The Hypercorrection Effect: A Teacher's Guide

The hypercorrection effect shows confident errors are more easily corrected than uncertain ones, transforming how teachers approach mistakes and feedback.

The hypercorrection effect shows confident errors are more easily corrected than uncertain ones, transforming how teachers approach mistakes and feedback.

The hypercorrection effect is a learning phenomenon where students' most confident errors are actually the easiest to correct. This counterintuitive finding challenges everything teachers typically believe about mistakes: rather than being stubborn and resistant to change, errors made with high confidence are more likely to be remembered and corrected than tentative wrong answers. Research consistently shows that when students are certain they're right but receive corrective feedback, they experience a powerful learning moment that leads to lasting memory changes. Understanding this effect can transform how you approach mistakes in your classroom and transform your feedback strategies.

Understanding the hypercorrection effect transforms the way teachers approach student misconceptions. Rather than viewing confident errors as obstacles, we can recognise them as opportunities. The surprise students experience when discovering their confident beliefs are wrong appears to create powerful learning moments.

Key Takeaways

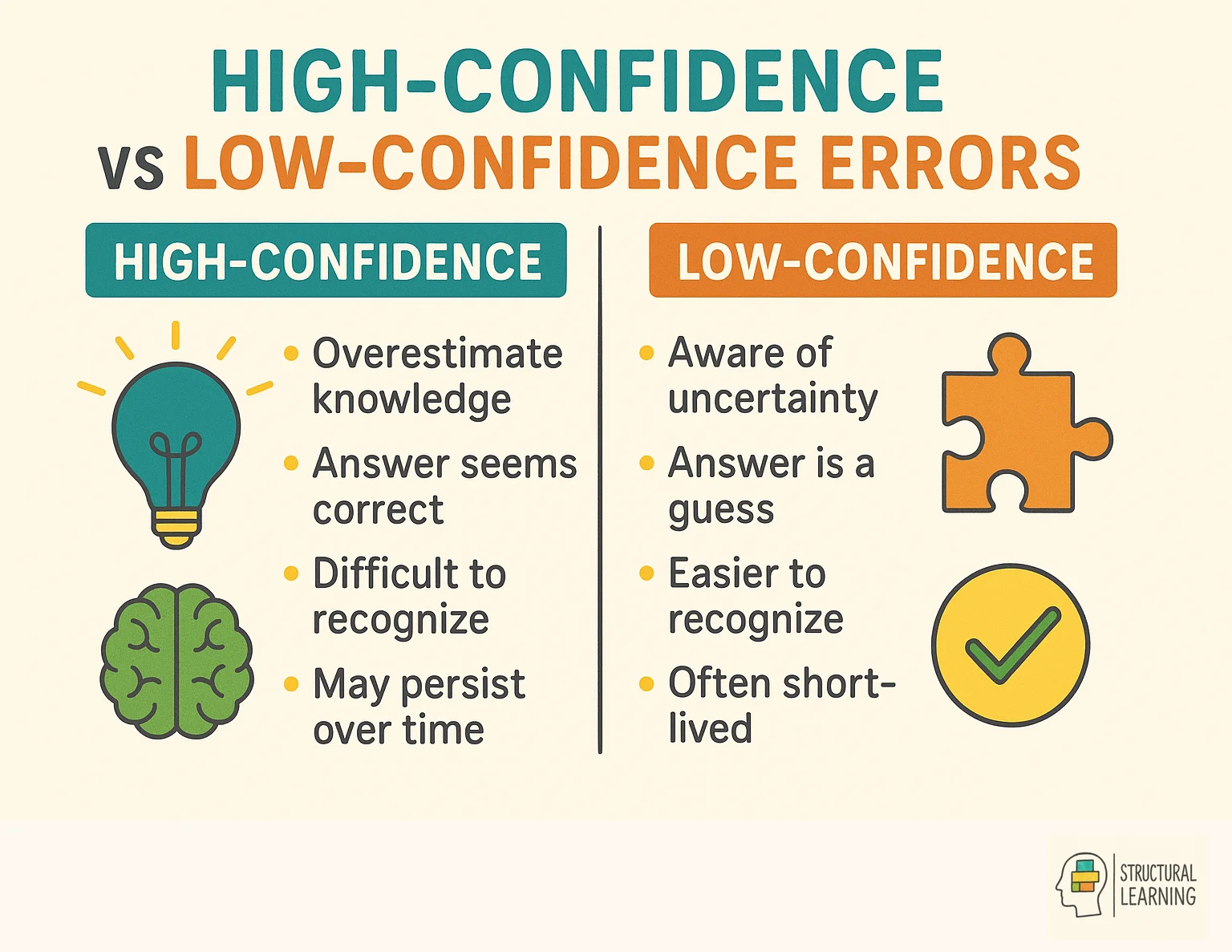

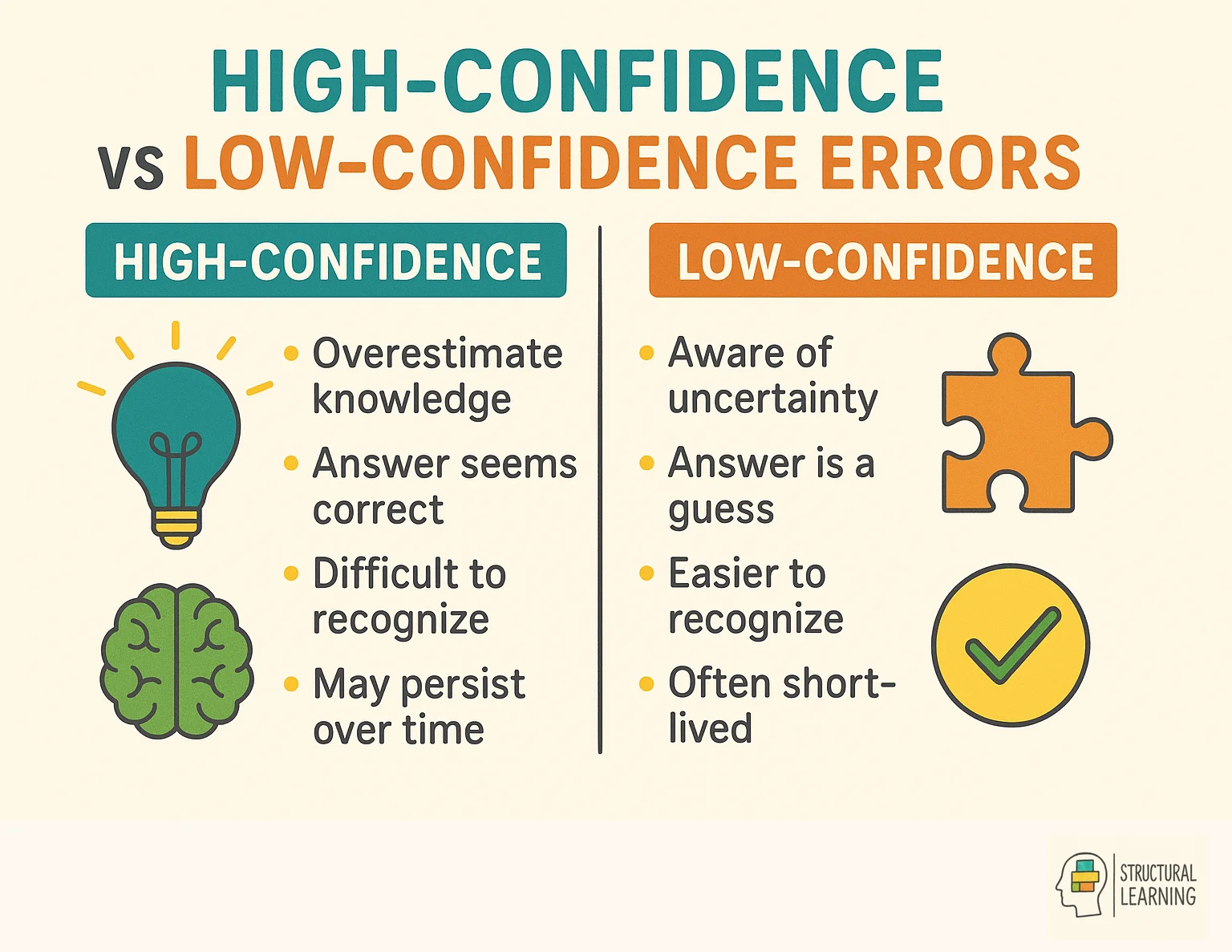

The hypercorrection effect describes a consistent finding in memory research: when people answer questions incorrectly but confidently, they are more likely to learn and remember the correct answer after receiving feedback than when they answer incorrectly with low confidence. High-confidence errors are, paradoxically, easier to fix.

