Change Theories

Explore the world of change theories. Understand their role in organizational development, personal growth, and societal change.

Change theories are a complex amalgamation of various models and perspectives that aim to explain and facilitate the process of change in individual and collective behaviours. These theories, often grounded in research-based instructional strategies, take into account a myriad of personal and contextual factors that influence the process of change.

One of the key theories in this domain is the transtheoretical model, which posits that change is a process that occurs over time, involving progress through a series of stages. This model is often used in health education to facilitate behavioural change, and has been adapted for use in educational settings to promote innovation in education.

Another important perspective is the integrative model, which combines elements from various theories to provide a comprehensive framework for understanding and facilitating change. This model takes into account the interplay between individual behaviour, environmental factors, and the broader social context, highlighting the complexity of the change process.

The social learning theory and self-efficacy theory, both rooted in cognitive theory, also play a crucial role in understanding change. These theories emphasise the importance of observational learning, self-belief, and the influence of social context in shaping behaviour.

According to a study titled "Digital curriculum resources in mathematics education: foundations for change", the shift from static print to dynamic, interactive digital curriculum resources (DCR) has the potential to support different forms of personalised learningand interaction with resources.

The study suggests that DCR offer opportunities for change in the design and use of educational resources, their quality, and the processes related to teacher-student interactions.

As an example, consider a school that is implementing a new digital learning platform. The success of this change would depend on a variety of factors, including the teachers' comfort with technology, the students' ability to adapt to new learning methods, the school's infrastructure, and the support from the wider school community.

As noted by educational researcher Jean Piaget, "The principal goal of education is to create individuals who are capable of doing new things, not simply of repeating what other generations have done." This quote underscores the importance of embracing change in education, and the role of change theories in facilitating this process.

In terms of statistics, a study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences found that neighborhoods densely populated by college-educated adults are more likely to experience physical improvements, a finding that supports theories of human capital agglomeration. This statistic highlights the impact of environmental factors on behavioural change, a key element of change theories.

Change theories provide a valuable framework for understanding and facilitating change in educational settings. By taking into account a range of personal and contextual factors, these theories can help educators design and implement effective strategies for promoting innovation and improving educational outcomes.

