Memory Consolidation: How the Brain Transforms Learning into Lasting Knowledge

Discover how memory consolidation transforms fragile learning into stable knowledge, plus evidence-based classroom strategies to support this process.

Discover how memory consolidation transforms fragile learning into stable knowledge, plus evidence-based classroom strategies to support this process.

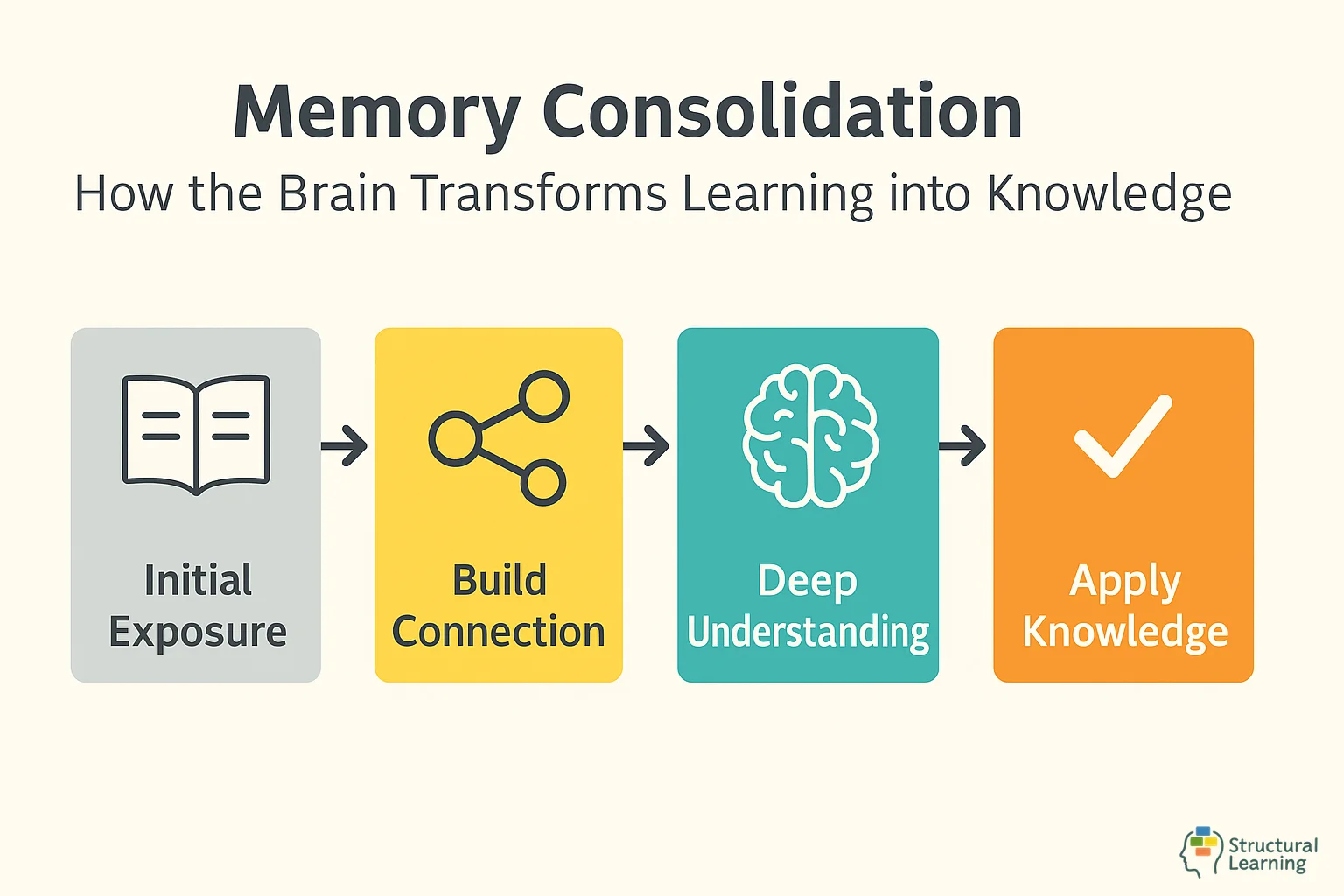

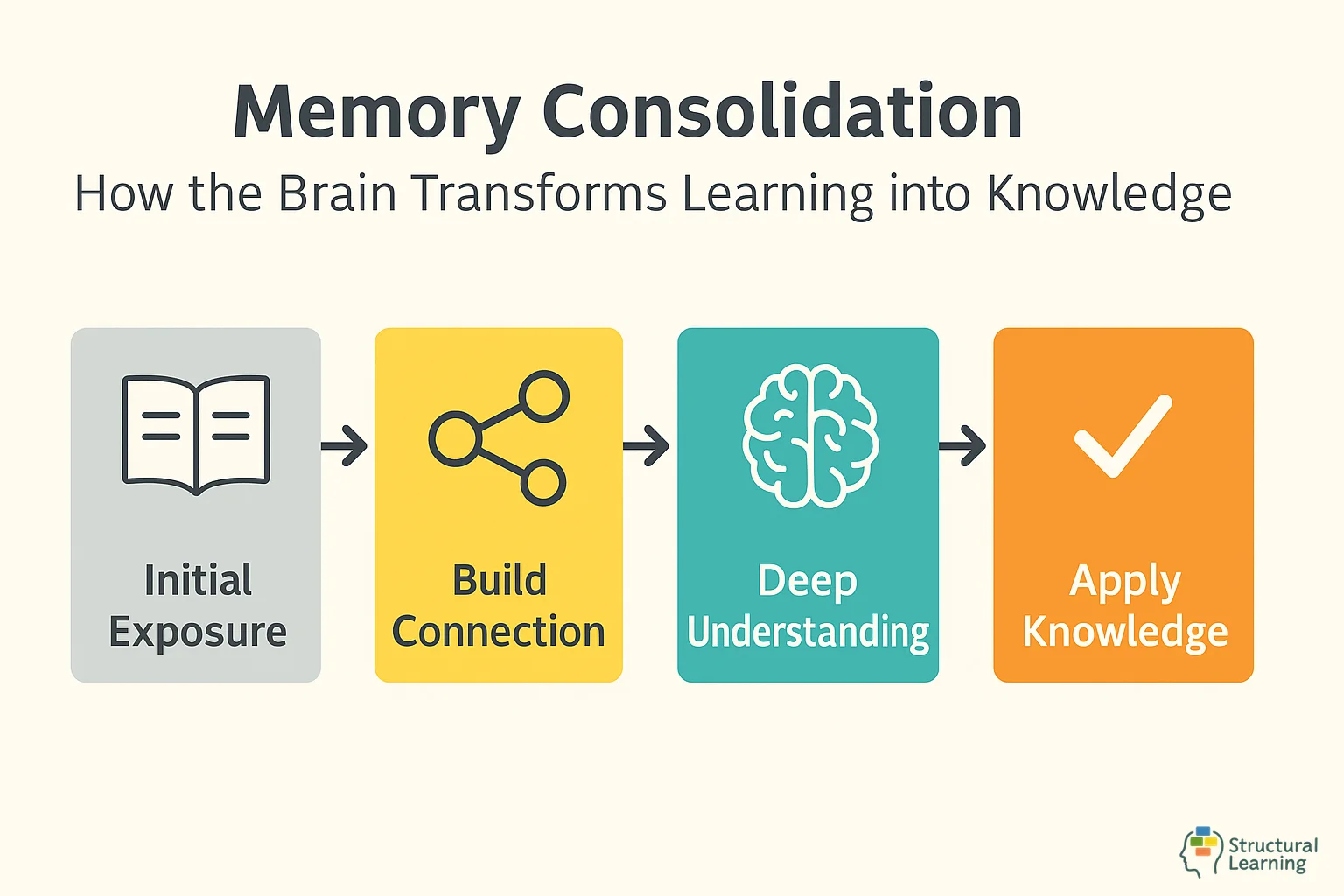

Memory consolidation is the remarkable neurobiological process that transforms fragile, newly acquired information into stable, long-term memories your brain can retrieve years later. This intricate mechanism occurs when neural pathways strengthen and reorganise, shifting memories from temporary storage in the hippocampus to permanent networks distributed across the cortex. Without consolidation, every lesson learnt, skill practised, and experience gained would fade within hours or days. Understanding how your brain accomplishes this transformation holds the key to making any learning truly stick.

The missing piece is memory consolidation, the biological process that transforms newly acquired information into stable, long-term memories. Without consolidation, learning remains fragile and easily disrupted. Understanding this process gives teachers insight into why some instructional practices produce lasting learning while others lead to rapid forgetting, and helps develop students' metacognitive awarenessand self-regulated learning skills.

Research over the past two decades has revealed that consolidation isn't passive. Specific brain processes during and after learning actively strengthen memory traces and integrate new information with existing knowledge . Teachers who understand these processes can structure instruction, practise, and even homework timing alongside evidence-based memory strategiesto support more durable learning.