The phenomenon was named by psychologists Janet Metcalfe and Brady Butterfield at Columbia University in 2001, though Raymond Kulhavy had noticed similar patterns in educational research during the 1970s. Since then, dozens of studies have replicated and extended the basic finding across different populations, materials, and settings.

Consider a typical experiment: participants answer general knowledge questions and rate their confidence in each answer. After answering, they receive feedback showing the correct answers. Later, they're tested again on the same questions. The consistent finding is that high-confidence errors show greater correction on the retest than low-confidence errors.

This pattern contradicts common intuition. Strong memories, we might assume, should be difficult to override. An error held with conviction might seem entrenched, resistant to change. The hypercorrection effect reveals that the opposite is often true in learning contexts.

Several theoretical explanations have been proposed for why confident errors are more readily corrected than tentative ones.

The dominant explanation centres on surprise. When people are highly confident in an answer and discover they're wrong, they experience a notable violation of expectations. This surprise captures attention and triggers enhanced processing of the corrective information.

By contrast, when people have low confidence in an answer and discover they're wrong, there's little surprise. They already suspected they might be incorrect. The confirmation of their uncertainty doesn't trigger the same attentional capture.

Neuroscience research supports this account. Studies using EEG have found stronger late positivity responses, associated with attention and surprise, when participants receive feedback on high-confidence errors compared to low-confidence errors. The brain responds differently to unexpected corrections.

Related to surprise, the hypercorrection effect may reflect differential attention and cognitive effort. When confident predictions are violated, people may work harder to understand and remember the correct information. They allocate more cognitive resources to processing the correction.

Low-confidence errors may receive less attention precisely because correction was expected. The discrepancy between belief and reality is smaller, triggering less effortful processing.

High-confidence errors may trigger more elaborative processing of the correction. When discovering a confident belief was wrong, people may think more deeply about why they were wrong, what led to their error, and how the correct answer differs from their incorrect answer. This process can benefit from developing metacognition and using thinking skills.

This elaboration creates richer memory traces for the correct information, potentially explaining enhanced retention. The error itself becomes a cue that helps retrieve the correction.

People typically have higher confidence in domains where they possess more prior knowledge. When a high-confidence error occurs, it may indicate richer background knowledge that, once corrected, supports better retention of the accurate information.

By this account, high-confidence errors are easier to correct not because of confidence per se but because of the knowledge structures that produced the confidence. The correction can integrate into an existing schema rather than floating in isolation.

Research supports this interpretation: people with higher domain knowledge show stronger hypercorrection effects. Their errors, though confident, connect to strong knowledge networks that support retention of corrections.

