Gibbs' Reflective Cycle: 6 Stages with Worked Examples

Gibbs' six stages explained: description, feelings, evaluation, analysis, conclusion, action plan. Includes worked classroom examples for teachers.

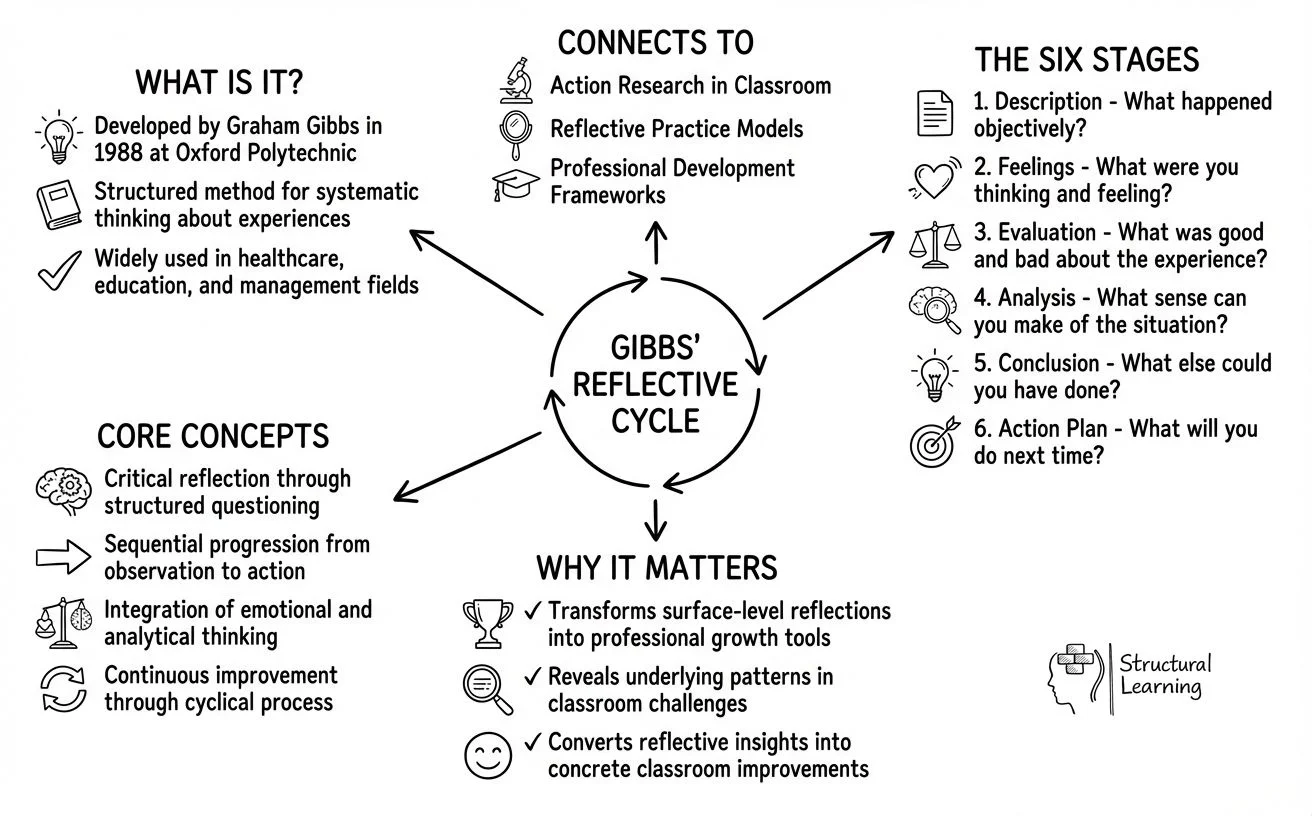

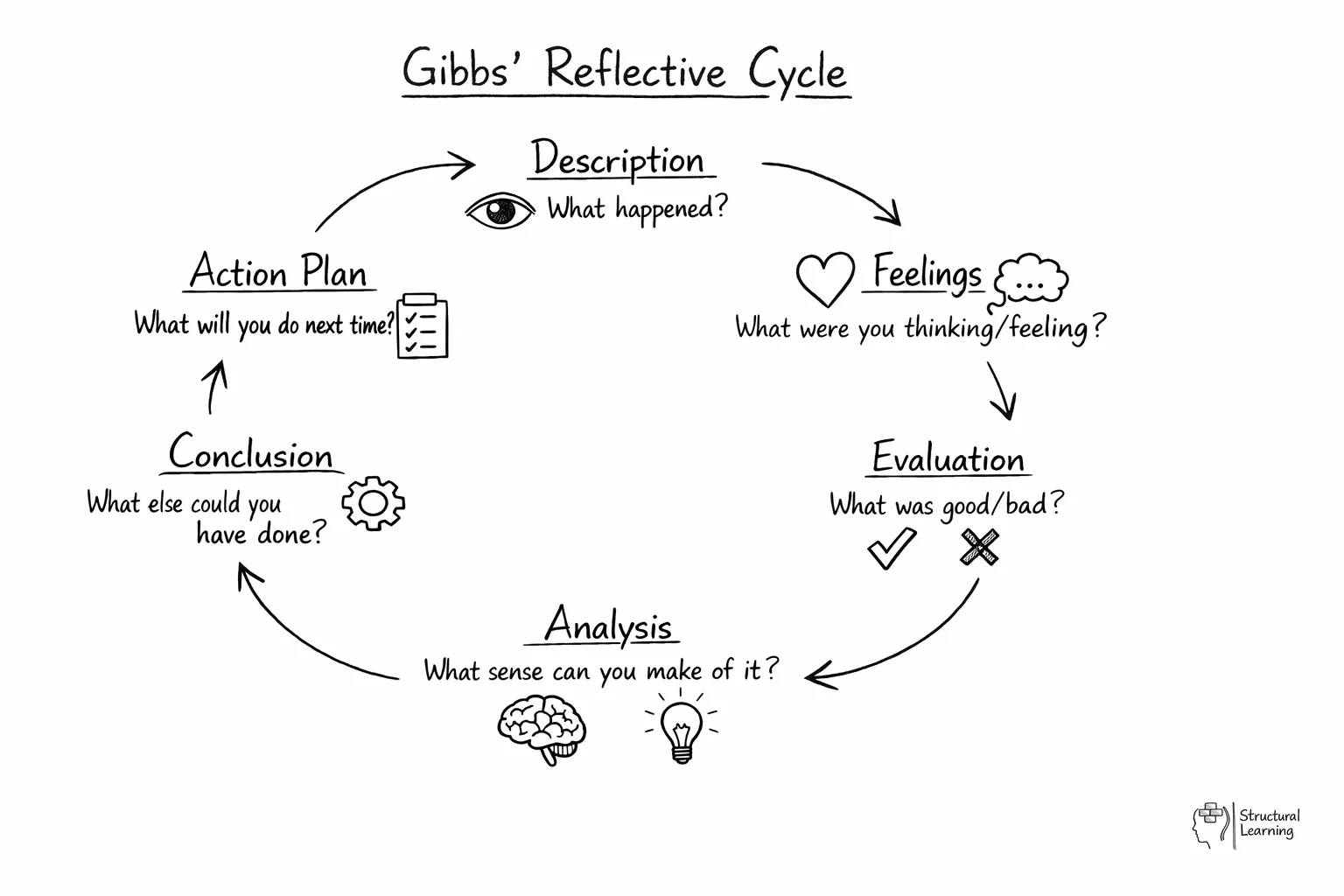

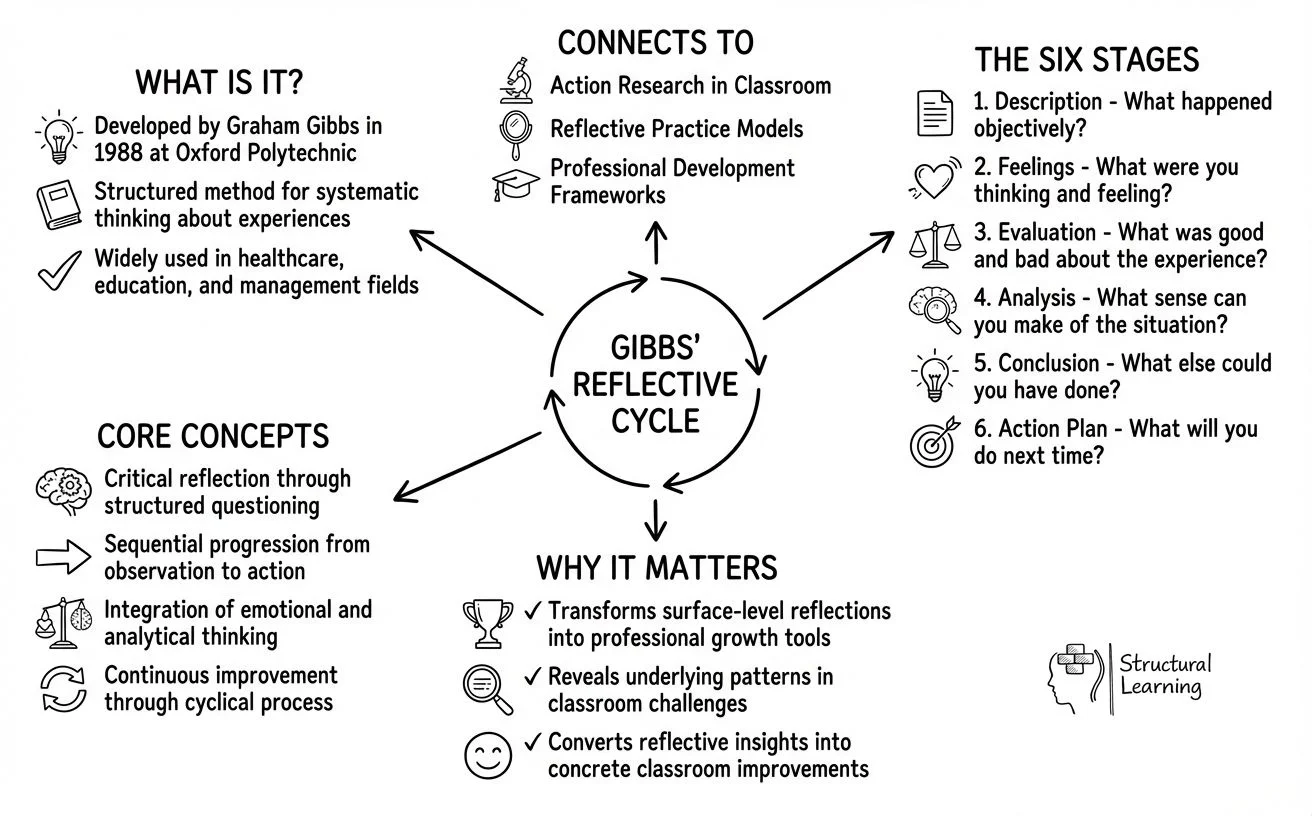

Gibbs' Reflective Cycle is a popular model for reflection, acting as a structured method to enable individuals to think systematically about the experiences they had during a specific situation.