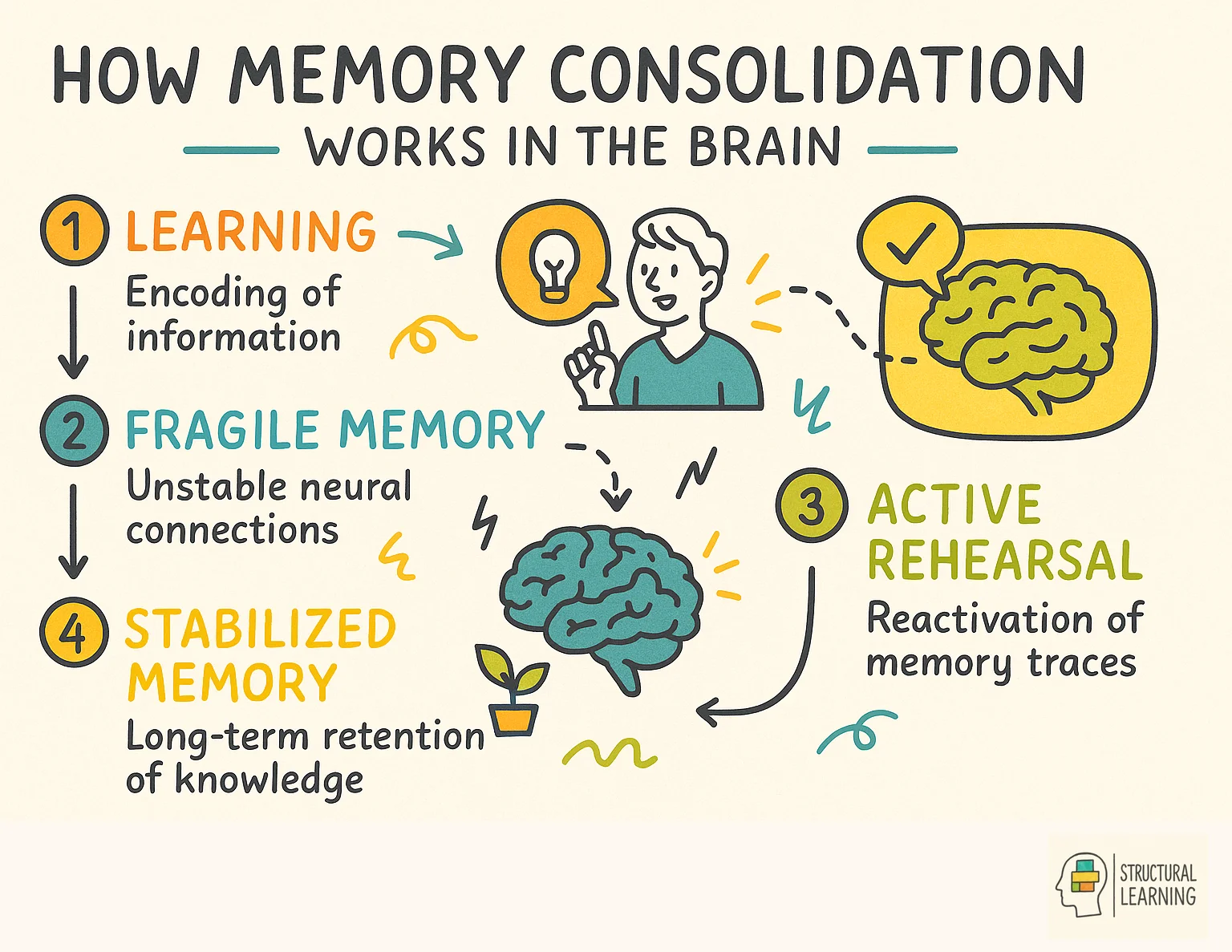

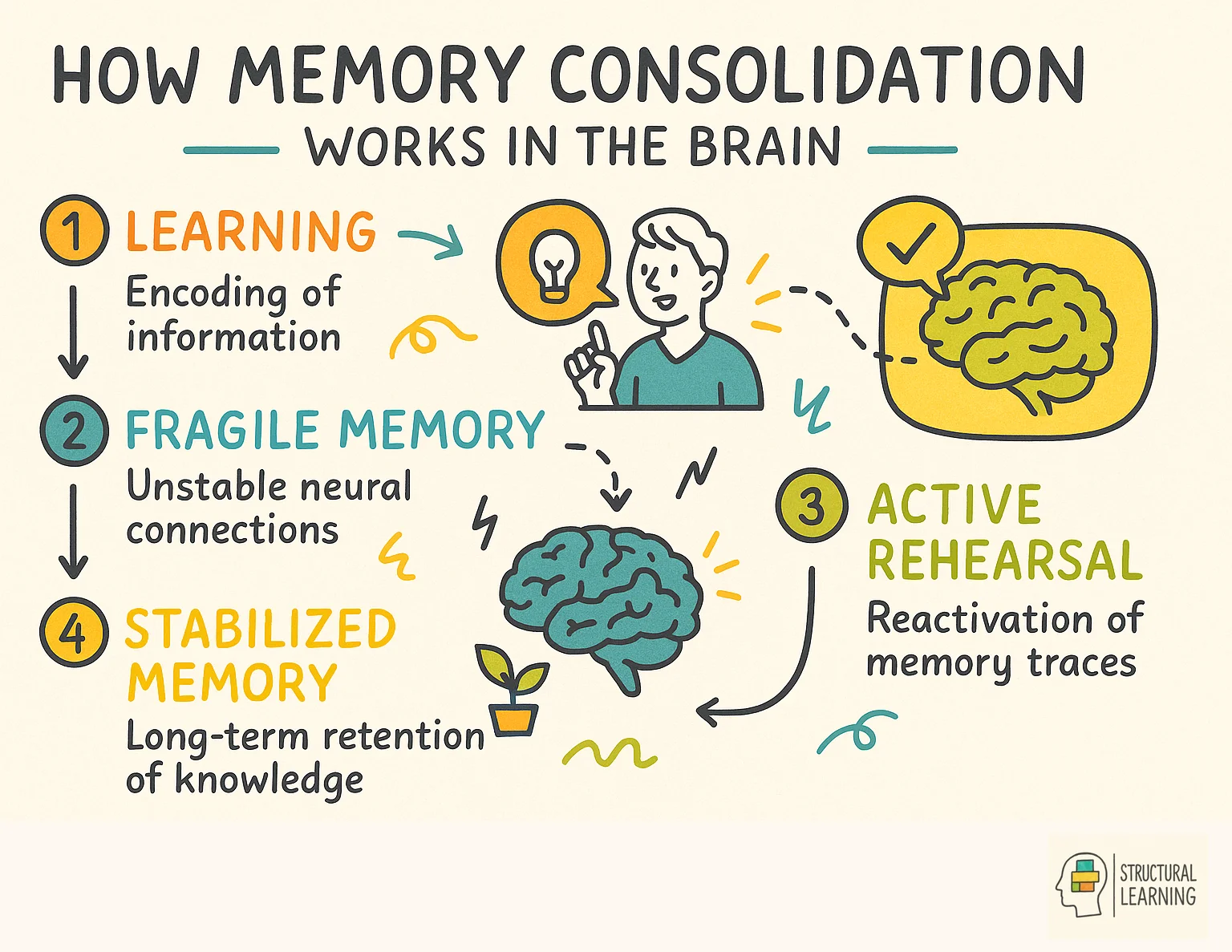

Memory consolidation refers to the neurobiological processes that stabilise newly formed memories, making them resistant to forgetting and interference. When you first learn something, the memory exists in a vulnerable state, temporarily held in working memory before consolidation begins. Consolidation gradually transforms this fragile trace in to a stable, long-lasting memory.

| Process | Timeframe | Brain Activity | Teaching Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Encoding | Immediate | Hippocampus activation | Multi-sensory input, attention focus |

| Synaptic consolidation | Minutes to hours | Protein synthesis | Spaced practice, avoid interference |

| Systems consolidation | Days to weeks | Hippocampus to cortex transfer | Regular review, sleep importance |

| Reconsolidation | Upon retrieval | Memory updating | Retrieval practice, error correction |

| Long-term storage | Months to years | Distributed cortical networks | Interleaving, varied contexts |

The process occurs across two timescales.

Synaptic consolidation happens within hours of learning. New protein synthesis strengthens the connections between neurons that encode the memory. This cellular-level stabilisation begins immediately and continues for several hours.

Systems consolidation unfolds over days to weeks. Memories initially dependent on the hippocampus gradually become represented in neocortical networks. This redistribution creates more stable, long-term storage for declarative memory, the explicit knowledge and facts that students need to retain. This process integrated representations that can exist independently of the hippocampus.

For teachers, the practical implication is clear: learning doesn't end when the lesson finishes. The brain continues processing and strengthening memories long after students leave the classroom.

