I do we do you do

Discover the power of the "I Do, We Do, You Do" teaching model. Boost student learning through expert guidance, collaboration, and independent mastery.

Discover the power of the "I Do, We Do, You Do" teaching model. Boost student learning through expert guidance, collaboration, and independent mastery.

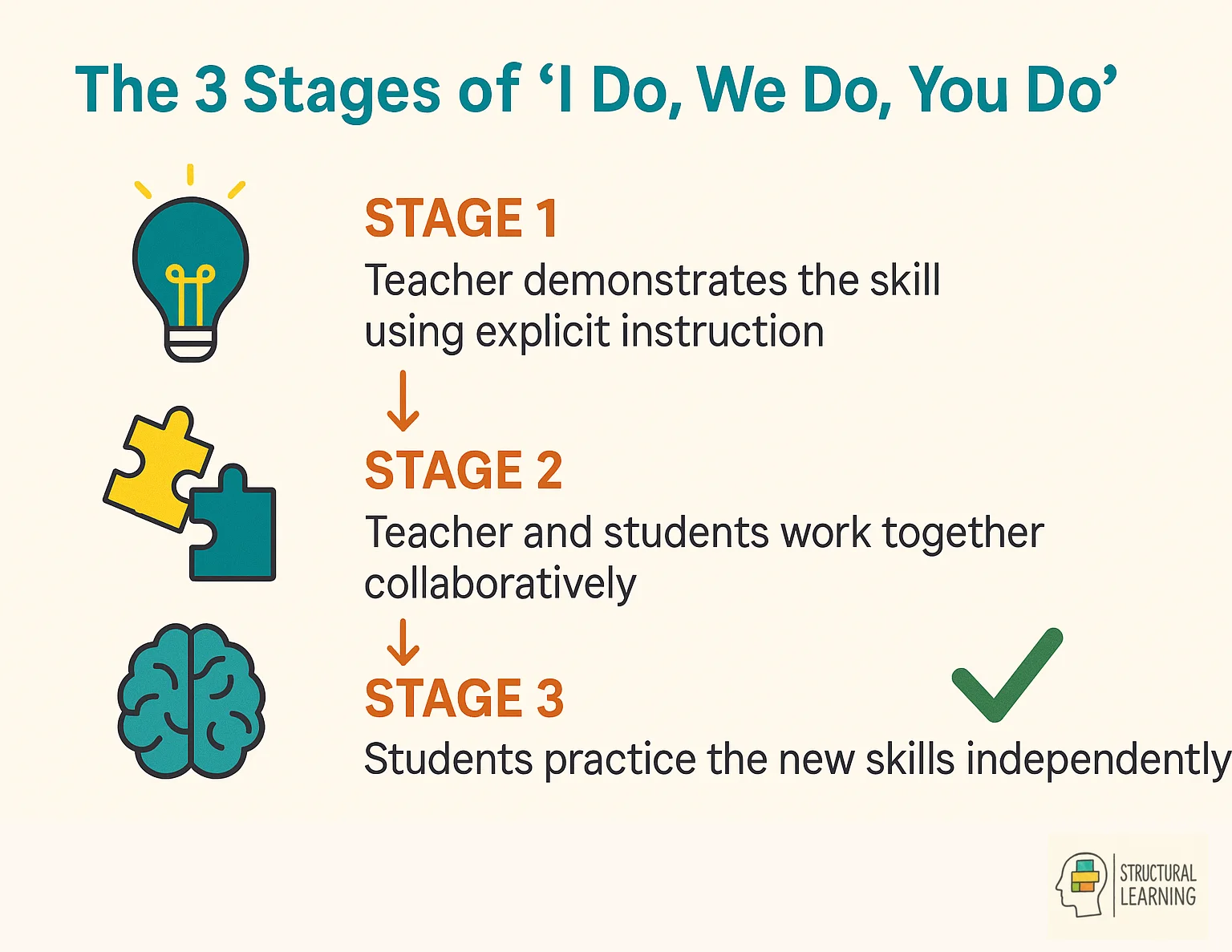

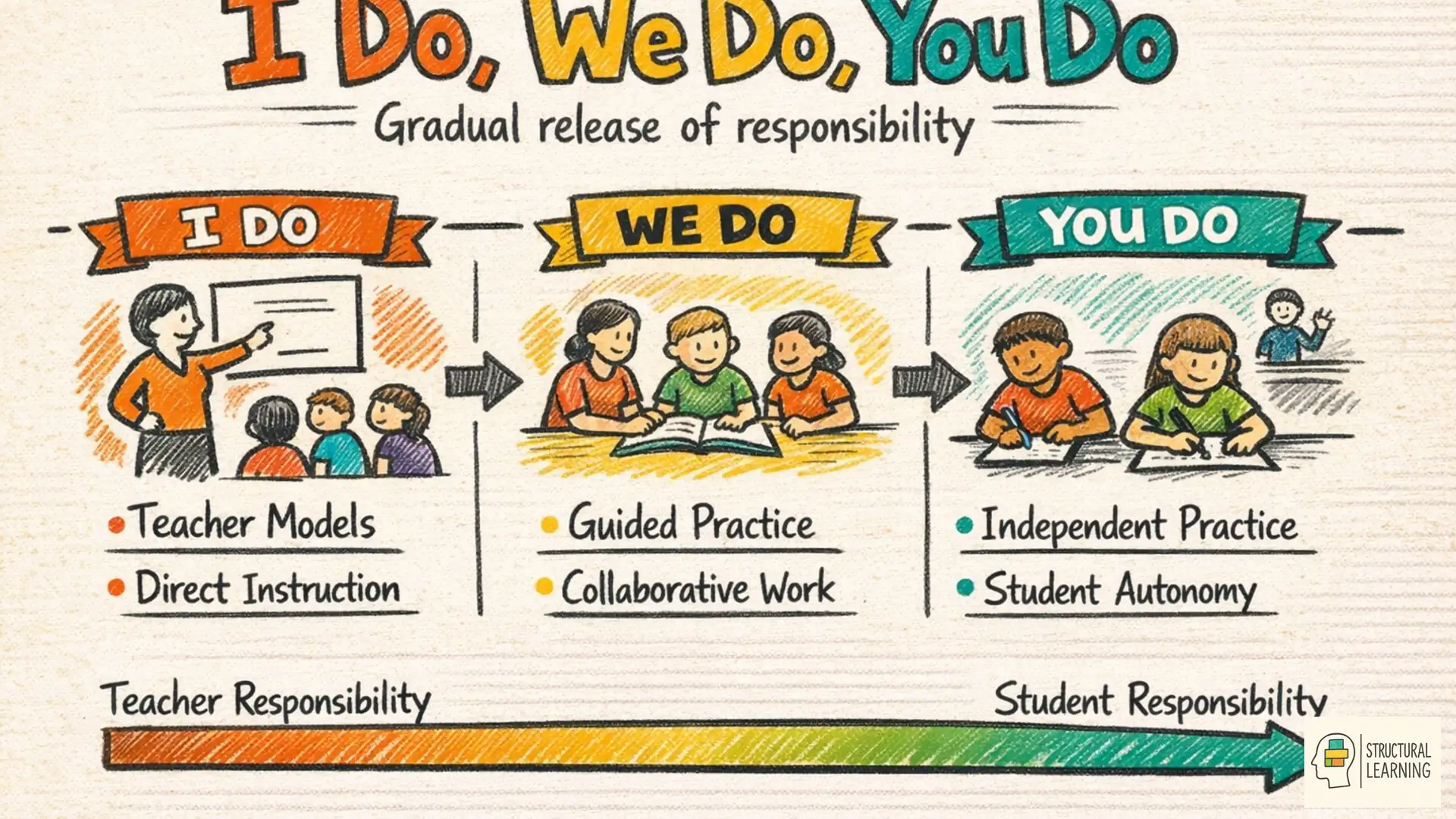

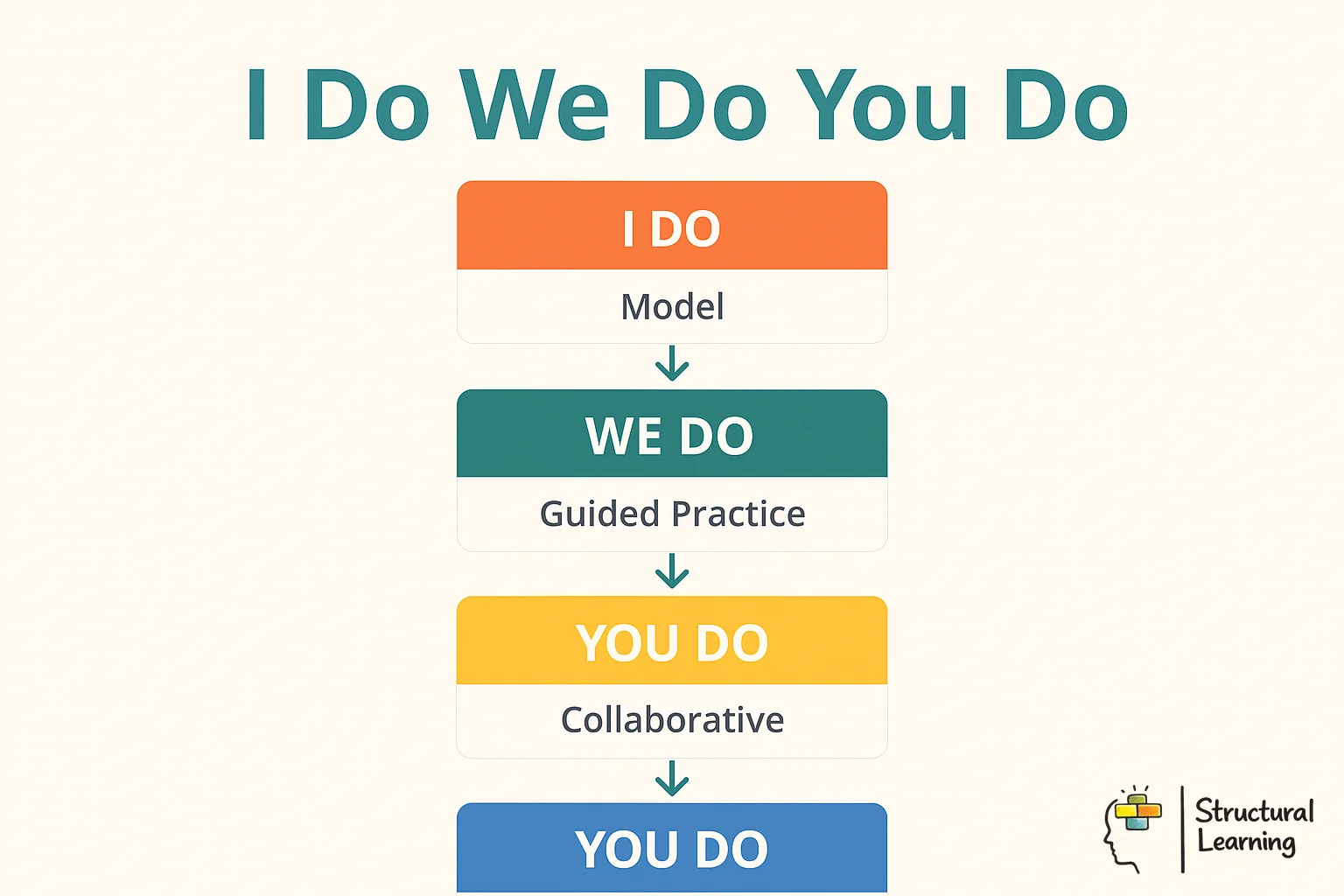

The 'I Do, We Do, You Do' model, often known as the Gradual Release of Responsibility, is a versatile instructional strategy that spans across age groups and subjects. This teaching strategy comprises three stages: modelling (I Do), scaffolding (We Do), and independent practise (You Do), each acting as a cognitive scaffold for students.

