Functionalism in Psychology and Sociology: How Systems Serve Society

Explore functionalism in psychology and sociology, examining how this perspective interprets behaviour and education's role in serving social functions.

Explore functionalism in psychology and sociology, examining how this perspective interprets behaviour and education's role in serving social functions.

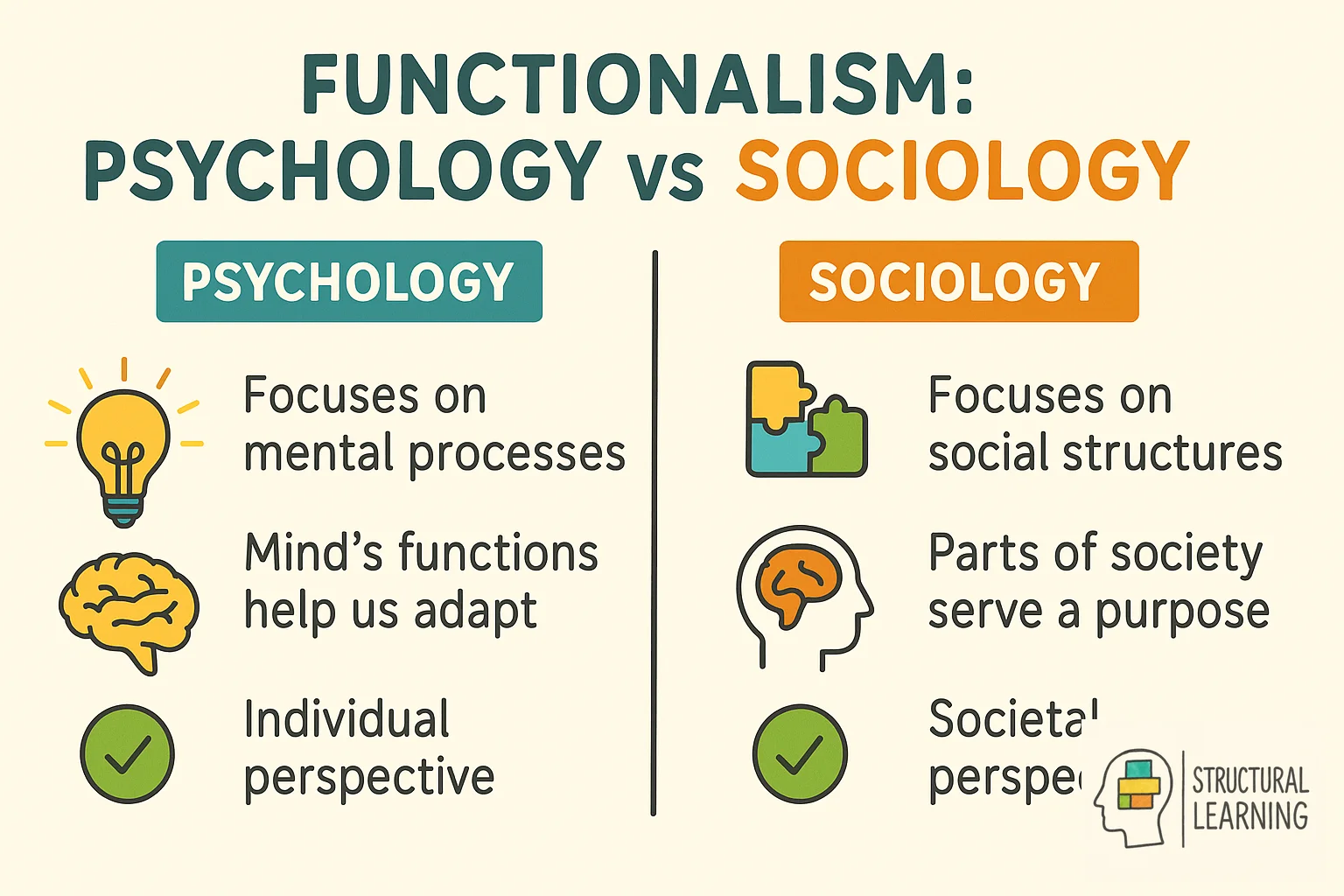

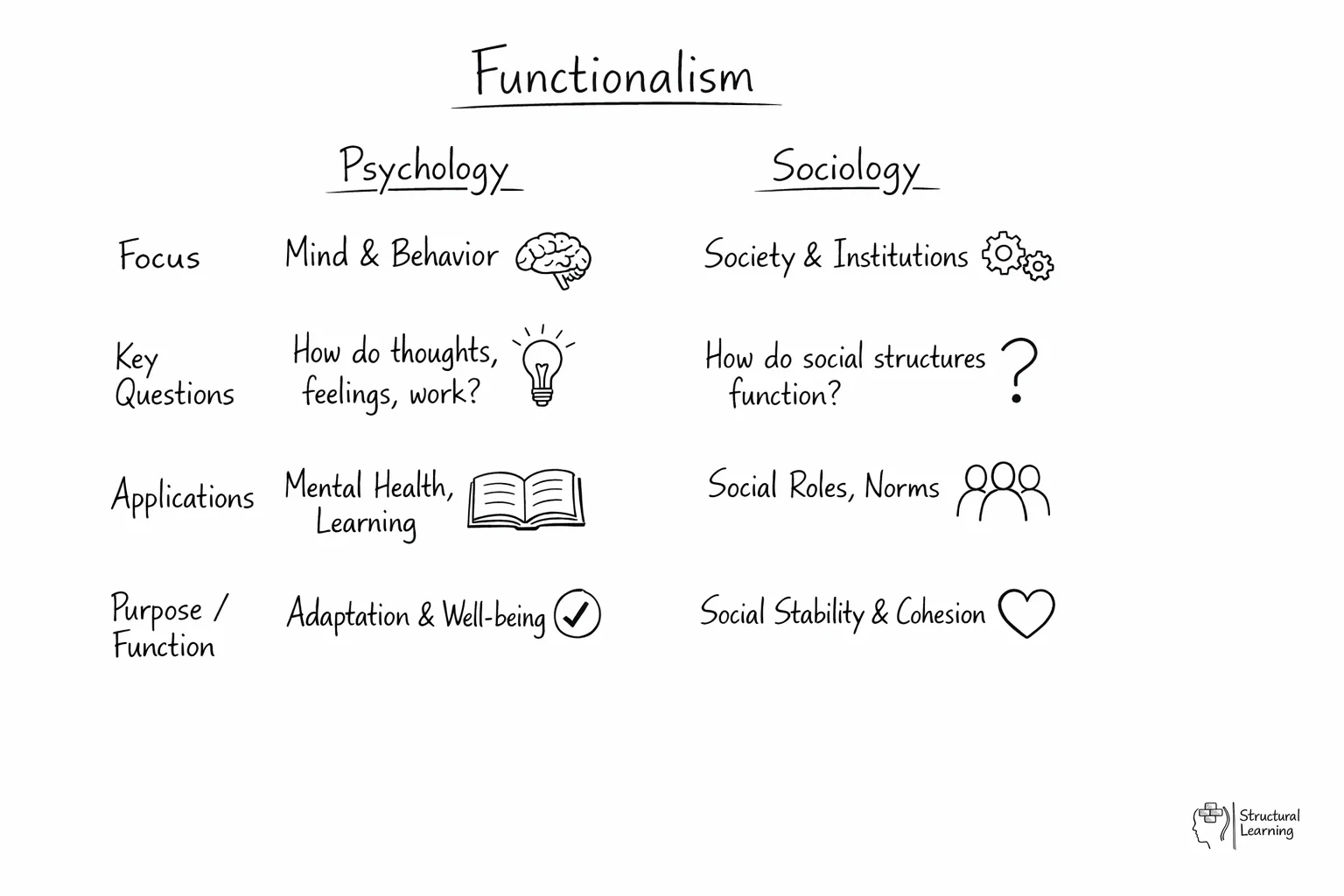

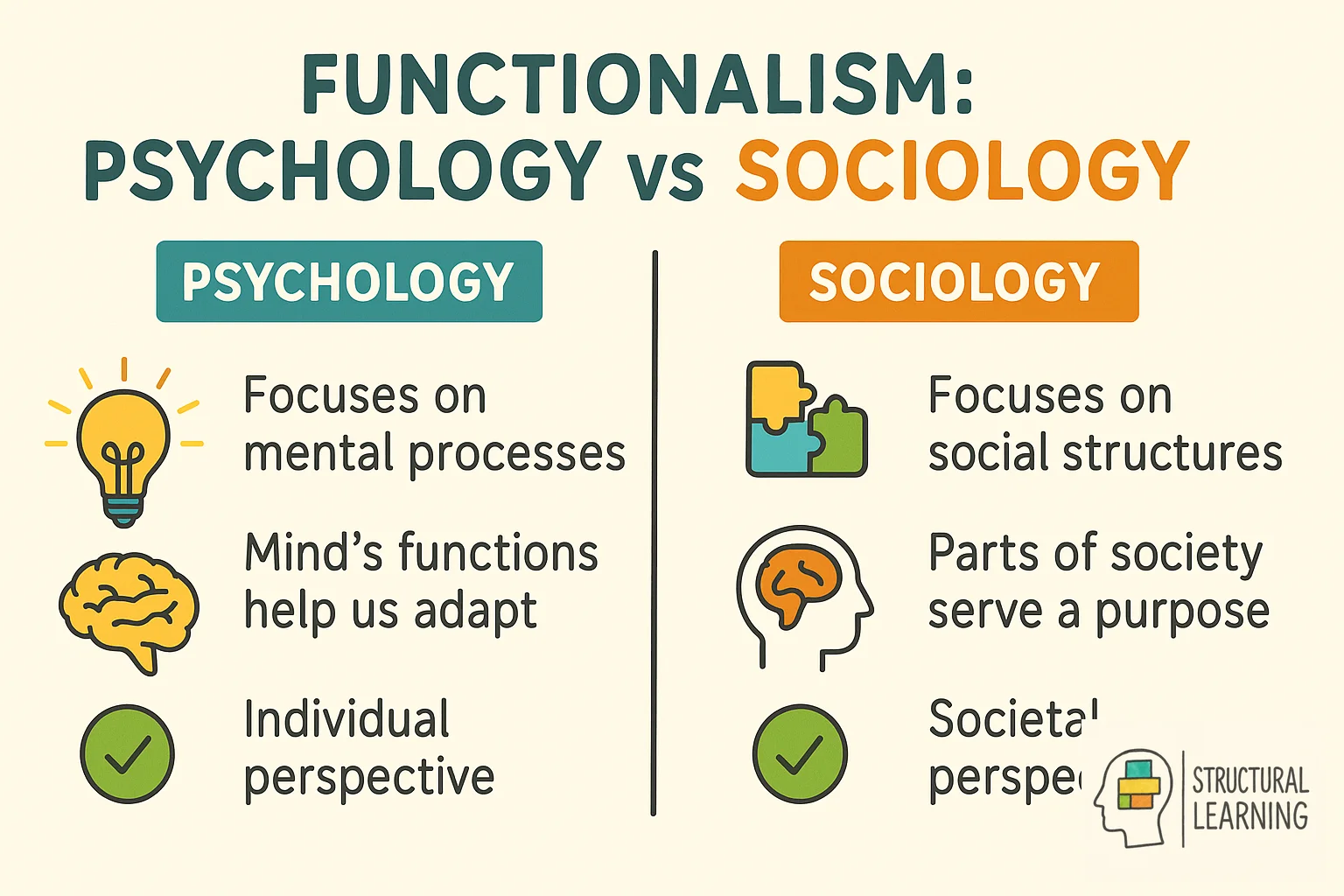

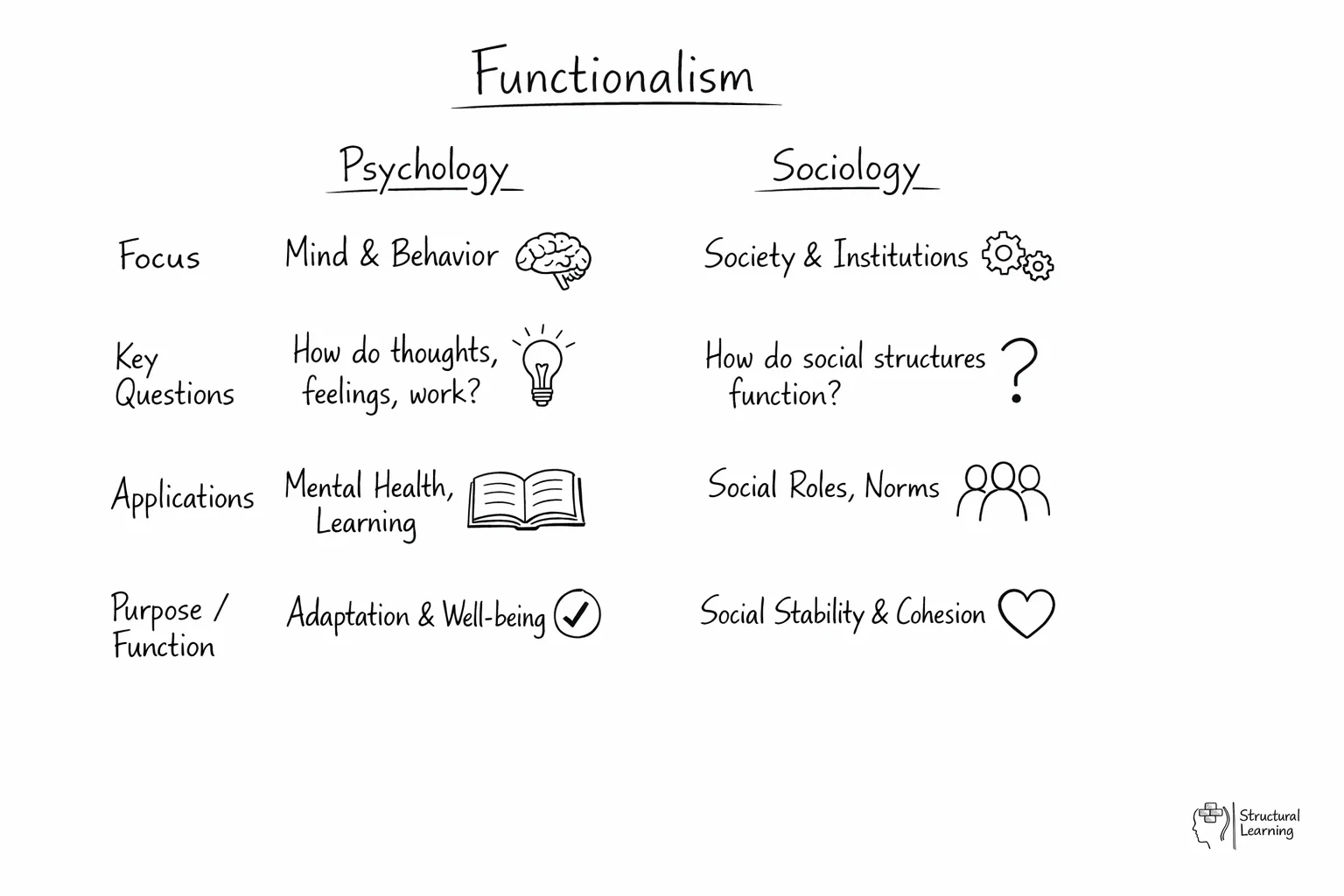

Functionalism is a theoretical perspective that examines why behaviours and social institutions exist by focusing on their purposes or functions. In psychology, it studies how mental processes help individuals adapt to their environment, while in sociology, it analyses how social institutions like schools contribute to societal stability. Both approaches emphasise understanding systems through their practical purposes rather than their structures.

Functionalism is a theoretical perspective that appears in both psychology and sociology, though with different emphases. In psychology, functionalism focused on why behaviours and mental processes exist, asking what function they serve. In sociology, structural functionalism examines how social institutions like education contribute to social stability. Understanding functionalism helps teachers see how schools are viewed as serving essential social purposes, from socialisation to selection, while also recognising the limitations of this perspective.

In psychology, functionalism emphasises the importance of understanding mental processes in terms of their adaptive functions for the individual. Unlike humanistic psychology, which focuses on personal growth and self-actualisation, functionalism examines how behaviours serve specific purposes. This perspective shares common ground with behaviourism in its focus on observable outcomes, yet differs in its emphasis on mental processes and consciousness. While cognitivism examines internal thought processes, functionalism asks why these processes exist and what adaptive purposes they serve. Here, we will explore the definition of functionalism in both sociology and psychology, its key principles, and its impact on the study of human behaviour and society.

Functionalism emerged as a school of thought in psychology in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, as a reaction to structuralism and the focus on the structure of mental processes. William James, an American philosopher and psychologist, played a significant role in the development of functionalism, emphasising the practical and adaptive functions of behaviour.

