Mnemonics for Students: A Teacher's Toolkit for Memory Strategies

Mnemonics for students help learners retain complex information through mental shortcuts. Use these evidence-based memory strategies to support long-term retention in your classroom.

Mnemonics for students help learners retain complex information through mental shortcuts. Use these evidence-based memory strategies to support long-term retention in your classroom.

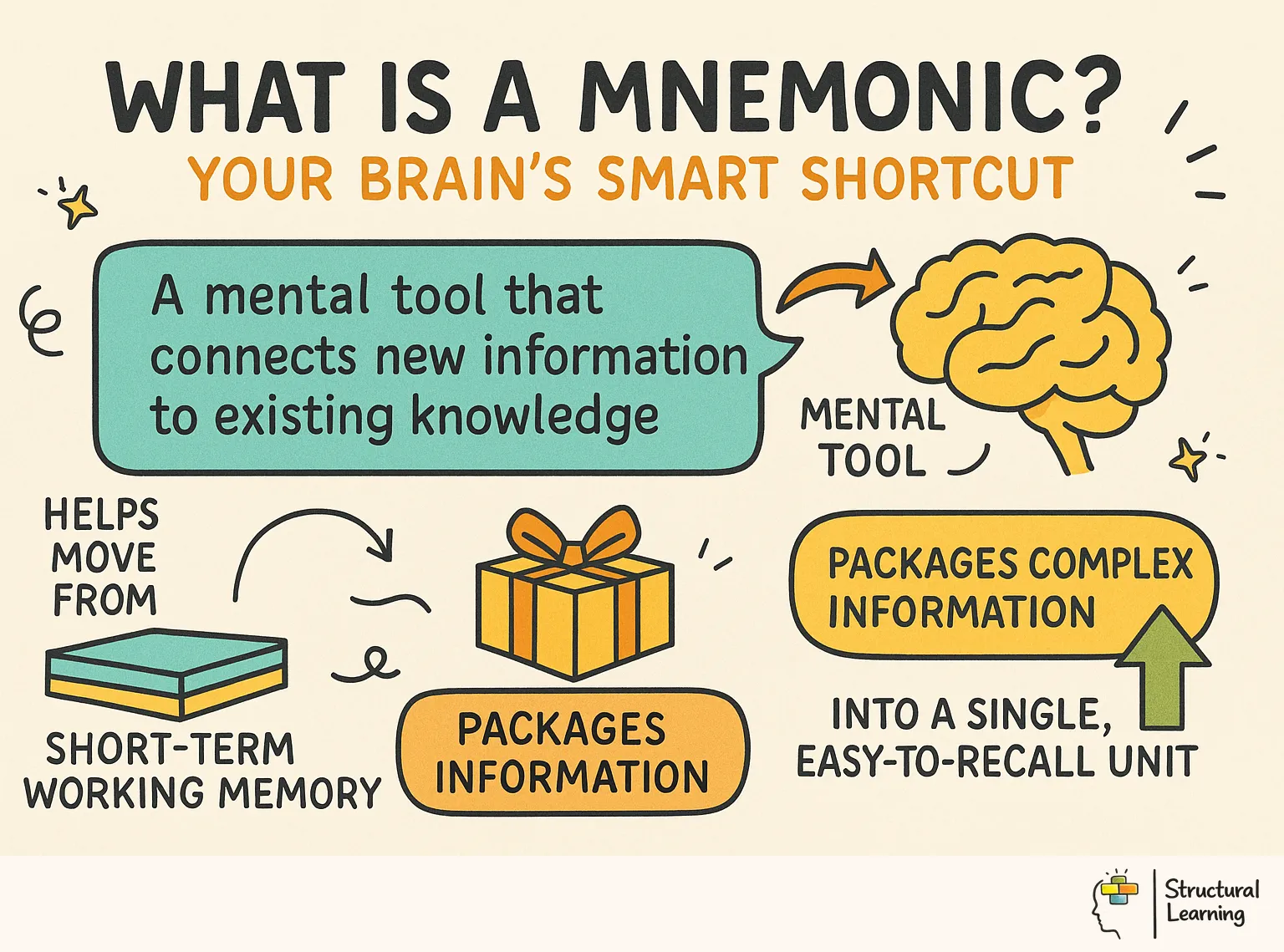

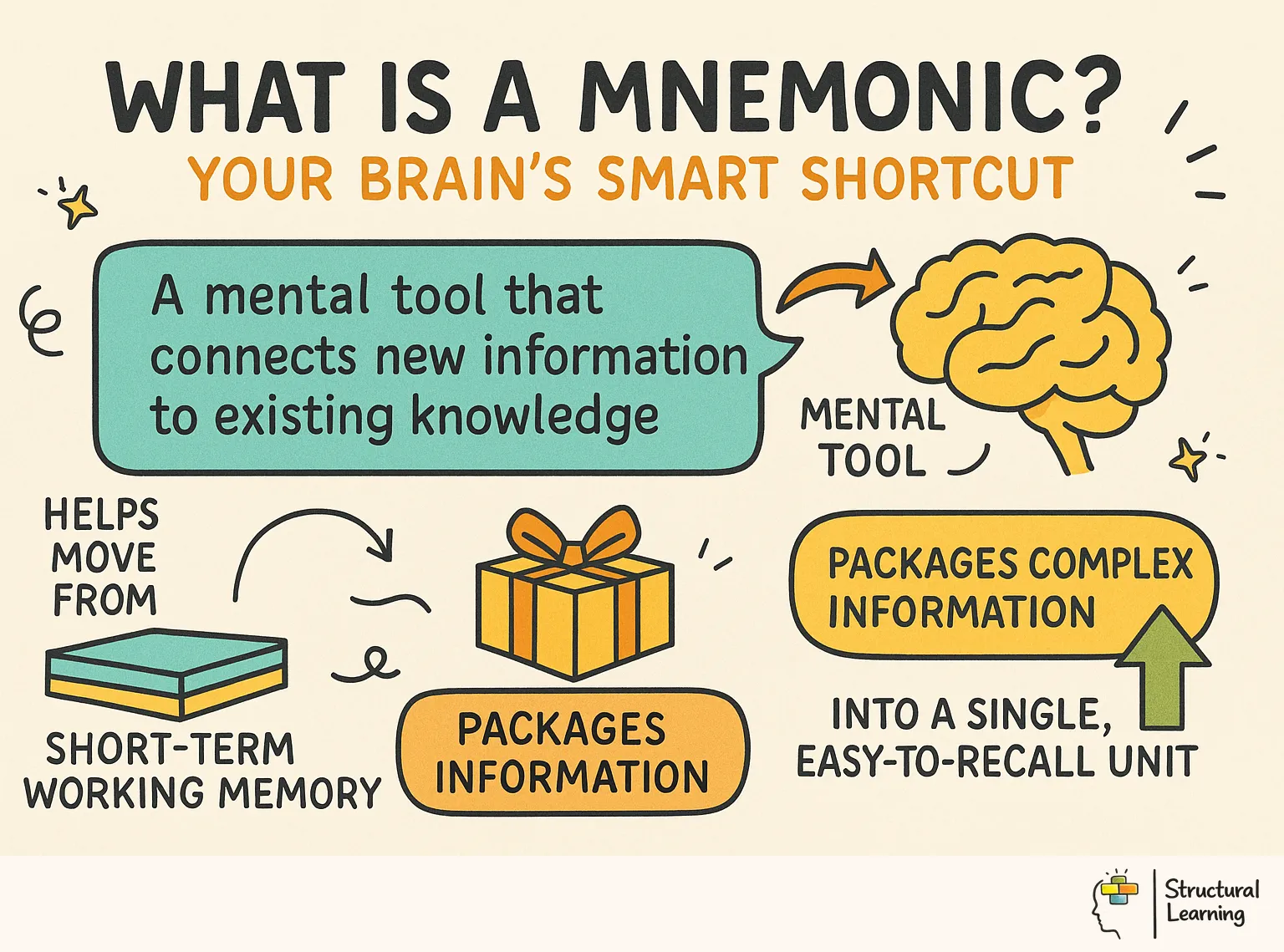

Mnemonics for students are systematic procedures or mental strategies designed to improve memory by connecting new, unfamiliar information to existing knowledge. These techniques create artificial links between items that have no inherent relationship, making them easier to retrieve during exams or classroom activities. The term originates from Mnemosyne, the ancient Greek goddess of memory, reflecting a long history of human attempts to understand the cognitive system.

In a modern classroom, mnemonics serve as mental hooks that allow pupils to bypass the limitations of working memory. Most learners can only hold a small amount of information in their active focus at any one time (Miller, 1956). By using a mnemonic, a student can 'package' several pieces of data into a single, manageable unit. This reduces the mental effort required to recall basic facts, allowing the student to focus on higher-order thinking and problem-solving.

Teachers use these strategies to ensure that foundational knowledge is 'sticky' enough to persist over time. For example, when teaching the order of operations in mathematics, a teacher might introduce the acronym BIDMAS (Brackets, Indices, Division, Multiplication, Addition, Subtraction). The teacher explains that each letter stands for a mathematical operation, and the pupils recite the word 'BIDMAS' while pointing to the corresponding parts of an equation on the board. This simple vocal and physical routine helps the sequence move from short-term awareness into a more stable memory structure.

The effectiveness of mnemonics for students is well documented in cognitive psychology, particularly through the lens of Levels of Processing theory. Craik and Lockhart (1972) argued that the strength of a memory depends on the 'depth' of the encoding process. Mnemonics require students to think about the meaning, sound, or visual properties of a word, which creates a 'deep' memory trace. Instead of passive repetition, the student actively manipulates the information to fit the mnemonic structure.

Dual Coding Theory also provides a strong explanation for why certain mnemonics work so well. Paivio (1971) suggested that the human brain processes verbal and visual information through two separate but interconnected channels. When a student uses a mnemonic that involves both a word and a mental image, they are encoding the information twice. If they forget the word, the visual image may still be available to trigger the retrieval of the linguistic data. This 'double coding' makes the information much more resilient to forgetting.

Research specifically focused on students with learning difficulties has shown that mnemonics can significantly close the attainment gap. Scruggs and Mastropieri (1990) conducted a meta-analysis of mnemonic instruction and found that it consistently outperformed traditional teaching methods for pupils with SEND. Their findings suggest that mnemonics provide the external structure that these students often struggle to create for themselves. By providing a clear retrieval path, teachers can help students with dyslexia or working memory issues feel more successful in academic settings.

