Implementing a Knowledge-Rich Curriculum

Knowledge-rich curriculum design builds schema and closes equity gaps. Learn how to implement evidence-based strategies using cognitive science in 2025 and beyond.

Knowledge-rich curriculum design builds schema and closes equity gaps. Learn how to implement evidence-based strategies using cognitive science in 2025 and beyond.

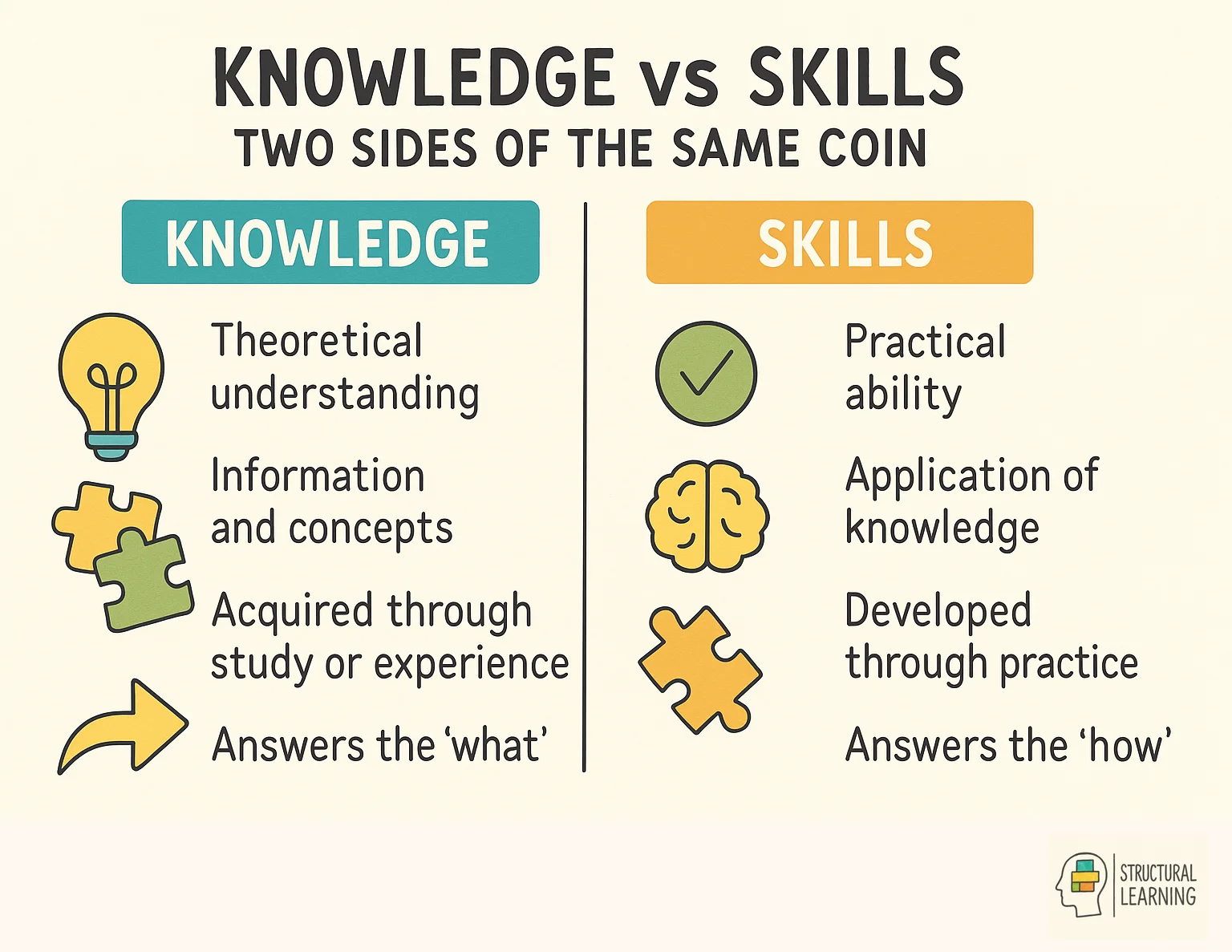

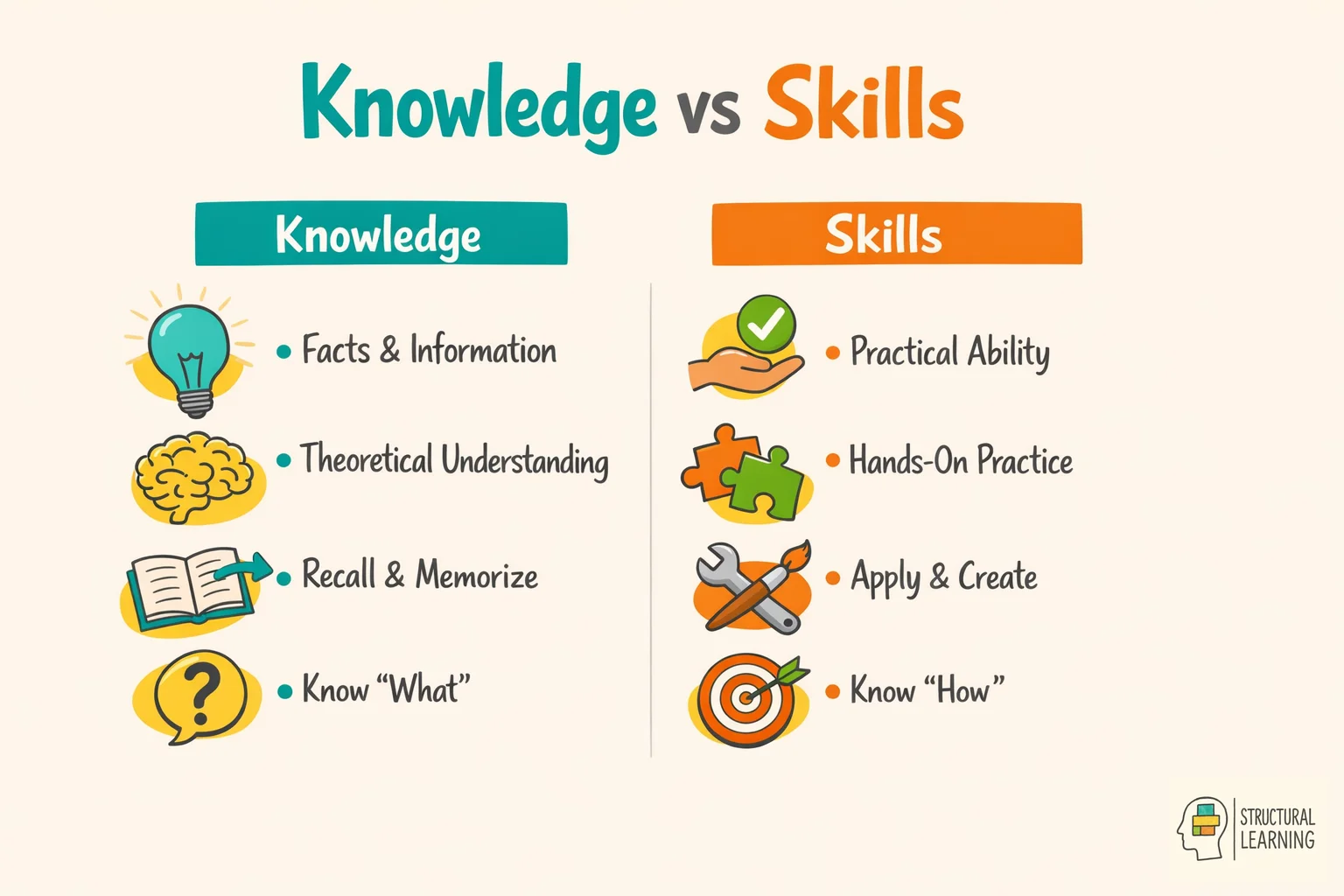

