Productive Failure in Education: What Teachers Need to Know

Productive failure in education involves letting pupils struggle with complex problems before instruction to improve deep learning and knowledge transfer.

Productive failure in education involves letting pupils struggle with complex problems before instruction to improve deep learning and knowledge transfer.

Direct Instruction: Flipping the Script infographic for teachers" loading="lazy">

Direct Instruction: Flipping the Script infographic for teachers" loading="lazy">

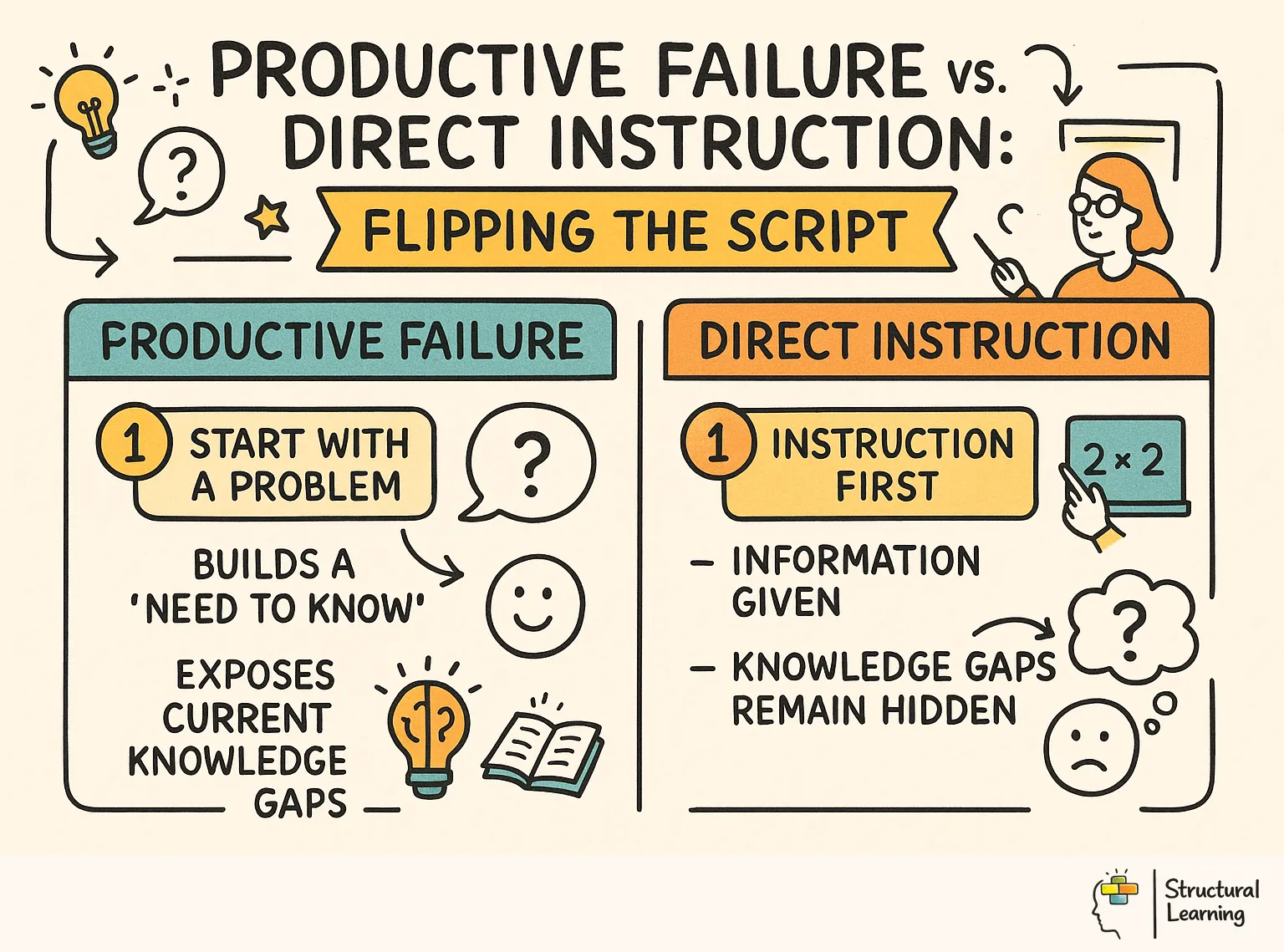

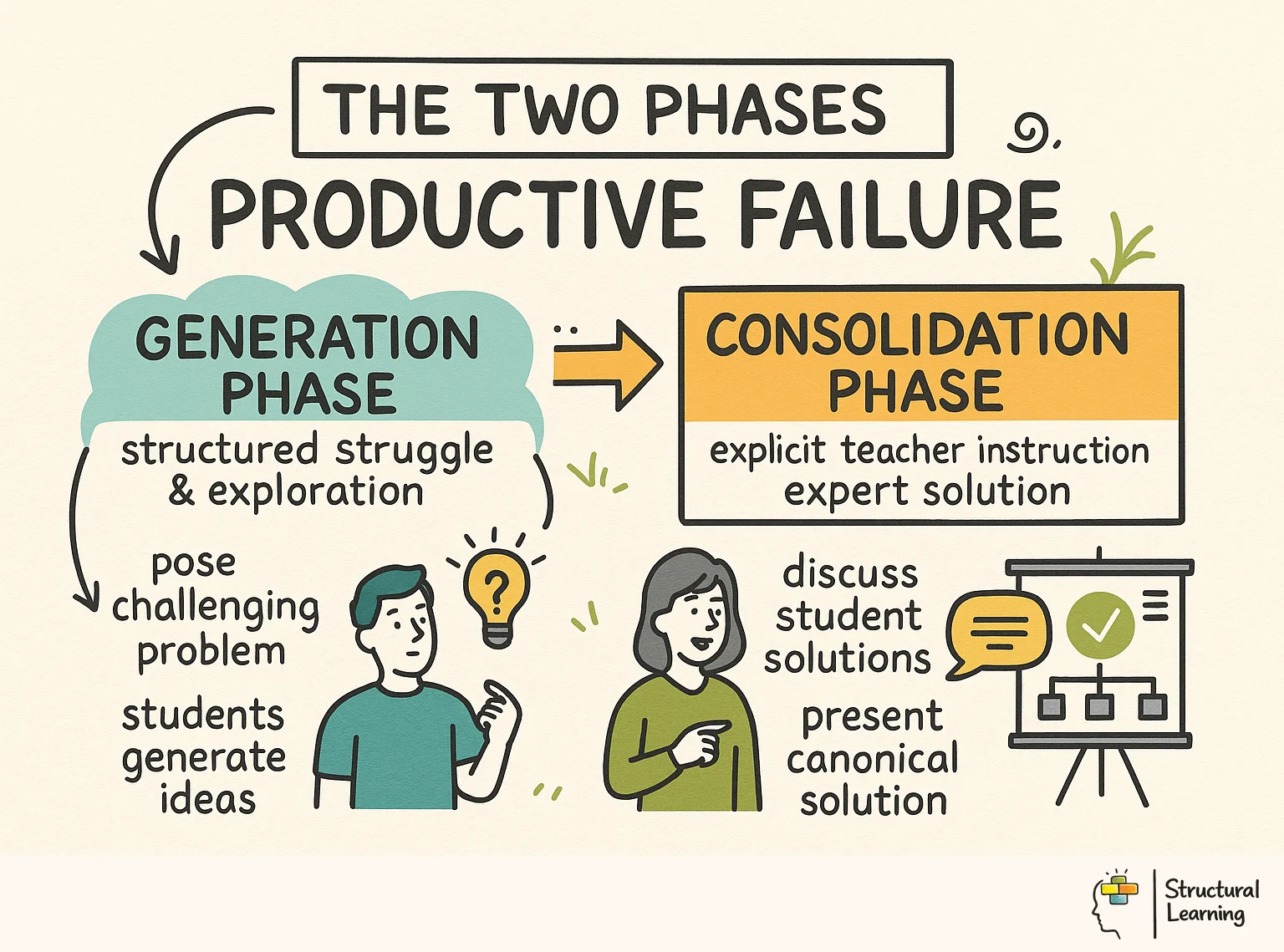

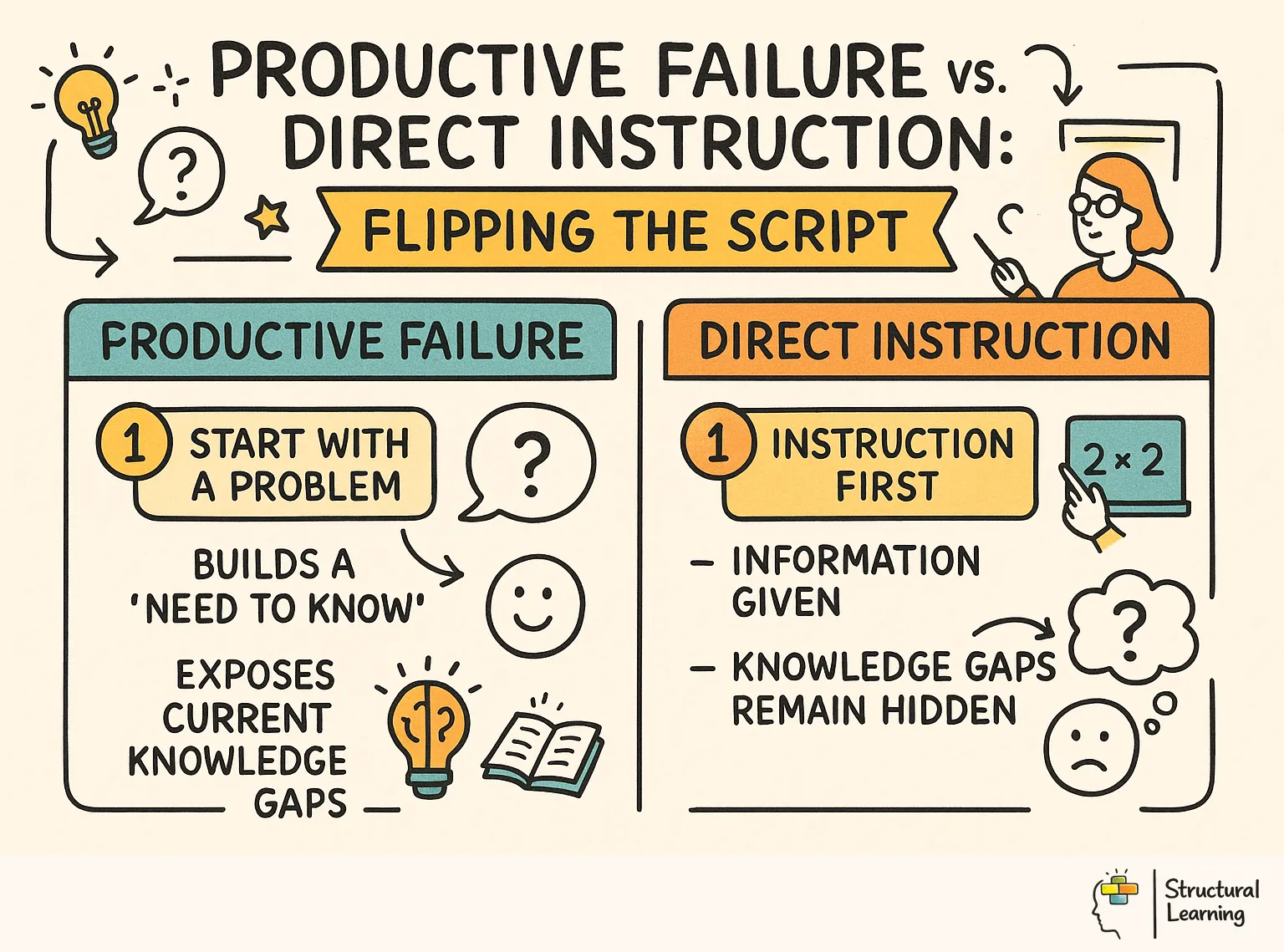

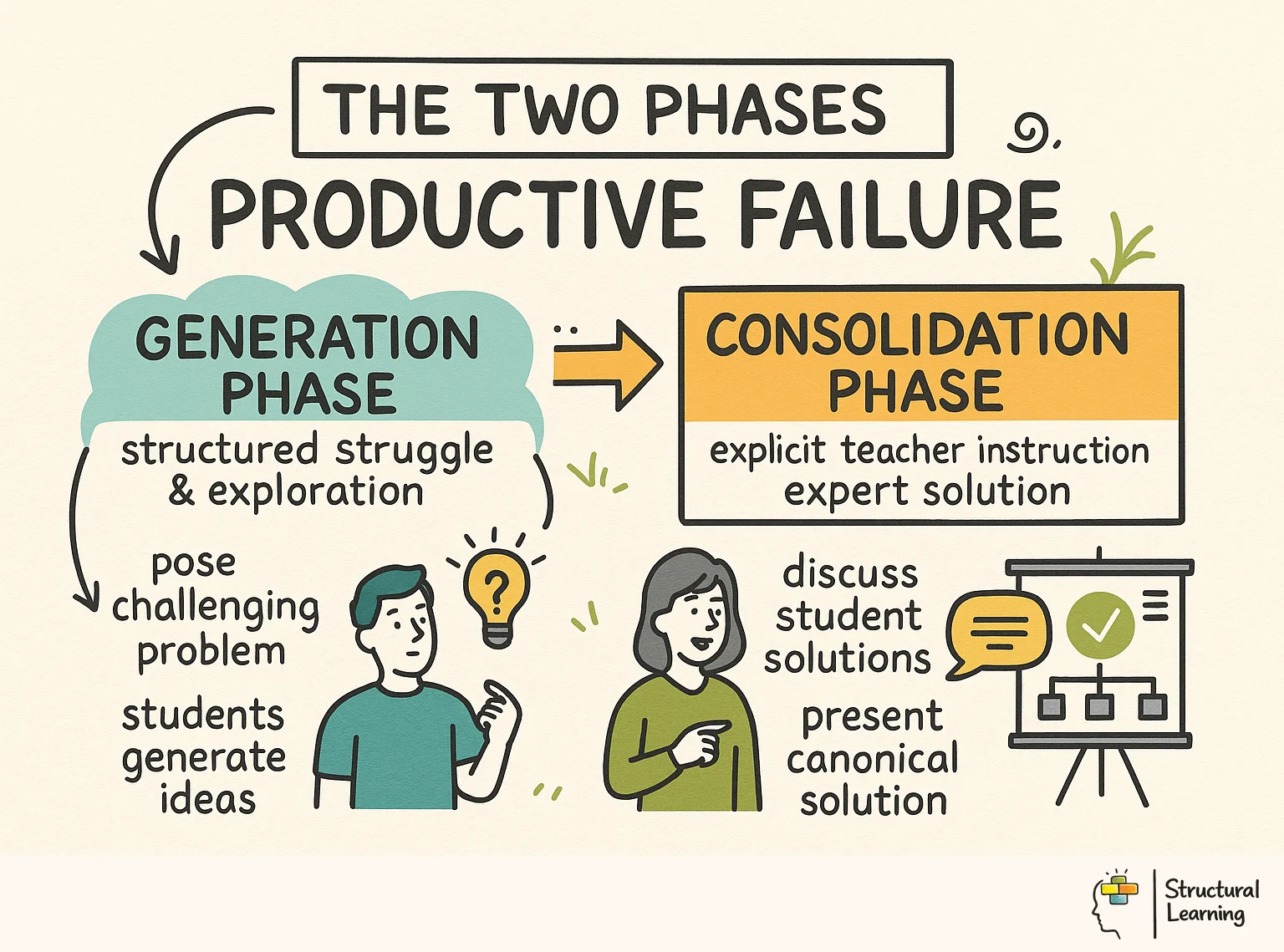

Productive failure in education is a learning design that deliberately sequences a problem-solving phase before an instruction phase. Pupils tackle a complex, novel problem that they are unlikely to solve correctly using their existing knowledge. The primary goal is the cognitive processes triggered during the attempt rather than a correct answer. This initial stage is the generation phase.

For example, a teacher might ask pupils to calculate the area of a circle before providing the formula. Pupils might try to fill the circle with squares or divide it into triangles. This struggle makes the eventually provided formula more memorable.

Manu Kapur developed the concept as an alternative to the idea that direct instruction must always come first. Kapur (2008) argued that by allowing pupils to struggle with a concept, they become aware of the limitations of their current strategies. This awareness creates a need to know that makes the subsequent instruction more meaningful. When the teacher finally explains the correct method, pupils have already built the mental scaffolding necessary to hang that new information on.

This approach addresses a common problem in teaching known as the illusion of competence. When a teacher provides a worked example first, pupils often follow the steps without understanding the underlying logic. They may succeed in the short term but fail to apply the knowledge in different contexts. Productive failure prioritises long-term retention and the ability to transfer skills to new situations.