The theory gained traction at the University of Chicago and Columbia University, where experimental psychology was a central focus. Influential figures in the development of functionalism included John Dewey, a philosopher and psychologist who emphasised the importance of studying the organism as a whole in its environment, and Harvey A. Carr, who further developed the functionalist perspective.

James Rowland Angell, another influential figure, served as the president of the American Psychological Association and made significant contributions to the study of behaviour and mental processes from a functionalist perspective. Edward Thorndike, while primarily associated with behaviourism and connectionism, was influenced by functionalist thinking during his early career.

Overall, the historical background of functionalism in psychology is characterised by a shift towards understanding the adaptive functions of behaviour and mental processes, with key figures such as William James, Dewey, Carr, Angell, and Thorndike shaping the development of the theory.

The development of functionalism was shaped by pioneering thinkers who challenged traditional psychological approaches and emphasised the adaptive purposes of mental processes. Understanding these foundational figures provides essential context for how functionalist thinking evolved and continues to influence educational practice today.

William James (1842-1910) is widely regarded as the founder of functional psychology in America. His seminal work, The Principles of Psychology (1890), transformed psychological thinking by shifting focus from the structure of consciousness to its function. James argued that mental processes exist because they serve practical purposes in helping organisms adapt to their environments.

James introduced the concept of the "stream of consciousness," emphasising that mental life flows continuously rather than existing as discrete elements. This perspective had profound implications for education, suggesting that learning involves active, purposeful mental activity rather than passive reception of information. His pragmatic approach influenced educational reformers who sought to make schooling more relevant to students' lived experiences.

For teachers, James's insights remain relevant today. His emphasis on habit formation as a key educational goal aligns with contemporary understanding of how routine behaviours become automatic, freeing cognitive resources for higher-order thinking. James recognised that education should cultivate practical skills and adaptive thinking patterns, not merely transfer abstract knowledge.

John Dewey (1859-1952) extended functionalist principles into educational philosophy, becoming one of the most influential educational theorists of the twentieth century. His 1896 paper "The Reflex Arc Concept in Psychology" challenged mechanistic views of behaviour, arguing instead for understanding organisms as unified wholes adapting to environmental demands.

Dewey's functional psychology directly informed his educational philosophy, which emphasised experiential learning and the importance of connecting school activities to real-world problems. He founded the Laboratory School at the University of Chicago, where he tested his theories about learning through purposeful activity. Dewey believed that education should help students develop problem-solving abilities applicable to actual life situations rather than memorising decontextualised facts.

The connection between John Dewey's theory and functionalism is evident in his view that thinking itself is a tool for solv ing problems. This perspective aligns with inquiry-based learning approaches where students investigate meaningful questions rather than passively receiving information. Dewey's emphasis on education as growth and adaptation continues to influence progressive educational practices worldwide.

Teachers applying Deweyan principles recognise that learning activities should serve clear purposes from the student's perspective. Rather than asking students to complete exercises simply because they are assigned, effective educators help learners understand how skills and knowledge function to solve real problems and achieve meaningful goals.

Harvey Carr (1873-1954) and James Rowland Angell (1869-1949) played crucial roles in developing functionalism into a systematic psychological school at the University of Chicago. Angell's 1907 presidential address to the American Psychological Association outlined three fundamental characteristics of functionalism: studying mental operations rather than mental elements, examining the utilities of consciousness, and investigating mind-body relationships.

Carr further refined functionalist concepts through his work on adaptive behaviour and learning. His textbook Psychology: A Study of Mental Activity (1925) presented a comprehensive functionalist framework emphasising how organisms adjust to environmental demands. Carr's research on maze learning and spatial navigation demonstrated how mental processes serve practical, adaptive functions.

For educators, the Chicago School functionalists provided scientific validation for progressive education reforms. Their research showed that learning involves active adaptation rather than passive absorption, supporting educational approaches that engage students in purposeful problem-solving activities. The emphasis on studying whole organisms in natural environments influenced later ecological approaches to understanding classroom learning.

| Thinker | Key Contribution | Educational Implication |

|---|---|---|

| William James | Stream of consciousness; habit formation; pragmatic psychology | Education should develop practical habits and adaptive thinking patterns |

| John Dewey | Learning through experience; problem-solving focus; unified organism concept | Connect school activities to real-world problems; emphasise purposeful inquiry |

| James Rowland Angell | Systematised functionalist principles; utilities of consciousness | Study learning as active mental operations serving adaptive purposes |

| Harvey Carr | Adaptive behaviour research; mental activity as environmental adjustment | Learning involves organisms actively adjusting to environmental demands |

The emergence of functionalism represented a decisive break from structuralism, the dominant psychological approach of the late nineteenth century. Understanding this contrast illuminates why functionalist thinking proved particularly valuable for educational theory and practice.

Structuralism, pioneered by Wilhelm Wundt and Edward Titchener, sought to identify the basic elements of consciousness through introspection. Structuralists believed that by breaking down mental experiences into their simplest components, sensations, feelings, and images, they could discover the structure of the mind, much as chemists identify elemental compounds.

Functionalism rejected this approach as artificially fragmenting mental life. William James famously criticised structuralist introspection as dissecting consciousness in ways that destroyed its essential nature. Instead of asking "What are the elements of consciousness?" functionalists asked "What does consciousness do?" and "Why does it exist?" This shift from structure to function represented a fundamental reorientation of psychological inquiry.

The contrast reflects broader philosophical differences. Structuralism aligned with elementalism and reductionism, assuming that complex phenomena could be understood by analysing constituent parts. Functionalism embraced holism and pragmatism, insisting that mental processes must be understood in relation to the adaptive challenges organisms face in their environments.

Structuralists relied heavily on trained introspection, requiring subjects to report immediate conscious experiences without interpretation. This method demanded extensive training and produced data that critics argued was subjective and unreliable. Structuralist laboratories focused on controlled experimental conditions, often studying artificial stimuli far removed from everyday experience.

Functionalists employed broader methodological approaches, including naturalistic observation, mental tests, questionnaires, and objective behavioural measures. They studied children, animals, and people with mental disabilities, populations structuralists largely ignored. This methodological eclecticism reflected functionalism's pragmatic orientation: any method that illuminated how mental processes function was legitimate.

For education, the methodological implications were significant. Structuralist psychology offered limited practical guidance for teachers because it focused on artificial laboratory conditions rather than actual learning environments. Functionalism's emphasis on studying behaviour in natural contexts made it far more relevant to classroom practice, influencing the development of educational psychology as a distinct discipline.

The structuralist view suggested that learning involved accumulating mental elements and associations. This perspective aligned with traditional educational practices emphasising rote memorisation and drill. If the mind consisted of discrete elements, education meant building up a storehouse of sensations, images, and associations.

Functionalism offered a fundamentally different conception. Learning was not accumulation but adaptation, the development of effective responses to environmental challenges. This perspective supported educational reforms emphasising active problem-solving, critical thinking, and application of knowledge to real situations. Rather than viewing students as containers to be filled with facts, functionalists saw learners as active organisms developing adaptive capabilities.

The functionalist emphasis on purpose and meaning also contrasted with structuralist focus on elementary sensations. For functionalists, learning required understanding why information matters and how it functions to solve problems or achieve goals. This insight remains central to contemporary educational practice, where teachers recognise that meaningful learning depends on students understanding purposes and applications, not merely memorising isolated facts.

| Dimension | Structuralism | Functionalism |

|---|---|---|

| Core Question | What are the elements of consciousness? | What does consciousness do? Why does it exist? |

| Primary Method | Trained introspection in controlled laboratory settings | Multiple methods including observation, tests, and behavioural measures |

| Focus | Structure and elements of mental experience | Purpose and adaptive functions of behaviour |

| View of Mind | Collection of discrete elements (sensations, images, feelings) | Continuous stream of activity serving adaptive purposes |

| Educational Implications | Learning as accumulation of mental elements; emphasis on drill and memorisation | Learning as adaptation; emphasis on problem-solving and purposeful activity |

| Practical Utility | Limited application to real-world problems | Direct relevance to education, clinical practice, and applied psychology |

The key founders include William James in psychology, who established functionalism as an alternative to structuralism in the late 1800s. In sociology, Emile Durkheim pioneered structural functionalism by studying how social institutions maintain order, while Talcott Parsons later developed the theory further in the mid-20th century. Other notable figures include Robert Merton, who refined functionalist concepts with ideas like manifest and latent functions.

