John Dewey's Theory

Explore John Dewey's educational theories & how his ideas on experiential learning & democracy in education shape modern teaching.

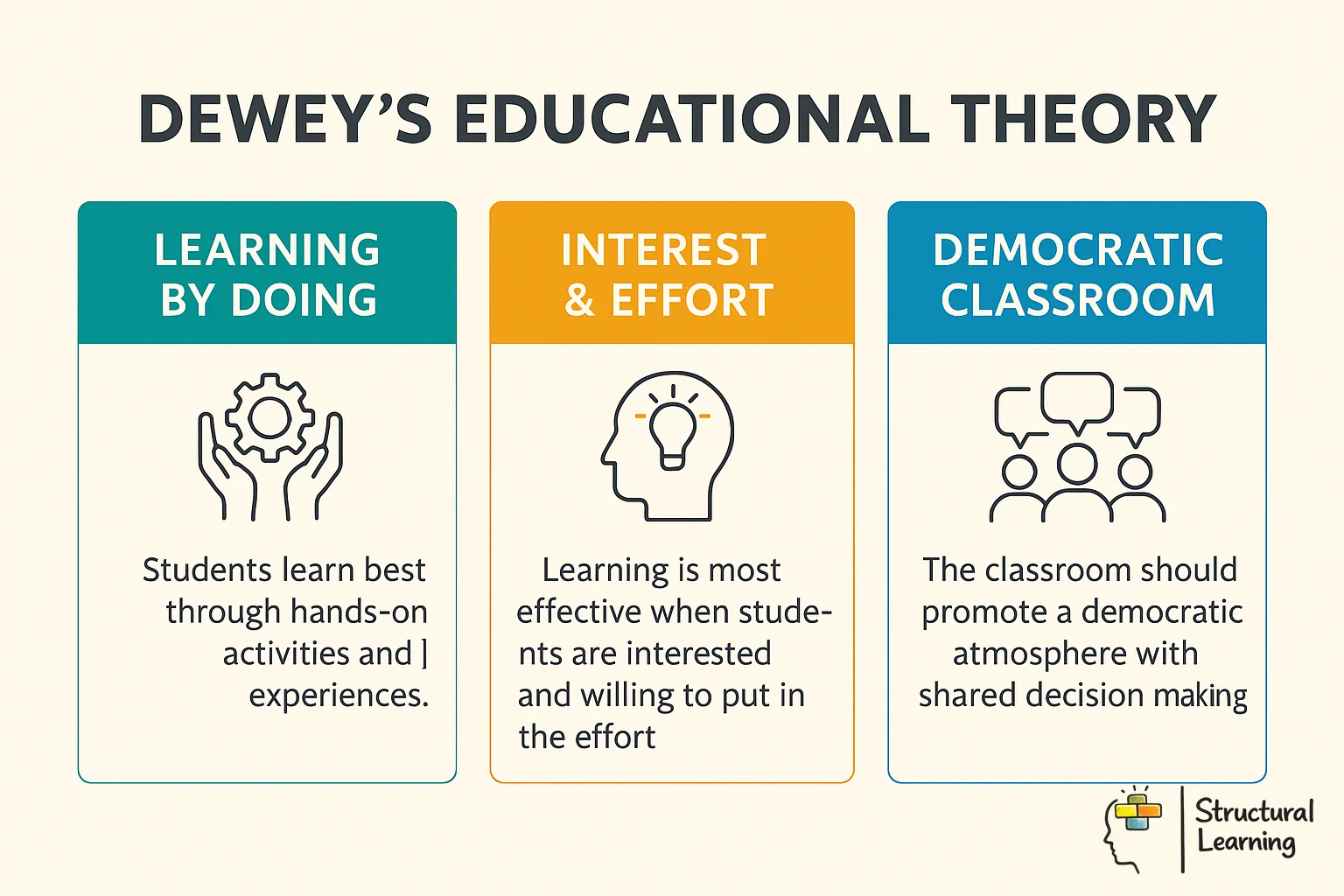

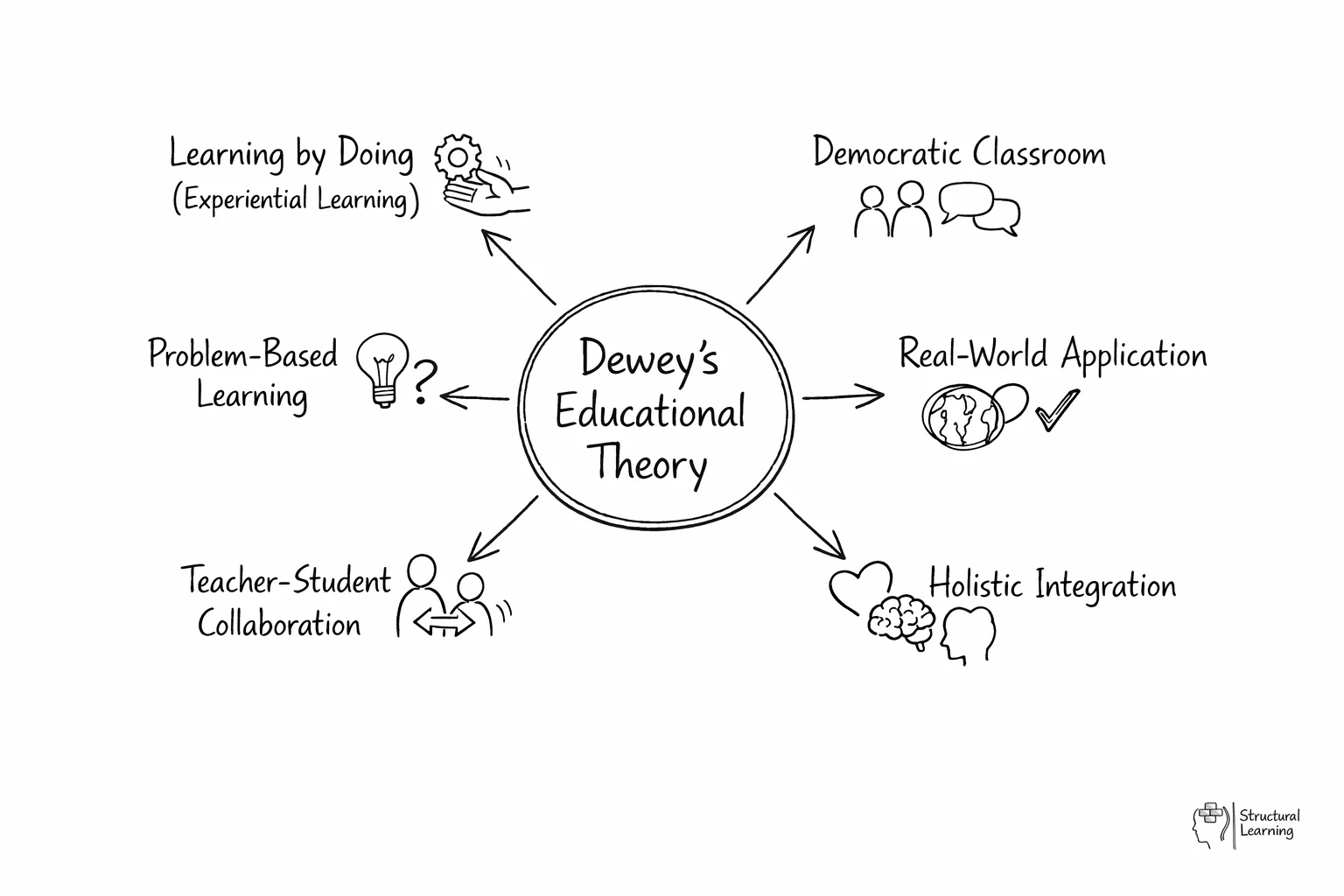

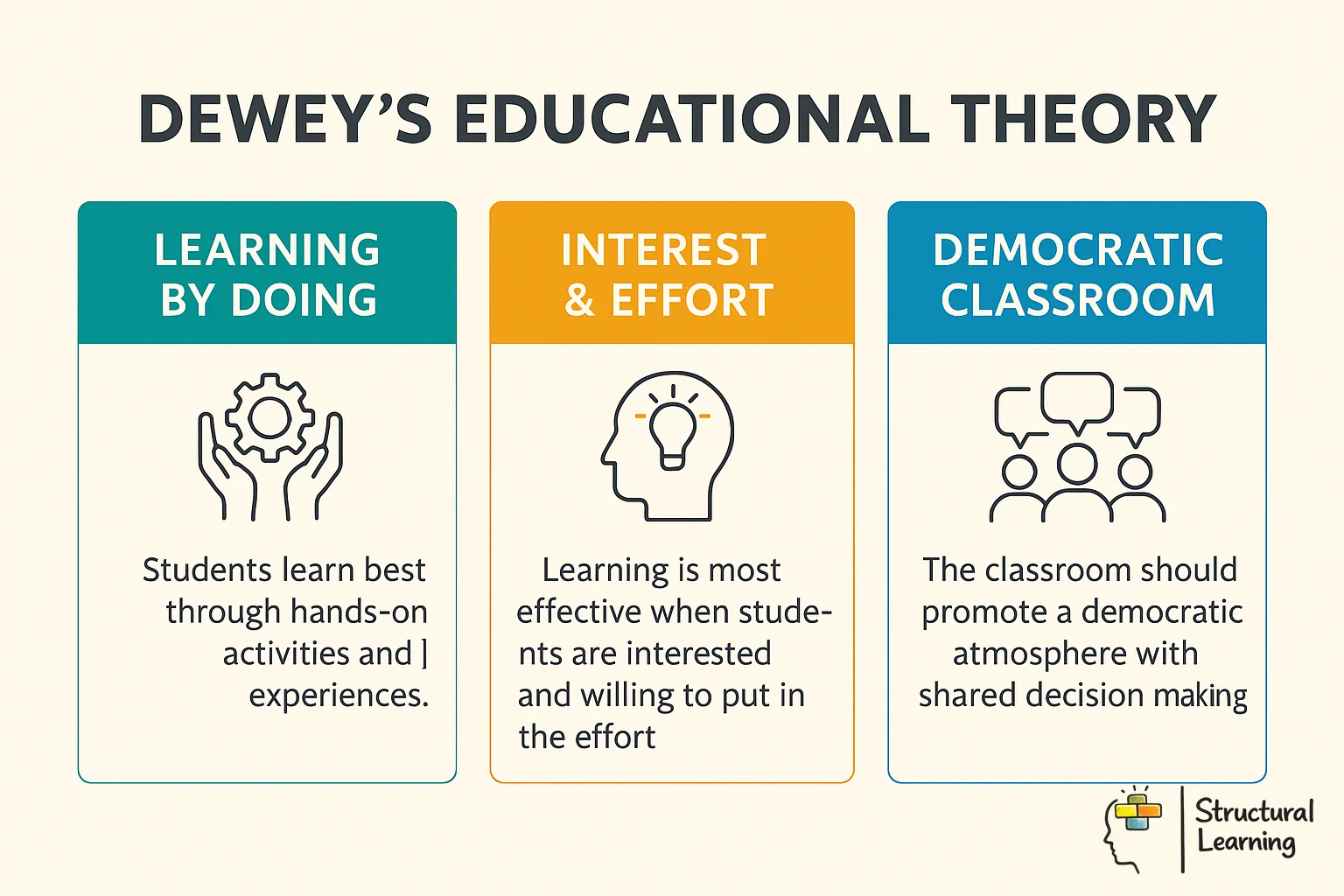

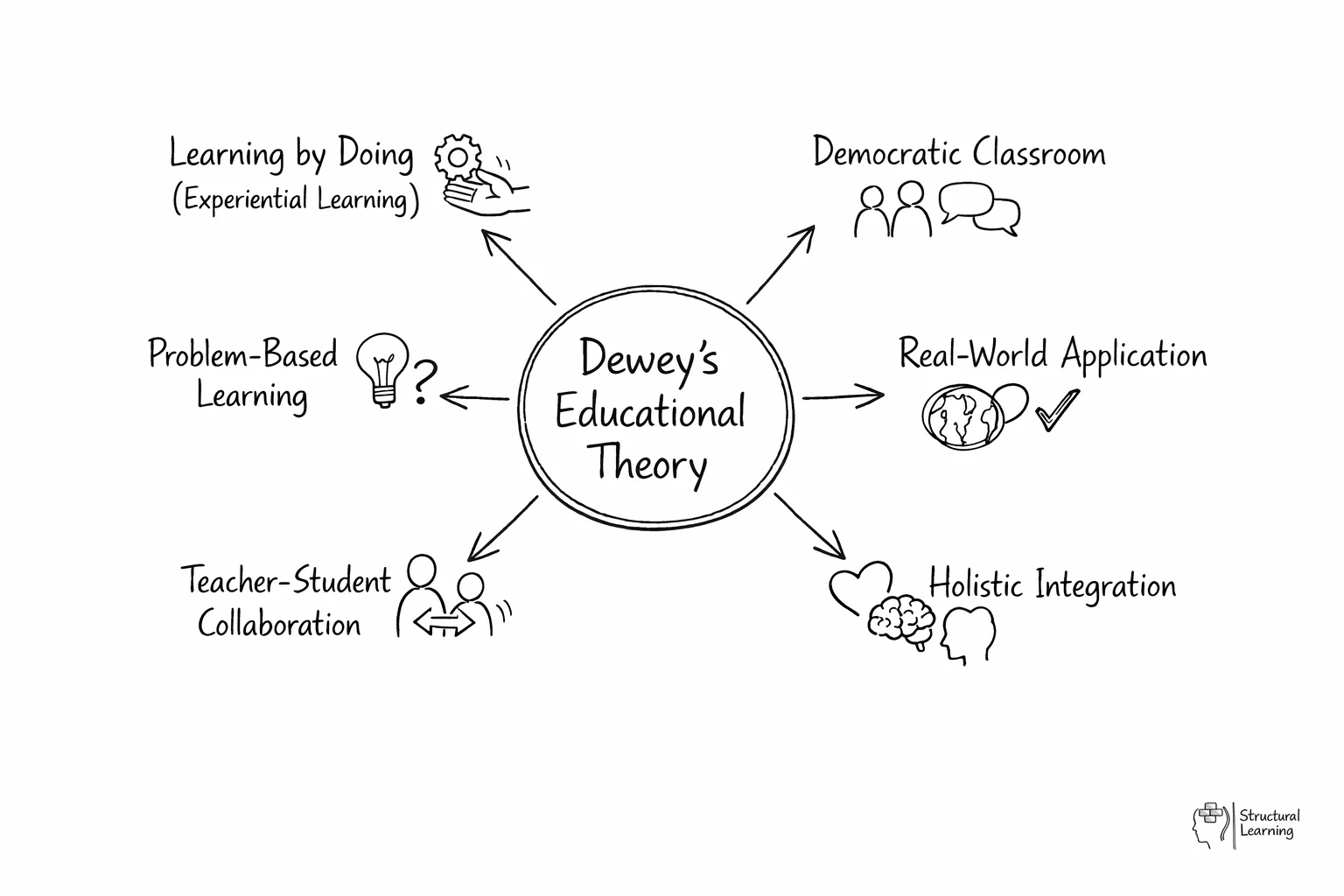

John Dewey's theory revolutionised modern education by proposing that learning should be experiential, democratic, and deeply connected to real-world problem-solving rather than rote memorisation. The American philosopher and educator believed that students learn best through active participation participation and inquiry, where they engage with their environment to construct knowledge collaboratively. His progressive approach emphasised critical thinking, social cooperation, and preparing students for active citizenship in a democratic society. These principles fundamentally challenged traditional teaching methods and continue to shape educational practices worldwide today.

John Dewey was an American philosopher, psychologist and educational reformer widely recognised as one of the most influential thinkers in education.

He developed a unique set of theories about education and social reform, which have since come to be known as the "John Dewey Theory". His effective ideas about education focused on experiential learning, the idea that we can learn best by actively engaging with the material rather than passive listening to lectures or memorizing facts. He also advocated for progressive methods of powerful questioning and dialogue to enable more meaningful exchange during classrooms.

