Metacognitive Strategies in Reading Comprehension

Enhance reading comprehension with metacognitive strategies. Learn how self-awareness, regulation, and reflection improve learner engagement.

Enhance reading comprehension with metacognitive strategies. Learn how self-awareness, regulation, and reflection improve learner engagement.

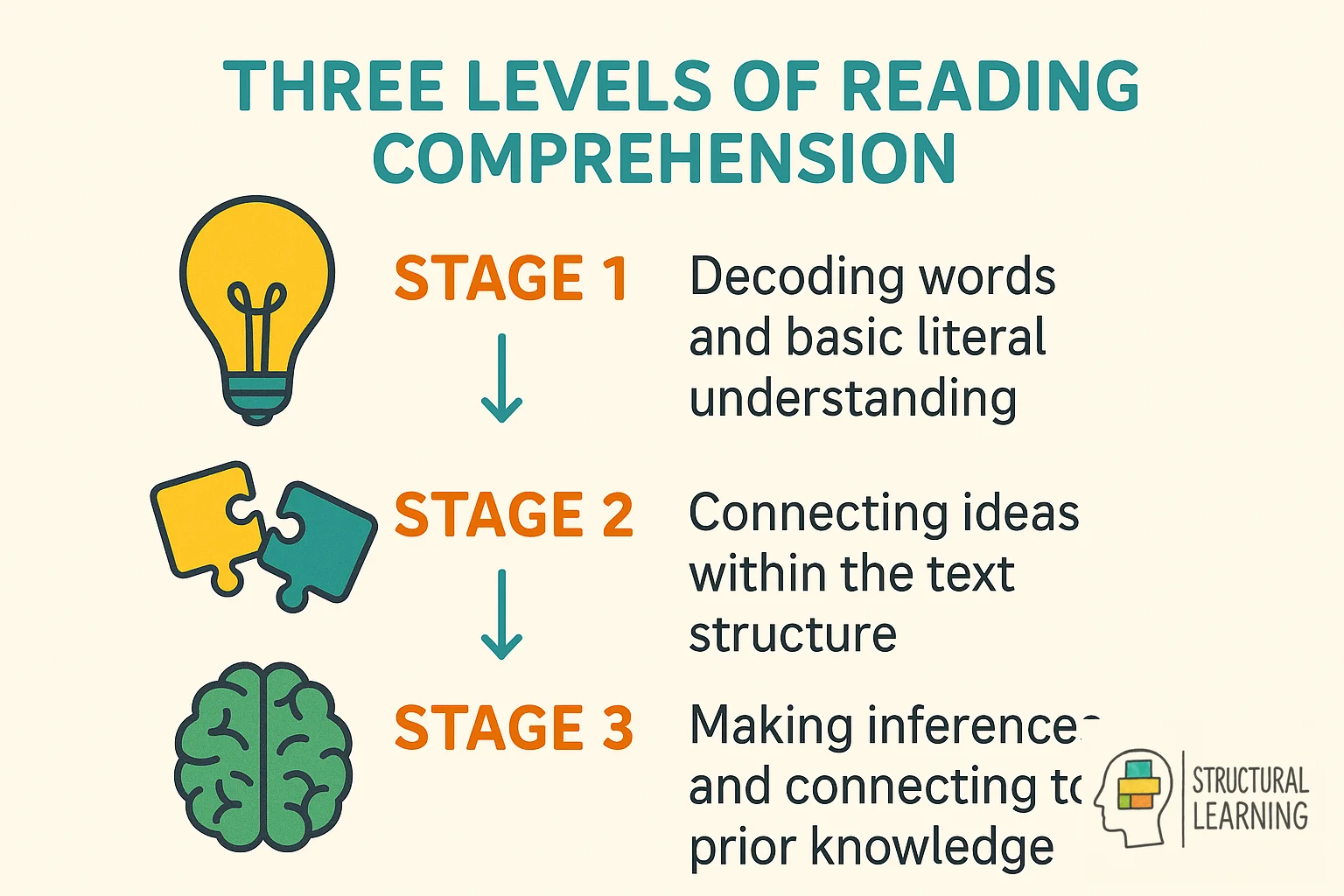

Reading isn't just about recognising words, it's about making sense of them. Strong readers do more than process text; they actively think about their thinking. This ability to monitor and regulate comprehension, known as metacognition, is what separates passive reading from deep engagement.

