Growth Mindset and Metacognition: A Teacher's Guide

Explore how growth mindset and metacognition enhance learning. Implement practical strategies and activities to foster these approaches in your classroom.

Explore how growth mindset and metacognition enhance learning. Implement practical strategies and activities to foster these approaches in your classroom.

Teaching students to embrace challenges and understand their own learning processes doesn't happen by accident. Developing both Growth mindset and Metacognition in your classroom requires specific strategies and intentional daily practices that you can start implementing tomorrow. The most effective teachers combine these approaches systematically, using targeted questioning techniques, structured reflection activities, and carefully designed feedback loops. Here's your step-by-step guide to transforming how your students think about their abilities and approach their learning.

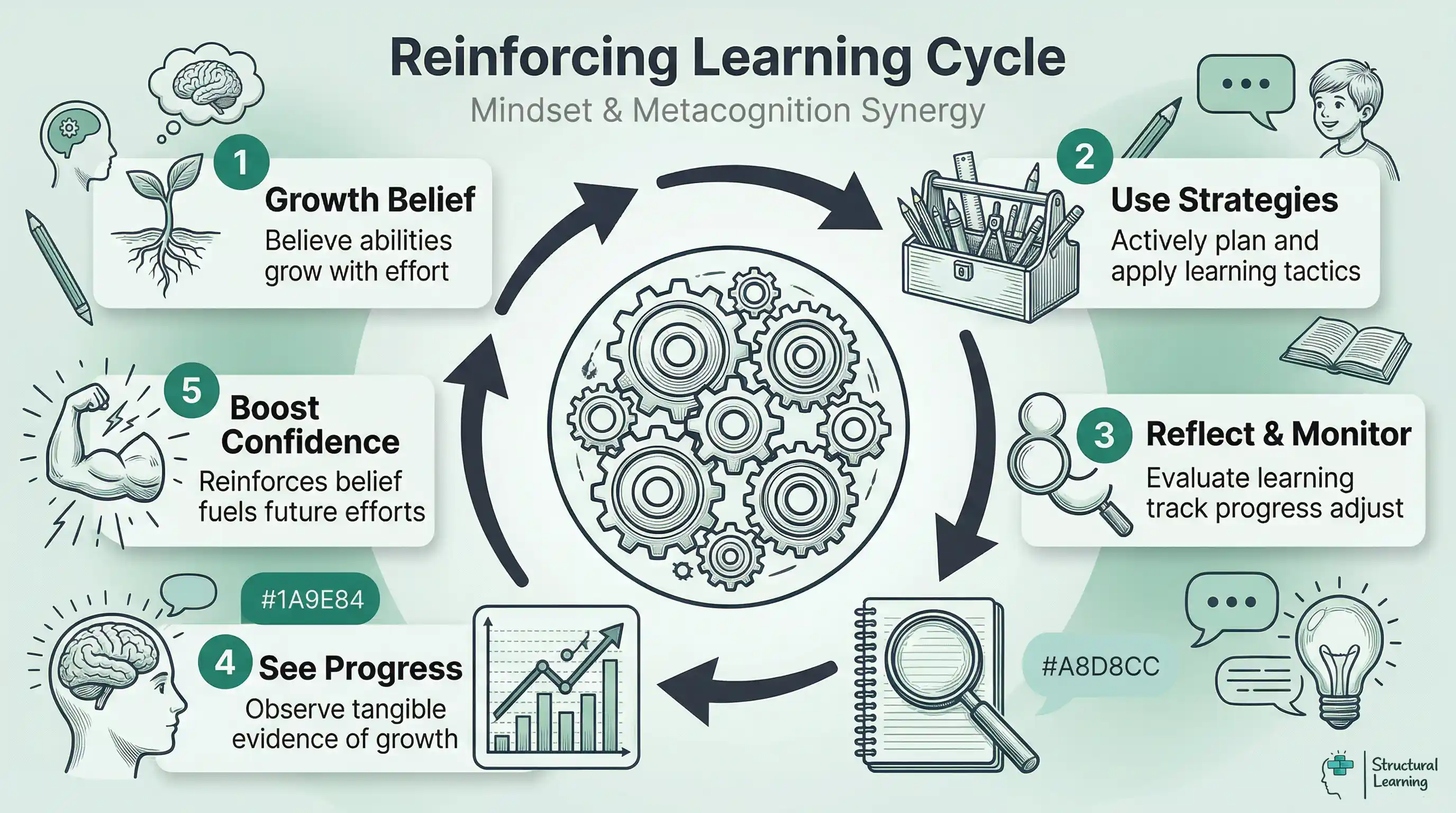

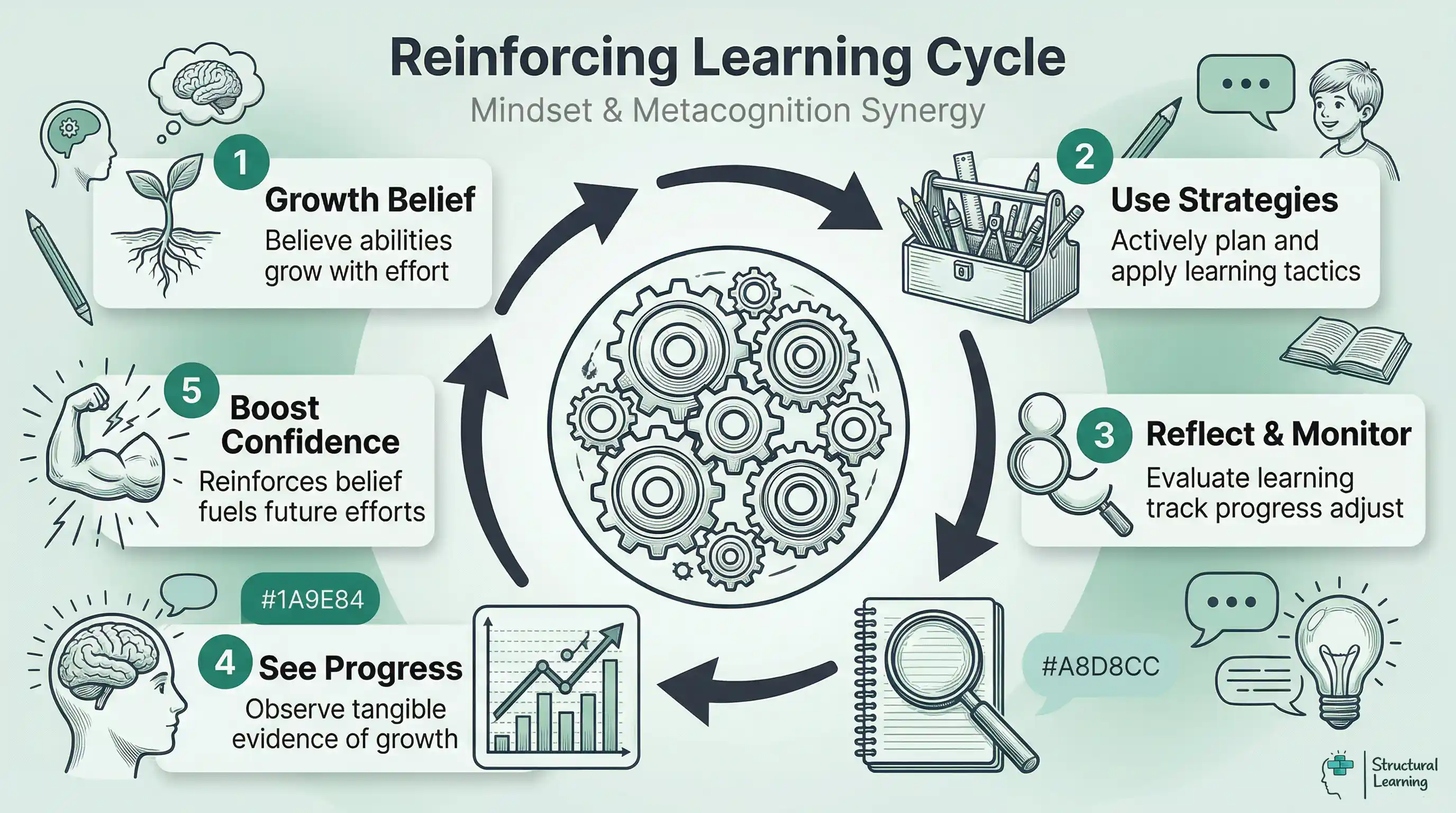

Growth mindset and metacognitive thinking reinforce each other in ways that neither achieves alone. A student with a growth mindset but no metacognitive awarenessmight work hard without strategic direction. Conversely, a metacognitively aware student with a Fixed mindset might recognise ineffective strategies but believe improvement is impossible. Together, they create a learning engine that adapts and strengthens over time.

