The Pretesting Effect: Why Testing Before Teaching Works

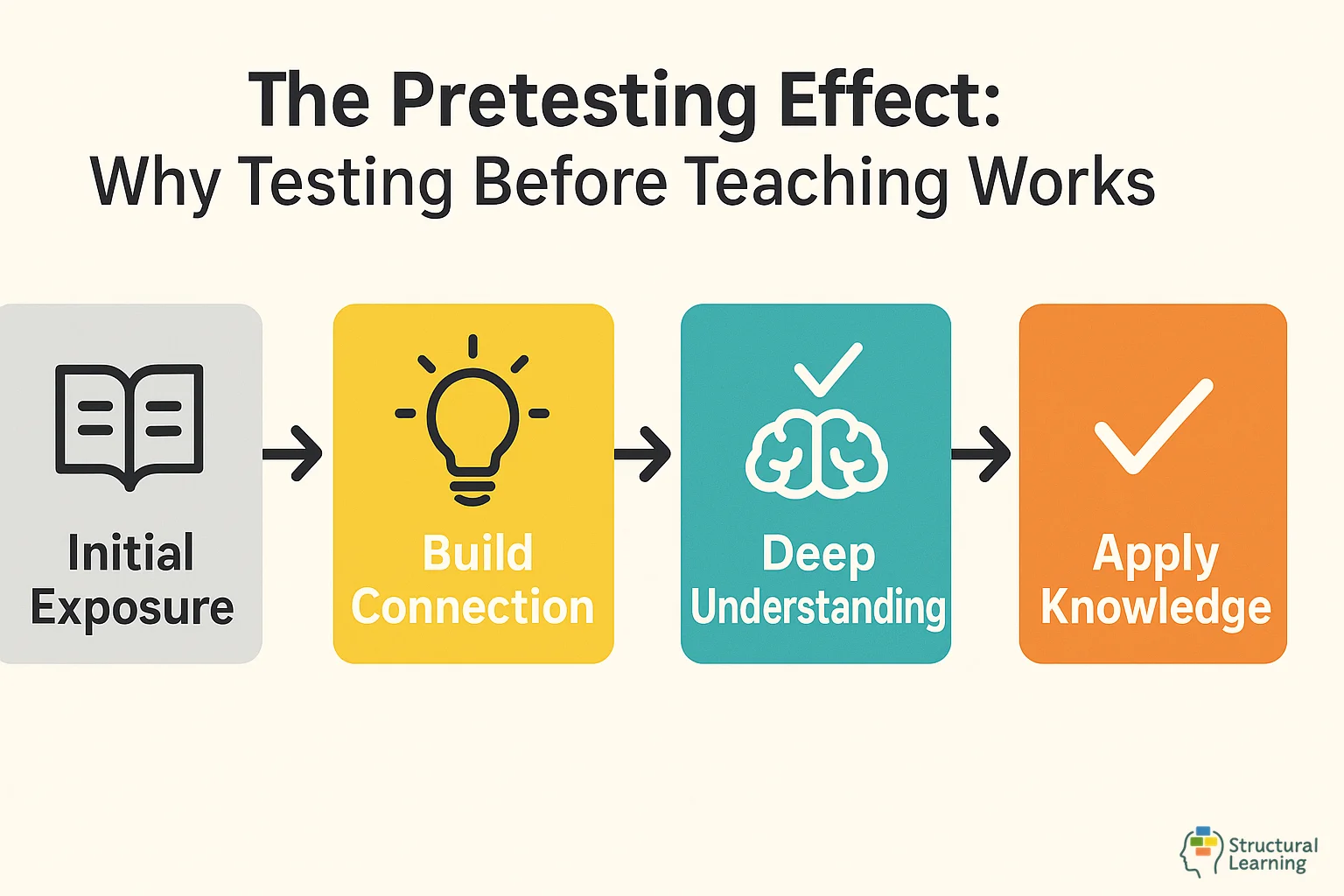

The pretesting effect shows that assessing pupils before teaching enhances their learning, even with wrong answers, giving teachers a powerful strategy.

The pretesting effect shows that assessing pupils before teaching enhances their learning, even with wrong answers, giving teachers a powerful strategy.

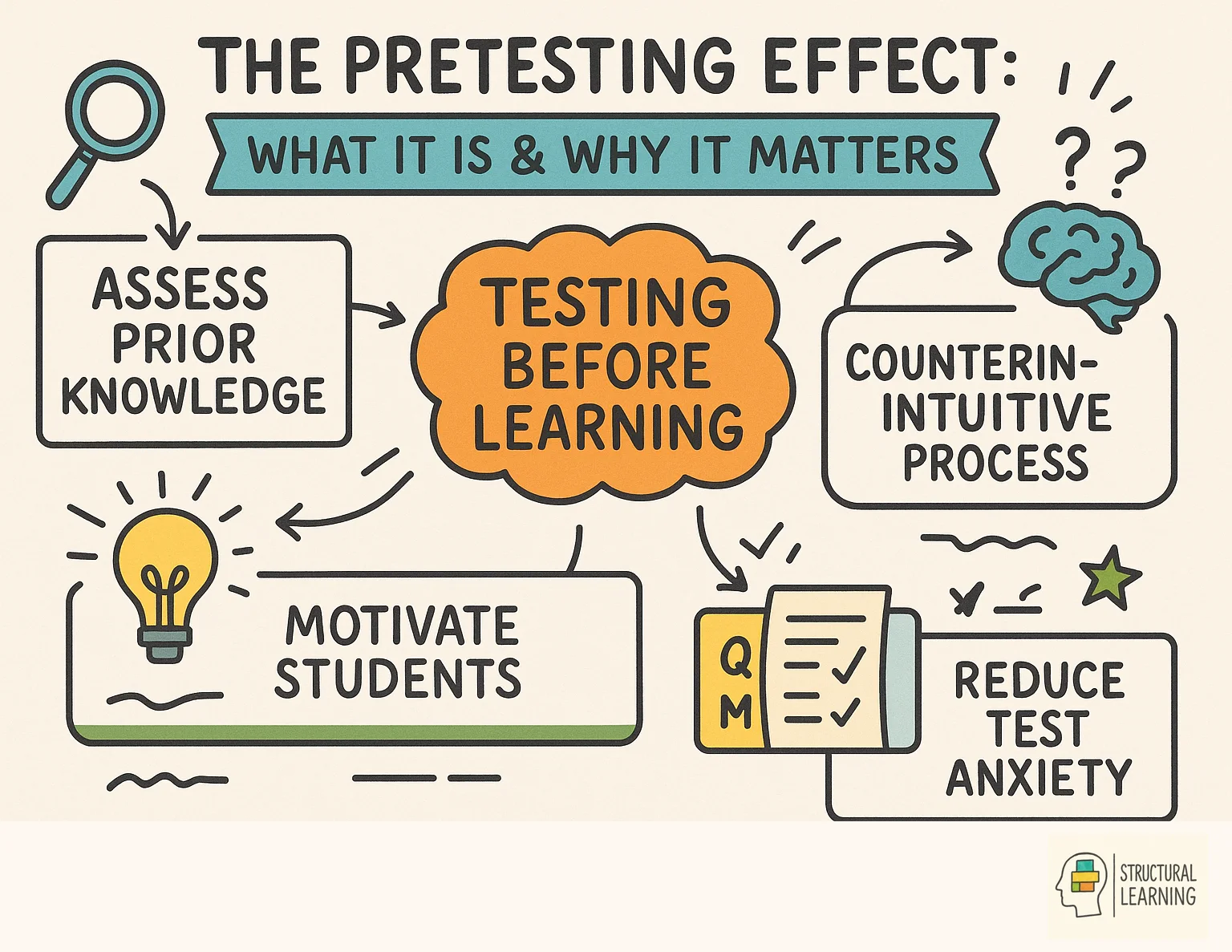

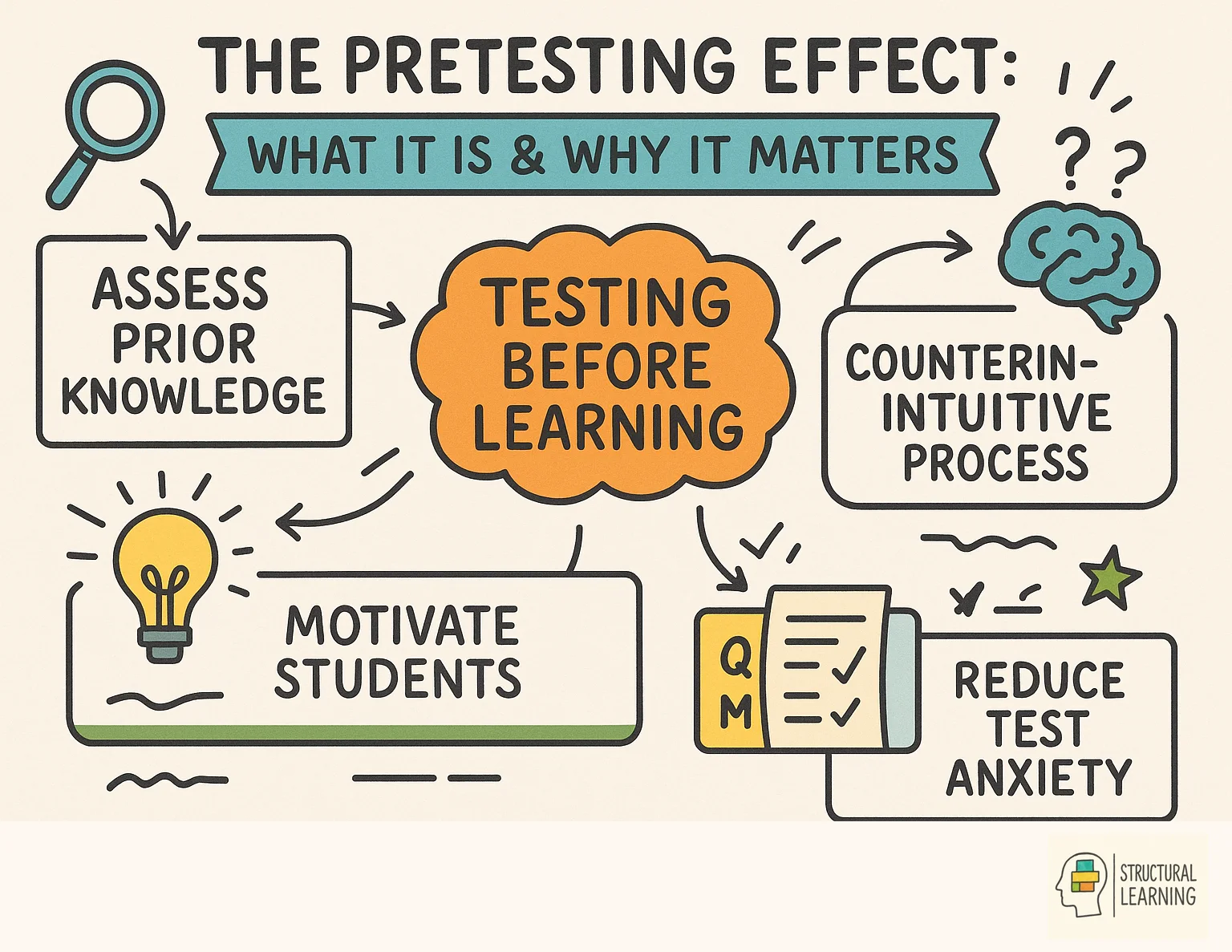

Testing students on material they haven't yet learned might seem counterproductive. Why quiz pupils on content they're bound to get wrong? Yet a growing body of research reveals something unexpected: unsuccessful retrieval attempts before learning actually enhance how well students acquire and retain new information. This counterintuitive finding, known as the pretesting effect, suggests that errors made in the right context don't hinder learning; they prepare the mind for it.

testing effect in education" loading="lazy">

testing effect in education" loading="lazy">The implications for classroom practise are substantial. In 2025, as educators seek evidence-based strategies to strengthen student learning, pretesting emerges as a simple, low-stakes intervention that requires minimal preparation yet produces meaningful gains. Unlike the testing effect, which focuses on retrieving already-learned material, the pretesting effect concerns what happens when learners attempt to answer questions about material they haven't encountered.

