Understanding Cultural Capital in the Classroom: Bourdieu’s Framework for Equity

Discover how Bourdieu's cultural capital theory helps teachers identify hidden barriers and create equitable classrooms where all students thrive.

Discover how Bourdieu's cultural capital theory helps teachers identify hidden barriers and create equitable classrooms where all students thrive.

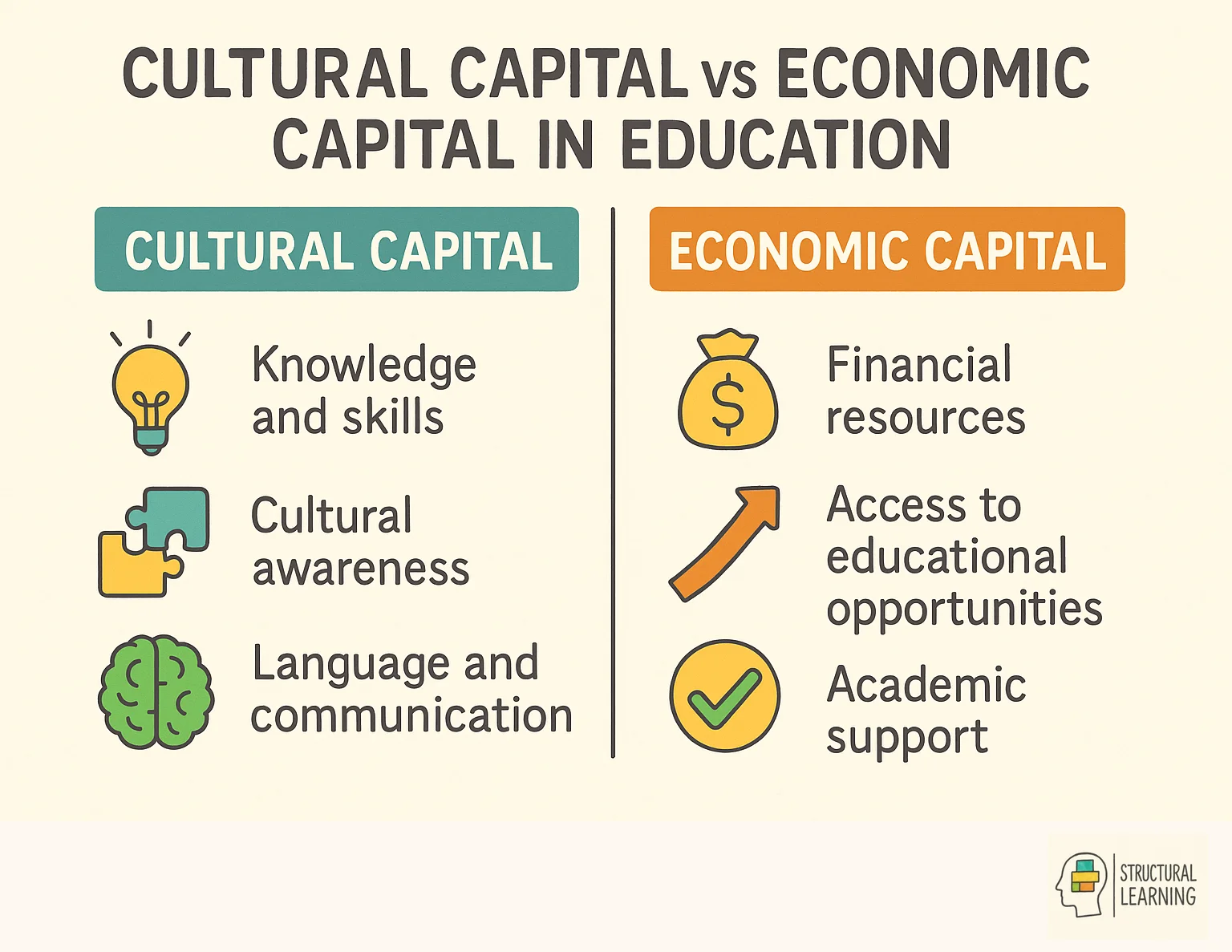

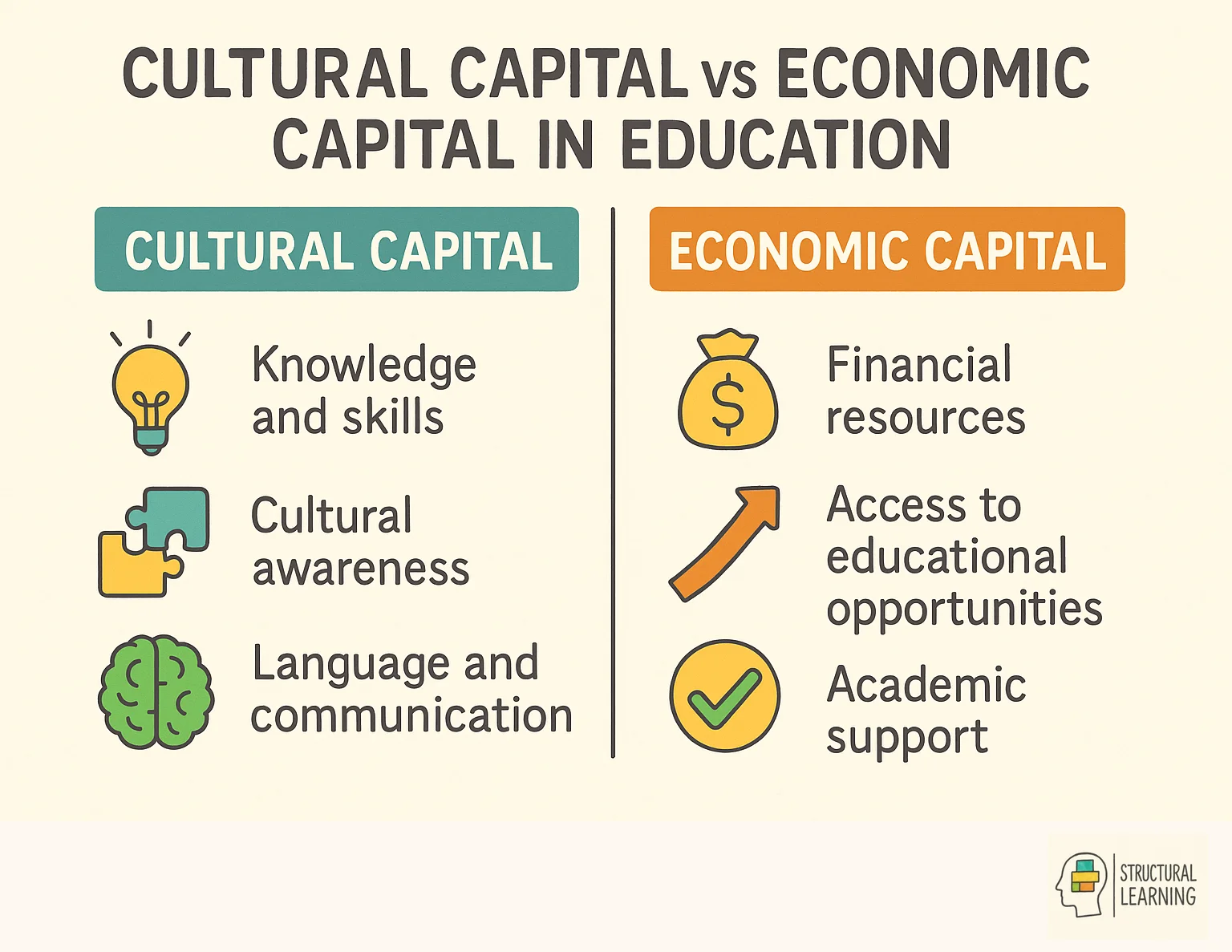

Pierre Bourdieu's theory of cultural capital reveals why students with identical classroom resources achieve different outcomes. Cultural capital, the knowledge, skills, education, qualifications, and cultural experiences individuals possess, determines how effectively students navigate educational systems. This framework helps educators identify how teaching practices either reinforce or challenge social inequalities, enabling better support for all learners.

Social Capital: Networks, relationships, and social connections that open doors to mentorship, information, and opportunities.

Cultural Capital: Knowledge, skills, education, qualifications, and cultural experiences valued by dominant social groups.

Bourdieu introduced habitus (deeply ingrained dispositions shaped by upbringing) and field (social arenas with distinct rules and power dynamics) to explain how individuals navigate social spaces. The amount of capital an individual possesses determines their ability to move between different habitus and fields successfully.

Economic capital, financial assets and material resources, influences access to quality schooling, private tutoring, extracurricular activities, and educational materials. Students from high-income families attend prestigious private schools, access personal tutors, and participate in enriching activities such as music lessons, sports clubs, or international travel. These experiences enhance learning and provide advantages in classroom discussions and assessments.

Two students preparing for university entrance exams illustrate this disparity. Student A accesses paid coaching, study guides, and a quiet study space at home. Student B shares a room with siblings, has limited internet access, and relies solely on school-provided resources. Economic capital directly affects their examination success and future employment opportunities. Essay planning strategies and AI tools for teachers can help mitigate some disadvantages by improving instructional efficiency.

