Social Contract Theory

Discover how social contract theory transforms classroom management through collaborative rule-making, student buy-in, and democratic principles that work.

Discover how social contract theory transforms classroom management through collaborative rule-making, student buy-in, and democratic principles that work.

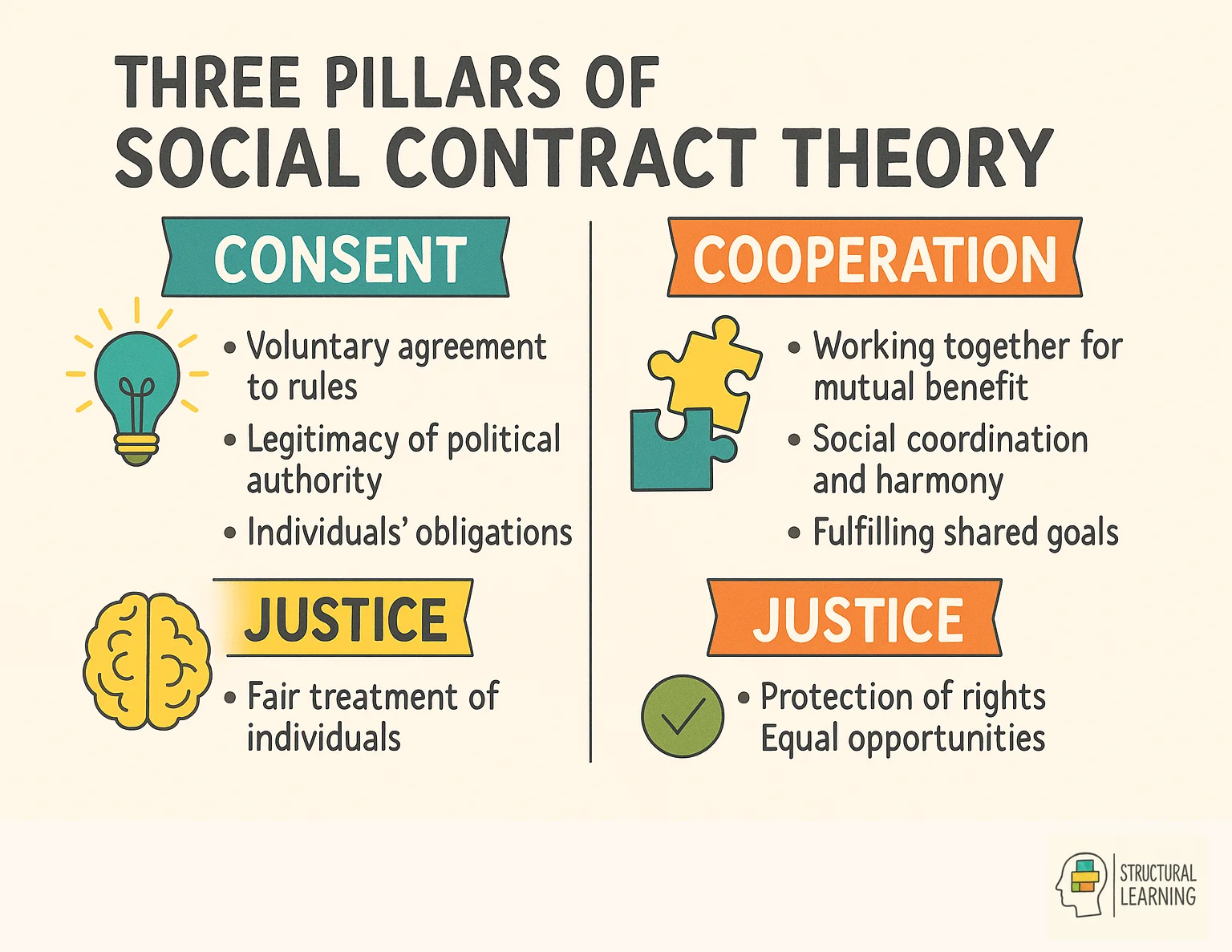

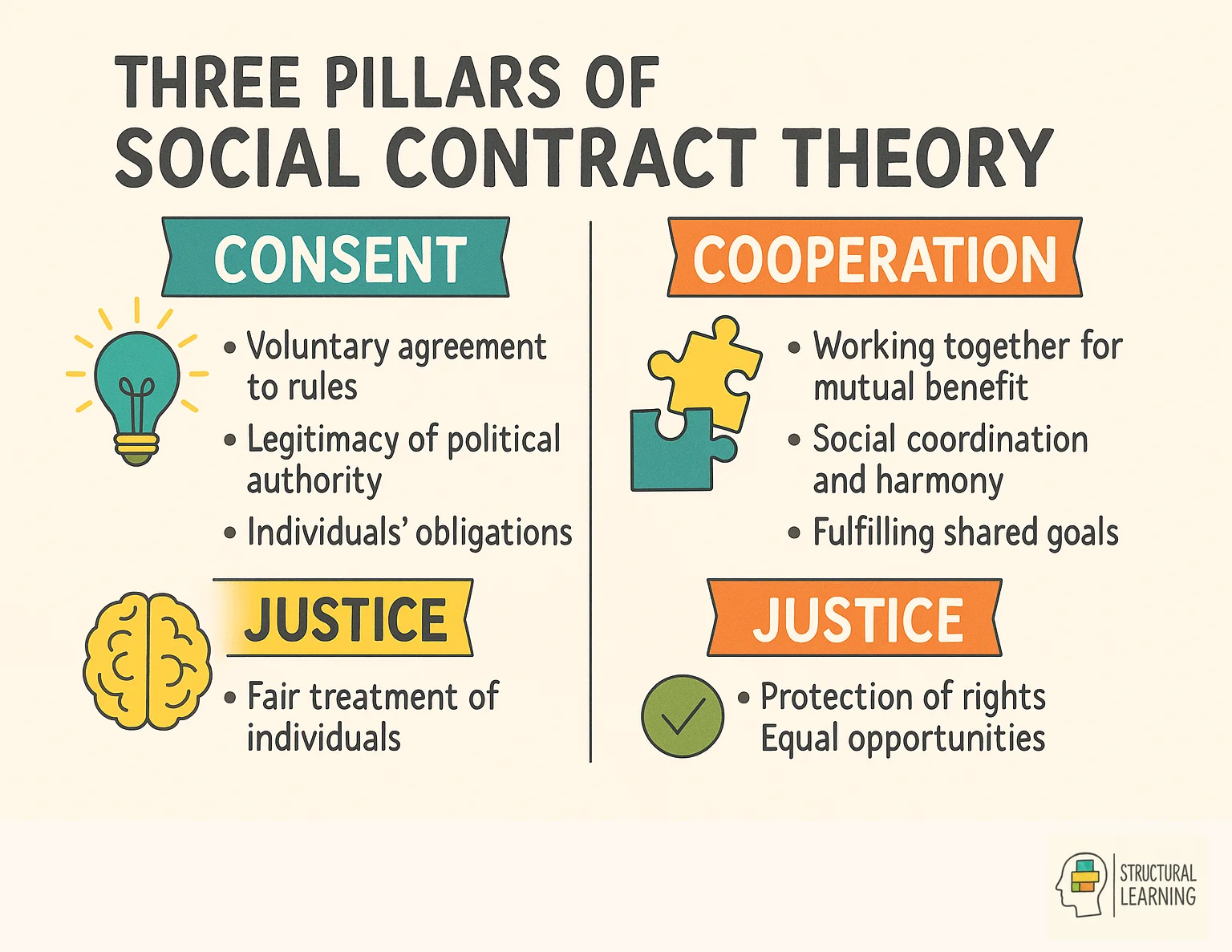

Social Contract Theory, a cornerstone in the edifice of , offers a window into the intricate relationship between individual people and societal structures. At its core, this theory posits that members of a society implicitly agree to surrender some freedoms to authority figures in exchange for protection of their remaining rights. This conceptual framework, championed by social contract theorists, explores into the origins of moral and political order, examining how collective agreements shape human life.

The theory's roots can be traced back to the Enlightenment era, where thinkers like John Locke and Jean-Jacques Rousseau pondered over the human condition in a 'state of nature', a hypothetical life without political institutions. They argued that rational individuals would agree to form a society governed by mutual obligations, moving away from the brutish, solitary life that characterises the state of nature. This transition, according to them, is guided by an inherent understanding of moral codes and the laws of nature.

In the 20th century, John Rawls revitalized the theory with his ' theory of justice', which reimagined the social contract as a fair agreement among equals. Rawls' perspective underscores the role of moral persons in shaping a just society, where political power is exercised in ways that are beneficial to all, especially the least advantaged. His ideas resonate profoundly in modern society, where equity and fairness in educational and political institutions are increasingly scrutinized.

Social Contract Theory offers a lens to view the evolution of societal norms and the balance between individual liberty and collective good. It remains a dominant theory in understanding the philosophical underpinnings of modern governance and social structures.

Key ideas to explore:

