How Higher-Order Questioning Drives Critical Thinking

Explore effective higher-order questioning strategies to foster critical thinking, curiosity, and deeper learning in your classroom.

Explore effective higher-order questioning strategies to foster critical thinking, curiosity, and deeper learning in your classroom.

Higher-order questioning transforms how students think by prompting them to analyse, evaluate, and create rather than simply recall facts. These strategic questioning techniques move learners beyond surface-level understanding to develop genuine critical thinking skills that serve them throughout life. When teachers master the art of asking "why," "how," and "what if" questions, they unlock their students' ability to think independently and solve complex problems. The secret lies in knowing which questions to ask and exactly when to ask them.

Higher-order questioning not only enhances learning but also creates an environment where students are encouraged to explore ideas, challenge assumptions, and drive their own understanding through self-regulated learning and metacognitive strategies (especially for mathematics teachers). By incorporating activities, thinking routines, and frameworks that support this inquiry-based approach, educators can cultivate critical thinkers who are equipped for the complexities of modern life.

In this article, we will explore the definition and strategies of higher-order questioning, examine various teaching methods that promote critical thinking, and connect educational theories like cognitive development that provide a foundation for these practices. Join us as we explore into how these techniques enable learners to thrive in their academic and personal pursuits.

When implementing higher-order questioning in the classroom, educators can use open-ended, provocative, and divergent questions. These questions prompt analysis, synthesis, and evaluation, leading to deeper understanding and engagement. Incorporating such questions into lesson plans andProject-Based Learning initiatives creates an environment where learners use prior knowledge and real-life experiences to develop insights and assumptions.