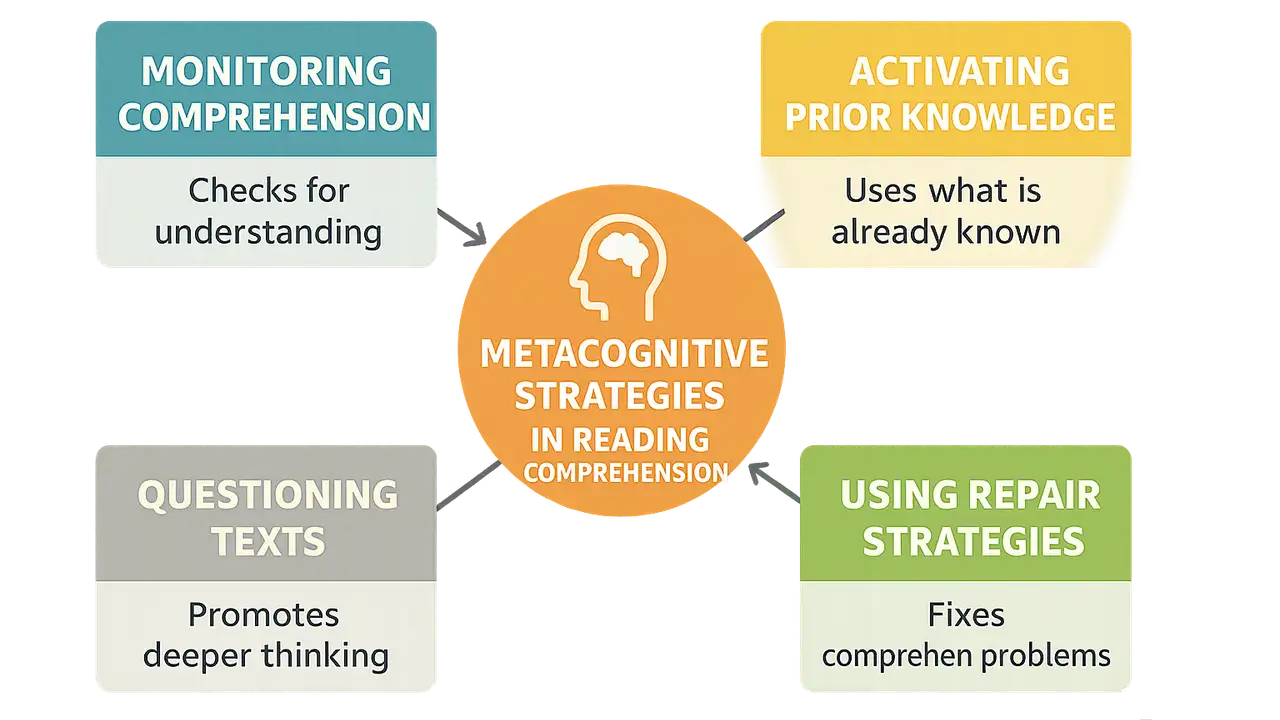

By applying metacognitive strategies, learners can identify when they understand a text, recognise when they don't, and adjust their approach accordingly. Whether it's questioning a passage, summarising key ideas, or making connections to prior knowledge, these strategies help readers take control of their learning.

reading comprehension from surface word recognition to deep understanding" loading="lazy">

reading comprehension from surface word recognition to deep understanding" loading="lazy">Research shows that encouraging metacognition leads to greater reading comprehension, improved retention, and stronger proble m-solving skills. This article explores how metacognition enhances reading comprehension, why it matters in the classroom, and how teachers can integrate these self-regulatory skills into everyday instruction to develop confident, independent readers. By making thinking visible, we enable students to become more reflective, strategic, and engaged learners.