Gibbs' Reflective Cycle is a widely used and accepted model of reflection. Developed by Graham Gibbs in 1988 at Oxford Polytechnic, now Oxford Brookes University, this reflective cycle framework is widely used within various fields such as healthcare, education, and management to improve professional and personal development. It has since become an integral part of reflective practise, allowing individuals to reflect on their experiences in a structured way.

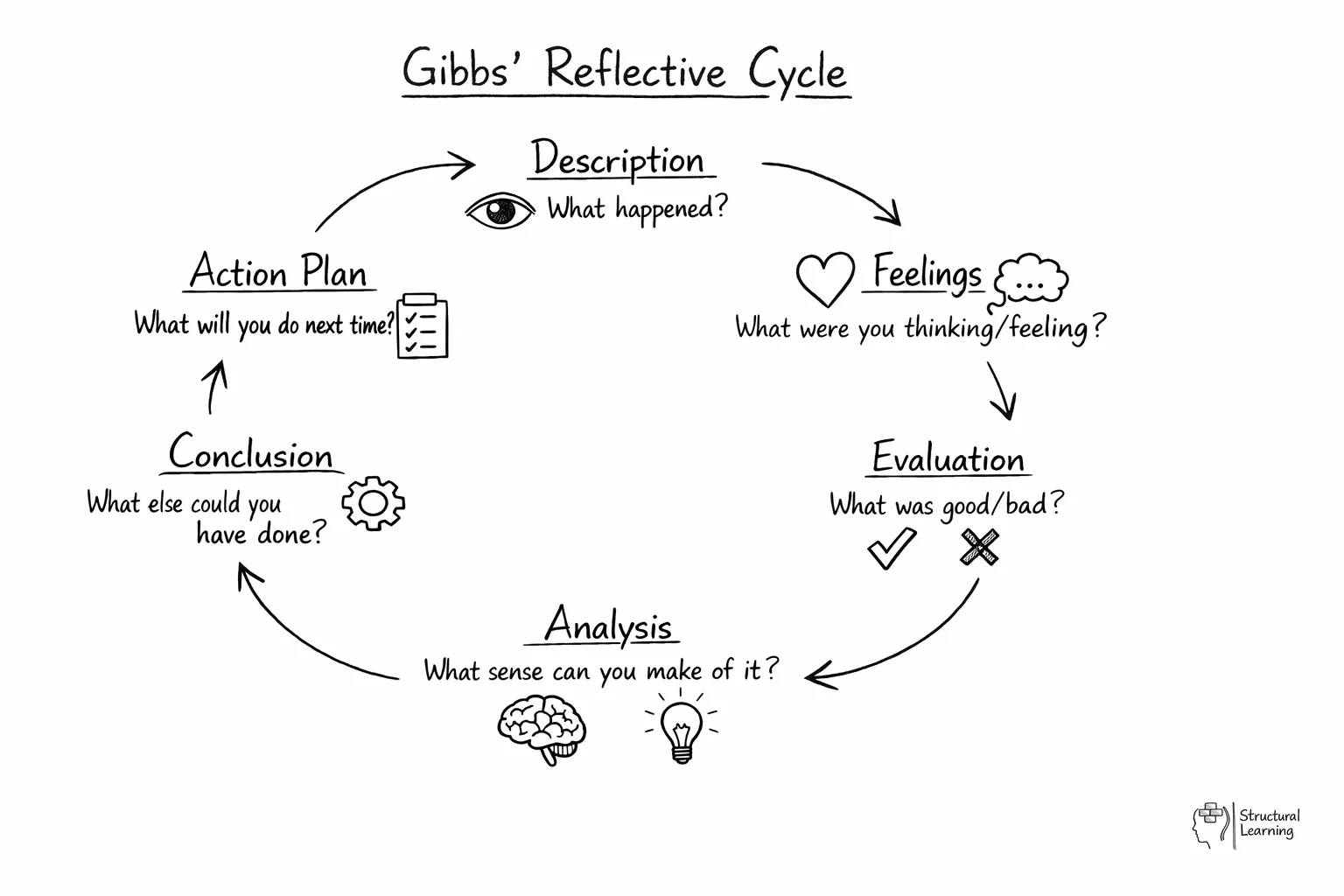

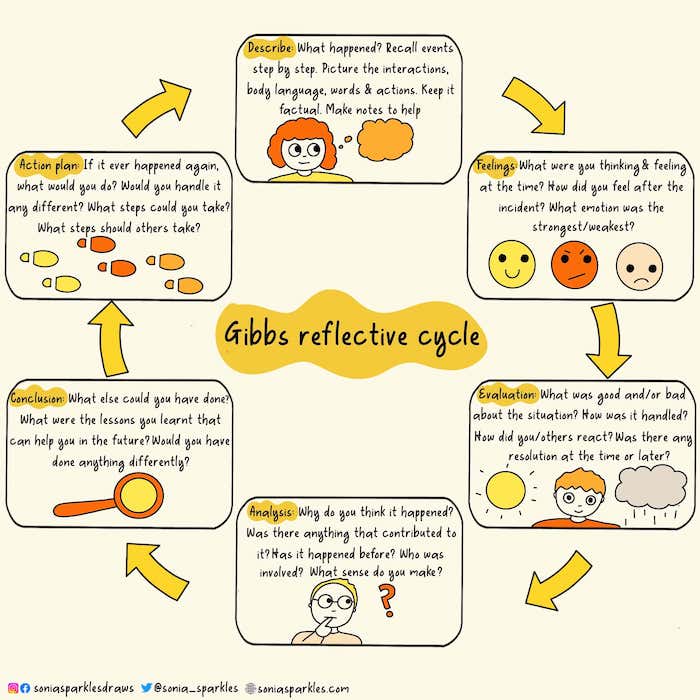

The cycle consists of six stages which must be completed in order for the reflection to have a defined purpose. The first stage is to describe the experience. This is followed by reflecting on the feelings felt during the experience, identifying what knowledge was gained from it, analysing any decisions made in relation to it and considering how this could have been done differently.

The final stage of the cycle is to come up with a plan for how to approach similar experiences in future.

Gibbs' Reflective Cycle encourages individuals to consider their own experiences in a more in-depth and analytical way, helping them to identify how they can improve their practise in the future

A survey from the British Journal of Midwifery found that 63% of healthcare professionals regularly used Gibbs' Reflective Cycle as a tool for reflection.

"Reflection is a critical component of professional nursing practise and a strategy for learning through practise. This integrative review synthesizes the literature on nursing students' reflection on their clinical experiences.", Beverly J. Bowers, RN, PhD

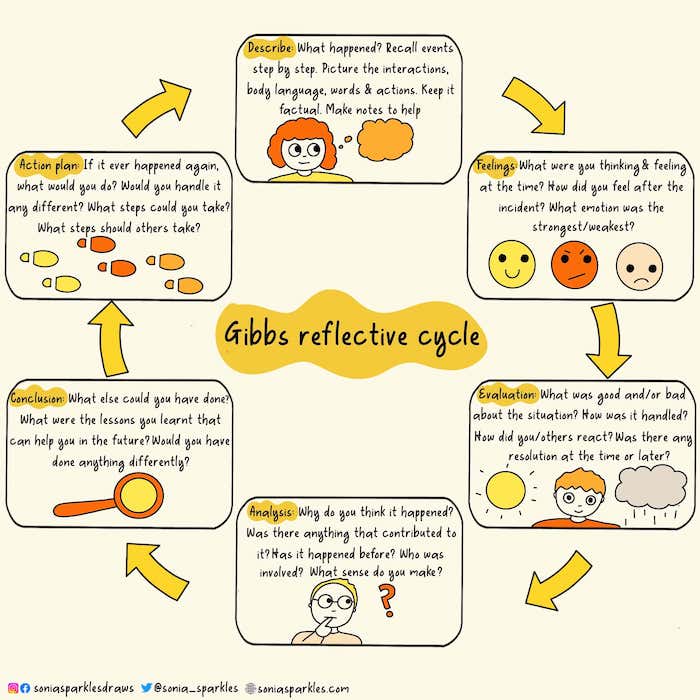

The six stages are: Description (what happened), Feelings (what were you thinking and feeling), Evaluation (what was good and bad), Analysis (what sense can you make of it), Conclusion (what else could you have done), and Action Plan (what will you do next time). Each stage builds on the previous one to create a thorough reflection process that moves from observation to concrete improvement strategies.

The Gibbs reflective cycle consists of six distinct stages: Description, Feelings, Evaluation, Analysis, Conclusion, and Action Plan. Each stage prompts the individual to examine their experiences through questions designed to incite deep and critical reflection. For instance, in the 'Description' stage, one might ask: "What happened?". This questioning method encourages a thorough understanding of both the event and the individual's responses to it (AlOtaibi et al., 2023).

To illustrate, let's consider a student nurse reflecting on an interaction with a patient. In the 'Description' stage, the student might describe the patient's condition, their communication with the patient, and the outcome of their interaction. Following this, they would move on to the 'Feelings' stage, where they might express how they felt during the interaction, perhaps feeling confident, anxious, or uncertain.

The 'Evaluation' stage would involve the student reflecting on their interaction with the patient, considering how they could have done things differently and what went well. In the 'Analysis' stage, the student might consider the wider implications of their actions and how this impacted on the patient's experience.

Finally, in the 'Conclusion' stage, the student would summarise their reflections by noting what they have learned from the experience. They would then set an 'Action Plan' for how they will apply this newfound knowledge in their future practise.

Gibbs' Reflective Cycle is a useful tool for nurses to utilise in order to reflect on their past experiences and improve their practise. By using reflective questions, nurses can actively engage in reflection and identify areas for improvement (Mahmoud & Bawaneh, 2025).

Teachers commonly use Gibbs' cycle to reflect on challenging lessons, student behaviour incidents, or new teaching strategies they've tried. For example, after a difficult class, a teacher might describe what happened, identify their frustration, evaluate what worked and didn't work, analyse why students were disengaged, conclude what alternative approaches could help, and create an action plan for the next lesson. This systematic approach transforms negative experiences into learning opportunities (McDonald et al., 2022).

