Schemas in Education: How Prior Knowledge Shapes New Learning

Examine how schemas shape learning and memory. Learn why activating prior knowledge is essential and how educators can effectively build and challenge.

Examine how schemas shape learning and memory. Learn why activating prior knowledge is essential and how educators can effectively build and challenge.

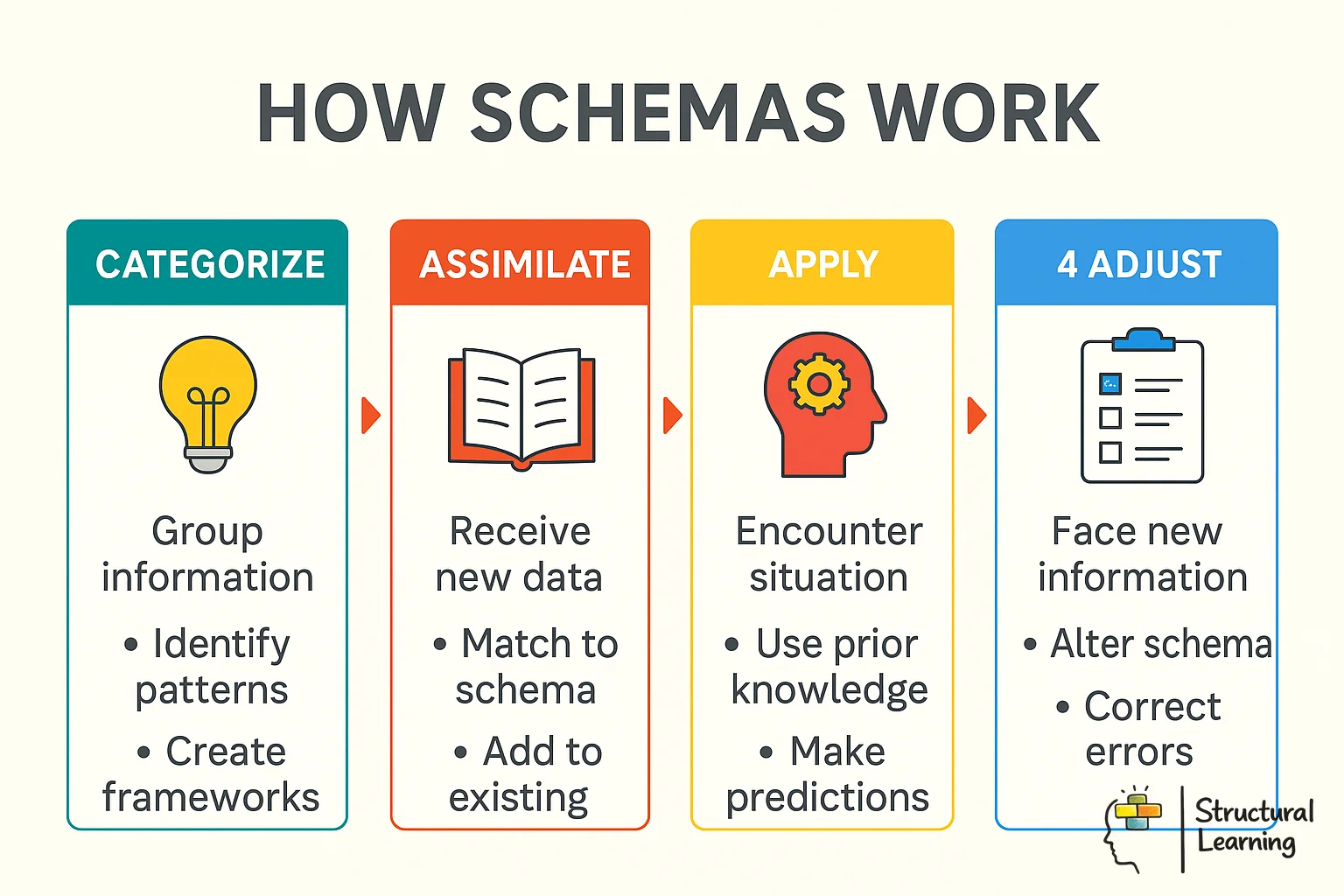

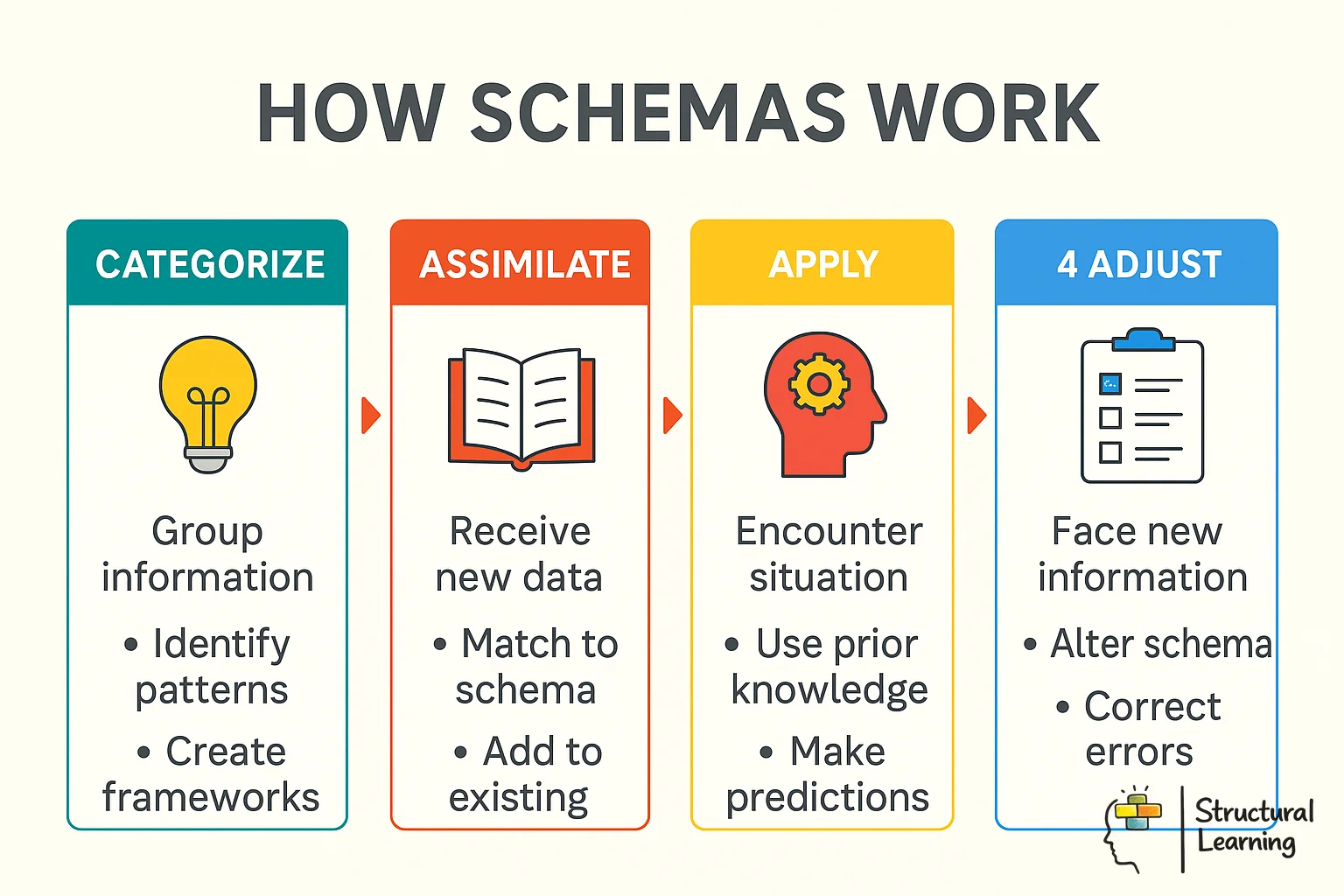

A schema is a mental framework that helps organise and interpret information. First described by psychologist Frederic Bartlett in 1932 and later developed by Jean Piaget and Vygotsky's theory, schema theory explains how we use existing knowledge to understand new experiences. When you hear th e word "restaurant," you automatically activate a schema that includes expectations about menus, ordering, eating, and paying, even if you have never been to that particular restaurant.

Schemas are not simply memories. They are active structures that shape how we perceive, interpret, and remember information through metacognitive awareness through the development of cognitive skills. A child who has developed a schema for "dogs" will use that framework when encountering a new dog, quickly recognising it as a dog and predicting its likely behaviours based on previous experience.

In educational contexts, schemas determine what students can learn and how easily they can learn it. A student with a rich schema for fractions will grasp ratio and proportion more readily than a student whose fraction schema is weak or absent.

| Schema Type | Definition | Example | Teaching Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Object Schemas | Mental representations of physical objects and their features | Schema for "chair" includes legs, seat, back, sitting function | Present clear exemplars and non-exemplars |

| Event Schemas (Scripts) | Knowledge about how events unfold in sequence | Restaurant script: enter, order, eat, pay, leave | Make classroom routines explicit |

| Social Schemas | Knowledge about social roles and expected behaviours | Schema for "teacher": knowledgeable, explains, assesses | Be aware of students' social expectations |

| Self-Schemas | Beliefs about oneself, including abilities and identity | "I am good at maths" or "I struggle with writing" | Develop growth-oriented self-schemas through feedback |

| Content Schemas | Domain-specific knowledge structures | Schema linking plants, sunlight, carbon dioxide for photosynthesis | Build on existing content schemas |

| Formal Schemas | Knowledge about text structures and genres | Persuasive essay: intro, arguments, counterarguments, conclusion | Teach genre conventions explicitly |

Based on Bartlett's schema theory (1932) and Piaget's cognitive development research.

