Learning Fundamentals: Core Principles Every Teacher Should Know

Master fundamental learning principles including cognitive load, memory, and attention. Discover the science that underpins effective teaching practice.

Master fundamental learning principles including cognitive load, memory, and attention. Discover the science that underpins effective teaching practice.

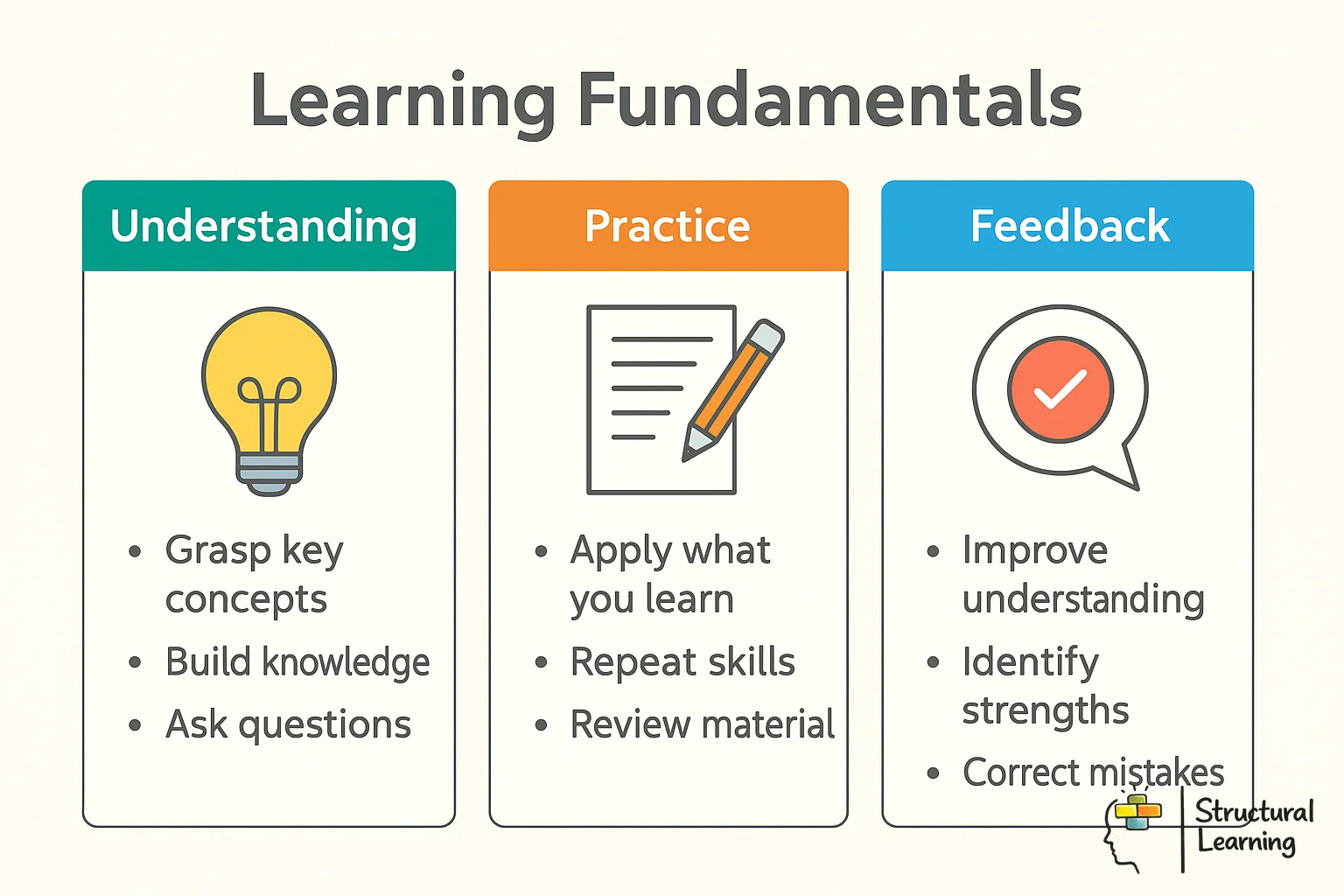

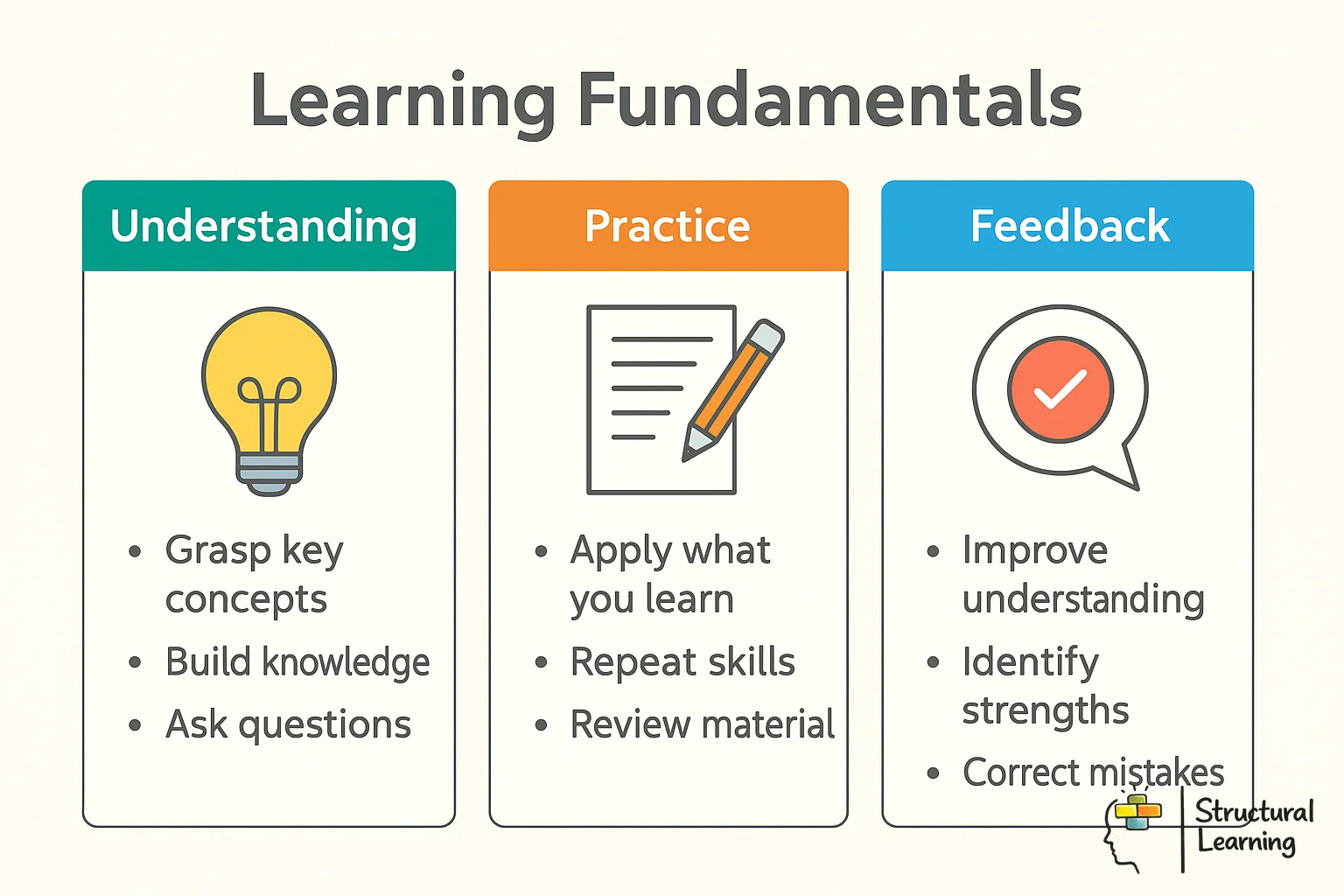

Learning Fundamentals matter because they shift focus from what teachers do to what students actually do during learning, which determines outcomes. Unlike complex frameworks that overwhelm teachers, these fundamentals provide simple, learnable behaviours that students can understand and apply themselves. This learner-centered approach enables students to take ownership of their learning processes, reducing anxiety and improving engagement.

