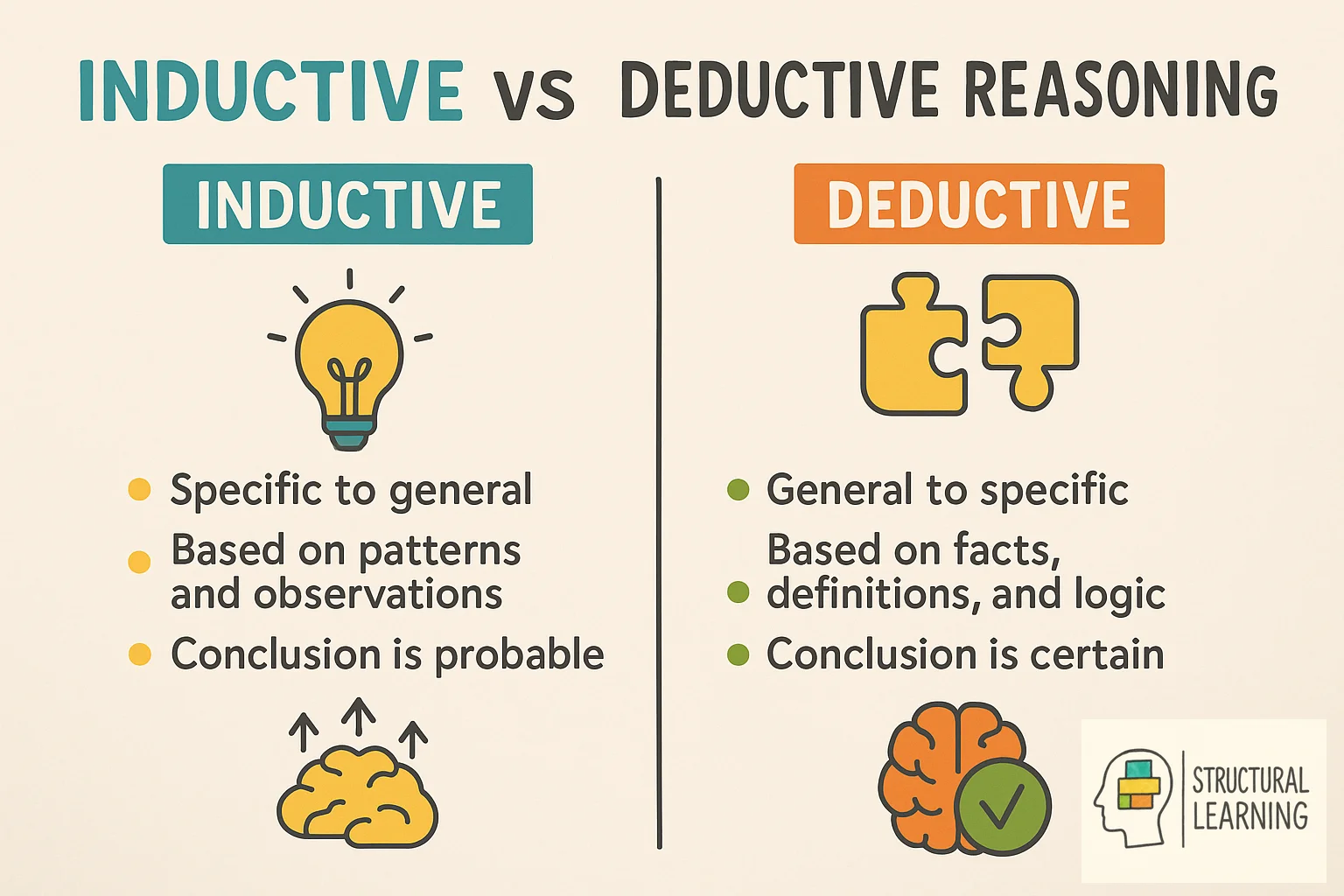

Inductive Reasoning Versus Deductive Reasoning

Master inductive and deductive reasoning to enhance critical thinking in school and workplace settings. Elevate decision-making skills.

