Just World Hypothesis

Delve into the Just World Hypothesis – examine the cognitive bias that shapes our beliefs about fairness, justice, and personal responsibility.

Delve into the Just World Hypothesis – examine the cognitive bias that shapes our beliefs about fairness, justice, and personal responsibility.

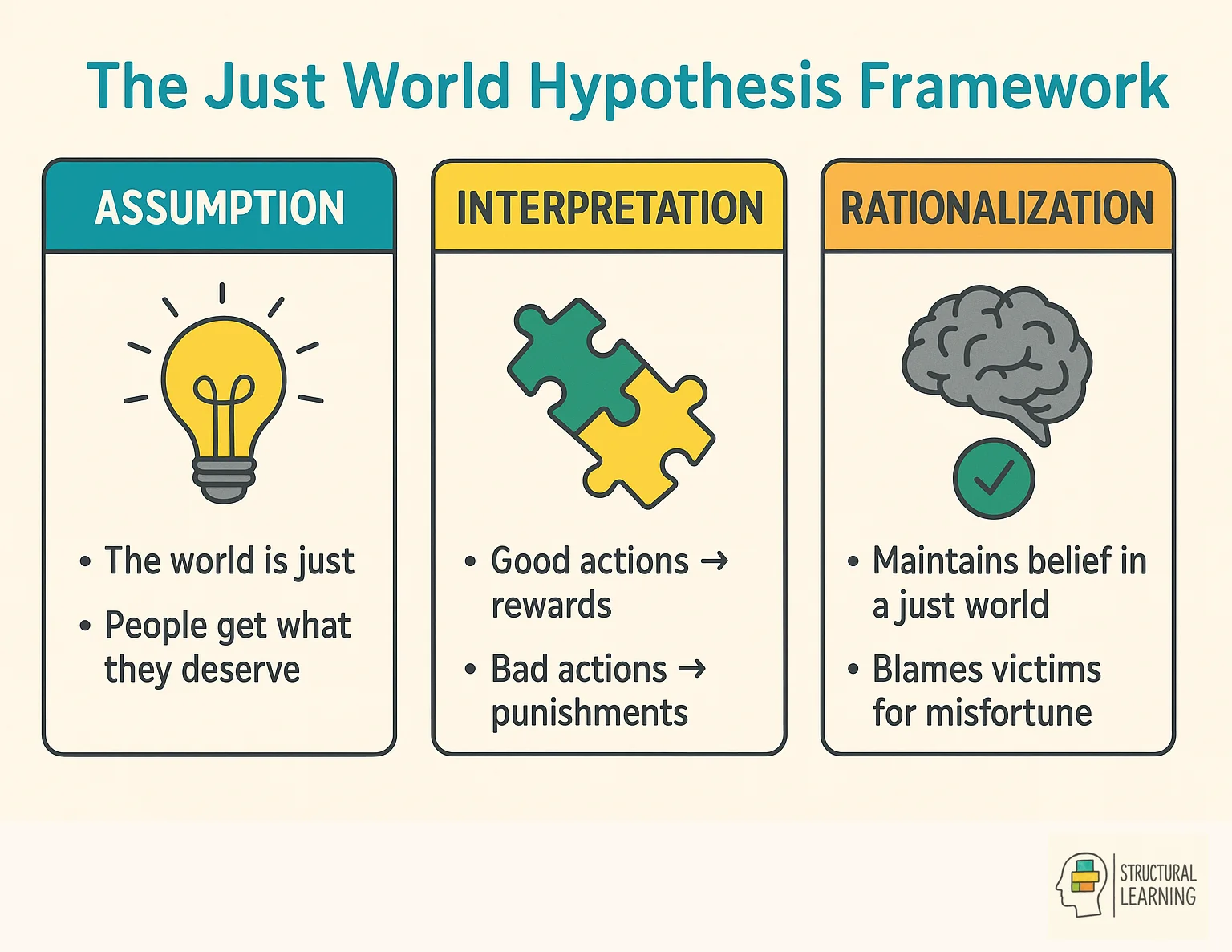

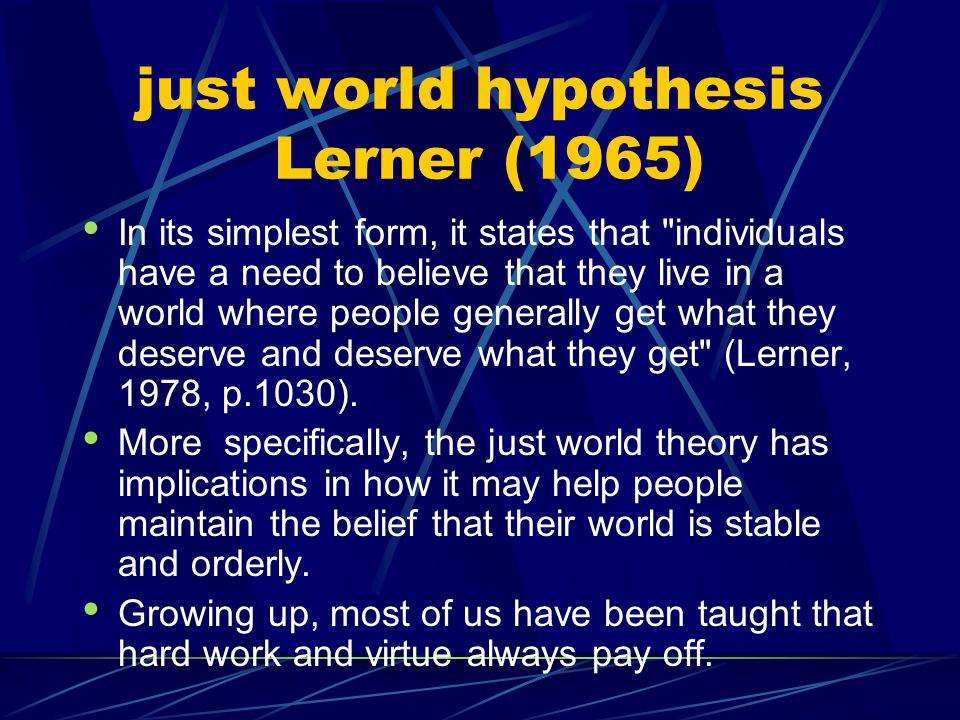

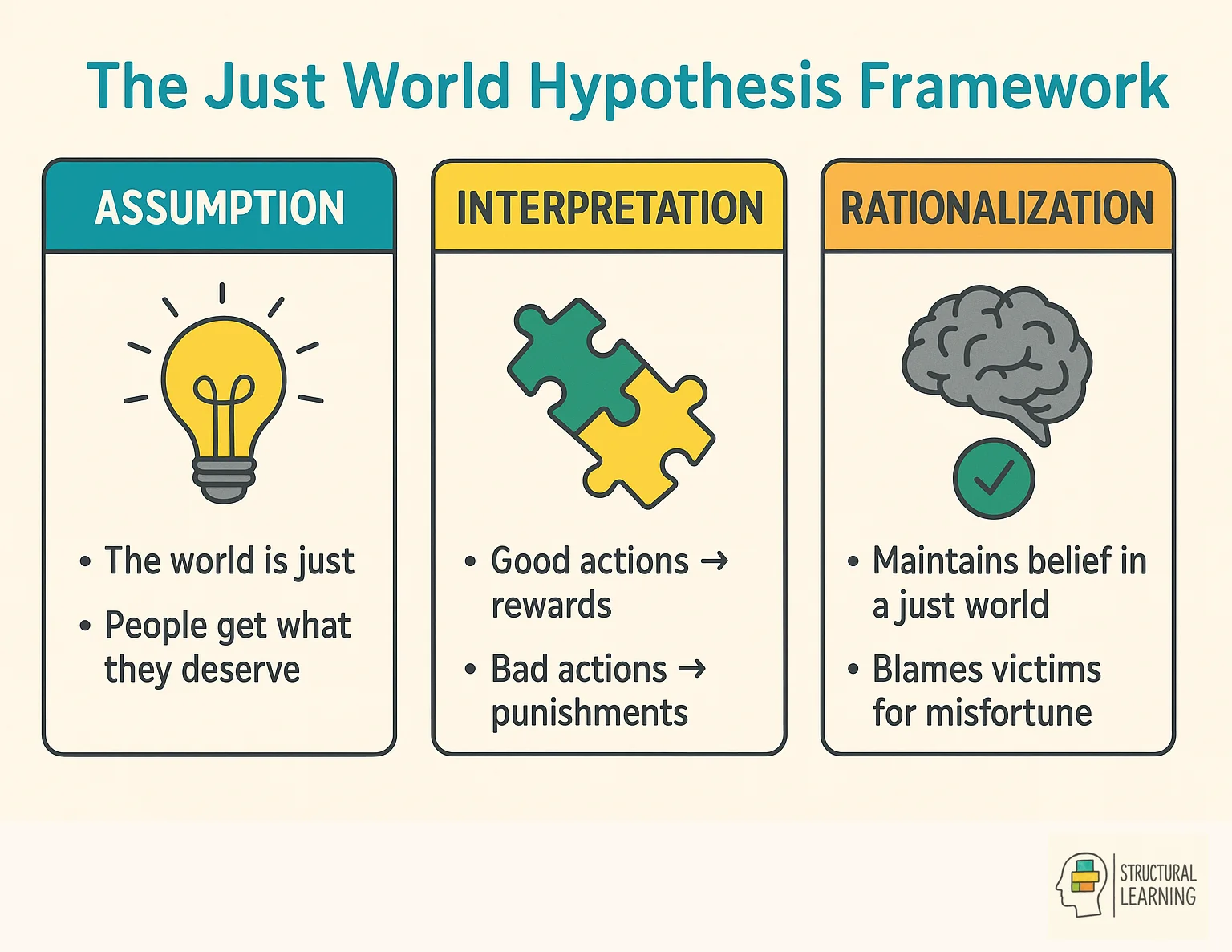

The just world hypothesis is a psychological theory suggesting that people believe the world is inherently fair, where individuals get what they deserve and deserve what they get. This concept was first introduced by psychologist Melvin Lerner in the 1960s to explain why people often blame victims for their misfortunes.

The just-world hypothesis, also known as just-world theory, is a psychological concept proposing that individuals possess a strong belief in the inherent fairness of the world, where people get what they deserve, and deserve what they get.

This theory was first introduced by Melvin Lerner in the 1960s, suggesting that the belief in a just world can lead to negative attitudes towards innocent victims, as individuals attempt to rationalize their suffering and maintain their faith in a fair and orderly universe.