Schools are inundated with frameworks, taxonomies, and research summaries. Each offers valuable insights, but their complexity often prevents implementation. Teachers recognise the value of Rosenshine's Principles or Bloom's Taxonomy yet struggle to translate these frameworks into daily classroom practice.

Learning Fundamentals take a different approach. Rather than describing what effective teachers do (teacher-centred frameworks), they describe what effective learners do (learner-centred fundamentals). This shift matters because ultimately, learning happens in students' minds. The most brilliant explanation produces no learning if students do not engage cognitively with it.

By focusing on learnable student behaviours expressed in simple language, Learning Fundamentals become accessible to students themselves, not just teachers. When students understand what effective learning looks like, they can take ownership of their own learning processes, reducing student anxiety and enabling them to engage more effectively, which significantly impacts student motivationand their cognitive processes.

Effective learners do not immediately begin tasks. They pause to consider what the task requires, what they already know that might help, and what approach might work best. This metacognitive step, though brief, significantly improves outcomes.

Research on problem-solving consistently shows that experts spend more time understanding problems before attempting solutions, while novices dive in immediately. Teaching students to plan, even briefly, builds this expert habit. This approach aligns with systems theory principles that emphasise understanding interconnected learning processes. Questions like "What do I need to find out?" and "What do I already know about this?" prompt the planning process.

Planning also involves monitoring: checking whether the chosen approach is working and adjusting if necessary. Students who plan tend to notice when they are stuck earlier and are more willing to try alternative strategies, which supports both academic success and student wellbeing.

Information presented in organised structures is easier to understand and remember than disconnected facts. Effective learners actively organise information, creating hierarchies, categories, timelines, or other structures that reveal relationships.

Organisation requires decisions about what belongs together and what differs, which features are central and which are peripheral. These decisions force engagement with meaning rather than surface features. A student organising historical events into causes and consequences is processing more deeply than one listing dates chronologically.

Teaching organisation involves making structural thinking visible: concept maps, tables comparing features, hierarchical outlines, and other graphic organisers externalise the mental work of organisation so it can be taught and practised.

Isolated facts are hard to remember and impossible to apply. Understanding comes from seeing how ideas relate to each other and to what you already know. Effective learners actively seek connections.

Connections operate at multiple levels. Within a topic, students connect new examples to general principles. Across topics, they notice when concepts from one area apply to another. Beyond school, they connect academic learning to their own experience and observations.

Teachers can prompt connecting through questions: "How does this relate to what we learned last week?" "Where have you seen something like this before?" "What would happen if we applied this idea to that situation?" Over time, students internalise these prompts and ask such questions themselves.

Articulating thinking, whether to others or to oneself, clarifies and strengthens understanding. The act of putting thoughts into words reveals gaps and forces precision. Students who can explain an idea to someone else understand it more deeply than those who merely recognise it.

Talk also serves social purposes. Discussing ideas with peers exposes students to different perspectives and requires them to defend or revise their understanding. Collaborative sense-making often produces better outcomes than individual study.

The emphasis on talk before writing is deliberate. Students who clarify thinking orally before committing to writing produce better written work and experience less writing anxiety. The phrase "talk first, then write" captures this sequence.

Display the four fundamentals prominently in classrooms. Use the language consistently when setting up activities and when providing feedback. When students succeed, name which fundamental they used effectively. When they struggle, suggest which fundamental might help.

Consistency across the school amplifies impact. When all teachers use the same language, students encounter it frequently enough to internalise it. A common vocabulary for learning becomes part of school culture.

