Metacognition for SEND and Neurodivergent Students

How to teach metacognition to SEND and neurodivergent pupils. Visual supports, adapted scaffolding, and evidence-based strategies that work in inclusive classrooms.

Neurodivergent students, including those with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), ADHD, dyslexia, and other specific learning differences, face unique challenges in educational settings. Research increasingly shows that these students benefit significantly more from explicit metacognitive instruction than their neurotypical peers. This thorough guideexplores how teachers can use metacognitive strategies to support neurodivergent learners, helping them develop self-awareness, self-regulation, and independent learning skills that are essential for long-term academic success.

| Challenge Area | Common Difficulty | Metacognitive Support | Practical Adaptation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Executive Function | Planning and organisation | Explicit teaching of strategies | Visual checklists and prompts |

| Working Memory | Holding information | External memory aids | Note-taking scaffolds |

| Self-Regulation | Managing emotions/behaviour | Emotion identification tools | Calm-down strategies |

| Attention | Sustaining focus | Self-monitoring techniques | Timers and breaks |

| Flexibility | Adapting to change | Preparation and preview | Visual schedules |

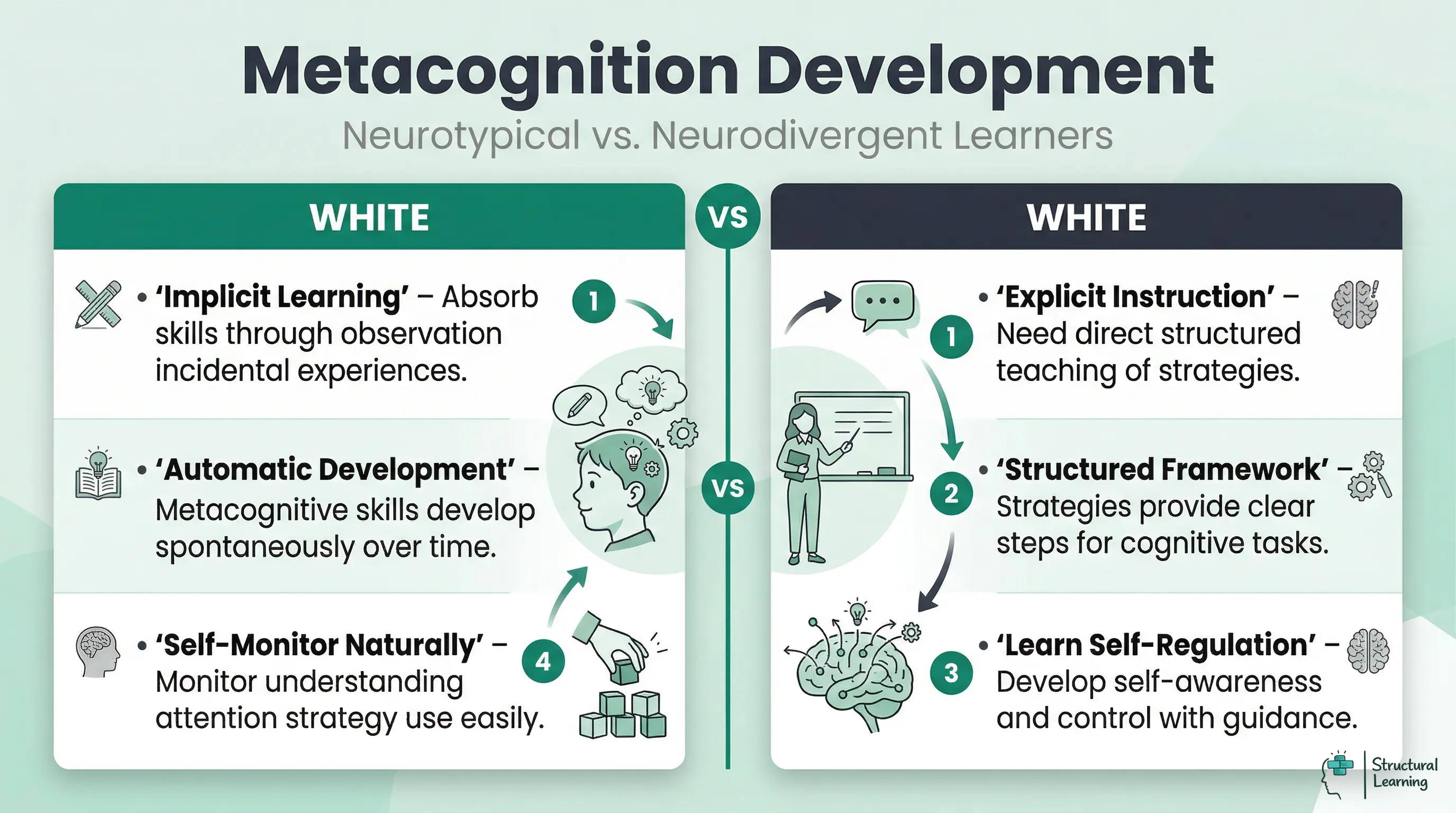

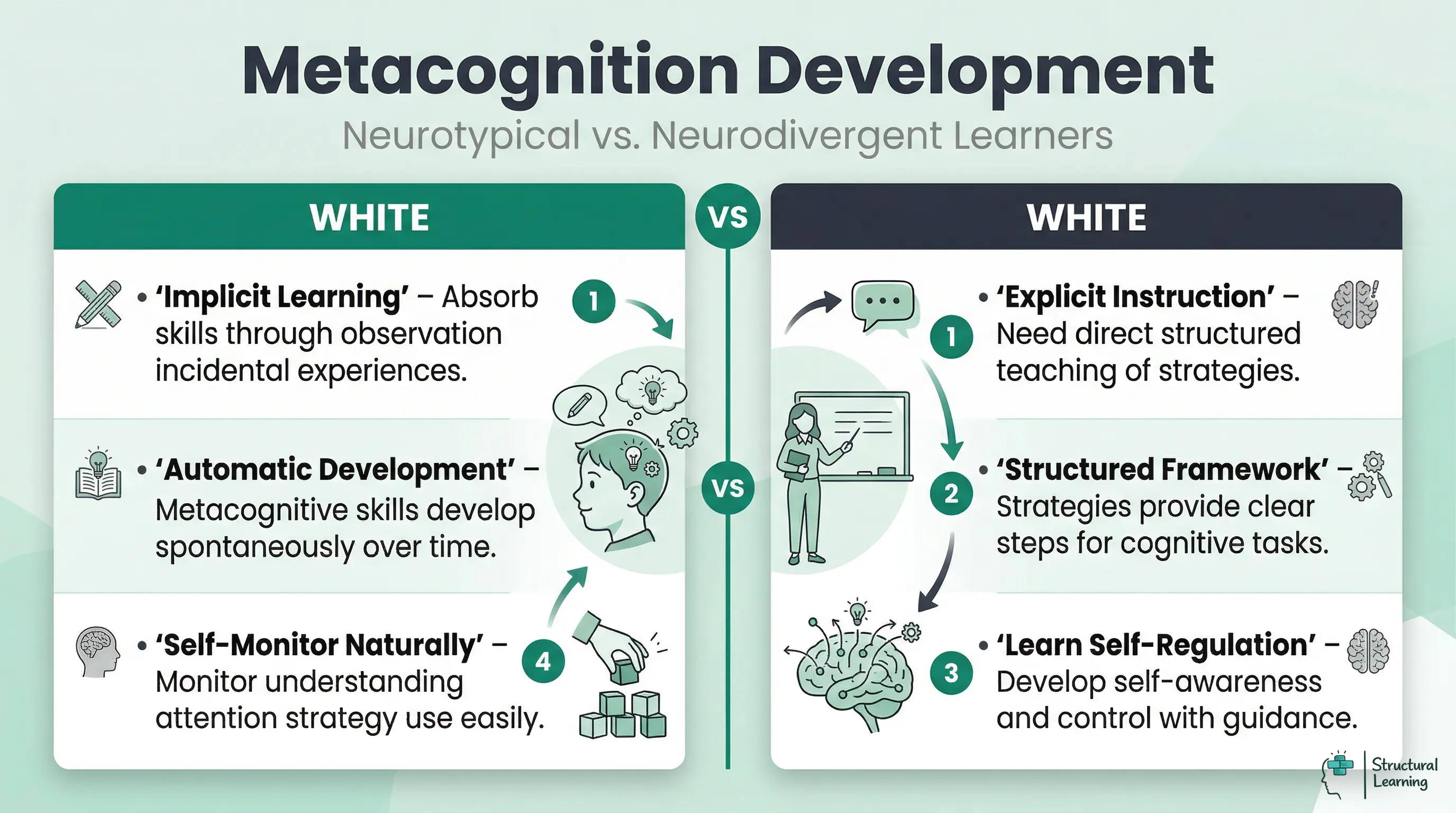

Metacognition, or "thinking about thinking", involves awareness and regulation of one's own cognitive processes. For neurodivergent learners, metacognitive strategies provide a structured framework for navigating the cognitive demands of learning that neurotypical students may develop implicitly.

