Concept-Based Learning

Discover concept-based learning strategies that help pupils connect ideas across subjects, develop critical thinking skills, and achieve deeper understanding.

Discover concept-based learning strategies that help pupils connect ideas across subjects, develop critical thinking skills, and achieve deeper understanding.

Concept-based learning is structured through inquiry and looks through a conceptual lens that is connected to content and skills. It encourages learning within, between and across subjects and disciplines.

In doing so, it encourages learners to see and make connections across subjects and to also create new understandings from the learning they have gained in those subjects in ways that are transdisciplinary and interdisciplinary. It embraces and utilises transferable skills. In doing so the learner can transfer ideas and skills learnt to a new context and apply them to problems in creative, flexible and adaptable ways.

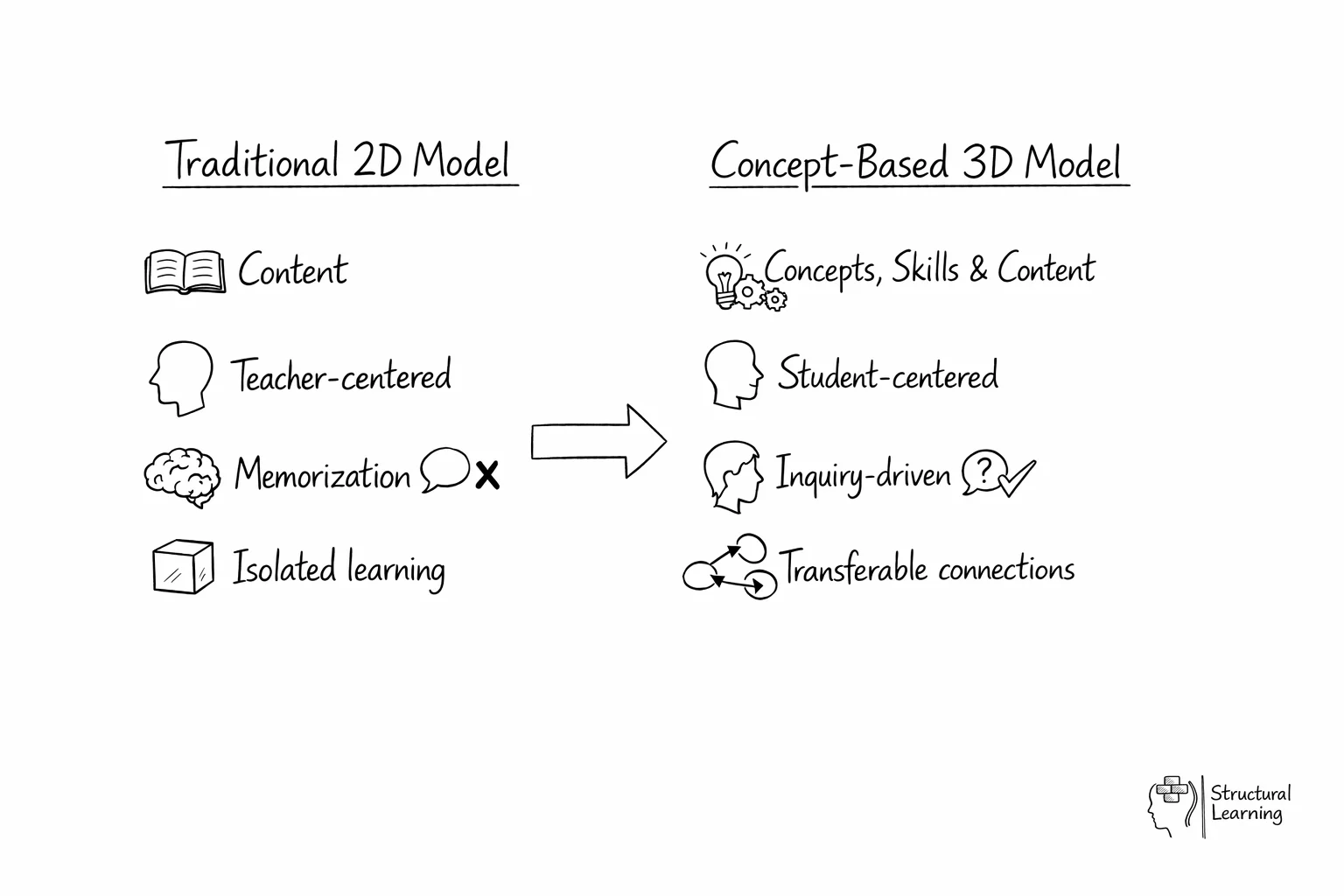

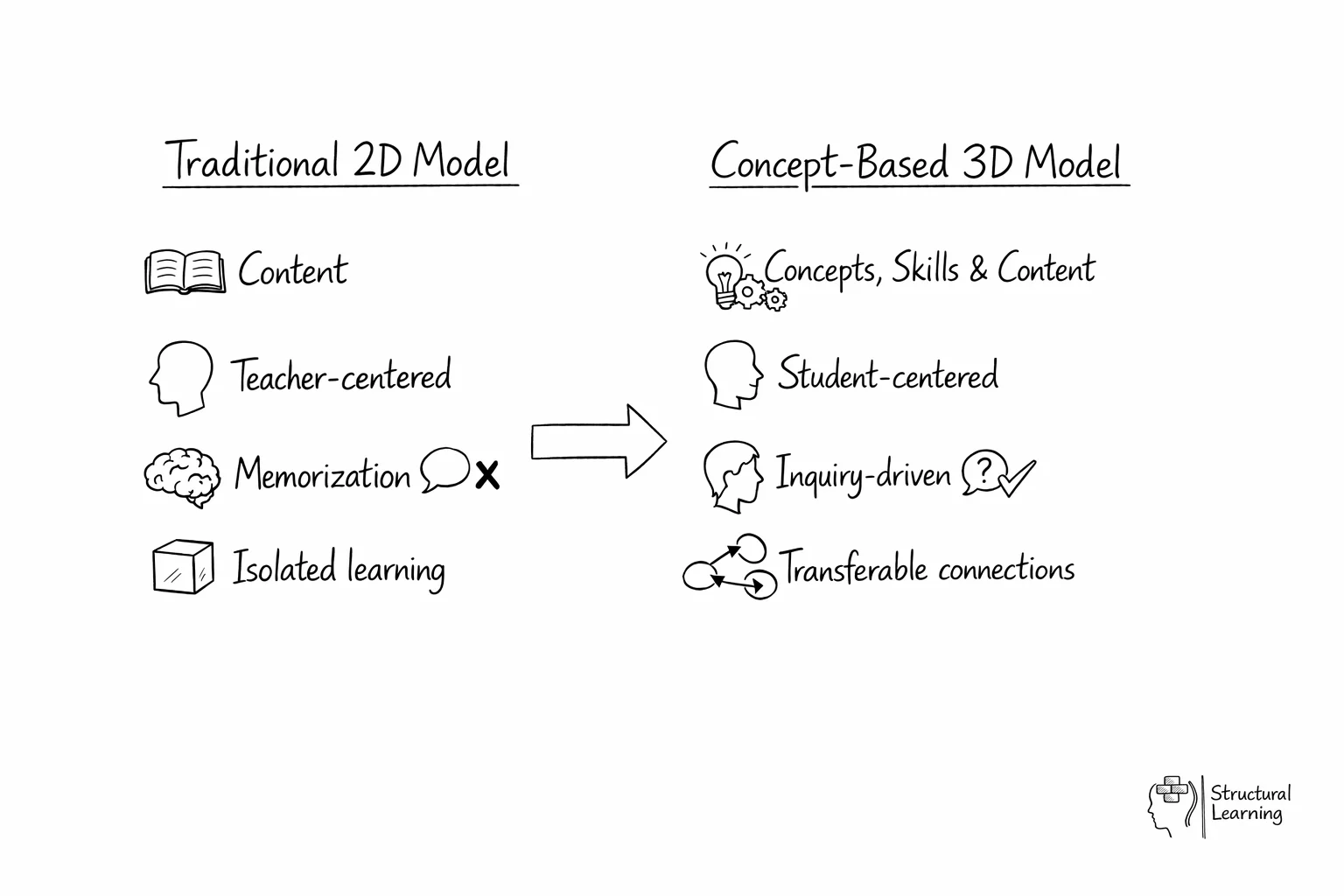

It strongly puts concepts in the driving seat of learning but it also must be noted that it requires content and skills. Therefore, it can be applied to a three-dimensional curriculum that includes concepts, content and skills that are channelled through inquiry and questioning. It takes content and skills and drives them using concepts that are broad enough to create interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary connections within and between subjects.