Key Takeaways

Your Classroom infographic for The Pretesting Effect: Why Testing Before Teaching Works" loading="lazy">

Your Classroom infographic for The Pretesting Effect: Why Testing Before Teaching Works" loading="lazy">

The pretesting effect, also called the prequestioning effect or errorful generation effect, refers to the finding that taking a test before learning new information leads to stronger memory and understanding of that information than simply studying without pretesting. Crucially, this benefit occurs even when, indeed especially when, learners answer pretest questions incorrectly.

Consider a typical demonstration: one group of students takes a short quiz on a topic they haven't yet studied, getting most answers wrong. A second group spends the same time doing an unrelated activity. Both groups then receive identical instruction on the topic. When tested afterwards, the pretested group consistently outperforms the control group, despite their initial errors.

This phenomenon challenges traditional assumptions about learning. The errorless learning tradition, influenced by behaviourist psychology, held that exposing learners to errors would reinforce those mistakes. Pretesting research reveals a different picture: when errors are followed by corrective information, they can actually enhance rather than hinder learning.

The term "pretesting effect" gained prominence following influential studies by Richland, Kornell, and Kao in 2009, though related findings appeared in earlier educational psychology research from the 1960s and 1970s. Recent years have seen a surge of interest, with researchers investigating boundary conditions, underlying mechanisms, and practical applications.

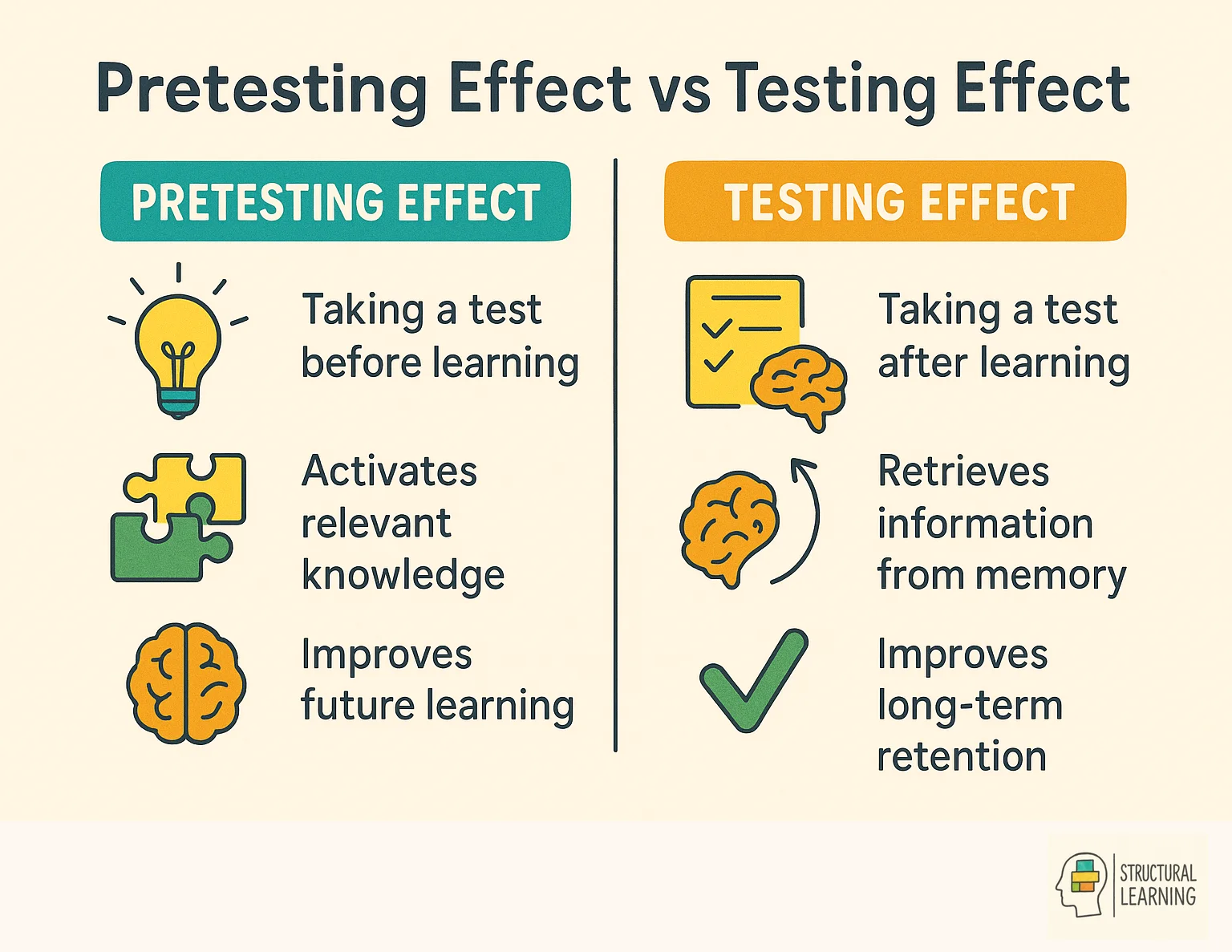

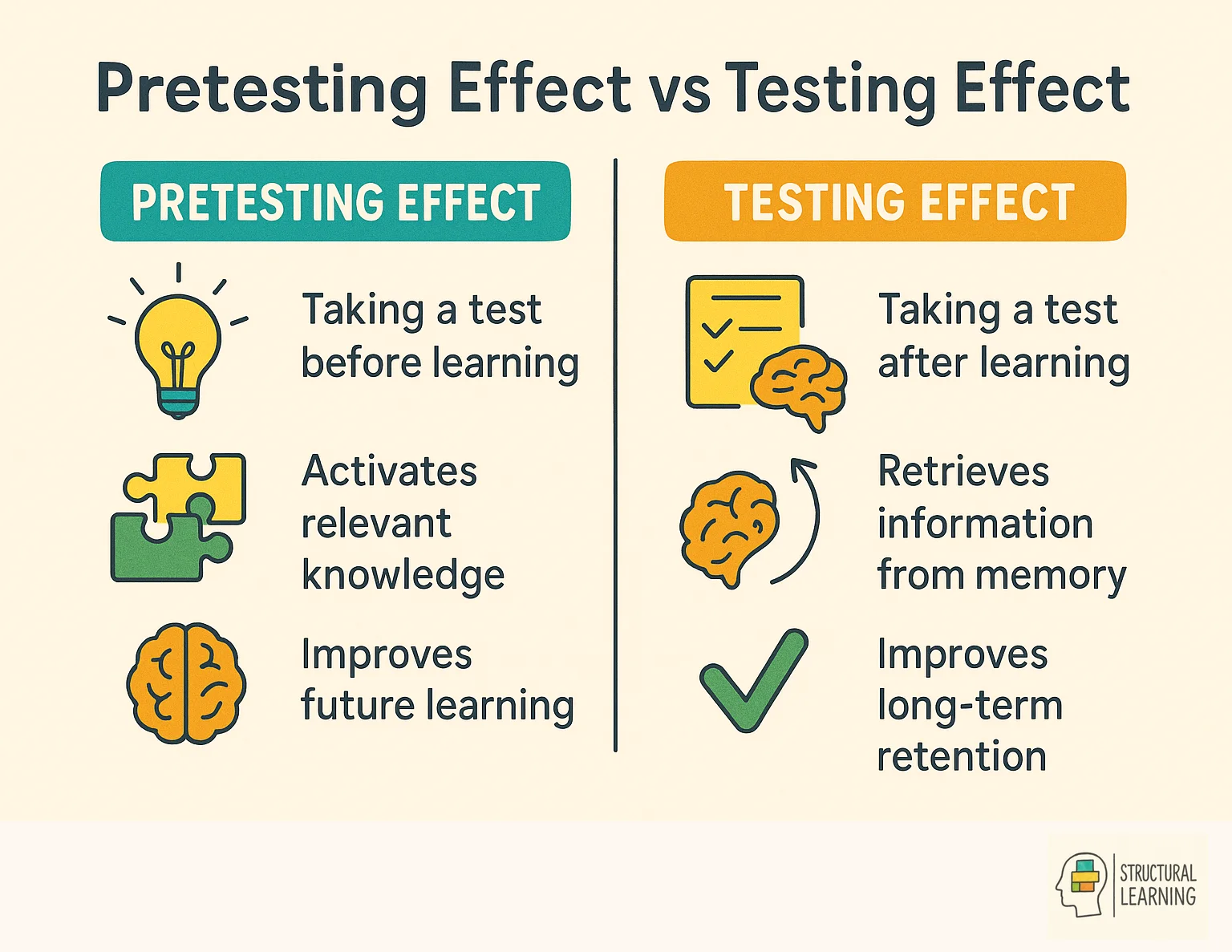

Pretesting involves testing students on material they haven't learned yet, while regular testing assesses already-studied content. The pretesting effect enhances future learning through incorrect attempts, whereas the testing effect strengthens retrieval of existing knowledge. Both improve learning but work through different cognitive mechanisms.

Understanding the pretesting effect requires distinguishing it from related phenomena in the learning sciences.

The well-established testing effect concerns how retrieving learned information strengthens memory for that information. When students successfully recall material on practise tests, this act of retrieval enhances later retention compared to restudying. The testing effect depends on successful retrieval of previously learned material.

The pretesting effect operates differently. Here, retrieval attempts occur before learning, when correct retrieval is impossible. Students generate guesses, typically incorrect ones. Yet subsequent learning is enhanced. The mechanisms must therefore differ from those underlying the standard testing effect.

Manu Kapur's research on productive failure examines how initial struggle with problems before instruction can enhance learning, particularly for complex conceptual material. While related to pretesting, productive failure typically involves more extended problem-solving attempts and emphasises the role of generating multiple solution strategies.

Pretesting studies often use simpler materials, such as definitions, facts, or short-answer questions, and focus specifically on the effects of test-like retrieval attempts. The overlap between these literatures is substantial, but they emerged from different research traditions and emphasise different aspects of "learning from errors."

Robert Bjork's concept of desirable difficulties provides a broader framework for understanding pretesting. Desirable difficulties are learning conditions that feel harder but produce more durable, transferable learning. Pretesting fits within this framework: the initial struggle and errors create difficulty that ultimately serves learning.

