Cognitive Load Theory: A Parent's Guide to Supporting Learning

Explore how cognitive load impacts your child's learning and learn practical strategies to support their homework and study habits effectively.

Explore how cognitive load impacts your child's learning and learn practical strategies to support their homework and study habits effectively.

| Load Type | Definition | Home Example | Parent Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intrinsic | Complexity of the material | Learning multiplication tables | Break into smaller chunks |

| Extraneous | Unnecessary demands | Noisy homework environment | Create quiet study space |

| Germane | Effort toward understanding | Making connections to prior knowledge | Ask questions that prompt links |

| Total Load | Sum of all loads | Overwhelmed by homework | Balance difficulty and support |

| Working Memory | Limited processing capacity | Forgetting multi-step instructions | One step at a time |

Your child's brain processes new information through working memory, which can only hold 4-5 items at once before becoming overloaded. When information is properly learned, it moves to long-term memory where it's stored as organised mental frameworks that can be quickly retrieved. This explains why children understand concepts when taught slowly but struggle when too much is presented at once.

Cognitive Load Theory is research from educational psychology that explains why some ways of presenting information help learning while others hinder it. The core insight is simple: we can only think about a few new things at once.

Imagine your child's "thinking space" (what researchers call working memory) as a small desk with room for only four or five items. When we pile too much on at once, things fall off, and learning fails. But once information is truly learned, it gets stored in long-term memory as organised mental frameworks, which has unlimited space, and can be retrieved quickly without taking up much room on that small desk.

This explains why your child might understand something when explained slowly and clearly but become confused when too much is presented at once. It is not a lack of ability, it is a fundamental feature of how all human brains work.

Understanding cognitive load theory helps parents support learning effectively rather than accidentally making homework harder by overwhelming their child's working memory. This knowledge enables you to break down tasks appropriately and teach at a pace that matches your child's processing capacity. It also helps children develop better thinking strategies and metacognitive skills for approaching new tasks.

When helping your child with homework, you are essentially teaching. The same principles that make classroom teaching effective apply at the kitchen table. Understanding cognitive load helps you supp ort learning rather than accidentally making it harder. This awareness helps children develop better thinking strategiesand skills in thinking about learning for approaching new tasks.

If your child is learning long division, do not also correct their handwriting, discuss the real-world applications, and explain why the method works all at once. Focus on the procedure first. Once that is automatic, other elements can be added.

When your child is stuck on a problem, showing them how to solve a similar one is often more helpful than giving hints and waiting for them to figure it out. This is not "giving them the answer", it is showing them the method so they can apply it to the next problem.

Think about learning to tie shoelaces. No one expects a child to discover the method independently. We demonstrate, guide their hands, and guided practice together until the skill becomes automatic. Academic cognitive skillscan be taught the same way.

Before adding new information, make sure your child has understood and can apply what came before. A common mistake is moving too quickly through material, building on foundations that have not been established. Taking time to ensure solid understanding at each step saves time in the long run.