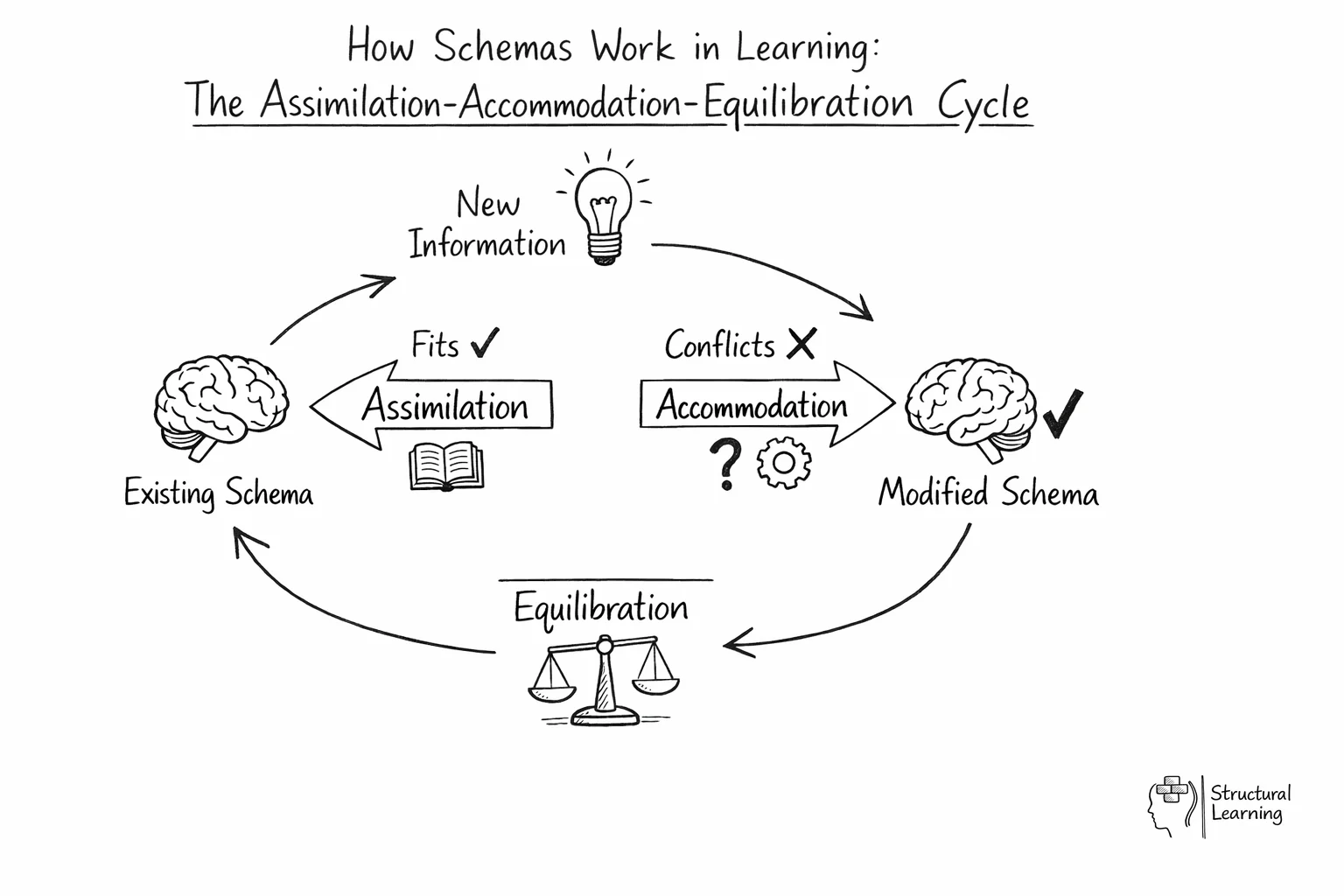

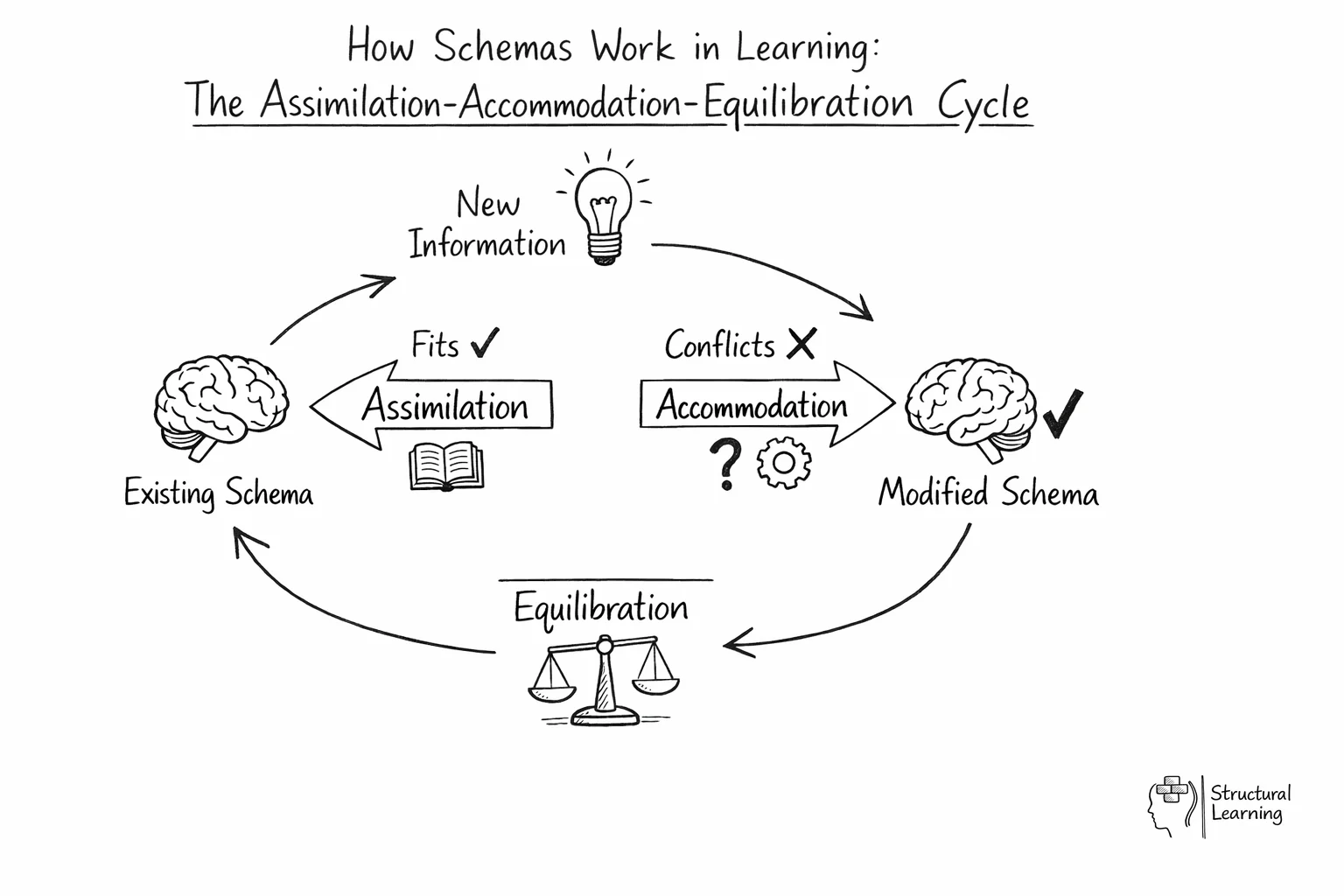

Assimilation occurs when new information fits easily into existing schemas. A child who knows about sparrows encounters a robin and adds it to their existing "bird" schema. The new information is incorporated without requiring fundamental changes to the underlying framework.

Accommodation happens when new information does not fit existing schemas, requiring modification of the schema itself. A child who believes all birds fly encounters a penguin. Their bird schema must accommodate this exception, becoming more sophisticated to include birds that cannot fly.

Equilibration is the process of balancing assimilation and accommodation. When students encounter information that challenges their existing schemas, developing metacognitive awareness helps them recognise and resolve these conflicts through equilibration. Their schemas, they experience cognitive discomfort (disequilibrium). Learning occurs as they work to restore balance by modifying their understanding.

Schema activation occurs through multiple pathways in the learning process. When students encounter new information, their brains automatically search for relevant existing knowledge structures to make connections. This process, known as 'schema matching', happens rapidly and often unconsciously, influencing how students interpret and store new learning.

The efficiency of schema activation depends largely on how well-organised and accessible a student's prior knowledge is. Well-developed schemas act like mental scaffolding, providing clear frameworks for understanding complex concepts. For instance, a student with a robust schema about narrative structure will more easily comprehend new stories, automatically recognising elements like setting, conflict, and resolution.

