Securing more objective news sources for our students

How can we help students navigate through a world of misinformation? Roy White provides schools with some practical ideas.

Teaching students to identify objective news sources starts with establishing clear evaluation criteria they can apply to any article or outlet. Educators need practical frameworks that help learners distinguish between credible journalism and biased content, whilst developing the critical thinking skills to navigate today's complex media landscape. The most effective approach combines teaching source verification techniques with hands-on practise using current examples. However, there's one fundamental skill that transforms how students consume news forever, yet most teachers never explicitly teach it.

This article aims to provoke student reflection, discussion and action concerning the use of propaganda and other forms of misinformation that deliberately distort perceptions of events and promote discord between and across communities. Although the context is the war in Ukraine, the questions and ideas pre sen ted are also offered as a catalyst for creating a better and more peaceful world by securing a more trustworthy media for us all.

Introduction:

“If you believe in something, you must think or talk or write and must act.”

(Alex Peterson, as cited in IBO, 2010)

Students and teachers around the world are currently discussing the pretext for the conflict in Ukraine and seeking ways to help mitigate against the effects of this war on the region and beyond. The kindness, generosity, and collegiality shown by many individuals, groups and governments have been a model for student action, and we should be gratified by the those who are united in caring for displaced people and ending this war. Schools will need to provide long term support for the wellbeing of the child refugees while helping them to learn. Beyond this, we must examine the causes of such conflict and take whatever steps we can, to prevent such wars from happening in the future.

Through the lens of this conflict, we clearly see that there are leaders today who consciously manipulate and restrict information to distort our perceptions of their actions and to provoke mistrust, discord, and violence. Although social media has made it easier for ‘citizen journalists’ to counter propaganda, this war demonstrates that our modern media and communication technologies also facilitate and embolden those who wish to cascade mistruths.

This misuse of information poses a clear and present danger to our peace, security, and general happiness. We must therefore seek to understand and minimise its affects in connection with all other Global Issues that require our action (Brown, 2022). As with all complex and challenging international issues we will need the ingenuity and support of peoples across the globe to secure and execute the most effective and effective strategies (Matic and Matic, 2022).

Educators have a key role to play in raising awareness of such issues. Thus, this article contains questions, background information, and suggestions, that teachers can use to provoke student reflection, debate, and action. To start this process a non-fiction account of a conversation is used to highlight just one of the many related challenges that we face connected with the misuse and manipulation of information.

Students resist changing their perceptions because misinformation often comes from trusted sources within their social or family networks. Cognitive dissonance makes it psychologically uncomfortable for students to accept information that contradicts their existing beliefs. Traditional critical thinking approaches fail against modern propaganda techniques that are specifically designed to bypass rational analysis.

“Does she really need to leave the country? The army will soon be there to help. They will stop the Ukrainian Nazis from attacking other Ukrainians.” (7 March 2022)

These are the words of a parent of a school leader in South America who has just called to discuss his ‘dilemma’. For weeks he has become more and more concerned for the safety of his relatives living in the Ukraine. He is particularly worried for his cousin who is caring for her one-year-old daughter, and her father who has a brain tumor.

Today, this colleague happily informed me that not only had his cousin and daughter made it to Warsaw but in “thirty minutes” they would be landing safely in a more northerly European city. I asked him if they had a place to live. He said,

“This is the problem. My cousin and daughter are to stay with one of my parents, who has been watching only state media from a country nearby. This parent has no idea about the dreadful situation in Ukraine and cannot understand why my cousin has had to leave. Although, I have tried explaining some of the details, I have not had much luck penetrating my parent’s current understanding. I think the planned living arrangements are not going to work.”

There are others who share this perspective of the war, and many more who have developed ‘alternative versions of reality’ in relation to other world events and issues.

Internationally minded educators must accept that people from other cultures will have different views, opinions, and attitudes, but this does not mean we have to accept relativistic truth, in which any idea, however unjustified, is to be deemed as having merit. While teachers must always aim to be objective, and must carefully respect cultural differences, we have a responsibility to help our students to construct versions of reality that correct for fal sel y manufactured realities. In short “There is no point in [the teacher] being more mature if…” we are not going to use that insight to help students construct truth (Dewey, 1958).

As my colleague discovered during his conversations within his parent, it can be rather difficult to change someone’s views. McGee (2017) explains that if one “…holds a false belief and faces a competing true belief, the strain of cognitive dissonance may cause them to prefer retaining their existing false belief over re writing their belief system.” It is easy to understand why changing the perspective of this pa rent would therefore be so difficult, as it might require the parent to re-examine the high levels of trust they have placed on the media and government. We concluded that although it was important to try, it was unlikely this parent would change their views quickly.

In the end, my colleague decided that his cousin and her daughter should live with him and his family in South America. He flew this week to that northern city to pick them up.

Modern information systems create echo chambers where misinformation spreads faster than verified facts, making truth appear tribal rather than objective. Social media algorithms amplify sensational and divisive content while suppressing nuanced, factual reporting. The democratization of publishing means propaganda now appears alongside legitimate journalism without clear distinctions for students.

My colleague and I wondered what educators could be doing, to help lessen the impact of propaganda and other false narratives placed in the public domain.

US Supreme Court Justice, Oliver Wendell Holmes (1919), stated that “The best test of truth is the power of the thought to get itself accepted in the competition of the market…”.

His definition of truth has two key prerequisites:

Unfortunately, we seem unable to meet either of these two requirements. We must first have access to information. Although in principle the UDHR affords us this freedom, unfortunately there are many governments today that regularly restrict access. Even in more democratic regions, where access should be freely available, the rise of populist movements, hinders free access by permitting only one perspective to dominate. In populist politics it appears that truth becomes that which is:

Populists, typically rely on a single source for their news. In this way, they eliminate the possibility of any cognitive dissonance, and instead feel emboldened and comforted by hearing the echoing voices of their own strongly held beliefs (Brooks, 2020).

Even if people are made aware of more thanone competing narrative, there must be a general willingness to evaluate them to make an informed judgement. Unfortunately, once a ‘first truth’ has been accepted, we seem very unwilling to consider alternatives, even if the original idea is shown later to be illogical, dangerous, or contrary to our supposed values.[1]

As McGee (2017) suggests, one of the reasons for this is that it may require us to abandon a deeper set of beliefs.

Today, truth seems to have become tribal (Brooks, 2020). People will take a political stance and then no matter what perspective the leaders from their selected political group may proffer, they will support it, for fear of having to abandon their deep-rooted belief in their politics.

Even if the tribal nature of our politics did not exist, our modern world offers fewer opportunities for critically reflection. Within our world of, tweets and short text messages, and without deep conversations at the dinner table, there seems to be far less opportunity to reflect deeply on issues, our values and to evaluate political positions.

In short, the marketplace envisaged by Justice Holmes no longer seems to exist for establishing verifiable truth. Consequently, we risk furthering and deepening already entrenched positions, exacerbating disharmony, and making it easier for conflicts both within and across communities to take root.

The passage from Justice Holmes (1919) goes on to say that this marketplace definition of truth, although a basis for the American Constitution, “… is an experiment, as all life is an experiment”. We have had over thirty years of this experiment and we must either find an alternative model for truth or find a way for people to be afforded sources for news which are more professionally and ethically produced.

