Transfer of Learning: A Complete Guide for Teachers

Explore how transfer of learning affects students' ability to apply knowledge in new contexts and learn effective strategies to enhance their understanding.

Explore how transfer of learning affects students' ability to apply knowledge in new contexts and learn effective strategies to enhance their understanding.

Transfer of learning is the ability to apply knowledge, skills, and strategies acquired in one context to new and different situations. As a teacher, mastering how to creates this skill in your students is crucial for helping them move beyond rote memorisation to genuine understanding they can use throughout their lives. This comprehensive guide provides you with research-backed strategies, practical classroom techniques, and proven methods to transform how your students connect and apply their learning. Discover why some lessons stick whilst others are quickly forgotten, and learn exactly how to design experiences that build truly transferable knowledge.

Key Takeaways

Transfer of learning describes the process by which knowledge, skills, or strategies acquired in one situation influence performance in another. When a student learns to write persuasive essays in English and then successfully applies those argumentation skills in history, transfer has occurred. When a child masters addition facts and uses that knowledge to understand multiplication, transfer is at work.

The concept dates back to Edward Thorndike and Robert Woodworth's research in 1901, which challenged earlier assumptions about mental discipline. Before their work, educators believed that studying rigorous subjects like Latin or geometry would train the mind in ways that transferred broadly to other domains. Thorndike and Woodworth found something more nuanced: transfer depends heavily on the degree to which two situations share common elements. This cognitive load theory perspective suggests that identical elements between learning and application contexts predict how readily transfer will occur.

More contemporary researchers, particularly David Perkins and Gavriel Salomon, have expanded our understanding considerably. They distinguish between what they call "low road" and "high road" transfer mechanisms, each operating through different cognitive pathways.