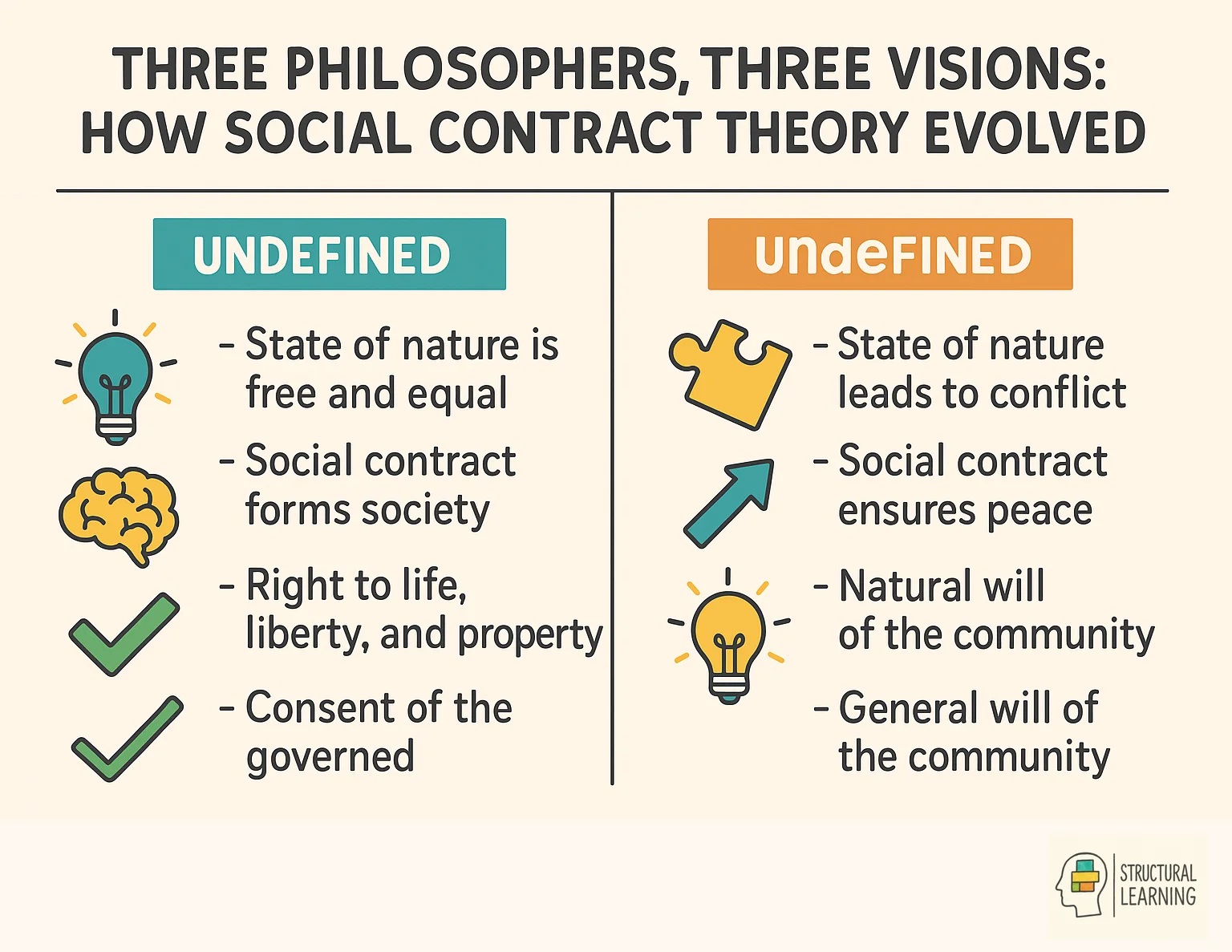

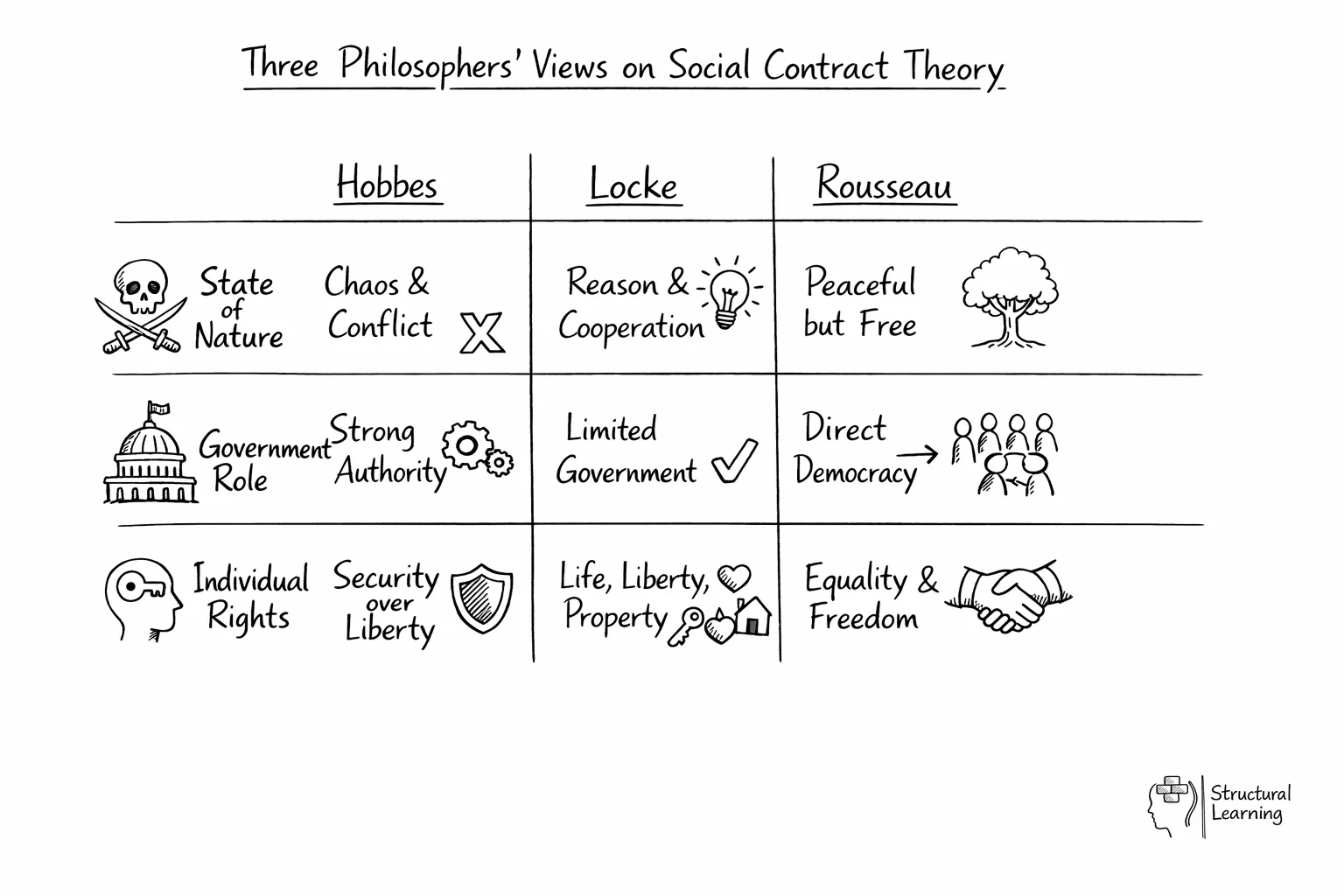

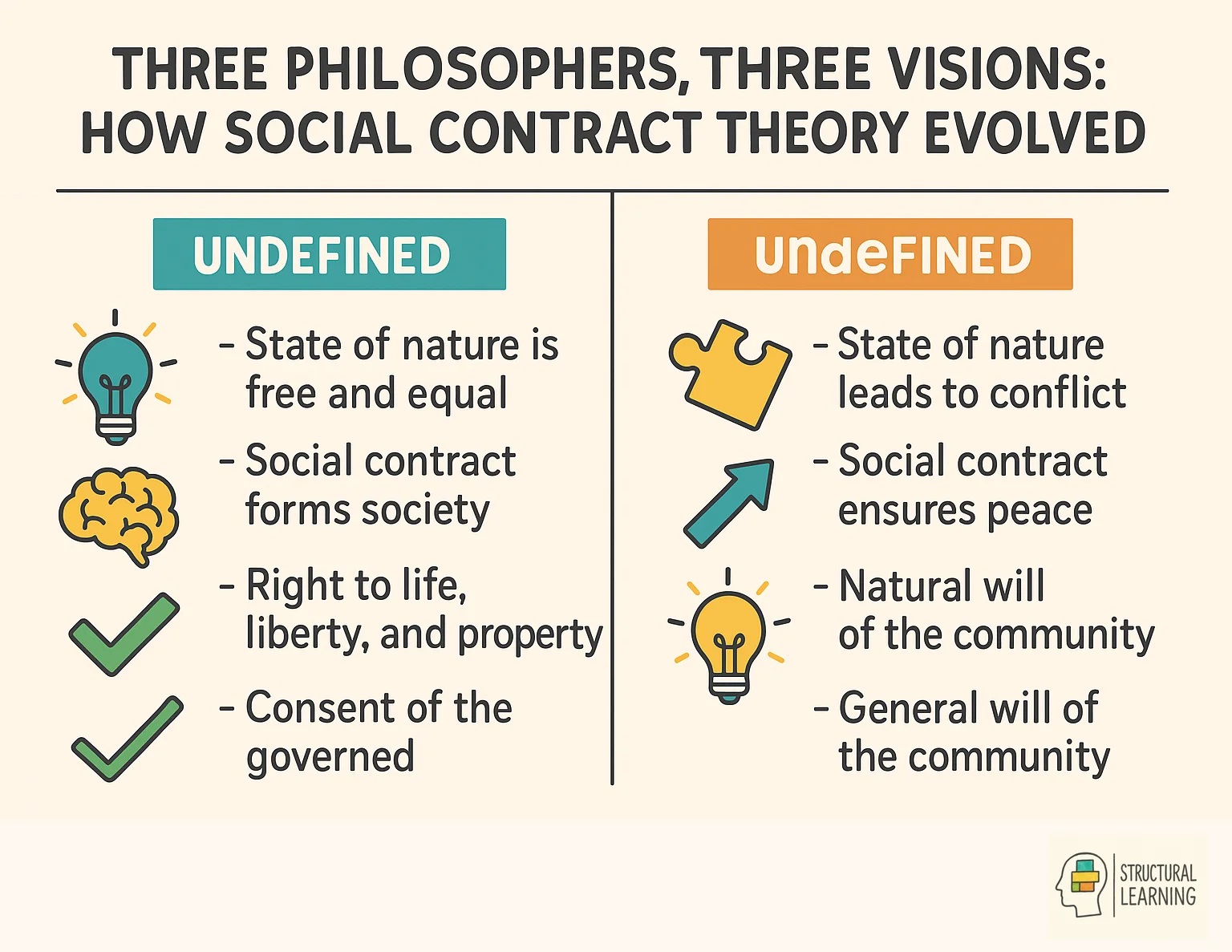