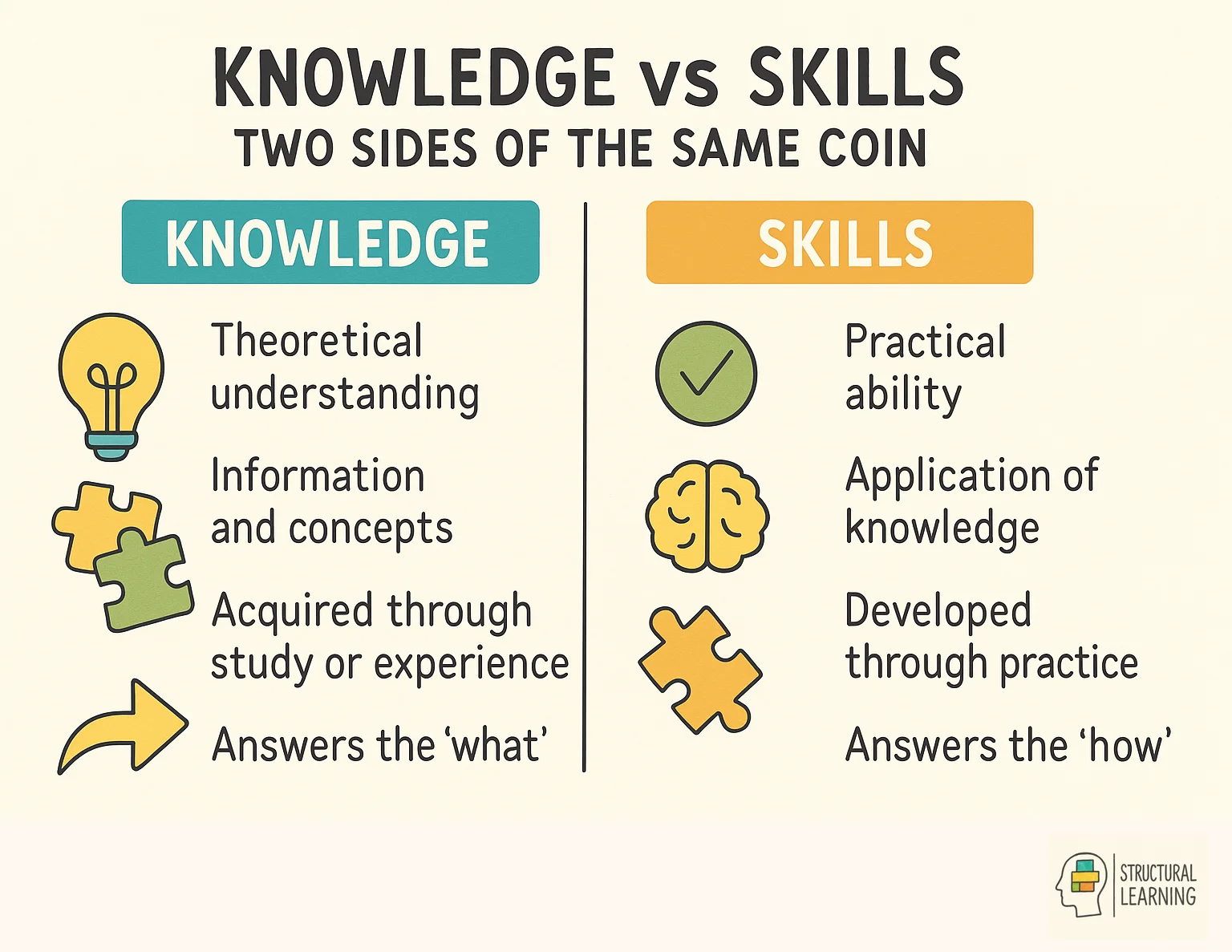

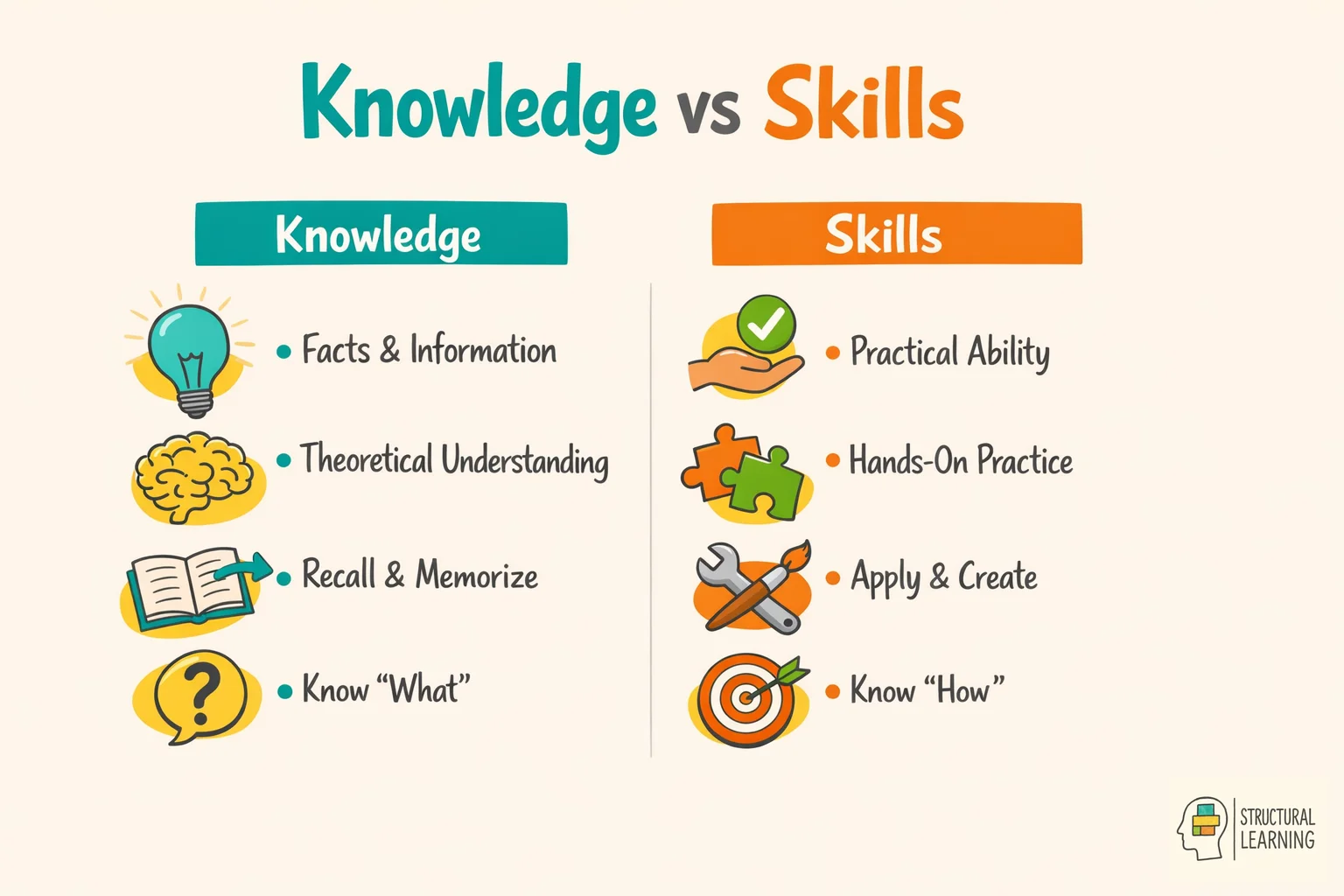

The outdated knowledge versus skills debate has become obsolete in 2025. We now understand that skills build knowledge and knowledge enables skills. They're two sides of the same coin, interdependent and inseparable. A student can't think critically without something to think critically about. You can't problem-solve in a vacuum.