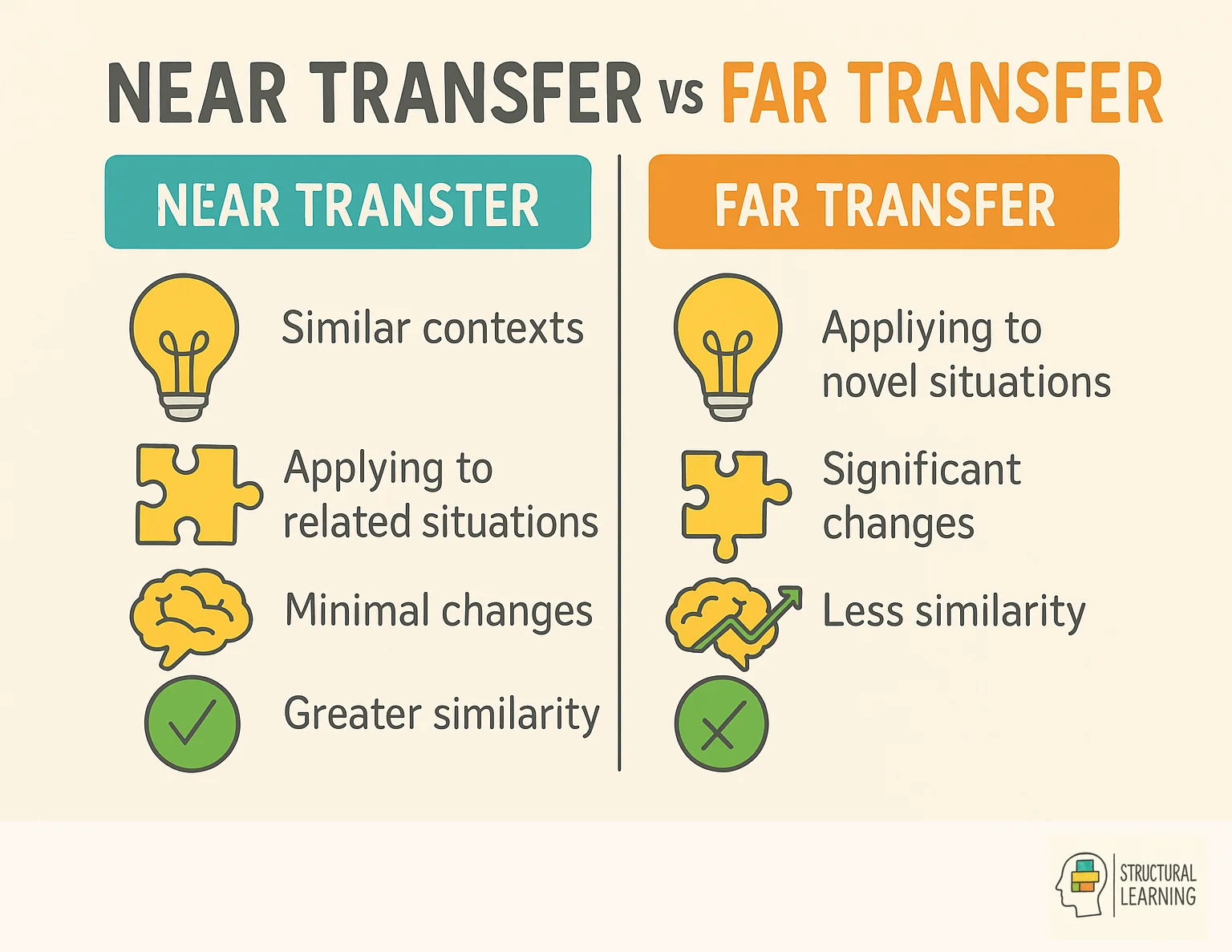

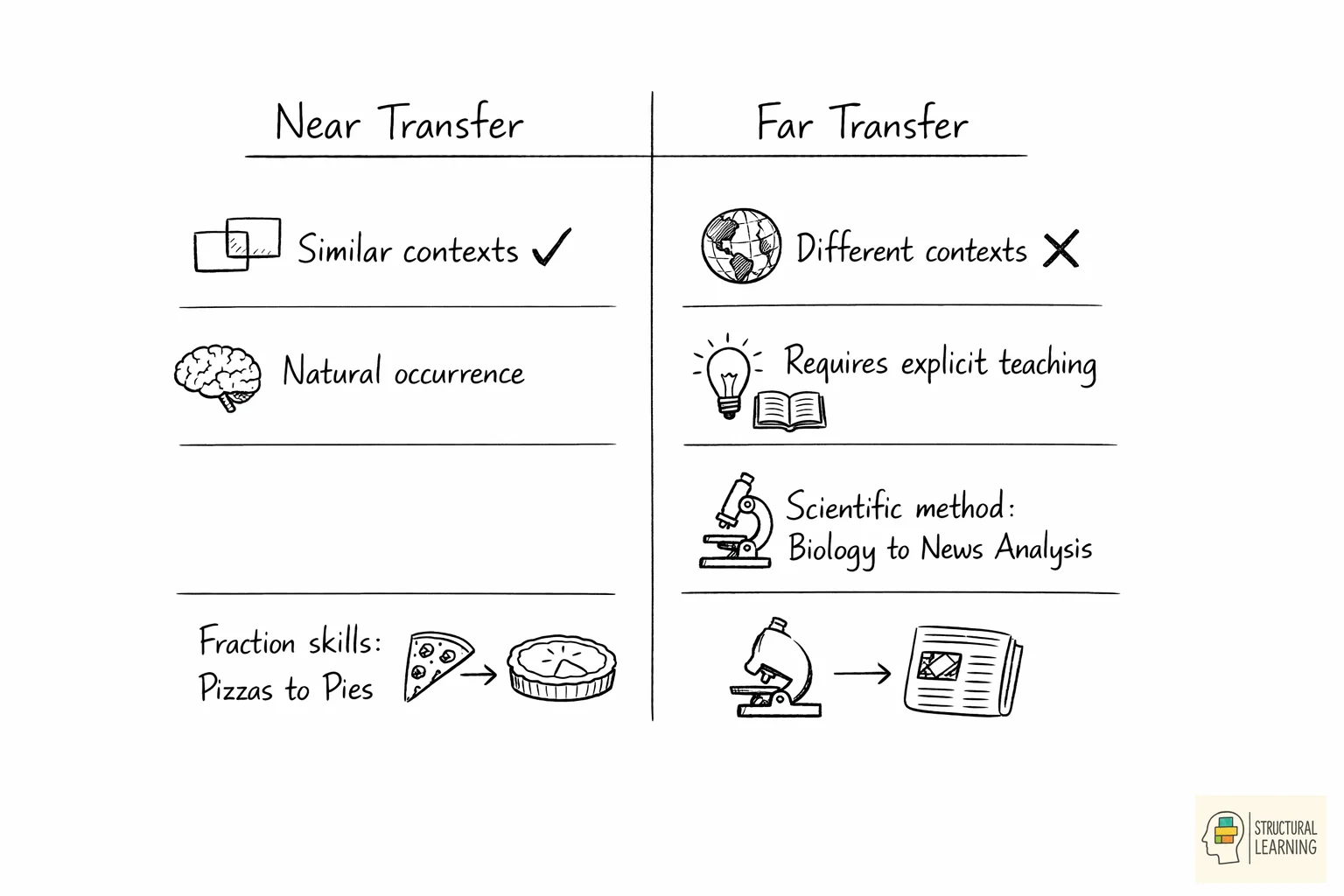

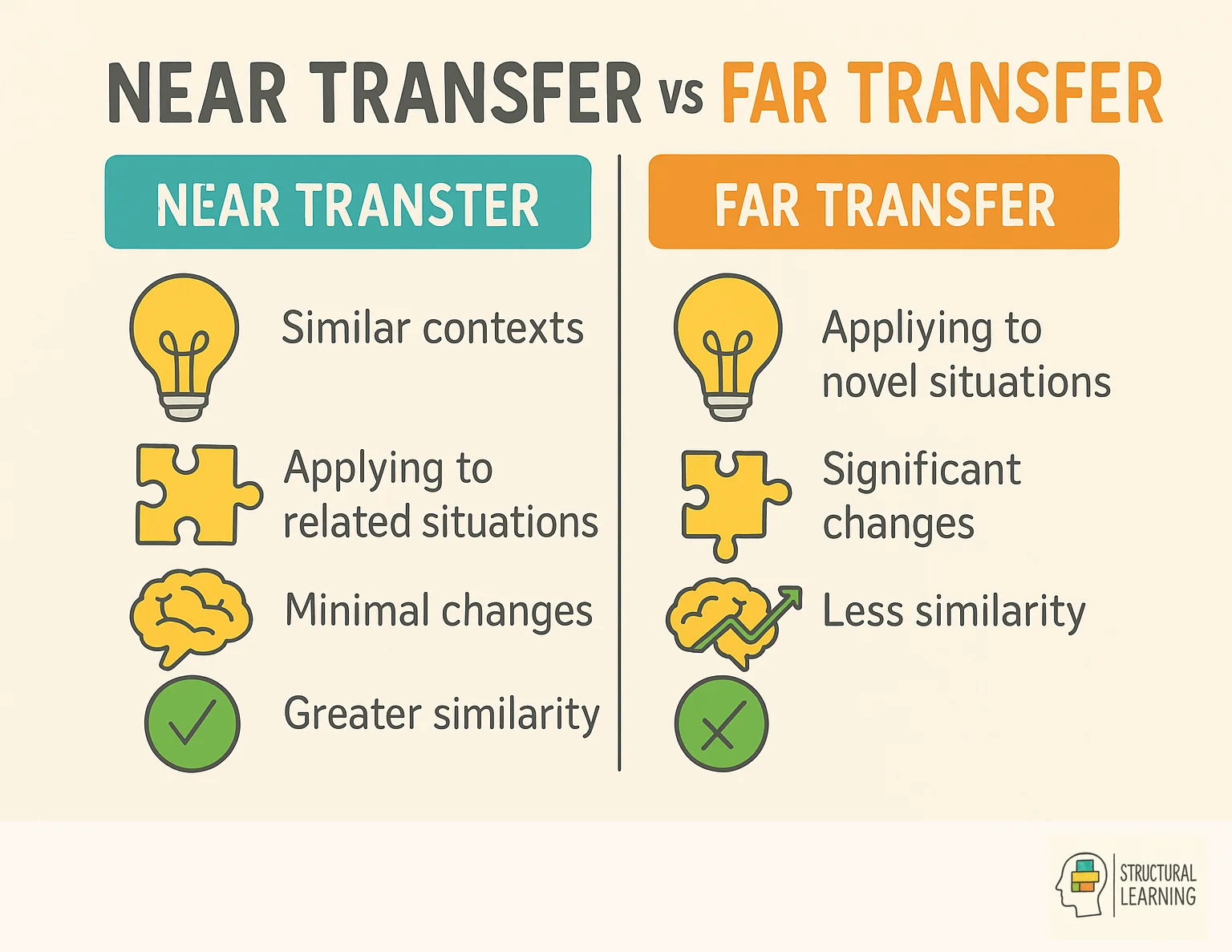

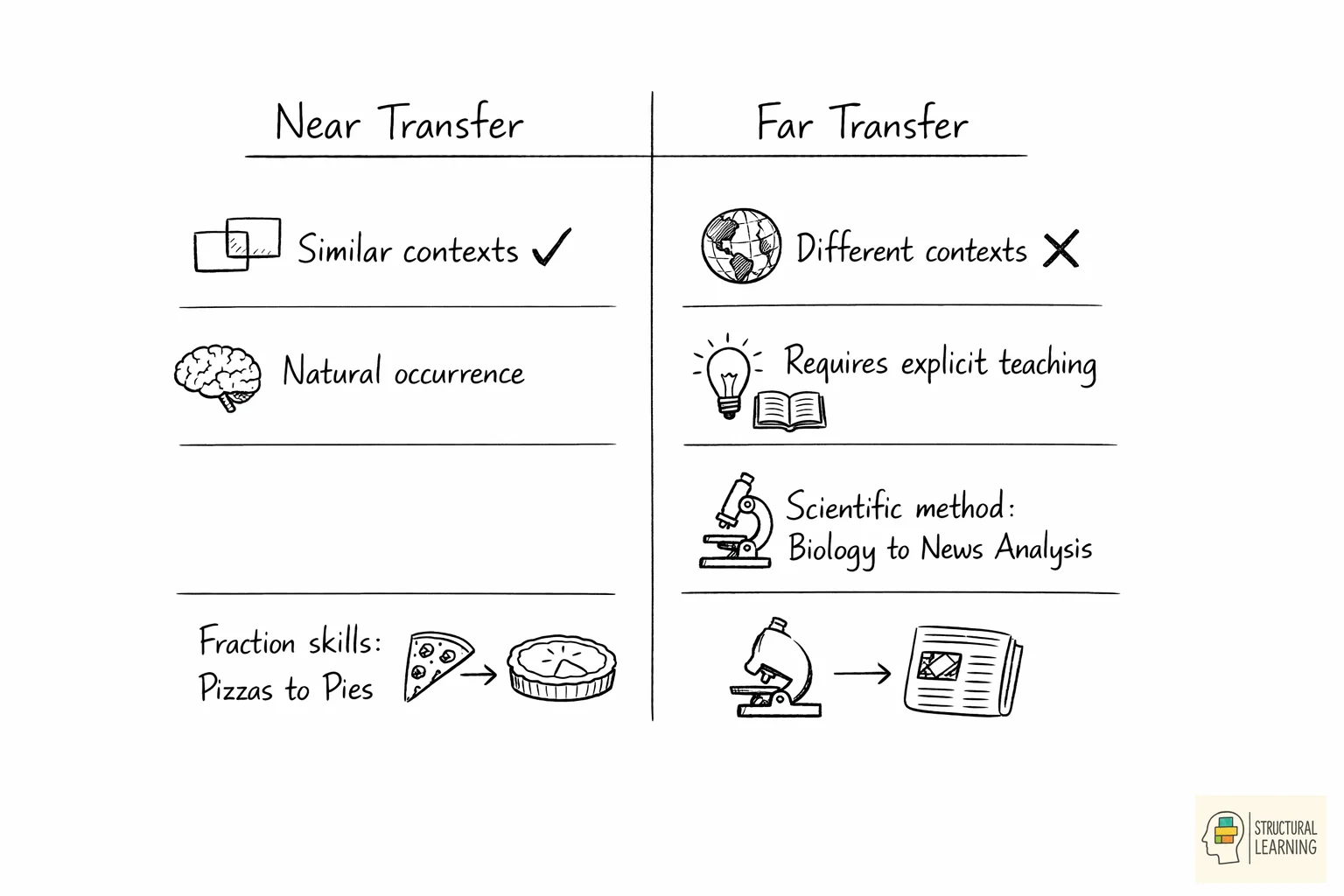

Near transfer occurs when students apply learning to situations that are similar to the original context, such as using fraction skills learned with pizzas to solve problems about pies. Far transfer happens when students apply knowledge to very different contexts, like using scientific method principles learned in biology to evaluate claims in a news article. Near transfer happens more naturally, while far transfer requires explicit teaching of connections and abstract principles.

| Transfer Type | Description | Example | Teaching Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Near transfer | Similar contexts | Fractions to decimals | Highlight similarities |

| Far transfer | Different contexts | Chess to strategic planning | Explicit bridging |

| Positive transfer | Prior learning helps | Spanish helps Italian | Build on foundations |

| Negative transfer | Prior learning hinders | Driving abroad | Address interference |

| Vertical transfer | Basic to complex | Addition to multiplication | Scaffold progression |

The distinction between near and far transfer proves essential for understanding why some applications of learning seem effortless while others prove frustratingly elusive.

Near transfer occurs when the original learning context and the new application context share obvious similarities. When students practise solving two-digit addition problems and then successfully solve three-digit addition problems, they're demonstrating near transfer. The surface features remain similar; the underlying procedures map directly onto one another. A student who learns to drive an automatic car in one model can typically transfer those skills to another automatic vehicle with little difficulty.

