Gibbs' Reflective Cycle: The Six Stages of Reflection Explained

Master Gibbs' Reflective Cycle with this complete guide. Learn the six stages of reflection with examples for education and nursing practice.

Gibbs' Reflective Cycle is a popular model for reflection, acting as a structured methodto enable individuals to think systematically about the experiences they had during a specific situation.

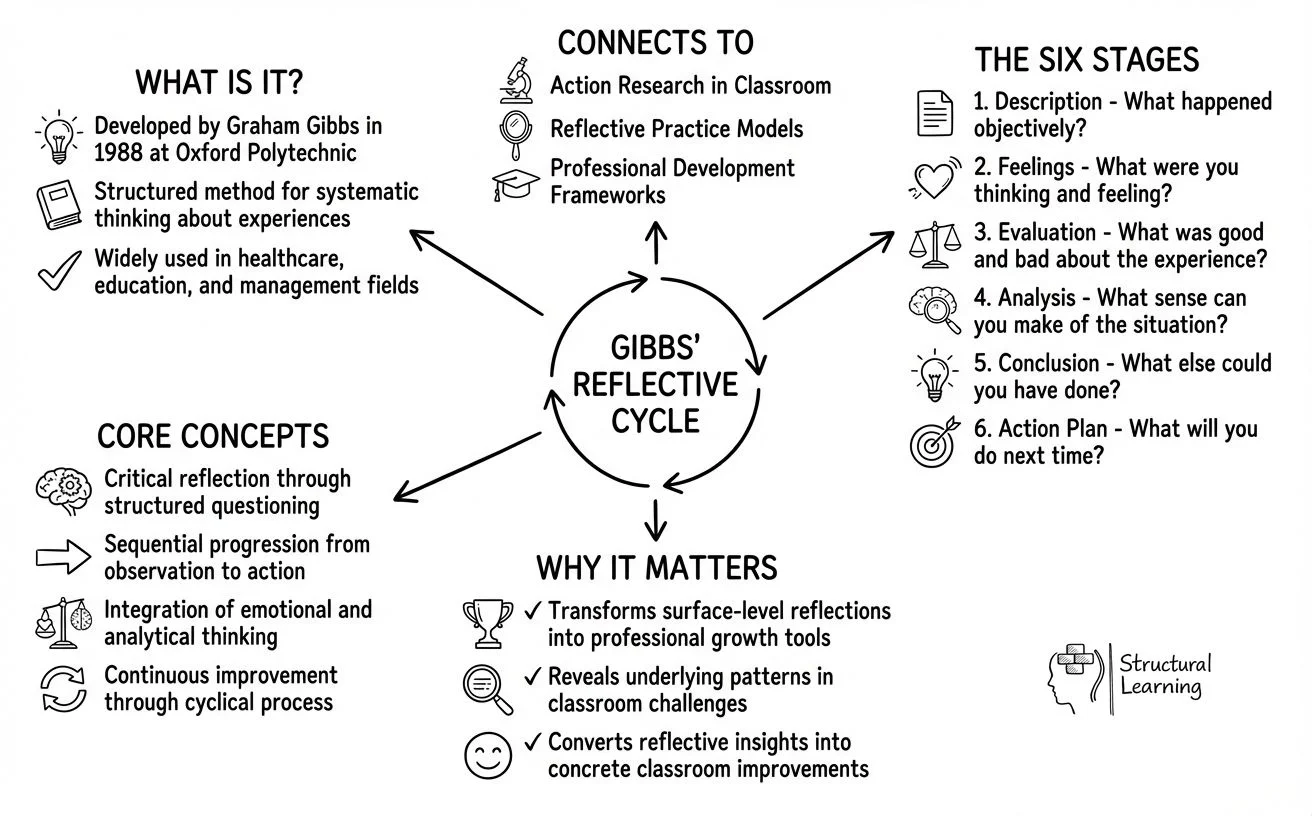

Gibbs’ Reflective Cycle is a widely used and accepted model of reflection. Developed by Graham Gibbs in 1988 at Oxford Polytechnic, now Oxford Brookes University, this reflective cycle framework is widely used within various fields such as healthcare, education, and management to enhance professional and personal development. It has since become an integral part of reflective practice, allowing individuals to reflect on their experiences in a structured way.

