Sustained Shared Thinking: A Teacher's Guide

Extend children's learning through meaningful dialogue and open questions. A practical guide to Sustained Shared Thinking strategies for early years.

Extend children's learning through meaningful dialogue and open questions. A practical guide to Sustained Shared Thinking strategies for early years.

Have you ever noticed how some classroom conversations spark genuine curiosity and deep thinking in your pupils, while others fall flat? The secret lies in mastering sustained shared thinking, a teaching approach that transforms everyday interactions into powerful learning experiences. Rather than simply asking questions or giving answers, you'll learn to guide collaborative thinking episodes. In these episodes, you and your children explore ideas together, building understanding step by step. This guide will show you exactly how to create these meaningful learning conversations that research proves significantly boost children's cognitive development and academic outcomes.

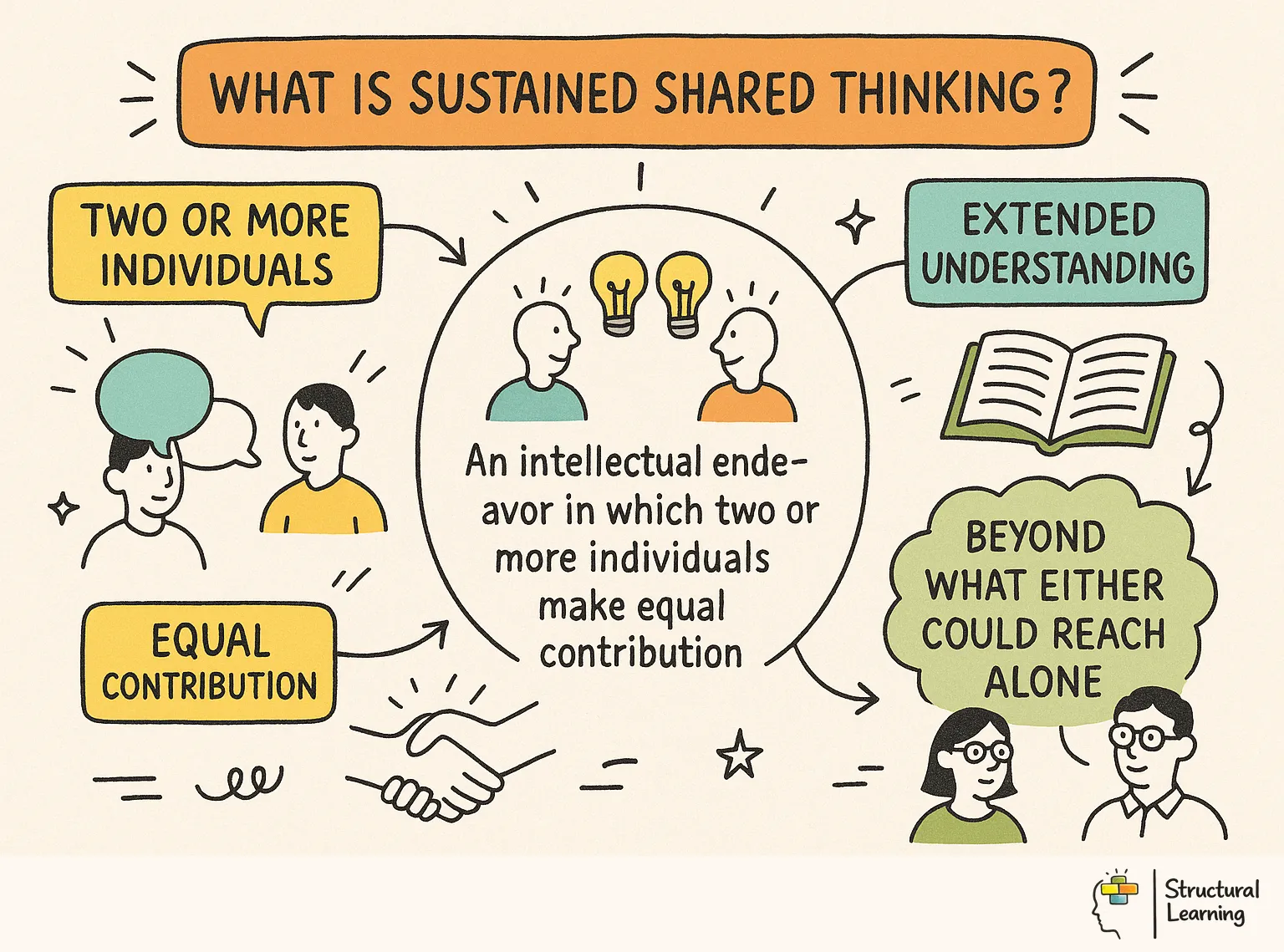

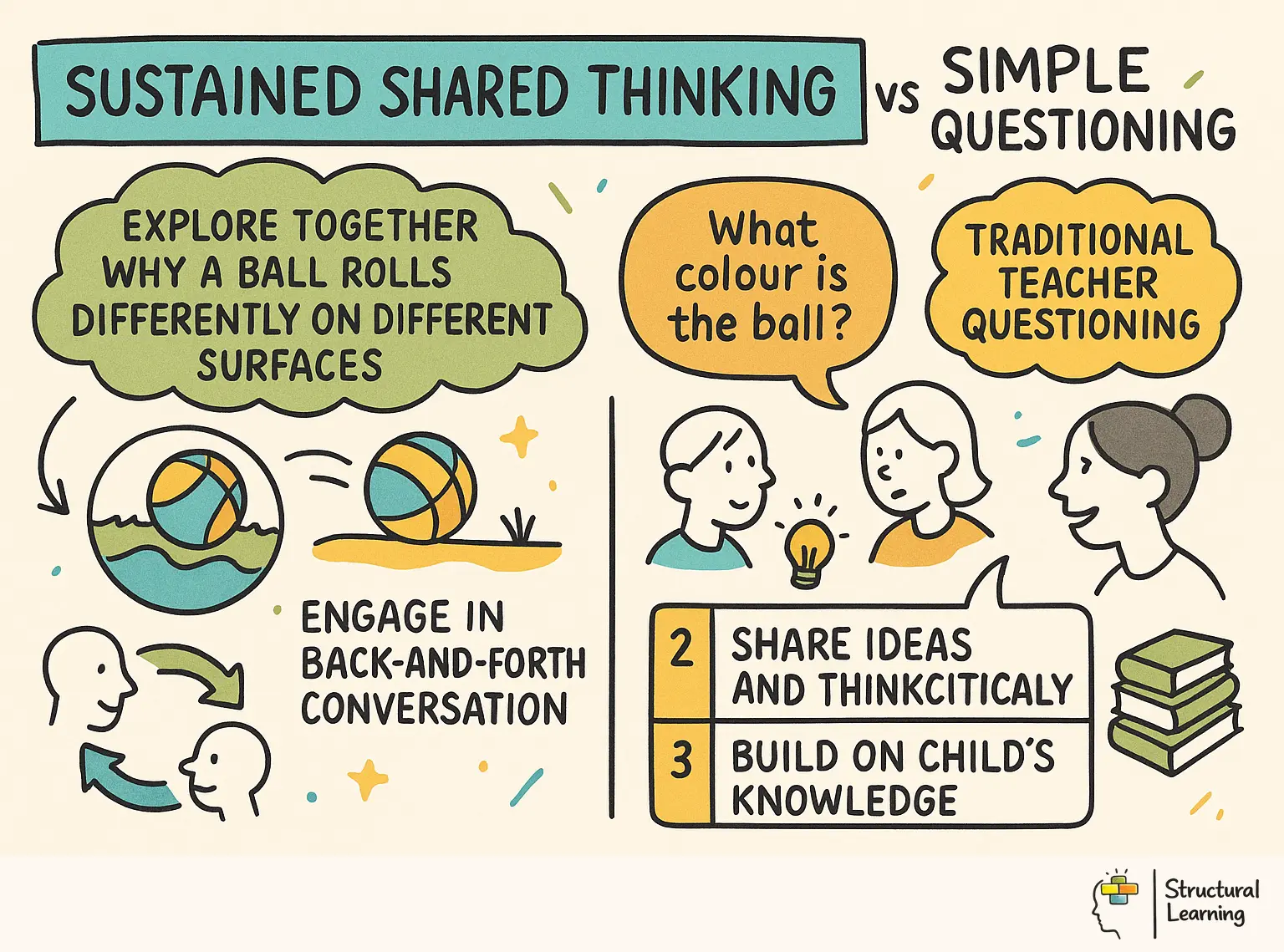

Sustained shared thinking occurs when two or more individuals engage together in an intellectual endeavour to solve a problem, clarify a concept, evaluate an activity, or extend a narrative. Both parties must contribute to the thinking, and the interaction must develop and extend understanding beyond where either would reach alone.