Each fundamental comprises specific strategies that can be modelled and practised. Planning might involve underlining key words in questions, sketching a quick diagram, or listing what you know before starting.Strategies for organisation include concept mapping, outlining, and creating tables. Connecting can be taught by prompting students to find analogies or consider alternative perspectives. Articulation can be developed through think-pair-share activities, debates, or presentations.

Encourage students to reflect on their use of the fundamentals. Prompts like "Which fundamental did I use most effectively today?" or "Which fundamental do I need to focus on tomorrow?" help students become more aware of their learning processes. Students can also set goals related to specific fundamentals, such as "I will plan for five minutes before starting my next assignment."

Effective assessment transforms from a judgement tool into a powerful learning accelerator when it aligns with fundamental learning principles. Dylan Wiliam's research on formative assessment demonstrates that strategic feedback can produce learning gains equivalent to r educing class sizes by half, yet only when assessment directly connects to students' current understanding and next steps. Rather than simply measuring what students know, assessment that supports learning fundamentals actively diagnoses misconceptions, reveals thinking processes, and guides both teacher instruction and student self-regulation.

The timing and nature of feedback proves crucial for maximising learning outcomes. John Hattie's synthesis reveals that feedback works best when it answers three fundamental questions: Where am I going? How am I doing? Where to next? This approach shifts assessment from retroactive grading towards real-time learning support. Students need immediate, specific feedback during skill acquisition, whilst delayed feedback proves more effective for retention and transfer tasks. Quality feedback focuses on the task and process rather than personal praise, helping students develop accurate self-assessment capabilities.

Practical classroom implementation centres on making student thinking visible through low-stakes assessment strategies. Exit tickets, mini whiteboards, and structured peer feedback create continuous assessment loops that inform immediate teaching adjustments. These approaches reduce cognitive load whilst providing rich diagnostic information, enabling teachers to address learning gaps before they compound and students to develop metacognitive awareness of their own learning progress.

Effective differentiation begins with understanding that learning fundamentals remain constant whilst delivery methods must flex. Vygotsky's concept of the Zone of Proximal Development illustrates why one-size-fits-all approaches fail: students operate at different developmental stages simultaneously within the same classroom. This means core principles like clear explanations, guided practice, and feedback loops apply universally, but their implementation requires careful calibration to individual cognitive capacity and prior knowledge.

For SEND students and varying ability levels, cognitive load theory becomes particularly crucial. John Sweller's research demonstrates that learners have limited working memory capacity, suggesting teachers must reduce extraneous cognitive burden through strateg ic scaffolding. This might involve breaking complex tasks into smaller steps for some students whilst providing extension challenges for others, all whilst maintaining the same fundamental learning objectives across the class.

Practical differentiation centres on flexible grouping and multiple means of representation. Consider offering visual, auditory, and kinaesthetic pathways to the same content, allowing students to access learning through their strongest channels. Use formative assessment data to create dynamic groups that change based on specific learning needs rather than fixed ability labels. This approach ensures every student receives appropriate challenge whilst building towards shared learning goals.

Understanding the cognitive science behind learning fundamentals transforms teaching from intuition to informed practice. John Sweller's cognitive load theory demonstrates how our working memory can only process limited information simultaneously, explaining why breaking complex concepts into manageable chunks proves so effective. Meanwhile, Hermann Ebbinghaus's research on the forgetting curve reveals that students lose approximately 50% of new information within hours unless it's reinforced, highlighting the critical importance of spaced practice and retrieval opportunities.

Rosenshine's principles of instruction, derived from extensive classroom research, show that explicit teaching followed by guided practice consistently produces superior student outcomes compared to discovery-based approaches alone. This aligns with cognitive science findings that novice learners benefit from direct instruction whilst building foundational knowledge, whereas expert learners can handle more open-ended exploration once they've developed robust mental schemas.

In practical terms, this research evidence suggests structuring lessons with clear learning objectives, modelling new concepts explicitly, providing immediate feedback, and incorporating regular low-stakes retrieval practice. Rather than overwhelming students with too much information at once, effective t eachers sequence learning carefully, building complexity gradually whilst ensuring each step is thoroughly understood before progressing.