Students should practise evaluating competing narratives by analysing the propaganda tactics used in different sources covering the same event. Cross-referencing information across multiple international news sources helps students identify bias and verify facts independently. Role-playing exercises where students create and identify propaganda help them recognise manipulation techniques in real media.

The following are a few suggestions to be used as a catalyst for discussions within and outside our school communities. The overall aim of our discussions and actions should be to ensure for a better and more peaceful world by reflecting on the problems connected with our modern media, communication, and truth.

Think pair share thinking routine" width="auto" height="auto" id="">

Think pair share thinking routine" width="auto" height="auto" id="">

Misinformation creates invisible barriers to learning that many teachers don't recognise until it's too late. When students arrive in class with pre-formed misconceptions from unreliable sources, they often struggle to engage with factual content, even when presented with evidence. This cognitive resistance isn't stubbornness; it's a natural psychological response called confirmation bias, where students unconsciously filter new information through their existing beliefs.

Research by Wineburg and McGrew (2019) reveals that students who regularly consume misinformation show decreased ability to evaluate source credibility over time. More concerning, these students often display overconfidence in their analytical skills whilst performing poorly on fact-checking tasks. In practical terms, this means a student who reads conspiracy theories about climate change may dismiss scientific evidence in geography lessons, not because they lack intelligence, but because misinformation has rewired their approach to evaluating truth.

The classroom impact extends beyond individual subjects. Students exposed to misinformation often struggle with:

Teachers can spot these effects through simple observation. Watch for students who cite "everyone knows" as evidence, refuse to acknowledge uncertainty in complex topics, or become defensive when sources are questioned. These behaviours signal that misinformation has already shaped their learning approach.

Most importantly, misinformation creates what psychologists term "epistemic closure", where students stop questioning information that confirms their beliefs. This closure transforms classrooms from spaces of inquiry into echo chambers, undermining the very foundation of education: the ability to think critically and adapt understanding based on evidence.

When students encounter information that contradicts their existing beliefs, their brains often work against accepting the correction. This psychological resistance, known as the backfire effect, can actually strengthen their original misconceptions when confronted with factual evidence. Understanding these barriers helps educators develop more effective approaches to teaching media literacy and critical evaluation skills.

Social identity plays a powerful role in how students process information. When a piece of misinformation aligns with their peer group's beliefs or family values, rejecting it feels like betraying their community. For instance, a student whose family strongly supports a particular political viewpoint may dismiss credible news sources that challenge that perspective, labelling them as 'biased' without examining the evidence. This tribal thinking intensifies during controversial events, making classroom discussions about current affairs particularly challenging.

Teachers can address these barriers through structured activities that reduce defensive reactions. One effective strategy involves asking students to argue for positions they disagree with, helping them understand how different perspectives form. Another approach uses anonymous belief surveys before and after examining evidence, allowing students to change their minds without losing face. When discussing the Ukraine conflict, for example, teachers might present historical timelines from multiple sources, asking students to identify differences without immediately judging which is 'correct'.

Research by Lewandowsky et al. (2012) suggests that successful correction requires replacing the misinformation with a clear, simple alternative explanation. Rather than simply debunking false claims, teachers should help students construct new mental models that explain events more accurately. This process takes time and repetition, but ultimately builds stronger critical thinking skills than traditional fact-checking exercises alone.

Teaching students to evaluate news sources requires hands-on practise with real-world examples. Rather than lecturing about bias and credibility, effective educators create opportunities for students to actively investigate and compare different media outlets themselves.

One powerful activity involves the 'Same Story, Different Angles' exercise. Present students with coverage of the same news event from three different sources: a tabloid, a broadsheet, and an international outlet. Ask students to identify specific differences in language choice, quoted sources, and which facts are emphasised or omitted. For instance, comparing how The Sun, The Guardian, and Al Jazeera report on the same political protest reveals stark contrasts in framing. Students quickly recognise how word choices like 'protesters' versus 'rioters' shape reader perception.

Another effective approach is the 'Source Detective' challenge. Provide students with a sensational news claim and task them with tracing it back to its original source. They must document each step: who first reported it, what evidence was provided, and how the story changed as other outlets repeated it. This exercise, based on Stanford University's research on lateral reading, teaches students to verify claims by checking multiple sources rather than diving deeper into a single article.

The 'Bias Spectrum' activity helps students move beyond binary thinking about media objectivity. Create a physical line in your classroom representing a spectrum from 'highly biased' to 'relatively objective'. Give students various news excerpts and ask them to physically position themselves along the spectrum based on their assessment. The ensuing discussions about why students chose different positions naturally leads to deeper understanding of how personal perspectives influence our perception of bias.

These activities transform abstract concepts about media literacy into concrete skills students can apply immediately. By practising source evaluation in a structured environment, students develop the confidence to question and verify information independently.

When presented with evidence that contradicts their beliefs, students often double down rather than reconsider. This resistance isn't stubbornness; it's a predictable psychological response that teachers must understand to effectively combat misinformation. Research shows that confirmation bias, the tendency to seek information supporting existing beliefs whilst ignoring contradictory evidence, intensifies during adolescence when identity formation peaks.

The backfire effect presents another challenge in the classroom. When students encounter fact-checks that challenge their worldview, they may actually strengthen their original beliefs. This occurs particularly when the misinformation aligns with their social group's values or family perspectives. For instance, a student who believes a false narrative about climate change shared by trusted family members may reject scientific evidence presented in lessons, viewing it as an attack on their identity rather than an educational opportunity.

Teachers can address these barriers through specific strategies. First, the "stealth correction" approach works effectively: present correct information without explicitly labelling the misconception as wrong. When discussing controversial topics, begin with areas of agreement before introducing conflicting evidence. Second, use the "consider the source" exercise where students examine the same event reported by five different outlets, identifying emotional language and missing context before revealing which sources are considered most reliable.

Social media algorithms compound these biases by creating filter bubbles that reinforce existing beliefs. Students rarely realise their feeds show curated content designed to maximise engagement, not accuracy. A practical classroom activity involves students swapping phones to examine each other's news feeds, revealing how different their information ecosystems have become. This visceral demonstration often proves more powerful than abstract discussions about media bias.

Teaching students to evaluate news sources requires structured activities that move beyond theoretical discussion. The most effective lessons combine immediate practise with real-world examples, allowing students to develop their analytical skills through direct experience rather than passive instruction.

One particularly effective activity is the 'Source Detective' exercise. Provide students with three articles covering the same news event: one from a reputable outlet, one from a partisan source, and one containing clear misinformation. Working in pairs, students identify specific language choices, missing context, and verification methods used in each piece. This comparative analysis helps learners recognise bias patterns whilst building confidence in their judgement. Teachers can extend this by having students create a 'reliability rubric' based on their findings, which they then test against new articles.

Another powerful approach involves reverse engineering news stories. Give students a factual event, then task them with writing two versions: one following journalistic standards and another incorporating propaganda techniques. This creative exercise demonstrates how easily facts can be manipulated through selective emphasis, emotional language, or strategic omissions. Research by Wineburg (2018) shows that students who create biased content themselves become significantly better at detecting it in authentic sources.