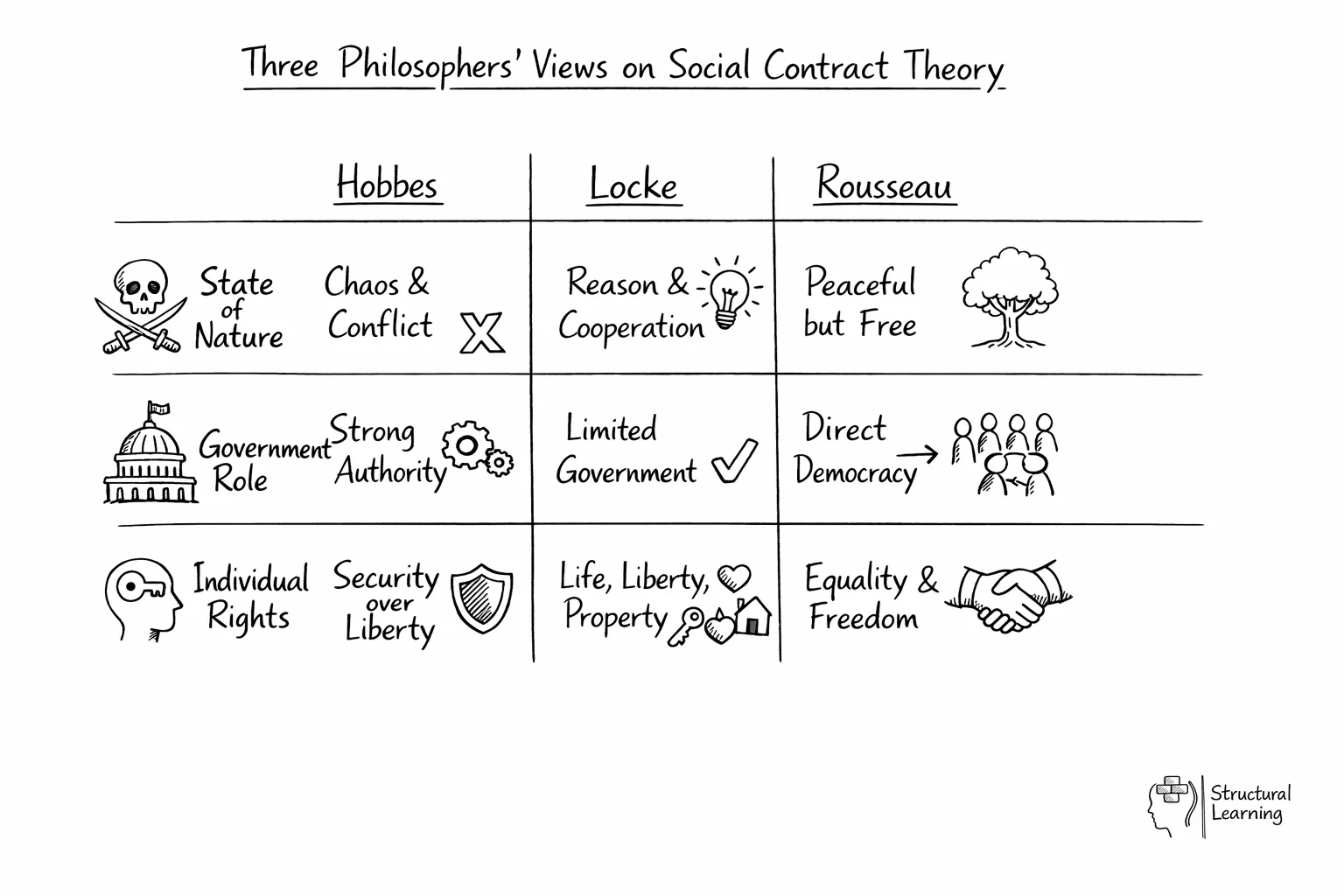

Hobbes, Locke, and Rousseau each developed distinct versions of social contract theory that differ fundamentally in their views of human nature, government legitimacy, and individual rights.