At the core of John Dewey's theory is the notion that human experience should be a guiding light in education and social reform. He argued that all forms of knowledge should be grounded inseparably in practical, real-world experience and that meaningful exploration and learning could only truly take place when students engaged with their material firsthand or through experimentation.

His view was that theoretical information should always be applied practically to ensure an authentic understanding of whatever is being taught.

Education, for Dewey, is not only about gaining theoretical knowledge but also getting practical experience. He viewed education from a complete perspective whereby learning is seen as a continuous process that combines knowledge with life experiences and encourages students to integrate thinking skills with tangible results. This view of education ensures students have significant experiences which are internally meaningful and contribute to their growth as learners.

John Dewey's view on pedagogy was that it should be a complete approach to teaching and learning. He believed in using experiential learning as part of the educational process, whereby students are encouraged to combine their theoretical knowledge with practical experience. Dewey also focused on providing meaningful experiences that contribute to a student's growth as learners. He believed that this type of pedagogy could help shape a well-rounded student who is able to think critically and take tangible skills into the world.

John Dewey's educational theory cannot be fully understood without examining its philosophical foundation: pragmatism. As one of the leading American pragmatist philosophers alongside William James and Charles Sanders Peirce, Dewey developed a philosophy that fundamentally challenged traditional approaches to knowledge and truth.

