The Generation Effect: Why Creating Information Beats Reading It

Explore how the generation effect enhances memory retention by encouraging students to create information, supported by cognitive science research and.

Explore how the generation effect enhances memory retention by encouraging students to create information, supported by cognitive science research and.

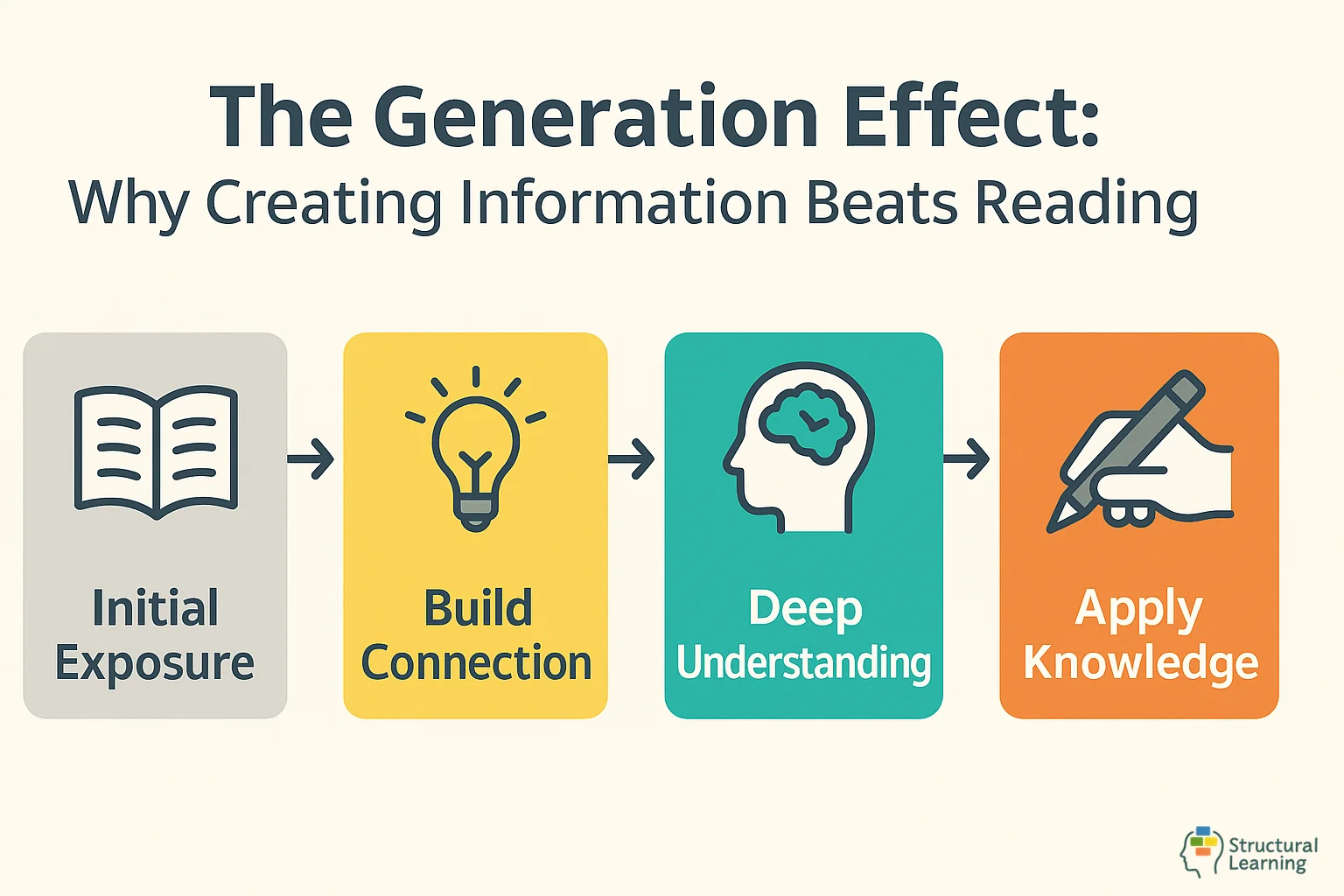

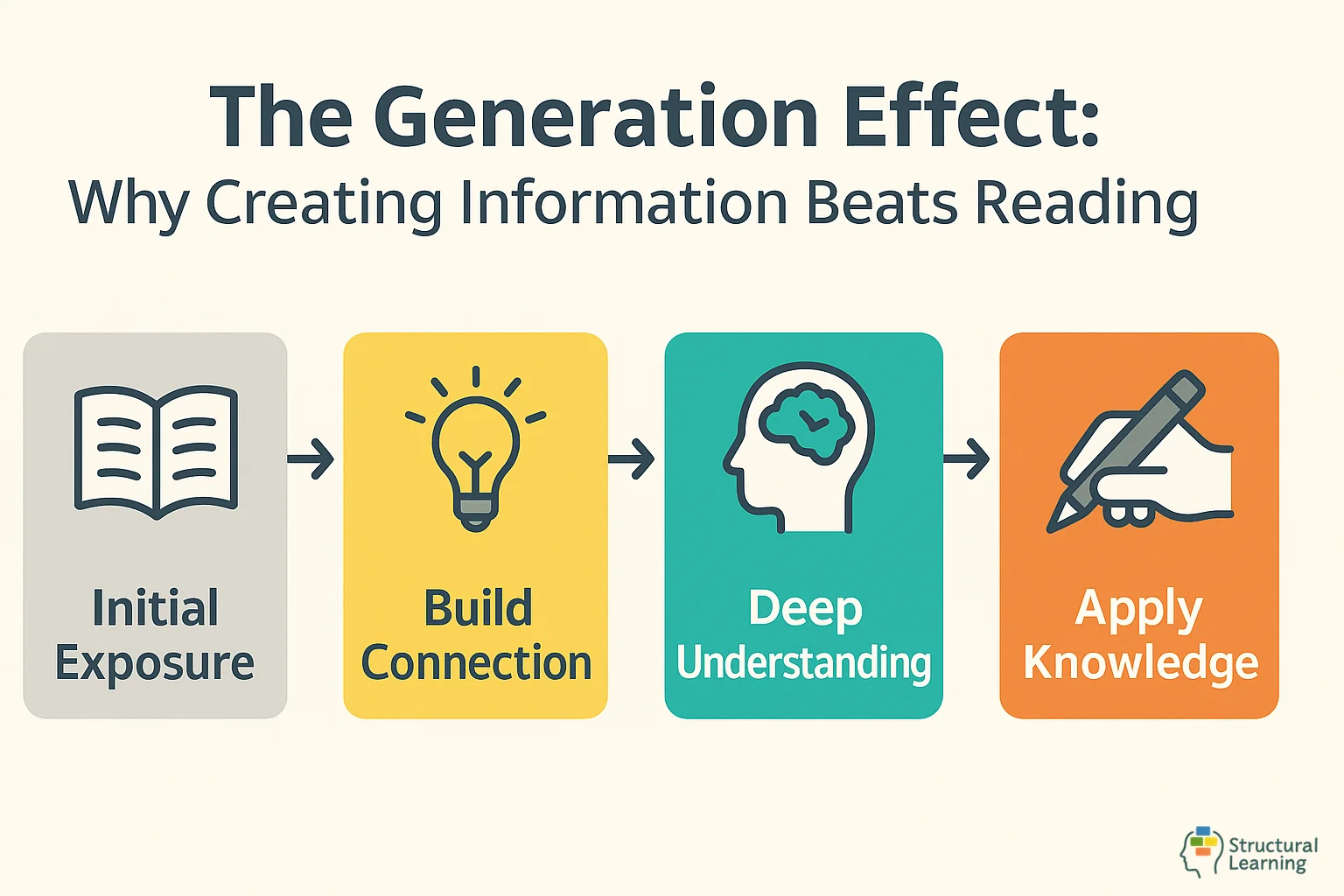

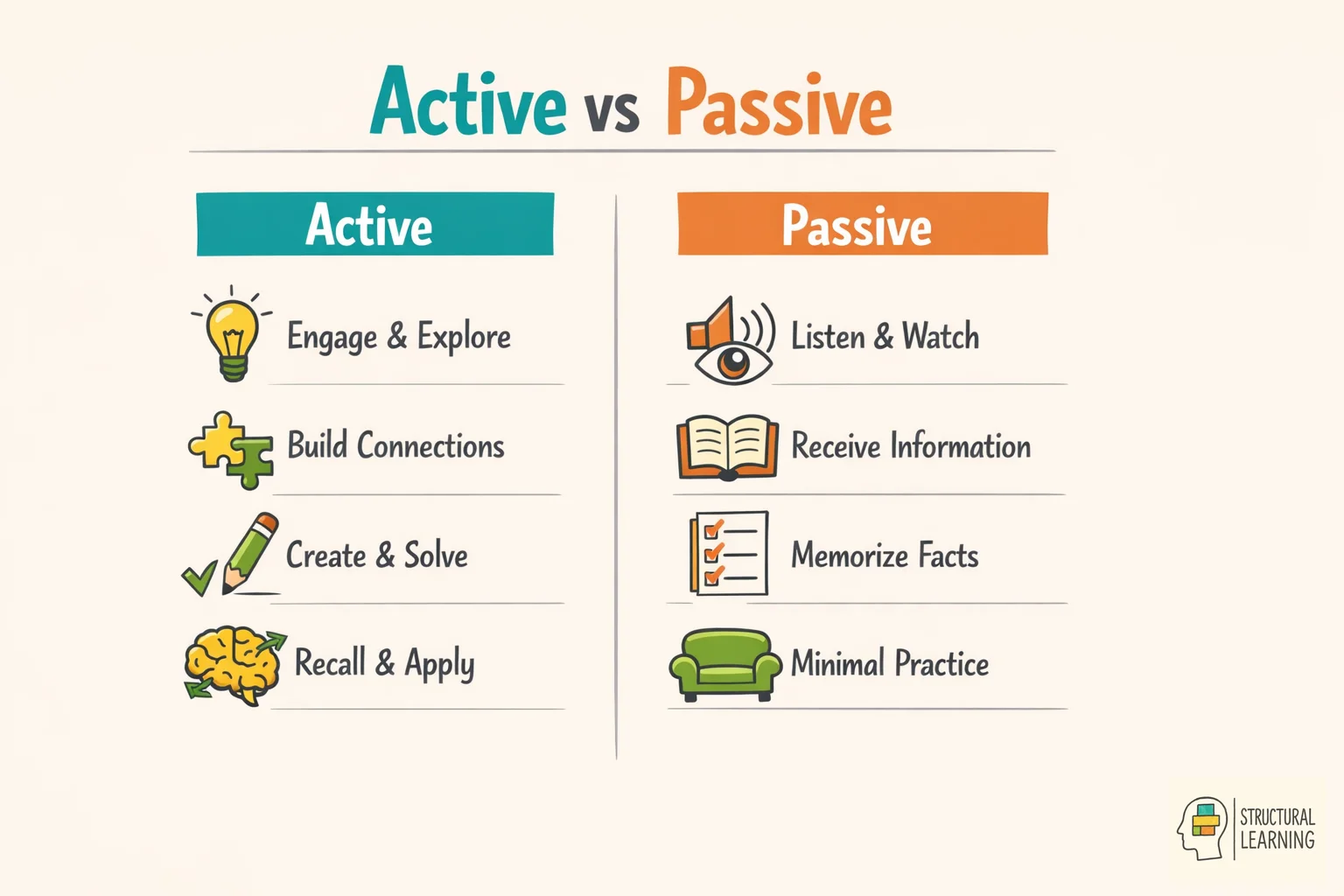

The generation effect is a powerful learning phenomenon where information you create yourself becomes far more memorable than information you simply read. This cognitive principle explains why actively generating answers, definitions, or examples leads to stronger memory retention than passive study methods like highlighting or re-reading notes. When your brain works to produce information rather than just consume it, it forms deeper neural pathways that make recall significantly easier. Understanding how to harness this effect could transform the way you learn and remember everything from vocabulary to complex concepts.