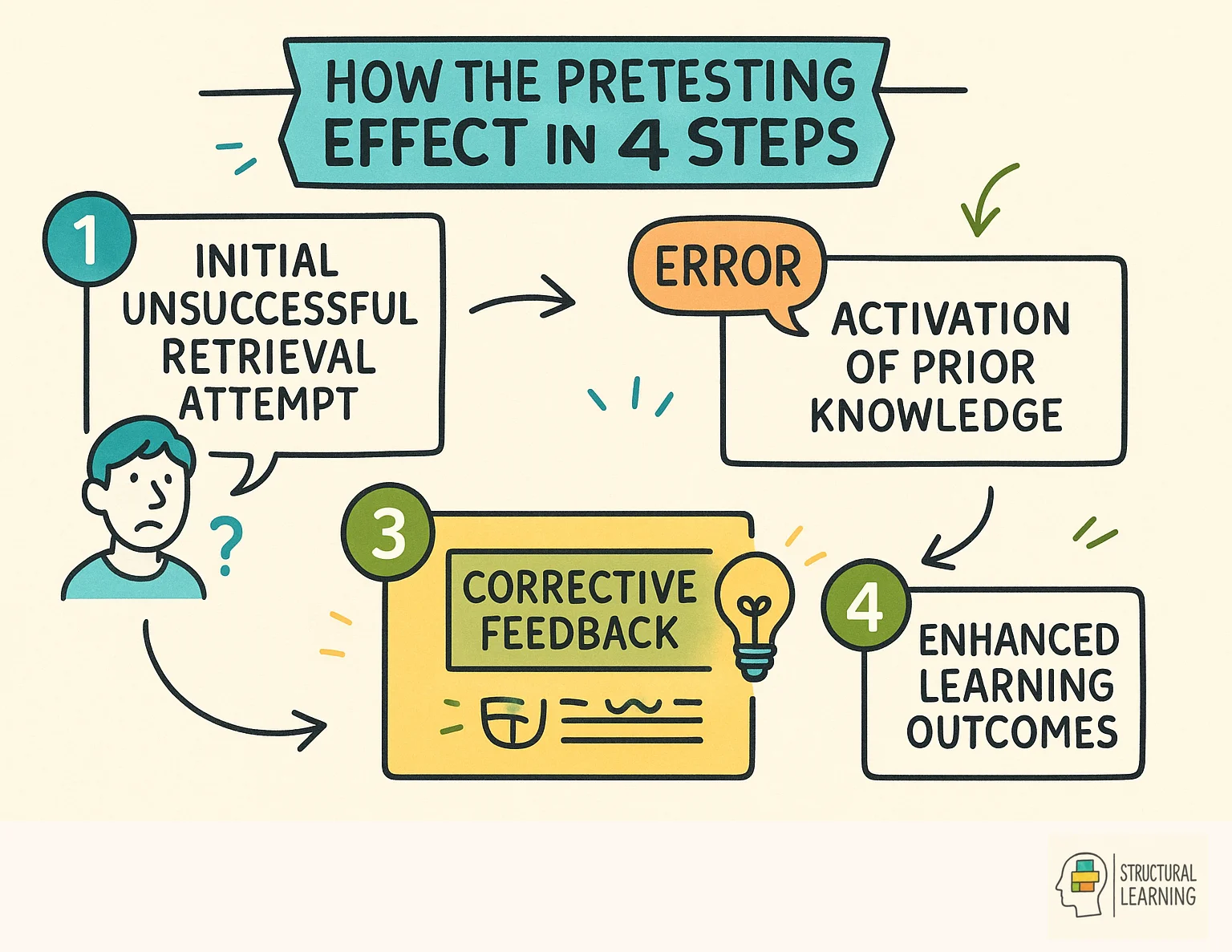

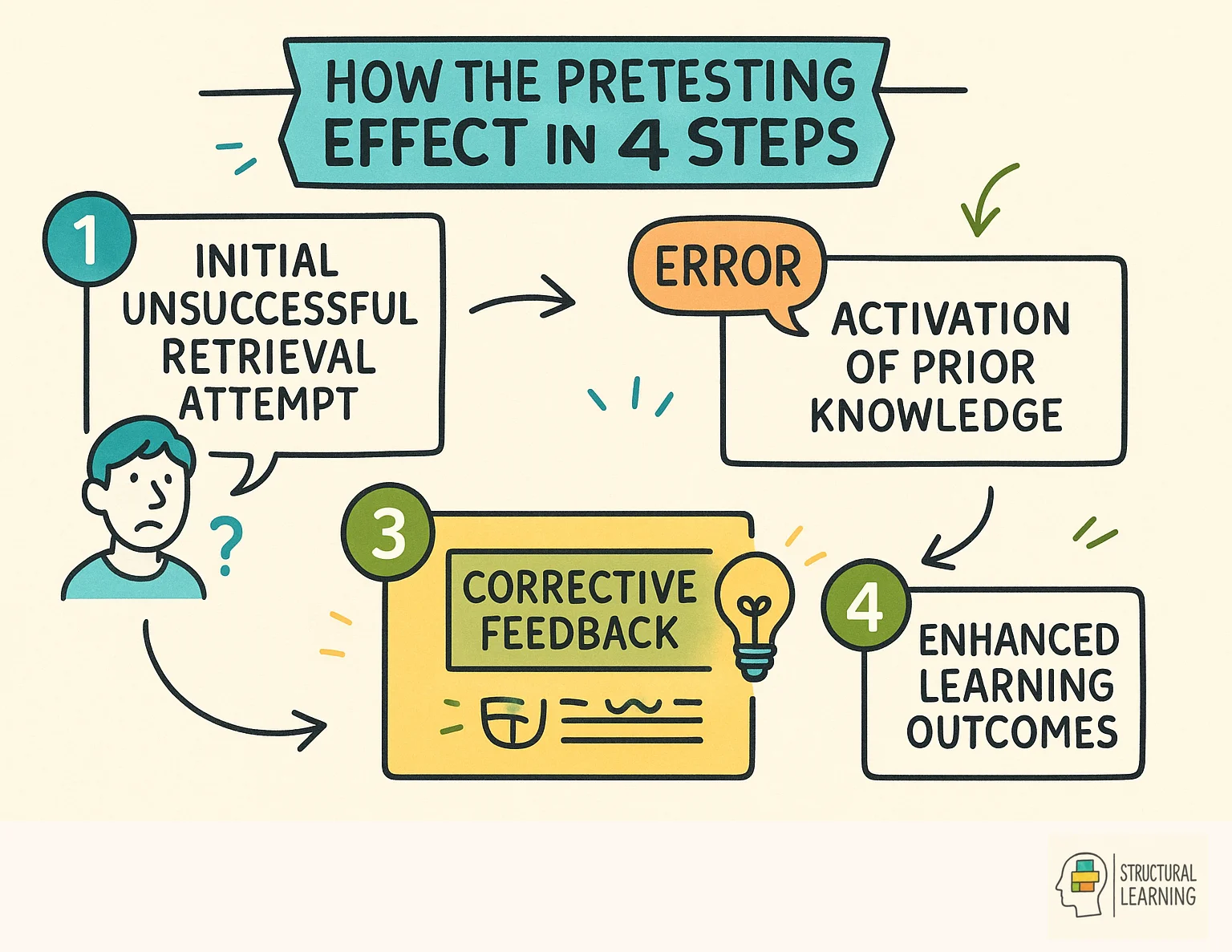

Researchers have proposed several mechanisms to explain why unsuccessful retrieval attempts enhance subsequent learning. These explanations aren't mutually exclusive; multiple processes likely contribute to the effect.

One prominent explanation holds that pretesting directs attention towards incoming information. When students attempt to answer questions and discover they cannot, they become alert to the answers when they subsequently encounter the material. The pretest essentially highlights what they don't know, creating a mental "need to know" that focuses attention during learning.

Supporting this account, studies have found that pretesting reduces mind wandering during lectures and video presentations. Students who take pretests report higher attention levels during subsequent instruction. This attentional focusing may be particularly valuable in contexts prone to distraction.

Related to attention, pretesting may activate curiosity. When students generate a guess and await confirmation or correction, they become invested in learning the answer. This curiosity provides motivation that enhances encoding of the correct information.

Information presented as an answer to a question one has already contemplated may be processed more deeply than the same information presented without such priming. The learner's mind is already engaged with the relevant conceptual territory.

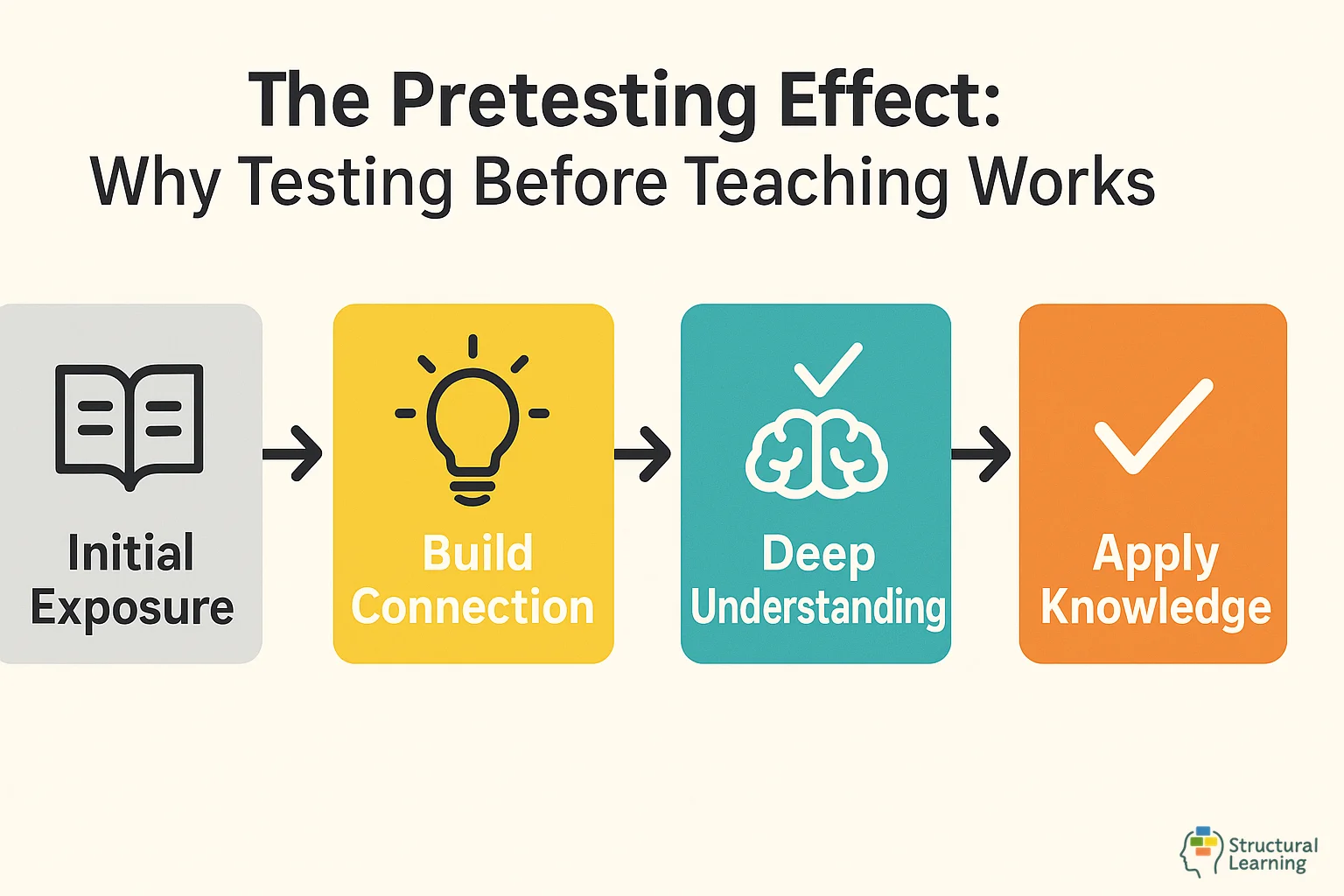

Attempting to answer a pretest question activates related knowledge in long-term memory. Even when the correct answer isn't retrieved, semantically related concepts become active. This activation creates a richer network of associations into which the correct answer can be integrated when encountered.