Research from Whitebread and Pino-Pasternak (2010) demonstrates that children with learning difficulties show significantly greater gains from metacognitive instruction than their peers without such difficulties. This is because neurodivergent students often lack the automatic development of metacognitive skills that occurs incidentally in neurotypical learners. Without explicit instruction, these students may struggle to monitor their understanding, regulate their attention, or select appropriate learning strategies.

The Education Endowment Foundation's Teaching and Learning Toolkit identifies metacognition and self-regulation as having a high impact for relatively low cost, with an average effect size of +7 months' progress. However, studies focusing specifically on SEND populations show even greater effect sizes, particularly when metacognitive instruction is combined with visual supports and worked examples.

Neurodivergent students benefit more because metacognitive strategies provide:

Whilst neurotypical students may pick up metacognitive strategies through observation and incidental learning, neurodivergent learners typically require direct, explicit instruction. This aligns with cognitive load theoryprinciples: reducing unnecessary

Explicit instruction in metacognition involves:

Modelling thinking processes aloud: Teachers verbalise their own thinking, making invisible cognitive processes visible. For example, when approaching a maths problem, a teacher might say: "I'm going to read this problem twice before I start. First, I'll identify the key information. What am I being asked to find? What information do I already have? What operation do I need to use?"

Naming strategies explicitly: Rather than assuming students will identify and name strategies themselves, teachers should provide clear labels. Terms like "self-questioning", "planning", "monitoring", and "evaluating" give students a shared language for discussing thinking processes.

Providing worked examples: Demonstrating how to apply metacognitive strategies step-by-step reduces cognitive load and provides a clear model. Worked examples should include commentary on the thinking process, not just the solution.

Using consistent language: Establishing consistent terminology and phrases across subjects helps neurodivergent students recognise and transfer metacognitive strategies. A whole-school approach to metacognitive language is particularly beneficial for SEND learners.

Breaking down strategies into steps: Complex metacognitive processes should be decomposed into manageable sub-steps. For instance, "planning an essay" might involve: identify the question type, underline keywords, brainstorm ideas, select main points, decide on order, create outline.

Research from Swanson (1990) on students with learning disabilities found that explicit strategy instruction, combined with practise and feedback, produced significant improvements in academic performance across domains. The key was making strategies explicit rather than expecting students to infer them from general classroom instruction.

Students with autism often demonstrate a distinctive cognitive profile characterised by attention to detail, pattern recognition, and systematic thinking. However, they may struggle with aspects of metacognition related to self-reflection, flexible thinking, and generalising strategies across contexts.

Research by Grainger et al. (2016) found that autistic students often have difficulty with metacognitive monitoring, the ability to assess whether they understand something or whether their approach is working. This can lead to perseveration with ineffective strategies or difficulty recognising when additional support is needed.

Specific challenges for autistic learners:

Effective approaches for autistic students:

Visual supports are particularly powerful for autistic learners. Strategy checklists with images, flowcharts for decision-making, and visual timetables for planning all reduce cognitive loadwhilst making abstract processes concrete.

Explicit teaching of when and where to use strategies is essential. Rather than expecting generalisation, teachers should systematically teach application across multiple contexts, highlighting similarities and differences.

Social metacognition requires particular attention. Many metacognitive discussions assume shared understanding of social contexts. For autistic students, explicit teaching about perspective-taking and how others might think about a problem can be valuable, though care must be taken to respect neurodivergent ways of thinking rather than simply teaching "neurotypical" approaches.

Predictability and routine support metacognitive development. When students know what to expect, cognitive resources can be directed towards metacognitive processes rather than managing uncertainty or anxiety.

ADHD significantly impacts metacognitive abilities, particularly in areas of planning, self-monitoring, and impulse control. However, research by Reid et al. (2005) demonstrates that explicit metacognitive strategy instruction can help ADHD students develop compensatory approaches that support academic success.

Key metacognitive challenges with ADHD:

Effective metacognitive strategies for ADHD:

External working memory supports are important. Checklists, graphic organis ers, and written strategy prompts compensate for working memory limitations and reduce the cognitive load of trying to remember metacognitive steps whilst also completing a task.

Self-monitoring tools help ADHD students develop awareness of their attention and understanding. Simple strategies like the "5-minute check" (stop every 5 minutes and ask "Am I understanding this? Do I need to re-read?") can be significant when explicitly taught and practised.

Physical movement breaks support metacognitive regulation. Brief movement between thinking steps can help ADHD students reset and refocus. For example, "plan at your desk, walk to get materials, work at the table, return to desk to check".

Timers and visual time supports make abstract time concepts concrete. ADHD students often struggle with time estimation, a key component of metacognitive planning. Visual timers that show time passing help develop more accurate metacognitive awareness of pacing.

Breaking tasks into smaller chunks with frequent check-ins prevents the overwhelm that occurs when ADHD students face lengthy assignments. Metacognitive prompts at each check-in ("What have I accomplished? What's next? Do I need help?") build self-regulation skills.

Dyslexia affects approximately 10% of the population and impacts reading accuracy, fluency, and spelling. However, dyslexia's effects extend beyond literacy to metacognitive processes, particularly metacognitive monitoring during reading and strategy selection for written tasks.

Research by Burden (2008) found that students with dyslexia often develop negative self-beliefs about their learning capabilities, which impacts their willingness to engage in metacognitive reflection. Building metacognitive awareness alongside addressing literacy difficulties is therefore important.

Metacognitive challenges specific to dyslexia:

Supporting metacognitive development with dyslexia:

Dual coding approaches that combine

Explicit teaching of comprehension monitoring strategies is essential. Techniques like "click or clunk" (identifying words or sentences that make sense versus those that don't) give dyslexic students concrete tools for metacognitive monitoring during reading.

Text-to-speech technology can free up cognitive resources for metacognition. When decoding demands are reduced through assistive technology, dyslexic students can focus on higher-level metacognitive processes like evaluating argument quality or monitoring comprehension.

Structured writing frameworks support metacognitive planning and organisation. Templates, paragraph frames, and visual organisers provide scaffoldingthat allows dyslexic students to focus on metacognitive aspects of writing (audience, purpose, structure) rather than being overwhelmed by the physical act of writing.

Celebrating metacognitive strengths common in dyslexia (visual-spatial thinking, problem-solving, big-picture thinking) builds positive metacognitive beliefs. Many dyslexic individuals demonstrate strong metacognitive abilities in non-literacy contexts; recognising and using these strengths is important.

Cognitive load theory, developed by John Sweller, provides a important framework for understanding why neurodivergent students benefit so significantly from explicit metacognitive instruction. The theory posits that working memory has limited capacity, and learning is improved when instructional design minimises unnecessary cognitive load.

For neurodivergent learners, working memory limitations are often more pronounced. Students with ADHD typically have reduced working memory capacity. Autistic students may experience increased cognitive load from sensory processing demands. Dyslexic students face high cognitive load during literacy tasks.