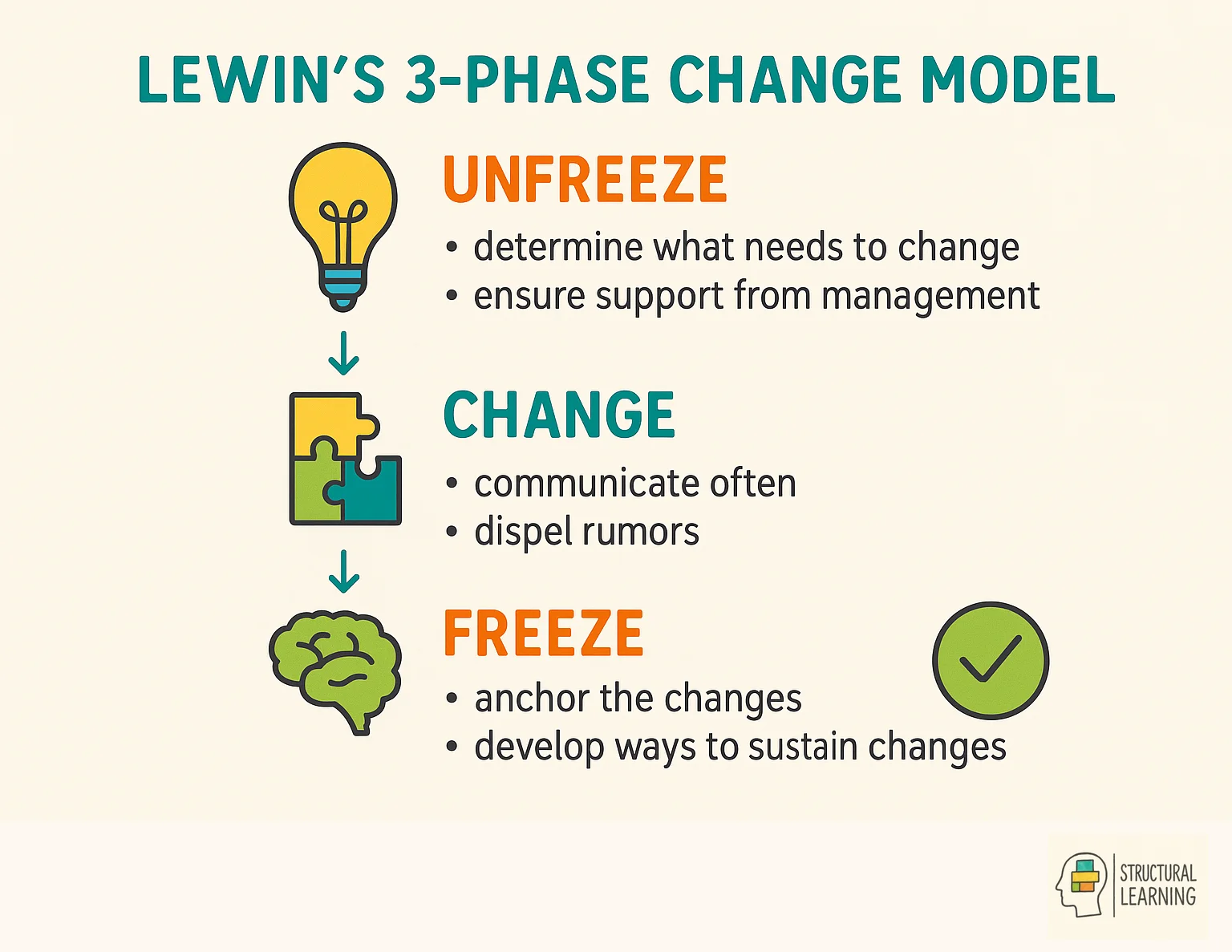

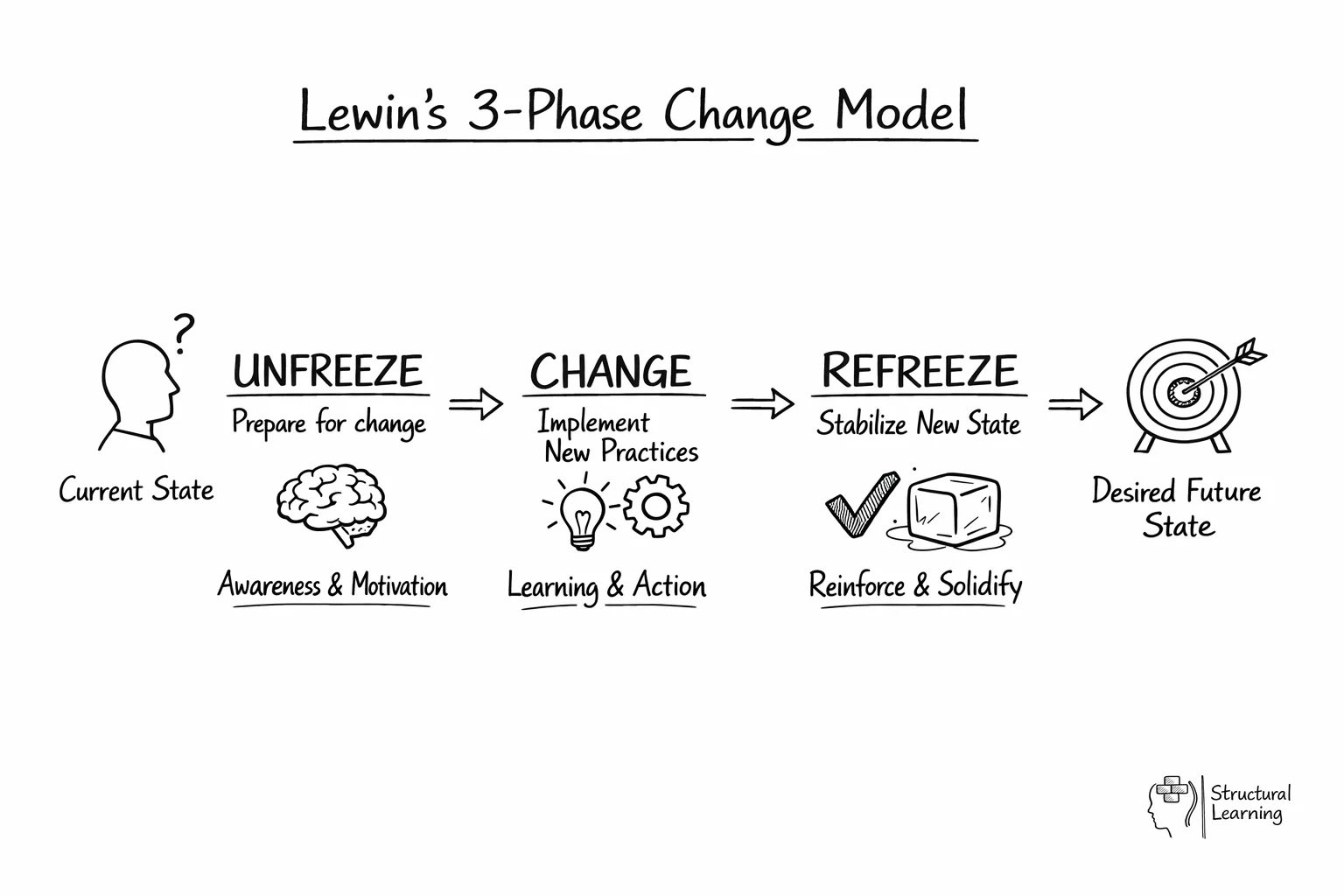

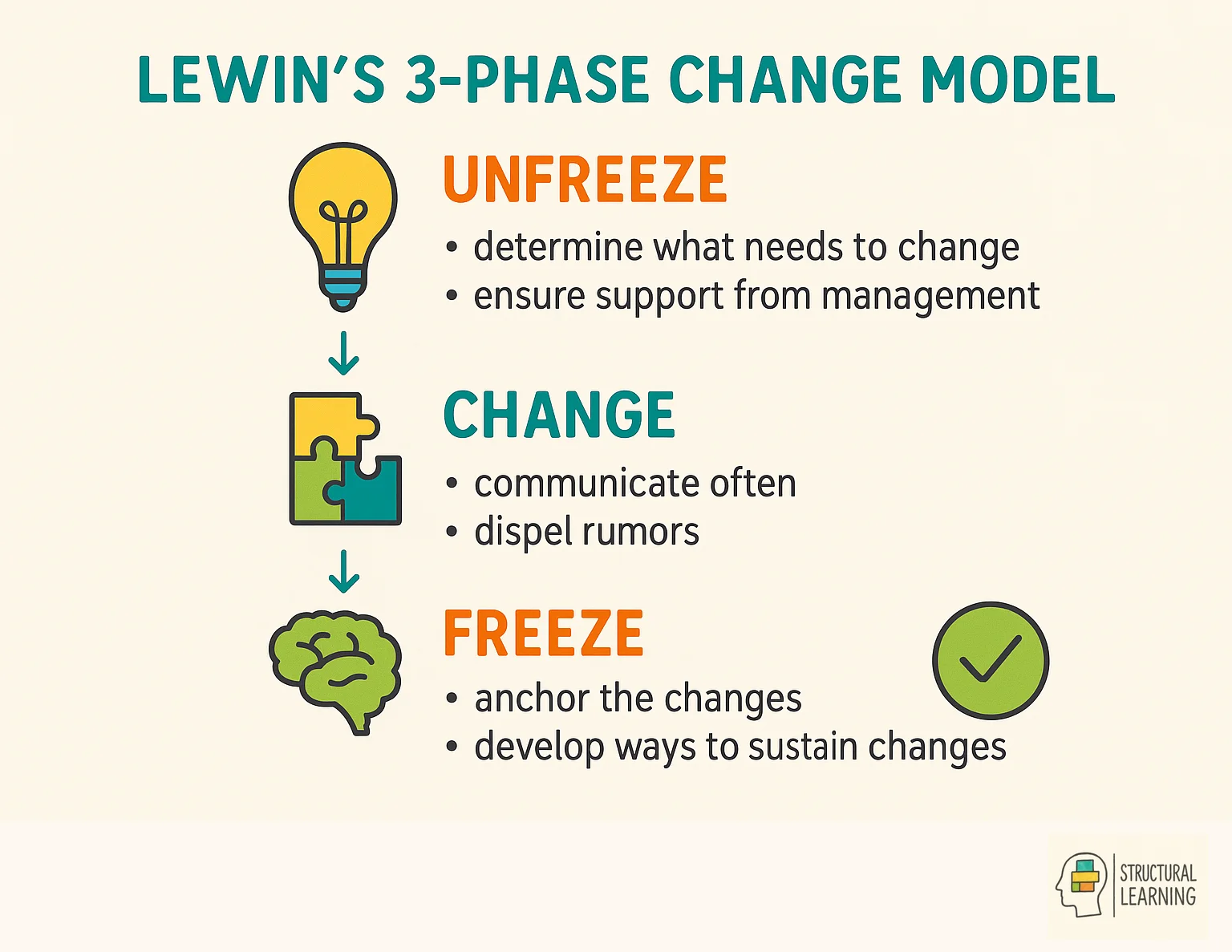

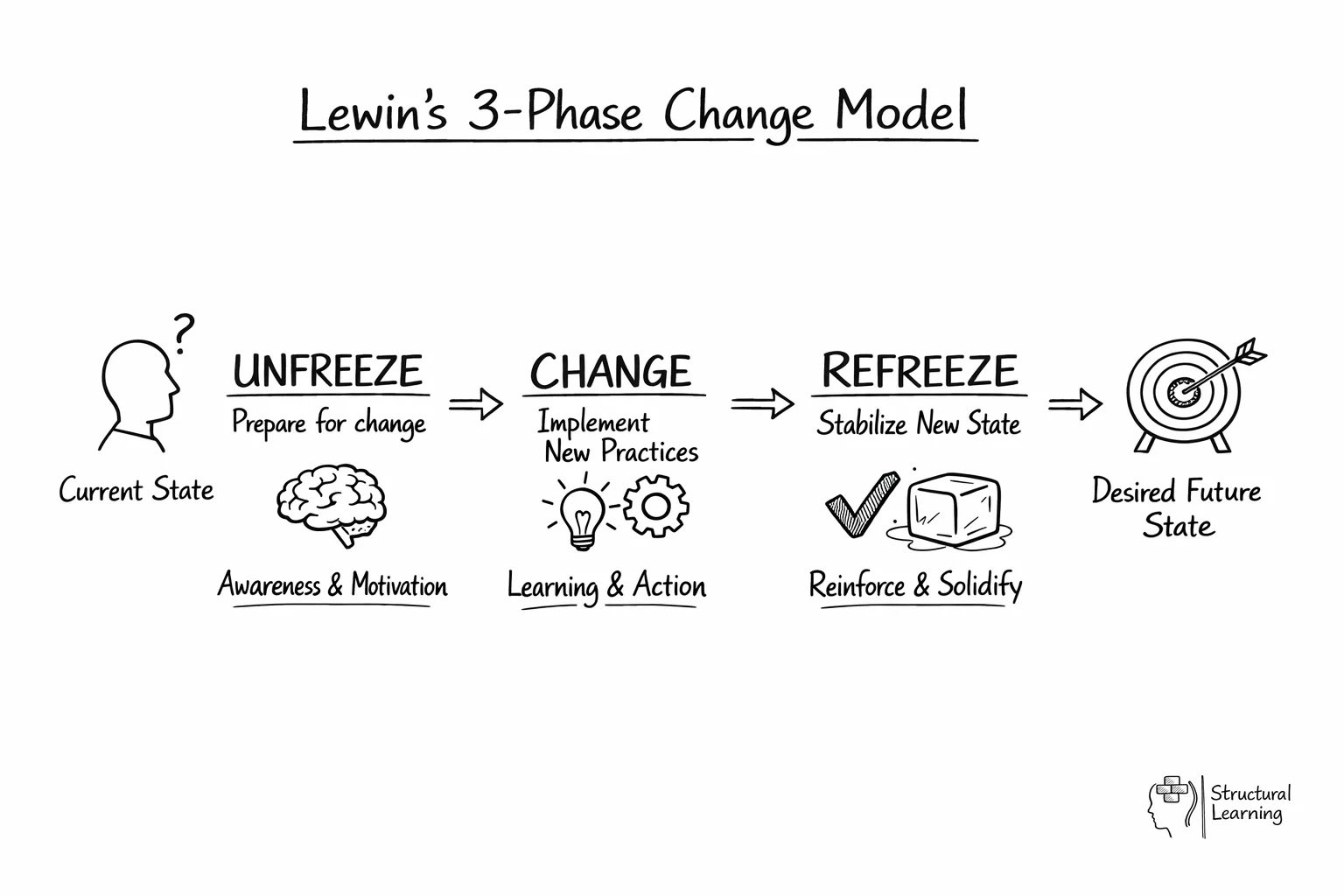

Lewin's Change Theory consists of three phases: unfreeze (preparing for change), change (implementing new practices), and refreeze (stabilizing the new state). This model explains why many initiatives fail when organisations skip the crucial unfreezing stage where people need to understand why current practices must change. Schools successfully using this model spend significant time building urgency and buy-in before implementing changes.

Lewin's Change Theory, also known as the three-phase model, is a prominent framework in organisational development. This model, developed by Kurt Lewin, simplifies the process of change into three distinct phases: unfreeze, change, and refreeze.