Decades of research point decisively to the second student. The generation effect describes one of memory science's most reliable findings: information that learners generate themselves is remembered better than information they simply read or receive. This phenomenon has profound implications for how we structure learning experiences in classrooms.

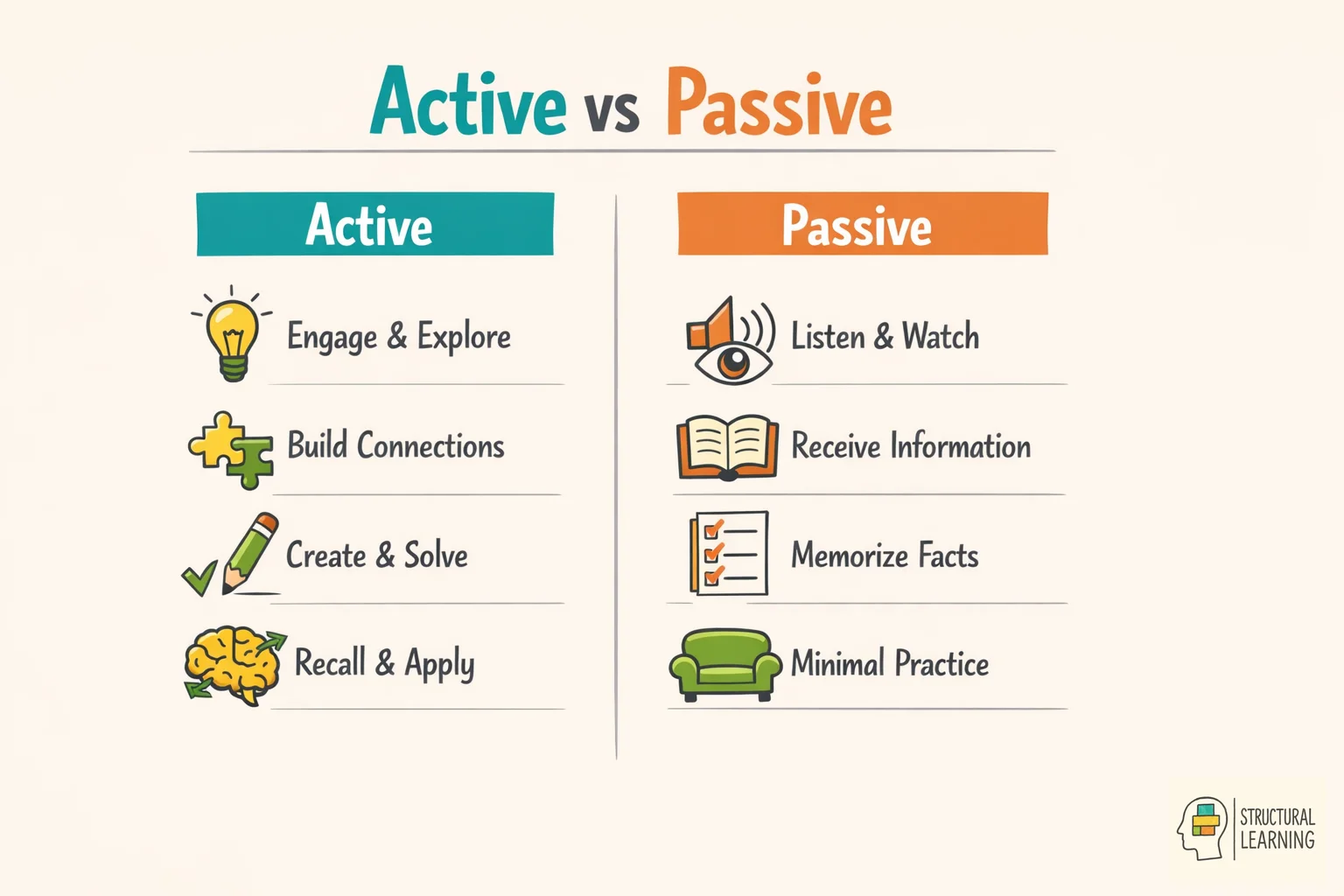

When students actively produce responses, complete word stems, solve problems without worked examples, or explain concepts in their own words, they create stronger, more durable memories than when they passively consume the same information. Understanding why this happens, and how to apply it practically, offers teachers a powerful lever for improving long-term retention.

Self-generated information is remembered substantially better retention (effect size d = 0.40)than read information because generation requires deeper cognitive processing. The effect works through activemental engagement, forcing learners to retrieve and construct knowledge rather than passively receive it. Teachers can apply this through fill-in-the-blank activities, self-explanation exercises, and problem generation tasks.