This desire for moral balance can influence how people perceive political leaders, personal beliefs, and the events they encounter in their daily lives. When faced with evidence of , individuals may engage in prosocial behaviour to restore their belief in justice or, conversely, blame the victim for their plight, assuming that they must have engaged in dishonest behaviour or made poor choices to justify their situation.

The just-world hypothesis has significant implications for understanding social attitudes, prejudice, and victim-blaming. By acknowledging the role of cognitive bias in shaping our perceptions of others, educators can use dialogic approaches and other effective teaching strategies to encourage students to critically eval uate their beliefs and creates empathy towards those facing adversity.

Recent research has expanded upon Lerner's original work, examining the cross-cultural prevalence of just-world beliefsand exploring the complex relationship between the just-world hypothesis and personal values, social attitudes, and moral reasoning.

People believe in a just world because it provides psychological comfort and a sense of control over their environment, reducing anxiety about random misfortune. This belief helps individuals maintain the illusion that good behaviour will be rewarded and bad behaviour punished, making the world seem more predictable and orderly.

Taking a closer look at the just-world hypothesis, we can see that the desire for a fair and just world operates like an invisible hand, guiding our perceptions of norm-breaking behaviour, social attitudes, and everyday experiences. This yearning for balance is deeply rooted in our psychological need for stability and predictability, which influences how we make sense of the world around us.

Melvin J. Lerner's pioneering studies on just-world beliefs revealed that people are inclined to think that good things happen to good people, while bad people inevitably face negative consequences. This line of thinking, however, can lead to the oversimplification of complex social issues and, in some cases, result in victim-blaming when confronted with evidence of injustice or suffering.