When a student tries to recall the capital of Australia and guesses "Sydney," they activate knowledge about Australian geography, major cities, and related concepts. When they later learn that Canberra is the capital, this information connects to an already-active network rather than arriving in a relatively inactive mind.

Errors may enhance learning precisely because they're corrected. The discrepancy between what one believed (the incorrect guess) and reality (the correct answer) creates what some researchers call a prediction error signal. This signal may trigger enhanced attention and deeper processing of the corrective information.

The neuroscience of prediction error learning suggests that the brain is particularly attentive to information that violates expectations. An error followed by correction provides exactly this kind of expectation violation, potentially explaining why pretested items are remembered better.

Pretesting may help learners develop appropriate mental frameworks or schemas for organising incoming information. By considering what they might already know or how info rmation might be structured, learners create cognitive scaffoldingthat supports subsequent learning.

This account emphasises that pretesting isn't merely about individual question-answer pairs but about preparing the mind for a domain of knowledge.

Multiple studies show students who take pretests score significantly better (effect sizes d = 0.35-0.75) on final assessments than those who only study. Research across subjects from vocabulary to science concepts demonstrates consistent benefits when learners attempt questions before instruction. The effect has been replicated in laboratory and classroom settings with learners of various ages.

The pretesting effect has been demonstrated across diverse materials, settings, and populations.

In controlled laboratory experiments, pretesting consistently produces learning benefits compared to control conditions. Richland, Kornell, and Kao's foundational 2009 study found that reading passages accompanied by pretests led to better final test performance than reading alone, even for questions students initially answered incorrectly.

Subsequent studies have replicated and extended these findings using word pairs, trivia facts, scientific texts, and educational videos. The effect appears strong across different materials and test formats.

Critically, pretesting effects have also been demonstrated in authentic educational settings. Pan, Sana, and colleagues (2020) found that pretesting reduced mind wandering and enhanced learning from online lectures among university students.

A recent study by Hausman and Kornell (2023) examined pretesting in a university course over an entire academic semester. Students who were pretested on lecture content performed better on final exams than those who weren't, and importantly, the benefits extended beyond the specific pretested items to related material.

These classroom findings suggest the pretesting effect isn't merely a laboratory curiosity but a practically applicable instructional strategy.

Recent meta-analyses have synthesised findings across many studies. These analyses confirm that pretesting produces a reliable, moderate-sized benefit for learning. The effect is larger when feedback is provided than when it isn't, and the benefits persist over delayed testing.

Pretesting works best when questions target key concepts rather than trivial details, and when corrective feedback follows immediately after the pretest. The effect is stronger for conceptual understanding than rote memorization. Moderate difficulty questions that challenge but don't overwhelm students produce optimal results.

While pretesting generally enhances learning, several factors moderate its effectiveness.

Perhaps the most critical moderator is whether learners receive corrective feedback after pretesting. Without feedback, pretesting benefits are substantially reduced or eliminated. Learners need to encounter the correct answers to benefit from their initial guessing.

This requirement has practical implications: pretests should be low-stakes activities where correct answers are subsequently provided, not high-stakes assessments where errors go uncorrected.

Research suggests that immediate feedback following pretests may be more effective than delayed feedback, though some studies find pretesting benefits even with delays. When practical, providing correct answers shortly after pretest attempts maximises the potential for learning enhancement.

Some research suggests pretesting benefits are largest when the format of the pretest matches the format of the final assessment. If students will eventually take a short-answer test, short-answer pretests may be more effective than multiple-choice pretests.

However, substantial benefits have been found even when formats differ, so format matching shouldn't be considered essential.

Students with some relevant background knowledge may benefit more from pretesting than complete novices. Some prior knowledge provides material for the activation and search processes that support pretesting benefits. Complete novices may have no relevant knowledge to activate.

That said, pretesting benefits have been found even with novel material where prior specific knowledge is minimal. The activation of general schemas and frameworks may still occur.

Pretests that are moderately challenging, generating some errors but not complete failure, may be optimal. If pretests are too easy, they may not activate the mechanisms that drive pretesting benefits. If too difficult, students may disengage or become frustrated.

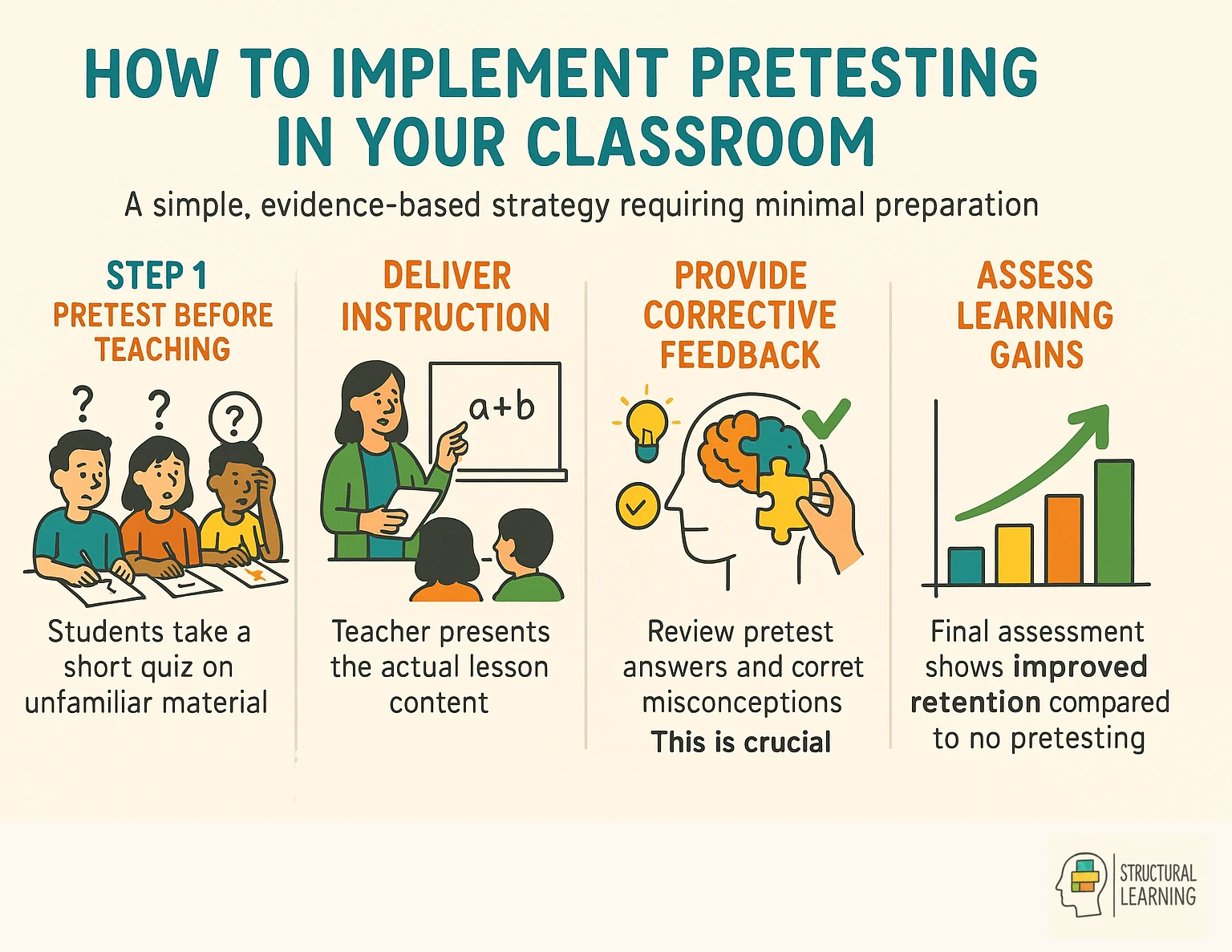

Use brief pretests at the beginning of lessons to prime students for incoming content. A few questions about today's topic, before any instruction begins, can activate relevant prior knowledge and focus attention.

These pretests should be framed as "thinking warm-ups" or "curious about what you already know" activities rather than graded assessments. The goal is activating minds, not evaluating knowledge.

Before students read textbook chapters or other texts, provide questions they should consider while reading. These function as pretests even if students don't formally record answers. The questions prime reading comprehension by highlighting what's important and creating purpose for reading.

Before showing educational videos or delivering lectures, present students with questions the content will address. Students attempt to answer before watching or listening. Research specifically supports this application, showing reduced mind wandering and enhanced learning.

Design homework that includes questions on upcoming topics alongside review of previous material. When students encounter questions they can't yet answer, they're being primed for the next lesson.

At the start of new units, give students a preview quiz covering material the unit will address. Collect the quizzes without grading, then return them at unit's end for students to see their growth. This approach uses pretesting while also providing motivating evidence of learning.

Before introducing new concepts through direct instruction, pose open questions that invite speculation. "Why do you think volcanoes are more common in some places than others?" Even incorrect speculation activates the mind for subsequent explanation.

Teachers reasonably worry that exposing students to errors will reinforce those mistakes. Research consistently shows otherwise: when errors are followed by corrective feedback, learning is enhanced, not hindered. The key is ensuring correction follows errors.

This finding applies to neurotypical learners. For some students with specific learning differences, errorless learning approaches may remain appropriate. Teachers should consider individual student needs.

Students may indeed find pretests initially frustrating if they expect to succeed and don't. Framing matters enormously. Present pretests as "brain priming" activities designed to get minds ready, not as assessments of what students should already know.

When students understand that getting answers wrong is expected and helpful, frustration typically diminishes. Consider sharing research on the pretesting effect with older students; metacognitive understanding of learning strategies enhances their effectiveness.

Pretesting effects have been demonstrated across subjects including science, history, language learning, and more. The effect appears general rather than subject-specific. However, implementation may vary; what constitutes effective pretests will differ by content area.

Pretests should be brief. A few minutes of priming provides substantial benefits without consuming significant instructional time. Three to five questions before a lesson or video is typically sufficient.

Pretesting complements strategies like retrieval practise, spaced repetition, and formative assessment by adding a preparatory phase to the learning cycle. It works particularly well before direct instruction, flipped classroom activities, or introducing new units. The technique enhances rather than replaces existing evidence-based practices.

The pretesting effect joins other research-backed strategies, including spaced practise, retrieval practise, and interleaving, as tools for enhancing learning. These strategies share common features: they introduce productive difficulties that feel harder in the moment but produce more durable learning.

Understanding why these strategies work helps teachers implement them effectively and explain them to students. When learners understand the purpose behind instructional choices, they're more likely to engage fully.

Pretesting offers particular advantages in ease of implementation. Unlike some research-informed strategies that require substantial restructuring of curriculum or teaching practise, pretesting can be incorporated incrementally with minimal disruption to existing approaches. A teacher can begin tomorrow by simply asking a few questions before introducing new content.

Frame pretests as learning opportunities by explaining that errors help the brain learn better, using phrases like 'productive mistakes' or 'learning attempts.' Celebrate effort and curiosity rather than correctness, and share research showing that initial errors lead to stronger learning. Create a classroom culture where mistakes are valued as part of the learning process.

While most students benefit from pretesting, some find error-making particularly aversive. Creating classroom cultures where errors are normalised and valued supports both pretesting effectiveness and broader learning goals.

Discuss the role of errors in learning explicitly. Share examples of successful people who learned from mistakes. Model comfortable responses to your own errors. These classroom community practices support pretesting while also promoting healthy academic mindsets more broadly.

For students with significant anxiety about errors, introduce pretesting gradually and ensure framing emphasises the learning function rather than the assessment function. As students experience pretesting benefits without negative consequences, comfort typically increases.