The Gibbs Reflective Cycle, a model of reflection, can be a effective method for learning and personal development across various vocations. Here are five fictional examples:

These examples illustrate how the Gibbs Reflective Cycle can help learning and reflection across different vocations, leading to personal and professional growth (Tree & Worsfold, 2026).

The Description stage forms the foundation of effective reflection. Rather than rushing to judgment, this stage requires you to capture the objective facts of what occurred. Think of this as creating a factual record that separates observable events from your interpretations or emotional responses.

When documenting the description stage, use these targeted prompts to ensure thorough coverage:

Context: Wednesday morning, period 2 (9:45-10:45am), Week 4 of autumn term. Year 7 mixed-ability class of 28 students learning to add fractions with different denominators.

Description: I introduced the topic using a visual fraction wall displayed on the interactive whiteboard. Students were seated in mixed-ability groups of four. After a 10-minute whole-class introduction demonstrating the method with three worked examples, I distributed differentiated worksheets, green for foundation, amber for core, orange for extension.

Within five minutes, I noticed seven students with green worksheets had stopped working. When I approached the first group, two students said they "didn't get it" but couldn't articulate what they didn't understand. I re-explained the method to this group, then moved to check on other students.

By mid-lesson, twelve students were off-task, some chatting, others simply staring at blank worksheets. The students with orange worksheets worked independently and completed the tasks. The lesson ended with only approximately 40% of students completing even the first section of their worksheets.

The Feelings stage requires honest examination of your emotional response throughout the experience. This isn't about dwelling on emotions, but rather recognising how they influenced your decisions and perceptions. Emotional awareness directly impacts teaching effectiveness and professional resilience.

Initial feelings: I started the lesson feeling reasonably confident. I'd taught this topic successfully to Year 8 last year and spent time on Sunday evening creating differentiated resources. I felt well-prepared and organised.

During the lesson: My confidence shifted to concern around the 15-minute mark when I realised the green group wasn't progressing. This concern turned to frustration when I noticed students chatting instead of attempting the work. I felt professionally inadequate, questioning whether my explanation had been clear enough.

There was also a mounting sense of pressure as I tried to support struggling students whilst keeping the rest of the class on task. I noticed my patience wearing thin, particularly when one student asked me to "explain it again" for the third time.

After the lesson: I left feeling deflated and somewhat defensive. When a colleague asked how my morning went, I found myself blaming the class rather than examining my practise. That evening, I felt genuine worry about the students who didn't grasp the concept and frustration with myself for not reaching them effectively.

The Evaluation stage moves beyond emotional response to objective assessment. This stage requires balanced analysis of both strengths and weaknesses in your practise. The goal isn't to focus solely on what went wrong, but to identify specific elements that worked alongside those that didn't.

What worked well:

What didn't work well:

The Analysis stage is where most teachers struggle, yet it's the most critical for genuine professional development. This stage requires you to move beyond describing what happened to understanding why it happened. You should draw on pedagogical knowledge, educational research, and teaching theory to interpret the experience.

The Analysis stage gains depth when teachers draw on named theoretical frameworks rather than working from intuition alone. Three frameworks are particularly useful for classroom situations.

Belbin Team Roles (Belbin, 1981) help teachers analyse group work or collaborative incidents. If a group project stalled, consider whether the configuration lacked a co-ordinator to manage task distribution, or whether two dominant "shaper" personalities created conflict. Applying Belbin moves analysis from "the group didn't work" to a specific structural explanation that points towards a concrete remedy.

Groupthink (Janis, 1972) is relevant when a class appeared to agree unanimously in discussion, yet comprehension checks later revealed widespread misunderstanding. Groupthink occurs when social pressure suppresses dissent; pupils may nod and appear to follow when they are actually conforming to perceived group consensus. Naming groupthink in your analysis prompts targeted countermeasures: cold-calling, mini-whiteboards, or anonymous exit tickets that allow genuine individual responses.

Root Cause Analysis and the 5 Whys (Ohno, 1988) is a technique developed in manufacturing quality control but well-suited to the Analysis stage. Start with the observed problem and ask "why" five times in sequence. A lesson where pupils were off-task after 20 minutes might yield: pupils were off-task (problem) because the task was too hard (why 1) because instructions were unclear (why 2) because the slide was too text-heavy (why 3) because I ran out of preparation time (why 4) because I agreed to cover a colleague's lesson at short notice (why 5). The fifth answer reveals a workload issue, not a pedagogy issue, and points to a completely different solution.

Using at least one named framework in your Analysis stage entries signals to performance managers and portfolio reviewers that your reflection is theoretically grounded, a requirement of most formal teacher standards frameworks.

Pedagogical analysis: The lesson breakdown relates directly to

The success of the orange group demonstrates that higher-attaining students had sufficient prior knowledge of fractions and denominators to connect new learning to existing schemas. The green group likely had gaps in foundational knowledge (understanding what denominators represent, fluency with times tables needed for finding common denominators) that I hadn't identified or addressed.

Deeper issues: My differentiation strategy was overly simplistic. I differentiated the difficulty of content (different worksheets) but not the teaching approach. All students received the same whole-class input regardless of their starting points. Research on responsive teaching suggests I should have assessed prior knowledge first, then grouped students for targeted instruction at their level.

The time management issue, spending 15 minutes with struggling groups, reflects a reactive rather than proactive approach. By not building in check-for-understanding points, I only discovered problems when students were already off-task. Rosenshine's principles suggest regular checks during instruction would have revealed confusion earlier.

The Conclusion stage synthesises insights from the previous stages to identify alternative approaches. This isn't about self-criticism, but rather about professional learning, recognising what you now know that you didn't know before the experience.

Alternative approaches identified:

I now recognise that I could have structured the lesson completely differently. Instead of whole-class input followed by independent work, I should have:

Key learning: I've learned that my Year 7 class needs more scaffoldingthan I initially assumed, particularly when introducing new mathematical procedures. I've also realised that effective differentiation requires varying my teaching approach, not just the difficulty of tasks. The experience has highlighted a gap in my practise around checking for understanding before releasing students to independent work.

The Action Plan stage transforms reflection into concrete professional development. This stage requires specific, measurable actions that you can use in future practise. Vague intentions like "explain better" won't create change, you need precise strategies with clear success criteria.

Vague intentions do not survive the pressure of a busy school term. Structuring your Stage 6 commitments as SMART goals (Doran, 1981) increases the probability that they are acted on. Each action should be: Specific (name the exact strategy), Measurable (define what success looks like), Achievable (realistic given your current workload), Relevant (directly connected to what the analysis identified), and Time-bound (set a date for review).

A weak action plan entry reads: "improve questioning." A SMART version reads: "By the end of this half-term, use cold-calling with lolly sticks in at least three Year 9 lessons per week, and measure impact by comparing exit ticket scores from weeks 1 and 6." The second version specifies the strategy, the class, the frequency, the measurement tool, and the review point.

Formal CPD portfolios and performance management documentation require academic register. The following sentence starters are drawn from the conventions of professional reflective writing and can be adapted to any Gibbs reflection.

Immediate actions (this week):

Medium-term actions (this half-term):

Long-term professional development (this academic year):

Success criteria:

Even experienced educators can fall into unproductive reflection patterns. Recognising these common pitfalls helps you avoid them and maximise the professional learning value of Gibbs' Reflective Cycle.

Create a reflection template that includes prompts for all six stages, ensuring you can't skip critical elements. Schedule dedicated reflection time, even 15 minutes weekly, rather than rushing through it as an afterthought. Share reflections with a trusted colleague who can challenge vague statements and encourage deeper analysis. Most importantly, build review points into your action plan to assess whether implemented changes are actually improving your practise.

To support systematic reflection, teachers benefit from a structured template that guides them through all six stages without missing critical elements. A well-designed Gibbs' Reflective Cycle template should include:

The most effective approach is to complete the Description and Feelings stages immediately after the experience while details are fresh. The remaining stages benefit from distance, completing them later the same day or the next morning allows emotional reactions to settle and enables more objective analysis. Save completed templates in a dedicated reflection journal or digital folder organised by term. Review past reflections monthly to identify recurring patterns and track your professional development process over time.

Many schools provide standardised templates for performance management purposes, but personalising your template to match your subject area and career stage increases engagement and relevance. Early career teachers might include additional prompts about classroom management, whilst experienced teachers might focus more on curriculum development or pedagogical innovation.

Whilst Gibbs' Reflective Cycle was designed for professional development, adapted versions can powerfully improve student metacognitionand self-regulated learning. Teaching students to reflect systematically on their educational journeys develops critical thinking skills and learner autonomy.

For students, particularly at secondary level, simplify the language whilst maintaining the six-stage structure:

Description: We did an investigation about reaction rates, testing how temperature affects how fast antacid tablets dissolve. I worked with Amir and Jessica. We tested five different temperatures and timed how long the fizzing lasted.

Feelings: I felt excited at the start because I like practical work. I got frustrated in the middle because our first two results seemed wrong, they didn't follow the pattern I expected. I felt relieved when we realised we'd measured the temperature wrong and could redo it. At the end I felt proud because our graph showed a clear pattern.

Evaluation: What went well was our teamwork, we divided jobs clearly and Amir was really good at timing exactly. Our measurements were accurate once we fixed the thermometer problem. What didn't go well was we wasted 15 minutes before realising our mistake. Also, our conclusion could have been more detailed, we just said "higher temperature = faster reaction" without explaining why.

Analysis: The practical went better when we were organised and checked our method carefully. The mistake happened because I rushed and didn't read the thermometer scale properly. I learn best in science when I can see patterns in results, the graph really helped me understand the concept. Working in a three works better for me than pairs because if one person is unsure, the other two can discuss it.

Conclusion: I learned that reaction rate increases with temperature because particles have more energy to collide. I also learned that I need to slow down and check equipment carefully instead of rushing. Making mistakes isn't failing, it's part of the process if you learn from them.

Action Plan: Next practical, I will read equipment scales twice before recording measurements. I'll also spend more time on the conclusion, using my notes from the teacher's explanation to add scientific detail. I want to try being the person who records results next time because I usually time or measure, and I think recording would help me spot patterns quicker.

Introduce Gibbs' cycle gradually. Start with just Description, Feelings, and Evaluation for younger students or when first introducing the model. Model the process by completing a reflection together as a class after a shared experience.

Provide sentence starters for each stage to support students who struggle with open-ended writing. Use reflection as a learning tool, not an assessment, students should feel safe to be honest about difficulties without fear of judgement affecting their grades.