This shift matters. Since the rise of the knowledge-rich curriculum movement under figures like Nick Gibb and Michael Young, we've seen political changes that raise new questions. Where does curriculum thinking stand now? What relevance does a knowledge-rich approach hold in an era of that can retrieve facts instantly?

The answer is straightforward. AI makes powerful knowledge more important, not less. Students need structured schemas to evaluate AI outputs, identify inaccuracies, and apply information meaningfully. limitations haven't changed. The need for coherent mental models hasn't disappeared. In fact, automation increases the premium on genuine understanding.

The intensity has shifted. Five years ago, knowledge-rich curriculum dominated every staffroom conversation. You couldn't escape it. Then came ChatGPT, Claude, and dozens of AI models. Some wondered if curriculum content still mattered when machines could answer any factual question. But here's what teachers discovered: AI tools work best for students who already possess deep . Without foundational understanding, students can't evaluate whether an AI response makes sense.

A knowledge-rich curriculum specifies the content children should learn across year groups. It's a deliberate response to curricula focused solely on generic skills. The approach recognises that skills like analysis or evaluation can't develop independently from domain-specific knowledge. You can't analyse the causes of a war without first knowing the key facts, figures, and context.

This makes teachers curriculum architects. We must intentionally design a coherent learning journey that builds logically over years. It's not just about "doing the Romans." It's about specifying the essential knowledge, the vocabulary, concepts, and stories, that all students must master and remember.

Michael Young described this as powerful knowledge. Not random facts, but conceptual understanding that gives learners new ways to think about the world. This knowledge is often abstract, theoretical, and developed by subject specialists. It takes students beyond their immediate experiences into academic disciplines they might not otherwise access.

The curriculum itself becomes the primary driver of achievement, not a student's home background. This distinction matters for . Children in the highest socioeconomic group entering kindergarten have cognitive scores 60% higher than peers in the lowest group. A specified, shared curriculum aims to close this gap.

Here's where cognitive science becomes crucial. We move beyond creating fun, one-off "memorable experiences" that rely on episodic memory and quickly fade. Instead, we focus on building durable, flexible long-term knowledge, semantic memory, using proven strategies like low-stakes quizzing and .

The goal isn't turning students into pub quiz champions. It's about empowering every child with the powerful knowledge they're entitled to. This enables them to participate in the great conversations of our culture and develop the wisdom and compassion to shape their world for the better.

Learning is cumulative. New information connects to existing knowledge. Students with broad background knowledge process new information more effectively, freeing for higher-order thinking. Without this foundation, cognitive overload becomes a barrier.

The goal is building coherent schemas in long-term memory. Research from cognitive science shows that forgetting curves are steep. Without reinforcement, learners forget 70% of new information within 24 hours. This isn't a flaw in student effort. It's how memory works.

combats this. Regularly pulling information from memory strengthens the memory trace. revisits content at increasing intervals. mixes different topics within practice sessions. These strategies build durable memories that last.

From an equity perspective, curriculum specification is the most powerful intervention available. Students can't learn what isn't taught. By defining exactly what knowledge schools will teach, we create opportunities for all students regardless of home resources.