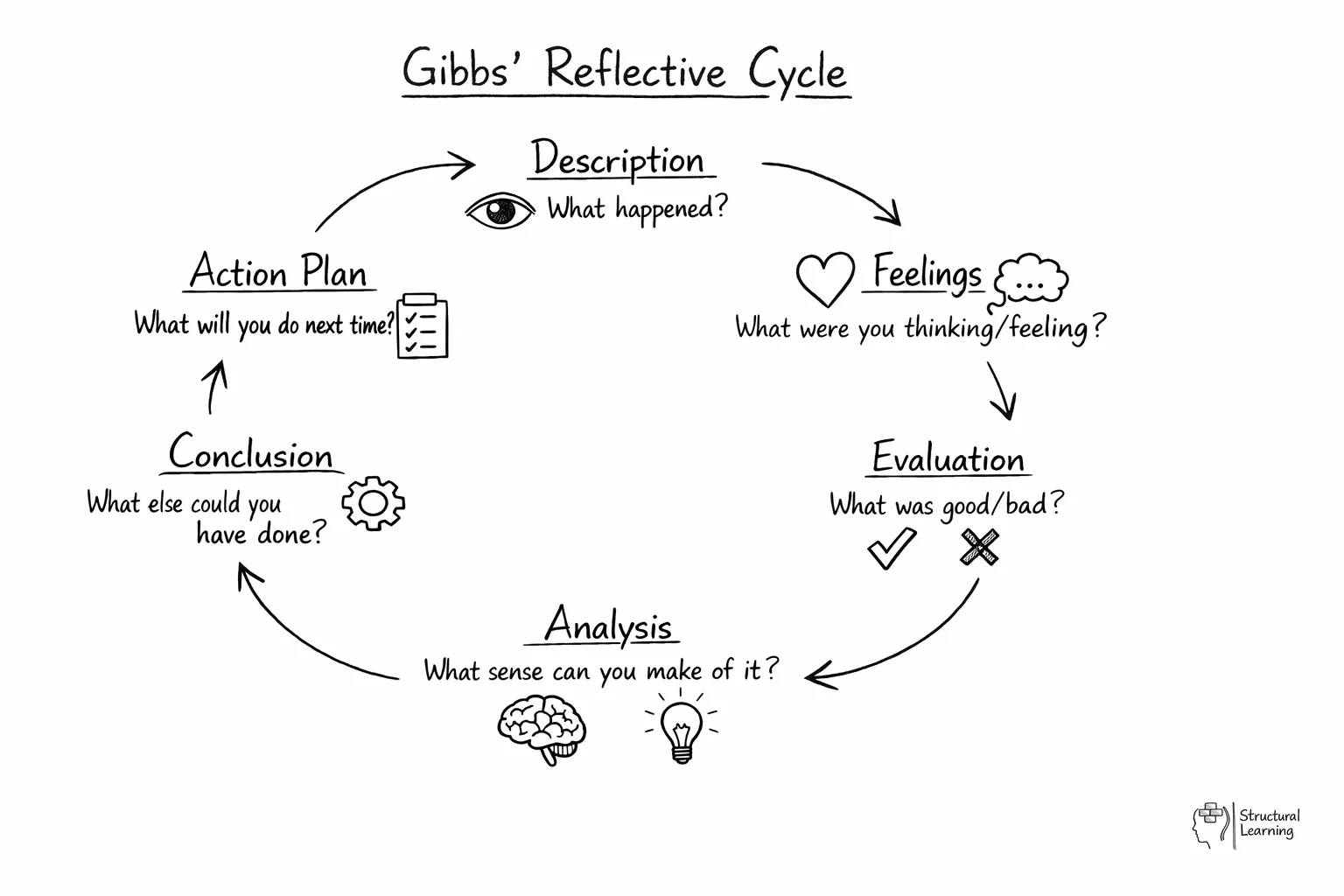

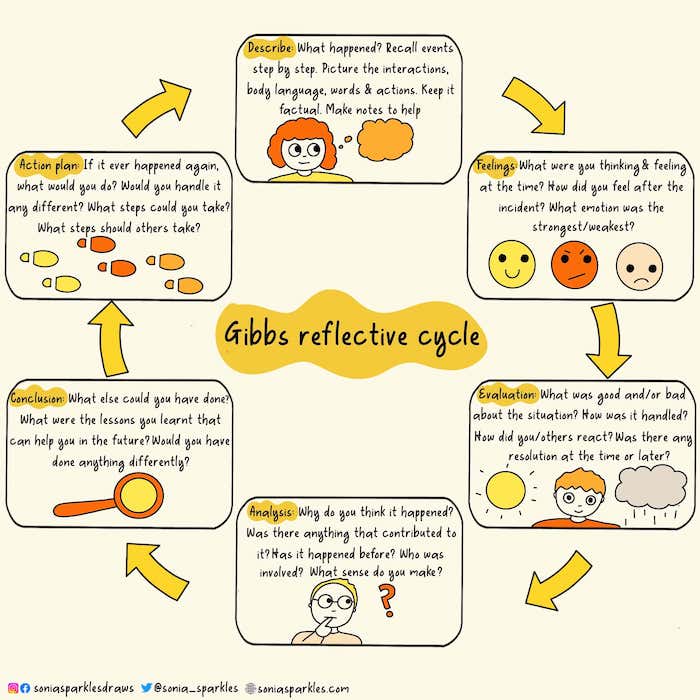

The cycle consists of six stageswhich must be completed in order for the reflection to have a defined purpose. The first stage is to describe the experience. This is followed by reflecting on the feelings felt during the experience, identifying what knowledge was gained from it, analysing any decisions made in relation to it and considering how this could have been done differently.

The final stage of the cycle is to come up with a plan for how to approach similar experiences in future.

Gibbs' Reflective Cycle encourages individuals to consider their own experiences in a more in-depth and analytical way, helping them to identify how they can improve their practice in the future.

A survey from the British Journal of Midwifery found that 63% of healthcare professionals regularly used Gibbs' Reflective Cycle as a tool for reflection.

"Reflection is a critical component of professional nursing practice and a strategy for learning through practice. This integrative review synthesizes the literature on nursing students’ reflection on their clinical experiences.", Beverly J. Bowers, RN, PhD

The six stages are: Description (what happened), Feelings (what were you thinking and feeling), Evaluation (what was good and bad), Analysis (what sense can you make of it), Conclusion (what else could you have done), and Action Plan (what will you do next time). Each stage builds on the previous one to create a comprehensive reflection process that moves from observation to concrete improvement strategies.

The Gibbs reflective cycle consists of six distinct stages: Description, Feelings, Evaluation, Analysis, Conclusion, and Action Plan. Each stage prompts the individual to examine their experiences through questions designed to incite deep and critical reflection. For instance, in the 'Description' stage, one might ask: "What happened?". This questioning method encourages a thorough understandingof both the event and the individual's responses to it.

To illustrate, let's consider a student nurse reflecting on an interaction with a patient. In the 'Description' stage, the student might describe the patient's condition, their communication with the patient, and the outcome of their interaction. Following this, they would move on to the 'Feelings' stage, where they might express how they felt during the interaction, perhaps feeling confident, anxious, or uncertain.

