Systems Theory in Education: Understanding Complex Learning Environments

Explore systems theory in education. Learn how schools function as complex systems and how understanding interconnections improves teaching and leadership.

Systems theory provides a powerful framework for understanding how schools and classrooms function as interconnected wholes rather than isolated parts. Originating in biology and later applied across disciplines by education theoristslike Thorndike and others, systems thinking helps educators see how changes in one area affect the entire system. From understanding why interventions sometimes produce unexpected results to designing more effective school improvement strategies, systems theory offers practical insights for teachers and leaders.

| Examples (This IS the concept) | Non-Examples (This is NOT) |

|---|---|

| A transformative student being moved to the front row causes other students to shift their behaviour through observational learning, creating new classroom dynamics and unexpected social groupings | A teacher dealing with one student's behaviour problem in isolation without considering how it affects the whole class |

| A school's new homework policy leads to increased parent involvement, which changes teacher-parent communication patterns and ultimately affects student motivation across multiple subjects | Implementing a single intervention strategy that only focuses on improving test scores without considering broader impacts |

| Positive feedback loops in a classroom where high-achieving students receive more attention, leading to increased performance gaps between student groups | Looking at individual student performance data without examining peer relationships, classroom environment, or family factors |

| Understanding how a change in school lunch schedule affects afternoon classroom behaviour, student energy levels, and after-school program attendance | Creating separate, unconnected plans for academics, behaviour management, and social development |

It suggests that complex systems are more than just the sum of their parts, and that examining the relationships between those parts can lead to a better understanding of the whole ( Bertalanffy, 1968).

Complex systems, unlike simple, linear systems, can exhibit emergent properties that cannot be predicted from the behaviour of individual components. Therefore, systems theorists often employ interdisciplinary approaches to study complex systems, drawing on fields such as mathematics, physics, psychology, and sociology. This allows them to analyse patterns of behaviour and feedback-controlled regulation processes (Skyttner, 2005).

Applications of systems theory can be found in diverse fields such as management, ecology, and social science. By adopting a complete approach to understanding systems, researchers can gain insight into individual level behaviours and macro and policy levels of organisations.

In essence, systems theory is an invaluable tool for understanding the complex and dynamic systems that shape our daily lives (Bertalanffy, 1968).