Far transfer, by contrast, involves applying learning to contexts that appear quite different on the surface. Using strategic thinking developed through chess to inform business decision-making would constitute far transfer. Applying mathematical concepts from the classroom to analyse real-world economic data requires far transfer. The connections aren't obvious, and the contextual features differ substantially.

Research consistently shows that near transfer happens more readily than far transfer. This finding has profound implications for education. If we want students to apply classroom learning to genuinely novel situations, we cannot simply hope transfer will occur spontaneously. We must design instruction specifically to promote it.

Several interconnected factors explain why students frequently struggle to apply what they've learned to new contexts.

When students learn information in a particular setting, that knowledge often becomes tied to the specific cues, examples, and contexts present during learning. A concept introduced using only textbook problems may remain mentally linked to those exact problem formats. When students encounter the same concept in a different guise, they fail to recognise it.

This phenomenon relates closely to what psychologists call encoding specificity. The conditions present during learning become part of the memory trace itself. Without deliberate variation during instruction, knowledge remains encapsulated within its original learning context.

Students sometimes acquire knowledge at a surface level, memorising facts, procedures, or formulas without developing genuine conceptual understanding. They can reproduce information when tested directly but cannot flexibly apply that knowledge because they never truly understood the underlying principles.

Deep understanding involves grasping what something is and why it works, when it applies, and how it relates to other concepts. Without this depth, students possess knowledge they cannot deploy adaptively. This connects directly to the importance of developing student metacognition, as learners need to understand their own knowledge structures.

Even when students possess transferable knowledge, they may not retrieve it at the appropriate moment. The new situation doesn't activate the relevant prior learning because the surface features differ too much from the original learning context.

This retrieval failure explains why students sometimes claim they "never learned" something they actually studied extensively. The knowledge exists in memory, but the current context doesn't trigger its retrieval. Retrieval practise across varied contexts can help address this problem.

Thorndike's original theory proposed that transfer depends on the degree to which two situations share identical elements. The more overlap in specific skills, knowledge, or procedures, the more transfer should occur. This explains near transfer well but offers limited guidance for promoting far transfer.

Building on earlier work, generalization theory suggests that transfer depends on learners abstracting general principles from specific instances. When students extract underlying rules, patterns, or schemas, they can apply these abstractions to new situations even when surface features differ.

This perspective emphasises the importance of helping students see past surface features to identify deeper structural similarities. Schema building becomes central to transfer.

Perkins and Salomon's influential framework distinguishes two mechanisms through which transfer operates:

Low road transfer occurs automatically and without conscious effort. It depends on extensive, varied practise that builds strong stimulus-response patterns. When these patterns become sufficiently well-practised and automatic, similar stimuli in new situations trigger the learned responses spontaneously. This mechanism primarily supports near transfer.

High road transfer involves deliberate, mindful abstraction. Learners consciously identify principles or strategies in one context and actively search for applications in new contexts. This mechanism can support far transfer but requires explicit instructionand practise in the processes of abstraction and connection-making.

