Assessment for Learning: Using Assessment to Drive

Explore effective assessment strategies that enhance student learning. Utilize questioning, feedback, and self-assessment to bridge performance gaps.

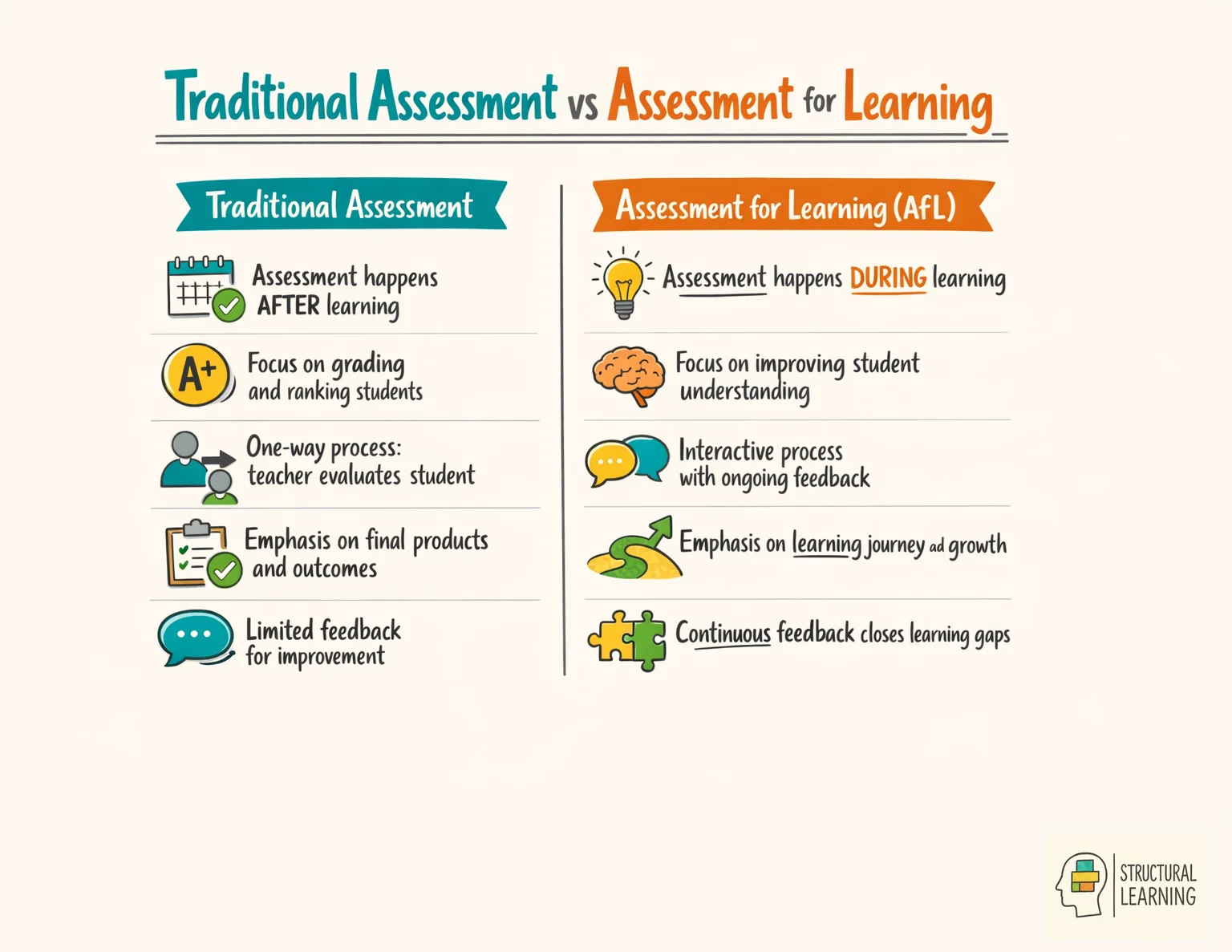

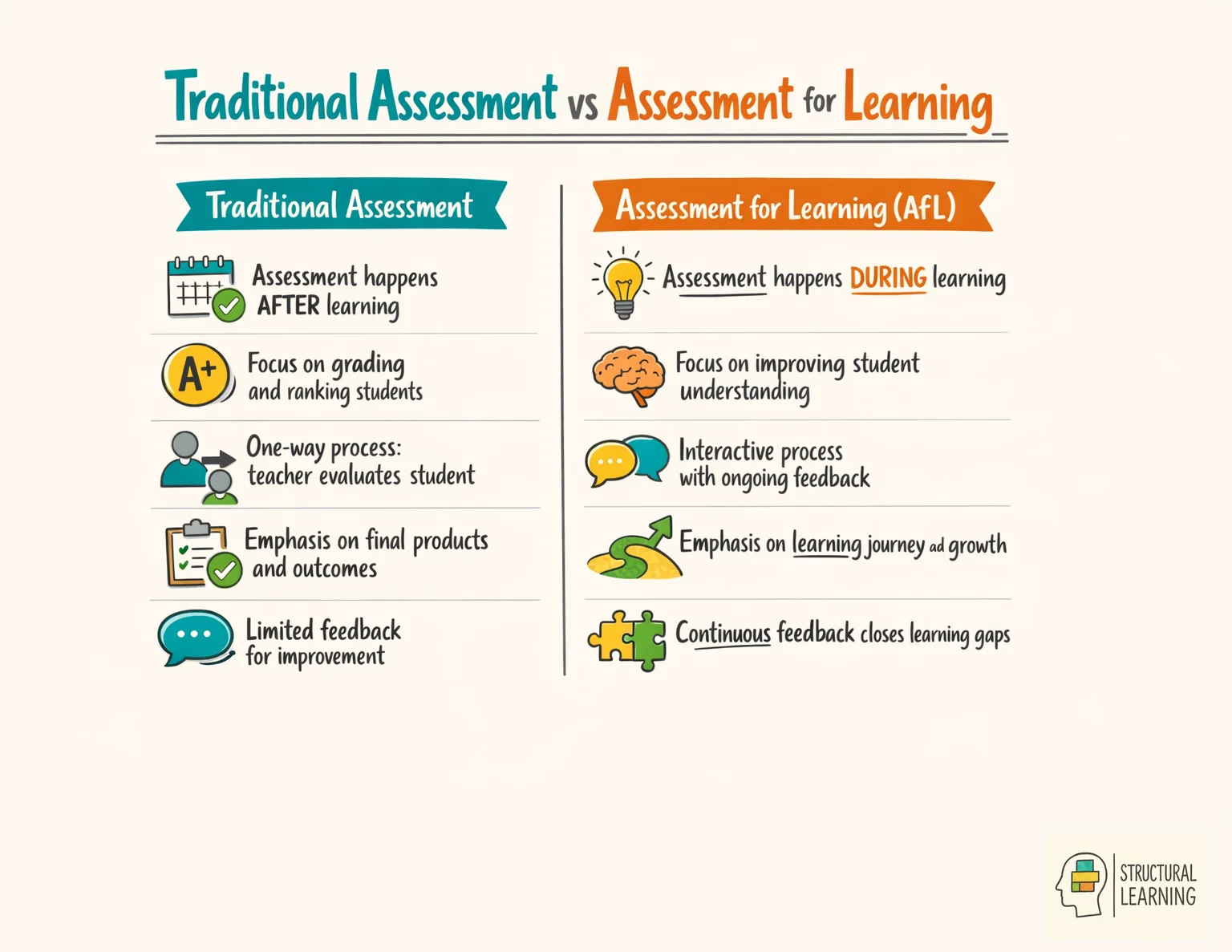

Assessment for Learning (AfL) represents a fundamental shift in how we think about assessment: from measurement that happens after learning to a process that actively promotes learning. This approach aligns with core assessment to learning principlesthat prioritise ongoing feedback and student engagement. Based on the influential research of Black and Wiliam, AfL uses questioning, feedback, and self-assessment to help students understand where they are, where they need to be, and how to close that gap. When implemented effectively, AfL significantly improves outcomes, particularly for lower-achieving students. This guide explains the key strategies and how to embed them in daily practice.

To provide the reader with some guidance about the author would like to commence by outlining an example of a possible learning journey reflected in the topic of 'Bullying', and express that learning journey, via the writing of a newspaper article, used as an English assessment artefact. AI-powered formative assessment can support this process.

Before commencing this learning journey, one needs to simply ask the following question: "What is the purpose of having students write a newspaper article on bullying as an assessment artefact?" Clearly, there are the academic and educational requirements associated with meeting the fulfilment of the ever-expanding list of 'students will learn' expections and via these learning expections the nexus with educational outcome/s, for example, syllabus and curriculum. However, what happens if one looks at the real-life applications of writing a newspaper article on bullying, and then ties this back to the classroom?

[1]Data (Australian) through a national study highlighted approximately 1 in 4 Year 4 to Year 9 Australian students (27%) reported being bullied every few weeks in Australian schools (Google, 2022). While, school bullying was most frequent in Year 5 and Year 8 students (Google, 2022). Within the Australian work place the impact of bullying was reflected in data that suggested 60% of workers experienced some type of bullying in the workplace; 1 in 3 women and 1 in 5 men (Google, 2022). Further data also indicated school-based anti-bullying programs in Australia were effective in the reduction of school-bullying perpetration by approximately 19%-20% and school-bullying victimization by approximately 15%-16% (Google, 2022).