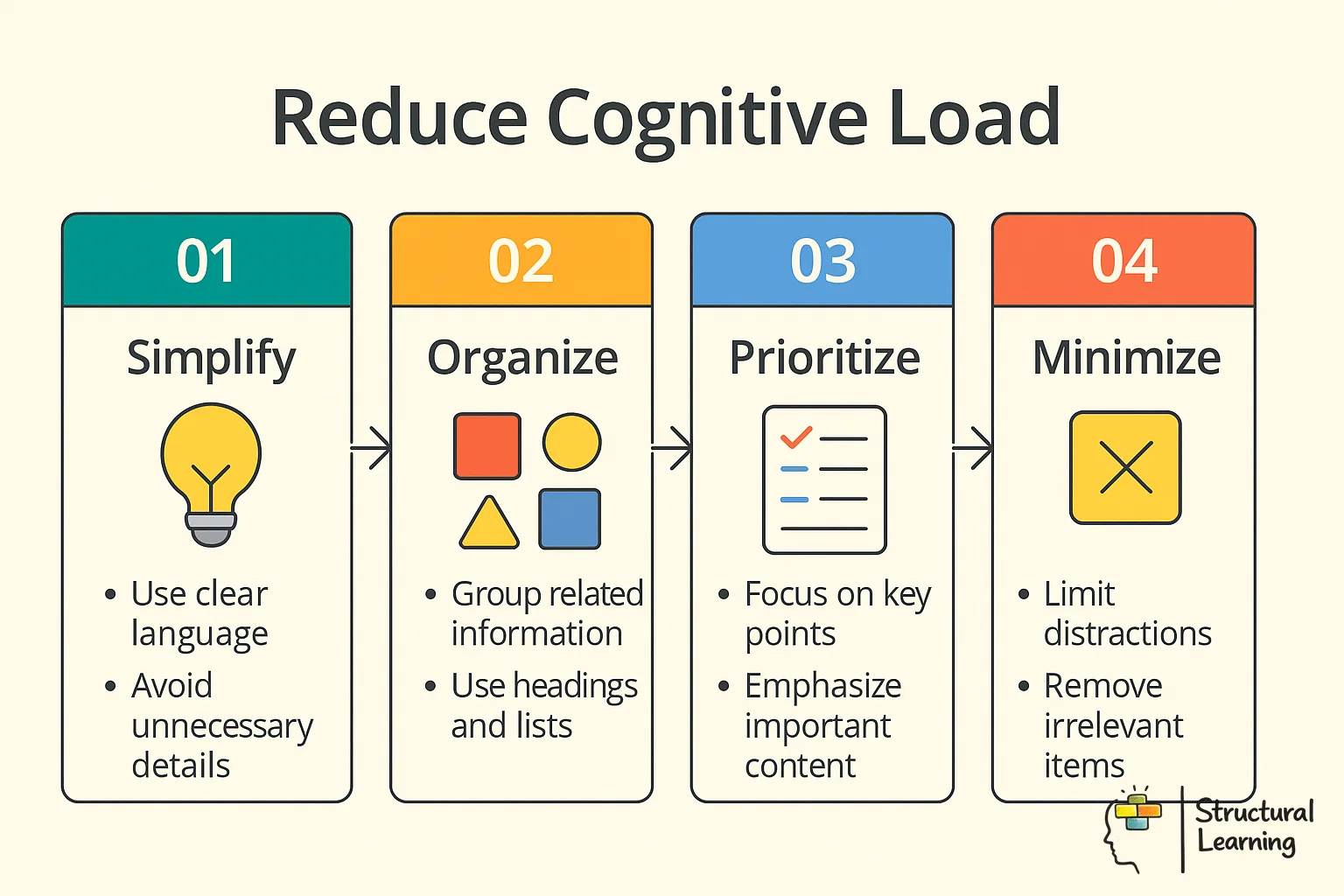

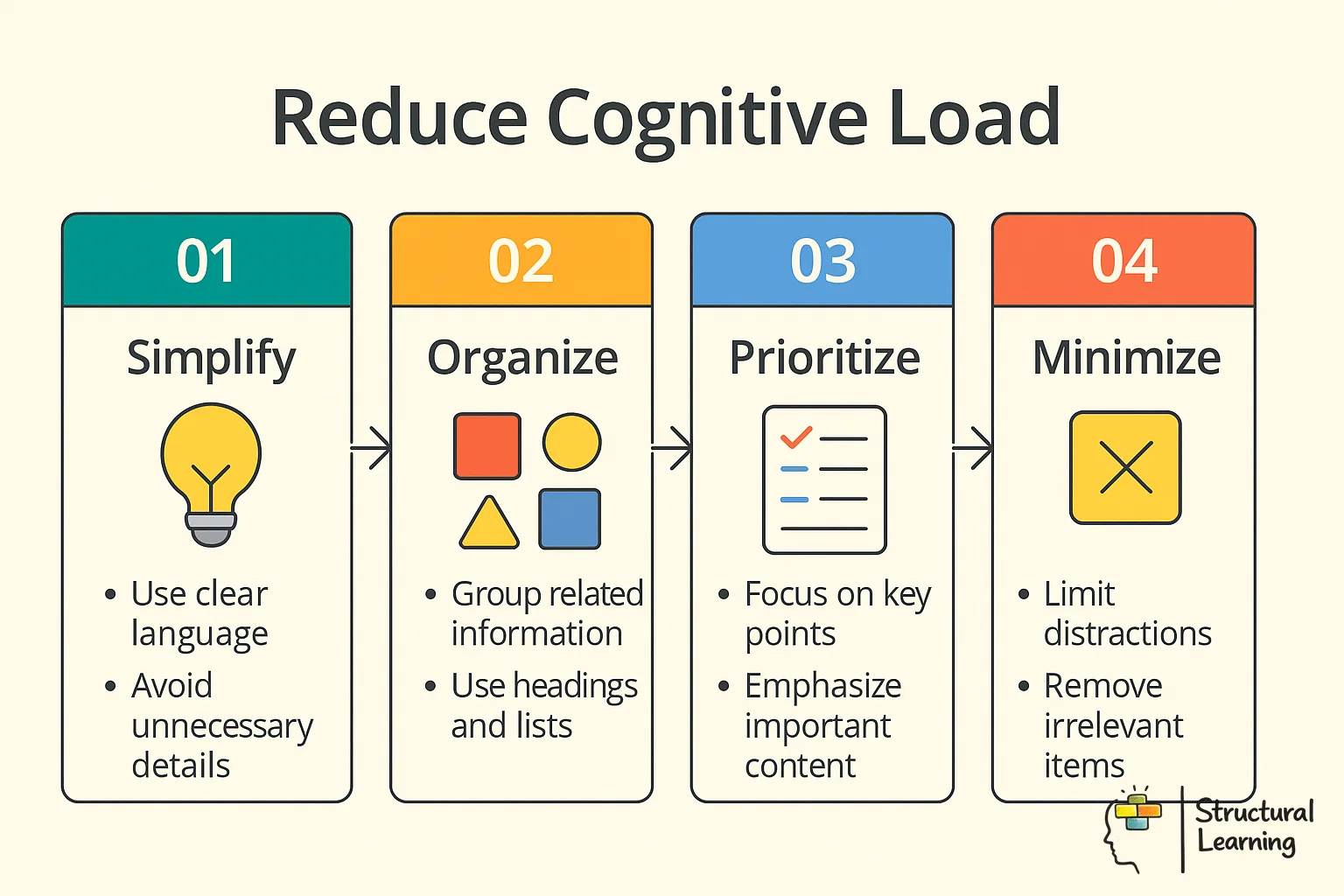

Parents can reduce cognitive load by breaking complex tasks into small steps, demonstrating solutions before asking children to solve independently, and connecting new concepts to existing knowledge. Use worked examples to show the process clearly, then gradually increase your child's independence as they master each step. Always explain one concept thoroughly before introducing the next.

| Instead of.. | Try this.. |

|---|---|

| Giving a long explanation with many steps | Break it into small chunks with checks for understanding between each |

| Asking "What do you think you should do?" | Model the first problem, then guide them through the second |

| Pointing at the textbook while explaining verbally | Explain while they look at the book, or use the book without talking over it |

| Moving on when they say "I get it" | Ask them to explain it back or try one independently |

| Introducing the hardest example first | Start with a simple example, then gradually increase difficulty |

Support reading by pre-teaching difficult vocabulary before your child encounters it in text and activating prior knowledge about the topic through discussion. Break longer texts into manageable chunks and pause to check understanding before continuing. Use visual aids or graphic organisers to help your child track main ideas without taxing their working memory.

Reading involves managing multiple sources of information simultaneously: decoding words, understanding vocabulary, following sentence structure, connecting to prior knowledge, and comprehending meaning. For developing readers, this can exceed cognitive capacity.

When reading with your child, reduce the load by pre-teaching difficult vocabulary, discussing what they already know about the topic, reading aloud to them so they can focus on comprehension rather than decoding, or taking turns (you read one page, they read the next).