The history of social contract theory dates back to ancient Greece, with the contributions of Socrates. Socrates believed that individuals enter into a social contract voluntarily in order to establish a just and moral society. However, it was Thomas Hobbes who popularized the concept of social contract theory in the 17th century.

Hobbes argued that in a state of nature, without any governing authority, individuals would suffer a constant fear of violent death. To avoid this, they willingly enter into a social contract where they surrender certain freedoms to a sovereign ruler in exchange for protection and security.

This idea was further developed by John Locke in the 17th century. Locke emphasised the importance of individual rights and believed that the purpose of the social contract was to protect these rights. He argued that if a government failed to do so, individuals had the right to rebel and establish a new social contract.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau contributed to the theory in the 18th century with his idea of the "general will." He believed that in order for a society to be just, decisions should be made collectively, considering the common good rather than individual interests. This emphasis on collective decision-making connects to modern concepts of social-emotional learning in educational contexts.

Overall, social contract theory proposes that moral and political obligations are dependent on a contract or agreement among individuals to form a society. This theory has shaped modern political thought and continues to be relevant in discussions on governance and individual rights. In educational settings, these principles inform classroom management approaches that emphasise shared responsibility and student engagement in creating learning environments.

Social contract theory examines into the fundamental questions of political legitimacy, individual rights, and the moral foundations of society. Understanding this theory is crucial for educators, as its principles directly influence classroom management, student engagement, and the cultivation of democratic values.

Here are some key theorists:

Social Contract Theory provides a strong framework for educators to establish ethical and effective learning environments. By understanding the core principles of this theory, teachers can create classrooms that promote fairness, respect, and shared responsibility.

Here are some practical applications:

Effective pedagogical approaches include using current events to illustrate social contract principles in action. For instance, discussions about taxation, public services, or emergency powers during crises can help students understand how citizens consent to government authority in exchange for protection and services. Role-playing activities where students negotiate classroom rules or simulate constitutional conventions can make abstract concepts tangible and accessible to learners of different ages.

Educators should also encourage students to examine different cultural and historical contexts for social contracts. Comparing democratic systems with other forms of governance helps students appreciate the voluntary nature of democratic participation whilst developing analytical skills for evaluating political systems. Cross-curricular connections with history, literature, and contemporary studies can reinforce understanding of how social contract theory influences modern civic life.

Assessment strategies might include debates about competing visions of the social contract, analytical essays examining real-world applications, or collaborative projects exploring how different societies structure their political agreements. Such approaches ensure that students not only grasp theoretical concepts but can apply social contract theory to evaluate contemporary political developments and their own roles as democratic citizens.

Understanding social contract theory requires examining four pivotal thinkers whose ideas fundamentally shaped modern political philosophy. Thomas Hobbes argued that without government, human life would be "solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short," necessitating a powerful sovereign to maintain order. John Locke countered with a more optimistic view, proposing that individuals surrender some freedoms to protect their natural rights to life, liberty, and property. Jean-Jacques Rousseau famously declared that "man is born free, and everywhere he is in chains," advocating for a social contract that preserves individual freedom whilst creating collective will.

John Rawls transformed twentieth-century political theory with his "veil of ignorance" concept, where rational individuals design a just society without knowing their position within it. This thought experiment powerfully demonstrates how fairness emerges when self-interest is temporarily suspended. Each theorist's contribution offers educators distinct pedagogical opportunities: Hobbes illustrates the necessity of rules, Locke emphasises individual rights, Rousseau explores democratic participation, and Rawls provides a framework for discussing justice and equality.

In classroom practise, educators can engage students by presenting scenarios that mirror these philosophical positions. Asking students to design classroom rules using Rawls' approach, or debating Hobbes versus Locke regarding school governance, transforms abstract theory into concrete understanding of democratic citizenship and civic responsibility.

Social contract theory emerged during the 17th and 18th centuries as Enlightenment philosophers grappled with fundamental questions about political authority and individual rights. This intellectual movement arose partly as a response to the absolute monarchies that dominated Europe, where rulers claimed divine right to govern without consent from their subjects. Educators should emphasise to students that these theories weren't merely abstract philosophical exercises, but urgent attempts to understand and justify political power during periods of civil war, revolution, and social upheaval.

The historical context becomes particularly valuable when teaching students about the evolution of democratic thought. Thomas Hobbes wrote during the English Civil War, influencing his pessimistic view of human nature, whilst John Locke's theories emerged after the Glorious Revolution of 1688, reflecting more optimistic possibilities for constitutional government. Jean-Jacques Rousseau's contributions came during the intellectual ferment preceding the French Revolution, emphasising popular sovereignty and the general will.

In the classroom, educators can help students understand these theories by connecting them to specific historical crises and social transformations. Consider using timeline activities that juxtapose major political events with the publication of key texts, enabling students to see how political philosophy responds to real-world challenges. This approach demonstrates that democratic institutions and civic rights emerged through centuries of intellectual struggle and practical experimentation.

Effective instruction in social contract theory requires scaffolded learning approaches that move students from concrete examples to abstract philosophical concepts. Begin with familiar scenarios such as classroom rules or school policies, helping students recognise that these represent agreements between individuals for mutual benefit. Role-playing activities prove particularly valuable, where students negotiate hypothetical social contracts for desert island scenarios or new communities, experiencing firsthand the tensions between individual freedom and collective security that Hobbes, Locke, and Rousseau explored.

Comparative analysis exercises allow students to examine different philosophers' perspectives systematically. Create structured comparison charts where students evaluate how each theorist would approach contemporary issues such as digital privacy, environmental protection, or pandemic responses. Jerome Bruner's constructivist theory supports this approach, as students build understanding by connecting new philosophical concepts to current events and personal experiences.

Assessment strategies should emphasise critical thinking over rote memorisation. Design tasks requiring students to apply social contract principles to real-world situations, such as analysing school policies or local government decisions. Socratic seminars encourage deep discussion whilst developing civic engagement skills essential for democratic citizenship. These methods ensure that students not only understand theoretical concepts but can also articulate how social contract theory remains relevant to modern democratic society.

