Supporting Dyslexic Students: Practical Strategies for

Discover effective strategies for supporting dyslexic students. Learn practical classroom adjustments and interventions that help learners with...

Discover effective strategies for supporting dyslexic students. Learn practical classroom adjustments and interventions that help learners with...

Dyslexia is a neurological learning difference that primarily affects reading and spelling abilities, occurring in approximately 10% of students regardless of intelligence level. It results from differences in how the brain processes written language, particularly in identifying and manipulating sounds within words (phonological processing). Students with dyslexia often have average or above-average cognitive abilities but struggle with decoding written text.

Dyslexia is a specific learning difficulty that primarily affects reading and spelling. It is neurological in origin, meaning it results from differences in how the brain processes written language. Dyslexia occurs across the range of intellectual abilities and is independent of socioeconomic background.

The Rose Report (2009) defined dyslexia as characterised by difficulties with accurate and fluent word reading and spelling, with these difficulties typically resulting from a deficit in the phonological component of language. This means students with dyslexia often struggle to identify and manipulate the sounds within words, which is the foundation of decoding written text.

Dyslexia is common, affecting approximately 10% of the population to some degree, with 4% experiencing severe difficulties. This means that in a typical class of 30 students, three are likely to have dyslexic characteristics, and one may have significant difficulties. It's worth noting that dyslexia can co-occur with other conditions, making ADHD assessments sometimes relevant for comprehensive support.