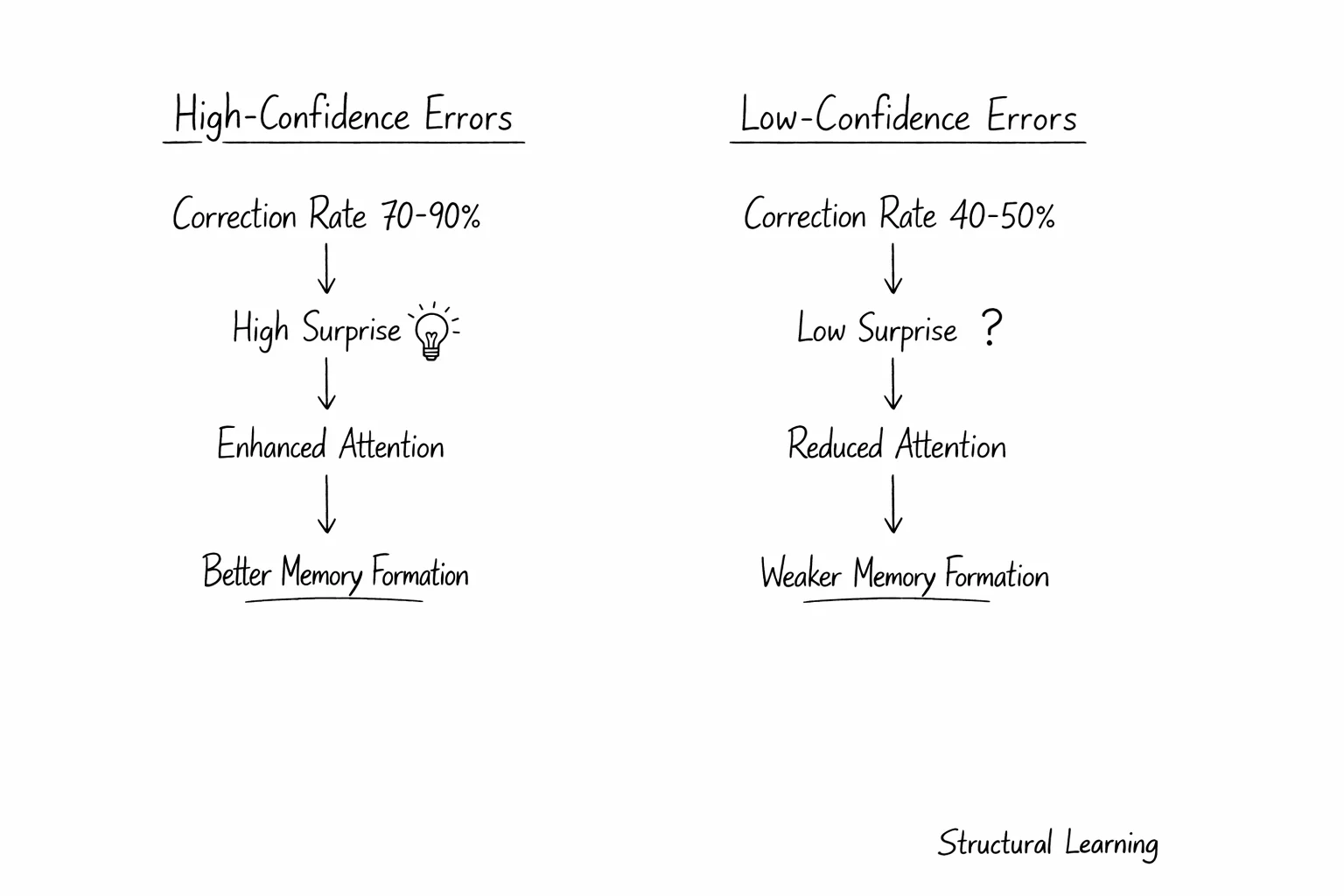

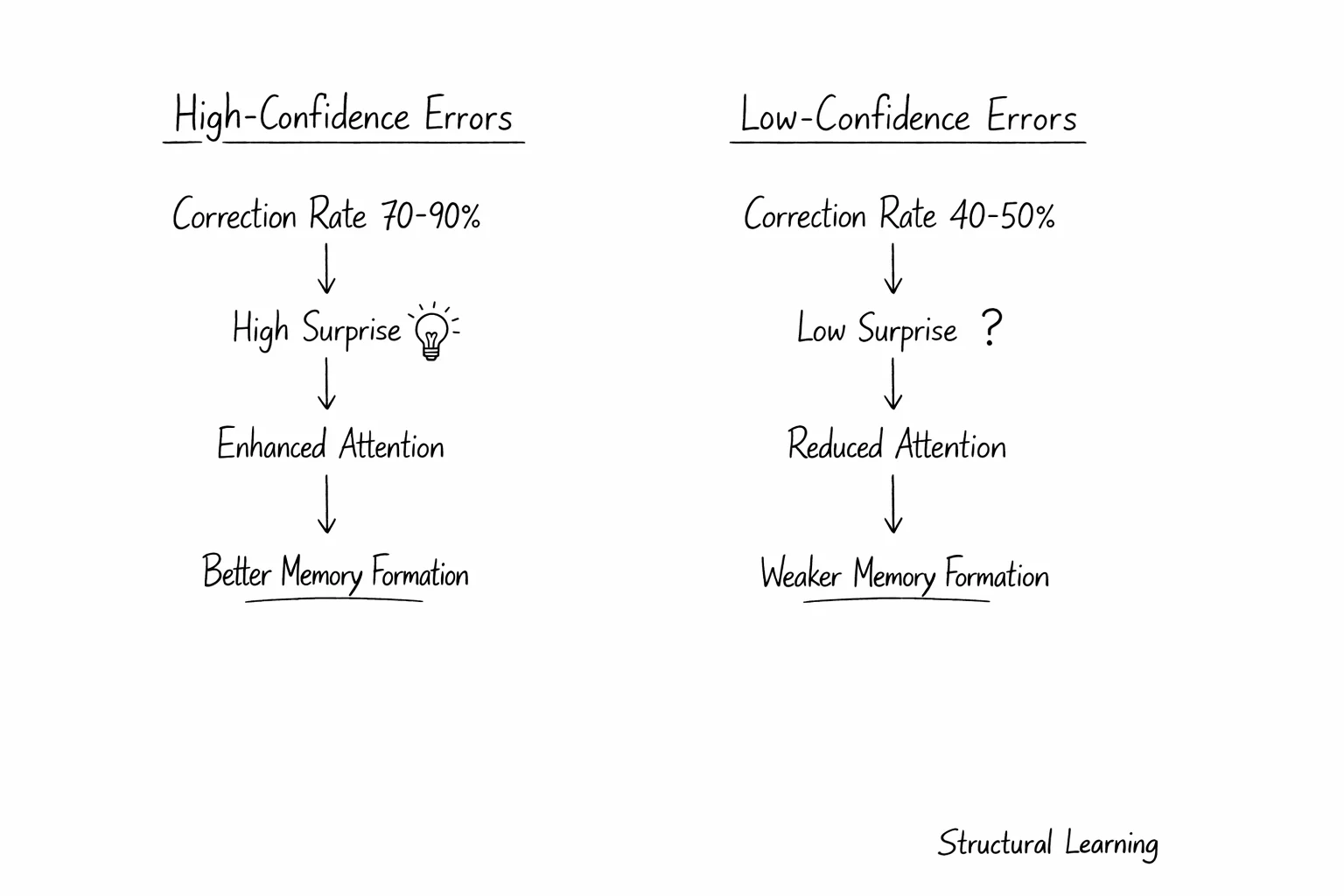

Multiple studies since 2001 have confirmed that high-confidence errors are corrected 70-90% of the time compared to only 40-50% for low-confidence errors. Research shows this effect persists across age groups, from elementary students to adults, and remains stable even after delays of several days or weeks.