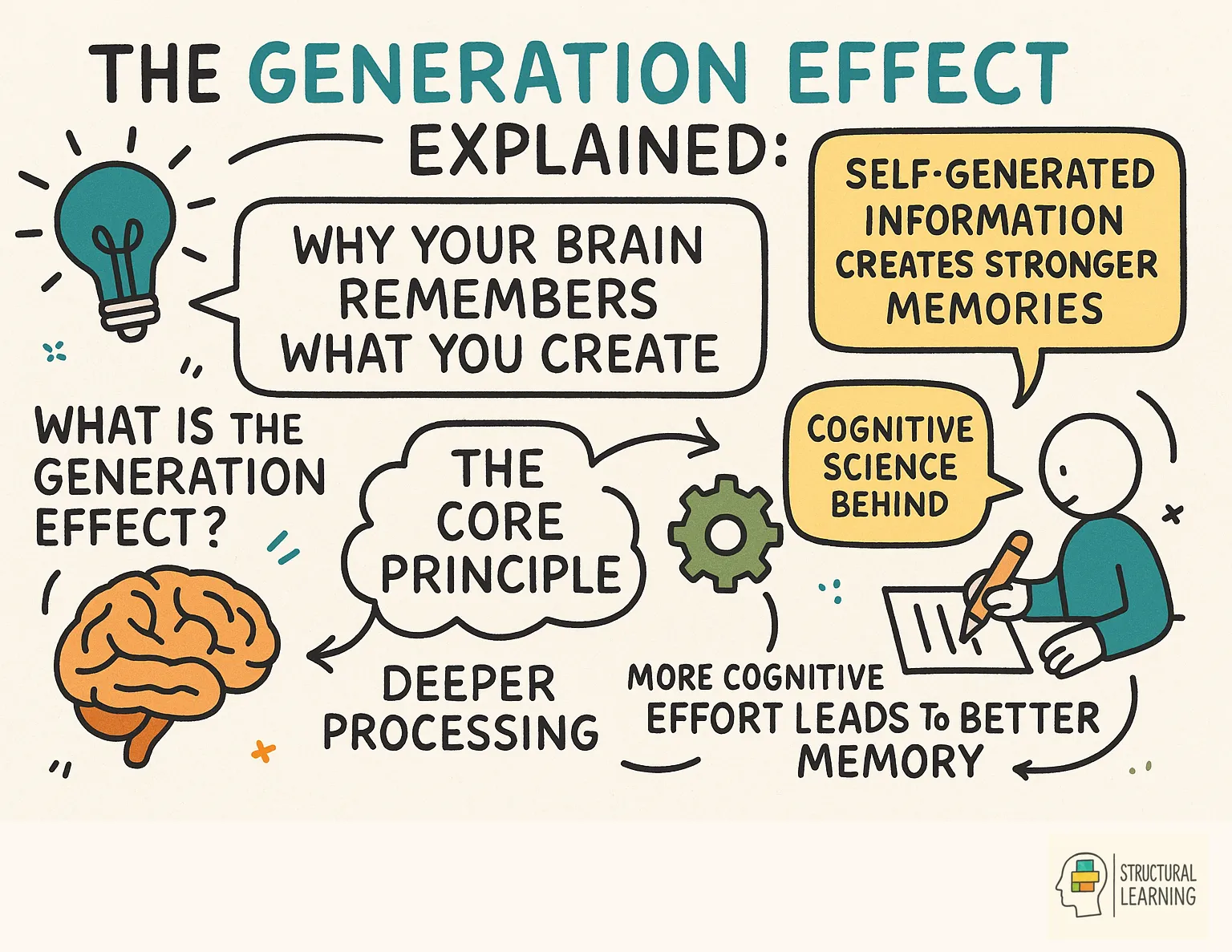

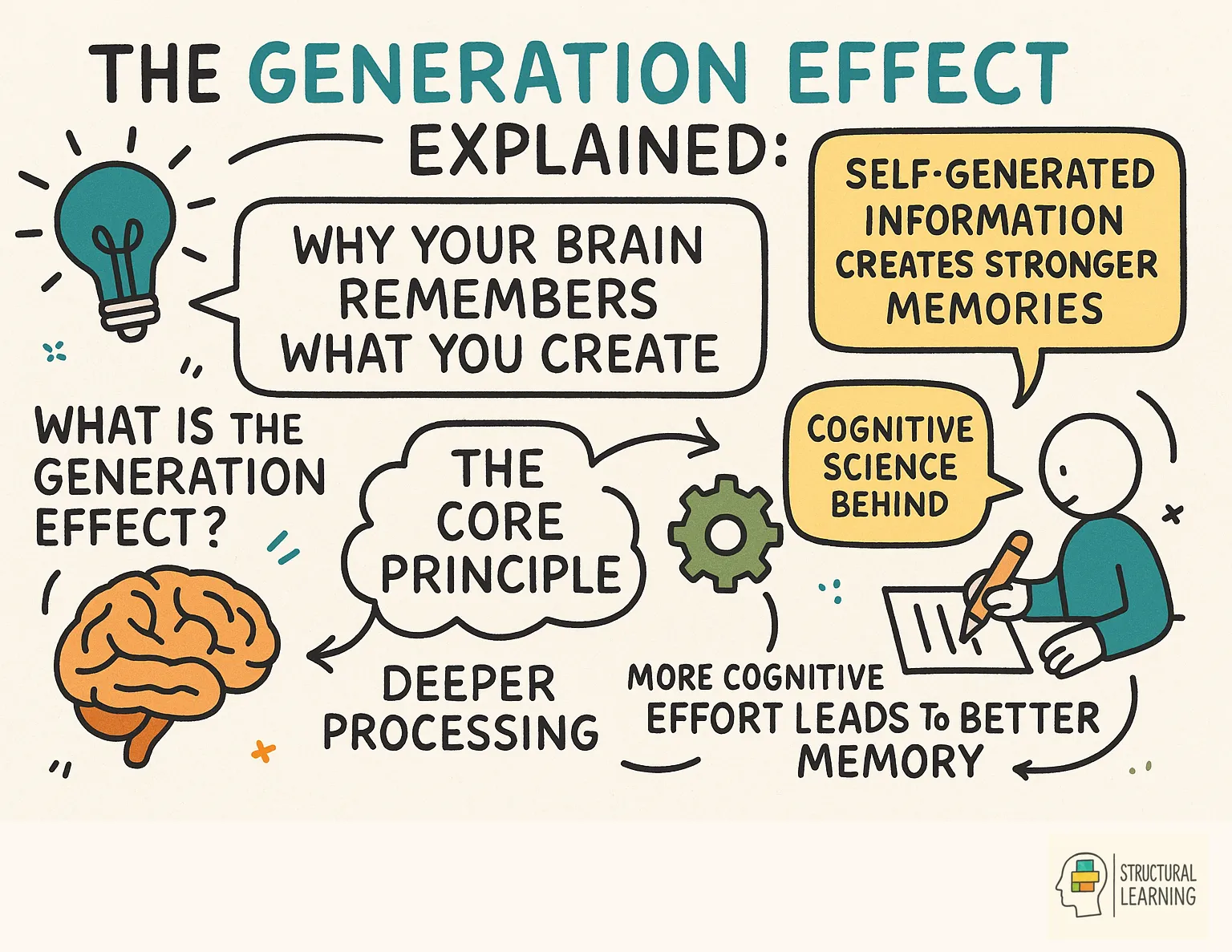

The generation effect refers to the memory advantage for information that is actively generated compared to information that is passively received. Norman Slamecka and Peter Graf first documented this phenomenon systematically in 1978, though teachers have intuitively understood its power for centuries.

In their classic experiments, Slamecka and Graf presented participants with word pairs. Some participants read complete pairs (KING-CROWN). Others generated the second word from a cue (KING-CR___). When tested later, participants consistently remembered generated words better than read words, even though both groups spent equal time with the material.

A meta-analysis by Bertsch and colleagues examining 86 studies found an average effect size of 0.40, meaning generated information was remembered about half a standard deviation better than read information. This represents a substantial, reliable advantage that has been replicated across diverse materials, age groups, and learning contexts.

The generation effect connects to broader research on active learning. Whenever students transform, manipulate, or produce information rather than simply receiving it, they engage cognitive processes that strengthen memory formation.

Generation improves memory because it activates multiple cognitive processes including semantic elaboration, distinctive processing, and effortful retrieval. When students generate information, they must search their memory, make connections to existing knowledge, and actively construct responses. This deeper processing creates more retrieval pathways and stronger memory traces than passive reading.

| Technique | Description | Cognitive Benefit | Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-explanation | Explain while learning | Deeper processing | Think-aloud protocols |

| Question generation | Create own questions | Metacognitive awareness | Question stems provided |

| Summary writing | Condense information | Identify key points | Structured templates |

| Elaborative interrogation | Ask why and how | Connect to prior knowledge | Guided prompts |

| Teaching others | Explain to peers | Organisation and retrieval | Peer tutoring |

Understanding why generation works helps teachers design more effective learning activities. Several cognitive mechanisms contribute to the generation advantage.

Generating information requires accessing meaning and making connections. When you complete the stem "The powerhouse of the cell is the MITO___," you must search your memory for information about cells and their components. This deep, meaning-based processing creates richer memory traces than shallow reading.

Craik and Lockhart's levels of processing framework explains this pattern. Shallow processing, focusing on surface features like how a word looks, produces weak memories. Deep processing, engaging with meaning and connections, produces strong memories. Generation inherently demands deep processing.

Generated items stand out in memory because they involve unique cognitive operations. The effort of producing a response creates distinctive episodic features that differentiate generated items from other memories. This distinctiveness makes generated information easier to retrieve later.

Generation requires searching memory and selecting appropriate responses. These processes strengthen retrieval pathways, making future access more reliable. The neural pathways activated during generation become the same routes used during later retrieval, creating well-practised access patterns.

Generated responses carry a sense of ownership that read material lacks. When students create their own explanations or examples, they invest cognitive effort that produces personal significance. This investment may activate emotional and motivational systems that support memory consolidation.

Research consistently shows that generated information is remembered 40-substantially retention was better (effect size d = 0.40) than read information across various contexts and time delays. Studies spanning four decades demonstrate this advantage holds for different types of content, from vocabulary words to scientific concepts. The effect is strongest when learners generate meaningful connections rather than surface-level responses.

The generation effect has been demonstrated across numerous experimental paradigms, establishing its robustness as a learning principle.

The original generation studies used word pairs, and vocabulary learning remains an excellent application. Students who generate translations or definitions remember words better than those who simply review word lists. This has particular relevance for vocabulary instruction in both first and additional languages.

Students who solve problems themselves retain mathematical procedures better than those who study worked examples exclusively. This doesn't mean worked examples aren't valuable; they are, especially for novice learners. But transitioning to problem generation as competence develops produces stronger learning.

Completing sentences, filling in missing words, and generating answers to questions produces better memory for factual content than reading complete sentences. Any prompt that requires students to produce the target information creates the generation advantage.

Generation benefits extend beyond factual recall to conceptual understanding. Students who generate explanations of scientific phenomena understand them better than students who read explanations. Self-explanation, where students explain material to themselves, produces learning beyond what reading alone achieves.