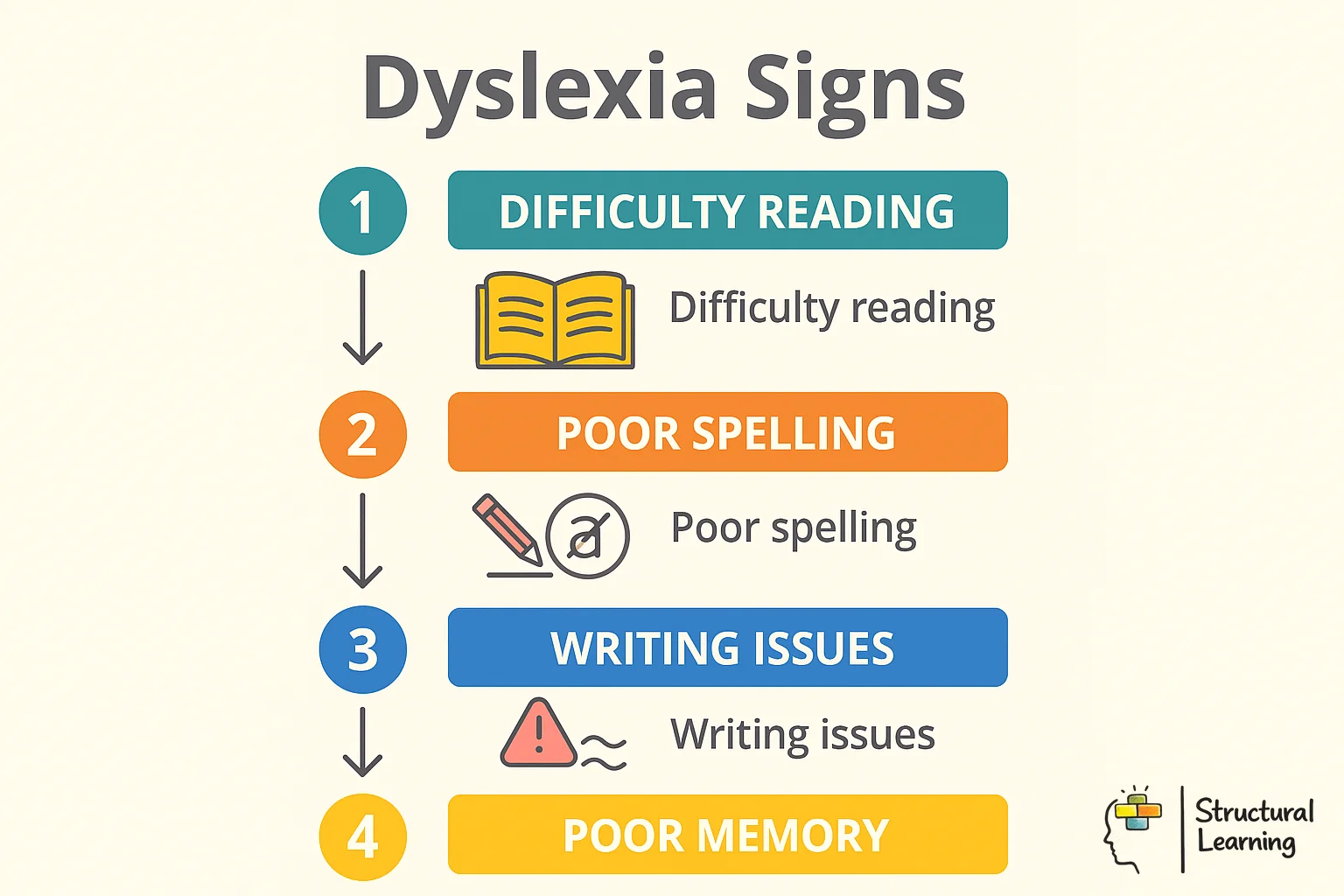

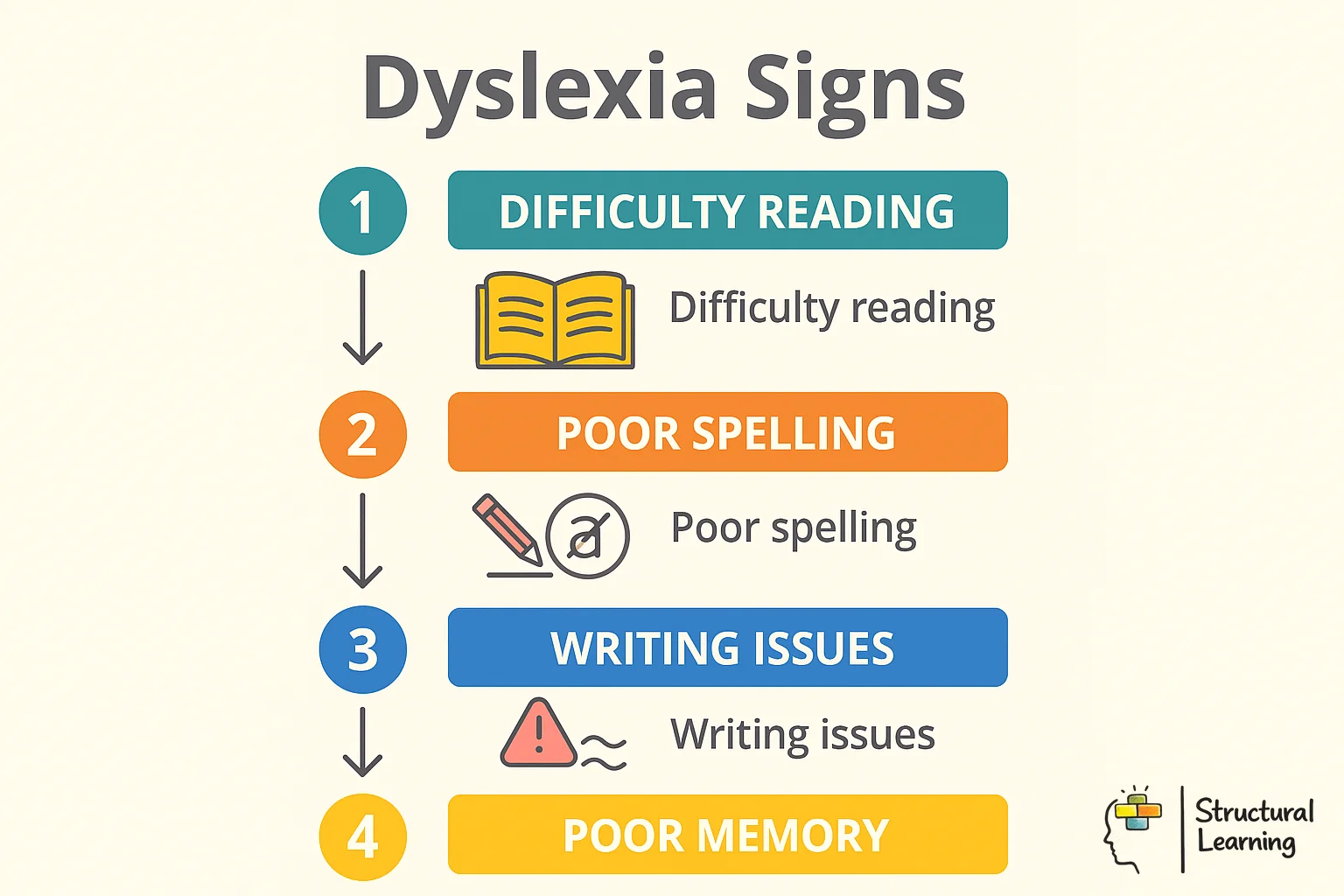

Early signs may include difficulty learning nursery rhymes, trouble recognising rhyming patterns, delayed speech development, difficulty learning letter names and sounds, and confusion with similar-looking letters (b/d, p/q). Children may also struggle to remember sequences such as days of the week.

As reading demands increase, difficulties become more apparent. Signs include slow reading progress despite good teaching, phonological difficulties (sounding out words, blending sounds), spelling that does not improve with practice, reading that is effortful and error-prone, and avoidance of reading aloud. Working memory difficulties may affect following multi-step instructions. The cumulative effect of these challenges can significantly impact student wellbeing and academic confidence.

By secondary school, some students may have developed coping strategies that mask their difficulties, but others may experience frustration, low self-esteem, and social and emotional challenges as a result of ongoing academic struggles.udents may have developed compensatory strategies, but difficulties often persist. Signs include slow reading speed affecting exam completion, continued spelling difficulties, trouble taking notes while listening, difficulty with foreign language learning, and discrepancy between verbal ability and written work.