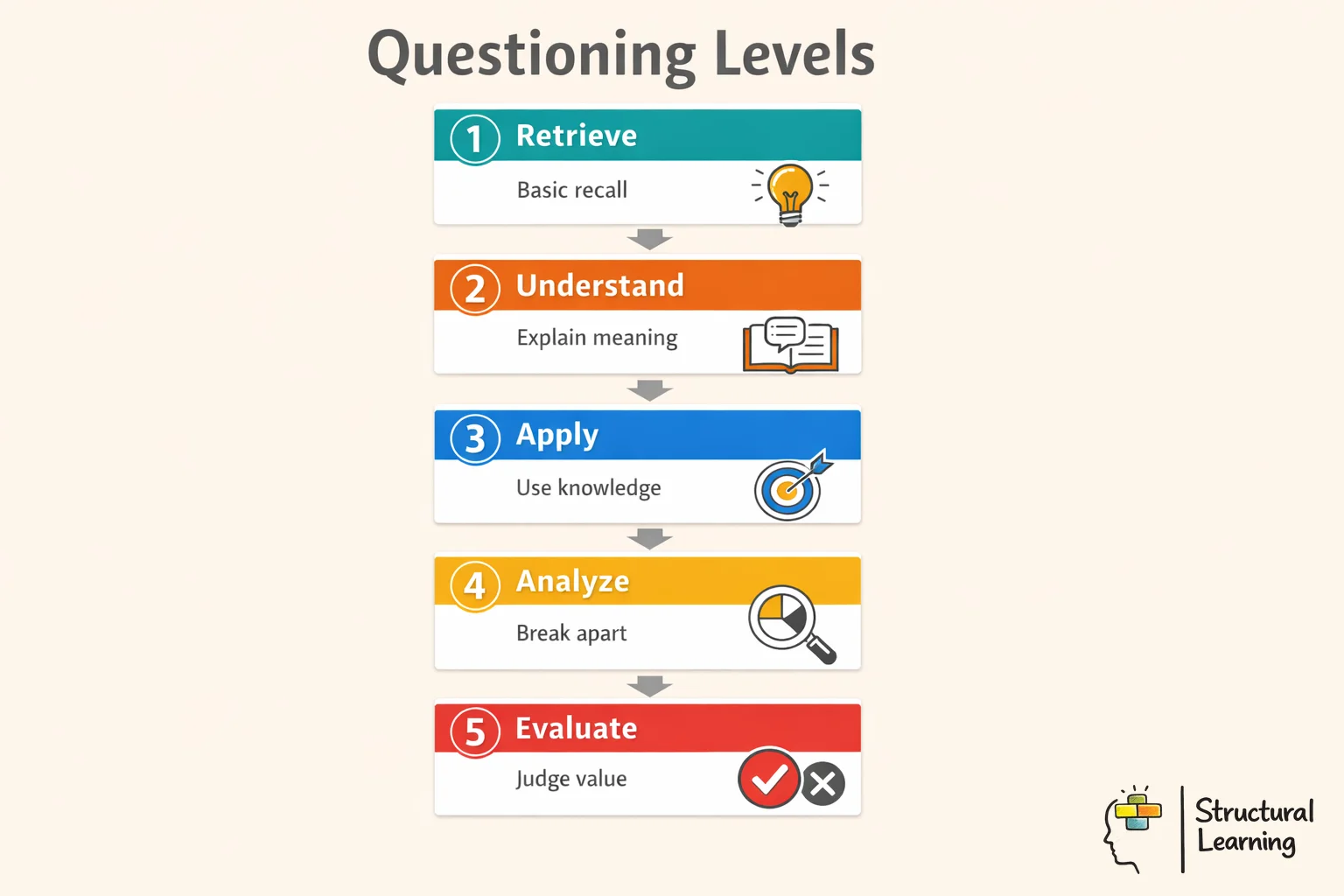

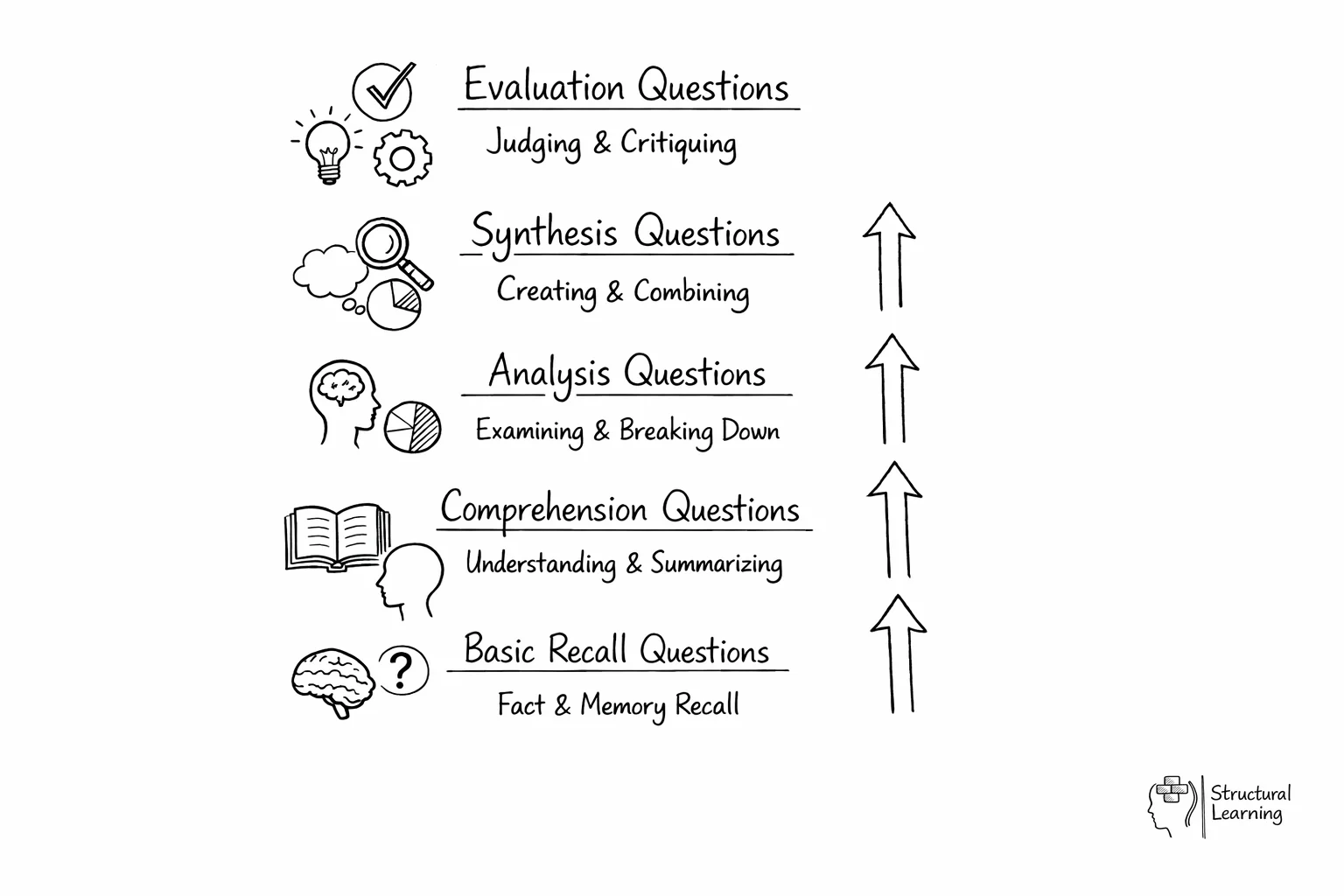

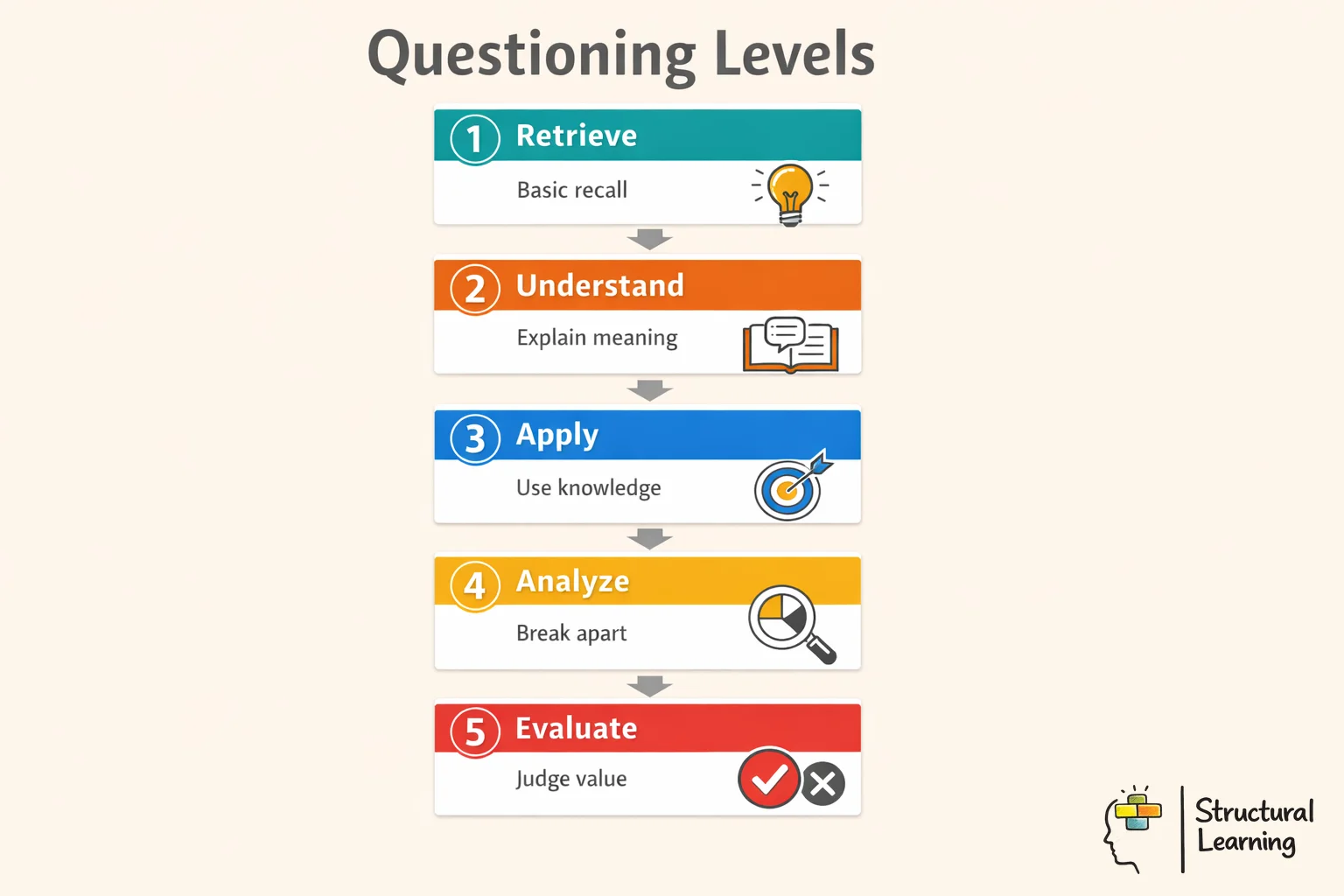

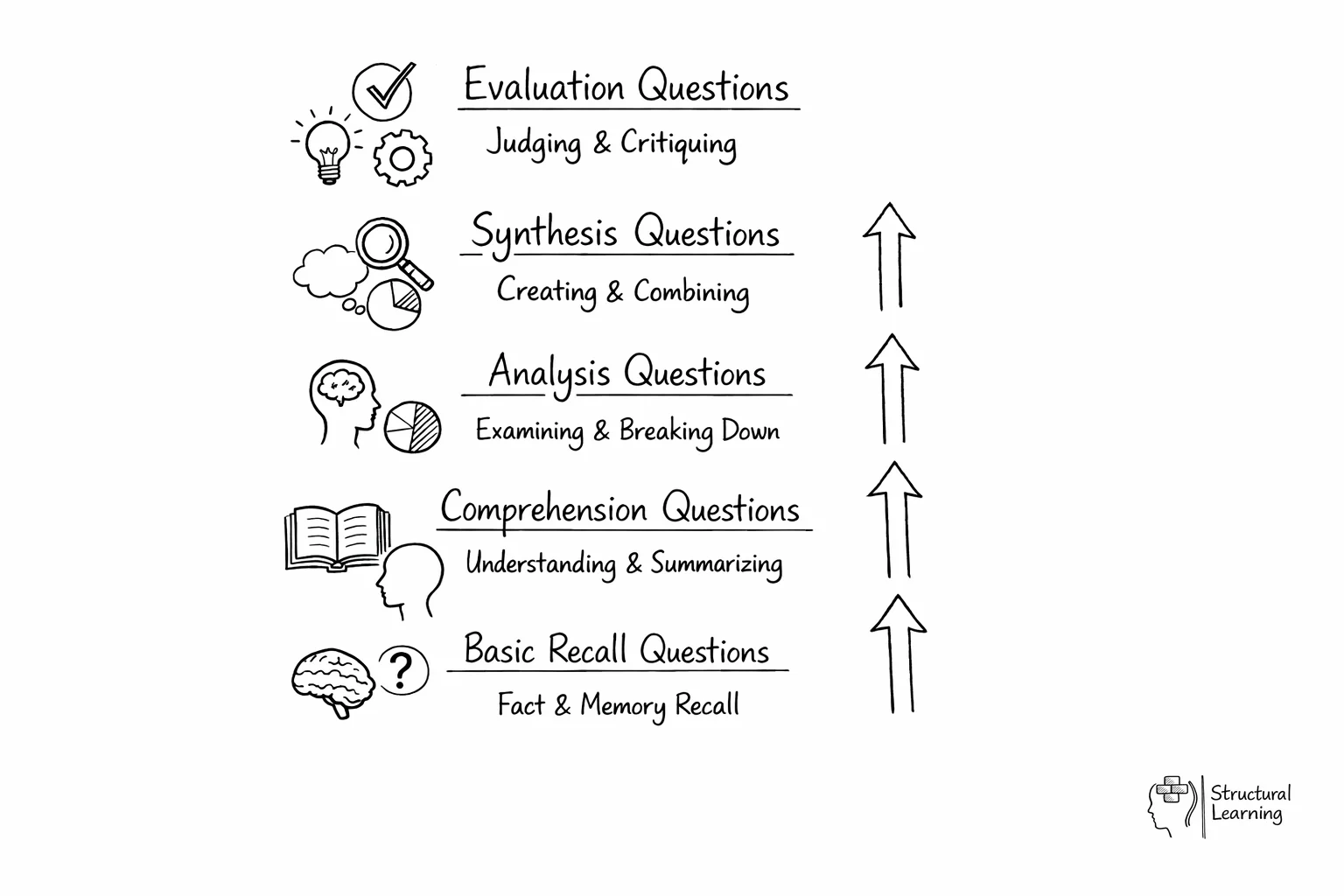

Teachers develop higher-order thinking skills by using Bloom's Taxonomy to scaffold questions from basic comprehension to analysis and evaluation. Effective strategies include think-pair-share activities, Socratic seminars, and problem-based learning scenarios that require students to apply knowledge in new contexts. Regular practise with open-ended questions and providing wait time for student responses are essential for building these skills.

To enhance higher-order thinking skills, teachers should explicitly teach strategies, helping students recognise their strengths and challenges. Identifying key concepts within content areas is crucial, and teachers should clearly inform students when these concepts are being introduced. Utilizing formative assessment methods like project-based tasks allows students to synthesize knowledge and create new products, encouraging deeper understanding.

Employing cognitive and metacognitive strategies provides continuous growth opportunities for all students, especially high-ability learners, by engaging them in challenging tasks. Using thinking skill taxonomies such as Bloom's Revised Taxonomy and Webb's Depth of Knowledge can aid in effectively planning activities aimed at improving higher-level thinking skills.

Classroom discussions serve as a platform for evaluating skills like analysis and synthesis while promoting communication and critical thinking. Concept maps allow students to organise and connect ideas, demonstrating material comprehension. Peer review encourages students to critically assess and provide feedback on each other's work, enhancing subject matter understanding.