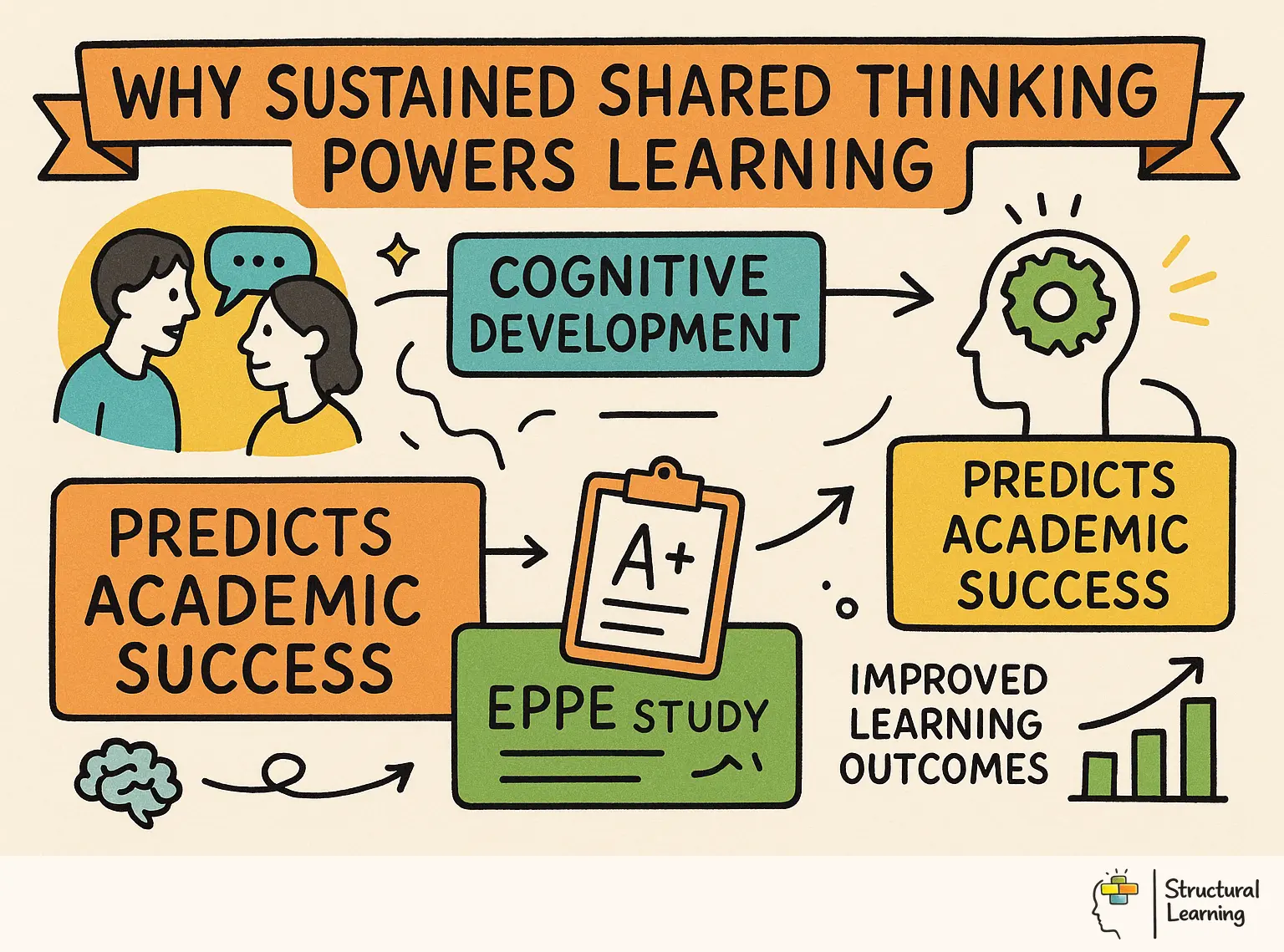

This definition comes from the landmark EPPE (Effective Provision of Pre-school Education) research project led by Professors Iram Siraj-Blatchford and Kathy Sylva. Their longitudinal study, which tracked thousands of children from age three through primary school, identified sustained shared thinking as one of the most powerful pedagogical strategies for promoting cognitive development.

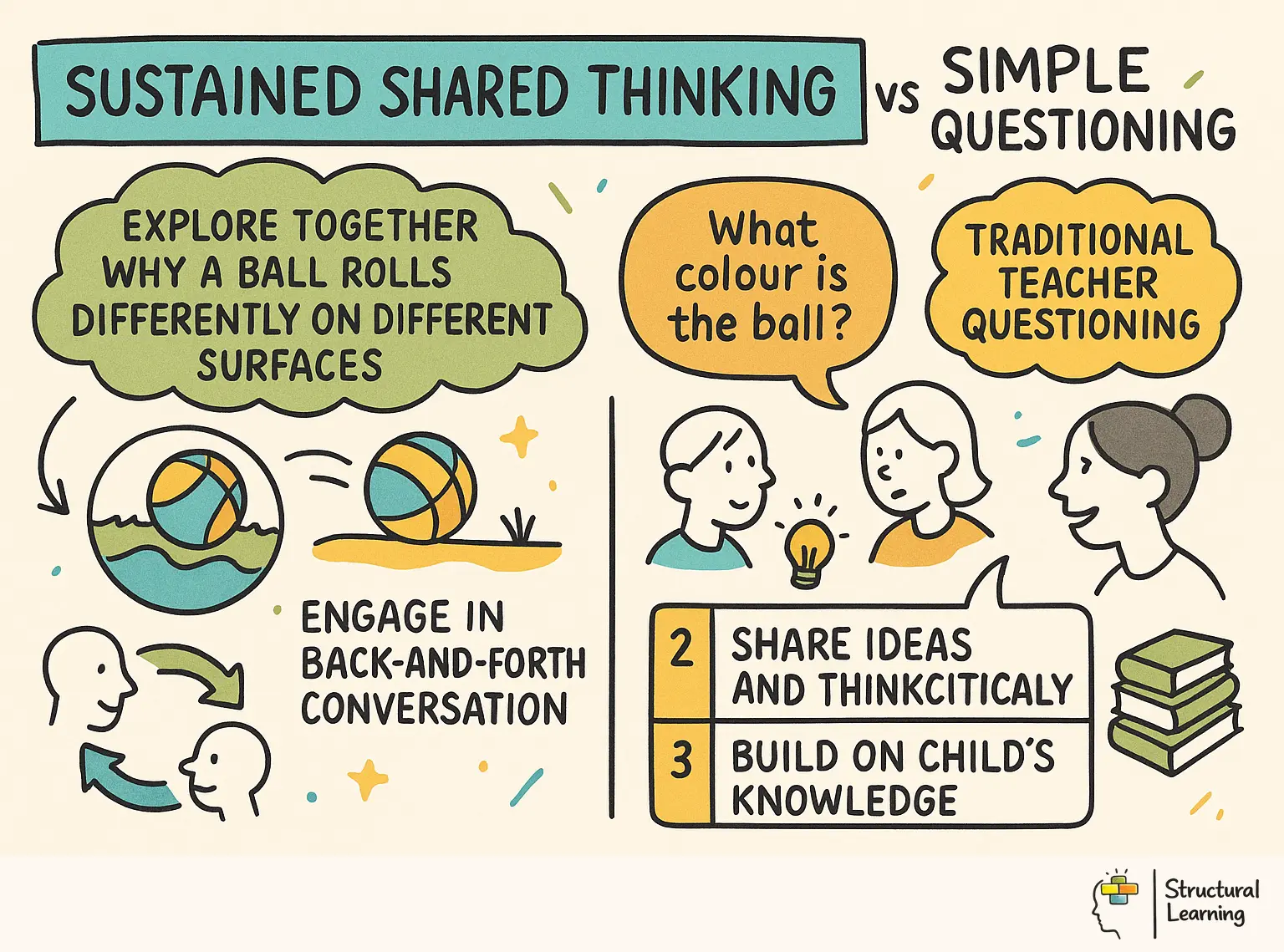

The key word is "sustained." Brief exchanges where adults ask questions and children answer do not qualify. Neither do interactions where adults provide information and children receive it. Sustained shared thinking requires extended engagement where both participants genuinely contribute ideas, build on each other's suggestions, and reach understanding together.