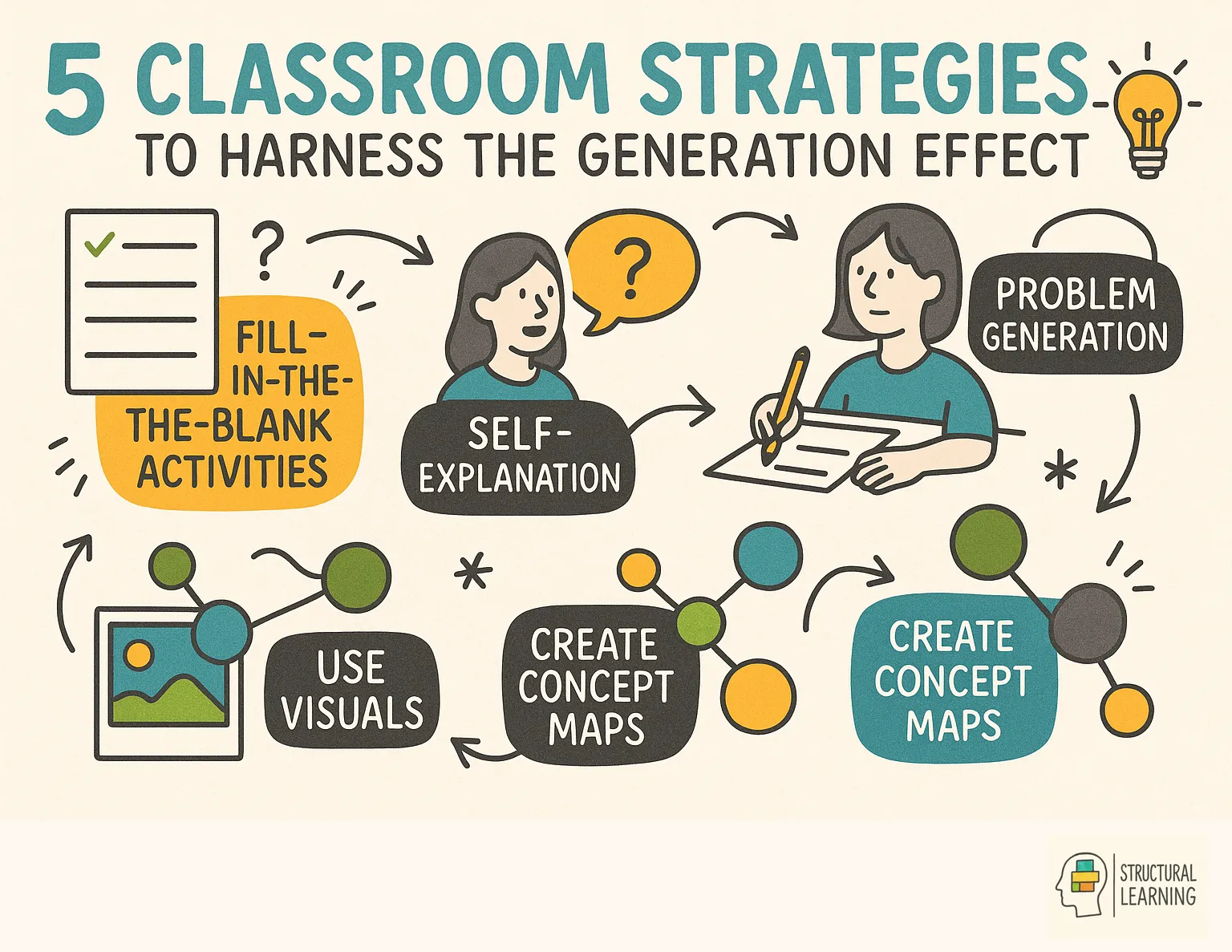

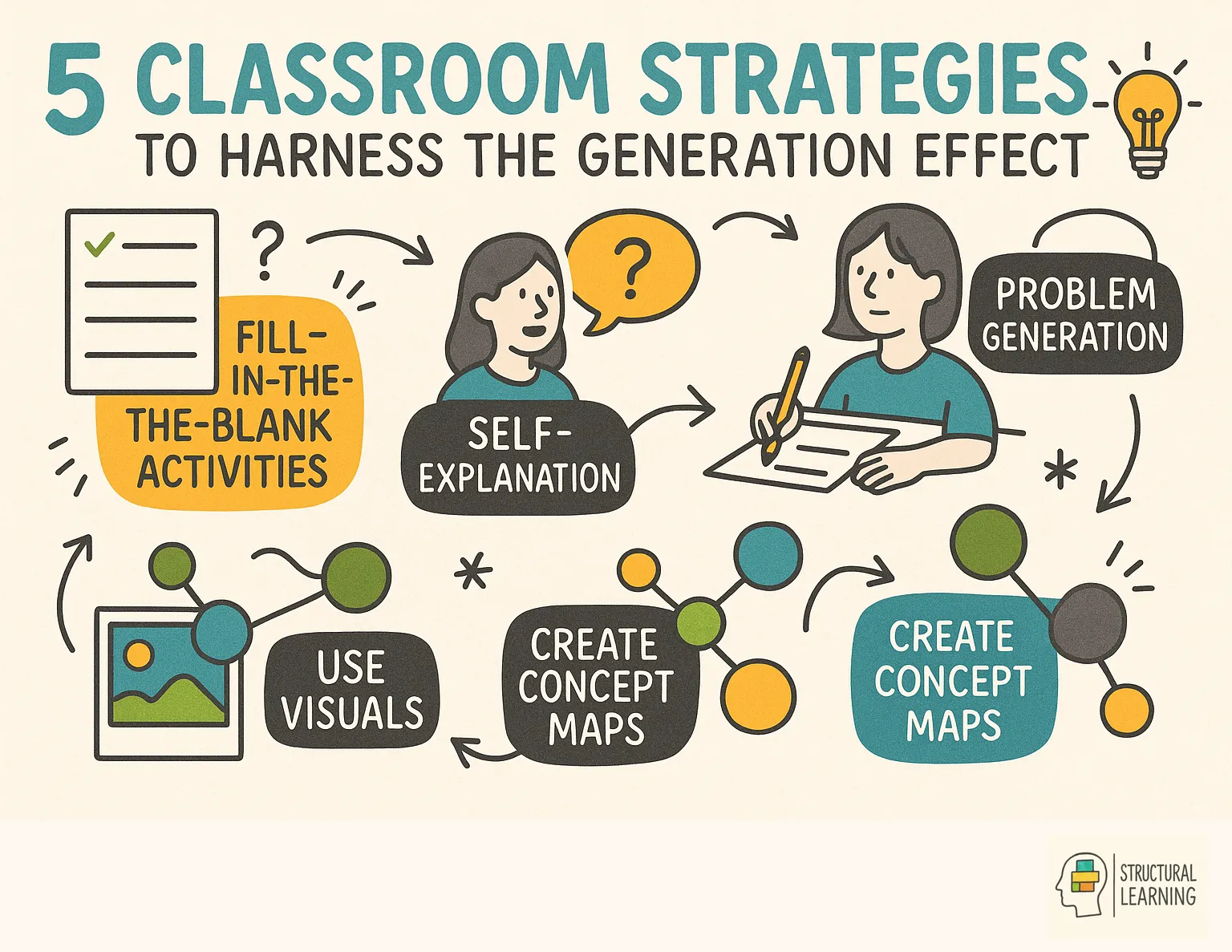

Effective generation activities include cloze exercises where students fill in missing keywords, self-explanation prompts requiring students to explain concepts in their own words, and problem posing where students create their own practise questions. Other powerful techniques include concept mapping from memory, teaching peers without notes, and generating examples of principles. These activities work best when followed by immediate AI-enhanced feedback to correct any errors.

The generation effect translates into numerous practical classroom activities.

Converting information into completion tasks creates generation opportunities. Rather than providing complete notes, leave strategic blanks for students to complete. The missing information should be conceptually important rather than trivial.

For example, instead of providing the note "Photosynthesis uses carbon dioxide and water to produce glucose and oxygen," present "Photosynthesis uses _____ and _____ to produce _____ and _____." Students who generate the missing terms remember them better than those who read the complete statement.

Ask students elucidating concepts words rather than simply reading explanations. Prompts like "Why does this work?" or "How would you explain this to someone who doesn't understand?" require generation of explanations.

Self-explanation works particularly well for procedural knowledge. Students who explain why each step in a procedure works understand and remember the procedure better than those who simply follow steps without explanation.

Having students create problems, rather than just solve them, requires deep understanding of the problem type. A student who can generate a word problem about fractions demonstrates, and strengthens, their understanding of how fractions work in real contexts.

Problem generation also produces excellent formative assessment data. The problems students create reveal what they understand about the structure of a topic.

Students who generate questions about content process it more deeply than those who simply read it. After presenting new material, ask students to generate questions that test understanding. This requires them to identify key concepts and think about what would demonstrate comprehension.

Question generation supports metacognitionby focusing attention on what's important and what might be confusing. Students develop question-asking skills that serve them well in independent learning.

Writing summaries requires identifying key ideas and expressing them in one's own words. Both aspects involve generation. Effective summaries can't simply reproduce original text; they require transformation and synthesis.

Scaffold summary generation by providing structure initially. Ask for three key points, a one-sentence summary, or a summary using specific vocabulary. Gradually release responsibility as students develop summarising skills.

Asking "Why?" questions prompts students to generate explanations. Why is this true? Why does this happen? Why is this important? These questions require connecting new information to existing knowledge and producing explanatory responses.

Elaborative interrogation works especially well when students have relevant prior knowledge to draw upon. The act of generating connections strengthens both the new information and the prior knowledge it connects to.

Generation works synergistically with spaced practise, interleaving, and retrieval practise to maximise learning. Teachers can space generation activities across multiple lessons, interleave different types of generation tasks, and use generation as a form of retrieval practise. Combining generation with elaborative interrogation (asking 'why' questions) creates particularly strong learning outcomes.

Generation becomes even more powerful when combined with other evidence-based learning strategies.

Generation and retrieval practise share features but aren't identical. Retrieval practise involves recalling previously learned information; generation involves producing information during initial learning. Both strengthen memory through active processing.

Combining the two creates particularly durable learning. After initial generation activities, follow up with retrieval practise that requires recalling generated information. This double dose of active processing compounds the benefits.

Spacing generation activities over time provides multiple processing opportunities while allowing memory consolidation between sessions. Generate explanations today, retrieve them tomorrow, elaborate on them next week.

This combination aligns with spaced practise research showing that distributed practise produces more durable learning than massed practise. Each spaced generation opportunity strengthens memory more than equivalent massed practise.

When practising multiple topics, generating mixed practise sessions supports discrimination learning. Students must generate the appropriate strategy for each problem type, not just execute a familiar procedure.

This combination of generation with interleaving supports both retention and discrimination.

Following generation with elaborative processing amplifies benefits. After students generate an initial response, prompting them to explain why that response is correct or how it connects to other knowledge deepens understanding.

In mathematics, students generate problem-solving steps or create their own word problems; in science, they predict experimental outcomes or generate hypotheses; in language arts, they complete story frameworks or generate thesis statements. History teachers can have students generate timelines from memory or create cause-effect relationships between events. Each subject requires adapting generation activities to match its specific content and thinking patterns.

The generation effect applies across the curriculum, though implementation varies by subject.

For reading comprehension, generation activities before, during, and after reading strengthen understanding and memory for content.

The generation effect supports both procedural fluency and conceptual understanding in mathematics.

Science teaching benefits particularly from generation that connects observations to underlying mechanisms and explanations.

Historical thinking involves generating interpretations and explanations, making the generation effect particularly relevant.

The main challenges include students generating incorrect information, the time-intensive nature of generation activities, and resistance from students accustomed to passive learning. Teachers can address these by providing scaffoldinginitially, giving immediate corrective feedback, and gradually increasing the difficulty of generation tasks. Starting with partial generation (like sentence stems) helps build student confidence before moving to full generation.

Teachers sometimes hesitate to implement generation-focused activities. Addressing common concerns helps overcome barriers to adoption.

Scaffold generation appropriately. Start with easier generation tasks and increase difficulty as competence develops. Provide partial information, offer choices, or allow collaboration initially. Frame generation as a learning tool where difficulty is expected and valuable.

The productive struggle of generation is part of what makes it effective. But struggle should be productive, not overwhelming. Adjust difficulty to maintain challenge without causing despair.

Time spent generating produces more learning per minute than time spent receiving instruction passively. The apparent efficiency of direct instruction is often illusory if students don't retain the information. Generation activities constitute high-yield uses of instructional time.

Consider which is more efficient: teaching something once with generation activities that produce retention, or teaching something three times because passive reception didn't stick?

All students benefit from generation, though activities must be appropriately scaffolded. Provide more support for struggling learners through partial completions, cued generation, or collaborative generation. The benefits of generation are often largest for students who would otherwise engage in passive processing.

Scaffolding is key. Reduce the generation demand to a level that challenges but doesn't overwhelm, then gradually increase expectations.

Errors followed by feedback are not harmful and may enhance learning. The key is providing timely correction. Generate-then-feedback sequences help students identify and correct misconceptions.

Research on the hypercorrection effect shows that confidently held errors that are corrected are remembered especially well. Generation that produces errors, followed by correction, can be more powerful than error-free passive learning.

Generation enhances metacognition by making students more aware of what they know and don't know through immediate feedb ack from their attempts. When students try to generate information and struggle, they recognise knowledge gaps more clearly than when passively reading. This awareness helps students regulate their study time more effectively and seek help for specific areas of difficulty.

Generation activities support metacognitive development by revealing what students actually know versus what they think theyknow. When required to generate, students discover gaps in their understanding that passive review would miss.

This metacognitive benefit has two components. First, generation reveals actual knowledge state, providing accurate self-assessment. Second, students can use this information to target gaps identified through generation, improving study decisions.