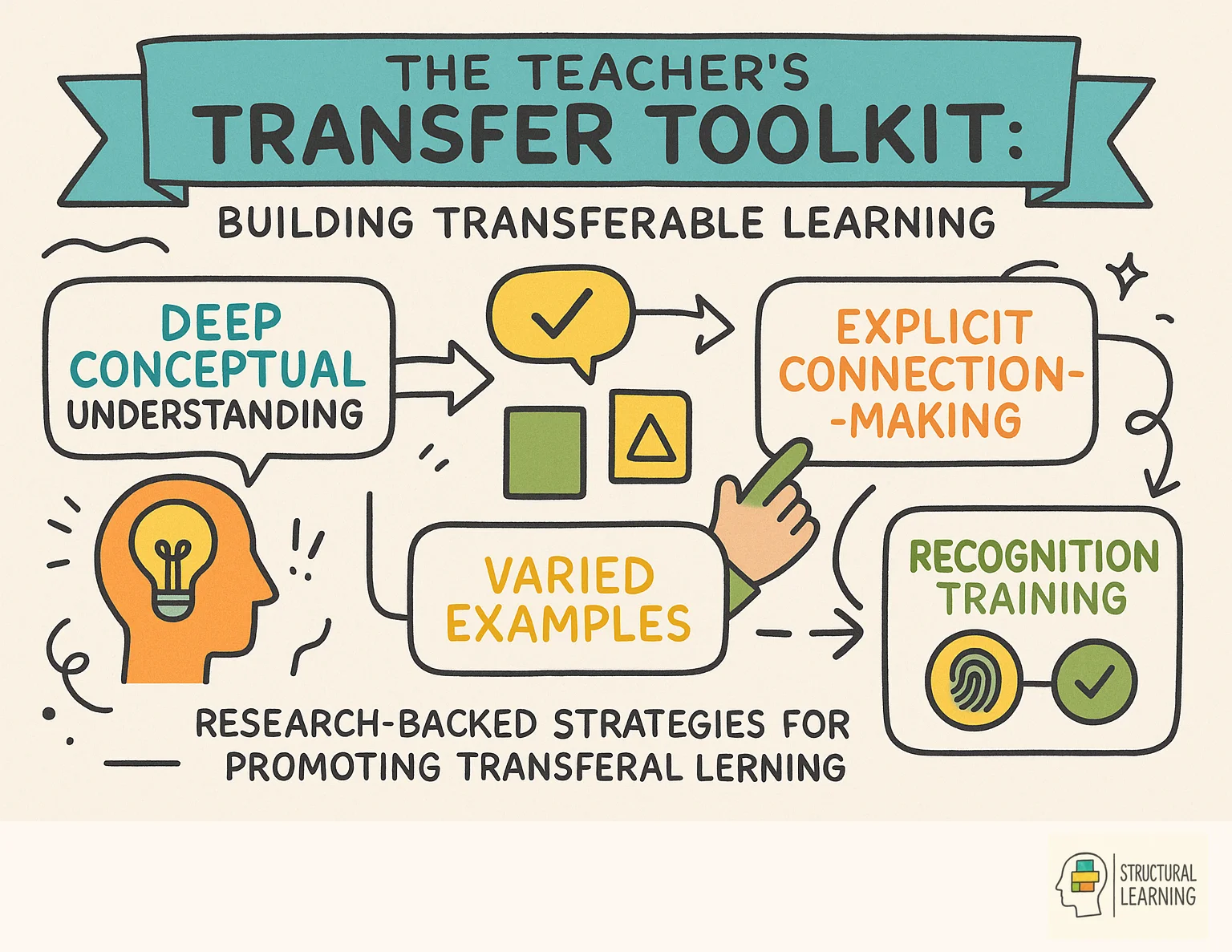

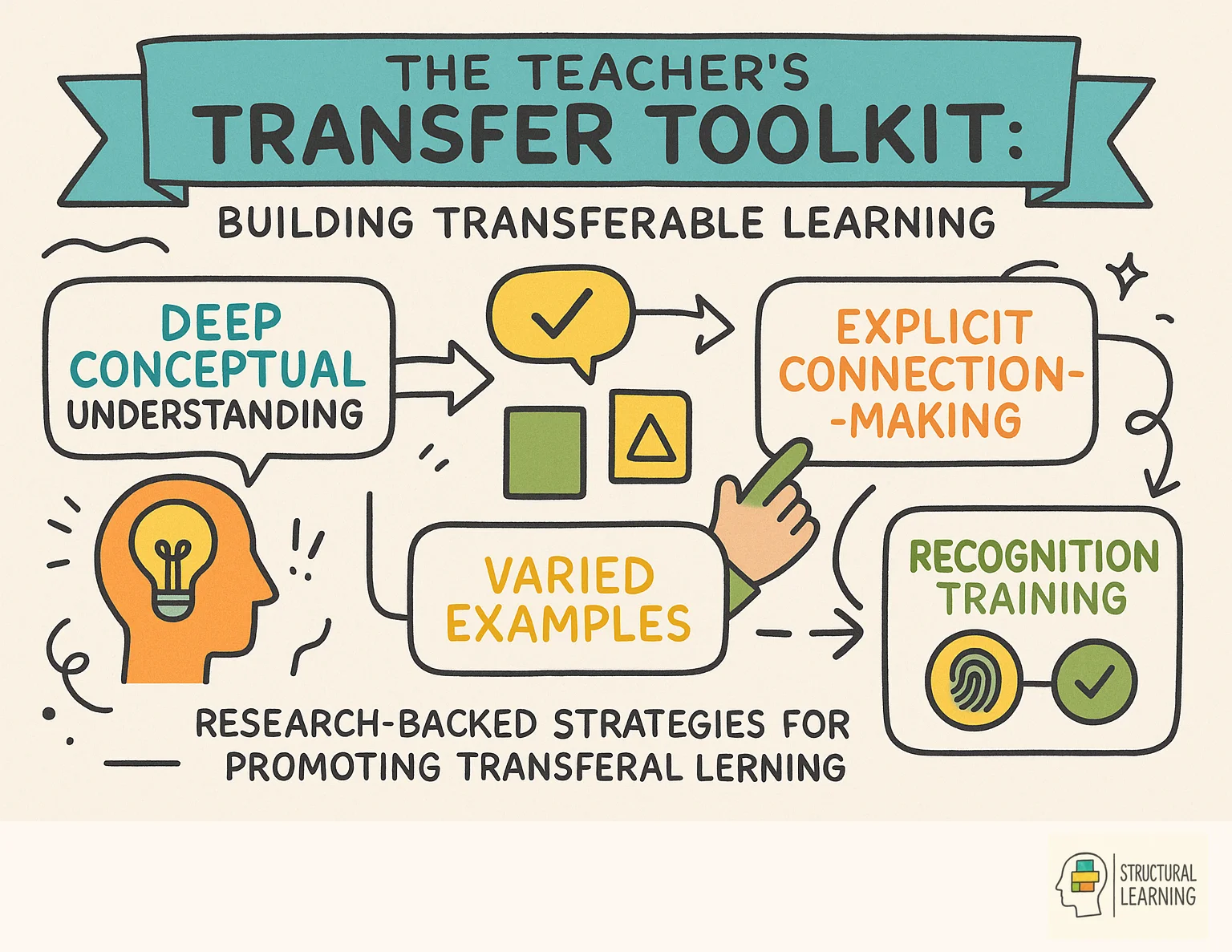

Surface-level learning rarely transfers. To promote transfer, instruction must help students develop genuine conceptual understanding. This means moving beyond memorisation of facts and procedures to explore underlying principles, relationships, and reasoning.

Ask students to explain why, not just what. Use questioning strategies that push beyond recall to analysis and application. Encourage students to articulate the reasoning behind procedures rather than simply executing steps mechanically.

Research consistently demonstrates that learning from multiple examples promotes transfer more effectively than learning from a single example. Importantly, these examples should vary in surface features while maintaining common underlying structure.

When introducing a concept, present it through diverse instances that help students distinguish essential features from incidental ones. If all your examples of persuasive writing come from political contexts, students may unconsciously conclude that persuasion only applies in politics. Varied examples help learners abstract the transferable principle.

Don't assume students will spontaneously recognise when previously learned knowledge applies. Explicitly point out connections between current learning and prior knowledge. Show how concepts from one subject area apply in another.

Teachers can model the thought process of recognising transfer opportunities. When introducing new content, explicitly activate relevant prior knowledge by asking "What do you already know that might help here?" or "Where have we seen something similar before?" This supports metacognitive development.

The context in which students practise retrieving knowledge matters enormously for transfer. If all practise occurs in identical conditions, knowledge becomes bound to those conditions. Varying the contexts in which students practise promotes more flexible, transferable learning.

Design homework, classwork, and assessments that present familiar concepts in unfamiliar formats or applications. Mix problem types rather than blocking practise by topic. These interleaving strategies may feel more difficult but produce more transferable learning.

Abstract principles transfer more readily than context-specific procedures. Teaching students the abstract principle alongside concrete applications helps them recognise where that principle applies across contexts.

For example, rather than teaching specific negotiation techniques, teach the underlying principle that successful negotiations require understanding the other party's interests. Then show how this principle applies across diverse negotiation contexts.

Students who understand the transfer problem and actively seek transfer opportunities demonstrate better transfer than students who passively wait for knowledge to become relevant. Teaching students about transfer itself can improve their transfer performance.

Explicitly discuss the challenge of applying learning to new situations. Help students develop habits of mind that include asking "Where else might this apply?" Encourage reflection on when and how to use various strategies and approaches.

Transfer between subjects happens most effectively when teachers explicitly highlight connections and shared principles, such as showing how proportional reasoning in math applies to scale drawings in geography. Research shows that transfer across domains rarely happens spontaneously; students need guidance to recognise that skills from one subject apply elsewhere. Successful cross-curricular transfer requires coordination between teachers and deliberate attention to underlying concepts that span disciplines.

Different subject areas offer different opportunities and challenges for transfer.

Mathematical concepts and procedures are designed to be abstract and general, theoretically making them highly transferable. In practise, however, students often struggle to apply mathematical knowledge outside maths class.

To promote transfer from mathematics, connect mathematical procedures to meaningful contexts. Show how the same mathematical structures appear in different real-world situations. Practise applying mathematical reasoning to problems from science, economics, and everyday life. Concrete-pictorial-abstract approaches can help bridge this gap.

Reading comprehension strategieslike summarising, questioning, and making inferences can transfer across text types and subject areas. However, this transfer requires explicit attention to comprehension as a set of general strategies rather than content-specific skills.

Teach reading comprehension strategies as transferable tools. Practise applying the same strategies across different text types and subjects. Make explicit that the summarising strategy used in English also applies when reading science textbooks or historical documents.

Writing skills have strong transfer potential, as the basic elements of effective communication apply across contexts. However, each genre and discipline has specific conventions that require additional learning.

Teach general principles of effective writing, such as audience awareness, clear organisation, and evidence-based arguments, while also addressing genre-specific requirements. Help students recognise what transfers across writing contexts and what requires adaptation.

Scientific reasoning skills, including hypothesis generation, experimental design, and evidence evaluation, can potentially transfer to everyday reasoning and decision-making. Achieving this transfer requires explicitly connecting scientific thinking to real-world applications.

Show students how scientific reasoning applies to evaluating claims in media, making personal decisions, and understanding current events. Practise applying scientific thinking to non-laboratory contexts.

Teachers can assess transfer by presenting problems in new contexts that require the same underlying principles but have different surface features from practise examples. Effective AI-powered assessment includes asking students to explain their reasoning, solve problems with novel elements, or apply concepts to real-world scenarios they haven't encountered before. The key is ensuring assessment tasks genuinely require transfer rather than simple recall or repetition of practiced procedures.

Traditional assessments often fail to measure transfer because they present familiar content in familiar formats. If we value transfer as an educational outcome, our assessments must deliberately include transfer tasks.

Include assessment items that present familiar concepts in unfamiliar contexts or formats. Ask students to apply learning to novel problems they haven't encountered during instruction. These assessments reveal whether students can actually use their knowledge flexibly.

Performance assessments that require students to complete authentic tasks often provide better evidence of transfer than traditional tests. When students must apply knowledge to solve genuine problems, produce real products, or demonstrate skills in context, they reveal their capacity for transfer.

Ask students not just to demonstrate skills but to explain when and why to use them. Can they identify contexts where particular strategies or concepts apply? Can they articulate the reasoning behind procedures? These responses reveal depth of understanding that predicts transfer.

One persistent misconception holds that teaching general skills, like structural-learning.com/post/what-is-critical-thinking">critical thinking or problem-solving, will automatically enhance performance across all domains. Research suggests this view is overly optimistic. While some general strategies exist, expertise is largely domain-specific.

This doesn't mean we should abandon teaching thinking skills, but we should recognise that critical thinking in one domain doesn't automatically transfer to another. Students need opportunities to practise thinking skills across multiple domains.

Another misconception suggests that sufficient practise with content will automatically produce transfer. While practise is necessary, the type of practise matters enormously. Practising the same problems repeatedly in identical formats builds automaticity but not flexibility.

Some assume that if students truly understand something, they will automatically transfer that understanding. While deep understanding facilitates transfer, it doesn't guarantee it. Students may understand a concept thoroughly yet fail to recognise its relevance in new situations.

Practical applications include using bridging analogies (connecting familiar situations to new ones), creating comparison charts that highlight how the same principle appears across contexts, and regularly asking 'Where else might this apply?' after teaching concepts. Teachers can implement 'hugging' strategies (making practise similar to application contexts) and 'bridging' strategies (explicitly teaching abstract principles). Simple techniques like varying practise problems' surface features while keeping underlying structures constant help students focus on transferable elements.

For teachers seeking to enhance transfer in their classrooms, several practical strategies emerge from the research.

Create opportunities for students to encounter the same concepts across different contexts throughout the year. Rather than teaching topics in isolation, help students see connections across units and subjects. Use graphic organisers to make these connections visible.

Design homework that asks students to find applications of classroom learning in their lives. Encourage students to identify where concepts from class show up outside school. Discuss these applications together.

Collaborate with colleagues in other subjects to coordinate instruction. When students see the same concepts appearing across classes, perhaps introduced with slightly different terminology or emphasis, they begin to recognise the transferable nature of knowledge.

Use analogies and comparisons regularly. Explicitly comparing new concepts to familiar ones helps students abstract underlying structures. Ask students to generate their own analogies as a way of developing transfer-ready understanding.

Revisit concepts throughout the year rather than teaching them once and moving on. Each revisit offers an opportunity to encounter the concept in a new context, building the varied experience that promotes transfer.

Essential readings include Perkins and Salomon's 'Teaching for Transfer' (1992) which outlines high-road and low-road transfer mechanisms, and Bransford and Schwartz's 'Rethinking Transfer' (1999) which introduced the preparation for future learning perspective. Modern reviews like Barnett and Ceci's transfer taxonomy (2002) provide frameworks for understanding when transfer is likely to occur. These foundational papers offer practical insights alongside theoretical frameworks that can inform classroom practise.

