Overjustification Effect

Explore the overjustification effect and how external rewards impact intrinsic motivation. Dive into key studies and insights.

Explore the overjustification effect and how external rewards impact intrinsic motivation. Dive into key studies and insights.

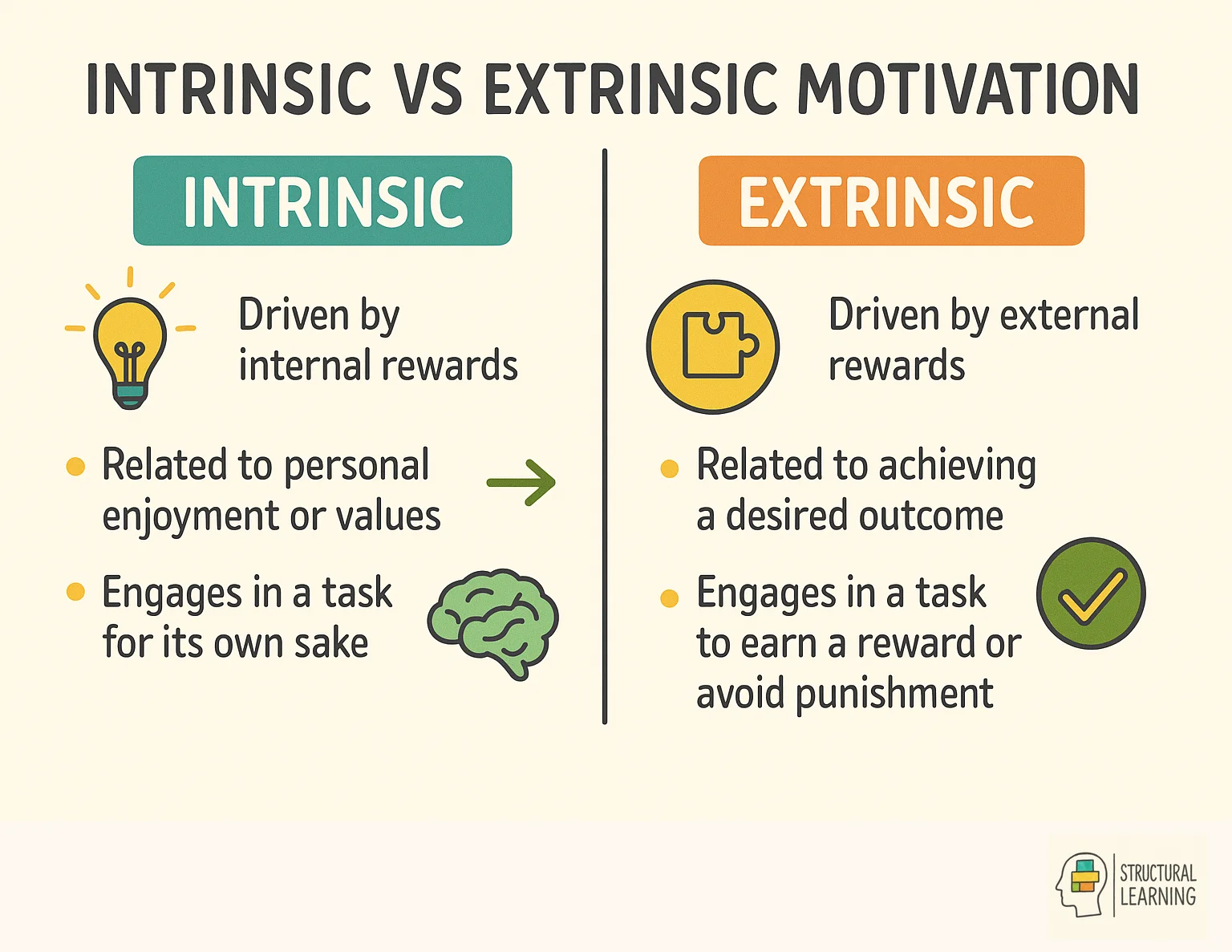

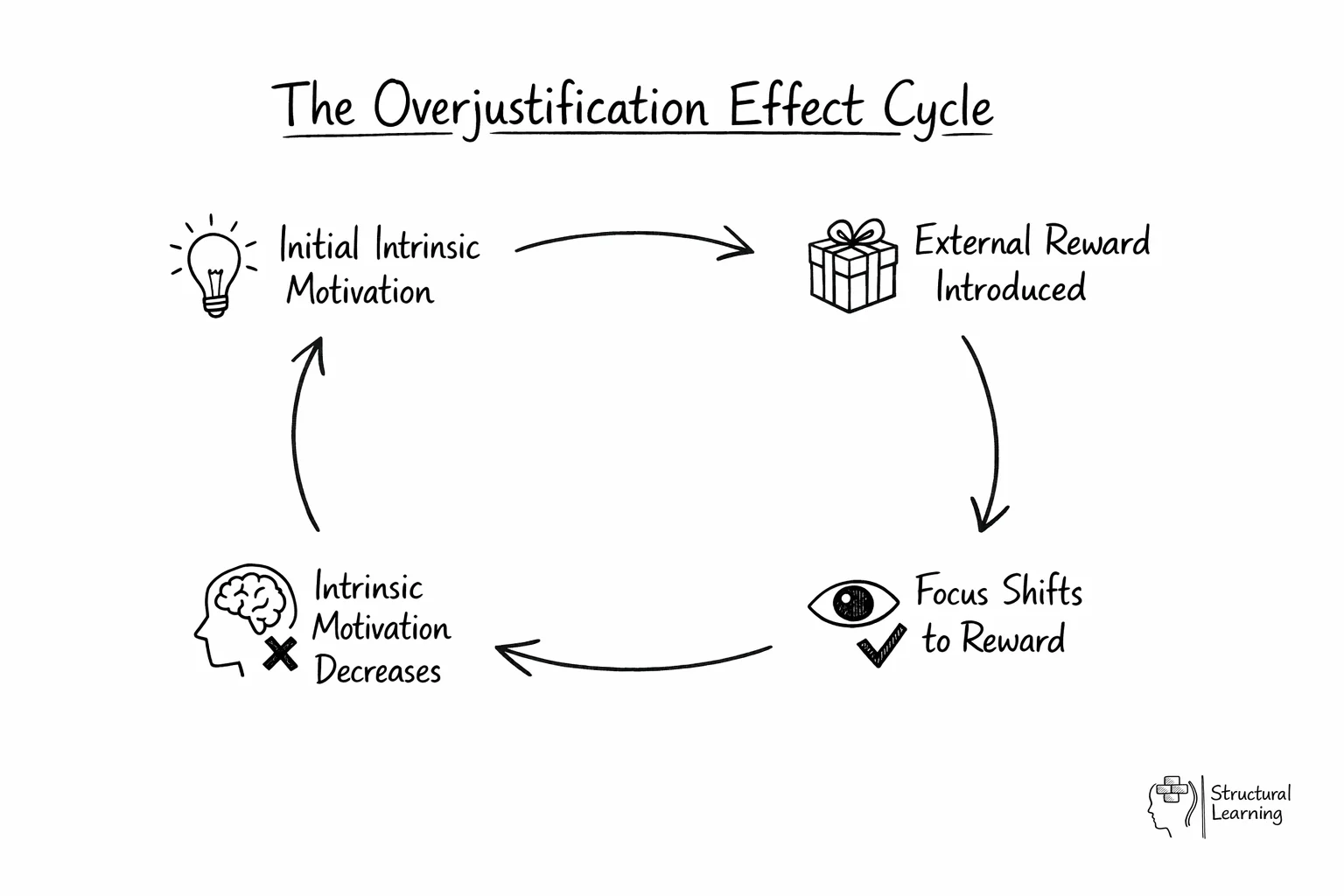

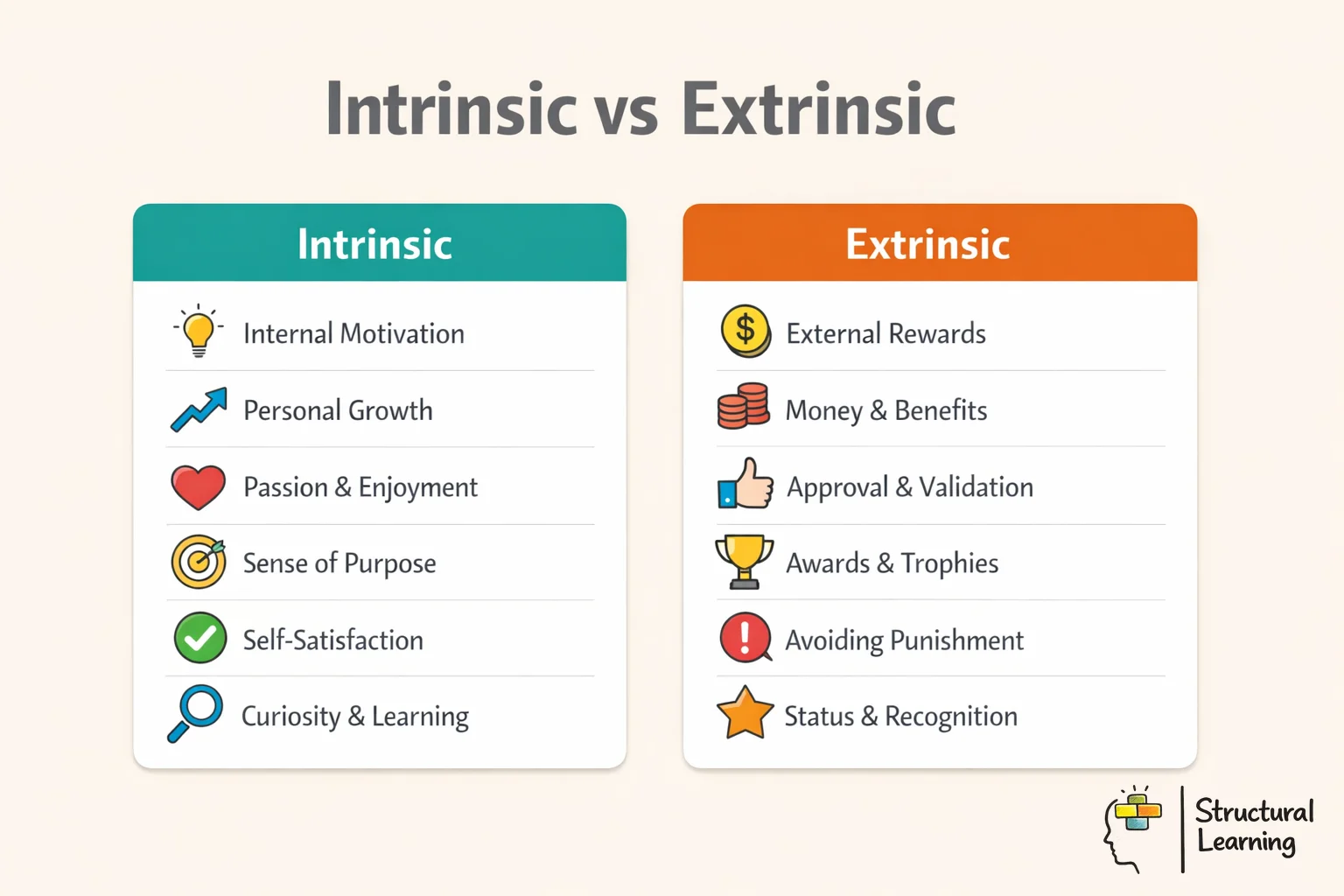

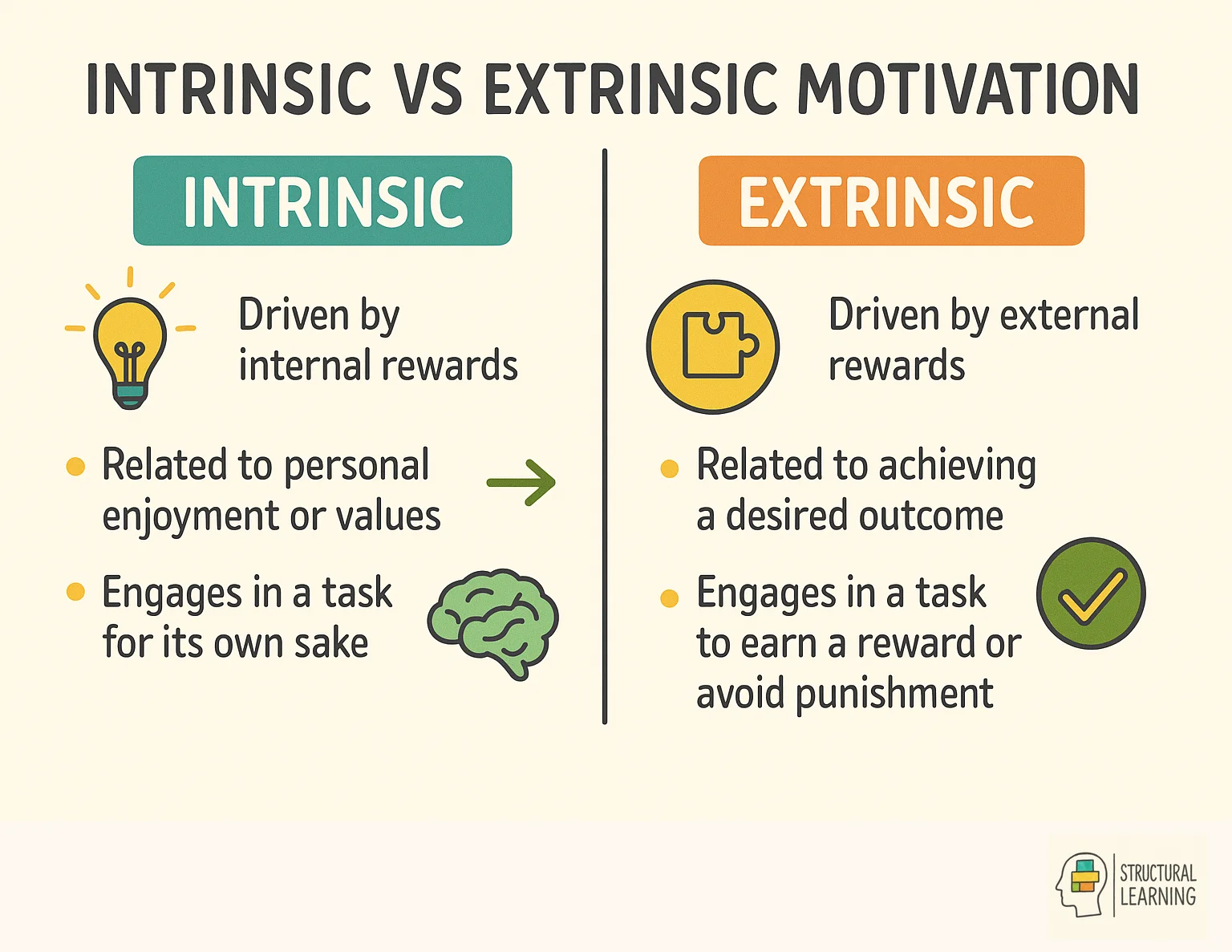

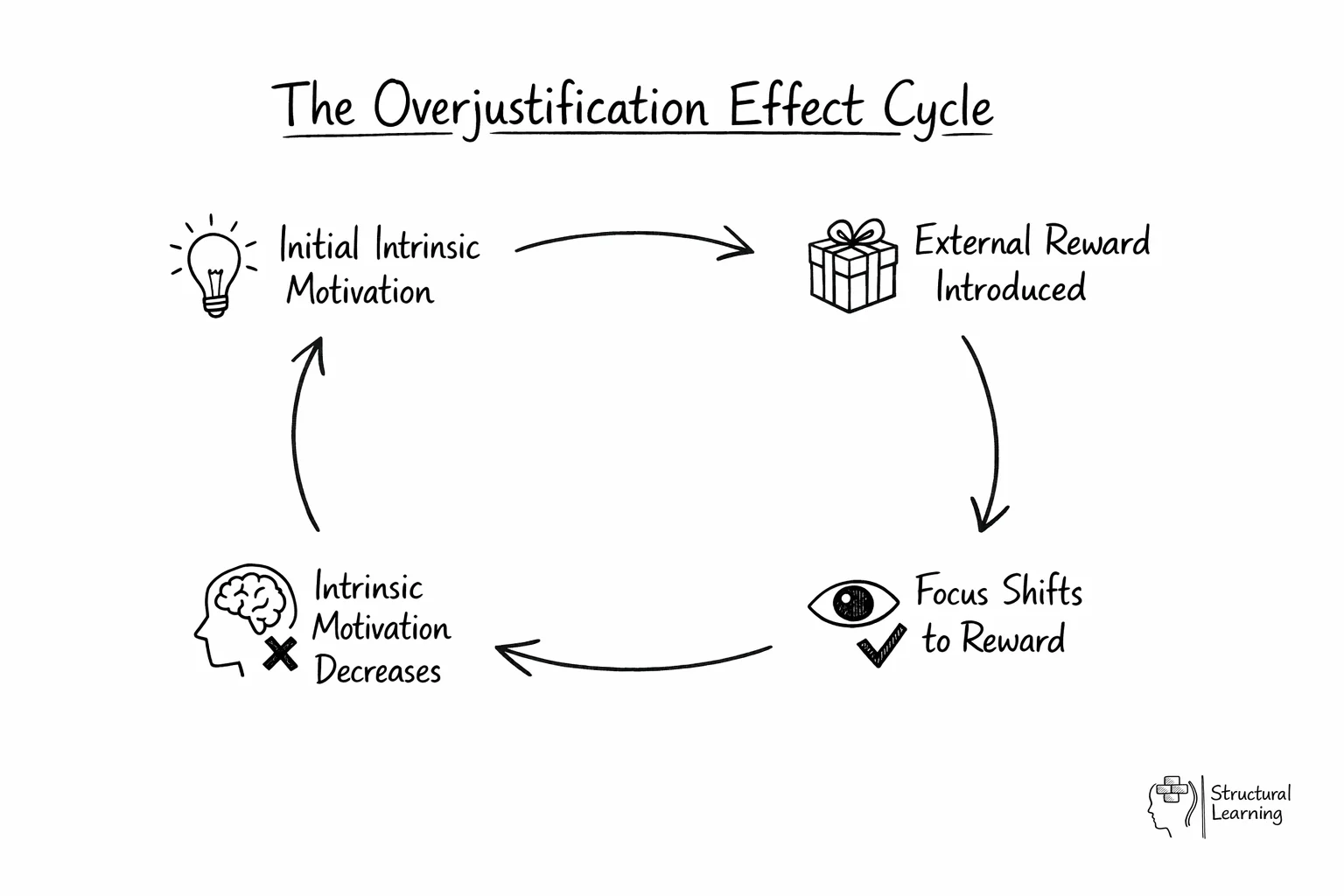

The Overjustification Effect is a psychological phenomenon that occurs when the introduction of external rewards or incentives for engaging in a certain behaviour decreases the individual's intrinsic motivation to engage in that behaviour. In other words, when people are given external rewards for doing something they already enjoy, they may come to see the activity as something they are only doing for the reward rather than for their ownpersonal enjoyment.

This effect can have detrimental effects on individuals' motivation and engagement in certain activities. When intrinsic motivation decreases, individuals may become less interested, passionate, and committed to the activity. This can lead to a decrease in the quality of performance and a decreased desire to further engage in the activity in the future.