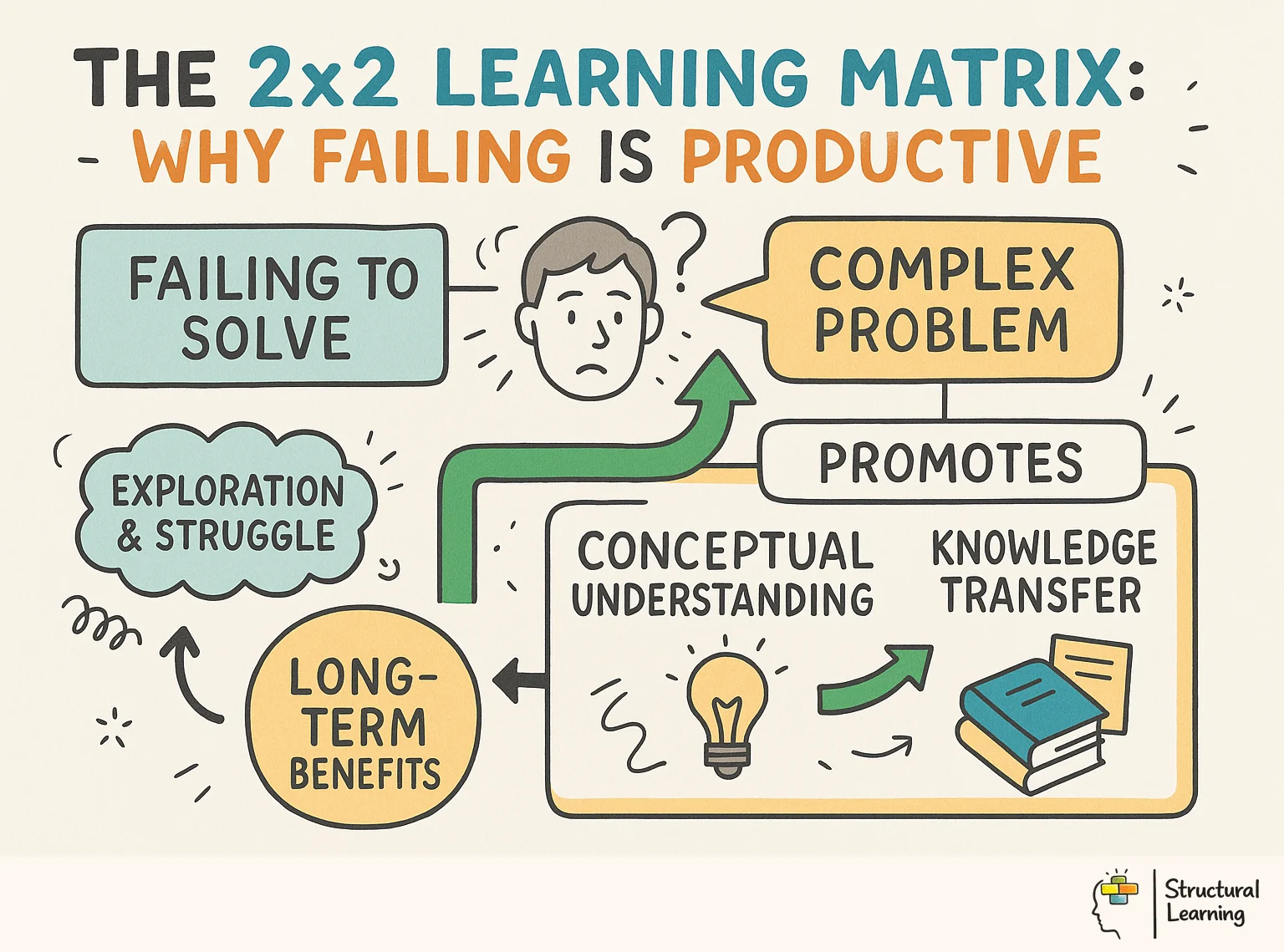

Studies comparing it to traditional instruction first models provide evidence for productive failure. Kapur and Kinzer (2009) conducted experiments in secondary school mathematics focusing on complex problems like standard deviation. They found that while the direct instruction group performed better on simple tasks, the productive failure group significantly outperformed them on conceptual understanding. This evidence suggests that the struggle itself is a catalyst for deeper cognitive engagement.