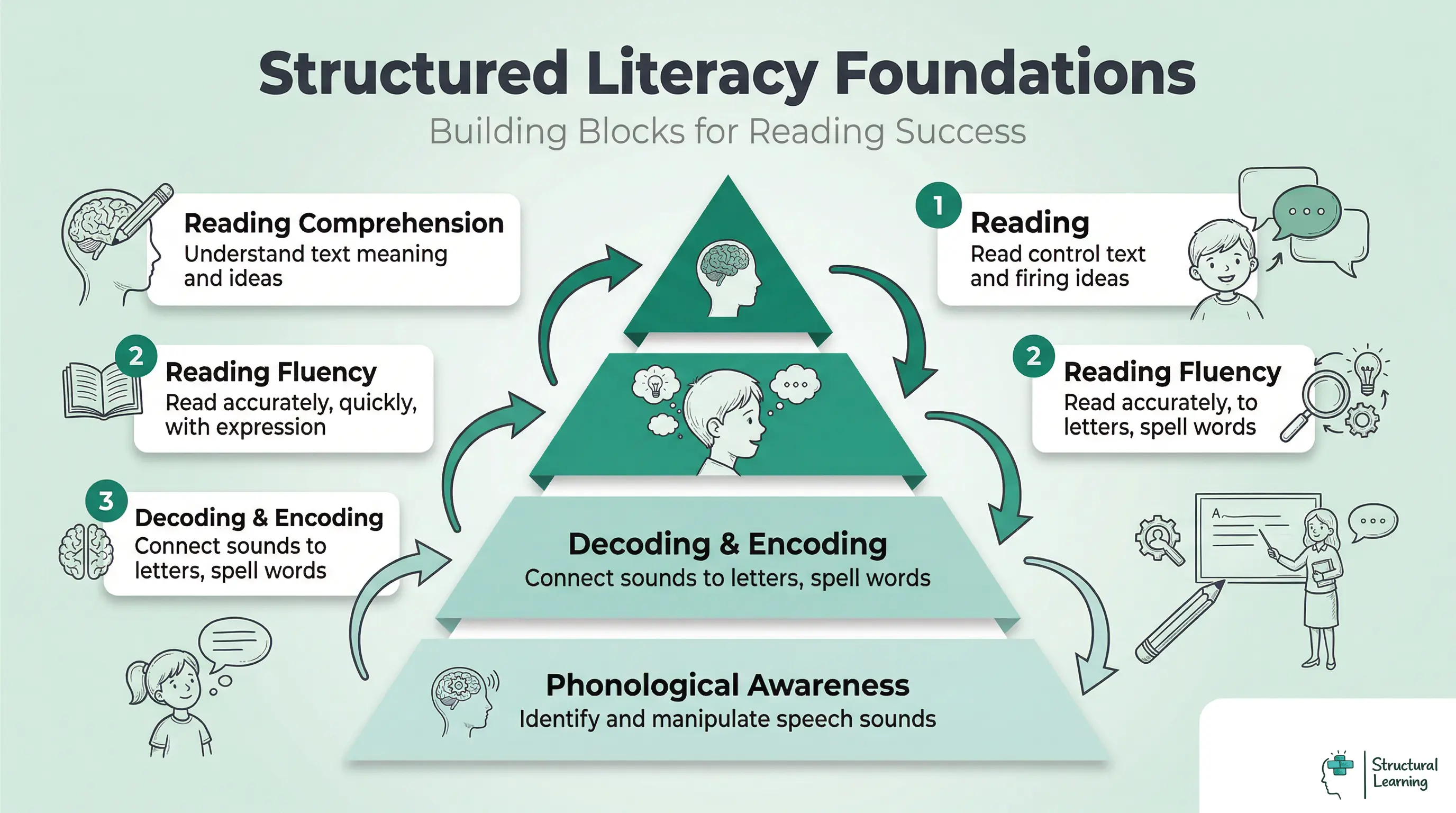

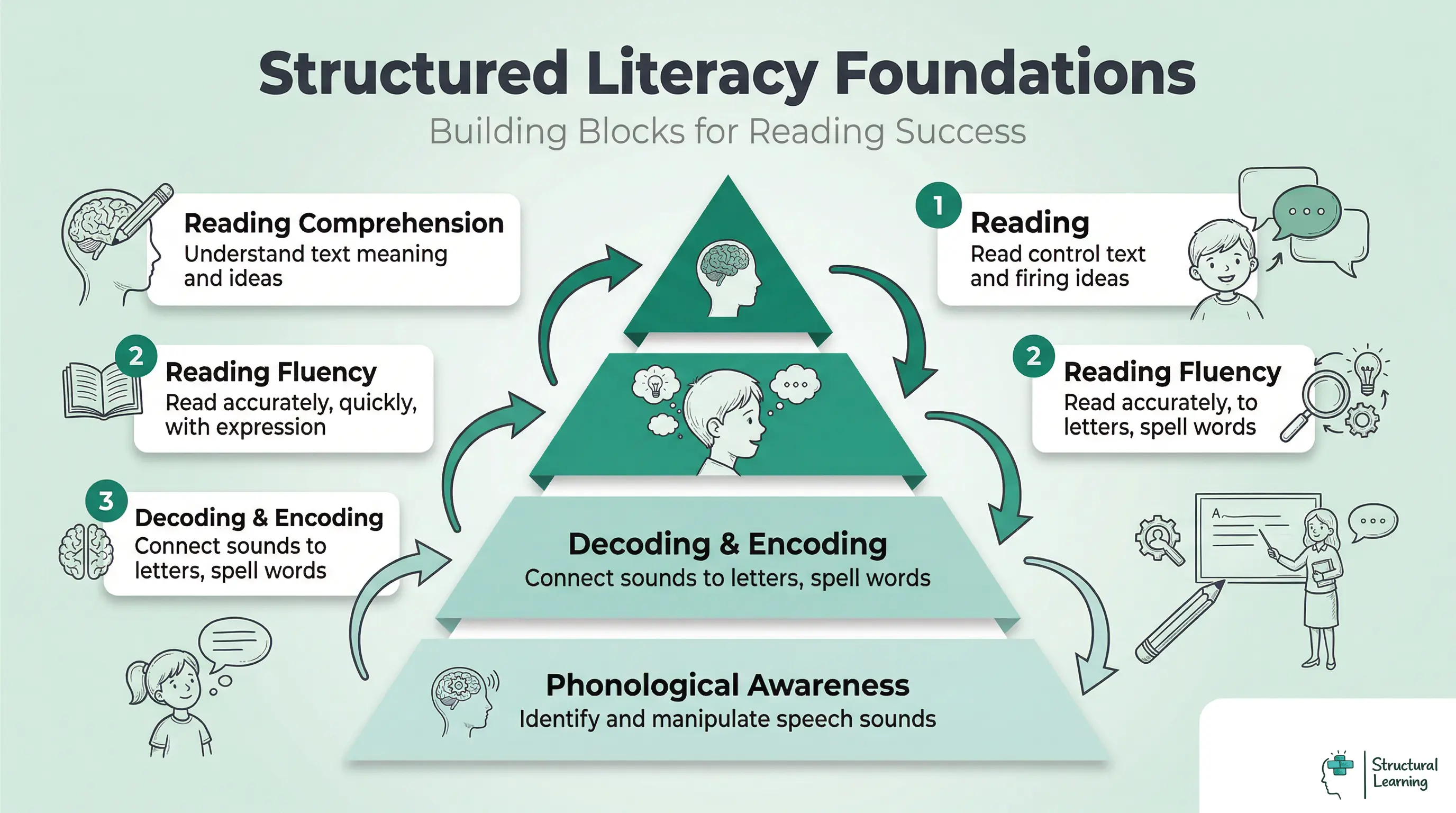

Research consistently supports structured, explicit, and systematic phonics instruction for students with dyslexia. Programmes should be multisensory, engaging visual, auditory, and kinaesthetic pathways simultaneously. Effective instruction follows a logical sequence, moving from simple to complex, and provides extensive practice opportunities.

Multisensory approaches engage multiple senses simultaneously. This might include tracing letters in sand while saying the sound (visual, kinaesthetic, auditory), using colour-coded syllables, or building words with physical letter tiles. The additional sensory channels strengthen memory and provide multiple pathways for retrieval.