Social capital, the relationships and networks providing support and opportunities, manifests in educational settings through parental involvement, mentorship, or connections to influential individuals. Economic capital enables individuals to accumulate more social capital by networking across wider social situations.

A student whose parents are teachers benefits from guidance on navigating the school system, understanding academic expectations, and accessing resources. Their social network provides insider knowledge others lack. A student participating in community organisations or youth clubs develops leadership skills and gains access to scholarships or internships through those connections. Developing communication abilities through structured classroom dialogue helps all students build their own social capital networks.

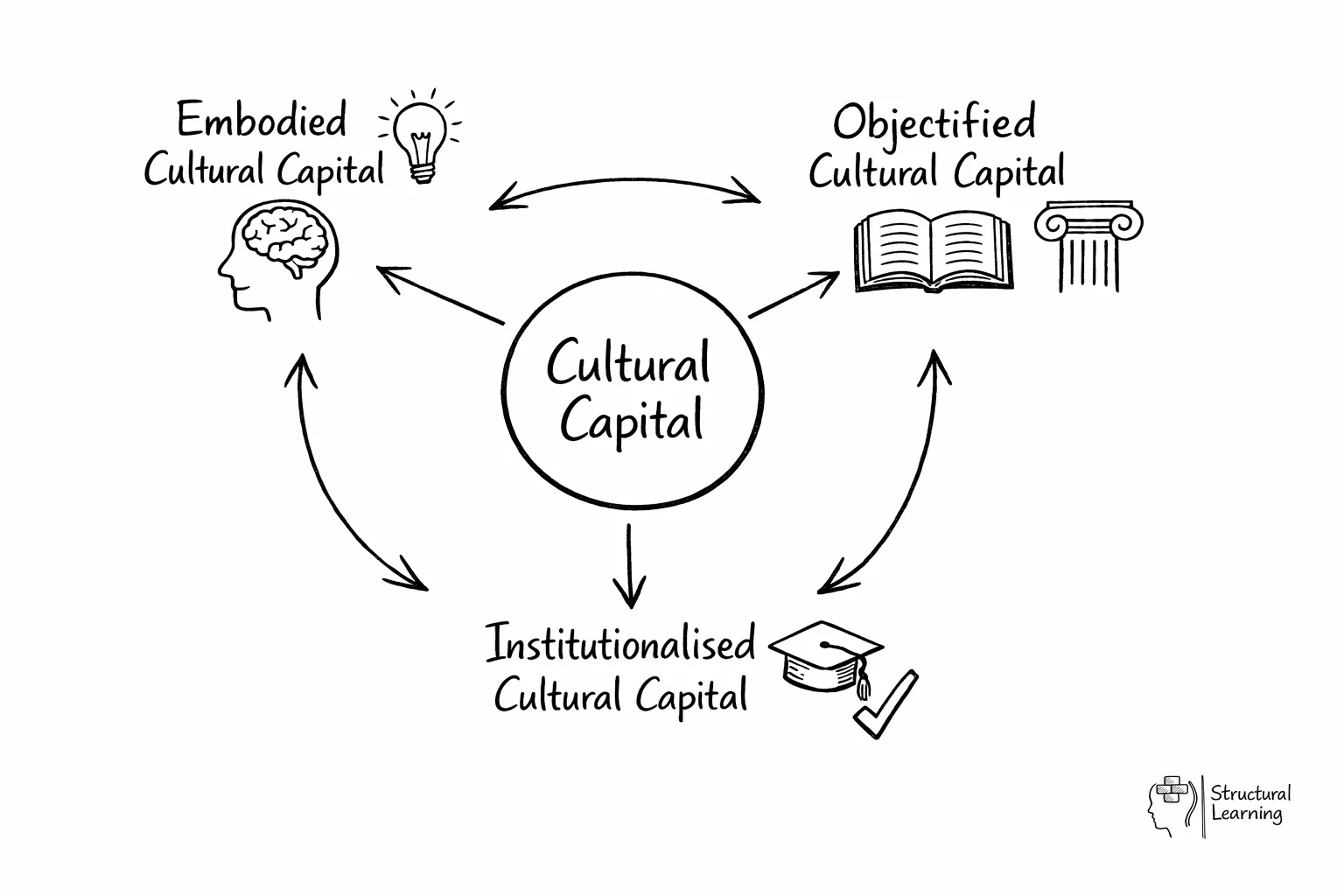

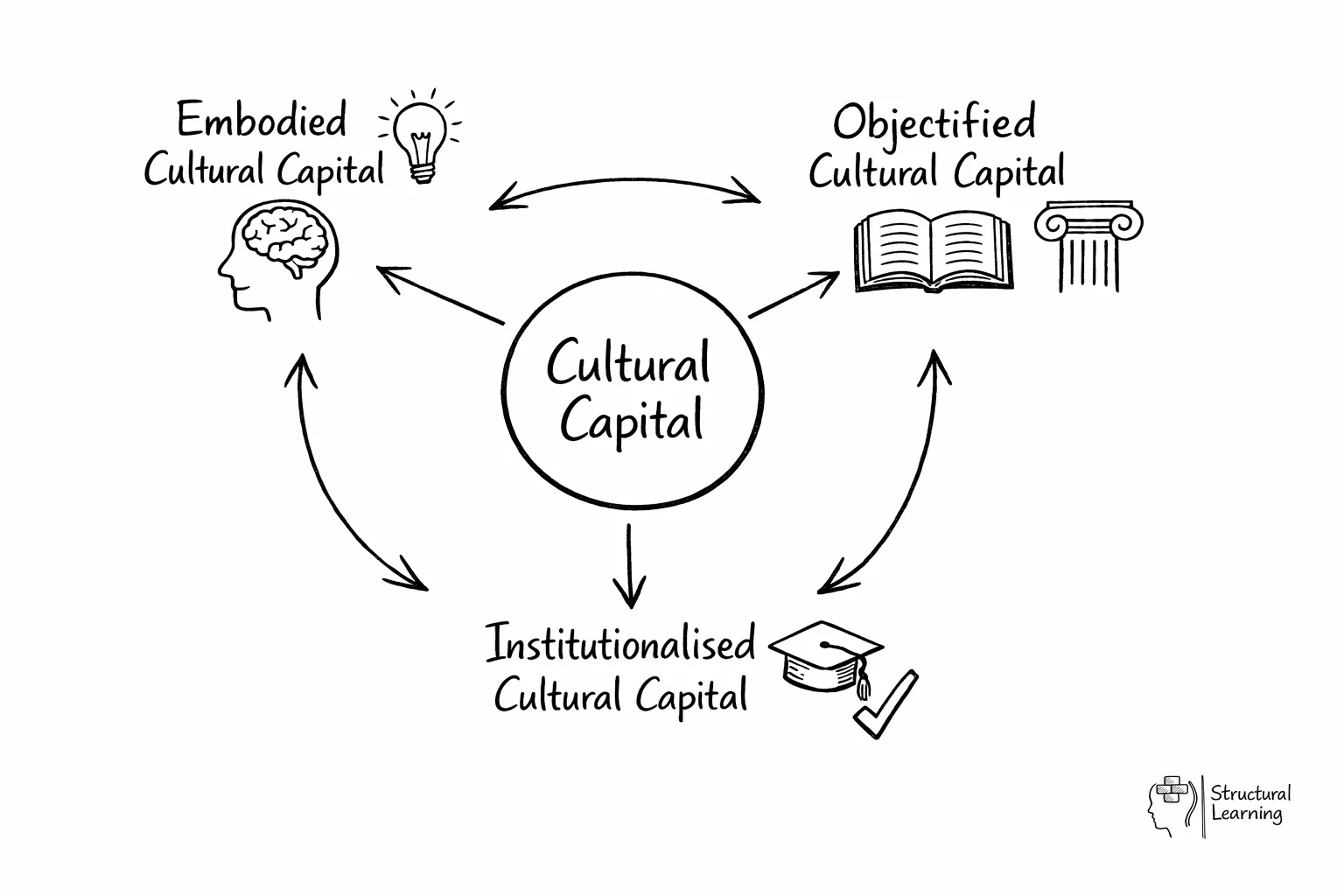

Cultural capital, the most complex and influential form in educational contexts, impacts social capital accumulation and is determined by economic capital. Bourdieu categorised cultural capital into three forms:

Embodied Cultural Capital: Personal traits including language proficiency, confidence, mannerisms, and dispositions acquired through socialisation. Cultural habitus determines these traits, but exposure to different social contexts or specific language input (such as hearing different dialects or registers) can modify them.

Objectified Cultural Capital: Physical objects including books, musical instruments, artworks, or educational technology. Access to these resources supports development of embodied and institutionalised cultural capital.

Institutionalised Cultural Capital: Formal qualifications, credentials, and academic titles that confer legitimacy and social recognition.

A student who speaks with confidence using academic register may be perceived as more capable, even when their understanding matches peers who express themselves differently. This perception influences teacher expectations and grading practices. Behavioural reinforcement theories explain how these perceptions become self-fulfiling prophecies.

A child raised in a household where classical music is played and discussed engages more easily with music curriculum content. Their familiarity with cultural references provides an advantage. Within schools, providing access to wide vocabulary ranges, dictionaries, and glossaries repre sen ts a simple method to enhance vocabulary and negate disadvantage. Chomsky's language acquisition theories emphasise the importance of rich linguistic environments.