This guide explores the research connection between these concepts, practical classroom strategies for teaching both simultaneously, and how to avoid common implementation pitfalls.

| Mindset Aspect | Fixed Belief | Growth Belief | Metacognitive Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ability | "I'm not smart enough" | "I can develop my abilities" | Monitor effort and strategy use |

| Challenge | "This is too hard" | "Challenges help me grow" | Break into manageable steps |

| Effort | "If I have to try, I must be dumb" | "Effort is the path to mastery" | Track progress over time |

| Feedback | "Criticism means I failed" | "Feedback helps me improve" | Seek specific, actionable feedback |

| Others' Success | "Their success threatens me" | "I can learn from others" | Analyse successful strategies |

Growth mindset, introduced by Carol Dweck in the 1980s, centres on the belief that intelligence and abilities can develop through dedication and hard work. Metacognition, first defined by John Flavell in 1979, involves awareness and regulation of one's own thinking processes, essentially, thinking about thinking.

These constructs intersect at a critical point: both require students to view learning as an active process they can control. A study by Dignath and Büttner (2008) found that metacognitive strategy instruction worked better with motivational components. Effect sizes increased from d = 0.69 to d = 0.83 when motivation was included.

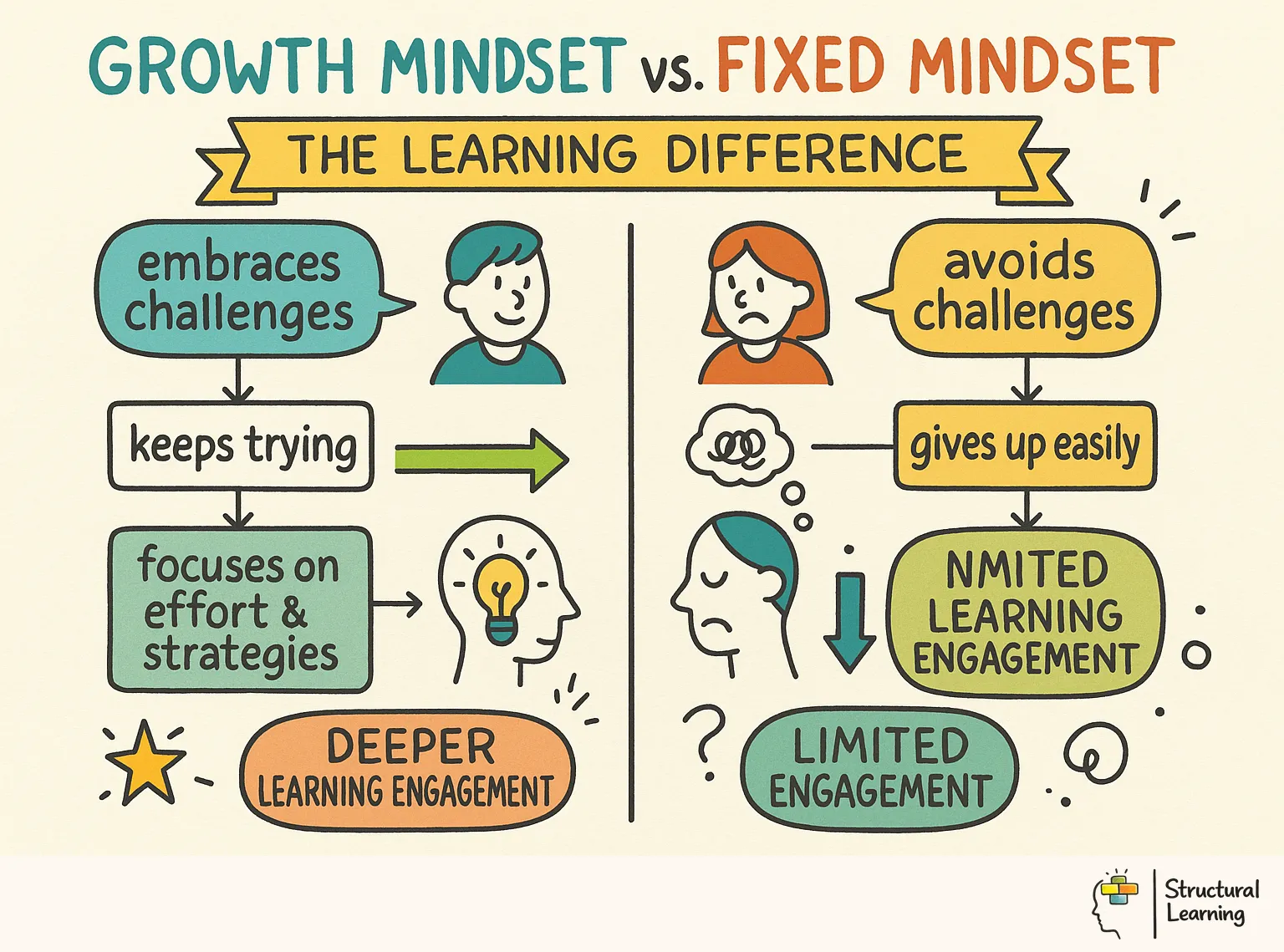

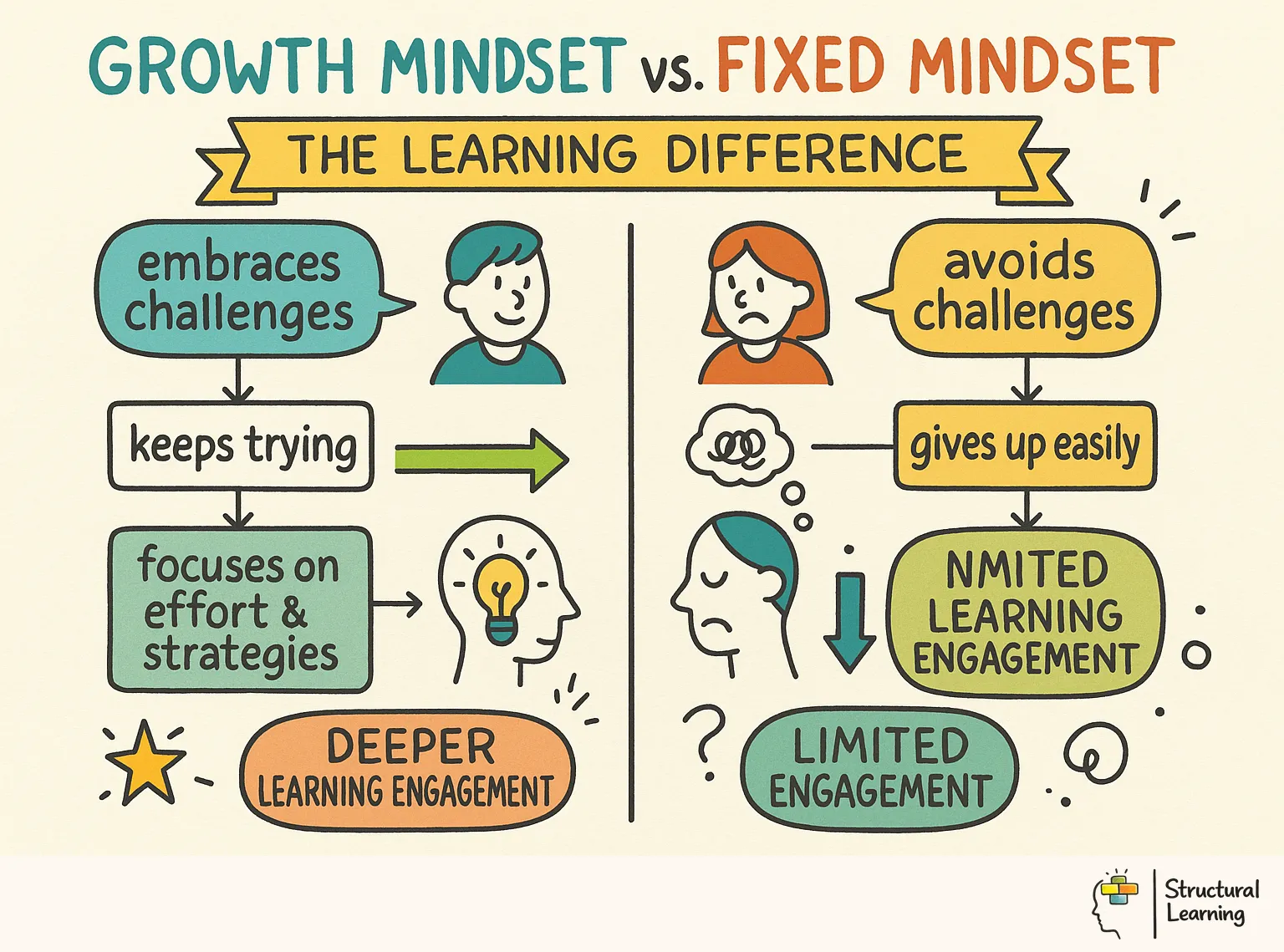

The mechanism is straightforward. Growth mindset creates the belief that effort matters. Metacognition provides the tools to make that effort strategic. Without growth mindset, students might learn Metacognitive strategies but abandon them when tasks become difficult, attributing failure to lack of ability. Without metacognition, students might embrace challenge but lack the self-monitoring skills to adjust when strategies fail.

Schunk and Zimmerman (2007) demonstrated this cooperation in their research on Self-regulated learning. Students who received both motivational orientation (growth mindset framing) and strategy instruction (metacognitive tools) outperformed those who received either intervention alone. The combined group showed higher task persistence, more accurate self-evaluation, and better strategy adaptation.

Neurological research supports this connection. Brain plasticity neural pathways strengthen through repeated, effortful practise, the biological foundation of growth mindset. Simultaneously, prefrontal cortex development enables the executive functions underlying metacognition: planning, monitoring, and evaluation. Teaching students about brain plasticity whilst developing their Metacognitive awareness helps them understand both that they can change and how to direct that change effectively.

Teaching growth mindset in isolation can produce what researchers call "empty praise" or "false growth mindset. " Students learn to say "I can grow" but lack the strategic tools to actually produce growth. A 2018 meta-analysis by Sisk and colleagues found that growth mindset interventions alone showed modest effect sizes (d = 0.08 for academic achievement), smaller than originally reported.

The problem emerges clearly in classroom observations. Students with growth mindset language but weak metacognitive skills often:

Conversely, teaching metacognition without addressing mindset beliefs can create metacognitively aware students who still underperform. These students can identify their knowledge gaps and recognise Effective strategies, but attribute their struggles to fixed limitations. They might think, "I can see that I do not understand this, and I know what good learners do, but I am not capable of that level of understanding."

This manifests in several ways:

Research by Paunesku and colleagues (2015) found that combining growth mindset with specific learning strategies produced significantly stronger academic gains than growth mindset interventions alone. The combined intervention helped students both believe in their capacity to improve and know how to enact that improvement.

Metacognitive skills provide the tangible evidence students need to maintain growth mindset beliefs, particularly when learning becomes difficult. Without this concrete Feedback, growth mindset can feel like wishful thinking.

Self-monitoring gives students real-time data about their learning. When a student can articulate "I understood the first three steps but got confused at step four," they have specific, actionable information. This precision transforms abstract growth mindset beliefs ("I can improve with effort") into concrete action ("I need to review step four using a different approach").

Metacognitive reflection creates a personal history of growth. When students regularly reflect on their learning processes, they accumulate evidence of their own improvement over time. A student who keeps a learning journal might note: "Three weeks ago I could not solve quadratic equations. Now I can solve them if I draw a visual representation first." This documented growth reinforces mindset beliefs far more effectively than teacher praise.

