Updated on

February 17, 2026

Neuroplasticity in Education: What Teachers Need to Know About the Learning Brain

|

February 17, 2026

Updated on

February 17, 2026

|

February 17, 2026

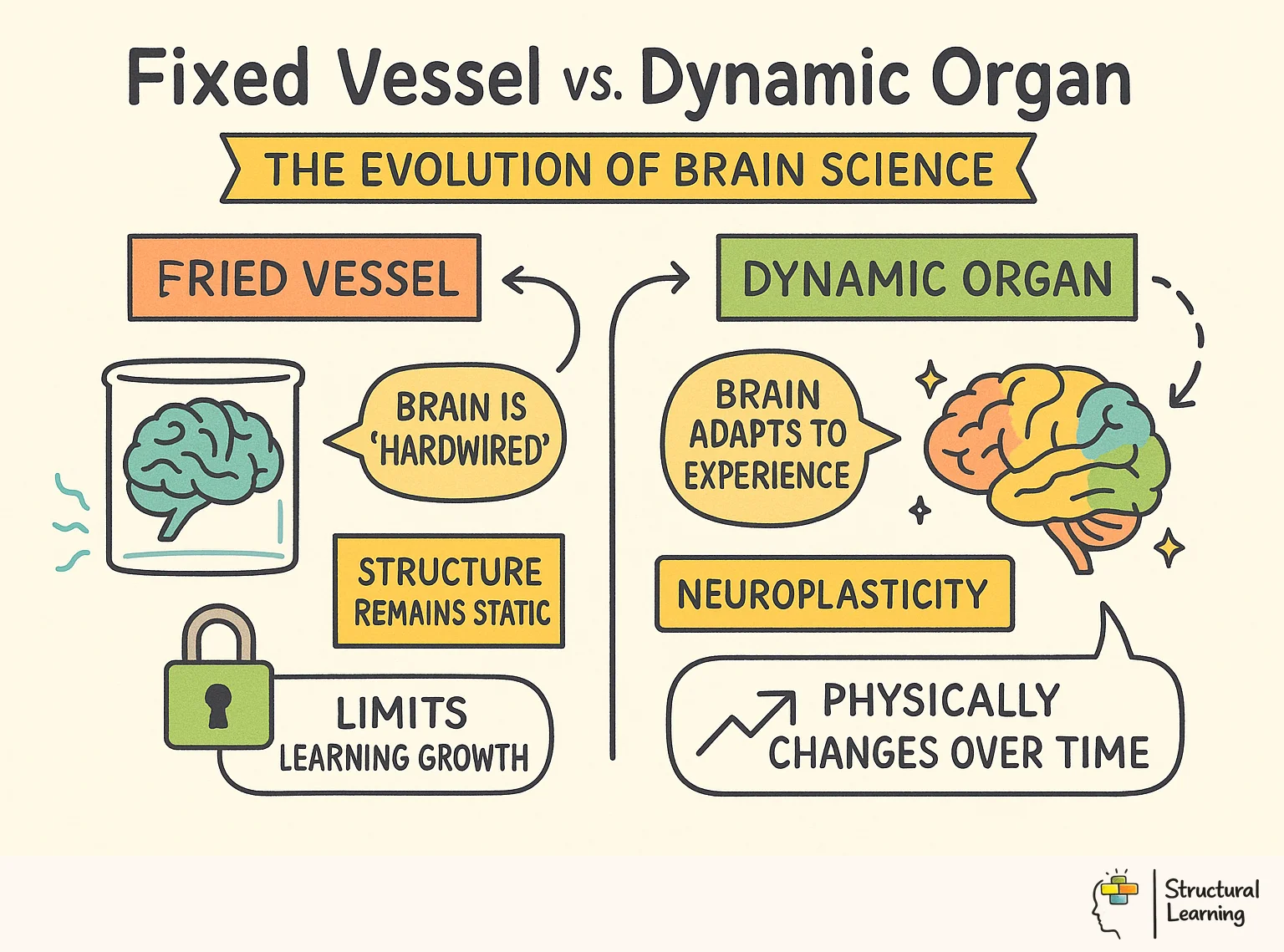

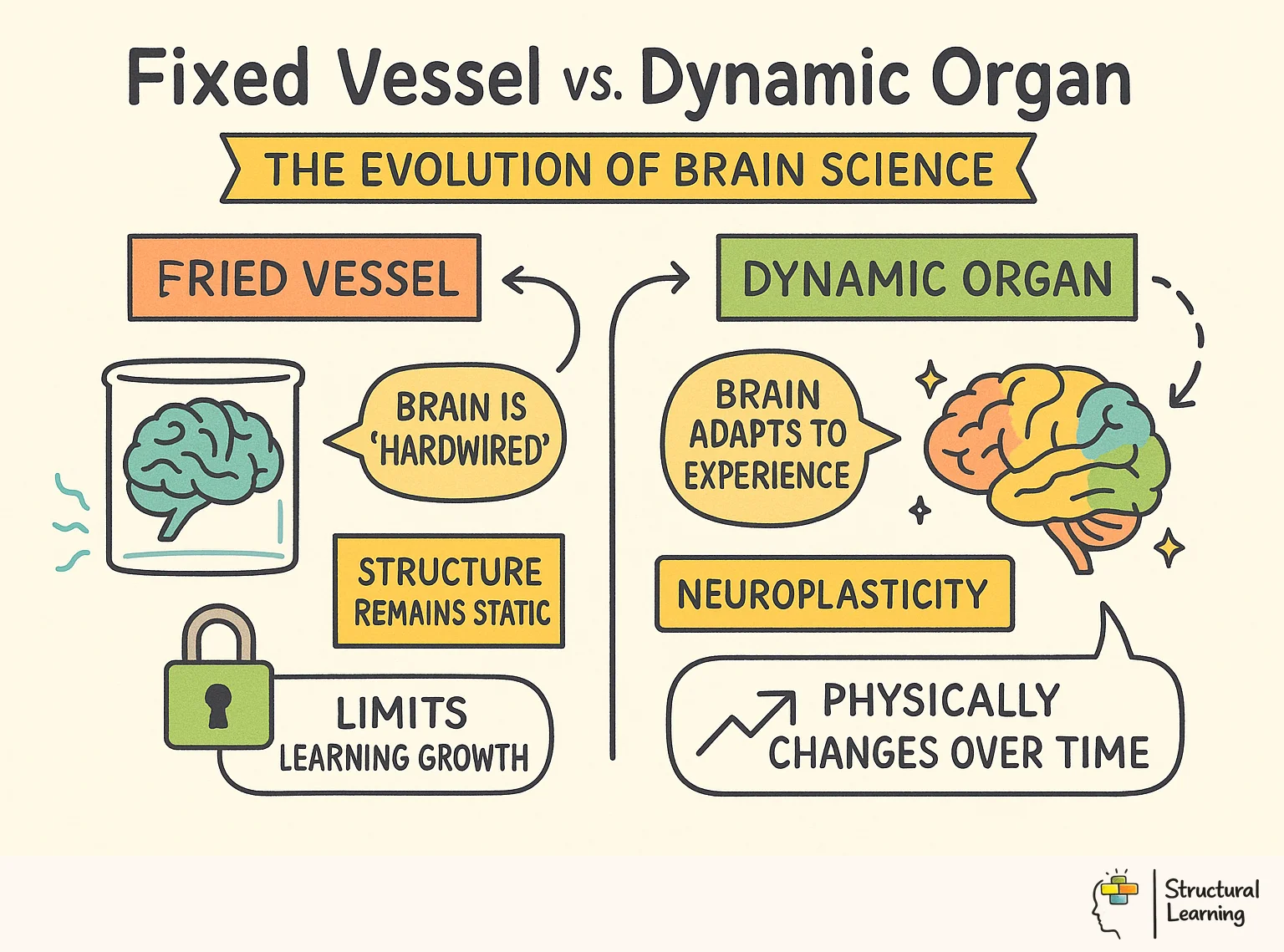

For decades, many educators operated under the assumption that the brain was a fixed vessel. We believed that once a child reached a certain age, their cognitive potential was largely determined. Modern neuroscience has proven this view entirely incorrect. The brain is not a static machine but a dynamic, living organ that physically changes in response to every lesson, interaction, and challenge.

Understanding neuroplasticity allows teachers to move beyond the frustration of "stuck" students. It provides the biological evidence that every learner possesses the capacity for structural change. This article examines how these changes occur and what they mean for daily classroom practise. We will strip away the hype to focus on the hard science that helps students build stronger, more resilient neural networks.

* Neural pathways are physically forged through effort: Learning is a biological process of building and strengthening synaptic connections rather than just acquiring information.