Basil Bernstein's theory of language codes connects to this analysis. Bernstein argued that schools favour the "elaborated code" used by middle-class students, characterised by explicit, structured, context-independent language. Working-class students often use a "restricted code", more context-dependent, implicit, and less valued in academic settings. This linguistic bias disadvantages students whose speech patterns differ from the dominant norm through classroom discourse expectations.

Cultural capital was formally introduced into the Education Inspection Framework in September 2019. Ofsted defines it as: "the essential knowledge that pupils need to be educated citizens, introducing them to the best that has been thought and said."

It is worth noting that Ofsted's operational definition differs from Bourdieu's original sociological concept. While Bourdieu described cultural capital as a mechanism of social reproduction explaining how dominant groups maintain advantages, Ofsted uses the term prescriptively, focusing on what schools should provide to all pupils.

2024-2025 Changes:

Habitus refers to the deeply ingrained habits, skills, and dispositions students develop from their social background that shape how they perceive and respond to educational environments. Students whose habitus aligns with school culturenaturally understand unwritten rules, communication styles, and behavioural expectations, giving them significant advantages. Teachers can support all students by explicitly teaching these hidden expectations and validating diverse ways of thinking and behaving.

Habitus, Bourdieu's concept describing deeply ingrained habits, dispositions, habits of mind, and ways of thinking shaped by upbringing and social context, influences how individ uals perceive the world and act within it. Habitus is predetermined at birth and cannot be chosen by the individual born into that habitus. While habitus from economically disadvantaged backgrounds may limit educational aspirations, it simultaneously brings diverse social and cultural experiences to the classroom that enrich learning communities.

A student raised in a home where reading is encouraged arrives at school with rich vocabulary and confidence in literacy tasks. Their habitus aligns with school environment expectations, enabling them to thrive. A student from a migrant background brings multilingual skills and diverse cultural perspectives, but when schools fail to recognise or value these assets, the student feels alienated or misunderstood and struggles within the school system. The IB Learner Profile provides a framework for valuing diverse cultural perspectives.

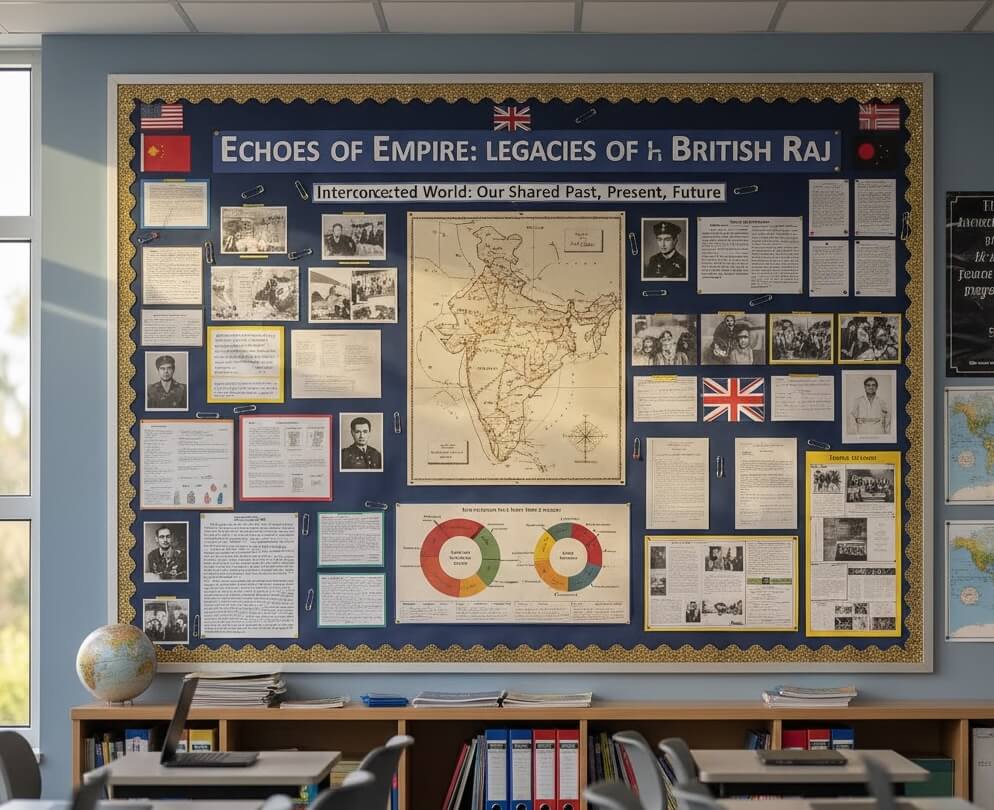

Fields, social arenas including schools, universities, and professional domains, contain individuals competing for status, recognition, and resources. Each field has distinct rules and power dynamics. In classrooms, these dynamics manifest in subtle ways: who gets to speak, whose ideas receive validation, and whose experiences appear in the curriculum. Decolonisation of curriculum content addresses these power imbalances. Implementing behaviour management strategies, organising classroom spaces thoughtfully, applying evidence-based instructional principles, and considering cognitive loadall support equitable practise.

A student who challenges a teacher's authority may appear transformative, but their behaviour could stem from a habitus shaped by different cultural norms around respect and communication within their home culture or the subculture of specific academic fields.

Symbolic capital represents the recognition, honour, and prestige that certain forms of knowledge, behaviour, or achievement receive within educational settings. Students who speak in academic language, display confidence in class discussions, or demonstrate familiarity with high culture often receive more positive recognition from teachers. This recognition translates into better grades, more opportunities, and increased self-confidence, creating a cycle of advantage.

Symbolic capital, the prestige, honour, and recognition individuals receive, accumulates in schools through academic success, leadership roles, awards, or peer popularity. Teachers recognise each student's individual merits to avoid a standardised education system, as described by Ken Robinson and Frank Coffield, ensuring that individual success, however modest, receives recognition and reward. Teachers remain mindful that some students reject praise or recognition for fear of peer labelling or ostracism. Teachers therefore consider how praise is delivered and received by each individual student.

A student who wins a poetry competition gains symbolic capital that boosts their confidence and peer status. This recognition motivates further engagement and achievement. A student who consistently receives teacher praise may be perceived as a role model, even when their academic performance is average. The symbolic capital they hold influences how others perceive and treat them. Digital assessment platforms like Educake can provide diverse recognition opportunities beyond traditional academic metrics.