The first phase, unfreeze, involves a deep understanding of the current state of the system. It requires the recognition of existing behavioural patterns and beliefs that are obstructing progress. This phase aims to create a sense of dissatisfaction with the status quo, motivating individuals and the organisation to embrace change.

The second phase, change, is focused on implementing the desired changes. This phase can be challenging as it requires overcoming resistance to change, addressing employee concerns, and ensuring proper communication and training. Effective engagement strategies are crucial during this phase to maintain motivation throughout the transition.

The final phase, refreeze, aims to solidify the new changes and establish them as the new status quo. This phase involves reinforcing the new behaviours and processes, providing ongoing support, and ensuring that the changes become a permanent part of the organisation's culture and operations. Positive reinforcement techniques can be particularly effective in helping establish these new patterns.

Lewin's Change Theory is highly regarded for its practicality and ability to break down big changes into more manageable stages. By following this three-phase model, organisations can effectively analyse, implement, and solidify changes, ultimately improving their overall performance and adaptability. This approach also supports self-regulation as individuals learn to adapt to new processes, while building organisational resili ence through structured change management.

The strength of Lewin's model lies in its recognition that successful change requires more than simply implementing new procedures or policies. Each stage serves a distinct psychological and practical purpose. During the unfreezing stage, leaders must help individuals recognise why current methods are inadequate and create a sense of urgency for change. This might involve sharing data about student outcomes, presenting research on more effective practices, or facilitating discussions about current challenges.