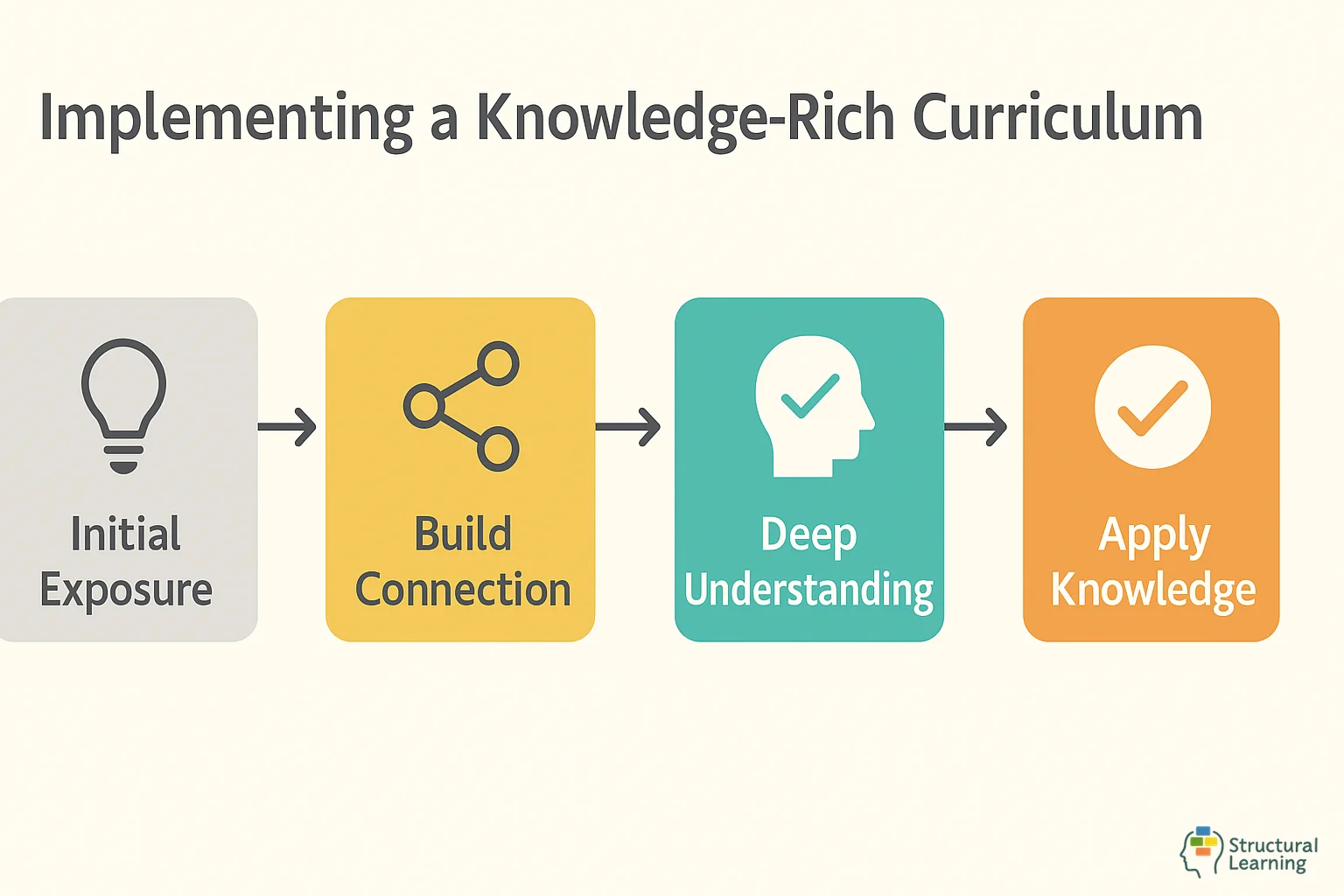

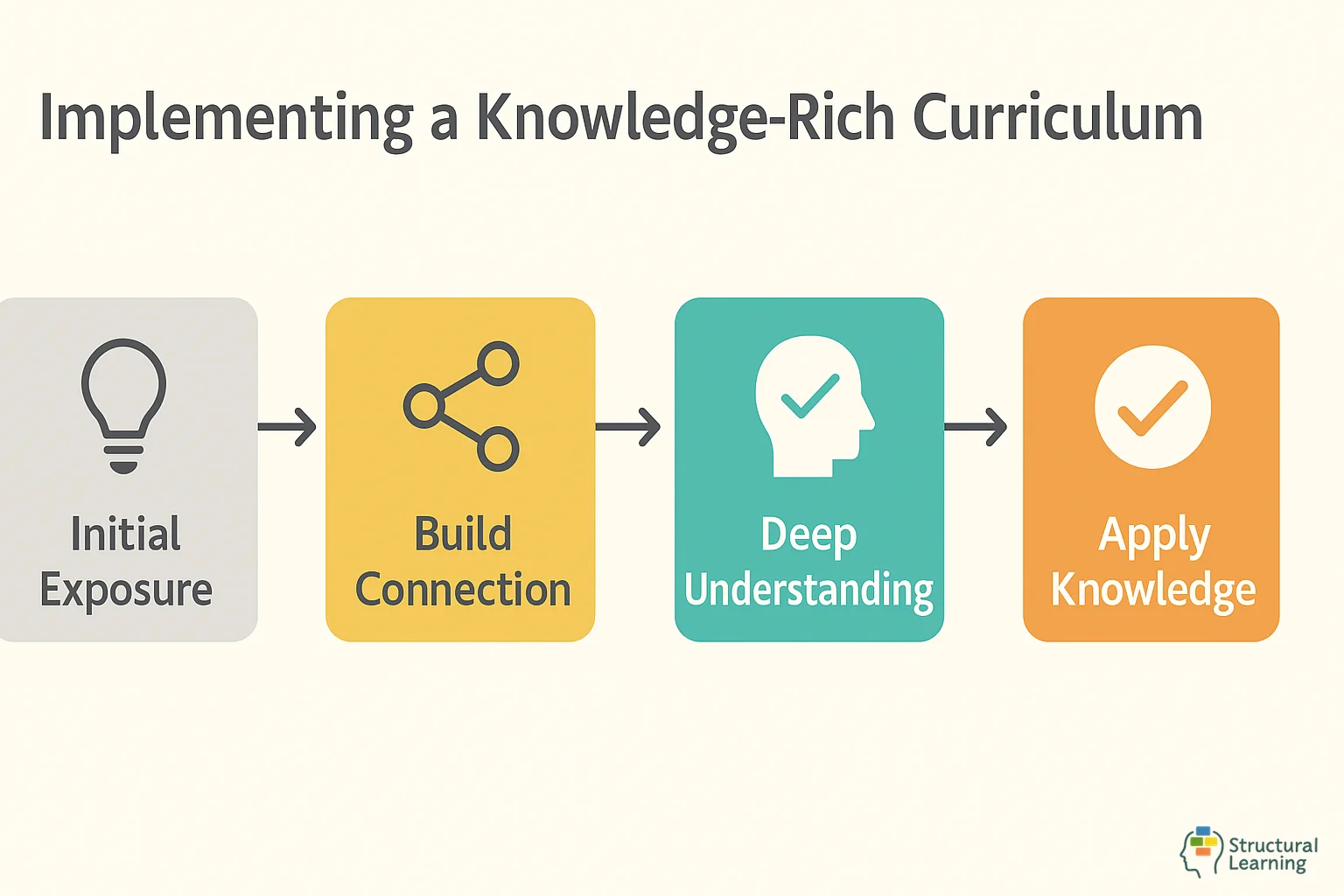

Senior leadership teams need a systematic approach. Here's a practical roadmap:

Start with the end in mind. What should students know and be able to do when they leave your school? Map the pinnacle concepts, principles, and debates that define each subject. Don't stop at National Curriculum topic headings. Specify the granular knowledge required.

Instead of "The Romans," define key concepts like republic and empire, the significance of the Punic Wars, and reasons for Western Roman Empire decline. This detail ensures every teacher understands the non-negotiable content.

Arrange knowledge so each piece builds on what came before. Curriculum design isn't a disconnected list of facts. It's a narrative where prior learning prepares students for what comes next.

Consider both chronological and conceptual logic. History often follows chronological order. Science might teach cells before tissues and organs. Plan vertically across year groups and horizontally across subjects within each year. The aim is a compelling story of learning that makes knowledge easier to retain and apply.

Knowledge organisers are single-page documents summarising essential content for a unit. Include key vocabulary, important dates, core concepts, diagrams, and crucial facts.

These tools serve multiple purposes. For teachers, they ensure clarity and consistency. For students, they provide a clear overview supporting independent study. For parents, they offer a window into their child's learning. Remember, they're not the curriculum itself but a tool supporting it.

Brilliant curriculum documents fail if content doesn't reach long-term memory. Build retrieval practice into every lesson. Low-stakes quizzing should become routine. Space out practice sessions. Mix topics within practice.

Use formative assessment constantly. Check for understanding, identify misconceptions, and adjust teaching accordingly. Techniques like questioning, mini-whiteboards, and exit tickets gauge how well students connect new knowledge to developing schemas.

The most crucial element is deepening teacher expertise. Schools must provide time for teachers to read, research, and collaborate with subject peers. Professional learning should also focus on cognitive science principles. Teachers need to understand why strategies like retrieval practice work.

Leaders champion the curriculum as core business. Protect time for collaborative planning and subject-specific training. Invest in high-quality textbooks, digital resources, and professional development. This sends a clear message that deep knowledge is valued.

Summative assessment must go beyond factual recall. Design assessments testing understanding of powerful knowledge at the curriculum's heart. Ask students to write extended responses synthesising knowledge across topics, analyse primary sources using background knowledge, or solve complex problems by applying learned principles.

The assessment should reveal schema depth and coherence, not just isolated fact memorisation. A 2023 study found students in schools using knowledge-rich sequences scored 16 percentile points higher on state tests than peers. The evidence suggests this approach works.

Note: The 16 percentile point finding comes from a University of Virginia study (2023) conducted in 9 Colorado charter schools. While promising, the study cannot fully distinguish curriculum effects from other charter school factors. UK-based evidence from the EEF's English Mastery evaluation provides additional context for knowledge-rich approaches in British schools.

The Thinking Framework acts as an insurance policy. It ensures children actually develop knowledge by thinking it through at deeper levels. The 30+ thinking skill cards grouped in five coloured categories give teachers a cognitive menu for planning, questioning, and assessment.

When students Extract, Categorise, Explain, use Target Vocabulary, or Connect ideas, they're processing knowledge beyond surface level. This deeper processing builds stronger schemas.

Graphic organisers help children generate their own ideas, leading to deeper knowledge. Templates like Fishbone, Cycle, Flow-chart, and Diamond 9 provide visual structures for thinking. They're not just note-making tools. They're thinking maps that scaffold how students organise information.

Writer's Block supports understanding of concepts within the knowledge. The interlocking blocks with whiteboard inserts allow physical sentence-building and idea-mapping. Students manipulate concepts, rearrange relationships, and build understanding through hands-on learning.