Pretesting pairs effectively with retrieval practise by creating multiple touchpoints with material, and with collaborative learning when students discuss pretest answers before instruction. It also enhances metacognition when students reflect on how their understanding changed from pretest to post-test. These combinations create powerful learning experiences that reinforce content through multiple pathways.

Pretesting works well in combination with other scientifically supported approaches.

Use pretests before instruction, then follow instruction with retrieval practise on the same material. This combination provides both priming benefits and consolidation benefits.

After pretests reveal what students don't know, instruction can explicitly address misconceptions and build on whatever relevant knowledge students demonstrated. This personalised elaboration enhances the value of pretest information.

Return to pretested material at spaced intervals, providing opportunities for retrieval practise that builds on the initial priming. The combination of pretesting and spaced practise may produce particularly durable learning.

The pretesting effect occurs when students demonstrate improved learning after attempting to respond to queries on subjects not covered yet studied. This phenomenon, discovered through extensive cognitive psychology research, shows that unsuccessful retrieval attempts actually prime the brain for more effective learning when the correct information is subsequently presented.

At its core, the pretesting effect relies on productive failure. When pupils generate incorrect answers or struggle to recall information they haven't learned, they create mental pathways that makethe correct information more memorable once encountered. Research by Richland, Kornell, and Kao (2009) demonstrated that students who took pretests scored 10-15% higher on final assessments compared to those who only studied the material traditionally.

In practical terms, imagine starting a Year 8 science lesson on photosynthesis by asking students to explain how plants make food, before any instruction. Most will provide incomplete or incorrect answers, perhaps mentioning sunlight and water but missing crucial details about chlorophyll or carbon dioxide. When you then teach the actual process, these students will pay closer attention to the gaps in their initial responses, creating stronger memories than if they'd simply listened passively to the explanation.

The effect works through three key mechanisms. First, pretesting activates prior knowledge, however limited, creating cognitive hooks for new information. Second, it generates curiosity about correct answers, increasing motivation and attention during instruction. Third, it helps students identify what they don't know, focusing their learning efforts more efficiently. Teachers can harness this by using quick diagnostic questions at the start of lessons, low-stakes quizzes before introducing new topics, or having students predict experimental outcomes before conducting practicals.

Understanding why pretesting enhances learning helps teachers use this technique more effectively. Research in cognitive psychology reveals several interconnected mechanisms that make unsuccessful retrieval attempts surprisingly beneficial for learning.

First, pretesting activates what researchers call "productive failure." When pupils attempt to answer questions about unfamiliar content, their brains engage in active problem-solving, creating tentative mental models. These initial attempts, though incorrect, establish cognitive scaffolding that makes the correct information more memorable when it's later presented. For instanc e, asking Year 7 students to predict what causes seasons before teaching about Earth's tilt prompts them to consider factors like distance from the sun, creating a framework for understanding the actual explanation.

Second, pretesting generates what psychologists term "hypercorrection." Students who confidently give wrong answers show enhanced memory for corrections, particularly when their incorrect responses seemed logical to them. This phenomenon is especially powerful in subjects like science and history, where misconceptions are common. A teacher might ask pupils to explain why heavy objects fall faster than light ones, knowing most will incorrectly agree with this statement. When students later learn about gravity's uniform acceleration, they remember it more strongly because it contradicts their confident prediction.

Additionally, pretesting triggers curiosity and increases attention during subsequent instruction. The cognitive scientist Robert Bjork describes this as "desirable difficulties"; the initial struggle makes learners more receptive to new information. Teachers can harness this by using quick pre-lesson quizzes on interactive whiteboards, or having students write three predictions about a topic on mini whiteboards before beginning instruction. The key is ensuring immediate or timely feedback, as the benefits depend on students recognising and correcting their initial errors.

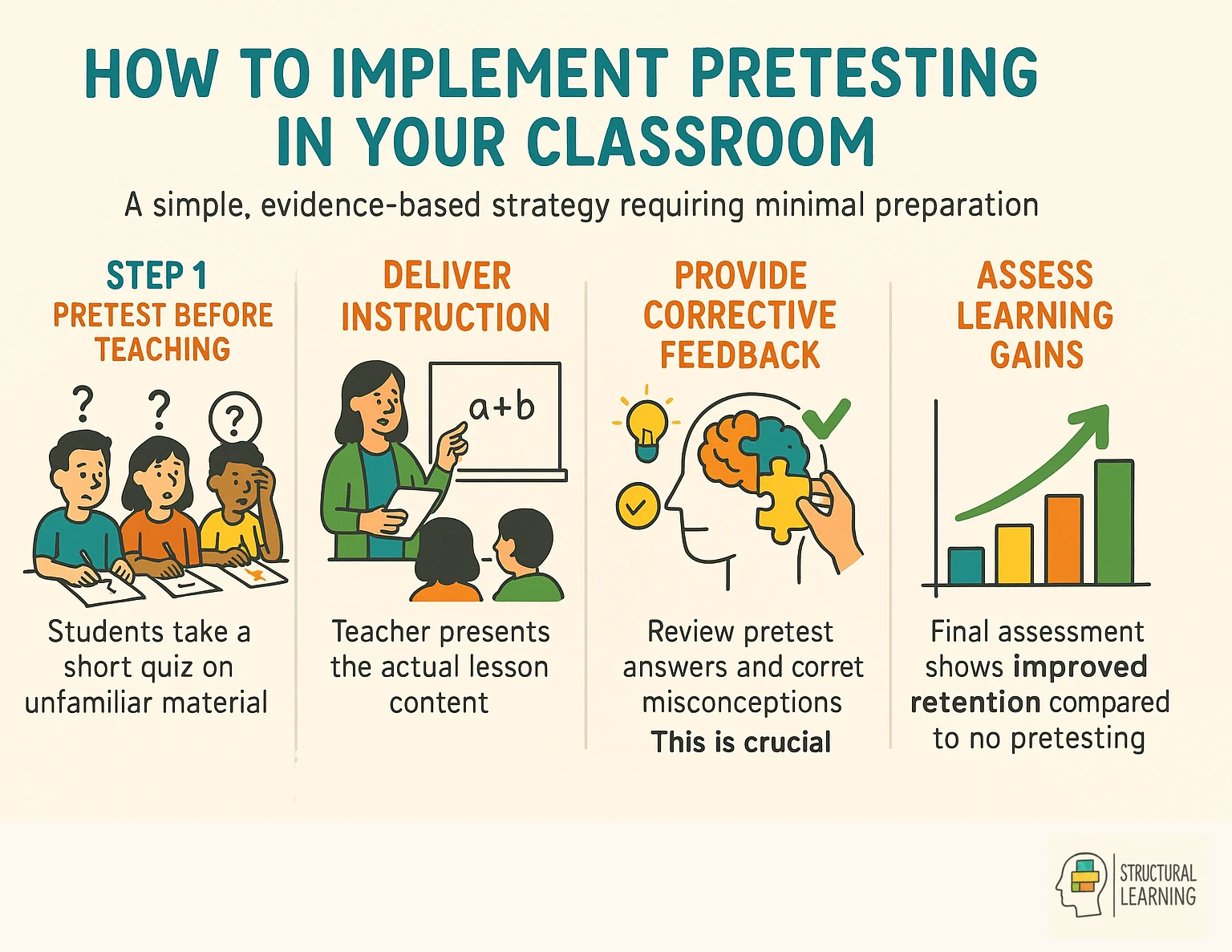

Incorporating pretesting into your teaching practise doesn't require extensive preparation or resources. The key lies in strategic timing and thoughtful question design. Start by introducing brief pretests at the beginning of new units or topics, focusing on core concepts students will encounter during the lesson.

For primary school teachers, consider using visual pretests before introducing new vocabulary or concepts. Show pupils images of unfamiliar animals before a biology lesson and ask them to predict characteristics based on appearance. This activates their existing knowledge whilst highlighting gaps. In secondary settings, begin chemistry lessons with prediction questions: "What might happen when we mix these two substances?" Even incorrect guesses prime students' attention for the correct explanation.

Digital tools can streamline the pretesting process. Use online quiz platforms to create quick diagnostic assessments that students complete as they enter the classroom. This provides immediate data about misconceptions whilst maximising instructional time. Alternatively, simple paper-based approaches work equally well; distribute index cards with three key questions about the upcoming content.

Research by Richland et al. (2009) demonstrates that pretesting is most effective when followed promptly by correct information. Therefore, structure your lessons to provide answers within the same session. After students attempt pretest questions, explicitly address each one during instruction, acknowledging common errors and explaining why certain answers are correct. This immediate feedback loop transforms incorrect responses into powerful learning opportunities.

Remember that pretesting should feel low-stakes and exploratory. Frame these activities as "curiosity checks" rather than assessments, encouraging students to make educated guesses without fear of judgement. This approach maintains the cognitive benefits whilst supporting a positive classroom environment where errors become stepping stones to understanding.

Key foundational papers include Richland et al. (2009) on unsuccessful retrieval attempts and Carpenter & Toftness (2017) on classroom applications of pretesting. The Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition and Educational Psychology Review regularly publish studies on this topic. Educational databases like ERIC provide free access to many pretesting effect studies.

The research base on pretesting continues to grow. These foundational and recent papers offer deeper insight into the phenomenon and its applications.

This influential paper demonstrated that taking a test on reading passage content before reading enhanced later memory, even for questions answered incorrectly on the pretest. The researchers showed that this effect went beyond attention-directing to include genuine enhancement of memory encoding. This paper sparked renewed interest in pretesting and established the basic approach used in subsequent research.

This comprehensive review synthesises findings from over 60 studies on prequestioning and pretesting. Pan and colleagues provide a three-stage framework for understanding underlying mechanisms, discuss moderating factors, and address practical implications for education. Essential reading for understanding the current state of pretesting research.

This study demonstrated pretesting benefits in a particularly challenging learning context: online video lectures. Students who answered pretest questions showed reduced mind wandering and better final test performance. The findings have obvious relevance for digital learning environments where maintaining attention is often difficult.

This classroom study tracked pretesting effects over a full semester in a university course. The researchers found that pretesting enhanced exam performance not only for pretested items but also for related, non-pretested material. These findings demonstrate that pretesting benefits transfer to authentic educational settings with real academic consequences.

This recent study examined how feedback timing and test timing influence pretesting effects. Results showed that pretesting benefits persisted even with delayed feedback and delayed testing, though immediate feedback produced larger effects. The findings suggest pretesting is strong across conditions commonly encountered in real educational settings.

---

The pretesting effect occurs when students attempt to reply to doubts regarding topics unseen yet studied, leading to improved learning when they later encounter that content. This phenomenon, first documented by researchers in the early 2000s, challenges conventional teaching wisdom that suggests errors should be minimised during learning.

At its core, the pretesting effect works through several psychological mechanisms. When pupils generate incorrect answers, they experience what cognitive scientists call "productive failure." This failure activates curiosity and creates a state of cognitive readiness; students become more attentive to the correct information when it's subsequently presented. Additionally, attempting to answer questions before instruction helps learners identify gaps in their knowledge, making them more receptive to filling those gaps.

In practise, this might involve giving Year 8 students a brief quiz on photosynthesis before beginning the unit. Though most will answer incorrectly, their attempts to reason through questions like "Why do plants appear green?" prime them to better understand light absorption and reflection when taught. Similarly, a history teacher might ask sixth formers to predict the causes of the English Civil War before any instruction, activating their prior knowledge whilst highlighting misconceptions to address.