The change stage requires careful planning and support systems. Kurt Lewin emphasised that people need clear guidance, training, and resources during this transition period. In educational contexts, this might include professional development sessions, mentoring programmes, or pilot implementations that allow staff to experiment with new approaches safely.

The refreezing stage often receives insufficient attention, yet for long-term success. Without proper reinforcement, individuals tend to revert to familiar behaviours. Effective refreezing involves updating policies, adjusting reward systems, celebrating successes, and ensuring new practices become embedded in organisational culture. Regular monitoring and feedback loops help maintain momentum and identify areas requiring further adjustment.

John Kotter's eight-step process for leading change provides educational leaders with a systematic framework for implementing lasting organisational transformation. Developed through extensive research into successful change initiatives, Kotter's model emphasises the critical importance of building momentum and maintaining engagement throughout the change process. The eight sequential steps begin with creating urgency and forming a guiding coalition, then progress through developing a vision, communicating change, helping action, generating short-term wins, sustaining acceleration, and finally instituting change within the organisational culture.

In educational settings, this model proves particularly effective for large-scale initiatives such as curriculum reform, technology integration, or pedagogical shifts. For instance, when implementing a new assessment strategy, school leaders must first help staff understand why change is necessary, then assemble a committed team of early adopters who can champion the initiative. The model's emphasis on quick wins is especially valuable in schools, where demonstrating early success can build teacher confidence and student engagement.

The sequential nature of Kotter's steps ensures that educational leaders address both the technical and adaptive challenges of change. By focusing on communication, empowerment, and cultural embedding, the model helps prevent the common pitfall of superficial implementation that often plagues educational reform efforts.

The ADKAR model, developed by Jeff Hiatt, provides a structured framework for understanding individual change through five sequential building blocks: Awareness, Desire, Knowledge, Ability, and Reinforcement. Unlike organisational change theories that focus on systems and structures, ADKAR centres on the personal journey each individual must navigate when adopting new practices or behaviours. This makes it particularly valuable in educational settings, where lasting change depends fundamentally on teachers, students, and staff embracing new approaches at a personal level.

Each element of ADKAR represents a prerequisite for the next stage. Awareness of why change is needed must precede the desire to participate in change. Knowledge of how to change follows desire, whilst the ability to implement new skills and behaviours builds upon knowledge. Finally, reinforcement ensures changes are sustained over time. Educational leaders can use this model diagnostically, identifying where individuals might be struggling in their change journey and providing targeted support accordingly.

In practice, a head teacher implementing a new assessment policy might use ADKAR to support staff transition. This could involve creating awareness through data presentations, building desire by connecting the change to teachers' values about student success, providing knowledge through professional development sessions, developing ability through coaching and practice opportunities, and establishing reinforcement through recognition systems and ongoing feedback mechanisms.

William Bridges' Transition Model offers a uniquely human-centred approach to understanding change by distinguishing between change (external events) and transition (internal psychological processes). Unlike other change theories that focus primarily on organisational structures, Bridges emphasises that successful change depends on helping individuals navigate three distinct psychological stages: endings (letting go of old ways), the neutral zone (a confusing in-between period), and new beginnings (embracing new approaches). This framework proves particularly valuable in educational settings where change affects both staff wellbeing and student learning outcomes.

The model's strength lies in recognising that people must psychologically 'end' their attachment to previous practices before genuinely adopting new ones. In schools, this might involve teachers releasing familiar teaching methods or students adjusting to new assessment formats. The neutral zone, whilst uncomfortable, represents a crucial creative space where innovation emerges, though it requires careful support and clear communication from leaders.

Educational leaders can apply this model by explicitly acknowledging what staff and students are losing during change initiatives, providing structured support during uncertain transition periods, and celebrating meaningful new beginnings. For example, when implementing new curriculum standards, successful schools create opportunities for teachers to process their concerns about abandoned practices whilst gradually building confidence with effective approaches.

Elisabeth Kübler-Ross's Change Curve, originally developed to understand grief responses, provides invaluable insights into how individuals navigate educational change. The model identifies distinct emotional stages: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. In educational settings, staff facing new curricula, technology implementations, or organisational restructuring often experience these predictable emotional responses, making the Change Curve essential for understanding and supporting colleagues through transitions.

Educational leaders can use this framework to anticipate resistance and provide appropriate support at each stage. During the denial phase, teachers may dismiss new initiatives as temporary fads, whilst the anger stage often manifests as vocal criticism in staff meetings. The bargaining phase sees attempts to modify or delay implementation, followed by the depression stage where motivation drops significantly. Understanding these patterns helps leaders respond with empathy rather than frustration.