1. David Lewis: As a proponent of role functionalism, David Lewis argued that mental states are defined by their causal roles in cognitive processes. He emphasised the importance of understanding mental states in terms of their functions and relationships to other mental states. Lewis's work has significantly shaped the debate on functionalism by highlighting the role of causal relations in memory and mental processes.

2. Hilary Putnam: Hilary Putnam is known for his advocacy of realizer functionalism, which focuses on the physical realisations of mental states. He argued that mental states are not solely defined by their functional roles, but also by their physical properties. In educational contexts, this perspective influences how teachers understand student attention as both functional cognitive processes and physical brain states.

3. Jerry Fodor: Jerry Fodor is a key figure in functionalism who has contributed to the field through his arguments for the modularity of mind. As a proponent of role functionalism, Fodor emphasised the specialised functions of mental processes and their distinct roles in cognition. His work has played a significant role in shaping the debate on functionalism by highlighting the complexity and specificity of mental functions.

4. Ned Block: Ned Block is known for his criticisms of functionalism and his development of the absent qualia argument. Block has challenged functionalism by arguing that functional organisation alone cannot account for conscious experience. His work has contributed to debates about whether functional roles are sufficient to explain all aspects of mental states, particularly consciousness in educational settings.

These founding figures have collectively shaped functionalism into a robust theoretical framework that continues to influence both psychological research and educational practice. Their contributions demonstrate how mental processes serve adaptive functions, helping educators understand why certain learning behaviours emerge and persist in classroom environments.

Functionalist psychology and sociology offer powerful frameworks for understanding educational processes, institutional purposes, and student behaviour. By recognising that mental processes and social structures serve specific functions, educators can develop more effective teaching strategies and create learning environments that align with students' adaptive needs.

From a functionalist perspective, schools serve multiple interconnected purposes beyond academic instruction. Manifest functions, the intended, obvious purposes, include transmitting knowledge, developing skills, and providing credentials that sort students for future social roles. Teachers explicitly plan lessons, assess learning, and award qualifications to fulfil these manifest functions.

However, schools also perform crucial latent functions, unintended but socially important consequences. These include socialisation into cultural norms, provision of childcare enabling parental employment, creation of peer networks, and transmission of cultural values. Understanding these latent functions helps teachers recognise why certain institutional practices persist even when they seem inefficient or outdated from a purely academic perspective.

For example, the functionalist perspective illuminates why schools maintain rigid timetables, age-based cohorts, and standardised curricula. These structures serve latent functions of preparing students for industrial work rhythms, creating predictable childcare arrangements, and establishing common cultural reference points. Teachers who understand these multiple functions can make more informed decisions about when to work within existing structures and when to advocate for change.

Functionalist principles complement and inform various learning theories that teachers encounter in professional practice. The emphasis on adaptive behaviour connects naturally with constructivism, which views learning as active construction of knowledge to solve problems and understand experiences. Both perspectives recognise that learning serves purposes beyond mere information storage, it enables increasingly sophisticated adaptation to complex environments.

The functionalist question "What purpose does this behaviour serve?" proves particularly valuable when addressing challenging student behaviours. Rather than viewing challenging actions as mere rule violations requiring punishment, functionalist-informed teachers investigate what adaptive purpose the behaviour serves for the student. Is the student seeking attention, avoiding difficult work, gaining peer status, or expressing frustration with unclear expectations? Identifying the function enables teachers to address underlying needs rather than merely suppressing symptoms.

This functional approach to behaviour aligns with positive behaviour support frameworks used in contemporary schools. By teaching alternative behaviours that serve the same function more appropriately, teachers help students develop adaptive repertoires. For instance, a student who disrupts lessons to avoid challenging work might be taught to request help or break tasks into manageable steps, alternative strategies serving the same function of reducing anxiety without disrupting learning.

Functionalist insights translate into specific teaching practices that enhance student engagement and learning effectiveness. When planning lessons, teachers can explicitly consider what adaptive purposes the learning serves from students' perspectives. Making these purposes clear, through real-world applications, authentic projects, or connections to students' interests, increases motivation and meaningful engagement.

The functionalist emphasis on whole organisms adapting to environments also supports comprehensive teaching approaches. Rather than focusing narrowly on academic skills in isolation, effective teachers recognise that learning involves social, emotional, and physical dimensions. Creating classroom environments that support these multiple aspects of student functioning promotes more effective adaptation and deeper learning.

Assessment practices benefit from functionalist perspectives as well. Rather than viewing tests solely as measurement instruments, teachers can design assessments that serve multiple functions: providing feedback to guide learning, helping students recognise their progress, informing instructional adjustments, and developing metacognitive skills. Understanding assessment's multiple functions enables teachers to select appropriate methods for different purposes rather than relying on single approaches.

| Educational Function | Manifest (Intended) | Latent (Unintended) |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge Transmission | Teaching curriculum content and skills | Transmitting cultural values and middle-class norms |

| Socialisation | Developing cooperation and social skills | Training in obedience to authority and conformity |

| Social Selection | Awarding qualifications based on merit | Reproducing social class structures; credentialism |

| Childcare Provision | Supervising children during working hours | Enabling both parents to participate in labour force |

| Social Integration | Creating shared identity and community | Marginalising non-dominant cultures; assimilation pressure |

While functionalism originated over a century ago, its core principles remain relevant to contemporary educational challenges and innovations. Modern applications demonstrate how functionalist thinking adapts to new contexts while maintaining its emphasis on understanding systems through their purposes and functions.

The rise of educational technology offers new contexts for applying functionalist analysis. Rather than asking whether specific technologies are "good" or "bad" for learning, a functionalist approach examines what functions they serve and how effectively they support adaptive learning processes.

For example, learning management systems serve manifest functions of organising resources, tracking progress, and facilitating communication. However, they also perform latent functions such as increasing surveillance of student activity, standardising pedagogical approaches, and extending school time into home environments. Teachers who recognise these multiple functions can make more informed decisions about technology adoption and use.

The functionalist emphasis on mental processes serving adaptive purposes also illuminates debates about digital tools and cognitive development. Rather than viewing technologies like calculators or spell-checkers as simply "doing students' thinking for them," functionalist analysis asks what cognitive functions these tools support. When calculators free cognitive resources from computational procedures for higher-order problem-solving, they enhance rather than diminish mathematical thinking. Understanding these functional relationships helps teachers integrate technologies effectively.

Functionalist perspectives prove particularly valuable in inclusive educational contexts serving students with diverse learning needs. The functionalist question "What purpose does this behaviour serve?" becomes essential when supporting students with disabilities, challenging behaviours, or different developmental trajectories.

For students with autism spectrum conditions, repetitive behaviours that might appear non-functional often serve important self-regulation purposes, helping manage sensory input or reduce anxiety. Teachers who understand these adaptive functions can create environments that meet underlying needs while teaching alternative strategies when behaviours interfere with learning or social inclusion.

Similarly, functionalist analysis illuminates how different students may achieve similar learning outcomes through diverse pathways. Rather than insisting all students use identical methods, teachers can focus on whether different approaches serve the same adaptive functions of understanding concepts, solving problems, or demonstrating learning. This functional equivalence perspective supports differentiation and universal design for learning.

Contemporary emphasis on social-emotional learning (SEL) and student mental health reflects functionalist principles about education serving multiple adaptive purposes. Schools increasingly recognise that supporting emotional regulation, relationship skills, and psychological wellbeing functions as essential preparation for adaptive functioning in complex social environments.

From a functionalist perspective, SEL programmes serve both manifest functions (explicitly teaching emotion regulation and social skills) and latent functions (reducing behaviour problems, improving school climate, and addressing broader societal concerns about youth mental health). Understanding these multiple functions helps educators justify resource allocation and design comprehensive approaches.

The functionalist emphasis on adaptation also supports trauma-informed educational practices. Rather than viewing traumatised students' behaviours as intentional misbehaviour, trauma-informed teachers recognise these responses as adaptive strategies developed in threatening environments. While behaviours like hypervigilance or emotional withdrawal may have served protective functions in traumatic contexts, they become maladaptive in safe learning environments. Effective intervention involves teaching new adaptive responses appropriate to current contexts while recognising past adaptations made sense given students' experiences.

Functionalist analysis illuminates contemporary debates about educational accountability, testing, and school performance measures. While accountability systems' manifest function involves improving educational quality through measurement and comparison, they also serve latent functions including political legitimation of educational spending, market-based competition between schools, and standardisation of curriculum and pedagogy.