This often signals cognitive overload, too much information presented too quickly. Try simplifying your explanation, using a concrete example, drawing a picture, or breaking the task into smaller steps. What feels like a simple explanation to you (who already understands) may be overwhelming to someone encountering the material for the first time.

Cognitive overload shows up in predictable ways that parents can learn to spot. Watch for signs like your child saying "I don't know" repeatedly, becoming unusually frustrated, or making mistakes on things they previously understood. These behaviours signal that their working memory is overwhelmed, not that they lack ability or effort.

Physical signs often accompany cognitive overload. Your child might rub their eyes, fidget more than usual, or complain of feeling tired even when well-rested. They may start making careless errors in work they normally complete accurately, such as forgetting to carry numbers in addition or skipping words whilst reading. These mistakes happen because all their mental capacity is being used to process new information, leaving none available for monitoring accuracy.

Emotional indicators are equally important. A child experiencing cognitive overload may become tearful, angry, or withdrawn. They might say things like "I'm stupid" or "I'll never get this." These responses stem from frustration at being unable to process information, not from actual inability. When you notice these signs, it's time to reduce the cognitive load by breaking tasks down further, taking a break, or approaching the material differently. Remember that pushing through when overloaded rarely leads to learning, it more often results in confusion becoming entrenched.

Practice transforms effortful thinking into automatic processes, freeing up working memory for new learning. When your child practises times tables until they become instant recall, they no longer use precious mental space calculating basic multiplication during more complex maths problems. This automaticity is crucial for building advanced skills.

Effective practice follows specific principles. Short, frequent sessions work better than long, occasional ones. Five minutes of times tables practice daily outperforms thirty minutes once a week. The practice should focus on accuracy first, then speed. Rushing leads to practising mistakes, which then become hard to unlearn. Start with easier examples until those are fluent, then gradually increase difficulty. For spelling practice, begin with simple words your child can almost spell correctly, not the most challenging words from their list.

The type of practice matters as much as the amount. Retrieval practice, actively recalling information rather than re-reading it, strengthens memory more effectively. Instead of looking over spelling words, have your child write them from memory. Rather than re-reading notes, ask them to explain what they learned without looking. This feels harder than passive review, but it builds stronger, more accessible memories. Mix up the order of practice questions too. Practising maths problems in a predictable pattern (all addition, then all subtraction) creates weaker learning than interleavingdifferent types.

Digital devices can either reduce or increase cognitive load, depending on how they're used. Educational apps that present information clearly and provide immediate feedback can support learning, whilst devices that distract with notifications, animations, or multiple tabs open simultaneously can overwhelm working memory and prevent effective learning.

When using technology for homework, establish clear boundaries. Close unnecessary browser tabs and silence notifications on all devices in the study area. If your child needs the internet for research, help them find relevant information first, then disconnect whilst they process and apply it. Many children (and adults) overestimate their ability to multitask. The brain doesn't actually multitask, it rapidly switches between tasks, using cognitive resources each time it switches.

Choose educational technology thoughtfully. Good educational software presents one concept at a time, provides worked examples, and offers practice with immediate feedback. Avoid programmes that prioritise entertainment over clear instruction, use distracting graphics or sounds, or present too many concepts simultaneously. When possible, preview new educational apps or websites yourself before your child uses them. This allows you to identify potential sources of unnecessary cognitive load and plan how to introduce the technology in a way that supports rather than hinders learning.

Create optimal learning conditions by minimising distractions in the study environment and ensuring your child has had adequate rest and nutrition. Schedule challenging homework when your child is most alert, typically earlier in the day, and build in regular breaks every 20-30 minutes. Keep learning sessions focused on one subject at a time to prevent cognitive overload from task-switching.

Cognitive load is affected by environment and state of mind. A quiet, uncluttered workspace helps. Anxiety and distraction consume working memory capacity that could otherwise be used for learning. Ensuring your child is rested, calm, and focused before tackling challenging work makes the learning itself easier.