In the vast ocean of human experience, just-world beliefs serve as an anchor that grounds our understanding of social behaviour within predictable spheres of belief. However, this anchoring effect may also limit our ability to recognise and empathize with the diverse range of experiences that individuals may encounter in their lives.

To navigate the complex interplay between just-world beliefs and the influence of people's actions, be aware of our own cognitive biases and the potential pitfalls of assuming that all outcomes are entirely deserved. By developing a more nuanced understanding of the factors that contribute to both success and adversity, we can cultivate empathy, challenge our assumptions about dishonesty, and promote a more compassionate and inclusive worldview.

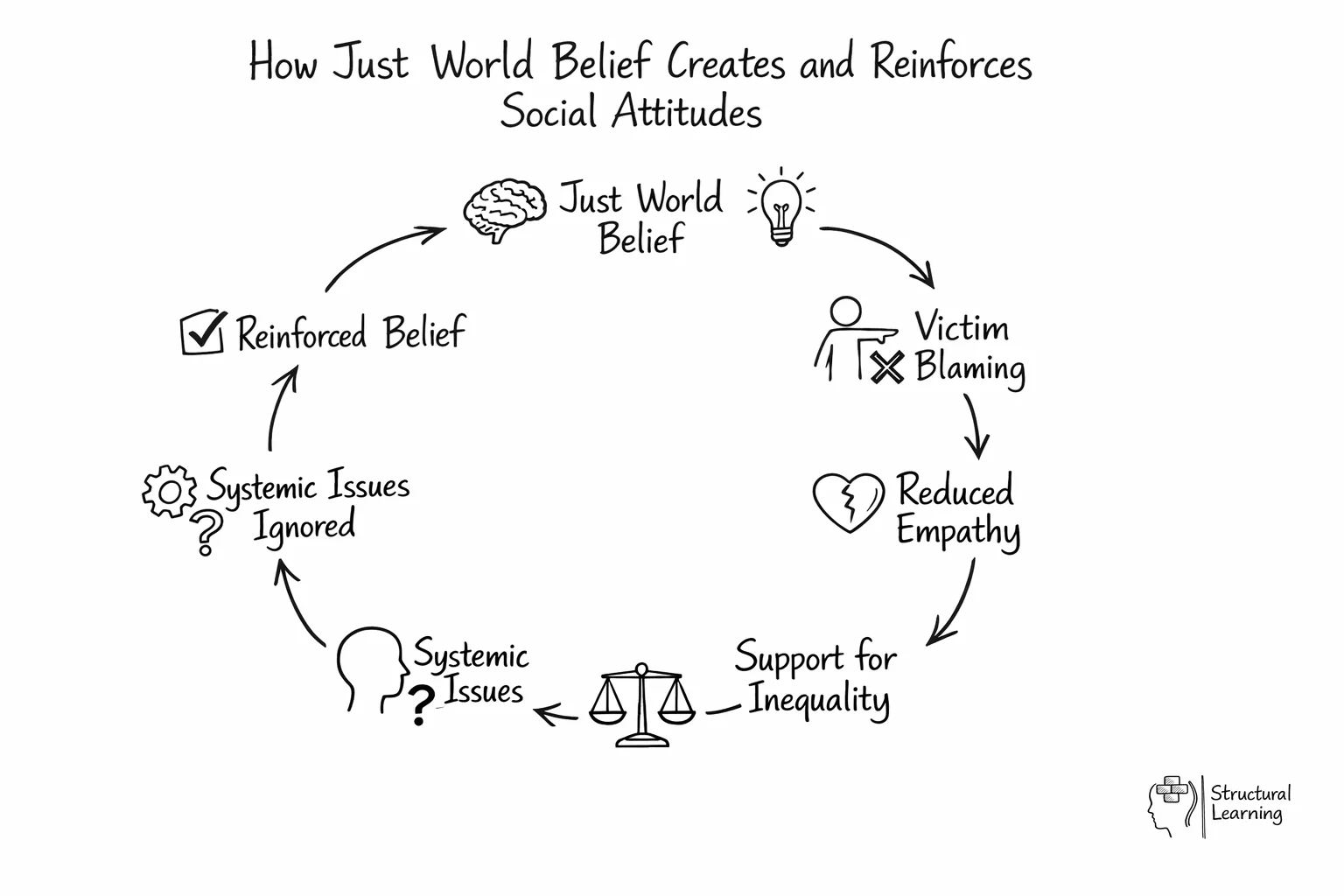

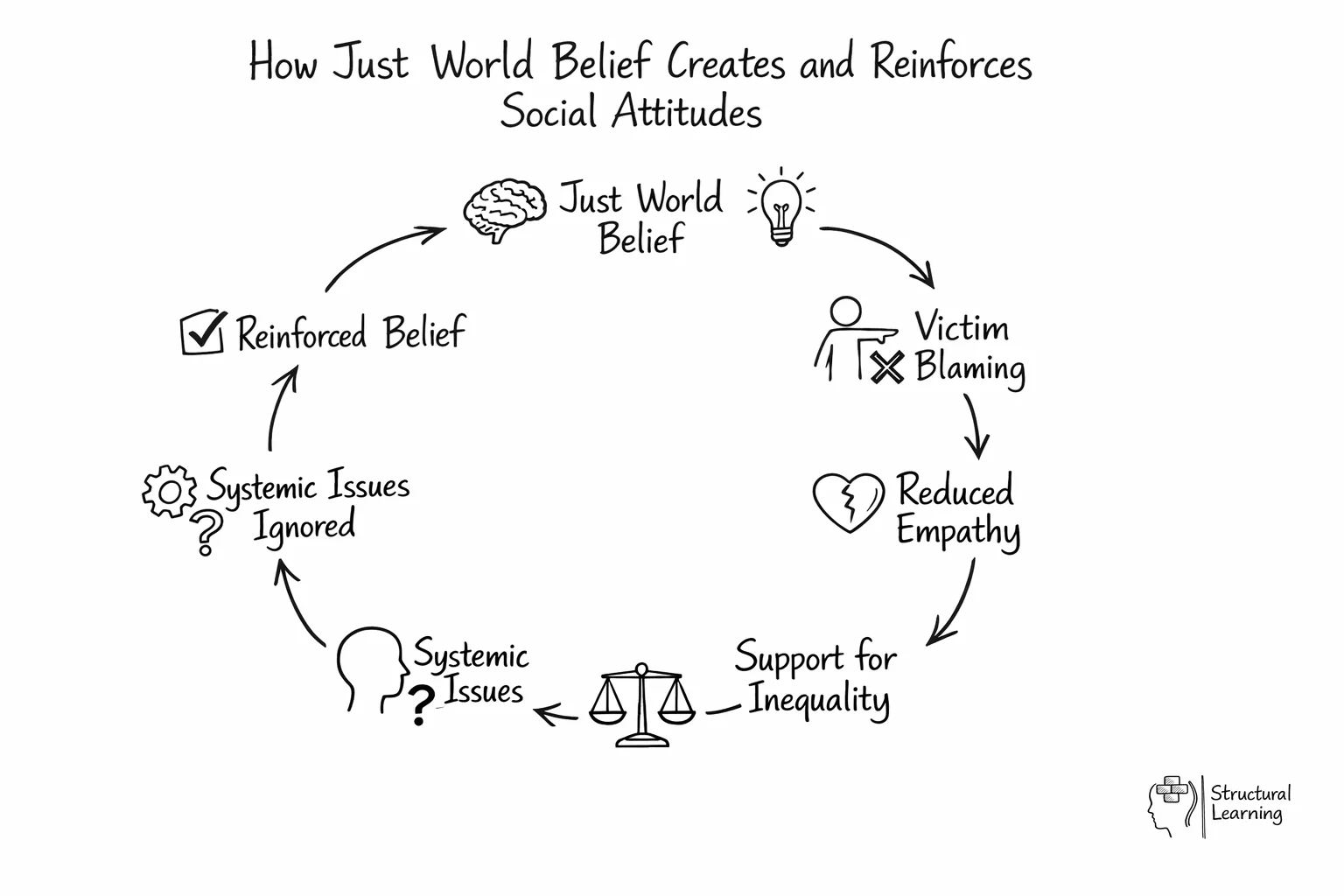

The just world hypothesis perpetuates social inequality by causing people to blame disadvantaged individuals for their circumstances rather than recognising systemic issues. This leads to reduced support for social programs and policies aimed at addressing inequality, as people assume the poor or marginalized somehow deserve their situation.