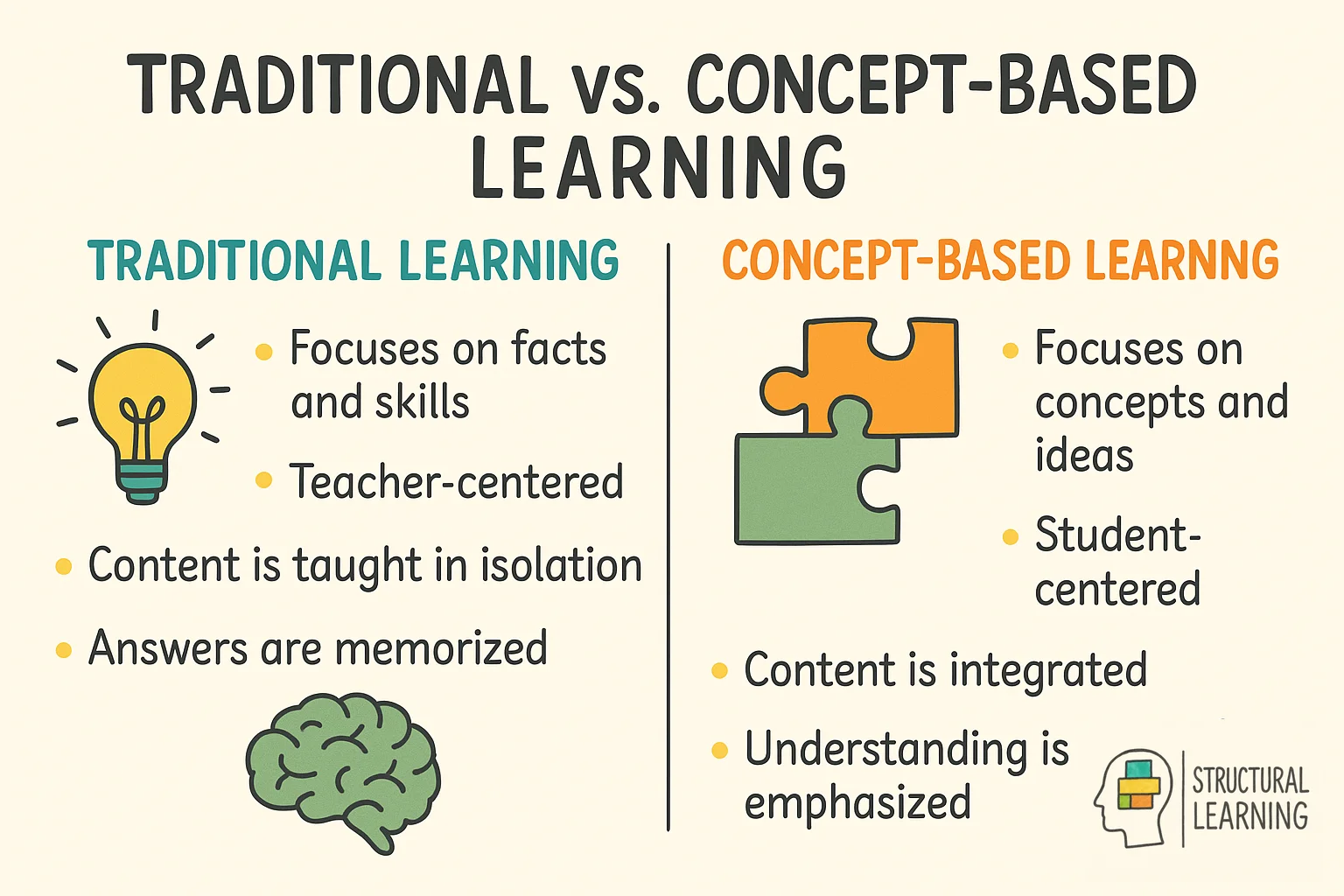

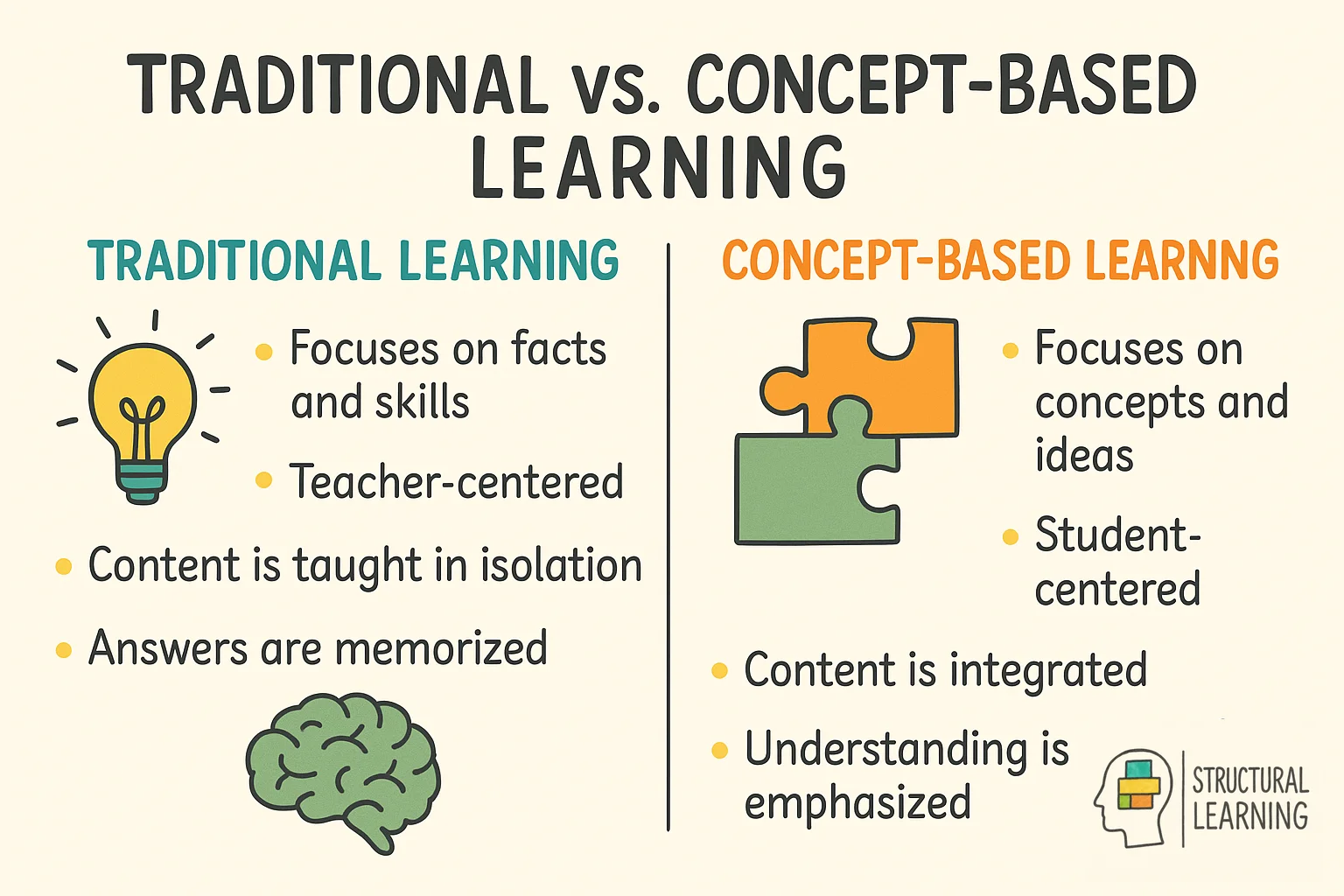

In contrast, traditional models are considered two-dimensional as they focus on content and skills. These traditional models place an emphasis and focus on content knowledge and skills.