Applying cognitive load theory to metacognitive instruction:

Reduce extraneous load by providing clear, structured formats for metacognitive processes. Unnecessary complexity in how metacognitive strategies are presented wastes limited cognitive resources.

Manage intrinsic load by breaking complex metacognitive skills into smaller sub-skills. Rather than teaching "planning" as a single skill, decompose it into: understanding the task, identifying resources needed, sequencing steps, estimating time, checking feasibility.

Improve germane load by using worked examples and partially completed templates. These support schema development without overwhelming working memory.

Dual coding reduces cognitive load

Progressive fading of support ensures that scaffolding is gradually removed as metacognitive skills become automatic, freeing up working memory for more complex applications.

The Universal Design for Learning framework, developed by CAST, provides an inclusive approach to implementing metacognitive instruction that benefits all learners whilst ensuring accessibility for neurodivergent students.

UDL is built on three principles: multiple means of representation, multiple means of action and expression, and multiple means of engagement. Each principle has direct implications for metacognitive instruction.

Multiple means of representation:

Present metacognitive strategies in varied formats: verbal explanations, visual diagrams, videos, worked examples, and interactive models. This ensures that students with different processing strengths can access the content.

Provide options for language and symbols by using both abstract metacognitive terminology and concrete, everyday language. For example, "self-monitoring" might also be described as "checking your understanding".

Offer alternatives for visual and auditory information. Strategy checklists should be available in visual formats with minimal text for students who struggle with reading, whilst also being available as text for those who prefer reading or who use screen readers.

Multiple means of action and expression:

Allow students to demonstrate metacognitive understanding through varied formats: verbal explanation, written reflection, drawings, concept maps, audio recordings, or demonstration.

Provide varied tools for construction and composition. Some students may express metacognitive thinking best through drawing or diagramming, others through writing or speaking.

Build fluencies with graduated levels of support. Initial metacognitive tasks might be highly scaffolded with sentence starters and templates, with support gradually reduced as competence develops.

Multiple means of engagement:

Improve individual choice and autonomy by allowing students to select which metacognitive strategies to apply to a given task, developing ownership and engagement.

Minimise threats and distractions by creating predictable structures for metacognitive reflection. Regular, brief metacognitive check-ins are less anxiety-provoking than lengthy, unpredictable reflection sessions.

Creates collaboration and community by incorporating partner and group metacognitive discussions. Hearing peers' thinking processes helps neurodivergent students develop broader metacognitive awareness.

Visual supports are among the most powerful tools for developing metacognition in neurodivergent students. Research consistently shows that visual representations of thinking processes reduce cognitive load, support working memory, and make abstract metacognitive concepts concrete.

Types of visual supports for metacognition:

Strategy checklists transform sequential metacognitive processes into visible, manageable steps. For example, a problem-solving checklist might include: read the problem, identify what you know, identify what you need to find, select a strategy, work through the solution, check your answer.

Thinking routines, such as those developed by Project Zero at Harvard, provide visual structures for metacognitive reflection. "See-Think-Wonder", "Connect-Extend-Challenge", and "I used to think.. Now I think.." give students concrete frameworks for metacognitive analysis.

Graphic organisers like mind maps, Venn diagrams, and flowcharts allow students to represent their thinking visually. For neurodivergent students, these tools reduce the language demands of metacognition whilst supporting organisation of thought.

Visual timers and schedules make time management and planning visible. For ADHD students in particular, seeing time pass supports metacognitive awareness of pacing and progress.

Colour coding can highlight different metacognitive processes. For instance, planning steps in blue, monitoring steps in yellow, and evaluation steps in green helps students distinguish between different aspects of metacognitive regulation.

Ann Brown (1987) distinguished metacognitive regulation from metacognitive knowledge, showing that even young children can learn to plan, monitor, and evaluate their own thinking when given structured support.

Implementing visual supports effectively:

Introduce visual supports explicitly, modelling how to use them multiple times before expecting independent use.

Keep visuals consistent across contexts to support recognition and transfer. Using the same strategy checklist format across subjects helps neurodivergent students recognise the strategy's applicability.

Avoid visual clutter. Whilst visuals are powerful, overloading displays with too many visual supports can increase rather than reduce cognitive load.

Personalise visual supports based on individual needs. Some students benefit from detailed, thorough visuals, whilst others need simplified versions with minimal information.

Task decomposition is a fundamental metacognitive skill that many neurodivergent students struggle with implicitly but can learn explicitly. Breaking complex tasks into manageable steps reduces overwhelm, supports planning, and enables effective self-monitoring.

Why task breakdown is important for neurodivergent learners:

Executive function challenges common in ADHD and autism impair the ability to spontaneously break down tasks. What seems like procrastination or task avoidance is often difficulty knowing where to start.

Reduced working memory capacity means neurodivergent students struggle to hold all task components in mind simultaneously. External step-by-step guides compensate for this limitation.

Perfectionism and anxiety, common in neurodivergent populations, can create paralysis when facing complex tasks. Smaller steps reduce anxiety and provide clear starting points.

Teaching task breakdown explicitly:

Model task analysis repeatedly using think-aloud protocols. Show students how you break down various tasks, from writing an essay to conducting a science experiment.

Use consistent questioning frameworks. Questions like "What's the first thing I need to do? What comes next? What's the final step?" provide a replicable structure students can internalise.

Create task breakdown templates for common assignment types. An essay breakdown template might include: analyse question, brainstorm ideas, research, create outline, write introduction, write body paragraphs, write conclusion, edit and proofread.

Practise with increasingly complex tasks. Begin with simple, familiar tasks and gradually increase complexity as students develop competence.

Teach time estimation alongside task breakdown. Each step should have an estimated time, helping students develop metacognitive awareness of pacing.

Supporting independence:

Initially, provide completed task breakdowns for students to follow. Gradually shift to co-creating breakdowns with students. Eventually, students create their own breakdowns with teacher feedback.

Use visual task boards where students can see each step and tick off completed items. This visible progress is particularly motivating for neurodivergent learners.

Celebrate successful task completion to build positive metacognitive beliefs. Many neurodivergent students have histories of incomplete work; experiencing success through structured breakdown builds confidence.

Whilst metacognitive instruction supports neurodivergent students in developing self-regulation and learning strategies, approaches respect and value neurodivergent ways of thinking rather than simply trying to make neurodivergent students think like neurotypical students.

Principles of neurodiversity-affirming metacognition:

Recognise and celebrate cognitive diversity. Different brains process information differently, and this diversity is valuable. Metacognitive instruction should help students understand and improve their unique cognitive profiles rather than conforming to a single "ideal".

Avoid deficit framing. Rather than focusing solely on what neurodivergent students struggle with, identify and use metacognitive strengths. Many autistic individuals excel at systematic, analytical thinking. Many ADHD individuals show creative problem-solving. Many dyslexic individuals demonstrate strong visual-spatial metacognition.

Provide genuine choice in strategy selection. Not all strategies work for all students. Allow neurodivergent learners to experiment with different metacognitive approaches and select what works for their individual cognitive profile.

Consider sensory needs. Metacognitive reflection requires cognitive resources that may not be available if a student is managing sensory overload. Creating sensory-supportive environments enables metacognitive engagement.

Respect different communication styles. Some neurodivergent students may struggle with verbal metacognitive reflection but excel at written or visual expression of their thinking.

Avoiding harmful practices:

Don't use metacognitive strategies as behaviour management tools that essentially teach masking. The goal isn't to make neurodivergent students "act neurotypical" but to support their learning and wellbeing.

Avoid one-size-fits-all implementation. Metacognitive strategies should be personalised based on individual strengths, challenges, and preferences.

Don't assume that neurotypical metacognitive approaches are inherently superior. Some neurodivergent thinking patterns may be more effective for certain tasks.

Even with good intentions, teachers can inadvertently undermine metacognitive development in neurodivergent students. Understanding common pitfalls helps prevent these issues.