The 'verification relay' transforms fact-checking into an engaging group activity. Teams race to verify claims from social media posts using lateral reading techniques; students must find three independent sources confirming or debunking each claim. This gamified approach teaches practical skills whilst highlighting how quickly misinformation spreads compared to the time needed for proper verification. Teachers report that students begin applying these techniques spontaneously to content they encounter outside lessons, suggesting genuine skill transfer rather than surface-level compliance.

Teachers should present students with contrasting news reports about the same event from different countries or political perspectives. Students can research how the same story is covered across various media outlets to identify propaganda techniques and bias. These debates should focus on analysing media tactics rather than defending political positions, helping students separate truth from manipulation.

Section A: Take a Stand

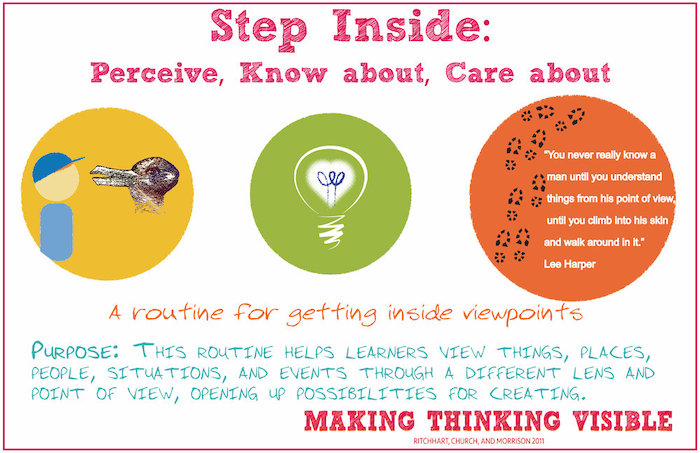

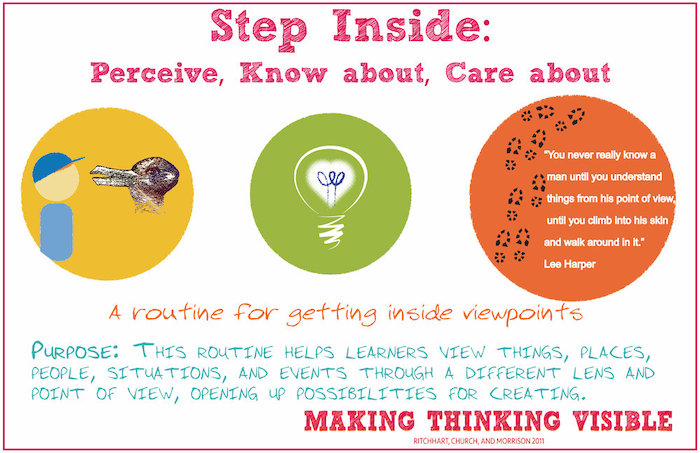

The Project Zero Thinking Routine, ‘ Take a Stand’can be used with the following examples to initiate deep discussions of issues related to this article. The Educators Guide provides other age-appropriate ideas that can be used directly or refined to better align with our focus on misinformation and the media.

Further Questions:

(Further reading: The Spycatcher case)

Further Questions:

Does such polarisaton within our media insight violence? Should, TV programmes provide opportunities for extreme voices to be heard? Would it make any difference in your answer if there is an opportunity for a lengthy formalized debate or just a short commentary of views on mainstream media? Should we allow racists, holocaust deniers, and others to present their views? Are there groups/individuals that should not be offered airtime? Why/Whynot? Where do you draw the line?

Schools should implement media literacy programmes that go beyond traditional critical thinking to address modern propaganda techniques. Training teachers to recognise and discuss misinformation helps create a school-wide culture of factual inquiry. Partnering with international schools allows students to compare how the same events are reported in different countries and media systems.

a) Create an exhibition, production, performance, or competition that showcases the work of Artists, Choreographers, Poets, Writers, and Directors to help us to reflect on the dangers of propaganda, nationalism, populism, and/or xenophobia.

b) Create a lesson within your Art, Drama, Literature, History or PSE class which will similarly help us to reflect on these dangers.

The quote by Alec Peterson at the start of this article recognises that there are times when me must act. ‘While we may start by having opportunities to think, to write and to reflect, educators across the globe have a duty to help us take the necessary steps which will lead to a better and more peaceful world. We must therefore initiate conversations connected with the misuse, manipulation, and control of our modern media.

This issue should be the keynote topic for educational conferences once COVID restrictions have ended.

Academic research on misinformation, cognitive bias, and propaganda techniques provides the foundation for effective media literacy education. Studies on student perception formation and resistance to belief change inform teaching strategies that actually work. International educational frameworks and case studies offer practical approaches for implementing anti-misinformation curricula in schools.

Abrams v. United States, 250 U.S. 616 (1919)

Aljazera (2022), ‘Russia’s parliament approves jail for ‘fake’ war reports’ [Online] Available at:

Https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/3/4/russia-prison-media-law-fake-reports-ukraine-war(Accessed 15 March 20220)

Bath University (2020), ‘How tribalism polarized the Brexit social media debate’[Online] Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g1mTHswNaAw (Accessed 15 March 2022)

BBC (2008) ‘World War II Behind Closed Doors: Stalin, the Nazis and the West, Video Documentary, Laurence Reese and Andrew Williams

Brandies, L. (1913), ‘What Publicity Can Do’ , Harper’s Weekly, 20 December 1913, [Online] Available at: http://3197d6d14b5f19f2f4405e13d-29c4c016cf96cbbfd197c-579b45.r81.cf1.rackcdn.com/collection/papers/1910/1913_12_20_What_Publicity_Ca.pdf(Accessed 8 March 2022)

Brooks, M. (2020), ‘Here's Why Tribalism Trumps Truth: We like to think that we are reasonable, but our politics show otherwise.’, Psychology Today, [Online] Available at:https://thinkingmuseum.com/2021/03/17/how-to-use-zoom-in-thinking-routine-in-art-discussions/(Accessed 14 March 2022)

Brown, K. (2022), ‘5 GLOBAL ISSUES TO WATCH IN 2022, United Nations Foundation, [Online] Available at: https://unfoundation.org/blog/post/5-global-issues-to-watch-in-2022/(Accessed 14 March 2022)

Common Sense Education, ‘Take a Stand: Educator Guide’, Harvard University, Project Zero, Online] Available at: http://www.pz.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/Take%20a%-20Stand%20-%20Educator%20Guide.pdf(15 March 2022)Dewey, J. (1954).

Experience and education (The Kappa Delta Pi lecture series)New York: Macmillan. P. 23

Gordon, R. (2015), ‘The Fight that Changed Political TV Forever: Half a century ago, William Buckley and Gore Vidal brilliantly castigated each other on air. It’s been downhill ever since’, Politico magazine, [Online] Available at: https://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2015/08/04/william-buckley-gore-vidal-debates-1968-121009/ (Accessed 14 March 2022)

Harvard Graduate School of Education (2021) ‘Digital dilemmas Thinking Routine, Take a Stand -Resources’, Project Zero, [Online] Available at: http://www.pz.harvard.edu/resources/take-a-stand (Accessed 15 March 2022)

IBO (2010), ‘Creativity, action, service guide’, Peterson House, Malthouse Avenue, Cardiff Gate, Wales

IBO (2012), ‘International education: it’s time to think again: Teachers, and the IB, are going beyond flags and festivals, so how can educators create truly global teaching with a little uncommon thinking? [Online] Available at: https://www.ibo.org/ib-world-archive/september-2012/international-education-its-time-to-think-again/ (Accessed 15 March 2022)

Laurence, R (2008) ‘World War II Behind Closed Doors: Stalin, the Nazis and the West. Barnes & Nobles Publishing. ISBN 978-0-307-37730-2.