The 'Evaluation' stage would involve the student reflecting on their interaction with the patient, considering how they could have done things differently and what went well. In the 'Analysis' stage, the student might consider the wider implications of their actions and how this impacted on the patient's experience.

Finally, in the 'Conclusion' stage, the student would summarise their reflections by noting what they have learned from the experience. They would then set an 'Action Plan' for how they will apply this newfound knowledge in their future practice.

Gibbs' Reflective Cycle is a useful tool for nurses to utilise in order to reflect on their past experiences and improve their practice. By using reflective questions, nurses can actively engage in reflection and identify areas for improvement.

Teachers commonly use Gibbs' cycle to reflect on challenging lessons, student behaviour incidents, or new teaching strategies they've tried. For example, after a difficult class, a teacher might describe what happened, identify their frustration, evaluate what worked and didn't work, analyse why students were disengaged, conclude what alternative approaches could help, and create an action plan for the next lesson. This systematic approach transforms negative experiences into learning opportunities.

The Gibbs Reflective Cycle, a model of reflection, can be a powerful tool for learning and personal development across various vocations. Here are five fictional examples:

These examples illustrate how the Gibbs Reflective Cycle can facilitate learning and reflection across different vocations, leading to personal and professional growth.

Gibbs' cycle is effective because it provides a clear structure that prevents superficial reflection and ensures practitioners examine experiences from multiple angles. The model's strength lies in its progression from description to action, forcing users to move beyond simply recounting events to understanding why things happened and planning concrete improvements. This systematic approach makes it particularly valuable for mandatory CPD requirements and performance reviews.

Gibbs' Reflective Cycle offers a structured approach to reflection, making it a helpful tool for educators and learners alike. The model encourages critical reflection, stimulating the ability to analyse experiences through questions and transform them into valuable learning opportunities.