This isn't one or the other. Skills build the knowledge. The tools work together to ensure curriculum content moves from teacher explanation into student understanding and finally into durable long-term memory.

The principles of knowledge-rich curriculum apply from the earliest stages of education. In early years settings, powerful knowledge looks different from Key Stage 2, but it's equally important. Young children need systematic introduction to vocabulary, concepts, and cultural knowledge that forms the foundation for later learning.

Early years practitioners should specify the knowledge children will encounter. This includes core vocabulary around emotions, quantities, colours, and shapes. It includes stories, rhymes, and songs that build cultural capital. It includes basic scientific concepts like floating, sinking, and growing.

The sequencing matters here too. Continuous provision should build cumulatively. Each week's activities connect to previous learning while introducing new concepts. Knowledge organisers work in early years when adapted to visual formats with fewer words and more images.

Retrieval practice in early years looks like regular revisiting of songs, stories, and rhymes. It's asking children to recall what they learned yesterday. It's using the same vocabulary consistently across different contexts. Spacing and interleaving happen naturally through well-planned provision that cycles through themes at increasing complexity.

Metacognition begins early. Even young children can learn to articulate what they know and what they're learning. Simple self-assessment tools, thinking about thinking during activities, and explicit vocabulary teaching all contribute to early metacognitive development.

The equity argument is perhaps most powerful here. The vocabulary gap between children from different backgrounds is already significant at age three. A knowledge-rich approach to early years systematically addresses this gap by ensuring all children encounter the same rich language and concepts, regardless of home background.

The forgetting curve presents a challenge. Students forget most new information quickly without strategic reinforcement. This isn't laziness. It's neuroscience.

remains the most powerful tool. Quiz students regularly on previously learned material in low-stakes contexts. The act of pulling information from memory strengthens the memory trace. Make it easier to recall in future.

revisits content at increasing intervals. Don't teach a topic once and move on. Return to it a week later, then a month later, then a term later. Each revisit strengthens the memory.

mixes different topics within practice sessions. Don't mass practice on one topic. Mix topics so students must discriminate between different types of problems and concepts. This builds more flexible, transferable knowledge.

A common misconception suggests knowledge-rich curricula stifle independent thought. The opposite is true. Knowledge is the raw material for metacognition. When students possess secure knowledge, they have mental architecture necessary to think about their own learning.

Teachers foster this by explicitly teaching how memory works. Show students strategies like retrieval practice for effective study. Knowledge organisers become tools for self-quizzing. By giving students a clear map of what they need to know, we empower them to take ownership of learning, identify gaps in understanding, and become more effective independent learners.

Metacognitive strategies include planning before tasks, monitoring understanding during tasks, and evaluating after tasks. These strategies work better when students have subject knowledge to plan with, monitor, and evaluate.

In a knowledge-rich classroom, the teacher acts as expert, guiding students through complex new material. Explicit instruction, where the teacher clearly explains concepts, models processes, and provides guided practice, is the most efficient way to transmit new knowledge and build foundational understanding.

This approach places high value on teacher subject expertise. A teacher with deep knowledge of their discipline can craft compelling narratives, make insightful connections between concepts, and anticipate common misconceptions. They move beyond surface level to bring content to life, inspiring curiosity and fostering genuine love of the subject.

Rosenshine's Principles of Instruction align perfectly with knowledge-rich teaching. Review previous learning daily. Present new material in small steps. Ask questions and check for understanding. Provide models and worked examples. Guide practice extensively before independent work.

The false dichotomy between knowledge and skills has wasted countless hours of professional development time. Critical thinking is not a generic, transferable skill. One thinks critically with something. A student with deep historical knowledge analyses sources more critically than one without.

The curriculum's goal is cultivating disciplinary thinking. This is the fusion of powerful knowledge and subject-specific skills. A historian thinks differently from a scientist. A mathematician approaches problems differently from a poet. These are learned ways of thinking that develop through sustained engagement with disciplinary knowledge.

Skills also build knowledge. When students use graphic organisers to categorise information, they're using a skill that deepens their knowledge. When they practice retrieval, they're using a skill that strengthens knowledge. When they engage in structured classroom dialogue, they're using oracy skills that clarify and extend their understanding.

Critics worry that knowledge-rich curricula promote mere rote learning. This misunderstands the approach entirely. The ultimate goal is deep, flexible understanding. Factual recall is the necessary starting point, not the final destination.

The emphasis on sequencing, schema building, and narrative ensures knowledge is connected and meaningful. Pedagogical and assessment strategies should always push students beyond recall toward application, analysis, and synthesis.

Deliberate practice moves students from novice to expert understanding. This requires focused, effortful practice with immediate AI-enhanced feedback. It's not mindless repetition. It's thoughtful engagement with increasingly complex applications of knowledge.

A knowledge-rich curriculum is inclusive when designed correctly. The core principle is that all students are entitled to the same ambitious body of knowledge. AI-powered differentiation shouldn't reduce curriculum scope for some students.

Instead, achieve differentiation through expert scaffolding and support. This might involve pre-teaching vocabulary, providing graphic organisers to structure thinking, or breaking complex ideas into smaller steps. The ambition remains high for all students. The support to get there is tailored.

Students with SEND often struggle most when curriculum content is vague or generic. Clear specification of knowledge, explicit teaching, and structured support give these students the best chance of success. High expectations combined with strong scaffolding is the most equitable approach.

For a knowledge-rich approach to be sustainable, new teachers must enter the profession with firm grounding in curriculum theory and cognitive science. Initial Teacher Training (ITT) programmes should emphasise subject knowledge development alongside pedagogical skills.

In 2023-24, there were 22,760 postgraduate trainees with outcomes, down from the previous year. With fluctuating trainee numbers, it's vital that training is effective. Once in school, a robust induction programme coupled with ongoing mentoring from experienced subject experts helps early career teachers translate theoretical understanding into confident classroom practice.

Instructional coaching supports ongoing development. Regular observation, feedback, and collaborative planning help teachers refine their practice. The focus should be on deepening subject knowledge and improving the effectiveness of explicit instruction.

Implementing a knowledge-rich curriculum is demanding but profoundly rewarding. For students, it provides intellectual capital to understand the world, engage in complex conversations, and achieve academic success. It closes equity gaps and opens doors to future opportunities.

For educators, it's a deeply professionalising act. It re-centres the profession on subject passion and pedagogical expertise, fostering collaborative culture focused on education's core purpose: building knowledge.

This isn't about reaching a final, perfect curriculum. It's a commitment to continuous cycles of design, implementation, and refinement. It's a dynamic process of school reform, driven by a clear vision of what constitutes truly empowering education.

By placing powerful knowledge at the heart of their work, schools can build a lasting foundation for learning. This equips every student with understanding and confidence to thrive. In 2025 and beyond, as AI reshapes how we access information, the case for a knowledge-rich curriculum becomes stronger. Students need robust mental models, not just facts. They need deep understanding, not surface memorisation. They need powerful knowledge that transforms how they see and interact with the world.

Q: How is a knowledge-rich curriculum different from traditional teaching? A: It specifies exactly what knowledge students should learn, sequences it deliberately for schema building, and uses cognitive science strategies like retrieval practice to ensure knowledge reaches long-term memory. It's more intentional and evidence-based than ad hoc topic teaching.

Q: Won't this stifle creativity and critical thinking? A: No. Knowledge is the foundation for creativity and critical thinking. You can't think critically without something to think critically about. Students with deep knowledge can apply it creatively and evaluate ideas more effectively than those with surface understanding.