Teachers navigating accountability pressures benefit from understanding these multiple functions. Recognition that high-stakes testing serves purposes beyond measuring student learning, such as rationing access to higher education or demonstrating governmental action on educational quality, enables more critical engagement with testing regimes. Rather than accepting accountability measures uncritically or rejecting them entirely, functionalist-informed teachers can advocate for approaches that effectively serve intended purposes while minimising harmful unintended consequences.

The functionalist concept of dysfunction proves particularly relevant here. When accountability systems create perverse incentives, such as narrowing curriculum, teaching to tests, or excluding struggling students, they fail to serve their intended functions and may actively undermine educational quality. Identifying these dysfunctions enables advocacy for systemic reforms that better align structures with purposes.

In educational settings, functionalism provides a lens for understanding how schools operate as social systems serving multiple purposes beyond academic instruction. Teachers can apply functionalist principles to recognise that student behaviours, classroom routines, and institutional practices all serve specific functions in maintaining educational stability and promoting social cohesion.

From a functionalist perspective, schools perform several manifest functions including knowledge transmission, skill development, and academic credentialing. However, they also serve latent functions such as childcare, social sorting, and cultural transmission. Understanding these dual purposes helps teachers recognise why certain educational practices persist even when they may seem inefficient or outdated.

Robert Merton's concept of dysfunction is particularly relevant in educational contexts. When schools fail to serve their intended functions or create unintended negative consequences, teachers must identify these dysfunctions and work to address them. For example, rigid streaming systems may serve the function of academic differentiation but create dysfunctions through reduced expectations and social segregation.

The functionalist emphasis on social equilibrium also influences classroom management approaches. Teachers who understand functionalist principles recognise that challenging behaviour often serves a function for the student, whether seeking attention, avoiding difficult tasks, or maintaining social status. Effective interventions address these underlying functions rather than merely suppressing symptoms.

Merton's adaptation to strain theory offers valuable insights into student responses to academic pressure and social expectations. His five modes of adaptation help teachers understand diverse student reactions to educational goals and institutional means.

Conformist students accept both educational goals and legitimate means of achieving them, typically displaying conventional academic behaviour and following school rules. Innovation occurs when students accept educational goals but reject legitimate means, perhaps resorting to cheating or other unauthorised methods to achieve academic success.

Ritualism manifests when students abandon educational goals but continue following institutional means, going through the motions of schooling without genuine engagement or aspiration. Retreatism involves rejecting both goals and means, leading to disengagement and potential dropout behaviour. Finally, rebellion represents attempts to replace existing educational goals and means with alternative systems or approaches.

Teachers who recognise these adaptation patterns can develop more targeted interventions, addressing the underlying strain between culturally emphasised goals and available opportunities rather than simply managing surface behaviours.

| Adaptation Mode | Cultural Goals | Institutional Means | School Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conformity | Accepts | Accepts | Student studies diligently, follows rules, aims for qualifications |

| Innovation | Accepts | Rejects | Student wants high grades but resorts to cheating or plagiarism |

| Ritualism | Rejects | Accepts | Student attends and completes work mechanically without ambition |

| Retreatism | Rejects | Rejects | Student becomes disengaged, truant, or drops out entirely |

| Rebellion | Replaces with new goals | Replaces with new means | Student advocates for alternative education or radical reform |

While functionalism provides valuable insights into social and psychological processes, it faces significant criticisms including an over-emphasis on stability, neglect of conflict and change, and tendency towards conservative bias. Critics argue that functionalist approaches may overlook power imbalances, inequality, and the need for educational reform by focusing primarily on system maintenance rather than transformation.

One major criticism centres on functionalism's assumption that existing social arrangements serve positive purposes. In educational contexts, this can lead to uncritical acceptance of practices that may perpetuate inequality or limit student potential. For example, functionalist explanations of educational streaming may overlook how such systems reproduce social class divisions rather than promoting meritocracy.

The theory's emphasis on consensus and stability has been challenged by conflict theorists who highlight how schools may serve the interests of dominant groups rather than society as a whole. Pierre Bourdieu's work on cultural capital demonstrates how seemingly neutral educational practices can disadvantage students from certain backgrounds, contradicting functionalist assumptions about equal opportunity.

Contemporary educational research increasingly recognises the need to balance functionalist insights with critical perspectives that examine power, inequality, and social justice. Teachers benefit from understanding both how educational systems function and how they might be transformed to better serve all students.

Functionalism remains a valuable theoretical framework for understanding both psychological processes and social institutions, offering teachers practical insights into why behaviours and educational practices persist. By recognising that mental processes serve adaptive functions and that schools operate as complex social systems, educators can develop more effective approaches to teaching, learning, and classroom management.

The functionalist emphasis on purpose and adaptation helps teachers understand that student behaviours, even challenging ones, typically serve specific functions for the individual. This perspective encourages educators to look beyond surface symptoms to identify underlying needs and develop interventions that address root causes rather than merely managing consequences.

However, effective educational practice requires balancing functionalist insights with critical awareness of power, inequality, and the need for change. While understanding how educational systems maintain stability is valuable, teachers must also remain committed to challenging practices that limit student potential or perpetuate injustice. The most effective educators combine functionalist understanding of system purposes with critical examination of whether those purposes truly serve all students' needs.

For educators interested in exploring functionalism further, the following academic sources provide valuable insights into both theoretical foundations and practical applications:

These resources offer both theoretical grounding and practical applications that can enhance understanding of functionalist principles in educational contexts. Teachers are encouraged to critically engage with these perspectives while considering their implications for contemporary classroom practice.

What is the main difference between functionalism in psychology and sociology?

Functionalism in psychology focuses on how mental processes and behaviours help individuals adapt to their environment and serve specific purposes for survival and wellbeing. In contrast, sociological functionalism examines how social institutions like schools, families, and governments work together to maintain social stability and meet society's needs. Both approaches emphasise understanding systems through their functions, but psychology looks at individual adaptation while sociology examines societal cohesion.

How can teachers apply functionalist theory in their classrooms?

Teachers can use functionalist principles by recognising that student behaviours serve specific functions, even when they appear challenging. Instead of simply stopping unwanted behaviour, effective teachers identify what function the behaviour serves (attention-seeking, task avoidance, social connection) and provide alternative ways to meet those needs. Additionally, understanding the multiple functions schools serve helps teachers balance academic instruction with social development and cultural transmission.

What are manifest and latent functions in education?

Manifest functions are the intended, obvious purposes of educational institutions, such as teaching literacy, numeracy, and subject knowledge. Latent functions are the unintended but important consequences, including socialisation, childcare provision, social sorting, and cultural transmission. For example, school assemblies have the manifest function of sharing information but the latent function of building community identity and reinforcing shared values.

Why is functionalism criticised in educational settings?

Critics argue that functionalism can justify existing inequalities by suggesting that all social arrangements serve necessary purposes. In education, this might lead to accepting practices like streaming or standardised testing without questioning whether they truly benefit all students. Functionalism may also overlook how schools can perpetuate social class differences and fail to challenge systems that disadvantage certain groups of learners.

How does Merton's strain theory apply to student achievement?

Merton's theory explains different student responses to academic pressure through five adaptation modes. Conformist students accept both educational goals and legitimate means of achieving them. Innovators want academic success but may cheat or use unauthorised methods. Ritualists follow school routines without caring about achievement. Retreatists disengage from both goals and means, while rebels seek to replace existing educational systems with alternatives. Understanding these patterns helps teachers provide appropriate support for different student needs.

Functionalism is a theoretical perspective that examines why behaviours and social institutions exist by focusing on their purposes or functions. In psychology, it studies how mental processes help individuals adapt to their environment, while in sociology, it analyses how social institutions like schools contribute to societal stability. Both approaches emphasise understanding systems through their practical purposes rather than their structures.

Functionalism is a theoretical perspective that appears in both psychology and sociology, though with different emphases. In psychology, functionalism focused on why behaviours and mental processes exist, asking what function they serve. In sociology, structural functionalism examines how social institutions like education contribute to social stability. Understanding functionalism helps teachers see how schools are viewed as serving essential social purposes, from socialisation to selection, while also recognising the limitations of this perspective.

In psychology, functionalism emphasises the importance of understanding mental processes in terms of their adaptive functions for the individual. Unlike humanistic psychology, which focuses on personal growth and self-actualisation, functionalism examines how behaviours serve specific purposes. This perspective shares common ground with behaviourism in its focus on observable outcomes, yet differs in its emphasis on mental processes and consciousness. While cognitivism examines internal thought processes, functionalism asks why these processes exist and what adaptive purposes they serve. Here, we will explore the definition of functionalism in both sociology and psychology, its key principles, and its impact on the study of human behaviour and society.