Research on transfer spans over a century and includes some foundational works that continue to inform educational practise. These papers offer deeper insight into the mechanisms and challenges of transfer.

This seminal paper established the distinction between low road and high road transfer that continues to guide educational research. Perkins and Salomon explain why conventional instruction often fails to produce transfer and outline principles for designing instruction that promotes more flexible learning. Their framework offers practical guidance for teachers seeking to help students apply knowledge beyond its original context.

This paper provides a systematic framework for describing transfer situations along multiple dimensions, including content, context, temporal distance, functional context, and modality. By creating this taxonomy, Barnett and Ceci helped researchers and educators think more precisely about what transfer involves and why it sometimes succeeds and sometimes fails.

Bransford and Schwartz challenge narrow conceptions of transfer focused solely on initial learning. They introduce the concept of "preparation for future learning," suggesting that prior learning should be evaluated by how well it prepares students to learn new things, not just whether it transfers directly. This broader view has significant implications for curriculum design.

This research demonstrates that retrieval practise with varied examples enhances transfer more than retrieval with identical examples. The findings connect the testing effectliterature with transfer research, showing how practise testing can be designed to promote more flexible, transferable learning.

This comprehensive report synthesises research on learning and includes substantial discussion of transfer. It emphasises that transfer requires depth of understanding, organised knowledge structures, and metacognitive awareness. The report offers research-based principles for designing instruction that promotes transfer and remains highly influential in educational policy and practise.

Note: The landmark "How People Learn" (2000) was updated in 2018 with "How People Learn II: Learners, Contexts, and Cultures" (National Academies Press), incorporating additional research on cultural and contextual factors in learning transfer.

---

Transfer of learning occurs when students successfully apply knowledge, skills, or strategies learned in one context to solve problems or complete tasks in new situations. Think of it as the bridge between classroom learning and real-world application; when a student uses fraction concepts from maths to accurately measure ingredients in food technology, they're demonstrating transfer.

At its core, transfer involves recognising patterns and connections between what students already know and what they're encountering for the first time. This process requires more than simple recall; it demands that learners identify relevant similarities between contexts and adapt their knowledge accordingly. For instance, when Year 8 students apply their understanding of persuasive writing techniques from English lessons to create compelling science fair presentations, they're engaging in meaningful transfer.

The strength of transfer depends on several key factors. First, the depth of initial learning matters significantly; surface-level memorisation rarely transfers well. Second, the similarity between learning and application contexts affects success rates. Students more readily transfer multiplication skills to division problems than to interpreting statistical graphs, for example. Third, explicit instruction in recognising connections enhances transfer. When teachers deliberately highlight how graphing skills in maths relate to data analysis in geography, students become better at spotting these links independently.

Understanding transfer helps explain why some learning experiences create lasting impact whilst others fade quickly. When students learn the water cycle through memorising definitions, they might struggle to explain local flooding. However, when they explore the concept through experiments, diagrams, and connections to weather patterns, they develop transferable understanding that applies to new environmental contexts.

Near transfer and far transfer represent two distinct ways students apply their learning, each requiring different teaching approaches. Near transfer occurs when students apply knowledge to situations closely resembling the original learning context. For instance, when a pupil who has learnt to solve equations with one variable successfully tackles similar equations with different numbers, they're demonstrating near transfer. The contexts share surface features, making the connection obvious.

Far transfer, by contrast, happens when students apply learning to seemingly unrelated situations. When a student uses their understanding of scientific method from biology lessons to evaluate claims in a newspaper article, they're engaging in far transfer. The connection between contexts is conceptual rather than superficial.

Research by Perkins and Salomon (1989) suggests that near transfer often happens automatically, whilst far transfer typically requires explicit instruction and metacognitive awareness. This has profound implications for your classroom practise. To encourage near transfer, provide multiple examples with varied surface features but consistent underlying structures. For example, when teaching fraction addition, use problems involving pizzas, chocolate bars, and measuring cups, but maintain the same procedural steps.

For far transfer, you need to make abstract principles explicit. When teaching persuasive writing, don't just focus on essay structure; discuss how persuasion works across contexts, from advertising to political speeches to scientific arguments. Encourage students to identify these principles themselves through comparison activities. Ask them to find similarities between how they solve maths word problems and how they approach reading comprehension tasks.

The key is recognising that whilst near transfer helps build fluency and confidence, far transfer develops the flexible thinking students need for real-world problem-solving. Both deserve deliberate attention in your teaching practise.

Despite our best efforts, students often struggle to apply what they've learnt in one subject to another, or from classroom to real-world situations. Understanding why transfer fails is the first step towards addressing these challenges in your teaching practise.

The most significant barrier is context dependency. Students frequently treat each subject as an isolated silo, unable to recognise connections between similar concepts. For instance, a pupil who confidently calculates percentages in maths may struggle with the identical skill when analysing data in geography. This happens because knowledge becomes 'welded' to the specific context where it was first learnt, a phenomenon cognitive scientists call the problem of inert knowledge.

Surface-level learning presents another major obstacle. When students memorise facts or procedures without understanding underlying principles, transfer becomes nearly impossible. A Year 7 student might perfectly recite the water cycle for a science test but fail to connect this knowledge when studying weather patterns in geography. Research by Bransford and Schwartz (1999) shows that emphasising memorisation over comprehension severely limits students' ability to adapt their knowledge to new situations.

Time constraints and curriculum pressure compound these issues. Teachers often feel compelled to rush through content, leaving little opportunity to explore connections across topics. Additionally, assessment practices that reward recall rather than application inadvertently discourage transfer. When exams focus on reproducing specific answers rather than demonstrating flexible thinking, students naturally adapt their learning strategies accordingly.

To overcome these barriers, try explicitly highlighting connections between subjects during lessons. For example, when teaching persuasive writing, reference techniques students have encountered in history source analysis. Build in regular opportunities for students to practise applying concepts in varied contexts, and design assessments that require knowledge application rather than mere reproduction.

Near transfer occurs when students apply learning to similar situations (like using fraction skills with pizzas to solve problems about pies), whilst far transfer happens when they apply knowledge to very different contexts (like using scientific method principles from biology to evaluate news articles). Understanding this distinction is crucial because near transfer happens naturally, but far transfer demands an explicit teaching of links and abstraction principles to help students recognise when and how to apply their knowledge.

Transfer often fails because knowledge remains tied to the specific context where it was learnt, students develop only shallow understanding without grasping underlying principles, or they simply don't retrieve relevant knowledge when facing new situations. When students learn using only textbook problems, for example, their knowledge becomes mentally linked to those exact formats and they fail to recognise the same concept in different contexts.

Teaching for transfer involves promoting deep conceptual understanding rather than surface memorisation, using multiple varied examples during instruction, and explicitly helping students recognise when and how to apply what they know. You should also focus on helping students abstract general principles from specific instances and provide retrieval practise across varied contexts to strengthen their ability to access knowledge when needed.

Common examples include students using persuasive writing skills learnt in English lessons to construct arguments in history essays, applying addition facts to understand multiplication concepts, or using strategic thinking from chess to approach problem-solving in mathematics. You might also notice students applying scientific method principles from one subject to evaluate information in completely different contexts, though this far transfer requires more explicit teaching support.

Low road transfer occurs automatically through extensive, varied practise that builds strong patterns, primarily supporting near transfer between similar situations. High road transfer involves deliberate, mindful abstraction where learners consciously identify underlying principles and apply them to new contexts, which is essential for far transfer and calls for an explicit instruction in making connections and the abstract thinking skills.

To prevent knowledge from becoming tied to specific learning contexts, you should deliberately vary the examples, problems, and situations you use during instruction rather than relying on single formats or textbook problems. This approach, combined with explicit discussion of how the same principles apply across different contexts, helps students recognise underlying patterns and connections that enable flexible application of their learning.

These peer-reviewed studies provide the research foundation for the strategies discussed in this article:

Designing Teaching for Transfer in English for Academic Purposes View study ↗

4 citations

Heon Jeon (2022)

This research reveals that multilingual students in academic English courses rarely transfer their writing skills to other contexts without explicit instruction designed for transfer. The study demonstrates that teachers must actively help students develop transfer thinking habits rather than assuming skills will naturally carry over to new situations. For educators working with English language learners, this highlights the critical importance of deliberately connecting classroom learning to real-world academic writing tasks.

Generalizations and analogical reasoning of junior high school viewed from Bruner's learning theory View study ↗

30 citations

Lilis Marina Angraini et al. (2023)

This study examines how middle school students use pattern recognition and comparison skills in mathematics, applying Jerome Bruner's foundational learning theory to understand student reasoning processes. The research shows that students' ability to see connections between mathematical concepts and apply them in new situations varies significantly based on how material is presented. Mathematics teachers can use these insights to structure lessons that better support students in recognising patterns and making meaningful connections between different problem types.

Transfer of Learning and Teaching: A Review of Transfer Theories and Effective Instructional Practices View study ↗

90 citations

Shiva Hajian (2019)

This comprehensive review examines why students often struggle to apply what they've learned in new situations and identifies specific teaching strategies that promote successful knowledge transfer. The research synthesizes decades of learning theory to provide concrete guidance on creating learning conditions that help students flexibly use their knowledge across different contexts. Teachers across all subjects will find practical insights for designing instruction that moves beyond isolated skill practise to meaningful, transferable learning.