Research by Richland, Kornell, and Kao (2009) demonstrated that pretested information is remembered approximately 10% better than non-pretested material, even when controlling for total study time. This effect appears strongest when pretests require generation rather than recognition, and when corrective feedback follows reasonably quickly, ideally within the same lesson or the following day.

Introducing pretesting into your teaching practise doesn't require extensive planning or resources. Start small by incorporating brief pretests at the beginning of new topics or units. For instance, before teaching photosynthesis in Year 9 science, present students with five multiple-choice questions about the process. Make it clear that you don't expect correct answers; this removes pressure and encourages genuine attempts.

Timing matters when implementing pretests. Research suggests administering them immediately before instruction maximises benefits, though pretesting a day or two ahead can also prove effective. In primary settings, verbal pretesting works particularly well. Before reading a story about Victorian Britain, ask pupils to predict what children's lives were like during that era. Their misconceptions become valuable teaching moments when you reveal the actual content.

Digital tools can streamline the pretesting process whilst providing immediate feedback. Platforms like Kahoot or Microsoft Forms allow you to create quick pretests that automatically highlight incorrect responses. However, low-tech approaches work equally well. Try 'think-pair-share' pretesting, where students first attempt questions individually, then discuss answers with a partner before whole-class feedback. This approach combines the benefits of pretesting with collaborative learning.

Remember to frame pretests positively. Explain to students that making mistakes before learning actually helps their brains prepare for new information. Some teachers use the phrase "productive confusion" to describe this process. Keep pretests brief, typically 3-7 questions, focusing on core concepts you'll address in the lesson. Most importantly, always provide corrective feedback immediately after the pretest or at the start of instruction; without this crucial step, the benefits diminish significantly.

Students often react negatively to pretests, viewing them as unfair assessments or pointless exercises. "Why are you testing us on something we haven't learnt yet?" is a common refrain in classrooms introducing this approach. This resistance is understandable; decades of educational conditioning have taught pupils that tests measure what they know, not what they don't. Breaking through this mindset requires careful framing and consistent messaging.

Research by Huelser and Metcalfe (2012) found that students initially prefer easier learning tasks and often underestimate the value of challenging activities like pretesting. To counter this, teachers should explicitly explain the purpose of pretests as learning tools, not evaluation instruments. Frame them as "learning check-ins" or "curiosity builders" rather than tests. One Year 9 science teacher in Manchester rebranded pretests as "prediction challenges," asking students to use their existing knowledge to make educated guesses about new topics. This simple reframing transformed student attitudes from anxiety to engagement.

Another effective strategy involves sharing the research evidence with students. Show them data demonstrating how pretesting improves learning, perhaps creating a classroom experiment where half the class pretests and half doesn't, then comparing outcomes. Secondary school students particularly respond well to being treated as partners in their learning process.

Finally, ensure pretests are genuinely low-stakes. Remove any connection to marks or grades, keep them brief (5-10 minutes maximum), and celebrate incorrect answers as valuable learning opportunities. When students see their teacher genuinely excited by wrong answers because they reveal learning possibilities, the classroom culture shifts. As one Birmingham teacher noted, "Once my students understood that getting pretest questions wrong actually helped their brains prepare for learning, they stopped dreading them and started requesting them."

Several cognitive theories help explain why incorrect answers during pretesting actually improve learning. The search set theory suggests that when students attempt to answer unfamiliar questions, they activate related knowledge networks in their brains. Even wrong guesses create mental pathways that make the correct information easier to encode when it's eventually presented. For instance, when Year 7 students guess incorrectly about photosynthesis before a biology lesson, they're unconsciously preparing their minds to notice and remember the accurate explanation.

The hypercorrection effect provides another compelling explanation. Research shows that students pay closer attention to feedback when they've made high-confidence errors. A pupil who confidently declares that Henry VIII had eight wives will experience surprise when learning the correct answer, and this emotional response strengthens memory formation. Teachers can amplify this effect by asking students to rate their confidence levels alongside their pretest answers, turning misconceptions into powerful learning opportunities.

Error-driven learning theory suggests our brains are particularly attuned to noticing discrepancies between predictions and reality. When students generate incorrect responses during pretesting, they create expectations that clash with the subsequent correct information. This cognitive conflict acts like a highlighter pen for the brain, marking important content for deeper processing. In practical terms, this means a quick five-question quiz about the water cycle before teaching will help students notice and remember key concepts they initially misunderstood.

Understanding these mechanisms helps teachers design more effective pretests. Rather than avoiding topics where students hold strong misconceptions, educators should deliberately target these areas. The cognitive work students do whilst generating wrong answers, combined with the surprise of discovering correct information, creates ideal conditions for durable learning.

Researchers typically investigate the pretesting effect through carefully controlled classroom experiments. Students are divided into groups, with one attempting questions about unfamiliar material whilst the control group engages in alternative activities like reading or reviewing related content. After this initial phase, all students receive the same instruction, followed by a final test to measure learning outcomes.

The most revealing studies use materials from actual school curricula, making findings directly applicable to classroom practise. For instance, researchers at UCLA tested secondary students on science concepts they hadn't studied, finding that those who attempted pretest questions scored 10-15% higher on final assessments than peers who simply read introductory texts. Similar experiments with primary school vocabulary lessons showed even stronger effects, with pretested pupils remembering twice as many new words after one week.

Teachers can replicate these research conditions in their own classrooms to observe the effect firsthand. Start with a simple experiment: before introducing a new history topic, give half your class three challenging questions whilst the other half reviews previously learned material. After teaching the lesson, test both groups on the new content. Many teachers report surprise at how consistently the pretested group outperforms their peers, particularly on questions requiring deeper understanding rather than rote memorisation.

Timing proves crucial in these studies. Research indicates that immediate feedback isn't necessary; the cognitive benefit comes from the attempt itself. Most experiments show optimal results when pretesting occurs 5-10 minutes before instruction, though effects remain significant even with delays of up to 24 hours. This flexibility allows teachers to use pretests as homework assignments or morning warm-up activities without diminishing their effectiveness.

When implementing pretesting in your classroom, tracking its effectiveness requires more than simply comparing test scores. Research shows that pretested material demonstrates stronger retention over time, with students maintaining up to 40% more information after several weeks compared to traditionally taught content. Teachers can measure this enhanced learning through delayed assessments, spacing them out at intervals of one week, one month, and one term after initial instruction.

Transfer of learning, where students apply pretested concepts to new contexts, provides another crucial metric. For instance, a Year 8 science teacher might pretest students on photosynthesis principles, then later assess whether they can apply this knowledge to explain how deforestation affects oxygen levels. Studies indicate that pretested students show 25% better performance on these transfer tasks, suggesting deeper conceptual understanding rather than surface memorisation.

Practical measurement strategies include using exit tickets to compare immediate comprehension between pretested and non-pretested topics within the same lesson. Teachers might also create parallel assessment questions; one set testing direct recall and another requiring application to novel scenarios. A particularly effective approach involves having students explain concepts to peers, as pretested pupils typically provide more detailed explanations with fewer misconceptions.

Beyond traditional assessments, observing classroom discussions reveals qualitative differences in learning quality. Students who experienced pretesting often ask more sophisticated questions and make connections between topics independently. Recording these observations in a simple tracking sheet helps teachers identify which subject areas benefit most from pretesting, allowing for targeted implementation where it yields the greatest impact on pupil understanding and long-term retention.

The pretesting effect occurs when students are tested on material they haven't yet learned, which enhances their subsequent learning of that content even when they answer incorrectly. Unlike regular testing which assesses already-studied material to strengthen retrieval, pretesting works through different mechanisms such as focusing attention and activating curiosity about unknown information.

Teachers can simply give students a brief quiz on upcoming topics before beginning instruction, allowing students to guess answers they don't know. The key is to follow up immediately with corrective feedback during the lesson, as the pretesting benefits cannot be realised without students learning the correct information after their initial attempts.

Incorrect answers on pretests work through several mechanisms: they direct students' attention to what they don't know, activate curiosity about the correct answers, and create mental frameworks for organising new information. The errors also generate prediction error signals in the brain, which triggers enhanced attention when the correct information is subsequently presented.

Pretesting research typically uses simpler materials such as definitions, facts, or short-answer questions rather than complex problem-solving tasks. The focus should be on test-like retrieval attempts that can be quickly administered and easily followed up with corrective feedback during instruction.

Research shows that pretesting doesn't reinforce errors when followed by corrective feedback, challenging the traditional 'errorless learning' approach. The key is ensuring students receive the correct information after pretesting, as the benefits depend entirely on this corrective element being present.

The article suggests that corrective feedback should follow relatively quickly after pretesting, typically during the subsequent instruction on that topic. The pretesting effect works by creating a 'need to know' state that focuses attention, so the correct information should be provided whilst students' curiosity and attention are still heightened.

Whilst the article demonstrates the pretesting effect across various studies, it notes that researchers are still investigating boundary conditions and practical applications. The effect appears most strong when students can make educated guesses and when corrective feedback is provided, suggesting it may work across different contexts where these conditions are met.

These peer-reviewed studies provide the research foundation for the strategies discussed in this article:

Flipped classroom: rising motivation of new generation or challengeable way of studying on higher education level (case study in Georgia) View study ↗

3 citations

Ana Chankvetadze (2024)

This Georgian case study explores whether flipped classroom methods, where students learn content at home and apply it in class, can effectively motivate today's digital-native students in higher education. The research examines both the potential benefits and challenges of this approach for engaging students who have grown up with technology. Teachers considering flipping their classrooms will find practical insights about what works and what obstacles to expect when implementing this increasingly popular teaching method.

The Effect of Teaching Quality and Campus Facilities on Student Learning Motivation View study ↗

6 citations

Siskawaty Yahya et al. (2023)

A study of 93 university students revealed that both the quality of teaching and the physical learning environment significantly impact student motivation to learn. The research confirms what many educators suspect: that excellent instruction combined with well-maintained, properly equipped facilities creates the optimal conditions for student engagement. This finding reinforces the importance of professional development for teachers while also highlighting how classroom conditions and resources directly affect student success.

The effect of learning strategies adopted in K12 schools on student learning in massive open online courses View study ↗

5 citations

Shan Tang et al. (2023)

This mixed-methods study examined whether traditional classroom learning strategies effectively support secondary students when they participate in massive open online courses (MOOCs). The research addresses growing concerns about how to help K-12 students succeed in online learning environments that were originally designed for self-directed adult learners. Teachers and administrators implementing online or blended learning programmes will find valuable insights about which instructional strategies transfer successfully to digital platforms and which require modification.

Testing students on material they haven't yet learned might seem counterproductive. Why quiz pupils on content they're bound to get wrong? Yet a growing body of research reveals something unexpected: unsuccessful retrieval attempts before learning actually enhance how well students acquire and retain new information. This counterintuitive finding, known as the pretesting effect, suggests that errors made in the right context don't hinder learning; they prepare the mind for it.

testing effect in education" loading="lazy">

testing effect in education" loading="lazy">The implications for classroom practise are substantial. In 2025, as educators seek evidence-based strategies to strengthen student learning, pretesting emerges as a simple, low-stakes intervention that requires minimal preparation yet produces meaningful gains. Unlike the testing effect, which focuses on retrieving already-learned material, the pretesting effect concerns what happens when learners attempt to answer questions about material they haven't encountered.

Key Takeaways

Your Classroom infographic for The Pretesting Effect: Why Testing Before Teaching Works" loading="lazy">

Your Classroom infographic for The Pretesting Effect: Why Testing Before Teaching Works" loading="lazy">

The pretesting effect, also called the prequestioning effect or errorful generation effect, refers to the finding that taking a test before learning new information leads to stronger memory and understanding of that information than simply studying without pretesting. Crucially, this benefit occurs even when, indeed especially when, learners answer pretest questions incorrectly.