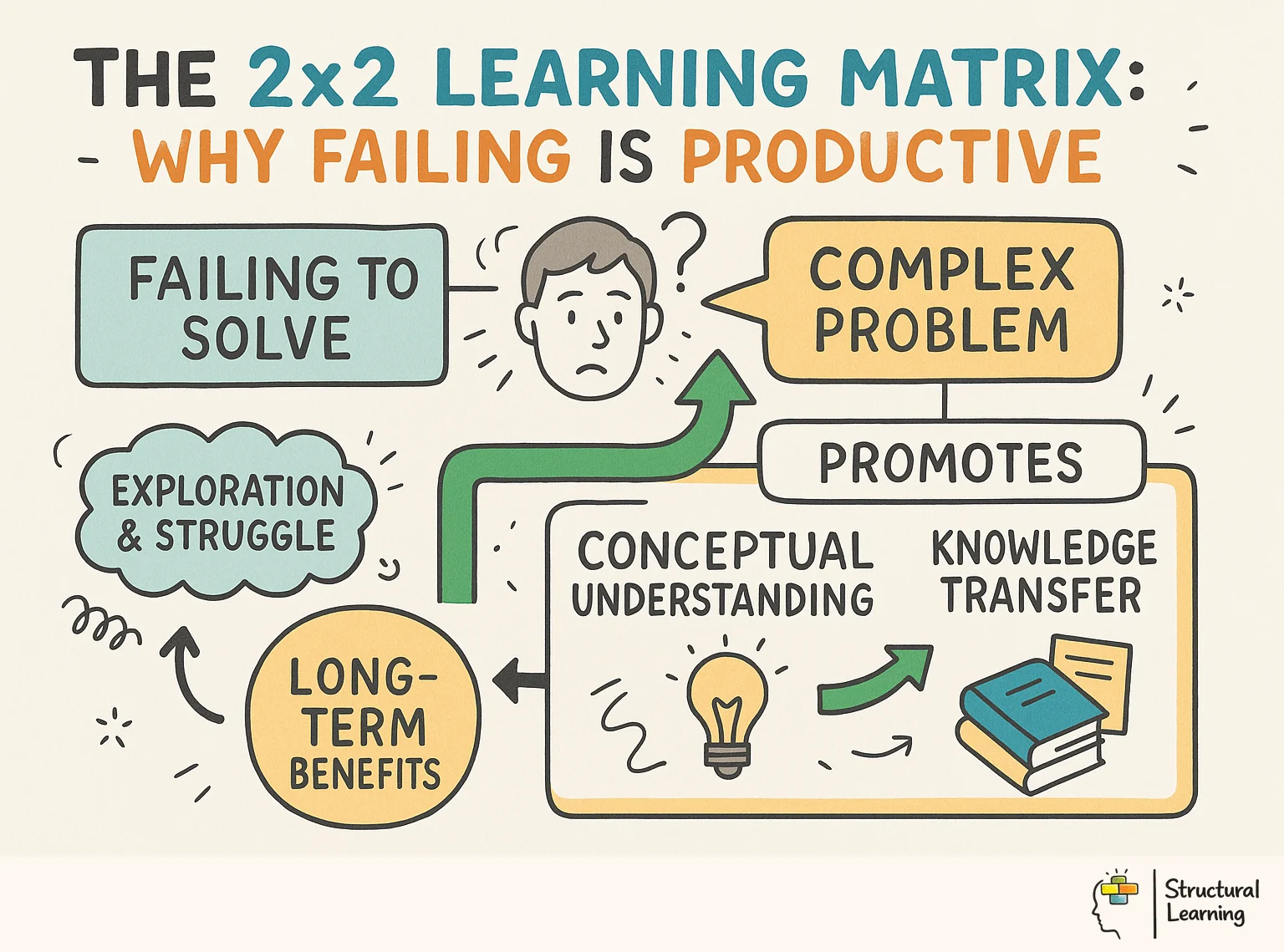

Manu Kapur developed a 2x2 matrix to help teachers understand these outcomes. The matrix categorises lessons based on performance in both the generation and consolidation phases. Productive failure occurs when pupils struggle with the initial task but achieve high conceptual understanding later. This differs from unproductive success, where pupils solve a problem quickly but fail to learn the underlying principles (Kapur, 2012).

Kapur (2016) examined several decades of research into problem-solving before instruction. The results indicated that for conceptual learning, the productive failure model was consistently superior to models where instruction preceded practise. Researchers found that the generation effect is a powerful psychological mechanism. When pupils generate their own solutions, they engage in more elaborate encoding than when they simply receive a correct answer (Loibl et al., 2017).

Teachers must shift from being providers of answers to designers of challenges. Teachers expect and value failure as a source of data. The following strategies provide a framework for using this concept across different year groups and subjects.

In this strategy, the teacher presents a complex problem at the start of the lesson before any formal explanation. The teacher does not give hints or show methods; instead, they encourage pupils to use whatever logic or prior knowledge they possess. Pupils might work in pairs to brainstorm possible solutions, even if they know their methods are flawed. For example, in a Year 8 Geography lesson about population density, the teacher might give pupils a map of an imaginary island and ask them to calculate where to build a city.

The teacher says, "I want you to try and figure out a way to measure which area is the most crowded. I haven't shown you the formula yet, so I want to see how you would invent your own way to show crowdedness." Pupils might draw dots, use ratios, or create their own scoring systems. This process activates their prior knowledge of space and numbers. When the teacher later introduces the standard formula for population density, pupils immediately see how it improves upon or confirms their own messy attempts.

This strategy focuses on the comparison between pupil-generated ideas and the expert method. After the initial struggle, the teacher collects several examples of pupil work, anonymises them, and displays them to the class. The teacher then introduces the canonical solution. The pupils must then compare their non-canonical attempts with the expert model. They look for what worked, what didn't, and why the expert model is more efficient or accurate.

In a Year 10 Physics lesson on electrical circuits, the teacher asks pupils to design a way to make three bulbs light up with equal brightness using one battery. Pupils might produce various series and parallel designs, some of which will fail. The teacher shows a successful pupil design alongside a standard parallel circuit diagram. Pupils discuss the differences in electron flow between their designs and the diagram. This comparison helps pupils understand the why behind the physics, rather than just memorising a circuit symbol.

To ensure failure is productive, teachers must manage four cognitive mechanisms: Activation, Awareness, Affect, and Assembly. The teacher provides a task that is simple enough to start but complex enough to fail. They ensure pupils are aware of their knowledge gaps without becoming demoralised. Finally, they help pupils assemble the new knowledge by linking the instruction to the initial attempt.

In a Year 6 English lesson on persuasive writing, the teacher gives pupils a letter written by a child asking for a later bedtime. The teacher says, "This letter isn't working very well. Try to rewrite it to be more convincing, but you can only change five sentences." Pupils struggle to decide which changes have the most impact. After ten minutes, the teacher introduces rhetorical devices like the rule of three or emotive language. Pupils then assemble these new tools by applying them to the specific sentences they had previously struggled to improve.