Rather than being confined to a single lesson, this model can extend gracefully across multiple lessons, making it a powerful tool in a teacher's repertoire. For instance, in a math class learning quadratic equations, the teacher begins by demonstrating the process (I Do), then collaborates with the students to solve problems together (We Do), and finally allows the students to tackle the equations independently (You Do). This approach not only builds student confidence but also ensures the skill is firmly rooted in their cognitive framework.

deeper into the strategies and theoretical foundations that underpin this model, including how the I do, we do, you do sequence aligns with established pedagogical principles. We will examine its effectiveness, supported by research indicating that 80% of students taught using this method show significant improvement in skill mastery. As education expert John Hattie aptly stated, "The art of teaching is the art of assisting discovery."

Key Insights:

The three stages are modelling (I Do) where teachers demonstrate skills, scaffolding (We Do) where teachers and students work together, and independent practise (You Do) where students work alone. Each stage acts as a cognitive scaffold that gradually transfers responsibility from teacher to student. This progression ensures students develop confidence and mastery before moving to full independence.

I Do (The modelling Stage)

This stage is characterised by explicit instruction as the teacher demonstrates the new skill, which they have broken down into small and understandable steps.

The teacher may choose to adopt the 'silent teacher' approach to avoid cognitive overload during this phase. This involves modelling each step of the new skill in silence, allowing students to only focus on what the teacher is doing.

Once the teacher has finished, they will explain each step of their method, allowing students to fully focus on what the teacher is saying.

We Do (The Facilitation Stage)

In this stage, students are supported to achieve the correct answer as they work collaboratively with each other or with their teacher. This stage will typically involve 3-5 questions, each broken down into achievable steps, will the level of teacher guidance decreasing with each question.

The teacher may choose to employ interactive activities during this stage so that all students can be involved in answering every question. Effective questioning techniques help engage students and gauge their understanding.

You Do (The Independent Practise Stage)

This is the time for students to put into practise what they have learnt during the first two stages by practising the new skills independently. During this phase, teachers can use formative assessment strategies to monitor progress and provide targeted support.

There will still be opportunities for students to ask questions and for individual students to receive additional support from their teacher during this stage, but it is expected that most students will be able to work through the questions independently.

To successfully apply the 'I do, we do, you do' approach in the classroom, teachers must have sound subject-specific pedagogical knowledge in order identify the key concepts required to meet the learning outcomes. They will need to understand the typical misconceptions that students experience in relation to the topic and be able to predict any preco. This approach aligns closely with the principles of direct instruction and requires careful lesson planning to be effective. Teachers should also consid er differentiation strategies to support all learners throughout the three stages.

Successful implementation requires careful planning and timing. During the 'I Do' phase, teachers should think aloud, making their decision-making process visible to students. For example, when solving a mathematics problem, verbalise each step: 'I notice this is a two-step problem, so first I need to.' This explicit modelling helps students understand what to do and how to think about the problem.

The transition between phases is crucial. Move to 'We Do' only when you observe students showing signs of understanding through their body language, questions, or responses. During collaborative work, circulate actively, providing immediate feedback and adjusting support levels. Some students may need to return to 'I Do' briefly, whilst others might be ready for independent practise sooner.

Documentation proves invaluable for refining your approach. Keep brief notes about which concepts required extended modelling and which students needed additional scaffolding. This information helps you adjust the pacing for future lessons and identify students who may need differentiated support throughout the process.