The hypercorrection effect has been demonstrated across numerous studies with diverse populations and materials. This research supports approaches that embrace desirable difficulties and helps teachers implement effective marking approaches.

Butterfield and Metcalfe's original studies used general knowledge questions, showinggeneral knowledge questions, showing that high-confidence errors are more likely to be corrected on a later test. Subsequent laboratory studies have replicated this finding using different types of questions and tasks.

More recently, researchers have started examining the hypercorrection effect in real-world classroom settings. These studies confirm that the effect generalises beyond the laboratory.

For example, one study examined students learning science concepts. Students answered questions, received feedback, and then took a delayed test. The results mirrored laboratory findings: high-confidence errors showed better correction than low-confidence errors.

Classroom studies also suggest that the hypercorrection effect can be amplified with certain instructional techniques. For example, providing explanations alongside corrective feedback may enhance the effect. Encouraging students to reflect on their errors may also boost correction rates.

The hypercorrection effect has important implications for teachers. By understanding this phenomenon, educators can create more effective learning environments that use the power of mistakes.

The hypercorrection effect suggests that mistakes, especially confident ones, are not signs of failure but valuable opportunities for learning. Teachers should create a classroom culture that embraces mistakes as a natural part of the learning process.

Encourage students to share their reasoning, even when they're unsure. Create opportunities for students to self-correct and learn from their errors. Frame mistakes as stepping stones to deeper understanding.

To capitalise on the hypercorrection effect, consider eliciting confidence ratings from students. Ask them to rate how confident they are in their answers. This can be done through simple self-report scales (e.g., "How confident are you in your answer: Not at all, Somewhat, Very confident").

Identifying high-confidence errors allows you to target feedback more effectively. You can also use confidence ratings to tailor instruction and provide more personalised support. For instance, spend additional time explaining to students why a confident answer was wrong.

The hypercorrection effect relies on timely corrective feedback. Provide feedback as soon as possible after students make errors. This allows them to experience the surprise and engage in deeper processing of the correct information.

Ensure your feedback is clear, specific, and focused on the error. Explain why the answer was wrong and provide the correct answer along with a brief explanation. This can take the form of formative assessment or marking strategies.

Encourage students to reflect on their errors. Ask them to explain why they made the mistake, what they were thinking at the time, and how the correct answer differs from their initial response. This reflection enhances elaborative processing and strengthens memory for the correction.

Use strategies such as error analysis worksheets or think-pair-share activities to promote reflection. Create a classroom culture where students feel comfortable discussing their mistakes and learning from them.

The hypercorrection effect highlights the power of testing as a learning tool. Use regular quizzes and tests to identify and correct errors. Testing not only assesses learning but also provides opportunities for students to learn from their mistakes.

Incorporate feedback into your testing practices. Provide students with detailed explanations of the correct answers and encourage them to review their errors. Testing can be a powerful way to use the hypercorrection effect and promote lasting learning.

The hypercorrection effect offers a powerful insight into how we learn from our mistakes. By understanding that high-confidence errors are prime opportunities for learning, teachers can reshape their approach to classroom instruction and feedback. Creating a learning environment that embraces errors and provides timely, targeted feedback can significantly enhance student learning outcomes.

By embracing the hypercorrection effect, educators can transform mistakes from obstacles into stepping stones on the path to deeper understanding and lasting knowledge. This shift in perspective not only benefits students but also helps teachers to create more effective and engaging learning experiences.

Hypercorrection effect

The hypercorrection effect is a learning phenomenon where students' most confident errors are actually the easiest to correct. This counterintuitive finding challenges everything teachers typically believe about mistakes: rather than being stubborn and resistant to change, errors made with high confidence are more likely to be remembered and corrected than tentative wrong answers. Research consistently shows that when students are certain they're right but receive corrective feedback, they experience a powerful learning moment that leads to lasting memory changes. Understanding this effect can transform how you approach mistakes in your classroom and transform your feedback strategies.