Social Contract Theory offers a compelling framework for understanding the relationship between individuals and society. From the ancient ideas of Socrates to the modern interpretations of John Rawls, this theory has shaped political thought and continues to influence contemporary debates on governance and individual rights.

For educators, Social Contract Theory provides invaluable insights into creating ethical and effective learning environments. By applying the principles of shared responsibility, mutual respect, and democratic participation, teachers can cultivate classrooms that helps students to become engaged, responsible, and critically thinking members of society. Embracing this theory allows educators to move beyond traditional authority-based approaches, developing a collaborative environment where every student feels valued and heard.

Four thinkers fundamentally shaped our understanding of social contracts, each offering distinct perspectives that directly inform modern classroom dynamics. Thomas Hobbes painted humanity as naturally selfish and violent, arguing that without strong authority, life would be 'solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short'. His vision translates to classrooms where strict rules prevent chaos; think of supply teachers walking into unfamiliar classes where established authority structures have temporarily dissolved.

John Locke offered a more optimistic view, proposing that people possess natural rights to life, liberty, and property. In Lockean classrooms, teachers act as facilitators rather than enforcers, establishing rules through discussion rather than decree. When Year 9 students collaboratively create their own behaviour contracts at term's start, they're embodying Locke's belief that legitimate authority stems from consent, not force.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau believed humans were naturally good but corrupted by society, advocating for education that preserves this innate goodness. His concept of the 'general will' manifests when entire classes vote on reward systems or collectively decide consequences for disruption. Modern restorative justice practices in schools, where students help determine fair outcomes for misbehaviour, echo Rousseau's vision of collective decision-making.

John Rawls brought social contract theory into contemporary times with his 'veil of ignorance' thought experiment. He asked: what rules would we choose if we didn't know our position in society? Teachers can apply this by having students design classroom policies whilst imagining they could be anyone in the room; the quiet student, the class clown, or someone with learning difficulties. This exercise reveals how fairness emerges when self-interest is removed from rule-making.

Teachers can facilitate collaborative rule-making sessions where students negotiate and agree upon classroom expectations together. This approach mirrors the consent principle by ensuring students have genuine input into the social contract that governs their learning environment. The resulting rules carry more weight because students helped create them rather than having them imposed from above.

Primary school children (ages 7-11) can grasp basic ideas about fairness and agreements through simplified discussions about classroom communities. Secondary students (ages 11-18) can engage with more complex concepts like individual rights versus collective responsibility. Even young children naturally understand the concept of 'fair trades' which forms the foundation of social contract thinking.

When behaviour issues arise, teachers can refer back to the collectively agreed classroom contract rather than relying solely on external authority. This approach helps students understand that rule-breaking affects the community they helped create, fostering accountability and reflection. It also provides a framework for discussing why certain behaviours undermine the social agreement everyone consented to follow.

Teachers can use mock parliamentary debates, classroom constitution-writing exercises, and role-playing scenarios about desert island survival to illustrate social contract principles. Group project negotiations and peer mediation sessions also demonstrate how individuals surrender some freedoms for collective benefits. These hands-on activities make abstract philosophical concepts tangible and relevant to students' daily experiences.

Making implicit classroom expectations explicit through collaborative agreement-setting creates transparency and mutual respect between teachers and students. When teachers acknowledge that their authority comes from student consent rather than position alone, it builds trust and legitimacy. This approach transforms the classroom dynamic from authoritarian control to democratic partnership whilst maintaining necessary structure for learning.

To examine deeper into Social Contract Theory and its implications, consider the following resources:

Hobbes, T. (1651). *Leviathan*. London: Andrew Crooke.

Locke, J. (1689). *Two Treatises of Government*. London: Awnsham Churchill.

Rousseau, J.J. (1762). *The Social Contract*. Paris: Michel Rey.

Rawls, J. (1971). *A Theory of Justice*. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Hampton, J. (1986). *Hobbes and the Social Contract Tradition*. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

These peer-reviewed studies provide the research foundation for the strategies discussed in this article:

Promoting Quality Language Learning Through Efficient Classroom Management: The Case of English Language Teaching in Bukavu Secondary Schools View study ↗

Heritier Ombeni Kalalizi et al. (2025)

This research examined how effective classroom management directly impacts English language learning quality in secondary schools in the Democratic Republic of Congo. The study found that poor classroom control strategies and outdated teaching methods were major barriers to student success in English as a Foreign Language. For teachers, this highlights the critical connection between strong classroom management skills and actual learning outcomes, especially in challenging educational environments.

Exploring the Connectivity Between Education 4.0 and Classroom 4.0: Technologies, Student Perspectives, and Engagement in the Digital Era View study ↗

20 citations

K. Joshi et al. (2024)

This study investigated how digital technologies are transforming modern classrooms and what students actually think about these changes. The research found both significant opportunities and challenges in integrating advanced digital tools into everyday teaching practise. For educators, this provides valuable insights into how to effectively balance traditional teaching with new technologies while ensuring equitable access and meaningful student engagement.

Social Contract Theory, a cornerstone in the edifice of , offers a window into the intricate relationship between individual people and societal structures. At its core, this theory posits that members of a society implicitly agree to surrender some freedoms to authority figures in exchange for protection of their remaining rights. This conceptual framework, championed by social contract theorists, explores into the origins of moral and political order, examining how collective agreements shape human life.

The theory's roots can be traced back to the Enlightenment era, where thinkers like John Locke and Jean-Jacques Rousseau pondered over the human condition in a 'state of nature', a hypothetical life without political institutions. They argued that rational individuals would agree to form a society governed by mutual obligations, moving away from the brutish, solitary life that characterises the state of nature. This transition, according to them, is guided by an inherent understanding of moral codes and the laws of nature.