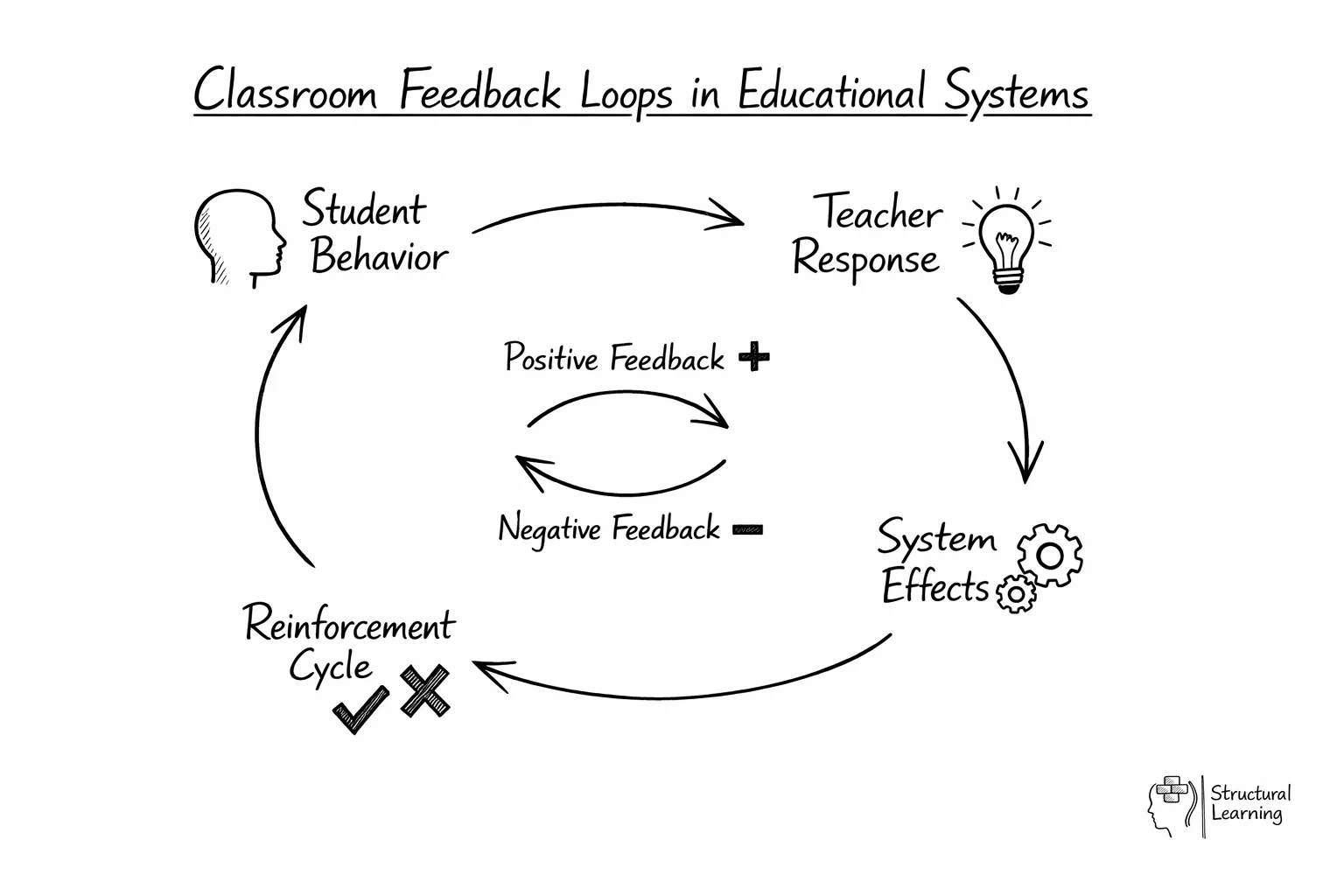

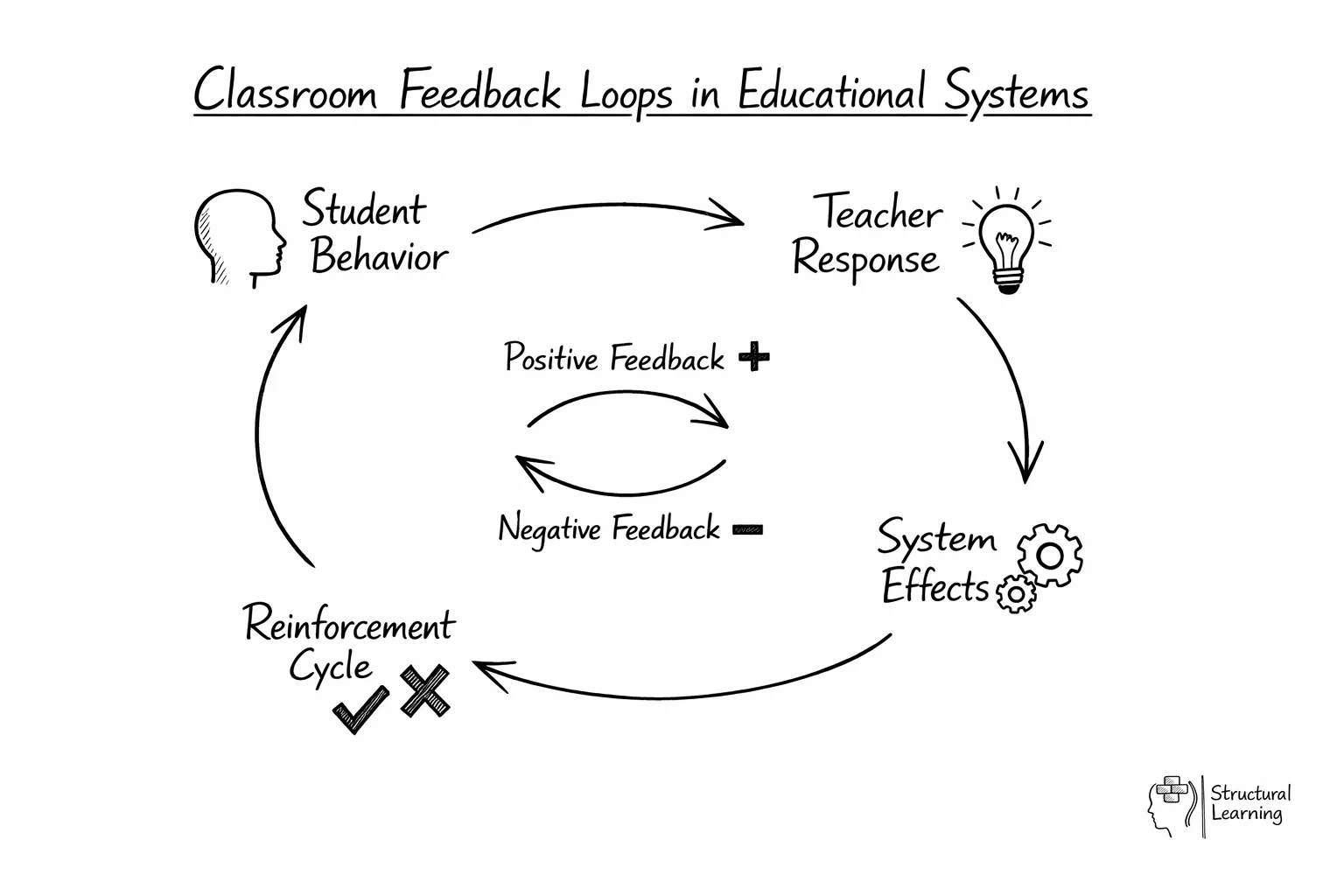

Feedback loops in classrooms create cycles where student behaviours and teacher responses reinforce each other, either positively or negatively. For example, when a teacher consistently rewards participation, students participate more, which leads to more rewards. Understanding these loops helps teachers break negative cycles and strengthen positive ones through strategic feedback interventions.

Feedback loops are a central concept in systems theory, particularly in the study of behavioural dynamics. These loops refer to the cyclical flow of information between components within a system. Positive feedback loops amplify the effects of a particular behaviour, leading to the perpetuation or escalation of patterns of behaviour.

On the other hand, negative feedback loops act as a regulatory mechanism, dampening the effects of behaviour and maintaining system stability. In educational settings, understanding these different types of feedback loops allows teachers to design interventions that either amplify desired behaviours or dampen problematic ones.

Consider how a negative feedback loop might work in practice: when a student exhibits transformative behaviour, the teacher responds with a consequence, which should ideally reduce the transformative behaviour. However, if the consequence inadvertently provides the attention the student seeks, it may create a positive feedback loop instead, reinforcing the unwanted behaviour. This is why systems thinking requires educators to look beyond immediate cause-and-effect relationships and examine the broader patterns that emerge over time.

The key to managing classroom feedback loops lies in recognising that every intervention creates ripple effects throughout the system. Successful teachers learn to anticipate these effects and design their responses to strengthen positive loops whilst interrupting negative ones. This might involve changing the timing of feedback, adjusting the type of attention given to different behaviours, or modifying the classroom environment to support more productive interactions.

Systems theory transforms classroom management from a reactive discipline approach to a proactive design challenge. Rather than addressing individual behavioural incidents in isolation, teachers using systems thinking examine the underlying structures that generate patterns of behaviour. This includes physical environment, social dynamics, academic expectations, and communication patterns that all interact to create the classroom climate.