Strategy adaptation shows students how to translate beliefs into action. A student who learns to switch between summarisation and concept mapping when comprehension falters experiences the direct impact of strategic effort. They see how actively choosing a new approach leads to better learning outcomes. These experiences build self-efficacy, the conviction that one can execute behaviours required to produce specific performance attainments.

By embedding metacognitive routines into daily instruction, educators transform growth mindset from a feel-good slogan into an observable reality. Students see their own progress, understand the strategies that drive it, and develop the confidence to tackle increasingly complex challenges.

Integrating growth mindset and metacognition requires a shift from telling students to believe in themselves, to showing them how their beliefs translate into tangible progress. These strategies embed both concepts into everyday classroom activities:

By consistently implementing these strategies, teachers can cultivate a classroom culture that values both growth mindset and metacognition, helping students to become self-regulated, lifelong learners.

Despite their potential, growth mindset and metacognitive interventions sometimes fall short of expectations. Common pitfalls include:

To avoid these pitfalls, educators must approach growth mindset and metacognition as ongoing processes, not one-time interventions. Regular reflection, Professional development, and collaboration with colleagues can help teachers refine their practise and maximise the impact of their efforts.

The fusion of growth mindset and metacognition presents a powerful pathway for educators seeking to cultivate resilient, self-directed learners. By building the belief that abilities can grow through dedication, and by giving students tools to work through their own learning processes, we help them achieve their best.

This active cooperation goes beyond just academic achievement. It creates a lifelong love of learning, the ability to adapt to new challenges, and the confidence to pursue meaningful goals. As teachers, our role is to create environments where both growth mindset and metacognition thrive. This helps students embrace ongoing improvement and become builders of their own success.

For further academic research on this topic:

When students understand how their own learning works, they're far more likely to believe they can improve. Metacognition provides the evidence that growth mindset needs to flourish. Without this self-awareness, telling students they can "get smarter through effort" remains an abstract concept; with it, they witness their own progress in real time.

Consider what happens when a Year 8 student struggles with algebraic equations. A growth mindset alone might encourage persistence, but metacognitive skills show them exactly why their current approach isn't working. They might recognise they're rushing through problems without checking each step, or realise they understand the concept but keep making calculation errors. This awareness transforms vague frustration into specific, fixable problems.

Research by Dweck and colleagues demonstrates that students who track their thinking patterns are three times more likely to maintain growth mindset beliefs when facing setbacks. The reason is simple: metacognition makes improvement visible. When students can articulate what they've learnt, identify where they went wrong, and plan their next approach, they see their brain's capacity to change.

Try these classroom strategies to strengthen this connection. First, introduce "strategy swap" sessions where students share successful approaches to challenging tasks, explicitly linking effort to specific techniques. Second, use exit tickets that ask students to identify one thinking strategy they used today and how it helped them improve. Third, model your own metacognitive process when solving problems on the board, showing how recognising mistakes leads to better understanding.

This combination creates a powerful cycle: metacognitive awareness shows proof that abilities can develop. This strengthens growth mindset beliefs, which then motivates students to monitor and adjust their learning strategies more carefully.

Even well-intentioned teachers can stumble when introducing growth mindset and metacognition into their classrooms. The most frequent mistake involves treating these concepts as isolated lessons rather than embedded practices. Many schools dedicate a single assembly or PSHE lesson to growth mindset, then wonder why students haven't transformed overnight. Real change requires consistent integration across all subjects and daily classroom interactions.

Another critical error is oversimplifying the message. Telling students to "just try harder" or praising effort without acknowledging outcomes creates confusion and can actually reinforce fixed mindset beliefs. A Year 8 student fails a maths test but receives praise for trying hard. They get no guidance on improving their approach. They learn that effort alone equals success. This misses the important metacognitive component of strategic thinking.