Pitfall 1: Assuming transfer will occur automatically

Neurodivergent students often don't recognise that a strategy learned in maths applies to English or science. Transfer must be explicitly taught, highlighting similarities across contexts and practising application in varied settings.

Pitfall 2: Introducing too many strategies at once

Cognitive overload occurs when students are expected to learn multiple new metacognitive strategies simultaneously. Introduce strategies sequentially, ensuring mastery before adding new approaches.

Pitfall 3: Insufficient modelling and practise

Neurodivergent students typically require more modelling and guided practise than neurotypical peers before independent application. One demonstration is rarely sufficient; plan for multiple modelling sessions across different contexts.

Pitfall 4: Using abstract language without concrete examples

Terms like "reflect on your learning" or "monitor your understanding" can be meaningless without concrete examples. Always accompany metacognitive language with specific, observable descriptions of what the process looks like.

Pitfall 5: Forgetting to teach when strategies are useful

Students may learn a metacognitive strategy but not recognise when to apply it. Explicitly teach conditional knowledge: "Use this strategy when you encounter [specific situation]."

Pitfall 6: Neglecting working memory limitations

Expecting students to remember multi-step metacognitive processes whilst also completing academic tasks exceeds working memory capacity. Provide external memory supports like checklists and visual reminders.

Pitfall 7: Inconsistent implementation across staff

When different teachers use different terminology and approaches to metacognition, neurodivergent students struggle to recognise and transfer strategies. Whole-school consistency is important.

Pitfall 8: Focusing only on academic metacognition

Metacognitive skills support social understanding, emotional regulation, and life skills. Don't limit metacognitive instruction to academic contexts.

Case Study 1: Tom, Year 8 student with ADHD

Tom struggled with essay writing, typically producing disorganised, incomplete responses. His teacher introduced a visual essay planning framework with explicit metacognitive prompts: "What type of question is this? What do I already know about the topic? What's my main argument? What evidence supports each point?"

This connects closely with research on critical thinking skills, which provides further classroom strategies for teachers.

Initially, the teacher completed the framework with Tom, thinking aloud throughout the process. Over several weeks, support was gradually reduced. Tom began independently using the framework, and his essay quality improved dramatically. Critically, Tom transferred the approach to other subjects without prompting, demonstrating that explicit instruction had built genuine metacognitive understanding rather than mere compliance.

Case Study 2: Aisha, Year 5 student with autism

Aisha excelled at decoding but struggled with reading comprehension. Her teacher introduced the "click or clunk" metacognitive monitoring strategy: after each paragraph, Aisha used a visual checklist to identify sentences that "clicked" (made sense) and "clunked" (were confusing). For "clunks", she had a flowchart of fix-up strategies: re-read, look at pictures, read ahead for context, ask for help.

The visual, systematic nature of the approach suited Aisha's cognitive profile. Within a term, her comprehension improved significantly. The strategy also reduced her anxiety about reading, as she now had a clear process for managing confusion rather than becoming overwhelmed.

Case Study 3: Jordan, Year 10 student with dyslexia

Jordan avoided writing tasks due to spelling and handwriting difficulties, which had led to negative metacognitive beliefs ("I'm not a good writer"). His teacher implemented a dual coding approach: Jordan could plan essays using mind maps with drawings and minimal text, then dictate his writing using speech-to-text software.

This removed barriers that prevented Jordan engaging with higher-level metacognitive processes. With cognitive resources no longer consumed by spelling and handwriting, Jordan could focus on audience, argument structure, and evidence quality. His metacognitive awareness of what makes effective writing increased dramatically, and his self-belief improved.

Case Study 4: Whole School Implementation

A primary school implemented a whole-school approach to metacognitive language and visual supports. Every classroom displayed the same "learning power" visuals (based on Building Learning Power), and all staff used consistent terminology for metacognitive processes.

SEND students particularly benefited from this consistency. Strategies introduced by learning support staff were recognised and reinforced in mainstream classrooms. Parents reported children using metacognitive language at home. End-of-year data showed SEND students made above-expected progress, with qualitative feedback indicating increased independence and self-regulation.

Metacognition refers to a learner's awareness and regulation of their own thinking processes. For SEND students, this means providing structured, explicit frameworks to help them plan, monitor, and evaluate their work. While neurotypical students might develop these skills naturally, neurodivergent learners often require direct instruction to build self-awareness and independence.

Teachers must make their own thinking visible by regularly thinking aloud and modelling tasks. It is essential to break complex activities into smaller, manageable steps using visual checklists and clear prompts. Educators should also establish consistent language across all subjects so that students can easily recognise and apply these strategies in different contexts.

Neurotypical students often absorb learning strategies implicitly through observation and incidental learning. However, neurodivergent students generally need direct, explicit instruction to understand how to manage their cognitive load and regulate their attention. Naming strategies clearly and providing gradual worked examples prevents cognitive overload and builds lasting self-regulation habits.

The Education Endowment Foundation identifies metacognition as a highly effective and inexpensive approach that typically adds seven months of academic progress. Research indicates that students with learning difficulties show even greater gains than their peers when taught these skills directly. Combining these methods with visual supports and structured routines is particularly effective for special educational needs.

A frequent mistake is assuming that students will naturally pick up study skills or regulate their behaviour without direct modelling. Teachers also sometimes introduce too many strategies at once, which increases cognitive load and causes overwhelming frustration. Instead, educators should focus on teaching one specific technique at a time and provide immediate, precise feedback on how the student applies it.

Generate an 8-week metacognition roadmap tailored to your key stage, subject, and current practise level.

Metacognition and Special Educational Needs by David Whitebread and Marisol Pasternak (2010)

This seminal paper examines how metacognitive instruction benefits students with learning difficulties more than mainstream populations. The authors review experimental studies showing effect sizes up to twice as large for SEND students when metacognitive strategies are explicitly taught with scaffolding gradually removed. View study, 234 citations

Executive Function and Metacognition by Philip David Zelazo and Sophie Jacques (2012)

Zelazo and Jacques explore the relationship between executive function (planning, working memory, inhibitory control) and metacognitive development. Their research is particularly relevant for understanding why neurodivergent students with executive function challenges benefit from explicit metacognitive instruction. The paper provides a theoretical framework for understanding how metacognitive scaffolding compensates for executive function difficulties. View study, 412 citations

Teaching Metacognitive Skills to Children with Learning Disabilities by H. Lee Swanson (1990)

This thorough reviewexamines decades of research on metacognitive instruction for students with learning disabilities. Swanson identifies explicit strategy instruction, modelling, and practise with feedback as critical components of effective intervention. The paper provides evidence that metacognitive deficits in learning disabled students are not insurmountable but respond to systematic instruction. View study, 543 citations

Metacognition in Autism Spectrum Disorders by Catherine Grainger and colleagues (2016)

Grainger's research team investigated metacognitive monitoring abilities in autistic children compared to neurotypical peers. They found that autistic students have particular difficulty assessing their own understanding and knowing when they need help. The paper discusses implications for educational practise, emphasising the need for explicit instruction in self-monitoring strategies and visual supports. View study, 167 citations

Research on metacognitive strategies for dyslexic learners (Burden, 2008) explores how students with dyslexia ca n develop greater awareness of their learning processes and use effective self-regulation techniques to improve their academic performance.

Burden examines how dyslexia affects not just literacy skills but also metacognitive beliefs and self-regulation. His research shows that dyslexic students often develop negative metacognitive beliefs about their learning capabilities, which becomes a self-fulfiling prophecy. The paper argues that building positive metacognitive awareness alongside literacy intervention is important for long-term success. View study, 189 citations

Metacognitive instruction represents one of the most powerful pedagogical approaches for supporting neurodivergent learners. Research consistently demonstrates that explicit teaching of thinking strategies, combined with visual supports, task decomposition, and scaffolded practise, enables neurodivergent students to develop self-awareness and self-regulation that supports independent learning.

The key principles are clear: make thinking processes explicit, reduce cognitive load through visual supports and structured frameworks, break complex skills into manageable steps, respect neurodivergent thinking patterns, and ensure consistency across educational contexts. When these principles are applied systematically, neurodivergent students develop the metacognitive skills that enable them to understand their own cognitive profiles, select appropriate strategies, monitor their progress, and regulate their learning.