This differs from simple

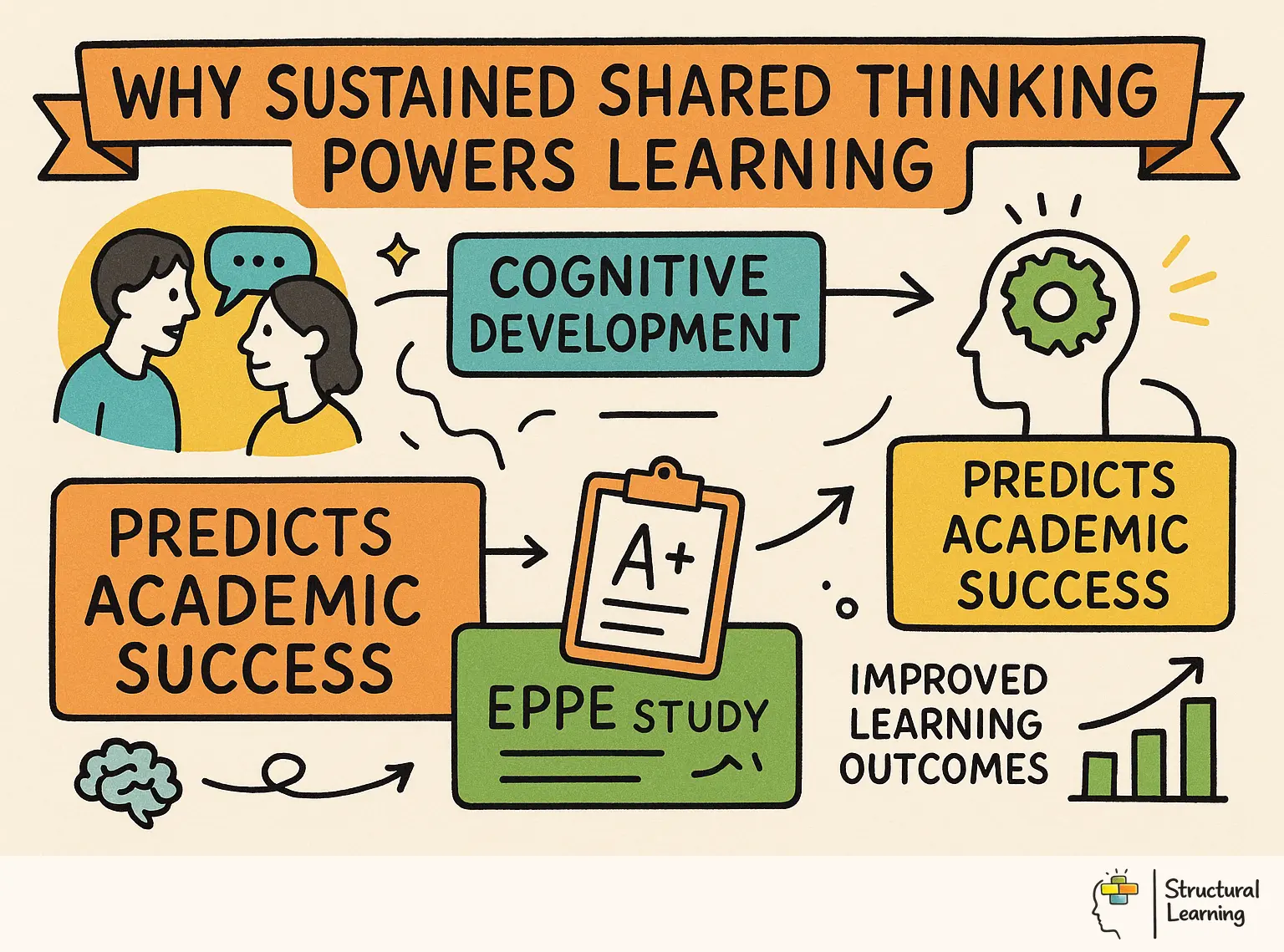

The EPPE research demonstrated that settings where sustained shared thinking occurred frequently produced significantly better cognitive outcomes for children. This was not simply correlation: the quality of adult-child interactions, specifically the presence of sustained shared thinking episodes, predicted later academic success.

This connects to broader research on cognitive development. Vygotsky's concept of the Zone of Proximal Development describes how children learn best when supported to reach beyond their current independent capability. Sustained shared thinking operationalises this theory by creating moments where adult support extends children's thinking in real time.

The approach also develops metacognition. When children engage in thinking alongside a more experienced thinker, they observe thinking processes being modelled. Over time, they internalise these processes and apply them independently. The adult makes thinking visible.

Research into talk for learningsupports these findings. High-quality dialogue, where children are active participants rather than passive recipients, produces measurably better learning outcomes than traditional teacher-talk models.

How do you know when sustained shared thinking is happening? Look for these characteristics:

Neither the adult nor the child dominates. Ideas flow in both directions. The adult might introduce a concept, but the child extends it. The child might ask a question that takes the conversation in an unexpected direction, and the adult follows.

The conversation sustains beyond a single exchange. Initial ideas are built upon, challenged, refined, and extended. What emerges at the end differs from what either party thought at the start.

The adult does not simply lead the child towards a predetermined answer. There is authentic exploration, genuine wondering, real problem-solving. The adult might not know the answer, or might genuinely consider the child's perspective as potentially valid.

Phrases like "I wonder if...", "What do you think about...", "That's interesting because...", and "Let's try..." indicate collaborative intellectual engagement. Questions are open and exploratory rather than closed and testing.

Both parties care about the outcome. There is curiosity, interest, perhaps excitement. The conversation matters to both participants, not just as a teaching exercise but as genuine inquiry.