Inductive and deductive reasoning are the pillars of logical thought, essential in the critical thinking toolkit that teachers impart to their students. Understanding the nuances of these two forms of reasoning is pivotal in nurturing students' analytical capabilities.

| Aspect | Inductive Reasoning | Deductive Reasoning |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | A bottom-up approach that starts with specific instances and builds toward broader generalizations | A top-down approach that begins with general theories or premises and moves toward specific conclusions |

| Key Feature | Builds arguments piece by piece from observations, focusing on pattern recognition and probability | Provides certainty s through systematic, structured logical reasoning |

| Example | Observing multiple instances of plants growing toward light and concluding that plants need sunlight | Starting with the premise of traveling to a specific city and deducing the best transportation method |

| Classroom Use | Encourages students to spot patterns, form hypotheses, and engage in scientific exploration | Teaches students to evaluate hypothesis validity and understand sound argument structures |

| Best For | Tackling unfamiliar problems, creative exploration, and real-world application of learning | Verification of theories, formal inquiry, and situations requiring certain conclusions |

Inductive reasoning, a bottom-up approach, invites learners to start with specific instances and ascend to broader generalizations. It's a process where the inductive argument is built piece by piece from observations, culminating in a hypothesis. This inductive logic sparks curiosity, propelling students to discern patterns and engage in the thinking skill with vigor.

Contrastingly, deductive reasoning adopts a top-down approach. Here, the argument in question begins with a widely accepted theory or premise, marching steadfastly towards individual, specific conclusions, forming a deductive argument. This form of reasoning teaches students to evaluate the validity of a hypothesis by formative assessment, sharpening their scientific reasoning and understanding of valid argument structures.

In daily classroom practice and engagement, these methods interlace to form a robust framework for discovery and verification. While inductive arguments helps students with the creative freedom to explore and theorize, deductive arguments refine their thought processes, ensuring that their conclusions are sound or revealing the flaws in unsound or invalid arguments.

Introducing students to both approaches equips them with a comprehensive view of problem-solving and decision-making, enriching their educational journey with the rigors of formal and empirical inquiry. This approach particularly benefits sen students when properly structured.

Deductive reasoning is a top-down logical process that starts with a general theory or premise and moves to specific conclusions. It guarantees certainty when the initial premises are true, making it ideal for mathematical proofs and scientific hypothesis testing. Teachers use deductive reasoning when applying established rules or formulas to solve specific problems.

The concept of the Deductive Approach plays a crucial role in providing certainty s. Deduction involves reasoning from general or universal premises to reach specific conclusions. It is often used in everyday scenarios, such as trip planning, where we start with certain premises, such as knowing the destination and the available means of transportation, and then use deductive reasoning to determine the best route or mode of travel. This systematic approach can be enhanced through scaffolding techniques that support student learning progression.

The strength of deductive reasoning lies in its logical certainty. When the premises are true and the logical structure is valid, the conclusion must also be true. This makes deductive reasoning particularly valuable in mathematics, formal logic, and scientific applications where precision is essential.

However, deductive reasoning has limitations that teachers should help students understand. The conclusions are only as reliable as the initial premises. If the general principle or major premise is incorrect, even perfectly logical deductive reasoning will lead to false conclusions. Additionally, deductive reasoning cannot generate genuinely new knowledge about the world - it can only reveal what is already implicit in the premises, making it less suitable for discovery and hypothesis formation.

In educational applications, teachers can strengthen student understanding by presenting both valid and invalid examples of deductive reasoning. For instance, comparing "All birds can fly; penguins are birds; therefore penguins can fly" with "All mammals breathe air; whales are mammals; therefore whales breathe air" helps students recognise how false premises affect conclusions. Encouraging students to question the accuracy of initial premises develops critical thinking skills and prevents blind acceptance of seemingly logical arguments, developing more sophisticated reasoning abilities.

Inductive reasoning works by moving from specific observations to broader generalisations, essentially building understanding from the ground up through pattern recognition. Unlike deductive reasoning, which starts with established premises, inductive reasoning begins with concrete examples and encourages learners to identify underlying rules or principles. For instance, after observing that "all swans I've seen are white," a student might conclude that "all swans are white" through inductive reasoning, though this conclusion remains probabilistic rather than certain.

The cognitive process involves three key stages: observation collection, where students gather specific instances; pattern identification, where they recognise similarities or trends; and generalisation formation, where they propose broader rules. Jerome Bruner's research on discovery learning highlights how this bottom-up approach enhances student engagement and promotes deeper conceptual understanding by allowing learners to construct knowledge actively rather than receive it passively.

In classroom practice, inductive reasoning proves particularly effective for introducing new concepts across subjects. Mathematics teachers might present several examples of quadratic equations before students derive the general formula, whilst science educators can use experimental observations to help students discover scientific laws. This approach encourages critical thinking and scientific inquiry, though educators should emphasise that inductive conclusions require testing and may need revision when new evidence emerges.