Functionalism emerged as a school of thought in psychology in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, as a reaction to structuralism and the focus on the structure of mental processes. William James, an American philosopher and psychologist, played a significant role in the development of functionalism, emphasising the practical and adaptive functions of behaviour.

The theory gained traction at the University of Chicago and Columbia University, where experimental psychology was a central focus. Influential figures in the development of functionalism included John Dewey, a philosopher and psychologist who emphasised the importance of studying the organism as a whole in its environment, and Harvey A. Carr, who further developed the functionalist perspective.

James Rowland Angell, another influential figure, served as the president of the American Psychological Association and made significant contributions to the study of behaviour and mental processes from a functionalist perspective. Edward Thorndike, while primarily associated with behaviourism and connectionism, was influenced by functionalist thinking during his early career.

Overall, the historical background of functionalism in psychology is characterised by a shift towards understanding the adaptive functions of behaviour and mental processes, with key figures such as William James, Dewey, Carr, Angell, and Thorndike shaping the development of the theory.

The development of functionalism was shaped by pioneering thinkers who challenged traditional psychological approaches and emphasised the adaptive purposes of mental processes. Understanding these foundational figures provides essential context for how functionalist thinking evolved and continues to influence educational practice today.

William James (1842-1910) is widely regarded as the founder of functional psychology in America. His seminal work, The Principles of Psychology (1890), transformed psychological thinking by shifting focus from the structure of consciousness to its function. James argued that mental processes exist because they serve practical purposes in helping organisms adapt to their environments.

James introduced the concept of the "stream of consciousness," emphasising that mental life flows continuously rather than existing as discrete elements. This perspective had profound implications for education, suggesting that learning involves active, purposeful mental activity rather than passive reception of information. His pragmatic approach influenced educational reformers who sought to make schooling more relevant to students' lived experiences.

For teachers, James's insights remain relevant today. His emphasis on habit formation as a key educational goal aligns with contemporary understanding of how routine behaviours become automatic, freeing cognitive resources for higher-order thinking. James recognised that education should cultivate practical skills and adaptive thinking patterns, not merely transfer abstract knowledge.

John Dewey (1859-1952) extended functionalist principles into educational philosophy, becoming one of the most influential educational theorists of the twentieth century. His 1896 paper "The Reflex Arc Concept in Psychology" challenged mechanistic views of behaviour, arguing instead for understanding organisms as unified wholes adapting to environmental demands.

Dewey's functional psychology directly informed his educational philosophy, which emphasised experiential learning and the importance of connecting school activities to real-world problems. He founded the Laboratory School at the University of Chicago, where he tested his theories about learning through purposeful activity. Dewey believed that education should help students develop problem-solving abilities applicable to actual life situations rather than memorising decontextualised facts.

The connection between John Dewey's theory and functionalism is evident in his view that thinking itself is a tool for solv ing problems. This perspective aligns with inquiry-based learning approaches where students investigate meaningful questions rather than passively receiving information. Dewey's emphasis on education as growth and adaptation continues to influence progressive educational practices worldwide.

Teachers applying Deweyan principles recognise that learning activities should serve clear purposes from the student's perspective. Rather than asking students to complete exercises simply because they are assigned, effective educators help learners understand how skills and knowledge function to solve real problems and achieve meaningful goals.

Harvey Carr (1873-1954) and James Rowland Angell (1869-1949) played crucial roles in developing functionalism into a systematic psychological school at the University of Chicago. Angell's 1907 presidential address to the American Psychological Association outlined three fundamental characteristics of functionalism: studying mental operations rather than mental elements, examining the utilities of consciousness, and investigating mind-body relationships.

Carr further refined functionalist concepts through his work on adaptive behaviour and learning. His textbook Psychology: A Study of Mental Activity (1925) presented a comprehensive functionalist framework emphasising how organisms adjust to environmental demands. Carr's research on maze learning and spatial navigation demonstrated how mental processes serve practical, adaptive functions.

For educators, the Chicago School functionalists provided scientific validation for progressive education reforms. Their research showed that learning involves active adaptation rather than passive absorption, supporting educational approaches that engage students in purposeful problem-solving activities. The emphasis on studying whole organisms in natural environments influenced later ecological approaches to understanding classroom learning.

| Thinker | Key Contribution | Educational Implication |

|---|---|---|

| William James | Stream of consciousness; habit formation; pragmatic psychology | Education should develop practical habits and adaptive thinking patterns |

| John Dewey | Learning through experience; problem-solving focus; unified organism concept | Connect school activities to real-world problems; emphasise purposeful inquiry |

| James Rowland Angell | Systematised functionalist principles; utilities of consciousness | Study learning as active mental operations serving adaptive purposes |

| Harvey Carr | Adaptive behaviour research; mental activity as environmental adjustment | Learning involves organisms actively adjusting to environmental demands |

The emergence of functionalism represented a decisive break from structuralism, the dominant psychological approach of the late nineteenth century. Understanding this contrast illuminates why functionalist thinking proved particularly valuable for educational theory and practice.

Structuralism, pioneered by Wilhelm Wundt and Edward Titchener, sought to identify the basic elements of consciousness through introspection. Structuralists believed that by breaking down mental experiences into their simplest components, sensations, feelings, and images, they could discover the structure of the mind, much as chemists identify elemental compounds.

Functionalism rejected this approach as artificially fragmenting mental life. William James famously criticised structuralist introspection as dissecting consciousness in ways that destroyed its essential nature. Instead of asking "What are the elements of consciousness?" functionalists asked "What does consciousness do?" and "Why does it exist?" This shift from structure to function represented a fundamental reorientation of psychological inquiry.

The contrast reflects broader philosophical differences. Structuralism aligned with elementalism and reductionism, assuming that complex phenomena could be understood by analysing constituent parts. Functionalism embraced holism and pragmatism, insisting that mental processes must be understood in relation to the adaptive challenges organisms face in their environments.

Structuralists relied heavily on trained introspection, requiring subjects to report immediate conscious experiences without interpretation. This method demanded extensive training and produced data that critics argued was subjective and unreliable. Structuralist laboratories focused on controlled experimental conditions, often studying artificial stimuli far removed from everyday experience.

Functionalists employed broader methodological approaches, including naturalistic observation, mental tests, questionnaires, and objective behavioural measures. They studied children, animals, and people with mental disabilities, populations structuralists largely ignored. This methodological eclecticism reflected functionalism's pragmatic orientation: any method that illuminated how mental processes function was legitimate.

For education, the methodological implications were significant. Structuralist psychology offered limited practical guidance for teachers because it focused on artificial laboratory conditions rather than actual learning environments. Functionalism's emphasis on studying behaviour in natural contexts made it far more relevant to classroom practice, influencing the development of educational psychology as a distinct discipline.

The structuralist view suggested that learning involved accumulating mental elements and associations. This perspective aligned with traditional educational practices emphasising rote memorisation and drill. If the mind consisted of discrete elements, education meant building up a storehouse of sensations, images, and associations.

Functionalism offered a fundamentally different conception. Learning was not accumulation but adaptation, the development of effective responses to environmental challenges. This perspective supported educational reforms emphasising active problem-solving, critical thinking, and application of knowledge to real situations. Rather than viewing students as containers to be filled with facts, functionalists saw learners as active organisms developing adaptive capabilities.

The functionalist emphasis on purpose and meaning also contrasted with structuralist focus on elementary sensations. For functionalists, learning required understanding why information matters and how it functions to solve problems or achieve goals. This insight remains central to contemporary educational practice, where teachers recognise that meaningful learning depends on students understanding purposes and applications, not merely memorising isolated facts.

| Dimension | Structuralism | Functionalism |

|---|---|---|

| Core Question | What are the elements of consciousness? | What does consciousness do? Why does it exist? |

| Primary Method | Trained introspection in controlled laboratory settings | Multiple methods including observation, tests, and behavioural measures |

| Focus | Structure and elements of mental experience | Purpose and adaptive functions of behaviour |

| View of Mind | Collection of discrete elements (sensations, images, feelings) | Continuous stream of activity serving adaptive purposes |

| Educational Implications | Learning as accumulation of mental elements; emphasis on drill and memorisation | Learning as adaptation; emphasis on problem-solving and purposeful activity |

| Practical Utility | Limited application to real-world problems | Direct relevance to education, clinical practice, and applied psychology |

The key founders include William James in psychology, who established functionalism as an alternative to structuralism in the late 1800s. In sociology, Emile Durkheim pioneered structural functionalism by studying how social institutions maintain order, while Talcott Parsons later developed the theory further in the mid-20th century. Other notable figures include Robert Merton, who refined functionalist concepts with ideas like manifest and latent functions.