According to the Background Information, research has found that the Overjustification Effect is particularly prominent in activities that individuals initially found intrinsically motivating. The presence of extrinsic motivation in the form of rewards or incentives can shift the focus from the inherent enjoyment of the activity to the external rewards, thereby undermining the individual's internal drive.

The overjustification effect manifests differently across various educational contexts and age groups. In secondary schools, research demonstrates that students who initially pursue subjects like art or music for personal satisfaction may lose interest when these activities become heavily focused on assessment grades or external recognition. Mathematics presents a particularly complex case: whilst struggling students may benefit from initial reward structures to build confidence, high-achieving students who already demonstrate intrinsic interest in problem-solving can experience diminished motivation when the same reward systems are applied universally across the classroom.

Effective classroom application requires educators to carefully distinguish between students who need external support to engage and those who are already internally motivated. Practical strategies include using rewards sparingly and strategically, focusing on informational feedback rather than controlling incentives, and gradually transitioning students from external to internal sources of motivation. Research suggests that when rewards are framed as recognition of competence rather than payment for compliance, the negative effects on intrinsic motivation can be minimised whilst still providing necessary support for developing learners.

The overjustification effect refers to a phenomenon where the introduction of extrinsic rewards reduces an individual's intrinsic motivation and passion. When rewards are involved, the dynamics of overjustification come into play and have a significant impact on one's passion.

Rewards can undermine passion and decrease motivation by shifting the focus from the inherent enjoyment of an activity to the external reward itself. This causes individuals to attribute their actions and efforts solely to the external reward, rather than their personal interest or enjoyment. Consequently, their intrinsic motivation decreases, as they no longer engage in the activity for the sake of pure enjoyment.

For example, imagine a child who naturally loves drawing. If they are given a reward, such as a toy, for completing their artwork, their motivation may shift from the joy of creating art to the desire for the reward. In this case, the extrinsic reward undermines the child's intrinsic motivation and passion for drawing.

Another example can be found in the workplace. When employees are offered monetary bonuses for achieving certain targets, their initial motivation might stem from their passion for the job. However, if the rewards become the main driving factor, their intrinsic motivation may fade away, resulting in a decrease in overall passion and commitment to their work.

The neurological mechanisms underlying this motivational shift involve changes in the brain's reward processing systems. When external rewards are introduced, the brain's dopamine pathways, which naturally respond to the inherent satisfaction of learning, begin to orient towards the external reward instead. This neurochemical change helps explain why students may lose interest in subjects they previously enjoyed once grades or other external motivators become the primary focus.

The educational implications extend beyond individual motivation to classroom dynamics. When teachers rely heavily on external rewards, they may inadvertently create competitive environments where learning becomes transactional rather than exploratory. Students begin to ask 'What will I get for this?' rather than 'What can I learn from this?' This shift fundamentally alters the learning culture and can impact peer relationships, risk-taking in learning, and long-term academic engagement.

