it does not consider the structure or the cognitive processes required to transfer information into the long-term memory. Baddeley developed the working memory model to address this issue and it is now considered to be an essential component to cognitive development.

| Component | Function | Capacity | Classroom Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Central Executive | Controls attention, coordinates subsystems, manages cognitive processing | Limited attentional resources | Reduce distractions; avoid split attention; sequence tasks rather than multitask |

| Phonological Loop | Processes verbal and acoustic information through inner speech rehearsal | ~2 seconds of speech; ~7 items | Use chunking for verbal instructions; allow rehearsal time; minimise irrelevant speech |

| Visuospatial Sketchpad | Processes visual and spatial information; mental imagery | ~3-4 visual objects | Support verbal with visual; use diagrams and models; reduce visual clutter |

| Episodic Buffer | Integrates information across subsystems and connects to long-term memory | ~4 integrated chunks | Activate prior knowledge; make connections explicit; use stories and narratives |

Based on Baddeley & Hitch's Working Memory Model (1974, updated 2000). Understanding these components helps teachers design instruction that works with, rather than against, cognitive limitations.

Baddeley's original model of the working memory was a multicomponent model consisting of three elements:

Brain imaging studies and research involving patients with brain damage led to the addition of a fourth component:

Brain research has supported the use of a multicomponent model of the working memory by identifying four distinct areas in the brain that are associated with each component. The prefrontal cortex is home to the central executive, the phonological loop is found in the left temporal lobes, the visuospatial sketchpad occupies the right parietal cortex, and the episodic buffer is in the parietal cortex.

It is exciting to see physical evidence for a theoretical model that was originally created by observing memory performance on simple memory tasks. The working memory is a gateway to the long-term memory. It is fascinating to study because it lends itself so well to practical interpretations that can make real differences to long-term learning and memory capacity.

I have described each part of the multicomponent model in more detail below.

The phonological loop is used to encode speech sounds and ‘hears’ your inner voice when you read text. It is used to complete verbal tasks, for language processing, and language comprehension. In the classroom, the phonological loop that is likely to be used most often. It is needed to read text, listen to the teacher and give verbal responses.

It can be used to transfer information to the long-term memory through subvocal rehearsal, repetition using our inner voice.

The visuospatial sketchpad encodes visual information, such as colour, images and location. Our visuospatial memory is part of the elaborative rehearsal process that transfers information to our long-term memory. For students, this happens when they:

The central executive is used to complete cognitive tasks by monitoring and coordinating the other components in the working memory. It is used for decision-making and to determine where we should direct our attention. When students appear to have selective attention, it may that the central executive is trying to control too many cognitive processes at one time.

The final addition to the working memory model, the episodic buffer, may be the most important and complex part of the model. It creates and retrieves memories of experiences and acts as an intermediatory stage between the short-term memory and the long-term memory. The episodic buffer is thought to control processes using a multidimensional code, which is how it is able to integrate information from different components of the working memory as well as the long-term memory.

Working memory has two critical limitations: capacity (typically 5-9 items) and duration (15-30 seconds without rehearsal). These limitations mean multi-step instructions often fail because students forget earlier steps while processing later ones. Additionally, working memory capacity varies significantly between students, with some holding only 3-4 items compared to others managing 8-9.

Baddeley's working memory model improves our understanding of how information is processed in the short-term memory and transferred to the long-term memory. Research supports the existence of distinct components and has also been used to demonstrate the limitations of our working memory. All of the separate stores have limited capacities; when one store becomes overloaded with information, performance on memory tasks drops significantly and transfer to the long-term memory becomes much harder.

Imagine how it feels to read a passage of text when someone is talking to you. Your attention is divided and you can't focus on either one as much as you want to because your phonological loop is overloaded. As teachers, we must consider the demands being placed on students' working memory when they are in our lessons to ensure effective and long-term learning can take place.

To improve your ability to recall information, try rehearsing it out loud. Doing so forces you to repeat the information over and over again, helping you memorize it.