Pragmatism, at its core, asserts that the truth or meaning of an idea lies in its practical consequences and applications. For Dewey, this meant that knowledge isn't something abstract that exists independently of human experience. Instead, knowledge is created through the process of inquiry and problem-solving in real-world contexts. This philosophical stance had profound implications for education.

Dewey rejected the notion that learning should be about absorbing fixed truths handed down by authorities. Rather, he argued that students should be engaged in active inquiry, testing ideas against experience, and reconstructing their understanding based on outcomes. This process of "learning by doing" wasn't simply a pedagogical technique, it was a direct application of pragmatist philosophy to education.

The pragmatist emphasis on consequences and practical application meant that Dewey viewed education as preparation for participation in democratic society. Knowledge gains its value not from its correspondence to some abstract ideal, but from its usefulness in helping individuals navigate real problems and contribute to social progress. This perspective transformed education from a process of passive transmission to one of active construction and social participation.

Dewey's pragmatism also led him to emphasise the continuity between thought and action. Unlike traditional philosophers who separated mind from body or theory from practise, Dewey saw thinking as a form of doing, a practical activity aimed at solving problems. This integration of thought and action became central to his educational approach, where reflection and experience work together in a continuous cycle of learning.

In the classroom, pragmatism translates to creating learning environments where students engage with genuine problems, test hypotheses through action, and refine their understanding based on results. This approach aligns closely with modern constructivist approaches that emphasise knowledge construction rather than knowledge transmission.

Dewey's learning by doing approach emphasises that students learn best through hands-on experiences and active engagement rather than passive listening. This method involves students directly experimenting with materials, solving real problems, and reflecting on their experiences to construct knowledge. Research shows this approach can increase retention rates by up to 20% compared to traditional lecture methods.

John Dewey and many other pragmatists believe that learners must experience reality without any modifications. From John Dewey's academic viewpoint, students can only learn by adapting to their environment.

John Dewey's idea about the ideal classroom is very much similar to that of the educational psychologists democratic ideals. John Dewey believed that not only students learn, but teachers also learn from the students. When teachers and students, both learn from each other, together they create extra value for themselves.

Many educational psychologists from different countries follow John Dewey's revolutionary education theory to implement the modern educational system. In that era, John Dewey's theory concerning schooling proved to be valid for progressive education and learning.

Progressive education involves the important aspect of learning by doing. John Dewey's theory proposed that individuals' hands-on approach offers the best way of learning.

Due to this, the philosophies of John Dewey have been made a part of the eminent psychologists pragmatic philosophy of education and learning.

John Dewey's educational philosophy emphasises the concept of "Learning by Doing," placing significant emphasis on experiential education. Central to Dewey's ideas are the objects of knowledge and their relationship with the learner. As mentioned, Dewey posits that knowledge is not merely passively received but actively constructed by the learner through experience. This aligns with constructivist approaches to education. The process of learning, thus, becomes a active interaction between the learner and the object of knowledge.

John Dewey's educational theories have implications for problem-based learning.

Dewey's learning by doing approach follows a specific cycle that mirrors the scientific method. First, learners encounter a genuine problem or question that arises from their experience. This isn't an artificial textbook problem, but something that genuinely puzzles or challenges them. Second, they formulate hypotheses or possible solutions based on their existing knowledge and experience.

Third, learners test these hypotheses through active experimentation and hands-on engagement. This might involve conducting experiments, building models, engaging in simulations, or applying concepts to real-world situations. Fourth, they observe and reflect on the outcomes of their actions, noting what worked, what didn't, and why. Finally, learners reconstruct their understanding based on these reflections, incorporating new insights into their knowledge framework.

This cycle doesn't end with a single iteration. Instead, new questions and problems emerge from the solutions found, creating a continuous spiral of learning and growth. This approach shares similarities with collaborative learning strategies that emphasise peer interaction and shared problem-solving.

John Dewey wasn't just a theorist, he was a practitioner who sought to transform American education through the progressive education movement. In 1896, Dewey founded the Laboratory School at the University of Chicago, often called the "Dewey School," which served as a testing ground for his educational theories.

The progressive education movement, which gained momentum in the early 20th century, challenged the authoritarian, teacher-centred model that dominated schools. Traditional classrooms of that era were characterised by rote memorisation, strict discipline, recitation of facts, and a rigid curriculum disconnected from students' lives. Dewey and other progressive educators argued this approach stifled creativity, failed to prepare students for democratic citizenship, and ignored the natural curiosity and interests of children.

Progressive education, inspired by Dewey's theories, emphasised several key principles. First, education should be child-centred rather than subject-centred. This meant starting with students' interests, experiences, and developmental stages, then building curriculum around these foundations. Second, learning should be active and experiential rather than passive. Students should engage in projects, experiments, and real-world problem-solving rather than simply listening to lectures.

Third, the curriculum should be integrated rather than fragmented into isolated subjects. Dewey argued that life doesn't come divided into separate disciplines like mathematics, science, and history. Instead, real problems require drawing on multiple forms of knowledge simultaneously. Fourth, schools should be democratic communities where students learn cooperation, responsibility, and civic participation through practise, not just through textbooks.

The Laboratory School put these principles into practise. Instead of traditional subjects taught in isolation, students engaged in "occupations", activities like cooking, carpentry, and gardening that integrated multiple disciplines naturally. When students built a playhouse, for example, they learned mathematics through measurement, science through understanding materials and structures, history through studying different architectural styles, and social skills through collaborative work.

The progressive education movement spread throughout America and internationally, influencing the development of numerous alternative school models. While the movement faced criticism and backlash, particularly during periods emphasising "back to basics" education, its core principles continue to shape contemporary educational reform efforts, including project-based learning initiatives.

To fully appreciate Dewey's revolutionary approach, understand how it contrasts with traditional educational models that dominated, and in many cases, still dominate, schools worldwide.

Traditional education is rooted in what Dewey called the "spectator theory of knowledge." This view treats knowledge as a collection of established truths that exist independently of learners. Education becomes a process of transmission, where teachers who possess knowledge transfer it to students who don't. The student's role is to receive, memorise, and reproduce this knowledge.

Dewey's approach, by contrast, is based on the idea that knowledge is constructed through experience and inquiry. Students aren't empty vessels to be filled, but active agents who build understanding through interaction with their environment. Knowledge isn't fixed and final, but provisional and subject to revision based on new experiences and evidence.

In traditional classrooms, authority flows from the teacher, who determines what will be learned, when, and how. The curriculum is predetermined, often standardised across entire school systems, and teachers are expected to "cover" specific content regardless of student interest or readiness. Discipline is typically maintained through external controls, rules, punishments, and rewards.

Dewey advocated for a more democratic classroom where teachers serve as guides and facilitators rather than authoritarian figures. While teachers maintain responsibility for structuring learning environments and guiding inquiry, students have genuine voice in determining topics of study, methods of investigation, and ways of demonstrating learning. Discipline emerges naturally from engagement in meaningful work rather than being imposed externally.

Traditional education organises curriculum around academic disciplines that are taught separately and sequentially. Mathematics is taught in one period, science in another, with little connection between them. Content is often abstract and disconnected from students' lives. Assessment focuses on measuring how much content students can recall, typically through tests and examinations.

Dewey's approach integrates subjects around themes, problems, or projects that mirror real-world complexity. Assessment is ongoing and embedded in the learning process itself, focusing on students' ability to apply knowledge to solve genuine problems rather than simply recall facts. This approach connects strongly with modern inquiry-based learning methods.

| Aspect | Traditional Education | Dewey's Progressive Education |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge Source | Fixed body of established truths | Constructed through experience and inquiry |

| Teacher Role | Authority and knowledge transmitter | Facilitator and co-learner |

| Student Role | Passive receiver of information | Active constructor of knowledge |

| Learning Method | Listening, memorisation, recitation | Experimentation, problem-solving, reflection |

| Curriculum Organisation | Separate subjects, sequential lessons | Integrated themes, project-based |

| Motivation | External rewards and punishments | Intrinsic interest and meaningful engagement |

| Assessment | Standardised tests, recall of facts | Authentic tasks, application of knowledge |

| Social Dimension | Individual competition | Collaborative learning and democratic participation |

| Connection to Life | Abstract, deferred application | Immediate, practical, relevant to experience |

| Purpose | Preparation for future life | Meaningful engagement in present experience |

While Dewey's work was revolutionary, it didn't develop in isolation. Understanding how his theories relate to other major educational theorists helps clarify both his unique contributions and his place in the broader landscape of educational thought.

Both Dewey and Jean Piaget emphasised active learning and the construction of knowledge. Piaget's stages of cognitive development align with Dewey's view that education must be appropriate to children's developmental levels. However, Piaget focused more on individual cognitive structures and biological maturation, while Dewey emphasised social interaction and cultural context. Dewey saw development as more fluid and less stage-bound than Piaget, arguing that appropriate experiences could accelerate learning in ways Piaget's stage theory might not predict.