Teaching for transfer of second language learning View study ↗

12 citations

M. James (2018)

This research explores how language learning in one context can effectively support performance in different situations, much like how musical skills can transfer between instruments. The study provides evidence-based strategies for second language teachers to help students apply their language skills beyond the classroom to real-world communication needs. Language educators will gain valuable insights into structuring lessons and activities that promote genuine language transfer rather than simply isolated grammar or vocabulary practise.

Students' Analogical Reasoning in Solving Geometry Problems Viewed from Visualizer's and Verbalizer's Cognitive Style View study ↗

2 citations

Ali Shodikin et al. (2023)

This study investigates how high school students with different thinking styles, visual learners versus verbal processors, approach geometry problem-solving through comparison and pattern recognition. The research addresses the widespread challenge of low geometry achievement by examining how students' natural cognitive preferences affect their ability to connect geometric concepts. Mathematics teachers can use these findings to differentiate instruction and provide multiple pathways for students to understand and apply geometric reasoning based on their individual learning strengths.

Transfer of learning is the ability to apply knowledge, skills, and strategies acquired in one context to new and different situations. As a teacher, mastering how to creates this skill in your students is crucial for helping them move beyond rote memorisation to genuine understanding they can use throughout their lives. This comprehensive guide provides you with research-backed strategies, practical classroom techniques, and proven methods to transform how your students connect and apply their learning. Discover why some lessons stick whilst others are quickly forgotten, and learn exactly how to design experiences that build truly transferable knowledge.

Key Takeaways

Transfer of learning describes the process by which knowledge, skills, or strategies acquired in one situation influence performance in another. When a student learns to write persuasive essays in English and then successfully applies those argumentation skills in history, transfer has occurred. When a child masters addition facts and uses that knowledge to understand multiplication, transfer is at work.

The concept dates back to Edward Thorndike and Robert Woodworth's research in 1901, which challenged earlier assumptions about mental discipline. Before their work, educators believed that studying rigorous subjects like Latin or geometry would train the mind in ways that transferred broadly to other domains. Thorndike and Woodworth found something more nuanced: transfer depends heavily on the degree to which two situations share common elements. This cognitive load theory perspective suggests that identical elements between learning and application contexts predict how readily transfer will occur.

More contemporary researchers, particularly David Perkins and Gavriel Salomon, have expanded our understanding considerably. They distinguish between what they call "low road" and "high road" transfer mechanisms, each operating through different cognitive pathways.

Near transfer occurs when students apply learning to situations that are similar to the original context, such as using fraction skills learned with pizzas to solve problems about pies. Far transfer happens when students apply knowledge to very different contexts, like using scientific method principles learned in biology to evaluate claims in a news article. Near transfer happens more naturally, while far transfer requires explicit teaching of connections and abstract principles.

| Transfer Type | Description | Example | Teaching Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Near transfer | Similar contexts | Fractions to decimals | Highlight similarities |

| Far transfer | Different contexts | Chess to strategic planning | Explicit bridging |

| Positive transfer | Prior learning helps | Spanish helps Italian | Build on foundations |

| Negative transfer | Prior learning hinders | Driving abroad | Address interference |

| Vertical transfer | Basic to complex | Addition to multiplication | Scaffold progression |

The distinction between near and far transfer proves essential for understanding why some applications of learning seem effortless while others prove frustratingly elusive.

Near transfer occurs when the original learning context and the new application context share obvious similarities. When students practise solving two-digit addition problems and then successfully solve three-digit addition problems, they're demonstrating near transfer. The surface features remain similar; the underlying procedures map directly onto one another. A student who learns to drive an automatic car in one model can typically transfer those skills to another automatic vehicle with little difficulty.

Far transfer, by contrast, involves applying learning to contexts that appear quite different on the surface. Using strategic thinking developed through chess to inform business decision-making would constitute far transfer. Applying mathematical concepts from the classroom to analyse real-world economic data requires far transfer. The connections aren't obvious, and the contextual features differ substantially.

Research consistently shows that near transfer happens more readily than far transfer. This finding has profound implications for education. If we want students to apply classroom learning to genuinely novel situations, we cannot simply hope transfer will occur spontaneously. We must design instruction specifically to promote it.

Several interconnected factors explain why students frequently struggle to apply what they've learned to new contexts.

When students learn information in a particular setting, that knowledge often becomes tied to the specific cues, examples, and contexts present during learning. A concept introduced using only textbook problems may remain mentally linked to those exact problem formats. When students encounter the same concept in a different guise, they fail to recognise it.

This phenomenon relates closely to what psychologists call encoding specificity. The conditions present during learning become part of the memory trace itself. Without deliberate variation during instruction, knowledge remains encapsulated within its original learning context.

Students sometimes acquire knowledge at a surface level, memorising facts, procedures, or formulas without developing genuine conceptual understanding. They can reproduce information when tested directly but cannot flexibly apply that knowledge because they never truly understood the underlying principles.

Deep understanding involves grasping what something is and why it works, when it applies, and how it relates to other concepts. Without this depth, students possess knowledge they cannot deploy adaptively. This connects directly to the importance of developing student metacognition, as learners need to understand their own knowledge structures.

Even when students possess transferable knowledge, they may not retrieve it at the appropriate moment. The new situation doesn't activate the relevant prior learning because the surface features differ too much from the original learning context.

This retrieval failure explains why students sometimes claim they "never learned" something they actually studied extensively. The knowledge exists in memory, but the current context doesn't trigger its retrieval. Retrieval practise across varied contexts can help address this problem.

Thorndike's original theory proposed that transfer depends on the degree to which two situations share identical elements. The more overlap in specific skills, knowledge, or procedures, the more transfer should occur. This explains near transfer well but offers limited guidance for promoting far transfer.

Building on earlier work, generalization theory suggests that transfer depends on learners abstracting general principles from specific instances. When students extract underlying rules, patterns, or schemas, they can apply these abstractions to new situations even when surface features differ.

This perspective emphasises the importance of helping students see past surface features to identify deeper structural similarities. Schema building becomes central to transfer.

Perkins and Salomon's influential framework distinguishes two mechanisms through which transfer operates:

Low road transfer occurs automatically and without conscious effort. It depends on extensive, varied practise that builds strong stimulus-response patterns. When these patterns become sufficiently well-practised and automatic, similar stimuli in new situations trigger the learned responses spontaneously. This mechanism primarily supports near transfer.

High road transfer involves deliberate, mindful abstraction. Learners consciously identify principles or strategies in one context and actively search for applications in new contexts. This mechanism can support far transfer but requires explicit instructionand practise in the processes of abstraction and connection-making.

Surface-level learning rarely transfers. To promote transfer, instruction must help students develop genuine conceptual understanding. This means moving beyond memorisation of facts and procedures to explore underlying principles, relationships, and reasoning.

Ask students to explain why, not just what. Use questioning strategies that push beyond recall to analysis and application. Encourage students to articulate the reasoning behind procedures rather than simply executing steps mechanically.

Research consistently demonstrates that learning from multiple examples promotes transfer more effectively than learning from a single example. Importantly, these examples should vary in surface features while maintaining common underlying structure.

When introducing a concept, present it through diverse instances that help students distinguish essential features from incidental ones. If all your examples of persuasive writing come from political contexts, students may unconsciously conclude that persuasion only applies in politics. Varied examples help learners abstract the transferable principle.

Don't assume students will spontaneously recognise when previously learned knowledge applies. Explicitly point out connections between current learning and prior knowledge. Show how concepts from one subject area apply in another.

Teachers can model the thought process of recognising transfer opportunities. When introducing new content, explicitly activate relevant prior knowledge by asking "What do you already know that might help here?" or "Where have we seen something similar before?" This supports metacognitive development.

The context in which students practise retrieving knowledge matters enormously for transfer. If all practise occurs in identical conditions, knowledge becomes bound to those conditions. Varying the contexts in which students practise promotes more flexible, transferable learning.

Design homework, classwork, and assessments that present familiar concepts in unfamiliar formats or applications. Mix problem types rather than blocking practise by topic. These interleaving strategies may feel more difficult but produce more transferable learning.

Abstract principles transfer more readily than context-specific procedures. Teaching students the abstract principle alongside concrete applications helps them recognise where that principle applies across contexts.

For example, rather than teaching specific negotiation techniques, teach the underlying principle that successful negotiations require understanding the other party's interests. Then show how this principle applies across diverse negotiation contexts.

Students who understand the transfer problem and actively seek transfer opportunities demonstrate better transfer than students who passively wait for knowledge to become relevant. Teaching students about transfer itself can improve their transfer performance.

Explicitly discuss the challenge of applying learning to new situations. Help students develop habits of mind that include asking "Where else might this apply?" Encourage reflection on when and how to use various strategies and approaches.