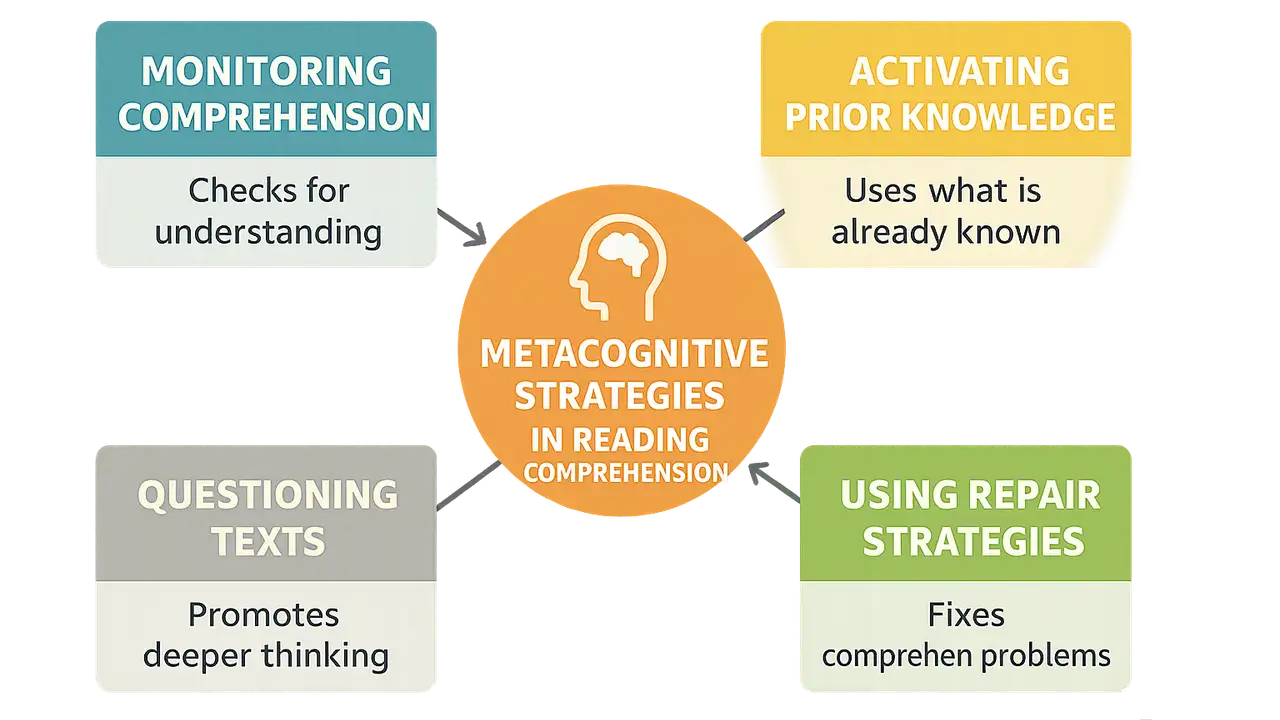

Metacognition involves thinking about one's thinking. This involves two main aspects: metacognitive knowledge and metacognitive regulation. Metacognitive knowledge refers to understanding tasks and strategies.