Concept-based learning builds on constructivist theory, emphasising that students construct understanding by connecting big ideas acr oss disciplines. The framework uses a three-dimensional model combining concepts, content, and skills, moving beyond traditional two-dimensional approaches that focus only on content and skills. This structure enables students to transfer knowledge between subjects and apply learning to new contexts.

A theoretical framework is developed from an existing theory and is an expression of work based on other research. A conceptual framework is developed from concepts and is driven by exploration and inquiry. It is the result of a research question or questions to be investigated. A conceptual framework can also include a theoretical framework.

Concept-based approaches embrace concepts and allow them to drive the content and process skills through inquiry. This learning is blended and connected to real life and the world, in authentic ways and enables the development of deeper thinking.

By utilising constructivist approaches, meaning and knowledge is built through experiences and active, authentic learning opportunities. This coupled with concepts creates deeper understanding and deeper thinking that is uniquely concept-based. Young people through an inquiry approach are encouraged to be creative, think critically and reflect on their learning.

Concepts are broad and as a result create connections within, between and across subjects and this allows for transferable skill development.

The more traditional educational paradigms are content and skills-based compared to modern educational models that are concept-based. It is these that recognise the value of concepts driving the content and skills and are related to themes, big ideas and inquiry approaches to learning.

The learner is therefore exposed to deeper thinking through higher-order thinking skills that transfer. This is unique to a three-dimensional curriculum that embraces concepts as a key component in learning with content and skills.

This approach as such, allows for the focus to be more student-centred and inquiry-driven through ideas, unlike traditional teaching which is more heavily focused on memorisation and rote learning and can lend itself more towards a teacher-centred approach.

Conceptual learning is the interplay between levels of thinking that start at the lower end of knowledge skills that need to be connected to higher, conceptual levels of thinking. Note that having a knowledge base is both necessary and important, but is regarded as a lower cognitive ability. The ability to remember can be gained via memorisation and rote.

This is both useful and needed, but to be more highly effective, we need connections that are made through ideas and concepts. It is this that allows for more complex thinkingthat leads to deeper understanding. It is connections, analysis, creation and evalua tion that are high-level skills that should be embraced. These are also the skills that are needed in today’s modern world for adaptation and creative application.

Concept-based learning offers numerous benefits for students, educators, and the wider learning community. It cultivates deeper understanding and promotes transferrable skills, equipping students with the tools to tackle complex problems and thrive in a rapidly changing world. Here are some key benefits:

Implementing concept-based learning requires careful planning and a shift in pedagogical approach. Here are some practical strategies to help you integrate concept-based learning into your classroom:

Concept-based learning provides pupils with opportunities to broaden their skill set in creative and unique ways. It encourages learners to think outside the box and use a variety of skill sets when problem-solving. It’s a great way to encourage your pupils to learn from each other, and transfer understanding and skills across various learning areas.

Concept-based learning represents a significant shift from traditional, content-driven education. By prioritising conceptual understanding, transferable skills, and inquiry-based learning, it helps students to become critical thinkers, problem-solvers, and lifelong learners. It moves away from surface-level memorisation and encourages students to engage more meaningfully with subject content.

As educators, embracing concept-based learning can transform our classrooms into vibrant hubs of inquiry and discovery. By guiding our students to explore big ideas, make connections, and apply their knowledge in creative ways, we equip them with the tools they need to thrive in an ever-changing world. The future of education lies in developing deep understanding and helping students to become active participants in their own learning process.

Assessment in concept-based learning requires a fundamental shift from traditional testing methods that focus on content recall. Effective assessment strategies must evaluate pupils' ability to transfer conceptual understanding across contexts, not simply memorise isolated facts.

Performance-based assessment becomes crucial in this approach. Rather than asking pupils to define photosynthesis, for example, teachers might present a scenario where plants in different environments show varying growth rates and ask pupils to apply their understanding of systems and energy transfer to explain the phenomena. This method reveals whether pupils truly grasp the underlying concepts.

Conceptual rubrics prove particularly valuable for UK teachers implementing this approach. These rubrics assess understanding at different levels: factual knowledge, conceptual understanding, and transfer capability. For instance, when teaching about conflict in history, pupils might demonstrate factual knowledge by recalling dates and events, show conceptual understanding by explaining how economic factors contribute to social tension, and display transfer by applying these concepts to analyse contemporary global issues.

Portfolio assessments work exceptionally well in concept-based learning environments. Pupils can document their evolving understanding of key concepts throughout a term or academic year. A Year 8 geography portfolio might trace how pupils' understanding of "interdependence" develops from local ecosystems to global economic systems, demonstrating conceptual growth across multiple contexts.

Peer assessment and self-reflection activities help pupils articulate their conceptual understanding. When pupils explain how the concept of "balance" applies to both mathematical equations and chemical reactions, they reinforce their own learning while revealing gaps in understanding that teachers can address.

Digital tools such as concept mapping software allow teachers to visualise pupil thinking and track conceptual development over time. These visual representations help identify misconceptions and provide clear evidence of learning progression for both teachers and pupils.

Designing effective conceptual units requires careful planning that balances conceptual depth with curriculum coverage. Successful UK schools typically begin by identifying 6-8 key concepts that will thread through their entire curriculum, ensuring coherence and transfer opportunities.

The backwards design process proves essential when creating conceptual units. Teachers start with enduring understandings, such as "Systems are interconnected and changes in one part affect the whole," then identify the content and skills that will help pupils develop this understanding. A Year 5 unit on "Change" might weave together science content about states of matter, historical content about the Industrial Revolution, and mathematical content about data analysis and graphs.