Experiential Learning, a concept closely tied with reflection, suggests that we learn from our experiences, particularly when we engage in reflection and active experimentation. Gibbs' model bridges the gap between theory and practice, offering a framework to capture and analyse experiences in a meaningful way.

By using Gibbs' model, educators can guide students through their reflective process, helping them extract valuable lessons from their positive and negative experiences.

Teachers should use Gibbs' cycle after significant classroom events, challenging situations, or when trying new teaching methods. It's particularly valuable for weekly lesson reflections, after parent conferences, following student assessments, or when dealing with classroom management issues. Regular use helps develop reflective habits that improve teaching practice over time.

The flexibility and simplicity of Gibbs' Reflective Cycle make it widely applicable in various real-world scenarios, from personal situations to professional practice.

For instance, Diana Eastcott, a nursing educator, utilised Gibbs' model to facilitate her students' reflection on their clinical practice experience. The students were encouraged to reflect on their clinical experiences, analyse their reactions and feelings, and construct an action plan for future patient interactions. This process not only enhanced their professional knowledge but also developed personal growth and emotional resilience.

In another example, Bob Farmer, a team leader in a tech company, used Gibbs' Cycle to reflect on a project that didn't meet expectations. He guided his team through the reflective process, helping them identify areas for improvement and develop strategies for better future outcomes.

These scenarios underline the versatility of Gibbs' model, demonstrating its value in both educational and professional settings.

Gibbs' cycle supports professional growth by providing a framework that transforms everyday teaching experiences into learning opportunities. The structured approach helps teachers identify patterns in their practice, recognise areas for improvement, and develop evidence-based strategies for enhancement. This systematic reflectiondirectly feeds into professional development plans and helps teachers demonstrate continuous improvement.

The use of Gibbs' Reflective Cycle can have profound effects on personal and professional development. It aids in recognising strengths, weaknesses, and areas for improvement, providing an avenue for constructive feedback and self-improvement.

In the context of professional development, Gibbs' model promotes continuous learning and adaptability. By transforming bad experiences into learning opportunities, individuals can enhance their competencies and skills, preparing them for similar future situations.

Moreover, the reflective cycle promotes emotional intelligence by encouraging individuals to explore their feelings and reactions to different experiences. Acknowledging and understanding negative emotions can lead to increased resilience, better stress management, and improved interpersonal relationships.

Unlike simple diary entries or casual reflection, Gibbs' cycle requires systematic analysis through six distinct stages that build toward actionable improvements. The model's Analysis stage specifically pushes practitioners to examine underlying causes and patterns rather than stopping at surface-level observations. This depth ensures that reflection leads to genuine professional learningand concrete changes in practice.

Gibbs' Reflective Cycle is a practical tool that transforms experiences into learning. It incorporates principles of Experiential Learning and emphasises the importance of abstract conceptualization and active experimentation in the learning process.

In the field of education, Gibbs' model can significantly influence teaching methods. It encourages educators to incorporate reflective practices in their teaching methods, promoting a deeper understanding of course material and facilitating the application of theoretical knowledge in practical scenarios.

Moreover, the model can be used to encourage students to reflect on their experiences, both within and outside the classroom, and learn from them. This process creates critical thinking, problem-solving skills, and personal growth, equipping students with the skills they need for lifelong learning.

Schools can implement Gibbs' cycle by incorporating it into professional development programs, peer observation frameworks, and performance management processes. Start by training staff in the six stages, providing templates and examples, then integrate the cycle into regular meeting structures and CPD activities. Successful implementation requires leadership support and clear expectations about when and how staff should use the framework.

Here's a list of guidance tips for organisations interested in embracing Gibbs' Reflective Cycle as their professional development model.

Both Kolb's Experiential Learning Theory and Gibbs' Reflective Cycle are influential learning methods used extensively in education and professional development. While they share similarities, such as promoting a cyclical learning process and developing a deeper understanding of experiences, there are key differences.

Kolb's cycle consists of four stages: Concrete Experience, Reflective Observation, Abstract Conceptualization, and Active Experimentation. It focuses more on the transformation of direct experience into knowledge, emphasising the role of experience in learning.