Perhaps most importantly, effective metacognitive instruction builds positive self-beliefs. Many neurodivergent students have experienced repeated academic struggles that lead to learned helplessness. Metacognitive strategies provide tools for success, transforming students from passive recipients of learning to active, strategic thinkers who understand how they learn best and can advocate for their needs.

The evidence is clear: metacognition is not a luxury or optional extra for neurodivergent students. It is an essential component of inclusive education that unlocks potential and builds independence. By implementing the strategies and principles outlined in this guide, teachers can make a profound difference in the educational trajectories of their neurodivergent learners.

These peer-reviewed studies provide the research foundation for the strategies discussed in this article:

Implementing Deep Learning Approaches for Students with Special Needs: A Systematic Literature Review View study ↗

.. Marlina et al. (2025)

This comprehensive review of 56 studies reveals how artificial intelligence and deep learning technologies are being successfully used to support students with special educational needs across different learning contexts. The research shows that these digital tools can personalise learning experiences, provide real-time feedback, and adapt to individual student needs in ways that traditional methods cannot. Teachers working with SEND students will find valuable insights into evidence-based technological approaches that can enhance classroom accessibility and learning outcomes.

Rethinking Mathematics Anxiety: Cognitive, Pedagogical, and Social Dimensions of an Affective Ecosystem View study ↗

M. K. Serin (2025)

This study reframes mathematics anxiety as more than just a fear of numbers, showing how it involves complex interactions between students' thinking processes, teaching methods, and classroom social dynamics. The research demonstrates that addressing math anxiety requires a holistic approach that considers emotional regulation, memory challenges, and the learning environment together. Mathematics teachers will gain practical understanding of how to create supportive classroom ecosystems that reduce anxiety and improve student confidence through targeted pedagogical strategies.

Analisis Kebutuhan Asesmen Working Memory dalam Pembelajaran Fisika di Sekolah Inklusif: Kajian Literatur View study ↗

Lasmita Sari et al. (2025)

This research highlights how working memory capacity, the brain's ability to hold and manipulate information temporarily, critically affects students' success in physics learning within inclusive classrooms. The study reveals that students with limited working memory often struggle to follow complex instructions and solve multi-step physics problems, making assessment of these skills essential for effective teaching. Physics teachers in inclusive settings will discover why understanding each student's working memory capacity is crucial for designing appropriate learning tasks and providing targeted support.

Off-task behaviour in kindergarten: Relations to executive function and academic achievement. View study ↗

47 citations

Lillie Moffett & F. Morrison (2020)

This classroom observation study of 172 kindergarteners demonstrates that children's ability to stay focused and control their behaviour directly predicts their academic success throughout the school day. The research shows that off-task behaviours are closely linked to executive function skills like attention control and working memory, providing teachers with observable indicators of underlying cognitive abilities. Early years teachers will gain valuable insights into how behavioural observations can inform their understanding of children's learning needs and guide targeted support strategies.

Teaching Strategies for ADHD Student in Inclusive Classroom: A Case Study View study ↗

Dewi Nurlyan Purwita et al. (2025)

This in-depth case study examines the specific teaching strategies an English teacher successfully uses to support a student with ADHD in a mainstream classroom alongside their peers. The research documents practical approaches that help ADHD students overcome common learning challenges like attention difficulties and impulsivity while maintaining inclusion in regular classroom activities. Teachers working with ADHD students will find concrete, classroom-tested strategies that can be adapted across different subjects and age groups to create more inclusive learning environments.

Neurodivergent students, including those with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), ADHD, dyslexia, and other specific learning differences, face unique challenges in educational settings. Research increasingly shows that these students benefit significantly more from explicit metacognitive instruction than their neurotypical peers. This thorough guideexplores how teachers can use metacognitive strategies to support neurodivergent learners, helping them develop self-awareness, self-regulation, and independent learning skills that are essential for long-term academic success.

| Challenge Area | Common Difficulty | Metacognitive Support | Practical Adaptation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Executive Function | Planning and organisation | Explicit teaching of strategies | Visual checklists and prompts |

| Working Memory | Holding information | External memory aids | Note-taking scaffolds |

| Self-Regulation | Managing emotions/behaviour | Emotion identification tools | Calm-down strategies |

| Attention | Sustaining focus | Self-monitoring techniques | Timers and breaks |

| Flexibility | Adapting to change | Preparation and preview | Visual schedules |

Metacognition, or "thinking about thinking", involves awareness and regulation of one's own cognitive processes. For neurodivergent learners, metacognitive strategies provide a structured framework for navigating the cognitive demands of learning that neurotypical students may develop implicitly.

Research from Whitebread and Pino-Pasternak (2010) demonstrates that children with learning difficulties show significantly greater gains from metacognitive instruction than their peers without such difficulties. This is because neurodivergent students often lack the automatic development of metacognitive skills that occurs incidentally in neurotypical learners. Without explicit instruction, these students may struggle to monitor their understanding, regulate their attention, or select appropriate learning strategies.

The Education Endowment Foundation's Teaching and Learning Toolkit identifies metacognition and self-regulation as having a high impact for relatively low cost, with an average effect size of +7 months' progress. However, studies focusing specifically on SEND populations show even greater effect sizes, particularly when metacognitive instruction is combined with visual supports and worked examples.

Neurodivergent students benefit more because metacognitive strategies provide:

Whilst neurotypical students may pick up metacognitive strategies through observation and incidental learning, neurodivergent learners typically require direct, explicit instruction. This aligns with cognitive load theoryprinciples: reducing unnecessary

Explicit instruction in metacognition involves:

Modelling thinking processes aloud: Teachers verbalise their own thinking, making invisible cognitive processes visible. For example, when approaching a maths problem, a teacher might say: "I'm going to read this problem twice before I start. First, I'll identify the key information. What am I being asked to find? What information do I already have? What operation do I need to use?"

Naming strategies explicitly: Rather than assuming students will identify and name strategies themselves, teachers should provide clear labels. Terms like "self-questioning", "planning", "monitoring", and "evaluating" give students a shared language for discussing thinking processes.

Providing worked examples: Demonstrating how to apply metacognitive strategies step-by-step reduces cognitive load and provides a clear model. Worked examples should include commentary on the thinking process, not just the solution.

Using consistent language: Establishing consistent terminology and phrases across subjects helps neurodivergent students recognise and transfer metacognitive strategies. A whole-school approach to metacognitive language is particularly beneficial for SEND learners.

Breaking down strategies into steps: Complex metacognitive processes should be decomposed into manageable sub-steps. For instance, "planning an essay" might involve: identify the question type, underline keywords, brainstorm ideas, select main points, decide on order, create outline.

Research from Swanson (1990) on students with learning disabilities found that explicit strategy instruction, combined with practise and feedback, produced significant improvements in academic performance across domains. The key was making strategies explicit rather than expecting students to infer them from general classroom instruction.

Students with autism often demonstrate a distinctive cognitive profile characterised by attention to detail, pattern recognition, and systematic thinking. However, they may struggle with aspects of metacognition related to self-reflection, flexible thinking, and generalising strategies across contexts.

Research by Grainger et al. (2016) found that autistic students often have difficulty with metacognitive monitoring, the ability to assess whether they understand something or whether their approach is working. This can lead to perseveration with ineffective strategies or difficulty recognising when additional support is needed.

Specific challenges for autistic learners:

Effective approaches for autistic students:

Visual supports are particularly powerful for autistic learners. Strategy checklists with images, flowcharts for decision-making, and visual timetables for planning all reduce cognitive loadwhilst making abstract processes concrete.

Explicit teaching of when and where to use strategies is essential. Rather than expecting generalisation, teachers should systematically teach application across multiple contexts, highlighting similarities and differences.