Another way to improve your ability to remember information is to use spaced repetition software. Spaced repetition software automatically tests your knowledge periodically and provides feedback on whether you're retaining the information correctly.

Spaced repetition software can be used to study vocabulary words, math formulas, or any type of content. To use it effectively, simply input the information you wish to review and let the software test you periodically.

If you find yourself struggling to remember something, try reviewing it later. Reviewing information after a delay makes it easier to remember.

Writing down information also gives you a visual cue to remind you of the information. So next time you forget something, take notes instead of trying to remember it.

Cognitive load theory explains how working memory limitations affect learning by categorising mental effort into intrinsic (task difficulty), extraneous (poor instruction design), and germane (building schemas) loads. When total cognitive load exceeds working memory capacity, learning stops completely. Teachers can improve learning by reducing extraneous load through clear instructions and breaking complex tasks into smaller chunks.

Cognitive Load Theory has influenced my teaching more than any other area of psychology or CPD activity. It is concerned with maximising the efficiency of the working memory and consequently improving learning.

Although each component of the working memory has a limited capacity, the overall capacity of the working memory can be increased when two or more of the components are used simultaneously ( dual coding). Information will be encoded into the long-term memory more effectively if it is processed by more than one store. This can be achieved by:

Most importantly, Cognitive Load Theory emphasises the need to reduce all unnecessary pressure on the working memory and avoid the cognitive overload of any one store. At all times during a lesson, we should consider what we want our students to be attending to, and ensure that we are not distracting them with any redundant or distracting information at the same time.

Something every teacher has been guilty of is talking when there is text on the board; these both require the attention of the phonological loop and neither will get the attention it deserves. We can avoid this problem by only talking when the board is blank or displaying images and remaining silent when there is text on the board or students are reading or writing.

Teachers should chunk information into groups of 3-4 items, provide visual supports alongside verbal instructions, and build in processing time every 15-20 minutes. Effective strategies include using step-by-step visual guides, teaching one concept thoroughly before adding complexity, and providing worked examples. Regular checks for understanding help identify when students' working memory is overloaded before they fall behind.

Students, teachers and families can use Cognitive Load Theory to create environments where learning and revision can occur more effectively. Keep in mind the features and limitations of the working memory, try to use two stores simultaneously and only ever use each store for one task at a time.

When teaching:

Teaching students about working memory helps them recognise when they're cognitively overloaded and develop personal strategies like note-taking or asking for repetition. Students who understand their memory limitations become more effective learners by breaking tasks down independently and seeking help before frustration sets in. This metacognitive awarenesstransforms struggling students into strategic learners who actively manage their cognitive resources.

The working memory and Cognitive Load Theory are accessible concepts for students to understand. It is easy to demonstrate what happens when you overload the phonological loop: ask students to read a passage of writing while they repeat the word 'the' out loud. Students enjoy learning about the working memory because it explains some of the difficulties they experience during lessons and provides concrete ways in which they can improve learning.

The following advice is for students to maximise the efficiency of their working memory.

When learning:

Working memory is the bottleneck of learning, limiting students to processing 5-9 items for just 15-30 seconds, making instructional design crucial for student success. Teachers must recognise that what appears as inattention or laziness often indicates working memory overload, requiring modified instruction rather than repetition. Understanding and accommodating working memory limitations transforms teaching from information delivery to strategic cognitive management.

Having an awareness of how our memory works and knowing the limits of our working memory can help students and teachers to make small changes to the way they work to significantly improve learning. Throughout each lesson ask yourself 'what do I want my students to be thinking about now?' and 'what part of their working memory are they going to be using?'. Answering these questions will make it clear whether you need to do anything differently to allow their working memory to effectively complete the task you need it to be doing.

Context about the author: Zoe Benjamin is a secondary school teacher with a background and degree in Mathematics and Psychology. Having previously been Head of Mathematics and teacher of Psychology and Physics, I am now responsible for the quality of teaching and learning across all subjects and teachers' professional development. I have found cognitive psychology and education research to be invaluable in my current role.