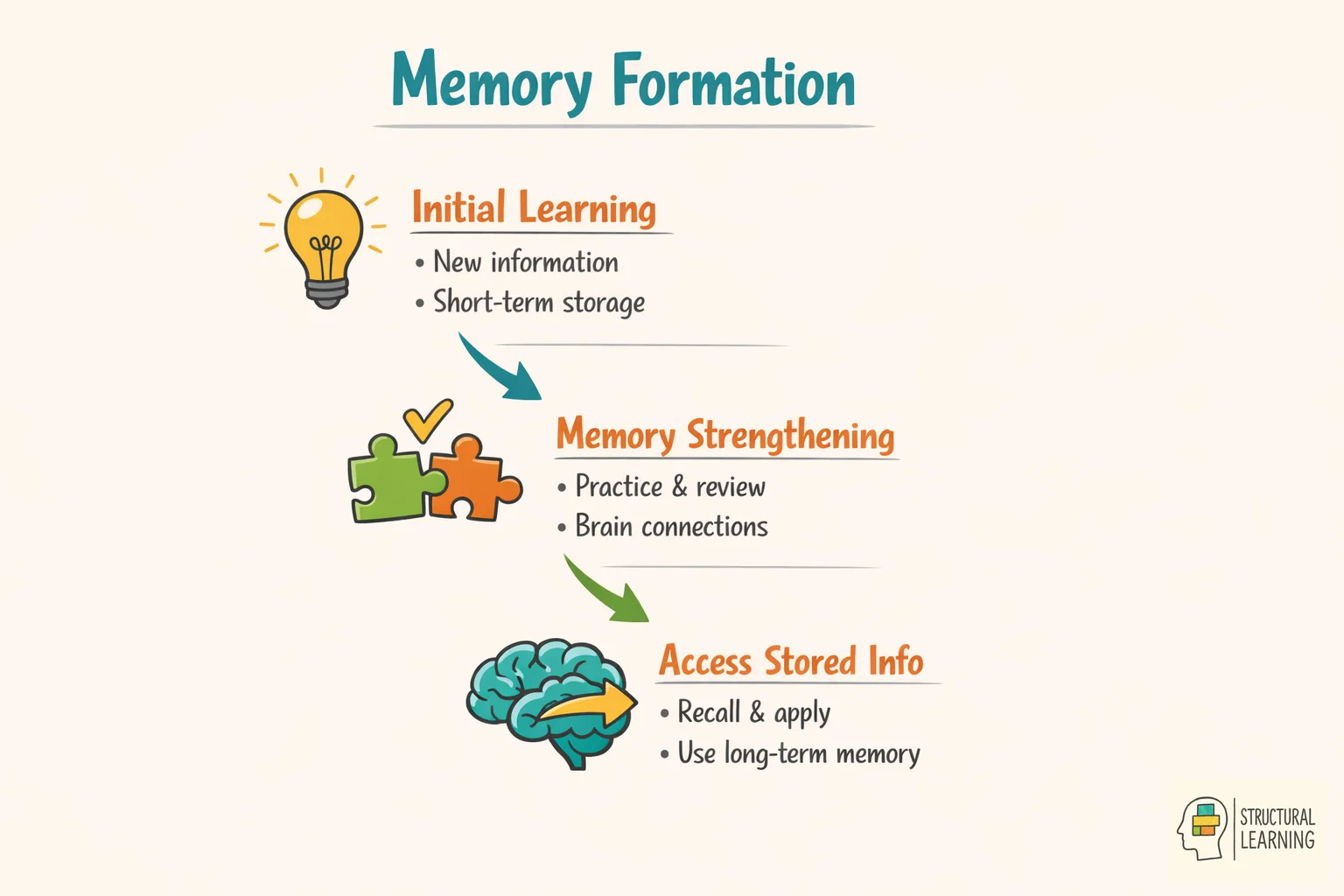

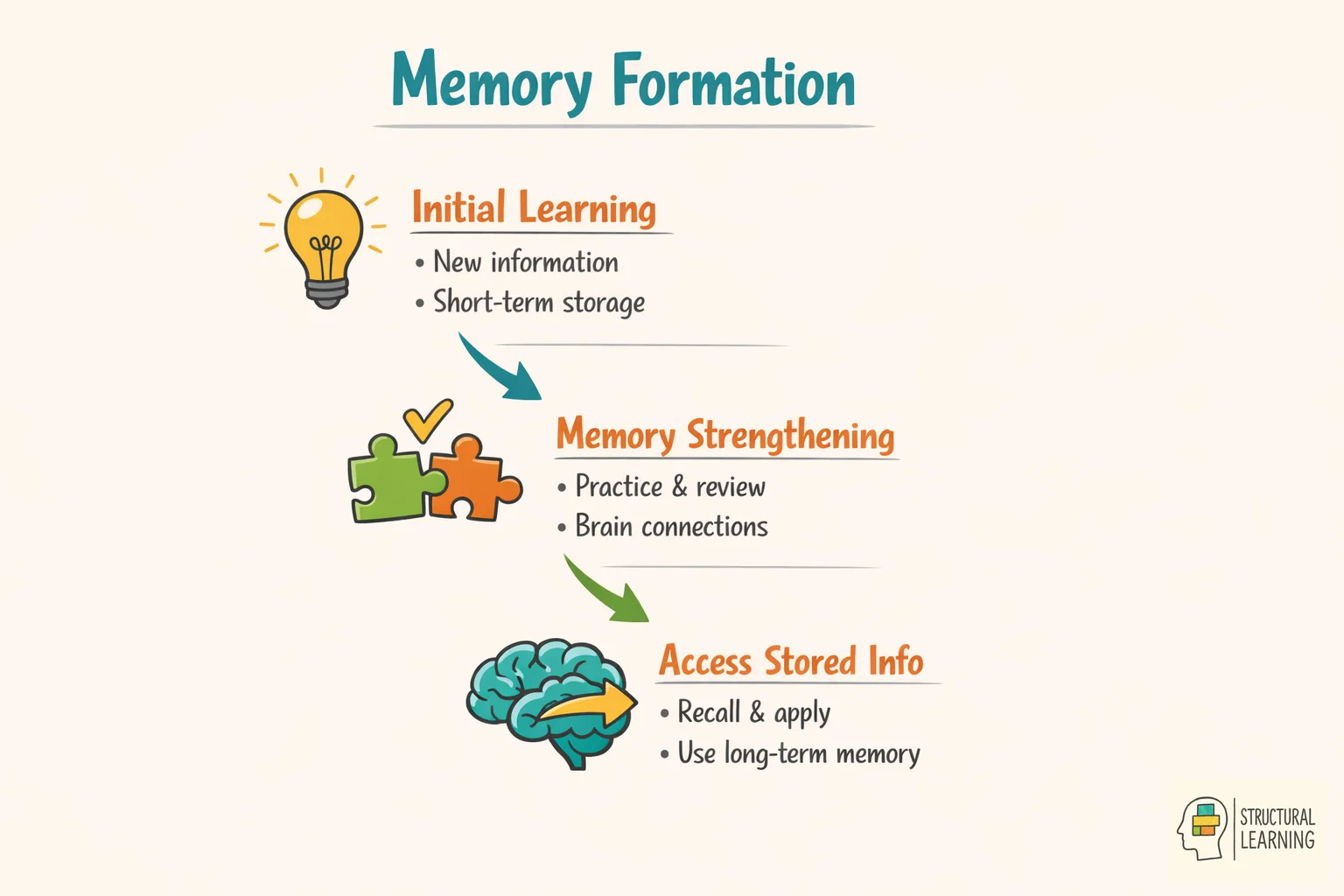

The three stages are encoding (initial learning), consolidation (stabilizing the memory), and retrieval (accessing stored information). Encoding creates a temporary memory trace in working memory, consolidation strengthens and transfers it to long-term storage over hours to weeks, and retrieval reactivates the stored memory.

Understanding memory consolidation requires placing it within the broader context of memory formation. Three stages characterise how experiences become lasting memories.

Encoding is the initial registration of information. During encoding, sensory experiences are transformed into neural representations. The quality of encoding determines what information enters the consolidation pipeline.

Effective encoding requires attention, meaningful processing, and connection to existing knowledge. Research on working memory highlights how encoding depends on limited cognitive resources that can be improved through instructional design.

Consolidation follows encoding, stabilising and strengthening memory traces. This process can be enhanced or impaired by various factors including sleep, stress, and subsequent learning experiences.

Crucially, consolidated memories aren't simply stored copies of original experiences. During consolidation, memories are reorganised, integrated with existing knowledge, and sometimes abstracted into more general patterns.

Retrieval is the process of accessing stored information. Successfully retrieving a memory doesn't just demonstrate learning; it further strengthens the memory trace through a process called reconsolidation.

This explains why retrieval practise is such a powerful learning strategy. Each successful retrieval triggers reconsolidation, making the memory even more stable.

Sleep plays an essential role in memory consolidation by allowing the brain to replay and strengthen neural connections formed during learning. Both REM and non-REM sleep stages contribute to consolidating different types of memories, with slow-wave sleep particularly important for declarative knowledge. Students who get adequate sleep after learning show significantly better retention compared to those who are sleep-deprived.

Perhaps no finding in memory research has more practical importance than the role of sleep in consolidation. Sleep isn't merely the absence of interference; it actively strengthens and reorganises memories.

Different sleep stages support consolidation of different memory types.

Slow-wave sleep (SWS), the deepest stage of non-REM sleep, preferentially supports consolidation of declarative memories: the facts and events that constitute much school learning. During SWS, the hippocampus "replays" recent experiences, gradually transferring representations to neocortical networks.

Research update: While this general pattern is supported by research, recent studies (including a 2024 study in Sleep Medicine) suggest the relationship is more complex than a simple one-to-one mapping. Both sleep stages appear to contribute to different aspects of memory consolidation, and the precise mechanisms continue to be refined by ongoing research.

REM sleep supports consolidation of procedural memories, including motor skills and implicit learning. Students learning physical skills, musical instruments, or procedures benefit from REM sleep following practise.

Both SWS and REM sleep contribute to memory consolidation, though their relative importance depends on what type of material is being learned.

The timing of sleep relative to learning affects consolidation. Research by Gais and colleagues found that sleep within three hours of learning produces better retention than sleep delayed by ten hours. This suggests that studying new material in the evening, followed by a full night's sleep, may be more effective than morning study followed by an active day.

Practical implications for homework timing emerge from this research. New or challenging material assigned as evening homework may benefit from overnight consolidation before the next lesson. Review of previously learned material might be better suited to morning assignments.

Teenagers face a particular challenge: their biological clocks shift towards later sleep and wake times just as school schedules demand early starts. This mismatch between biological rhythms and school timing means many adolescents experience chronic sleep restriction that impairs memory consolidation.

Teachers cannot solve this structural problem, but understanding it helps explain why some students struggle with retention despite apparent understanding during lessons. Supporting students in understanding the importance of sleep for learning may encourage better sleep habits.