Learning journals act as a metacognitive tool, enabling students to reflect on their experiences and identify areas for improvement. Teachers can use strategies such as posing provocative questions, presenting problems with multiple solutions, and conducting Socratic dialogues to stimulate in-depth discussion and analysis.

Inquiry-based learning fuels curiosity and creates critical thinking via effective questioning. It requires establishing a classroom culture that supports continuous inquiry and exploration. Teachers can enhance this learning by posing provocative questions, using analogies, and presenting problems with multiple outcomes, sparking student discussion and exploration.

Models like Bloom's Revised Taxonomy and Webb's Depth of Knowledge assist in planning activities targeting higher-order thinking, focusing on the highest cognitive levels for deep understanding. Authentic assessments challenge students with real-world scenarios, prompting them to apply their knowledge and develop problem-solving skills, ultimately boosting critical thinking capabilities through scaffolding support.

Teachers can use frameworks like Bloom's Revised Taxonomy or Webb's Depth of Knowledge to systematically generate higher-order questions by starting with action verbs like analyse, evaluate, and create. The framework provides question stems such as 'What evidence supports..' or 'How would you design..' that automatically prompt deeper thinking. Planning questions in advance using these frameworks ensures consistent cognitive challenge across lessons while managing cognitive load.

| Level | Cognitive Process | Question Stems | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Remember | Recall facts | What, who, when, where | What year did...? |

| Understand | Explain meaning | Explain, describe, summarise | Why does this happen? |

| Apply | Use in new situations | How would you use...? | Solve this problem... |

| Analyse | Break into parts | Compare, contrast, examine | What evidence supports...? |

| Evaluate | Make judgements | Justify, defend, critique | Which solution is best? |

| Create | Generate new ideas | Design, compose, develop | How might you improve...? |

Higher-order thinking questions allow learners to analyse, evaluate, and synthesize information, essential components of constructivist learning approaches that build on students' existing knowledge and understanding through zone of proximal development principles.

The SOLO taxonomy (Structure of the Observed Learning Outcome) provides another powerful framework for crafting questions that assess different levels of understanding. Teachers can design questions targeting unistructural responses (one relevant aspect), multistructural responses (several relevant aspects), relational responses (integration of aspects), and extended abstract responses (generalisation to new domains). For example, when studying ecosystems, a relational question might ask: "How do the feeding relationships between predators and prey influence population cycles in this woodland habitat?"

Practical implementation of these frameworks requires systematic planning and practice. Begin by mapping your learning objectives to specific question types within your chosen framework, then create question banks organised by cognitive level. During lessons, deliberately sequence questions to scaffold student thinking from lower to higher-order responses. Consider using question stems such as "What evidence supports.." for analytical thinking or "How might this apply if.." for evaluative reasoning. Regular reflection on student responses helps refine your questioning strategies and identifies which frameworks work best for different topics and learner needs.

Effective implementation of higher-order questioning begins with strategic planning and gradual integration into existing classroom routines. Teachers should start by identifying key moments within lessons where analytical or evaluative questions can naturally replace lower-order recall questions. Research by Mary Budd Rowe demonstrates that increasing wait time to three to five seconds after posing complex questions significantly improves the quality of student responses, allowing learners time to process and formulate thoughtful answers.

The most successful educators employ a scaffolding approach, beginning lessons with foundational questions before progressing to more complex analytical challenges. This technique, supported by Vygotsky's zone of proximal development theory, ensures students build confidence whilst developing critical thinking skills. Teachers can create question banks organised by Bloom's taxonomy levels, focusing particularly on analysis, synthesis, and evaluation questions that require students to make connections, draw conclusions, and justify their reasoning.

Practical classroom strategies include implementing think-pair-share activities following higher-order questions, using question stems such as "What evidence supports.." or "How might this change if..", and encouraging students to generate their own complex questions. Regular reflection on questioning patterns through lesson recordings or peer observation helps educators identify opportunities for improvement and ensures consistent implementation across all subject areas.

Effective assessment of higher-order questioning requires moving beyond traditional metrics to examine both the quality of student responses and the depth of thinking processes. Teachers should focus on evaluating whether students demonstrate analytical reasoning, synthesise information from multiple sources, and construct well-supported arguments rather than simply providing correct answers. Bloom's taxonomy provides a useful framework for categorising response levels, helping educators distinguish between surface-level recall and genuine critical thinking.