Students who experience the generation effect directly often spontaneously adopt generation-based study strategies. Teaching students about the generation effect explicitly supports this transfer to independent learning.

The generation effect works across all age groups but manifests differently: elementary students benefit from simple fill-in activities and generating examples, while secondary students can handle more complex generation like creating analogies or explanations. Research shows the effect is strong from age 7 through adulthood, though younger students need more scaffolding and shorter generation tasks. The key is matching generation difficulty to students' cognitive development and prior knowledge.

The generation effect has been demonstrated across the lifespan, from young children to older adults.

Younger children benefit from generation but may need more scaffolding. Simple completion tasks, paired generation activities, and verbal rather than written generation work well. Games that require generating answers rather than selecting from options use the effect playfully.

Adolescents can engage in more complex generation tasks including extended explanations, problem creation, and metacognitive reflection on their generation performance. The self-testing applications of generation become increasingly relevant as students prepare for examinations.

The generation effect remains strong in adult learning contexts. Professional development, workplace training, and self-directed study all benefit from generation-focused approaches. Adults can be taught the generation effect explicitly and encouraged to incorporate generation into their learning strategies.

Brain imaging studies show generation activates the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex more strongly than passive reading, indicating deeper memory encoding and executive processing. The effort required to generate information triggers the release of neurotransmitters that strengthen synaptic connections. This increased neural activity creates more distinctive memory traces that are easier to retrieve later.

Brain imaging studies reveal that generation engages different neural networks than reading. During generation, prefrontal regions associated with executive function and strategic retrieval show increased activation. Medial temporal lobe structures involved in memory formation are more active during generation than passive reading.

These neural differences help explain why generated information is remembered better. Generation engages the brain systems most important for memory formation more intensively than passive reading.

The additional neural activity during generation may also explain why generation feels more effortful than reading. This subjective difficulty is a signal that learning is occurring, not a sign that something is wrong.

Teachers should start by identifying key concepts that need long-term retention, then design generation activities that target these concepts through partial completion tasks, self-testing, or student-created examples. Implementation works best when introduced gradually, starting with 10-15% of class time devoted to generation activities and increasing as students become comfortable. Regular cycles of generation, feedback, and re-generation improve the learning benefits.

The generation effect offers teachers a straightforward principle: whenever possible, have students produce information rather than receive it. This doesn't mean eliminating direct instruction, which remains essential for introducing new concepts. Rather, it means following instruction with generation opportunities.

Practical implementation might begin with:

Small changes accumulate into significant learning benefits. Each generation opportunity strengthens memory more than equivalent passive review. Over time, embedding generation throughout instruction produces substantially more durable learning.

Essential readings include Slamecka and Graf's 1978 foundational paper establishing the effect, Bertsch et al.'s 2007 meta-analysis quantifying its strength, and Foos et al.'s 1994 work on classroom applications. McNamara and Healy's research on generation in skill learning and deWinstanley and Bjork's work on generation combined with other techniques provide practical implementation guidance. These papers offer evidence-based strategies teachers can adapt for their specific contexts.

These papers provide deeper exploration of the generation effect and its educational applications.

The foundational paper establishing the generation effect as a strong memory phenomenon. Through five experiments, Slamecka and Graf demonstrated that self-generated words are consistently remembered better than read words across various generation tasks and test formats. This research launched decades of subsequent investigation.

This comprehensive meta-analysis synthesised findings from 86 studies examining the generation effect. The analysis confirmed a medium-to-large effect size and identified moderating factors including generation task type, test format, and retention interval. Essential reading for understanding the scope and boundaries of generation effects.

Michelene Chi's work on self-explanation demonstrates how generating explanations produces learning beyond what reading achieves. The paper distinguishes between self-explanation that fills gaps in understanding and self-explanation that repairs misconceptions, both of which benefit from the generation process.

This early application of the generation effect to educational contexts explored how generating responses during learning improves memory for prose passages. The research established that generation benefits extend beyond word pairs to more complex educational materials.

This paper extends generation research to show that even unsuccessful attempts to generate answers enhance subsequent learning. Testing students before teaching, even when they get answers wrong, produces better final learning than teaching without pretesting.

When students generate information rather than simply reading it, their brains activate in fundamentally different ways. Neuroimaging studies reveal that self-generation lights up multiple brain regions simultaneously: the hippocampus for memory formation, the prefrontal cortex for executive control, and critically, the semantic networks that connect new information to existing knowledge.

This multi-region activation creates what neuroscientists call "distinctive processing." Unlike passive reading, which primarily engages visual processing areas, generation forces the brain to reconstruct information actively. This reconstruction process strengthens synaptic connections through a mechanism called long-term potentiation, essentially creating more strong neural pathways for later retrieval.

The effort required during generation also triggers the release of neurotransmitters like dopamine and norepinephrine, which enhance memory consolidation. This explains why struggling to recall an answer, even unsuccessfully, improves later retention more than being given the answer immediately.

In practise, teachers can harness these mechanisms through simple adjustments. Instead of providing complete worked examples in maths, show the first two steps and have students generate the remaining solution. During history lessons, rather than listing all causes of an event, provide two causes and ask students to generate a third. In science, present an incomplete diagram of the water cycle and have students fill in missing stages from memory.

These generation activities work because they force the brain into active reconstruction mode, creating memories that are both more distinctive and more deeply integrated into existing knowledge networks. The temporary difficulty students experience isn't a barrier to learning; it's the very mechanism that makes the learning stick.

Transforming the generation effect from theory to practise requires deliberate changes to how we structure learning activities. Rather than presenting complete information, teachers can create opportunities for students to actively produce knowledge throughout lessons.

One powerful technique is the completion task, where students fill in missing components rather than copying complete examples. In a Year 7 science lesson on photosynthesis, instead of providing the full equation, present: "6CO₂ + 6H₂O → _______ + 6O₂" and have students generate the missing glucose formula. Research by Jacoby (1978) showed that words completed from fragments are remembered 20-30% better than words simply read.

Self-explanation prompts offer another practical approach. After teaching a mathematical concept, ask students to write explanations of solved problems in their own words before attempting practise questions. A maths teacher might display a completed factorisation problem and ask: "Explain to your partner why we chose these factors." This generation of explanations strengthens understanding more effectively than reviewing worked examples alone.

Testing as generation provides particularly strong benefits. Replace revision handouts with retrieval practise sheets where students generate answers from memory. Create question stems that require completion: "The Battle of Hastings occurred in _______" rather than "When did the Battle of Hastings occur?" This subtle shift engages generation processes that enhance retention.

Implementation requires patience; students initially find generation tasks more challenging than passive reading. However, this desirable difficulty signals deeper processing at work. Start with partially completed examples, gradually increasing the generation demands as students build confidence. The initial struggle yields superior long-term retention, making the extra effort worthwhile for both teachers and learners.

Whilst the generation effect is remarkably strong, it doesn't work universally. Understanding its boundaries helps teachers apply it more effectively and avoid frustration when certain activities fall flat.

The most significant limitation occurs with complex, unfamiliar material. When students lack sufficient background knowledge, generation activities can overwhelm working memory rather than strengthen it. For instance, asking Year 7 students to generate explanations for photosynthesis before they understand basic plant biology often leads to confusion, not clarity. Research by Kang and colleagues (2007) found that generation only benefits learning when students possess adequate prior knowledge to draw upon.

Timing matters crucially. Immediate testing shows strong generation effects, but these advantages can diminish over longer intervals if students generate incorrect responses initially. A student who incorrectly fills in "osmosis" when the answer is "diffusion" may strengthen the wrong association, particularly without immediate corrective feedback.

The effect also weakens with certain types of content. Arbitrary associations, such as foreign language vocabulary with no etymological connections, show smaller benefits from generation. Similarly, precise procedural sequences, like the steps in long division, may actually suffer when students generate incomplete or disordered steps.

Teachers should consider three practical adjustments. First, provide worked examples before generation tasks with novel content; students need a foundation before they can build effectively. Second, ensure immediate feedback for generation activities, particularly in subjects where precision matters. Third, match the generation difficulty to student expertise; beginners benefit from completing partial solutions whilst advanced students thrive when generating entire responses from scratch.

Recognising these limitations doesn't diminish the generation effect's value. Rather, it helps teachers deploy this powerful tool more strategically, knowing when to guide students actively and when to step back and let them create.

In 1978, cognitive psychologists Norman Slamecka and Peter Graf stumbled upon a finding that would reshape our understanding of memory formation. Their experiment was deceptively simple: one group of students read word pairs like 'hot-cold', whilst another group had to complete word stems like 'hot-c___'. When tested later, the students who generated the word 'cold' themselves remembered significantly more pairs than those who simply read them. This straightforward discovery revealed something profound about how our brains encode information.

The implications rippled through educational psychology. Researchers began testing the effect across different contexts, from foreign language learning to mathematical problem-solving. Time after time, the results held firm: whether students were generating synonyms, solving equations, or creating their own examples, the act of production consistently outperformed passive reception. Studies showed retention rates improving by 30-50% when learners generated content rather than consuming pre-made materials.

For teachers, this research offered a clear directive: stop doing all the work for your students. Instead of providing complete notes, leave strategic gaps for pupils to fill. Rather than showing fully worked examples, present problems halfway through and ask students to complete them. When teaching vocabulary, give definitions and ask students to generate the terms, or provide terms and have them create definitions. These simple adjustments activate the generation effect without requiring wholesale changes to your teaching approach.

The most striking aspect of Slamecka and Graf's discovery was its universality. The generation effect works across ages, subjects, and ability levels. Whether you're teaching Year 2 pupils their times tables or A-level students complex chemical equations, the principle remains constant: what students create, they remember.

When you generate information, your brain activates multiple processing systems simultaneously. Unlike passive reading, which primarily engages recognition networks, creating content fires up retrieval pathways, semantic processing regions, and executive control centres. This multi-system activation explains why pupils who write their own definitions remember vocabulary at nearly double the rate of those who copy from textbooks.

The cognitive effort required to produce information strengthens memory through what researchers call 'desirable difficulty'. Your brain must search through existing knowledge, make connections, and construct new understanding; this struggle creates distinctive memory traces. For instance, when pupils generate their own examples of metaphors rather than studying provided ones, they activate personal experiences and emotions that serve as powerful retrieval cues later.

Brain imaging studies reveal that generation tasks light up the hippocampus, the brain's memory consolidation centre, far more intensely than reading activities. This increased neural activity translates directly to classroom results. Teachers who replace traditional copying exercises with sentence completion tasks, where pupils must generate missing keywords, report 30-40% better retention on end-of-unit assessments.