Active Systems Consolidation Theory proposes that memories are actively reorganized during sleep through coordinated activity between the hippocampus and neocortex. During sleep, the hippocampus repeatedly reactivates memory traces from the day, gradually transferring them to cortical networks for long-term storage. This process explains why sleep between learning sessions enhances memory retention and integration with existing knowledge.

The dominant theoretical framework for understanding memory consolidation is active systems consolidation theory, developed primarily by Jan Born and colleagues.

This theory proposes that during sleep, the hippocampus repeatedly reactivates recent memory traces. Each reactivation strengthens cortical representations while gradually reducing hippocampal dependence. Over time, memories become independent of the hippocampus and fully integrated into cortical knowledge networks.

Brain imaging studies support this account. Regions active during learning are reactivated during subsequent sleep. The degree of reactivation predicts later memory strength. This isn't passive maintenance; it's active processing that transforms and strengthens memories.

For teachers, this theory reinforces the importance of creating meaningful initial learning experiences. Memories that are strongly encoded and connected to existing knowledge will be preferentially consolidated during sleep.

When students retrieve a memory, it temporarily becomes labile (unstable) and must undergo reconsolidation to be restored. This reconsolidation window provides an opportunity to update, strengthen, or modify the memory through additional learning or practise. Teachers can use reconsolidation by incorporating retrieval practise that allows students to strengthen and refine their understanding.

A fascinating discovery is that consolidated memories can become temporarily unstable when retrieved. This process, called reconsolidation, has significant implications for education.

Each retrieval event triggers reconsolidation, which can strengthen the memory. This explains part of why retrieval practise is so effective: it doesn't just measure memory but actively modifies and strengthens it through reconsolidation.

Reconsolidation provides a window for modifying incorrect memories. When students retrieve a misconception and are immediately provided with correct information, the reconsolidation process may integrate the correction into the updated memory.

This has implications for addressing misconceptions. Rather than simply providing correct information, triggering retrieval of the misconception first may facilitate correction through reconsolidation.

High cognitive load during initial learning can impair memory consolidation by overwhelming working memor y capacity and preventing effective encoding. When students process too much information at once, their brains struggle to form strong initial memory traces that can be consolidated. Teachers should manage cognitive load by breaking complex topics into smaller chunks and providing adequate processing time between new concepts.

Cognitive load theory focuses primarily on encoding, but consolidation considerations extend its implications.

Effective consolidation requires effective encoding. If cognitive load during instruction exceeds working memory capacity, encoding suffers, and there's less to consolidate. Managing cognitive load during instruction supports better consolidation downstream.

The period immediately after learning appears important for consolidation. Research suggests that mentally rehearsing or elaborating on recently learned material strengthens consolidation. Brief reflection periods after instruction may support this process.

Sleep deprivation impairs both encoding through reduced attention and consolidation through insufficient sleep-dependent memory processing. Students who are sleep deprived face a double challenge in learning.

Effective strategiesinclude spaced practise sessions, interleaving different topics, and incorporating retrieval practise through low-stakes quizzing. Teachers should also time homework to allow for sleep-based consolidation and avoid introducing similar content that might cause interference. Building in reflection time at the end of lessons helps initiate the consolidation process before students leave class.

Understanding consolidation suggests several practical classroom strategies.

Assign new or challenging material as evening homework when possible. This positions new learning close to sleep, maximising the opportunity for overnight consolidation.

Begin lessons with review of previously learned material. This retrieval practise strengthens those memories through reconsolidation while activating relevant schemas that support encoding of new content.

Include brief pauses after presenting new concepts. These moments allow initial synaptic consolidation to begin and give students opportunity to make connections with existing knowledge.

Help students understand the connection between sleep and learning. This is particularly important for older students who may undervalue sleep in favour of late-night studying.

Avoid teaching highly similar concepts in consecutive lessons. Allow consolidation time between related but potentially confusable content.

Rather than testing only recent content, include material from earlier in the course. This requires retrieval of previously consolidated material, strengthening it further.

Help students plan revision that distributes practise over time rather than cramming. Connect this to their understanding of how consolidation works.

Declarative memories (facts and concepts) consolidate primarily during slow-wave sleep and rely heavily on hippocampal-neocortical interactions. Procedural memories (skills and procedures) consolidate during REM sleep and involve motor cortex and striatal regions. Teachers should consider these differences when scheduling practise for different subjects, with conceptual material benefiting from immediate review and procedural skills from distributed practise.

Different types of learning may consolidate through somewhat different mechanisms.

Facts and concepts (declarative memory) rely heavily on sleep-dependent consolidation involving hippocampal-neocortical dialogue. The classroom focus on declarative knowledge makes sleep particularly important for school learning.

Skills and procedures (procedural memory) consolidate through repetition and practise, with sleep, particularly REM sleep, playing a role in offline gains. Students learning procedures should expect improvement after sleep, even without additional practise.

Learning to make perceptual distinctions, such as recognising patterns or distinguishing sounds, shows sleep-dependent consolidation. Students learning to recognise scientific specimens, musical intervals, or language sounds benefit from overnight consolidation.

Individual differences in memory consolidation stem from factors including sleep quality, stress levels, prior knowledge, and neurobiological variations. Students with better sleep habits, lower stress, and stronger foundational knowledge typically show more effective consolidation. Teachers can address these differences by providing multiple consolidation opportunities and teaching students about factors that influence their memory formation.

Students vary in their consolidation efficiency, affecting learning outcomes.

Children show strong sleep-dependent memory consolidation, often even stronger than adults. However, they require more sleep overall. Adolescents face the challenge of shifted biological clocks combined with early school starts.

Students with sleep disorders, inconsistent sleep schedules, or insufficient sleep quantity show impaired consolidation. These students may understand material in class but show poor retention.

Students with more relevant prior knowledge consolidate new information faster because they have existing schemas to integrate it with. This creates cumulative advantages for students who build strong knowledge foundations.

Emotional arousal during learning enhances memory consolidation through the release of stress hormones and increased amygdala activity. Moderately positive emotions create optimal conditions for consolidation, while extreme stress or negative emotions can impair the process. Teachers can use this by creating emotionally engaging but supportive learning environmentsthat enhance memory formation without causing anxiety.

Emotional experiences are consolidated differently from neutral ones. Moderate emotional arousal enhances consolidation, while extreme stress can impair it.

Some emotional engagement with learning supports consolidation. Complete boredom reduces encoding quality, while overwhelming stress impairs both encoding and consolidation. The moderate challenge of desirable difficulties may hit an optimal arousal level.

Chronic stress and anxiety impair memory consolidation. Students experiencing significant stress may struggle with retention despite adequate understanding during lessons.

Teachers can support struggling students by providing more frequent review opportunities, teaching explicit memory strategies, and ensuring adequate processing time during lessons. Additional scaffolds include visual organisers, mnemonic devices, and structured note-taking systems that facilitate initial encoding. Creating predictable routines and reducing cognitive load through clear organisation also helps students with consolidation challenges.

Some students may show particular difficulties with memory consolidation.

Students reporting sleep difficulties may need support in improving sleep habits. For some, referral to health services may be appropriate. Teachers can accommodate by providing more distributed practise opportunities and reducing reliance on single learning episodes.

Students with attention challenges may have encoding difficulties that limit what enters consolidation. Strategies supporting attention during instruction indirectly support consolidation.

Students with working memory difficulties may struggle with the initial encoding that precedes consolidation. Breaking content into smaller chunks and providing external supports, such as notes or graphic organisers, helps ensure adequate encoding.

Spaced practise allows time for memory consolidation to occur between learning sessions, strengthening neural pathways and reducing forgetting. Each spaced review session triggers reconsolidation, which further strengthens the memory trace and promotes long-term retention. Massed practise prevents consolidation between repetitions, leading to weaker memory formation despite the immediate appearance of mastery.

The benefits of spaced practise can be partly understood through consolidation. When practise is distributed over time, consolidation occurs between sessions. Each subsequent practise session retrieves and reconsolidates the partially consolidated memory, strengthening it further.

Massed practise, by contrast, doesn't allow consolidation between repetitions. The memory remains in an unstable state throughout the practise session and only begins consolidating when practise ends.

This explains why the same total practise time produces better retention when distributed rather than massed. Spacing allows the consolidation processes that strengthen memories and protect them from forgetting.

Teachers can translate consolidation research into practise by structuring lessons with built-in consolidation time, scheduling reviews to coincide with consolidation windows, and educating students about memory processes. Practical applications include ending lessons with summary activities, assigning reflective homework before sleep, and using next-day warm-ups to reactivate previous learning. Understanding the biological basis helps teachers make evidence-informed decisions about timing and sequencing instruction.

Memory consolidation represents a bridge between neuroscience and educational practise. While teachers cannot directly manipulate brain processes, understanding consolidation helps explain why certain practices work and suggests refinements to instructional timing and structure.

The key insight is that learning continues after lessons end. The period following instruction, particularly sleep, plays an active role in converting understanding into lasting knowledge. Teachers who structure instruction, practise, and assessment with consolidation in mind create conditions for more durable learning.

Practically, this means spacing rather than massing practise, positioning new learning to maximise sleep consolidation, building retrieval practise into routines, and teaching students about how their memory works.

Essential papers include Dudai's reviews on consolidation theory, Rasch and Born's work on sleep and memory, and Roediger's research on retrieval practise and consolidation. These foundational works provide accessible explanations of consolidation mechanisms and their educational implications. Teachers can also explore practical guides that translate neuroscience findings into classroom applications.