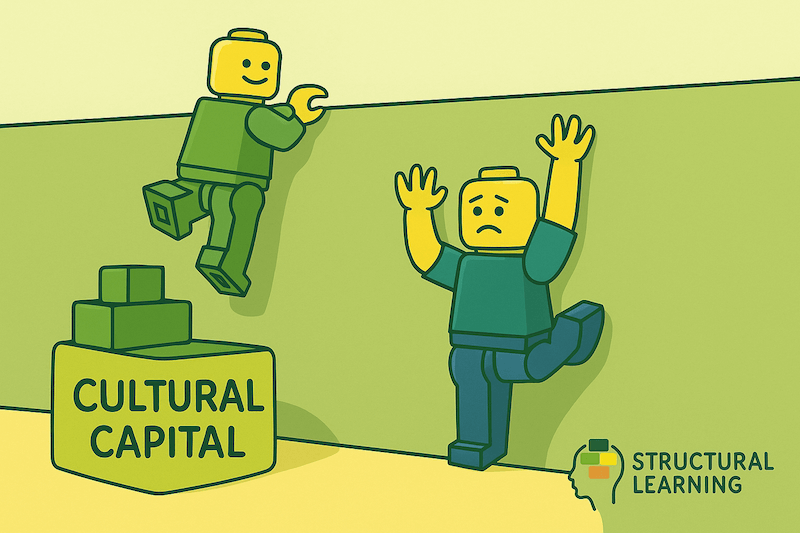

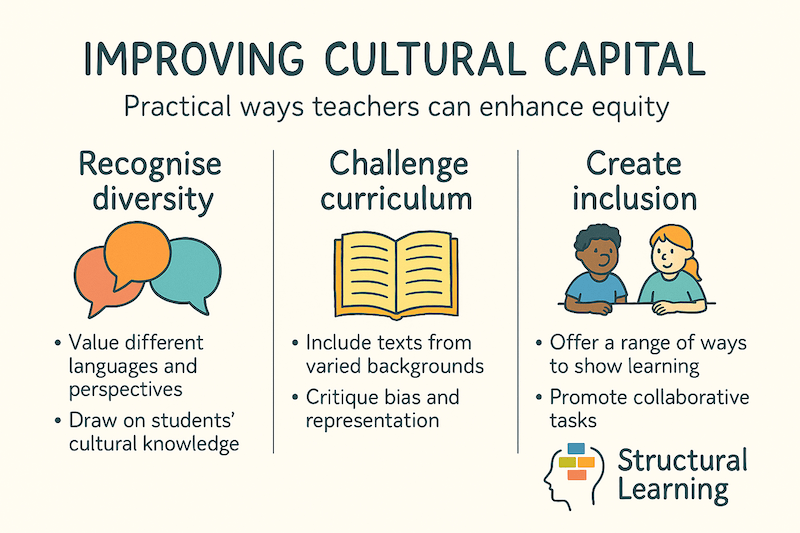

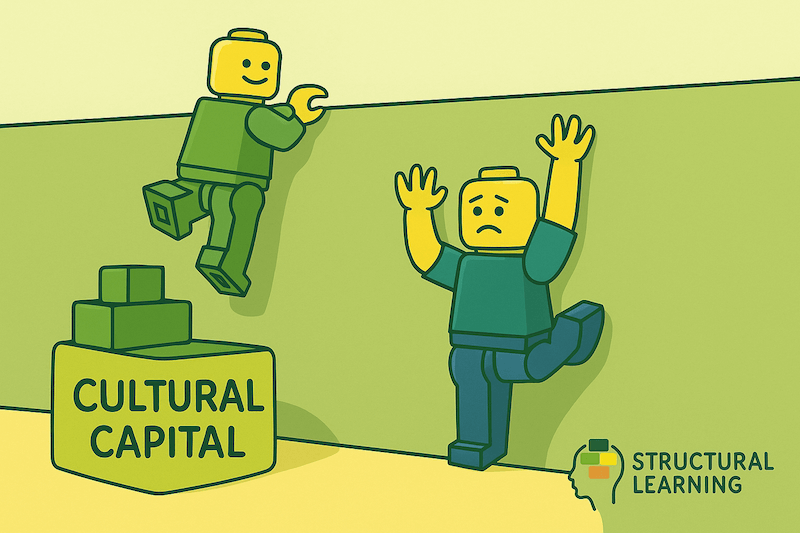

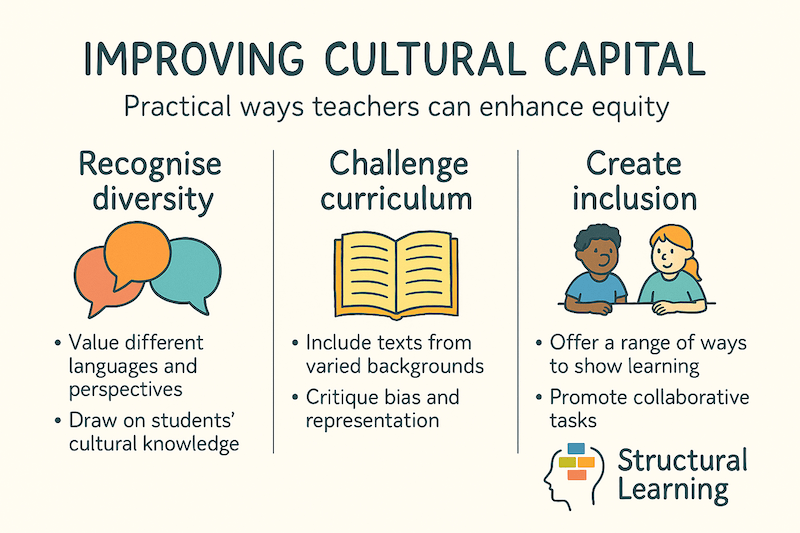

Schools reproduce social inequality by rewarding the cultural capital of middle-class students while failing to recognise or value the cultural assets of working-class students. This happens through curriculum choices, assessment methods, language expectations, and teaching styles that assume certain cultural knowledge. Teachers can interrupt this cycle by explicitly teaching academic codes, valuing diverse cultural experiences, and creating multiple pathways for students to demonstrate learning.

Bourdieu's social reproduction theory argues that schools reinforce existing social inequalities by valuing the cultural capital of dominant groups. This reproduction occurs through multiple mechanisms:

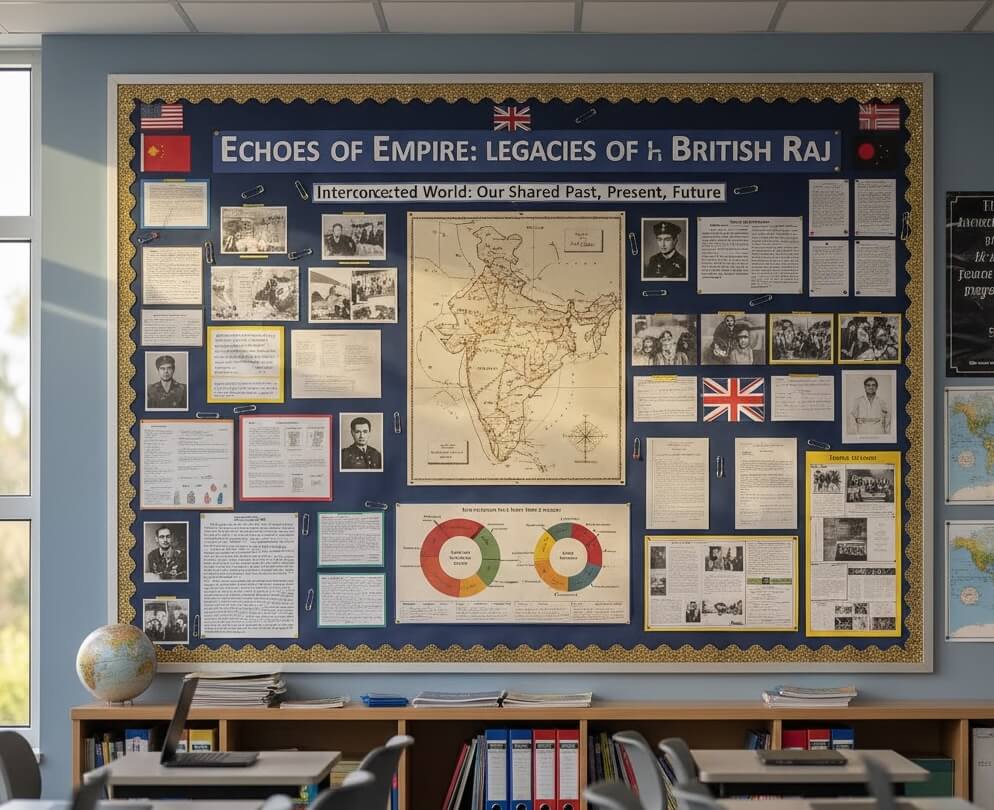

Curriculum Choices: A curriculum focusing primarily on Western literature and history marginalises students from diverse backgrounds. Presenting alternative curricula can be challenging, but supporting students to question presented content develops critical consciousness and analytical thinking.

Assessment Methods: Standardised tests favour students familiar with the language register and format used. Research from the National Research Council and National Academy of Sciences emphasises transparent assessment practise that reduces cultural bias.

Classroom Expectations: Behaviour norms and participation styles reflect middle-class values, disadvantaging students with different cultural experiences. Forming classroom rules collectively with students and teachers creates ownership of classroom norms and values that reflect students' cultural and social backgrounds. Understanding leadership theories helps teachers facilitate this collaborative process.

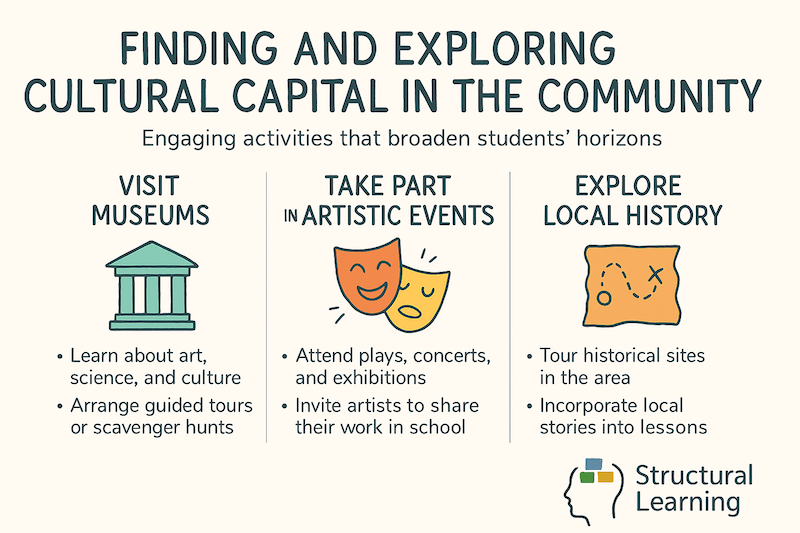

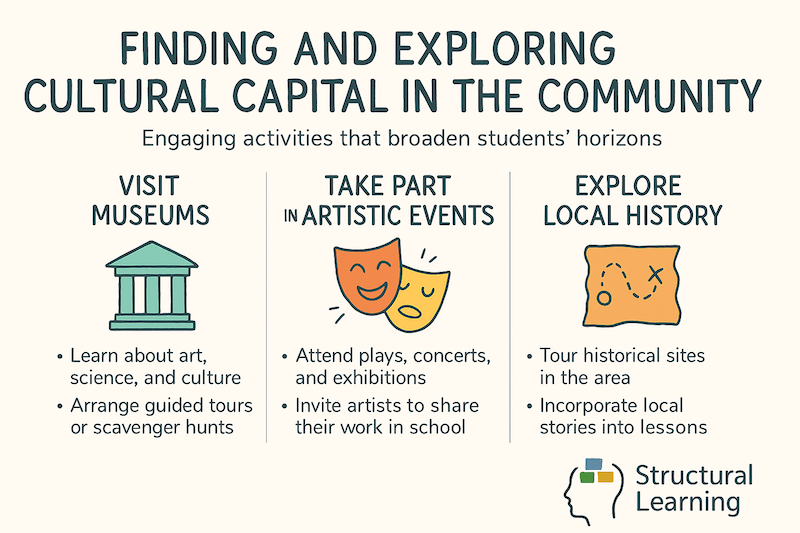

A student who has never visited a museum struggles with a history assignment assuming familiarity with artefacts and exhibitions. Their lack of objectified cultural capital affects their ability to engage with the task. Systematic curriculum design builds foundational knowledge progressively.