Clarifying these ensures the method remains evidence-informed. Some teachers believe productive failure is about letting pupils find the answer entirely on their own. This is incorrect. Pure discovery learning often fails because it lacks guidance and can lead to pupils encoding misconceptions (Mayer, 2004). Productive failure always includes a high-quality, explicit instruction phase.

A teacher might worry that failure will demotivate a Year 4 class during a science experiment on friction. To prevent this, the teacher frames the task as a puzzle to solve rather than a test to pass. This framing ensures pupils focus on the process of discovery rather than the anxiety of getting the wrong answer. The goal is the cognitive activation that happens during the struggle.

The expertise reversal effect (Sweller, 2007) suggests that what works for novices does not always work for experts. Pupils who are completely new to a domain may find productive failure too taxing for their working memory. It is often most effective when pupils have some basic components of knowledge but have not yet seen how to combine them. Teachers should use more direct instruction for absolute beginners and move towards productive failure as pupils gain foundational understanding.

These examples show how the generation and consolidation phases interact across different disciplines.

In a Year 9 Maths lesson, the teacher wants to teach the concept of standard deviation. Instead of giving the formula, the teacher presents exam results for two different classes. Both classes have the same average score, but Class A scores are close together while Class B scores are spread out. The teacher asks, "How can we create a number that tells us how spread out the scores are?"

Pupils work for fifteen minutes using their own logic. One pair tries subtracting the lowest score from the highest. Another pair tries measuring how far each score is from the average. The teacher then shows the formula for standard deviation and explains how it calculates the average distance from the mean. Pupils look at their own attempts and realise their distance from mean idea was the foundation of this complex formula.

In a Year 11 Biology lesson, the teacher provides a diagram of a population of beetles on a dark background. Some beetles are light and some are dark. A predator is present in the environment. The teacher asks, "Over 100 years, what will happen to this population? Write down a step by step process of change."

During the instruction phase, the teacher introduces Darwin’s four steps: Variation, Inheritance, Selection, and Time. The teacher points to a pupil's work that said the light ones get eaten. The teacher explains that the pupil correctly identified selection. The pupils then look at why their idea of deciding to change is different from the biological reality of inheritance.

A Year 7 History teacher wants to explore why the Normans won the Battle of Hastings. Before providing the traditional list of factors, the teacher gives pupils a list of resources and conditions on the day of the battle. They ask pupils to design a battle plan for both William and Harold. Pupils struggle to account for the shield wall and the faked retreat.

When the teacher later tells the story of the battle, pupils are highly attuned to the specific moments where their own battle plans would have failed. They understand the faked retreat as a tactical response to a problem they had just tried to solve themselves. This makes the concept of military leadership as a cause much more concrete.

In Year 10 English, the teacher provides the opening and closing paragraphs of a short story but removes the middle sections. The teacher asks pupils to write a 200-word bridge that connects the two. Pupils struggle to maintain the tone and resolve the conflict established in the opening. They find it difficult to plant the clues needed for the ending.

The teacher then introduces the concept of foreshadowing and structural shifts. They show how the original author used a specific recurring image to bridge the two sections. Pupils compare their own plot points with the author’s subtle use of structure. The struggle to bridge the gap makes them appreciate the craftsmanship of the writer.

Productive failure is supported by several other key concepts in cognitive science.

Cognitive Load Theory (Sweller, 1988) suggests that our working memory is limited. Critics of productive failure worry about extraneous cognitive load. However, proponents argue that by using a structured generation phase, the teacher is actually managing germane cognitive load. The key is ensuring the task is not so open-ended that it leads to cognitive overload.

Robert Bjork (1994) described learning tasks that feel harder and lead to more errors in the short term but result in better long-term retention as desirable difficulties. Productive failure is a prime example of this concept. It forces the brain to work harder during the acquisition phase. This strengthens the neural pathways associated with that concept.

Carol Dweck’s (2006) research on mindset is highly relevant to this model. For productive failure to work, pupils must believe that struggle is a sign of learning. Teachers must explicitly praise the effort and the logic of the failed attempts. This builds resilience and encourages pupils to take the cognitive risks necessary for deep learning.

During the generation phase, pupils are often required to retrieve prior knowledge to solve the new problem. This acts as a form of retrieval practise, which strengthens memory (Karpicke and Roediger, 2008). For instance, a teacher might ask pupils to recall a related concept from a previous term before starting the generation phase. This makes the struggle more focused on the new concept rather than struggling with basic facts.

Productive failure leads to learning because it is followed by high-quality instruction that resolves the struggle. Unproductive failure occurs when a pupil is left to struggle without any eventual explanation. The teacher ensures the failure is a stepping stone to the correct understanding. In a Year 3 maths lesson on symmetry, the teacher prevents frustration by acknowledging the difficulty and explaining that the struggle helps their brains grow stronger.

No, it is significantly different. Discovery learning often lacks a formal instruction phase, whereas productive failure is built around the instruction. In productive failure, the struggle is a deliberate primer for the teacher's explanation. The teacher remains the expert who provides the final, canonical answer.

Avoid this method when pupils have no prior knowledge of the domain, as they will have nothing to activate. It is also less effective for simple procedural tasks, such as learning a list of dates or basic spelling rules. Use it for complex concepts that require deep understanding and the ability to apply knowledge in different ways.

Transparency is key. Tell the pupils that you have given them a problem that you do not expect them to get right yet. Explain that you want to see how their brains try to solve it. By removing the pressure of the correct answer, you reduce anxiety and shift the focus to the process of thinking.

Yes, but the tasks must be appropriately scaled. For a Year 2 class, it might involve trying to figure out how to balance a see-saw with different weights before being taught about pivot points. The generation phase should be shorter, and the instruction phase should be more immediate to match their shorter attention spans.