Practical application involves creating support structures tailored to each stage. Provide clear communication and rationale during denial, offer safe spaces for venting concerns during anger, involve staff in adaptation decisions during bargaining, and celebrate small wins to combat low morale. Recognising that reaching acceptance takes time allows leaders to maintain realistic expectations whilst supporting their teams through inevitable emotional responses to change.

Effective implementation of change theories in educational settings requires a systematic approach that considers both individual and organisational factors. Kotter's eight-step change model proves particularly valuable for school-wide initiatives, beginning with creating urgency around student achievement gaps and building coalitions of teachers, leaders, and parents. Meanwhile, at the classroom level, Rogers' diffusion of innovation theory helps educators understand why some colleagues readily adopt new teaching technologies whilst others remain hesitant, enabling more targeted professional development strategies.

The ADKAR model offers a practical framework for supporting individual teachers through change, addressing awareness of why change is needed, desire to participate, knowledge of how to change, ability to implement new skills, and reinforcement to sustain progress. School leaders can apply this systematically by conducting staff surveys to identify where individuals sit on each dimension, then tailoring support accordingly through mentoring programmes, collaborative planning time, and celebration of early wins.

In practice, successful educational change often combines multiple theories. A secondary school implementing inquiry-based learning might use Fullan's change forces to build collaborative cultures, apply Bridges' transition model to help staff navigate the emotional journey from traditional teaching methods, and utilise social cognitive theory to provide observational learning opportunities through peer demonstration lessons and reflective practice sessions.

Selecting the most appropriate change theory requires careful consideration of your specific educational context, organisational culture, and desired outcomes. Kotter's eight-step process proves particularly effective for large-scale institutional transformations, such as implementing new curriculum frameworks across entire school districts. In contrast, Lewin's three-stage model offers a more streamlined approach for smaller-scale changes, making it ideal for departmental initiatives or individual classroom innovations.

The complexity and urgency of your change initiative should also guide your theoretical choice. Systems thinking approaches work exceptionally well when addressing interconnected challenges that span multiple stakeholders, whilst behavioural change theories like those proposed by Prochaska and DiClemente excel when focusing on individual teacher or student transformation. Consider your organisation's readiness for change: established institutions with strong hierarchies may benefit from structured, top-down approaches, whereas collaborative environments might thrive with participatory change models.

Successful educational leaders often combine elements from multiple theories rather than rigidly adhering to a single framework. For instance, you might use Lewin's unfreezing stage to prepare stakeholders, incorporate Kotter's coalition-building strategies during implementation, and apply continuous improvement principles for sustainability. The key lies in matching theoretical strengths to your specific challenges whilst remaining flexible enough to adapt your approach as circumstances evolve.

Change theories are a complex amalgamation of various models and perspectives that aim to explain and facilitate the process of change in individual and collective behaviours. These theories, often grounded in research-based instructional strategies, take into account a myriad of personal and contextual factors that influence the process of change.

One of the key theories in this domain is the transtheoretical model, which posits that change is a process that occurs over time, involving progress through a series of stages. This model is often used in health education to facilitate behavioural change, and has been adapted for use in educational settings to promote innovation in education.

Another important perspective is the integrative model, which combines elements from various theories to provide a comprehensive framework for understanding and facilitating change. This model takes into account the interplay between individual behaviour, environmental factors, and the broader social context, highlighting the complexity of the change process.

The social learning theory and self-efficacy theory, both rooted in cognitive theory, also play a crucial role in understanding change. These theories emphasise the importance of observational learning, self-belief, and the influence of social context in shaping behaviour.

According to a study titled "Digital curriculum resources in mathematics education: foundations for change", the shift from static print to dynamic, interactive digital curriculum resources (DCR) has the potential to support different forms of personalised learningand interaction with resources.

The study suggests that DCR offer opportunities for change in the design and use of educational resources, their quality, and the processes related to teacher-student interactions.

As an example, consider a school that is implementing a new digital learning platform. The success of this change would depend on a variety of factors, including the teachers' comfort with technology, the students' ability to adapt to new learning methods, the school's infrastructure, and the support from the wider school community.

As noted by educational researcher Jean Piaget, "The principal goal of education is to create individuals who are capable of doing new things, not simply of repeating what other generations have done." This quote underscores the importance of embracing change in education, and the role of change theories in facilitating this process.

In terms of statistics, a study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences found that neighborhoods densely populated by college-educated adults are more likely to experience physical improvements, a finding that supports theories of human capital agglomeration. This statistic highlights the impact of environmental factors on behavioural change, a key element of change theories.

Change theories provide a valuable framework for understanding and facilitating change in educational settings. By taking into account a range of personal and contextual factors, these theories can help educators design and implement effective strategies for promoting innovation and improving educational outcomes.