The following papers provide deeper exploration of memory consolidation and its educational implications.

This comprehensive review established the critical role of sleep in memory consolidation. The authors synthesise evidence from behavioural, brain imaging, and neurophysiological studies to argue that sleep actively processes memories rather than simply preventing interference. Essential reading for understanding sleep's role in learning.

This Nature Reviews Neuroscience article provides an authoritative account of active systems consolidation theory. The authors explain how hippocampal-neocortical dialogue during sleep transforms memories from temporary hippocampal representations to stable neocortical networks.

This practical review translates consolidation research into recommendations for learning and education. The author addresses questions about optimal sleep timing, napping, and how understanding consolidation can improve study strategies.

This review examines reconsolidation, the process by which retrieved memories become labile and can be modified. The paper discusses implications for updating memories and correcting errors, with relevance to addressing misconceptions in educational contexts.

This study demonstrates sleep-dependent consolidation in a learning context relevant to education. Participants showed improved speech recognition after sleep but not after equivalent time awake, illustrating the active role of sleep in perceptual learning.

Memory consolidation operates through two distinct yet interconnected processes: synaptic consolidation and systems consolidation. Synaptic consolidation occurs within hours of learning, as proteins synthesise to strengthen connections between neurons. This process explains why revision immediately after a lesson proves more effective than waiting until the evening; the neural pathways remain active and receptive to reinforcement.

Systems consolidation unfolds over weeks and months, gradually shifting memories from the hippocampus to the neocortex. During this transfer, memories become integrated with existing knowledge networks, creating the rich, interconnected understanding that characterises expert thinking. Brain imaging studies reveal that well-consolidated memories activate broader cortical regions, suggesting they become woven into multiple knowledge structures.

Teachers can support these neurobiological processes through strategic instructional design. Spacing practise sessions across days or weeks aligns with systems consolidation timelines, allowing the brain to repeatedly reactivate and strengthen memory traces. For instance, introducing key vocabulary on Monday, revisiting it through different activities on Wednesday, and applying it in context on Friday creates multiple consolidation opportunities.

Sleep plays a crucial role in both consolidation stages. During slow-wave sleep, the hippocampus replays learning experiences, strengthening synaptic connections. REM sleep then integrates these memories with existing knowledge. This research validates homework timing; assignments completed earlier in the evening allow proper sleep consolidation, whilst late-night cramming disrupts these essential processes.

Understanding these mechanisms helps teachers make evidence-based decisions about curriculum pacing, homework design, and revision strategies. Rather than fighting against the brain's natural consolidation rhythms, effective teaching works in harmony with these biological processes to create lasting learning.

Memory consolidation occurs through two distinct but interconnected processes: synaptic consolidation and systems consolidation. Understanding both helps teachers design more effective learning experiences that work with, rather than against, how the brain naturally stores information.

Synaptic consolidation happens first, typically within minutes to hours after learning. During this process, connections between neurons strengthen through repeated activation and protein synthesis. This explains why immediate review activities are so powerful; when students revisit new material within the same lesson or shortly afterwards, they're supporting these cellular-level changes. For instance, ending a maths lesson with a quick problem-solving session reinforces the synaptic changes initiated during instruction.

Systems consolidation unfolds over weeks, months, or even years. Here, memories gradually reorganise, shifting from temporary storage in the hippocampus to more permanent residence across the cortex. This process explains why spaced practise works so effectively. When students encounter previously learnt material after days or weeks, they're not just reviewing; they're facilitating the brain's natural tendency to redistribute and strengthen memory networks.

Teachers can support both processes through strategic planning. For synaptic consolidation, incorporate brief retrieval practise within lessons, such as having students explain a concept to a partner immediately after teaching it. For systems consolidation, design curriculum spirals that revisit key concepts at increasing intervals. A science teacher might introduce photosynthesis in September, return to it when teaching ecosystems in November, and connect it to carbon cycles in February.

Research by Dudai (2004) and Frankland & Bontempi (2005) shows that respecting both consolidation timescales dramatically improves retention. By aligning teaching methods with these biological processes, educators help ensure that today's lessons become tomorrow's accessible knowledge.

Sleep isn't just rest for tired bodies; it's when your brain actively transforms the day's learning into lasting memories. During sleep, particularly deep slow-wave sleep and REM phases, the brain replays and reorganises information acquired during waking hours. This nocturnal processing strengthens neural connections, transfers memories from temporary to permanent storage, and integrates new knowledge with existing understanding.

Research by Walker and Stickgold (2006) demonstrates that students who sleep after learning perform significantly better on tests than those who stay awake, even when total study time remains identical. The hippocampus, which temporarily stores new memories, communicates with the cortex during sleep, gradually shifting information into long-term storage networks. Without adequate sleep, this transfer process falters, leaving memories vulnerable to decay.

Teachers can harness sleep's power through strategic planning. Schedule challenging new concepts early in the school day, allowing maximum time for consolidation before students sleep. When teaching complex procedures or problem-solving methods, encourage students to review notes briefly before bedtime; this 'sleep to remember' strategy enhances overnight consolidation. For revision periods, advise students to spread learning across multiple days rather than cramming, ensuring each study session benefits from sleep-dependent consolidation.

Consider adjusting homework patterns too. Rather than assigning heavy practise immediately after teaching, introduce new concepts, provide light initial practise, then assign deeper practise the following day after consolidation has begun. This approach respects the brain's natural learning rhythms and produces more durable understanding. Even a 20-minute classroom nap after intensive learning can boost memory retention, though this remains impractical in most school settings.

Memory consolidation is the neurobiological process that transforms newly learned information from a fragile, temporary state into stable, long-term memories that resist forgetting. Teachers should care because understanding this process explains why students can understand material perfectly during lessons but forget it days later, and helps educators time instruction and practise more effectively to support lasting learning.

Memory consolidation occurs across two timescales: synaptic consolidation happens within hours of learning as protein synthesis strengthens neural connections, whilst systems consolidation unfolds over days to weeks as memories transfer from the hippocampus to more stable cortical networks. This means the brain continues processing and strengthening memories long after students leave the classroom.

Research suggests that new or challenging material should be assigned as evening homework, as sleep within three hours of learning produces better retention than delayed sleep. Review of previously learned material might be better suited to morning assignments, allowing students to benefit from overnight memory consolidation before tackling new concepts.

During sleep, particularly slow-wave sleep, the hippocampus actively 'replays' recent learning experiences and gradually transfers them to cortical networks for long-term storage. Students who get adequate sleep after learning show significantly better retention compared to sleep-deprived students, as both REM and non-REM sleep stages contribute to consolidating different types of memories.

Teenagers' biological clocks naturally shift towards later sleep and wake times, but early school schedules create chronic sleep restriction that impairs memory consolidation. Whilst teachers cannot solve this structural problem, they can help students understand the importance of sleep for learning and potentially adjust homework timing to work with rather than against natural sleep patterns.

When students successfully retrieve information from memory, it doesn't just demonstrate learning but actually triggers reconsolidation, making the memory even more stable and resistant to forgetting. This explains why retrieval practise activities like testing and quizzing are such powerful learning strategies, as each successful retrieval strengthens the underlying memory trace.

Teachers should recognise that learning doesn't end when lessons finish, as consolidation continues for hours and days afterwards. This means structuring instruction to support encoding through attention and meaningful connections, timing practise and homework to align with consolidation processes, and using retrieval practise to strengthen memories through reconsolidation.

These peer-reviewed studies provide the research foundation for the strategies discussed in this article:

A Large Language Model-Based System for Socratic Inquiry: Developing Deep Learning and Memory Consolidation View study ↗

3 citations

This recent research demonstrates how AI chatbots can be programmed to ask probing questions in the style of Socratic teaching, helping students think more deeply about material rather than just memorizing fac ts. The system addresses a key challenge teachers face: it's difficult to consistently apply Socratic questioning with every student, but AI can provide personalised, thought-provoking questions that strengthen long-term memory formation. This technology could serve as a powerful teaching assistant, giving educators a new tool to promote deeper understanding and combat the natural forgetting that occurs without proper reinforcement.

Self-regulation, evaluation, and promotion of learning through the practise of memory recovery View study ↗3 citations

L. Oliveira & L. Stein (2018)

This research reveals that frequent low-stakes testing serves a dual purpose: it not only assesses what students know but actually strengthens their memory of the material through activerecall. The authors argue that when teachers shift from viewing tests purely as evaluation tools to seeing them as learning opportunities, students develop better study habits and retain information longer. This approach encourages educators to incorporate more frequent, brief quizzes and self-assessment activities that help students monitor their own learning progress while simultaneously reinforcing their knowledge.

Testing (quizzing) boosts classroom learning: A systematic and meta-analytic review. View study ↗

241 citations

Chunliang Yang et al. (2021)

This comprehensive analysis of over 200 studies involving nearly 50,000 students provides compelling evidence that regular quizzing dramatically improves long-term learning compared to simply re-reading or reviewing notes. The research shows that the testing effect, where retrieving information from memory strengthens retention, works consistently across different subjects, age groups, and classroom settings. For teachers, this means that incorporating frequent, low-pressure quizzes into their routine can be one of the most powerful strategies for helping students retain what they learn, making it far superior to traditional study methods like highlighting or rereading.

Making assessment promote effective learning practices: An example of ipsative assessment from the School of Psychology at UEL View study ↗

5 citations

P. Penn & I. Wells (2018)

Despite strong research showing that self-testing improves memory, most students avoid this study strategy and stick to less effective methods like rereading notes. These researchers solved this problem by designing assessments that require students to practise retrieving information from memory, essentially building the most effective study technique directly into their coursework. This approach shows teachers how to structure assignments and assessments so that students automatically engage in memory-strengthening activities, ensuring they benefit from retrieval practise whether they would choose to use it on their own or not.