Social metacognition requires particular attention. Many metacognitive discussions assume shared understanding of social contexts. For autistic students, explicit teaching about perspective-taking and how others might think about a problem can be valuable, though care must be taken to respect neurodivergent ways of thinking rather than simply teaching "neurotypical" approaches.

Predictability and routine support metacognitive development. When students know what to expect, cognitive resources can be directed towards metacognitive processes rather than managing uncertainty or anxiety.

ADHD significantly impacts metacognitive abilities, particularly in areas of planning, self-monitoring, and impulse control. However, research by Reid et al. (2005) demonstrates that explicit metacognitive strategy instruction can help ADHD students develop compensatory approaches that support academic success.

Key metacognitive challenges with ADHD:

Effective metacognitive strategies for ADHD:

External working memory supports are important. Checklists, graphic organis ers, and written strategy prompts compensate for working memory limitations and reduce the cognitive load of trying to remember metacognitive steps whilst also completing a task.

Self-monitoring tools help ADHD students develop awareness of their attention and understanding. Simple strategies like the "5-minute check" (stop every 5 minutes and ask "Am I understanding this? Do I need to re-read?") can be significant when explicitly taught and practised.

Physical movement breaks support metacognitive regulation. Brief movement between thinking steps can help ADHD students reset and refocus. For example, "plan at your desk, walk to get materials, work at the table, return to desk to check".

Timers and visual time supports make abstract time concepts concrete. ADHD students often struggle with time estimation, a key component of metacognitive planning. Visual timers that show time passing help develop more accurate metacognitive awareness of pacing.

Breaking tasks into smaller chunks with frequent check-ins prevents the overwhelm that occurs when ADHD students face lengthy assignments. Metacognitive prompts at each check-in ("What have I accomplished? What's next? Do I need help?") build self-regulation skills.

Dyslexia affects approximately 10% of the population and impacts reading accuracy, fluency, and spelling. However, dyslexia's effects extend beyond literacy to metacognitive processes, particularly metacognitive monitoring during reading and strategy selection for written tasks.

Research by Burden (2008) found that students with dyslexia often develop negative self-beliefs about their learning capabilities, which impacts their willingness to engage in metacognitive reflection. Building metacognitive awareness alongside addressing literacy difficulties is therefore important.

Metacognitive challenges specific to dyslexia:

Supporting metacognitive development with dyslexia:

Dual coding approaches that combine

Explicit teaching of comprehension monitoring strategies is essential. Techniques like "click or clunk" (identifying words or sentences that make sense versus those that don't) give dyslexic students concrete tools for metacognitive monitoring during reading.

Text-to-speech technology can free up cognitive resources for metacognition. When decoding demands are reduced through assistive technology, dyslexic students can focus on higher-level metacognitive processes like evaluating argument quality or monitoring comprehension.

Structured writing frameworks support metacognitive planning and organisation. Templates, paragraph frames, and visual organisers provide scaffoldingthat allows dyslexic students to focus on metacognitive aspects of writing (audience, purpose, structure) rather than being overwhelmed by the physical act of writing.

Celebrating metacognitive strengths common in dyslexia (visual-spatial thinking, problem-solving, big-picture thinking) builds positive metacognitive beliefs. Many dyslexic individuals demonstrate strong metacognitive abilities in non-literacy contexts; recognising and using these strengths is important.

Cognitive load theory, developed by John Sweller, provides a important framework for understanding why neurodivergent students benefit so significantly from explicit metacognitive instruction. The theory posits that working memory has limited capacity, and learning is improved when instructional design minimises unnecessary cognitive load.

For neurodivergent learners, working memory limitations are often more pronounced. Students with ADHD typically have reduced working memory capacity. Autistic students may experience increased cognitive load from sensory processing demands. Dyslexic students face high cognitive load during literacy tasks.

Applying cognitive load theory to metacognitive instruction:

Reduce extraneous load by providing clear, structured formats for metacognitive processes. Unnecessary complexity in how metacognitive strategies are presented wastes limited cognitive resources.

Manage intrinsic load by breaking complex metacognitive skills into smaller sub-skills. Rather than teaching "planning" as a single skill, decompose it into: understanding the task, identifying resources needed, sequencing steps, estimating time, checking feasibility.

Improve germane load by using worked examples and partially completed templates. These support schema development without overwhelming working memory.

Dual coding reduces cognitive load

Progressive fading of support ensures that scaffolding is gradually removed as metacognitive skills become automatic, freeing up working memory for more complex applications.

The Universal Design for Learning framework, developed by CAST, provides an inclusive approach to implementing metacognitive instruction that benefits all learners whilst ensuring accessibility for neurodivergent students.

UDL is built on three principles: multiple means of representation, multiple means of action and expression, and multiple means of engagement. Each principle has direct implications for metacognitive instruction.

Multiple means of representation:

Present metacognitive strategies in varied formats: verbal explanations, visual diagrams, videos, worked examples, and interactive models. This ensures that students with different processing strengths can access the content.

Provide options for language and symbols by using both abstract metacognitive terminology and concrete, everyday language. For example, "self-monitoring" might also be described as "checking your understanding".

Offer alternatives for visual and auditory information. Strategy checklists should be available in visual formats with minimal text for students who struggle with reading, whilst also being available as text for those who prefer reading or who use screen readers.

Multiple means of action and expression:

Allow students to demonstrate metacognitive understanding through varied formats: verbal explanation, written reflection, drawings, concept maps, audio recordings, or demonstration.

Provide varied tools for construction and composition. Some students may express metacognitive thinking best through drawing or diagramming, others through writing or speaking.

Build fluencies with graduated levels of support. Initial metacognitive tasks might be highly scaffolded with sentence starters and templates, with support gradually reduced as competence develops.

Multiple means of engagement:

Improve individual choice and autonomy by allowing students to select which metacognitive strategies to apply to a given task, developing ownership and engagement.

Minimise threats and distractions by creating predictable structures for metacognitive reflection. Regular, brief metacognitive check-ins are less anxiety-provoking than lengthy, unpredictable reflection sessions.

Creates collaboration and community by incorporating partner and group metacognitive discussions. Hearing peers' thinking processes helps neurodivergent students develop broader metacognitive awareness.

Visual supports are among the most powerful tools for developing metacognition in neurodivergent students. Research consistently shows that visual representations of thinking processes reduce cognitive load, support working memory, and make abstract metacognitive concepts concrete.

Types of visual supports for metacognition:

Strategy checklists transform sequential metacognitive processes into visible, manageable steps. For example, a problem-solving checklist might include: read the problem, identify what you know, identify what you need to find, select a strategy, work through the solution, check your answer.

Thinking routines, such as those developed by Project Zero at Harvard, provide visual structures for metacognitive reflection. "See-Think-Wonder", "Connect-Extend-Challenge", and "I used to think.. Now I think.." give students concrete frameworks for metacognitive analysis.

Graphic organisers like mind maps, Venn diagrams, and flowcharts allow students to represent their thinking visually. For neurodivergent students, these tools reduce the language demands of metacognition whilst supporting organisation of thought.

Visual timers and schedules make time management and planning visible. For ADHD students in particular, seeing time pass supports metacognitive awareness of pacing and progress.

Colour coding can highlight different metacognitive processes. For instance, planning steps in blue, monitoring steps in yellow, and evaluation steps in green helps students distinguish between different aspects of metacognitive regulation.

Ann Brown (1987) distinguished metacognitive regulation from metacognitive knowledge, showing that even young children can learn to plan, monitor, and evaluate their own thinking when given structured support.

Implementing visual supports effectively:

Introduce visual supports explicitly, modelling how to use them multiple times before expecting independent use.

Keep visuals consistent across contexts to support recognition and transfer. Using the same strategy checklist format across subjects helps neurodivergent students recognise the strategy's applicability.

Avoid visual clutter. Whilst visuals are powerful, overloading displays with too many visual supports can increase rather than reduce cognitive load.

Personalise visual supports based on individual needs. Some students benefit from detailed, thorough visuals, whilst others need simplified versions with minimal information.