So, if Australian students are learning how to address, or may be cope with, bullying through Australian school-based anti-bullying programs, why is it that when these students leave school, and move into the Australian work place, they are still experiencing bullying, and possibly higher levels of bullying? Are, for example, the anti-bullying programs at school that addressed the reduction of school-bullying perpetration, and school-bullying victimization, not being effectively articulated into the work place?

Surely, one of the core roles of education, as exemplified in the mission and vision[2] statements of some Australian schools, highlighted below, is for schools to educate students on how to demonstrate actions that reflect respect in order to make a better world.

. . Inspires young women to create a better world . .

. . Educates boys within an effective learning culture . . To become global citizens who contribute to their communities.

helped, Resilient . . World Changing!

. . helps students to break the limitations, and build the opportunities for their successful future.

As educators we all strive to do our best to have a positive impact on our students' lives through attempting to educate them to make the world a better place through their actions; for example, inspire, create, contribute, helps and build. One might add that these actions by students represent a very big responsibility for teenagers, remembering that in Australia most students graduate from high school on average at eighteen years of age.

Possibly one way to assist students in address the daunting tasks of creating a better world, becoming global citizens who contribute to their communities, being World Changing and to building the opportunities for their successful future might be through a focus on learning journeys?

Assessment for Learning philosophy centers on using assessment to promote learning rather than simply measure it. Based on Black and Wiliam's research, it emphasises questioning, feedback, and self-assessment as core strategies. This approach shifts the focus from grading to helping students actively participate in their own learningprocess.

AtL's philosophy espouses a view that acknowledges learning is a complex process but one way that learning can be facilitated is through targeting students' understanding. For example, the learning of a particular task is reflected in students' understanding of that task demonstrated either possibly in a written or verbal genre; it should be noted that one of the key attributes of a quality teacher[3] is to check for understanding[4].

Therefore, a lack of learning can be attributed to a lack of understanding whereby, the less one understands something the greater 1) the likelihood of a negative impact on one's life's experiences and, as a consequence, 2) one's learning journey/s. Therefore, two of the seminal issues that need to be addressed are a) cognitive load and b) real-life applications. Effective formative assessment strategies can help teachers address both these challenges by supporting student memory processes and developing thinking skills. When students develop strong self-regulation abilities, they become more capable of maintaining attention and applying critical thinking to their learning. This is particularly important in inclusion settings where students with sen require additional support to access the curriculum effectively.

Effective assessment for learning strategies fall into three core categories that educators can implement immediately to enhance student understanding. Questioning techniques form the foundation, moving beyond simple recall to probe deeper comprehension through wait time, think-pair-share activities, and targeted follow-up questions that reveal misconceptions. Peer assessment activities engage students as learning partners, utilising structured protocols where learners evaluate each other's work against clear criteria, developing metacognitive awareness whilst reducing teacher workload.

Self-assessment tools represent the third pillar, helping students to monitor their own learning journey through reflection journals, learning logs, and exit tickets that capture both understanding and confusion. Dylan Wiliam's research consistently demonstrates that these strategies prove most effective when embedded systematically rather than used sporadically, creating a classroom culture where assessment becomes a natural learning conversation rather than an evaluative interruption.

The key to successful implementation lies in starting small and building confidence gradually. Begin with one strategy per week, such as introducing two-minute reflection cards at lesson conclusions, then progressively incorporate peer feedback sessions and strategic questioning techniques. This measured approach ensures sustainable classroom practice whilst allowing educators to observe genuine improvements in student engagement and understanding across the learning journey.

Effective feedback transforms assessment from a summative judgement into a powerful catalyst for learning, yet many educators struggle to move beyond generic praise or corrective comments. John Hattie's extensive meta-analysis reveals that feedback ranks among the most influential factors in student achievement, but only when it addresses three fundamental questions: Where am I going? How am I going? Where to next? This framework shifts feedback from being teacher-centred to genuinely learning-centred, focusing students' attention on the learning journey rather than performance comparison.

The timing and specificity of feedback prove crucial in determining its impact on student understanding. Research by Butler and Winne demonstrates that immediate, task-specific feedback enhances learning more effectively than delayed, generalised comments. However, cognitive load theory suggests that overwhelming students with too much feedback can actually impede progress. The most effective approach involves providing just-in-time feedback that addresses one or two key learning points, allowing students to process and act upon guidance before going forward.

Successful classroom implementation requires establishing clear feedback routines that prioritise dialogue over monologue. Rather than lengthy written comments that students rarely engage with, consider brief, focused annotations paired with structured peer feedback sessions. This approach not only reduces marking workload but actively involves students in the assessment process, developing their capacity to self-regulate and evaluate their own learning progress.