Working memory limits affect everyone, regardless of intelligence. A bright child may be able to build complex understanding once information gets into long-term memory, but the bottleneck of working memory affects all learners equally. The solution is better presentation, not more effort.

Some productive struggle can be valuable, but struggling with poorly designed instruction or overwhelming complexity does not build character, it wastes time and causes frustration. If your child is stuck and getting nowhere, providing clear guidance helps them learn more effectively than continued confusion.

No. The goal is to help them develop understanding, not to produce completed homework. Demonstrating methods, guiding practice, and providing scaffolding are all legitimate support. Doing the work while they watch is not, that produces no learning at all.

Methods have changed in some subjects, particularly mathematics. Introducing a different method adds cognitive load (now they have two approaches to process). Unless you are confident you understand the school's method, it may be better to support your child in practising what they learned at school rather than teaching alternatives.

These peer-reviewed studies provide deeper insights into cognitive load theory: a parent's guide to supportinglearning and its application in educational settings.

Cognitive Theory of Multimedia Learning 1637 citations

Mayer et al. (2021)

This paper by Mayer presents the Cognitive Theory of Multimedia Learning, which explains how people learn from words and pictures together and identifies principles for effective multimedia instruction design. It's relevant to parents because it provides evidence-based guidelines for choosing and using educational materials that combine text, images, and audio to support their children's learning without overwhelming their cognitive capacity.

Research on multimedia instruction design principles785 citations (Author, Year) demonstrates how evidence-based learning science can be systematically applied to create more effective educational materials, providing educators with practical guidelines for improving student engagement and comprehension through strategic use of visual and auditory elements.

Mayer et al. (2008)

Mayer's work translates cognitive load research into practical principles for designing multimedia instruction, offering concrete guidelines for how to present information effectively using multiple formats like text, images, and narration. This is valuable for parents who want to understand how to select educational apps, videos, and digital learning materials that follow scientific principles to maximise their child's learning while minimising cognitive overload.

Element Interactivity and Intrinsic, Extraneous, and Germane Cognitive Load 1667 citations

Sweller et al. (2010)

Sweller's foundational paper explains the three types of cognitive load - intrinsic, extraneous, and germane - and how the complexity of learning material affects mental processing capacity. This work is essential for parents to understand because it provides the theoretical framework for why some learning activities overwhelm children while others promote effective learning, helping parents make better decisions about homework support and educational activities.

Understanding instructional design effects by differentiated measurement of intrinsic, extraneous, and germane cognitive load 149 citations

Klepsch et al. (2020)

This research by Klepsch and Seufert focuses on how to measure and differentiate between the three types of cognitive load to improve learning materials and instructional design. It's relevant for parents because it helps explain how educators and researchers identify when learning materials are too complex or poorly designed, giving parents insight into how to evaluate whether their child's educational experiences are appropriately challenging.

Klepsch et al. (2017)

Klepsch, Schmitz, and Seufert developed reliable tools to measure the different types of cognitive load that students experience during learning tasks. This research is important for parents because it validates methods for understanding when children are struggling due to poor material design versus appropriate learning challenge, helping parents better interpret their child's learning difficulties and successes.

| Load Type | Definition | Home Example | Parent Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intrinsic | Complexity of the material | Learning multiplication tables | Break into smaller chunks |

| Extraneous | Unnecessary demands | Noisy homework environment | Create quiet study space |

| Germane | Effort toward understanding | Making connections to prior knowledge | Ask questions that prompt links |

| Total Load | Sum of all loads | Overwhelmed by homework | Balance difficulty and support |

| Working Memory | Limited processing capacity | Forgetting multi-step instructions | One step at a time |

Your child's brain processes new information through working memory, which can only hold 4-5 items at once before becoming overloaded. When information is properly learned, it moves to long-term memory where it's stored as organised mental frameworks that can be quickly retrieved. This explains why children understand concepts when taught slowly but struggle when too much is presented at once.

Cognitive Load Theory is research from educational psychology that explains why some ways of presenting information help learning while others hinder it. The core insight is simple: we can only think about a few new things at once.