On the other hand, Gibbs' cycle, with its six stages, places a greater emphasis on emotions and their impact on learning. For example, a team leader might use Kolb's cycle to improve operational skills after a failed project, focusing on what happened and how to improve. However, using Gibbs' cycle, the same leader would also reflect on how the failure made them feel, and how those feelings might have influenced their decision-making.

| Learning Cycle Theory | Origin | Application |

|---|---|---|

| Experiential Learning Theory (ELT) | Developed by David Kolb in the 1980s. It's based on the work of John Dewey, Kurt Lewin, and Jean Piaget. | It's widely used in professional development and higher education settings. It helps learners gain knowledge from their experiences by going through four stages: Concrete Experience, Reflective Observation, Abstract Conceptualization, and Active Experimentation. |

| 5E Instructional Model | Developed by the Biological Sciences Curriculum Study (BSCS) in the 1980s. | This model is popular in science education. It includes five phases: Engagement, Exploration, Explanation, Elabouration, and Evaluation. It promotes inquiry-based learning and active engagement. |

| ADDIE Model | The origins can be traced back to the US Military in the 1970s. | It's widely used in instructional design and training development. The five phases are Analysis, Design, Development, Implementation, and Evaluation. |

| Kemp Design Model | Developed by Jerold Kemp in the late 1970s. | This model is used in instructional design. It emphasises continuous revision and flexibility throughout the learning cycle, including nine components that are considered simultaneously and iteratively. |

| Gagne's Nine Events of Instruction | Developed by Robert Gagne in the 1960s. | This is commonly used in instructional design and teaching. It includes nine steps: Gain attention, Inform learners of objectives, Stimulate recall of prior learning, Present the content, Provide learner guidance, Elicit performance, Provide feedback, Assess performance, and Enhance retention and transfer. |

| ARCS Model of Motivational Design | Developed by John Keller in the 1980s. | This model is used to improve learners' motivation. The four components are Attention, Relevance, Confidence, and Satisfaction. It is widely used in e-learning and instructional design. |

| Bloom's Taxonomy | Developed by Benjamin Bloom in the 1950s. | It is used to classify educational learning objectives into levels of complexity and specificity. The taxonomy consists of six levels: Remembering, Understanding, Applying, Analyzing, Evaluating, and Creating. It is widely used in education to design lesson plans and assessments. |

Please note that each of these theories or models has been developed and refined over time, and they each have their own strengths and weaknesses depending on the specific learning context or goals.

The main benefits include improved classroom practice through systematic reflection, better professional development outcomes, and enhanced ability to handle challenging classroom situations. Teachers who regularly use Gibbs' cycle report increased confidence in trying new strategies and better understanding of student needs. The framework also provides clear documentation for performance reviews and professional portfolios.

Gibbs' Reflective Cycle is an invaluable tool for nurturing professional skills and developing personal growth. By systematically integrating this reflective model into educational practices, institutions can significantly enhance their students' professional development.

Here are seven effective ways educational institutions can harness the power of Gibbs' Reflective Cycle to boost skill acquisition, operational proficiency, leadership capabilities, and personal skills mastery.

Teachers can start by selecting one significant classroom event per week and working through all six stages using a template or journal. Begin with shorter reflections of 15-20 minutes, focusing on completing each stage rather than perfection. As the process becomes familiar, extend to more complex situations and use the cycle for collabourative reflection with colleagues.

In the journey of life and work, we continuously encounter new situations, face challenges, and make decisions that shape our personal and professional trajectory. It's in these moments that Gibbs' Reflective Cycleemerges as a guiding compass, providing a structured framework to analyse experiences, draw insights, and plan our future course of action.

Underlying the model is the philosophy of lifelong learning. By encouraging critical reflection, it helps us to passively experience life and to actively engage with it, to question, and to learn. It's through this reflection that we move from the field of 'doing' to 'understanding', transforming experiences into knowledge.

Moreover, the model emphasises the importance of an action-oriented approach. It propels us to use our reflections to plan future actions, promoting adaptability and growth. Whether you're an educator using the model to enhance your teaching methods, a student exploring the depths of your learning process, or a professional striving for excellence in your field, Gibbs' Reflective Cycle can be a powerful tool.

In an ever-changing world, where the pace of change is accelerating, the ability to learn, adapt, and evolve is paramount. Reflective practices, guided by models such as Gibbs', provide us with the skills and mindset to navigate this change effectively. They helps us to learn from our past, be it positive experiences or negative experiences, and use these lessons to shape our future.

From developing personal growth and emotional resilience to enhancing professional practice and shapingfuture outcomes, the benefits of Gibbs' Reflective Cycle are manifold. As we continue our journey of growth and learning, this model serves as a beacon, illuminating our path and guiding us towards a future of continuous learning and development.