Teachers also frequently underestimate the importance of modelling. Research by Hattie and Donoghue (2016) demonstrates that students adopt thinking patterns they observe in their teachers. If you respond to your own mistakes with frustration or avoid challenging tasks in front of students, your growth mindset posters become meaningless. Instead, narrate your thinking process when you encounter difficulties: "This new marking software is confusing me. Let me break down what I need to learn step by step."

Finally, many educators abandon these approaches too quickly. Building growth mindset with metacognitive awareness typically takes a full term of consistent practise before students internalise these habits. Quick wins are rare. Sustainable change requires patience and systematic reinforcement through questioning techniques, reflection journals, and structured peer feedback sessions. These must clearly connect effort, strategy, and improvement.

Combining growth mindset with metacognitive practise transforms abstract concepts into concrete classroom actions. Rather than teaching these skills separately, effective teachers combine them through careful questioning and structured activities. This helps students recognise both their learning potential and their thinking processes.

Start with the "Think Aloud Protocol" during problem-solving activities. Model your own thinking by verbalising your process: "I'm stuck here, so I'll try a different approach. This mistake shows me what doesn't work, which helps me narrow down what might." Then ask students to narrate their own thinking whilst tackling challenging tasks. This simultaneous development of metacognitive awareness and growth mindset shows students that struggle is both normal and informative.

Use "Learning Journals" where students track not just what they learnt, but how they learnt it. Prompt entries with questions like: "What strategy did you use today? How did it work? What will you try differently tomorrow? Research by Dignath and Büttner (2018) shows that students who regularly reflect on their learning strategies do better. These students also acknowledge their capacity for improvement. They show much greater academic gains than those receiving traditional instruction.

Create "Strategy Swap Sessions" where students share successful approaches with peers facing similar challenges. When a student explains how they overcame a specific difficulty, they reinforce their own metacognitive understanding whilst modelling growth mindset behaviours for others. This peer-to-peer exchange proves particularly powerful; students often accept capability messages more readily from classmates than from teachers.

These integrated approaches ensure students don't just believe they can improve; they understand exactly how to make that improvement happen through strategic thinking and purposeful practise.

Many well-intentioned teachers inadvertently sabotage their efforts to develop growth mindset and metacognition in their classrooms. Understanding these common pitfalls helps you sidestep months of wasted time and prevent students from developing counterproductive habits that are difficult to reverse.

The most damaging mistake is praising effort without linking it to outcomes. When teachers say "well done for trying hard" after repeated failure, students quickly learn that effort alone excuses poor performance. Instead, combine effort praise with strategy discussions: "I noticed you tried three different methods to solve that problem. Which one brought you closest to the answer?" This approach validates persistence whilst directing attention to metacognitive evaluation.

Another critical error occurs when teachers present growth mindset as a magic solution rather than hard work. Students who hear "you can do anything if you believe" without learning specific improvement strategies often experience what Carol Dweck calls "false growth mindset". They say the words but give up the belief when truly challenged. Combat this by teaching concrete metacognitive tools alongside growth mindset messages. For instance, introduce the "strategy swap" routine where students must identify why their current approach isn't working before trying something new.

Finally, avoid creating a classroom culture where fixed mindset thinking becomes taboo. When students can't express genuine struggles or doubts, they hide their fixed mindset thoughts rather than examining them. Research from the University of Portsmouth shows that students who openly discuss fixed mindset triggers develop stronger resilience than those in "growth mindset only" environments. Establish regular "mindset check-ins" where students can honestly assess their thinking without judgement, then collaboratively develop strategies to shift unhelpful beliefs.

When students develop metacognitive awareness, they create the perfect conditions for growth mindset to flourish. Rather than simply telling themselves "I can improve," metacognitive students understand exactly how and why improvement happens, making their belief in growth concrete rather than wishful thinking.

Consider what happens when a Year 8 student struggles with algebraic equations. Without metacognition, a growth mindset message of "keep trying" often leads to repeated failure using the same ineffective approach. However, when that same student learns to monitor their thinking process, they might notice: "I keep making errors when I move terms across the equals sign." This awareness turns effort into focused practise on specific skills.

Research from the Education Endowment Foundation demonstrates that students who regularly reflect on their learning strategies show greater resilience when facing setbacks. They view mistakes as diagnostic tools rather than evidence of inability. For instance, teaching students to complete a simple "strategy log" after each maths problem helps them identify which approaches work best for different question types. Over time, this builds genuine confidence based on evidence, not empty encouragement.

In practise, you can strengthen this connection by modelling your own metacognitive processes whilst demonstrating growth mindset. When solving a problem on the board, narrate your thinking: "This method isn't working, so I'll try factorising instead." Show students that monitoring and adjusting strategies is what good learners do, not a sign of weakness. This approach helps students internalise both the belief that abilities can develop and the practical tools to make that development happen.

Teaching growth mindset without metacognitive strategies leaves students enthusiastic but directionless. They might believe they can improve, yet lack the tools to analyse why they're struggling or how to adjust their approach. Picture a Year 8 student who embraces the "power of yet" philosophy but repeatedly uses the same ineffective revision method, believing that mere persistence will eventually work. Without metacognitive awareness, their efforts become exhausting rather than productive.

Conversely, teaching metacognition without growth mindset creates strategically aware students who give up at the first hurdle. These pupils can identify when a learning strategy isn't working and might even know alternative approaches, but their fixed beliefs about ability prevent them from trying. A Year 10 student might recognise that mind mapping helps them understand difficult topics better than linear notes. Yet they still conclude "I'm just not a science person" when faced with challenging chemistry concepts.

Research by Dweck and colleagues (2014) found that growth mindset interventions showed minimal impact when students lacked concrete strategies for improvement. Similarly, Zimmerman's work on self-Regulated learning demonstrates that metacognitive skills remain underutilised when students believe their abilities are fixed. The magic happens when both work together: growth mindset provides the motivation to persist, whilst metacognition offers the roadmap for improvement.

In practise, this means explicitly linking belief to strategy. When teaching fraction division, don't just encourage students to "keep trying"; show them how to monitor their understanding step-by-step, identify confusion points, and select appropriate fix-up strategies. This combination transforms vague encouragement into actionable learning paths that students can follow independently.

Most teachers notice initial changes in student language and behaviour within 2-3 weeks of consistent implementation. However, deeper shifts in learning habits and genuine confidence typically develop over a full term or academic year. The key is maintaining daily practices rather than expecting immediate transformation.

The Dunning-Kruger effect (Kruger and Dunning, 1999) reveals that novice learners consistently overestimate their understanding, while expert learners underestimate theirs. This miscalibration makes explicit metacognitive training essential for accurate self-assessment.

Try asking 'What strategy are you using right now?' and 'How do you know if it's working?' during independent work time. Before tackling problems, ask 'What do you already know about this?' and after completion, 'What would you do differently next time?' These questions become automatic with practise.

Replace generic praise like 'well done' with specific feedback about process and strategy. Say 'I noticed you tried three different approaches when you got stuck' or 'Your revision strategy of testing yourself really paid off here.' This highlights the connection between specific actions and outcomes.

Start with very brief, structured reflections using sentence starters or tick-box formats rather than open-ended questions. Make reflection feel purposeful by showing students how their insights lead to better performance. Gradually increase reflection time as students see the value in the process.

Begin with small, achievable tasks where students can experience quick wins using metacognitive approaches. Focus on documenting evidence of improvement through learning journals or progress tracking. Once students see concrete proof that strategies work, their beliefs about their abilities often begin to shift naturally.

Analysis of a STEM Based Flipped Classroom Learning Model for Enhancing Metacognition and Student Learning Outcomes in Buffer Solution Topic View study ↗

Santi Puji Lestari et al. (2025)

Researchers tested a STEM-based flipped classroom approach to teach complex chemistry concepts like buffer solutions, finding that this model significantly improved both student achievement and metacognitive skills. The flipped format allowed students to engage with content at their own pace while developing better awareness of their learning processes. This approach offers science teachers a practical way to tackle abstract concepts while simultaneously building students' ability to monitor and regulate their own understanding.