Students with dyslexia often need more repetition to achieve automaticity than their peers. Skills that are not automatic consume working memory capacity, leaving less available for comprehension. Distributed practice over time is more effective than massed practice for building lasting automaticity.

Classroom adjustments can make an immediate difference to dyslexic students' learning experience. Simple modifications such as providing reading materials in larger fonts, offering extended time for written tasks, and allowing verbal responses instead of written answers help level the playing field. Colour-coding systems for different subjects or concepts also support organisation and memory retention, whilst mind mapping techniques enable students to structure their thoughts visually before writing.

Technology integration offers powerful support when used strategically. Text-to-speech software allows dyslexic students to access complex texts at their intellectual level, whilst speech-to-text programmes help overcome barriers to written expression. Digital highlighting tools and note-taking applications provide organisational support that traditional methods often cannot match. However, these technological aids should complement, not replace, fundamental literacy instruction.

Creating an inclusive classroom environment requires ongoing assessment and flexible grouping strategies. Regular formative assessment helps teachers identify specific areas where individual students need additiona l support, allowing for targeted intervention. Peer support systems, where dyslexic students work alongside confident readers, build both academic skills and self-confidence whilst developing understanding among all students.

Key adjustments include providing extra time for reading and writing tasks, offering alternative ways to demonstrate knowledge such as oral presentations, and using assistive technology like text-to-speech software. Teachers should also provide written instructions alongside verbal ones and allow students to use colored overlays or specific fonts. These adjustments enable dyslexic students to show their true capabilities without being hindered by their processing differences.

| Area | Adjustments |

|---|---|

| Reading | Audio versions of texts, reduced reading load, pre-teaching vocabulary, paired reading, reading pens |

| Writing | Extra time, word processing, speech-to-text software, reduced copying from board, alternative recording methods |

| Focus on key spellings, use of mnemonics, access to spell checkers, multi-sensory strategies | |

| Organisation | Checklists, colour-coding, graphic organisers, breaking tasks into smaller steps |

| Assessments | Extra time, quiet room, use of technology, alternative formats (oral, practical) |

Physical classroom adjustments can significantly impact dyslexic students' learning experience. Position these students away from distracting elements like high-traffic areas or noisy equipment. Ensure excellent lighting on their workspace and provide a clear view of the whiteboard. Consider offering alternative seating options, such as stability balls or standing desks, which can help some dyslexic learners focus better.

Instructional adjustments are equally important for creating an inclusive teaching environment. Break complex instructions into smaller, sequential steps and provide both verbal and written directions simultaneously. Allow extra processing time for questions and responses - research by Patricia Bowers shows that dyslexic students often need additional time to retrieve information, even when they know the answer. Implement a structured approach by offering choices in how students demonstrate their knowledge, such as oral presentations instead of written reports, or mind maps rather than traditional essays. Multi-sensory teaching methods prove particularly effective - combine visual, auditory, and kinaesthetic elements when introducing new concepts.

Environmental modifications should include reducing visual clutter on walls and handouts whilst maintaining an engaging learning space. Use consistent fonts like Arial or Comic Sans MS in 12-point size or larger, and ensure adequate spacing between lines. Provide coloured overlays or paper, as some dyslexic students find these reduce visual stress and improve reading fluency. Create designated quiet spaces where students can retreat when feeling overwhelmed by sensory input, and establish clear routines that provide predictability and reduce anxiety around classroom transitions.

Assistive technology can be a breakthrough for students with dyslexia, helping to bypass areas of difficulty and promote independence. Some commonly used tools include:

Providing training and support in the use of assistive technology is crucial to ensure that students can effectively utilise these tools to enhance their learning experience.

A dyslexia-friendly classroom benefits all learners, not just those with dyslexia. Key elements include:

By implementing these strategies, teachers can create an inclusive classroom where all students can thrive, regardless of their learning differences.

Physical classroom adjustments play a crucial role in supporting dyslexic students. Position these learners away from distractions such as high-traffic areas or noisy equipment, and ensure good lighting on their workspace. Use cream or off-white paper instead of bright white, as this reduces visual stress for many dyslexic students. Display key information using dyslexia-friendly fonts like Arial or Comic Sans in 12-point size or larger, and maintain consistent colour coding for different subjects or types of information.

Incorporate structured, multi-sensory teaching approaches throughout your daily practice. When introducing new vocabulary, combine visual displays with verbal explanations and kinaesthetic activities. Break complex instructions into smaller, sequential steps and provide visual checklists that students can tick off as they progress. Use mind maps and flow charts to present information graphically, making abstract concepts more concrete and memorable for dyslexic learners.

Technology integration can significantly enhance accessibility without singling out individual students. Provide access to text-to-speech software, audio books, and speech-to-text programmes for all pupils. Encourage the use of tablets or laptops for written work when handwriting presents barriers. These evidence-based classroom adjustments create an inclusive environment where dyslexic students can demonstrate their knowledge and abilities effectively whilst developing essential literacy skills through appropriately supported practice.

Effective parent-teacher partnerships form the cornerstone of successful support for dyslexic students, requiring clear communication and shared understanding of each child's unique needs. Research by Sally Shaywitz demonstrates that consistent approaches between home and school significantly improve outcomes for students with dyslexia. Teachers should initiate regular dialogue with families, moving beyond traditional parent evenings to establish ongoing communication channels that allow for immediate feedback and collaborative problem-solving.

When communicating with parents, focus on strengths-based discussions that highlight what their child can do, alongside honest conversations about areas requiring support. Share specific classroom adjustments you've implemented, such as extended processing time or multi-sensory teaching methods, and explain how parents can reinforce these strategies at home. Provide families with practical resources, including recommended reading programmes and guidance on creating supportive homework environments that reduce cognitive load without compromising learning expectations.

Establish structured review meetings to assess progress and adjust support strategies collaboratively. Encourage parents to share insights about their child's learning preferences, emotional responses to reading tasks, and successful strategies used at home. This two-way exchange of information ensures that both classroom interventions and home support remain responsive to the student's evolving needs, creating a smooth support network that maximises learning potential across all environments.