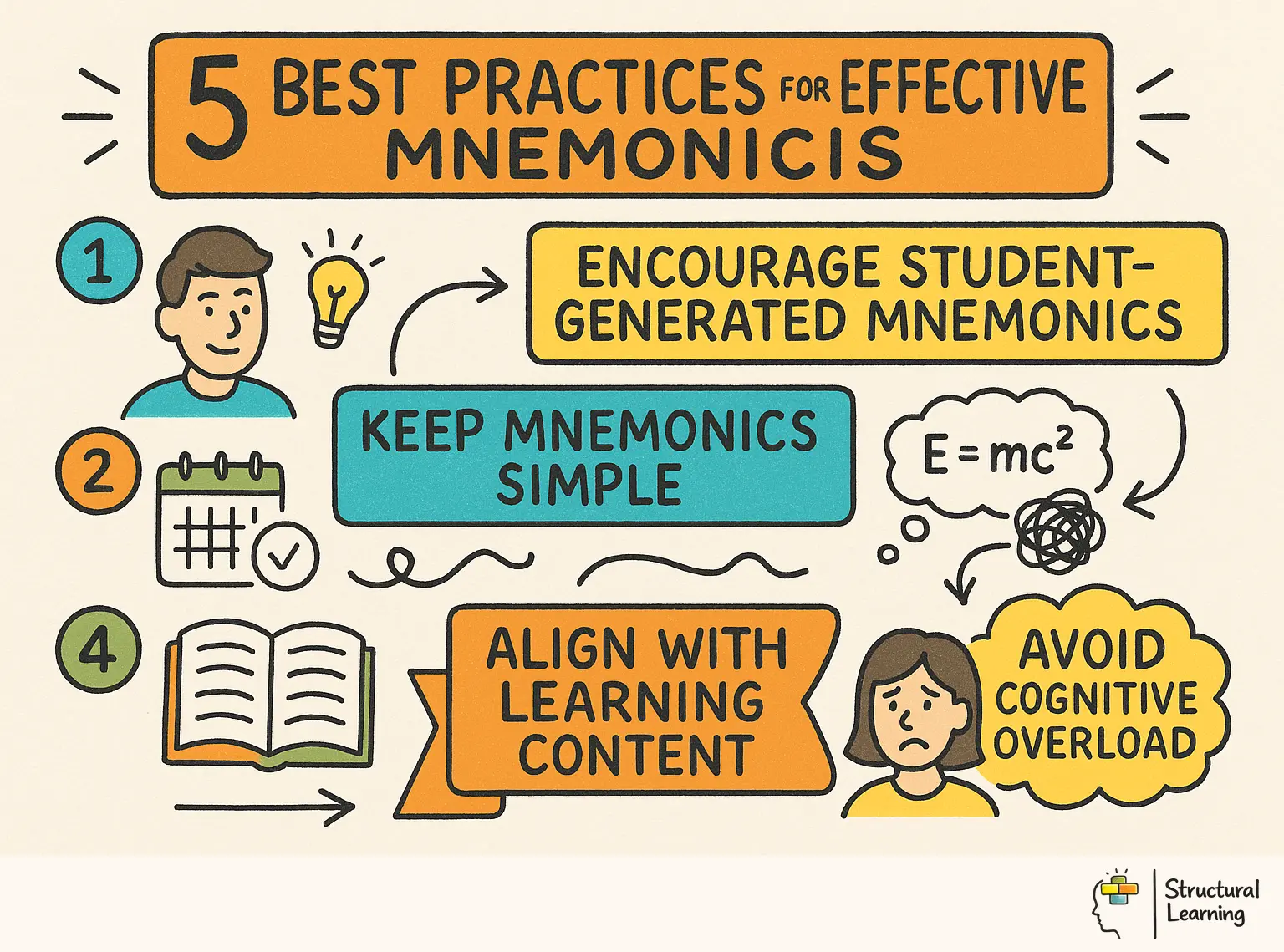

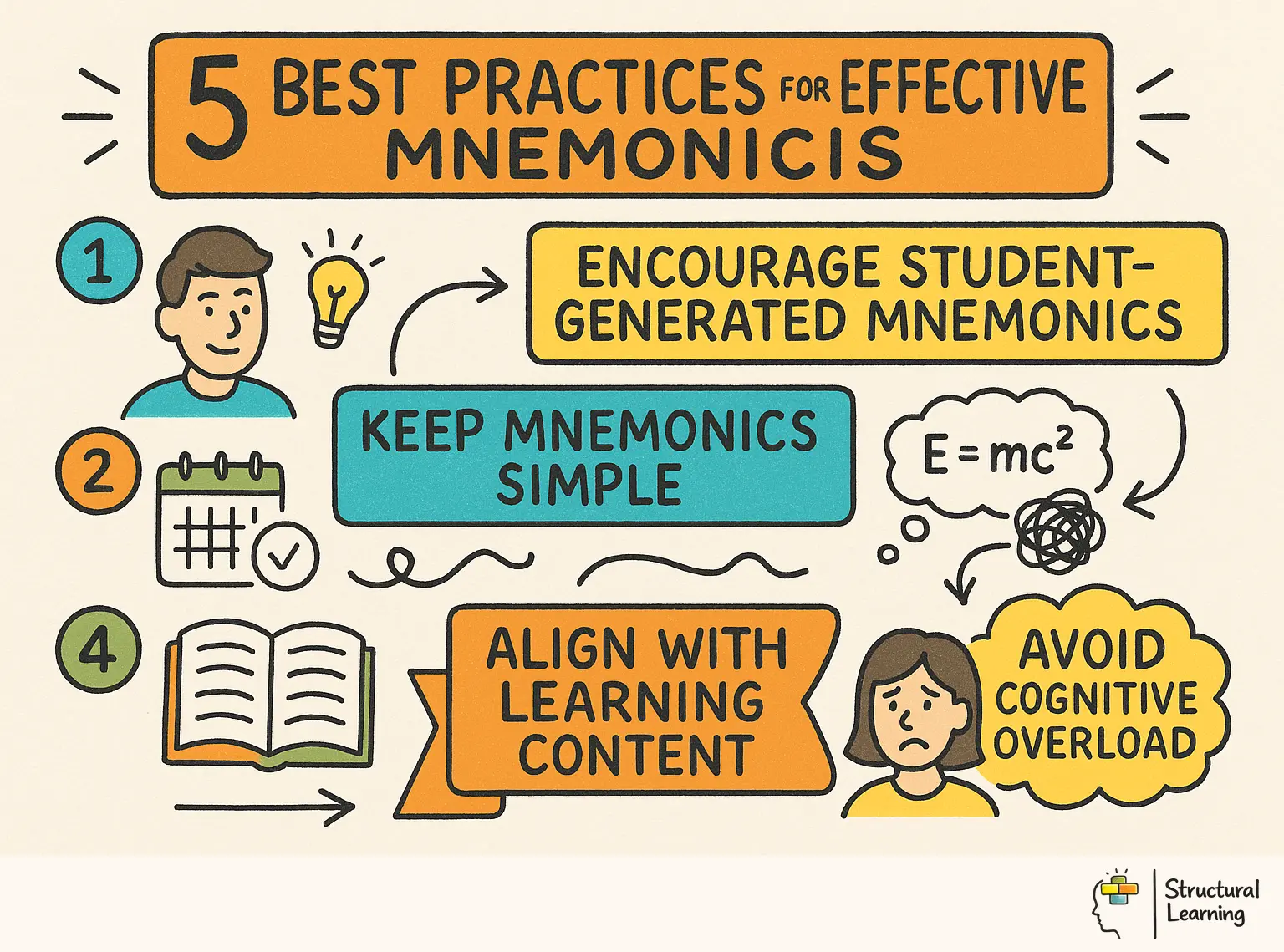

Another critical area of research is the 'Bizarreness Effect', which suggests that unusual or vivid images are easier to remember than mundane ones (Einstein and McDaniel, 1987). When teachers encourage students to create funny or strange acrostics, they are tapping into this cognitive bias. However, some researchers caution that if a mnemonic becomes too elaborate, it can interfere with the learning of the target concept (Sweller, 1988). The goal is to find a balance where the mnemonic is memorable enough to work without becoming a source of extraneous cognitive load.

Implementing mnemonics for students requires more than just sharing a clever phrase; teachers must model how to create, use, and eventually fade these scaffolds as knowledge becomes automated. Each of the following strategies serves a different cognitive purpose and should be selected based on the nature of the content.