GAMIFICATION AS A PEDAGOGICAL STRATEGY: ENHANCING STUDENT PERFORMANCE, MINDSET, AND METACOGNITION View study ↗

Dr.M.ILAYA Kanmani Nanmozhi & Dr.S.GUNASEKARAN (2025)

This large-scale study with 440 university students demonstrated that incorporating game elements into learning significantly improved academic performance, built growth mindset, and enhanced metacognitive abilities. Students in gamified learning environments showed greater engagement and developed better self-awareness about their learning strategies. Teachers can apply these findings by integrating game mechanics like points, challenges, and progress tracking to create more motivating learning experiences that also build students' Thinking skills.

A values-aligned intervention fosters growth mindset-supportive teaching and reduces inequality in educational outcomes View study ↗

31 citations

Cameron A. Hecht et al. (2023)

This groundbreaking study showed that when high school teachers participated in a values-based intervention focused on growth mindset principles, they adopted more supportive classroom practices that particularly benefited students from disadvantaged backgrounds. The intervention successfully reduced achievement gaps by helping teachers demonstrate genuine belief in all students' capacity to learn and improve. This research provides concrete evidence that growth mindset training for teachers can be a effective method for promoting educational equity.

Video games and metacognition in the classroom for the development of 21st century skills: a systematic review View study ↗

6 citations

Mirian Checa-Romero & José Miguel Giménez-Lozano (2025)

This Thorough review analysed how commercial video games used in educational settings can effectively develop students' metacognitive skills and 21st century competencies. The research found that strategic, complex games naturally promote self-reflection, planning, and monitoring of learning processes. Teachers can use this finding by thoughtfully incorporating appropriate commercial games into their curriculum as tools for building students' metacognitive awareness while engaging them in meaningful learning experiences.

Generate an 8-week metacognition roadmap tailored to your key stage, subject, and current practice level.

These peer-reviewed studies provide the research foundation for the strategies discussed in this article:

Integrating cognition, self-regulation, motivation, and metacognition: a framework of post-pandemic flipped classroom design View study ↗

4 citations

Yan Shen et al. (2025)

This research provides teachers with a thorough framework for designing effective flipped classrooms that combine thinking skills, self-regulation, motivation, and metacognition in the post-COVID era. The study addresses the gap between flipped classroom popularity and actual implementation guidance, offering educators a research-backed blueprint for creating meaningful blended learning experiences. This framework helps teachers move beyond simply flipping content to creating truly significant learning environments that develop students' ability to think about their own thinking.

A Framework of College Student Buy-in to Evidence-Based Teaching Practices in STEM: The Roles of Trust and Growth Mindset View study ↗

20 citations

C. Wang et al. (2021)

This study reveals that students' trust in their teachers and their growth mindset significantly influence how willing they are to engage with research-Proven teaching methods in science and math classes. The when students trust their instructors and believe they can improve their abilities, they're more likely to embrace active learning strategies and ultimately perform better academically. For STEM educators, this highlights the important importance of building strong relationships with students and explicitly encouraging growth mindset beliefs to make evidence-based teaching practices truly effective.

Improving self‐regulated learning: A mixed‐methods study on GAI's impact on undergraduate task strategies and metacognition View study ↗

6 citations

Ping Wang et al. (2025)

This eight-week study with 40 undergraduate students found that using AI chatbot tools can improve students' ability to regulate their own learning and become more aware of their thinking processes, particularly in writing tasks. The when students interact with generative AI tools strategically, they develop more diverse learning approaches and stronger metacognitive skills. This finding offers teachers practical insights into how AI can be used not just as a content generator, but as a tool to help students become more independent and reflective learners.

Implicit theories of self-regulated learning: Interplay with students' achievement goals, learning strategies, and metacognition. View study ↗

56 citations

S. Hertel & Yves Karlen (2020)

This research explores how students' beliefs about whether learning skills can be improved affects their motivation, study strategies, and self-awareness as learners. The study found that students who believe learning strategies are malleable and important are more likely to set mastery goals, use effective study techniques, and monitor their own thinking processes. Teachers can use these insights to explicitly teach students that learning skills are developable, which can transform how students approach challenges and setbacks in their academic work.

Self-regulation in learning: The role of language and formative assessment View study ↗

2 citations

Siti Zulaiha (2019)

This study examines how language instruction and ongoing assessment can help students take greater control of their own learning process, particularly in English language teaching contexts. The research highlights the challenge many teachers face in shifting from content-focused instruction to helping students develop independent learning strategies. The findings suggest that combining explicit language instruction with Formative assessment practices can create more self-directed learners who actively monitor and adjust their own progress.

Shifting the mindset culture to address global educational disparities View study ↗

23 citations

Cameron A. Hecht et al. (2023)

This research argues that focusing only on changing individual students' mindsets isn't enough, we also need to transform the entire classroom and school culture around learning beliefs. The study shows that when schools create environments where growth mindset thinking is embedded in policies, practices, and everyday interactions, students from disadvantaged backgrounds benefit most. For teachers, this means thinking beyond individual student interventions to consider how grading practices, classroom discussions, and school-wide messages either support or undermine growth mindset development.

Optimizing self‐regulated learning: A mixed‐methods study on GAI's impact on undergraduate task strategies and metacognition View study ↗

6 citations

Ping Wang et al. (2025)

This current study explored how AI chatbot tools can help college students become better self-directed learners, particularly in writing tasks. Over eight weeks, students who used the AI tool showed improved ability to plan their learning, monitor their progress, and choose more diverse strategies for tackling assignments. These findings suggest that when thoughtfully integrated, AI tools can actually improve rather than replace critical thinking skills, offering teachers new ways to support students' metacognitive development.

The Role of Effective Feedback in Enhancing Student Academic Achievement through Virtual Formative Assessment: A thorough Study View study ↗

Muhammad Usman Zahid & Mahendran AlManiam (2025)

This large-scale study with 365 high school students demonstrates that the quality of feedback, not just the quantity, significantly impacts student achievement in digital learning environments. Students performed better when they received feedback that was easy to understand, practically useful, timely, and motivating rather than discouraging. For teachers navigating online and hybrid learning, this research provides concrete guidance on crafting digital feedback that truly moves student learning forwards.

Implicit theories of self-regulated learning: Interplay with students' achievement goals, learning strategies, and metacognition. View study ↗

56 citations

S. Hertel & Yves Karlen (2020)

This study reveals that students' beliefs about whether learning skills can be improved are just as important as their beliefs about intelligence, and these beliefs directly influence how they approach studying and self-reflection. Students who believed that learning strategies and self-regulation skills could be developed were more likely to set meaningful goals, try new study techniques, and monitor their own learning progress. This research gives teachers insight into how addressing students' beliefs about learning itself can improve their academic strategies and metacognitive awareness.

Teaching students to embrace challenges and understand their own learning processes doesn't happen by accident. Developing both Growth mindset and Metacognition in your classroom requires specific strategies and intentional daily practices that you can start implementing tomorrow. The most effective teachers combine these approaches systematically, using targeted questioning techniques, structured reflection activities, and carefully designed feedback loops. Here's your step-by-step guide to transforming how your students think about their abilities and approach their learning.

Growth mindset and metacognitive thinking reinforce each other in ways that neither achieves alone. A student with a growth mindset but no metacognitive awarenessmight work hard without strategic direction. Conversely, a metacognitively aware student with a Fixed mindset might recognise ineffective strategies but believe improvement is impossible. Together, they create a learning engine that adapts and strengthens over time.

This guide explores the research connection between these concepts, practical classroom strategies for teaching both simultaneously, and how to avoid common implementation pitfalls.

| Mindset Aspect | Fixed Belief | Growth Belief | Metacognitive Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ability | "I'm not smart enough" | "I can develop my abilities" | Monitor effort and strategy use |

| Challenge | "This is too hard" | "Challenges help me grow" | Break into manageable steps |

| Effort | "If I have to try, I must be dumb" | "Effort is the path to mastery" | Track progress over time |

| Feedback | "Criticism means I failed" | "Feedback helps me improve" | Seek specific, actionable feedback |

| Others' Success | "Their success threatens me" | "I can learn from others" | Analyse successful strategies |

Growth mindset, introduced by Carol Dweck in the 1980s, centres on the belief that intelligence and abilities can develop through dedication and hard work. Metacognition, first defined by John Flavell in 1979, involves awareness and regulation of one's own thinking processes, essentially, thinking about thinking.