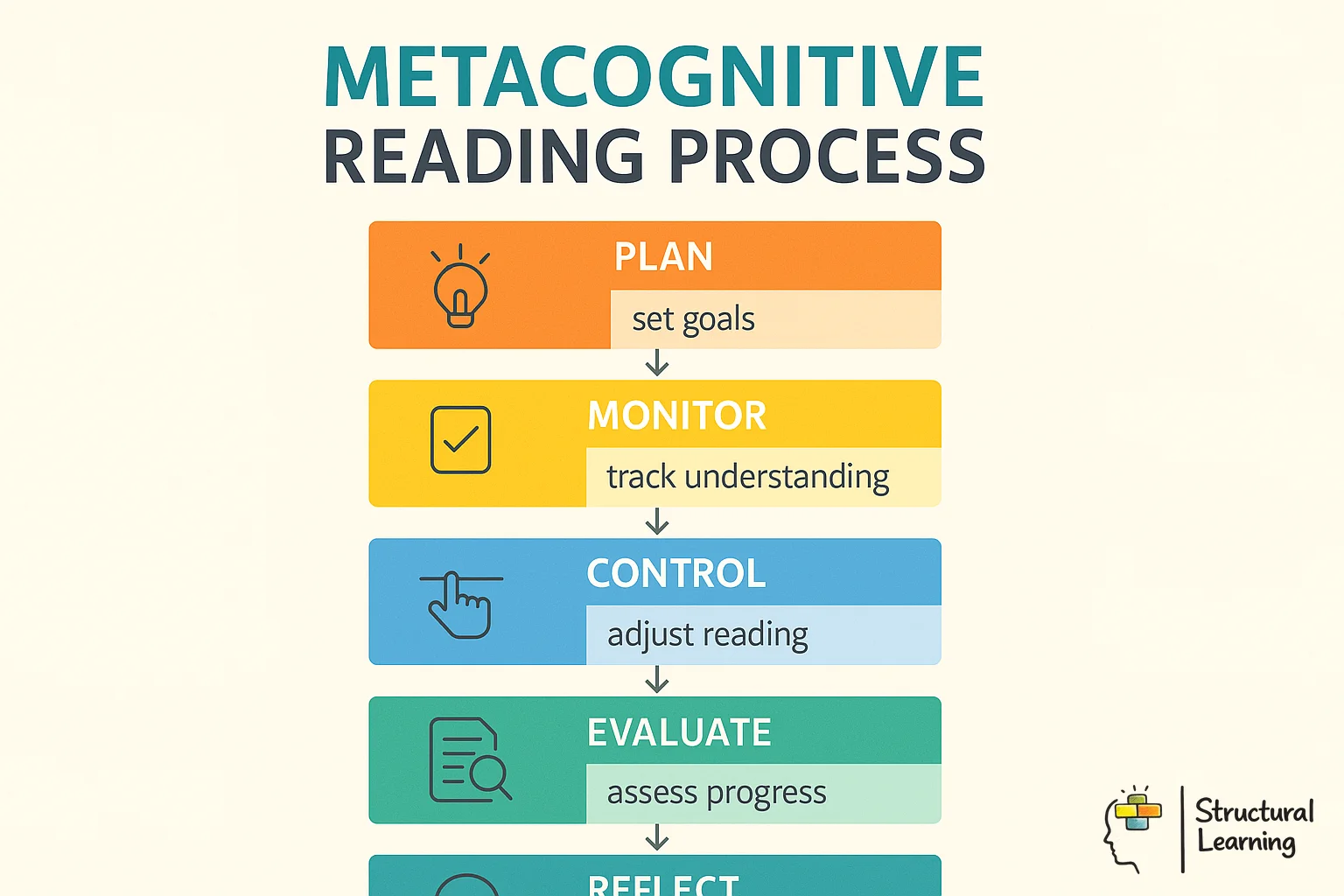

On the other hand, metacognitive regulation includes planning, monitoring, and evaluating one's learning efforts. Skilled readers use metacognitive processes to question their understanding and revisit content for better comprehension. Higher metacognitive awareness improves inferential skills and metacomprehension accuracy.

Metacognition is the ability to think about one's thinking, a crucial skill that enables learners to take control of their cognitive processes. It consists of two key components: metacognitive knowledge and metacognitive regulation.

Metacognitive knowledge involves understanding how learning works, recognising different tasks, knowing which strategies to apply, and understanding when to use them. This knowledge integrates with working memory processes to improve comprehension. Metacognitive regulation, on the other hand, refers to the active process of planning, monitoring, and evaluating one's own learning efforts.

Skilled readers naturally engage in these processes by questioning their comprehension, identifying gaps in their understanding, and adjusting their approach to make sense of complex texts.

This self-awareness leads to more effective problem-solving, stronger inferential skills, and improved metacomprehension accuracy, the ability to judge how well one has understood a text. These skills involve higher-order thinking processes that students must develop. By explicitly teaching metacognitive strategies, educators can enable students to become reflective, independent readers who take ownership of their learning.

For proficient readers, metacognition means continually monitoring their text understanding. Effective strategies enhance reading comprehension through goal setting, self-reflection, and active monitoring.

Teachers can support the development of metacognitive skills by modelling and providing concrete experiences. Conducting mini-lessons encourages reflective thinking during reading. Research shows that metacognitive strategies significantly aid students, particularly those struggling with academic texts, including learners with special educational needs. Teachers can also use concept mapping techniques to help visualize connections between ideas. Integrating metacognitive techniques across the curriculum requires direct instruction approaches and professional development for teachers to incorporate them effectively. Additionally, providing constructive feedback helps students develop better self-awareness. When students understand their progress, it enhances their motivation to persist with challenging texts.

Here is an illustrative table highlighting key differences between metacognitive knowledge and regulation:

| Aspect | Metacognitive Knowledge | Metacognitive Regulation |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Understanding one’s cognitive processes and strategies. | Managing and controlling one’s cognitive activities. |

| Focus | Knowing about cognition. | Regulating cognition. |

| Components | Declarative knowledge (knowing about things), procedural knowledge (knowing how to do things), and conditional knowledge (knowing when and why to use strategies). | Planning, monitoring, evaluating, and adjusting strategies. |

| Examples | Knowing which reading strategies work best for you; understanding the task requirements; knowing one’s own strengths and weaknesses. | Setting goals before reading; checking comprehension while reading; identifying difficulties and re-reading; evaluating whether the strategy was effective. |

Incorporating metacognitive strategies into reading instruction doesn't require a complete curriculum overhaul. Simple, targeted activities can make a significant difference:

By consistently implementing these strategies, teachers can creates a classroom culture that values metacognition and helps students to become more strategic, self-regulated readers.

The most impactful metacognitive reading strategies centre on developing students' awareness of their own comprehension processes. Self-questioning forms the foundation of effective metacognitive reading, where students learn to ask themselves "Do I understand what I've just read?" and "What don't I understand yet?" Research by Pressley and Afflerbach demonstrates that skilled readers naturally engage in this internal dialogue, constantly monitoring their comprehension and adjusting their approach when meaning breaks down.

Think-alouds represent another essential strategy, allowing teachers to model the invisible thinking processes that occur during reading. When educators verbalise their reasoning whilst reading aloud, students observe how expert readers make predictions, connect ideas, and resolve confusion. This explicit demonstration helps students develop their own metacognitive vocabulary and recognise the strategic nature of comprehension.