Dewey and Lev Vygotsky share remarkably similar views on the social nature of learning, despite working in different contexts and times. Both rejected individualistic views of learning and emphasised the role of social interaction, language, and culture. Vygotsky's concept of the Zone of Proximal Development parallels Dewey's emphasis on providing experiences that challenge students appropriately. However, Vygotsky placed more explicit emphasis on language and cultural tools, while Dewey focused more broadly on experience and democratic participation.

Dewey and Montessori were contemporaries who both challenged traditional education, yet their approaches differed significantly. Both valued hands-on learning and child-centred education. However, Montessori's method is more structured, with specific materials designed to teach particular concepts in predetermined sequences. Dewey favoured more open-ended inquiry and problem-solving. Montessori emphasised individual work with materials, while Dewey placed greater emphasis on collaborative social learning and democratic classroom communities.

| Theorist | Key Similarity to Dewey | Key Difference from Dewey | Primary Focus |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jean Piaget | Active construction of knowledge | More emphasis on individual cognitive stages | Cognitive development |

| Lev Vygotsky | Social nature of learning | Greater focus on language and cultural tools | Social-cultural development |

| Maria Montessori | Child-centred, hands-on learning | More structured materials and sequences | Sensory development |

| Jerome Bruner | Discovery learning and inquiry | More emphasis on curriculum structure | Spiral curriculum |

| Paulo Freire | Education for democratic participation | More explicit focus on power and liberation | Critical pedagogy |

While Dewey's major works were published over a century ago, his ideas remain remarkably relevant to contemporary educational challenges and innovations. Modern educational movements and practices continue to draw heavily on Deweyan principles, often adapting them to new contexts and technologies.

Contemporary project-based and inquiry-based learning approaches are direct descendants of Dewey's educational philosophy. These methods structure learning around complex questions or problems that students investigate over extended periods. Students engage in research, collaboration, problem-solving, and creation of authentic products, precisely the kind of meaningful, experience-based learning Dewey advocated.

Modern PBL programmes maintain Dewey's emphasis on connecting learning to real-world contexts and student interests. Rather than learning subjects in isolation, students tackle interdisciplinary projects that mirror how knowledge is actually applied outside school. This approach has shown particular success in STEM education, where students design solutions to engineering challenges, conduct scientific investigations, or analyse real data sets.

The maker movement in education embodies Dewey's "learning by doing" principle through hands-on creation with tools, materials, and technology. Makerspaces in schools provide environments where students design, build, and tinker, developing both technical skills and habits of creative problem-solving. This approach integrates science, technology, engineering, arts, and mathematics (STEAM) in ways that echo Dewey's integrated curriculum.

Digital fabrication tools like 3D printers, laser cutters, and robotics kits extend Dewey's vision into the 21st century. Students engage in the complete design cycle: identifying problems, generating solutions, prototyping, testing, and iterating, all fundamental aspects of Deweyan experiential learning.

Dewey's vision of schools as democratic communities has inspired various alternative school models. Democratic schools give students significant voice in school governance, curriculum decisions, and community rules. Some schools hold regular meetings where students and teachers have equal votes on important decisions, directly implementing Dewey's belief that democratic participation must be practiced, not just studied.

Even in more conventional settings, there's growing recognition of the importance of student voice and agency. Practices like student-led conferences, choice in assignments, and collaborative goal-setting reflect Deweyan principles of democratic education and student ownership of learning.

Dewey's complete view of education, addressing intellectual, social, emotional, and moral development, aligns with contemporary whole child approaches. Social-emotional learning (SEL) programmes recognise that education isn't just about academic content but also about developing skills for collaboration, emotional regulation, empathy, and responsible decision-making.

This perspective mirrors Dewey's rejection of narrow, purely academic education in favour of preparing students for full participation in democratic society. Modern research in neuroscience and psychology has validated Dewey's intuition that cognitive and emotional development are deeply intertwined.

Place-based education connects learning to local communities, environments, and cultures, a contemporary application of Dewey's emphasis on grounding education in students' lived experiences. Students might study local ecology, investigate community issues, document neighbourhood history, or partner with local organisations on service projects.

This approach makes learning immediately relevant and meaningful while developing students' connection to and responsibility for their communities. It embodies Dewey's view that education should contribute to social progress and democratic participation.

While Dewey couldn't have anticipated modern technology, his principles apply powerfully to digital learning environments. Well-designed educational technology can provide interactive simulations, authentic audiences for student work, access to real-world data, and opportunities for collaboration across distances, all supporting experiential, inquiry-based learning.

However, technology can also be used in ways that contradict Deweyan principles, as a delivery mechanism for passive content consumption or drill-and-practise exercises. The key is whether technology enables active inquiry, meaningful creation, and social interaction, or simply automates traditional transmission models of education.

Applying John Dewey's theories in the classroom requires a shift from traditional, teacher-centred approaches to more student-centred, experiential methods. Here are several strategies for integrating Dewey's principles into your teaching practise:

By implementing these strategies, teachers can create a changing, engaging, and student-centred classroom that reflects John Dewey's vision of education as a process of active inquiry, personal growth, and social responsibility.

The impact of learning by doing on student outcomes is significant, influencing not only academic achievement but also broader aspects of student development.

While Dewey's educational philosophy has been tremendously influential, it has also faced significant challenges and criticisms, both during his lifetime and in subsequent decades.

One major challenge is the complexity of implementing Deweyan education at scale. Creating genuinely experiential, inquiry-based learning environments requires significant teacher expertise, flexibility, resources, and time. It's far more demanding than traditional instruction where teachers follow predetermined curricula and textbooks. Many teachers haven't experienced this type of education themselves and may lack models for how to facilitate it effectively.

Additionally, Dewey's integrated, project-based approach doesn't fit easily into conventional school structures with fixed class periods, separate subject departments, and standardised curricula. Implementing his vision often requires systemic changes that can be difficult to achieve within existing institutional constraints.

Dewey's approach raises challenges for assessment and accountability. Traditional tests that measure recall of factual knowledge don't align well with learning focused on inquiry, problem-solving, and application. Developing authentic assessments that capture the full range of student learning in experiential contexts is complex and time-consuming.

In an era of high-stakes standardised testing and accountability measures, many educators feel pressure to prioritise content coverage and test preparation over the kind of deep, experience-based learning Dewey advocated. This tension between progressive educational ideals and accountability demands remains a significant challenge.

Critics have argued that Dewey's child-centred approach might sacrifice academic rigour and systematic knowledge development. If curriculum is determined primarily by student interests and experiences, how can we ensure students master essential knowledge and skills? Some worry that progressive education can become unstructured and lacking in intellectual challenge.

Dewey himself rejected this criticism, arguing that his approach demands more intellectual rigour, not less. However, this concern persists, particularly when progressive methods are poorly implemented or taken to extremes that Dewey himself wouldn't have endorsed.

Dewey's philosophy emerged from and spoke primarily to the American democratic context of his time. Some critics question whether his emphasis on democratic participation and individual inquiry translates effectively to different cultural contexts with varying values and educational traditions. Educational approaches that work in one context may require significant adaptation for others.

John Dewey's theory provides a comprehensive framework for transforming education into a evolving and meaningful experience for students. By embracing experiential learning, promoting critical thinking, and developing collaboration, educators can create classrooms where students not only acquire knowledge but also develop the skills, values, and dispositions necessary to thrive in a complex and ever-changing world. Dewey's emphasis on connecting learning to real-life experiences, enabling students to take ownership of their education, and cultivating a sense of social responsibility remains as relevant today as it was during his time. By implementing Dewey's principles in the classroom, educators can help students become active, engaged, and lifelong learners who are prepared to make a positive impact on society.

John Dewey's philosophy offers a timeless vision of education that emphasises the importance of experience, reflection, and social interaction in the learning process. By embracing his ideas, educators can create classrooms where students not only acquire knowledge but also develop the skills, values, and dispositions necessary to thrive in a complex and ever-changing world. Dewey's legacy continues to inspire educators to strive for a more democratic, student-centred, and experiential approach to education that enables learners to become active, engaged, and responsible citizens.

From maker education to inquiry-based learning, from democratic schools to social-emotional learning programmes, Dewey's influence can be seen throughout contemporary educational innovation. As we face new challenges, from climate change to technological disruption to democratic fragility, Dewey's vision of education as preparation for intelligent, collaborative participation in democratic life becomes ever more vital.

John Dewey (1859-1952) emerged from humble beginnings in Burlington, Vermont, to become one of the most influential educational philosophers of the modern era. As a young academic at the University of Michigan and later at the University of Chicago, Dewey witnessed firsthand the rigid, authoritarian teaching methods of the late Victorian period, which sparked his determination to reimagine education entirely.