Helping students to become skilled self-assessors transforms them from passive recipients of feedback into active partners in their learning journey. Dylan Wiliam's research emphasises that when students develop robust self-assessment capabilities, they gain greater ownership of their progress and become more adept at identifying their own learning needs. This shift requires explicit instruction in assessment criteria, regular modelling of the assessment process, and structured opportunities for students to practise evaluating their own work against clear success criteria.

Effective peer assessment serves as a bridge between teacher feedback and student self-reflection, creating opportunities for collaborative learning whilst developing critical evaluation skills. When students assess their peers' work, they must articulate their understanding of quality and apply assessment criteria in meaningful ways. This process deepens their comprehension of learning objectives and provides fresh perspectives on common misconceptions or successful strategies within the classroom community.

Successful implementation begins with scaffolded experiences using simple rubrics or checklists, gradually building towards more sophisticated analytical skills. Teachers should model the assessment process explicitly, demonstrate how to provide constructive feedback, and create safe environments where students feel comfortable sharing honest evaluations. Regular reflection on the assessment process itself helps students refine their skills and increases their confidence in making accurate judgements about learning progress.

Despite widespread recognition of assessment for learning's benefits, many educators encounter predictable barriers during classroom implementation. Time constraints represent the most frequently cited challenge, with teachers struggling to balance formative assessment practices against curriculum demands and administrative requirements. Dylan Wiliam's research emphasises that successful implementation requires gradual integration rather than wholesale transformation, suggesting educators begin with one or two techniques before expanding their assessment repertoire.

Resistance to change, both from students and colleagues, often emerges as teachers shift from traditional assessment approaches. Students may initially struggle with increased responsibility for their learning journey, whilst some staff members question the effectiveness of less formal assessment methods. Collaborative planning sessions prove invaluable here, allowing educators to share experiences and troubleshoot challenges collectively. Building a supportive professional learning community helps normalise the inevitable setbacks that accompany pedagogical change.

Resource limitations and inadequate training frequently compound implementation difficulties. However, effective assessment for learning relies more on thoughtful questioning and feedback strategies than expensive materials or technology. Focus on developing core skills such as crafting effective learning intentions, designing meaningful success criteria, and providing timely, specific feedback. These fundamental practices require minimal resources whilst delivering maximum impact on student understanding and engagement.

Assessment for Learning is a process where teachers and students seek evidence to identify where learners are in their current studies. This evidence helps them decide where they need to go and the best way to get there. It shifts the primary focus from measuring performance to supporting the actual process of improvement.

Teachers use strategies such as effective questioning, peer assessment, and providing comments rather than grades. It involves sharing learning goals with students so they understand the success criteria for every specific task. By checking for understanding throughout a lesson, teachers can adjust their instructions to meet the needs of every child.

This approach helps students become more independent and better at managing their own academic progress. It has been shown to improve results, especially for those who struggle with traditional testing methods. When students receive clear feedback, they are more likely to stay engaged and understand how to perfect their skills.

Evidence from researchers like Black and Wiliam shows that formative assessment is one of the most effective ways to raise standards. Their findings suggest that high quality feedback and self-assessment lead to significant gains in student progress. The data indicates that clear communication about the learning journey leads to better long term retention of knowledge.

A frequent mistake is giving a grade alongside feedback, which often causes students to ignore the advice provided. Another issue is failing to give students enough time to actually practise the improvements suggested by the teacher. Without a supportive classroom environment, students may feel afraid to make the errors necessary for growth.

This method ensures that the curriculum is a meaningful experience for the student rather than just a list of requirements to fulfil. It allows teachers to connect academic tasks to real life scenarios, such as understanding the impact of behaviour in the workplace. This helps students see the value of their education and how it prepares them for future challenges.

The distinction between assessment for learning and assessment of learning represents a fundamental shift in educational practice that transforms how we view the assessment process. Assessment of learning, the traditional summative approach, occurs at the end of instruction to measure what students have achieved. In contrast, assessment for learning is an ongoing, formative process that occurs during instruction to improve student understanding and guide teaching decisions. As Dylan Wiliam's research demonstrates, this shift from assessment as measurement to assessment as learning tool can dramatically enhance student outcomes.

Assessment for learning focuses on the learning journey rather than the destination. It involves students actively in their own assessment through self-evaluation, peer feedback, and collaborative reflection. Teachers use real-time information about student understanding to adjust instruction immediately, whilst students develop metacognitive skills that support their ongoing learning. This approach recognises that the primary purpose of classroom assessment should be to accelerate learning, not merely to document it.