Learning Fundamentals offer a practical and accessible framework for improving student learning. By focusing on learnable student behaviours and using simple, consistent language, teachers can helps students to take ownership of their learning. The four fundamentals, Plan, Organise, Connect, and Talk, provide a common language for learning that can be applied across all subjects and age groups.

Ultimately, the success of Learning Fundamentals depends on consistent implementation and a whole-school approach. When all teachers use the same language and strategies, students internalise the fundamentals and apply them automatically. By making learning visible and helping students to take control, we can create a culture of learning that supports all students to achieve their full potential.

To begin implementing these evidence-based strategies immediately, select one fundamental that resonates most with your current teaching challenges. For instance, if student engagement is a concern, focus specifically on incorporating active learning techniques such as think-pair-share activities or brief collaborative problem-solving sessions. Document what works well and what requires adjustment, creating a personalised toolkit of effective teaching strategies.

Building a supportive network of colleagues can accelerate your professional development in applying these learning fundamentals. Regular discussions with fellow educators about classroom practice provide valuable insights and fresh perspectives on common challenges. Consider establishing informal peer observations or professional learning communities focused on evidence-based teaching methods. This collaborative approach not only strengthens your own teaching but contributes to improved student outcomes across your entire educational setting.

Remember that sustainable change in classroom practice occurs through consistent, small steps rather than dramatic overhauls. Celebrate incremental improvements and remain patient as you develop confidence with new approaches. The investment in mastering these learning fundamentals will ultimately transform both your teaching effectiveness and your students' educational experience, creating lasting positive impact in your professional practice.

For those interested in examining deeper into the research underpinning Learning Fundamentals, the following resources offer valuable insights:

Learning Fundamentals matter because they shift focus from what teachers do to what students actually do during learning, which determines outcomes. Unlike complex frameworks that overwhelm teachers, these fundamentals provide simple, learnable behaviours that students can understand and apply themselves. This learner-centered approach enables students to take ownership of their learning processes, reducing anxiety and improving engagement.

Schools are inundated with frameworks, taxonomies, and research summaries. Each offers valuable insights, but their complexity often prevents implementation. Teachers recognise the value of Rosenshine's Principles or Bloom's Taxonomy yet struggle to translate these frameworks into daily classroom practice.

Learning Fundamentals take a different approach. Rather than describing what effective teachers do (teacher-centred frameworks), they describe what effective learners do (learner-centred fundamentals). This shift matters because ultimately, learning happens in students' minds. The most brilliant explanation produces no learning if students do not engage cognitively with it.

By focusing on learnable student behaviours expressed in simple language, Learning Fundamentals become accessible to students themselves, not just teachers. When students understand what effective learning looks like, they can take ownership of their own learning processes, reducing student anxiety and enabling them to engage more effectively, which significantly impacts student motivationand their cognitive processes.

Effective learners do not immediately begin tasks. They pause to consider what the task requires, what they already know that might help, and what approach might work best. This metacognitive step, though brief, significantly improves outcomes.

Research on problem-solving consistently shows that experts spend more time understanding problems before attempting solutions, while novices dive in immediately. Teaching students to plan, even briefly, builds this expert habit. This approach aligns with systems theory principles that emphasise understanding interconnected learning processes. Questions like "What do I need to find out?" and "What do I already know about this?" prompt the planning process.

Planning also involves monitoring: checking whether the chosen approach is working and adjusting if necessary. Students who plan tend to notice when they are stuck earlier and are more willing to try alternative strategies, which supports both academic success and student wellbeing.

Information presented in organised structures is easier to understand and remember than disconnected facts. Effective learners actively organise information, creating hierarchies, categories, timelines, or other structures that reveal relationships.

Organisation requires decisions about what belongs together and what differs, which features are central and which are peripheral. These decisions force engagement with meaning rather than surface features. A student organising historical events into causes and consequences is processing more deeply than one listing dates chronologically.

Teaching organisation involves making structural thinking visible: concept maps, tables comparing features, hierarchical outlines, and other graphic organisers externalise the mental work of organisation so it can be taught and practised.