A student who speaks a dialect or non-standard form of English may be corrected or penalised, even though their communication is effective within their community. Studies published in journals such as the Journal of Curriculum Studies and Science Education highlight these linguistic biases embedded in educational systems.

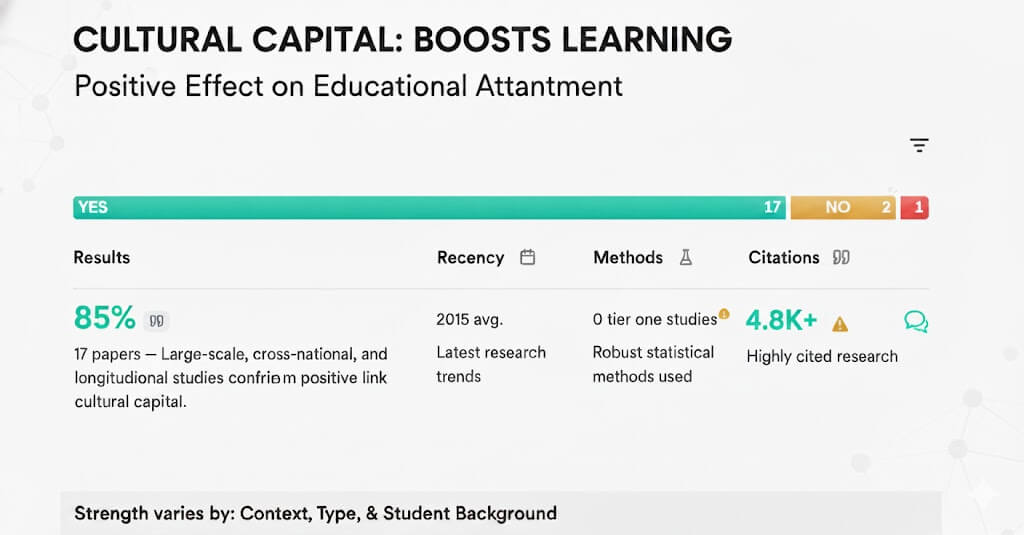

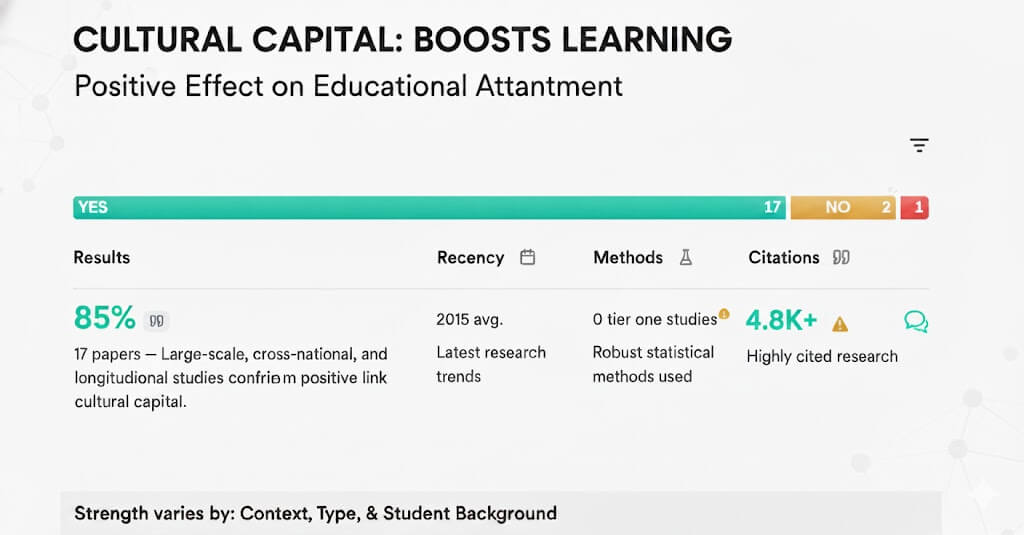

While qualitative research supports Bourdieu's ideas, large-scale quantitative studies produce mixed results. His framework serves as a reflective tool for understanding student needs rather than a deterministic model.

Teachers consciously celebrate students' lived experiences, languages, and cultural knowledge through specific practices:

In a literature class, allowing students to analyse texts from their own cultural backgrounds creates engagement and deepens understanding. Platforms like Hegarty Maths demonstrate how technology can provide multiple entry points to learning.

Educators advocate for inclusive curriculum that reflects multiple perspectives and histories through concrete actions:

Including African, Asian, and Indigenous authors in English literature courses broadens students' horizons and validates their cultural heritage. Structured thinking tools help students analyse diverse perspectives systematically.

Inclusive classrooms ensure all students feel seen, heard, and valued through evidence-based strategies:

Offering oral presentations, visual projects, and written assignments as assessment options allows students to showcase their strengths. Homeschooling approaches often excel at this personalisation, offering lessons for mainstream classrooms.

Teachers encourage critical thinking by promoting dialogue about power, privilege, and identity. This helps students understand the social forces shaping their experiences and helps them to challenge injustice.

Discussing media representations of different social groups helps students recognise stereotypes and develop media literacy. Question generation strategies promote deeper inquiry into social structures and power relations.

Thinkers including Henry Giroux and Paulo Freire support this approach. Freire's concept of critical pedagogy, education as a tool for liberation, encourages students to question and transform the world around them rather than passively accept dominant narratives.

Understanding cultural capital helps teachers recognise that achievement gaps often stem from cultural mismatches rather than ability differences. This awareness enables educators to design more inclusive teaching practices that explicitly teach academic expectations while valuing students' diverse cultural backgrounds. By addressing cultural capital disparities, teachers can create more equitable classrooms where all students have genuine opportunities to succeed.

Understanding cultural capital helps teachers look beyond surface-level behaviours and academic performance. Bourdieu's framework encourages educators to ask: What invisible barriers might this student be facing? What cultural assets do they bring that the system fails to recognise? By applying this lens, teachers become more empathetic, inclusive, and effective educators.

Education extends beyond content delivery, it shapes a more just and equitable society. When teachers recognise the diverse forms of capital students bring, they create classrooms where everyone has the opportunity to thrive. This recognition requires ongoing reflection, professional development, and commitment to challenging educational practices that perpetuate social reproduction.

Key resources include Bourdieu's 'Reproduction in Education, Society and Culture' for theoretical foundations and contemporary works that translate his ideas into classroom strategies. Practical guides often focus on culturally responsive teaching, funds of knowledge approaches, and explicit instruction of academic discourse. Many education journals publish case studies showing how teachers successfully apply these concepts to support disadvantaged students.

If you're ready to explore Bourdieu's capital theory in greater depth, these five key studies offer insight into how cultural capital, social class, and educational systems shape social mobility and cultural reproduction. Each explores how cultural knowledge and institutionalised capital influence social distinction, symbolic violence, and the reproduction of social norms across societies.

1. Huang Hai-gan, The Equity in Higher Education under Bourdieu's Theory of Cultural Capital (2008)

Examines how differences in embodied cultural capital and social assets create inequity in China's educational system, showing how social classes reproduce privilege through institutionalised cultural capital and cultural resources.

2. Truong Thi Hong Thuy, Effects of Cultural Capital on Children's Educational Success: An Empirical Study of Vietnam Under the Shadow of Bourdieu's Cultural Reproduction Theory (2020)

Demonstrates how children's embodied cultural capital affects educational success, revealing how teachers' perceptions and social relationships reinforce class-based inequality and restrict social mobility.

3. I. Košutić, The Role of Cultural Capital in Higher Education Access and Institutional Choice (2017)

Shows how embodied and institutionalised cultural capital predict educational choices in Croatia, linking social distinction and family background to educational aspirations within the social sciences.

4. Michael Tzanakis, Bourdieu's Social Reproduction Thesis and The Role of Cultural Capital in Educational Attainment: A Critical Review of Key Empirical Studies (2011)

Critically reviews empirical evidence for cultural reproduction, questioning the universality of Bourdieu's modeland how cultural knowledge and social norms perpetuate class inequality in education.

5. Elisabeth Hultqvist & Ida Lidegran, The Use of ' Cultural Capital' in Sociology of Education in Sweden (2020)Explores how meritocratic ideals mask symbolic violence within Sweden's educational.