Q: How do I ensure my knowledge-rich curriculum is inclusive? A: Set the same ambitious knowledge expectations for all students. Differentiate through scaffolding and support, not by reducing content. Pre-teach vocabulary, use graphic organisers, and break complex ideas into steps while maintaining high expectations.

These five papers offer key critiques of the Knowledge-Rich curriculum and the Powerful Knowledge framework, challenging their assumptions, applications, and sociopolitical implications in curriculum design. Together, they provide essential insights for educators and subject leaders rethinking curriculum making, subject-specific knowledge, and equitable access to learning.

1. Knowledge and racial violence: the shine and shadow of ‘powerful knowledge’

Sophie Rudolph, A. Sriprakash & J. Gerrard (2018)

Challenges the epistemic neutrality of powerful knowledge by exposing its colonial roots, urging curriculum design to integrate racial justice within subject-specific curriculum frameworks.

2. ‘Powerful knowledge’, ‘cultural literacy’ and the study of literature in schools

Robert Eaglestone (2020)

Argues that applying scientific models of knowledge to English disfigures curriculum making, neglecting domain-specific knowledge and damaging subject disciplines like literature.

3. Powerful knowledge, educational potential and knowledge-rich curriculum: pushing the boundaries

Zongyi Deng (2022)

Repositions knowledge-rich curriculum toward human flourishing, critiquing rigid curriculum frameworks that ignore curriculum design's role in shaping domain-specific capabilities and subject leaders' agency.

4. Un-Standardizing Curriculum: Multicultural Teaching in the Standards-based Classroom

Christine Sleeter (2016)

Opposes standardised knowledge content, advocating curriculum design that balances academic rigour with subject-specific curriculum responsive to cultural and cognitive achievement gaps.

5. Debate and critique in curriculum studies: new directions?

Mark Priestley & S. Philippou (2019)

Reviews critiques of powerful knowledge and curriculum frameworks, calling for broader subject leader engagement and curriculum making that values educational practice and knowledge content.

A knowledge-rich curriculum specifies the essential content children should learn across year groups, recognising that skills like analysis or evaluation cannot develop independently from domain-specific knowledge. Rather than focusing on generic skills alone, it provides students with 'powerful knowledge' - conceptual understanding that gives learners new ways to think about the world beyond their immediate experiences.

Begin by identifying your core knowledge - map the pinnacle concepts, principles, and debates that define each subject, going beyond National Curriculum topic headings to specify granular knowledge requirements. Then sequence this knowledge so each piece builds on what came before, creating a coherent learning journey that develops logical schemas in students' long-term memory.

Knowledge organisers are single-page documents that summarise essential content for a unit, including key vocabulary, important dates, core concepts, diagrams, and crucial facts. They serve as tools to ensure teacher clarity and consistency, support student independent study, and provide parents with insight into their child's learning, though they are not the curriculum itself.

Research shows that learners forget 70% of new information within 24 hours without reinforcement, and students with broad background knowledge process new information more effectively, freeing up cognitive capacity for higher-order thinking. Strategies like retrieval practice, spaced repetition, and interleaving help combat forgetting curves and build durable, flexible long-term knowledge in semantic memory.

By specifying exactly what knowledge schools will teach, a knowledge-rich curriculum ensures all students have access to powerful knowledge regardless of their home background or resources. This approach recognises that children from higher socioeconomic groups enter school with cognitive scores 60% higher than peers from lower groups, making curriculum specification the most powerful equity intervention available.

AI actually makes powerful knowledge more important, not less, as students need structured schemas to evaluate AI outputs, identify inaccuracies, and apply information meaningfully. Without foundational understanding and deep subject knowledge, students cannot effectively evaluate whether an AI response makes sense or use AI tools productively for learning.

Schools must provide dedicated time for teachers to read, research, and collaborate with subject peers, treating curriculum development as core business. Professional learning should focus on both deepening subject expertise and understanding cognitive science principles, so teachers understand why strategies like retrieval practice and spaced repetition are effective for building long-term retention.

The outdated knowledge versus skills debate has become obsolete in 2025. We now understand that skills build knowledge and knowledge enables skills. They're two sides of the same coin, interdependent and inseparable. A student can't think critically without something to think critically about. You can't problem-solve in a vacuum.

This shift matters. Since the rise of the knowledge-rich curriculum movement under figures like Nick Gibb and Michael Young, we've seen political changes that raise new questions. Where does curriculum thinking stand now? What relevance does a knowledge-rich approach hold in an era of that can retrieve facts instantly?

The answer is straightforward. AI makes powerful knowledge more important, not less. Students need structured schemas to evaluate AI outputs, identify inaccuracies, and apply information meaningfully. limitations haven't changed. The need for coherent mental models hasn't disappeared. In fact, automation increases the premium on genuine understanding.

The intensity has shifted. Five years ago, knowledge-rich curriculum dominated every staffroom conversation. You couldn't escape it. Then came ChatGPT, Claude, and dozens of AI models. Some wondered if curriculum content still mattered when machines could answer any factual question. But here's what teachers discovered: AI tools work best for students who already possess deep . Without foundational understanding, students can't evaluate whether an AI response makes sense.

A knowledge-rich curriculum specifies the content children should learn across year groups. It's a deliberate response to curricula focused solely on generic skills. The approach recognises that skills like analysis or evaluation can't develop independently from domain-specific knowledge. You can't analyse the causes of a war without first knowing the key facts, figures, and context.

This makes teachers curriculum architects. We must intentionally design a coherent learning journey that builds logically over years. It's not just about "doing the Romans." It's about specifying the essential knowledge, the vocabulary, concepts, and stories, that all students must master and remember.

Michael Young described this as powerful knowledge. Not random facts, but conceptual understanding that gives learners new ways to think about the world. This knowledge is often abstract, theoretical, and developed by subject specialists. It takes students beyond their immediate experiences into academic disciplines they might not otherwise access.

The curriculum itself becomes the primary driver of achievement, not a student's home background. This distinction matters for . Children in the highest socioeconomic group entering kindergarten have cognitive scores 60% higher than peers in the lowest group. A specified, shared curriculum aims to close this gap.

Here's where cognitive science becomes crucial. We move beyond creating fun, one-off "memorable experiences" that rely on episodic memory and quickly fade. Instead, we focus on building durable, flexible long-term knowledge, semantic memory, using proven strategies like low-stakes quizzing and .

The goal isn't turning students into pub quiz champions. It's about empowering every child with the powerful knowledge they're entitled to. This enables them to participate in the great conversations of our culture and develop the wisdom and compassion to shape their world for the better.

Learning is cumulative. New information connects to existing knowledge. Students with broad background knowledge process new information more effectively, freeing for higher-order thinking. Without this foundation, cognitive overload becomes a barrier.

The goal is building coherent schemas in long-term memory. Research from cognitive science shows that forgetting curves are steep. Without reinforcement, learners forget 70% of new information within 24 hours. This isn't a flaw in student effort. It's how memory works.

combats this. Regularly pulling information from memory strengthens the memory trace. revisits content at increasing intervals. mixes different topics within practice sessions. These strategies build durable memories that last.

From an equity perspective, curriculum specification is the most powerful intervention available. Students can't learn what isn't taught. By defining exactly what knowledge schools will teach, we create opportunities for all students regardless of home resources.