Classroom implementation becomes most effective when teachers introduce comprehension monitoring checklists that students can use independently. Simple prompts such as "I can visualise what's happening," "This connects to something I already know," or "I need to re-read this section" help students develop systematic self-assessment habits. Beginning with shared reading experiences where these strategies are modelled, teachers can gradually release responsibility to students, developing autonomous metacognitive readers who actively regulate their own comprehension.

Teaching students to become aware of their own thinking processes requires explicit instruction and consistent modelling. Begin by verbalising your own metacognitive processes during read-alouds, using phrases like "I'm confused here, so I need to reread this section" or "This reminds me of something I already know, which helps me understand the author's point." This think-aloud approach, supported by Pressley and Afflerbach's research on proficient readers, demonstrates how skilled readers monitor their comprehension and adjust their strategies accordingly.

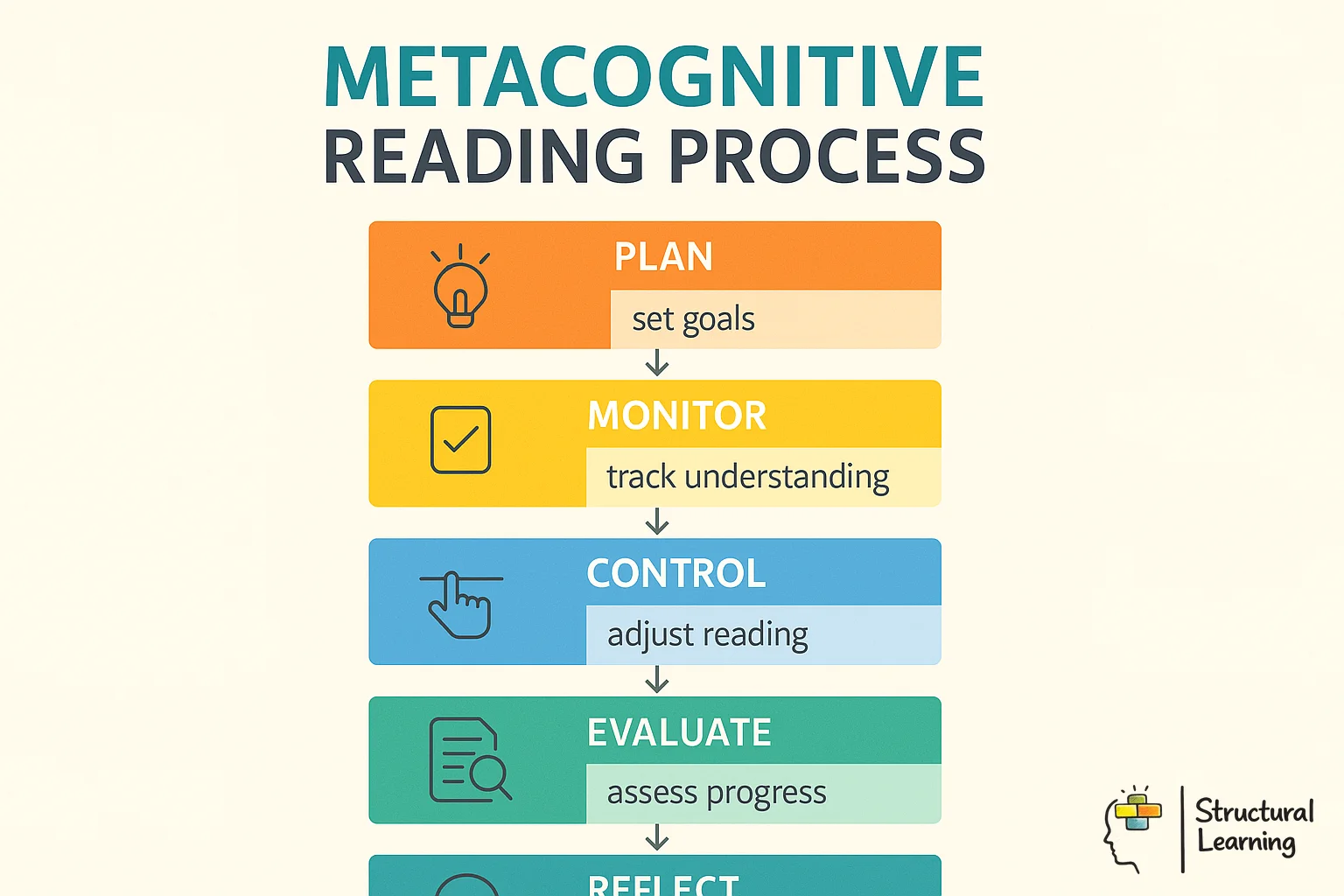

Introduce students to a simple metacognitive framework they can apply independently. Before reading, teach them to ask: "What do I already know about this topic?" During reading: "Does this make sense? Do I need to slow down or reread?" After reading: "What were the main ideas? What strategy helped me most?" Ruth Garner's work on metacognitive awareness shows that students who regularly practise this self-questioning approach demonstrate significant improvements in reading comprehension.