These constructs intersect at a critical point: both require students to view learning as an active process they can control. A study by Dignath and Büttner (2008) found that metacognitive strategy instruction worked better with motivational components. Effect sizes increased from d = 0.69 to d = 0.83 when motivation was included.

The mechanism is straightforward. Growth mindset creates the belief that effort matters. Metacognition provides the tools to make that effort strategic. Without growth mindset, students might learn Metacognitive strategies but abandon them when tasks become difficult, attributing failure to lack of ability. Without metacognition, students might embrace challenge but lack the self-monitoring skills to adjust when strategies fail.

Schunk and Zimmerman (2007) demonstrated this cooperation in their research on Self-regulated learning. Students who received both motivational orientation (growth mindset framing) and strategy instruction (metacognitive tools) outperformed those who received either intervention alone. The combined group showed higher task persistence, more accurate self-evaluation, and better strategy adaptation.

Neurological research supports this connection. Brain plasticity neural pathways strengthen through repeated, effortful practise, the biological foundation of growth mindset. Simultaneously, prefrontal cortex development enables the executive functions underlying metacognition: planning, monitoring, and evaluation. Teaching students about brain plasticity whilst developing their Metacognitive awareness helps them understand both that they can change and how to direct that change effectively.

Teaching growth mindset in isolation can produce what researchers call "empty praise" or "false growth mindset. " Students learn to say "I can grow" but lack the strategic tools to actually produce growth. A 2018 meta-analysis by Sisk and colleagues found that growth mindset interventions alone showed modest effect sizes (d = 0.08 for academic achievement), smaller than originally reported.

The problem emerges clearly in classroom observations. Students with growth mindset language but weak metacognitive skills often:

Conversely, teaching metacognition without addressing mindset beliefs can create metacognitively aware students who still underperform. These students can identify their knowledge gaps and recognise Effective strategies, but attribute their struggles to fixed limitations. They might think, "I can see that I do not understand this, and I know what good learners do, but I am not capable of that level of understanding."

This manifests in several ways:

Research by Paunesku and colleagues (2015) found that combining growth mindset with specific learning strategies produced significantly stronger academic gains than growth mindset interventions alone. The combined intervention helped students both believe in their capacity to improve and know how to enact that improvement.

Metacognitive skills provide the tangible evidence students need to maintain growth mindset beliefs, particularly when learning becomes difficult. Without this concrete Feedback, growth mindset can feel like wishful thinking.

Self-monitoring gives students real-time data about their learning. When a student can articulate "I understood the first three steps but got confused at step four," they have specific, actionable information. This precision transforms abstract growth mindset beliefs ("I can improve with effort") into concrete action ("I need to review step four using a different approach").

Metacognitive reflection creates a personal history of growth. When students regularly reflect on their learning processes, they accumulate evidence of their own improvement over time. A student who keeps a learning journal might note: "Three weeks ago I could not solve quadratic equations. Now I can solve them if I draw a visual representation first." This documented growth reinforces mindset beliefs far more effectively than teacher praise.

Strategy adaptation shows students how to translate beliefs into action. A student who learns to switch between summarisation and concept mapping when comprehension falters experiences the direct impact of strategic effort. They see how actively choosing a new approach leads to better learning outcomes. These experiences build self-efficacy, the conviction that one can execute behaviours required to produce specific performance attainments.

By embedding metacognitive routines into daily instruction, educators transform growth mindset from a feel-good slogan into an observable reality. Students see their own progress, understand the strategies that drive it, and develop the confidence to tackle increasingly complex challenges.

Integrating growth mindset and metacognition requires a shift from telling students to believe in themselves, to showing them how their beliefs translate into tangible progress. These strategies embed both concepts into everyday classroom activities:

By consistently implementing these strategies, teachers can cultivate a classroom culture that values both growth mindset and metacognition, helping students to become self-regulated, lifelong learners.

Despite their potential, growth mindset and metacognitive interventions sometimes fall short of expectations. Common pitfalls include:

To avoid these pitfalls, educators must approach growth mindset and metacognition as ongoing processes, not one-time interventions. Regular reflection, Professional development, and collaboration with colleagues can help teachers refine their practise and maximise the impact of their efforts.

The fusion of growth mindset and metacognition presents a powerful pathway for educators seeking to cultivate resilient, self-directed learners. By building the belief that abilities can grow through dedication, and by giving students tools to work through their own learning processes, we help them achieve their best.

This active cooperation goes beyond just academic achievement. It creates a lifelong love of learning, the ability to adapt to new challenges, and the confidence to pursue meaningful goals. As teachers, our role is to create environments where both growth mindset and metacognition thrive. This helps students embrace ongoing improvement and become builders of their own success.

For further academic research on this topic:

When students understand how their own learning works, they're far more likely to believe they can improve. Metacognition provides the evidence that growth mindset needs to flourish. Without this self-awareness, telling students they can "get smarter through effort" remains an abstract concept; with it, they witness their own progress in real time.

Consider what happens when a Year 8 student struggles with algebraic equations. A growth mindset alone might encourage persistence, but metacognitive skills show them exactly why their current approach isn't working. They might recognise they're rushing through problems without checking each step, or realise they understand the concept but keep making calculation errors. This awareness transforms vague frustration into specific, fixable problems.

Research by Dweck and colleagues demonstrates that students who track their thinking patterns are three times more likely to maintain growth mindset beliefs when facing setbacks. The reason is simple: metacognition makes improvement visible. When students can articulate what they've learnt, identify where they went wrong, and plan their next approach, they see their brain's capacity to change.

Try these classroom strategies to strengthen this connection. First, introduce "strategy swap" sessions where students share successful approaches to challenging tasks, explicitly linking effort to specific techniques. Second, use exit tickets that ask students to identify one thinking strategy they used today and how it helped them improve. Third, model your own metacognitive process when solving problems on the board, showing how recognising mistakes leads to better understanding.

This combination creates a powerful cycle: metacognitive awareness shows proof that abilities can develop. This strengthens growth mindset beliefs, which then motivates students to monitor and adjust their learning strategies more carefully.

Even well-intentioned teachers can stumble when introducing growth mindset and metacognition into their classrooms. The most frequent mistake involves treating these concepts as isolated lessons rather than embedded practices. Many schools dedicate a single assembly or PSHE lesson to growth mindset, then wonder why students haven't transformed overnight. Real change requires consistent integration across all subjects and daily classroom interactions.

Another critical error is oversimplifying the message. Telling students to "just try harder" or praising effort without acknowledging outcomes creates confusion and can actually reinforce fixed mindset beliefs. A Year 8 student fails a maths test but receives praise for trying hard. They get no guidance on improving their approach. They learn that effort alone equals success. This misses the important metacognitive component of strategic thinking.

Teachers also frequently underestimate the importance of modelling. Research by Hattie and Donoghue (2016) demonstrates that students adopt thinking patterns they observe in their teachers. If you respond to your own mistakes with frustration or avoid challenging tasks in front of students, your growth mindset posters become meaningless. Instead, narrate your thinking process when you encounter difficulties: "This new marking software is confusing me. Let me break down what I need to learn step by step."

Finally, many educators abandon these approaches too quickly. Building growth mindset with metacognitive awareness typically takes a full term of consistent practise before students internalise these habits. Quick wins are rare. Sustainable change requires patience and systematic reinforcement through questioning techniques, reflection journals, and structured peer feedback sessions. These must clearly connect effort, strategy, and improvement.

Combining growth mindset with metacognitive practise transforms abstract concepts into concrete classroom actions. Rather than teaching these skills separately, effective teachers combine them through careful questioning and structured activities. This helps students recognise both their learning potential and their thinking processes.

Start with the "Think Aloud Protocol" during problem-solving activities. Model your own thinking by verbalising your process: "I'm stuck here, so I'll try a different approach. This mistake shows me what doesn't work, which helps me narrow down what might." Then ask students to narrate their own thinking whilst tackling challenging tasks. This simultaneous development of metacognitive awareness and growth mindset shows students that struggle is both normal and informative.