Effective systems-based classroom management begins with mapping the invisible connections in your classroom. Start by observing how changes in one area affect others: notice how seating arrangements influence peer relationships, how assessment practices affect student motivation, or how your own energy levels impact the entire room's atmosphere. These observations reveal the use points where small changes can create significant positive shifts across the whole system.

One powerful application involves creating positive interdependence amongst students through collaborative learning structures. When students' success becomes connected to their peers' success, the social system naturally reinforces helpful behaviours and discourages transformative ones. This shifts the responsibility for maintaining a positive learning environment from solely the teacher to the entire classroom community.

Another key strategy involves designing feedback systems that provide multiple types of information to students about their progress. Rather than relying solely on grades or verbal feedback, systems-thinking teachers create environments where students receive continuous information about their learning through peer interactions, self-reflection opportunities, and visible progress indicators. This creates self-regulating loops that reduce the need for external management interventions.

Whilst systems theory offers valuable insights for education, it also presents practical challenges for busy teachers and school leaders. The complexity of educational systems can make it difficult to identify which variables are most important to address, and the interconnected nature of systems means that changes often take time to show results. Teachers may feel overwhelmed by the need to consider multiple factors simultaneously when addressing classroom issues.

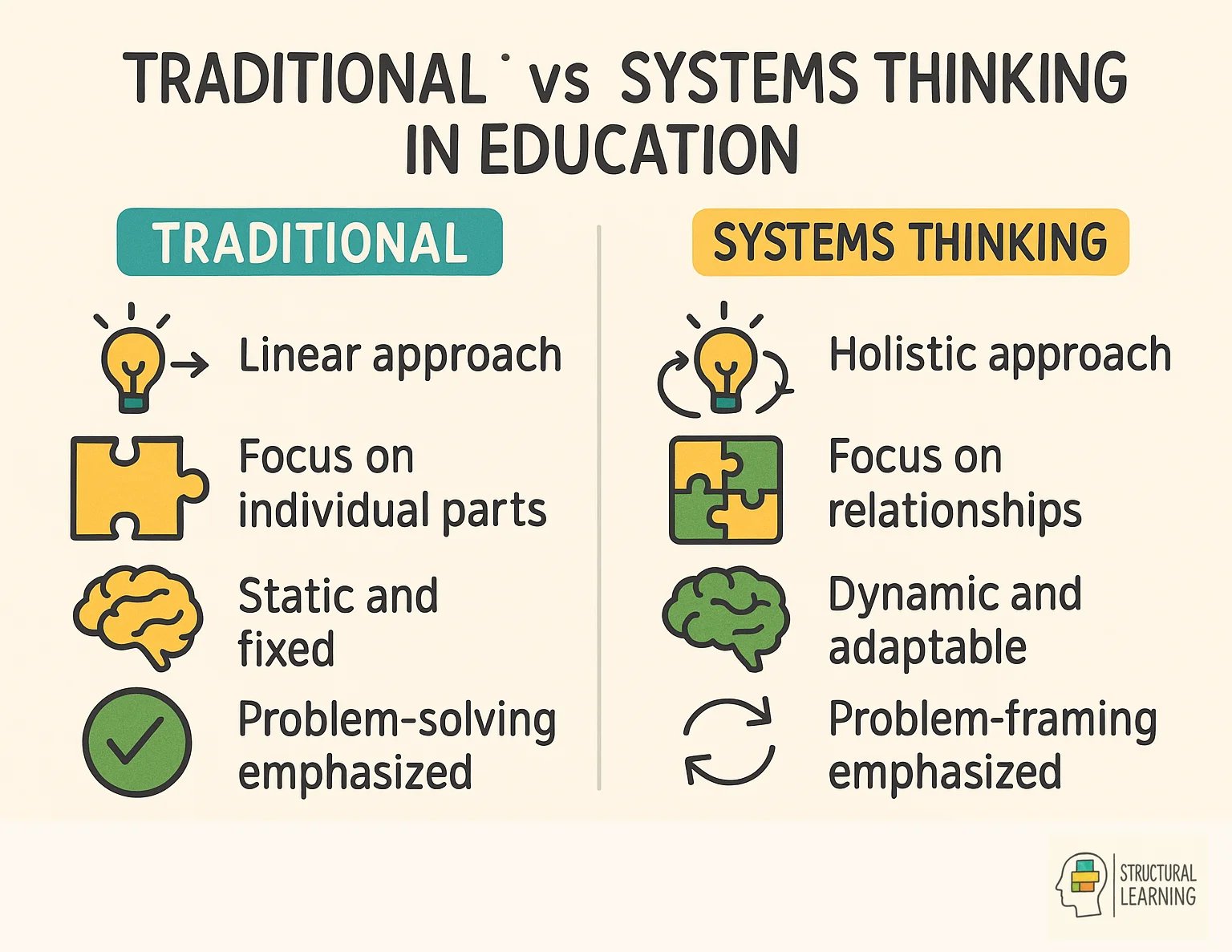

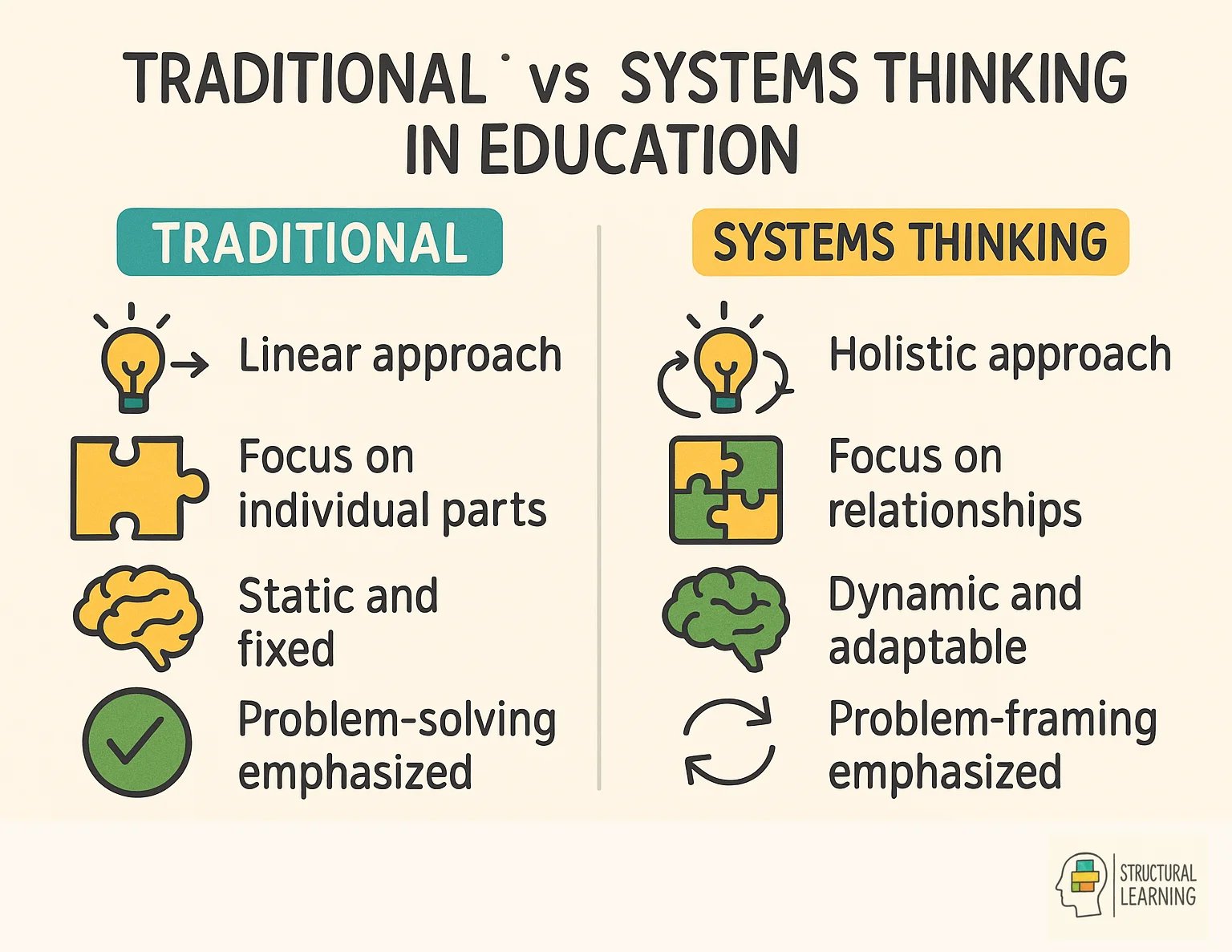