Key resources include Gibbs' original 1988 text 'Learning by Doing', practical guides from teaching colleges, and online templates specifically designed for educational contexts. Many universities provide free downloadable worksheets and video tutorials that demonstrate each stage of the cycle. Professional development courses often include modules on reflective practice using Gibbs' framework.

Here is a list of five key studies examining the effectiveness of Gibbs' Reflective Cycle in promoting critical reflection across different domains. These studies explore the cycle's structured approach in enhancing reflective practice, its role as a helpful and practical tool, and how it informs future actions.

These studies collectively illustrate the broad applicability of Gibbs’ Reflective Cycle across academic, professional, and healthcare settings, reinforcing its role as a structured and practical tool for developing reflective practice.

Gibbs' Reflective Cycle is a structured six-stage framework developed by Graham Gibbs in 1988 that transforms surface-level descriptions into powerful tools for professional growth. Unlike simple diary entries that merely record what happened, this model systematically guides educators through description, feelings, evaluation, analysis, conclusion, and action planning to create meaningful development opportunities.

The six stages are Description (what happened), Feelings (thoughts and emotions), Evaluation (what was good and bad), Analysis (making sense of the experience), Conclusion (what else could have been done), and Action Plan (future approach). Each stage builds on the previous one to create a comprehensive reflection process that moves systematically from observation to concrete improvement strategies.

Teachers commonly use the cycle to reflect on challenging lessons, student behaviour incidents, or new teaching strategies. For example, after a difficult class, they would describe what happened, identify their emotions, evaluate successes and failures, analyse why students were disengaged, conclude alternative approaches, and create an action plan for future lessons.

Most teachers stop at identifying 'what went wrong' in the evaluation stage and miss the analysis phase where they draw on professional knowledge and literature to understand why things unfolded as they did. This analysis stage is crucial because it reveals underlying patterns in classroom challenges and transforms observations into deeper professional insights.

Instead of treating CPD reflections as a tick-box exercise, teachers can use the six-stage framework to structure their professional development systematically. This approach ensures they move beyond surface-level reporting to genuine analysis and concrete action planning that directly improves their instructional approach.

The main challenge is moving beyond the comfortable description and evaluation stages to engage in deeper analysis that requires drawing on professional knowledge and research. Teachers may also struggle with being honest about their emotions in the feelings stage or creating specific, actionable plans rather than vague intentions for improvement.

The action planning stage transforms reflective insights into concrete, implementable strategies by requiring teachers to specify exactly what they will do differently in similar future situations. This final stage prevents reflection from becoming merely an intellectual exercise and ensures it leads to tangible changes in pedagogical methods that 'actually stick'.

The feelings stage of Gibbs' Reflective Cycle serves as more than a simple emotional inventory. Recent research by Saraçoğlu et al. (2025) highlights how emotional experiences in educational settings occur within complex sociocultural contexts, where interactions can be emotionally intense. For teachers, this stage requires honest examination of both their own emotions and their students' emotional responses during the teaching experience. Rather than dismissing feelings as irrelevant to professional practice, this stage recognises emotions as valuable data that inform teaching effectiveness.

When engaging with this stage, teachers should explore emotions chronologically: initial feelings before the lesson, emotional shifts during teaching moments, and residual feelings afterwards. Chaudhri et al. (2023) found that emotions tend to have a significant impact on students' learning outcomes, making it crucial for teachers to understand the emotional climate of their classroom. Consider recording specific triggers for emotional responses, such as a student's unexpected question that caused anxiety or the satisfaction felt when a struggling pupil grasped a difficult concept. This detailed emotional mapping reveals patterns that might otherwise remain hidden.

A critical skill in this stage involves separating personal emotional responses from professional ones. For instance, frustration with a transformative student might stem from personal tiredness rather than the student's behaviour itself. Teachers should ask themselves: "Would I have felt differently if this happened at a different time or under different circumstances?" This distinction prevents misattribution and leads to more accurate analysis in later stages. Research by Mokhele-Ramulumo et al. (2025) demonstrates how understanding emotional responses shapes attitudes and behaviours, suggesting that teachers who accurately identify their emotional triggers can better manage classroom dynamics.

The feelings stage also requires acknowledging uncomfortable emotions without judgement. Many teachers feel pressured to maintain perpetual positivity, yet recognising feelings of disappointment, inadequacy, or even anger provides crucial insights for professional development. Document these emotions using specific language rather than general terms: instead of writing "felt bad," specify whether you felt overwhelmed, underprepared, or dismissed. This precision creates a richer foundation for the evaluation stage that follows, where you'll assess what went well and what didn't. Remember, the goal isn't to eliminate negative emotions but to understand their sources and impacts on your teaching practice.