In the 20th century, John Rawls revitalized the theory with his ' theory of justice', which reimagined the social contract as a fair agreement among equals. Rawls' perspective underscores the role of moral persons in shaping a just society, where political power is exercised in ways that are beneficial to all, especially the least advantaged. His ideas resonate profoundly in modern society, where equity and fairness in educational and political institutions are increasingly scrutinized.

Social Contract Theory offers a lens to view the evolution of societal norms and the balance between individual liberty and collective good. It remains a dominant theory in understanding the philosophical underpinnings of modern governance and social structures.

Key ideas to explore:

Hobbes, Locke, and Rousseau each developed distinct versions of social contract theory that differ fundamentally in their views of human nature, government legitimacy, and individual rights.

The history of social contract theory dates back to ancient Greece, with the contributions of Socrates. Socrates believed that individuals enter into a social contract voluntarily in order to establish a just and moral society. However, it was Thomas Hobbes who popularized the concept of social contract theory in the 17th century.

Hobbes argued that in a state of nature, without any governing authority, individuals would suffer a constant fear of violent death. To avoid this, they willingly enter into a social contract where they surrender certain freedoms to a sovereign ruler in exchange for protection and security.

This idea was further developed by John Locke in the 17th century. Locke emphasised the importance of individual rights and believed that the purpose of the social contract was to protect these rights. He argued that if a government failed to do so, individuals had the right to rebel and establish a new social contract.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau contributed to the theory in the 18th century with his idea of the "general will." He believed that in order for a society to be just, decisions should be made collectively, considering the common good rather than individual interests. This emphasis on collective decision-making connects to modern concepts of social-emotional learning in educational contexts.

Overall, social contract theory proposes that moral and political obligations are dependent on a contract or agreement among individuals to form a society. This theory has shaped modern political thought and continues to be relevant in discussions on governance and individual rights. In educational settings, these principles inform classroom management approaches that emphasise shared responsibility and student engagement in creating learning environments.

Social contract theory examines into the fundamental questions of political legitimacy, individual rights, and the moral foundations of society. Understanding this theory is crucial for educators, as its principles directly influence classroom management, student engagement, and the cultivation of democratic values.

Here are some key theorists:

Social Contract Theory provides a strong framework for educators to establish ethical and effective learning environments. By understanding the core principles of this theory, teachers can create classrooms that promote fairness, respect, and shared responsibility.

Here are some practical applications:

Effective pedagogical approaches include using current events to illustrate social contract principles in action. For instance, discussions about taxation, public services, or emergency powers during crises can help students understand how citizens consent to government authority in exchange for protection and services. Role-playing activities where students negotiate classroom rules or simulate constitutional conventions can make abstract concepts tangible and accessible to learners of different ages.

Educators should also encourage students to examine different cultural and historical contexts for social contracts. Comparing democratic systems with other forms of governance helps students appreciate the voluntary nature of democratic participation whilst developing analytical skills for evaluating political systems. Cross-curricular connections with history, literature, and contemporary studies can reinforce understanding of how social contract theory influences modern civic life.

Assessment strategies might include debates about competing visions of the social contract, analytical essays examining real-world applications, or collaborative projects exploring how different societies structure their political agreements. Such approaches ensure that students not only grasp theoretical concepts but can apply social contract theory to evaluate contemporary political developments and their own roles as democratic citizens.

Understanding social contract theory requires examining four pivotal thinkers whose ideas fundamentally shaped modern political philosophy. Thomas Hobbes argued that without government, human life would be "solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short," necessitating a powerful sovereign to maintain order. John Locke countered with a more optimistic view, proposing that individuals surrender some freedoms to protect their natural rights to life, liberty, and property. Jean-Jacques Rousseau famously declared that "man is born free, and everywhere he is in chains," advocating for a social contract that preserves individual freedom whilst creating collective will.

John Rawls transformed twentieth-century political theory with his "veil of ignorance" concept, where rational individuals design a just society without knowing their position within it. This thought experiment powerfully demonstrates how fairness emerges when self-interest is temporarily suspended. Each theorist's contribution offers educators distinct pedagogical opportunities: Hobbes illustrates the necessity of rules, Locke emphasises individual rights, Rousseau explores democratic participation, and Rawls provides a framework for discussing justice and equality.

In classroom practise, educators can engage students by presenting scenarios that mirror these philosophical positions. Asking students to design classroom rules using Rawls' approach, or debating Hobbes versus Locke regarding school governance, transforms abstract theory into concrete understanding of democratic citizenship and civic responsibility.

Social contract theory emerged during the 17th and 18th centuries as Enlightenment philosophers grappled with fundamental questions about political authority and individual rights. This intellectual movement arose partly as a response to the absolute monarchies that dominated Europe, where rulers claimed divine right to govern without consent from their subjects. Educators should emphasise to students that these theories weren't merely abstract philosophical exercises, but urgent attempts to understand and justify political power during periods of civil war, revolution, and social upheaval.

The historical context becomes particularly valuable when teaching students about the evolution of democratic thought. Thomas Hobbes wrote during the English Civil War, influencing his pessimistic view of human nature, whilst John Locke's theories emerged after the Glorious Revolution of 1688, reflecting more optimistic possibilities for constitutional government. Jean-Jacques Rousseau's contributions came during the intellectual ferment preceding the French Revolution, emphasising popular sovereignty and the general will.

In the classroom, educators can help students understand these theories by connecting them to specific historical crises and social transformations. Consider using timeline activities that juxtapose major political events with the publication of key texts, enabling students to see how political philosophy responds to real-world challenges. This approach demonstrates that democratic institutions and civic rights emerged through centuries of intellectual struggle and practical experimentation.

Effective instruction in social contract theory requires scaffolded learning approaches that move students from concrete examples to abstract philosophical concepts. Begin with familiar scenarios such as classroom rules or school policies, helping students recognise that these represent agreements between individuals for mutual benefit. Role-playing activities prove particularly valuable, where students negotiate hypothetical social contracts for desert island scenarios or new communities, experiencing firsthand the tensions between individual freedom and collective security that Hobbes, Locke, and Rousseau explored.