Additionally, systems thinking requires a shift from traditional linear problem-solving approaches that many educators are comfortable with. It demands patience and tolerance for uncertainty, as the effects of interventions may not be immediately apparent or may manifest in unexpected ways. Schools operating under pressure to show rapid improvement may find it challenging to invest in systems-based approaches that require longer timeframes to demonstrate their effectiveness.

Another limitation lies in the difficulty of measuring systemic changes using traditional educational assessment tools. Standardised tests and individual performance metrics may not capture the improvements in classroom climate, peer relationships, or long-term learning habits that systems interventions are designed to create. This can make it challenging to justify systems-based approaches in environments focused on quantifiable outcomes.

Systems theory offers educators a transformative lens for understanding and improving complex learning environments. By recognising schools and classrooms as interconnected systems rather than collections of isolated parts, teachers can design more effective interventions that address root causes rather than symptoms. The power of this approach lies in its ability to reveal hidden connections and use points that traditional linear thinking often misses.

For practicing teachers, adopting systems thinking means becoming more strategic about classroom decisions and more observant about the ripple effects of interventions. It requires patience and willingness to experiment, as systems-based improvements often unfold gradually through multiple feedback loops. However, the long-term benefits include more sustainable behaviour improvements, stronger classroom communities, and learning environments that support all students' development.

As education continues to grapple with increasingly complex challenges, systems theory provides essential tools for creating adaptive, resilient learning environments. By understanding how individual elements interact to create emergent properties at the classroom and school level, educators can move beyond quick fixes to develop comprehensive approaches that address the underlying structures shaping student experience and achievement.