Formative assessment strategies prove particularly valuable in gauging questioning effectiveness. Consider implementing think-aloud protocols where students verbalise their reasoning processes, revealing the cognitive pathways triggered by your questions. Additionally, peer discussion observations can illuminate whether higher-order questions generate meaningful dialogue and collaborative problem-solving. Costa and Kallick's work on intellectual dispositions suggests monitoring students' persistence with challenging questions and their willingness to consider alternative perspectives as key indicators of developing critical thinking skills.

Practical classroom assessment might include creating simple rubrics that evaluate response sophistication, tracking student questioning patterns over time, and maintaining reflection journals where learners document their thinking processes. Remember that the goal is not immediate mastery but progressive development of questioning habits that transfer across subjects and contexts.

Effective higher-order questioning must be carefully tailored to the unique demands and thinking patterns of each subject area. In mathematics, questions should progress from procedural recall ("What is the formula?") to conceptual understanding ("Why does this method work?") and finally to analytical application ("How might you solve this differently?"). Science educators benefit from inquiry-based questioning that mirrors scientific methodology, asking students to hypothesise, predict outcomes, and evaluate evidence. Meanwhile, humanities subjects thrive on questions that explore multiple perspectives, causal relationships, and the synthesis of complex ideas.

The cognitive architecture of different disciplines requires distinct questioning approaches. Bloom's taxonomy provides a useful framework, but successful teachers adapt its levels to subject-specific contexts. Literature teachers might ask "How does the author's use of symbolism reflect broader social tensions?", whilst history educators could probe "What alternative outcomes might have emerged if different decisions were made?". These questions demand discipline-specific analytical skills whilst maintaining the rigorous thinking processes that characterise higher-order questioning.

Practical implementation begins with examining your curriculum's learning objectives and identifying opportunities to replace lower-order questions with more challenging alternatives. Create subject-specific question stems that align with your discipline's thinking patterns, and gradually introduce these into daily practice. Students need time to develop the cognitive skills required for sophisticated questioning, so begin with structured support and progressively increase independence.

Despite their best intentions, educators frequently stumble into questioning patterns that inadvertently limit critical thinking development. The most pervasive mistake involves asking rapid-fire questions without providing adequate wait time, a practice that John Rowe's research demonstrates significantly reduces the quality of student responses. When teachers rush from question to answer, they signal that quick recall matters more than thoughtful analysis, effectively training students to prioritise speed over depth in their thinking processes.

Another common pitfall occurs when educators ask genuinely higher-order questions but then accept superficial answers without follow-up probing. This behaviour sends mixed messages about expectations and wastes the potential of well-crafted questions. The solution lies in developing a repertoire of follow-up prompts such as "What evidence supports that conclusion?" or "How does this connect to what we discussed yesterday?" These extensions push students beyond their initial responses into genuine critical analysis.

Successfully implementing higher-order questioning requires deliberate practice and self-reflection. Record yourself teaching, noting the types of questions you ask and how long you wait for responses. Gradually increase your wait time to at least five seconds, and prepare follow-up questions in advance to avoid falling back on acceptance of surface-level answers when students provide unexpected responses.

Higher-order questioning transforms how students think by prompting them to analyse, evaluate, and create rather than simply recall facts. These strategic questioning techniques move learners beyond surface-level understanding to develop genuine critical thinking skills that serve them throughout life. When teachers master the art of asking "why," "how," and "what if" questions, they unlock their students' ability to think independently and solve complex problems. The secret lies in knowing which questions to ask and exactly when to ask them.

Higher-order questioning not only enhances learning but also creates an environment where students are encouraged to explore ideas, challenge assumptions, and drive their own understanding through self-regulated learning and metacognitive strategies (especially for mathematics teachers). By incorporating activities, thinking routines, and frameworks that support this inquiry-based approach, educators can cultivate critical thinkers who are equipped for the complexities of modern life.

In this article, we will explore the definition and strategies of higher-order questioning, examine various teaching methods that promote critical thinking, and connect educational theories like cognitive development that provide a foundation for these practices. Join us as we explore into how these techniques enable learners to thrive in their academic and personal pursuits.

When implementing higher-order questioning in the classroom, educators can use open-ended, provocative, and divergent questions. These questions prompt analysis, synthesis, and evaluation, leading to deeper understanding and engagement. Incorporating such questions into lesson plans andProject-Based Learning initiatives creates an environment where learners use prior knowledge and real-life experiences to develop insights and assumptions.

Teachers develop higher-order thinking skills by using Bloom's Taxonomy to scaffold questions from basic comprehension to analysis and evaluation. Effective strategies include think-pair-share activities, Socratic seminars, and problem-based learning scenarios that require students to apply knowledge in new contexts. Regular practise with open-ended questions and providing wait time for student responses are essential for building these skills.