In practical classroom implementation, assessment for learning manifests through strategies such as exit tickets, learning conversations, and purposeful questioning that reveals student thinking. Teachers might use mini-whiteboards to gauge understanding mid-lesson, or implement peer assessment activities that deepen comprehension. The key lies in creating assessment opportunities that inform next steps rather than simply recording achievement levels.

Tell us your assessment purpose, time available, and class setup to receive the best-matched checking-for-understanding strategies.

Choose your feedback type, subject, and time constraints to generate a tailored protocol with marking codes, prompt stems, and workload strategies.

These peer-reviewed studies provide deeper insights into assessment for learning: using assessment to drive improvement and its application in educational settings.

Assessment and Classroom Learning View study ↗7636 citations

Black et al. (1998)

This foundational paper by Black and Wiliam examined over 250 research studies to demonstrate that formative assessment practices significantly improve student achievement. It provides essential evidence and theoretical framework for understanding how classroom assessment can be used to enhance learning rather than simply measure it, making it a cornerstone reference for teachers implementing assessment for learning strategies.

The Next Black Box of Formative Assessment: A Model of the Internal Mechanisms of Feedback Processing View study ↗56 citations

Lui et al. (2022)

This paper explores the internal processes of how students receive and process feedback, shifting focus from what teachers give to what students actually do with assessment information. It helps teachers understand the mechanisms behind effective feedback and why some assessment practices succeed while others fail, providing insights into making formative assessment more impactful for student learning.

The Formative Purpose: Assessment Must First Promote Learning View study ↗202 citations

Black et al. (2004)

Building on their earlier work, Black and Wiliam present refined understanding of formative assessment based on extensive research evidence, emphasising that assessment must primarily serve learning rather than accountability. This paper offers teachers practical insights into implementing formative assessment practices that genuinely improve student outcomes and classroom learning environments.

Causal‐mechanical explanations in biology: Applying automated assessment for personalized learning in the science classroom View study ↗14 citations

Ariely et al. (2024)

This study demonstrates how automated assessment tools can provide personalized feedback to students on scientific explanations, addressing the challenge teachers face in providing timely, detailed feedback on complex student work. It shows teachers how technology can support assessment for learning by making frequent, high-quality feedback more feasible in science classrooms.

Teachers’ Reflective Practices in Implementing Assessment for Learning Skills in Classroom Teaching View study ↗35 citations

Pang(彭新强) et al. (2020)

This research examines how 34 teachers implemented nine specific Assessment for Learning strategies in their classrooms and reflected on their own practices for improvement. It provides teachers with real-world examples of how colleagues have successfully integrated formative assessment techniques and offers practical insights into overcoming common implementation challenges.

Assessment for Learning (AfL) represents a fundamental shift in how we think about assessment: from measurement that happens after learning to a process that actively promotes learning. This approach aligns with core assessment to learning principlesthat prioritise ongoing feedback and student engagement. Based on the influential research of Black and Wiliam, AfL uses questioning, feedback, and self-assessment to help students understand where they are, where they need to be, and how to close that gap. When implemented effectively, AfL significantly improves outcomes, particularly for lower-achieving students. This guide explains the key strategies and how to embed them in daily practice.

To provide the reader with some guidance about the author would like to commence by outlining an example of a possible learning journey reflected in the topic of 'Bullying', and express that learning journey, via the writing of a newspaper article, used as an English assessment artefact. AI-powered formative assessment can support this process.

Before commencing this learning journey, one needs to simply ask the following question: "What is the purpose of having students write a newspaper article on bullying as an assessment artefact?" Clearly, there are the academic and educational requirements associated with meeting the fulfilment of the ever-expanding list of 'students will learn' expections and via these learning expections the nexus with educational outcome/s, for example, syllabus and curriculum. However, what happens if one looks at the real-life applications of writing a newspaper article on bullying, and then ties this back to the classroom?

[1]Data (Australian) through a national study highlighted approximately 1 in 4 Year 4 to Year 9 Australian students (27%) reported being bullied every few weeks in Australian schools (Google, 2022). While, school bullying was most frequent in Year 5 and Year 8 students (Google, 2022). Within the Australian work place the impact of bullying was reflected in data that suggested 60% of workers experienced some type of bullying in the workplace; 1 in 3 women and 1 in 5 men (Google, 2022). Further data also indicated school-based anti-bullying programs in Australia were effective in the reduction of school-bullying perpetration by approximately 19%-20% and school-bullying victimization by approximately 15%-16% (Google, 2022).

So, if Australian students are learning how to address, or may be cope with, bullying through Australian school-based anti-bullying programs, why is it that when these students leave school, and move into the Australian work place, they are still experiencing bullying, and possibly higher levels of bullying? Are, for example, the anti-bullying programs at school that addressed the reduction of school-bullying perpetration, and school-bullying victimization, not being effectively articulated into the work place?