1. David Lewis: As a proponent of role functionalism, David Lewis argued that mental states are defined by their causal roles in cognitive processes. He emphasised the importance of understanding mental states in terms of their functions and relationships to other mental states. Lewis's work has significantly shaped the debate on functionalism by highlighting the role of causal relations in memory and mental processes.

2. Hilary Putnam: Hilary Putnam is known for his advocacy of realizer functionalism, which focuses on the physical realisations of mental states. He argued that mental states are not solely defined by their functional roles, but also by their physical properties. In educational contexts, this perspective influences how teachers understand student attention as both functional cognitive processes and physical brain states.

3. Jerry Fodor: Jerry Fodor is a key figure in functionalism who has contributed to the field through his arguments for the modularity of mind. As a proponent of role functionalism, Fodor emphasised the specialised functions of mental processes and their distinct roles in cognition. His work has played a significant role in shaping the debate on functionalism by highlighting the complexity and specificity of mental functions.

4. Ned Block: Ned Block is known for his criticisms of functionalism and his development of the absent qualia argument. Block has challenged functionalism by arguing that functional organisation alone cannot account for conscious experience. His work has contributed to debates about whether functional roles are sufficient to explain all aspects of mental states, particularly consciousness in educational settings.

These founding figures have collectively shaped functionalism into a robust theoretical framework that continues to influence both psychological research and educational practice. Their contributions demonstrate how mental processes serve adaptive functions, helping educators understand why certain learning behaviours emerge and persist in classroom environments.

Functionalist psychology and sociology offer powerful frameworks for understanding educational processes, institutional purposes, and student behaviour. By recognising that mental processes and social structures serve specific functions, educators can develop more effective teaching strategies and create learning environments that align with students' adaptive needs.

From a functionalist perspective, schools serve multiple interconnected purposes beyond academic instruction. Manifest functions, the intended, obvious purposes, include transmitting knowledge, developing skills, and providing credentials that sort students for future social roles. Teachers explicitly plan lessons, assess learning, and award qualifications to fulfil these manifest functions.

However, schools also perform crucial latent functions, unintended but socially important consequences. These include socialisation into cultural norms, provision of childcare enabling parental employment, creation of peer networks, and transmission of cultural values. Understanding these latent functions helps teachers recognise why certain institutional practices persist even when they seem inefficient or outdated from a purely academic perspective.

For example, the functionalist perspective illuminates why schools maintain rigid timetables, age-based cohorts, and standardised curricula. These structures serve latent functions of preparing students for industrial work rhythms, creating predictable childcare arrangements, and establishing common cultural reference points. Teachers who understand these multiple functions can make more informed decisions about when to work within existing structures and when to advocate for change.

Functionalist principles complement and inform various learning theories that teachers encounter in professional practice. The emphasis on adaptive behaviour connects naturally with constructivism, which views learning as active construction of knowledge to solve problems and understand experiences. Both perspectives recognise that learning serves purposes beyond mere information storage, it enables increasingly sophisticated adaptation to complex environments.

The functionalist question "What purpose does this behaviour serve?" proves particularly valuable when addressing challenging student behaviours. Rather than viewing challenging actions as mere rule violations requiring punishment, functionalist-informed teachers investigate what adaptive purpose the behaviour serves for the student. Is the student seeking attention, avoiding difficult work, gaining peer status, or expressing frustration with unclear expectations? Identifying the function enables teachers to address underlying needs rather than merely suppressing symptoms.

This functional approach to behaviour aligns with positive behaviour support frameworks used in contemporary schools. By teaching alternative behaviours that serve the same function more appropriately, teachers help students develop adaptive repertoires. For instance, a student who disrupts lessons to avoid challenging work might be taught to request help or break tasks into manageable steps, alternative strategies serving the same function of reducing anxiety without disrupting learning.

Functionalist insights translate into specific teaching practices that enhance student engagement and learning effectiveness. When planning lessons, teachers can explicitly consider what adaptive purposes the learning serves from students' perspectives. Making these purposes clear, through real-world applications, authentic projects, or connections to students' interests, increases motivation and meaningful engagement.

The functionalist emphasis on whole organisms adapting to environments also supports comprehensive teaching approaches. Rather than focusing narrowly on academic skills in isolation, effective teachers recognise that learning involves social, emotional, and physical dimensions. Creating classroom environments that support these multiple aspects of student functioning promotes more effective adaptation and deeper learning.

Assessment practices benefit from functionalist perspectives as well. Rather than viewing tests solely as measurement instruments, teachers can design assessments that serve multiple functions: providing feedback to guide learning, helping students recognise their progress, informing instructional adjustments, and developing metacognitive skills. Understanding assessment's multiple functions enables teachers to select appropriate methods for different purposes rather than relying on single approaches.

| Educational Function | Manifest (Intended) | Latent (Unintended) |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge Transmission | Teaching curriculum content and skills | Transmitting cultural values and middle-class norms |

| Socialisation | Developing cooperation and social skills | Training in obedience to authority and conformity |

| Social Selection | Awarding qualifications based on merit | Reproducing social class structures; credentialism |

| Childcare Provision | Supervising children during working hours | Enabling both parents to participate in labour force |

| Social Integration | Creating shared identity and community | Marginalising non-dominant cultures; assimilation pressure |

While functionalism originated over a century ago, its core principles remain relevant to contemporary educational challenges and innovations. Modern applications demonstrate how functionalist thinking adapts to new contexts while maintaining its emphasis on understanding systems through their purposes and functions.

The rise of educational technology offers new contexts for applying functionalist analysis. Rather than asking whether specific technologies are "good" or "bad" for learning, a functionalist approach examines what functions they serve and how effectively they support adaptive learning processes.

For example, learning management systems serve manifest functions of organising resources, tracking progress, and facilitating communication. However, they also perform latent functions such as increasing surveillance of student activity, standardising pedagogical approaches, and extending school time into home environments. Teachers who recognise these multiple functions can make more informed decisions about technology adoption and use.

The functionalist emphasis on mental processes serving adaptive purposes also illuminates debates about digital tools and cognitive development. Rather than viewing technologies like calculators or spell-checkers as simply "doing students' thinking for them," functionalist analysis asks what cognitive functions these tools support. When calculators free cognitive resources from computational procedures for higher-order problem-solving, they enhance rather than diminish mathematical thinking. Understanding these functional relationships helps teachers integrate technologies effectively.

Functionalist perspectives prove particularly valuable in inclusive educational contexts serving students with diverse learning needs. The functionalist question "What purpose does this behaviour serve?" becomes essential when supporting students with disabilities, challenging behaviours, or different developmental trajectories.

For students with autism spectrum conditions, repetitive behaviours that might appear non-functional often serve important self-regulation purposes, helping manage sensory input or reduce anxiety. Teachers who understand these adaptive functions can create environments that meet underlying needs while teaching alternative strategies when behaviours interfere with learning or social inclusion.

Similarly, functionalist analysis illuminates how different students may achieve similar learning outcomes through diverse pathways. Rather than insisting all students use identical methods, teachers can focus on whether different approaches serve the same adaptive functions of understanding concepts, solving problems, or demonstrating learning. This functional equivalence perspective supports differentiation and universal design for learning.

Contemporary emphasis on social-emotional learning (SEL) and student mental health reflects functionalist principles about education serving multiple adaptive purposes. Schools increasingly recognise that supporting emotional regulation, relationship skills, and psychological wellbeing functions as essential preparation for adaptive functioning in complex social environments.

From a functionalist perspective, SEL programmes serve both manifest functions (explicitly teaching emotion regulation and social skills) and latent functions (reducing behaviour problems, improving school climate, and addressing broader societal concerns about youth mental health). Understanding these multiple functions helps educators justify resource allocation and design comprehensive approaches.

The functionalist emphasis on adaptation also supports trauma-informed educational practices. Rather than viewing traumatised students' behaviours as intentional misbehaviour, trauma-informed teachers recognise these responses as adaptive strategies developed in threatening environments. While behaviours like hypervigilance or emotional withdrawal may have served protective functions in traumatic contexts, they become maladaptive in safe learning environments. Effective intervention involves teaching new adaptive responses appropriate to current contexts while recognising past adaptations made sense given students' experiences.