The evaluation stage marks a critical turning point in Gibbs' Reflective Cycle where teachers move beyond emotional responses to make objective judgements about their classroom experiences. Unlike the feelings stage, evaluation requires you to step back and assess both the positive and negative aspects of a situation without letting emotions cloud your judgement. This balanced approach prevents the common teaching trap of focusing solely on what went wrong, which research by MacNeil et al. (2023) suggests can limit professional growth when stakeholders engage in one-sided evaluations of their experiences.

Effective evaluation in teaching contexts requires a structured approach that goes beyond simple 'good' or 'bad' categorisations. Start by identifying specific elements that worked well, such as a particular questioning technique that sparked student engagement or a classroom management strategy that maintained focus during transitions. Then examine what didn't work, but frame these observations constructively. For instance, rather than noting "the group work failed," evaluate specific aspects: "Students in mixed-ability groups completed tasks at different speeds, leaving some disengaged." This granular approach to evaluation provides clearer direction for the analysis stage that follows.

To ensure balanced evaluation, create two columns labelled "Effective Elements" and "Areas for Development." Under each, list specific observations with brief evidence. For example, under "Effective Elements," you might write: "Visual timer on board, 95% of students transitioned within 2 minutes." This technique prevents the natural tendency to dwell on negatives whilst ensuring you capture successful strategies that might otherwise be forgotten. The evaluation stage differs from peer-based faculty evaluation discussed by Akins and Murphy (2019), as it focuses on self-assessment rather than external judgement, making it less threatening and more conducive to honest reflection.

A crucial but often overlooked aspect of evaluation is considering unintended outcomes. Perhaps your carefully planned differentiated worksheet inadvertently highlighted ability gaps, affecting student confidence. Or maybe your attempt to incorporate technology enhanced engagement but reduced meaningful peer interaction. These unexpected results often provide the richest material for professional development. By evaluating both intended and unintended outcomes, you create a comprehensive picture that feeds directly into the analysis stage, where you'll explore why these outcomes occurred and identify patterns across multiple teaching experiences.

While many teachers understand the six stages of Gibbs' Reflective Cycle, they often struggle with knowing exactly what to ask themselves at each stage. Simply knowing the stages isn't enough; you need targeted questions that probe deeper into your teaching practice. Research by Roberts et al. (2025) on critical design strategies demonstrates that structured questioning methods significantly enhance reflective thinking, a principle that applies directly to classroom reflection.

The quality of your reflection depends entirely on the questions you ask. Generic prompts like "What happened?" produce surface-level responses that rarely lead to meaningful change. Instead, each stage requires specific questions that challenge assumptions and uncover hidden patterns in your teaching practice. For the Description stage, rather than simply recounting events, ask: "What specific student behaviours indicated engagement or confusion?" and "Which transitions between activities created momentum or disruption?" These targeted questions transform basic observation into actionable data.

As you move through the cycle, your questions should build upon previous insights. In the Feelings stage, avoid stopping at "I felt frustrated." Instead, probe with: "What specific moment triggered this emotion?" and "How did my emotional state influence my teaching decisions?" The Analysis stage, often the most neglected, requires questions that connect theory to practice: "Which pedagogical principles were at play when the lesson succeeded/failed?" and "What patterns emerge when I compare this experience to similar situations?"

The final stages demand forward-thinking questions. For the Conclusion stage, ask: "What would I need to change about my planning, not just my delivery?" and "Which of my teaching assumptions has this experience challenged?" The Action Plan stage moves beyond vague intentions with questions like: "What specific resources or support do I need to implement this change?" and "How will I measure whether my new approach works?" This progression mirrors the taxonomy development process described by Finelli and Borrego (2014), where systematic questioning leads to clearer categorisation and understanding of complex educational phenomena.

Transform these questions into a personal reflection toolkit by adapting them to your subject area and teaching context. A science teacher might focus questions on labouratory management and practical demonstrations, whilst a primary teacher could emphasise questions about differentiation across ability levels. The key is maintaining the progressive depth whilst making each question relevant to your specific classroom challenges.