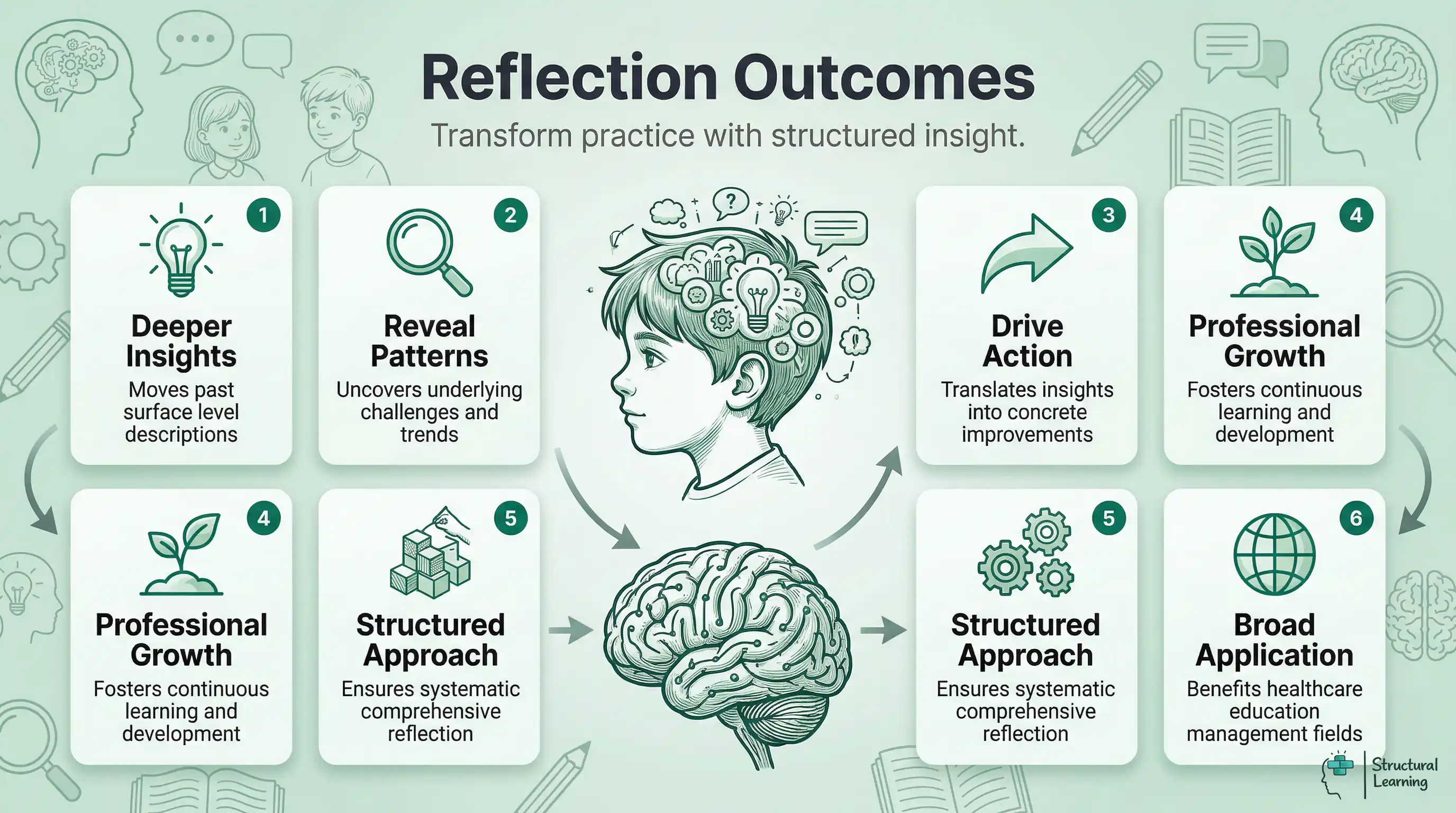

Gibbs' cycle is effective because it provides a clear structure that prevents superficial reflection and ensures practitioners examine experiences from multiple angles. The model's strength lies in its progression from description to action, forcing users to move beyond simply recounting events to understanding why things happened and planning concrete improvements. This systematic approach makes it particularly valuable for mandatory CPD requirements and performance reviews.

Gibbs' Reflective Cycle offers a structured approach to reflection, making it a helpful tool for educators and learners alike. The model encourages critical reflection, stimulating the ability to analyse experiences through questions and transform them into valuable learning opportunities.

Experiential Learning, a concept closely tied with reflection, suggests that we learn from our experiences, particularly when we engage in reflection and active experimentation. Gibbs' model bridges the gap between theory and practise, offering a framework to capture and analyse experiences in a meaningful way.

By using Gibbs' model, educators can guide students through their reflective process, helping them extract valuable lessons from their positive and negative experiences.

Many teaching standards and professional frameworks explicitly require evidence of reflective practise. Gibbs' Reflective Cycle provides a recognised, structured approach that satisfies these requirements whilst genuinely improving practise. When completing performance management documentation, use the six stages to structure your evidence. For example:

The cyclical nature of Gibbs' model aligns perfectly with the ongoing nature of professional development. Each action plan feeds into future descriptions, creating a continuous improvement loop that demonstrates career-long learning.

Teachers should use Gibbs' cycle after significant classroom events, challenging situations, or when trying new teaching methods. It's particularly valuable for weekly lesson reflections, after parent conferences, following student assessments, or when dealing with classroom management issues. Regular use helps develop reflective habits that improve teaching practise over time.

Rather than attempting to reflect deeply on every lesson, which becomes overwhelming and unsustainable, use Gibbs' cycle strategically:

The flexibility and simplicity of Gibbs' Reflective Cycle make it widely applicable in various real-world scenarios, from personal situations to professional practise.

For instance, Diana Eastcott, a nursing educator, utilised Gibbs' model to help her students' reflection on their clinical practise experience. The students were encouraged to reflect on their clinical experiences, analyse their reactions and feelings, and construct an action plan for future patient interactions. This process not only enhanced their professional knowledge but also developed personal growth and emotional resilience.

In another example, Bob Farmer, a team leader in a tech company, used Gibbs' Cycle to reflect on a project that didn't meet expectations. He guided his team through the reflective process, helping them identify areas for improvement and develop strategies for better future outcomes.

These scenarios underline the versatility of Gibbs' model, demonstrating its value in both educational and professional settings.

Consistency matters more than perfection. Even 15 minutes of structured reflection weekly creates more professional development than sporadic lengthy reflections. Create a reflection routine by blocking time in your calendar, many teachers find Friday afternoon or Sunday evening works well for processing the week's experiences. Keep your reflection journal or digital document easily accessible so you can jot quick notes throughout the week that you'll develop later during dedicated reflection time.

Gibbs' cycle supports professional growth by providing a framework that transforms everyday teaching experiences into learning opportunities. The structured approach helps teachers identify patterns in their practise, recognise areas for improvement, and develop research-backed strategies for enhancement. This systematic reflection directly feeds into professional development plans and helps teachers demonstrate continuous improvement.

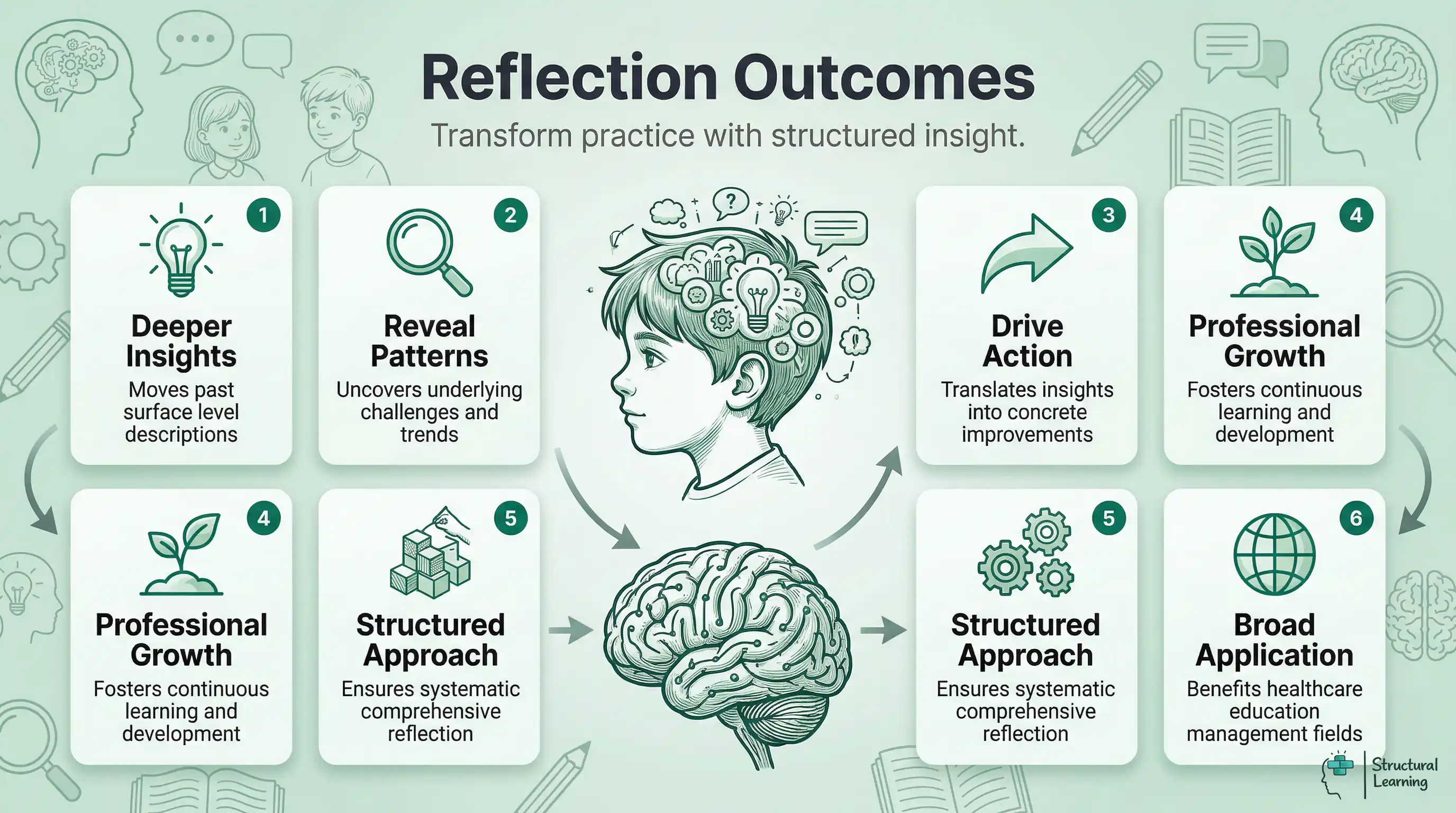

The use of Gibbs' Reflective Cycle can have profound effects on personal and professional development. It aids in recognising strengths, weaknesses, and areas for improvement, providing an avenue for constructive feedback and self-improvement.