Enhancing Student Learning with Flipped Teaching and Retrieval Practise Integration. View study ↗

Chaya Gopalan (2024)

This study compared traditional lecture-based teaching with flipped classrooms and found that combining flipped instruction with regular retrieval practise produced the highest student performance scores. Students in both flipped classroom formats significantly outperformed those in traditional lectures, suggesting that moving content delivery outside class time and using class for active learning creates better outcomes. The research provides concrete evidence for teachers considering flipping their classrooms that this approach, especially when combined with frequent low-stakes testing, can substantially improve student achievement.

Memory consolidation is the remarkable neurobiological process that transforms fragile, newly acquired information into stable, long-term memories your brain can retrieve years later. This intricate mechanism occurs when neural pathways strengthen and reorganise, shifting memories from temporary storage in the hippocampus to permanent networks distributed across the cortex. Without consolidation, every lesson learnt, skill practised, and experience gained would fade within hours or days. Understanding how your brain accomplishes this transformation holds the key to making any learning truly stick.

The missing piece is memory consolidation, the biological process that transforms newly acquired information into stable, long-term memories. Without consolidation, learning remains fragile and easily disrupted. Understanding this process gives teachers insight into why some instructional practices produce lasting learning while others lead to rapid forgetting, and helps develop students' metacognitive awarenessand self-regulated learning skills.

Research over the past two decades has revealed that consolidation isn't passive. Specific brain processes during and after learning actively strengthen memory traces and integrate new information with existing knowledge . Teachers who understand these processes can structure instruction, practise, and even homework timing alongside evidence-based memory strategiesto support more durable learning.

Memory consolidation refers to the neurobiological processes that stabilise newly formed memories, making them resistant to forgetting and interference. When you first learn something, the memory exists in a vulnerable state, temporarily held in working memory before consolidation begins. Consolidation gradually transforms this fragile trace in to a stable, long-lasting memory.

| Process | Timeframe | Brain Activity | Teaching Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Encoding | Immediate | Hippocampus activation | Multi-sensory input, attention focus |

| Synaptic consolidation | Minutes to hours | Protein synthesis | Spaced practice, avoid interference |

| Systems consolidation | Days to weeks | Hippocampus to cortex transfer | Regular review, sleep importance |

| Reconsolidation | Upon retrieval | Memory updating | Retrieval practice, error correction |

| Long-term storage | Months to years | Distributed cortical networks | Interleaving, varied contexts |

The process occurs across two timescales.

Synaptic consolidation happens within hours of learning. New protein synthesis strengthens the connections between neurons that encode the memory. This cellular-level stabilisation begins immediately and continues for several hours.

Systems consolidation unfolds over days to weeks. Memories initially dependent on the hippocampus gradually become represented in neocortical networks. This redistribution creates more stable, long-term storage for declarative memory, the explicit knowledge and facts that students need to retain. This process integrated representations that can exist independently of the hippocampus.

For teachers, the practical implication is clear: learning doesn't end when the lesson finishes. The brain continues processing and strengthening memories long after students leave the classroom.

The three stages are encoding (initial learning), consolidation (stabilizing the memory), and retrieval (accessing stored information). Encoding creates a temporary memory trace in working memory, consolidation strengthens and transfers it to long-term storage over hours to weeks, and retrieval reactivates the stored memory.

Understanding memory consolidation requires placing it within the broader context of memory formation. Three stages characterise how experiences become lasting memories.

Encoding is the initial registration of information. During encoding, sensory experiences are transformed into neural representations. The quality of encoding determines what information enters the consolidation pipeline.

Effective encoding requires attention, meaningful processing, and connection to existing knowledge. Research on working memory highlights how encoding depends on limited cognitive resources that can be improved through instructional design.

Consolidation follows encoding, stabilising and strengthening memory traces. This process can be enhanced or impaired by various factors including sleep, stress, and subsequent learning experiences.

Crucially, consolidated memories aren't simply stored copies of original experiences. During consolidation, memories are reorganised, integrated with existing knowledge, and sometimes abstracted into more general patterns.

Retrieval is the process of accessing stored information. Successfully retrieving a memory doesn't just demonstrate learning; it further strengthens the memory trace through a process called reconsolidation.

This explains why retrieval practise is such a powerful learning strategy. Each successful retrieval triggers reconsolidation, making the memory even more stable.

Sleep plays an essential role in memory consolidation by allowing the brain to replay and strengthen neural connections formed during learning. Both REM and non-REM sleep stages contribute to consolidating different types of memories, with slow-wave sleep particularly important for declarative knowledge. Students who get adequate sleep after learning show significantly better retention compared to those who are sleep-deprived.

Perhaps no finding in memory research has more practical importance than the role of sleep in consolidation. Sleep isn't merely the absence of interference; it actively strengthens and reorganises memories.

Different sleep stages support consolidation of different memory types.

Slow-wave sleep (SWS), the deepest stage of non-REM sleep, preferentially supports consolidation of declarative memories: the facts and events that constitute much school learning. During SWS, the hippocampus "replays" recent experiences, gradually transferring representations to neocortical networks.

Research update: While this general pattern is supported by research, recent studies (including a 2024 study in Sleep Medicine) suggest the relationship is more complex than a simple one-to-one mapping. Both sleep stages appear to contribute to different aspects of memory consolidation, and the precise mechanisms continue to be refined by ongoing research.

REM sleep supports consolidation of procedural memories, including motor skills and implicit learning. Students learning physical skills, musical instruments, or procedures benefit from REM sleep following practise.

Both SWS and REM sleep contribute to memory consolidation, though their relative importance depends on what type of material is being learned.

The timing of sleep relative to learning affects consolidation. Research by Gais and colleagues found that sleep within three hours of learning produces better retention than sleep delayed by ten hours. This suggests that studying new material in the evening, followed by a full night's sleep, may be more effective than morning study followed by an active day.

Practical implications for homework timing emerge from this research. New or challenging material assigned as evening homework may benefit from overnight consolidation before the next lesson. Review of previously learned material might be better suited to morning assignments.

Teenagers face a particular challenge: their biological clocks shift towards later sleep and wake times just as school schedules demand early starts. This mismatch between biological rhythms and school timing means many adolescents experience chronic sleep restriction that impairs memory consolidation.

Teachers cannot solve this structural problem, but understanding it helps explain why some students struggle with retention despite apparent understanding during lessons. Supporting students in understanding the importance of sleep for learning may encourage better sleep habits.

Active Systems Consolidation Theory proposes that memories are actively reorganized during sleep through coordinated activity between the hippocampus and neocortex. During sleep, the hippocampus repeatedly reactivates memory traces from the day, gradually transferring them to cortical networks for long-term storage. This process explains why sleep between learning sessions enhances memory retention and integration with existing knowledge.

The dominant theoretical framework for understanding memory consolidation is active systems consolidation theory, developed primarily by Jan Born and colleagues.

This theory proposes that during sleep, the hippocampus repeatedly reactivates recent memory traces. Each reactivation strengthens cortical representations while gradually reducing hippocampal dependence. Over time, memories become independent of the hippocampus and fully integrated into cortical knowledge networks.

Brain imaging studies support this account. Regions active during learning are reactivated during subsequent sleep. The degree of reactivation predicts later memory strength. This isn't passive maintenance; it's active processing that transforms and strengthens memories.

For teachers, this theory reinforces the importance of creating meaningful initial learning experiences. Memories that are strongly encoded and connected to existing knowledge will be preferentially consolidated during sleep.

When students retrieve a memory, it temporarily becomes labile (unstable) and must undergo reconsolidation to be restored. This reconsolidation window provides an opportunity to update, strengthen, or modify the memory through additional learning or practise. Teachers can use reconsolidation by incorporating retrieval practise that allows students to strengthen and refine their understanding.

A fascinating discovery is that consolidated memories can become temporarily unstable when retrieved. This process, called reconsolidation, has significant implications for education.

Each retrieval event triggers reconsolidation, which can strengthen the memory. This explains part of why retrieval practise is so effective: it doesn't just measure memory but actively modifies and strengthens it through reconsolidation.

Reconsolidation provides a window for modifying incorrect memories. When students retrieve a misconception and are immediately provided with correct information, the reconsolidation process may integrate the correction into the updated memory.

This has implications for addressing misconceptions. Rather than simply providing correct information, triggering retrieval of the misconception first may facilitate correction through reconsolidation.

High cognitive load during initial learning can impair memory consolidation by overwhelming working memor y capacity and preventing effective encoding. When students process too much information at once, their brains struggle to form strong initial memory traces that can be consolidated. Teachers should manage cognitive load by breaking complex topics into smaller chunks and providing adequate processing time between new concepts.

Cognitive load theory focuses primarily on encoding, but consolidation considerations extend its implications.

Effective consolidation requires effective encoding. If cognitive load during instruction exceeds working memory capacity, encoding suffers, and there's less to consolidate. Managing cognitive load during instruction supports better consolidation downstream.

The period immediately after learning appears important for consolidation. Research suggests that mentally rehearsing or elaborating on recently learned material strengthens consolidation. Brief reflection periods after instruction may support this process.

Sleep deprivation impairs both encoding through reduced attention and consolidation through insufficient sleep-dependent memory processing. Students who are sleep deprived face a double challenge in learning.