Sustained shared thinking requires topics worth thinking about. Routine activities with obvious answers offer little scope for extended exploration. Instead, introduce problems without clear solutions, materials that prompt investigation, or scenarios requiring genuine reasoning.

Open-ended resources work well: construction materials without prescribed outcomes, natural objects to investigate, art materials allowing experimentation. When children engage with these resources, join them with genuine curiosity about what they are discovering.

Not all open questions promote sustained shared thinking, but closed questions rarely do. Move beyond questions with single correct answers towards questions exploring possibilities, reasons, and alternatives.

Effective prompts include:

Avoid rapid-fire questioning. Give time for thought. Allow silence. Sometimes the most productive response is simply waiting with an interested expression.

Make your own thinking visible. When encountering something puzzling, verbalise your reasoning process: "I'm not sure about this. Let me think... I notice that... which makes me wonder... but then..." This demonstrates that thinking involves uncertainty, exploration, and revision.

When pupils verbalise their reasoning, they strengthen both comprehension and metacognition — a process central to the Say It methodology.

Admit when you do not know. "That's a really good question. I'm not sure. What could we do to find out?" This positions you as a co-investigator rather than an answer-provider.

Sustained shared thinking emerges more readily when children care about the topic. Pay attention to what captures their curiosity and build upon those interests. A conversation about something the child chose to investigate will sustain longer than one you imposed.

This does not mean abandoning learning intentions. Rather, look for connections between children's interests and your curriculum goals. A child fascinated by dinosaurs might explore scientific concepts through that lens. A child building towers might investigate mathematical concepts through construction.

When children's ideas diverge from your expectations, resist the urge to steer them back. Instead, follow their thinking and look for opportunities to extend it. Their "wrong" answer might reveal interesting reasoning worth exploring.

If a child suggests something incorrect, explore why they think that rather than simply correcting. "That's interesting. What made you think that?" Often, the reasoning contains partial understanding that, once identified, can be built upon.

The EPPE research focused on early years, where sustained shared thinking has particular power. Young children are naturally curious and have not yet learned to wait for adults to provide answers. This makes them excellent partners in shared inquiry.

During play, position yourself alongside children rather than opposite them. Engage with the same materials they are using. Wonder aloud about what you notice. Let them guide exploration while you contribute observations and questions.

As children grow, sustained shared thinking remains valuable but requires adaptation. Older children may expect teachers to have answers and may be reluctant to offer speculative ideas. Create classroom cultures where tentative thinking is valued.

Use "think alouds" during teaching to model ongoing reasoning. Engage in genuine problem-solving with students, not just demonstrating solved problems. Create investigation tasks where you genuinely do not know what students will discover.

Subject complexity in secondary schools offers rich territory for sustained shared thinking. Introduce problems that experts genuinely debate. Engage students in reasoning about ambiguous evidence or competing interpretations.

Seminar-style discussions, philosophical inquiry, and collaborative investigation all create space for sustained shared thinking. The key is positioning yourself as a more experienced thinker rather than an authority with answers.

Sustained shared thinking need not be lengthy. Brief moments of genuine intellectual partnership accumulate. Look for opportunities during transitions, alongside routine activities, or in small group work. Quality matters more than duration.

This expectation reflects classroom culture, not child nature. Explicitly value questions over answers. Respond to questions with "What do you think?" more often than with explanations. Celebrate uncertainty and exploration.

Preparation helps. For topics you will teach, consider what genuine puzzles exist. What do experts debate? What might children find surprising? Have a repertoire of general prompts ready: "Why do you think...?", "What would happen if...?", "How else could we...?"

Start where children are. Some need confidence before contributing to shared thinking. Begin with topics they know well, acknowledge their expertise, and gradually extend into new territory. Pair reluctant talkers with supportive peers.

Questions matter, but not all questions support sustained shared thinking. Research distinguishes between questions that close down thinking (seeking specific answers) and questions that open up thinking (inviting exploration).

Effective questioning in sustained shared thinking:

Avoid questions that:

The best "questions" are often not grammatically questions at all. "I wonder..." statements, expressions of puzzlement, and invitations to observe all prompt thinking without demanding correct answers.

Sustained shared thinking aligns with several established pedagogical approaches:

scaffolding-in-education-a-teachers-guide"> Scaffolding involves supporting learners to achieve more than they could independently. Sustained shared thinking is a form of intellectual scaffolding where adult thinking processes support child thinking.

Dialogic teaching emphasises purposeful, cumulative dialogue where ideas build over time. Sustained shared thinking exemplifies dialogic principles.

Inquiry-based learning positions children as investigators constructing understanding. Sustained shared thinking supports inquiry by modelling investigative thinking.

Co-construction in Vygotskian theory involves knowledge being built through social interaction. Sustained shared thinking is co-construction in action.

A child is building a tower that keeps falling. Instead of explaining how to build more stably, the adult sits alongside and says: "I notice it keeps falling when you add that block. I wonder why..." The child suggests the tower is too skinny. Together, they explore: "What could we try?" The child proposes making the base wider. They experiment, observe, discuss what they notice, and try different approaches.

A child notices their shadow is longer in the afternoon than at lunchtime. The adult responds: "That's interesting. I wonder why that might be... Together, they watch the sun's position, think about links between sun height and shadow length, and plan ways to test their ideas. Neither holds the full answer; both contribute to developing understanding.

Secondary students are studying a historical figure's controversial choice. The teacher poses it as a genuine dilemma: "I've read arguments on both sides, and I'm genuinely uncertain what I would have done." Students offer perspectives. The teacher offers counter-considerations. Ideas are challenged and refined. The conversation sustains because genuine intellectual engagement exists.

Is sustained shared thinking the same as Socratic questioning?

There are similarities, but Socratic questioning often involves the teacher knowing the answer and leading students towards it. Sustained shared thinking is more genuinely collaborative, with both parties contributing to developing understanding.