In the context of professional development, Gibbs' model promotes continuous learning and adaptability. By transforming bad experiences into learning opportunities, individuals can improve their competencies and skills, preparing them for similar future situations.

Moreover, the reflective cycle promotes emotional intelligence by encouraging individuals to explore their feelings and reactions to different experiences. Acknowledging and understanding negative emotions can lead to increased resilience, better stress management, and improved interpersonal relationships.

One powerful but often overlooked benefit of Gibbs' cycle is the developmental record it creates when used consistently. Save and date your reflections, then review them termly or annually. You'll notice patterns emerging:

This documented evidence of professional growth provides powerful material for career progression applications, performance reviews, and your own motivation during difficult periods. It also helps you recognise when you've genuinely developed expertise in areas that once felt overwhelming.

Unlike simple diary entries or casual reflection, Gibbs' cycle requires systematic analysis through six distinct stages that build towards actionable improvements. The model's Analysis stage specifically pushes practitioners to examine underlying causes and patterns rather than stopping at surface-level observations. This depth ensures that reflection leads to genuine professional learning and concrete changes in practise.

Gibbs' Reflective Cycle is a practical tool that transforms experiences into learning. It incorporates principles of Experiential Learning and emphasises abstract conceptualization and active experimentation in the learning process.

In the field of education, Gibbs' model can significantly influence teaching methods. It encourages educators to incorporate reflective practices in their teaching methods, promoting a deeper understanding of course material and facilitating the application of theoretical knowledge in practical scenarios.

Moreover, the model can be used to encourage students to reflect on their experiences, both within and outside the classroom, and learn from them. This process creates critical thinking, problem-solving skills, and personal growth, equipping students with the skills they need for lifelong learning.

| Approach | Characteristics | Professional Value |

|---|---|---|

| Diary Reflection | Records what happened and how you felt; chronological narrative; no structured analysis | Limited, documents experience but rarely leads to systematic improvement |

| Informal Reflection | Thinking about lessons during commute or breaks; mental processing; no documentation | Moderate, develops reflective habits but insights often forgotten without recording |

| Peer Discussion | Talking through experiences with colleagues; collaborative; external perspectives | High, valuable for gaining new perspectives but can lack structure and follow-through |

| Gibbs' Reflective Cycle | Six-stage structured process; moves from description through analysis to action planning; documented | Very High, systematic, leads to concrete improvements, creates evidence trail for CPD |

The key difference is that Gibbs' cycle doesn't allow you to skip the difficult analysis stage or leave reflection as abstract musing. The structure forces deeper engagement with your practise and ensures reflection translates into action.

Schools can use Gibbs' cycle by incorporating it into professional development programmes, peer observation frameworks, and performance management processes. Start by training staff in the six stages, providing templates and examples, then integrate the cycle into regular meeting structures and CPD activities. Successful implementation requires leadership support and clear expectations about when and how staff should use the framework.

Effective school-wide adoption of Gibbs' Reflective Cycle requires a phased approach:

Phase 1: Introduction and Training (Term 1)

Phase 2: Integration with Existing Systems (Term 2)

Phase 3: Embedded Practise (Term 3 onwards)

Here's a list of guidance tips for organisations interested in embracing Gibbs' Reflective Cycle as their professional development model.

Both Kolb's Experiential Learning Theory and Gibbs' Reflective Cycle are influential learning methods used extensively in education and professional development. While they share similarities, such as promoting a cyclical learning process and developing a deeper understanding of experiences, there are key differences.

Kolb's cycle consists of four stages: Concrete Experience, Reflective Observation, Abstract Conceptualization, and Active Experimentation. It focuses more on the transformation of direct experience into knowledge, emphasising the role of experience in learning.

On the other hand, Gibbs' cycle, with its six stages, places a greater emphasis on emotions and their impact on learning. For example, a team leader might use Kolb's cycle to improve operational skills after a failed project, focusing on what happened and how to improve. However, using Gibbs' cycle, the same leader would also reflect on how the failure made them feel, and how those feelings might have influenced their decision-making.

Gibbs' cycle works particularly well when:

Kolb's cycle may be more appropriate when:

Many practitioners find value in using both models at different times, selecting the framework that best matches the nature of the experience they're reflecting upon.

| Learning Cycle Theory | Origin | Application |

|---|---|---|

| Experiential Learning Theory (ELT) | Developed by David Kolb in the 1980s. It's based on the work of John Dewey, Kurt Lewin, and Jean Piaget. | It's widely used in professional development and higher education settings. It helps learners gain knowledge from their experiences by going through four stages: Concrete Experience, Reflective Observation, Abstract Conceptualization, and Active Experimentation. |

| 5E Instructional Model | Developed by the Biological Sciences Curriculum Study (BSCS) in the 1980s. | This model is popular in science education. It includes five phases: Engagement, Exploration, Explanation, Elabouration, and Evaluation. It promotes inquiry-based learning and active engagement. |

| ADDIE Model | The origins can be traced back to the US Military in the 1970s. | It's widely used in instructional design and training development. The five phases are Analysis, Design, Development, Implementation, and Evaluation. |

| Kemp Design Model | Developed by Jerold Kemp in the late 1970s. | This model is used in instructional design. It emphasises continuous revision and flexibility throughout the learning cycle, including nine components that are considered simultaneously and iteratively. |

| Gagne's Nine Events of Instruction | Developed by Robert Gagne in the 1960s. | This is commonly used in instructional design and teaching. It includes nine steps: Gain attention, Inform learners of objectives, Stimulate recall of prior learning, Present the content, Provide learner guidance, Elicit performance, Provide feedback, Assess performance, and improve retention and transfer. |

| ARCS Model of Motivational Design | Developed by John Keller in the 1980s. | This model is used to improve learners' motivation. The four components are Attention, Relevance, Confidence, and Satisfaction. It is widely used in e-learning and instructional design. |

| Bloom's Taxonomy | Developed by Benjamin Bloom in the 1950s. | It is used to classify educational learning objectives into levels of complexity and specificity. The taxonomy consists of six levels: Remembering, Understanding, Applying, analysing, Evaluating, and Creating. It is widely used in education to design lesson plans and assessments. |

Please note that each of these theories or models has been developed and refined over time, and they each have their own strengths and weaknesses depending on the specific learning context or goals.

The main benefits include improved classroom practise through systematic reflection, better professional development outcomes, and enhanced ability to handle challenging classroom situations. Teachers who regularly use Gibbs' cycle report increased confidence in trying new strategies and better understanding of student needs. The framework also provides clear documentation for performance reviews and professional portfolios.

Gibbs' Reflective Cycle is an invaluable tool for nurturing professional skills and developing personal growth. By systematically integrating this reflective model into educational practices, institutions can significantly improve their students' professional development (Tobondo, 2025).

Here are seven effective ways educational institutions can use the power of Gibbs' Reflective Cycle to boost skill acquisition, operational proficiency, leadership capabilities, and personal skills mastery.

Teachers can start by selecting one significant classroom event per week and working through all six stages using a template or journal. Begin with shorter reflections of 15-20 minutes, focusing on completing each stage rather than perfection. As the process becomes familiar, extend to more complex situations and use the cycle for collaborative reflection with colleagues.

To complete your first Gibbs' reflection effectively, follow this practical approach:

Step 1: Choose Your Focus (2 minutes)

Select a recent lesson or teaching experience that stands out, either because it went particularly well, presented challenges, or involved trying something new. Don't overthink this; your first reflection doesn't need to be about a dramatic incident.

Step 2: Description (5 minutes)

Write a factual account of what happened. Use the prompts provided earlier, but don't aim for perfection. Capture the key events in chronological order without judging them yet.

Step 3: Feelings (3 minutes)

Identify your emotional responses using specific words. If you're stuck, use an emotion wheel to pinpoint precise feelings beyond "good" or "bad".

Step 4: Evaluation (5 minutes)

Create two quick lists, what worked and what didn't. Include at least three points in each list to ensure balanced evaluation.

Step 5: Analysis (7 minutes)

This is the challenging part. Ask yourself: "Why did the successful parts work?" and "What caused the difficulties?" Try to reference at least one teaching principle or theory you're familiar with.

Step 6: Conclusion (3 minutes)

Summarise your key learning points. What do you now understand about this situation or your practise that you didn't realise before?

Step 7: Action Plan (5 minutes)

Write 2-3 specific actions you'll take, with timescales. Make these concrete and measurable rather than vague intentions.

For further reading on this topic, explore our guide to Securing more objective news sources for our students.

For further reading on this topic, explore our guide to Addie Model.

Total time: 30 minutes for your first reflection. As you become more experienced, you'll complete this process more quickly whilst maintaining depth.

In the process of life and work, we continuously encounter new situations, face challenges, and make decisions that shape our personal and professional trajectory. It's in these moments that Gibbs' Reflective Cycle emerges as a guiding compass, providing a structured framework to analyse experiences, draw insights, and plan our future course of action.

Underlying the model is the philosophy of lifelong learning. By encouraging critical reflection, it helps us to passively experience life and to actively engage with it, to question, and to learn. It's through this reflection that we move from the field of 'doing' to 'understanding', transforming experiences into knowledge.

Moreover, the model emphasises an action-oriented approach. It propels us to use our reflections to plan future actions, promoting adaptability and growth. Whether you're an educator using the model to improve your teaching methods, a student exploring the depths of your learning process, or a professional striving for excellence in your field, Gibbs' Reflective Cycle can be a effective method.

In an ever-changing world, where the pace of change is accelerating, the ability to learn, adapt, and evolve is paramount. Reflective practices, guided by models such as Gibbs', provide us with the skills and mindset to work through this change effectively. They helps us to learn from our past, be it positive experiences or negative experiences, and use these lessons to shape our future.

From developing personal growth and emotional resilience to enhancing professional practise and shaping future outcomes, the benefits of Gibbs' Reflective Cycle are manifold. As we continue our process of growth and learning, this model serves as a beacon, illuminating our path and guiding us towards a future of continuous learning and development.

Key resources include Gibbs' original 1988 text 'Learning by Doing', practical guides from teaching colleges, and online templates specifically designed for educational contexts. Many universities provide free downloadable worksheets and video tutorials that demonstrate each stage of the cycle. Professional development courses often include modules on reflective practise using Gibbs' framework.