Cross-curricular collaboration becomes vital for effective implementation. In many successful UK primary schools, year group teams meet weekly to align their conceptual focus. When the science teacher explores adaptation in living things, the English teacher might examine how characters adapt to challenges in literature, whilst the maths teacher investigates how data collection methods must adapt to different contexts.

Essential questions drive conceptual units and maintain focus on big ideas rather than discrete topics. Instead of asking "What is the water cycle?", teachers pose questions like "How do systems maintain balance?" or "What happens when systems are disrupted?" These questions encourage pupils to see connections between water cycles, economic systems, and even playground ecosystems.

Concept-based units typically follow a three-part structure: hook activities that engage pupils with the conceptual lens, exploration phases where pupils encounter the concept across multiple contexts, and synthesis activities where pupils demonstrate transfer. A secondary unit on "Power" might begin with pupils analysing different forms of power in their daily lives, progress through scientific, political, and literary explorations of power, and culminate in pupils designing solutions to power imbalances in their school community.

Resource selection becomes more strategic in conceptual units. Rather than using textbooks sequentially, teachers curate materials that illuminate concepts from multiple angles. Primary sources, current events, scientific phenomena, and mathematical patterns all serve as vehicles for conceptual exploration.

UK teachers frequently encounter specific obstacles when transitioning to concept-based learning, but practical strategies can address these challenges effectively. Understanding common pitfalls helps schools implement this approach more successfully.

Curriculum coverage concerns represent the most frequent worry among teachers. Many fear that focusing on concepts will leave insufficient time for required content. However, experienced practitioners find that concept-based learning actually accelerates content coverage by helping pupils see patterns and connections. When Year 7 pupils understand "cause and consequence" as a historical concept, they grasp new historical events more quickly because they can apply this conceptual framework.

Parental resistance sometimes emerges, particularly from families accustomed to traditional subject-focused approaches. Successful schools address this through clear communication about learning outcomes and regular showcases where pupils demonstrate their conceptual understanding. Parent workshops that illustrate how concepts enhance rather than replace content knowledge help build community support.

Teacher confidence often wavers during initial implementation. Many teachers feel uncertain about facilitating inquiry-based learning or worry about maintaining classroom control during more open-ended activities. Professional learning communities within schools provide essential support, allowing teachers to share successes and troubleshoot challenges together. Mentoring partnerships between experienced concept-based practitioners and newcomers prove particularly valuable.

Time constraints present ongoing challenges, especially given the packed UK curriculum requirements. Successful schools address this by starting small, perhaps implementing concept-based approaches in one subject area or year group before expanding. Some schools designate specific afternoon sessions for conceptual inquiry projects, maintaining traditional morning lessons while teachers build confidence.

Assessment pressures, particularly SATs and GCSE preparation, can undermine conceptual approaches. However, schools discover that pupils who develop strong conceptual understanding often perform better on standardised tests because they can apply their knowledge flexibly rather than simply recalling memorised information. Strategic test preparation that reinforces conceptual understanding proves more effective than drill-and-practise methods.

Resource limitations need not prevent implementation. Many concept-based activities require minimal materials but significant planning time. Schools can support teachers by providing protected planning time and gradually building resource collections that support conceptual inquiry across multiple subjects.

Concept-based learning is an educational approach that focuses on broad concepts and big ideas, encouraging students to make connections across subjects and develop deeper understanding through inquiry. It moves beyond traditional content-and-skills teaching by incorporating a three-dimensional curriculum that includes concepts, content, and skills.

To implement concept-based learning, start by identifying key concepts and big ideas that are relevant to your curriculum. Design lessons that encourage inquiry and exploration around these concepts, allowing students to make connections and apply their understanding in real-world contexts. Use questions to guide students' thinking and facilitate discussions.

Concept-based learning promotes deeper understanding, critical thinking, and transferable skills. It helps students see connections across subjects and disciplines, making learning more meaningful and engaging. Additionally, it prepares students to apply their knowledge in new contexts and fosters creativity and problem-solving abilities.

Common mistakes include focusing too heavily on content or skills at the expense of concepts, failing to design meaningful inquiry-based lessons, and not adequately scaffolding students' learning. It's important to balance the three dimensions of concepts, content, and skills while ensuring that lessons are engaging and relevant.

To determine if concept-based learning is effective, look for evidence of deeper understanding, critical thinking, and the ability to transfer knowledge across subjects. Assess students' ability to make connections, solve problems creatively, and apply their learning in new contexts. Regularly gather feedback from students and observe changes in their engagement and academic performance.

For further academic research on this topic:

To examine deeper into the principles and practices of concept-based learning, consider exploring these resources:

These studies examine concept-based curriculum and instruction, transfer of learning, and the evidence for teaching through big ideas rather than isolated facts. Each paper provides practical guidance for teachers designing lessons around conceptual understanding.

Concept-Based Curriculum and Instruction for the Thinking Classroom View study ↗

131 citations

Erickson, H. L. (2017)

Erickson's foundational work sets out the architecture of concept-based curriculum design, distinguishing between factual knowledge, conceptual understanding, and transferable generalisations. She argues that traditional topic-based curricula leave pupils with disconnected facts, while concept-based approaches help them build mental schemas they can apply in new situations. For teachers, the practical framework of "facts + concepts = generalisations" provides a clear method for planning units that develop deeper understanding.