Traditional assessment methods often fail to accurately reflect the true capabilities of dyslexic students, creating barriers that mask their understanding rather than revealing it. Fair evaluation requires separating what we're assessing from how we're assessing it, ensuring that reading and writing difficulties don't overshadow subject knowledge. Research by Margaret Snowling demonstrates that dyslexic learners frequently possess strong reasoning abilities that remain hidden when assessments rely heavily on text-based formats.

Effective assessment modifications include offering alternative formats such as oral examinations, visual presentations, or practical demonstrations alongside written work. Extended time allocations, typically 25-50% additional time, allow dyslexic students to process information at their natural pace without compromising quality. Consider providing questions in advance, using larger fonts, offering coloured paper, or allowing the use of assistive technology. These adjustments level the playing field rather than lowering standards, enabling students to demonstrate their genuine understanding through their preferred learning channels.

When marking work, focus evaluation criteria on content knowledge and conceptual understanding rather than penalising spelling or grammatical errors unless these are the specific learning objectives. Implement rubrics that clearly separate technical accuracy from subject comprehension, and provide detailed feedback highlighting strengths alongside areas for development. This approach ensures that assessment becomes a tool for learning rather than a barrier to achievement.

Supporting the emotional wellbeing of dyslexic students requires deliberate classroom strategies that build confidence whilst addressing the anxiety many experience around literacy tasks. Research by Kirk and Reid demonstrates that dyslexic learners often develop negative self-perceptions about their academic abilities, leading to avoidance behaviours and reduced classroom participation. Teachers must recognise that emotional support is not separate from academic instruction but forms an integral part of effective dyslexia intervention.

Creating psychologically safe learning environments involves celebrating diverse strengths and reframing challenges as learning differences rather than deficits. Implement regular opportunities for dyslexic students to showcase their abilities in areas such as creative thinking, problem-solving, or visual-spatial tasks. Use process-focused praise rather than ability-focused comments, highlighting effort and strategy use rather than innate talent. This approach, supported by Carol Dweck's research on growth mindset, helps students develop resilience and persistence when facing literacy challenges.

Practical classroom adjustments include providing advance notice of reading tasks, offering alternative ways to demonstrate knowledge, and establishing clear routines that reduce cognitive load. Consider peer support systems where dyslexic students can mentor others in their areas of strength, developing positive self-identity. Regular check-ins about emotional responses to learning tasks enable early intervention when anxiety levels rise, ensuring that social and emotional needs receive equal priority alongside academic progress.

Supporting students with dyslexia requires a multi-faceted approach that encompasses early identification, evidence-based instruction, classroom adjustments, and assistive technology. By understanding the nature of dyslexia and implementing effective strategies, educators can helps students to overcome their challenges and achieve their full potential.

Remember that every student with dyslexia is unique, and their needs may vary. Regular communication with parents, specialists, and the students themselves is essential to ensure that they receive the appropriate support and accommodations. A collaborative and understanding approach can make a significant difference in the lives of students with dyslexia, developing their academic success and overall wellbeing.

Supporting dyslexic students effectively requires a combination of understanding, practical strategies, and ongoing commitment to inclusive teaching practices. The approaches outlined in this guide - from multi-sensory teaching methods to assistive technology integration - work best when implemented consistently across the school environment. Remember that each dyslexic learner is unique, with individual strengths and challenges that may require personalised adjustments to these general strategies.

Start small when implementing these classroom adjustments. Focus on one or two evidence-based strategies initially, such as providing handouts in dyslexia-friendly fonts or allowing extra processing time for oral responses. Once these become routine, gradually introduce additional multi-sensory approaches like colour-coding systems for different subjects or incorporating movement into spelling practice. This structured approach prevents overwhelm whilst building your confidence in supporting dyslexic students effectively.

Regular monitoring and flexibility remain essential throughout this process. What works well in autumn term may need adjustment by spring as students develop and curriculum demands change. Keep simple records of which practical strategies prove most effective for individual students, and don't hesitate to modify approaches based on student feedback and observed outcomes.

The investment in dyslexia-friendly teaching practices benefits not only students with dyslexia but enhances learning for all students in your classroom. As you implement these strategies, maintain regular communication with students, parents, and support staff to ensure approaches remain effective and responsive to changing needs. With proper support and understanding, dyslexic students can achieve academic success whilst developing the confidence and resilience that will serve them throughout their educational journey.

Dyslexia is a neurological learning difference that primarily impacts reading, spelling and phonological processing. It is independent of intelligence, meaning students often have average or above average cognitive abilities despite struggling with written language. In a classroom setting, it often appears as slow reading speed or difficulty following multi step instructions.

Teachers implement multisensory strategies by engaging visual, auditory and kinaesthetic pathways simultaneously during lessons. This includes activities like tracing letter shapes in sand while saying the sound aloud or using colour coded tiles to build words. These techniques strengthen memory and provide multiple routes for students to retrieve information.

Evidence from the Rose Report and wider educational research consistently supports explicit, systematic and structured phonics instruction. This approach moves logically from simple to complex sounds, ensuring students build a firm foundation before progressing. Regular overlearning and distributed practice are essential components for developing reading automaticity over time.

Strategic use of technology allows students to access complex texts that match their intellectual level through text to speech software. It helps remove barriers to written expression, enabling learners to demonstrate their true knowledge without being held back by spelling or handwriting difficulties. Digital tools also support organisation through visual mind mapping and note taking applications.

A frequent error is assuming that dyslexia is linked to lower intelligence or a lack of effort from the student. Another mistake is relying solely on simplified work rather than providing reasonable adjustments that allow the child to access the full curriculum. Overlooking the social and emotional impact of literacy struggles can also lead to decreased confidence and wellbeing.

Dyslexia is not a reflection of intelligence and occurs across the full range of intellectual abilities. Most students with dyslexia have average or above average cognitive skills; their difficulties are specific to phonological processing and word recognition. Recognising this discrepancy is vital for ensuring that teaching focuses on removing barriers rather than lowering expectations.

Elliott, J. G., & Grigorenko, E. L. (2014). The dyslexia debate. Cambridge University Press.

Lyon, G. R., Shaywitz, S. E., & Shaywitz, B. A. (2003). A definition of dyslexia. Annals of dyslexia, 53(1), 1-14.