His breakthrough came in 1896 when he established the Laboratory School at the University of Chicago, where children learnt through cooking, sewing, and woodworking rather than sitting silently in rows. This experimental approach allowed Dewey to test his radical idea that children learn best when education mirrors real life. Teachers today can apply this principle by incorporating everyday activities into lessons; for instance, teaching fractions through recipe measurements or exploring local history through community interviews.

Dewey's intellectual process was deeply influenced by Charles Sanders Peirce's pragmatism and his own observations of industrialisation's impact on society. He recognised that traditional education, designed for an agricultural society, failed to prepare pupils for democratic participation and modern work. His experiences teaching philosophy whilst raising his own children shaped his conviction that education must develop critical thinking and social cooperation.

For contemporary educators, understanding Dewey's background illuminates why he championed pupil voice and collaborative learning. Try implementing his philosophy by establishing classroom councils where pupils help set learning goals, or create cross-curricular projects that mirror real-world problem-solving. These approaches, rooted in Dewey's life experiences, transform classrooms from places of passive reception into active learning communities where pupils develop both academic knowledge and democratic skills essential for modern citizenship.

Born in Vermont in 1859, John Dewey emerged from humble beginnings to become America's most influential educational philosopher. His childhood experiences in rural New England, where practical skills and community cooperation were essential, profoundly shaped his later educational theories. As a classroom teacher, you might recognise these values in how collaborative learning and real-world applications enhance pupil engagement today.

Dewey's academic process took him from the University of Vermont to Johns Hopkins University, where he earned his doctorate in philosophy in 1884. His time teaching at the University of Michigan and later the University of Chicago allowed him to observe traditional educational methods firsthand, leading him to question why students struggled with abstract concepts disconnected from their lived experiences. This observation mirrors what many teachers notice when pupils ask 'When will I ever use this?' during lessons.

The turning point came in 1896 when Dewey established the Laboratory School at the University of Chicago, often called the 'Dewey School'. Here, children aged 4 to 14 learned through cooking, carpentry, and textile work rather than traditional subjects taught in isolation. Teachers today can apply this principle by integrating maths into cooking activities or incorporating science into gardening projects, making abstract concepts tangible and memorable.

Throughout his 93-year life, Dewey published over 40 books and 700 articles, consistently advocating for education that prepared children for democratic participation. His work at Columbia University Teachers College from 1904 to 1930 influenced thousands of educators who spread his progressive ideas globally. Understanding Dewey's background helps teachers appreciate why his emphasis on experiential learning and democratic classrooms remains relevant in contemporary British education, particularly as we prepare pupils for an increasingly collaborative workplace.

Experiential learning sits at the heart of Dewey's educational philosophy, fundamentally changing how we understand the learning process. Rather than viewing students as empty vessels waiting to be filled with knowledge, Dewey argued that genuine understanding emerges when pupils actively engage with their environment, test ideas, and reflect on outcomes. This approach transforms the classroom from a place of passive reception into a laboratory for discovery, where mistakes become valuable learning opportunities and curiosity drives investigation.

The learning cycle Dewey proposed follows a natural progression: pupils encounter a problem or challenge, form hypotheses about potential solutions, test these ideas through action, and reflect on the results to refine their understanding. For instance, when teaching about plant growth, rather than simply presenting facts about photosynthesis, teachers might have pupils design experiments with different light conditions, water amounts, and soil types. Students document their observations, analyse results, and draw conclusions based on their direct experience, making the scientific method tangible and memorable.

Implementing experiential learning requires careful planning but yields remarkable results in pupil engagement and retention. Teachers can start small by incorporating hands-on activities into existing lessons; a history class studying Victorian Britain might recreate a Victorian classroom, complete with strict rules and rote learning, allowing pupils to experience and then critically analyse educational practices of the era. Mathematics lessons benefit from real-world problem-solving, such as planning a school event within a budget, where pupils apply percentages, addition, and multiplication whilst developing practical skills.

Research consistently supports Dewey's approach, with studies showing that pupils who engage in experiential learning demonstrate better problem-solving abilities and deeper conceptual understanding than those taught through traditional methods. The key lies in structured reflection; teachers must guide pupils to connect their experiences to broader concepts, ensuring that hands-on activities translate into transferable knowledge and skills that extend beyond the classroom walls.

John Dewey's Theory, also known as progressive education, advocates for experiential learning, critical thinking, and social cooperation. It emphasizes that students learn best through active participation, inquiry, and real-world problem-solving.

To implement Dewey's Theory, engage students in hands-on activities and collaborative projects. Encourage critical thinking through meaningful questions and discussions. Connect lessons to real-world issues and encourage a democratic classroom environment where students have a voice.

The benefits include improved retention, critical thinking skills, and social cooperation. Students learn to solve problems effectively and become better prepared for active citizenship in a democratic society.

Common mistakes include failing to balance theoretical knowledge with practical experience, neglecting the democratic aspects of classroom management, and not effectively connecting lessons to real-world contexts.

To assess the effectiveness, observe increased student engagement, improved problem-solving skills, and a shift towards critical thinking. Additionally, monitor improvements in democratic classroom behaviour and collaboration among students.

Dewey's educational philosophy

Dewey distinguished between genuine educational experiences and 'miseducative' ones. Rate each classroom activity against his two criteria: continuity (does it lead to further growth?) and interaction (does the pupil actively engage with the environment?).

These studies examine how John Dewey's progressive education philosophy, particularly experiential learning and democratic pedagogy, continues to shape modern teaching practice.

Experiential Learning Theory as a Guide for Experiential Educators in Higher Education View study ↗

494 citations

Kolb & Kolb (2022)

This landmark paper traces the direct line from Dewey's experiential education philosophy to Kolb's learning cycle, providing the most comprehensive modern framework for designing experience-based lessons. The practical guidelines for creating concrete experiences, reflective observation, abstract conceptualisation and active experimentation give teachers a structured way to implement Dewey's vision.

Disney, Dewey, and the Death of Experience in Education View study ↗

31 citations

Roberts (2006)

Roberts argues that contemporary education has commodified experience, turning Dewey's active, inquiry-driven vision into passive, consumption-based activities. The critique helps teachers distinguish between genuine experiential learning, where pupils investigate real problems, and superficial experience, where activity substitutes for thinking.

John Dewey's High Hopes for Play: Democracy and Education and Progressive Era Controversies View study ↗

11 citations

Beatty (2017)

Beatty recovers Dewey's original arguments about play as a vehicle for democratic learning, showing how his ideas were both adopted and distorted by the progressive education movement. For early years and primary teachers, this historical analysis clarifies what Dewey actually meant by learning through play, distinguishing purposeful exploration from unstructured free time.

Facilitating the Professional Learning of New Teachers Through Critical Reflection on Practice View study ↗

146 citations

Harrison, Lawson & Wortley (2005)

Dewey considered reflection the bridge between experience and understanding. This study shows how structured reflective practice during mentoring meetings helps new teachers convert their classroom experiences into professional knowledge, directly implementing Dewey's principle that experience without reflection is merely activity.

Constructivism-Based Teaching and Learning in Indonesian Education View study ↗

42 citations

Suhendi, Purwarno & Chairani (2021)

This classroom-based study demonstrates how Deweyan constructivism works in practice, with pupils building understanding through guided investigation rather than passive reception. The evidence that constructivist approaches produce deeper understanding while requiring more careful teacher scaffolding reflects Dewey's own recognition that progressive education demands more skill from teachers, not less.

John Dewey's theory revolutionised modern education by proposing that learning should be experiential, democratic, and deeply connected to real-world problem-solving rather than rote memorisation. The American philosopher and educator believed that students learn best through active participation participation and inquiry, where they engage with their environment to construct knowledge collaboratively. His progressive approach emphasised critical thinking, social cooperation, and preparing students for active citizenship in a democratic society. These principles fundamentally challenged traditional teaching methods and continue to shape educational practices worldwide today.

John Dewey was an American philosopher, psychologist and educational reformer widely recognised as one of the most influential thinkers in education.

He developed a unique set of theories about education and social reform, which have since come to be known as the "John Dewey Theory". His effective ideas about education focused on experiential learning, the idea that we can learn best by actively engaging with the material rather than passive listening to lectures or memorizing facts. He also advocated for progressive methods of powerful questioning and dialogue to enable more meaningful exchange during classrooms.

At the core of John Dewey's theory is the notion that human experience should be a guiding light in education and social reform. He argued that all forms of knowledge should be grounded inseparably in practical, real-world experience and that meaningful exploration and learning could only truly take place when students engaged with their material firsthand or through experimentation.

His view was that theoretical information should always be applied practically to ensure an authentic understanding of whatever is being taught.

Education, for Dewey, is not only about gaining theoretical knowledge but also getting practical experience. He viewed education from a complete perspective whereby learning is seen as a continuous process that combines knowledge with life experiences and encourages students to integrate thinking skills with tangible results. This view of education ensures students have significant experiences which are internally meaningful and contribute to their growth as learners.