Matic, G. And Matic, A. (2022),’ Collective Innovation for Complex Challenges: Engaging With Meta-Cognitive Skills and Patterns’, In Achieving Sustainability Using Creativity, Innovation, and Education: A Multidisciplinary Approach (pp. 69-96). IGI Global.

McGee, D. (2017) ‘The ‘Marketplace of Ideas’ is a Failed Market’, [Online] Available at:https://medium.com/@danmcgee/the-marketplace-of-ideas-is-a-failed-market-5d1a7c106fb8 (Accessed 14 March 2022)

Morrissey L. (2017), ‘Alternative facts do exist: beliefs, lies and politics’, The Conversation [Online] Available at: https://theconversation.com/alternative-facts-do-exist-beliefs-lies-and-politics-84692(Accessed 14 March 2022)

Thinking Museum (2020), ‘How to use the Zoom in thinking routine in art lessons’, [Online] Available at: https://thinkingmuseum.com/2021/03/17/how-to-use-zoom-in-thinking-routine-in-art-discussions/(Accessed 14 March 2022)

[1]The ‘Zoom In’ thinking routine can get students used to the idea of having to adjust their hypoth esis with new information. See: Thinking Museum (2020) . There are many other useful thinking routines from Harvard’s Project Zero.

Misinformation is specifically designed to bypass rational analysis and often comes from trusted sources within students' social or family networks. Cognitive dissonance makes it psychologically uncomfortable for students to accept information that contradicts their existing beliefs, causing them to reject contradictory evidence even when presented with facts.

Teachers must remain objective and respect cultural differences whilst helping students construct versions of reality that correct for falsely manufactured narratives. The key is distinguishing between legitimate cultural perspectives and objectively false information, focusing on helping students develop skills to identify propaganda techniques rather than attacking their sources directly.

Teachers can use current conflicts like Ukraine as a lens to expose propaganda tactics and demonstrate how misinformation spreads through echo chambers. The article suggests using thinking routines like 'Circle of Viewpoints' to help students examine multiple perspectives whilst developing skills to identify when information sources are deliberately distorting perceptions.

Students develop tribal loyalty to information sources, which can override their critical thinking skills and create dangerous echo chambers. When misinformation aligns with their existing beliefs, cognitive dissonance prevents them from questioning these narratives, making them particularly vulnerable to propaganda from trusted sources.

Whilst social media has enabled 'citizen journalists' to counter propaganda, modern communication technologies also facilitate and embolden those who wish to spread mistruths. Social media algorithms amplify sensational and divisive content whilst suppressing nuanced, factual reporting, making it harder for students to distinguish between legitimate journalism and propaganda.

Educators have a key responsibility to raise awareness about misinformation and help students understand how it connects to broader global issues. Teachers should provoke student reflection, debate, and action by providing questions, background information, and strategies that help students recognise when information is being manipulated to promote discord between communities.

Schools must provide long-term support for the wellbeing of displaced students whilst examining the root causes of conflicts, including how leaders manipulate information to distort perceptions and provoke violence. This dual approach helps refugee students whilst educating all students about the dangers of propaganda and the importance of securing trustworthy media sources.

THE EFFECTS OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE TEACHING ENRICHED WITH DIGITAL APPLICATIONS ON TEACHER COGNITION AND STUDENT BELIEFS View study ↗

Aslıhan Arıkan & Dilek Peçenek (2024)

This large-scale study involving 49 teachers and 214 students across 35 cities examined how integrating digital applications into English language teaching affects both teacher thinking and student attitudes. The research provides valuable insights into the real-world impact of educational technology on classroom dynamics and learning mindsets. English teachers considering digital integration will benefit from understanding how technology adoption influences both their own teaching approach and their students' beliefs about language learning.

Revisiting the Three Basic Dimensions model: A critical empirical investigation of the indirect effects of student-perceived teaching quality on student outcomes View study ↗

15 citations

Ayşenur Alp Christ et al. (2024)

This research investigates how teaching quality actually translates into student achievement and interest in mathematics, examining the pathways through student engagement, time spent learning, and motivation. The study reveals which aspects of good teaching have the strongest indirect effects on student outcomes, going beyond surface-level measures. Mathematics teachers will gain evidence-based insights into how their instructional choices influence student success through multiple interconnected factors.

Encouraging Students' Creative Writing through Multimodal Strategies within a Linguistic Framework View study ↗

Dessy Wardiyah et al. (2025)

This classroom action research with 30 high school students shows how combining visual, auditory, and interactive media significantly enhanced creative writing abilities over two teaching cycles. The study demonstrates that engaging multiple senses and learning modalities helps students develop stronger imagination and linguistic expression in their writing. Writing teachers will discover practical multimodal strategies that can transform their creative writing instruction and boost student engagement.

Montessori and Contextual Teaching Learning Method for Beginning Reading Abilities View study ↗

Agustina Dewi Rakhmawati et al. (2025)

This research addresses common early reading challenges like letter recognition difficulties and low reading interest by combining Montessori principles with contextual teaching methods in kindergarten settings. The study specifically focuses on helping children who struggle with distinguishing similar symbols and connecting sounds to written forms. Early childhood educators will find valuable strategies for supporting young learners with reading difficulties through structured, meaningful learning experiences.

These peer-reviewed studies provide the research foundation for the strategies discussed in this article:

BEAM Me Up: Teaching Rhetorical Methods for Source Use and Synthesis View study ↗

3 citations

Ashley Roach-Freiman (2021)

This research introduces the BEAM framework, which helps students understand why authors use different sources by categorizing them based on the author's purpose, whether to provide background, evidence, argument, or method. Rather than just teaching students to evaluate whether sources are good or bad, this approach teaches them to think critically about how and why sources are being used in different contexts. Teachers can use this framework to help students become more sophisticated readers who understand the strategic choices authors make when incorporating sources into their work.

EducationQ: Evaluating LLMs' Teaching Capabilities Through Multi-Agent Dialogue Framework View study ↗

9 citations

Yao Shi et al. (2025)

Researchers developed a new system to test how well artificial intelligence tools can actually teach students by creating simulated classroom conversations between AI teachers, students, and evaluators. The study tested 14 different AI systems to see which ones were most effective at genuine teaching rather than just providing information. This research is crucial for educators considering AI tools in their classrooms, as it provides evidence-based guidance on which AI systems can truly support student learning versus those that might simply generate impressive-sounding but ineffective responses.

Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial to evaluate a web-based comprehensive sexual health and media literacy education programme for high school students View study ↗

16 citations

T. Scull et al. (2020)

This study examines how combining sexual health education with media literacy skills helps high school students critically evaluate the unrealistic and often harmful messages they encounter about relationships and sexuality online. The web-based programme teaches students to question and analyse media representations while receiving medically accurate health information. This approach is particularly valuable for teachers because it addresses the reality that students are already consuming media about these topics and gives them tools to be critical consumers rather than passive recipients of potentially misleading information.