Functionalist analysis illuminates contemporary debates about educational accountability, testing, and school performance measures. While accountability systems' manifest function involves improving educational quality through measurement and comparison, they also serve latent functions including political legitimation of educational spending, market-based competition between schools, and standardisation of curriculum and pedagogy.

Teachers navigating accountability pressures benefit from understanding these multiple functions. Recognition that high-stakes testing serves purposes beyond measuring student learning, such as rationing access to higher education or demonstrating governmental action on educational quality, enables more critical engagement with testing regimes. Rather than accepting accountability measures uncritically or rejecting them entirely, functionalist-informed teachers can advocate for approaches that effectively serve intended purposes while minimising harmful unintended consequences.

The functionalist concept of dysfunction proves particularly relevant here. When accountability systems create perverse incentives, such as narrowing curriculum, teaching to tests, or excluding struggling students, they fail to serve their intended functions and may actively undermine educational quality. Identifying these dysfunctions enables advocacy for systemic reforms that better align structures with purposes.

In educational settings, functionalism provides a lens for understanding how schools operate as social systems serving multiple purposes beyond academic instruction. Teachers can apply functionalist principles to recognise that student behaviours, classroom routines, and institutional practices all serve specific functions in maintaining educational stability and promoting social cohesion.

From a functionalist perspective, schools perform several manifest functions including knowledge transmission, skill development, and academic credentialing. However, they also serve latent functions such as childcare, social sorting, and cultural transmission. Understanding these dual purposes helps teachers recognise why certain educational practices persist even when they may seem inefficient or outdated.

Robert Merton's concept of dysfunction is particularly relevant in educational contexts. When schools fail to serve their intended functions or create unintended negative consequences, teachers must identify these dysfunctions and work to address them. For example, rigid streaming systems may serve the function of academic differentiation but create dysfunctions through reduced expectations and social segregation.

The functionalist emphasis on social equilibrium also influences classroom management approaches. Teachers who understand functionalist principles recognise that challenging behaviour often serves a function for the student, whether seeking attention, avoiding difficult tasks, or maintaining social status. Effective interventions address these underlying functions rather than merely suppressing symptoms.

Merton's adaptation to strain theory offers valuable insights into student responses to academic pressure and social expectations. His five modes of adaptation help teachers understand diverse student reactions to educational goals and institutional means.

Conformist students accept both educational goals and legitimate means of achieving them, typically displaying conventional academic behaviour and following school rules. Innovation occurs when students accept educational goals but reject legitimate means, perhaps resorting to cheating or other unauthorised methods to achieve academic success.

Ritualism manifests when students abandon educational goals but continue following institutional means, going through the motions of schooling without genuine engagement or aspiration. Retreatism involves rejecting both goals and means, leading to disengagement and potential dropout behaviour. Finally, rebellion represents attempts to replace existing educational goals and means with alternative systems or approaches.

Teachers who recognise these adaptation patterns can develop more targeted interventions, addressing the underlying strain between culturally emphasised goals and available opportunities rather than simply managing surface behaviours.

| Adaptation Mode | Cultural Goals | Institutional Means | School Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conformity | Accepts | Accepts | Student studies diligently, follows rules, aims for qualifications |

| Innovation | Accepts | Rejects | Student wants high grades but resorts to cheating or plagiarism |

| Ritualism | Rejects | Accepts | Student attends and completes work mechanically without ambition |

| Retreatism | Rejects | Rejects | Student becomes disengaged, truant, or drops out entirely |

| Rebellion | Replaces with new goals | Replaces with new means | Student advocates for alternative education or radical reform |

While functionalism provides valuable insights into social and psychological processes, it faces significant criticisms including an over-emphasis on stability, neglect of conflict and change, and tendency towards conservative bias. Critics argue that functionalist approaches may overlook power imbalances, inequality, and the need for educational reform by focusing primarily on system maintenance rather than transformation.

One major criticism centres on functionalism's assumption that existing social arrangements serve positive purposes. In educational contexts, this can lead to uncritical acceptance of practices that may perpetuate inequality or limit student potential. For example, functionalist explanations of educational streaming may overlook how such systems reproduce social class divisions rather than promoting meritocracy.

The theory's emphasis on consensus and stability has been challenged by conflict theorists who highlight how schools may serve the interests of dominant groups rather than society as a whole. Pierre Bourdieu's work on cultural capital demonstrates how seemingly neutral educational practices can disadvantage students from certain backgrounds, contradicting functionalist assumptions about equal opportunity.

Contemporary educational research increasingly recognises the need to balance functionalist insights with critical perspectives that examine power, inequality, and social justice. Teachers benefit from understanding both how educational systems function and how they might be transformed to better serve all students.

Functionalism remains a valuable theoretical framework for understanding both psychological processes and social institutions, offering teachers practical insights into why behaviours and educational practices persist. By recognising that mental processes serve adaptive functions and that schools operate as complex social systems, educators can develop more effective approaches to teaching, learning, and classroom management.

The functionalist emphasis on purpose and adaptation helps teachers understand that student behaviours, even challenging ones, typically serve specific functions for the individual. This perspective encourages educators to look beyond surface symptoms to identify underlying needs and develop interventions that address root causes rather than merely managing consequences.

However, effective educational practice requires balancing functionalist insights with critical awareness of power, inequality, and the need for change. While understanding how educational systems maintain stability is valuable, teachers must also remain committed to challenging practices that limit student potential or perpetuate injustice. The most effective educators combine functionalist understanding of system purposes with critical examination of whether those purposes truly serve all students' needs.

For educators interested in exploring functionalism further, the following academic sources provide valuable insights into both theoretical foundations and practical applications:

These resources offer both theoretical grounding and practical applications that can enhance understanding of functionalist principles in educational contexts. Teachers are encouraged to critically engage with these perspectives while considering their implications for contemporary classroom practice.

What is the main difference between functionalism in psychology and sociology?

Functionalism in psychology focuses on how mental processes and behaviours help individuals adapt to their environment and serve specific purposes for survival and wellbeing. In contrast, sociological functionalism examines how social institutions like schools, families, and governments work together to maintain social stability and meet society's needs. Both approaches emphasise understanding systems through their functions, but psychology looks at individual adaptation while sociology examines societal cohesion.

How can teachers apply functionalist theory in their classrooms?

Teachers can use functionalist principles by recognising that student behaviours serve specific functions, even when they appear challenging. Instead of simply stopping unwanted behaviour, effective teachers identify what function the behaviour serves (attention-seeking, task avoidance, social connection) and provide alternative ways to meet those needs. Additionally, understanding the multiple functions schools serve helps teachers balance academic instruction with social development and cultural transmission.

What are manifest and latent functions in education?

Manifest functions are the intended, obvious purposes of educational institutions, such as teaching literacy, numeracy, and subject knowledge. Latent functions are the unintended but important consequences, including socialisation, childcare provision, social sorting, and cultural transmission. For example, school assemblies have the manifest function of sharing information but the latent function of building community identity and reinforcing shared values.

Why is functionalism criticised in educational settings?

Critics argue that functionalism can justify existing inequalities by suggesting that all social arrangements serve necessary purposes. In education, this might lead to accepting practices like streaming or standardised testing without questioning whether they truly benefit all students. Functionalism may also overlook how schools can perpetuate social class differences and fail to challenge systems that disadvantage certain groups of learners.

How does Merton's strain theory apply to student achievement?

Merton's theory explains different student responses to academic pressure through five adaptation modes. Conformist students accept both educational goals and legitimate means of achieving them. Innovators want academic success but may cheat or use unauthorised methods. Ritualists follow school routines without caring about achievement. Retreatists disengage from both goals and means, while rebels seek to replace existing educational systems with alternatives. Understanding these patterns helps teachers provide appropriate support for different student needs.

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/functionalism#article","headline":"Functionalism in Psychology and Sociology: How Systems Serve Society","description":"Explore functionalism across psychology and sociology. Learn how this perspective explains behaviour in terms of purpose and how it views education as...","datePublished":"2024-01-22T16:47:38.768Z","dateModified":"2026-01-26T10:09:32.212Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/functionalism"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/695033a80761a6689892d9db_xkpd5q.webp","wordCount":5857},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/functionalism#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"Functionalism in Psychology and Sociology: How Systems Serve Society","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/functionalism"}]}]}