Research demonstrates that certain reward structures are less likely to undermine intrinsic motivation. Informational feedback that acknowledges competence without creating dependency, unexpected rewards given after task completion, and rewards for participation rather than performance show promise in educational settings. Additionally, allowing students greater autonomy in choosing learning activities and providing opportunities for mastery-oriented goals can help preserve intrinsic motivation whilst still recognising achievement. The key lies in understanding when and how to implement external motivators without compromising students' natural curiosity and love of learning.

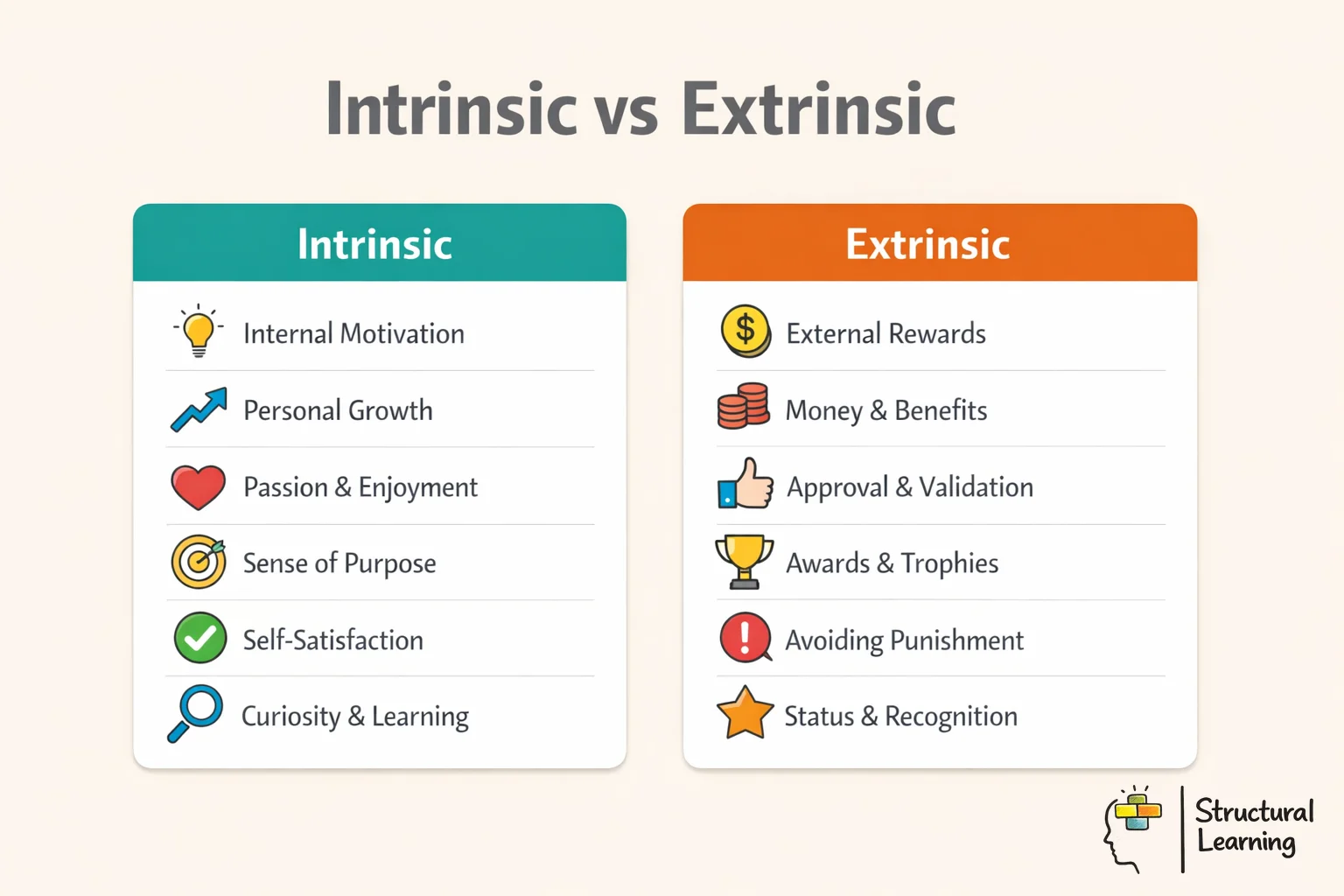

The theoretical foundations of the Overjustification Effect trace back to the early studies of human motivation and the subsequent differentiation between intrinsic and extrinsic rewards. This effect is rooted in the critical distinction between internal motivations, actions driven by inherent interest or pleasure, and external incentives, such as financial rewards or extrinsic reinforcement, that are external to the activity itself.

The journey into understanding overjustification began in the late 1960s and early 1970s with the emergence of cognitive evaluation theory (CET), a sub-theory of self-determination theory. This was a period marked by a keen interest in understanding how feelings of autonomy and internal motivations were affected by external factors. Researchers, particularly Edward Deci at the University of Rochester, initiated experiments that demonstrated the negative effects of external rewards on intrinsic motivation. Deci's seminal work, involving puzzles and college students, found that financial rewards diminished the intrinsic pleasure derived from the activity, laying the groundwork for the overjustification hypothesis.

Building on this, the self-perception theory proposed by Daryl Bem provided another lens through which to view the Overjustification Effect. This theory suggested that individuals infer their internal states, such as their motivations, by observing their behaviour in the context in which it occurs. When external incentives are introduced for activities that people already enjoy, they may begin to attribute their behaviour to these external rewards rather than to their inherent interest. This shift in perception can lead to a decrease in intrinsic motivation, particularly when the external rewards are removed.

Similar to other psychological phenomena like the Dunning-Kruger Effect, which deals with cognitive biases in self-perception, the overjustification effect reveals how our minds can misinterpret the true sources of our behaviour and motivation.

Understanding these theoretical foundations is crucial for educators working with diverse learners, including those with special educational needs, as the impact of rewards and incentives may vary significantly across different student populations. The development of social-emotional learning skills also plays a role in how students process and respond to both intrinsic and extrinsic motivational factors.