How do I assess whether sustained shared thinking is happening?

Record and review interactions. Look for the characteristics described above: mutual contribution, developing ideas, genuine uncertainty, exploratory language, emotional engagement. Coding frameworks from the EPPE research can guide assessment.

Can sustained shared thinking happen between children?

Yes. When children genuinely collaborate on intellectual problems, building on each other's ideas over time, sustained shared thinking is occurring. Adults can set up conditions that promote this.

How often should sustained shared thinking happen?

The EPPE research found that even relatively infrequent episodes had significant impact. Aim for quality moments rather than arbitrary frequency targets. Several genuine episodes per day in early years, regularly during teaching at later stages.

Sustained shared thinking transforms the relationship between teachers and learners. Instead of knowledge transfer from expert to novice, it creates intellectual partnership where both participants contribute, explore, and learn together. The research evidence for its impact is strong, and the approach aligns with broader understanding of how learning works.

Begin by noticing opportunities for genuine shared inquiry. When a child wonders about something, wonder alongside them. When a student raises a puzzling question, explore it together rather than simply answering. Over time, these moments of sustained shared thinking will accumulate, building both understanding and the disposition to think deeply.

These peer-reviewed studies provide deeper insights into sustained shared thinking: a teacher's guide to deeper learning conversations and its application in educational settings.

Siraj‐Blatchford et al. (2009)

This paper examines how teachers can support children's learning through play using Vygotskian theories, with a specific focus on sustained shared thinking pedagogies in early childhood education. It provides teachers with theoretical frameworks for understanding how meaningful interactions during play can promote deeper learning and cognitive development in young children.

Blatchford et al. (2018)

This research investigates how classroom factors like class size, student groupings, and teacher interactions affect learning outcomes, particularly for students with special educational needs and disabilities. It offers teachers practical insights into how classroom organisation and management decisions can influence the quality of learning conversations and sustained interactions with all students.

Blatchford et al. (2001)

This study explores the relationships between class size and how teachers organise students into different groupings within classrooms. It provides teachers with evidence-based guidance on creating optimal classroom contexts that support meaningful peer interactions and sustained shared thinking opportunities.

Sylva et al. (2010)

This thorough research project provides evidence about what makes early childhood education effective, drawing from longitudinal studies of children's development and learning outcomes. It offers teachers research-backed insights into the practices and interactions that promote sustained learning, including the importance of quality adult-child conversations in educational settings.

Blatchford et al. (2011)

This study examines how different class sizes affect the quality and frequency of teacher-student interactions and overall classroom engagement across primary and secondary schools. It provides teachers with evidence about how structural classroom factors influence their ability to engage in sustained shared thinking and meaningful learning conversations with students.

Generate a progressive oracy implementation plan with talk protocols, sentence stems, and assessment checkpoints for your key stage.

These peer-reviewed studies provide the research foundation for the strategies discussed in this article:

Language View study ↗

1 citations

Lei Wu & Kamariah Abu Bakar (2025)

This thorough study examined how teachers in China, the United States, and the UK use scaffolding techniques to support early readers, revealing significant cultural differences in how educators apply

AI AS A DIGITAL SCAFFOLD: AN INTEGRATIVE REVIEW OF VYGOTSKY'S View study ↗

1 citations

Wan Hazwani Wan Hamedi et al. (2025)

This review examines how artificial intelligence tools can function as digital teaching assistants that provide personalised support within students' zones of proximal development, much like human teachers do through scaffolding. The research reveals that current AI educational technologies show promise but still lack the nuanced understanding and relationship-building that characterize effective human scaffolding. Teachers interested in educational technology will gain insights into how AI tools might complement, rather than replace, the sustained shared thinking conversations that drive deep learning.

Have you ever noticed how some classroom conversations spark genuine curiosity and deep thinking in your pupils, while others fall flat? The secret lies in mastering sustained shared thinking, a teaching approach that transforms everyday interactions into powerful learning experiences. Rather than simply asking questions or giving answers, you'll learn to guide collaborative thinking episodes. In these episodes, you and your children explore ideas together, building understanding step by step. This guide will show you exactly how to create these meaningful learning conversations that research proves significantly boost children's cognitive development and academic outcomes.

Sustained shared thinking occurs when two or more individuals engage together in an intellectual endeavour to solve a problem, clarify a concept, evaluate an activity, or extend a narrative. Both parties must contribute to the thinking, and the interaction must develop and extend understanding beyond where either would reach alone.

This definition comes from the landmark EPPE (Effective Provision of Pre-school Education) research project led by Professors Iram Siraj-Blatchford and Kathy Sylva. Their longitudinal study, which tracked thousands of children from age three through primary school, identified sustained shared thinking as one of the most powerful pedagogical strategies for promoting cognitive development.

The key word is "sustained." Brief exchanges where adults ask questions and children answer do not qualify. Neither do interactions where adults provide information and children receive it. Sustained shared thinking requires extended engagement where both participants genuinely contribute ideas, build on each other's suggestions, and reach understanding together.

This differs from simple

The EPPE research demonstrated that settings where sustained shared thinking occurred frequently produced significantly better cognitive outcomes for children. This was not simply correlation: the quality of adult-child interactions, specifically the presence of sustained shared thinking episodes, predicted later academic success.

This connects to broader research on cognitive development. Vygotsky's concept of the Zone of Proximal Development describes how children learn best when supported to reach beyond their current independent capability. Sustained shared thinking operationalises this theory by creating moments where adult support extends children's thinking in real time.

The approach also develops metacognition. When children engage in thinking alongside a more experienced thinker, they observe thinking processes being modelled. Over time, they internalise these processes and apply them independently. The adult makes thinking visible.