For educators interested in deepening their understanding of systems theory in educational contexts, the following research provides valuable theoretical foundations and practical applications:

Systems theory provides a powerful framework for understanding how schools and classrooms function as interconnected wholes rather than isolated parts. Originating in biology and later applied across disciplines by education theoristslike Thorndike and others, systems thinking helps educators see how changes in one area affect the entire system. From understanding why interventions sometimes produce unexpected results to designing more effective school improvement strategies, systems theory offers practical insights for teachers and leaders.

| Examples (This IS the concept) | Non-Examples (This is NOT) |

|---|---|

| A transformative student being moved to the front row causes other students to shift their behaviour through observational learning, creating new classroom dynamics and unexpected social groupings | A teacher dealing with one student's behaviour problem in isolation without considering how it affects the whole class |

| A school's new homework policy leads to increased parent involvement, which changes teacher-parent communication patterns and ultimately affects student motivation across multiple subjects | Implementing a single intervention strategy that only focuses on improving test scores without considering broader impacts |

| Positive feedback loops in a classroom where high-achieving students receive more attention, leading to increased performance gaps between student groups | Looking at individual student performance data without examining peer relationships, classroom environment, or family factors |

| Understanding how a change in school lunch schedule affects afternoon classroom behaviour, student energy levels, and after-school program attendance | Creating separate, unconnected plans for academics, behaviour management, and social development |

It suggests that complex systems are more than just the sum of their parts, and that examining the relationships between those parts can lead to a better understanding of the whole ( Bertalanffy, 1968).