Building a Critical Thinking Generation: Developing an Innovative History Learning Model View study ↗

1 citations

Abrar Abrar et al. (2025)

Researchers developed new history teaching materials that combine concept mastery with creative problem-solving to help students think critically about historical narratives, especially important in an era when misinformation about historical events spreads rapidly on social media. The study shows that when students learn to analyse historical sources and consider multiple perspectives, they develop stronger critical thinking skills that transfer to evaluating contemporary information. History teachers can use this research to design lessons that not only teach historical content but also equip students with the analytical tools they need to navigate today's complex information landscape.

Using Argumentation to Develop Critical Thinking About Social Issues in the Classroom View study ↗

2 citations

N. L. Boyd (2021)

This research demonstrates how structured classroom debates and discussions help students develop critical thinking skills about controversial social issues in our polarized political climate. The study shows that when students engage in dialogic argumentation, where they must listen to different viewpoints and construct evidence-based responses, they become better at analysing complex issues objectively. Teachers across subjects can use these argumentation techniques to create classroom environments where students learn to engage respectfully with different perspectives while developing the analytical skills necessary for informed citizenship.

Teaching students to identify objective news sources starts with establishing clear evaluation criteria they can apply to any article or outlet. Educators need practical frameworks that help learners distinguish between credible journalism and biased content, whilst developing the critical thinking skills to navigate today's complex media landscape. The most effective approach combines teaching source verification techniques with hands-on practise using current examples. However, there's one fundamental skill that transforms how students consume news forever, yet most teachers never explicitly teach it.

This article aims to provoke student reflection, discussion and action concerning the use of propaganda and other forms of misinformation that deliberately distort perceptions of events and promote discord between and across communities. Although the context is the war in Ukraine, the questions and ideas pre sen ted are also offered as a catalyst for creating a better and more peaceful world by securing a more trustworthy media for us all.

Introduction:

“If you believe in something, you must think or talk or write and must act.”

(Alex Peterson, as cited in IBO, 2010)

Students and teachers around the world are currently discussing the pretext for the conflict in Ukraine and seeking ways to help mitigate against the effects of this war on the region and beyond. The kindness, generosity, and collegiality shown by many individuals, groups and governments have been a model for student action, and we should be gratified by the those who are united in caring for displaced people and ending this war. Schools will need to provide long term support for the wellbeing of the child refugees while helping them to learn. Beyond this, we must examine the causes of such conflict and take whatever steps we can, to prevent such wars from happening in the future.

Through the lens of this conflict, we clearly see that there are leaders today who consciously manipulate and restrict information to distort our perceptions of their actions and to provoke mistrust, discord, and violence. Although social media has made it easier for ‘citizen journalists’ to counter propaganda, this war demonstrates that our modern media and communication technologies also facilitate and embolden those who wish to cascade mistruths.

This misuse of information poses a clear and present danger to our peace, security, and general happiness. We must therefore seek to understand and minimise its affects in connection with all other Global Issues that require our action (Brown, 2022). As with all complex and challenging international issues we will need the ingenuity and support of peoples across the globe to secure and execute the most effective and effective strategies (Matic and Matic, 2022).

Educators have a key role to play in raising awareness of such issues. Thus, this article contains questions, background information, and suggestions, that teachers can use to provoke student reflection, debate, and action. To start this process a non-fiction account of a conversation is used to highlight just one of the many related challenges that we face connected with the misuse and manipulation of information.

Students resist changing their perceptions because misinformation often comes from trusted sources within their social or family networks. Cognitive dissonance makes it psychologically uncomfortable for students to accept information that contradicts their existing beliefs. Traditional critical thinking approaches fail against modern propaganda techniques that are specifically designed to bypass rational analysis.

“Does she really need to leave the country? The army will soon be there to help. They will stop the Ukrainian Nazis from attacking other Ukrainians.” (7 March 2022)

These are the words of a parent of a school leader in South America who has just called to discuss his ‘dilemma’. For weeks he has become more and more concerned for the safety of his relatives living in the Ukraine. He is particularly worried for his cousin who is caring for her one-year-old daughter, and her father who has a brain tumor.

Today, this colleague happily informed me that not only had his cousin and daughter made it to Warsaw but in “thirty minutes” they would be landing safely in a more northerly European city. I asked him if they had a place to live. He said,

“This is the problem. My cousin and daughter are to stay with one of my parents, who has been watching only state media from a country nearby. This parent has no idea about the dreadful situation in Ukraine and cannot understand why my cousin has had to leave. Although, I have tried explaining some of the details, I have not had much luck penetrating my parent’s current understanding. I think the planned living arrangements are not going to work.”

There are others who share this perspective of the war, and many more who have developed ‘alternative versions of reality’ in relation to other world events and issues.

Internationally minded educators must accept that people from other cultures will have different views, opinions, and attitudes, but this does not mean we have to accept relativistic truth, in which any idea, however unjustified, is to be deemed as having merit. While teachers must always aim to be objective, and must carefully respect cultural differences, we have a responsibility to help our students to construct versions of reality that correct for fal sel y manufactured realities. In short “There is no point in [the teacher] being more mature if…” we are not going to use that insight to help students construct truth (Dewey, 1958).

As my colleague discovered during his conversations within his parent, it can be rather difficult to change someone’s views. McGee (2017) explains that if one “…holds a false belief and faces a competing true belief, the strain of cognitive dissonance may cause them to prefer retaining their existing false belief over re writing their belief system.” It is easy to understand why changing the perspective of this pa rent would therefore be so difficult, as it might require the parent to re-examine the high levels of trust they have placed on the media and government. We concluded that although it was important to try, it was unlikely this parent would change their views quickly.

In the end, my colleague decided that his cousin and her daughter should live with him and his family in South America. He flew this week to that northern city to pick them up.

Modern information systems create echo chambers where misinformation spreads faster than verified facts, making truth appear tribal rather than objective. Social media algorithms amplify sensational and divisive content while suppressing nuanced, factual reporting. The democratization of publishing means propaganda now appears alongside legitimate journalism without clear distinctions for students.

My colleague and I wondered what educators could be doing, to help lessen the impact of propaganda and other false narratives placed in the public domain.

US Supreme Court Justice, Oliver Wendell Holmes (1919), stated that “The best test of truth is the power of the thought to get itself accepted in the competition of the market…”.

His definition of truth has two key prerequisites:

Unfortunately, we seem unable to meet either of these two requirements. We must first have access to information. Although in principle the UDHR affords us this freedom, unfortunately there are many governments today that regularly restrict access. Even in more democratic regions, where access should be freely available, the rise of populist movements, hinders free access by permitting only one perspective to dominate. In populist politics it appears that truth becomes that which is:

Populists, typically rely on a single source for their news. In this way, they eliminate the possibility of any cognitive dissonance, and instead feel emboldened and comforted by hearing the echoing voices of their own strongly held beliefs (Brooks, 2020).

Even if people are made aware of more thanone competing narrative, there must be a general willingness to evaluate them to make an informed judgement. Unfortunately, once a ‘first truth’ has been accepted, we seem very unwilling to consider alternatives, even if the original idea is shown later to be illogical, dangerous, or contrary to our supposed values.[1]

As McGee (2017) suggests, one of the reasons for this is that it may require us to abandon a deeper set of beliefs.