Research into talk for learningsupports these findings. High-quality dialogue, where children are active participants rather than passive recipients, produces measurably better learning outcomes than traditional teacher-talk models.

How do you know when sustained shared thinking is happening? Look for these characteristics:

Neither the adult nor the child dominates. Ideas flow in both directions. The adult might introduce a concept, but the child extends it. The child might ask a question that takes the conversation in an unexpected direction, and the adult follows.

The conversation sustains beyond a single exchange. Initial ideas are built upon, challenged, refined, and extended. What emerges at the end differs from what either party thought at the start.

The adult does not simply lead the child towards a predetermined answer. There is authentic exploration, genuine wondering, real problem-solving. The adult might not know the answer, or might genuinely consider the child's perspective as potentially valid.

Phrases like "I wonder if...", "What do you think about...", "That's interesting because...", and "Let's try..." indicate collaborative intellectual engagement. Questions are open and exploratory rather than closed and testing.

Both parties care about the outcome. There is curiosity, interest, perhaps excitement. The conversation matters to both participants, not just as a teaching exercise but as genuine inquiry.

Sustained shared thinking requires topics worth thinking about. Routine activities with obvious answers offer little scope for extended exploration. Instead, introduce problems without clear solutions, materials that prompt investigation, or scenarios requiring genuine reasoning.

Open-ended resources work well: construction materials without prescribed outcomes, natural objects to investigate, art materials allowing experimentation. When children engage with these resources, join them with genuine curiosity about what they are discovering.

Not all open questions promote sustained shared thinking, but closed questions rarely do. Move beyond questions with single correct answers towards questions exploring possibilities, reasons, and alternatives.

Effective prompts include:

Avoid rapid-fire questioning. Give time for thought. Allow silence. Sometimes the most productive response is simply waiting with an interested expression.

Make your own thinking visible. When encountering something puzzling, verbalise your reasoning process: "I'm not sure about this. Let me think... I notice that... which makes me wonder... but then..." This demonstrates that thinking involves uncertainty, exploration, and revision.

When pupils verbalise their reasoning, they strengthen both comprehension and metacognition — a process central to the Say It methodology.

Admit when you do not know. "That's a really good question. I'm not sure. What could we do to find out?" This positions you as a co-investigator rather than an answer-provider.

Sustained shared thinking emerges more readily when children care about the topic. Pay attention to what captures their curiosity and build upon those interests. A conversation about something the child chose to investigate will sustain longer than one you imposed.

This does not mean abandoning learning intentions. Rather, look for connections between children's interests and your curriculum goals. A child fascinated by dinosaurs might explore scientific concepts through that lens. A child building towers might investigate mathematical concepts through construction.

When children's ideas diverge from your expectations, resist the urge to steer them back. Instead, follow their thinking and look for opportunities to extend it. Their "wrong" answer might reveal interesting reasoning worth exploring.

If a child suggests something incorrect, explore why they think that rather than simply correcting. "That's interesting. What made you think that?" Often, the reasoning contains partial understanding that, once identified, can be built upon.

The EPPE research focused on early years, where sustained shared thinking has particular power. Young children are naturally curious and have not yet learned to wait for adults to provide answers. This makes them excellent partners in shared inquiry.

During play, position yourself alongside children rather than opposite them. Engage with the same materials they are using. Wonder aloud about what you notice. Let them guide exploration while you contribute observations and questions.

As children grow, sustained shared thinking remains valuable but requires adaptation. Older children may expect teachers to have answers and may be reluctant to offer speculative ideas. Create classroom cultures where tentative thinking is valued.

Use "think alouds" during teaching to model ongoing reasoning. Engage in genuine problem-solving with students, not just demonstrating solved problems. Create investigation tasks where you genuinely do not know what students will discover.

Subject complexity in secondary schools offers rich territory for sustained shared thinking. Introduce problems that experts genuinely debate. Engage students in reasoning about ambiguous evidence or competing interpretations.

Seminar-style discussions, philosophical inquiry, and collaborative investigation all create space for sustained shared thinking. The key is positioning yourself as a more experienced thinker rather than an authority with answers.

Sustained shared thinking need not be lengthy. Brief moments of genuine intellectual partnership accumulate. Look for opportunities during transitions, alongside routine activities, or in small group work. Quality matters more than duration.

This expectation reflects classroom culture, not child nature. Explicitly value questions over answers. Respond to questions with "What do you think?" more often than with explanations. Celebrate uncertainty and exploration.

Preparation helps. For topics you will teach, consider what genuine puzzles exist. What do experts debate? What might children find surprising? Have a repertoire of general prompts ready: "Why do you think...?", "What would happen if...?", "How else could we...?"

Start where children are. Some need confidence before contributing to shared thinking. Begin with topics they know well, acknowledge their expertise, and gradually extend into new territory. Pair reluctant talkers with supportive peers.

Questions matter, but not all questions support sustained shared thinking. Research distinguishes between questions that close down thinking (seeking specific answers) and questions that open up thinking (inviting exploration).

Effective questioning in sustained shared thinking:

Avoid questions that:

The best "questions" are often not grammatically questions at all. "I wonder..." statements, expressions of puzzlement, and invitations to observe all prompt thinking without demanding correct answers.

Sustained shared thinking aligns with several established pedagogical approaches:

scaffolding-in-education-a-teachers-guide"> Scaffolding involves supporting learners to achieve more than they could independently. Sustained shared thinking is a form of intellectual scaffolding where adult thinking processes support child thinking.

Dialogic teaching emphasises purposeful, cumulative dialogue where ideas build over time. Sustained shared thinking exemplifies dialogic principles.

Inquiry-based learning positions children as investigators constructing understanding. Sustained shared thinking supports inquiry by modelling investigative thinking.