Lewin's Change Theory consists of three phases: unfreeze (preparing for change), change (implementing new practices), and refreeze (stabilizing the new state). This model explains why many initiatives fail when organisations skip the crucial unfreezing stage where people need to understand why current practices must change. Schools successfully using this model spend significant time building urgency and buy-in before implementing changes.

Lewin's Change Theory, also known as the three-phase model, is a prominent framework in organisational development. This model, developed by Kurt Lewin, simplifies the process of change into three distinct phases: unfreeze, change, and refreeze.

The first phase, unfreeze, involves a deep understanding of the current state of the system. It requires the recognition of existing behavioural patterns and beliefs that are obstructing progress. This phase aims to create a sense of dissatisfaction with the status quo, motivating individuals and the organisation to embrace change.

The second phase, change, is focused on implementing the desired changes. This phase can be challenging as it requires overcoming resistance to change, addressing employee concerns, and ensuring proper communication and training. Effective engagement strategies are crucial during this phase to maintain motivation throughout the transition.

The final phase, refreeze, aims to solidify the new changes and establish them as the new status quo. This phase involves reinforcing the new behaviours and processes, providing ongoing support, and ensuring that the changes become a permanent part of the organisation's culture and operations. Positive reinforcement techniques can be particularly effective in helping establish these new patterns.

Lewin's Change Theory is highly regarded for its practicality and ability to break down big changes into more manageable stages. By following this three-phase model, organisations can effectively analyse, implement, and solidify changes, ultimately improving their overall performance and adaptability. This approach also supports self-regulation as individuals learn to adapt to new processes, while building organisational resili ence through structured change management.

The strength of Lewin's model lies in its recognition that successful change requires more than simply implementing new procedures or policies. Each stage serves a distinct psychological and practical purpose. During the unfreezing stage, leaders must help individuals recognise why current methods are inadequate and create a sense of urgency for change. This might involve sharing data about student outcomes, presenting research on more effective practices, or facilitating discussions about current challenges.

The change stage requires careful planning and support systems. Kurt Lewin emphasised that people need clear guidance, training, and resources during this transition period. In educational contexts, this might include professional development sessions, mentoring programmes, or pilot implementations that allow staff to experiment with new approaches safely.

The refreezing stage often receives insufficient attention, yet for long-term success. Without proper reinforcement, individuals tend to revert to familiar behaviours. Effective refreezing involves updating policies, adjusting reward systems, celebrating successes, and ensuring new practices become embedded in organisational culture. Regular monitoring and feedback loops help maintain momentum and identify areas requiring further adjustment.

John Kotter's eight-step process for leading change provides educational leaders with a systematic framework for implementing lasting organisational transformation. Developed through extensive research into successful change initiatives, Kotter's model emphasises the critical importance of building momentum and maintaining engagement throughout the change process. The eight sequential steps begin with creating urgency and forming a guiding coalition, then progress through developing a vision, communicating change, helping action, generating short-term wins, sustaining acceleration, and finally instituting change within the organisational culture.

In educational settings, this model proves particularly effective for large-scale initiatives such as curriculum reform, technology integration, or pedagogical shifts. For instance, when implementing a new assessment strategy, school leaders must first help staff understand why change is necessary, then assemble a committed team of early adopters who can champion the initiative. The model's emphasis on quick wins is especially valuable in schools, where demonstrating early success can build teacher confidence and student engagement.

The sequential nature of Kotter's steps ensures that educational leaders address both the technical and adaptive challenges of change. By focusing on communication, empowerment, and cultural embedding, the model helps prevent the common pitfall of superficial implementation that often plagues educational reform efforts.

The ADKAR model, developed by Jeff Hiatt, provides a structured framework for understanding individual change through five sequential building blocks: Awareness, Desire, Knowledge, Ability, and Reinforcement. Unlike organisational change theories that focus on systems and structures, ADKAR centres on the personal journey each individual must navigate when adopting new practices or behaviours. This makes it particularly valuable in educational settings, where lasting change depends fundamentally on teachers, students, and staff embracing new approaches at a personal level.

Each element of ADKAR represents a prerequisite for the next stage. Awareness of why change is needed must precede the desire to participate in change. Knowledge of how to change follows desire, whilst the ability to implement new skills and behaviours builds upon knowledge. Finally, reinforcement ensures changes are sustained over time. Educational leaders can use this model diagnostically, identifying where individuals might be struggling in their change journey and providing targeted support accordingly.

In practice, a head teacher implementing a new assessment policy might use ADKAR to support staff transition. This could involve creating awareness through data presentations, building desire by connecting the change to teachers' values about student success, providing knowledge through professional development sessions, developing ability through coaching and practice opportunities, and establishing reinforcement through recognition systems and ongoing feedback mechanisms.