The prefrontal cortex, responsible for planning and organising thoughts, shows heightened engagement during generation activities. This explains why pupils who create their own study questions before reading a text comprehend and remember content more effectively than those given pre-made questions. The act of formulating questions requires deeper processing of material relationships and significance, creating what cognitive scientists term 'elaborative encoding', the gold standard for durable learning.

Transform your existing resources into generation-based activities with minimal preparation time. Instead of providing complete notes, give students partial information with strategic gaps. For instance, when teaching photosynthesis, provide the equation with missing components: 6CO₂ + ____ → C₆H₁₂O₆ + 6O₂. Students must recall and insert '6H₂O', creating stronger memories than copying the complete equation. This simple modification takes seconds but significantly improves retention.

Replace traditional vocabulary lists with word-stem completion exercises. Rather than presenting 'metamorphosis: a complete change in form', show 'meta_____: a complete change in form'. Students generating 'morphosis' engage deeper cognitive processing than those who simply read the full term. Research by Slamecka and Graf (1978) found this technique improved recall by up to 40% compared to passive reading, particularly effective for science terminology and foreign language vocabulary.

Turn review sessions into active generation opportunities using the 'test-enhanced learning' approach. Begin lessons by asking students to write everything they remember about the previous topic before checking their notes. This retrieval practise, even when incomplete or incorrect, strengthens memory pathways more effectively than re-reading perfect notes. Year 7 students using this method in history lessons showed 35% better retention after one week compared to those who reviewed by reading.

Create 'explanation challenges' where students must teach concepts to partners using only keywords as prompts. Provide five key terms related to the water cycle, then have students generate complete explanations connecting these concepts. This approach combines the generation effect with elaborative processing, making it particularly powerful for complex topics across all subject areas.

The generation effect is the memory advantage that occurs when learners actively generate information themselves rather than passively reading it. Research shows that self-generated information is remembered substantially outperforming retention (effect size d = 0.40) in comparison to read information because it requires deeper cognitive processing. This gives teachers a powerful, evidence-based strategy to improve long-term retention in their classrooms.

Teachers can use fill-in-the-blank exercises where students complete missing keywords, self-explanation prompts requiring students articulating concepts in their own words words, and problem-posing activities where students create practise questions. Other effective techniques include concept mapping from memory, peer teaching without notes, and having students generate their own examples of principles being taught.

Generation improves memory through several mechanisms: it requires deeper semantic processing as students must search memory and make connections, it creates enhanced distinctiveness making information stand out, and it strengthens retrieval pathways. Additionally, generated responses carry a sense of personal investment that activates emotional and motivational systems supporting memory consolidation.

Yes, research spanning four decades shows the generation effect works across diverse content types including vocabulary words, mathematical problems, factual knowledge, and conceptual understanding. The effect is particularly strong for vocabulary learning, mathematical procedures, and scientific concepts. However, it works best when learners generate meaningful connections rather than surface-level responses.

The main challenge is ensuring students receive immediate feedback to correct any errors in their generated responses, as incorrect generation can reinforce misconceptions. Teachers also need to consider that generation activities work best when students have some foundational knowledge, so complete beginners may benefit from worked examples before transitioning to generation tasks.

The article illustrates this with two students: one who repeatedly reads and highlights notes, and another who covers notes and writes definitions from memory before checking. Decades of research consistently favour the second approach, showing that active generation produces substantially better retention than passive reading or highlighting.

Instead of providing complete notes, create strategic blanks for students to fill in with conceptually important information. Rather than showing worked mathematical examples, have students solve problems themselves after initial instruction. Transform reading comprehension by having students explain concepts in their own words instead of simply reading provided explanations.

These peer-reviewed studies provide the research foundation for the strategies discussed in this article:

A controlled study of team-based learning for undergraduate clinical neurology education View study ↗

118 citations

N. Tan et al. (2011)

This study compared team-based learning with traditional passive lectures in medical education and found that active, collaborative learning significantly improved students' understanding of complex neurology topics. The research demonstrates that when students work together to solve problems and generate solutions rather than simply listening to lectures, they develop deeper knowledge and better retention. For educators, this provides strong evidence that shifting from lecture-heavy teaching to interactive group work can dramatically improve learning outcomes, even in highly technical subjects.

Artificial intelligence and medical education: application in classroom instruction and student assessment using a pharmacology & therapeutics case study View study ↗

43 citations

K. Sridharan & Reginald P Sequeira (2024)

Researchers explored how AI tools could transform medical education by having students actively engage with artificial intelligence to create learning materials and assessments rather than passively consuming pre-made content. The study shows that when students use AI as a collaborative partner to generate their own educational resources, they develop stronger critical thinking skills and deeper subject mastery. This research offers teachers a roadmap for integrating AI tools in ways that enhance student creativity and engagement rather than replacing human learning.

Exploring the Multidimensional Advantages of Productive Failure in Cultivating Clinical Thinking, Collaboration, Stress Management, and Learning Retention in Resident Physicians View study ↗

Yingjie Ding et al. (2025)

This research examined 'productive failure,' a teaching method where medical residents tackle challenging problems before receiving formal instruction, allowing them to struggle and generate their own solutions first. The study revealed that this approach not only improved clinical knowledge retention but also enhanced collaboration skills and stress management abilities. For educators across all subjects, this research supports the counterintuitive idea that letting students wrestle with difficult concepts before providing guidance can lead to deeper learning and greater resilience.

The generation effect is a powerful learning phenomenon where information you create yourself becomes far more memorable than information you simply read. This cognitive principle explains why actively generating answers, definitions, or examples leads to stronger memory retention than passive study methods like highlighting or re-reading notes. When your brain works to produce information rather than just consume it, it forms deeper neural pathways that make recall significantly easier. Understanding how to harness this effect could transform the way you learn and remember everything from vocabulary to complex concepts.

Decades of research point decisively to the second student. The generation effect describes one of memory science's most reliable findings: information that learners generate themselves is remembered better than information they simply read or receive. This phenomenon has profound implications for how we structure learning experiences in classrooms.

When students actively produce responses, complete word stems, solve problems without worked examples, or explain concepts in their own words, they create stronger, more durable memories than when they passively consume the same information. Understanding why this happens, and how to apply it practically, offers teachers a powerful lever for improving long-term retention.

Self-generated information is remembered substantially better retention (effect size d = 0.40)than read information because generation requires deeper cognitive processing. The effect works through activemental engagement, forcing learners to retrieve and construct knowledge rather than passively receive it. Teachers can apply this through fill-in-the-blank activities, self-explanation exercises, and problem generation tasks.

The generation effect refers to the memory advantage for information that is actively generated compared to information that is passively received. Norman Slamecka and Peter Graf first documented this phenomenon systematically in 1978, though teachers have intuitively understood its power for centuries.

In their classic experiments, Slamecka and Graf presented participants with word pairs. Some participants read complete pairs (KING-CROWN). Others generated the second word from a cue (KING-CR___). When tested later, participants consistently remembered generated words better than read words, even though both groups spent equal time with the material.

A meta-analysis by Bertsch and colleagues examining 86 studies found an average effect size of 0.40, meaning generated information was remembered about half a standard deviation better than read information. This represents a substantial, reliable advantage that has been replicated across diverse materials, age groups, and learning contexts.

The generation effect connects to broader research on active learning. Whenever students transform, manipulate, or produce information rather than simply receiving it, they engage cognitive processes that strengthen memory formation.

Generation improves memory because it activates multiple cognitive processes including semantic elaboration, distinctive processing, and effortful retrieval. When students generate information, they must search their memory, make connections to existing knowledge, and actively construct responses. This deeper processing creates more retrieval pathways and stronger memory traces than passive reading.

| Technique | Description | Cognitive Benefit | Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-explanation | Explain while learning | Deeper processing | Think-aloud protocols |

| Question generation | Create own questions | Metacognitive awareness | Question stems provided |

| Summary writing | Condense information | Identify key points | Structured templates |

| Elaborative interrogation | Ask why and how | Connect to prior knowledge | Guided prompts |

| Teaching others | Explain to peers | Organisation and retrieval | Peer tutoring |

Understanding why generation works helps teachers design more effective learning activities. Several cognitive mechanisms contribute to the generation advantage.

Generating information requires accessing meaning and making connections. When you complete the stem "The powerhouse of the cell is the MITO___," you must search your memory for information about cells and their components. This deep, meaning-based processing creates richer memory traces than shallow reading.

Craik and Lockhart's levels of processing framework explains this pattern. Shallow processing, focusing on surface features like how a word looks, produces weak memories. Deep processing, engaging with meaning and connections, produces strong memories. Generation inherently demands deep processing.

Generated items stand out in memory because they involve unique cognitive operations. The effort of producing a response creates distinctive episodic features that differentiate generated items from other memories. This distinctiveness makes generated information easier to retrieve later.

Generation requires searching memory and selecting appropriate responses. These processes strengthen retrieval pathways, making future access more reliable. The neural pathways activated during generation become the same routes used during later retrieval, creating well-practised access patterns.

Generated responses carry a sense of ownership that read material lacks. When students create their own explanations or examples, they invest cognitive effort that produces personal significance. This investment may activate emotional and motivational systems that support memory consolidation.

Research consistently shows that generated information is remembered 40-substantially retention was better (effect size d = 0.40) than read information across various contexts and time delays. Studies spanning four decades demonstrate this advantage holds for different types of content, from vocabulary words to scientific concepts. The effect is strongest when learners generate meaningful connections rather than surface-level responses.

The generation effect has been demonstrated across numerous experimental paradigms, establishing its robustness as a learning principle.

The original generation studies used word pairs, and vocabulary learning remains an excellent application. Students who generate translations or definitions remember words better than those who simply review word lists. This has particular relevance for vocabulary instruction in both first and additional languages.

Students who solve problems themselves retain mathematical procedures better than those who study worked examples exclusively. This doesn't mean worked examples aren't valuable; they are, especially for novice learners. But transitioning to problem generation as competence develops produces stronger learning.

Completing sentences, filling in missing words, and generating answers to questions produces better memory for factual content than reading complete sentences. Any prompt that requires students to produce the target information creates the generation advantage.

Generation benefits extend beyond factual recall to conceptual understanding. Students who generate explanations of scientific phenomena understand them better than students who read explanations. Self-explanation, where students explain material to themselves, produces learning beyond what reading alone achieves.