Isolated facts are hard to remember and impossible to apply. Understanding comes from seeing how ideas relate to each other and to what you already know. Effective learners actively seek connections.

Connections operate at multiple levels. Within a topic, students connect new examples to general principles. Across topics, they notice when concepts from one area apply to another. Beyond school, they connect academic learning to their own experience and observations.

Teachers can prompt connecting through questions: "How does this relate to what we learned last week?" "Where have you seen something like this before?" "What would happen if we applied this idea to that situation?" Over time, students internalise these prompts and ask such questions themselves.

Articulating thinking, whether to others or to oneself, clarifies and strengthens understanding. The act of putting thoughts into words reveals gaps and forces precision. Students who can explain an idea to someone else understand it more deeply than those who merely recognise it.

Talk also serves social purposes. Discussing ideas with peers exposes students to different perspectives and requires them to defend or revise their understanding. Collaborative sense-making often produces better outcomes than individual study.

The emphasis on talk before writing is deliberate. Students who clarify thinking orally before committing to writing produce better written work and experience less writing anxiety. The phrase "talk first, then write" captures this sequence.

Display the four fundamentals prominently in classrooms. Use the language consistently when setting up activities and when providing feedback. When students succeed, name which fundamental they used effectively. When they struggle, suggest which fundamental might help.

Consistency across the school amplifies impact. When all teachers use the same language, students encounter it frequently enough to internalise it. A common vocabulary for learning becomes part of school culture.

Each fundamental comprises specific strategies that can be modelled and practised. Planning might involve underlining key words in questions, sketching a quick diagram, or listing what you know before starting.Strategies for organisation include concept mapping, outlining, and creating tables. Connecting can be taught by prompting students to find analogies or consider alternative perspectives. Articulation can be developed through think-pair-share activities, debates, or presentations.

Encourage students to reflect on their use of the fundamentals. Prompts like "Which fundamental did I use most effectively today?" or "Which fundamental do I need to focus on tomorrow?" help students become more aware of their learning processes. Students can also set goals related to specific fundamentals, such as "I will plan for five minutes before starting my next assignment."

Effective assessment transforms from a judgement tool into a powerful learning accelerator when it aligns with fundamental learning principles. Dylan Wiliam's research on formative assessment demonstrates that strategic feedback can produce learning gains equivalent to r educing class sizes by half, yet only when assessment directly connects to students' current understanding and next steps. Rather than simply measuring what students know, assessment that supports learning fundamentals actively diagnoses misconceptions, reveals thinking processes, and guides both teacher instruction and student self-regulation.

The timing and nature of feedback proves crucial for maximising learning outcomes. John Hattie's synthesis reveals that feedback works best when it answers three fundamental questions: Where am I going? How am I doing? Where to next? This approach shifts assessment from retroactive grading towards real-time learning support. Students need immediate, specific feedback during skill acquisition, whilst delayed feedback proves more effective for retention and transfer tasks. Quality feedback focuses on the task and process rather than personal praise, helping students develop accurate self-assessment capabilities.

Practical classroom implementation centres on making student thinking visible through low-stakes assessment strategies. Exit tickets, mini whiteboards, and structured peer feedback create continuous assessment loops that inform immediate teaching adjustments. These approaches reduce cognitive load whilst providing rich diagnostic information, enabling teachers to address learning gaps before they compound and students to develop metacognitive awareness of their own learning progress.

Effective differentiation begins with understanding that learning fundamentals remain constant whilst delivery methods must flex. Vygotsky's concept of the Zone of Proximal Development illustrates why one-size-fits-all approaches fail: students operate at different developmental stages simultaneously within the same classroom. This means core principles like clear explanations, guided practice, and feedback loops apply universally, but their implementation requires careful calibration to individual cognitive capacity and prior knowledge.