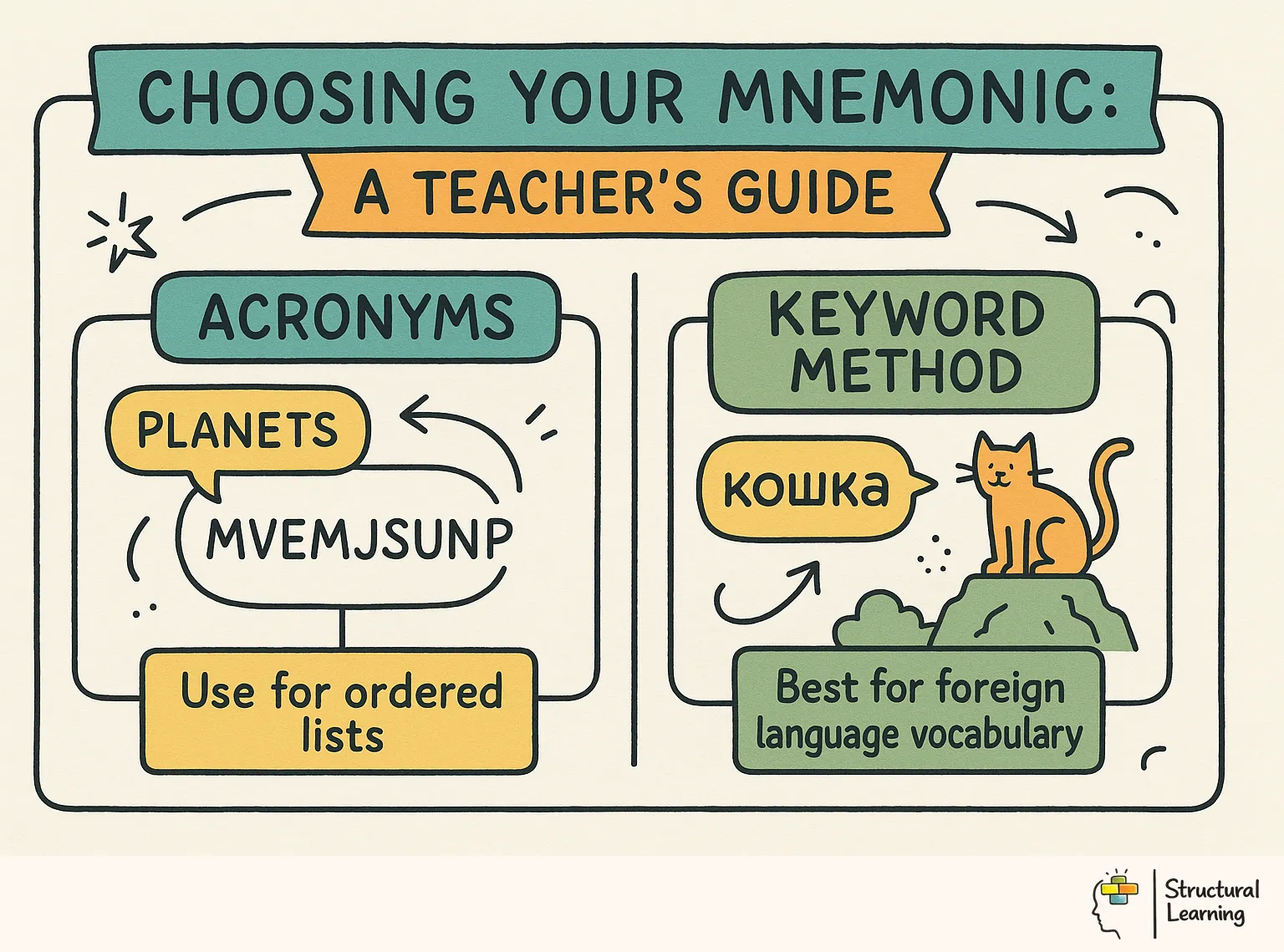

The keyword method is a two-step process designed to help students learn new words, especially in foreign languages or technical science. First, the student identifies a 'keyword' that sounds like the new word but is already familiar. Second, the student creates a mental image that connects the meaning of the new word with the keyword. This creates an acoustic and visual bridge that facilitates rapid recall during lessons.

In a Spanish lesson, the teacher might introduce the word 'Pato', which means duck. The teacher asks the pupils to think of a word that sounds like 'Pato', and a student suggests 'Pot'. The teacher then tells the class to close their eyes and imagine a duck wearing a large, shiny cooking pot on its head like a hat. During the next retrieval quiz, the teacher says 'Pato', the students think of 'Pot', they see the image of the duck, and they correctly translate the word back to English.

Acrostics are sentences where the first letter of each word corresponds to the first letter of the items to be remembered. This technique is particularly useful for sequences that have a fixed order, such as the planets in the solar system or the strings of a guitar. Teachers should encourage students to create their own acrostics, as the personal effort involved in the creative process enhances the initial encoding.

In a Geography lesson, the teacher wants students to remember the order of the points on a compass. Instead of just repeating North, East, South, West, the teacher asks the class to come up with a funny sentence using those letters. A student suggests 'Never Eat Shredded Wheat'. The class laughs, and the teacher writes the sentence on the board, circling the first letter of each word. The pupils then draw a compass in their books and write the 'Never Eat Shredded Wheat' sentence around the outside to anchor the positions.

The pegword method uses rhyming words to create a set of mental 'pegs' on which students can hang new information. The student first learns a standard list of rhymes for the numbers one to ten, such as 'One is a Bun, Two is a Shoe, Three is a Tree'. Once these pegs are permanent, the student can link any new list of items to these images. This is an advanced strategy that works well for remembering the stages of a process or a specific set of rules.

In a Science lesson about the states of matter, the teacher uses pegwords to help students remember the properties of solids. The teacher says, 'Number one is a bun, and a solid has a fixed shape, so imagine a bun that is frozen hard like a rock'. For 'Two is a shoe', the teacher asks students to imagine a solid shoe that does not flow like water. The pupils sketch a frozen bun and a rigid shoe in their margins, labelling them with the properties of solids. This visual association helps them retrieve the characteristics of matter during a structured observation task.

The method of loci, often called a 'memory palace', involves placing items to be remembered along a familiar physical route. This strategy leverages the brain's powerful spatial memory systems. Students imagine walking through their house or school and 'dropping' information at specific locations. This is highly effective for long speeches, the plot of a novel, or the events leading up to a historical conflict.

In a History lesson about the causes of World War I, the teacher asks the students to imagine the school's entrance hall. The teacher says, 'At the front door, we see a giant pile of gunpowder representing the Balkan tensions'. As they move to the reception desk, the teacher tells them to imagine the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand happening right there. The pupils walk through the school building later that day, mentally revisiting each 'hotspot' to practise their recall. The physical movement through the space reinforces the chronological order of the historical events.

Teacher's Guide infographic for teachers" loading="lazy">

Teacher's Guide infographic for teachers" loading="lazy">

One frequent misconception is that mnemonics for students are just a form of 'rote learning' that lacks depth. Critics argue that memorising an acronym like 'Richard Of York Gave Battle In Vain' does not help a student understand the physics of light refraction. While a mnemonic is not a substitute for understanding, it is a tool for providing the 'labels' that allow for deeper discussion. A student cannot explain the formation of a rainbow if they cannot even remember the names of the colours. Research shows that once the basic facts are secure, students have more cognitive capacity to engage with complex concepts (Rosenshine, 2012).

Another myth is that mnemonics are a sign of 'lazy teaching' or that they should only be used as a last resort. Some educators believe that if a concept is taught well enough, students will remember it naturally without the need for 'tricks'. However, even the most profound understanding can be difficult to retrieve under the pressure of an exam. Mnemonics provide a safety net for the retrieval process, ensuring that students can access their knowledge even when they are stressed or tired. They are a legitimate pedagogical tool used by memory experts and high-performing students alike.