Create classroom routines that embed metacognitive reflection naturally. Use exit tickets asking students to identify which reading strategy they used and why, or establish "strategy circles" where pupils share moments when they recognised confusion and took action. These consistent opportunities for reflection help students internalise the habit of monitoring their own learning, transforming metacognitive awareness from an abstract concept into a practical, everyday skill.

Effective classroom implementation of metacognitive strategies requires a structured, gradual approach that builds student awareness alongside reading skills. Research by Flavell demonstrates that metacognitive awareness develops progressively, suggesting teachers should begin with explicit modelling of thinking about thinking processes during shared reading sessions. Start by verbalising your own comprehension strategies aloud, showing students how proficient readers monitor understanding, identify confusion, and select appropriate fix-up strategies when meaning breaks down.

Successful lesson planning incorporates metacognitive elements through predictable routines and visual scaffolds. Create classroom displays featuring strategy prompts such as "What am I thinking now?" and "Does this make sense?" to support student self-questioning. Anderson and Krathwohl's revised taxonomy suggests embedding metacognitive reflection at multiple lesson stages: before reading (activating prior knowledge and setting purposes), during reading (monitoring comprehension and adjusting strategies), and after reading (evaluating understanding and identifying successful approaches).

Practical implementation works best when metacognitive strategies become embedded in existing literacy frameworks rather than added as separate lessons. Introduce strategy journals where students record their thinking processes, and establish peer discussion protocols that encourage learners to share their comprehension strategies. This approach transforms classroom implementation from an additional burden into an integral component of meaningful reading instruction.

Assessing metacognitive development in reading requires teachers to look beyond traditional comprehension measures and examine how students think about their thinking during the reading process. Baker and Brown's seminal research on metacognitive awareness demonstrates that effective readers continuously monitor their understanding, yet these internal processes remain largely invisible without deliberate assessment strategies. Teachers can capture evidence of metacognitive growth through think-aloud protocols, reading journals, and strategic questioning that reveals students' awareness of their comprehension processes.

Practical assessment tools include exit tickets asking students to identify which strategies they used and why, metacognitive checklists where learners self-evaluate their strategy selection, and brief conferences focused on students' reasoning rather than just their answers. Paris and Jacobs' work on self-regulated learning suggests that regular self-assessment opportunities help students develop stronger metacognitive awareness over time.

The key to effective assessment lies in creating consistent opportunities for students to articulate their thinking processes and reflect on strategy effectiveness. Teachers should establish classroom routines where metacognitive reflection becomes habitual, such as beginning reading sessions with strategy goal-setting and concluding with brief evaluations of comprehension success. This ongoing cycle of planning, monitoring, and evaluating creates authentic assessment data whilst simultaneously strengthening students' metacognitive capabilities.

Metacognition is not just a theoretical concept; it's a practical skill that can significantly enhance reading comprehension and overall learning. By teaching students to think about their thinking, educators can helps them to become more strategic, self-regulated, and independent learners. Integrating metacognitive strategies into reading instruction requires a shift in focus, from simply delivering content to actively engaging students in their own learning processes. Through modelling, explicit instruction, and consistent practice, teachers can cultivate a classroom environment where metacognition thrives.

Ultimately, the goal is to equip students with the tools and strategies they need to navigate complex texts, identify their own learning gaps, and adjust their approach accordingly. By making thinking visible and encouraging self-reflection, we can help students develop a lifelong love of reading and a deeper understanding of the world around them. Embracing metacognition in the classroom is an investment in our students' future success, enabling them to become confident, capable, and engaged learners who are well-prepared to meet the challenges of the 21st century.

Reading isn't just about recognising words, it's about making sense of them. Strong readers do more than process text; they actively think about their thinking. This ability to monitor and regulate comprehension, known as metacognition, is what separates passive reading from deep engagement.

By applying metacognitive strategies, learners can identify when they understand a text, recognise when they don't, and adjust their approach accordingly. Whether it's questioning a passage, summarising key ideas, or making connections to prior knowledge, these strategies help readers take control of their learning.

reading comprehension from surface word recognition to deep understanding" loading="lazy">

reading comprehension from surface word recognition to deep understanding" loading="lazy">Research shows that encouraging metacognition leads to greater reading comprehension, improved retention, and stronger proble m-solving skills. This article explores how metacognition enhances reading comprehension, why it matters in the classroom, and how teachers can integrate these self-regulatory skills into everyday instruction to develop confident, independent readers. By making thinking visible, we enable students to become more reflective, strategic, and engaged learners.