Imagine your child's "thinking space" (what researchers call working memory) as a small desk with room for only four or five items. When we pile too much on at once, things fall off, and learning fails. But once information is truly learned, it gets stored in long-term memory as organised mental frameworks, which has unlimited space, and can be retrieved quickly without taking up much room on that small desk.

This explains why your child might understand something when explained slowly and clearly but become confused when too much is presented at once. It is not a lack of ability, it is a fundamental feature of how all human brains work.

Understanding cognitive load theory helps parents support learning effectively rather than accidentally making homework harder by overwhelming their child's working memory. This knowledge enables you to break down tasks appropriately and teach at a pace that matches your child's processing capacity. It also helps children develop better thinking strategies and metacognitive skills for approaching new tasks.

When helping your child with homework, you are essentially teaching. The same principles that make classroom teaching effective apply at the kitchen table. Understanding cognitive load helps you supp ort learning rather than accidentally making it harder. This awareness helps children develop better thinking strategiesand skills in thinking about learning for approaching new tasks.

If your child is learning long division, do not also correct their handwriting, discuss the real-world applications, and explain why the method works all at once. Focus on the procedure first. Once that is automatic, other elements can be added.

When your child is stuck on a problem, showing them how to solve a similar one is often more helpful than giving hints and waiting for them to figure it out. This is not "giving them the answer", it is showing them the method so they can apply it to the next problem.

Think about learning to tie shoelaces. No one expects a child to discover the method independently. We demonstrate, guide their hands, and guided practice together until the skill becomes automatic. Academic cognitive skillscan be taught the same way.

Before adding new information, make sure your child has understood and can apply what came before. A common mistake is moving too quickly through material, building on foundations that have not been established. Taking time to ensure solid understanding at each step saves time in the long run.

Parents can reduce cognitive load by breaking complex tasks into small steps, demonstrating solutions before asking children to solve independently, and connecting new concepts to existing knowledge. Use worked examples to show the process clearly, then gradually increase your child's independence as they master each step. Always explain one concept thoroughly before introducing the next.

| Instead of.. | Try this.. |

|---|---|

| Giving a long explanation with many steps | Break it into small chunks with checks for understanding between each |

| Asking "What do you think you should do?" | Model the first problem, then guide them through the second |

| Pointing at the textbook while explaining verbally | Explain while they look at the book, or use the book without talking over it |

| Moving on when they say "I get it" | Ask them to explain it back or try one independently |

| Introducing the hardest example first | Start with a simple example, then gradually increase difficulty |

Support reading by pre-teaching difficult vocabulary before your child encounters it in text and activating prior knowledge about the topic through discussion. Break longer texts into manageable chunks and pause to check understanding before continuing. Use visual aids or graphic organisers to help your child track main ideas without taxing their working memory.

Reading involves managing multiple sources of information simultaneously: decoding words, understanding vocabulary, following sentence structure, connecting to prior knowledge, and comprehending meaning. For developing readers, this can exceed cognitive capacity.

When reading with your child, reduce the load by pre-teaching difficult vocabulary, discussing what they already know about the topic, reading aloud to them so they can focus on comprehension rather than decoding, or taking turns (you read one page, they read the next).

This often signals cognitive overload, too much information presented too quickly. Try simplifying your explanation, using a concrete example, drawing a picture, or breaking the task into smaller steps. What feels like a simple explanation to you (who already understands) may be overwhelming to someone encountering the material for the first time.

Cognitive overload shows up in predictable ways that parents can learn to spot. Watch for signs like your child saying "I don't know" repeatedly, becoming unusually frustrated, or making mistakes on things they previously understood. These behaviours signal that their working memory is overwhelmed, not that they lack ability or effort.

Physical signs often accompany cognitive overload. Your child might rub their eyes, fidget more than usual, or complain of feeling tired even when well-rested. They may start making careless errors in work they normally complete accurately, such as forgetting to carry numbers in addition or skipping words whilst reading. These mistakes happen because all their mental capacity is being used to process new information, leaving none available for monitoring accuracy.