A third misconception is that mnemonics for students will work automatically for every learner in the room. In reality, the effectiveness of a mnemonic depends heavily on the student's prior knowledge and cultural background. An acrostic that uses references to a specific television show or hobby might be incredibly memorable for one group but completely meaningless to another. Teachers must ensure that the keywords and images used are accessible to all pupils. If a student has to work too hard to remember the mnemonic itself, the strategy will fail to support the learning of the primary content.

Finally, some teachers believe that mnemonics are only useful for younger primary pupils. While the 'fun' element of mnemonics is often associated with early years education, the cognitive benefits are just as relevant for A-Level and university students. Medical students, for example, famously use complex mnemonics to learn the names of cranial nerves and bones. The complexity of the content simply changes; the underlying need for a retrieval scaffold remains constant as the volume of information increases.

Mnemonics for students look different depending on the discipline. The following examples demonstrate how teachers can adapt these strategies to meet the specific demands of different subject areas.

In Mathematics, students often struggle with the abstract nature of formulas and the sequence of steps required to solve equations. A common mnemonic for trigonometry is SOH CAH TOA, which stands for Sine = Opposite/Hypotenuse, Cosine = Adjacent/Hypothenuse, and Tangent = Opposite/Adjacent.

The teacher introduces this by writing the three 'words' in large letters across the top of the whiteboard. The teacher tells a story about an ancient chief named 'Soh-Cah-Toa' who lived near a triangle-shaped mountain. The pupils then draw a right-angled triangle and label the sides, chanting the chief's name as they identify which ratio to use for a given problem. This verbal anchor prevents the common error of using the wrong trigonometric ratio during independent practise.

Science involves many complex cycles and hierarchies that can easily become confused in a student's mind. To remember the classification of living things (Kingdom, Phylum, Class, Order, Family, Genus, Species), teachers often use the acrostic 'Keep Ponds Clean Or Fish Get Sick'.

During a Biology lesson, the teacher shows a picture of a dirty pond and a sad fish. The teacher says, 'To keep our fish healthy, we must remember the order of classification'. The pupils write the sentence in their books, using a different colour for the first letter of each word. The teacher then gives them a list of specific animals and asks them to 'sort them through the pond', checking each level of the hierarchy against the mnemonic. This provides a clear, step-by-step check that ensures accuracy in their classification work.

In English, mnemonics are useful for mastering 'tricky' spellings and remembering the various components of a persuasive argument. For the word 'Beautiful', many teachers use the phrase 'Big Elephants Are Under Trees In Useless Lakes'.

The teacher writes the word 'BEAUTIFUL' on the board and asks the pupils why it is a difficult word to spell. The students point out the 'eau' vowel string. The teacher then shares the 'Big Elephants' phrase and asks the pupils to draw a picture of a giant elephant sitting under a tree by a lake. Every time the students write the word in their creative writing, they whisper the phrase to themselves. This visual and rhythmic support helps the correct spelling become a permanent part of their writing repertoire.

History students must grapple with long timelines and multiple factors leading to single events. To remember the six wives of Henry VIII in order (Aragon, Boleyn, Seymour, Cleves, Howard, Parr), teachers often use the rhyme 'Divorced, Beheaded, Died, Divorced, Beheaded, Survived'.

The teacher presents a series of portraits of the six wives and asks the students to guess their fates. After the initial discussion, the teacher introduces the rhythmic rhyme, clapping on each word. The pupils then create a 'fate timeline' in their books, matching the rhyme to the names and dates. This auditory pattern acts as a retrieval cue that helps students organise their knowledge of the Tudor period during essay writing.

| Subject | Mnemonic Type | Example | Purpose |

| :--- | :--- | :--- | :--- |

| Maths | Acronym | BIDMAS | Order of Operations |

| Science | Acrostic | MRS GREN | Seven Life Processes (Movement, Respiration, etc.) |

| History | Rhyme | Divorced, Beheaded... | Wives of Henry VIII |

| Geography | Acrostic | Never Eat Shredded Wheat | Compass Points |

| English | Acrostic | AFOREST | Persuasive Devices (Alliteration, Facts, etc.) |

Mnemonics for students do not exist in a vacuum; they are part of a wider ecosystem of cognitive science strategies. Understanding these connections helps teachers use mnemonics more strategically within their lesson planning.

One of the most important links is to Dual Coding. As previously mentioned, mnemonics that combine a verbal cue with a visual image use two different cognitive pathways. When a teacher uses the keyword method, they are essentially creating a dual-coded memory. This increases the number of retrieval paths available to the student, making the information much more accessible during a test. By explicitly linking mnemonics to visual imagery, teachers can make their memory strategies significantly more powerful.

Mnemonics also relate closely to Cognitive Load Theory, developed by John Sweller. This theory suggests that our working memory has a limited capacity, and if we overload it, learning stops. Mnemonics reduce the 'intrinsic' load of a task by 'chunking' information. If a student knows the mnemonic AFOREST (Alliteration, Facts, Opinions, Rhetorical questions, Emotive language, Statistics, Triplets), they do not have to work hard to remember what to include in a persuasive letter. This frees up their 'germane' cognitive load for the much harder task of actually writing the persuasive content.

The use of mnemonics is also a form of Retrieval Practise. Every time a student uses a mnemonic to recall a fact, they are strengthening the neural pathway to that information. However, mnemonics are most effective when they are paired with Spaced Practise. A teacher might introduce a mnemonic in week one, then ask the students to retrieve the information using that mnemonic in week three, week six, and week ten. This 'distributed' retrieval helps move the information from short-term 'scaffolded' memory into permanent long-term storage.

Finally, mnemonics support the development of Metacognition. When students learn how to create their own mnemonics, they are becoming more aware of how their own memory works. They are learning to identify which information is likely to be forgotten and taking proactive steps to prevent that from happening. This 'learning how to learn' is a skill that students can take with them beyond the classroom, applying it to their revision for GCSEs, A-Levels, and future careers.