Consider a typical demonstration: one group of students takes a short quiz on a topic they haven't yet studied, getting most answers wrong. A second group spends the same time doing an unrelated activity. Both groups then receive identical instruction on the topic. When tested afterwards, the pretested group consistently outperforms the control group, despite their initial errors.

This phenomenon challenges traditional assumptions about learning. The errorless learning tradition, influenced by behaviourist psychology, held that exposing learners to errors would reinforce those mistakes. Pretesting research reveals a different picture: when errors are followed by corrective information, they can actually enhance rather than hinder learning.

The term "pretesting effect" gained prominence following influential studies by Richland, Kornell, and Kao in 2009, though related findings appeared in earlier educational psychology research from the 1960s and 1970s. Recent years have seen a surge of interest, with researchers investigating boundary conditions, underlying mechanisms, and practical applications.

Pretesting involves testing students on material they haven't learned yet, while regular testing assesses already-studied content. The pretesting effect enhances future learning through incorrect attempts, whereas the testing effect strengthens retrieval of existing knowledge. Both improve learning but work through different cognitive mechanisms.

Understanding the pretesting effect requires distinguishing it from related phenomena in the learning sciences.

The well-established testing effect concerns how retrieving learned information strengthens memory for that information. When students successfully recall material on practise tests, this act of retrieval enhances later retention compared to restudying. The testing effect depends on successful retrieval of previously learned material.

The pretesting effect operates differently. Here, retrieval attempts occur before learning, when correct retrieval is impossible. Students generate guesses, typically incorrect ones. Yet subsequent learning is enhanced. The mechanisms must therefore differ from those underlying the standard testing effect.

Manu Kapur's research on productive failure examines how initial struggle with problems before instruction can enhance learning, particularly for complex conceptual material. While related to pretesting, productive failure typically involves more extended problem-solving attempts and emphasises the role of generating multiple solution strategies.

Pretesting studies often use simpler materials, such as definitions, facts, or short-answer questions, and focus specifically on the effects of test-like retrieval attempts. The overlap between these literatures is substantial, but they emerged from different research traditions and emphasise different aspects of "learning from errors."

Robert Bjork's concept of desirable difficulties provides a broader framework for understanding pretesting. Desirable difficulties are learning conditions that feel harder but produce more durable, transferable learning. Pretesting fits within this framework: the initial struggle and errors create difficulty that ultimately serves learning.

Researchers have proposed several mechanisms to explain why unsuccessful retrieval attempts enhance subsequent learning. These explanations aren't mutually exclusive; multiple processes likely contribute to the effect.

One prominent explanation holds that pretesting directs attention towards incoming information. When students attempt to answer questions and discover they cannot, they become alert to the answers when they subsequently encounter the material. The pretest essentially highlights what they don't know, creating a mental "need to know" that focuses attention during learning.

Supporting this account, studies have found that pretesting reduces mind wandering during lectures and video presentations. Students who take pretests report higher attention levels during subsequent instruction. This attentional focusing may be particularly valuable in contexts prone to distraction.

Related to attention, pretesting may activate curiosity. When students generate a guess and await confirmation or correction, they become invested in learning the answer. This curiosity provides motivation that enhances encoding of the correct information.

Information presented as an answer to a question one has already contemplated may be processed more deeply than the same information presented without such priming. The learner's mind is already engaged with the relevant conceptual territory.

Attempting to answer a pretest question activates related knowledge in long-term memory. Even when the correct answer isn't retrieved, semantically related concepts become active. This activation creates a richer network of associations into which the correct answer can be integrated when encountered.

When a student tries to recall the capital of Australia and guesses "Sydney," they activate knowledge about Australian geography, major cities, and related concepts. When they later learn that Canberra is the capital, this information connects to an already-active network rather than arriving in a relatively inactive mind.

Errors may enhance learning precisely because they're corrected. The discrepancy between what one believed (the incorrect guess) and reality (the correct answer) creates what some researchers call a prediction error signal. This signal may trigger enhanced attention and deeper processing of the corrective information.

The neuroscience of prediction error learning suggests that the brain is particularly attentive to information that violates expectations. An error followed by correction provides exactly this kind of expectation violation, potentially explaining why pretested items are remembered better.

Pretesting may help learners develop appropriate mental frameworks or schemas for organising incoming information. By considering what they might already know or how info rmation might be structured, learners create cognitive scaffoldingthat supports subsequent learning.

This account emphasises that pretesting isn't merely about individual question-answer pairs but about preparing the mind for a domain of knowledge.

Multiple studies show students who take pretests score significantly better (effect sizes d = 0.35-0.75) on final assessments than those who only study. Research across subjects from vocabulary to science concepts demonstrates consistent benefits when learners attempt questions before instruction. The effect has been replicated in laboratory and classroom settings with learners of various ages.

The pretesting effect has been demonstrated across diverse materials, settings, and populations.

In controlled laboratory experiments, pretesting consistently produces learning benefits compared to control conditions. Richland, Kornell, and Kao's foundational 2009 study found that reading passages accompanied by pretests led to better final test performance than reading alone, even for questions students initially answered incorrectly.

Subsequent studies have replicated and extended these findings using word pairs, trivia facts, scientific texts, and educational videos. The effect appears strong across different materials and test formats.

Critically, pretesting effects have also been demonstrated in authentic educational settings. Pan, Sana, and colleagues (2020) found that pretesting reduced mind wandering and enhanced learning from online lectures among university students.

A recent study by Hausman and Kornell (2023) examined pretesting in a university course over an entire academic semester. Students who were pretested on lecture content performed better on final exams than those who weren't, and importantly, the benefits extended beyond the specific pretested items to related material.

These classroom findings suggest the pretesting effect isn't merely a laboratory curiosity but a practically applicable instructional strategy.

Recent meta-analyses have synthesised findings across many studies. These analyses confirm that pretesting produces a reliable, moderate-sized benefit for learning. The effect is larger when feedback is provided than when it isn't, and the benefits persist over delayed testing.

Pretesting works best when questions target key concepts rather than trivial details, and when corrective feedback follows immediately after the pretest. The effect is stronger for conceptual understanding than rote memorization. Moderate difficulty questions that challenge but don't overwhelm students produce optimal results.

While pretesting generally enhances learning, several factors moderate its effectiveness.

Perhaps the most critical moderator is whether learners receive corrective feedback after pretesting. Without feedback, pretesting benefits are substantially reduced or eliminated. Learners need to encounter the correct answers to benefit from their initial guessing.

This requirement has practical implications: pretests should be low-stakes activities where correct answers are subsequently provided, not high-stakes assessments where errors go uncorrected.

Research suggests that immediate feedback following pretests may be more effective than delayed feedback, though some studies find pretesting benefits even with delays. When practical, providing correct answers shortly after pretest attempts maximises the potential for learning enhancement.

Some research suggests pretesting benefits are largest when the format of the pretest matches the format of the final assessment. If students will eventually take a short-answer test, short-answer pretests may be more effective than multiple-choice pretests.

However, substantial benefits have been found even when formats differ, so format matching shouldn't be considered essential.

Students with some relevant background knowledge may benefit more from pretesting than complete novices. Some prior knowledge provides material for the activation and search processes that support pretesting benefits. Complete novices may have no relevant knowledge to activate.

That said, pretesting benefits have been found even with novel material where prior specific knowledge is minimal. The activation of general schemas and frameworks may still occur.

Pretests that are moderately challenging, generating some errors but not complete failure, may be optimal. If pretests are too easy, they may not activate the mechanisms that drive pretesting benefits. If too difficult, students may disengage or become frustrated.

Use brief pretests at the beginning of lessons to prime students for incoming content. A few questions about today's topic, before any instruction begins, can activate relevant prior knowledge and focus attention.

These pretests should be framed as "thinking warm-ups" or "curious about what you already know" activities rather than graded assessments. The goal is activating minds, not evaluating knowledge.

Before students read textbook chapters or other texts, provide questions they should consider while reading. These function as pretests even if students don't formally record answers. The questions prime reading comprehension by highlighting what's important and creating purpose for reading.

Before showing educational videos or delivering lectures, present students with questions the content will address. Students attempt to answer before watching or listening. Research specifically supports this application, showing reduced mind wandering and enhanced learning.

Design homework that includes questions on upcoming topics alongside review of previous material. When students encounter questions they can't yet answer, they're being primed for the next lesson.

At the start of new units, give students a preview quiz covering material the unit will address. Collect the quizzes without grading, then return them at unit's end for students to see their growth. This approach uses pretesting while also providing motivating evidence of learning.

Before introducing new concepts through direct instruction, pose open questions that invite speculation. "Why do you think volcanoes are more common in some places than others?" Even incorrect speculation activates the mind for subsequent explanation.

Teachers reasonably worry that exposing students to errors will reinforce those mistakes. Research consistently shows otherwise: when errors are followed by corrective feedback, learning is enhanced, not hindered. The key is ensuring correction follows errors.

This finding applies to neurotypical learners. For some students with specific learning differences, errorless learning approaches may remain appropriate. Teachers should consider individual student needs.

Students may indeed find pretests initially frustrating if they expect to succeed and don't. Framing matters enormously. Present pretests as "brain priming" activities designed to get minds ready, not as assessments of what students should already know.

When students understand that getting answers wrong is expected and helpful, frustration typically diminishes. Consider sharing research on the pretesting effect with older students; metacognitive understanding of learning strategies enhances their effectiveness.

Pretesting effects have been demonstrated across subjects including science, history, language learning, and more. The effect appears general rather than subject-specific. However, implementation may vary; what constitutes effective pretests will differ by content area.

Pretests should be brief. A few minutes of priming provides substantial benefits without consuming significant instructional time. Three to five questions before a lesson or video is typically sufficient.

Pretesting complements strategies like retrieval practise, spaced repetition, and formative assessment by adding a preparatory phase to the learning cycle. It works particularly well before direct instruction, flipped classroom activities, or introducing new units. The technique enhances rather than replaces existing evidence-based practices.

The pretesting effect joins other research-backed strategies, including spaced practise, retrieval practise, and interleaving, as tools for enhancing learning. These strategies share common features: they introduce productive difficulties that feel harder in the moment but produce more durable learning.

Understanding why these strategies work helps teachers implement them effectively and explain them to students. When learners understand the purpose behind instructional choices, they're more likely to engage fully.

Pretesting offers particular advantages in ease of implementation. Unlike some research-informed strategies that require substantial restructuring of curriculum or teaching practise, pretesting can be incorporated incrementally with minimal disruption to existing approaches. A teacher can begin tomorrow by simply asking a few questions before introducing new content.

Frame pretests as learning opportunities by explaining that errors help the brain learn better, using phrases like 'productive mistakes' or 'learning attempts.' Celebrate effort and curiosity rather than correctness, and share research showing that initial errors lead to stronger learning. Create a classroom culture where mistakes are valued as part of the learning process.

While most students benefit from pretesting, some find error-making particularly aversive. Creating classroom cultures where errors are normalised and valued supports both pretesting effectiveness and broader learning goals.

Discuss the role of errors in learning explicitly. Share examples of successful people who learned from mistakes. Model comfortable responses to your own errors. These classroom community practices support pretesting while also promoting healthy academic mindsets more broadly.

For students with significant anxiety about errors, introduce pretesting gradually and ensure framing emphasises the learning function rather than the assessment function. As students experience pretesting benefits without negative consequences, comfort typically increases.