To implement this in your next lesson, choose one complex concept you are about to teach and give your pupils ten minutes to attempt a problem related to that concept using only their current knowledge.

Direct Instruction: Flipping the Script infographic for teachers" loading="lazy">

Direct Instruction: Flipping the Script infographic for teachers" loading="lazy">

Productive failure in education is a learning design that deliberately sequences a problem-solving phase before an instruction phase. Pupils tackle a complex, novel problem that they are unlikely to solve correctly using their existing knowledge. The primary goal is the cognitive processes triggered during the attempt rather than a correct answer. This initial stage is the generation phase.

For example, a teacher might ask pupils to calculate the area of a circle before providing the formula. Pupils might try to fill the circle with squares or divide it into triangles. This struggle makes the eventually provided formula more memorable.

Manu Kapur developed the concept as an alternative to the idea that direct instruction must always come first. Kapur (2008) argued that by allowing pupils to struggle with a concept, they become aware of the limitations of their current strategies. This awareness creates a need to know that makes the subsequent instruction more meaningful. When the teacher finally explains the correct method, pupils have already built the mental scaffolding necessary to hang that new information on.

This approach addresses a common problem in teaching known as the illusion of competence. When a teacher provides a worked example first, pupils often follow the steps without understanding the underlying logic. They may succeed in the short term but fail to apply the knowledge in different contexts. Productive failure prioritises long-term retention and the ability to transfer skills to new situations.

Studies comparing it to traditional instruction first models provide evidence for productive failure. Kapur and Kinzer (2009) conducted experiments in secondary school mathematics focusing on complex problems like standard deviation. They found that while the direct instruction group performed better on simple tasks, the productive failure group significantly outperformed them on conceptual understanding. This evidence suggests that the struggle itself is a catalyst for deeper cognitive engagement.

Manu Kapur developed a 2x2 matrix to help teachers understand these outcomes. The matrix categorises lessons based on performance in both the generation and consolidation phases. Productive failure occurs when pupils struggle with the initial task but achieve high conceptual understanding later. This differs from unproductive success, where pupils solve a problem quickly but fail to learn the underlying principles (Kapur, 2012).

Kapur (2016) examined several decades of research into problem-solving before instruction. The results indicated that for conceptual learning, the productive failure model was consistently superior to models where instruction preceded practise. Researchers found that the generation effect is a powerful psychological mechanism. When pupils generate their own solutions, they engage in more elaborate encoding than when they simply receive a correct answer (Loibl et al., 2017).

Teachers must shift from being providers of answers to designers of challenges. Teachers expect and value failure as a source of data. The following strategies provide a framework for using this concept across different year groups and subjects.

In this strategy, the teacher presents a complex problem at the start of the lesson before any formal explanation. The teacher does not give hints or show methods; instead, they encourage pupils to use whatever logic or prior knowledge they possess. Pupils might work in pairs to brainstorm possible solutions, even if they know their methods are flawed. For example, in a Year 8 Geography lesson about population density, the teacher might give pupils a map of an imaginary island and ask them to calculate where to build a city.

The teacher says, "I want you to try and figure out a way to measure which area is the most crowded. I haven't shown you the formula yet, so I want to see how you would invent your own way to show crowdedness." Pupils might draw dots, use ratios, or create their own scoring systems. This process activates their prior knowledge of space and numbers. When the teacher later introduces the standard formula for population density, pupils immediately see how it improves upon or confirms their own messy attempts.

This strategy focuses on the comparison between pupil-generated ideas and the expert method. After the initial struggle, the teacher collects several examples of pupil work, anonymises them, and displays them to the class. The teacher then introduces the canonical solution. The pupils must then compare their non-canonical attempts with the expert model. They look for what worked, what didn't, and why the expert model is more efficient or accurate.

In a Year 10 Physics lesson on electrical circuits, the teacher asks pupils to design a way to make three bulbs light up with equal brightness using one battery. Pupils might produce various series and parallel designs, some of which will fail. The teacher shows a successful pupil design alongside a standard parallel circuit diagram. Pupils discuss the differences in electron flow between their designs and the diagram. This comparison helps pupils understand the why behind the physics, rather than just memorising a circuit symbol.

To ensure failure is productive, teachers must manage four cognitive mechanisms: Activation, Awareness, Affect, and Assembly. The teacher provides a task that is simple enough to start but complex enough to fail. They ensure pupils are aware of their knowledge gaps without becoming demoralised. Finally, they help pupils assemble the new knowledge by linking the instruction to the initial attempt.

In a Year 6 English lesson on persuasive writing, the teacher gives pupils a letter written by a child asking for a later bedtime. The teacher says, "This letter isn't working very well. Try to rewrite it to be more convincing, but you can only change five sentences." Pupils struggle to decide which changes have the most impact. After ten minutes, the teacher introduces rhetorical devices like the rule of three or emotive language. Pupils then assemble these new tools by applying them to the specific sentences they had previously struggled to improve.

Clarifying these ensures the method remains evidence-informed. Some teachers believe productive failure is about letting pupils find the answer entirely on their own. This is incorrect. Pure discovery learning often fails because it lacks guidance and can lead to pupils encoding misconceptions (Mayer, 2004). Productive failure always includes a high-quality, explicit instruction phase.

A teacher might worry that failure will demotivate a Year 4 class during a science experiment on friction. To prevent this, the teacher frames the task as a puzzle to solve rather than a test to pass. This framing ensures pupils focus on the process of discovery rather than the anxiety of getting the wrong answer. The goal is the cognitive activation that happens during the struggle.

The expertise reversal effect (Sweller, 2007) suggests that what works for novices does not always work for experts. Pupils who are completely new to a domain may find productive failure too taxing for their working memory. It is often most effective when pupils have some basic components of knowledge but have not yet seen how to combine them. Teachers should use more direct instruction for absolute beginners and move towards productive failure as pupils gain foundational understanding.