Emotional indicators are equally important. A child experiencing cognitive overload may become tearful, angry, or withdrawn. They might say things like "I'm stupid" or "I'll never get this." These responses stem from frustration at being unable to process information, not from actual inability. When you notice these signs, it's time to reduce the cognitive load by breaking tasks down further, taking a break, or approaching the material differently. Remember that pushing through when overloaded rarely leads to learning, it more often results in confusion becoming entrenched.

Practice transforms effortful thinking into automatic processes, freeing up working memory for new learning. When your child practises times tables until they become instant recall, they no longer use precious mental space calculating basic multiplication during more complex maths problems. This automaticity is crucial for building advanced skills.

Effective practice follows specific principles. Short, frequent sessions work better than long, occasional ones. Five minutes of times tables practice daily outperforms thirty minutes once a week. The practice should focus on accuracy first, then speed. Rushing leads to practising mistakes, which then become hard to unlearn. Start with easier examples until those are fluent, then gradually increase difficulty. For spelling practice, begin with simple words your child can almost spell correctly, not the most challenging words from their list.

The type of practice matters as much as the amount. Retrieval practice, actively recalling information rather than re-reading it, strengthens memory more effectively. Instead of looking over spelling words, have your child write them from memory. Rather than re-reading notes, ask them to explain what they learned without looking. This feels harder than passive review, but it builds stronger, more accessible memories. Mix up the order of practice questions too. Practising maths problems in a predictable pattern (all addition, then all subtraction) creates weaker learning than interleavingdifferent types.

Digital devices can either reduce or increase cognitive load, depending on how they're used. Educational apps that present information clearly and provide immediate feedback can support learning, whilst devices that distract with notifications, animations, or multiple tabs open simultaneously can overwhelm working memory and prevent effective learning.

When using technology for homework, establish clear boundaries. Close unnecessary browser tabs and silence notifications on all devices in the study area. If your child needs the internet for research, help them find relevant information first, then disconnect whilst they process and apply it. Many children (and adults) overestimate their ability to multitask. The brain doesn't actually multitask, it rapidly switches between tasks, using cognitive resources each time it switches.

Choose educational technology thoughtfully. Good educational software presents one concept at a time, provides worked examples, and offers practice with immediate feedback. Avoid programmes that prioritise entertainment over clear instruction, use distracting graphics or sounds, or present too many concepts simultaneously. When possible, preview new educational apps or websites yourself before your child uses them. This allows you to identify potential sources of unnecessary cognitive load and plan how to introduce the technology in a way that supports rather than hinders learning.

Create optimal learning conditions by minimising distractions in the study environment and ensuring your child has had adequate rest and nutrition. Schedule challenging homework when your child is most alert, typically earlier in the day, and build in regular breaks every 20-30 minutes. Keep learning sessions focused on one subject at a time to prevent cognitive overload from task-switching.

Cognitive load is affected by environment and state of mind. A quiet, uncluttered workspace helps. Anxiety and distraction consume working memory capacity that could otherwise be used for learning. Ensuring your child is rested, calm, and focused before tackling challenging work makes the learning itself easier.

Working memory limits affect everyone, regardless of intelligence. A bright child may be able to build complex understanding once information gets into long-term memory, but the bottleneck of working memory affects all learners equally. The solution is better presentation, not more effort.

Some productive struggle can be valuable, but struggling with poorly designed instruction or overwhelming complexity does not build character, it wastes time and causes frustration. If your child is stuck and getting nowhere, providing clear guidance helps them learn more effectively than continued confusion.

No. The goal is to help them develop understanding, not to produce completed homework. Demonstrating methods, guiding practice, and providing scaffolding are all legitimate support. Doing the work while they watch is not, that produces no learning at all.

Methods have changed in some subjects, particularly mathematics. Introducing a different method adds cognitive load (now they have two approaches to process). Unless you are confident you understand the school's method, it may be better to support your child in practising what they learned at school rather than teaching alternatives.

These peer-reviewed studies provide deeper insights into cognitive load theory: a parent's guide to supportinglearning and its application in educational settings.