Transfer of Life Skills in Sport-Based Youth Development Programs: A Conceptual Framework View study ↗

132 citations

Jacobs, J. M. and Wright, P. M. (2018)

Jacobs and Wright develop a framework for understanding how conceptual learning transfers to new contexts. Their research identifies three conditions for successful transfer: explicit discussion of underlying concepts, practice applying concepts in varied situations, and reflection on how concepts connect across domains. For classroom teachers, this confirms that transfer does not happen automatically; pupils need structured opportunities to identify and apply concepts across different subjects and contexts.

A Conceptual Framework for Educational Design at Modular Level to Promote Transfer of Learning View study ↗

58 citations

Botma, Y. and Van Rensburg, G. H. (2015)

Botma and Van Rensburg create a practical design framework that helps educators structure learning for maximum transfer. Their model identifies specific design principles including authentic contexts, spaced practice, and progressive complexity. For teachers, the framework offers a step-by-step approach to unit planning: start with a concept, introduce it through a concrete example, practice with varied contexts, and culminate with pupils applying the concept to an unfamiliar situation.

Stirring the Head, Heart, and Soul: Redefining Curriculum, Instruction, and Concept-Based Learning View study ↗

70 citations

Erickson, H. L. (2007)

In this earlier work, Erickson establishes the theoretical rationale for concept-based learning, drawing on cognitive science research about how the brain organises and retrieves information. She demonstrates that when pupils learn facts in connection with overarching concepts, they build more robust mental models and retain information longer. The book includes practical planning templates that teachers can use to restructure existing units around conceptual themes without starting from scratch.

Is Formal Language Proficiency Required to Profit from a Bilingual Teaching Intervention in Mathematics? View study ↗

57 citations

Schuler-Meyer, A. and Prediger, S. (2019)

Schuler-Meyer and Prediger examine how conceptual understanding develops when pupils learn mathematics through multiple languages, finding that conceptual thinking transcends language barriers. Their study demonstrates that focusing on conceptual understanding rather than procedural fluency benefits multilingual pupils in particular. For teachers in diverse UK classrooms, this research supports using concept-based approaches with EAL pupils, encouraging them to explain mathematical ideas in their strongest language before translating to English.

Concept-based learning is structured through inquiry and looks through a conceptual lens that is connected to content and skills. It encourages learning within, between and across subjects and disciplines.

In doing so, it encourages learners to see and make connections across subjects and to also create new understandings from the learning they have gained in those subjects in ways that are transdisciplinary and interdisciplinary. It embraces and utilises transferable skills. In doing so the learner can transfer ideas and skills learnt to a new context and apply them to problems in creative, flexible and adaptable ways.

It strongly puts concepts in the driving seat of learning but it also must be noted that it requires content and skills. Therefore, it can be applied to a three-dimensional curriculum that includes concepts, content and skills that are channelled through inquiry and questioning. It takes content and skills and drives them using concepts that are broad enough to create interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary connections within and between subjects.

In contrast, traditional models are considered two-dimensional as they focus on content and skills. These traditional models place an emphasis and focus on content knowledge and skills.

Concept-based learning builds on constructivist theory, emphasising that students construct understanding by connecting big ideas acr oss disciplines. The framework uses a three-dimensional model combining concepts, content, and skills, moving beyond traditional two-dimensional approaches that focus only on content and skills. This structure enables students to transfer knowledge between subjects and apply learning to new contexts.

A theoretical framework is developed from an existing theory and is an expression of work based on other research. A conceptual framework is developed from concepts and is driven by exploration and inquiry. It is the result of a research question or questions to be investigated. A conceptual framework can also include a theoretical framework.

Concept-based approaches embrace concepts and allow them to drive the content and process skills through inquiry. This learning is blended and connected to real life and the world, in authentic ways and enables the development of deeper thinking.

By utilising constructivist approaches, meaning and knowledge is built through experiences and active, authentic learning opportunities. This coupled with concepts creates deeper understanding and deeper thinking that is uniquely concept-based. Young people through an inquiry approach are encouraged to be creative, think critically and reflect on their learning.

Concepts are broad and as a result create connections within, between and across subjects and this allows for transferable skill development.

The more traditional educational paradigms are content and skills-based compared to modern educational models that are concept-based. It is these that recognise the value of concepts driving the content and skills and are related to themes, big ideas and inquiry approaches to learning.

The learner is therefore exposed to deeper thinking through higher-order thinking skills that transfer. This is unique to a three-dimensional curriculum that embraces concepts as a key component in learning with content and skills.

This approach as such, allows for the focus to be more student-centred and inquiry-driven through ideas, unlike traditional teaching which is more heavily focused on memorisation and rote learning and can lend itself more towards a teacher-centred approach.

Conceptual learning is the interplay between levels of thinking that start at the lower end of knowledge skills that need to be connected to higher, conceptual levels of thinking. Note that having a knowledge base is both necessary and important, but is regarded as a lower cognitive ability. The ability to remember can be gained via memorisation and rote.

This is both useful and needed, but to be more highly effective, we need connections that are made through ideas and concepts. It is this that allows for more complex thinkingthat leads to deeper understanding. It is connections, analysis, creation and evalua tion that are high-level skills that should be embraced. These are also the skills that are needed in today’s modern world for adaptation and creative application.

Concept-based learning offers numerous benefits for students, educators, and the wider learning community. It cultivates deeper understanding and promotes transferrable skills, equipping students with the tools to tackle complex problems and thrive in a rapidly changing world. Here are some key benefits:

Implementing concept-based learning requires careful planning and a shift in pedagogical approach. Here are some practical strategies to help you integrate concept-based learning into your classroom:

Concept-based learning provides pupils with opportunities to broaden their skill set in creative and unique ways. It encourages learners to think outside the box and use a variety of skill sets when problem-solving. It’s a great way to encourage your pupils to learn from each other, and transfer understanding and skills across various learning areas.