Peterson, R. L., & Kelley, K. R. (2021). The complete guide to dyslexia: Symptoms, diagnosis, and treatments. John Wiley & Sons.

Snowling, M. J. (2020). Dyslexia (2nd ed.): A very short introduction. Oxford University Press.

Dyslexia is a neurological learning difference that primarily affects reading and spelling abilities, occurring in approximately 10% of students regardless of intelligence level. It results from differences in how the brain processes written language, particularly in identifying and manipulating sounds within words (phonological processing). Students with dyslexia often have average or above-average cognitive abilities but struggle with decoding written text.

Dyslexia is a specific learning difficulty that primarily affects reading and spelling. It is neurological in origin, meaning it results from differences in how the brain processes written language. Dyslexia occurs across the range of intellectual abilities and is independent of socioeconomic background.

The Rose Report (2009) defined dyslexia as characterised by difficulties with accurate and fluent word reading and spelling, with these difficulties typically resulting from a deficit in the phonological component of language. This means students with dyslexia often struggle to identify and manipulate the sounds within words, which is the foundation of decoding written text.

Dyslexia is common, affecting approximately 10% of the population to some degree, with 4% experiencing severe difficulties. This means that in a typical class of 30 students, three are likely to have dyslexic characteristics, and one may have significant difficulties. It's worth noting that dyslexia can co-occur with other conditions, making ADHD assessments sometimes relevant for comprehensive support.

Early signs may include difficulty learning nursery rhymes, trouble recognising rhyming patterns, delayed speech development, difficulty learning letter names and sounds, and confusion with similar-looking letters (b/d, p/q). Children may also struggle to remember sequences such as days of the week.

As reading demands increase, difficulties become more apparent. Signs include slow reading progress despite good teaching, phonological difficulties (sounding out words, blending sounds), spelling that does not improve with practice, reading that is effortful and error-prone, and avoidance of reading aloud. Working memory difficulties may affect following multi-step instructions. The cumulative effect of these challenges can significantly impact student wellbeing and academic confidence.

By secondary school, some students may have developed coping strategies that mask their difficulties, but others may experience frustration, low self-esteem, and social and emotional challenges as a result of ongoing academic struggles.udents may have developed compensatory strategies, but difficulties often persist. Signs include slow reading speed affecting exam completion, continued spelling difficulties, trouble taking notes while listening, difficulty with foreign language learning, and discrepancy between verbal ability and written work.

Research consistently supports structured, explicit, and systematic phonics instruction for students with dyslexia. Programmes should be multisensory, engaging visual, auditory, and kinaesthetic pathways simultaneously. Effective instruction follows a logical sequence, moving from simple to complex, and provides extensive practice opportunities.

Multisensory approaches engage multiple senses simultaneously. This might include tracing letters in sand while saying the sound (visual, kinaesthetic, auditory), using colour-coded syllables, or building words with physical letter tiles. The additional sensory channels strengthen memory and provide multiple pathways for retrieval.

Students with dyslexia often need more repetition to achieve automaticity than their peers. Skills that are not automatic consume working memory capacity, leaving less available for comprehension. Distributed practice over time is more effective than massed practice for building lasting automaticity.

Classroom adjustments can make an immediate difference to dyslexic students' learning experience. Simple modifications such as providing reading materials in larger fonts, offering extended time for written tasks, and allowing verbal responses instead of written answers help level the playing field. Colour-coding systems for different subjects or concepts also support organisation and memory retention, whilst mind mapping techniques enable students to structure their thoughts visually before writing.

Technology integration offers powerful support when used strategically. Text-to-speech software allows dyslexic students to access complex texts at their intellectual level, whilst speech-to-text programmes help overcome barriers to written expression. Digital highlighting tools and note-taking applications provide organisational support that traditional methods often cannot match. However, these technological aids should complement, not replace, fundamental literacy instruction.

Creating an inclusive classroom environment requires ongoing assessment and flexible grouping strategies. Regular formative assessment helps teachers identify specific areas where individual students need additiona l support, allowing for targeted intervention. Peer support systems, where dyslexic students work alongside confident readers, build both academic skills and self-confidence whilst developing understanding among all students.

Key adjustments include providing extra time for reading and writing tasks, offering alternative ways to demonstrate knowledge such as oral presentations, and using assistive technology like text-to-speech software. Teachers should also provide written instructions alongside verbal ones and allow students to use colored overlays or specific fonts. These adjustments enable dyslexic students to show their true capabilities without being hindered by their processing differences.

| Area | Adjustments |

|---|---|

| Reading | Audio versions of texts, reduced reading load, pre-teaching vocabulary, paired reading, reading pens |

| Writing | Extra time, word processing, speech-to-text software, reduced copying from board, alternative recording methods |

| Focus on key spellings, use of mnemonics, access to spell checkers, multi-sensory strategies | |

| Organisation | Checklists, colour-coding, graphic organisers, breaking tasks into smaller steps |

| Assessments | Extra time, quiet room, use of technology, alternative formats (oral, practical) |

Physical classroom adjustments can significantly impact dyslexic students' learning experience. Position these students away from distracting elements like high-traffic areas or noisy equipment. Ensure excellent lighting on their workspace and provide a clear view of the whiteboard. Consider offering alternative seating options, such as stability balls or standing desks, which can help some dyslexic learners focus better.

Instructional adjustments are equally important for creating an inclusive teaching environment. Break complex instructions into smaller, sequential steps and provide both verbal and written directions simultaneously. Allow extra processing time for questions and responses - research by Patricia Bowers shows that dyslexic students often need additional time to retrieve information, even when they know the answer. Implement a structured approach by offering choices in how students demonstrate their knowledge, such as oral presentations instead of written reports, or mind maps rather than traditional essays. Multi-sensory teaching methods prove particularly effective - combine visual, auditory, and kinaesthetic elements when introducing new concepts.

Environmental modifications should include reducing visual clutter on walls and handouts whilst maintaining an engaging learning space. Use consistent fonts like Arial or Comic Sans MS in 12-point size or larger, and ensure adequate spacing between lines. Provide coloured overlays or paper, as some dyslexic students find these reduce visual stress and improve reading fluency. Create designated quiet spaces where students can retreat when feeling overwhelmed by sensory input, and establish clear routines that provide predictability and reduce anxiety around classroom transitions.