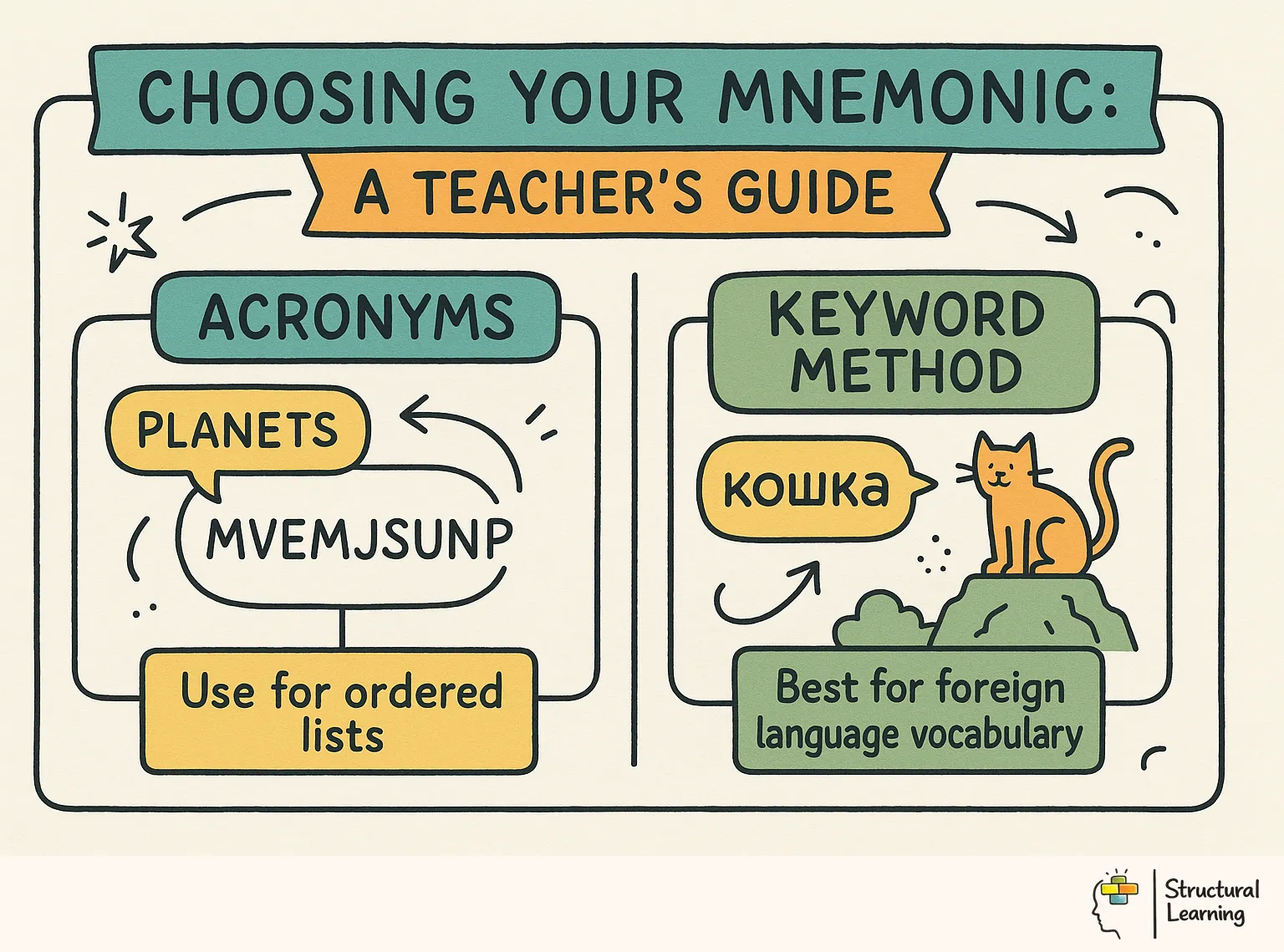

The effectiveness of a technique depends on the type of information being learned. For lists and sequences, acrostics and acronyms are usually best. For learning foreign vocabulary or abstract terms, the keyword method is the gold standard because it creates a strong visual and acoustic link.

No, mnemonics are a tool to facilitate the retrieval of facts so that deeper learning can occur. They provide the 'hooks' that allow students to hold information in their heads while they work on understanding the 'why' and 'how' behind the concepts. Without these basic facts, students often struggle to engage with higher-level analysis.

Yes, mnemonics are particularly beneficial for students with dyslexia and other language-based learning difficulties. Because these students often struggle with phonological processing and working memory, visual and spatial mnemonics provide an alternative route to the information. Techniques like the method of loci or the keyword method allow them to use their typically strong visual reasoning to bypass their linguistic weaknesses.

Start by modelling the process for them. Show them a list of information, think out loud as you look for patterns or rhymes, and then create a silly sentence or image together as a class. Once they understand the 'mechanics', give them a new list and ask them to work in pairs to create their own. The most effective mnemonics are often the ones that are personal, funny, or even a bit bizarre.

A mnemonic is a scaffold, and like all scaffolds, it should be removed once it is no longer needed. As students become experts in a topic, the information becomes 'automated' in their long-term memory. At this point, they will find that they can recall the facts directly without having to go through the mnemonic steps. If a student is still relying on the mnemonic after months of practise, they may need more intensive retrieval practise to build fluency.

Yes, there is a danger of 'mnemonic overload' where students have to remember so many acrostics and keywords that they become confused. Teachers should reserve mnemonics for the most critical, foundational information that is traditionally difficult to remember. It is also important to ensure that each mnemonic is distinct and clearly linked to its specific subject to avoid interference between different topics.

To help your students remember the steps for a new process tomorrow, ask them to create an acrostic using the names of their favourite food or sports teams.

Mnemonics for students are systematic procedures or mental strategies designed to improve memory by connecting new, unfamiliar information to existing knowledge. These techniques create artificial links between items that have no inherent relationship, making them easier to retrieve during exams or classroom activities. The term originates from Mnemosyne, the ancient Greek goddess of memory, reflecting a long history of human attempts to understand the cognitive system.

In a modern classroom, mnemonics serve as mental hooks that allow pupils to bypass the limitations of working memory. Most learners can only hold a small amount of information in their active focus at any one time (Miller, 1956). By using a mnemonic, a student can 'package' several pieces of data into a single, manageable unit. This reduces the mental effort required to recall basic facts, allowing the student to focus on higher-order thinking and problem-solving.

Teachers use these strategies to ensure that foundational knowledge is 'sticky' enough to persist over time. For example, when teaching the order of operations in mathematics, a teacher might introduce the acronym BIDMAS (Brackets, Indices, Division, Multiplication, Addition, Subtraction). The teacher explains that each letter stands for a mathematical operation, and the pupils recite the word 'BIDMAS' while pointing to the corresponding parts of an equation on the board. This simple vocal and physical routine helps the sequence move from short-term awareness into a more stable memory structure.

The effectiveness of mnemonics for students is well documented in cognitive psychology, particularly through the lens of Levels of Processing theory. Craik and Lockhart (1972) argued that the strength of a memory depends on the 'depth' of the encoding process. Mnemonics require students to think about the meaning, sound, or visual properties of a word, which creates a 'deep' memory trace. Instead of passive repetition, the student actively manipulates the information to fit the mnemonic structure.

Dual Coding Theory also provides a strong explanation for why certain mnemonics work so well. Paivio (1971) suggested that the human brain processes verbal and visual information through two separate but interconnected channels. When a student uses a mnemonic that involves both a word and a mental image, they are encoding the information twice. If they forget the word, the visual image may still be available to trigger the retrieval of the linguistic data. This 'double coding' makes the information much more resilient to forgetting.