Effective strategiesinclude spaced practise sessions, interleaving different topics, and incorporating retrieval practise through low-stakes quizzing. Teachers should also time homework to allow for sleep-based consolidation and avoid introducing similar content that might cause interference. Building in reflection time at the end of lessons helps initiate the consolidation process before students leave class.

Understanding consolidation suggests several practical classroom strategies.

Assign new or challenging material as evening homework when possible. This positions new learning close to sleep, maximising the opportunity for overnight consolidation.

Begin lessons with review of previously learned material. This retrieval practise strengthens those memories through reconsolidation while activating relevant schemas that support encoding of new content.

Include brief pauses after presenting new concepts. These moments allow initial synaptic consolidation to begin and give students opportunity to make connections with existing knowledge.

Help students understand the connection between sleep and learning. This is particularly important for older students who may undervalue sleep in favour of late-night studying.

Avoid teaching highly similar concepts in consecutive lessons. Allow consolidation time between related but potentially confusable content.

Rather than testing only recent content, include material from earlier in the course. This requires retrieval of previously consolidated material, strengthening it further.

Help students plan revision that distributes practise over time rather than cramming. Connect this to their understanding of how consolidation works.

Declarative memories (facts and concepts) consolidate primarily during slow-wave sleep and rely heavily on hippocampal-neocortical interactions. Procedural memories (skills and procedures) consolidate during REM sleep and involve motor cortex and striatal regions. Teachers should consider these differences when scheduling practise for different subjects, with conceptual material benefiting from immediate review and procedural skills from distributed practise.

Different types of learning may consolidate through somewhat different mechanisms.

Facts and concepts (declarative memory) rely heavily on sleep-dependent consolidation involving hippocampal-neocortical dialogue. The classroom focus on declarative knowledge makes sleep particularly important for school learning.

Skills and procedures (procedural memory) consolidate through repetition and practise, with sleep, particularly REM sleep, playing a role in offline gains. Students learning procedures should expect improvement after sleep, even without additional practise.

Learning to make perceptual distinctions, such as recognising patterns or distinguishing sounds, shows sleep-dependent consolidation. Students learning to recognise scientific specimens, musical intervals, or language sounds benefit from overnight consolidation.

Individual differences in memory consolidation stem from factors including sleep quality, stress levels, prior knowledge, and neurobiological variations. Students with better sleep habits, lower stress, and stronger foundational knowledge typically show more effective consolidation. Teachers can address these differences by providing multiple consolidation opportunities and teaching students about factors that influence their memory formation.

Students vary in their consolidation efficiency, affecting learning outcomes.

Children show strong sleep-dependent memory consolidation, often even stronger than adults. However, they require more sleep overall. Adolescents face the challenge of shifted biological clocks combined with early school starts.

Students with sleep disorders, inconsistent sleep schedules, or insufficient sleep quantity show impaired consolidation. These students may understand material in class but show poor retention.

Students with more relevant prior knowledge consolidate new information faster because they have existing schemas to integrate it with. This creates cumulative advantages for students who build strong knowledge foundations.

Emotional arousal during learning enhances memory consolidation through the release of stress hormones and increased amygdala activity. Moderately positive emotions create optimal conditions for consolidation, while extreme stress or negative emotions can impair the process. Teachers can use this by creating emotionally engaging but supportive learning environmentsthat enhance memory formation without causing anxiety.

Emotional experiences are consolidated differently from neutral ones. Moderate emotional arousal enhances consolidation, while extreme stress can impair it.

Some emotional engagement with learning supports consolidation. Complete boredom reduces encoding quality, while overwhelming stress impairs both encoding and consolidation. The moderate challenge of desirable difficulties may hit an optimal arousal level.

Chronic stress and anxiety impair memory consolidation. Students experiencing significant stress may struggle with retention despite adequate understanding during lessons.

Teachers can support struggling students by providing more frequent review opportunities, teaching explicit memory strategies, and ensuring adequate processing time during lessons. Additional scaffolds include visual organisers, mnemonic devices, and structured note-taking systems that facilitate initial encoding. Creating predictable routines and reducing cognitive load through clear organisation also helps students with consolidation challenges.

Some students may show particular difficulties with memory consolidation.

Students reporting sleep difficulties may need support in improving sleep habits. For some, referral to health services may be appropriate. Teachers can accommodate by providing more distributed practise opportunities and reducing reliance on single learning episodes.

Students with attention challenges may have encoding difficulties that limit what enters consolidation. Strategies supporting attention during instruction indirectly support consolidation.

Students with working memory difficulties may struggle with the initial encoding that precedes consolidation. Breaking content into smaller chunks and providing external supports, such as notes or graphic organisers, helps ensure adequate encoding.

Spaced practise allows time for memory consolidation to occur between learning sessions, strengthening neural pathways and reducing forgetting. Each spaced review session triggers reconsolidation, which further strengthens the memory trace and promotes long-term retention. Massed practise prevents consolidation between repetitions, leading to weaker memory formation despite the immediate appearance of mastery.

The benefits of spaced practise can be partly understood through consolidation. When practise is distributed over time, consolidation occurs between sessions. Each subsequent practise session retrieves and reconsolidates the partially consolidated memory, strengthening it further.

Massed practise, by contrast, doesn't allow consolidation between repetitions. The memory remains in an unstable state throughout the practise session and only begins consolidating when practise ends.

This explains why the same total practise time produces better retention when distributed rather than massed. Spacing allows the consolidation processes that strengthen memories and protect them from forgetting.

Teachers can translate consolidation research into practise by structuring lessons with built-in consolidation time, scheduling reviews to coincide with consolidation windows, and educating students about memory processes. Practical applications include ending lessons with summary activities, assigning reflective homework before sleep, and using next-day warm-ups to reactivate previous learning. Understanding the biological basis helps teachers make evidence-informed decisions about timing and sequencing instruction.

Memory consolidation represents a bridge between neuroscience and educational practise. While teachers cannot directly manipulate brain processes, understanding consolidation helps explain why certain practices work and suggests refinements to instructional timing and structure.

The key insight is that learning continues after lessons end. The period following instruction, particularly sleep, plays an active role in converting understanding into lasting knowledge. Teachers who structure instruction, practise, and assessment with consolidation in mind create conditions for more durable learning.

Practically, this means spacing rather than massing practise, positioning new learning to maximise sleep consolidation, building retrieval practise into routines, and teaching students about how their memory works.

Essential papers include Dudai's reviews on consolidation theory, Rasch and Born's work on sleep and memory, and Roediger's research on retrieval practise and consolidation. These foundational works provide accessible explanations of consolidation mechanisms and their educational implications. Teachers can also explore practical guides that translate neuroscience findings into classroom applications.

The following papers provide deeper exploration of memory consolidation and its educational implications.

This comprehensive review established the critical role of sleep in memory consolidation. The authors synthesise evidence from behavioural, brain imaging, and neurophysiological studies to argue that sleep actively processes memories rather than simply preventing interference. Essential reading for understanding sleep's role in learning.

This Nature Reviews Neuroscience article provides an authoritative account of active systems consolidation theory. The authors explain how hippocampal-neocortical dialogue during sleep transforms memories from temporary hippocampal representations to stable neocortical networks.

This practical review translates consolidation research into recommendations for learning and education. The author addresses questions about optimal sleep timing, napping, and how understanding consolidation can improve study strategies.

This review examines reconsolidation, the process by which retrieved memories become labile and can be modified. The paper discusses implications for updating memories and correcting errors, with relevance to addressing misconceptions in educational contexts.

This study demonstrates sleep-dependent consolidation in a learning context relevant to education. Participants showed improved speech recognition after sleep but not after equivalent time awake, illustrating the active role of sleep in perceptual learning.

Memory consolidation operates through two distinct yet interconnected processes: synaptic consolidation and systems consolidation. Synaptic consolidation occurs within hours of learning, as proteins synthesise to strengthen connections between neurons. This process explains why revision immediately after a lesson proves more effective than waiting until the evening; the neural pathways remain active and receptive to reinforcement.

Systems consolidation unfolds over weeks and months, gradually shifting memories from the hippocampus to the neocortex. During this transfer, memories become integrated with existing knowledge networks, creating the rich, interconnected understanding that characterises expert thinking. Brain imaging studies reveal that well-consolidated memories activate broader cortical regions, suggesting they become woven into multiple knowledge structures.

Teachers can support these neurobiological processes through strategic instructional design. Spacing practise sessions across days or weeks aligns with systems consolidation timelines, allowing the brain to repeatedly reactivate and strengthen memory traces. For instance, introducing key vocabulary on Monday, revisiting it through different activities on Wednesday, and applying it in context on Friday creates multiple consolidation opportunities.

Sleep plays a crucial role in both consolidation stages. During slow-wave sleep, the hippocampus replays learning experiences, strengthening synaptic connections. REM sleep then integrates these memories with existing knowledge. This research validates homework timing; assignments completed earlier in the evening allow proper sleep consolidation, whilst late-night cramming disrupts these essential processes.

Understanding these mechanisms helps teachers make evidence-based decisions about curriculum pacing, homework design, and revision strategies. Rather than fighting against the brain's natural consolidation rhythms, effective teaching works in harmony with these biological processes to create lasting learning.

Memory consolidation occurs through two distinct but interconnected processes: synaptic consolidation and systems consolidation. Understanding both helps teachers design more effective learning experiences that work with, rather than against, how the brain naturally stores information.

Synaptic consolidation happens first, typically within minutes to hours after learning. During this process, connections between neurons strengthen through repeated activation and protein synthesis. This explains why immediate review activities are so powerful; when students revisit new material within the same lesson or shortly afterwards, they're supporting these cellular-level changes. For instance, ending a maths lesson with a quick problem-solving session reinforces the synaptic changes initiated during instruction.