Today, truth seems to have become tribal (Brooks, 2020). People will take a political stance and then no matter what perspective the leaders from their selected political group may proffer, they will support it, for fear of having to abandon their deep-rooted belief in their politics.

Even if the tribal nature of our politics did not exist, our modern world offers fewer opportunities for critically reflection. Within our world of, tweets and short text messages, and without deep conversations at the dinner table, there seems to be far less opportunity to reflect deeply on issues, our values and to evaluate political positions.

In short, the marketplace envisaged by Justice Holmes no longer seems to exist for establishing verifiable truth. Consequently, we risk furthering and deepening already entrenched positions, exacerbating disharmony, and making it easier for conflicts both within and across communities to take root.

The passage from Justice Holmes (1919) goes on to say that this marketplace definition of truth, although a basis for the American Constitution, “… is an experiment, as all life is an experiment”. We have had over thirty years of this experiment and we must either find an alternative model for truth or find a way for people to be afforded sources for news which are more professionally and ethically produced.

Students should practise evaluating competing narratives by analysing the propaganda tactics used in different sources covering the same event. Cross-referencing information across multiple international news sources helps students identify bias and verify facts independently. Role-playing exercises where students create and identify propaganda help them recognise manipulation techniques in real media.

The following are a few suggestions to be used as a catalyst for discussions within and outside our school communities. The overall aim of our discussions and actions should be to ensure for a better and more peaceful world by reflecting on the problems connected with our modern media, communication, and truth.

Think pair share thinking routine" width="auto" height="auto" id="">

Think pair share thinking routine" width="auto" height="auto" id="">

Misinformation creates invisible barriers to learning that many teachers don't recognise until it's too late. When students arrive in class with pre-formed misconceptions from unreliable sources, they often struggle to engage with factual content, even when presented with evidence. This cognitive resistance isn't stubbornness; it's a natural psychological response called confirmation bias, where students unconsciously filter new information through their existing beliefs.

Research by Wineburg and McGrew (2019) reveals that students who regularly consume misinformation show decreased ability to evaluate source credibility over time. More concerning, these students often display overconfidence in their analytical skills whilst performing poorly on fact-checking tasks. In practical terms, this means a student who reads conspiracy theories about climate change may dismiss scientific evidence in geography lessons, not because they lack intelligence, but because misinformation has rewired their approach to evaluating truth.

The classroom impact extends beyond individual subjects. Students exposed to misinformation often struggle with:

Teachers can spot these effects through simple observation. Watch for students who cite "everyone knows" as evidence, refuse to acknowledge uncertainty in complex topics, or become defensive when sources are questioned. These behaviours signal that misinformation has already shaped their learning approach.

Most importantly, misinformation creates what psychologists term "epistemic closure", where students stop questioning information that confirms their beliefs. This closure transforms classrooms from spaces of inquiry into echo chambers, undermining the very foundation of education: the ability to think critically and adapt understanding based on evidence.

When students encounter information that contradicts their existing beliefs, their brains often work against accepting the correction. This psychological resistance, known as the backfire effect, can actually strengthen their original misconceptions when confronted with factual evidence. Understanding these barriers helps educators develop more effective approaches to teaching media literacy and critical evaluation skills.

Social identity plays a powerful role in how students process information. When a piece of misinformation aligns with their peer group's beliefs or family values, rejecting it feels like betraying their community. For instance, a student whose family strongly supports a particular political viewpoint may dismiss credible news sources that challenge that perspective, labelling them as 'biased' without examining the evidence. This tribal thinking intensifies during controversial events, making classroom discussions about current affairs particularly challenging.

Teachers can address these barriers through structured activities that reduce defensive reactions. One effective strategy involves asking students to argue for positions they disagree with, helping them understand how different perspectives form. Another approach uses anonymous belief surveys before and after examining evidence, allowing students to change their minds without losing face. When discussing the Ukraine conflict, for example, teachers might present historical timelines from multiple sources, asking students to identify differences without immediately judging which is 'correct'.

Research by Lewandowsky et al. (2012) suggests that successful correction requires replacing the misinformation with a clear, simple alternative explanation. Rather than simply debunking false claims, teachers should help students construct new mental models that explain events more accurately. This process takes time and repetition, but ultimately builds stronger critical thinking skills than traditional fact-checking exercises alone.

Teaching students to evaluate news sources requires hands-on practise with real-world examples. Rather than lecturing about bias and credibility, effective educators create opportunities for students to actively investigate and compare different media outlets themselves.

One powerful activity involves the 'Same Story, Different Angles' exercise. Present students with coverage of the same news event from three different sources: a tabloid, a broadsheet, and an international outlet. Ask students to identify specific differences in language choice, quoted sources, and which facts are emphasised or omitted. For instance, comparing how The Sun, The Guardian, and Al Jazeera report on the same political protest reveals stark contrasts in framing. Students quickly recognise how word choices like 'protesters' versus 'rioters' shape reader perception.

Another effective approach is the 'Source Detective' challenge. Provide students with a sensational news claim and task them with tracing it back to its original source. They must document each step: who first reported it, what evidence was provided, and how the story changed as other outlets repeated it. This exercise, based on Stanford University's research on lateral reading, teaches students to verify claims by checking multiple sources rather than diving deeper into a single article.

The 'Bias Spectrum' activity helps students move beyond binary thinking about media objectivity. Create a physical line in your classroom representing a spectrum from 'highly biased' to 'relatively objective'. Give students various news excerpts and ask them to physically position themselves along the spectrum based on their assessment. The ensuing discussions about why students chose different positions naturally leads to deeper understanding of how personal perspectives influence our perception of bias.

These activities transform abstract concepts about media literacy into concrete skills students can apply immediately. By practising source evaluation in a structured environment, students develop the confidence to question and verify information independently.

When presented with evidence that contradicts their beliefs, students often double down rather than reconsider. This resistance isn't stubbornness; it's a predictable psychological response that teachers must understand to effectively combat misinformation. Research shows that confirmation bias, the tendency to seek information supporting existing beliefs whilst ignoring contradictory evidence, intensifies during adolescence when identity formation peaks.

The backfire effect presents another challenge in the classroom. When students encounter fact-checks that challenge their worldview, they may actually strengthen their original beliefs. This occurs particularly when the misinformation aligns with their social group's values or family perspectives. For instance, a student who believes a false narrative about climate change shared by trusted family members may reject scientific evidence presented in lessons, viewing it as an attack on their identity rather than an educational opportunity.

Teachers can address these barriers through specific strategies. First, the "stealth correction" approach works effectively: present correct information without explicitly labelling the misconception as wrong. When discussing controversial topics, begin with areas of agreement before introducing conflicting evidence. Second, use the "consider the source" exercise where students examine the same event reported by five different outlets, identifying emotional language and missing context before revealing which sources are considered most reliable.

Social media algorithms compound these biases by creating filter bubbles that reinforce existing beliefs. Students rarely realise their feeds show curated content designed to maximise engagement, not accuracy. A practical classroom activity involves students swapping phones to examine each other's news feeds, revealing how different their information ecosystems have become. This visceral demonstration often proves more powerful than abstract discussions about media bias.

Teaching students to evaluate news sources requires structured activities that move beyond theoretical discussion. The most effective lessons combine immediate practise with real-world examples, allowing students to develop their analytical skills through direct experience rather than passive instruction.