Surely, one of the core roles of education, as exemplified in the mission and vision[2] statements of some Australian schools, highlighted below, is for schools to educate students on how to demonstrate actions that reflect respect in order to make a better world.

. . Inspires young women to create a better world . .

. . Educates boys within an effective learning culture . . To become global citizens who contribute to their communities.

helped, Resilient . . World Changing!

. . helps students to break the limitations, and build the opportunities for their successful future.

As educators we all strive to do our best to have a positive impact on our students' lives through attempting to educate them to make the world a better place through their actions; for example, inspire, create, contribute, helps and build. One might add that these actions by students represent a very big responsibility for teenagers, remembering that in Australia most students graduate from high school on average at eighteen years of age.

Possibly one way to assist students in address the daunting tasks of creating a better world, becoming global citizens who contribute to their communities, being World Changing and to building the opportunities for their successful future might be through a focus on learning journeys?

Assessment for Learning philosophy centers on using assessment to promote learning rather than simply measure it. Based on Black and Wiliam's research, it emphasises questioning, feedback, and self-assessment as core strategies. This approach shifts the focus from grading to helping students actively participate in their own learningprocess.

AtL's philosophy espouses a view that acknowledges learning is a complex process but one way that learning can be facilitated is through targeting students' understanding. For example, the learning of a particular task is reflected in students' understanding of that task demonstrated either possibly in a written or verbal genre; it should be noted that one of the key attributes of a quality teacher[3] is to check for understanding[4].

Therefore, a lack of learning can be attributed to a lack of understanding whereby, the less one understands something the greater 1) the likelihood of a negative impact on one's life's experiences and, as a consequence, 2) one's learning journey/s. Therefore, two of the seminal issues that need to be addressed are a) cognitive load and b) real-life applications. Effective formative assessment strategies can help teachers address both these challenges by supporting student memory processes and developing thinking skills. When students develop strong self-regulation abilities, they become more capable of maintaining attention and applying critical thinking to their learning. This is particularly important in inclusion settings where students with sen require additional support to access the curriculum effectively.

Effective assessment for learning strategies fall into three core categories that educators can implement immediately to enhance student understanding. Questioning techniques form the foundation, moving beyond simple recall to probe deeper comprehension through wait time, think-pair-share activities, and targeted follow-up questions that reveal misconceptions. Peer assessment activities engage students as learning partners, utilising structured protocols where learners evaluate each other's work against clear criteria, developing metacognitive awareness whilst reducing teacher workload.

Self-assessment tools represent the third pillar, helping students to monitor their own learning journey through reflection journals, learning logs, and exit tickets that capture both understanding and confusion. Dylan Wiliam's research consistently demonstrates that these strategies prove most effective when embedded systematically rather than used sporadically, creating a classroom culture where assessment becomes a natural learning conversation rather than an evaluative interruption.

The key to successful implementation lies in starting small and building confidence gradually. Begin with one strategy per week, such as introducing two-minute reflection cards at lesson conclusions, then progressively incorporate peer feedback sessions and strategic questioning techniques. This measured approach ensures sustainable classroom practice whilst allowing educators to observe genuine improvements in student engagement and understanding across the learning journey.

Effective feedback transforms assessment from a summative judgement into a powerful catalyst for learning, yet many educators struggle to move beyond generic praise or corrective comments. John Hattie's extensive meta-analysis reveals that feedback ranks among the most influential factors in student achievement, but only when it addresses three fundamental questions: Where am I going? How am I going? Where to next? This framework shifts feedback from being teacher-centred to genuinely learning-centred, focusing students' attention on the learning journey rather than performance comparison.

The timing and specificity of feedback prove crucial in determining its impact on student understanding. Research by Butler and Winne demonstrates that immediate, task-specific feedback enhances learning more effectively than delayed, generalised comments. However, cognitive load theory suggests that overwhelming students with too much feedback can actually impede progress. The most effective approach involves providing just-in-time feedback that addresses one or two key learning points, allowing students to process and act upon guidance before going forward.

Successful classroom implementation requires establishing clear feedback routines that prioritise dialogue over monologue. Rather than lengthy written comments that students rarely engage with, consider brief, focused annotations paired with structured peer feedback sessions. This approach not only reduces marking workload but actively involves students in the assessment process, developing their capacity to self-regulate and evaluate their own learning progress.

Helping students to become skilled self-assessors transforms them from passive recipients of feedback into active partners in their learning journey. Dylan Wiliam's research emphasises that when students develop robust self-assessment capabilities, they gain greater ownership of their progress and become more adept at identifying their own learning needs. This shift requires explicit instruction in assessment criteria, regular modelling of the assessment process, and structured opportunities for students to practise evaluating their own work against clear success criteria.