The fundamental distinction between inductive and deductive reasoning lies in their directional flow: deductive reasoning moves from general principles to specific conclusions, whilst inductive reasoning travels from specific observations to broader generalisations. Deductive arguments, when constructed properly, guarantee their conclusions if the premises are true, making them invaluable for mathematical proofs and logical demonstrations. Conversely, inductive reasoning produces conclusions that are probable rather than certain, as evidenced in scientific hypothesis formation and pattern recognition tasks.

Understanding these differences proves crucial for classroom application. Deductive reasoning excels in structured subjects where established rules apply, such as geometry or grammar instruction, where students can apply known principles to solve specific problems. Inductive reasoning flourishes in exploratory learning environments, encouraging students to observe data patterns, conduct experiments, and formulate theories. Research by cognitive scientist Keith Holyoak demonstrates that students develop stronger analytical skills when they explicitly recognise which reasoning type suits different academic contexts.

Effective educators integrate both approaches strategically: beginning lessons with inductive exploration to build student curiosity, then transitioning to deductive applications to reinforce understanding. This dual approach supports diverse learning preferences whilst developing comprehensive reasoning capabilities essential for critical thinking across all subject areas.

Effective teaching of inductive and deductive reasoning requires deliberate integration across multiple subjects rather than isolated lessons. In mathematics, teachers can demonstrate deductive reasoning through geometric proofs, where students apply established theorems to reach specific conclusions. Conversely, pattern recognition activities in number sequences encourage inductive thinking as students observe examples to formulate general rules. Science lessons naturally incorporate both approaches: students use inductive reasoning when analysing experimental data to form hypotheses, then apply deductive reasoning to test predictions based on scientific theories.

John Sweller's cognitive load theory demonstrates the importance of scaffolding these complex thinking processes. Teachers should begin with explicit instruction about the differences between reasoning types, using simple, concrete examples before progressing to abstract applications. Literature classes offer excellent opportunities for both reasoning styles: students can deduce character motivations from textual evidence or inductively develop themes by examining patterns across multiple texts.

Practical classroom strategies include thinking aloud protocols, where teachers verbalise their reasoning processes, and structured graphic organisers that help students track premises and conclusions. Regular reflection activities asking students to identify whether they used inductive or deductive approaches strengthens their metacognitive awareness and develops more sophisticated logical thinking skills across all subject areas.

In science education, students regularly encounter both reasoning types through hands-on learning. When pupils observe that metal objects expand when heated across multiple experiments, they're using inductive reasoning to form a general principle from specific observations. Conversely, when they apply Newton's laws to predict an object's motion before conducting an experiment, they're employing deductive reasoning by moving from established premises to specific conclusions.

Mathematics offers particularly clear examples for classroom demonstration. Students use inductive reasoning when they examine number patterns (2, 4, 6, 8..) to conclude that even numbers increase by two, whilst deductive reasoning appears when they apply the Pythagorean theorem to solve for an unknown side length. Literature analysis similarly combines both approaches: students might inductively identify themes by examining character actions throughout a text, then deductively support their interpretation using specific textual evidence.

For effective classroom practice, present students with everyday scenarios that naturally incorporate both reasoning types. When investigating why certain plants thrive in the school garden, pupils can inductively observe patterns in soil conditions and sunlight, then deductively test their hypotheses. This dual approach, supported by cognitive research showing improved retention through varied reasoning experiences, helps students develop robust logical thinking skills applicable across all subjects.

One of the most persistent misconceptions students hold is the belief that stronger premises automatically lead to stronger conclusions. Many learners incorrectly assume that compelling evidence in inductive reasoning guarantees certainty, failing to grasp that even well-supported inductive conclusions remain probabilistic. Conversely, students often dismiss deductive arguments with seemingly weak premises, not recognising that logical validity depends entirely on structural relationships rather than the truth or appeal of individual statements.

Another common error involves confusing strength with validity. Students frequently conflate these distinct evaluative criteria, applying validity judgements to inductive arguments or assessing deductive reasoning for empirical strength. This confusion stems partly from everyday language usage, where "valid" often means "good" or "reasonable". Research by cognitive scientists demonstrates that students benefit from explicit instruction distinguishing these technical terms from their colloquial counterparts.

Teachers can address these misconceptions through structured comparison exercises that present parallel examples of both reasoning types. Providing students with argument evaluation frameworks, complete with specific criteria for each reasoning form, helps establish clearer conceptual boundaries. Regular practice identifying argument types before evaluation prevents students from applying inappropriate assessment standards and builds more sophisticated logical thinking skills.