Essential readings include Bourdieu's 'The Forms of Capital' (1986) which outlines his capital framework, and 'Reproduction in Education, Society and Culture' (1977) which explains how schools perpetuate inequality. Contemporary applications appear in works by Diane Reay on working-class education and Annette Lareau's research on how parenting styles create different cultural capital. These texts provide both theoretical understanding and practical insights for educators.

Cultural capital refers to the knowledge, skills, qualifications, and cultural experiences that individuals acquire through their upbringing and social environment, which help them navigate educational systems effectively. Unlike economic capital (money and resources) or natural intelligence, cultural capital includes things like understanding academic language codes, familiarity with cultural references in textbooks, and knowing how to interact confidently with teachers because these behaviours were modelled at home.

Teachers can observe whether students struggle with academic language codes (like distinguishing between 'analyse' and 'describe'), lack familiarity with cultural references in textbooks, or seem hesitant to engage confidently with authority figures. Students with less cultural capital may express ideas using different language patterns or seem disengaged with content that assumes certain background knowledge, even when their actual understanding matches their peers.

Schools can provide access to wide vocabulary ranges, dictionaries, and glossaries to enhance language development for all students. Teachers should recognise and value diverse cultural assets that students bring from their own backgrounds, rather than only privileging middle-class cultural codes. Creating rich linguistic environments and using structured classroom dialogue helps students develop communication abilities and build their own cultural capital.

Bourdieu's theory reveals that schools unconsciously favour middle-class cultural codes through language expectations, cultural references, and interaction patterns that some students learn at home whilst others do not. Working-class students may use more context-dependent language patterns that are less valued in academic settings, creating invisible barriers to achievement that exist independently of economic resources.

Schools typically favour the 'elaborated code' used by middle-class students, which features explicit, structured, context-independent language that aligns with academic expectations. Students who primarily use 'restricted code', which is more context-dependent and implicit, may be perceived as less capable even when their understanding equals their peers, leading to different teacher expectations and potentially affecting assessment outcomes.

Cultural capital can be modified and developed through exposure to different social contexts and specific educational interventions, though it requires intentional effort from schools. Teachers can help students acquire academic language codes, provide access to cultural experiences through curriculum content, and create opportunities for students to build confidence in educational interactions. However, schools must recognise that this process takes time and requires valuing students' existing cultural knowledge alongside developing new forms.

Teachers may unconsciously perceive students who speak with confidence using academic register as more capable, even when their actual understanding matches peers who express themselves differently. These perceptions can become self-fulfiling prophecies that influence expectations, AI-enhanced feedback, and grading practices. Understanding this bias helps teachers focus on actual learning rat her than cultural presentation, ensuring fairer assessment and support for all students.

These peer-reviewed studies provide the research foundation for the strategies discussed in this article:

The effects of schools providing compensatory cultural capital on student reading in the case of Taiwanese students participating in PISA View study ↗

1 citations

This research demonstrates that schools with rich educational resources can effectively compensate for the cultural disadvantages that students from low-income families often face at home. The study found that when schools deliberately provide access to books, learning materials, and cultural experiences that wealthy families typically offer their children, reading achievement gaps can be significantly reduced. This finding offers hope to teachers working in high-poverty schools, showing that intentional school-based interventions can level the playing field for disadvantaged students.

The classroom as a space of resistance. Cooperation, gratitude and collective memory between neuroscience and social science View study ↗

Dévrig Mollès & Marcos Parada-

This interdisciplinary study reveals how traditional education systems often reinforce social inequalities by favouring students who already possess elite cultural knowledge and experiences. The researchers argue that teachers can transform their classrooms into spaces of resistance by developing cooperation, building collective memory, and challenging meritocratic assumptions about student ability. For educators, this research provides a framework for creating more equitable learning environments that value diverse forms of knowledge and experience rather than privileging only dominant cultural forms.

Micro-Ethnography Study: Effect of Home Habitus, and Western Cultural Capital on Foreign Students' Small Group Discussion Experience View study ↗

1 citations

Through detailed observation of international students in American classrooms, this study reveals how students' home cultural backgrounds significantly impact their participation in group discussions and collaborative learning activities. The research shows that international students often struggle not due to lack of intelligence or preparation, but because classroom expectations favour Western communication styles and cultural norms. This insight can help teachers recognise when quiet or hesitant students may actually possess valuable knowledge but need different approaches to share their contributions effectively.

Social Inequality in Religious Education: Examining the Impact of Sex, Socioeconomic Status, and Religious Socialization on Unequal Learning Opportunities View study ↗

4 citations

Alexander Unser (2022)

This research uncovers how students' family background, gender, and prior religious experiences create unequal learning opportunities even within religious education classrooms. The study found that students from higher socioeconomic backgrounds and those with extensive religious socialization at home significantly outperformed their peers, suggesting that assumed shared religious knowledge actually varies dramatically among students. Religious education teachers can use these findings to avoid assumptions about student knowledge and create more inclusive learning experiences that build from diverse starting points.

Magnifying inequality? Home learning environments and social reproduction during school closures in Ireland View study ↗

26 citations

G. Mohan et al. (2021)

This large-scale study of Irish schools during COVID-19 closures reveals how remote learning dramatically widened educational inequalities, with student engagement closely tied to parents' education levels and home resources. Students from families with college-educated parents and reliable technology thrived, while others struggled to participate, creating a two-tier system that reinforced existing disadvantages. The research provides crucial evidence for teachers and policymakers about ensuring equitable access to learning during disruptions, emphasising the need for schools to actively support families who lack educational resources at home.

Pierre Bourdieu's theory of cultural capital reveals why students with identical classroom resources achieve different outcomes. Cultural capital, the knowledge, skills, education, qualifications, and cultural experiences individuals possess, determines how effectively students navigate educational systems. This framework helps educators identify how teaching practices either reinforce or challenge social inequalities, enabling better support for all learners.

Social Capital: Networks, relationships, and social connections that open doors to mentorship, information, and opportunities.

Cultural Capital: Knowledge, skills, education, qualifications, and cultural experiences valued by dominant social groups.

Bourdieu introduced habitus (deeply ingrained dispositions shaped by upbringing) and field (social arenas with distinct rules and power dynamics) to explain how individuals navigate social spaces. The amount of capital an individual possesses determines their ability to move between different habitus and fields successfully.

Economic capital, financial assets and material resources, influences access to quality schooling, private tutoring, extracurricular activities, and educational materials. Students from high-income families attend prestigious private schools, access personal tutors, and participate in enriching activities such as music lessons, sports clubs, or international travel. These experiences enhance learning and provide advantages in classroom discussions and assessments.

Two students preparing for university entrance exams illustrate this disparity. Student A accesses paid coaching, study guides, and a quiet study space at home. Student B shares a room with siblings, has limited internet access, and relies solely on school-provided resources. Economic capital directly affects their examination success and future employment opportunities. Essay planning strategies and AI tools for teachers can help mitigate some disadvantages by improving instructional efficiency.

Social capital, the relationships and networks providing support and opportunities, manifests in educational settings through parental involvement, mentorship, or connections to influential individuals. Economic capital enables individuals to accumulate more social capital by networking across wider social situations.

A student whose parents are teachers benefits from guidance on navigating the school system, understanding academic expectations, and accessing resources. Their social network provides insider knowledge others lack. A student participating in community organisations or youth clubs develops leadership skills and gains access to scholarships or internships through those connections. Developing communication abilities through structured classroom dialogue helps all students build their own social capital networks.

Cultural capital, the most complex and influential form in educational contexts, impacts social capital accumulation and is determined by economic capital. Bourdieu categorised cultural capital into three forms:

Embodied Cultural Capital: Personal traits including language proficiency, confidence, mannerisms, and dispositions acquired through socialisation. Cultural habitus determines these traits, but exposure to different social contexts or specific language input (such as hearing different dialects or registers) can modify them.

Objectified Cultural Capital: Physical objects including books, musical instruments, artworks, or educational technology. Access to these resources supports development of embodied and institutionalised cultural capital.

Institutionalised Cultural Capital: Formal qualifications, credentials, and academic titles that confer legitimacy and social recognition.

A student who speaks with confidence using academic register may be perceived as more capable, even when their understanding matches peers who express themselves differently. This perception influences teacher expectations and grading practices. Behavioural reinforcement theories explain how these perceptions become self-fulfiling prophecies.

A child raised in a household where classical music is played and discussed engages more easily with music curriculum content. Their familiarity with cultural references provides an advantage. Within schools, providing access to wide vocabulary ranges, dictionaries, and glossaries repre sen ts a simple method to enhance vocabulary and negate disadvantage. Chomsky's language acquisition theories emphasise the importance of rich linguistic environments.

Basil Bernstein's theory of language codes connects to this analysis. Bernstein argued that schools favour the "elaborated code" used by middle-class students, characterised by explicit, structured, context-independent language. Working-class students often use a "restricted code", more context-dependent, implicit, and less valued in academic settings. This linguistic bias disadvantages students whose speech patterns differ from the dominant norm through classroom discourse expectations.

Cultural capital was formally introduced into the Education Inspection Framework in September 2019. Ofsted defines it as: "the essential knowledge that pupils need to be educated citizens, introducing them to the best that has been thought and said."