feedback loop reinforcing social inequality" loading="lazy">

feedback loop reinforcing social inequality" loading="lazy">The just-world hypothesis not only shapes our understanding of individual experiences but also has significant implications for social inequalities. When people view the world as inherently fair and just, they may inadvertently perpetuate existing disparities by rationalizing unfair outcomes as deserved consequences. This mindset can serve as a double-edged sword, promoting a sense of stability and order on one hand while reinforcing systemic injustices on the other.

In the field of dishonesty, for example, the just-world hypothesis may lead individuals to perceive acts of dishonest behaviour as isolated incidents rather than symptoms of broader social issues.

Researchers have conducted simple studies examining the influence of people's just-world beliefs on their evaluations of dishonest behaviour, revealing that individuals with stronger just-world beliefs tend to attribute negative outcomes to personal characteristics rather than contextual factors.

This questioning can exacerbate existing social inequalities by obscuring the role of systemic barriers i n shaping everyday life.

Another key psychological concept related to the just-world hypothesis is cognitive dissonance, which refers to the discomfort individuals experience when confronted with information that contradicts their worldview. When individuals encounter situations that challenge their belief in a just world, such as witnessing innocent suffering or systemic discrimination, they may experience psychological discomfort that motivates them to restore cognitive balance.

This restoration can manifest in various ways, including victim-blaming, denial of systemic issues, or the attribution of negative outcomes to personal failings rather than structural inequalities. For educators working in diverse communities, understanding how the just-world hypothesis influences student perceptions of social issues is crucial for developing critical thinking skills and promoting social awareness.

Research has shown that individuals with stronger just-world beliefs are more likely to support policies that maintain the status quo and less likely to advocate for systemic change. This tendency can perpetuate cycles of disadvantage and limit opportunities for meaningful social progress, making it essential for educators to address these cognitive biases through thoughtful curriculum design and classroom discussions.

Understanding the just world hypothesis is essential for educators as it influences how students interpret social issues, evaluate fairness, and respond to diversity in the classroom. Teachers can use this knowledge to develop more effective strategies for promoting empathy, critical thinking, and social awareness amongst their pupils.

In the classroom environment, the just-world hypothesis can significantly impact how students perceive academic achievement, peer relationships, and social dynamics. Students who strongly believe in a just world may struggle to understand why some classmates face challenges related to socioeconomic disadvantage, learning difficulties, or family circumstances beyond their control.

Teachers can address these perceptions by incorporating social justice education approaches that help students examine the complex factors contributing to different life outcomes. This might include exploring case studies, engaging in perspective-taking activities, and discussing how systemic barriers can impact individual opportunities and achievements.

Furthermore, educators can utilise collaborative learning strategies that bring together students from diverse backgrounds, encouraging them to share their experiences and challenge assumptions about success and failure. By creating opportunities for meaningful dialogue and reflection, teachers can help students develop more nuanced understandings of fairness and justice.

The implications of just-world thinking extend beyond individual classroom interactions to broader educational policies and practices. Schools that operate under just-world assumptions may inadvertently blame students or families for academic struggles without adequately addressing systemic factors such as resource allocation, cultural responsiveness, or inclusive teaching practices.

The just world hypothesis represents a fundamental aspect of human psychology that profoundly influences how we interpret events, evaluate others, and respond to social challenges. Whilst this cognitive bias can provide psychological comfort and a sense of order, it can also lead to victim-blaming, perpetuate social inequalities, and limit our capacity for empathy and understanding.

For educators, awareness of the just world hypothesis offers valuable insights into student thinking and behaviour, providing opportunities to develop more effective teaching strategies that promote critical thinking and social awareness. By acknowledging the role of this cognitive bias in shaping perceptions, teachers can create learning environments that encourage students to examine their assumptions, consider multiple perspectives, and develop more nuanced understandings of fairness and justice.