Concept-based learning represents a significant shift from traditional, content-driven education. By prioritising conceptual understanding, transferable skills, and inquiry-based learning, it helps students to become critical thinkers, problem-solvers, and lifelong learners. It moves away from surface-level memorisation and encourages students to engage more meaningfully with subject content.

As educators, embracing concept-based learning can transform our classrooms into vibrant hubs of inquiry and discovery. By guiding our students to explore big ideas, make connections, and apply their knowledge in creative ways, we equip them with the tools they need to thrive in an ever-changing world. The future of education lies in developing deep understanding and helping students to become active participants in their own learning process.

Assessment in concept-based learning requires a fundamental shift from traditional testing methods that focus on content recall. Effective assessment strategies must evaluate pupils' ability to transfer conceptual understanding across contexts, not simply memorise isolated facts.

Performance-based assessment becomes crucial in this approach. Rather than asking pupils to define photosynthesis, for example, teachers might present a scenario where plants in different environments show varying growth rates and ask pupils to apply their understanding of systems and energy transfer to explain the phenomena. This method reveals whether pupils truly grasp the underlying concepts.

Conceptual rubrics prove particularly valuable for UK teachers implementing this approach. These rubrics assess understanding at different levels: factual knowledge, conceptual understanding, and transfer capability. For instance, when teaching about conflict in history, pupils might demonstrate factual knowledge by recalling dates and events, show conceptual understanding by explaining how economic factors contribute to social tension, and display transfer by applying these concepts to analyse contemporary global issues.

Portfolio assessments work exceptionally well in concept-based learning environments. Pupils can document their evolving understanding of key concepts throughout a term or academic year. A Year 8 geography portfolio might trace how pupils' understanding of "interdependence" develops from local ecosystems to global economic systems, demonstrating conceptual growth across multiple contexts.

Peer assessment and self-reflection activities help pupils articulate their conceptual understanding. When pupils explain how the concept of "balance" applies to both mathematical equations and chemical reactions, they reinforce their own learning while revealing gaps in understanding that teachers can address.

Digital tools such as concept mapping software allow teachers to visualise pupil thinking and track conceptual development over time. These visual representations help identify misconceptions and provide clear evidence of learning progression for both teachers and pupils.

Designing effective conceptual units requires careful planning that balances conceptual depth with curriculum coverage. Successful UK schools typically begin by identifying 6-8 key concepts that will thread through their entire curriculum, ensuring coherence and transfer opportunities.

The backwards design process proves essential when creating conceptual units. Teachers start with enduring understandings, such as "Systems are interconnected and changes in one part affect the whole," then identify the content and skills that will help pupils develop this understanding. A Year 5 unit on "Change" might weave together science content about states of matter, historical content about the Industrial Revolution, and mathematical content about data analysis and graphs.

Cross-curricular collaboration becomes vital for effective implementation. In many successful UK primary schools, year group teams meet weekly to align their conceptual focus. When the science teacher explores adaptation in living things, the English teacher might examine how characters adapt to challenges in literature, whilst the maths teacher investigates how data collection methods must adapt to different contexts.

Essential questions drive conceptual units and maintain focus on big ideas rather than discrete topics. Instead of asking "What is the water cycle?", teachers pose questions like "How do systems maintain balance?" or "What happens when systems are disrupted?" These questions encourage pupils to see connections between water cycles, economic systems, and even playground ecosystems.

Concept-based units typically follow a three-part structure: hook activities that engage pupils with the conceptual lens, exploration phases where pupils encounter the concept across multiple contexts, and synthesis activities where pupils demonstrate transfer. A secondary unit on "Power" might begin with pupils analysing different forms of power in their daily lives, progress through scientific, political, and literary explorations of power, and culminate in pupils designing solutions to power imbalances in their school community.

Resource selection becomes more strategic in conceptual units. Rather than using textbooks sequentially, teachers curate materials that illuminate concepts from multiple angles. Primary sources, current events, scientific phenomena, and mathematical patterns all serve as vehicles for conceptual exploration.

UK teachers frequently encounter specific obstacles when transitioning to concept-based learning, but practical strategies can address these challenges effectively. Understanding common pitfalls helps schools implement this approach more successfully.

Curriculum coverage concerns represent the most frequent worry among teachers. Many fear that focusing on concepts will leave insufficient time for required content. However, experienced practitioners find that concept-based learning actually accelerates content coverage by helping pupils see patterns and connections. When Year 7 pupils understand "cause and consequence" as a historical concept, they grasp new historical events more quickly because they can apply this conceptual framework.

Parental resistance sometimes emerges, particularly from families accustomed to traditional subject-focused approaches. Successful schools address this through clear communication about learning outcomes and regular showcases where pupils demonstrate their conceptual understanding. Parent workshops that illustrate how concepts enhance rather than replace content knowledge help build community support.

Teacher confidence often wavers during initial implementation. Many teachers feel uncertain about facilitating inquiry-based learning or worry about maintaining classroom control during more open-ended activities. Professional learning communities within schools provide essential support, allowing teachers to share successes and troubleshoot challenges together. Mentoring partnerships between experienced concept-based practitioners and newcomers prove particularly valuable.