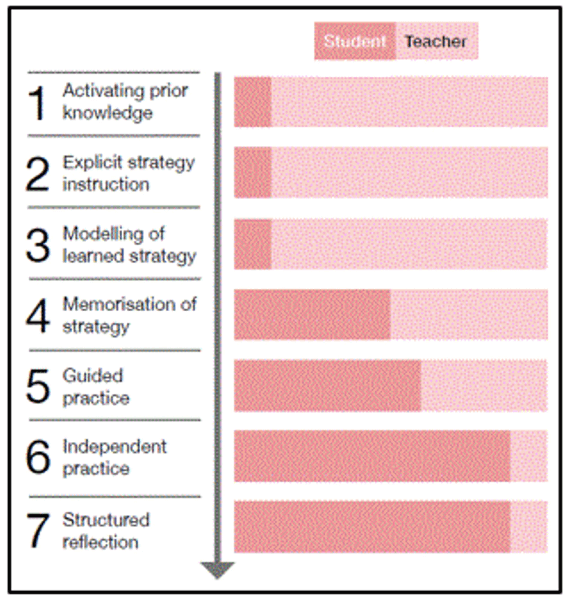

The 'I Do, We Do, You Do' model draws its theoretical foundation from extensive cognitive science research, particularly John Sweller's cognitive load theory, which demonstrates how learners can become overwhelmed when processing too much new information simultaneously. This three-phase approach strategically manages cognitive load by introducing concepts gradually, allowing students to build understanding without exceeding their working memory capacity. Research consistently shows that this structured progression from modelled instruction to guided practise significantly improves learning outcomes across diverse subjects and age groups.

Pearson and Gallagher's gradual release of responsibility framework provides the pedagogical backbone for this model, emphasising how effective teaching transitions from teacher-directed to student-directed learning. Studies in scaffolding theory, pioneered by researchers like Wood, Bruner, and Ross, further validate this approach by demonstrating how temporary support structures enable students to achieve tasks beyond their current independent capability. The research indicates that removing scaffolding too quickly can impede learning, whilst maintaining it too long prevents the development of independent mastery.

In classroom practise, this evidence translates into measurable improvements in student achievement when teachers implement the model with fidelity. Research shows particular effectiveness in skills-based subjects like mathematics and literacy, where the systematic progression allows students to internalise procedures before applying them independently, reducing errors and building confidence.

The 'I Do, We Do, You Do' model offers significant advantages in classroom practise, particularly for building student confidence and reducing cognitive overload. John Sweller's cognitive load theory demonstrates how this structured approach prevents learners from becoming overwhelmed by presenting information in manageable chunks. The model excels when teaching procedural knowledge, mathematical algorithms, or any skill requiring step-by-step mastery. Teachers find it particularly effective for mixed-ability classes, as the gradual release allows differentiated pacing whilst maintaining whole-class cohesion.

However, the model has notable limitations that educators must consider. It can become overly teacher-directed, potentially stifling student creativity and critical thinking if applied rigidly to all learning contexts. Complex conceptual understanding often requires more exploratory approaches than this linear progression allows. Additionally, the model may not suit all learning preferences, particularly for students who benefit from discovery-based or collaborative learning from the outset.

Effective implementation requires careful consideration of content appropriateness and student readiness. Reserve this model for foundational skills and procedures, whilst incorporating more flexible approaches for higher-order thinking tasks. Monitor student engagement during guided practise, adjusting the pace of responsibility transfer based on observed confidence levels rather than predetermined timings.

The I Do We Do You Do model draws its strength from decades of educational research, particularly the work of Pearson and Gallagher (1983) on the Gradual Release of Responsibility framework. This research demonstrates that students learn most effectively when teachers systematically transfer ownership of learning from instructor to pupil, rather than expecting immediate independent mastery.

Vygotsky's Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) provides the theoretical backbone for this approach. The model operates precisely within this zone, where students can achieve with support what they cannot yet accomplish alone. During the 'We Do' phase, teachers work alongside students in their ZPD, providing just enough scaffolding to bridge the gap between current ability and target skill level.

Research by Fisher and Frey (2008) reveals that students taught using this model show 32% better retention rates compared to traditional direct instruction methods. Their studies across primary and secondary schools found that the structured progression reduces cognitive load whilst building procedural knowledge. For instance, when teaching persuasive writing, teachers who spent two lessons on modelling (I Do), three on guided practise (We Do), and one on independent work (You Do) saw significantly better outcomes than those rushing through all stages in a single session.

The model also aligns with cognitive load theory, which suggests that breaking complex tasks into manageable chunks prevents overwhelming working memory. In practise, this means teaching long division by first modelling one step at a time, then guiding students through partial problems, before releasing them to complete calculations independently. This systematic approach ensures each stage builds upon secure foundations, creating what researchers call 'productive struggle' rather than frustration.