Just as the Bystander Effect demonstrates how social context influences individual behaviour, the overjustification effect shows how the presence of external rewards can fundamentally alter our relationship with activities we once found inherently rewarding.

Consider the case of a Year 5 teacher who introduced sticker charts to encourage reading, only to discover that previously enthusiastic readers began viewing books as mere pathways to rewards rather than sources of enjoyment. Research demonstrates that when children who naturally love reading receive external rewards for this behaviour, their intrinsic motivation often diminishes once the rewards cease. This phenomenon, extensively documented by Deci and Ryan's self-determination theory, illustrates how well-intentioned reward systems can inadvertently undermine the very behaviours educators seek to promote.

Another compelling example emerges from mathematics classrooms where teachers implement point-based systems for problem-solving. Students who initially approached challenging mathematical concepts with curiosity and persistence may begin to focus solely on accumulating points rather than developing deep understanding. The quality of engagement shifts from exploratory learning to reward-seeking behaviour, potentially reducing creative problem-solving approaches and mathematical reasoning skills.

To mitigate these effects, educators should emphasise competence and autonomy rather than external rewards. Instead of offering stickers for reading, teachers might facilitate book discussions that highlight students' insights and interpretations. Similarly, mathematics instruction benefits from celebrating the problem-solving process itself, encouraging students to share their reasoning and appreciate the inherent satisfaction of mathematical discovery.

Research demonstrates that teachers can maintain students' intrinsic motivation whilst utilising external rewards through careful implementation strategies. Edward Deci's self-determination theory suggests that rewards should be informational rather than controlling, providing feedback about competence rather than manipulating behaviour. When rewards acknowledge progress, skill development, or effort rather than simple task completion, they enhance rather than undermine intrinsic motivation in educational settings.

Effective prevention strategies include offering unexpected rewards after task completion, as these do not interfere with initial motivation, and using verbal praise that focuses on specific learning processes rather than general ability. Teachers should emphasise the inherent value and relevance of learning activities, helping students understand how tasks connect to their personal goals and interests. Additionally, providing choice and autonomy within structured learning environments allows students to maintain ownership of their learning whilst benefiting from guided instruction.

Practical classroom application involves gradually fading external rewards as intrinsic motivation develops, moving from tangible rewards to social recognition to self-evaluation. Teachers should regularly assess whether external motivators are supporting or replacing natural curiosity, adjusting their approach accordingly to preserve long-term engagement and learning outcomes.

Research demonstrates that informational rewards pose significantly less risk to intrinsic motivation than controlling ones. Edward Deci's self-determination theory reveals that rewards providing feedback about competence, such as "Your essay shows excellent critical thinking skills," support learners' psychological needs rather than undermining them. These acknowledgements focus on specific achievements and learning progress, helping students understand their developing expertise without creating dependency on external validation.

Similarly, unexpected rewards preserve intrinsic motivation because learners cannot anticipate them during task engagement. When students receive surprise recognition after completing work they found inherently engaging, the reward functions as genuine appreciation rather than a controlling mechanism. Additionally, rewards for creative or open-ended tasks prove less harmful than those for routine activities, as the complexity of creative work makes it harder for external incentives to overshadow internal satisfaction.

In classroom application, educators should favour process-focused acknowledgement over outcome-based rewards. Rather than rewarding reading with prizes, teachers might comment on students' thoughtful questions about characters or themes. This approach maintains focus on the learning journey whilst providing the social recognition that supports continued engagement in educational settings.

Research demonstrates that the overjustification effect manifests differently across age groups and personality types, requiring educators to adopt nuanced approaches to motivation. Younger children, particularly those in primary school, show greater susceptibility to motivational undermining when external rewards are removed, as their developing cognitive systems rely more heavily on immediate, tangible feedback. Conversely, adolescents and adults possess more sophisticated self-regulatory mechanisms, though individual differences in personality traits such as autonomy orientation and intrinsic goal orientation significantly influence their responses to external incentives.

Students with high levels of intrinsic motivation and strong autonomy preferences demonstrate the most pronounced overjustification effects, whilst those with lower baseline intrinsic interest may actually benefit from carefully structured reward systems. Additionally, learners with performance-oriented mindsets respond differently to external rewards compared to those with mastery-oriented approaches, suggesting that understanding individual motivational profiles is crucial for effective classroom management.

Practically, educators should assess students' developmental stages and motivational orientations before implementing reward structures. For intrinsically motivated older students, emphasis should be placed on choice, competence feedback, and meaningful connections rather than tangible rewards. For younger learners or those with lower intrinsic interest, graduated reward removal and increased emphasis on skill development can help transition towards more autonomous motivation whilst preserving engagement.

The Overjustification Effect is a psychological phenomenon that occurs when the introduction of external rewards or incentives for engaging in a certain behaviour decreases the individual's intrinsic motivation to engage in that behaviour. In other words, when people are given external rewards for doing something they already enjoy, they may come to see the activity as something they are only doing for the reward rather than for their ownpersonal enjoyment.

This effect can have detrimental effects on individuals' motivation and engagement in certain activities. When intrinsic motivation decreases, individuals may become less interested, passionate, and committed to the activity. This can lead to a decrease in the quality of performance and a decreased desire to further engage in the activity in the future.

According to the Background Information, research has found that the Overjustification Effect is particularly prominent in activities that individuals initially found intrinsically motivating. The presence of extrinsic motivation in the form of rewards or incentives can shift the focus from the inherent enjoyment of the activity to the external rewards, thereby undermining the individual's internal drive.