Effective peer assessment serves as a bridge between teacher feedback and student self-reflection, creating opportunities for collaborative learning whilst developing critical evaluation skills. When students assess their peers' work, they must articulate their understanding of quality and apply assessment criteria in meaningful ways. This process deepens their comprehension of learning objectives and provides fresh perspectives on common misconceptions or successful strategies within the classroom community.

Successful implementation begins with scaffolded experiences using simple rubrics or checklists, gradually building towards more sophisticated analytical skills. Teachers should model the assessment process explicitly, demonstrate how to provide constructive feedback, and create safe environments where students feel comfortable sharing honest evaluations. Regular reflection on the assessment process itself helps students refine their skills and increases their confidence in making accurate judgements about learning progress.

Despite widespread recognition of assessment for learning's benefits, many educators encounter predictable barriers during classroom implementation. Time constraints represent the most frequently cited challenge, with teachers struggling to balance formative assessment practices against curriculum demands and administrative requirements. Dylan Wiliam's research emphasises that successful implementation requires gradual integration rather than wholesale transformation, suggesting educators begin with one or two techniques before expanding their assessment repertoire.

Resistance to change, both from students and colleagues, often emerges as teachers shift from traditional assessment approaches. Students may initially struggle with increased responsibility for their learning journey, whilst some staff members question the effectiveness of less formal assessment methods. Collaborative planning sessions prove invaluable here, allowing educators to share experiences and troubleshoot challenges collectively. Building a supportive professional learning community helps normalise the inevitable setbacks that accompany pedagogical change.

Resource limitations and inadequate training frequently compound implementation difficulties. However, effective assessment for learning relies more on thoughtful questioning and feedback strategies than expensive materials or technology. Focus on developing core skills such as crafting effective learning intentions, designing meaningful success criteria, and providing timely, specific feedback. These fundamental practices require minimal resources whilst delivering maximum impact on student understanding and engagement.

Assessment for Learning is a process where teachers and students seek evidence to identify where learners are in their current studies. This evidence helps them decide where they need to go and the best way to get there. It shifts the primary focus from measuring performance to supporting the actual process of improvement.

Teachers use strategies such as effective questioning, peer assessment, and providing comments rather than grades. It involves sharing learning goals with students so they understand the success criteria for every specific task. By checking for understanding throughout a lesson, teachers can adjust their instructions to meet the needs of every child.

This approach helps students become more independent and better at managing their own academic progress. It has been shown to improve results, especially for those who struggle with traditional testing methods. When students receive clear feedback, they are more likely to stay engaged and understand how to perfect their skills.

Evidence from researchers like Black and Wiliam shows that formative assessment is one of the most effective ways to raise standards. Their findings suggest that high quality feedback and self-assessment lead to significant gains in student progress. The data indicates that clear communication about the learning journey leads to better long term retention of knowledge.

A frequent mistake is giving a grade alongside feedback, which often causes students to ignore the advice provided. Another issue is failing to give students enough time to actually practise the improvements suggested by the teacher. Without a supportive classroom environment, students may feel afraid to make the errors necessary for growth.

This method ensures that the curriculum is a meaningful experience for the student rather than just a list of requirements to fulfil. It allows teachers to connect academic tasks to real life scenarios, such as understanding the impact of behaviour in the workplace. This helps students see the value of their education and how it prepares them for future challenges.

The distinction between assessment for learning and assessment of learning represents a fundamental shift in educational practice that transforms how we view the assessment process. Assessment of learning, the traditional summative approach, occurs at the end of instruction to measure what students have achieved. In contrast, assessment for learning is an ongoing, formative process that occurs during instruction to improve student understanding and guide teaching decisions. As Dylan Wiliam's research demonstrates, this shift from assessment as measurement to assessment as learning tool can dramatically enhance student outcomes.

Assessment for learning focuses on the learning journey rather than the destination. It involves students actively in their own assessment through self-evaluation, peer feedback, and collaborative reflection. Teachers use real-time information about student understanding to adjust instruction immediately, whilst students develop metacognitive skills that support their ongoing learning. This approach recognises that the primary purpose of classroom assessment should be to accelerate learning, not merely to document it.

In practical classroom implementation, assessment for learning manifests through strategies such as exit tickets, learning conversations, and purposeful questioning that reveals student thinking. Teachers might use mini-whiteboards to gauge understanding mid-lesson, or implement peer assessment activities that deepen comprehension. The key lies in creating assessment opportunities that inform next steps rather than simply recording achievement levels.

Tell us your assessment purpose, time available, and class setup to receive the best-matched checking-for-understanding strategies.

Choose your feedback type, subject, and time constraints to generate a tailored protocol with marking codes, prompt stems, and workload strategies.