Going forward, continued research into the just world hypothesis and its educational implications will be essential for developing evidence-based approaches to teaching about social issues, promoting empathy, and developing inclusive classroom communities. As educators, our understanding of this psychological phenomenon can serve as a powerful tool for creating positive social change and preparing students to engage thoughtfully with the complexities of our interconnected world.

For educators interested in exploring the just world hypothesis and its educational implications in greater depth, the following research papers provide valuable insights:

The just world hypothesis is a psychological theory suggesting that people believe the world is inherently fair, where individuals get what they deserve and deserve what they get. This concept was first introduced by psychologist Melvin Lerner in the 1960s to explain why people often blame victims for their misfortunes.

The just-world hypothesis, also known as just-world theory, is a psychological concept proposing that individuals possess a strong belief in the inherent fairness of the world, where people get what they deserve, and deserve what they get.

This theory was first introduced by Melvin Lerner in the 1960s, suggesting that the belief in a just world can lead to negative attitudes towards innocent victims, as individuals attempt to rationalize their suffering and maintain their faith in a fair and orderly universe.

This desire for moral balance can influence how people perceive political leaders, personal beliefs, and the events they encounter in their daily lives. When faced with evidence of , individuals may engage in prosocial behaviour to restore their belief in justice or, conversely, blame the victim for their plight, assuming that they must have engaged in dishonest behaviour or made poor choices to justify their situation.

The just-world hypothesis has significant implications for understanding social attitudes, prejudice, and victim-blaming. By acknowledging the role of cognitive bias in shaping our perceptions of others, educators can use dialogic approaches and other effective teaching strategies to encourage students to critically eval uate their beliefs and creates empathy towards those facing adversity.

Recent research has expanded upon Lerner's original work, examining the cross-cultural prevalence of just-world beliefsand exploring the complex relationship between the just-world hypothesis and personal values, social attitudes, and moral reasoning.

People believe in a just world because it provides psychological comfort and a sense of control over their environment, reducing anxiety about random misfortune. This belief helps individuals maintain the illusion that good behaviour will be rewarded and bad behaviour punished, making the world seem more predictable and orderly.

Taking a closer look at the just-world hypothesis, we can see that the desire for a fair and just world operates like an invisible hand, guiding our perceptions of norm-breaking behaviour, social attitudes, and everyday experiences. This yearning for balance is deeply rooted in our psychological need for stability and predictability, which influences how we make sense of the world around us.

Melvin J. Lerner's pioneering studies on just-world beliefs revealed that people are inclined to think that good things happen to good people, while bad people inevitably face negative consequences. This line of thinking, however, can lead to the oversimplification of complex social issues and, in some cases, result in victim-blaming when confronted with evidence of injustice or suffering.

In the vast ocean of human experience, just-world beliefs serve as an anchor that grounds our understanding of social behaviour within predictable spheres of belief. However, this anchoring effect may also limit our ability to recognise and empathize with the diverse range of experiences that individuals may encounter in their lives.

To navigate the complex interplay between just-world beliefs and the influence of people's actions, be aware of our own cognitive biases and the potential pitfalls of assuming that all outcomes are entirely deserved. By developing a more nuanced understanding of the factors that contribute to both success and adversity, we can cultivate empathy, challenge our assumptions about dishonesty, and promote a more compassionate and inclusive worldview.

The just world hypothesis perpetuates social inequality by causing people to blame disadvantaged individuals for their circumstances rather than recognising systemic issues. This leads to reduced support for social programs and policies aimed at addressing inequality, as people assume the poor or marginalized somehow deserve their situation.

feedback loop reinforcing social inequality" loading="lazy">

feedback loop reinforcing social inequality" loading="lazy">The just-world hypothesis not only shapes our understanding of individual experiences but also has significant implications for social inequalities. When people view the world as inherently fair and just, they may inadvertently perpetuate existing disparities by rationalizing unfair outcomes as deserved consequences. This mindset can serve as a double-edged sword, promoting a sense of stability and order on one hand while reinforcing systemic injustices on the other.

In the field of dishonesty, for example, the just-world hypothesis may lead individuals to perceive acts of dishonest behaviour as isolated incidents rather than symptoms of broader social issues.