Here is a list of five key studies examining the effectiveness of Gibbs' Reflective Cycle in promoting critical reflection across different domains. These studies explore the cycle's structured approach in enhancing reflective practise, its role as a helpful and practical tool, and how it informs future actions.

These studies collectively illustrate the broad applicability of Gibbs' Reflective Cycle across academic, professional, and healthcare settings, reinforcing its role as a structured and practical tool for developing reflective practise.

Stephen Brookfield (1995) argued in Becoming a Critically Reflective Teacher that the central problem with most reflective practice is that teachers reflect through a single lens: their own perspective. This produces blind spots. A teacher who evaluates a lesson only through their own experience may conclude it went well when pupils experienced it as confusing, or may attribute a problem to pupil behaviour when colleagues would recognise it as a planning issue. Brookfield proposed viewing every significant teaching experience through four distinct lenses.

The autobiographical lens asks teachers to examine their own experience as both teacher and learner, surfacing the assumptions that shape their practice. The students' eyes lens asks them to access pupil perceptions through anonymous feedback, learning logs, or exit tickets, discovering what the experience felt like from the other side of the desk. The colleagues' lens involves peer observation, team teaching, or structured professional conversations that reveal aspects of practice invisible to the practitioner. The theoretical literature lens asks teachers to read research and theory that might challenge or explain their experience. For teachers already using Gibbs, Brookfield's four lenses provide a powerful way to deepen Stage 4 (Analysis). Rather than analysing an experience from a single viewpoint, the teacher can work through the same event four times, each lens revealing patterns that the others miss. A Year 10 lesson that felt successful through the autobiographical lens may look different through student feedback, and different again when viewed through the research on questioning wait time.

Gibbs's Stage 2 (Feelings) asks practitioners to identify and record their emotional responses. This is not merely a warm-up exercise before the "real" analysis begins. Psychological research suggests that the act of labelling emotions is itself a regulatory mechanism. Lieberman and colleagues (2007) demonstrated through fMRI studies that affect labelling, putting feelings into words, reduces activation in the amygdala (the brain's threat-detection centre) and increases activation in the right ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (associated with cognitive control). In practical terms, writing "I felt frustrated and inadequate" does not simply record the feeling; it begins to diminish its intensity.

James Pennebaker's (1997) expressive writing research showed that structured writing about stressful experiences for as little as 15 minutes over three to four days produced measurable reductions in cortisol levels, fewer visits to the doctor, and improved immune function. For teachers, who consistently report high levels of occupational stress, the Feelings stage of Gibbs's cycle may function as a form of cognitive reappraisal (Gross, 1998): by naming and externalising emotional responses, the reflector creates psychological distance from the experience and reduces its capacity to trigger rumination. Maslach's (1982) research on burnout identified emotional exhaustion as the first and most predictive dimension. Teachers who routinely process difficult emotional experiences through structured reflection rather than suppressing or ruminating on them may be building a buffer against the cumulative toll that leads to burnout. The Feelings stage, often treated as the least analytical part of Gibbs's model, may be its most psychologically important.

Gibbs' Reflective Cycle is a structured six-stage framework developed by Graham Gibbs in 1988 that transforms surface-level descriptions into powerful tools for professional growth. Unlike simple diary entries that merely record what happened, this model systematically guides educators through implementation planning to create meaningful development opportunities.

The six stages are Description (what happened), Feelings (thoughts and emotions), Evaluation (what was good and bad), Analysis (making sense of the experience), Conclusion (what else could have been done), and Action Plan (future approach). Each stage builds on the previous one to create a thorough reflection process that moves systematically from observation to concrete improvement strategies.

Teachers commonly use the cycle to reflect on challenging lessons, student behaviour incidents, or new teaching strategies. For example, after a difficult class, they would describe what happened, identify their emotions, evaluate successes and failures, analyse why students were disengaged, conclude alternative approaches, and create an action plan for future lessons.

Most teachers stop at identifying 'what went wrong' in the evaluation stage and miss the analysis phase where they draw on professional knowledge and literature to understand why things unfolded as they did. This analysis stage is important because it reveals underlying patterns in classroom challenges and transforms observations into deeper professional insights.

Instead of treating CPD reflections as a tick-box exercise, teachers can use the six-stage framework to structure their professional development systematically. This approach ensures they move beyond surface-level reporting to genuine analysis and concrete action planning that directly improves their instructional approach.

The main challenge is moving beyond the comfortable description and evaluation stages to engage in deeper analysis that requires drawing on professional knowledge and research. Teachers may also struggle with being honest about their emotions in the feelings stage or creating specific, actionable plans rather than vague intentions for improvement.

The action planning stage transforms reflective insights into concrete, implementable strategies by requiring teachers to specify exactly what they will do differently in similar future situations. This final stage prevents reflection from becoming merely an intellectual exercise and ensures it leads to tangible changes in pedagogical methods that 'actually stick'.

The feelings stage of Gibbs' Reflective Cycle serves as more than a simple emotional inventory. Recent research by Saraçoğlu et al. highlights how emotional experiences in educational settings occur within complex sociocultural contexts, where interactions can be emotionally intense.

For teachers, this stage requires honest examination of both their own emotions and their students' emotional responses during the teaching experience. Rather than dismissing feelings as irrelevant to professional practise, this stage recognises emotions as valuable data that inform teaching effectiveness.

When engaging with this stage, teachers should explore emotions chronologically: initial feelings before the lesson, emotional shifts during teaching moments, and residual feelings afterwards. Chaudhri et al. (2023) found that emotions tend to have a significant impact on students' learning outcomes, making it important for teachers to understand the emotional climate of their classroom.

Consider recording specific triggers for emotional responses, such as a student's unexpected question that caused anxiety or the satisfaction felt when a struggling pupil grasped a difficult concept. This detailed emotional mapping reveals patterns that might otherwise remain hidden.

A critical skill in this stage involves separating personal emotional responses from professional ones. For instance, frustration with a challenging student might stem from personal tiredness rather than the student's behaviour itself. Teachers should ask themselves: "Would I have felt differently if this happened at a different time or under different circumstances?" This distinction prevents misattribution and leads to more accurate analysis in later stages. Research by Mokhele- demonstrates how understanding emotional responses shapes attitudes and behaviours, suggesting that teachers who accurately identify their emotional triggers can better manage classroom dynamics.

The feelings stage also requires acknowledging uncomfortable emotions without judgement. Many teachers feel pressured to maintain perpetual positivity, yet recognising feelings of disappointment, inadequacy, or even anger provides important insights for professional development. Document these emotions using specific language rather than general terms: instead of writing "felt bad," specify whether you felt overwhelmed, underprepared, or dismissed.

This precision creates a richer foundation for the evaluation stage that follows, where you'll assess what went well and what didn't. Remember, the goal isn't to eliminate negative emotions but to understand their sources and impacts on your teaching practise.

There is a strong cognitive science rationale for why Gibbs placed Feelings as Stage 2 rather than leaving emotion to emerge incidentally throughout reflection. Research in cognitive reappraisal, a process of consciously relabelling emotional experiences, shows that naming and examining an emotion reduces its neurological intensity. Gross (1998) demonstrated that reappraisal applied early in an emotional episode produces better outcomes than suppression applied late; the Feelings stage, completed before analysis, performs precisely this function.

Lieberman et al. (2007) found that labelling a negative emotion in words reduced activity in the amygdala, the brain region associated with threat response, whilst increasing activity in the prefrontal cortex, where reasoned analysis occurs. For teachers, this means that writing "I felt undermined when the class ignored my instructions" is not an indulgent exercise. It is a neurologically productive act that prepares the brain for the objective analysis required in Stage 4.

This also explains a common observation in CPD workshops: teachers who skip the Feelings stage and move straight to Analysis tend to produce evaluations that are either overly harsh (if unprocessed frustration bleeds into judgement) or overly defensive (if unprocessed shame prompts self-protection). Completing Stage 2 honestly is what makes Stage 4 rigorous.

The practical implication for your reflection routine: write the Feelings stage in the first person and in specific terms. "I felt anxious from the moment the year group entered, because I had not prepared a backup activity" is more analytically useful than "it was a stressful lesson." The specificity creates data; the data informs the analysis. Research on emotional granularity by Kashdan et al. (2015) supports this: people with finer-grained emotional vocabulary demonstrate greater psychological resilience and more adaptive responses to setbacks, both capacities that protect against teacher burnout.

The evaluation stage marks a critical turning point in Gibbs' Reflective Cycle where teachers move beyond emotional responses to make objective judgements about their classroom experiences. Unlike the feelings stage, evaluation requires you to step back and assess both the positive and negative aspects of a situation without letting emotions cloud your judgement. This balanced approach prevents the common teaching trap of focusing solely on what went wrong, which research by MacNeil et al. (2023) suggests can limit professional growth when stakeholders engage in one-sided evaluations of their experiences.

Effective evaluation in teaching contexts requires a structured approach that goes beyond simple 'good' or 'bad' categorisations. Start by identifying specific elements that worked well, such as a particular questioning technique that sparked student engagement or a classroom management strategy that maintained focus during transitions. Then examine what didn't work, but frame these observations constructively. For instance, rather than noting "the group work failed," evaluate specific aspects: "Students in mixed-ability groups completed tasks at different speeds, leaving some disengaged." This granular approach to evaluation provides clearer direction for the analysis stage that follows.

To ensure balanced evaluation, create two columns labelled "Effective Elements" and "Areas for Development." Under each, list specific observations with brief evidence. For example, under "Effective Elements," you might write: "Visual timer on board, 95% of students transitioned within 2 minutes." This technique prevents the natural tendency to dwell on negatives whilst ensuring you capture successful strategies that might otherwise be forgotten. The evaluation stage differs from peer-based faculty evaluation discussed by Akins and Murphy (2019), as it focuses on self-assessment rather than external judgement, making it less threatening and more conducive to honest reflection.

A important but often overlooked aspect of evaluation is considering unintended outcomes. Perhaps your carefully planned differentiated worksheet inadvertently highlighted ability gaps, affecting student confidence. Or maybe your attempt to incorporate technology enhanced engagement but reduced meaningful peer interaction.

These unexpected results often provide the richest material for professional development. By evaluating both intended and unintended outcomes, you create a thorough picture that feeds directly into the analysis stage, where you'll explore why these outcomes occurred and identify patterns across multiple teaching experiences.