Use "Learning Journals" where students track not just what they learnt, but how they learnt it. Prompt entries with questions like: "What strategy did you use today? How did it work? What will you try differently tomorrow? Research by Dignath and Büttner (2018) shows that students who regularly reflect on their learning strategies do better. These students also acknowledge their capacity for improvement. They show much greater academic gains than those receiving traditional instruction.

Create "Strategy Swap Sessions" where students share successful approaches with peers facing similar challenges. When a student explains how they overcame a specific difficulty, they reinforce their own metacognitive understanding whilst modelling growth mindset behaviours for others. This peer-to-peer exchange proves particularly powerful; students often accept capability messages more readily from classmates than from teachers.

These integrated approaches ensure students don't just believe they can improve; they understand exactly how to make that improvement happen through strategic thinking and purposeful practise.

Many well-intentioned teachers inadvertently sabotage their efforts to develop growth mindset and metacognition in their classrooms. Understanding these common pitfalls helps you sidestep months of wasted time and prevent students from developing counterproductive habits that are difficult to reverse.

The most damaging mistake is praising effort without linking it to outcomes. When teachers say "well done for trying hard" after repeated failure, students quickly learn that effort alone excuses poor performance. Instead, combine effort praise with strategy discussions: "I noticed you tried three different methods to solve that problem. Which one brought you closest to the answer?" This approach validates persistence whilst directing attention to metacognitive evaluation.

Another critical error occurs when teachers present growth mindset as a magic solution rather than hard work. Students who hear "you can do anything if you believe" without learning specific improvement strategies often experience what Carol Dweck calls "false growth mindset". They say the words but give up the belief when truly challenged. Combat this by teaching concrete metacognitive tools alongside growth mindset messages. For instance, introduce the "strategy swap" routine where students must identify why their current approach isn't working before trying something new.

Finally, avoid creating a classroom culture where fixed mindset thinking becomes taboo. When students can't express genuine struggles or doubts, they hide their fixed mindset thoughts rather than examining them. Research from the University of Portsmouth shows that students who openly discuss fixed mindset triggers develop stronger resilience than those in "growth mindset only" environments. Establish regular "mindset check-ins" where students can honestly assess their thinking without judgement, then collaboratively develop strategies to shift unhelpful beliefs.

When students develop metacognitive awareness, they create the perfect conditions for growth mindset to flourish. Rather than simply telling themselves "I can improve," metacognitive students understand exactly how and why improvement happens, making their belief in growth concrete rather than wishful thinking.

Consider what happens when a Year 8 student struggles with algebraic equations. Without metacognition, a growth mindset message of "keep trying" often leads to repeated failure using the same ineffective approach. However, when that same student learns to monitor their thinking process, they might notice: "I keep making errors when I move terms across the equals sign." This awareness turns effort into focused practise on specific skills.

Research from the Education Endowment Foundation demonstrates that students who regularly reflect on their learning strategies show greater resilience when facing setbacks. They view mistakes as diagnostic tools rather than evidence of inability. For instance, teaching students to complete a simple "strategy log" after each maths problem helps them identify which approaches work best for different question types. Over time, this builds genuine confidence based on evidence, not empty encouragement.

In practise, you can strengthen this connection by modelling your own metacognitive processes whilst demonstrating growth mindset. When solving a problem on the board, narrate your thinking: "This method isn't working, so I'll try factorising instead." Show students that monitoring and adjusting strategies is what good learners do, not a sign of weakness. This approach helps students internalise both the belief that abilities can develop and the practical tools to make that development happen.

Teaching growth mindset without metacognitive strategies leaves students enthusiastic but directionless. They might believe they can improve, yet lack the tools to analyse why they're struggling or how to adjust their approach. Picture a Year 8 student who embraces the "power of yet" philosophy but repeatedly uses the same ineffective revision method, believing that mere persistence will eventually work. Without metacognitive awareness, their efforts become exhausting rather than productive.

Conversely, teaching metacognition without growth mindset creates strategically aware students who give up at the first hurdle. These pupils can identify when a learning strategy isn't working and might even know alternative approaches, but their fixed beliefs about ability prevent them from trying. A Year 10 student might recognise that mind mapping helps them understand difficult topics better than linear notes. Yet they still conclude "I'm just not a science person" when faced with challenging chemistry concepts.

Research by Dweck and colleagues (2014) found that growth mindset interventions showed minimal impact when students lacked concrete strategies for improvement. Similarly, Zimmerman's work on self-Regulated learning demonstrates that metacognitive skills remain underutilised when students believe their abilities are fixed. The magic happens when both work together: growth mindset provides the motivation to persist, whilst metacognition offers the roadmap for improvement.

In practise, this means explicitly linking belief to strategy. When teaching fraction division, don't just encourage students to "keep trying"; show them how to monitor their understanding step-by-step, identify confusion points, and select appropriate fix-up strategies. This combination transforms vague encouragement into actionable learning paths that students can follow independently.

Most teachers notice initial changes in student language and behaviour within 2-3 weeks of consistent implementation. However, deeper shifts in learning habits and genuine confidence typically develop over a full term or academic year. The key is maintaining daily practices rather than expecting immediate transformation.

The Dunning-Kruger effect (Kruger and Dunning, 1999) reveals that novice learners consistently overestimate their understanding, while expert learners underestimate theirs. This miscalibration makes explicit metacognitive training essential for accurate self-assessment.

Try asking 'What strategy are you using right now?' and 'How do you know if it's working?' during independent work time. Before tackling problems, ask 'What do you already know about this?' and after completion, 'What would you do differently next time?' These questions become automatic with practise.

Replace generic praise like 'well done' with specific feedback about process and strategy. Say 'I noticed you tried three different approaches when you got stuck' or 'Your revision strategy of testing yourself really paid off here.' This highlights the connection between specific actions and outcomes.

Start with very brief, structured reflections using sentence starters or tick-box formats rather than open-ended questions. Make reflection feel purposeful by showing students how their insights lead to better performance. Gradually increase reflection time as students see the value in the process.

Begin with small, achievable tasks where students can experience quick wins using metacognitive approaches. Focus on documenting evidence of improvement through learning journals or progress tracking. Once students see concrete proof that strategies work, their beliefs about their abilities often begin to shift naturally.

Analysis of a STEM Based Flipped Classroom Learning Model for Enhancing Metacognition and Student Learning Outcomes in Buffer Solution Topic View study ↗

Santi Puji Lestari et al. (2025)

Researchers tested a STEM-based flipped classroom approach to teach complex chemistry concepts like buffer solutions, finding that this model significantly improved both student achievement and metacognitive skills. The flipped format allowed students to engage with content at their own pace while developing better awareness of their learning processes. This approach offers science teachers a practical way to tackle abstract concepts while simultaneously building students' ability to monitor and regulate their own understanding.

GAMIFICATION AS A PEDAGOGICAL STRATEGY: ENHANCING STUDENT PERFORMANCE, MINDSET, AND METACOGNITION View study ↗

Dr.M.ILAYA Kanmani Nanmozhi & Dr.S.GUNASEKARAN (2025)

This large-scale study with 440 university students demonstrated that incorporating game elements into learning significantly improved academic performance, built growth mindset, and enhanced metacognitive abilities. Students in gamified learning environments showed greater engagement and developed better self-awareness about their learning strategies. Teachers can apply these findings by integrating game mechanics like points, challenges, and progress tracking to create more motivating learning experiences that also build students' Thinking skills.

A values-aligned intervention fosters growth mindset-supportive teaching and reduces inequality in educational outcomes View study ↗

31 citations

Cameron A. Hecht et al. (2023)

This groundbreaking study showed that when high school teachers participated in a values-based intervention focused on growth mindset principles, they adopted more supportive classroom practices that particularly benefited students from disadvantaged backgrounds. The intervention successfully reduced achievement gaps by helping teachers demonstrate genuine belief in all students' capacity to learn and improve. This research provides concrete evidence that growth mindset training for teachers can be a effective method for promoting educational equity.