Researchers have conducted simple studies examining the influence of people's just-world beliefs on their evaluations of dishonest behaviour, revealing that individuals with stronger just-world beliefs tend to attribute negative outcomes to personal characteristics rather than contextual factors.

This questioning can exacerbate existing social inequalities by obscuring the role of systemic barriers i n shaping everyday life.

Another key psychological concept related to the just-world hypothesis is cognitive dissonance, which refers to the discomfort individuals experience when confronted with information that contradicts their worldview. When individuals encounter situations that challenge their belief in a just world, such as witnessing innocent suffering or systemic discrimination, they may experience psychological discomfort that motivates them to restore cognitive balance.

This restoration can manifest in various ways, including victim-blaming, denial of systemic issues, or the attribution of negative outcomes to personal failings rather than structural inequalities. For educators working in diverse communities, understanding how the just-world hypothesis influences student perceptions of social issues is crucial for developing critical thinking skills and promoting social awareness.

Research has shown that individuals with stronger just-world beliefs are more likely to support policies that maintain the status quo and less likely to advocate for systemic change. This tendency can perpetuate cycles of disadvantage and limit opportunities for meaningful social progress, making it essential for educators to address these cognitive biases through thoughtful curriculum design and classroom discussions.

Understanding the just world hypothesis is essential for educators as it influences how students interpret social issues, evaluate fairness, and respond to diversity in the classroom. Teachers can use this knowledge to develop more effective strategies for promoting empathy, critical thinking, and social awareness amongst their pupils.

In the classroom environment, the just-world hypothesis can significantly impact how students perceive academic achievement, peer relationships, and social dynamics. Students who strongly believe in a just world may struggle to understand why some classmates face challenges related to socioeconomic disadvantage, learning difficulties, or family circumstances beyond their control.

Teachers can address these perceptions by incorporating social justice education approaches that help students examine the complex factors contributing to different life outcomes. This might include exploring case studies, engaging in perspective-taking activities, and discussing how systemic barriers can impact individual opportunities and achievements.

Furthermore, educators can utilise collaborative learning strategies that bring together students from diverse backgrounds, encouraging them to share their experiences and challenge assumptions about success and failure. By creating opportunities for meaningful dialogue and reflection, teachers can help students develop more nuanced understandings of fairness and justice.

The implications of just-world thinking extend beyond individual classroom interactions to broader educational policies and practices. Schools that operate under just-world assumptions may inadvertently blame students or families for academic struggles without adequately addressing systemic factors such as resource allocation, cultural responsiveness, or inclusive teaching practices.

The just world hypothesis represents a fundamental aspect of human psychology that profoundly influences how we interpret events, evaluate others, and respond to social challenges. Whilst this cognitive bias can provide psychological comfort and a sense of order, it can also lead to victim-blaming, perpetuate social inequalities, and limit our capacity for empathy and understanding.

For educators, awareness of the just world hypothesis offers valuable insights into student thinking and behaviour, providing opportunities to develop more effective teaching strategies that promote critical thinking and social awareness. By acknowledging the role of this cognitive bias in shaping perceptions, teachers can create learning environments that encourage students to examine their assumptions, consider multiple perspectives, and develop more nuanced understandings of fairness and justice.

Going forward, continued research into the just world hypothesis and its educational implications will be essential for developing evidence-based approaches to teaching about social issues, promoting empathy, and developing inclusive classroom communities. As educators, our understanding of this psychological phenomenon can serve as a powerful tool for creating positive social change and preparing students to engage thoughtfully with the complexities of our interconnected world.

For educators interested in exploring the just world hypothesis and its educational implications in greater depth, the following research papers provide valuable insights:

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/just-world-hypothesis#article","headline":"Just World Hypothesis","description":"\nDelve into the Just World Hypothesis – examine the cognitive bias that shapes our beliefs about fairness, justice, and personal responsibility.","datePublished":"2023-05-05T11:19:02.583Z","dateModified":"2026-01-26T10:09:32.212Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/just-world-hypothesis"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/69525589f7eac78ee2c14b31_695255872d35fe96768e90b7_just-world-hypothesis-infographic.webp","wordCount":2808},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/just-world-hypothesis#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"Just World Hypothesis","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/just-world-hypothesis"}]}]}