These peer-reviewed studies provide deeper insights into assessment for learning: using assessment to drive improvement and its application in educational settings.

Assessment and Classroom Learning View study ↗7636 citations

Black et al. (1998)

This foundational paper by Black and Wiliam examined over 250 research studies to demonstrate that formative assessment practices significantly improve student achievement. It provides essential evidence and theoretical framework for understanding how classroom assessment can be used to enhance learning rather than simply measure it, making it a cornerstone reference for teachers implementing assessment for learning strategies.

The Next Black Box of Formative Assessment: A Model of the Internal Mechanisms of Feedback Processing View study ↗56 citations

Lui et al. (2022)

This paper explores the internal processes of how students receive and process feedback, shifting focus from what teachers give to what students actually do with assessment information. It helps teachers understand the mechanisms behind effective feedback and why some assessment practices succeed while others fail, providing insights into making formative assessment more impactful for student learning.

The Formative Purpose: Assessment Must First Promote Learning View study ↗202 citations

Black et al. (2004)

Building on their earlier work, Black and Wiliam present refined understanding of formative assessment based on extensive research evidence, emphasising that assessment must primarily serve learning rather than accountability. This paper offers teachers practical insights into implementing formative assessment practices that genuinely improve student outcomes and classroom learning environments.

Causal‐mechanical explanations in biology: Applying automated assessment for personalized learning in the science classroom View study ↗14 citations

Ariely et al. (2024)

This study demonstrates how automated assessment tools can provide personalized feedback to students on scientific explanations, addressing the challenge teachers face in providing timely, detailed feedback on complex student work. It shows teachers how technology can support assessment for learning by making frequent, high-quality feedback more feasible in science classrooms.

Teachers’ Reflective Practices in Implementing Assessment for Learning Skills in Classroom Teaching View study ↗35 citations

Pang(彭新强) et al. (2020)

This research examines how 34 teachers implemented nine specific Assessment for Learning strategies in their classrooms and reflected on their own practices for improvement. It provides teachers with real-world examples of how colleagues have successfully integrated formative assessment techniques and offers practical insights into overcoming common implementation challenges.

<script type="application/ld+json">{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/assessment-to-learning#article","headline":"Assessment for Learning: Using Assessment to Drive Improvement","description":"Explore effective assessment strategies that enhance student learning. Utilize questioning, feedback, and self-assessment to bridge performance gaps.","datePublished":"2023-04-17T16:22:10.288Z","dateModified":"2026-03-02T11:00:58.406Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/assessment-to-learning"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/69661b55ac3c6f12087a1df8_69661b4b0043cdc7d99656a2_assessment-to-learning-infographic.webp","wordCount":2457},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/assessment-to-learning#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"Assessment for Learning: Using Assessment to Drive Improvement","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/assessment-to-learning"}]},{"@type":"FAQPage","mainEntity":[{"@type":"Question","name":"What is Assessment for Learning in education?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Assessment for Learning is a process where teachers and students seek evidence to identify where learners are in their current studies. This evidence helps them decide where they need to go and the best way to get there. It shifts the primary focus from measuring performance to supporting the actual process of improvement."}},{"@type":"Question","name":"How do teachers implement Assessment for Learning in the classroom?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Teachers use strategies such as effective questioning, peer assessment, and providing comments rather than grades. It involves sharing learning goals with students so they understand the success criteria for every specific task. By checking for understanding throughout a lesson, teachers can adjust their instructions to meet the needs of every child."}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What are the benefits of Assessment for Learning for students?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"This approach helps students become more independent and better at managing their own academic progress. It has been shown to improve results, especially for those who struggle with traditional testing methods. When students receive clear feedback, they are more likely to stay engaged and understand how to perfect their skills."}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What does the research say about Assessment for Learning?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Evidence from researchers like Black and Wiliam shows that formative assessment is one of the most effective ways to raise standards. Their findings suggest that high quality feedback and self-assessment lead to significant gains in student progress. The data indicates that clear communication about the learning journey leads to better long term retention of knowledge."}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What are common mistakes when using Assessment for Learning?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"A frequent mistake is giving a grade alongside feedback, which often causes students to ignore the advice provided. Another issue is failing to give students enough time to actually practise the improvements suggested by the teacher. Without a supportive classroom environment, students may feel afraid to make the errors necessary for growth."}},{"@type":"Question","name":"Why is the Assessment for Learning approach important for the curriculum?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"This method ensures that the curriculum is a meaningful experience for the student rather than just a list of requirements to fulfil. It allows teachers to connect academic tasks to real life scenarios, such as understanding the impact of behaviour in the workplace. This helps students see the value of their education and how it prepares them for future challenges."}}]}]}</script>