Pretesting pairs effectively with retrieval practise by creating multiple touchpoints with material, and with collaborative learning when students discuss pretest answers before instruction. It also enhances metacognition when students reflect on how their understanding changed from pretest to post-test. These combinations create powerful learning experiences that reinforce content through multiple pathways.

Pretesting works well in combination with other scientifically supported approaches.

Use pretests before instruction, then follow instruction with retrieval practise on the same material. This combination provides both priming benefits and consolidation benefits.

After pretests reveal what students don't know, instruction can explicitly address misconceptions and build on whatever relevant knowledge students demonstrated. This personalised elaboration enhances the value of pretest information.

Return to pretested material at spaced intervals, providing opportunities for retrieval practise that builds on the initial priming. The combination of pretesting and spaced practise may produce particularly durable learning.

The pretesting effect occurs when students demonstrate improved learning after attempting to respond to queries on subjects not covered yet studied. This phenomenon, discovered through extensive cognitive psychology research, shows that unsuccessful retrieval attempts actually prime the brain for more effective learning when the correct information is subsequently presented.

At its core, the pretesting effect relies on productive failure. When pupils generate incorrect answers or struggle to recall information they haven't learned, they create mental pathways that makethe correct information more memorable once encountered. Research by Richland, Kornell, and Kao (2009) demonstrated that students who took pretests scored 10-15% higher on final assessments compared to those who only studied the material traditionally.

In practical terms, imagine starting a Year 8 science lesson on photosynthesis by asking students to explain how plants make food, before any instruction. Most will provide incomplete or incorrect answers, perhaps mentioning sunlight and water but missing crucial details about chlorophyll or carbon dioxide. When you then teach the actual process, these students will pay closer attention to the gaps in their initial responses, creating stronger memories than if they'd simply listened passively to the explanation.

The effect works through three key mechanisms. First, pretesting activates prior knowledge, however limited, creating cognitive hooks for new information. Second, it generates curiosity about correct answers, increasing motivation and attention during instruction. Third, it helps students identify what they don't know, focusing their learning efforts more efficiently. Teachers can harness this by using quick diagnostic questions at the start of lessons, low-stakes quizzes before introducing new topics, or having students predict experimental outcomes before conducting practicals.

Understanding why pretesting enhances learning helps teachers use this technique more effectively. Research in cognitive psychology reveals several interconnected mechanisms that make unsuccessful retrieval attempts surprisingly beneficial for learning.

First, pretesting activates what researchers call "productive failure." When pupils attempt to answer questions about unfamiliar content, their brains engage in active problem-solving, creating tentative mental models. These initial attempts, though incorrect, establish cognitive scaffolding that makes the correct information more memorable when it's later presented. For instanc e, asking Year 7 students to predict what causes seasons before teaching about Earth's tilt prompts them to consider factors like distance from the sun, creating a framework for understanding the actual explanation.

Second, pretesting generates what psychologists term "hypercorrection." Students who confidently give wrong answers show enhanced memory for corrections, particularly when their incorrect responses seemed logical to them. This phenomenon is especially powerful in subjects like science and history, where misconceptions are common. A teacher might ask pupils to explain why heavy objects fall faster than light ones, knowing most will incorrectly agree with this statement. When students later learn about gravity's uniform acceleration, they remember it more strongly because it contradicts their confident prediction.

Additionally, pretesting triggers curiosity and increases attention during subsequent instruction. The cognitive scientist Robert Bjork describes this as "desirable difficulties"; the initial struggle makes learners more receptive to new information. Teachers can harness this by using quick pre-lesson quizzes on interactive whiteboards, or having students write three predictions about a topic on mini whiteboards before beginning instruction. The key is ensuring immediate or timely feedback, as the benefits depend on students recognising and correcting their initial errors.

Incorporating pretesting into your teaching practise doesn't require extensive preparation or resources. The key lies in strategic timing and thoughtful question design. Start by introducing brief pretests at the beginning of new units or topics, focusing on core concepts students will encounter during the lesson.

For primary school teachers, consider using visual pretests before introducing new vocabulary or concepts. Show pupils images of unfamiliar animals before a biology lesson and ask them to predict characteristics based on appearance. This activates their existing knowledge whilst highlighting gaps. In secondary settings, begin chemistry lessons with prediction questions: "What might happen when we mix these two substances?" Even incorrect guesses prime students' attention for the correct explanation.

Digital tools can streamline the pretesting process. Use online quiz platforms to create quick diagnostic assessments that students complete as they enter the classroom. This provides immediate data about misconceptions whilst maximising instructional time. Alternatively, simple paper-based approaches work equally well; distribute index cards with three key questions about the upcoming content.

Research by Richland et al. (2009) demonstrates that pretesting is most effective when followed promptly by correct information. Therefore, structure your lessons to provide answers within the same session. After students attempt pretest questions, explicitly address each one during instruction, acknowledging common errors and explaining why certain answers are correct. This immediate feedback loop transforms incorrect responses into powerful learning opportunities.

Remember that pretesting should feel low-stakes and exploratory. Frame these activities as "curiosity checks" rather than assessments, encouraging students to make educated guesses without fear of judgement. This approach maintains the cognitive benefits whilst supporting a positive classroom environment where errors become stepping stones to understanding.

Key foundational papers include Richland et al. (2009) on unsuccessful retrieval attempts and Carpenter & Toftness (2017) on classroom applications of pretesting. The Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition and Educational Psychology Review regularly publish studies on this topic. Educational databases like ERIC provide free access to many pretesting effect studies.

The research base on pretesting continues to grow. These foundational and recent papers offer deeper insight into the phenomenon and its applications.

This influential paper demonstrated that taking a test on reading passage content before reading enhanced later memory, even for questions answered incorrectly on the pretest. The researchers showed that this effect went beyond attention-directing to include genuine enhancement of memory encoding. This paper sparked renewed interest in pretesting and established the basic approach used in subsequent research.

This comprehensive review synthesises findings from over 60 studies on prequestioning and pretesting. Pan and colleagues provide a three-stage framework for understanding underlying mechanisms, discuss moderating factors, and address practical implications for education. Essential reading for understanding the current state of pretesting research.

This study demonstrated pretesting benefits in a particularly challenging learning context: online video lectures. Students who answered pretest questions showed reduced mind wandering and better final test performance. The findings have obvious relevance for digital learning environments where maintaining attention is often difficult.

This classroom study tracked pretesting effects over a full semester in a university course. The researchers found that pretesting enhanced exam performance not only for pretested items but also for related, non-pretested material. These findings demonstrate that pretesting benefits transfer to authentic educational settings with real academic consequences.

This recent study examined how feedback timing and test timing influence pretesting effects. Results showed that pretesting benefits persisted even with delayed feedback and delayed testing, though immediate feedback produced larger effects. The findings suggest pretesting is strong across conditions commonly encountered in real educational settings.

---

The pretesting effect occurs when students attempt to reply to doubts regarding topics unseen yet studied, leading to improved learning when they later encounter that content. This phenomenon, first documented by researchers in the early 2000s, challenges conventional teaching wisdom that suggests errors should be minimised during learning.

At its core, the pretesting effect works through several psychological mechanisms. When pupils generate incorrect answers, they experience what cognitive scientists call "productive failure." This failure activates curiosity and creates a state of cognitive readiness; students become more attentive to the correct information when it's subsequently presented. Additionally, attempting to answer questions before instruction helps learners identify gaps in their knowledge, making them more receptive to filling those gaps.

In practise, this might involve giving Year 8 students a brief quiz on photosynthesis before beginning the unit. Though most will answer incorrectly, their attempts to reason through questions like "Why do plants appear green?" prime them to better understand light absorption and reflection when taught. Similarly, a history teacher might ask sixth formers to predict the causes of the English Civil War before any instruction, activating their prior knowledge whilst highlighting misconceptions to address.

Research by Richland, Kornell, and Kao (2009) demonstrated that pretested information is remembered approximately 10% better than non-pretested material, even when controlling for total study time. This effect appears strongest when pretests require generation rather than recognition, and when corrective feedback follows reasonably quickly, ideally within the same lesson or the following day.

Introducing pretesting into your teaching practise doesn't require extensive planning or resources. Start small by incorporating brief pretests at the beginning of new topics or units. For instance, before teaching photosynthesis in Year 9 science, present students with five multiple-choice questions about the process. Make it clear that you don't expect correct answers; this removes pressure and encourages genuine attempts.

Timing matters when implementing pretests. Research suggests administering them immediately before instruction maximises benefits, though pretesting a day or two ahead can also prove effective. In primary settings, verbal pretesting works particularly well. Before reading a story about Victorian Britain, ask pupils to predict what children's lives were like during that era. Their misconceptions become valuable teaching moments when you reveal the actual content.

Digital tools can streamline the pretesting process whilst providing immediate feedback. Platforms like Kahoot or Microsoft Forms allow you to create quick pretests that automatically highlight incorrect responses. However, low-tech approaches work equally well. Try 'think-pair-share' pretesting, where students first attempt questions individually, then discuss answers with a partner before whole-class feedback. This approach combines the benefits of pretesting with collaborative learning.

Remember to frame pretests positively. Explain to students that making mistakes before learning actually helps their brains prepare for new information. Some teachers use the phrase "productive confusion" to describe this process. Keep pretests brief, typically 3-7 questions, focusing on core concepts you'll address in the lesson. Most importantly, always provide corrective feedback immediately after the pretest or at the start of instruction; without this crucial step, the benefits diminish significantly.

Students often react negatively to pretests, viewing them as unfair assessments or pointless exercises. "Why are you testing us on something we haven't learnt yet?" is a common refrain in classrooms introducing this approach. This resistance is understandable; decades of educational conditioning have taught pupils that tests measure what they know, not what they don't. Breaking through this mindset requires careful framing and consistent messaging.

Research by Huelser and Metcalfe (2012) found that students initially prefer easier learning tasks and often underestimate the value of challenging activities like pretesting. To counter this, teachers should explicitly explain the purpose of pretests as learning tools, not evaluation instruments. Frame them as "learning check-ins" or "curiosity builders" rather than tests. One Year 9 science teacher in Manchester rebranded pretests as "prediction challenges," asking students to use their existing knowledge to make educated guesses about new topics. This simple reframing transformed student attitudes from anxiety to engagement.

Another effective strategy involves sharing the research evidence with students. Show them data demonstrating how pretesting improves learning, perhaps creating a classroom experiment where half the class pretests and half doesn't, then comparing outcomes. Secondary school students particularly respond well to being treated as partners in their learning process.

Finally, ensure pretests are genuinely low-stakes. Remove any connection to marks or grades, keep them brief (5-10 minutes maximum), and celebrate incorrect answers as valuable learning opportunities. When students see their teacher genuinely excited by wrong answers because they reveal learning possibilities, the classroom culture shifts. As one Birmingham teacher noted, "Once my students understood that getting pretest questions wrong actually helped their brains prepare for learning, they stopped dreading them and started requesting them."

Several cognitive theories help explain why incorrect answers during pretesting actually improve learning. The search set theory suggests that when students attempt to answer unfamiliar questions, they activate related knowledge networks in their brains. Even wrong guesses create mental pathways that make the correct information easier to encode when it's eventually presented. For instance, when Year 7 students guess incorrectly about photosynthesis before a biology lesson, they're unconsciously preparing their minds to notice and remember the accurate explanation.

The hypercorrection effect provides another compelling explanation. Research shows that students pay closer attention to feedback when they've made high-confidence errors. A pupil who confidently declares that Henry VIII had eight wives will experience surprise when learning the correct answer, and this emotional response strengthens memory formation. Teachers can amplify this effect by asking students to rate their confidence levels alongside their pretest answers, turning misconceptions into powerful learning opportunities.