Assistive technology can be a breakthrough for students with dyslexia, helping to bypass areas of difficulty and promote independence. Some commonly used tools include:

Providing training and support in the use of assistive technology is crucial to ensure that students can effectively utilise these tools to enhance their learning experience.

A dyslexia-friendly classroom benefits all learners, not just those with dyslexia. Key elements include:

By implementing these strategies, teachers can create an inclusive classroom where all students can thrive, regardless of their learning differences.

Physical classroom adjustments play a crucial role in supporting dyslexic students. Position these learners away from distractions such as high-traffic areas or noisy equipment, and ensure good lighting on their workspace. Use cream or off-white paper instead of bright white, as this reduces visual stress for many dyslexic students. Display key information using dyslexia-friendly fonts like Arial or Comic Sans in 12-point size or larger, and maintain consistent colour coding for different subjects or types of information.

Incorporate structured, multi-sensory teaching approaches throughout your daily practice. When introducing new vocabulary, combine visual displays with verbal explanations and kinaesthetic activities. Break complex instructions into smaller, sequential steps and provide visual checklists that students can tick off as they progress. Use mind maps and flow charts to present information graphically, making abstract concepts more concrete and memorable for dyslexic learners.

Technology integration can significantly enhance accessibility without singling out individual students. Provide access to text-to-speech software, audio books, and speech-to-text programmes for all pupils. Encourage the use of tablets or laptops for written work when handwriting presents barriers. These evidence-based classroom adjustments create an inclusive environment where dyslexic students can demonstrate their knowledge and abilities effectively whilst developing essential literacy skills through appropriately supported practice.

Effective parent-teacher partnerships form the cornerstone of successful support for dyslexic students, requiring clear communication and shared understanding of each child's unique needs. Research by Sally Shaywitz demonstrates that consistent approaches between home and school significantly improve outcomes for students with dyslexia. Teachers should initiate regular dialogue with families, moving beyond traditional parent evenings to establish ongoing communication channels that allow for immediate feedback and collaborative problem-solving.

When communicating with parents, focus on strengths-based discussions that highlight what their child can do, alongside honest conversations about areas requiring support. Share specific classroom adjustments you've implemented, such as extended processing time or multi-sensory teaching methods, and explain how parents can reinforce these strategies at home. Provide families with practical resources, including recommended reading programmes and guidance on creating supportive homework environments that reduce cognitive load without compromising learning expectations.

Establish structured review meetings to assess progress and adjust support strategies collaboratively. Encourage parents to share insights about their child's learning preferences, emotional responses to reading tasks, and successful strategies used at home. This two-way exchange of information ensures that both classroom interventions and home support remain responsive to the student's evolving needs, creating a smooth support network that maximises learning potential across all environments.

Traditional assessment methods often fail to accurately reflect the true capabilities of dyslexic students, creating barriers that mask their understanding rather than revealing it. Fair evaluation requires separating what we're assessing from how we're assessing it, ensuring that reading and writing difficulties don't overshadow subject knowledge. Research by Margaret Snowling demonstrates that dyslexic learners frequently possess strong reasoning abilities that remain hidden when assessments rely heavily on text-based formats.

Effective assessment modifications include offering alternative formats such as oral examinations, visual presentations, or practical demonstrations alongside written work. Extended time allocations, typically 25-50% additional time, allow dyslexic students to process information at their natural pace without compromising quality. Consider providing questions in advance, using larger fonts, offering coloured paper, or allowing the use of assistive technology. These adjustments level the playing field rather than lowering standards, enabling students to demonstrate their genuine understanding through their preferred learning channels.

When marking work, focus evaluation criteria on content knowledge and conceptual understanding rather than penalising spelling or grammatical errors unless these are the specific learning objectives. Implement rubrics that clearly separate technical accuracy from subject comprehension, and provide detailed feedback highlighting strengths alongside areas for development. This approach ensures that assessment becomes a tool for learning rather than a barrier to achievement.

Supporting the emotional wellbeing of dyslexic students requires deliberate classroom strategies that build confidence whilst addressing the anxiety many experience around literacy tasks. Research by Kirk and Reid demonstrates that dyslexic learners often develop negative self-perceptions about their academic abilities, leading to avoidance behaviours and reduced classroom participation. Teachers must recognise that emotional support is not separate from academic instruction but forms an integral part of effective dyslexia intervention.

Creating psychologically safe learning environments involves celebrating diverse strengths and reframing challenges as learning differences rather than deficits. Implement regular opportunities for dyslexic students to showcase their abilities in areas such as creative thinking, problem-solving, or visual-spatial tasks. Use process-focused praise rather than ability-focused comments, highlighting effort and strategy use rather than innate talent. This approach, supported by Carol Dweck's research on growth mindset, helps students develop resilience and persistence when facing literacy challenges.

Practical classroom adjustments include providing advance notice of reading tasks, offering alternative ways to demonstrate knowledge, and establishing clear routines that reduce cognitive load. Consider peer support systems where dyslexic students can mentor others in their areas of strength, developing positive self-identity. Regular check-ins about emotional responses to learning tasks enable early intervention when anxiety levels rise, ensuring that social and emotional needs receive equal priority alongside academic progress.

Supporting students with dyslexia requires a multi-faceted approach that encompasses early identification, evidence-based instruction, classroom adjustments, and assistive technology. By understanding the nature of dyslexia and implementing effective strategies, educators can helps students to overcome their challenges and achieve their full potential.

Remember that every student with dyslexia is unique, and their needs may vary. Regular communication with parents, specialists, and the students themselves is essential to ensure that they receive the appropriate support and accommodations. A collaborative and understanding approach can make a significant difference in the lives of students with dyslexia, developing their academic success and overall wellbeing.

Supporting dyslexic students effectively requires a combination of understanding, practical strategies, and ongoing commitment to inclusive teaching practices. The approaches outlined in this guide - from multi-sensory teaching methods to assistive technology integration - work best when implemented consistently across the school environment. Remember that each dyslexic learner is unique, with individual strengths and challenges that may require personalised adjustments to these general strategies.