It is worth noting that Ofsted's operational definition differs from Bourdieu's original sociological concept. While Bourdieu described cultural capital as a mechanism of social reproduction explaining how dominant groups maintain advantages, Ofsted uses the term prescriptively, focusing on what schools should provide to all pupils.

2024-2025 Changes:

Habitus refers to the deeply ingrained habits, skills, and dispositions students develop from their social background that shape how they perceive and respond to educational environments. Students whose habitus aligns with school culturenaturally understand unwritten rules, communication styles, and behavioural expectations, giving them significant advantages. Teachers can support all students by explicitly teaching these hidden expectations and validating diverse ways of thinking and behaving.

Habitus, Bourdieu's concept describing deeply ingrained habits, dispositions, habits of mind, and ways of thinking shaped by upbringing and social context, influences how individ uals perceive the world and act within it. Habitus is predetermined at birth and cannot be chosen by the individual born into that habitus. While habitus from economically disadvantaged backgrounds may limit educational aspirations, it simultaneously brings diverse social and cultural experiences to the classroom that enrich learning communities.

A student raised in a home where reading is encouraged arrives at school with rich vocabulary and confidence in literacy tasks. Their habitus aligns with school environment expectations, enabling them to thrive. A student from a migrant background brings multilingual skills and diverse cultural perspectives, but when schools fail to recognise or value these assets, the student feels alienated or misunderstood and struggles within the school system. The IB Learner Profile provides a framework for valuing diverse cultural perspectives.

Fields, social arenas including schools, universities, and professional domains, contain individuals competing for status, recognition, and resources. Each field has distinct rules and power dynamics. In classrooms, these dynamics manifest in subtle ways: who gets to speak, whose ideas receive validation, and whose experiences appear in the curriculum. Decolonisation of curriculum content addresses these power imbalances. Implementing behaviour management strategies, organising classroom spaces thoughtfully, applying evidence-based instructional principles, and considering cognitive loadall support equitable practise.

A student who challenges a teacher's authority may appear transformative, but their behaviour could stem from a habitus shaped by different cultural norms around respect and communication within their home culture or the subculture of specific academic fields.

Symbolic capital represents the recognition, honour, and prestige that certain forms of knowledge, behaviour, or achievement receive within educational settings. Students who speak in academic language, display confidence in class discussions, or demonstrate familiarity with high culture often receive more positive recognition from teachers. This recognition translates into better grades, more opportunities, and increased self-confidence, creating a cycle of advantage.

Symbolic capital, the prestige, honour, and recognition individuals receive, accumulates in schools through academic success, leadership roles, awards, or peer popularity. Teachers recognise each student's individual merits to avoid a standardised education system, as described by Ken Robinson and Frank Coffield, ensuring that individual success, however modest, receives recognition and reward. Teachers remain mindful that some students reject praise or recognition for fear of peer labelling or ostracism. Teachers therefore consider how praise is delivered and received by each individual student.

A student who wins a poetry competition gains symbolic capital that boosts their confidence and peer status. This recognition motivates further engagement and achievement. A student who consistently receives teacher praise may be perceived as a role model, even when their academic performance is average. The symbolic capital they hold influences how others perceive and treat them. Digital assessment platforms like Educake can provide diverse recognition opportunities beyond traditional academic metrics.

Schools reproduce social inequality by rewarding the cultural capital of middle-class students while failing to recognise or value the cultural assets of working-class students. This happens through curriculum choices, assessment methods, language expectations, and teaching styles that assume certain cultural knowledge. Teachers can interrupt this cycle by explicitly teaching academic codes, valuing diverse cultural experiences, and creating multiple pathways for students to demonstrate learning.

Bourdieu's social reproduction theory argues that schools reinforce existing social inequalities by valuing the cultural capital of dominant groups. This reproduction occurs through multiple mechanisms:

Curriculum Choices: A curriculum focusing primarily on Western literature and history marginalises students from diverse backgrounds. Presenting alternative curricula can be challenging, but supporting students to question presented content develops critical consciousness and analytical thinking.

Assessment Methods: Standardised tests favour students familiar with the language register and format used. Research from the National Research Council and National Academy of Sciences emphasises transparent assessment practise that reduces cultural bias.

Classroom Expectations: Behaviour norms and participation styles reflect middle-class values, disadvantaging students with different cultural experiences. Forming classroom rules collectively with students and teachers creates ownership of classroom norms and values that reflect students' cultural and social backgrounds. Understanding leadership theories helps teachers facilitate this collaborative process.

A student who has never visited a museum struggles with a history assignment assuming familiarity with artefacts and exhibitions. Their lack of objectified cultural capital affects their ability to engage with the task. Systematic curriculum design builds foundational knowledge progressively.

A student who speaks a dialect or non-standard form of English may be corrected or penalised, even though their communication is effective within their community. Studies published in journals such as the Journal of Curriculum Studies and Science Education highlight these linguistic biases embedded in educational systems.

While qualitative research supports Bourdieu's ideas, large-scale quantitative studies produce mixed results. His framework serves as a reflective tool for understanding student needs rather than a deterministic model.

Teachers consciously celebrate students' lived experiences, languages, and cultural knowledge through specific practices:

In a literature class, allowing students to analyse texts from their own cultural backgrounds creates engagement and deepens understanding. Platforms like Hegarty Maths demonstrate how technology can provide multiple entry points to learning.

Educators advocate for inclusive curriculum that reflects multiple perspectives and histories through concrete actions:

Including African, Asian, and Indigenous authors in English literature courses broadens students' horizons and validates their cultural heritage. Structured thinking tools help students analyse diverse perspectives systematically.

Inclusive classrooms ensure all students feel seen, heard, and valued through evidence-based strategies:

Offering oral presentations, visual projects, and written assignments as assessment options allows students to showcase their strengths. Homeschooling approaches often excel at this personalisation, offering lessons for mainstream classrooms.

Teachers encourage critical thinking by promoting dialogue about power, privilege, and identity. This helps students understand the social forces shaping their experiences and helps them to challenge injustice.

Discussing media representations of different social groups helps students recognise stereotypes and develop media literacy. Question generation strategies promote deeper inquiry into social structures and power relations.

Thinkers including Henry Giroux and Paulo Freire support this approach. Freire's concept of critical pedagogy, education as a tool for liberation, encourages students to question and transform the world around them rather than passively accept dominant narratives.

Understanding cultural capital helps teachers recognise that achievement gaps often stem from cultural mismatches rather than ability differences. This awareness enables educators to design more inclusive teaching practices that explicitly teach academic expectations while valuing students' diverse cultural backgrounds. By addressing cultural capital disparities, teachers can create more equitable classrooms where all students have genuine opportunities to succeed.

Understanding cultural capital helps teachers look beyond surface-level behaviours and academic performance. Bourdieu's framework encourages educators to ask: What invisible barriers might this student be facing? What cultural assets do they bring that the system fails to recognise? By applying this lens, teachers become more empathetic, inclusive, and effective educators.

Education extends beyond content delivery, it shapes a more just and equitable society. When teachers recognise the diverse forms of capital students bring, they create classrooms where everyone has the opportunity to thrive. This recognition requires ongoing reflection, professional development, and commitment to challenging educational practices that perpetuate social reproduction.

Key resources include Bourdieu's 'Reproduction in Education, Society and Culture' for theoretical foundations and contemporary works that translate his ideas into classroom strategies. Practical guides often focus on culturally responsive teaching, funds of knowledge approaches, and explicit instruction of academic discourse. Many education journals publish case studies showing how teachers successfully apply these concepts to support disadvantaged students.

If you're ready to explore Bourdieu's capital theory in greater depth, these five key studies offer insight into how cultural capital, social class, and educational systems shape social mobility and cultural reproduction. Each explores how cultural knowledge and institutionalised capital influence social distinction, symbolic violence, and the reproduction of social norms across societies.

1. Huang Hai-gan, The Equity in Higher Education under Bourdieu's Theory of Cultural Capital (2008)

Examines how differences in embodied cultural capital and social assets create inequity in China's educational system, showing how social classes reproduce privilege through institutionalised cultural capital and cultural resources.

2. Truong Thi Hong Thuy, Effects of Cultural Capital on Children's Educational Success: An Empirical Study of Vietnam Under the Shadow of Bourdieu's Cultural Reproduction Theory (2020)

Demonstrates how children's embodied cultural capital affects educational success, revealing how teachers' perceptions and social relationships reinforce class-based inequality and restrict social mobility.

3. I. Košutić, The Role of Cultural Capital in Higher Education Access and Institutional Choice (2017)

Shows how embodied and institutionalised cultural capital predict educational choices in Croatia, linking social distinction and family background to educational aspirations within the social sciences.

4. Michael Tzanakis, Bourdieu's Social Reproduction Thesis and The Role of Cultural Capital in Educational Attainment: A Critical Review of Key Empirical Studies (2011)

Critically reviews empirical evidence for cultural reproduction, questioning the universality of Bourdieu's modeland how cultural knowledge and social norms perpetuate class inequality in education.

5. Elisabeth Hultqvist & Ida Lidegran, The Use of ' Cultural Capital' in Sociology of Education in Sweden (2020)Explores how meritocratic ideals mask symbolic violence within Sweden's educational.