To enhance higher-order thinking skills, teachers should explicitly teach strategies, helping students recognise their strengths and challenges. Identifying key concepts within content areas is crucial, and teachers should clearly inform students when these concepts are being introduced. Utilizing formative assessment methods like project-based tasks allows students to synthesize knowledge and create new products, encouraging deeper understanding.

Employing cognitive and metacognitive strategies provides continuous growth opportunities for all students, especially high-ability learners, by engaging them in challenging tasks. Using thinking skill taxonomies such as Bloom's Revised Taxonomy and Webb's Depth of Knowledge can aid in effectively planning activities aimed at improving higher-level thinking skills.

Classroom discussions serve as a platform for evaluating skills like analysis and synthesis while promoting communication and critical thinking. Concept maps allow students to organise and connect ideas, demonstrating material comprehension. Peer review encourages students to critically assess and provide feedback on each other's work, enhancing subject matter understanding.

Learning journals act as a metacognitive tool, enabling students to reflect on their experiences and identify areas for improvement. Teachers can use strategies such as posing provocative questions, presenting problems with multiple solutions, and conducting Socratic dialogues to stimulate in-depth discussion and analysis.

Inquiry-based learning fuels curiosity and creates critical thinking via effective questioning. It requires establishing a classroom culture that supports continuous inquiry and exploration. Teachers can enhance this learning by posing provocative questions, using analogies, and presenting problems with multiple outcomes, sparking student discussion and exploration.

Models like Bloom's Revised Taxonomy and Webb's Depth of Knowledge assist in planning activities targeting higher-order thinking, focusing on the highest cognitive levels for deep understanding. Authentic assessments challenge students with real-world scenarios, prompting them to apply their knowledge and develop problem-solving skills, ultimately boosting critical thinking capabilities through scaffolding support.

Teachers can use frameworks like Bloom's Revised Taxonomy or Webb's Depth of Knowledge to systematically generate higher-order questions by starting with action verbs like analyse, evaluate, and create. The framework provides question stems such as 'What evidence supports..' or 'How would you design..' that automatically prompt deeper thinking. Planning questions in advance using these frameworks ensures consistent cognitive challenge across lessons while managing cognitive load.

| Level | Cognitive Process | Question Stems | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Remember | Recall facts | What, who, when, where | What year did...? |

| Understand | Explain meaning | Explain, describe, summarise | Why does this happen? |

| Apply | Use in new situations | How would you use...? | Solve this problem... |

| Analyse | Break into parts | Compare, contrast, examine | What evidence supports...? |

| Evaluate | Make judgements | Justify, defend, critique | Which solution is best? |

| Create | Generate new ideas | Design, compose, develop | How might you improve...? |

Higher-order thinking questions allow learners to analyse, evaluate, and synthesize information, essential components of constructivist learning approaches that build on students' existing knowledge and understanding through zone of proximal development principles.

The SOLO taxonomy (Structure of the Observed Learning Outcome) provides another powerful framework for crafting questions that assess different levels of understanding. Teachers can design questions targeting unistructural responses (one relevant aspect), multistructural responses (several relevant aspects), relational responses (integration of aspects), and extended abstract responses (generalisation to new domains). For example, when studying ecosystems, a relational question might ask: "How do the feeding relationships between predators and prey influence population cycles in this woodland habitat?"

Practical implementation of these frameworks requires systematic planning and practice. Begin by mapping your learning objectives to specific question types within your chosen framework, then create question banks organised by cognitive level. During lessons, deliberately sequence questions to scaffold student thinking from lower to higher-order responses. Consider using question stems such as "What evidence supports.." for analytical thinking or "How might this apply if.." for evaluative reasoning. Regular reflection on student responses helps refine your questioning strategies and identifies which frameworks work best for different topics and learner needs.

Effective implementation of higher-order questioning begins with strategic planning and gradual integration into existing classroom routines. Teachers should start by identifying key moments within lessons where analytical or evaluative questions can naturally replace lower-order recall questions. Research by Mary Budd Rowe demonstrates that increasing wait time to three to five seconds after posing complex questions significantly improves the quality of student responses, allowing learners time to process and formulate thoughtful answers.

The most successful educators employ a scaffolding approach, beginning lessons with foundational questions before progressing to more complex analytical challenges. This technique, supported by Vygotsky's zone of proximal development theory, ensures students build confidence whilst developing critical thinking skills. Teachers can create question banks organised by Bloom's taxonomy levels, focusing particularly on analysis, synthesis, and evaluation questions that require students to make connections, draw conclusions, and justify their reasoning.