Metacognition involves thinking about one's thinking. This involves two main aspects: metacognitive knowledge and metacognitive regulation. Metacognitive knowledge refers to understanding tasks and strategies.

On the other hand, metacognitive regulation includes planning, monitoring, and evaluating one's learning efforts. Skilled readers use metacognitive processes to question their understanding and revisit content for better comprehension. Higher metacognitive awareness improves inferential skills and metacomprehension accuracy.

Metacognition is the ability to think about one's thinking, a crucial skill that enables learners to take control of their cognitive processes. It consists of two key components: metacognitive knowledge and metacognitive regulation.

Metacognitive knowledge involves understanding how learning works, recognising different tasks, knowing which strategies to apply, and understanding when to use them. This knowledge integrates with working memory processes to improve comprehension. Metacognitive regulation, on the other hand, refers to the active process of planning, monitoring, and evaluating one's own learning efforts.

Skilled readers naturally engage in these processes by questioning their comprehension, identifying gaps in their understanding, and adjusting their approach to make sense of complex texts.

This self-awareness leads to more effective problem-solving, stronger inferential skills, and improved metacomprehension accuracy, the ability to judge how well one has understood a text. These skills involve higher-order thinking processes that students must develop. By explicitly teaching metacognitive strategies, educators can enable students to become reflective, independent readers who take ownership of their learning.

For proficient readers, metacognition means continually monitoring their text understanding. Effective strategies enhance reading comprehension through goal setting, self-reflection, and active monitoring.

Teachers can support the development of metacognitive skills by modelling and providing concrete experiences. Conducting mini-lessons encourages reflective thinking during reading. Research shows that metacognitive strategies significantly aid students, particularly those struggling with academic texts, including learners with special educational needs. Teachers can also use concept mapping techniques to help visualize connections between ideas. Integrating metacognitive techniques across the curriculum requires direct instruction approaches and professional development for teachers to incorporate them effectively. Additionally, providing constructive feedback helps students develop better self-awareness. When students understand their progress, it enhances their motivation to persist with challenging texts.

Here is an illustrative table highlighting key differences between metacognitive knowledge and regulation:

| Aspect | Metacognitive Knowledge | Metacognitive Regulation |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Understanding one’s cognitive processes and strategies. | Managing and controlling one’s cognitive activities. |

| Focus | Knowing about cognition. | Regulating cognition. |

| Components | Declarative knowledge (knowing about things), procedural knowledge (knowing how to do things), and conditional knowledge (knowing when and why to use strategies). | Planning, monitoring, evaluating, and adjusting strategies. |

| Examples | Knowing which reading strategies work best for you; understanding the task requirements; knowing one’s own strengths and weaknesses. | Setting goals before reading; checking comprehension while reading; identifying difficulties and re-reading; evaluating whether the strategy was effective. |

Incorporating metacognitive strategies into reading instruction doesn't require a complete curriculum overhaul. Simple, targeted activities can make a significant difference:

By consistently implementing these strategies, teachers can creates a classroom culture that values metacognition and helps students to become more strategic, self-regulated readers.

The most impactful metacognitive reading strategies centre on developing students' awareness of their own comprehension processes. Self-questioning forms the foundation of effective metacognitive reading, where students learn to ask themselves "Do I understand what I've just read?" and "What don't I understand yet?" Research by Pressley and Afflerbach demonstrates that skilled readers naturally engage in this internal dialogue, constantly monitoring their comprehension and adjusting their approach when meaning breaks down.

Think-alouds represent another essential strategy, allowing teachers to model the invisible thinking processes that occur during reading. When educators verbalise their reasoning whilst reading aloud, students observe how expert readers make predictions, connect ideas, and resolve confusion. This explicit demonstration helps students develop their own metacognitive vocabulary and recognise the strategic nature of comprehension.

Classroom implementation becomes most effective when teachers introduce comprehension monitoring checklists that students can use independently. Simple prompts such as "I can visualise what's happening," "This connects to something I already know," or "I need to re-read this section" help students develop systematic self-assessment habits. Beginning with shared reading experiences where these strategies are modelled, teachers can gradually release responsibility to students, developing autonomous metacognitive readers who actively regulate their own comprehension.

Teaching students to become aware of their own thinking processes requires explicit instruction and consistent modelling. Begin by verbalising your own metacognitive processes during read-alouds, using phrases like "I'm confused here, so I need to reread this section" or "This reminds me of something I already know, which helps me understand the author's point." This think-aloud approach, supported by Pressley and Afflerbach's research on proficient readers, demonstrates how skilled readers monitor their comprehension and adjust their strategies accordingly.