Effective generation activities include cloze exercises where students fill in missing keywords, self-explanation prompts requiring students to explain concepts in their own words, and problem posing where students create their own practise questions. Other powerful techniques include concept mapping from memory, teaching peers without notes, and generating examples of principles. These activities work best when followed by immediate AI-enhanced feedback to correct any errors.

The generation effect translates into numerous practical classroom activities.

Converting information into completion tasks creates generation opportunities. Rather than providing complete notes, leave strategic blanks for students to complete. The missing information should be conceptually important rather than trivial.

For example, instead of providing the note "Photosynthesis uses carbon dioxide and water to produce glucose and oxygen," present "Photosynthesis uses _____ and _____ to produce _____ and _____." Students who generate the missing terms remember them better than those who read the complete statement.

Ask students elucidating concepts words rather than simply reading explanations. Prompts like "Why does this work?" or "How would you explain this to someone who doesn't understand?" require generation of explanations.

Self-explanation works particularly well for procedural knowledge. Students who explain why each step in a procedure works understand and remember the procedure better than those who simply follow steps without explanation.

Having students create problems, rather than just solve them, requires deep understanding of the problem type. A student who can generate a word problem about fractions demonstrates, and strengthens, their understanding of how fractions work in real contexts.

Problem generation also produces excellent formative assessment data. The problems students create reveal what they understand about the structure of a topic.

Students who generate questions about content process it more deeply than those who simply read it. After presenting new material, ask students to generate questions that test understanding. This requires them to identify key concepts and think about what would demonstrate comprehension.

Question generation supports metacognitionby focusing attention on what's important and what might be confusing. Students develop question-asking skills that serve them well in independent learning.

Writing summaries requires identifying key ideas and expressing them in one's own words. Both aspects involve generation. Effective summaries can't simply reproduce original text; they require transformation and synthesis.

Scaffold summary generation by providing structure initially. Ask for three key points, a one-sentence summary, or a summary using specific vocabulary. Gradually release responsibility as students develop summarising skills.

Asking "Why?" questions prompts students to generate explanations. Why is this true? Why does this happen? Why is this important? These questions require connecting new information to existing knowledge and producing explanatory responses.

Elaborative interrogation works especially well when students have relevant prior knowledge to draw upon. The act of generating connections strengthens both the new information and the prior knowledge it connects to.

Generation works synergistically with spaced practise, interleaving, and retrieval practise to maximise learning. Teachers can space generation activities across multiple lessons, interleave different types of generation tasks, and use generation as a form of retrieval practise. Combining generation with elaborative interrogation (asking 'why' questions) creates particularly strong learning outcomes.

Generation becomes even more powerful when combined with other evidence-based learning strategies.

Generation and retrieval practise share features but aren't identical. Retrieval practise involves recalling previously learned information; generation involves producing information during initial learning. Both strengthen memory through active processing.

Combining the two creates particularly durable learning. After initial generation activities, follow up with retrieval practise that requires recalling generated information. This double dose of active processing compounds the benefits.

Spacing generation activities over time provides multiple processing opportunities while allowing memory consolidation between sessions. Generate explanations today, retrieve them tomorrow, elaborate on them next week.

This combination aligns with spaced practise research showing that distributed practise produces more durable learning than massed practise. Each spaced generation opportunity strengthens memory more than equivalent massed practise.

When practising multiple topics, generating mixed practise sessions supports discrimination learning. Students must generate the appropriate strategy for each problem type, not just execute a familiar procedure.

This combination of generation with interleaving supports both retention and discrimination.

Following generation with elaborative processing amplifies benefits. After students generate an initial response, prompting them to explain why that response is correct or how it connects to other knowledge deepens understanding.

In mathematics, students generate problem-solving steps or create their own word problems; in science, they predict experimental outcomes or generate hypotheses; in language arts, they complete story frameworks or generate thesis statements. History teachers can have students generate timelines from memory or create cause-effect relationships between events. Each subject requires adapting generation activities to match its specific content and thinking patterns.

The generation effect applies across the curriculum, though implementation varies by subject.

For reading comprehension, generation activities before, during, and after reading strengthen understanding and memory for content.

The generation effect supports both procedural fluency and conceptual understanding in mathematics.

Science teaching benefits particularly from generation that connects observations to underlying mechanisms and explanations.

Historical thinking involves generating interpretations and explanations, making the generation effect particularly relevant.

The main challenges include students generating incorrect information, the time-intensive nature of generation activities, and resistance from students accustomed to passive learning. Teachers can address these by providing scaffoldinginitially, giving immediate corrective feedback, and gradually increasing the difficulty of generation tasks. Starting with partial generation (like sentence stems) helps build student confidence before moving to full generation.

Teachers sometimes hesitate to implement generation-focused activities. Addressing common concerns helps overcome barriers to adoption.

Scaffold generation appropriately. Start with easier generation tasks and increase difficulty as competence develops. Provide partial information, offer choices, or allow collaboration initially. Frame generation as a learning tool where difficulty is expected and valuable.

The productive struggle of generation is part of what makes it effective. But struggle should be productive, not overwhelming. Adjust difficulty to maintain challenge without causing despair.

Time spent generating produces more learning per minute than time spent receiving instruction passively. The apparent efficiency of direct instruction is often illusory if students don't retain the information. Generation activities constitute high-yield uses of instructional time.

Consider which is more efficient: teaching something once with generation activities that produce retention, or teaching something three times because passive reception didn't stick?

All students benefit from generation, though activities must be appropriately scaffolded. Provide more support for struggling learners through partial completions, cued generation, or collaborative generation. The benefits of generation are often largest for students who would otherwise engage in passive processing.

Scaffolding is key. Reduce the generation demand to a level that challenges but doesn't overwhelm, then gradually increase expectations.

Errors followed by feedback are not harmful and may enhance learning. The key is providing timely correction. Generate-then-feedback sequences help students identify and correct misconceptions.

Research on the hypercorrection effect shows that confidently held errors that are corrected are remembered especially well. Generation that produces errors, followed by correction, can be more powerful than error-free passive learning.

Generation enhances metacognition by making students more aware of what they know and don't know through immediate feedb ack from their attempts. When students try to generate information and struggle, they recognise knowledge gaps more clearly than when passively reading. This awareness helps students regulate their study time more effectively and seek help for specific areas of difficulty.

Generation activities support metacognitive development by revealing what students actually know versus what they think theyknow. When required to generate, students discover gaps in their understanding that passive review would miss.

This metacognitive benefit has two components. First, generation reveals actual knowledge state, providing accurate self-assessment. Second, students can use this information to target gaps identified through generation, improving study decisions.

Students who experience the generation effect directly often spontaneously adopt generation-based study strategies. Teaching students about the generation effect explicitly supports this transfer to independent learning.

The generation effect works across all age groups but manifests differently: elementary students benefit from simple fill-in activities and generating examples, while secondary students can handle more complex generation like creating analogies or explanations. Research shows the effect is strong from age 7 through adulthood, though younger students need more scaffolding and shorter generation tasks. The key is matching generation difficulty to students' cognitive development and prior knowledge.

The generation effect has been demonstrated across the lifespan, from young children to older adults.

Younger children benefit from generation but may need more scaffolding. Simple completion tasks, paired generation activities, and verbal rather than written generation work well. Games that require generating answers rather than selecting from options use the effect playfully.

Adolescents can engage in more complex generation tasks including extended explanations, problem creation, and metacognitive reflection on their generation performance. The self-testing applications of generation become increasingly relevant as students prepare for examinations.

The generation effect remains strong in adult learning contexts. Professional development, workplace training, and self-directed study all benefit from generation-focused approaches. Adults can be taught the generation effect explicitly and encouraged to incorporate generation into their learning strategies.

Brain imaging studies show generation activates the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex more strongly than passive reading, indicating deeper memory encoding and executive processing. The effort required to generate information triggers the release of neurotransmitters that strengthen synaptic connections. This increased neural activity creates more distinctive memory traces that are easier to retrieve later.

Brain imaging studies reveal that generation engages different neural networks than reading. During generation, prefrontal regions associated with executive function and strategic retrieval show increased activation. Medial temporal lobe structures involved in memory formation are more active during generation than passive reading.

These neural differences help explain why generated information is remembered better. Generation engages the brain systems most important for memory formation more intensively than passive reading.

The additional neural activity during generation may also explain why generation feels more effortful than reading. This subjective difficulty is a signal that learning is occurring, not a sign that something is wrong.

Teachers should start by identifying key concepts that need long-term retention, then design generation activities that target these concepts through partial completion tasks, self-testing, or student-created examples. Implementation works best when introduced gradually, starting with 10-15% of class time devoted to generation activities and increasing as students become comfortable. Regular cycles of generation, feedback, and re-generation improve the learning benefits.

The generation effect offers teachers a straightforward principle: whenever possible, have students produce information rather than receive it. This doesn't mean eliminating direct instruction, which remains essential for introducing new concepts. Rather, it means following instruction with generation opportunities.

Practical implementation might begin with:

Small changes accumulate into significant learning benefits. Each generation opportunity strengthens memory more than equivalent passive review. Over time, embedding generation throughout instruction produces substantially more durable learning.

Essential readings include Slamecka and Graf's 1978 foundational paper establishing the effect, Bertsch et al.'s 2007 meta-analysis quantifying its strength, and Foos et al.'s 1994 work on classroom applications. McNamara and Healy's research on generation in skill learning and deWinstanley and Bjork's work on generation combined with other techniques provide practical implementation guidance. These papers offer evidence-based strategies teachers can adapt for their specific contexts.

These papers provide deeper exploration of the generation effect and its educational applications.

The foundational paper establishing the generation effect as a strong memory phenomenon. Through five experiments, Slamecka and Graf demonstrated that self-generated words are consistently remembered better than read words across various generation tasks and test formats. This research launched decades of subsequent investigation.

This comprehensive meta-analysis synthesised findings from 86 studies examining the generation effect. The analysis confirmed a medium-to-large effect size and identified moderating factors including generation task type, test format, and retention interval. Essential reading for understanding the scope and boundaries of generation effects.

Michelene Chi's work on self-explanation demonstrates how generating explanations produces learning beyond what reading achieves. The paper distinguishes between self-explanation that fills gaps in understanding and self-explanation that repairs misconceptions, both of which benefit from the generation process.

This early application of the generation effect to educational contexts explored how generating responses during learning improves memory for prose passages. The research established that generation benefits extend beyond word pairs to more complex educational materials.