Whilst both Gibbs' Reflective Cycle and Kolb's Experiential Learning Cycle encourage systematic reflection, they serve distinctly different purposes in the classroom. Kolb's model, developed in 1984, focuses on how we learn from experiences through four stages: concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualisation, and active experimentation. In contrast, Gibbs' model specifically targets improving future practise through deeper emotional and analytical reflection.

The key difference lies in their approach to feelings and evaluation. Kolb's cycle treats reflection as part of a continuous learning process, moving quickly from observation to forming new theories. Gibbs, however, dedicates entire stages to exploring emotions and critically evaluating what went well or poorly. For instance, when reflecting on a challenging behaviour incident, Kolb's model might lead you to observe patterns and test new strategies, whilst Gibbs' framework would first have you examine your emotional response, analyse why certain interventions failed, and create specific action plans.

For classroom teachers, Gibbs' model often proves more practical for post-lesson reflection and professional development. The structured approach to feelings helps teachers process difficult classroom moments, whilst the evaluation and analysis stages reveal patterns in teaching effectiveness. Consider using Kolb's cycle when planning new teaching methods or experimenting with classroom layouts, but turn to Gibbs when you need to understand why a particular lesson succeeded or failed.

Research by Moon (2004) suggests that combining both models can enhance reflective practise. Start with Kolb's cycle during lesson planning to incorporate different learning styles, then apply Gibbs' framework afterwards to evaluate effectiveness and plan improvements. This dual approach transforms both your teaching methodology and your ability to learn from classroom experiences.

Gibbs' Reflective Cycle belongs to a broader tradition of reflective frameworks. Understanding where it sits alongside Donald Schön's and Gary Rolfe's models clarifies when to use each one and strengthens the theoretical case for structured post-lesson reflection.

The intellectual roots of all three models trace back to Dewey's theory of reflective thinking, which first proposed that professional learning requires a deliberate cycle of experience, observation, and revised action rather than simple habit or trial and error (Dewey, 1910). Schön's later distinction between reflection-in-action and reflection-on-action was a direct extension of this Deweyan framework, and Gibbs' six-stage cycle operationalised it for CPD practice.

Donald Schön (1983) distinguished between two fundamentally different types of professional reflection. Reflection-in-action occurs during an event: the experienced teacher who senses a lesson losing momentum and adjusts questioning strategies on the spot, without pausing to analyse why. Reflection-on-action occurs after the event: the same teacher, at the end of the day, working through what happened and why. Gibbs' Reflective Cycle is a structured tool for reflection-on-action. Its six stages make explicit the cognitive moves that expert practitioners make intuitively after a lesson ends.

This distinction matters for teachers because it shows that neither type of reflection replaces the other. Schön's framework suggests that reflection-in-action develops through experience and builds the responsive teaching instinct that Rosenshine's principles describe as "well-practised routines." Reflection-on-action, structured through Gibbs, builds the analytical capacity that makes those instincts more accurate over time (Schön, 1983).

In practice: a Year 10 English teacher notices mid-lesson that pupils are producing very short written responses. Reflection-in-action leads her to switch from silent writing to a brief paired discussion. Later, reflection-on-action via Gibbs helps her realise that pupils lacked vocabulary for the topic, and she plans a pre-teaching vocabulary activity for the next lesson.

When Gibbs' six stages feel too time-consuming for daily use, Rolfe, Freshwater and Jasper (2001) offer a three-question alternative. The framework distils structured reflection into three prompts:

The Rolfe framework is better suited to mid-week informal reflections, brief written records in a CPD journal, or situations where teachers have five minutes rather than thirty. Gibbs remains the stronger choice when writing a formal observation response, preparing a professional review portfolio, or unpacking a complex classroom event where the emotions involved are significant. Think of the two models as working at different resolutions: Rolfe sketches the outline; Gibbs fills in the detail (Rolfe et al., 2001).

A primary teacher might use Rolfe's framework after every lesson in a bullet-point journal, then switch to Gibbs when a particular lesson warrants deeper examination, such as a lesson where a pupil became distressed or where a new behaviour strategy clearly failed.

| Model | Stages | Best Used For | Time Required |

|---|---|---|---|

| Schön (1983) | Reflection-in-action / Reflection-on-action | Building expert instinct; in-the-moment adjustment | Instantaneous to hours |

| Rolfe et al. (2001) | What? So what? Now what? | Daily journalling; quick CPD records | 5 to 10 minutes |

| Gibbs (1988) | Six stages: Description to Action Plan | Formal CPD portfolios; post-observation analysis; complex incidents | 20 to 45 minutes |

| Kolb (1984) | Concrete Experience, Reflective Observation, Abstract Conceptualisation, Active Experimentation | Lesson planning; testing new pedagogical approaches | 30 to 60 minutes |

While many teachers understand the six stages of Gibbs' Reflective Cycle, they often struggle with knowing exactly what to ask themselves at each stage. Simply knowing the stages isn't enough; you need targeted questions that probe deeper into your teaching practise. on critical design strategies demonstrates that structured questioning methods significantly improve reflective thinking, a principle that applies directly to classroom reflection.

The quality of your reflection depends entirely on the questions you ask. Generic prompts like data.

As you move through the cycle, your questions should build upon previous insights. In the Feelings stage, avoid stopping at "I felt frustrated." Instead, probe with: "What specific moment triggered this emotion?" and "How did my emotional state influence my teaching decisions?" The Analysis stage, often the most neglected, requires questions that connect theory to practise: "Which pedagogical principles were at play when the lesson succeeded/failed?" and "What patterns emerge when I compare this experience to similar situations?"

The final stages demand forwards-thinking questions. For the Conclusion stage, ask: "What would I need to change about my planning, not just my delivery?" and "Which of my teaching assumptions has this experience challenged?" The Action Plan stage moves beyond vague intentions with questions like: "What specific resources or support do I need to use this change?" and "How will I measure whether my new approach works?" This progression mirrors the taxonomy development process described by Finelli and Borrego (2014), where systematic questioning leads to clearer categorisation and understanding of complex educational phenomena.

Transform these questions into a personal reflection toolkit by adapting them to your subject area and teaching context. A science teacher might focus questions on laboratory management and practical demonstrations, whilst a primary teacher could emphasise questions about differentiation across ability levels. The key is maintaining the progressive depth whilst making each question relevant to your specific classroom challenges.

Enhancing professional identity formation in health professions: A multi-layered framework for educational and reflective practise

7 citations

Avita Rath (2024)

Though focused on health professions, this paper offers teachers a framework for understanding how reflective practise shapes professional identity development. Teachers can apply these insights to help students in professional or vocational programmes think critically about how their personal values align with their career responsibilities, making reflection more meaningful and identity-focused rather than just a routine exercise.

AI in the Classroom: A Systematic Review of Barriers to Educator Acceptance

2 citations

This systematic review identifies the key obstacles teachers face when deciding whether to adopt AI technologies in their classrooms. Understanding these barriers, from lack of training to concerns about job security and student data privacy, helps teachers and administrators address resistance thoughtfully and use AI tools more effectively through informed reflection on their concerns and needs.

AI in Higher Education: Initial Teacher Training in the Critical and Didactic Use of Artificial Intelligence

2 citations

Sebastián Martín-Gómez & C. J. González

This study demonstrates how teacher training programmes can integrate AI tools like ChatGPT and Gemini into coursework through a structured six-phase approach emphasising critical thinking and verification. Teachers can learn from this model to thoughtfully incorporate AI into their own practise, using reflection to question outputs, compare sources, and verify information rather than accepting AI-generated content uncritically.

Emotional labour as teaching expertise: reflective practices for teacher professional development workshops

1 citations

This research highlights the often-overlooked emotional demands of teaching, from managing difficult parent conversations to supporting struggling students, and argues that reflective practise should address these challenges explicitly. Teachers can benefit from professional development that includes reflection on emotional labour, helping them develop strategies for managing stress and building relationships while maintaining their wellbeing and effectiveness in the classroom.

REFLECTIVE TEACHING Towards EFL TEACHERS' PROFESSIONAL AUTONOMY: REVISITING ITS DEVELOPMENT IN INDONESIA 16 citations

Lubis et al. (2018)

This paper examines the development of reflective teaching practices among English as a Foreign Language teachers in Indonesia over 25 years, focusing on how reflection promotes teacher autonomy and continuous professional development. It is valuable for teachers learning about Gibbs' Reflective Cycle as it demonstrates the real-world application and long-term benefits of structured reflection in teaching practise, particularly in developing critical thinking skills and lifelong learning habits.

Revitalising reflective practise in pre-service teacher education: developing and practising an effective framework 17 citations

Roberts et al. (2021)

This research develops and tests a framework to help pre-service teachers understand and practise reflective thinking effectively, addressing common difficulties students face in grasping reflection. It is particularly relevant for teachers exploring Gibbs' Reflective Cycle as it provides research-informed strategies for implementing structured reflection frameworks and demonstrates how systematic approaches to reflection can be taught and developed in educational settings.

Promoting pre-service teachers' professional vision of classroom management during practical school training: Effects of a structured online- and video-based self-reflection and feedback intervention 141 citations

Weber et al. (2018)

This study investigates how structured online and video-based reflection and feedback interventions can improve pre-service teachers' ability to analyse and understand classroom management during practical training. It is relevant to teachers using Gibbs' Reflective Cycle as it demonstrates how technology-enhanced structured reflection can be applied to specific teaching challenges, showing practical ways to use systematic reflection processes in teacher development.

Research on reflective teaching practices for professional development 150 citations demonstrates how structured reflection enhances teachers' pedagogical skills and classroom effectiveness through systematic self-evaluation and continuous improvement strategies.

Boris et al. (2021)

This paper explores how reflective teaching approaches can improve teacher professional development, positioning reflective practices as essential tools for ongoing teacher growth and improvement. It is directly relevant to teachers learning about Gibbs' Reflective Cycle as it provides broader context for why structured reflection matters in teaching and demonstrates the connection between systematic reflection and continuous professional development.

Experiential Learning-Oriented Reform of Art Education for Preschool Children: Focusing on the Core Competencies of Pre-Service Teachers View study ↗

Yun Zhu & Di Zhang (2025)

This research tackles the common problem of teacher training programmes being too theoretical and disconnected from actual classroom practise, specifically in early childhood art education. The authors developed a new curriculum framework based on "learning by doing" principles that better prepares future teachers through hands-on experiences. Early childhood educators and teacher trainers will find practical strategies for bridging the theory-practise gap and developing more confident, capable teachers.