If you would like to introduce your students to cognitive load theory, you are welcome to show them this short video that I produced for our students and teachers. Connect with Zoe @HeathfieldLearn or learning@heathfieldschool.net

These practical working memory strategies help teachers reduce cognitive load and support all learners, particularly those with limited working memory capacity. Implementing these techniques improves learning by aligning instruction with how memory actually works.

Working memory capacity is relatively fixed, but teachers can dramatically improve learning by reducing unnecessary cognitive load and improving how information is presented. These evidence-based working memory interventions benefit all students, with particularly significant impact for those with working memory difficulties including students with ADHD, dyslexia, and developmental language disorder.

These practical steps help teachers design lessons that respect working memory limitations and maximise learning retention across all key stages.

During a Year 7 geography lesson on river processes, Mrs Johnson introduces erosion by showing one image, explaining one process, then asking pupils to draw and label it before moving to transportation. She notices three pupils looking confused, so immediately provides a visual diagram and reduces the task to just labelling, recognising their working memory has reached capacity.

Working memory is the ability to hold information in mind and manipulate it simultaneously, lasting 15-30 seconds with a capacity of 5-9 chunks of information. Unlike sensory memory (1-2 seconds) or long-term memory (permanent storage), working memory acts as the critical gateway that allows us to process and manipulate information whilst learning. Ly the brain's workspace where we actively engage with new information before it either disappears or moves to long-term storage.

Working memory overload often appears as inattention, but it's actually cognitive overwhelm where pupils seem unable to follow instructions or complete tasks. Students may struggle to retain information long enough to finish assignments, become easily overwhelmed by the amount of material, or fail to understand concepts well enough to apply them. Teachers should look for patterns where pupils appear distracted or confused, particularly when given multi-step directions or complex tasks.

Multi-step instructions exceed the 7-item capacity limit of working memory, causing pupils to forget earlier steps whilst processing later ones. This creates a bottleneck effect where even capable students struggle to follow through with tasks successfully. Teachers should break complex instructions into smaller chunks, provide written reminders, or teach one step at a time to avoid overwhelming pupils' working memory capacity.

Chunking involves breaking information into smaller, manageable pieces that fit within working memory's 30-second time limit and 5-9 item capacity. Teachers can implement this by presenting information in small segments, using visual organisers to group related concepts, and ensuring pupils master one chunk before introducing the next. This prevents cognitive overload and allows information to be processed more effectively for long-term retention.

Drill practice can overwhelm struggling students' already limited working memory capacity, leading to frustration rather than learning. Cognitive psychology suggests using elaborative rehearsal and meaningful processing instead of simple repetition, connecting new information to existing knowledge. Teachers should focus on encoding strategies like elaboration, organisation, and visual imagery that help transform information into durable long-term memories.

Teachers need to use deliberate encoding strategies such as elaboration, organisation, and visual imagery rather than relying on simple repetition. This involves connecting new information to students' existing knowledge, using meaningful contexts, and providing multiple ways to process the same information. Activities should promote deep encoding by encouraging students to actively manipulate and relate information rather than just memorise it superficially.

Teachers should limit lessons to working memory's 30-second processing window by presenting information in small chunks and avoiding cognitive overload. They can provide written instructions alongside verbal ones, use visual aids to support processing, and build in regular pauses for consolidation. Additionally, connecting new learning to pupils' existing knowledge helps activate long-term memory and creates stronger neural pathways for future retrieval.

These peer-reviewed studies provide deeper insights into working memory: a teacher's guide and its application in educational settings.

The Cambridge Handbook of Working Memory and Language 19 citations

Schwieter et al. (2022)

This comprehensive handbook examines how working memory functions in both first and second language learning, processing difficulties, and training interventions. It provides teachers with re search-based insights into how working memory limitations can affect students' language development and offers evidence-based strategies for supporting multilingual learners in the classroom.