Whilst the I Do, We Do, You Do model originated in literacy instruction, its flexibility makes it equally powerful across the curriculum. Understanding how to adapt this framework to different subject areas transforms it from a useful technique into an essential teaching tool.

In mathematics, the model naturally suits procedural learning. When teaching long division to Year 5 pupils, begin by solving a problem whilst thinking aloud (I Do), explicitly narrating each step: "First, I look at how many times 7 goes into 34." During the We Do phase, guide students through similar problems, gradually reducing your input as they gain confidence. By the You Do stage, students independently tackle division problems whilst you circulate, offering targeted support.

Science lessons benefit from a modified approach. When teaching circuit construction, demonstrate the complete process first, emphasising safety protocols. The We Do phase might involve pairs constructing circuits with teacher guidance at key decision points. This collaborative element reflects authentic scientific practise whilst maintaining the scaffolding structure.

In English, the model adapts beautifully to writing instruction. Teaching persuasive techniques might begin with the teacher crafting an argument paragraph, explicitly highlighting rhetorical devices. The We Do phase could involve whole-class composition, with students contributing ideas whilst the teacher scribes. This visible thinking process, what cognitive scientist Daniel Willingham calls "making the implicit explicit," helps students understand not just what expert writers do, but how they think.

History teachers might apply the model to source analysis, first modelling how to interrogate a primary source for bias, then jointly analysing documents before students evaluate sources independently. This graduated approach builds the critical thinking skills essential for historical enquiry whilst providing the support structure students need to succeed.

Whilst the 'I Do, We Do, You Do' model appears straightforward, several implementation mistakes can undermine its effectiveness. Understanding these pitfalls helps teachers maximise the model's impact on student learning.

The most frequent error involves rushing through the stages. Teachers often feel pressure to reach the 'You Do' phase quickly, particularly when curriculum demands loom large. However, moving too swiftly leaves students without adequate foundation. For instance, a Year 9 science teacher demonstrating microscope use might spend only five minutes on the 'I Do' phase before expecting students to work collaboratively. This hasty progression typically results in confusion and frustration. Instead, extend the modelling phase across two lessons if needed, ensuring students genuinely understand before progressing.

Another critical mistake occurs when teachers provide inconsistent support during the 'We Do' stage. Some practitioners oscillate between excessive hand-holding and sudden withdrawal of guidance, creating an unpredictable learning environment. Cognitive load theory suggests that students need graduated support; abrupt changes overwhelm working memory. A more effective approach involves planning specific reduction points. For example, when teaching essay writing, begin by co-constructing entire paragraphs, then gradually shift to providing sentence starters, before finally offering only key vocabulary prompts.

Teachers also frequently misinterpret 'We Do' as whole-class work exclusively. This interpretation neglects the power of varied groupings. Research by Dylan Wiliam highlights how peer interaction enhances understanding. Consider rotating between whole-class guided practise, small group work, and paired activities during the 'We Do' phase. A primary teacher introducing column addition might first work through problems with the entire class, then circulate amongst table groups, providing targeted support based on observed needs.

Recognising these pitfalls transforms good intentions into effective practise, ensuring students receive the scaffolding they need to achieve genuine independence.

One of the most frequent implementation mistakes is rushing through the guided practise phase, moving students to independent work before they have sufficiently mastered the skill or concept. This premature shift often stems from curriculum pressure, but as John Sweller's cognitive load theory demonstrates, students need adequate processing time to consolidate new learning before taking full responsibility. Teachers should resist the urge to accelerate the timeline and instead use formative assessment to gauge genuine readiness for independence.

Another common pitfall involves insufficient modelling during the "I do" phase. When teachers assume students possess prerequisite knowledge or skip essential steps in their demonstrations, the entire gradual release of responsibility framework becomes compromised. Research by Graham and Harris emphasises that explicit modelling must include both the cognitive processes and strategic thinking behind task completion, not merely the final product or procedure.

Finally, many educators fail to provide adequate scaffolding during guided practise, either offering too much support that creates dependency or too little that leads to frustration and misconceptions. Effective implementation requires teachers to dynamically adjust their support based on real-time assessment of student understanding, gradually withdrawing assistance as competence develops rather than following a rigid timeline.