Transfer between subjects happens most effectively when teachers explicitly highlight connections and shared principles, such as showing how proportional reasoning in math applies to scale drawings in geography. Research shows that transfer across domains rarely happens spontaneously; students need guidance to recognise that skills from one subject apply elsewhere. Successful cross-curricular transfer requires coordination between teachers and deliberate attention to underlying concepts that span disciplines.

Different subject areas offer different opportunities and challenges for transfer.

Mathematical concepts and procedures are designed to be abstract and general, theoretically making them highly transferable. In practise, however, students often struggle to apply mathematical knowledge outside maths class.

To promote transfer from mathematics, connect mathematical procedures to meaningful contexts. Show how the same mathematical structures appear in different real-world situations. Practise applying mathematical reasoning to problems from science, economics, and everyday life. Concrete-pictorial-abstract approaches can help bridge this gap.

Reading comprehension strategieslike summarising, questioning, and making inferences can transfer across text types and subject areas. However, this transfer requires explicit attention to comprehension as a set of general strategies rather than content-specific skills.

Teach reading comprehension strategies as transferable tools. Practise applying the same strategies across different text types and subjects. Make explicit that the summarising strategy used in English also applies when reading science textbooks or historical documents.

Writing skills have strong transfer potential, as the basic elements of effective communication apply across contexts. However, each genre and discipline has specific conventions that require additional learning.

Teach general principles of effective writing, such as audience awareness, clear organisation, and evidence-based arguments, while also addressing genre-specific requirements. Help students recognise what transfers across writing contexts and what requires adaptation.

Scientific reasoning skills, including hypothesis generation, experimental design, and evidence evaluation, can potentially transfer to everyday reasoning and decision-making. Achieving this transfer requires explicitly connecting scientific thinking to real-world applications.

Show students how scientific reasoning applies to evaluating claims in media, making personal decisions, and understanding current events. Practise applying scientific thinking to non-laboratory contexts.

Teachers can assess transfer by presenting problems in new contexts that require the same underlying principles but have different surface features from practise examples. Effective AI-powered assessment includes asking students to explain their reasoning, solve problems with novel elements, or apply concepts to real-world scenarios they haven't encountered before. The key is ensuring assessment tasks genuinely require transfer rather than simple recall or repetition of practiced procedures.

Traditional assessments often fail to measure transfer because they present familiar content in familiar formats. If we value transfer as an educational outcome, our assessments must deliberately include transfer tasks.

Include assessment items that present familiar concepts in unfamiliar contexts or formats. Ask students to apply learning to novel problems they haven't encountered during instruction. These assessments reveal whether students can actually use their knowledge flexibly.

Performance assessments that require students to complete authentic tasks often provide better evidence of transfer than traditional tests. When students must apply knowledge to solve genuine problems, produce real products, or demonstrate skills in context, they reveal their capacity for transfer.

Ask students not just to demonstrate skills but to explain when and why to use them. Can they identify contexts where particular strategies or concepts apply? Can they articulate the reasoning behind procedures? These responses reveal depth of understanding that predicts transfer.

One persistent misconception holds that teaching general skills, like structural-learning.com/post/what-is-critical-thinking">critical thinking or problem-solving, will automatically enhance performance across all domains. Research suggests this view is overly optimistic. While some general strategies exist, expertise is largely domain-specific.

This doesn't mean we should abandon teaching thinking skills, but we should recognise that critical thinking in one domain doesn't automatically transfer to another. Students need opportunities to practise thinking skills across multiple domains.

Another misconception suggests that sufficient practise with content will automatically produce transfer. While practise is necessary, the type of practise matters enormously. Practising the same problems repeatedly in identical formats builds automaticity but not flexibility.

Some assume that if students truly understand something, they will automatically transfer that understanding. While deep understanding facilitates transfer, it doesn't guarantee it. Students may understand a concept thoroughly yet fail to recognise its relevance in new situations.

Practical applications include using bridging analogies (connecting familiar situations to new ones), creating comparison charts that highlight how the same principle appears across contexts, and regularly asking 'Where else might this apply?' after teaching concepts. Teachers can implement 'hugging' strategies (making practise similar to application contexts) and 'bridging' strategies (explicitly teaching abstract principles). Simple techniques like varying practise problems' surface features while keeping underlying structures constant help students focus on transferable elements.

For teachers seeking to enhance transfer in their classrooms, several practical strategies emerge from the research.

Create opportunities for students to encounter the same concepts across different contexts throughout the year. Rather than teaching topics in isolation, help students see connections across units and subjects. Use graphic organisers to make these connections visible.

Design homework that asks students to find applications of classroom learning in their lives. Encourage students to identify where concepts from class show up outside school. Discuss these applications together.

Collaborate with colleagues in other subjects to coordinate instruction. When students see the same concepts appearing across classes, perhaps introduced with slightly different terminology or emphasis, they begin to recognise the transferable nature of knowledge.

Use analogies and comparisons regularly. Explicitly comparing new concepts to familiar ones helps students abstract underlying structures. Ask students to generate their own analogies as a way of developing transfer-ready understanding.

Revisit concepts throughout the year rather than teaching them once and moving on. Each revisit offers an opportunity to encounter the concept in a new context, building the varied experience that promotes transfer.

Essential readings include Perkins and Salomon's 'Teaching for Transfer' (1992) which outlines high-road and low-road transfer mechanisms, and Bransford and Schwartz's 'Rethinking Transfer' (1999) which introduced the preparation for future learning perspective. Modern reviews like Barnett and Ceci's transfer taxonomy (2002) provide frameworks for understanding when transfer is likely to occur. These foundational papers offer practical insights alongside theoretical frameworks that can inform classroom practise.

Research on transfer spans over a century and includes some foundational works that continue to inform educational practise. These papers offer deeper insight into the mechanisms and challenges of transfer.

This seminal paper established the distinction between low road and high road transfer that continues to guide educational research. Perkins and Salomon explain why conventional instruction often fails to produce transfer and outline principles for designing instruction that promotes more flexible learning. Their framework offers practical guidance for teachers seeking to help students apply knowledge beyond its original context.

This paper provides a systematic framework for describing transfer situations along multiple dimensions, including content, context, temporal distance, functional context, and modality. By creating this taxonomy, Barnett and Ceci helped researchers and educators think more precisely about what transfer involves and why it sometimes succeeds and sometimes fails.

Bransford and Schwartz challenge narrow conceptions of transfer focused solely on initial learning. They introduce the concept of "preparation for future learning," suggesting that prior learning should be evaluated by how well it prepares students to learn new things, not just whether it transfers directly. This broader view has significant implications for curriculum design.

This research demonstrates that retrieval practise with varied examples enhances transfer more than retrieval with identical examples. The findings connect the testing effectliterature with transfer research, showing how practise testing can be designed to promote more flexible, transferable learning.

This comprehensive report synthesises research on learning and includes substantial discussion of transfer. It emphasises that transfer requires depth of understanding, organised knowledge structures, and metacognitive awareness. The report offers research-based principles for designing instruction that promotes transfer and remains highly influential in educational policy and practise.

Note: The landmark "How People Learn" (2000) was updated in 2018 with "How People Learn II: Learners, Contexts, and Cultures" (National Academies Press), incorporating additional research on cultural and contextual factors in learning transfer.

---

Transfer of learning occurs when students successfully apply knowledge, skills, or strategies learned in one context to solve problems or complete tasks in new situations. Think of it as the bridge between classroom learning and real-world application; when a student uses fraction concepts from maths to accurately measure ingredients in food technology, they're demonstrating transfer.

At its core, transfer involves recognising patterns and connections between what students already know and what they're encountering for the first time. This process requires more than simple recall; it demands that learners identify relevant similarities between contexts and adapt their knowledge accordingly. For instance, when Year 8 students apply their understanding of persuasive writing techniques from English lessons to create compelling science fair presentations, they're engaging in meaningful transfer.

The strength of transfer depends on several key factors. First, the depth of initial learning matters significantly; surface-level memorisation rarely transfers well. Second, the similarity between learning and application contexts affects success rates. Students more readily transfer multiplication skills to division problems than to interpreting statistical graphs, for example. Third, explicit instruction in recognising connections enhances transfer. When teachers deliberately highlight how graphing skills in maths relate to data analysis in geography, students become better at spotting these links independently.

Understanding transfer helps explain why some learning experiences create lasting impact whilst others fade quickly. When students learn the water cycle through memorising definitions, they might struggle to explain local flooding. However, when they explore the concept through experiments, diagrams, and connections to weather patterns, they develop transferable understanding that applies to new environmental contexts.

Near transfer and far transfer represent two distinct ways students apply their learning, each requiring different teaching approaches. Near transfer occurs when students apply knowledge to situations closely resembling the original learning context. For instance, when a pupil who has learnt to solve equations with one variable successfully tackles similar equations with different numbers, they're demonstrating near transfer. The contexts share surface features, making the connection obvious.

Far transfer, by contrast, happens when students apply learning to seemingly unrelated situations. When a student uses their understanding of scientific method from biology lessons to evaluate claims in a newspaper article, they're engaging in far transfer. The connection between contexts is conceptual rather than superficial.