Is Cognitive Training Effective for Improving Executive Functions in Preschoolers? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis 132 citations

Scionti et al. (2020)

This meta-analysis reviews 32 studies examining whether cognitive training programs can improve executive functions in preschool children aged 3-6 years. The findings help teachers understand the effectiveness of working memory and executive function interventions for young learners, providing guidance on evidence-based approaches to support cognitive development in early childhood education.

Research on working memory and classroom attention 25 citations (Author, Year) examines how cognitive processes mediate inattentive behaviours in boys with ADHD during classroom instruction, providing insights into the underlying mechanisms that affect academic engagement and learning outcomes.

Orban et al. (2017)

This study investigates how working memory deficits contribute to inattentive behaviours in boys with ADHD during classroom instruction. It helps teachers understand the connection between working memory challenges and attention problems, offering insights into why some students struggle to stay focused during lessons and how to better support them.

Following instructions in a virtual school: Does working memory play a role? 87 citations

Jaroslawska et al. (2015)

This research examines how working memory affects students' ability to follow multi-step instructions in realistic virtual classroom environments. The study provides teachers with valuable insights into why some students struggle with complex directions and offers evidence-based understanding of how working memory limitations impact everyday classroom tasks.

Research on working memory and hippocampal function 103 citations (Author, Year) explores the intricate relationship between these two critical components of human cognition, examining how the hippocampus supports working memory processes and contributes to temporary information storage and manipulation.

Baddeley et al. (2011)

This paper explores the relationship between working memory and the hippocampus, examining how these brain systems work together to support learning and memory. It provides teachers with foundational knowledge about the neurological basis of working memory, helping them understand the biological mechanisms underlying students' learning processes.

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/working-memory-a-teachers-guide#article","headline":"Working Memory: A teacher's guide","description":"What is working memory, and why should we consider it when planning and delivering classroom lessons?","datePublished":"2022-04-27T11:13:21.304Z","dateModified":"2026-01-26T10:09:32.212Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/working-memory-a-teachers-guide"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/6967d11630c2ec9eeebd9200_6967d11468b6ac7ae375c68a_working-memory-a-teachers-guide-diagram.webp","wordCount":3756},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/working-memory-a-teachers-guide#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"Working Memory: A teacher's guide","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/working-memory-a-teachers-guide"}]},{"@type":"FAQPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/working-memory-a-teachers-guide#faq","mainEntity":[{"@type":"Question","name":"What exactly is working memory and how does it differ from other types of memory?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Working memory is the ability to hold information in mind and manipulate it simultaneously, lasting 15-30 seconds with a capacity of 5-9 chunks of information. Unlike sensory memory (1-2 seconds) or long-term memory (permanent storage), working memory acts as the critical gateway that allows us to p"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"How can teachers recognise when pupils are experiencing working memory overload in the classroom?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Working memory overload often appears as inattention, but it's actually cognitive overwhelm where pupils seem unable to follow instructions or complete tasks. Students may struggle to retain information long enough to finish assignments, become easily overwhelmed by the amount of material, or fail t"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"Why do multi-step instructions cause problems for some pupils, and what should teachers do instead?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Multi-step instructions exceed the 7-item capacity limit of working memory, causing pupils to forget earlier steps whilst processing later ones. This creates a bottleneck effect where even capable students struggle to follow through with tasks successfully. Teachers should break complex instructions"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What does the article mean by 'chunking content effectively' and how can teachers implement this strategy?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Chunking involves breaking information into smaller, manageable pieces that fit within working memory's 30-second time limit and 5-9 item capacity. Teachers can implement this by presenting information in small segments, using visual organisers to group related concepts, and ensuring pupils master o"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"Why does traditional drill practice sometimes backfire for struggling students, and what does cognitive psychology suggest instead?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Drill practice can overwhelm struggling students' already limited working memory capacity, leading to frustration rather than learning. Cognitive psychology suggests using elaborative rehearsal and meaningful processing instead of simple repetition, connecting new information to existing knowledge. "}}]}]}