Cognitive Theory of Multimedia Learning 1637 citations

Mayer et al. (2021)

This paper by Mayer presents the Cognitive Theory of Multimedia Learning, which explains how people learn from words and pictures together and identifies principles for effective multimedia instruction design. It's relevant to parents because it provides evidence-based guidelines for choosing and using educational materials that combine text, images, and audio to support their children's learning without overwhelming their cognitive capacity.

Research on multimedia instruction design principles785 citations (Author, Year) demonstrates how evidence-based learning science can be systematically applied to create more effective educational materials, providing educators with practical guidelines for improving student engagement and comprehension through strategic use of visual and auditory elements.

Mayer et al. (2008)

Mayer's work translates cognitive load research into practical principles for designing multimedia instruction, offering concrete guidelines for how to present information effectively using multiple formats like text, images, and narration. This is valuable for parents who want to understand how to select educational apps, videos, and digital learning materials that follow scientific principles to maximise their child's learning while minimising cognitive overload.

Element Interactivity and Intrinsic, Extraneous, and Germane Cognitive Load 1667 citations

Sweller et al. (2010)

Sweller's foundational paper explains the three types of cognitive load - intrinsic, extraneous, and germane - and how the complexity of learning material affects mental processing capacity. This work is essential for parents to understand because it provides the theoretical framework for why some learning activities overwhelm children while others promote effective learning, helping parents make better decisions about homework support and educational activities.

Understanding instructional design effects by differentiated measurement of intrinsic, extraneous, and germane cognitive load 149 citations

Klepsch et al. (2020)

This research by Klepsch and Seufert focuses on how to measure and differentiate between the three types of cognitive load to improve learning materials and instructional design. It's relevant for parents because it helps explain how educators and researchers identify when learning materials are too complex or poorly designed, giving parents insight into how to evaluate whether their child's educational experiences are appropriately challenging.

Klepsch et al. (2017)

Klepsch, Schmitz, and Seufert developed reliable tools to measure the different types of cognitive load that students experience during learning tasks. This research is important for parents because it validates methods for understanding when children are struggling due to poor material design versus appropriate learning challenge, helping parents better interpret their child's learning difficulties and successes.

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/a-parents-guide-to-cognitive-load-theory#article","headline":"Cognitive Load Theory: A Parent's Guide to Supporting Learning","description":"Understand how cognitive load affects your child's learning and what you can do to help. This guide explains working memory limits, intrinsic and extraneous...","datePublished":"2021-10-12T11:05:08.962Z","dateModified":"2026-01-26T10:09:32.212Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/a-parents-guide-to-cognitive-load-theory"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/696a15ad6f3f9e4e8141564c_696a15ab1914e26b190d5527_a-parents-guide-to-cognitive-load-theory-infographic.webp","wordCount":1981},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/a-parents-guide-to-cognitive-load-theory#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"Cognitive Load Theory: A Parent's Guide to Supporting Learning","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/a-parents-guide-to-cognitive-load-theory"}]},{"@type":"FAQPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/a-parents-guide-to-cognitive-load-theory#faq","mainEntity":[{"@type":"Question","name":"My child is bright, why do they still get confused?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Working memory limits affect everyone, regardless of intelligence. A bright child may be able to build complex understanding once information gets into long-term memory, but the bottleneck of working memory affects all learners equally. The solution is better presentation, not more effort."}},{"@type":"Question","name":"Should I let them struggle before helping?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Some productive struggle can be valuable, but struggling with poorly designed instruction or overwhelming complexity does not build character, it wastes time and causes frustration. If your child is stuck and getting nowhere, providing clear guidance helps them learn more effectively than continued "}},{"@type":"Question","name":"Does this mean I should do their homework for them?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"No. The goal is to help them develop understanding, not to produce completed homework. Demonstrating methods, guiding practice, and providing"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What if school teaches things differently from how I learned?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Methods have changed in some subjects, particularly mathematics. Introducing a different method adds cognitive load (now they have two approaches to process). Unless you are confident you understand the school's method, it may be better to support your child in practising what they learned at school"}}]}]}