Task decomposition is a fundamental metacognitive skill that many neurodivergent students struggle with implicitly but can learn explicitly. Breaking complex tasks into manageable steps reduces overwhelm, supports planning, and enables effective self-monitoring.

Why task breakdown is important for neurodivergent learners:

Executive function challenges common in ADHD and autism impair the ability to spontaneously break down tasks. What seems like procrastination or task avoidance is often difficulty knowing where to start.

Reduced working memory capacity means neurodivergent students struggle to hold all task components in mind simultaneously. External step-by-step guides compensate for this limitation.

Perfectionism and anxiety, common in neurodivergent populations, can create paralysis when facing complex tasks. Smaller steps reduce anxiety and provide clear starting points.

Teaching task breakdown explicitly:

Model task analysis repeatedly using think-aloud protocols. Show students how you break down various tasks, from writing an essay to conducting a science experiment.

Use consistent questioning frameworks. Questions like "What's the first thing I need to do? What comes next? What's the final step?" provide a replicable structure students can internalise.

Create task breakdown templates for common assignment types. An essay breakdown template might include: analyse question, brainstorm ideas, research, create outline, write introduction, write body paragraphs, write conclusion, edit and proofread.

Practise with increasingly complex tasks. Begin with simple, familiar tasks and gradually increase complexity as students develop competence.

Teach time estimation alongside task breakdown. Each step should have an estimated time, helping students develop metacognitive awareness of pacing.

Supporting independence:

Initially, provide completed task breakdowns for students to follow. Gradually shift to co-creating breakdowns with students. Eventually, students create their own breakdowns with teacher feedback.

Use visual task boards where students can see each step and tick off completed items. This visible progress is particularly motivating for neurodivergent learners.

Celebrate successful task completion to build positive metacognitive beliefs. Many neurodivergent students have histories of incomplete work; experiencing success through structured breakdown builds confidence.

Whilst metacognitive instruction supports neurodivergent students in developing self-regulation and learning strategies, approaches respect and value neurodivergent ways of thinking rather than simply trying to make neurodivergent students think like neurotypical students.

Principles of neurodiversity-affirming metacognition:

Recognise and celebrate cognitive diversity. Different brains process information differently, and this diversity is valuable. Metacognitive instruction should help students understand and improve their unique cognitive profiles rather than conforming to a single "ideal".

Avoid deficit framing. Rather than focusing solely on what neurodivergent students struggle with, identify and use metacognitive strengths. Many autistic individuals excel at systematic, analytical thinking. Many ADHD individuals show creative problem-solving. Many dyslexic individuals demonstrate strong visual-spatial metacognition.

Provide genuine choice in strategy selection. Not all strategies work for all students. Allow neurodivergent learners to experiment with different metacognitive approaches and select what works for their individual cognitive profile.

Consider sensory needs. Metacognitive reflection requires cognitive resources that may not be available if a student is managing sensory overload. Creating sensory-supportive environments enables metacognitive engagement.

Respect different communication styles. Some neurodivergent students may struggle with verbal metacognitive reflection but excel at written or visual expression of their thinking.

Avoiding harmful practices:

Don't use metacognitive strategies as behaviour management tools that essentially teach masking. The goal isn't to make neurodivergent students "act neurotypical" but to support their learning and wellbeing.

Avoid one-size-fits-all implementation. Metacognitive strategies should be personalised based on individual strengths, challenges, and preferences.

Don't assume that neurotypical metacognitive approaches are inherently superior. Some neurodivergent thinking patterns may be more effective for certain tasks.

Even with good intentions, teachers can inadvertently undermine metacognitive development in neurodivergent students. Understanding common pitfalls helps prevent these issues.

Pitfall 1: Assuming transfer will occur automatically

Neurodivergent students often don't recognise that a strategy learned in maths applies to English or science. Transfer must be explicitly taught, highlighting similarities across contexts and practising application in varied settings.

Pitfall 2: Introducing too many strategies at once

Cognitive overload occurs when students are expected to learn multiple new metacognitive strategies simultaneously. Introduce strategies sequentially, ensuring mastery before adding new approaches.

Pitfall 3: Insufficient modelling and practise

Neurodivergent students typically require more modelling and guided practise than neurotypical peers before independent application. One demonstration is rarely sufficient; plan for multiple modelling sessions across different contexts.

Pitfall 4: Using abstract language without concrete examples

Terms like "reflect on your learning" or "monitor your understanding" can be meaningless without concrete examples. Always accompany metacognitive language with specific, observable descriptions of what the process looks like.

Pitfall 5: Forgetting to teach when strategies are useful

Students may learn a metacognitive strategy but not recognise when to apply it. Explicitly teach conditional knowledge: "Use this strategy when you encounter [specific situation]."

Pitfall 6: Neglecting working memory limitations

Expecting students to remember multi-step metacognitive processes whilst also completing academic tasks exceeds working memory capacity. Provide external memory supports like checklists and visual reminders.

Pitfall 7: Inconsistent implementation across staff

When different teachers use different terminology and approaches to metacognition, neurodivergent students struggle to recognise and transfer strategies. Whole-school consistency is important.

Pitfall 8: Focusing only on academic metacognition

Metacognitive skills support social understanding, emotional regulation, and life skills. Don't limit metacognitive instruction to academic contexts.

Case Study 1: Tom, Year 8 student with ADHD

Tom struggled with essay writing, typically producing disorganised, incomplete responses. His teacher introduced a visual essay planning framework with explicit metacognitive prompts: "What type of question is this? What do I already know about the topic? What's my main argument? What evidence supports each point?"

This connects closely with research on critical thinking skills, which provides further classroom strategies for teachers.

Initially, the teacher completed the framework with Tom, thinking aloud throughout the process. Over several weeks, support was gradually reduced. Tom began independently using the framework, and his essay quality improved dramatically. Critically, Tom transferred the approach to other subjects without prompting, demonstrating that explicit instruction had built genuine metacognitive understanding rather than mere compliance.

Case Study 2: Aisha, Year 5 student with autism

Aisha excelled at decoding but struggled with reading comprehension. Her teacher introduced the "click or clunk" metacognitive monitoring strategy: after each paragraph, Aisha used a visual checklist to identify sentences that "clicked" (made sense) and "clunked" (were confusing). For "clunks", she had a flowchart of fix-up strategies: re-read, look at pictures, read ahead for context, ask for help.

The visual, systematic nature of the approach suited Aisha's cognitive profile. Within a term, her comprehension improved significantly. The strategy also reduced her anxiety about reading, as she now had a clear process for managing confusion rather than becoming overwhelmed.

Case Study 3: Jordan, Year 10 student with dyslexia

Jordan avoided writing tasks due to spelling and handwriting difficulties, which had led to negative metacognitive beliefs ("I'm not a good writer"). His teacher implemented a dual coding approach: Jordan could plan essays using mind maps with drawings and minimal text, then dictate his writing using speech-to-text software.

This removed barriers that prevented Jordan engaging with higher-level metacognitive processes. With cognitive resources no longer consumed by spelling and handwriting, Jordan could focus on audience, argument structure, and evidence quality. His metacognitive awareness of what makes effective writing increased dramatically, and his self-belief improved.

Case Study 4: Whole School Implementation

A primary school implemented a whole-school approach to metacognitive language and visual supports. Every classroom displayed the same "learning power" visuals (based on Building Learning Power), and all staff used consistent terminology for metacognitive processes.

SEND students particularly benefited from this consistency. Strategies introduced by learning support staff were recognised and reinforced in mainstream classrooms. Parents reported children using metacognitive language at home. End-of-year data showed SEND students made above-expected progress, with qualitative feedback indicating increased independence and self-regulation.

Metacognition refers to a learner's awareness and regulation of their own thinking processes. For SEND students, this means providing structured, explicit frameworks to help them plan, monitor, and evaluate their work. While neurotypical students might develop these skills naturally, neurodivergent learners often require direct instruction to build self-awareness and independence.

Teachers must make their own thinking visible by regularly thinking aloud and modelling tasks. It is essential to break complex activities into smaller, manageable steps using visual checklists and clear prompts. Educators should also establish consistent language across all subjects so that students can easily recognise and apply these strategies in different contexts.