John Dewey's view on pedagogy was that it should be a complete approach to teaching and learning. He believed in using experiential learning as part of the educational process, whereby students are encouraged to combine their theoretical knowledge with practical experience. Dewey also focused on providing meaningful experiences that contribute to a student's growth as learners. He believed that this type of pedagogy could help shape a well-rounded student who is able to think critically and take tangible skills into the world.

John Dewey's educational theory cannot be fully understood without examining its philosophical foundation: pragmatism. As one of the leading American pragmatist philosophers alongside William James and Charles Sanders Peirce, Dewey developed a philosophy that fundamentally challenged traditional approaches to knowledge and truth.

Pragmatism, at its core, asserts that the truth or meaning of an idea lies in its practical consequences and applications. For Dewey, this meant that knowledge isn't something abstract that exists independently of human experience. Instead, knowledge is created through the process of inquiry and problem-solving in real-world contexts. This philosophical stance had profound implications for education.

Dewey rejected the notion that learning should be about absorbing fixed truths handed down by authorities. Rather, he argued that students should be engaged in active inquiry, testing ideas against experience, and reconstructing their understanding based on outcomes. This process of "learning by doing" wasn't simply a pedagogical technique, it was a direct application of pragmatist philosophy to education.

The pragmatist emphasis on consequences and practical application meant that Dewey viewed education as preparation for participation in democratic society. Knowledge gains its value not from its correspondence to some abstract ideal, but from its usefulness in helping individuals navigate real problems and contribute to social progress. This perspective transformed education from a process of passive transmission to one of active construction and social participation.

Dewey's pragmatism also led him to emphasise the continuity between thought and action. Unlike traditional philosophers who separated mind from body or theory from practise, Dewey saw thinking as a form of doing, a practical activity aimed at solving problems. This integration of thought and action became central to his educational approach, where reflection and experience work together in a continuous cycle of learning.

In the classroom, pragmatism translates to creating learning environments where students engage with genuine problems, test hypotheses through action, and refine their understanding based on results. This approach aligns closely with modern constructivist approaches that emphasise knowledge construction rather than knowledge transmission.

Dewey's learning by doing approach emphasises that students learn best through hands-on experiences and active engagement rather than passive listening. This method involves students directly experimenting with materials, solving real problems, and reflecting on their experiences to construct knowledge. Research shows this approach can increase retention rates by up to 20% compared to traditional lecture methods.

John Dewey and many other pragmatists believe that learners must experience reality without any modifications. From John Dewey's academic viewpoint, students can only learn by adapting to their environment.

John Dewey's idea about the ideal classroom is very much similar to that of the educational psychologists democratic ideals. John Dewey believed that not only students learn, but teachers also learn from the students. When teachers and students, both learn from each other, together they create extra value for themselves.

Many educational psychologists from different countries follow John Dewey's revolutionary education theory to implement the modern educational system. In that era, John Dewey's theory concerning schooling proved to be valid for progressive education and learning.

Progressive education involves the important aspect of learning by doing. John Dewey's theory proposed that individuals' hands-on approach offers the best way of learning.

Due to this, the philosophies of John Dewey have been made a part of the eminent psychologists pragmatic philosophy of education and learning.

John Dewey's educational philosophy emphasises the concept of "Learning by Doing," placing significant emphasis on experiential education. Central to Dewey's ideas are the objects of knowledge and their relationship with the learner. As mentioned, Dewey posits that knowledge is not merely passively received but actively constructed by the learner through experience. This aligns with constructivist approaches to education. The process of learning, thus, becomes a active interaction between the learner and the object of knowledge.

John Dewey's educational theories have implications for problem-based learning.

Dewey's learning by doing approach follows a specific cycle that mirrors the scientific method. First, learners encounter a genuine problem or question that arises from their experience. This isn't an artificial textbook problem, but something that genuinely puzzles or challenges them. Second, they formulate hypotheses or possible solutions based on their existing knowledge and experience.

Third, learners test these hypotheses through active experimentation and hands-on engagement. This might involve conducting experiments, building models, engaging in simulations, or applying concepts to real-world situations. Fourth, they observe and reflect on the outcomes of their actions, noting what worked, what didn't, and why. Finally, learners reconstruct their understanding based on these reflections, incorporating new insights into their knowledge framework.

This cycle doesn't end with a single iteration. Instead, new questions and problems emerge from the solutions found, creating a continuous spiral of learning and growth. This approach shares similarities with collaborative learning strategies that emphasise peer interaction and shared problem-solving.

John Dewey wasn't just a theorist, he was a practitioner who sought to transform American education through the progressive education movement. In 1896, Dewey founded the Laboratory School at the University of Chicago, often called the "Dewey School," which served as a testing ground for his educational theories.

The progressive education movement, which gained momentum in the early 20th century, challenged the authoritarian, teacher-centred model that dominated schools. Traditional classrooms of that era were characterised by rote memorisation, strict discipline, recitation of facts, and a rigid curriculum disconnected from students' lives. Dewey and other progressive educators argued this approach stifled creativity, failed to prepare students for democratic citizenship, and ignored the natural curiosity and interests of children.

Progressive education, inspired by Dewey's theories, emphasised several key principles. First, education should be child-centred rather than subject-centred. This meant starting with students' interests, experiences, and developmental stages, then building curriculum around these foundations. Second, learning should be active and experiential rather than passive. Students should engage in projects, experiments, and real-world problem-solving rather than simply listening to lectures.

Third, the curriculum should be integrated rather than fragmented into isolated subjects. Dewey argued that life doesn't come divided into separate disciplines like mathematics, science, and history. Instead, real problems require drawing on multiple forms of knowledge simultaneously. Fourth, schools should be democratic communities where students learn cooperation, responsibility, and civic participation through practise, not just through textbooks.

The Laboratory School put these principles into practise. Instead of traditional subjects taught in isolation, students engaged in "occupations", activities like cooking, carpentry, and gardening that integrated multiple disciplines naturally. When students built a playhouse, for example, they learned mathematics through measurement, science through understanding materials and structures, history through studying different architectural styles, and social skills through collaborative work.

The progressive education movement spread throughout America and internationally, influencing the development of numerous alternative school models. While the movement faced criticism and backlash, particularly during periods emphasising "back to basics" education, its core principles continue to shape contemporary educational reform efforts, including project-based learning initiatives.

To fully appreciate Dewey's revolutionary approach, understand how it contrasts with traditional educational models that dominated, and in many cases, still dominate, schools worldwide.

Traditional education is rooted in what Dewey called the "spectator theory of knowledge." This view treats knowledge as a collection of established truths that exist independently of learners. Education becomes a process of transmission, where teachers who possess knowledge transfer it to students who don't. The student's role is to receive, memorise, and reproduce this knowledge.

Dewey's approach, by contrast, is based on the idea that knowledge is constructed through experience and inquiry. Students aren't empty vessels to be filled, but active agents who build understanding through interaction with their environment. Knowledge isn't fixed and final, but provisional and subject to revision based on new experiences and evidence.

In traditional classrooms, authority flows from the teacher, who determines what will be learned, when, and how. The curriculum is predetermined, often standardised across entire school systems, and teachers are expected to "cover" specific content regardless of student interest or readiness. Discipline is typically maintained through external controls, rules, punishments, and rewards.

Dewey advocated for a more democratic classroom where teachers serve as guides and facilitators rather than authoritarian figures. While teachers maintain responsibility for structuring learning environments and guiding inquiry, students have genuine voice in determining topics of study, methods of investigation, and ways of demonstrating learning. Discipline emerges naturally from engagement in meaningful work rather than being imposed externally.

Traditional education organises curriculum around academic disciplines that are taught separately and sequentially. Mathematics is taught in one period, science in another, with little connection between them. Content is often abstract and disconnected from students' lives. Assessment focuses on measuring how much content students can recall, typically through tests and examinations.

Dewey's approach integrates subjects around themes, problems, or projects that mirror real-world complexity. Assessment is ongoing and embedded in the learning process itself, focusing on students' ability to apply knowledge to solve genuine problems rather than simply recall facts. This approach connects strongly with modern inquiry-based learning methods.

| Aspect | Traditional Education | Dewey's Progressive Education |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge Source | Fixed body of established truths | Constructed through experience and inquiry |

| Teacher Role | Authority and knowledge transmitter | Facilitator and co-learner |

| Student Role | Passive receiver of information | Active constructor of knowledge |

| Learning Method | Listening, memorisation, recitation | Experimentation, problem-solving, reflection |

| Curriculum Organisation | Separate subjects, sequential lessons | Integrated themes, project-based |

| Motivation | External rewards and punishments | Intrinsic interest and meaningful engagement |

| Assessment | Standardised tests, recall of facts | Authentic tasks, application of knowledge |

| Social Dimension | Individual competition | Collaborative learning and democratic participation |

| Connection to Life | Abstract, deferred application | Immediate, practical, relevant to experience |

| Purpose | Preparation for future life | Meaningful engagement in present experience |

While Dewey's work was revolutionary, it didn't develop in isolation. Understanding how his theories relate to other major educational theorists helps clarify both his unique contributions and his place in the broader landscape of educational thought.