Research by Perkins and Salomon (1989) suggests that near transfer often happens automatically, whilst far transfer typically requires explicit instruction and metacognitive awareness. This has profound implications for your classroom practise. To encourage near transfer, provide multiple examples with varied surface features but consistent underlying structures. For example, when teaching fraction addition, use problems involving pizzas, chocolate bars, and measuring cups, but maintain the same procedural steps.

For far transfer, you need to make abstract principles explicit. When teaching persuasive writing, don't just focus on essay structure; discuss how persuasion works across contexts, from advertising to political speeches to scientific arguments. Encourage students to identify these principles themselves through comparison activities. Ask them to find similarities between how they solve maths word problems and how they approach reading comprehension tasks.

The key is recognising that whilst near transfer helps build fluency and confidence, far transfer develops the flexible thinking students need for real-world problem-solving. Both deserve deliberate attention in your teaching practise.

Despite our best efforts, students often struggle to apply what they've learnt in one subject to another, or from classroom to real-world situations. Understanding why transfer fails is the first step towards addressing these challenges in your teaching practise.

The most significant barrier is context dependency. Students frequently treat each subject as an isolated silo, unable to recognise connections between similar concepts. For instance, a pupil who confidently calculates percentages in maths may struggle with the identical skill when analysing data in geography. This happens because knowledge becomes 'welded' to the specific context where it was first learnt, a phenomenon cognitive scientists call the problem of inert knowledge.

Surface-level learning presents another major obstacle. When students memorise facts or procedures without understanding underlying principles, transfer becomes nearly impossible. A Year 7 student might perfectly recite the water cycle for a science test but fail to connect this knowledge when studying weather patterns in geography. Research by Bransford and Schwartz (1999) shows that emphasising memorisation over comprehension severely limits students' ability to adapt their knowledge to new situations.

Time constraints and curriculum pressure compound these issues. Teachers often feel compelled to rush through content, leaving little opportunity to explore connections across topics. Additionally, assessment practices that reward recall rather than application inadvertently discourage transfer. When exams focus on reproducing specific answers rather than demonstrating flexible thinking, students naturally adapt their learning strategies accordingly.

To overcome these barriers, try explicitly highlighting connections between subjects during lessons. For example, when teaching persuasive writing, reference techniques students have encountered in history source analysis. Build in regular opportunities for students to practise applying concepts in varied contexts, and design assessments that require knowledge application rather than mere reproduction.

Near transfer occurs when students apply learning to similar situations (like using fraction skills with pizzas to solve problems about pies), whilst far transfer happens when they apply knowledge to very different contexts (like using scientific method principles from biology to evaluate news articles). Understanding this distinction is crucial because near transfer happens naturally, but far transfer demands an explicit teaching of links and abstraction principles to help students recognise when and how to apply their knowledge.

Transfer often fails because knowledge remains tied to the specific context where it was learnt, students develop only shallow understanding without grasping underlying principles, or they simply don't retrieve relevant knowledge when facing new situations. When students learn using only textbook problems, for example, their knowledge becomes mentally linked to those exact formats and they fail to recognise the same concept in different contexts.

Teaching for transfer involves promoting deep conceptual understanding rather than surface memorisation, using multiple varied examples during instruction, and explicitly helping students recognise when and how to apply what they know. You should also focus on helping students abstract general principles from specific instances and provide retrieval practise across varied contexts to strengthen their ability to access knowledge when needed.

Common examples include students using persuasive writing skills learnt in English lessons to construct arguments in history essays, applying addition facts to understand multiplication concepts, or using strategic thinking from chess to approach problem-solving in mathematics. You might also notice students applying scientific method principles from one subject to evaluate information in completely different contexts, though this far transfer requires more explicit teaching support.

Low road transfer occurs automatically through extensive, varied practise that builds strong patterns, primarily supporting near transfer between similar situations. High road transfer involves deliberate, mindful abstraction where learners consciously identify underlying principles and apply them to new contexts, which is essential for far transfer and calls for an explicit instruction in making connections and the abstract thinking skills.

To prevent knowledge from becoming tied to specific learning contexts, you should deliberately vary the examples, problems, and situations you use during instruction rather than relying on single formats or textbook problems. This approach, combined with explicit discussion of how the same principles apply across different contexts, helps students recognise underlying patterns and connections that enable flexible application of their learning.

These peer-reviewed studies provide the research foundation for the strategies discussed in this article:

Designing Teaching for Transfer in English for Academic Purposes View study ↗

4 citations

Heon Jeon (2022)

This research reveals that multilingual students in academic English courses rarely transfer their writing skills to other contexts without explicit instruction designed for transfer. The study demonstrates that teachers must actively help students develop transfer thinking habits rather than assuming skills will naturally carry over to new situations. For educators working with English language learners, this highlights the critical importance of deliberately connecting classroom learning to real-world academic writing tasks.

Generalizations and analogical reasoning of junior high school viewed from Bruner's learning theory View study ↗

30 citations

Lilis Marina Angraini et al. (2023)

This study examines how middle school students use pattern recognition and comparison skills in mathematics, applying Jerome Bruner's foundational learning theory to understand student reasoning processes. The research shows that students' ability to see connections between mathematical concepts and apply them in new situations varies significantly based on how material is presented. Mathematics teachers can use these insights to structure lessons that better support students in recognising patterns and making meaningful connections between different problem types.

Transfer of Learning and Teaching: A Review of Transfer Theories and Effective Instructional Practices View study ↗

90 citations

Shiva Hajian (2019)

This comprehensive review examines why students often struggle to apply what they've learned in new situations and identifies specific teaching strategies that promote successful knowledge transfer. The research synthesizes decades of learning theory to provide concrete guidance on creating learning conditions that help students flexibly use their knowledge across different contexts. Teachers across all subjects will find practical insights for designing instruction that moves beyond isolated skill practise to meaningful, transferable learning.

Teaching for transfer of second language learning View study ↗

12 citations

M. James (2018)

This research explores how language learning in one context can effectively support performance in different situations, much like how musical skills can transfer between instruments. The study provides evidence-based strategies for second language teachers to help students apply their language skills beyond the classroom to real-world communication needs. Language educators will gain valuable insights into structuring lessons and activities that promote genuine language transfer rather than simply isolated grammar or vocabulary practise.

Students' Analogical Reasoning in Solving Geometry Problems Viewed from Visualizer's and Verbalizer's Cognitive Style View study ↗

2 citations

Ali Shodikin et al. (2023)

This study investigates how high school students with different thinking styles, visual learners versus verbal processors, approach geometry problem-solving through comparison and pattern recognition. The research addresses the widespread challenge of low geometry achievement by examining how students' natural cognitive preferences affect their ability to connect geometric concepts. Mathematics teachers can use these findings to differentiate instruction and provide multiple pathways for students to understand and apply geometric reasoning based on their individual learning strengths.

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/transfer-learning-complete-guide-teachers#article","headline":"Transfer of Learning: A Complete Guide for Teachers","description":"Transfer of learning explains why students struggle to apply classroom knowledge to new situations and offers research-backed strategies for building...","datePublished":"2025-12-29T18:34:19.842Z","dateModified":"2026-01-26T10:09:32.212Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/transfer-learning-complete-guide-teachers"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/6968db30e78706a5e02d9d06_6952c9abd1c626db8d7fe374_6952c9078b7309392c15df00_transfer-of-learning-a-complet-definition-1767033094605.webp","wordCount":4841},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/transfer-learning-complete-guide-teachers#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"Transfer of Learning: A Complete Guide for Teachers","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/transfer-learning-complete-guide-teachers"}]},{"@type":"FAQPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/transfer-learning-complete-guide-teachers#faq","mainEntity":[{"@type":"Question","name":"Why do my students struggle to apply what they've learnt in my lessons to new situations or other subjects?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Transfer often fails because knowledge remains tied to the specific context where it was learnt, students develop only shallow understanding without grasping underlying principles, or they simply don't retrieve relevant knowledge when facing new situations. When students learn using only textbook pr"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"How can I design lessons for transfer?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Teaching for transfer involves promoting deep conceptual understanding rather than surface memorisation, using multiple varied examples during instruction, and explicitly helping students recognise when and how to apply what they know. You should also focus on helping students abstract general princ"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What are some practical examples of transfer of learning that I might see in my classroom?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Common examples include students using persuasive writing skills learnt in English lessons to construct arguments in history essays, applying addition facts to understand multiplication concepts, or using strategic thinking from chess to approach problem-solving in mathematics. You might also notice"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What are low road vs high road transfer?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Low road transfer occurs automatically through extensive, varied practise that builds strong patterns, primarily supporting near transfer between similar situations. High road transfer involves deliberate, mindful abstraction where learners consciously identify underlying principles and apply them t"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"How can I help students overcome the problem of knowledge remaining context-bound?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"To prevent knowledge from becoming tied to specific learning contexts, you should deliberately vary the examples, problems, and situations you use during instruction rather than relying on single formats or textbook problems. This approach, combined with explicit discussion of how the same principle"}}]}]}