Essential readings include Bourdieu's 'The Forms of Capital' (1986) which outlines his capital framework, and 'Reproduction in Education, Society and Culture' (1977) which explains how schools perpetuate inequality. Contemporary applications appear in works by Diane Reay on working-class education and Annette Lareau's research on how parenting styles create different cultural capital. These texts provide both theoretical understanding and practical insights for educators.

Cultural capital refers to the knowledge, skills, qualifications, and cultural experiences that individuals acquire through their upbringing and social environment, which help them navigate educational systems effectively. Unlike economic capital (money and resources) or natural intelligence, cultural capital includes things like understanding academic language codes, familiarity with cultural references in textbooks, and knowing how to interact confidently with teachers because these behaviours were modelled at home.

Teachers can observe whether students struggle with academic language codes (like distinguishing between 'analyse' and 'describe'), lack familiarity with cultural references in textbooks, or seem hesitant to engage confidently with authority figures. Students with less cultural capital may express ideas using different language patterns or seem disengaged with content that assumes certain background knowledge, even when their actual understanding matches their peers.

Schools can provide access to wide vocabulary ranges, dictionaries, and glossaries to enhance language development for all students. Teachers should recognise and value diverse cultural assets that students bring from their own backgrounds, rather than only privileging middle-class cultural codes. Creating rich linguistic environments and using structured classroom dialogue helps students develop communication abilities and build their own cultural capital.

Bourdieu's theory reveals that schools unconsciously favour middle-class cultural codes through language expectations, cultural references, and interaction patterns that some students learn at home whilst others do not. Working-class students may use more context-dependent language patterns that are less valued in academic settings, creating invisible barriers to achievement that exist independently of economic resources.

Schools typically favour the 'elaborated code' used by middle-class students, which features explicit, structured, context-independent language that aligns with academic expectations. Students who primarily use 'restricted code', which is more context-dependent and implicit, may be perceived as less capable even when their understanding equals their peers, leading to different teacher expectations and potentially affecting assessment outcomes.

Cultural capital can be modified and developed through exposure to different social contexts and specific educational interventions, though it requires intentional effort from schools. Teachers can help students acquire academic language codes, provide access to cultural experiences through curriculum content, and create opportunities for students to build confidence in educational interactions. However, schools must recognise that this process takes time and requires valuing students' existing cultural knowledge alongside developing new forms.

Teachers may unconsciously perceive students who speak with confidence using academic register as more capable, even when their actual understanding matches peers who express themselves differently. These perceptions can become self-fulfiling prophecies that influence expectations, AI-enhanced feedback, and grading practices. Understanding this bias helps teachers focus on actual learning rat her than cultural presentation, ensuring fairer assessment and support for all students.

These peer-reviewed studies provide the research foundation for the strategies discussed in this article:

The effects of schools providing compensatory cultural capital on student reading in the case of Taiwanese students participating in PISA View study ↗

1 citations

This research demonstrates that schools with rich educational resources can effectively compensate for the cultural disadvantages that students from low-income families often face at home. The study found that when schools deliberately provide access to books, learning materials, and cultural experiences that wealthy families typically offer their children, reading achievement gaps can be significantly reduced. This finding offers hope to teachers working in high-poverty schools, showing that intentional school-based interventions can level the playing field for disadvantaged students.

The classroom as a space of resistance. Cooperation, gratitude and collective memory between neuroscience and social science View study ↗

Dévrig Mollès & Marcos Parada-

This interdisciplinary study reveals how traditional education systems often reinforce social inequalities by favouring students who already possess elite cultural knowledge and experiences. The researchers argue that teachers can transform their classrooms into spaces of resistance by developing cooperation, building collective memory, and challenging meritocratic assumptions about student ability. For educators, this research provides a framework for creating more equitable learning environments that value diverse forms of knowledge and experience rather than privileging only dominant cultural forms.

Micro-Ethnography Study: Effect of Home Habitus, and Western Cultural Capital on Foreign Students' Small Group Discussion Experience View study ↗

1 citations

Through detailed observation of international students in American classrooms, this study reveals how students' home cultural backgrounds significantly impact their participation in group discussions and collaborative learning activities. The research shows that international students often struggle not due to lack of intelligence or preparation, but because classroom expectations favour Western communication styles and cultural norms. This insight can help teachers recognise when quiet or hesitant students may actually possess valuable knowledge but need different approaches to share their contributions effectively.

Social Inequality in Religious Education: Examining the Impact of Sex, Socioeconomic Status, and Religious Socialization on Unequal Learning Opportunities View study ↗

4 citations

Alexander Unser (2022)

This research uncovers how students' family background, gender, and prior religious experiences create unequal learning opportunities even within religious education classrooms. The study found that students from higher socioeconomic backgrounds and those with extensive religious socialization at home significantly outperformed their peers, suggesting that assumed shared religious knowledge actually varies dramatically among students. Religious education teachers can use these findings to avoid assumptions about student knowledge and create more inclusive learning experiences that build from diverse starting points.

Magnifying inequality? Home learning environments and social reproduction during school closures in Ireland View study ↗

26 citations

G. Mohan et al. (2021)

This large-scale study of Irish schools during COVID-19 closures reveals how remote learning dramatically widened educational inequalities, with student engagement closely tied to parents' education levels and home resources. Students from families with college-educated parents and reliable technology thrived, while others struggled to participate, creating a two-tier system that reinforced existing disadvantages. The research provides crucial evidence for teachers and policymakers about ensuring equitable access to learning during disruptions, emphasising the need for schools to actively support families who lack educational resources at home.

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/understanding-cultural-capital#article","headline":"Understanding Cultural Capital in the Classroom: Bourdieu’s Framework for Equity","description":"Discover how Bourdieu's cultural capital theory helps teachers identify hidden barriers and create equitable classrooms where all students thrive.","datePublished":"2025-11-12T14:33:07.974Z","dateModified":"2026-01-26T10:09:32.212Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/understanding-cultural-capital"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/695125d1d56441e399f30b85_z20l0a.webp","wordCount":3927},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/understanding-cultural-capital#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"Understanding Cultural Capital in the Classroom: Bourdieu’s Framework for Equity","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/understanding-cultural-capital"}]},{"@type":"FAQPage","mainEntity":[{"@type":"Question","name":"Cultural Capital vs Economic Intelligence","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Cultural capital refers to the knowledge, skills, qualifications, and cultural experiences that individuals acquire through their upbringing and social environment, which help them navigate educational systems effectively. Unlike economic capital (money and resources) or natural intelligence, cultural capital includes things like understanding academic language codes, familiarity with cultural references in textbooks, and knowing how to interact confidently with teachers because these behaviours were modelled at home."}},{"@type":"Question","name":"Identifying Cultural Capital Gaps","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Teachers can observe whether students struggle with academic language codes (like distinguishing between 'analyse' and 'describe'), lack familiarity with cultural references in textbooks, or seem hesitant to engage confidently with authority figures. Students with less cultural capital may express ideas using different language patterns or seem disengaged with content that assumes certain background knowledge, even when their actual understanding matches their peers."}},{"@type":"Question","name":"Supporting Students with Limited Capital","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Schools can provide access to wide vocabulary ranges, dictionaries, and glossaries to enhance language development for all students. Teachers should recognise and value diverse cultural assets that students bring from their own backgrounds, rather than only privileging middle-class cultural codes. Creating rich linguistic environments and using structured classroom dialogue helps students develop communication abilities and build their own cultural capital."}},{"@type":"Question","name":"Working-Class Underperformance Despite Equal Funding","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Bourdieu's theory reveals that schools unconsciously favour middle-class cultural codes through language expectations, cultural references, and interaction patterns that some students learn at home whilst others do not. Working-class students may use more context-dependent language patterns that are less valued in academic settings, creating invisible barriers to achievement that exist independently of economic resources."}},{"@type":"Question","name":"How does the concept of 'elaborated code' versus 'restricted code' affect classroom interactions?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Schools typically favour the 'elaborated code' used by middle-class students, which features explicit, structured, context-independent language that aligns with academic expectations. Students who primarily use 'restricted code', which is more context-dependent and implicit, may be perceived as less capable even when their understanding equals their peers, leading to different teacher expectations and potentially affecting assessment outcomes."}},{"@type":"Question","name":"Can cultural capital be developed, or is it fixed based on a student's family background?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Cultural capital can be modified and developed through exposure to different social contexts and specific educational interventions, though it requires intentional effort from schools. Teachers can help students acquire academic language codes, provide access to cultural experiences through curriculum content, and create opportunities for students to build confidence in educational interactions. However, schools must recognise that this process takes time and requires valuing students' existing cultural knowledge alongside developing new forms."}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What role does teacher perception play in reinforcing cultural capital advantages or disadvantages?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Teachers may unconsciously perceive students who speak with confidence using academic register as more capable, even when their actual understanding matches peers who express themselves differently. These perceptions can become self-fulfiling prophecies that influence expectations, AI-enhanced feedback, and grading practices. Understanding this bias helps teachers focus on actual learning rat her than cultural presentation, ensuring fairer assessment and support for all students."}},{"@type":"Question","name":"Further Reading: Key Research Papers","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"These peer-reviewed studies provide the research foundation for the strategies discussed in this article:"}}]}]}