Teachers can observe schema activation in classroom practice through students' responses and misconceptions. When a student struggles to connect new information to their existing knowledge structures, learning becomes fragmented and difficult to retain. Conversely, when schema activation is successful, students demonstrate deeper understanding and can transfer knowledge to new contexts. Effective teaching strategies therefore focus on explicitly building and strengthening these cognitive frameworks before introducing complex new material.

Schemas are crucial for teaching because students with well-developed schemas in a subject area learn new related content significantly faster and more deeply than those starting from scratch. Teachers who understand schema theory can design lessons that activate prior knowledge before introducing new concepts, making learning more efficient and meaningful. This understanding also helps teachers identify why some students struggle with certain topics while others grasp them quickly.

Schema theory has profound implications for teaching practice. Understanding how schemas work explains several common classroom observations:

Why some students learn faster: Students with well-developed prior knowledge in a domain have schemas that help them organise and retain new information. What looks like natural ability is often extensive prior knowledge.

Why reading comprehension varies: A student can decode every word in a passage yet fail to understand it if they lack the background knowledge (schemas) the text assumes. Reading comprehension is as much about knowledge as about reading skills.

Why misconceptions persist: Incorrect schemas are still schemas. They actively shape how students interpret new information, often causing them to distort correct information to fit their existing (wrong) understanding.

Teachers can build student schemas by explicitly connecting new information to what students already know and providing multiple examples that highlight common patterns. Effective strategies include using graphic organisers, concept maps, and structured discussions that help students see relationships between ideas. Regular review and application of concepts in different contexts strengthens these mental frameworks over time.

| Strategy | How It Builds Schemas | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Activate prior knowledge | Prepares relevant schemas for new learning | "What do you already know about the Victorians?" |

| Use advance organisers | Provides a structural framework for new information | Outline of the lesson with the key points covered, before starting |

| Concept mapping | Visually represents relationships between concepts | Draw a mind map of WWII, with sub-topics branching out |

| Elaborative interrogation | Encourages students to explain why something is true | "Why do you think the character made that decision?" |

Effective schema building requires deliberate, systematic approaches that connect new learning to students' existing knowledge structures. Teachers can employ several proven strategies to strengthen student schemas and enhance classroom practice.

Strategic schema activation begins with diagnostic assessment of prior knowledge. Teachers should start lessons by asking probing questions about what students already know, using techniques like think-pair-share activities or concept mapping exercises. This reveals existing knowledge structures and identifies misconceptions that could interfere with new learning. For example, before teaching photosynthesis, a science teacher might ask students to draw and explain how they think plants obtain food, revealing whether students hold the common misconception that plants get nutrients solely from soil.

Building robust schemas also requires explicit connection-making throughout instruction. Teachers should regularly use phrases like "This is similar to.." or "Remember when we learned about.." to help students link new concepts to established knowledge structures. Analogies prove particularly powerful - comparing electrical circuits to water flowing through pipes, for instance, helps students build understanding by connecting abstract concepts to familiar experiences. Additionally, providing worked examples followed by guided practice allows students to see expert thinking patterns, gradually building their own organised knowledge structures for tackling similar problems independently.

These practical strategies help teachers activate, connect, and develop students' mental frameworks.

One of the biggest challenges in teaching is addressing misconceptions. These incorrect schemas can be incredibly resistant to change because they shape how students interpret new information. Simply presenting correct information is often not enough to dislodge a firmly held misconception. Instead, teachers must actively challenge these incorrect schemas.

Strategies for addressing misconceptions include:

Educational researchers have identified four primary types of schemas that significantly impact student learning in classroom settings. Content schemas encompass subject-specific knowledge structures, such as a student's understanding of mathematical operations or historical chronology. Formal schemas relate to text structures and organisational patterns, helping students navigate different genres and formats. Linguistic schemas involve language knowledge, including vocabulary, grammar, and syntax, whilst cultural schemas encompass the social and cultural knowledge students bring from their lived experiences.

Richard Anderson's research on reading comprehension demonstrates how these schema types work together to support learning. When students encounter new material, they simultaneously draw upon content knowledge, recognise textual patterns, process language structures, and interpret information through their cultural lens. Teachers who understand these interconnected schema types can better identify why students might struggle with particular concepts or texts.

Effective classroom practice involves strategically activating and building each schema type. For content schemas, teachers might use concept maps or knowledge webs to connect new information to existing understanding. To support formal schemas, explicit instruction in text structures helps students recognise patterns across different subjects. Building linguistic schemas through vocabulary pre-teaching and cultural schemas through inclusive examples ensures all students can access new learning through their existing knowledge structures.

Decades of cognitive science research have consistently demonstrated that schemas profoundly influence how students process and retain new information. Richard Anderson's seminal studies in the 1970s showed that students with relevant background knowledge could recall up to 40% more details from texts compared to those lacking schema connections. Similarly, John Sweller's cognitive load theory reveals that when students can connect new material to existing knowledge structures, their working memory is freed up to focus on deeper understanding rather than basic comprehension.