This paper extends generation research to show that even unsuccessful attempts to generate answers enhance subsequent learning. Testing students before teaching, even when they get answers wrong, produces better final learning than teaching without pretesting.

When students generate information rather than simply reading it, their brains activate in fundamentally different ways. Neuroimaging studies reveal that self-generation lights up multiple brain regions simultaneously: the hippocampus for memory formation, the prefrontal cortex for executive control, and critically, the semantic networks that connect new information to existing knowledge.

This multi-region activation creates what neuroscientists call "distinctive processing." Unlike passive reading, which primarily engages visual processing areas, generation forces the brain to reconstruct information actively. This reconstruction process strengthens synaptic connections through a mechanism called long-term potentiation, essentially creating more strong neural pathways for later retrieval.

The effort required during generation also triggers the release of neurotransmitters like dopamine and norepinephrine, which enhance memory consolidation. This explains why struggling to recall an answer, even unsuccessfully, improves later retention more than being given the answer immediately.

In practise, teachers can harness these mechanisms through simple adjustments. Instead of providing complete worked examples in maths, show the first two steps and have students generate the remaining solution. During history lessons, rather than listing all causes of an event, provide two causes and ask students to generate a third. In science, present an incomplete diagram of the water cycle and have students fill in missing stages from memory.

These generation activities work because they force the brain into active reconstruction mode, creating memories that are both more distinctive and more deeply integrated into existing knowledge networks. The temporary difficulty students experience isn't a barrier to learning; it's the very mechanism that makes the learning stick.

Transforming the generation effect from theory to practise requires deliberate changes to how we structure learning activities. Rather than presenting complete information, teachers can create opportunities for students to actively produce knowledge throughout lessons.

One powerful technique is the completion task, where students fill in missing components rather than copying complete examples. In a Year 7 science lesson on photosynthesis, instead of providing the full equation, present: "6CO₂ + 6H₂O → _______ + 6O₂" and have students generate the missing glucose formula. Research by Jacoby (1978) showed that words completed from fragments are remembered 20-30% better than words simply read.

Self-explanation prompts offer another practical approach. After teaching a mathematical concept, ask students to write explanations of solved problems in their own words before attempting practise questions. A maths teacher might display a completed factorisation problem and ask: "Explain to your partner why we chose these factors." This generation of explanations strengthens understanding more effectively than reviewing worked examples alone.

Testing as generation provides particularly strong benefits. Replace revision handouts with retrieval practise sheets where students generate answers from memory. Create question stems that require completion: "The Battle of Hastings occurred in _______" rather than "When did the Battle of Hastings occur?" This subtle shift engages generation processes that enhance retention.

Implementation requires patience; students initially find generation tasks more challenging than passive reading. However, this desirable difficulty signals deeper processing at work. Start with partially completed examples, gradually increasing the generation demands as students build confidence. The initial struggle yields superior long-term retention, making the extra effort worthwhile for both teachers and learners.

Whilst the generation effect is remarkably strong, it doesn't work universally. Understanding its boundaries helps teachers apply it more effectively and avoid frustration when certain activities fall flat.

The most significant limitation occurs with complex, unfamiliar material. When students lack sufficient background knowledge, generation activities can overwhelm working memory rather than strengthen it. For instance, asking Year 7 students to generate explanations for photosynthesis before they understand basic plant biology often leads to confusion, not clarity. Research by Kang and colleagues (2007) found that generation only benefits learning when students possess adequate prior knowledge to draw upon.

Timing matters crucially. Immediate testing shows strong generation effects, but these advantages can diminish over longer intervals if students generate incorrect responses initially. A student who incorrectly fills in "osmosis" when the answer is "diffusion" may strengthen the wrong association, particularly without immediate corrective feedback.

The effect also weakens with certain types of content. Arbitrary associations, such as foreign language vocabulary with no etymological connections, show smaller benefits from generation. Similarly, precise procedural sequences, like the steps in long division, may actually suffer when students generate incomplete or disordered steps.

Teachers should consider three practical adjustments. First, provide worked examples before generation tasks with novel content; students need a foundation before they can build effectively. Second, ensure immediate feedback for generation activities, particularly in subjects where precision matters. Third, match the generation difficulty to student expertise; beginners benefit from completing partial solutions whilst advanced students thrive when generating entire responses from scratch.

Recognising these limitations doesn't diminish the generation effect's value. Rather, it helps teachers deploy this powerful tool more strategically, knowing when to guide students actively and when to step back and let them create.

In 1978, cognitive psychologists Norman Slamecka and Peter Graf stumbled upon a finding that would reshape our understanding of memory formation. Their experiment was deceptively simple: one group of students read word pairs like 'hot-cold', whilst another group had to complete word stems like 'hot-c___'. When tested later, the students who generated the word 'cold' themselves remembered significantly more pairs than those who simply read them. This straightforward discovery revealed something profound about how our brains encode information.

The implications rippled through educational psychology. Researchers began testing the effect across different contexts, from foreign language learning to mathematical problem-solving. Time after time, the results held firm: whether students were generating synonyms, solving equations, or creating their own examples, the act of production consistently outperformed passive reception. Studies showed retention rates improving by 30-50% when learners generated content rather than consuming pre-made materials.

For teachers, this research offered a clear directive: stop doing all the work for your students. Instead of providing complete notes, leave strategic gaps for pupils to fill. Rather than showing fully worked examples, present problems halfway through and ask students to complete them. When teaching vocabulary, give definitions and ask students to generate the terms, or provide terms and have them create definitions. These simple adjustments activate the generation effect without requiring wholesale changes to your teaching approach.

The most striking aspect of Slamecka and Graf's discovery was its universality. The generation effect works across ages, subjects, and ability levels. Whether you're teaching Year 2 pupils their times tables or A-level students complex chemical equations, the principle remains constant: what students create, they remember.

When you generate information, your brain activates multiple processing systems simultaneously. Unlike passive reading, which primarily engages recognition networks, creating content fires up retrieval pathways, semantic processing regions, and executive control centres. This multi-system activation explains why pupils who write their own definitions remember vocabulary at nearly double the rate of those who copy from textbooks.

The cognitive effort required to produce information strengthens memory through what researchers call 'desirable difficulty'. Your brain must search through existing knowledge, make connections, and construct new understanding; this struggle creates distinctive memory traces. For instance, when pupils generate their own examples of metaphors rather than studying provided ones, they activate personal experiences and emotions that serve as powerful retrieval cues later.

Brain imaging studies reveal that generation tasks light up the hippocampus, the brain's memory consolidation centre, far more intensely than reading activities. This increased neural activity translates directly to classroom results. Teachers who replace traditional copying exercises with sentence completion tasks, where pupils must generate missing keywords, report 30-40% better retention on end-of-unit assessments.

The prefrontal cortex, responsible for planning and organising thoughts, shows heightened engagement during generation activities. This explains why pupils who create their own study questions before reading a text comprehend and remember content more effectively than those given pre-made questions. The act of formulating questions requires deeper processing of material relationships and significance, creating what cognitive scientists term 'elaborative encoding', the gold standard for durable learning.

Transform your existing resources into generation-based activities with minimal preparation time. Instead of providing complete notes, give students partial information with strategic gaps. For instance, when teaching photosynthesis, provide the equation with missing components: 6CO₂ + ____ → C₆H₁₂O₆ + 6O₂. Students must recall and insert '6H₂O', creating stronger memories than copying the complete equation. This simple modification takes seconds but significantly improves retention.

Replace traditional vocabulary lists with word-stem completion exercises. Rather than presenting 'metamorphosis: a complete change in form', show 'meta_____: a complete change in form'. Students generating 'morphosis' engage deeper cognitive processing than those who simply read the full term. Research by Slamecka and Graf (1978) found this technique improved recall by up to 40% compared to passive reading, particularly effective for science terminology and foreign language vocabulary.

Turn review sessions into active generation opportunities using the 'test-enhanced learning' approach. Begin lessons by asking students to write everything they remember about the previous topic before checking their notes. This retrieval practise, even when incomplete or incorrect, strengthens memory pathways more effectively than re-reading perfect notes. Year 7 students using this method in history lessons showed 35% better retention after one week compared to those who reviewed by reading.

Create 'explanation challenges' where students must teach concepts to partners using only keywords as prompts. Provide five key terms related to the water cycle, then have students generate complete explanations connecting these concepts. This approach combines the generation effect with elaborative processing, making it particularly powerful for complex topics across all subject areas.

The generation effect is the memory advantage that occurs when learners actively generate information themselves rather than passively reading it. Research shows that self-generated information is remembered substantially outperforming retention (effect size d = 0.40) in comparison to read information because it requires deeper cognitive processing. This gives teachers a powerful, evidence-based strategy to improve long-term retention in their classrooms.

Teachers can use fill-in-the-blank exercises where students complete missing keywords, self-explanation prompts requiring students articulating concepts in their own words words, and problem-posing activities where students create practise questions. Other effective techniques include concept mapping from memory, peer teaching without notes, and having students generate their own examples of principles being taught.

Generation improves memory through several mechanisms: it requires deeper semantic processing as students must search memory and make connections, it creates enhanced distinctiveness making information stand out, and it strengthens retrieval pathways. Additionally, generated responses carry a sense of personal investment that activates emotional and motivational systems supporting memory consolidation.

Yes, research spanning four decades shows the generation effect works across diverse content types including vocabulary words, mathematical problems, factual knowledge, and conceptual understanding. The effect is particularly strong for vocabulary learning, mathematical procedures, and scientific concepts. However, it works best when learners generate meaningful connections rather than surface-level responses.

The main challenge is ensuring students receive immediate feedback to correct any errors in their generated responses, as incorrect generation can reinforce misconceptions. Teachers also need to consider that generation activities work best when students have some foundational knowledge, so complete beginners may benefit from worked examples before transitioning to generation tasks.

The article illustrates this with two students: one who repeatedly reads and highlights notes, and another who covers notes and writes definitions from memory before checking. Decades of research consistently favour the second approach, showing that active generation produces substantially better retention than passive reading or highlighting.

Instead of providing complete notes, create strategic blanks for students to fill in with conceptually important information. Rather than showing worked mathematical examples, have students solve problems themselves after initial instruction. Transform reading comprehension by having students explain concepts in their own words instead of simply reading provided explanations.

These peer-reviewed studies provide the research foundation for the strategies discussed in this article:

A controlled study of team-based learning for undergraduate clinical neurology education View study ↗

118 citations

N. Tan et al. (2011)