Practical classroom strategies include implementing think-pair-share activities following higher-order questions, using question stems such as "What evidence supports.." or "How might this change if..", and encouraging students to generate their own complex questions. Regular reflection on questioning patterns through lesson recordings or peer observation helps educators identify opportunities for improvement and ensures consistent implementation across all subject areas.

Effective assessment of higher-order questioning requires moving beyond traditional metrics to examine both the quality of student responses and the depth of thinking processes. Teachers should focus on evaluating whether students demonstrate analytical reasoning, synthesise information from multiple sources, and construct well-supported arguments rather than simply providing correct answers. Bloom's taxonomy provides a useful framework for categorising response levels, helping educators distinguish between surface-level recall and genuine critical thinking.

Formative assessment strategies prove particularly valuable in gauging questioning effectiveness. Consider implementing think-aloud protocols where students verbalise their reasoning processes, revealing the cognitive pathways triggered by your questions. Additionally, peer discussion observations can illuminate whether higher-order questions generate meaningful dialogue and collaborative problem-solving. Costa and Kallick's work on intellectual dispositions suggests monitoring students' persistence with challenging questions and their willingness to consider alternative perspectives as key indicators of developing critical thinking skills.

Practical classroom assessment might include creating simple rubrics that evaluate response sophistication, tracking student questioning patterns over time, and maintaining reflection journals where learners document their thinking processes. Remember that the goal is not immediate mastery but progressive development of questioning habits that transfer across subjects and contexts.

Effective higher-order questioning must be carefully tailored to the unique demands and thinking patterns of each subject area. In mathematics, questions should progress from procedural recall ("What is the formula?") to conceptual understanding ("Why does this method work?") and finally to analytical application ("How might you solve this differently?"). Science educators benefit from inquiry-based questioning that mirrors scientific methodology, asking students to hypothesise, predict outcomes, and evaluate evidence. Meanwhile, humanities subjects thrive on questions that explore multiple perspectives, causal relationships, and the synthesis of complex ideas.

The cognitive architecture of different disciplines requires distinct questioning approaches. Bloom's taxonomy provides a useful framework, but successful teachers adapt its levels to subject-specific contexts. Literature teachers might ask "How does the author's use of symbolism reflect broader social tensions?", whilst history educators could probe "What alternative outcomes might have emerged if different decisions were made?". These questions demand discipline-specific analytical skills whilst maintaining the rigorous thinking processes that characterise higher-order questioning.

Practical implementation begins with examining your curriculum's learning objectives and identifying opportunities to replace lower-order questions with more challenging alternatives. Create subject-specific question stems that align with your discipline's thinking patterns, and gradually introduce these into daily practice. Students need time to develop the cognitive skills required for sophisticated questioning, so begin with structured support and progressively increase independence.

Despite their best intentions, educators frequently stumble into questioning patterns that inadvertently limit critical thinking development. The most pervasive mistake involves asking rapid-fire questions without providing adequate wait time, a practice that John Rowe's research demonstrates significantly reduces the quality of student responses. When teachers rush from question to answer, they signal that quick recall matters more than thoughtful analysis, effectively training students to prioritise speed over depth in their thinking processes.

Another common pitfall occurs when educators ask genuinely higher-order questions but then accept superficial answers without follow-up probing. This behaviour sends mixed messages about expectations and wastes the potential of well-crafted questions. The solution lies in developing a repertoire of follow-up prompts such as "What evidence supports that conclusion?" or "How does this connect to what we discussed yesterday?" These extensions push students beyond their initial responses into genuine critical analysis.

Successfully implementing higher-order questioning requires deliberate practice and self-reflection. Record yourself teaching, noting the types of questions you ask and how long you wait for responses. Gradually increase your wait time to at least five seconds, and prepare follow-up questions in advance to avoid falling back on acceptance of surface-level answers when students provide unexpected responses.

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/higher-order-questioning#article","headline":"How Higher-Order Questioning Drives Critical Thinking","description":"Explore effective higher-order questioning strategies to foster critical thinking, curiosity, and deeper learning in your classroom.","datePublished":"2024-11-18T12:21:36.334Z","dateModified":"2026-01-26T10:09:32.212Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/higher-order-questioning"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/696f4cca904567845e6c23d9_696f4cc907c28add5b71f518_higher-order-questioning-infographic.webp","wordCount":3290},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/higher-order-questioning#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"How Higher-Order Questioning Drives Critical Thinking","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/higher-order-questioning"}]}]}