These examples show how the generation and consolidation phases interact across different disciplines.

In a Year 9 Maths lesson, the teacher wants to teach the concept of standard deviation. Instead of giving the formula, the teacher presents exam results for two different classes. Both classes have the same average score, but Class A scores are close together while Class B scores are spread out. The teacher asks, "How can we create a number that tells us how spread out the scores are?"

Pupils work for fifteen minutes using their own logic. One pair tries subtracting the lowest score from the highest. Another pair tries measuring how far each score is from the average. The teacher then shows the formula for standard deviation and explains how it calculates the average distance from the mean. Pupils look at their own attempts and realise their distance from mean idea was the foundation of this complex formula.

In a Year 11 Biology lesson, the teacher provides a diagram of a population of beetles on a dark background. Some beetles are light and some are dark. A predator is present in the environment. The teacher asks, "Over 100 years, what will happen to this population? Write down a step by step process of change."

During the instruction phase, the teacher introduces Darwin’s four steps: Variation, Inheritance, Selection, and Time. The teacher points to a pupil's work that said the light ones get eaten. The teacher explains that the pupil correctly identified selection. The pupils then look at why their idea of deciding to change is different from the biological reality of inheritance.

A Year 7 History teacher wants to explore why the Normans won the Battle of Hastings. Before providing the traditional list of factors, the teacher gives pupils a list of resources and conditions on the day of the battle. They ask pupils to design a battle plan for both William and Harold. Pupils struggle to account for the shield wall and the faked retreat.

When the teacher later tells the story of the battle, pupils are highly attuned to the specific moments where their own battle plans would have failed. They understand the faked retreat as a tactical response to a problem they had just tried to solve themselves. This makes the concept of military leadership as a cause much more concrete.

In Year 10 English, the teacher provides the opening and closing paragraphs of a short story but removes the middle sections. The teacher asks pupils to write a 200-word bridge that connects the two. Pupils struggle to maintain the tone and resolve the conflict established in the opening. They find it difficult to plant the clues needed for the ending.

The teacher then introduces the concept of foreshadowing and structural shifts. They show how the original author used a specific recurring image to bridge the two sections. Pupils compare their own plot points with the author’s subtle use of structure. The struggle to bridge the gap makes them appreciate the craftsmanship of the writer.

Productive failure is supported by several other key concepts in cognitive science.

Cognitive Load Theory (Sweller, 1988) suggests that our working memory is limited. Critics of productive failure worry about extraneous cognitive load. However, proponents argue that by using a structured generation phase, the teacher is actually managing germane cognitive load. The key is ensuring the task is not so open-ended that it leads to cognitive overload.

Robert Bjork (1994) described learning tasks that feel harder and lead to more errors in the short term but result in better long-term retention as desirable difficulties. Productive failure is a prime example of this concept. It forces the brain to work harder during the acquisition phase. This strengthens the neural pathways associated with that concept.

Carol Dweck’s (2006) research on mindset is highly relevant to this model. For productive failure to work, pupils must believe that struggle is a sign of learning. Teachers must explicitly praise the effort and the logic of the failed attempts. This builds resilience and encourages pupils to take the cognitive risks necessary for deep learning.

During the generation phase, pupils are often required to retrieve prior knowledge to solve the new problem. This acts as a form of retrieval practise, which strengthens memory (Karpicke and Roediger, 2008). For instance, a teacher might ask pupils to recall a related concept from a previous term before starting the generation phase. This makes the struggle more focused on the new concept rather than struggling with basic facts.

Productive failure leads to learning because it is followed by high-quality instruction that resolves the struggle. Unproductive failure occurs when a pupil is left to struggle without any eventual explanation. The teacher ensures the failure is a stepping stone to the correct understanding. In a Year 3 maths lesson on symmetry, the teacher prevents frustration by acknowledging the difficulty and explaining that the struggle helps their brains grow stronger.

No, it is significantly different. Discovery learning often lacks a formal instruction phase, whereas productive failure is built around the instruction. In productive failure, the struggle is a deliberate primer for the teacher's explanation. The teacher remains the expert who provides the final, canonical answer.

Avoid this method when pupils have no prior knowledge of the domain, as they will have nothing to activate. It is also less effective for simple procedural tasks, such as learning a list of dates or basic spelling rules. Use it for complex concepts that require deep understanding and the ability to apply knowledge in different ways.

Transparency is key. Tell the pupils that you have given them a problem that you do not expect them to get right yet. Explain that you want to see how their brains try to solve it. By removing the pressure of the correct answer, you reduce anxiety and shift the focus to the process of thinking.

Yes, but the tasks must be appropriately scaled. For a Year 2 class, it might involve trying to figure out how to balance a see-saw with different weights before being taught about pivot points. The generation phase should be shorter, and the instruction phase should be more immediate to match their shorter attention spans.

To implement this in your next lesson, choose one complex concept you are about to teach and give your pupils ten minutes to attempt a problem related to that concept using only their current knowledge.

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/productive-failure-education-teachers-need#article","headline":"Productive Failure in Education: What Teachers Need to Know","description":"Productive failure in education involves letting pupils struggle with complex problems before instruction to improve deep learning and knowledge transfer.","datePublished":"2026-02-15T19:58:16.158Z","dateModified":"2026-02-15T20:16:44.331Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/productive-failure-education-teachers-need"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/69922557efa803d345c1fead_699224e66df5bc738d317662_productive-failure-in-educatio-comparison-1771185382439.webp","wordCount":2508},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/productive-failure-education-teachers-need#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"Productive Failure in Education: What Teachers Need to Know","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/productive-failure-education-teachers-need"}]}]}