More recent research by cognitive scientist Daniel Willingham confirms that factual knowledge stored in long-term memory is the foundation of reading comprehension and critical thinking. His studies demonstrate that students cannot simply learn generic thinking skills in isolation; they need robust schemas within specific domains to think effectively. This finding challenges traditional approaches that prioritise skills over knowledge acquisition.

In classroom contexts, these research findings translate into clear teaching strategies. Teachers who systematically activate students' prior knowledge before introducing new concepts see measurably better learning outcomes. The key is helping students recognise connections between what they already know and new material, essentially building bridges between existing schemas and emerging knowledge structures.

Schemas are fundamental to how students learn. By understanding how schemas work, teachers can create more effective and engaging learning experiences. Activating prior knowledge, explicitly building connections between ideas, and addressing misconceptions are all key strategies for using the power of schemas in the classroom.

Ultimately, teaching is about helping students build rich, accurate, and flexible schemas. By focusing on schema development, educators can helps students to become lifelong learners who are able to make sense of the world around them.

The most powerful implication of schema theory lies in its emphasis on making learning connections explicit rather than assuming students will naturally see relationships between concepts. This requires teachers to regularly model their own thinking processes, showing students how new information relates to previously learned material. For instance, when introducing photosynthesis, effective teachers might explicitly connect it to students' existing schemas about breathing, food, and plant growth rather than presenting it as an isolated biological process.

Successfully implementing schema theory also demands that teachers become skilled diagnosticians of student understanding. This involves using formative assessment techniques that reveal what students know and how they organise that knowledge. Simple strategies such as concept mapping, think-alouds, or asking students to explain connections between topics can illuminate the structure of their schemas and highlight areas where misconceptions might be forming or where knowledge gaps need addressing.

Ultimately, schema theory reminds us that learning is fundamentally about transformation rather than accumulation. When teachers focus on helping students modify and expand their existing knowledge structures, rather than simply adding new facts, they create conditions for deeper understanding and more successful transfer of learning to new situations and contexts.

A schema is a mental framework that helps organise and interpret information. First described by psychologist Frederic Bartlett in 1932 and later developed by Jean Piaget and Vygotsky's theory, schema theory explains how we use existing knowledge to understand new experiences. When you hear th e word "restaurant," you automatically activate a schema that includes expectations about menus, ordering, eating, and paying, even if you have never been to that particular restaurant.

Schemas are not simply memories. They are active structures that shape how we perceive, interpret, and remember information through metacognitive awareness through the development of cognitive skills. A child who has developed a schema for "dogs" will use that framework when encountering a new dog, quickly recognising it as a dog and predicting its likely behaviours based on previous experience.

In educational contexts, schemas determine what students can learn and how easily they can learn it. A student with a rich schema for fractions will grasp ratio and proportion more readily than a student whose fraction schema is weak or absent.

| Schema Type | Definition | Example | Teaching Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Object Schemas | Mental representations of physical objects and their features | Schema for "chair" includes legs, seat, back, sitting function | Present clear exemplars and non-exemplars |

| Event Schemas (Scripts) | Knowledge about how events unfold in sequence | Restaurant script: enter, order, eat, pay, leave | Make classroom routines explicit |

| Social Schemas | Knowledge about social roles and expected behaviours | Schema for "teacher": knowledgeable, explains, assesses | Be aware of students' social expectations |

| Self-Schemas | Beliefs about oneself, including abilities and identity | "I am good at maths" or "I struggle with writing" | Develop growth-oriented self-schemas through feedback |

| Content Schemas | Domain-specific knowledge structures | Schema linking plants, sunlight, carbon dioxide for photosynthesis | Build on existing content schemas |

| Formal Schemas | Knowledge about text structures and genres | Persuasive essay: intro, arguments, counterarguments, conclusion | Teach genre conventions explicitly |

Based on Bartlett's schema theory (1932) and Piaget's cognitive development research.

Assimilation occurs when new information fits easily into existing schemas. A child who knows about sparrows encounters a robin and adds it to their existing "bird" schema. The new information is incorporated without requiring fundamental changes to the underlying framework.

Accommodation happens when new information does not fit existing schemas, requiring modification of the schema itself. A child who believes all birds fly encounters a penguin. Their bird schema must accommodate this exception, becoming more sophisticated to include birds that cannot fly.

Equilibration is the process of balancing assimilation and accommodation. When students encounter information that challenges their existing schemas, developing metacognitive awareness helps them recognise and resolve these conflicts through equilibration. Their schemas, they experience cognitive discomfort (disequilibrium). Learning occurs as they work to restore balance by modifying their understanding.