One particularly effective activity is the 'Source Detective' exercise. Provide students with three articles covering the same news event: one from a reputable outlet, one from a partisan source, and one containing clear misinformation. Working in pairs, students identify specific language choices, missing context, and verification methods used in each piece. This comparative analysis helps learners recognise bias patterns whilst building confidence in their judgement. Teachers can extend this by having students create a 'reliability rubric' based on their findings, which they then test against new articles.

Another powerful approach involves reverse engineering news stories. Give students a factual event, then task them with writing two versions: one following journalistic standards and another incorporating propaganda techniques. This creative exercise demonstrates how easily facts can be manipulated through selective emphasis, emotional language, or strategic omissions. Research by Wineburg (2018) shows that students who create biased content themselves become significantly better at detecting it in authentic sources.

The 'verification relay' transforms fact-checking into an engaging group activity. Teams race to verify claims from social media posts using lateral reading techniques; students must find three independent sources confirming or debunking each claim. This gamified approach teaches practical skills whilst highlighting how quickly misinformation spreads compared to the time needed for proper verification. Teachers report that students begin applying these techniques spontaneously to content they encounter outside lessons, suggesting genuine skill transfer rather than surface-level compliance.

Teachers should present students with contrasting news reports about the same event from different countries or political perspectives. Students can research how the same story is covered across various media outlets to identify propaganda techniques and bias. These debates should focus on analysing media tactics rather than defending political positions, helping students separate truth from manipulation.

Section A: Take a Stand

The Project Zero Thinking Routine, ‘ Take a Stand’can be used with the following examples to initiate deep discussions of issues related to this article. The Educators Guide provides other age-appropriate ideas that can be used directly or refined to better align with our focus on misinformation and the media.

Further Questions:

(Further reading: The Spycatcher case)

Further Questions:

Does such polarisaton within our media insight violence? Should, TV programmes provide opportunities for extreme voices to be heard? Would it make any difference in your answer if there is an opportunity for a lengthy formalized debate or just a short commentary of views on mainstream media? Should we allow racists, holocaust deniers, and others to present their views? Are there groups/individuals that should not be offered airtime? Why/Whynot? Where do you draw the line?

Schools should implement media literacy programmes that go beyond traditional critical thinking to address modern propaganda techniques. Training teachers to recognise and discuss misinformation helps create a school-wide culture of factual inquiry. Partnering with international schools allows students to compare how the same events are reported in different countries and media systems.

a) Create an exhibition, production, performance, or competition that showcases the work of Artists, Choreographers, Poets, Writers, and Directors to help us to reflect on the dangers of propaganda, nationalism, populism, and/or xenophobia.

b) Create a lesson within your Art, Drama, Literature, History or PSE class which will similarly help us to reflect on these dangers.

The quote by Alec Peterson at the start of this article recognises that there are times when me must act. ‘While we may start by having opportunities to think, to write and to reflect, educators across the globe have a duty to help us take the necessary steps which will lead to a better and more peaceful world. We must therefore initiate conversations connected with the misuse, manipulation, and control of our modern media.

This issue should be the keynote topic for educational conferences once COVID restrictions have ended.

Academic research on misinformation, cognitive bias, and propaganda techniques provides the foundation for effective media literacy education. Studies on student perception formation and resistance to belief change inform teaching strategies that actually work. International educational frameworks and case studies offer practical approaches for implementing anti-misinformation curricula in schools.

Abrams v. United States, 250 U.S. 616 (1919)

Aljazera (2022), ‘Russia’s parliament approves jail for ‘fake’ war reports’ [Online] Available at:

Https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/3/4/russia-prison-media-law-fake-reports-ukraine-war(Accessed 15 March 20220)

Bath University (2020), ‘How tribalism polarized the Brexit social media debate’[Online] Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g1mTHswNaAw (Accessed 15 March 2022)

BBC (2008) ‘World War II Behind Closed Doors: Stalin, the Nazis and the West, Video Documentary, Laurence Reese and Andrew Williams

Brandies, L. (1913), ‘What Publicity Can Do’ , Harper’s Weekly, 20 December 1913, [Online] Available at: http://3197d6d14b5f19f2f4405e13d-29c4c016cf96cbbfd197c-579b45.r81.cf1.rackcdn.com/collection/papers/1910/1913_12_20_What_Publicity_Ca.pdf(Accessed 8 March 2022)

Brooks, M. (2020), ‘Here's Why Tribalism Trumps Truth: We like to think that we are reasonable, but our politics show otherwise.’, Psychology Today, [Online] Available at:https://thinkingmuseum.com/2021/03/17/how-to-use-zoom-in-thinking-routine-in-art-discussions/(Accessed 14 March 2022)

Brown, K. (2022), ‘5 GLOBAL ISSUES TO WATCH IN 2022, United Nations Foundation, [Online] Available at: https://unfoundation.org/blog/post/5-global-issues-to-watch-in-2022/(Accessed 14 March 2022)

Common Sense Education, ‘Take a Stand: Educator Guide’, Harvard University, Project Zero, Online] Available at: http://www.pz.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/Take%20a%-20Stand%20-%20Educator%20Guide.pdf(15 March 2022)Dewey, J. (1954).

Experience and education (The Kappa Delta Pi lecture series)New York: Macmillan. P. 23

Gordon, R. (2015), ‘The Fight that Changed Political TV Forever: Half a century ago, William Buckley and Gore Vidal brilliantly castigated each other on air. It’s been downhill ever since’, Politico magazine, [Online] Available at: https://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2015/08/04/william-buckley-gore-vidal-debates-1968-121009/ (Accessed 14 March 2022)

Harvard Graduate School of Education (2021) ‘Digital dilemmas Thinking Routine, Take a Stand -Resources’, Project Zero, [Online] Available at: http://www.pz.harvard.edu/resources/take-a-stand (Accessed 15 March 2022)

IBO (2010), ‘Creativity, action, service guide’, Peterson House, Malthouse Avenue, Cardiff Gate, Wales

IBO (2012), ‘International education: it’s time to think again: Teachers, and the IB, are going beyond flags and festivals, so how can educators create truly global teaching with a little uncommon thinking? [Online] Available at: https://www.ibo.org/ib-world-archive/september-2012/international-education-its-time-to-think-again/ (Accessed 15 March 2022)

Laurence, R (2008) ‘World War II Behind Closed Doors: Stalin, the Nazis and the West. Barnes & Nobles Publishing. ISBN 978-0-307-37730-2.

Matic, G. And Matic, A. (2022),’ Collective Innovation for Complex Challenges: Engaging With Meta-Cognitive Skills and Patterns’, In Achieving Sustainability Using Creativity, Innovation, and Education: A Multidisciplinary Approach (pp. 69-96). IGI Global.