Start small when implementing these classroom adjustments. Focus on one or two evidence-based strategies initially, such as providing handouts in dyslexia-friendly fonts or allowing extra processing time for oral responses. Once these become routine, gradually introduce additional multi-sensory approaches like colour-coding systems for different subjects or incorporating movement into spelling practice. This structured approach prevents overwhelm whilst building your confidence in supporting dyslexic students effectively.

Regular monitoring and flexibility remain essential throughout this process. What works well in autumn term may need adjustment by spring as students develop and curriculum demands change. Keep simple records of which practical strategies prove most effective for individual students, and don't hesitate to modify approaches based on student feedback and observed outcomes.

The investment in dyslexia-friendly teaching practices benefits not only students with dyslexia but enhances learning for all students in your classroom. As you implement these strategies, maintain regular communication with students, parents, and support staff to ensure approaches remain effective and responsive to changing needs. With proper support and understanding, dyslexic students can achieve academic success whilst developing the confidence and resilience that will serve them throughout their educational journey.

Dyslexia is a neurological learning difference that primarily impacts reading, spelling and phonological processing. It is independent of intelligence, meaning students often have average or above average cognitive abilities despite struggling with written language. In a classroom setting, it often appears as slow reading speed or difficulty following multi step instructions.

Teachers implement multisensory strategies by engaging visual, auditory and kinaesthetic pathways simultaneously during lessons. This includes activities like tracing letter shapes in sand while saying the sound aloud or using colour coded tiles to build words. These techniques strengthen memory and provide multiple routes for students to retrieve information.

Evidence from the Rose Report and wider educational research consistently supports explicit, systematic and structured phonics instruction. This approach moves logically from simple to complex sounds, ensuring students build a firm foundation before progressing. Regular overlearning and distributed practice are essential components for developing reading automaticity over time.

Strategic use of technology allows students to access complex texts that match their intellectual level through text to speech software. It helps remove barriers to written expression, enabling learners to demonstrate their true knowledge without being held back by spelling or handwriting difficulties. Digital tools also support organisation through visual mind mapping and note taking applications.

A frequent error is assuming that dyslexia is linked to lower intelligence or a lack of effort from the student. Another mistake is relying solely on simplified work rather than providing reasonable adjustments that allow the child to access the full curriculum. Overlooking the social and emotional impact of literacy struggles can also lead to decreased confidence and wellbeing.

Dyslexia is not a reflection of intelligence and occurs across the full range of intellectual abilities. Most students with dyslexia have average or above average cognitive skills; their difficulties are specific to phonological processing and word recognition. Recognising this discrepancy is vital for ensuring that teaching focuses on removing barriers rather than lowering expectations.

Elliott, J. G., & Grigorenko, E. L. (2014). The dyslexia debate. Cambridge University Press.

Lyon, G. R., Shaywitz, S. E., & Shaywitz, B. A. (2003). A definition of dyslexia. Annals of dyslexia, 53(1), 1-14.

Peterson, R. L., & Kelley, K. R. (2021). The complete guide to dyslexia: Symptoms, diagnosis, and treatments. John Wiley & Sons.

Snowling, M. J. (2020). Dyslexia (2nd ed.): A very short introduction. Oxford University Press.

<script type="application/ld+json">{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/supporting-students-with-dyslexia#article","headline":"Supporting Dyslexic Students: Practical Strategies for","description":"Discover effective strategies for supporting dyslexic students. Learn practical classroom adjustments and interventions that help learners with dyslexia...","datePublished":"2022-04-27T10:16:39.552Z","dateModified":"2026-03-02T11:01:26.207Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/supporting-students-with-dyslexia"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/696a1449ef5ac7ba777a7321_696a1448c9a94861bad9b592_supporting-students-with-dyslexia-infographic.webp","wordCount":2723},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/supporting-students-with-dyslexia#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"Supporting Dyslexic Students: Practical Strategies for","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/supporting-students-with-dyslexia"}]},{"@type":"FAQPage","mainEntity":[{"@type":"Question","name":"What is dyslexia and how does it affect students in the classroom?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Dyslexia is a neurological learning difference that primarily impacts reading, spelling and phonological processing. It is independent of intelligence, meaning students often have average or above average cognitive abilities despite struggling with written language. In a classroom setting, it often appears as slow reading speed or difficulty following multi step instructions."}},{"@type":"Question","name":"How do teachers implement multisensory teaching strategies for dyslexia?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Teachers implement multisensory strategies by engaging visual, auditory and kinaesthetic pathways simultaneously during lessons. This includes activities like tracing letter shapes in sand while saying the sound aloud or using colour coded tiles to build words. These techniques strengthen memory and provide multiple routes for students to retrieve information."}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What does the research say about structured literacy for dyslexic learners?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Evidence from the Rose Report and wider educational research consistently supports explicit, systematic and structured phonics instruction. This approach moves logically from simple to complex sounds, ensuring students build a firm foundation before progressing. Regular overlearning and distributed practice are essential components for developing reading automaticity over time."}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What are the benefits of using assistive technology for students with dyslexia?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Strategic use of technology allows students to access complex texts that match their intellectual level through text to speech software. It helps remove barriers to written expression, enabling learners to demonstrate their true knowledge without being held back by spelling or handwriting difficulties. Digital tools also support organisation through visual mind mapping and note taking applications."}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What are common mistakes when supporting dyslexic students in schools?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"A frequent error is assuming that dyslexia is linked to lower intelligence or a lack of effort from the student. Another mistake is relying solely on simplified work rather than providing reasonable adjustments that allow the child to access the full curriculum. Overlooking the social and emotional impact of literacy struggles can also lead to decreased confidence and wellbeing."}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What does dyslexia mean for a student's cognitive ability and intelligence?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Dyslexia is not a reflection of intelligence and occurs across the full range of intellectual abilities. Most students with dyslexia have average or above average cognitive skills; their difficulties are specific to phonological processing and word recognition. Recognising this discrepancy is vital for ensuring that teaching focuses on removing barriers rather than lowering expectations."}}]}]}</script>