Research specifically focused on students with learning difficulties has shown that mnemonics can significantly close the attainment gap. Scruggs and Mastropieri (1990) conducted a meta-analysis of mnemonic instruction and found that it consistently outperformed traditional teaching methods for pupils with SEND. Their findings suggest that mnemonics provide the external structure that these students often struggle to create for themselves. By providing a clear retrieval path, teachers can help students with dyslexia or working memory issues feel more successful in academic settings.

Another critical area of research is the 'Bizarreness Effect', which suggests that unusual or vivid images are easier to remember than mundane ones (Einstein and McDaniel, 1987). When teachers encourage students to create funny or strange acrostics, they are tapping into this cognitive bias. However, some researchers caution that if a mnemonic becomes too elaborate, it can interfere with the learning of the target concept (Sweller, 1988). The goal is to find a balance where the mnemonic is memorable enough to work without becoming a source of extraneous cognitive load.

Implementing mnemonics for students requires more than just sharing a clever phrase; teachers must model how to create, use, and eventually fade these scaffolds as knowledge becomes automated. Each of the following strategies serves a different cognitive purpose and should be selected based on the nature of the content.

The keyword method is a two-step process designed to help students learn new words, especially in foreign languages or technical science. First, the student identifies a 'keyword' that sounds like the new word but is already familiar. Second, the student creates a mental image that connects the meaning of the new word with the keyword. This creates an acoustic and visual bridge that facilitates rapid recall during lessons.

In a Spanish lesson, the teacher might introduce the word 'Pato', which means duck. The teacher asks the pupils to think of a word that sounds like 'Pato', and a student suggests 'Pot'. The teacher then tells the class to close their eyes and imagine a duck wearing a large, shiny cooking pot on its head like a hat. During the next retrieval quiz, the teacher says 'Pato', the students think of 'Pot', they see the image of the duck, and they correctly translate the word back to English.

Acrostics are sentences where the first letter of each word corresponds to the first letter of the items to be remembered. This technique is particularly useful for sequences that have a fixed order, such as the planets in the solar system or the strings of a guitar. Teachers should encourage students to create their own acrostics, as the personal effort involved in the creative process enhances the initial encoding.

In a Geography lesson, the teacher wants students to remember the order of the points on a compass. Instead of just repeating North, East, South, West, the teacher asks the class to come up with a funny sentence using those letters. A student suggests 'Never Eat Shredded Wheat'. The class laughs, and the teacher writes the sentence on the board, circling the first letter of each word. The pupils then draw a compass in their books and write the 'Never Eat Shredded Wheat' sentence around the outside to anchor the positions.

The pegword method uses rhyming words to create a set of mental 'pegs' on which students can hang new information. The student first learns a standard list of rhymes for the numbers one to ten, such as 'One is a Bun, Two is a Shoe, Three is a Tree'. Once these pegs are permanent, the student can link any new list of items to these images. This is an advanced strategy that works well for remembering the stages of a process or a specific set of rules.

In a Science lesson about the states of matter, the teacher uses pegwords to help students remember the properties of solids. The teacher says, 'Number one is a bun, and a solid has a fixed shape, so imagine a bun that is frozen hard like a rock'. For 'Two is a shoe', the teacher asks students to imagine a solid shoe that does not flow like water. The pupils sketch a frozen bun and a rigid shoe in their margins, labelling them with the properties of solids. This visual association helps them retrieve the characteristics of matter during a structured observation task.

The method of loci, often called a 'memory palace', involves placing items to be remembered along a familiar physical route. This strategy leverages the brain's powerful spatial memory systems. Students imagine walking through their house or school and 'dropping' information at specific locations. This is highly effective for long speeches, the plot of a novel, or the events leading up to a historical conflict.

In a History lesson about the causes of World War I, the teacher asks the students to imagine the school's entrance hall. The teacher says, 'At the front door, we see a giant pile of gunpowder representing the Balkan tensions'. As they move to the reception desk, the teacher tells them to imagine the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand happening right there. The pupils walk through the school building later that day, mentally revisiting each 'hotspot' to practise their recall. The physical movement through the space reinforces the chronological order of the historical events.

Teacher's Guide infographic for teachers" loading="lazy">

Teacher's Guide infographic for teachers" loading="lazy">

One frequent misconception is that mnemonics for students are just a form of 'rote learning' that lacks depth. Critics argue that memorising an acronym like 'Richard Of York Gave Battle In Vain' does not help a student understand the physics of light refraction. While a mnemonic is not a substitute for understanding, it is a tool for providing the 'labels' that allow for deeper discussion. A student cannot explain the formation of a rainbow if they cannot even remember the names of the colours. Research shows that once the basic facts are secure, students have more cognitive capacity to engage with complex concepts (Rosenshine, 2012).

Another myth is that mnemonics are a sign of 'lazy teaching' or that they should only be used as a last resort. Some educators believe that if a concept is taught well enough, students will remember it naturally without the need for 'tricks'. However, even the most profound understanding can be difficult to retrieve under the pressure of an exam. Mnemonics provide a safety net for the retrieval process, ensuring that students can access their knowledge even when they are stressed or tired. They are a legitimate pedagogical tool used by memory experts and high-performing students alike.

A third misconception is that mnemonics for students will work automatically for every learner in the room. In reality, the effectiveness of a mnemonic depends heavily on the student's prior knowledge and cultural background. An acrostic that uses references to a specific television show or hobby might be incredibly memorable for one group but completely meaningless to another. Teachers must ensure that the keywords and images used are accessible to all pupils. If a student has to work too hard to remember the mnemonic itself, the strategy will fail to support the learning of the primary content.

Finally, some teachers believe that mnemonics are only useful for younger primary pupils. While the 'fun' element of mnemonics is often associated with early years education, the cognitive benefits are just as relevant for A-Level and university students. Medical students, for example, famously use complex mnemonics to learn the names of cranial nerves and bones. The complexity of the content simply changes; the underlying need for a retrieval scaffold remains constant as the volume of information increases.

Mnemonics for students look different depending on the discipline. The following examples demonstrate how teachers can adapt these strategies to meet the specific demands of different subject areas.

In Mathematics, students often struggle with the abstract nature of formulas and the sequence of steps required to solve equations. A common mnemonic for trigonometry is SOH CAH TOA, which stands for Sine = Opposite/Hypotenuse, Cosine = Adjacent/Hypothenuse, and Tangent = Opposite/Adjacent.

The teacher introduces this by writing the three 'words' in large letters across the top of the whiteboard. The teacher tells a story about an ancient chief named 'Soh-Cah-Toa' who lived near a triangle-shaped mountain. The pupils then draw a right-angled triangle and label the sides, chanting the chief's name as they identify which ratio to use for a given problem. This verbal anchor prevents the common error of using the wrong trigonometric ratio during independent practise.

Science involves many complex cycles and hierarchies that can easily become confused in a student's mind. To remember the classification of living things (Kingdom, Phylum, Class, Order, Family, Genus, Species), teachers often use the acrostic 'Keep Ponds Clean Or Fish Get Sick'.