Both Dewey and Jean Piaget emphasised active learning and the construction of knowledge. Piaget's stages of cognitive development align with Dewey's view that education must be appropriate to children's developmental levels. However, Piaget focused more on individual cognitive structures and biological maturation, while Dewey emphasised social interaction and cultural context. Dewey saw development as more fluid and less stage-bound than Piaget, arguing that appropriate experiences could accelerate learning in ways Piaget's stage theory might not predict.

Dewey and Lev Vygotsky share remarkably similar views on the social nature of learning, despite working in different contexts and times. Both rejected individualistic views of learning and emphasised the role of social interaction, language, and culture. Vygotsky's concept of the Zone of Proximal Development parallels Dewey's emphasis on providing experiences that challenge students appropriately. However, Vygotsky placed more explicit emphasis on language and cultural tools, while Dewey focused more broadly on experience and democratic participation.

Dewey and Montessori were contemporaries who both challenged traditional education, yet their approaches differed significantly. Both valued hands-on learning and child-centred education. However, Montessori's method is more structured, with specific materials designed to teach particular concepts in predetermined sequences. Dewey favoured more open-ended inquiry and problem-solving. Montessori emphasised individual work with materials, while Dewey placed greater emphasis on collaborative social learning and democratic classroom communities.

| Theorist | Key Similarity to Dewey | Key Difference from Dewey | Primary Focus |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jean Piaget | Active construction of knowledge | More emphasis on individual cognitive stages | Cognitive development |

| Lev Vygotsky | Social nature of learning | Greater focus on language and cultural tools | Social-cultural development |

| Maria Montessori | Child-centred, hands-on learning | More structured materials and sequences | Sensory development |

| Jerome Bruner | Discovery learning and inquiry | More emphasis on curriculum structure | Spiral curriculum |

| Paulo Freire | Education for democratic participation | More explicit focus on power and liberation | Critical pedagogy |

While Dewey's major works were published over a century ago, his ideas remain remarkably relevant to contemporary educational challenges and innovations. Modern educational movements and practices continue to draw heavily on Deweyan principles, often adapting them to new contexts and technologies.

Contemporary project-based and inquiry-based learning approaches are direct descendants of Dewey's educational philosophy. These methods structure learning around complex questions or problems that students investigate over extended periods. Students engage in research, collaboration, problem-solving, and creation of authentic products, precisely the kind of meaningful, experience-based learning Dewey advocated.

Modern PBL programmes maintain Dewey's emphasis on connecting learning to real-world contexts and student interests. Rather than learning subjects in isolation, students tackle interdisciplinary projects that mirror how knowledge is actually applied outside school. This approach has shown particular success in STEM education, where students design solutions to engineering challenges, conduct scientific investigations, or analyse real data sets.

The maker movement in education embodies Dewey's "learning by doing" principle through hands-on creation with tools, materials, and technology. Makerspaces in schools provide environments where students design, build, and tinker, developing both technical skills and habits of creative problem-solving. This approach integrates science, technology, engineering, arts, and mathematics (STEAM) in ways that echo Dewey's integrated curriculum.

Digital fabrication tools like 3D printers, laser cutters, and robotics kits extend Dewey's vision into the 21st century. Students engage in the complete design cycle: identifying problems, generating solutions, prototyping, testing, and iterating, all fundamental aspects of Deweyan experiential learning.

Dewey's vision of schools as democratic communities has inspired various alternative school models. Democratic schools give students significant voice in school governance, curriculum decisions, and community rules. Some schools hold regular meetings where students and teachers have equal votes on important decisions, directly implementing Dewey's belief that democratic participation must be practiced, not just studied.

Even in more conventional settings, there's growing recognition of the importance of student voice and agency. Practices like student-led conferences, choice in assignments, and collaborative goal-setting reflect Deweyan principles of democratic education and student ownership of learning.

Dewey's complete view of education, addressing intellectual, social, emotional, and moral development, aligns with contemporary whole child approaches. Social-emotional learning (SEL) programmes recognise that education isn't just about academic content but also about developing skills for collaboration, emotional regulation, empathy, and responsible decision-making.

This perspective mirrors Dewey's rejection of narrow, purely academic education in favour of preparing students for full participation in democratic society. Modern research in neuroscience and psychology has validated Dewey's intuition that cognitive and emotional development are deeply intertwined.

Place-based education connects learning to local communities, environments, and cultures, a contemporary application of Dewey's emphasis on grounding education in students' lived experiences. Students might study local ecology, investigate community issues, document neighbourhood history, or partner with local organisations on service projects.

This approach makes learning immediately relevant and meaningful while developing students' connection to and responsibility for their communities. It embodies Dewey's view that education should contribute to social progress and democratic participation.

While Dewey couldn't have anticipated modern technology, his principles apply powerfully to digital learning environments. Well-designed educational technology can provide interactive simulations, authentic audiences for student work, access to real-world data, and opportunities for collaboration across distances, all supporting experiential, inquiry-based learning.

However, technology can also be used in ways that contradict Deweyan principles, as a delivery mechanism for passive content consumption or drill-and-practise exercises. The key is whether technology enables active inquiry, meaningful creation, and social interaction, or simply automates traditional transmission models of education.

Applying John Dewey's theories in the classroom requires a shift from traditional, teacher-centred approaches to more student-centred, experiential methods. Here are several strategies for integrating Dewey's principles into your teaching practise:

By implementing these strategies, teachers can create a changing, engaging, and student-centred classroom that reflects John Dewey's vision of education as a process of active inquiry, personal growth, and social responsibility.

The impact of learning by doing on student outcomes is significant, influencing not only academic achievement but also broader aspects of student development.

While Dewey's educational philosophy has been tremendously influential, it has also faced significant challenges and criticisms, both during his lifetime and in subsequent decades.

One major challenge is the complexity of implementing Deweyan education at scale. Creating genuinely experiential, inquiry-based learning environments requires significant teacher expertise, flexibility, resources, and time. It's far more demanding than traditional instruction where teachers follow predetermined curricula and textbooks. Many teachers haven't experienced this type of education themselves and may lack models for how to facilitate it effectively.

Additionally, Dewey's integrated, project-based approach doesn't fit easily into conventional school structures with fixed class periods, separate subject departments, and standardised curricula. Implementing his vision often requires systemic changes that can be difficult to achieve within existing institutional constraints.

Dewey's approach raises challenges for assessment and accountability. Traditional tests that measure recall of factual knowledge don't align well with learning focused on inquiry, problem-solving, and application. Developing authentic assessments that capture the full range of student learning in experiential contexts is complex and time-consuming.

In an era of high-stakes standardised testing and accountability measures, many educators feel pressure to prioritise content coverage and test preparation over the kind of deep, experience-based learning Dewey advocated. This tension between progressive educational ideals and accountability demands remains a significant challenge.

Critics have argued that Dewey's child-centred approach might sacrifice academic rigour and systematic knowledge development. If curriculum is determined primarily by student interests and experiences, how can we ensure students master essential knowledge and skills? Some worry that progressive education can become unstructured and lacking in intellectual challenge.

Dewey himself rejected this criticism, arguing that his approach demands more intellectual rigour, not less. However, this concern persists, particularly when progressive methods are poorly implemented or taken to extremes that Dewey himself wouldn't have endorsed.

Dewey's philosophy emerged from and spoke primarily to the American democratic context of his time. Some critics question whether his emphasis on democratic participation and individual inquiry translates effectively to different cultural contexts with varying values and educational traditions. Educational approaches that work in one context may require significant adaptation for others.

John Dewey's theory provides a comprehensive framework for transforming education into a evolving and meaningful experience for students. By embracing experiential learning, promoting critical thinking, and developing collaboration, educators can create classrooms where students not only acquire knowledge but also develop the skills, values, and dispositions necessary to thrive in a complex and ever-changing world. Dewey's emphasis on connecting learning to real-life experiences, enabling students to take ownership of their education, and cultivating a sense of social responsibility remains as relevant today as it was during his time. By implementing Dewey's principles in the classroom, educators can help students become active, engaged, and lifelong learners who are prepared to make a positive impact on society.

John Dewey's philosophy offers a timeless vision of education that emphasises the importance of experience, reflection, and social interaction in the learning process. By embracing his ideas, educators can create classrooms where students not only acquire knowledge but also develop the skills, values, and dispositions necessary to thrive in a complex and ever-changing world. Dewey's legacy continues to inspire educators to strive for a more democratic, student-centred, and experiential approach to education that enables learners to become active, engaged, and responsible citizens.