Understanding the hypercorrection effect transforms the way teachers approach student misconceptions. Rather than viewing confident errors as obstacles, we can recognise them as opportunities. The surprise students experience when discovering their confident beliefs are wrong appears to create powerful learning moments.

Key Takeaways

The hypercorrection effect describes a consistent finding in memory research: when people answer questions incorrectly but confidently, they are more likely to learn and remember the correct answer after receiving feedback than when they answer incorrectly with low confidence. High-confidence errors are, paradoxically, easier to fix.

The phenomenon was named by psychologists Janet Metcalfe and Brady Butterfield at Columbia University in 2001, though Raymond Kulhavy had noticed similar patterns in educational research during the 1970s. Since then, dozens of studies have replicated and extended the basic finding across different populations, materials, and settings.

Consider a typical experiment: participants answer general knowledge questions and rate their confidence in each answer. After answering, they receive feedback showing the correct answers. Later, they're tested again on the same questions. The consistent finding is that high-confidence errors show greater correction on the retest than low-confidence errors.

This pattern contradicts common intuition. Strong memories, we might assume, should be difficult to override. An error held with conviction might seem entrenched, resistant to change. The hypercorrection effect reveals that the opposite is often true in learning contexts.

Several theoretical explanations have been proposed for why confident errors are more readily corrected than tentative ones.

The dominant explanation centres on surprise. When people are highly confident in an answer and discover they're wrong, they experience a notable violation of expectations. This surprise captures attention and triggers enhanced processing of the corrective information.

By contrast, when people have low confidence in an answer and discover they're wrong, there's little surprise. They already suspected they might be incorrect. The confirmation of their uncertainty doesn't trigger the same attentional capture.

Neuroscience research supports this account. Studies using EEG have found stronger late positivity responses, associated with attention and surprise, when participants receive feedback on high-confidence errors compared to low-confidence errors. The brain responds differently to unexpected corrections.

Related to surprise, the hypercorrection effect may reflect differential attention and cognitive effort. When confident predictions are violated, people may work harder to understand and remember the correct information. They allocate more cognitive resources to processing the correction.

Low-confidence errors may receive less attention precisely because correction was expected. The discrepancy between belief and reality is smaller, triggering less effortful processing.

High-confidence errors may trigger more elaborative processing of the correction. When discovering a confident belief was wrong, people may think more deeply about why they were wrong, what led to their error, and how the correct answer differs from their incorrect answer. This process can benefit from developing metacognition and using thinking skills.

This elaboration creates richer memory traces for the correct information, potentially explaining enhanced retention. The error itself becomes a cue that helps retrieve the correction.

People typically have higher confidence in domains where they possess more prior knowledge. When a high-confidence error occurs, it may indicate richer background knowledge that, once corrected, supports better retention of the accurate information.

By this account, high-confidence errors are easier to correct not because of confidence per se but because of the knowledge structures that produced the confidence. The correction can integrate into an existing schema rather than floating in isolation.

Research supports this interpretation: people with higher domain knowledge show stronger hypercorrection effects. Their errors, though confident, connect to strong knowledge networks that support retention of corrections.

Multiple studies since 2001 have confirmed that high-confidence errors are corrected 70-90% of the time compared to only 40-50% for low-confidence errors. Research shows this effect persists across age groups, from elementary students to adults, and remains stable even after delays of several days or weeks.

The hypercorrection effect has been demonstrated across numerous studies with diverse populations and materials. This research supports approaches that embrace desirable difficulties and helps teachers implement effective marking approaches.

Butterfield and Metcalfe's original studies used general knowledge questions, showinggeneral knowledge questions, showing that high-confidence errors are more likely to be corrected on a later test. Subsequent laboratory studies have replicated this finding using different types of questions and tasks.