For SEND students and varying ability levels, cognitive load theory becomes particularly crucial. John Sweller's research demonstrates that learners have limited working memory capacity, suggesting teachers must reduce extraneous cognitive burden through strateg ic scaffolding. This might involve breaking complex tasks into smaller steps for some students whilst providing extension challenges for others, all whilst maintaining the same fundamental learning objectives across the class.

Practical differentiation centres on flexible grouping and multiple means of representation. Consider offering visual, auditory, and kinaesthetic pathways to the same content, allowing students to access learning through their strongest channels. Use formative assessment data to create dynamic groups that change based on specific learning needs rather than fixed ability labels. This approach ensures every student receives appropriate challenge whilst building towards shared learning goals.

Understanding the cognitive science behind learning fundamentals transforms teaching from intuition to informed practice. John Sweller's cognitive load theory demonstrates how our working memory can only process limited information simultaneously, explaining why breaking complex concepts into manageable chunks proves so effective. Meanwhile, Hermann Ebbinghaus's research on the forgetting curve reveals that students lose approximately 50% of new information within hours unless it's reinforced, highlighting the critical importance of spaced practice and retrieval opportunities.

Rosenshine's principles of instruction, derived from extensive classroom research, show that explicit teaching followed by guided practice consistently produces superior student outcomes compared to discovery-based approaches alone. This aligns with cognitive science findings that novice learners benefit from direct instruction whilst building foundational knowledge, whereas expert learners can handle more open-ended exploration once they've developed robust mental schemas.

In practical terms, this research evidence suggests structuring lessons with clear learning objectives, modelling new concepts explicitly, providing immediate feedback, and incorporating regular low-stakes retrieval practice. Rather than overwhelming students with too much information at once, effective t eachers sequence learning carefully, building complexity gradually whilst ensuring each step is thoroughly understood before progressing.

Learning Fundamentals offer a practical and accessible framework for improving student learning. By focusing on learnable student behaviours and using simple, consistent language, teachers can helps students to take ownership of their learning. The four fundamentals, Plan, Organise, Connect, and Talk, provide a common language for learning that can be applied across all subjects and age groups.

Ultimately, the success of Learning Fundamentals depends on consistent implementation and a whole-school approach. When all teachers use the same language and strategies, students internalise the fundamentals and apply them automatically. By making learning visible and helping students to take control, we can create a culture of learning that supports all students to achieve their full potential.

To begin implementing these evidence-based strategies immediately, select one fundamental that resonates most with your current teaching challenges. For instance, if student engagement is a concern, focus specifically on incorporating active learning techniques such as think-pair-share activities or brief collaborative problem-solving sessions. Document what works well and what requires adjustment, creating a personalised toolkit of effective teaching strategies.

Building a supportive network of colleagues can accelerate your professional development in applying these learning fundamentals. Regular discussions with fellow educators about classroom practice provide valuable insights and fresh perspectives on common challenges. Consider establishing informal peer observations or professional learning communities focused on evidence-based teaching methods. This collaborative approach not only strengthens your own teaching but contributes to improved student outcomes across your entire educational setting.

Remember that sustainable change in classroom practice occurs through consistent, small steps rather than dramatic overhauls. Celebrate incremental improvements and remain patient as you develop confidence with new approaches. The investment in mastering these learning fundamentals will ultimately transform both your teaching effectiveness and your students' educational experience, creating lasting positive impact in your professional practice.

For those interested in examining deeper into the research underpinning Learning Fundamentals, the following resources offer valuable insights:

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/learning-fundamentals#article","headline":"Learning Fundamentals: Core Principles Every Teacher Should Know","description":"Master the fundamental principles of how learning works. Understand cognitive load, memory, attention, and the science that underpins effective teaching...","datePublished":"2022-03-14T18:39:33.261Z","dateModified":"2026-01-26T10:09:32.212Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/learning-fundamentals"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/696a149a6f3f9e4e8140ebfc_696a14997de493f6a7b805ec_learning-fundamentals-infographic.webp","wordCount":1531},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/learning-fundamentals#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"Learning Fundamentals: Core Principles Every Teacher Should Know","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/learning-fundamentals"}]}]}