Systems consolidation unfolds over weeks, months, or even years. Here, memories gradually reorganise, shifting from temporary storage in the hippocampus to more permanent residence across the cortex. This process explains why spaced practise works so effectively. When students encounter previously learnt material after days or weeks, they're not just reviewing; they're facilitating the brain's natural tendency to redistribute and strengthen memory networks.

Teachers can support both processes through strategic planning. For synaptic consolidation, incorporate brief retrieval practise within lessons, such as having students explain a concept to a partner immediately after teaching it. For systems consolidation, design curriculum spirals that revisit key concepts at increasing intervals. A science teacher might introduce photosynthesis in September, return to it when teaching ecosystems in November, and connect it to carbon cycles in February.

Research by Dudai (2004) and Frankland & Bontempi (2005) shows that respecting both consolidation timescales dramatically improves retention. By aligning teaching methods with these biological processes, educators help ensure that today's lessons become tomorrow's accessible knowledge.

Sleep isn't just rest for tired bodies; it's when your brain actively transforms the day's learning into lasting memories. During sleep, particularly deep slow-wave sleep and REM phases, the brain replays and reorganises information acquired during waking hours. This nocturnal processing strengthens neural connections, transfers memories from temporary to permanent storage, and integrates new knowledge with existing understanding.

Research by Walker and Stickgold (2006) demonstrates that students who sleep after learning perform significantly better on tests than those who stay awake, even when total study time remains identical. The hippocampus, which temporarily stores new memories, communicates with the cortex during sleep, gradually shifting information into long-term storage networks. Without adequate sleep, this transfer process falters, leaving memories vulnerable to decay.

Teachers can harness sleep's power through strategic planning. Schedule challenging new concepts early in the school day, allowing maximum time for consolidation before students sleep. When teaching complex procedures or problem-solving methods, encourage students to review notes briefly before bedtime; this 'sleep to remember' strategy enhances overnight consolidation. For revision periods, advise students to spread learning across multiple days rather than cramming, ensuring each study session benefits from sleep-dependent consolidation.

Consider adjusting homework patterns too. Rather than assigning heavy practise immediately after teaching, introduce new concepts, provide light initial practise, then assign deeper practise the following day after consolidation has begun. This approach respects the brain's natural learning rhythms and produces more durable understanding. Even a 20-minute classroom nap after intensive learning can boost memory retention, though this remains impractical in most school settings.

Memory consolidation is the neurobiological process that transforms newly learned information from a fragile, temporary state into stable, long-term memories that resist forgetting. Teachers should care because understanding this process explains why students can understand material perfectly during lessons but forget it days later, and helps educators time instruction and practise more effectively to support lasting learning.

Memory consolidation occurs across two timescales: synaptic consolidation happens within hours of learning as protein synthesis strengthens neural connections, whilst systems consolidation unfolds over days to weeks as memories transfer from the hippocampus to more stable cortical networks. This means the brain continues processing and strengthening memories long after students leave the classroom.

Research suggests that new or challenging material should be assigned as evening homework, as sleep within three hours of learning produces better retention than delayed sleep. Review of previously learned material might be better suited to morning assignments, allowing students to benefit from overnight memory consolidation before tackling new concepts.

During sleep, particularly slow-wave sleep, the hippocampus actively 'replays' recent learning experiences and gradually transfers them to cortical networks for long-term storage. Students who get adequate sleep after learning show significantly better retention compared to sleep-deprived students, as both REM and non-REM sleep stages contribute to consolidating different types of memories.

Teenagers' biological clocks naturally shift towards later sleep and wake times, but early school schedules create chronic sleep restriction that impairs memory consolidation. Whilst teachers cannot solve this structural problem, they can help students understand the importance of sleep for learning and potentially adjust homework timing to work with rather than against natural sleep patterns.

When students successfully retrieve information from memory, it doesn't just demonstrate learning but actually triggers reconsolidation, making the memory even more stable and resistant to forgetting. This explains why retrieval practise activities like testing and quizzing are such powerful learning strategies, as each successful retrieval strengthens the underlying memory trace.

Teachers should recognise that learning doesn't end when lessons finish, as consolidation continues for hours and days afterwards. This means structuring instruction to support encoding through attention and meaningful connections, timing practise and homework to align with consolidation processes, and using retrieval practise to strengthen memories through reconsolidation.

These peer-reviewed studies provide the research foundation for the strategies discussed in this article:

A Large Language Model-Based System for Socratic Inquiry: Developing Deep Learning and Memory Consolidation View study ↗

3 citations

This recent research demonstrates how AI chatbots can be programmed to ask probing questions in the style of Socratic teaching, helping students think more deeply about material rather than just memorizing fac ts. The system addresses a key challenge teachers face: it's difficult to consistently apply Socratic questioning with every student, but AI can provide personalised, thought-provoking questions that strengthen long-term memory formation. This technology could serve as a powerful teaching assistant, giving educators a new tool to promote deeper understanding and combat the natural forgetting that occurs without proper reinforcement.

Self-regulation, evaluation, and promotion of learning through the practise of memory recovery View study ↗3 citations

L. Oliveira & L. Stein (2018)

This research reveals that frequent low-stakes testing serves a dual purpose: it not only assesses what students know but actually strengthens their memory of the material through activerecall. The authors argue that when teachers shift from viewing tests purely as evaluation tools to seeing them as learning opportunities, students develop better study habits and retain information longer. This approach encourages educators to incorporate more frequent, brief quizzes and self-assessment activities that help students monitor their own learning progress while simultaneously reinforcing their knowledge.

Testing (quizzing) boosts classroom learning: A systematic and meta-analytic review. View study ↗

241 citations

Chunliang Yang et al. (2021)

This comprehensive analysis of over 200 studies involving nearly 50,000 students provides compelling evidence that regular quizzing dramatically improves long-term learning compared to simply re-reading or reviewing notes. The research shows that the testing effect, where retrieving information from memory strengthens retention, works consistently across different subjects, age groups, and classroom settings. For teachers, this means that incorporating frequent, low-pressure quizzes into their routine can be one of the most powerful strategies for helping students retain what they learn, making it far superior to traditional study methods like highlighting or rereading.

Making assessment promote effective learning practices: An example of ipsative assessment from the School of Psychology at UEL View study ↗

5 citations

P. Penn & I. Wells (2018)

Despite strong research showing that self-testing improves memory, most students avoid this study strategy and stick to less effective methods like rereading notes. These researchers solved this problem by designing assessments that require students to practise retrieving information from memory, essentially building the most effective study technique directly into their coursework. This approach shows teachers how to structure assignments and assessments so that students automatically engage in memory-strengthening activities, ensuring they benefit from retrieval practise whether they would choose to use it on their own or not.

Enhancing Student Learning with Flipped Teaching and Retrieval Practise Integration. View study ↗

Chaya Gopalan (2024)

This study compared traditional lecture-based teaching with flipped classrooms and found that combining flipped instruction with regular retrieval practise produced the highest student performance scores. Students in both flipped classroom formats significantly outperformed those in traditional lectures, suggesting that moving content delivery outside class time and using class for active learning creates better outcomes. The research provides concrete evidence for teachers considering flipping their classrooms that this approach, especially when combined with frequent low-stakes testing, can substantially improve student achievement.

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/memory-consolidation-teachers-guide#article","headline":"Memory Consolidation: How the Brain Transforms Learning into Lasting Knowledge","description":"Understand how memory consolidation converts fragile new learning into stable long-term knowledge, and discover evidence-based strategies to support this...","datePublished":"2025-12-29T10:18:06.138Z","dateModified":"2026-01-26T10:09:32.212Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/memory-consolidation-teachers-guide"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/6967ce3029a2c1aba2b6118c_6967ce2e68b6ac7ae37446c1_memory-consolidation-teachers-guide-diagram.webp","wordCount":5024},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/memory-consolidation-teachers-guide#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"Memory Consolidation: How the Brain Transforms Learning into Lasting Knowledge","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/memory-consolidation-teachers-guide"}]},{"@type":"FAQPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/memory-consolidation-teachers-guide#faq","mainEntity":[{"@type":"Question","name":"How long does memory consolidation actually take after students learn something new?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Memory consolidation occurs across two timescales: synaptic consolidation happens within hours of learning as protein synthesis strengthens neural connections, whilst systems consolidation unfolds over days to weeks as memories transfer from the hippocampus to more stable cortical networks. This mea"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What practical changes can teachers make to homework timing based on memory consolidation research?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Research suggests that new or challenging material should be assigned as evening homework, as sleep within three hours of learning produces better retention than delayed sleep. Review of previously learned material might be better suited to morning assignments, allowing students to benefit from over"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"How does sleep specifically help students retain what they've learned in class?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"During sleep, particularly slow-wave sleep, the hippocampus actively 'replays' recent learning experiences and gradually transfers them to cortical networks for long-term storage. Students who get adequate sleep after learning show significantly better retention compared to sleep-deprived students, "}},{"@type":"Question","name":"Why do teenagers struggle more with memory retention, and how can teachers support them?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Teenagers' biological clocks naturally shift towards later sleep and wake times, but early school schedules create chronic sleep restriction that impairs memory consolidation. Whilst teachers cannot solve this structural problem, they can help students understand the importance of sleep for learning"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"How does retrieval practise strengthen memory consolidation in students?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"When students successfully retrieve information from memory, it doesn't just demonstrate learning but actually triggers reconsolidation, making the memory even more stable and resistant to forgetting. This explains why retrieval practise activities like testing and quizzing are such powerful learnin"}}]}]}