Co-construction in Vygotskian theory involves knowledge being built through social interaction. Sustained shared thinking is co-construction in action.

A child is building a tower that keeps falling. Instead of explaining how to build more stably, the adult sits alongside and says: "I notice it keeps falling when you add that block. I wonder why..." The child suggests the tower is too skinny. Together, they explore: "What could we try?" The child proposes making the base wider. They experiment, observe, discuss what they notice, and try different approaches.

A child notices their shadow is longer in the afternoon than at lunchtime. The adult responds: "That's interesting. I wonder why that might be... Together, they watch the sun's position, think about links between sun height and shadow length, and plan ways to test their ideas. Neither holds the full answer; both contribute to developing understanding.

Secondary students are studying a historical figure's controversial choice. The teacher poses it as a genuine dilemma: "I've read arguments on both sides, and I'm genuinely uncertain what I would have done." Students offer perspectives. The teacher offers counter-considerations. Ideas are challenged and refined. The conversation sustains because genuine intellectual engagement exists.

Is sustained shared thinking the same as Socratic questioning?

There are similarities, but Socratic questioning often involves the teacher knowing the answer and leading students towards it. Sustained shared thinking is more genuinely collaborative, with both parties contributing to developing understanding.

How do I assess whether sustained shared thinking is happening?

Record and review interactions. Look for the characteristics described above: mutual contribution, developing ideas, genuine uncertainty, exploratory language, emotional engagement. Coding frameworks from the EPPE research can guide assessment.

Can sustained shared thinking happen between children?

Yes. When children genuinely collaborate on intellectual problems, building on each other's ideas over time, sustained shared thinking is occurring. Adults can set up conditions that promote this.

How often should sustained shared thinking happen?

The EPPE research found that even relatively infrequent episodes had significant impact. Aim for quality moments rather than arbitrary frequency targets. Several genuine episodes per day in early years, regularly during teaching at later stages.

Sustained shared thinking transforms the relationship between teachers and learners. Instead of knowledge transfer from expert to novice, it creates intellectual partnership where both participants contribute, explore, and learn together. The research evidence for its impact is strong, and the approach aligns with broader understanding of how learning works.

Begin by noticing opportunities for genuine shared inquiry. When a child wonders about something, wonder alongside them. When a student raises a puzzling question, explore it together rather than simply answering. Over time, these moments of sustained shared thinking will accumulate, building both understanding and the disposition to think deeply.

These peer-reviewed studies provide deeper insights into sustained shared thinking: a teacher's guide to deeper learning conversations and its application in educational settings.

Siraj‐Blatchford et al. (2009)

This paper examines how teachers can support children's learning through play using Vygotskian theories, with a specific focus on sustained shared thinking pedagogies in early childhood education. It provides teachers with theoretical frameworks for understanding how meaningful interactions during play can promote deeper learning and cognitive development in young children.

Blatchford et al. (2018)

This research investigates how classroom factors like class size, student groupings, and teacher interactions affect learning outcomes, particularly for students with special educational needs and disabilities. It offers teachers practical insights into how classroom organisation and management decisions can influence the quality of learning conversations and sustained interactions with all students.

Blatchford et al. (2001)

This study explores the relationships between class size and how teachers organise students into different groupings within classrooms. It provides teachers with evidence-based guidance on creating optimal classroom contexts that support meaningful peer interactions and sustained shared thinking opportunities.

Sylva et al. (2010)

This thorough research project provides evidence about what makes early childhood education effective, drawing from longitudinal studies of children's development and learning outcomes. It offers teachers research-backed insights into the practices and interactions that promote sustained learning, including the importance of quality adult-child conversations in educational settings.

Blatchford et al. (2011)

This study examines how different class sizes affect the quality and frequency of teacher-student interactions and overall classroom engagement across primary and secondary schools. It provides teachers with evidence about how structural classroom factors influence their ability to engage in sustained shared thinking and meaningful learning conversations with students.

Generate a progressive oracy implementation plan with talk protocols, sentence stems, and assessment checkpoints for your key stage.

These peer-reviewed studies provide the research foundation for the strategies discussed in this article:

Language View study ↗

1 citations

Lei Wu & Kamariah Abu Bakar (2025)

This thorough study examined how teachers in China, the United States, and the UK use scaffolding techniques to support early readers, revealing significant cultural differences in how educators apply

AI AS A DIGITAL SCAFFOLD: AN INTEGRATIVE REVIEW OF VYGOTSKY'S View study ↗

1 citations

Wan Hazwani Wan Hamedi et al. (2025)

This review examines how artificial intelligence tools can function as digital teaching assistants that provide personalised support within students' zones of proximal development, much like human teachers do through scaffolding. The research reveals that current AI educational technologies show promise but still lack the nuanced understanding and relationship-building that characterize effective human scaffolding. Teachers interested in educational technology will gain insights into how AI tools might complement, rather than replace, the sustained shared thinking conversations that drive deep learning.

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/sustained-shared-thinking-teachers-guide#article","headline":"Sustained Shared Thinking: A Teacher's Guide to Deeper Learning Conversations","description":"Extend children's learning through meaningful dialogue and open questions. A practical guide to Sustained Shared Thinking strategies for early years.","datePublished":"2026-01-21T18:32:36.450Z","dateModified":"2026-02-11T13:17:34.556Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/sustained-shared-thinking-teachers-guide"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/69729d7bb45fe049a4f1229c_69711bc4544918810f2e53c6_69711b4aec9e13396f36b8a8_sustained-shared-thinking-a-te-definition-1769020234067.webp","wordCount":2795},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/sustained-shared-thinking-teachers-guide#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"Sustained Shared Thinking: A Teacher's Guide to Deeper Learning Conversations","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/sustained-shared-thinking-teachers-guide"}]}]}