More recently, researchers have started examining the hypercorrection effect in real-world classroom settings. These studies confirm that the effect generalises beyond the laboratory.

For example, one study examined students learning science concepts. Students answered questions, received feedback, and then took a delayed test. The results mirrored laboratory findings: high-confidence errors showed better correction than low-confidence errors.

Classroom studies also suggest that the hypercorrection effect can be amplified with certain instructional techniques. For example, providing explanations alongside corrective feedback may enhance the effect. Encouraging students to reflect on their errors may also boost correction rates.

The hypercorrection effect has important implications for teachers. By understanding this phenomenon, educators can create more effective learning environments that use the power of mistakes.

The hypercorrection effect suggests that mistakes, especially confident ones, are not signs of failure but valuable opportunities for learning. Teachers should create a classroom culture that embraces mistakes as a natural part of the learning process.

Encourage students to share their reasoning, even when they're unsure. Create opportunities for students to self-correct and learn from their errors. Frame mistakes as stepping stones to deeper understanding.

To capitalise on the hypercorrection effect, consider eliciting confidence ratings from students. Ask them to rate how confident they are in their answers. This can be done through simple self-report scales (e.g., "How confident are you in your answer: Not at all, Somewhat, Very confident").

Identifying high-confidence errors allows you to target feedback more effectively. You can also use confidence ratings to tailor instruction and provide more personalised support. For instance, spend additional time explaining to students why a confident answer was wrong.

The hypercorrection effect relies on timely corrective feedback. Provide feedback as soon as possible after students make errors. This allows them to experience the surprise and engage in deeper processing of the correct information.

Ensure your feedback is clear, specific, and focused on the error. Explain why the answer was wrong and provide the correct answer along with a brief explanation. This can take the form of formative assessment or marking strategies.

Encourage students to reflect on their errors. Ask them to explain why they made the mistake, what they were thinking at the time, and how the correct answer differs from their initial response. This reflection enhances elaborative processing and strengthens memory for the correction.

Use strategies such as error analysis worksheets or think-pair-share activities to promote reflection. Create a classroom culture where students feel comfortable discussing their mistakes and learning from them.

The hypercorrection effect highlights the power of testing as a learning tool. Use regular quizzes and tests to identify and correct errors. Testing not only assesses learning but also provides opportunities for students to learn from their mistakes.

Incorporate feedback into your testing practices. Provide students with detailed explanations of the correct answers and encourage them to review their errors. Testing can be a powerful way to use the hypercorrection effect and promote lasting learning.

The hypercorrection effect offers a powerful insight into how we learn from our mistakes. By understanding that high-confidence errors are prime opportunities for learning, teachers can reshape their approach to classroom instruction and feedback. Creating a learning environment that embraces errors and provides timely, targeted feedback can significantly enhance student learning outcomes.

By embracing the hypercorrection effect, educators can transform mistakes from obstacles into stepping stones on the path to deeper understanding and lasting knowledge. This shift in perspective not only benefits students but also helps teachers to create more effective and engaging learning experiences.

Hypercorrection effect

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/hypercorrection-effect-teachers-guide#article","headline":"The Hypercorrection Effect: A Teacher's Guide","description":"The hypercorrection effect shows that confident errors are more easily corrected than uncertain ones, transforming how teachers think about mistakes and feed...","datePublished":"2025-12-29T18:47:30.400Z","dateModified":"2026-01-26T10:09:32.212Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/hypercorrection-effect-teachers-guide"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/696e11a5898479282b7d0f23_69666aedae1c72d0c61e8bc0_69666aec417e8d79918f637b_hypercorrection-effect-teachers-guide-infographic.webp","wordCount":5814},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/hypercorrection-effect-teachers-guide#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"The Hypercorrection Effect: A Teacher's Guide","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/hypercorrection-effect-teachers-guide"}]}]}