Schema activation occurs through multiple pathways in the learning process. When students encounter new information, their brains automatically search for relevant existing knowledge structures to make connections. This process, known as 'schema matching', happens rapidly and often unconsciously, influencing how students interpret and store new learning.

The efficiency of schema activation depends largely on how well-organised and accessible a student's prior knowledge is. Well-developed schemas act like mental scaffolding, providing clear frameworks for understanding complex concepts. For instance, a student with a robust schema about narrative structure will more easily comprehend new stories, automatically recognising elements like setting, conflict, and resolution.

Teachers can observe schema activation in classroom practice through students' responses and misconceptions. When a student struggles to connect new information to their existing knowledge structures, learning becomes fragmented and difficult to retain. Conversely, when schema activation is successful, students demonstrate deeper understanding and can transfer knowledge to new contexts. Effective teaching strategies therefore focus on explicitly building and strengthening these cognitive frameworks before introducing complex new material.

Schemas are crucial for teaching because students with well-developed schemas in a subject area learn new related content significantly faster and more deeply than those starting from scratch. Teachers who understand schema theory can design lessons that activate prior knowledge before introducing new concepts, making learning more efficient and meaningful. This understanding also helps teachers identify why some students struggle with certain topics while others grasp them quickly.

Schema theory has profound implications for teaching practice. Understanding how schemas work explains several common classroom observations:

Why some students learn faster: Students with well-developed prior knowledge in a domain have schemas that help them organise and retain new information. What looks like natural ability is often extensive prior knowledge.

Why reading comprehension varies: A student can decode every word in a passage yet fail to understand it if they lack the background knowledge (schemas) the text assumes. Reading comprehension is as much about knowledge as about reading skills.

Why misconceptions persist: Incorrect schemas are still schemas. They actively shape how students interpret new information, often causing them to distort correct information to fit their existing (wrong) understanding.

Teachers can build student schemas by explicitly connecting new information to what students already know and providing multiple examples that highlight common patterns. Effective strategies include using graphic organisers, concept maps, and structured discussions that help students see relationships between ideas. Regular review and application of concepts in different contexts strengthens these mental frameworks over time.

| Strategy | How It Builds Schemas | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Activate prior knowledge | Prepares relevant schemas for new learning | "What do you already know about the Victorians?" |

| Use advance organisers | Provides a structural framework for new information | Outline of the lesson with the key points covered, before starting |

| Concept mapping | Visually represents relationships between concepts | Draw a mind map of WWII, with sub-topics branching out |

| Elaborative interrogation | Encourages students to explain why something is true | "Why do you think the character made that decision?" |

Effective schema building requires deliberate, systematic approaches that connect new learning to students' existing knowledge structures. Teachers can employ several proven strategies to strengthen student schemas and enhance classroom practice.

Strategic schema activation begins with diagnostic assessment of prior knowledge. Teachers should start lessons by asking probing questions about what students already know, using techniques like think-pair-share activities or concept mapping exercises. This reveals existing knowledge structures and identifies misconceptions that could interfere with new learning. For example, before teaching photosynthesis, a science teacher might ask students to draw and explain how they think plants obtain food, revealing whether students hold the common misconception that plants get nutrients solely from soil.

Building robust schemas also requires explicit connection-making throughout instruction. Teachers should regularly use phrases like "This is similar to.." or "Remember when we learned about.." to help students link new concepts to established knowledge structures. Analogies prove particularly powerful - comparing electrical circuits to water flowing through pipes, for instance, helps students build understanding by connecting abstract concepts to familiar experiences. Additionally, providing worked examples followed by guided practice allows students to see expert thinking patterns, gradually building their own organised knowledge structures for tackling similar problems independently.

These practical strategies help teachers activate, connect, and develop students' mental frameworks.

One of the biggest challenges in teaching is addressing misconceptions. These incorrect schemas can be incredibly resistant to change because they shape how students interpret new information. Simply presenting correct information is often not enough to dislodge a firmly held misconception. Instead, teachers must actively challenge these incorrect schemas.

Strategies for addressing misconceptions include:

Educational researchers have identified four primary types of schemas that significantly impact student learning in classroom settings. Content schemas encompass subject-specific knowledge structures, such as a student's understanding of mathematical operations or historical chronology. Formal schemas relate to text structures and organisational patterns, helping students navigate different genres and formats. Linguistic schemas involve language knowledge, including vocabulary, grammar, and syntax, whilst cultural schemas encompass the social and cultural knowledge students bring from their lived experiences.

Richard Anderson's research on reading comprehension demonstrates how these schema types work together to support learning. When students encounter new material, they simultaneously draw upon content knowledge, recognise textual patterns, process language structures, and interpret information through their cultural lens. Teachers who understand these interconnected schema types can better identify why students might struggle with particular concepts or texts.