Complex systems, unlike simple, linear systems, can exhibit emergent properties that cannot be predicted from the behaviour of individual components. Therefore, systems theorists often employ interdisciplinary approaches to study complex systems, drawing on fields such as mathematics, physics, psychology, and sociology. This allows them to analyse patterns of behaviour and feedback-controlled regulation processes (Skyttner, 2005).

Applications of systems theory can be found in diverse fields such as management, ecology, and social science. By adopting a complete approach to understanding systems, researchers can gain insight into individual level behaviours and macro and policy levels of organisations.

In essence, systems theory is an invaluable tool for understanding the complex and dynamic systems that shape our daily lives (Bertalanffy, 1968).

Feedback loops in classrooms create cycles where student behaviours and teacher responses reinforce each other, either positively or negatively. For example, when a teacher consistently rewards participation, students participate more, which leads to more rewards. Understanding these loops helps teachers break negative cycles and strengthen positive ones through strategic feedback interventions.

Feedback loops are a central concept in systems theory, particularly in the study of behavioural dynamics. These loops refer to the cyclical flow of information between components within a system. Positive feedback loops amplify the effects of a particular behaviour, leading to the perpetuation or escalation of patterns of behaviour.

On the other hand, negative feedback loops act as a regulatory mechanism, dampening the effects of behaviour and maintaining system stability. In educational settings, understanding these different types of feedback loops allows teachers to design interventions that either amplify desired behaviours or dampen problematic ones.

Consider how a negative feedback loop might work in practice: when a student exhibits transformative behaviour, the teacher responds with a consequence, which should ideally reduce the transformative behaviour. However, if the consequence inadvertently provides the attention the student seeks, it may create a positive feedback loop instead, reinforcing the unwanted behaviour. This is why systems thinking requires educators to look beyond immediate cause-and-effect relationships and examine the broader patterns that emerge over time.

The key to managing classroom feedback loops lies in recognising that every intervention creates ripple effects throughout the system. Successful teachers learn to anticipate these effects and design their responses to strengthen positive loops whilst interrupting negative ones. This might involve changing the timing of feedback, adjusting the type of attention given to different behaviours, or modifying the classroom environment to support more productive interactions.

Systems theory transforms classroom management from a reactive discipline approach to a proactive design challenge. Rather than addressing individual behavioural incidents in isolation, teachers using systems thinking examine the underlying structures that generate patterns of behaviour. This includes physical environment, social dynamics, academic expectations, and communication patterns that all interact to create the classroom climate.

Effective systems-based classroom management begins with mapping the invisible connections in your classroom. Start by observing how changes in one area affect others: notice how seating arrangements influence peer relationships, how assessment practices affect student motivation, or how your own energy levels impact the entire room's atmosphere. These observations reveal the use points where small changes can create significant positive shifts across the whole system.

One powerful application involves creating positive interdependence amongst students through collaborative learning structures. When students' success becomes connected to their peers' success, the social system naturally reinforces helpful behaviours and discourages transformative ones. This shifts the responsibility for maintaining a positive learning environment from solely the teacher to the entire classroom community.

Another key strategy involves designing feedback systems that provide multiple types of information to students about their progress. Rather than relying solely on grades or verbal feedback, systems-thinking teachers create environments where students receive continuous information about their learning through peer interactions, self-reflection opportunities, and visible progress indicators. This creates self-regulating loops that reduce the need for external management interventions.

Whilst systems theory offers valuable insights for education, it also presents practical challenges for busy teachers and school leaders. The complexity of educational systems can make it difficult to identify which variables are most important to address, and the interconnected nature of systems means that changes often take time to show results. Teachers may feel overwhelmed by the need to consider multiple factors simultaneously when addressing classroom issues.