McGee, D. (2017) ‘The ‘Marketplace of Ideas’ is a Failed Market’, [Online] Available at:https://medium.com/@danmcgee/the-marketplace-of-ideas-is-a-failed-market-5d1a7c106fb8 (Accessed 14 March 2022)

Morrissey L. (2017), ‘Alternative facts do exist: beliefs, lies and politics’, The Conversation [Online] Available at: https://theconversation.com/alternative-facts-do-exist-beliefs-lies-and-politics-84692(Accessed 14 March 2022)

Thinking Museum (2020), ‘How to use the Zoom in thinking routine in art lessons’, [Online] Available at: https://thinkingmuseum.com/2021/03/17/how-to-use-zoom-in-thinking-routine-in-art-discussions/(Accessed 14 March 2022)

[1]The ‘Zoom In’ thinking routine can get students used to the idea of having to adjust their hypoth esis with new information. See: Thinking Museum (2020) . There are many other useful thinking routines from Harvard’s Project Zero.

Misinformation is specifically designed to bypass rational analysis and often comes from trusted sources within students' social or family networks. Cognitive dissonance makes it psychologically uncomfortable for students to accept information that contradicts their existing beliefs, causing them to reject contradictory evidence even when presented with facts.

Teachers must remain objective and respect cultural differences whilst helping students construct versions of reality that correct for falsely manufactured narratives. The key is distinguishing between legitimate cultural perspectives and objectively false information, focusing on helping students develop skills to identify propaganda techniques rather than attacking their sources directly.

Teachers can use current conflicts like Ukraine as a lens to expose propaganda tactics and demonstrate how misinformation spreads through echo chambers. The article suggests using thinking routines like 'Circle of Viewpoints' to help students examine multiple perspectives whilst developing skills to identify when information sources are deliberately distorting perceptions.

Students develop tribal loyalty to information sources, which can override their critical thinking skills and create dangerous echo chambers. When misinformation aligns with their existing beliefs, cognitive dissonance prevents them from questioning these narratives, making them particularly vulnerable to propaganda from trusted sources.

Whilst social media has enabled 'citizen journalists' to counter propaganda, modern communication technologies also facilitate and embolden those who wish to spread mistruths. Social media algorithms amplify sensational and divisive content whilst suppressing nuanced, factual reporting, making it harder for students to distinguish between legitimate journalism and propaganda.

Educators have a key responsibility to raise awareness about misinformation and help students understand how it connects to broader global issues. Teachers should provoke student reflection, debate, and action by providing questions, background information, and strategies that help students recognise when information is being manipulated to promote discord between communities.

Schools must provide long-term support for the wellbeing of displaced students whilst examining the root causes of conflicts, including how leaders manipulate information to distort perceptions and provoke violence. This dual approach helps refugee students whilst educating all students about the dangers of propaganda and the importance of securing trustworthy media sources.

THE EFFECTS OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE TEACHING ENRICHED WITH DIGITAL APPLICATIONS ON TEACHER COGNITION AND STUDENT BELIEFS View study ↗

Aslıhan Arıkan & Dilek Peçenek (2024)

This large-scale study involving 49 teachers and 214 students across 35 cities examined how integrating digital applications into English language teaching affects both teacher thinking and student attitudes. The research provides valuable insights into the real-world impact of educational technology on classroom dynamics and learning mindsets. English teachers considering digital integration will benefit from understanding how technology adoption influences both their own teaching approach and their students' beliefs about language learning.

Revisiting the Three Basic Dimensions model: A critical empirical investigation of the indirect effects of student-perceived teaching quality on student outcomes View study ↗

15 citations

Ayşenur Alp Christ et al. (2024)

This research investigates how teaching quality actually translates into student achievement and interest in mathematics, examining the pathways through student engagement, time spent learning, and motivation. The study reveals which aspects of good teaching have the strongest indirect effects on student outcomes, going beyond surface-level measures. Mathematics teachers will gain evidence-based insights into how their instructional choices influence student success through multiple interconnected factors.

Encouraging Students' Creative Writing through Multimodal Strategies within a Linguistic Framework View study ↗

Dessy Wardiyah et al. (2025)

This classroom action research with 30 high school students shows how combining visual, auditory, and interactive media significantly enhanced creative writing abilities over two teaching cycles. The study demonstrates that engaging multiple senses and learning modalities helps students develop stronger imagination and linguistic expression in their writing. Writing teachers will discover practical multimodal strategies that can transform their creative writing instruction and boost student engagement.

Montessori and Contextual Teaching Learning Method for Beginning Reading Abilities View study ↗

Agustina Dewi Rakhmawati et al. (2025)

This research addresses common early reading challenges like letter recognition difficulties and low reading interest by combining Montessori principles with contextual teaching methods in kindergarten settings. The study specifically focuses on helping children who struggle with distinguishing similar symbols and connecting sounds to written forms. Early childhood educators will find valuable strategies for supporting young learners with reading difficulties through structured, meaningful learning experiences.

These peer-reviewed studies provide the research foundation for the strategies discussed in this article:

BEAM Me Up: Teaching Rhetorical Methods for Source Use and Synthesis View study ↗

3 citations

Ashley Roach-Freiman (2021)

This research introduces the BEAM framework, which helps students understand why authors use different sources by categorizing them based on the author's purpose, whether to provide background, evidence, argument, or method. Rather than just teaching students to evaluate whether sources are good or bad, this approach teaches them to think critically about how and why sources are being used in different contexts. Teachers can use this framework to help students become more sophisticated readers who understand the strategic choices authors make when incorporating sources into their work.

EducationQ: Evaluating LLMs' Teaching Capabilities Through Multi-Agent Dialogue Framework View study ↗

9 citations

Yao Shi et al. (2025)

Researchers developed a new system to test how well artificial intelligence tools can actually teach students by creating simulated classroom conversations between AI teachers, students, and evaluators. The study tested 14 different AI systems to see which ones were most effective at genuine teaching rather than just providing information. This research is crucial for educators considering AI tools in their classrooms, as it provides evidence-based guidance on which AI systems can truly support student learning versus those that might simply generate impressive-sounding but ineffective responses.

Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial to evaluate a web-based comprehensive sexual health and media literacy education programme for high school students View study ↗

16 citations

T. Scull et al. (2020)

This study examines how combining sexual health education with media literacy skills helps high school students critically evaluate the unrealistic and often harmful messages they encounter about relationships and sexuality online. The web-based programme teaches students to question and analyse media representations while receiving medically accurate health information. This approach is particularly valuable for teachers because it addresses the reality that students are already consuming media about these topics and gives them tools to be critical consumers rather than passive recipients of potentially misleading information.

Building a Critical Thinking Generation: Developing an Innovative History Learning Model View study ↗

1 citations

Abrar Abrar et al. (2025)

Researchers developed new history teaching materials that combine concept mastery with creative problem-solving to help students think critically about historical narratives, especially important in an era when misinformation about historical events spreads rapidly on social media. The study shows that when students learn to analyse historical sources and consider multiple perspectives, they develop stronger critical thinking skills that transfer to evaluating contemporary information. History teachers can use this research to design lessons that not only teach historical content but also equip students with the analytical tools they need to navigate today's complex information landscape.

Using Argumentation to Develop Critical Thinking About Social Issues in the Classroom View study ↗

2 citations

N. L. Boyd (2021)

This research demonstrates how structured classroom debates and discussions help students develop critical thinking skills about controversial social issues in our polarized political climate. The study shows that when students engage in dialogic argumentation, where they must listen to different viewpoints and construct evidence-based responses, they become better at analysing complex issues objectively. Teachers across subjects can use these argumentation techniques to create classroom environments where students learn to engage respectfully with different perspectives while developing the analytical skills necessary for informed citizenship.