Neurotypical students often absorb learning strategies implicitly through observation and incidental learning. However, neurodivergent students generally need direct, explicit instruction to understand how to manage their cognitive load and regulate their attention. Naming strategies clearly and providing gradual worked examples prevents cognitive overload and builds lasting self-regulation habits.

The Education Endowment Foundation identifies metacognition as a highly effective and inexpensive approach that typically adds seven months of academic progress. Research indicates that students with learning difficulties show even greater gains than their peers when taught these skills directly. Combining these methods with visual supports and structured routines is particularly effective for special educational needs.

A frequent mistake is assuming that students will naturally pick up study skills or regulate their behaviour without direct modelling. Teachers also sometimes introduce too many strategies at once, which increases cognitive load and causes overwhelming frustration. Instead, educators should focus on teaching one specific technique at a time and provide immediate, precise feedback on how the student applies it.

Generate an 8-week metacognition roadmap tailored to your key stage, subject, and current practise level.

Metacognition and Special Educational Needs by David Whitebread and Marisol Pasternak (2010)

This seminal paper examines how metacognitive instruction benefits students with learning difficulties more than mainstream populations. The authors review experimental studies showing effect sizes up to twice as large for SEND students when metacognitive strategies are explicitly taught with scaffolding gradually removed. View study, 234 citations

Executive Function and Metacognition by Philip David Zelazo and Sophie Jacques (2012)

Zelazo and Jacques explore the relationship between executive function (planning, working memory, inhibitory control) and metacognitive development. Their research is particularly relevant for understanding why neurodivergent students with executive function challenges benefit from explicit metacognitive instruction. The paper provides a theoretical framework for understanding how metacognitive scaffolding compensates for executive function difficulties. View study, 412 citations

Teaching Metacognitive Skills to Children with Learning Disabilities by H. Lee Swanson (1990)

This thorough reviewexamines decades of research on metacognitive instruction for students with learning disabilities. Swanson identifies explicit strategy instruction, modelling, and practise with feedback as critical components of effective intervention. The paper provides evidence that metacognitive deficits in learning disabled students are not insurmountable but respond to systematic instruction. View study, 543 citations

Metacognition in Autism Spectrum Disorders by Catherine Grainger and colleagues (2016)

Grainger's research team investigated metacognitive monitoring abilities in autistic children compared to neurotypical peers. They found that autistic students have particular difficulty assessing their own understanding and knowing when they need help. The paper discusses implications for educational practise, emphasising the need for explicit instruction in self-monitoring strategies and visual supports. View study, 167 citations

Research on metacognitive strategies for dyslexic learners (Burden, 2008) explores how students with dyslexia ca n develop greater awareness of their learning processes and use effective self-regulation techniques to improve their academic performance.

Burden examines how dyslexia affects not just literacy skills but also metacognitive beliefs and self-regulation. His research shows that dyslexic students often develop negative metacognitive beliefs about their learning capabilities, which becomes a self-fulfiling prophecy. The paper argues that building positive metacognitive awareness alongside literacy intervention is important for long-term success. View study, 189 citations

Metacognitive instruction represents one of the most powerful pedagogical approaches for supporting neurodivergent learners. Research consistently demonstrates that explicit teaching of thinking strategies, combined with visual supports, task decomposition, and scaffolded practise, enables neurodivergent students to develop self-awareness and self-regulation that supports independent learning.

The key principles are clear: make thinking processes explicit, reduce cognitive load through visual supports and structured frameworks, break complex skills into manageable steps, respect neurodivergent thinking patterns, and ensure consistency across educational contexts. When these principles are applied systematically, neurodivergent students develop the metacognitive skills that enable them to understand their own cognitive profiles, select appropriate strategies, monitor their progress, and regulate their learning.

Perhaps most importantly, effective metacognitive instruction builds positive self-beliefs. Many neurodivergent students have experienced repeated academic struggles that lead to learned helplessness. Metacognitive strategies provide tools for success, transforming students from passive recipients of learning to active, strategic thinkers who understand how they learn best and can advocate for their needs.

The evidence is clear: metacognition is not a luxury or optional extra for neurodivergent students. It is an essential component of inclusive education that unlocks potential and builds independence. By implementing the strategies and principles outlined in this guide, teachers can make a profound difference in the educational trajectories of their neurodivergent learners.

These peer-reviewed studies provide the research foundation for the strategies discussed in this article:

Implementing Deep Learning Approaches for Students with Special Needs: A Systematic Literature Review View study ↗

.. Marlina et al. (2025)

This comprehensive review of 56 studies reveals how artificial intelligence and deep learning technologies are being successfully used to support students with special educational needs across different learning contexts. The research shows that these digital tools can personalise learning experiences, provide real-time feedback, and adapt to individual student needs in ways that traditional methods cannot. Teachers working with SEND students will find valuable insights into evidence-based technological approaches that can enhance classroom accessibility and learning outcomes.

Rethinking Mathematics Anxiety: Cognitive, Pedagogical, and Social Dimensions of an Affective Ecosystem View study ↗

M. K. Serin (2025)

This study reframes mathematics anxiety as more than just a fear of numbers, showing how it involves complex interactions between students' thinking processes, teaching methods, and classroom social dynamics. The research demonstrates that addressing math anxiety requires a holistic approach that considers emotional regulation, memory challenges, and the learning environment together. Mathematics teachers will gain practical understanding of how to create supportive classroom ecosystems that reduce anxiety and improve student confidence through targeted pedagogical strategies.

Analisis Kebutuhan Asesmen Working Memory dalam Pembelajaran Fisika di Sekolah Inklusif: Kajian Literatur View study ↗

Lasmita Sari et al. (2025)

This research highlights how working memory capacity, the brain's ability to hold and manipulate information temporarily, critically affects students' success in physics learning within inclusive classrooms. The study reveals that students with limited working memory often struggle to follow complex instructions and solve multi-step physics problems, making assessment of these skills essential for effective teaching. Physics teachers in inclusive settings will discover why understanding each student's working memory capacity is crucial for designing appropriate learning tasks and providing targeted support.

Off-task behaviour in kindergarten: Relations to executive function and academic achievement. View study ↗

47 citations

Lillie Moffett & F. Morrison (2020)

This classroom observation study of 172 kindergarteners demonstrates that children's ability to stay focused and control their behaviour directly predicts their academic success throughout the school day. The research shows that off-task behaviours are closely linked to executive function skills like attention control and working memory, providing teachers with observable indicators of underlying cognitive abilities. Early years teachers will gain valuable insights into how behavioural observations can inform their understanding of children's learning needs and guide targeted support strategies.

Teaching Strategies for ADHD Student in Inclusive Classroom: A Case Study View study ↗

Dewi Nurlyan Purwita et al. (2025)

This in-depth case study examines the specific teaching strategies an English teacher successfully uses to support a student with ADHD in a mainstream classroom alongside their peers. The research documents practical approaches that help ADHD students overcome common learning challenges like attention difficulties and impulsivity while maintaining inclusion in regular classroom activities. Teachers working with ADHD students will find concrete, classroom-tested strategies that can be adapted across different subjects and age groups to create more inclusive learning environments.

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/metacognition-send-neurodivergent-students#article","headline":"Metacognition for SEND and Neurodivergent Students","description":"Explore effective strategies for teaching metacognition to SEND and neurodivergent students, including visual supports and tailored scaffolding techniques.","datePublished":"2026-01-20T09:14:10.544Z","dateModified":"2026-03-05T14:41:57.358Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/metacognition-send-neurodivergent-students"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/6971fedb0b262fc4ff0e6dba_696f4762e743077aba11f5bc_696f46c9aef6c49ad2afd7d9_metacognition-for-send-and-neu-comparison-1768900293136.webp","wordCount":5327},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/metacognition-send-neurodivergent-students#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"Metacognition for SEND and Neurodivergent Students","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/metacognition-send-neurodivergent-students"}]}]}