Exploring initial teacher education student teachers' beliefs about reflective practise using a modified reflective practise questionnaire View study ↗

23 citations

Dr Stephen Day et al. (2022)

This study examined what student teachers actually think about reflection and whether they truly understand its value for professional growth. The researchers developed and tested a reliable questionnaire to measure reflective capacity, revealing important insights about how future teachers view self-examination of their practise. Teacher educators can use these findings to better support student teachers in developing genuine reflective skills rather than just going through the motions.

Encouraging Reflective Practise: A Pathway to Effective Teaching and Professional Growth View study ↗

Feruza Masharipova (2025)

This research demonstrates how English language teachers can use structured reflection, particularly Gibbs' Reflective Cycle, to systematically improve their teaching effectiveness and professional development. The study shows how integrating reflection into lesson planning and classroom activities helps educators gain deeper insights into their teaching methods. English teachers at any career stage will discover practical ways to critically assess and enhance their instructional strategies through purposeful reflection.

Reflective Critical Analysis of a Case Study in ESL Learning Context: Challenges and Issues for Adult Asylum Seeker and Refugee English Learners in Wales, UK View study ↗

Xuanmeng Lyu (2025)

This teacher-researcher spent ten months working with adult asylum seekers and refugees learning English, using reflective analysis to understand the unique challenges these learners face. The study reveals how factors like social identity, motivation, and language bias significantly impact learning outcomes in this vulnerable population. ESL teachers working with refugee and immigrant communities will gain valuable insights into culturally responsive teaching practices and reflective self-examination when working with marginalized learners.

Work through all six stages of Gibbs' cycle to reflect on a recent teaching experience. Your reflection builds as you progress.

Download this free Metacognition, Planning, Monitoring & Self-Regulation resource pack for your classroom and staff room. Includes printable posters, desk cards, and CPD materials.

These studies examine how structured reflective practice, including Gibbs' reflective cycle, supports professional development, teacher learning and pupil metacognition in educational settings.

Facilitating the Professional Learning of New Teachers Through Critical Reflection on Practice During Mentoring Meetings View study ↗

146 citations

Harrison, Lawson & Wortley (2005)

This highly cited study demonstrates that structured reflective frameworks during mentoring sessions significantly accelerate new teachers' professional development. The specific questioning techniques used by mentors to guide reflection through description, feelings and evaluation mirror the stages of Gibbs' cycle and provide a practical template for any mentoring conversation.

One Teacher's Reflective Journey and the Evolution of a Lesson: Systematic Reflection as a Catalyst for Adaptive Expertise View study ↗

29 citations

Hayden, Moore-Russo & Marino (2013)

This longitudinal case study tracks how one teacher's systematic use of reflective cycles transformed a lesson across multiple iterations. The detailed documentation of how each reflective stage, from description through action planning, led to specific pedagogical improvements makes a compelling case for embedding Gibbs' framework into routine teaching practice.

Continuous Collaborative Reflection Sessions in a Professional Learning Community View study ↗

15 citations

Woolway, Msimanga & Lelliott (2019)

This study shows how collaborative reflection using structured frameworks develops teacher reflective capacity over time. The research found that teachers who reflected together using a staged cycle produced richer analysis and more actionable insights than those reflecting alone, suggesting that Gibbs' framework works best as a shared professional tool.

Experiential Learning Theory as a Guide for Experiential Educators in Higher Education View study ↗

494 citations

Kolb & Kolb (2022)

This landmark paper connects Gibbs' reflective cycle to Kolb's experiential learning theory, showing how reflection on concrete experience drives abstract conceptualisation and active experimentation. The integrated framework helps teachers understand reflection not as an add-on activity but as the mechanism through which experience becomes learning.

Disney, Dewey, and the Death of Experience in Education View study ↗

31 citations

Roberts (2006)

Roberts argues that modern education has stripped experience of its reflective component, creating passive consumption rather than active learning. The provocative analysis reinforces why structured reflection, such as Gibbs' cycle, remains necessary for transforming classroom activities from mere experiences into genuine learning opportunities.

Gibbs' Reflective Cycle is a popular model for reflection, acting as a structured method to enable individuals to think systematically about the experiences they had during a specific situation.

Gibbs' Reflective Cycle is a widely used and accepted model of reflection. Developed by Graham Gibbs in 1988 at Oxford Polytechnic, now Oxford Brookes University, this reflective cycle framework is widely used within various fields such as healthcare, education, and management to improve professional and personal development. It has since become an integral part of reflective practise, allowing individuals to reflect on their experiences in a structured way.

The cycle consists of six stages which must be completed in order for the reflection to have a defined purpose. The first stage is to describe the experience. This is followed by reflecting on the feelings felt during the experience, identifying what knowledge was gained from it, analysing any decisions made in relation to it and considering how this could have been done differently.

The final stage of the cycle is to come up with a plan for how to approach similar experiences in future.

Gibbs' Reflective Cycle encourages individuals to consider their own experiences in a more in-depth and analytical way, helping them to identify how they can improve their practise in the future

A survey from the British Journal of Midwifery found that 63% of healthcare professionals regularly used Gibbs' Reflective Cycle as a tool for reflection.

"Reflection is a critical component of professional nursing practise and a strategy for learning through practise. This integrative review synthesizes the literature on nursing students' reflection on their clinical experiences.", Beverly J. Bowers, RN, PhD

The six stages are: Description (what happened), Feelings (what were you thinking and feeling), Evaluation (what was good and bad), Analysis (what sense can you make of it), Conclusion (what else could you have done), and Action Plan (what will you do next time). Each stage builds on the previous one to create a thorough reflection process that moves from observation to concrete improvement strategies.

The Gibbs reflective cycle consists of six distinct stages: Description, Feelings, Evaluation, Analysis, Conclusion, and Action Plan. Each stage prompts the individual to examine their experiences through questions designed to incite deep and critical reflection. For instance, in the 'Description' stage, one might ask: "What happened?". This questioning method encourages a thorough understanding of both the event and the individual's responses to it (AlOtaibi et al., 2023).

To illustrate, let's consider a student nurse reflecting on an interaction with a patient. In the 'Description' stage, the student might describe the patient's condition, their communication with the patient, and the outcome of their interaction. Following this, they would move on to the 'Feelings' stage, where they might express how they felt during the interaction, perhaps feeling confident, anxious, or uncertain.

The 'Evaluation' stage would involve the student reflecting on their interaction with the patient, considering how they could have done things differently and what went well. In the 'Analysis' stage, the student might consider the wider implications of their actions and how this impacted on the patient's experience.

Finally, in the 'Conclusion' stage, the student would summarise their reflections by noting what they have learned from the experience. They would then set an 'Action Plan' for how they will apply this newfound knowledge in their future practise.

Gibbs' Reflective Cycle is a useful tool for nurses to utilise in order to reflect on their past experiences and improve their practise. By using reflective questions, nurses can actively engage in reflection and identify areas for improvement (Mahmoud & Bawaneh, 2025).

Teachers commonly use Gibbs' cycle to reflect on challenging lessons, student behaviour incidents, or new teaching strategies they've tried. For example, after a difficult class, a teacher might describe what happened, identify their frustration, evaluate what worked and didn't work, analyse why students were disengaged, conclude what alternative approaches could help, and create an action plan for the next lesson. This systematic approach transforms negative experiences into learning opportunities (McDonald et al., 2022).

The Gibbs Reflective Cycle, a model of reflection, can be a effective method for learning and personal development across various vocations. Here are five fictional examples:

These examples illustrate how the Gibbs Reflective Cycle can help learning and reflection across different vocations, leading to personal and professional growth (Tree & Worsfold, 2026).

The Description stage forms the foundation of effective reflection. Rather than rushing to judgment, this stage requires you to capture the objective facts of what occurred. Think of this as creating a factual record that separates observable events from your interpretations or emotional responses.

When documenting the description stage, use these targeted prompts to ensure thorough coverage:

Context: Wednesday morning, period 2 (9:45-10:45am), Week 4 of autumn term. Year 7 mixed-ability class of 28 students learning to add fractions with different denominators.

Description: I introduced the topic using a visual fraction wall displayed on the interactive whiteboard. Students were seated in mixed-ability groups of four. After a 10-minute whole-class introduction demonstrating the method with three worked examples, I distributed differentiated worksheets, green for foundation, amber for core, orange for extension.

Within five minutes, I noticed seven students with green worksheets had stopped working. When I approached the first group, two students said they "didn't get it" but couldn't articulate what they didn't understand. I re-explained the method to this group, then moved to check on other students.

By mid-lesson, twelve students were off-task, some chatting, others simply staring at blank worksheets. The students with orange worksheets worked independently and completed the tasks. The lesson ended with only approximately 40% of students completing even the first section of their worksheets.

The Feelings stage requires honest examination of your emotional response throughout the experience. This isn't about dwelling on emotions, but rather recognising how they influenced your decisions and perceptions. Emotional awareness directly impacts teaching effectiveness and professional resilience.

Initial feelings: I started the lesson feeling reasonably confident. I'd taught this topic successfully to Year 8 last year and spent time on Sunday evening creating differentiated resources. I felt well-prepared and organised.

During the lesson: My confidence shifted to concern around the 15-minute mark when I realised the green group wasn't progressing. This concern turned to frustration when I noticed students chatting instead of attempting the work. I felt professionally inadequate, questioning whether my explanation had been clear enough.

There was also a mounting sense of pressure as I tried to support struggling students whilst keeping the rest of the class on task. I noticed my patience wearing thin, particularly when one student asked me to "explain it again" for the third time.

After the lesson: I left feeling deflated and somewhat defensive. When a colleague asked how my morning went, I found myself blaming the class rather than examining my practise. That evening, I felt genuine worry about the students who didn't grasp the concept and frustration with myself for not reaching them effectively.

The Evaluation stage moves beyond emotional response to objective assessment. This stage requires balanced analysis of both strengths and weaknesses in your practise. The goal isn't to focus solely on what went wrong, but to identify specific elements that worked alongside those that didn't.

What worked well:

What didn't work well:

The Analysis stage is where most teachers struggle, yet it's the most critical for genuine professional development. This stage requires you to move beyond describing what happened to understanding why it happened. You should draw on pedagogical knowledge, educational research, and teaching theory to interpret the experience.

The Analysis stage gains depth when teachers draw on named theoretical frameworks rather than working from intuition alone. Three frameworks are particularly useful for classroom situations.

Belbin Team Roles (Belbin, 1981) help teachers analyse group work or collaborative incidents. If a group project stalled, consider whether the configuration lacked a co-ordinator to manage task distribution, or whether two dominant "shaper" personalities created conflict. Applying Belbin moves analysis from "the group didn't work" to a specific structural explanation that points towards a concrete remedy.