Introduce students to a simple metacognitive framework they can apply independently. Before reading, teach them to ask: "What do I already know about this topic?" During reading: "Does this make sense? Do I need to slow down or reread?" After reading: "What were the main ideas? What strategy helped me most?" Ruth Garner's work on metacognitive awareness shows that students who regularly practise this self-questioning approach demonstrate significant improvements in reading comprehension.

Create classroom routines that embed metacognitive reflection naturally. Use exit tickets asking students to identify which reading strategy they used and why, or establish "strategy circles" where pupils share moments when they recognised confusion and took action. These consistent opportunities for reflection help students internalise the habit of monitoring their own learning, transforming metacognitive awareness from an abstract concept into a practical, everyday skill.

Effective classroom implementation of metacognitive strategies requires a structured, gradual approach that builds student awareness alongside reading skills. Research by Flavell demonstrates that metacognitive awareness develops progressively, suggesting teachers should begin with explicit modelling of thinking about thinking processes during shared reading sessions. Start by verbalising your own comprehension strategies aloud, showing students how proficient readers monitor understanding, identify confusion, and select appropriate fix-up strategies when meaning breaks down.

Successful lesson planning incorporates metacognitive elements through predictable routines and visual scaffolds. Create classroom displays featuring strategy prompts such as "What am I thinking now?" and "Does this make sense?" to support student self-questioning. Anderson and Krathwohl's revised taxonomy suggests embedding metacognitive reflection at multiple lesson stages: before reading (activating prior knowledge and setting purposes), during reading (monitoring comprehension and adjusting strategies), and after reading (evaluating understanding and identifying successful approaches).

Practical implementation works best when metacognitive strategies become embedded in existing literacy frameworks rather than added as separate lessons. Introduce strategy journals where students record their thinking processes, and establish peer discussion protocols that encourage learners to share their comprehension strategies. This approach transforms classroom implementation from an additional burden into an integral component of meaningful reading instruction.

Assessing metacognitive development in reading requires teachers to look beyond traditional comprehension measures and examine how students think about their thinking during the reading process. Baker and Brown's seminal research on metacognitive awareness demonstrates that effective readers continuously monitor their understanding, yet these internal processes remain largely invisible without deliberate assessment strategies. Teachers can capture evidence of metacognitive growth through think-aloud protocols, reading journals, and strategic questioning that reveals students' awareness of their comprehension processes.

Practical assessment tools include exit tickets asking students to identify which strategies they used and why, metacognitive checklists where learners self-evaluate their strategy selection, and brief conferences focused on students' reasoning rather than just their answers. Paris and Jacobs' work on self-regulated learning suggests that regular self-assessment opportunities help students develop stronger metacognitive awareness over time.

The key to effective assessment lies in creating consistent opportunities for students to articulate their thinking processes and reflect on strategy effectiveness. Teachers should establish classroom routines where metacognitive reflection becomes habitual, such as beginning reading sessions with strategy goal-setting and concluding with brief evaluations of comprehension success. This ongoing cycle of planning, monitoring, and evaluating creates authentic assessment data whilst simultaneously strengthening students' metacognitive capabilities.

Metacognition is not just a theoretical concept; it's a practical skill that can significantly enhance reading comprehension and overall learning. By teaching students to think about their thinking, educators can helps them to become more strategic, self-regulated, and independent learners. Integrating metacognitive strategies into reading instruction requires a shift in focus, from simply delivering content to actively engaging students in their own learning processes. Through modelling, explicit instruction, and consistent practice, teachers can cultivate a classroom environment where metacognition thrives.

Ultimately, the goal is to equip students with the tools and strategies they need to navigate complex texts, identify their own learning gaps, and adjust their approach accordingly. By making thinking visible and encouraging self-reflection, we can help students develop a lifelong love of reading and a deeper understanding of the world around them. Embracing metacognition in the classroom is an investment in our students' future success, enabling them to become confident, capable, and engaged learners who are well-prepared to meet the challenges of the 21st century.

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/metacognitive-strategies-in-reading-comprehension#article","headline":"Metacognitive Strategies in Reading Comprehension","description":"Enhance reading comprehension with metacognitive strategies. Learn how self-awareness, regulation, and reflection improve learner engagement.","datePublished":"2025-02-24T16:51:58.061Z","dateModified":"2026-01-26T10:09:32.212Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/metacognitive-strategies-in-reading-comprehension"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/6950230373dfdff60ce32f63_blpqy6.webp","wordCount":4835},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/metacognitive-strategies-in-reading-comprehension#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"Metacognitive Strategies in Reading Comprehension","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/metacognitive-strategies-in-reading-comprehension"}]}]}