These peer-reviewed studies provide the research foundation for the strategies discussed in this article:

Teachers talking about teaching and school: collabouration and reflective practice via Critical Friends Groups

43 citations

L. Kuh (2016)

This paper examines how teachers can use Critical Friends Groups to engage in collabourative reflection about their teaching practice. These structured peer discussion groups provide teachers with a supportive space to share challenges, receive constructive feedback, and improve their professional practice through collective problem-solving, which directly supports the collabourative reflection emphasised in Gibbs' cycle.

Avita Rath (2024)

Though focused on health professions, this paper offers teachers a framework for understanding how reflective practice shapes professional identity development. Teachers can apply these insights to help students in professional or vocational programs think critically about how their personal values align with their career responsibilities, making reflection more meaningful and identity-focused rather than just a routine exercise.

AI in the Classroom: A Systematic Review of Barriers to Educator Acceptance

2 citations

Ellaine Joy G. Eusebio et al. (2025)

This systematic review identifies the key obstacles teachers face when deciding whether to adopt AI technologies in their classrooms. Understanding these barriers, from lack of training to concerns about job security and student data privacy, helps teachers and administrators address resistance thoughtfully and implement AI tools more effectively through informed reflection on their concerns and needs.

AI in Higher Education: Initial Teacher Training in the Critical and Didactic Use of Artificial Intelligence

2 citations

Sebastián Martín-Gómez & C. J. González Ruiz (2025)

This study demonstrates how teacher training programs can integrate AI tools like ChatGPT and Gemini into coursework through a structured six-phase approach emphasising critical thinking and verification. Teachers can learn from this model to thoughtfully incorporate AI into their own practice, using reflection to question outputs, compare sources, and verify information rather than accepting AI-generated content uncritically.

Emotional labour as teaching expertise: reflective practices for teacher professional development workshops

1 citations

Mandie Bevels Dunn et al. (2025)

This research highlights the often-overlooked emotional demands of teaching, from managing difficult parent conversations to supporting struggling students, and argues that reflective practice should address these challenges explicitly. Teachers can benefit from professional development that includes reflection on emotional labour, helping them develop strategies for managing stress and building relationships while maintaining their wellbeing and effectiveness in the classroom.

These peer-reviewed studies provide deeper insights into gibbs' reflective cycle: the six stages of reflection explained and its application in educational settings.

Experiential learning. 2613 citations

Wooding et al. (2019)

This chapter explores experiential learning, which is the process of learning through direct experience combined with reflection on that experience. It is highly relevant to teachers using Gibbs' Reflective Cycle as it emphasises how reflection transforms raw experience into meaningful learning, which aligns perfectly with the structured reflection stages that Gibbs provides.

REFLECTIVE TEACHING TOWARD EFL TEACHERS’ PROFESSIONAL AUTONOMY: REVISITING ITS DEVELOPMENT IN INDONESIA 16 citations

Lubis et al. (2018)

This paper examines the development of reflective teaching practices among English as a Foreign Language teachers in Indonesia over 25 years, focusing on how reflection promotes teacher autonomy and continuous professional development. It is valuable for teachers learning about Gibbs' Reflective Cycle as it demonstrates the real-world application and long-term benefits of structured reflection in teaching practice, particularly in developing critical thinking skills and lifelong learning habits.

Revitalising reflective practice in pre-service teacher education: developing and practicing an effective framework 17 citations

Roberts et al. (2021)

This research develops and tests a framework to help pre-service teachers understand and practice reflective thinking effectively, addressing common difficulties students face in grasping the importance of reflection. It is particularly relevant for teachers exploring Gibbs' Reflective Cycle as it provides evidence-based strategies for implementing structured reflection frameworks and demonstrates how systematic approaches to reflection can be taught and developed in educational settings.

Promoting pre-service teachers' professional vision of classroom management during practical school training: Effects of a structured online- and video-based self-reflection and feedback intervention 141 citations

Weber et al. (2018)

This study investigates how structured online and video-based reflection and feedback interventions can improve pre-service teachers' ability to analyse and understand classroom management during practical training. It is relevant to teachers using Gibbs' Reflective Cycle as it demonstrates how technology-enhanced structured reflection can be applied to specific teaching challenges, showing practical ways to implement systematic reflection processes in teacher development.

Boris et al. (2021)

This paper explores how reflective teaching approaches can enhance teacher professional development, positioning reflective practices as essential tools for ongoing teacher growth and improvement. It is directly relevant to teachers learning about Gibbs' Reflective Cycle as it provides broader context for why structured reflection matters in teaching and demonstrates the connection between systematic reflection and continuous professional development.