William Bridges' Transition Model offers a uniquely human-centred approach to understanding change by distinguishing between change (external events) and transition (internal psychological processes). Unlike other change theories that focus primarily on organisational structures, Bridges emphasises that successful change depends on helping individuals navigate three distinct psychological stages: endings (letting go of old ways), the neutral zone (a confusing in-between period), and new beginnings (embracing new approaches). This framework proves particularly valuable in educational settings where change affects both staff wellbeing and student learning outcomes.

The model's strength lies in recognising that people must psychologically 'end' their attachment to previous practices before genuinely adopting new ones. In schools, this might involve teachers releasing familiar teaching methods or students adjusting to new assessment formats. The neutral zone, whilst uncomfortable, represents a crucial creative space where innovation emerges, though it requires careful support and clear communication from leaders.

Educational leaders can apply this model by explicitly acknowledging what staff and students are losing during change initiatives, providing structured support during uncertain transition periods, and celebrating meaningful new beginnings. For example, when implementing new curriculum standards, successful schools create opportunities for teachers to process their concerns about abandoned practices whilst gradually building confidence with effective approaches.

Elisabeth Kübler-Ross's Change Curve, originally developed to understand grief responses, provides invaluable insights into how individuals navigate educational change. The model identifies distinct emotional stages: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. In educational settings, staff facing new curricula, technology implementations, or organisational restructuring often experience these predictable emotional responses, making the Change Curve essential for understanding and supporting colleagues through transitions.

Educational leaders can use this framework to anticipate resistance and provide appropriate support at each stage. During the denial phase, teachers may dismiss new initiatives as temporary fads, whilst the anger stage often manifests as vocal criticism in staff meetings. The bargaining phase sees attempts to modify or delay implementation, followed by the depression stage where motivation drops significantly. Understanding these patterns helps leaders respond with empathy rather than frustration.

Practical application involves creating support structures tailored to each stage. Provide clear communication and rationale during denial, offer safe spaces for venting concerns during anger, involve staff in adaptation decisions during bargaining, and celebrate small wins to combat low morale. Recognising that reaching acceptance takes time allows leaders to maintain realistic expectations whilst supporting their teams through inevitable emotional responses to change.

Effective implementation of change theories in educational settings requires a systematic approach that considers both individual and organisational factors. Kotter's eight-step change model proves particularly valuable for school-wide initiatives, beginning with creating urgency around student achievement gaps and building coalitions of teachers, leaders, and parents. Meanwhile, at the classroom level, Rogers' diffusion of innovation theory helps educators understand why some colleagues readily adopt new teaching technologies whilst others remain hesitant, enabling more targeted professional development strategies.

The ADKAR model offers a practical framework for supporting individual teachers through change, addressing awareness of why change is needed, desire to participate, knowledge of how to change, ability to implement new skills, and reinforcement to sustain progress. School leaders can apply this systematically by conducting staff surveys to identify where individuals sit on each dimension, then tailoring support accordingly through mentoring programmes, collaborative planning time, and celebration of early wins.

In practice, successful educational change often combines multiple theories. A secondary school implementing inquiry-based learning might use Fullan's change forces to build collaborative cultures, apply Bridges' transition model to help staff navigate the emotional journey from traditional teaching methods, and utilise social cognitive theory to provide observational learning opportunities through peer demonstration lessons and reflective practice sessions.

Selecting the most appropriate change theory requires careful consideration of your specific educational context, organisational culture, and desired outcomes. Kotter's eight-step process proves particularly effective for large-scale institutional transformations, such as implementing new curriculum frameworks across entire school districts. In contrast, Lewin's three-stage model offers a more streamlined approach for smaller-scale changes, making it ideal for departmental initiatives or individual classroom innovations.

The complexity and urgency of your change initiative should also guide your theoretical choice. Systems thinking approaches work exceptionally well when addressing interconnected challenges that span multiple stakeholders, whilst behavioural change theories like those proposed by Prochaska and DiClemente excel when focusing on individual teacher or student transformation. Consider your organisation's readiness for change: established institutions with strong hierarchies may benefit from structured, top-down approaches, whereas collaborative environments might thrive with participatory change models.

Successful educational leaders often combine elements from multiple theories rather than rigidly adhering to a single framework. For instance, you might use Lewin's unfreezing stage to prepare stakeholders, incorporate Kotter's coalition-building strategies during implementation, and apply continuous improvement principles for sustainability. The key lies in matching theoretical strengths to your specific challenges whilst remaining flexible enough to adapt your approach as circumstances evolve.

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/change-theories#article","headline":"Change Theories","description":"Explore the world of change theories. Understand their role in organizational development, personal growth, and societal change. ","datePublished":"2023-07-14T16:24:13.268Z","dateModified":"2026-01-26T10:09:32.212Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/change-theories"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/695240cb7923951d43c5d995_695240c9b6de1b1ad3d3d0dd_change-theories-infographic.webp","wordCount":3435},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/change-theories#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"Change Theories","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/change-theories"}]}]}