Additionally, systems thinking requires a shift from traditional linear problem-solving approaches that many educators are comfortable with. It demands patience and tolerance for uncertainty, as the effects of interventions may not be immediately apparent or may manifest in unexpected ways. Schools operating under pressure to show rapid improvement may find it challenging to invest in systems-based approaches that require longer timeframes to demonstrate their effectiveness.

Another limitation lies in the difficulty of measuring systemic changes using traditional educational assessment tools. Standardised tests and individual performance metrics may not capture the improvements in classroom climate, peer relationships, or long-term learning habits that systems interventions are designed to create. This can make it challenging to justify systems-based approaches in environments focused on quantifiable outcomes.

Systems theory offers educators a transformative lens for understanding and improving complex learning environments. By recognising schools and classrooms as interconnected systems rather than collections of isolated parts, teachers can design more effective interventions that address root causes rather than symptoms. The power of this approach lies in its ability to reveal hidden connections and use points that traditional linear thinking often misses.

For practicing teachers, adopting systems thinking means becoming more strategic about classroom decisions and more observant about the ripple effects of interventions. It requires patience and willingness to experiment, as systems-based improvements often unfold gradually through multiple feedback loops. However, the long-term benefits include more sustainable behaviour improvements, stronger classroom communities, and learning environments that support all students' development.

As education continues to grapple with increasingly complex challenges, systems theory provides essential tools for creating adaptive, resilient learning environments. By understanding how individual elements interact to create emergent properties at the classroom and school level, educators can move beyond quick fixes to develop comprehensive approaches that address the underlying structures shaping student experience and achievement.

For educators interested in deepening their understanding of systems theory in educational contexts, the following research provides valuable theoretical foundations and practical applications:

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/systems-theories#article","headline":"Systems Theory in Education: Understanding Complex Learning Environments","description":"Explore systems theory and its applications in education. Learn how schools function as complex systems and how understanding interconnections improves...","datePublished":"2023-06-30T13:45:28.285Z","dateModified":"2026-01-26T10:09:32.212Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/systems-theories"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/69524f66df0fde49d9e54f77_69524f64df0fde49d9e54efa_systems-theories-infographic.webp","wordCount":3294},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/systems-theories#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"Systems Theory in Education: Understanding Complex Learning Environments","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/systems-theories"}]},{"@type":"FAQPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/systems-theories#faq","mainEntity":[{"@type":"Question","name":"What is systems theory in education and why should teachers care about it?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Systems theory is a framework that helps educators understand schools and classrooms as interconnected wholes rather than isolated parts, where changes in one area affect the entire system. Teachers should care because it explains why single interventions sometimes produce unexpected results and hel"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"How do feedback loops work in classroom behaviour management?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Feedback loops create cycles where student behaviours and teacher responses reinforce each other, either positively or negatively. For example, consistently rewarding participation leads to more student engagement, which creates more opportunities for rewards, whilst negative cycles can escalate pro"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What are the key components that make up a classroom system?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"A classroom system includes students, teachers, physical environment, curriculum, rules, and social dynamics that all interact continuously. These components influence each other through relationships like peer pressure, teacher expectations, seating arrangements, and environmental factors, meaning "}},{"@type":"Question","name":"Why do well-intentioned classroom interventions sometimes backfire or create new problems?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Interventions can backfire because they often focus on individual issues without considering the whole-class dynamics and interconnected relationships within the classroom system. For example, moving a disruptive student to the front row might solve one problem but create new social groupings and be"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"How can understanding systems theory help with SENCO work and identifying barriers to learning?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Systems thinking helps SENCOs look beyond individual assessments to understand how family systems, peer relationships, and classroom environments create hidden patterns that affect pupil progress. This broader perspective reveals real barriers to learning that traditional assessments might miss, suc"}}]}]}