Effective classroom practice involves strategically activating and building each schema type. For content schemas, teachers might use concept maps or knowledge webs to connect new information to existing understanding. To support formal schemas, explicit instruction in text structures helps students recognise patterns across different subjects. Building linguistic schemas through vocabulary pre-teaching and cultural schemas through inclusive examples ensures all students can access new learning through their existing knowledge structures.

Decades of cognitive science research have consistently demonstrated that schemas profoundly influence how students process and retain new information. Richard Anderson's seminal studies in the 1970s showed that students with relevant background knowledge could recall up to 40% more details from texts compared to those lacking schema connections. Similarly, John Sweller's cognitive load theory reveals that when students can connect new material to existing knowledge structures, their working memory is freed up to focus on deeper understanding rather than basic comprehension.

More recent research by cognitive scientist Daniel Willingham confirms that factual knowledge stored in long-term memory is the foundation of reading comprehension and critical thinking. His studies demonstrate that students cannot simply learn generic thinking skills in isolation; they need robust schemas within specific domains to think effectively. This finding challenges traditional approaches that prioritise skills over knowledge acquisition.

In classroom contexts, these research findings translate into clear teaching strategies. Teachers who systematically activate students' prior knowledge before introducing new concepts see measurably better learning outcomes. The key is helping students recognise connections between what they already know and new material, essentially building bridges between existing schemas and emerging knowledge structures.

Schemas are fundamental to how students learn. By understanding how schemas work, teachers can create more effective and engaging learning experiences. Activating prior knowledge, explicitly building connections between ideas, and addressing misconceptions are all key strategies for using the power of schemas in the classroom.

Ultimately, teaching is about helping students build rich, accurate, and flexible schemas. By focusing on schema development, educators can helps students to become lifelong learners who are able to make sense of the world around them.

The most powerful implication of schema theory lies in its emphasis on making learning connections explicit rather than assuming students will naturally see relationships between concepts. This requires teachers to regularly model their own thinking processes, showing students how new information relates to previously learned material. For instance, when introducing photosynthesis, effective teachers might explicitly connect it to students' existing schemas about breathing, food, and plant growth rather than presenting it as an isolated biological process.

Successfully implementing schema theory also demands that teachers become skilled diagnosticians of student understanding. This involves using formative assessment techniques that reveal what students know and how they organise that knowledge. Simple strategies such as concept mapping, think-alouds, or asking students to explain connections between topics can illuminate the structure of their schemas and highlight areas where misconceptions might be forming or where knowledge gaps need addressing.

Ultimately, schema theory reminds us that learning is fundamentally about transformation rather than accumulation. When teachers focus on helping students modify and expand their existing knowledge structures, rather than simply adding new facts, they create conditions for deeper understanding and more successful transfer of learning to new situations and contexts.

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/lets-talk-about-schemas#article","headline":"Schemas in Education: How Prior Knowledge Shapes New Learning","description":"Explore how schemas influence learning and memory. Understand why activating prior knowledge matters and how teachers can build, activate, and challenge...","datePublished":"2021-03-18T09:30:35.227Z","dateModified":"2026-01-26T10:09:32.212Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/lets-talk-about-schemas"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/696a16a885ac04a0d26b1f58_696a16a778c10255cc0eb148_lets-talk-about-schemas-infographic.webp","wordCount":1633},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/lets-talk-about-schemas#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"Schemas in Education: How Prior Knowledge Shapes New Learning","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/lets-talk-about-schemas"}]},{"@type":"FAQPage","mainEntity":[{"@type":"Question","name":"What Is a Schema?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"A schema is a mental framework that helps organise and interpret information. First described by psychologist Frederic Bartlett in 1932 and later developed by Jean Piaget and Vygotsky's theory , schema theory explains how we use existing knowledge to understand new experiences. When you hear th e word \"restaurant,\" you automatically activate a schema that includes expectations about menus, ordering, eating, and paying, even if you have never been to that particular restaurant."}},{"@type":"Question","name":"Why Are Schemas Important for Teaching?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Schemas are crucial for teaching because students with well-developed schemas in a subject area learn new related content significantly faster and more deeply than those starting from scratch. Teachers who understand schema theory can design lessons that activate prior knowledge before introducing new concepts, making learning more efficient and meaningful. This understanding also helps teachers identify why some students struggle with certain topics while others grasp them quickly."}},{"@type":"Question","name":"How Can Teachers Build Student Schemas?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Teachers can build student schemas by explicitly connecting new information to what students already know and providing multiple examples that highlight common patterns. Effective strategies include using graphic organisers, concept maps, and structured discussions that help students see relationships between ideas. Regular review and application of concepts in different contexts strengthens these mental frameworks over time."}}]}]}