Senior leadership teams need a systematic approach. Here's a practical roadmap:

Start with the end in mind. What should students know and be able to do when they leave your school? Map the pinnacle concepts, principles, and debates that define each subject. Don't stop at National Curriculum topic headings. Specify the granular knowledge required.

Instead of "The Romans," define key concepts like republic and empire, the significance of the Punic Wars, and reasons for Western Roman Empire decline. This detail ensures every teacher understands the non-negotiable content.

Arrange knowledge so each piece builds on what came before. Curriculum design isn't a disconnected list of facts. It's a narrative where prior learning prepares students for what comes next.

Consider both chronological and conceptual logic. History often follows chronological order. Science might teach cells before tissues and organs. Plan vertically across year groups and horizontally across subjects within each year. The aim is a compelling story of learning that makes knowledge easier to retain and apply.

Knowledge organisers are single-page documents summarising essential content for a unit. Include key vocabulary, important dates, core concepts, diagrams, and crucial facts.

These tools serve multiple purposes. For teachers, they ensure clarity and consistency. For students, they provide a clear overview supporting independent study. For parents, they offer a window into their child's learning. Remember, they're not the curriculum itself but a tool supporting it.

Brilliant curriculum documents fail if content doesn't reach long-term memory. Build retrieval practice into every lesson. Low-stakes quizzing should become routine. Space out practice sessions. Mix topics within practice.

Use formative assessment constantly. Check for understanding, identify misconceptions, and adjust teaching accordingly. Techniques like questioning, mini-whiteboards, and exit tickets gauge how well students connect new knowledge to developing schemas.

The most crucial element is deepening teacher expertise. Schools must provide time for teachers to read, research, and collaborate with subject peers. Professional learning should also focus on cognitive science principles. Teachers need to understand why strategies like retrieval practice work.

Leaders champion the curriculum as core business. Protect time for collaborative planning and subject-specific training. Invest in high-quality textbooks, digital resources, and professional development. This sends a clear message that deep knowledge is valued.

Summative assessment must go beyond factual recall. Design assessments testing understanding of powerful knowledge at the curriculum's heart. Ask students to write extended responses synthesising knowledge across topics, analyse primary sources using background knowledge, or solve complex problems by applying learned principles.

The assessment should reveal schema depth and coherence, not just isolated fact memorisation. A 2023 study found students in schools using knowledge-rich sequences scored 16 percentile points higher on state tests than peers. The evidence suggests this approach works.

Note: The 16 percentile point finding comes from a University of Virginia study (2023) conducted in 9 Colorado charter schools. While promising, the study cannot fully distinguish curriculum effects from other charter school factors. UK-based evidence from the EEF's English Mastery evaluation provides additional context for knowledge-rich approaches in British schools.

The Thinking Framework acts as an insurance policy. It ensures children actually develop knowledge by thinking it through at deeper levels. The 30+ thinking skill cards grouped in five coloured categories give teachers a cognitive menu for planning, questioning, and assessment.

When students Extract, Categorise, Explain, use Target Vocabulary, or Connect ideas, they're processing knowledge beyond surface level. This deeper processing builds stronger schemas.

Graphic organisers help children generate their own ideas, leading to deeper knowledge. Templates like Fishbone, Cycle, Flow-chart, and Diamond 9 provide visual structures for thinking. They're not just note-making tools. They're thinking maps that scaffold how students organise information.

Writer's Block supports understanding of concepts within the knowledge. The interlocking blocks with whiteboard inserts allow physical sentence-building and idea-mapping. Students manipulate concepts, rearrange relationships, and build understanding through hands-on learning.

This isn't one or the other. Skills build the knowledge. The tools work together to ensure curriculum content moves from teacher explanation into student understanding and finally into durable long-term memory.

The principles of knowledge-rich curriculum apply from the earliest stages of education. In early years settings, powerful knowledge looks different from Key Stage 2, but it's equally important. Young children need systematic introduction to vocabulary, concepts, and cultural knowledge that forms the foundation for later learning.

Early years practitioners should specify the knowledge children will encounter. This includes core vocabulary around emotions, quantities, colours, and shapes. It includes stories, rhymes, and songs that build cultural capital. It includes basic scientific concepts like floating, sinking, and growing.

The sequencing matters here too. Continuous provision should build cumulatively. Each week's activities connect to previous learning while introducing new concepts. Knowledge organisers work in early years when adapted to visual formats with fewer words and more images.

Retrieval practice in early years looks like regular revisiting of songs, stories, and rhymes. It's asking children to recall what they learned yesterday. It's using the same vocabulary consistently across different contexts. Spacing and interleaving happen naturally through well-planned provision that cycles through themes at increasing complexity.

Metacognition begins early. Even young children can learn to articulate what they know and what they're learning. Simple self-assessment tools, thinking about thinking during activities, and explicit vocabulary teaching all contribute to early metacognitive development.

The equity argument is perhaps most powerful here. The vocabulary gap between children from different backgrounds is already significant at age three. A knowledge-rich approach to early years systematically addresses this gap by ensuring all children encounter the same rich language and concepts, regardless of home background.

The forgetting curve presents a challenge. Students forget most new information quickly without strategic reinforcement. This isn't laziness. It's neuroscience.

remains the most powerful tool. Quiz students regularly on previously learned material in low-stakes contexts. The act of pulling information from memory strengthens the memory trace. Make it easier to recall in future.

revisits content at increasing intervals. Don't teach a topic once and move on. Return to it a week later, then a month later, then a term later. Each revisit strengthens the memory.

mixes different topics within practice sessions. Don't mass practice on one topic. Mix topics so students must discriminate between different types of problems and concepts. This builds more flexible, transferable knowledge.

A common misconception suggests knowledge-rich curricula stifle independent thought. The opposite is true. Knowledge is the raw material for metacognition. When students possess secure knowledge, they have mental architecture necessary to think about their own learning.

Teachers foster this by explicitly teaching how memory works. Show students strategies like retrieval practice for effective study. Knowledge organisers become tools for self-quizzing. By giving students a clear map of what they need to know, we empower them to take ownership of learning, identify gaps in understanding, and become more effective independent learners.

Metacognitive strategies include planning before tasks, monitoring understanding during tasks, and evaluating after tasks. These strategies work better when students have subject knowledge to plan with, monitor, and evaluate.

In a knowledge-rich classroom, the teacher acts as expert, guiding students through complex new material. Explicit instruction, where the teacher clearly explains concepts, models processes, and provides guided practice, is the most efficient way to transmit new knowledge and build foundational understanding.

This approach places high value on teacher subject expertise. A teacher with deep knowledge of their discipline can craft compelling narratives, make insightful connections between concepts, and anticipate common misconceptions. They move beyond surface level to bring content to life, inspiring curiosity and fostering genuine love of the subject.

Rosenshine's Principles of Instruction align perfectly with knowledge-rich teaching. Review previous learning daily. Present new material in small steps. Ask questions and check for understanding. Provide models and worked examples. Guide practice extensively before independent work.

The false dichotomy between knowledge and skills has wasted countless hours of professional development time. Critical thinking is not a generic, transferable skill. One thinks critically with something. A student with deep historical knowledge analyses sources more critically than one without.

The curriculum's goal is cultivating disciplinary thinking. This is the fusion of powerful knowledge and subject-specific skills. A historian thinks differently from a scientist. A mathematician approaches problems differently from a poet. These are learned ways of thinking that develop through sustained engagement with disciplinary knowledge.