Time constraints present ongoing challenges, especially given the packed UK curriculum requirements. Successful schools address this by starting small, perhaps implementing concept-based approaches in one subject area or year group before expanding. Some schools designate specific afternoon sessions for conceptual inquiry projects, maintaining traditional morning lessons while teachers build confidence.

Assessment pressures, particularly SATs and GCSE preparation, can undermine conceptual approaches. However, schools discover that pupils who develop strong conceptual understanding often perform better on standardised tests because they can apply their knowledge flexibly rather than simply recalling memorised information. Strategic test preparation that reinforces conceptual understanding proves more effective than drill-and-practise methods.

Resource limitations need not prevent implementation. Many concept-based activities require minimal materials but significant planning time. Schools can support teachers by providing protected planning time and gradually building resource collections that support conceptual inquiry across multiple subjects.

Concept-based learning is an educational approach that focuses on broad concepts and big ideas, encouraging students to make connections across subjects and develop deeper understanding through inquiry. It moves beyond traditional content-and-skills teaching by incorporating a three-dimensional curriculum that includes concepts, content, and skills.

To implement concept-based learning, start by identifying key concepts and big ideas that are relevant to your curriculum. Design lessons that encourage inquiry and exploration around these concepts, allowing students to make connections and apply their understanding in real-world contexts. Use questions to guide students' thinking and facilitate discussions.

Concept-based learning promotes deeper understanding, critical thinking, and transferable skills. It helps students see connections across subjects and disciplines, making learning more meaningful and engaging. Additionally, it prepares students to apply their knowledge in new contexts and fosters creativity and problem-solving abilities.

Common mistakes include focusing too heavily on content or skills at the expense of concepts, failing to design meaningful inquiry-based lessons, and not adequately scaffolding students' learning. It's important to balance the three dimensions of concepts, content, and skills while ensuring that lessons are engaging and relevant.

To determine if concept-based learning is effective, look for evidence of deeper understanding, critical thinking, and the ability to transfer knowledge across subjects. Assess students' ability to make connections, solve problems creatively, and apply their learning in new contexts. Regularly gather feedback from students and observe changes in their engagement and academic performance.

For further academic research on this topic:

To examine deeper into the principles and practices of concept-based learning, consider exploring these resources:

These studies examine concept-based curriculum and instruction, transfer of learning, and the evidence for teaching through big ideas rather than isolated facts. Each paper provides practical guidance for teachers designing lessons around conceptual understanding.

Concept-Based Curriculum and Instruction for the Thinking Classroom View study ↗

131 citations

Erickson, H. L. (2017)

Erickson's foundational work sets out the architecture of concept-based curriculum design, distinguishing between factual knowledge, conceptual understanding, and transferable generalisations. She argues that traditional topic-based curricula leave pupils with disconnected facts, while concept-based approaches help them build mental schemas they can apply in new situations. For teachers, the practical framework of "facts + concepts = generalisations" provides a clear method for planning units that develop deeper understanding.

Transfer of Life Skills in Sport-Based Youth Development Programs: A Conceptual Framework View study ↗

132 citations

Jacobs, J. M. and Wright, P. M. (2018)

Jacobs and Wright develop a framework for understanding how conceptual learning transfers to new contexts. Their research identifies three conditions for successful transfer: explicit discussion of underlying concepts, practice applying concepts in varied situations, and reflection on how concepts connect across domains. For classroom teachers, this confirms that transfer does not happen automatically; pupils need structured opportunities to identify and apply concepts across different subjects and contexts.

A Conceptual Framework for Educational Design at Modular Level to Promote Transfer of Learning View study ↗

58 citations

Botma, Y. and Van Rensburg, G. H. (2015)

Botma and Van Rensburg create a practical design framework that helps educators structure learning for maximum transfer. Their model identifies specific design principles including authentic contexts, spaced practice, and progressive complexity. For teachers, the framework offers a step-by-step approach to unit planning: start with a concept, introduce it through a concrete example, practice with varied contexts, and culminate with pupils applying the concept to an unfamiliar situation.

Stirring the Head, Heart, and Soul: Redefining Curriculum, Instruction, and Concept-Based Learning View study ↗

70 citations

Erickson, H. L. (2007)

In this earlier work, Erickson establishes the theoretical rationale for concept-based learning, drawing on cognitive science research about how the brain organises and retrieves information. She demonstrates that when pupils learn facts in connection with overarching concepts, they build more robust mental models and retain information longer. The book includes practical planning templates that teachers can use to restructure existing units around conceptual themes without starting from scratch.

Is Formal Language Proficiency Required to Profit from a Bilingual Teaching Intervention in Mathematics? View study ↗

57 citations

Schuler-Meyer, A. and Prediger, S. (2019)

Schuler-Meyer and Prediger examine how conceptual understanding develops when pupils learn mathematics through multiple languages, finding that conceptual thinking transcends language barriers. Their study demonstrates that focusing on conceptual understanding rather than procedural fluency benefits multilingual pupils in particular. For teachers in diverse UK classrooms, this research supports using concept-based approaches with EAL pupils, encouraging them to explain mathematical ideas in their strongest language before translating to English.

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/concept-based-learning#article","headline":"Concept-Based Learning","description":"Discover concept-based learning strategies that help pupils connect ideas across subjects, develop critical thinking skills, and achieve deeper understanding.","datePublished":"2024-04-26T13:57:49.404Z","dateModified":"2026-02-15T11:57:58.261Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/concept-based-learning"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/69502cdf5c486b8e18f35f68_cmygu1.webp","wordCount":2612},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/concept-based-learning#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"Concept-Based Learning","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/concept-based-learning"}]}]}