Comparative analysis exercises allow students to examine different philosophers' perspectives systematically. Create structured comparison charts where students evaluate how each theorist would approach contemporary issues such as digital privacy, environmental protection, or pandemic responses. Jerome Bruner's constructivist theory supports this approach, as students build understanding by connecting new philosophical concepts to current events and personal experiences.

Assessment strategies should emphasise critical thinking over rote memorisation. Design tasks requiring students to apply social contract principles to real-world situations, such as analysing school policies or local government decisions. Socratic seminars encourage deep discussion whilst developing civic engagement skills essential for democratic citizenship. These methods ensure that students not only understand theoretical concepts but can also articulate how social contract theory remains relevant to modern democratic society.

Social Contract Theory offers a compelling framework for understanding the relationship between individuals and society. From the ancient ideas of Socrates to the modern interpretations of John Rawls, this theory has shaped political thought and continues to influence contemporary debates on governance and individual rights.

For educators, Social Contract Theory provides invaluable insights into creating ethical and effective learning environments. By applying the principles of shared responsibility, mutual respect, and democratic participation, teachers can cultivate classrooms that helps students to become engaged, responsible, and critically thinking members of society. Embracing this theory allows educators to move beyond traditional authority-based approaches, developing a collaborative environment where every student feels valued and heard.

Four thinkers fundamentally shaped our understanding of social contracts, each offering distinct perspectives that directly inform modern classroom dynamics. Thomas Hobbes painted humanity as naturally selfish and violent, arguing that without strong authority, life would be 'solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short'. His vision translates to classrooms where strict rules prevent chaos; think of supply teachers walking into unfamiliar classes where established authority structures have temporarily dissolved.

John Locke offered a more optimistic view, proposing that people possess natural rights to life, liberty, and property. In Lockean classrooms, teachers act as facilitators rather than enforcers, establishing rules through discussion rather than decree. When Year 9 students collaboratively create their own behaviour contracts at term's start, they're embodying Locke's belief that legitimate authority stems from consent, not force.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau believed humans were naturally good but corrupted by society, advocating for education that preserves this innate goodness. His concept of the 'general will' manifests when entire classes vote on reward systems or collectively decide consequences for disruption. Modern restorative justice practices in schools, where students help determine fair outcomes for misbehaviour, echo Rousseau's vision of collective decision-making.

John Rawls brought social contract theory into contemporary times with his 'veil of ignorance' thought experiment. He asked: what rules would we choose if we didn't know our position in society? Teachers can apply this by having students design classroom policies whilst imagining they could be anyone in the room; the quiet student, the class clown, or someone with learning difficulties. This exercise reveals how fairness emerges when self-interest is removed from rule-making.

Teachers can facilitate collaborative rule-making sessions where students negotiate and agree upon classroom expectations together. This approach mirrors the consent principle by ensuring students have genuine input into the social contract that governs their learning environment. The resulting rules carry more weight because students helped create them rather than having them imposed from above.

Primary school children (ages 7-11) can grasp basic ideas about fairness and agreements through simplified discussions about classroom communities. Secondary students (ages 11-18) can engage with more complex concepts like individual rights versus collective responsibility. Even young children naturally understand the concept of 'fair trades' which forms the foundation of social contract thinking.

When behaviour issues arise, teachers can refer back to the collectively agreed classroom contract rather than relying solely on external authority. This approach helps students understand that rule-breaking affects the community they helped create, fostering accountability and reflection. It also provides a framework for discussing why certain behaviours undermine the social agreement everyone consented to follow.

Teachers can use mock parliamentary debates, classroom constitution-writing exercises, and role-playing scenarios about desert island survival to illustrate social contract principles. Group project negotiations and peer mediation sessions also demonstrate how individuals surrender some freedoms for collective benefits. These hands-on activities make abstract philosophical concepts tangible and relevant to students' daily experiences.

Making implicit classroom expectations explicit through collaborative agreement-setting creates transparency and mutual respect between teachers and students. When teachers acknowledge that their authority comes from student consent rather than position alone, it builds trust and legitimacy. This approach transforms the classroom dynamic from authoritarian control to democratic partnership whilst maintaining necessary structure for learning.

To examine deeper into Social Contract Theory and its implications, consider the following resources:

Hobbes, T. (1651). *Leviathan*. London: Andrew Crooke.

Locke, J. (1689). *Two Treatises of Government*. London: Awnsham Churchill.

Rousseau, J.J. (1762). *The Social Contract*. Paris: Michel Rey.

Rawls, J. (1971). *A Theory of Justice*. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Hampton, J. (1986). *Hobbes and the Social Contract Tradition*. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

These peer-reviewed studies provide the research foundation for the strategies discussed in this article:

Promoting Quality Language Learning Through Efficient Classroom Management: The Case of English Language Teaching in Bukavu Secondary Schools View study ↗

Heritier Ombeni Kalalizi et al. (2025)

This research examined how effective classroom management directly impacts English language learning quality in secondary schools in the Democratic Republic of Congo. The study found that poor classroom control strategies and outdated teaching methods were major barriers to student success in English as a Foreign Language. For teachers, this highlights the critical connection between strong classroom management skills and actual learning outcomes, especially in challenging educational environments.

Exploring the Connectivity Between Education 4.0 and Classroom 4.0: Technologies, Student Perspectives, and Engagement in the Digital Era View study ↗

20 citations

K. Joshi et al. (2024)

This study investigated how digital technologies are transforming modern classrooms and what students actually think about these changes. The research found both significant opportunities and challenges in integrating advanced digital tools into everyday teaching practise. For educators, this provides valuable insights into how to effectively balance traditional teaching with new technologies while ensuring equitable access and meaningful student engagement.

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/social-contract-theory#article","headline":"Social Contract Theory","description":"Discover how social contract theory transforms classroom management through collaborative rule-making, student buy-in, and democratic principles that work.","datePublished":"2023-11-20T12:39:04.429Z","dateModified":"2026-02-12T12:05:03.380Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/social-contract-theory"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/69513ba4c4cf323b4c2a6691_h4rzjc.webp","wordCount":2877},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/social-contract-theory#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"Social Contract Theory","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/social-contract-theory"}]}]}