Skills also build knowledge. When students use graphic organisers to categorise information, they're using a skill that deepens their knowledge. When they practice retrieval, they're using a skill that strengthens knowledge. When they engage in structured classroom dialogue, they're using oracy skills that clarify and extend their understanding.

Critics worry that knowledge-rich curricula promote mere rote learning. This misunderstands the approach entirely. The ultimate goal is deep, flexible understanding. Factual recall is the necessary starting point, not the final destination.

The emphasis on sequencing, schema building, and narrative ensures knowledge is connected and meaningful. Pedagogical and assessment strategies should always push students beyond recall toward application, analysis, and synthesis.

Deliberate practice moves students from novice to expert understanding. This requires focused, effortful practice with immediate AI-enhanced feedback. It's not mindless repetition. It's thoughtful engagement with increasingly complex applications of knowledge.

A knowledge-rich curriculum is inclusive when designed correctly. The core principle is that all students are entitled to the same ambitious body of knowledge. AI-powered differentiation shouldn't reduce curriculum scope for some students.

Instead, achieve differentiation through expert scaffolding and support. This might involve pre-teaching vocabulary, providing graphic organisers to structure thinking, or breaking complex ideas into smaller steps. The ambition remains high for all students. The support to get there is tailored.

Students with SEND often struggle most when curriculum content is vague or generic. Clear specification of knowledge, explicit teaching, and structured support give these students the best chance of success. High expectations combined with strong scaffolding is the most equitable approach.

For a knowledge-rich approach to be sustainable, new teachers must enter the profession with firm grounding in curriculum theory and cognitive science. Initial Teacher Training (ITT) programmes should emphasise subject knowledge development alongside pedagogical skills.

In 2023-24, there were 22,760 postgraduate trainees with outcomes, down from the previous year. With fluctuating trainee numbers, it's vital that training is effective. Once in school, a robust induction programme coupled with ongoing mentoring from experienced subject experts helps early career teachers translate theoretical understanding into confident classroom practice.

Instructional coaching supports ongoing development. Regular observation, feedback, and collaborative planning help teachers refine their practice. The focus should be on deepening subject knowledge and improving the effectiveness of explicit instruction.

Implementing a knowledge-rich curriculum is demanding but profoundly rewarding. For students, it provides intellectual capital to understand the world, engage in complex conversations, and achieve academic success. It closes equity gaps and opens doors to future opportunities.

For educators, it's a deeply professionalising act. It re-centres the profession on subject passion and pedagogical expertise, fostering collaborative culture focused on education's core purpose: building knowledge.

This isn't about reaching a final, perfect curriculum. It's a commitment to continuous cycles of design, implementation, and refinement. It's a dynamic process of school reform, driven by a clear vision of what constitutes truly empowering education.

By placing powerful knowledge at the heart of their work, schools can build a lasting foundation for learning. This equips every student with understanding and confidence to thrive. In 2025 and beyond, as AI reshapes how we access information, the case for a knowledge-rich curriculum becomes stronger. Students need robust mental models, not just facts. They need deep understanding, not surface memorisation. They need powerful knowledge that transforms how they see and interact with the world.

Q: How is a knowledge-rich curriculum different from traditional teaching? A: It specifies exactly what knowledge students should learn, sequences it deliberately for schema building, and uses cognitive science strategies like retrieval practice to ensure knowledge reaches long-term memory. It's more intentional and evidence-based than ad hoc topic teaching.

Q: Won't this stifle creativity and critical thinking? A: No. Knowledge is the foundation for creativity and critical thinking. You can't think critically without something to think critically about. Students with deep knowledge can apply it creatively and evaluate ideas more effectively than those with surface understanding.

Q: How do I ensure my knowledge-rich curriculum is inclusive? A: Set the same ambitious knowledge expectations for all students. Differentiate through scaffolding and support, not by reducing content. Pre-teach vocabulary, use graphic organisers, and break complex ideas into steps while maintaining high expectations.

These five papers offer key critiques of the Knowledge-Rich curriculum and the Powerful Knowledge framework, challenging their assumptions, applications, and sociopolitical implications in curriculum design. Together, they provide essential insights for educators and subject leaders rethinking curriculum making, subject-specific knowledge, and equitable access to learning.

1. Knowledge and racial violence: the shine and shadow of ‘powerful knowledge’

Sophie Rudolph, A. Sriprakash & J. Gerrard (2018)

Challenges the epistemic neutrality of powerful knowledge by exposing its colonial roots, urging curriculum design to integrate racial justice within subject-specific curriculum frameworks.

2. ‘Powerful knowledge’, ‘cultural literacy’ and the study of literature in schools

Robert Eaglestone (2020)

Argues that applying scientific models of knowledge to English disfigures curriculum making, neglecting domain-specific knowledge and damaging subject disciplines like literature.

3. Powerful knowledge, educational potential and knowledge-rich curriculum: pushing the boundaries

Zongyi Deng (2022)

Repositions knowledge-rich curriculum toward human flourishing, critiquing rigid curriculum frameworks that ignore curriculum design's role in shaping domain-specific capabilities and subject leaders' agency.

4. Un-Standardizing Curriculum: Multicultural Teaching in the Standards-based Classroom

Christine Sleeter (2016)

Opposes standardised knowledge content, advocating curriculum design that balances academic rigour with subject-specific curriculum responsive to cultural and cognitive achievement gaps.

5. Debate and critique in curriculum studies: new directions?

Mark Priestley & S. Philippou (2019)

Reviews critiques of powerful knowledge and curriculum frameworks, calling for broader subject leader engagement and curriculum making that values educational practice and knowledge content.

A knowledge-rich curriculum specifies the essential content children should learn across year groups, recognising that skills like analysis or evaluation cannot develop independently from domain-specific knowledge. Rather than focusing on generic skills alone, it provides students with 'powerful knowledge' - conceptual understanding that gives learners new ways to think about the world beyond their immediate experiences.

Begin by identifying your core knowledge - map the pinnacle concepts, principles, and debates that define each subject, going beyond National Curriculum topic headings to specify granular knowledge requirements. Then sequence this knowledge so each piece builds on what came before, creating a coherent learning journey that develops logical schemas in students' long-term memory.

Knowledge organisers are single-page documents that summarise essential content for a unit, including key vocabulary, important dates, core concepts, diagrams, and crucial facts. They serve as tools to ensure teacher clarity and consistency, support student independent study, and provide parents with insight into their child's learning, though they are not the curriculum itself.

Research shows that learners forget 70% of new information within 24 hours without reinforcement, and students with broad background knowledge process new information more effectively, freeing up cognitive capacity for higher-order thinking. Strategies like retrieval practice, spaced repetition, and interleaving help combat forgetting curves and build durable, flexible long-term knowledge in semantic memory.

By specifying exactly what knowledge schools will teach, a knowledge-rich curriculum ensures all students have access to powerful knowledge regardless of their home background or resources. This approach recognises that children from higher socioeconomic groups enter school with cognitive scores 60% higher than peers from lower groups, making curriculum specification the most powerful equity intervention available.

AI actually makes powerful knowledge more important, not less, as students need structured schemas to evaluate AI outputs, identify inaccuracies, and apply information meaningfully. Without foundational understanding and deep subject knowledge, students cannot effectively evaluate whether an AI response makes sense or use AI tools productively for learning.

Schools must provide dedicated time for teachers to read, research, and collaborate with subject peers, treating curriculum development as core business. Professional learning should focus on both deepening subject expertise and understanding cognitive science principles, so teachers understand why strategies like retrieval practice and spaced repetition are effective for building long-term retention.