Video games and metacognition in the classroom for the development of 21st century skills: a systematic review View study ↗

6 citations

Mirian Checa-Romero & José Miguel Giménez-Lozano (2025)

This Thorough review analysed how commercial video games used in educational settings can effectively develop students' metacognitive skills and 21st century competencies. The research found that strategic, complex games naturally promote self-reflection, planning, and monitoring of learning processes. Teachers can use this finding by thoughtfully incorporating appropriate commercial games into their curriculum as tools for building students' metacognitive awareness while engaging them in meaningful learning experiences.

Generate an 8-week metacognition roadmap tailored to your key stage, subject, and current practice level.

These peer-reviewed studies provide the research foundation for the strategies discussed in this article:

Integrating cognition, self-regulation, motivation, and metacognition: a framework of post-pandemic flipped classroom design View study ↗

4 citations

Yan Shen et al. (2025)

This research provides teachers with a thorough framework for designing effective flipped classrooms that combine thinking skills, self-regulation, motivation, and metacognition in the post-COVID era. The study addresses the gap between flipped classroom popularity and actual implementation guidance, offering educators a research-backed blueprint for creating meaningful blended learning experiences. This framework helps teachers move beyond simply flipping content to creating truly significant learning environments that develop students' ability to think about their own thinking.

A Framework of College Student Buy-in to Evidence-Based Teaching Practices in STEM: The Roles of Trust and Growth Mindset View study ↗

20 citations

C. Wang et al. (2021)

This study reveals that students' trust in their teachers and their growth mindset significantly influence how willing they are to engage with research-Proven teaching methods in science and math classes. The when students trust their instructors and believe they can improve their abilities, they're more likely to embrace active learning strategies and ultimately perform better academically. For STEM educators, this highlights the important importance of building strong relationships with students and explicitly encouraging growth mindset beliefs to make evidence-based teaching practices truly effective.

Improving self‐regulated learning: A mixed‐methods study on GAI's impact on undergraduate task strategies and metacognition View study ↗

6 citations

Ping Wang et al. (2025)

This eight-week study with 40 undergraduate students found that using AI chatbot tools can improve students' ability to regulate their own learning and become more aware of their thinking processes, particularly in writing tasks. The when students interact with generative AI tools strategically, they develop more diverse learning approaches and stronger metacognitive skills. This finding offers teachers practical insights into how AI can be used not just as a content generator, but as a tool to help students become more independent and reflective learners.

Implicit theories of self-regulated learning: Interplay with students' achievement goals, learning strategies, and metacognition. View study ↗

56 citations

S. Hertel & Yves Karlen (2020)

This research explores how students' beliefs about whether learning skills can be improved affects their motivation, study strategies, and self-awareness as learners. The study found that students who believe learning strategies are malleable and important are more likely to set mastery goals, use effective study techniques, and monitor their own thinking processes. Teachers can use these insights to explicitly teach students that learning skills are developable, which can transform how students approach challenges and setbacks in their academic work.

Self-regulation in learning: The role of language and formative assessment View study ↗

2 citations

Siti Zulaiha (2019)

This study examines how language instruction and ongoing assessment can help students take greater control of their own learning process, particularly in English language teaching contexts. The research highlights the challenge many teachers face in shifting from content-focused instruction to helping students develop independent learning strategies. The findings suggest that combining explicit language instruction with Formative assessment practices can create more self-directed learners who actively monitor and adjust their own progress.

Shifting the mindset culture to address global educational disparities View study ↗

23 citations

Cameron A. Hecht et al. (2023)

This research argues that focusing only on changing individual students' mindsets isn't enough, we also need to transform the entire classroom and school culture around learning beliefs. The study shows that when schools create environments where growth mindset thinking is embedded in policies, practices, and everyday interactions, students from disadvantaged backgrounds benefit most. For teachers, this means thinking beyond individual student interventions to consider how grading practices, classroom discussions, and school-wide messages either support or undermine growth mindset development.

Optimizing self‐regulated learning: A mixed‐methods study on GAI's impact on undergraduate task strategies and metacognition View study ↗

6 citations

Ping Wang et al. (2025)

This current study explored how AI chatbot tools can help college students become better self-directed learners, particularly in writing tasks. Over eight weeks, students who used the AI tool showed improved ability to plan their learning, monitor their progress, and choose more diverse strategies for tackling assignments. These findings suggest that when thoughtfully integrated, AI tools can actually improve rather than replace critical thinking skills, offering teachers new ways to support students' metacognitive development.

The Role of Effective Feedback in Enhancing Student Academic Achievement through Virtual Formative Assessment: A thorough Study View study ↗

Muhammad Usman Zahid & Mahendran AlManiam (2025)

This large-scale study with 365 high school students demonstrates that the quality of feedback, not just the quantity, significantly impacts student achievement in digital learning environments. Students performed better when they received feedback that was easy to understand, practically useful, timely, and motivating rather than discouraging. For teachers navigating online and hybrid learning, this research provides concrete guidance on crafting digital feedback that truly moves student learning forwards.

Implicit theories of self-regulated learning: Interplay with students' achievement goals, learning strategies, and metacognition. View study ↗

56 citations

S. Hertel & Yves Karlen (2020)

This study reveals that students' beliefs about whether learning skills can be improved are just as important as their beliefs about intelligence, and these beliefs directly influence how they approach studying and self-reflection. Students who believed that learning strategies and self-regulation skills could be developed were more likely to set meaningful goals, try new study techniques, and monitor their own learning progress. This research gives teachers insight into how addressing students' beliefs about learning itself can improve their academic strategies and metacognitive awareness.

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/growth-mindset-metacognition-teachers-guide#article","headline":"Growth Mindset and Metacognition: A Teacher's Guide","description":"Explore how growth mindset and metacognition enhance learning. Implement practical strategies and activities to foster these approaches in your classroom.","datePublished":"2026-01-20T09:14:52.247Z","dateModified":"2026-02-05T22:37:15.163Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/growth-mindset-metacognition-teachers-guide"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/696f478ca7df1beb0427cfdd_696f46dfc28e5a4bcf829293_growth-mindset-and-metacogniti-comparison-1768900314596.webp","wordCount":5785},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/growth-mindset-metacognition-teachers-guide#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"Growth Mindset and Metacognition: A Teacher's Guide","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/growth-mindset-metacognition-teachers-guide"}]},{"@type":"FAQPage","mainEntity":[{"@type":"Question","name":"How long does it take to see results when implementing growth mindset and metacognitive strategies?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Most teachers notice initial changes in student language and behaviour within 2-3 weeks of consistent implementation. However, deeper shifts in learning habits and genuine confidence typically develop over a full term or academic year. The key is maintaining daily practices rather than expecting immediate transformation."}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What are some quick metacognitive questioning techniques teachers can use during lessons?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Try asking 'What strategy are you using right now?' and 'How do you know if it's working?' during independent work time. Before tackling problems, ask 'What do you already know about this?' and after completion, 'What would you do differently next time?' These questions become automatic with practise."}},{"@type":"Question","name":"How can teachers avoid giving empty praise whilst still encouraging a growth mindset?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Replace generic praise like 'well done' with specific feedback about process and strategy. Say 'I noticed you tried three different approaches when you got stuck' or 'Your revision strategy of testing yourself really paid off here.' This highlights the connection between specific actions and outcomes."}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What should teachers do when students resist metacognitive reflection activities?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Start with very brief, structured reflections using sentence starters or tick-box formats rather than open-ended questions. Make reflection feel purposeful by showing students how their insights lead to better performance. Gradually increase reflection time as students see the value in the process."}},{"@type":"Question","name":"How can teachers help students with fixed mindsets who struggle to engage with metacognitive strategies?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Begin with small, achievable tasks where students can experience quick wins using metacognitive approaches. Focus on documenting evidence of improvement through learning journals or progress tracking. Once students see concrete proof that strategies work, their beliefs about their abilities often begin to shift naturally."}},{"@type":"Question","name":"Essential Growth Mindset Research Studies","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"These peer-reviewed studies provide the research foundation for the strategies discussed in this article:"}}]}]}