During a Biology lesson, the teacher shows a picture of a dirty pond and a sad fish. The teacher says, 'To keep our fish healthy, we must remember the order of classification'. The pupils write the sentence in their books, using a different colour for the first letter of each word. The teacher then gives them a list of specific animals and asks them to 'sort them through the pond', checking each level of the hierarchy against the mnemonic. This provides a clear, step-by-step check that ensures accuracy in their classification work.

In English, mnemonics are useful for mastering 'tricky' spellings and remembering the various components of a persuasive argument. For the word 'Beautiful', many teachers use the phrase 'Big Elephants Are Under Trees In Useless Lakes'.

The teacher writes the word 'BEAUTIFUL' on the board and asks the pupils why it is a difficult word to spell. The students point out the 'eau' vowel string. The teacher then shares the 'Big Elephants' phrase and asks the pupils to draw a picture of a giant elephant sitting under a tree by a lake. Every time the students write the word in their creative writing, they whisper the phrase to themselves. This visual and rhythmic support helps the correct spelling become a permanent part of their writing repertoire.

History students must grapple with long timelines and multiple factors leading to single events. To remember the six wives of Henry VIII in order (Aragon, Boleyn, Seymour, Cleves, Howard, Parr), teachers often use the rhyme 'Divorced, Beheaded, Died, Divorced, Beheaded, Survived'.

The teacher presents a series of portraits of the six wives and asks the students to guess their fates. After the initial discussion, the teacher introduces the rhythmic rhyme, clapping on each word. The pupils then create a 'fate timeline' in their books, matching the rhyme to the names and dates. This auditory pattern acts as a retrieval cue that helps students organise their knowledge of the Tudor period during essay writing.

| Subject | Mnemonic Type | Example | Purpose |

| :--- | :--- | :--- | :--- |

| Maths | Acronym | BIDMAS | Order of Operations |

| Science | Acrostic | MRS GREN | Seven Life Processes (Movement, Respiration, etc.) |

| History | Rhyme | Divorced, Beheaded... | Wives of Henry VIII |

| Geography | Acrostic | Never Eat Shredded Wheat | Compass Points |

| English | Acrostic | AFOREST | Persuasive Devices (Alliteration, Facts, etc.) |

Mnemonics for students do not exist in a vacuum; they are part of a wider ecosystem of cognitive science strategies. Understanding these connections helps teachers use mnemonics more strategically within their lesson planning.

One of the most important links is to Dual Coding. As previously mentioned, mnemonics that combine a verbal cue with a visual image use two different cognitive pathways. When a teacher uses the keyword method, they are essentially creating a dual-coded memory. This increases the number of retrieval paths available to the student, making the information much more accessible during a test. By explicitly linking mnemonics to visual imagery, teachers can make their memory strategies significantly more powerful.

Mnemonics also relate closely to Cognitive Load Theory, developed by John Sweller. This theory suggests that our working memory has a limited capacity, and if we overload it, learning stops. Mnemonics reduce the 'intrinsic' load of a task by 'chunking' information. If a student knows the mnemonic AFOREST (Alliteration, Facts, Opinions, Rhetorical questions, Emotive language, Statistics, Triplets), they do not have to work hard to remember what to include in a persuasive letter. This frees up their 'germane' cognitive load for the much harder task of actually writing the persuasive content.

The use of mnemonics is also a form of Retrieval Practise. Every time a student uses a mnemonic to recall a fact, they are strengthening the neural pathway to that information. However, mnemonics are most effective when they are paired with Spaced Practise. A teacher might introduce a mnemonic in week one, then ask the students to retrieve the information using that mnemonic in week three, week six, and week ten. This 'distributed' retrieval helps move the information from short-term 'scaffolded' memory into permanent long-term storage.

Finally, mnemonics support the development of Metacognition. When students learn how to create their own mnemonics, they are becoming more aware of how their own memory works. They are learning to identify which information is likely to be forgotten and taking proactive steps to prevent that from happening. This 'learning how to learn' is a skill that students can take with them beyond the classroom, applying it to their revision for GCSEs, A-Levels, and future careers.

The effectiveness of a technique depends on the type of information being learned. For lists and sequences, acrostics and acronyms are usually best. For learning foreign vocabulary or abstract terms, the keyword method is the gold standard because it creates a strong visual and acoustic link.

No, mnemonics are a tool to facilitate the retrieval of facts so that deeper learning can occur. They provide the 'hooks' that allow students to hold information in their heads while they work on understanding the 'why' and 'how' behind the concepts. Without these basic facts, students often struggle to engage with higher-level analysis.

Yes, mnemonics are particularly beneficial for students with dyslexia and other language-based learning difficulties. Because these students often struggle with phonological processing and working memory, visual and spatial mnemonics provide an alternative route to the information. Techniques like the method of loci or the keyword method allow them to use their typically strong visual reasoning to bypass their linguistic weaknesses.

Start by modelling the process for them. Show them a list of information, think out loud as you look for patterns or rhymes, and then create a silly sentence or image together as a class. Once they understand the 'mechanics', give them a new list and ask them to work in pairs to create their own. The most effective mnemonics are often the ones that are personal, funny, or even a bit bizarre.

A mnemonic is a scaffold, and like all scaffolds, it should be removed once it is no longer needed. As students become experts in a topic, the information becomes 'automated' in their long-term memory. At this point, they will find that they can recall the facts directly without having to go through the mnemonic steps. If a student is still relying on the mnemonic after months of practise, they may need more intensive retrieval practise to build fluency.

Yes, there is a danger of 'mnemonic overload' where students have to remember so many acrostics and keywords that they become confused. Teachers should reserve mnemonics for the most critical, foundational information that is traditionally difficult to remember. It is also important to ensure that each mnemonic is distinct and clearly linked to its specific subject to avoid interference between different topics.

To help your students remember the steps for a new process tomorrow, ask them to create an acrostic using the names of their favourite food or sports teams.

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/mnemonics-students-teachers-toolkit-memory#article","headline":"Mnemonics for Students: A Teacher's Toolkit for Memory Strategies","description":"Mnemonics for students help learners retain complex information through mental shortcuts. Use these evidence-based memory strategies to support long-term ret...","datePublished":"2026-02-15T19:53:01.975Z","dateModified":"2026-02-15T20:16:36.318Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/mnemonics-students-teachers-toolkit-memory"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/6992241da5d8f590f65ea377_699223ac2d6b3650c7cba0d6_mnemonics-for-students-a-teach-definition-1771185067674.webp","wordCount":3315},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/mnemonics-students-teachers-toolkit-memory#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"Mnemonics for Students: A Teacher's Toolkit for Memory Strategies","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/mnemonics-students-teachers-toolkit-memory"}]}]}