The overjustification effect manifests differently across various educational contexts and age groups. In secondary schools, research demonstrates that students who initially pursue subjects like art or music for personal satisfaction may lose interest when these activities become heavily focused on assessment grades or external recognition. Mathematics presents a particularly complex case: whilst struggling students may benefit from initial reward structures to build confidence, high-achieving students who already demonstrate intrinsic interest in problem-solving can experience diminished motivation when the same reward systems are applied universally across the classroom.

Effective classroom application requires educators to carefully distinguish between students who need external support to engage and those who are already internally motivated. Practical strategies include using rewards sparingly and strategically, focusing on informational feedback rather than controlling incentives, and gradually transitioning students from external to internal sources of motivation. Research suggests that when rewards are framed as recognition of competence rather than payment for compliance, the negative effects on intrinsic motivation can be minimised whilst still providing necessary support for developing learners.

The overjustification effect refers to a phenomenon where the introduction of extrinsic rewards reduces an individual's intrinsic motivation and passion. When rewards are involved, the dynamics of overjustification come into play and have a significant impact on one's passion.

Rewards can undermine passion and decrease motivation by shifting the focus from the inherent enjoyment of an activity to the external reward itself. This causes individuals to attribute their actions and efforts solely to the external reward, rather than their personal interest or enjoyment. Consequently, their intrinsic motivation decreases, as they no longer engage in the activity for the sake of pure enjoyment.

For example, imagine a child who naturally loves drawing. If they are given a reward, such as a toy, for completing their artwork, their motivation may shift from the joy of creating art to the desire for the reward. In this case, the extrinsic reward undermines the child's intrinsic motivation and passion for drawing.

Another example can be found in the workplace. When employees are offered monetary bonuses for achieving certain targets, their initial motivation might stem from their passion for the job. However, if the rewards become the main driving factor, their intrinsic motivation may fade away, resulting in a decrease in overall passion and commitment to their work.

The neurological mechanisms underlying this motivational shift involve changes in the brain's reward processing systems. When external rewards are introduced, the brain's dopamine pathways, which naturally respond to the inherent satisfaction of learning, begin to orient towards the external reward instead. This neurochemical change helps explain why students may lose interest in subjects they previously enjoyed once grades or other external motivators become the primary focus.

The educational implications extend beyond individual motivation to classroom dynamics. When teachers rely heavily on external rewards, they may inadvertently create competitive environments where learning becomes transactional rather than exploratory. Students begin to ask 'What will I get for this?' rather than 'What can I learn from this?' This shift fundamentally alters the learning culture and can impact peer relationships, risk-taking in learning, and long-term academic engagement.

Research demonstrates that certain reward structures are less likely to undermine intrinsic motivation. Informational feedback that acknowledges competence without creating dependency, unexpected rewards given after task completion, and rewards for participation rather than performance show promise in educational settings. Additionally, allowing students greater autonomy in choosing learning activities and providing opportunities for mastery-oriented goals can help preserve intrinsic motivation whilst still recognising achievement. The key lies in understanding when and how to implement external motivators without compromising students' natural curiosity and love of learning.

The theoretical foundations of the Overjustification Effect trace back to the early studies of human motivation and the subsequent differentiation between intrinsic and extrinsic rewards. This effect is rooted in the critical distinction between internal motivations, actions driven by inherent interest or pleasure, and external incentives, such as financial rewards or extrinsic reinforcement, that are external to the activity itself.

The journey into understanding overjustification began in the late 1960s and early 1970s with the emergence of cognitive evaluation theory (CET), a sub-theory of self-determination theory. This was a period marked by a keen interest in understanding how feelings of autonomy and internal motivations were affected by external factors. Researchers, particularly Edward Deci at the University of Rochester, initiated experiments that demonstrated the negative effects of external rewards on intrinsic motivation. Deci's seminal work, involving puzzles and college students, found that financial rewards diminished the intrinsic pleasure derived from the activity, laying the groundwork for the overjustification hypothesis.

Building on this, the self-perception theory proposed by Daryl Bem provided another lens through which to view the Overjustification Effect. This theory suggested that individuals infer their internal states, such as their motivations, by observing their behaviour in the context in which it occurs. When external incentives are introduced for activities that people already enjoy, they may begin to attribute their behaviour to these external rewards rather than to their inherent interest. This shift in perception can lead to a decrease in intrinsic motivation, particularly when the external rewards are removed.

Similar to other psychological phenomena like the Dunning-Kruger Effect, which deals with cognitive biases in self-perception, the overjustification effect reveals how our minds can misinterpret the true sources of our behaviour and motivation.

Understanding these theoretical foundations is crucial for educators working with diverse learners, including those with special educational needs, as the impact of rewards and incentives may vary significantly across different student populations. The development of social-emotional learning skills also plays a role in how students process and respond to both intrinsic and extrinsic motivational factors.

Just as the Bystander Effect demonstrates how social context influences individual behaviour, the overjustification effect shows how the presence of external rewards can fundamentally alter our relationship with activities we once found inherently rewarding.

Consider the case of a Year 5 teacher who introduced sticker charts to encourage reading, only to discover that previously enthusiastic readers began viewing books as mere pathways to rewards rather than sources of enjoyment. Research demonstrates that when children who naturally love reading receive external rewards for this behaviour, their intrinsic motivation often diminishes once the rewards cease. This phenomenon, extensively documented by Deci and Ryan's self-determination theory, illustrates how well-intentioned reward systems can inadvertently undermine the very behaviours educators seek to promote.

Another compelling example emerges from mathematics classrooms where teachers implement point-based systems for problem-solving. Students who initially approached challenging mathematical concepts with curiosity and persistence may begin to focus solely on accumulating points rather than developing deep understanding. The quality of engagement shifts from exploratory learning to reward-seeking behaviour, potentially reducing creative problem-solving approaches and mathematical reasoning skills.