From maker education to inquiry-based learning, from democratic schools to social-emotional learning programmes, Dewey's influence can be seen throughout contemporary educational innovation. As we face new challenges, from climate change to technological disruption to democratic fragility, Dewey's vision of education as preparation for intelligent, collaborative participation in democratic life becomes ever more vital.

John Dewey (1859-1952) emerged from humble beginnings in Burlington, Vermont, to become one of the most influential educational philosophers of the modern era. As a young academic at the University of Michigan and later at the University of Chicago, Dewey witnessed firsthand the rigid, authoritarian teaching methods of the late Victorian period, which sparked his determination to reimagine education entirely.

His breakthrough came in 1896 when he established the Laboratory School at the University of Chicago, where children learnt through cooking, sewing, and woodworking rather than sitting silently in rows. This experimental approach allowed Dewey to test his radical idea that children learn best when education mirrors real life. Teachers today can apply this principle by incorporating everyday activities into lessons; for instance, teaching fractions through recipe measurements or exploring local history through community interviews.

Dewey's intellectual process was deeply influenced by Charles Sanders Peirce's pragmatism and his own observations of industrialisation's impact on society. He recognised that traditional education, designed for an agricultural society, failed to prepare pupils for democratic participation and modern work. His experiences teaching philosophy whilst raising his own children shaped his conviction that education must develop critical thinking and social cooperation.

For contemporary educators, understanding Dewey's background illuminates why he championed pupil voice and collaborative learning. Try implementing his philosophy by establishing classroom councils where pupils help set learning goals, or create cross-curricular projects that mirror real-world problem-solving. These approaches, rooted in Dewey's life experiences, transform classrooms from places of passive reception into active learning communities where pupils develop both academic knowledge and democratic skills essential for modern citizenship.

Born in Vermont in 1859, John Dewey emerged from humble beginnings to become America's most influential educational philosopher. His childhood experiences in rural New England, where practical skills and community cooperation were essential, profoundly shaped his later educational theories. As a classroom teacher, you might recognise these values in how collaborative learning and real-world applications enhance pupil engagement today.

Dewey's academic process took him from the University of Vermont to Johns Hopkins University, where he earned his doctorate in philosophy in 1884. His time teaching at the University of Michigan and later the University of Chicago allowed him to observe traditional educational methods firsthand, leading him to question why students struggled with abstract concepts disconnected from their lived experiences. This observation mirrors what many teachers notice when pupils ask 'When will I ever use this?' during lessons.

The turning point came in 1896 when Dewey established the Laboratory School at the University of Chicago, often called the 'Dewey School'. Here, children aged 4 to 14 learned through cooking, carpentry, and textile work rather than traditional subjects taught in isolation. Teachers today can apply this principle by integrating maths into cooking activities or incorporating science into gardening projects, making abstract concepts tangible and memorable.

Throughout his 93-year life, Dewey published over 40 books and 700 articles, consistently advocating for education that prepared children for democratic participation. His work at Columbia University Teachers College from 1904 to 1930 influenced thousands of educators who spread his progressive ideas globally. Understanding Dewey's background helps teachers appreciate why his emphasis on experiential learning and democratic classrooms remains relevant in contemporary British education, particularly as we prepare pupils for an increasingly collaborative workplace.

Experiential learning sits at the heart of Dewey's educational philosophy, fundamentally changing how we understand the learning process. Rather than viewing students as empty vessels waiting to be filled with knowledge, Dewey argued that genuine understanding emerges when pupils actively engage with their environment, test ideas, and reflect on outcomes. This approach transforms the classroom from a place of passive reception into a laboratory for discovery, where mistakes become valuable learning opportunities and curiosity drives investigation.

The learning cycle Dewey proposed follows a natural progression: pupils encounter a problem or challenge, form hypotheses about potential solutions, test these ideas through action, and reflect on the results to refine their understanding. For instance, when teaching about plant growth, rather than simply presenting facts about photosynthesis, teachers might have pupils design experiments with different light conditions, water amounts, and soil types. Students document their observations, analyse results, and draw conclusions based on their direct experience, making the scientific method tangible and memorable.

Implementing experiential learning requires careful planning but yields remarkable results in pupil engagement and retention. Teachers can start small by incorporating hands-on activities into existing lessons; a history class studying Victorian Britain might recreate a Victorian classroom, complete with strict rules and rote learning, allowing pupils to experience and then critically analyse educational practices of the era. Mathematics lessons benefit from real-world problem-solving, such as planning a school event within a budget, where pupils apply percentages, addition, and multiplication whilst developing practical skills.

Research consistently supports Dewey's approach, with studies showing that pupils who engage in experiential learning demonstrate better problem-solving abilities and deeper conceptual understanding than those taught through traditional methods. The key lies in structured reflection; teachers must guide pupils to connect their experiences to broader concepts, ensuring that hands-on activities translate into transferable knowledge and skills that extend beyond the classroom walls.

John Dewey's Theory, also known as progressive education, advocates for experiential learning, critical thinking, and social cooperation. It emphasizes that students learn best through active participation, inquiry, and real-world problem-solving.

To implement Dewey's Theory, engage students in hands-on activities and collaborative projects. Encourage critical thinking through meaningful questions and discussions. Connect lessons to real-world issues and encourage a democratic classroom environment where students have a voice.

The benefits include improved retention, critical thinking skills, and social cooperation. Students learn to solve problems effectively and become better prepared for active citizenship in a democratic society.

Common mistakes include failing to balance theoretical knowledge with practical experience, neglecting the democratic aspects of classroom management, and not effectively connecting lessons to real-world contexts.

To assess the effectiveness, observe increased student engagement, improved problem-solving skills, and a shift towards critical thinking. Additionally, monitor improvements in democratic classroom behaviour and collaboration among students.

Dewey's educational philosophy

Dewey distinguished between genuine educational experiences and 'miseducative' ones. Rate each classroom activity against his two criteria: continuity (does it lead to further growth?) and interaction (does the pupil actively engage with the environment?).

These studies examine how John Dewey's progressive education philosophy, particularly experiential learning and democratic pedagogy, continues to shape modern teaching practice.

Experiential Learning Theory as a Guide for Experiential Educators in Higher Education View study ↗

494 citations

Kolb & Kolb (2022)

This landmark paper traces the direct line from Dewey's experiential education philosophy to Kolb's learning cycle, providing the most comprehensive modern framework for designing experience-based lessons. The practical guidelines for creating concrete experiences, reflective observation, abstract conceptualisation and active experimentation give teachers a structured way to implement Dewey's vision.

Disney, Dewey, and the Death of Experience in Education View study ↗

31 citations

Roberts (2006)

Roberts argues that contemporary education has commodified experience, turning Dewey's active, inquiry-driven vision into passive, consumption-based activities. The critique helps teachers distinguish between genuine experiential learning, where pupils investigate real problems, and superficial experience, where activity substitutes for thinking.

John Dewey's High Hopes for Play: Democracy and Education and Progressive Era Controversies View study ↗

11 citations

Beatty (2017)

Beatty recovers Dewey's original arguments about play as a vehicle for democratic learning, showing how his ideas were both adopted and distorted by the progressive education movement. For early years and primary teachers, this historical analysis clarifies what Dewey actually meant by learning through play, distinguishing purposeful exploration from unstructured free time.

Facilitating the Professional Learning of New Teachers Through Critical Reflection on Practice View study ↗

146 citations

Harrison, Lawson & Wortley (2005)

Dewey considered reflection the bridge between experience and understanding. This study shows how structured reflective practice during mentoring meetings helps new teachers convert their classroom experiences into professional knowledge, directly implementing Dewey's principle that experience without reflection is merely activity.

Constructivism-Based Teaching and Learning in Indonesian Education View study ↗

42 citations

Suhendi, Purwarno & Chairani (2021)

This classroom-based study demonstrates how Deweyan constructivism works in practice, with pupils building understanding through guided investigation rather than passive reception. The evidence that constructivist approaches produce deeper understanding while requiring more careful teacher scaffolding reflects Dewey's own recognition that progressive education demands more skill from teachers, not less.

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/john-deweys-theory#article","headline":"John Dewey's Theory","description":"Explore John Dewey's educational theories & how his ideas on experiential learning & democracy in education shape modern teaching.","datePublished":"2023-02-14T16:02:54.801Z","dateModified":"2026-02-15T12:39:58.402Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/john-deweys-theory"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/696a5bf9dc7411764d980c97_696a5bf7dc7411764d980b44_john-deweys-theory-infographic.webp","wordCount":5355},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/john-deweys-theory#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"John Dewey's Theory","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/john-deweys-theory"}]}]}