To mitigate these effects, educators should emphasise competence and autonomy rather than external rewards. Instead of offering stickers for reading, teachers might facilitate book discussions that highlight students' insights and interpretations. Similarly, mathematics instruction benefits from celebrating the problem-solving process itself, encouraging students to share their reasoning and appreciate the inherent satisfaction of mathematical discovery.

Research demonstrates that teachers can maintain students' intrinsic motivation whilst utilising external rewards through careful implementation strategies. Edward Deci's self-determination theory suggests that rewards should be informational rather than controlling, providing feedback about competence rather than manipulating behaviour. When rewards acknowledge progress, skill development, or effort rather than simple task completion, they enhance rather than undermine intrinsic motivation in educational settings.

Effective prevention strategies include offering unexpected rewards after task completion, as these do not interfere with initial motivation, and using verbal praise that focuses on specific learning processes rather than general ability. Teachers should emphasise the inherent value and relevance of learning activities, helping students understand how tasks connect to their personal goals and interests. Additionally, providing choice and autonomy within structured learning environments allows students to maintain ownership of their learning whilst benefiting from guided instruction.

Practical classroom application involves gradually fading external rewards as intrinsic motivation develops, moving from tangible rewards to social recognition to self-evaluation. Teachers should regularly assess whether external motivators are supporting or replacing natural curiosity, adjusting their approach accordingly to preserve long-term engagement and learning outcomes.

Research demonstrates that informational rewards pose significantly less risk to intrinsic motivation than controlling ones. Edward Deci's self-determination theory reveals that rewards providing feedback about competence, such as "Your essay shows excellent critical thinking skills," support learners' psychological needs rather than undermining them. These acknowledgements focus on specific achievements and learning progress, helping students understand their developing expertise without creating dependency on external validation.

Similarly, unexpected rewards preserve intrinsic motivation because learners cannot anticipate them during task engagement. When students receive surprise recognition after completing work they found inherently engaging, the reward functions as genuine appreciation rather than a controlling mechanism. Additionally, rewards for creative or open-ended tasks prove less harmful than those for routine activities, as the complexity of creative work makes it harder for external incentives to overshadow internal satisfaction.

In classroom application, educators should favour process-focused acknowledgement over outcome-based rewards. Rather than rewarding reading with prizes, teachers might comment on students' thoughtful questions about characters or themes. This approach maintains focus on the learning journey whilst providing the social recognition that supports continued engagement in educational settings.

Research demonstrates that the overjustification effect manifests differently across age groups and personality types, requiring educators to adopt nuanced approaches to motivation. Younger children, particularly those in primary school, show greater susceptibility to motivational undermining when external rewards are removed, as their developing cognitive systems rely more heavily on immediate, tangible feedback. Conversely, adolescents and adults possess more sophisticated self-regulatory mechanisms, though individual differences in personality traits such as autonomy orientation and intrinsic goal orientation significantly influence their responses to external incentives.

Students with high levels of intrinsic motivation and strong autonomy preferences demonstrate the most pronounced overjustification effects, whilst those with lower baseline intrinsic interest may actually benefit from carefully structured reward systems. Additionally, learners with performance-oriented mindsets respond differently to external rewards compared to those with mastery-oriented approaches, suggesting that understanding individual motivational profiles is crucial for effective classroom management.

Practically, educators should assess students' developmental stages and motivational orientations before implementing reward structures. For intrinsically motivated older students, emphasis should be placed on choice, competence feedback, and meaningful connections rather than tangible rewards. For younger learners or those with lower intrinsic interest, graduated reward removal and increased emphasis on skill development can help transition towards more autonomous motivation whilst preserving engagement.

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/overjustification-effect#article","headline":"Overjustification Effect","description":"Explore the overjustification effect and how external rewards impact intrinsic motivation. Dive into key studies and insights.","datePublished":"2024-04-04T10:33:17.181Z","dateModified":"2026-01-26T10:09:32.212Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/overjustification-effect"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/69513240194dca7ffd65cbb4_7btp7r.webp","wordCount":2815},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/overjustification-effect#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"Overjustification Effect","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/overjustification-effect"}]},{"@type":"FAQPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/overjustification-effect#faq","mainEntity":[{"@type":"Question","name":"What is the Overjustification Effect and why should educators be concerned about it?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"The Overjustification Effect occurs when external rewards decrease a person's intrinsic motivation for activities they already enjoy naturally. When children receive rewards for behaviours they find inherently satisfying, they may begin to see the activity as something they only do for the reward ra"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"How can teachers identify if their reward systems are undermining pupils' intrinsic motivation?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Warning signs include pupils losing interest in activities once rewards are removed, decreased quality of work despite receiving rewards, or children asking 'what do I get for this?' before engaging in previously enjoyed tasks. Teachers should also watch for reduced creativity, passion, or engagemen"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What types of rewards actually enhance motivation rather than undermine it?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Rewards that foster competence and autonomy, such as opportunities for skill development, public recognition of progress, or chances to share expertise with others, tend to enhance intrinsic motivation. These rewards should align with pupils' interests and values, complementing the activity rather t"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"Can you provide practical examples of how the Overjustification Effect might occur in a classroom setting?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"A child who naturally loves drawing may lose interest in art if consistently rewarded with toys for completing artwork, shifting their focus from creative joy to reward acquisition. Similarly, pupils who enjoy reading might become less motivated to read independently if they only associate reading w"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"How can teachers maintain pupils' intrinsic motivation whilst still providing recognition for good work?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Teachers should focus on celebrating growth and mastery rather than simply rewarding task completion, offering recognition that enhances pupils' sense of accomplishment. Strategies include providing meaningful feedback about progress, creating opportunities for pupils to showcase their learning to a"}}]}]}