* The brain remains plastic throughout life: While "sensitive periods" exist for certain skills, the adult brain retains a remarkable ability to reorganise itself and learn new complex tasks.

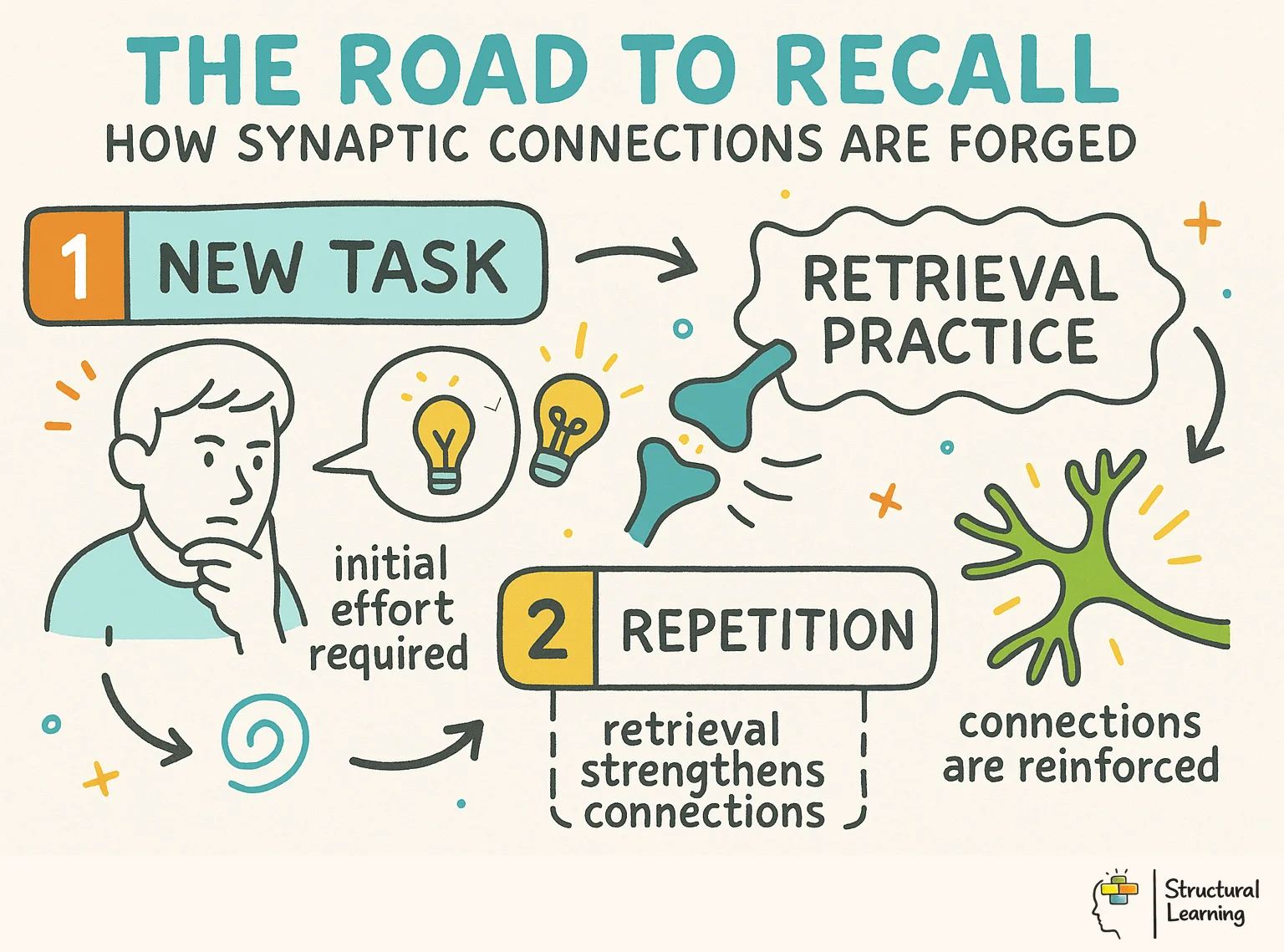

* Retrieval practise is the primary driver of structural change: Actively pulling information from memory strengthens the neural "roads" that make future recall faster and more reliable.

* Sleep and physical health are non-negotiable for plasticity: Biological factors like rest and exercise release the proteins necessary for new synapses to stabilise.

* Neuromyths hinder effective teaching: Concepts like "learning styles" ignore how the brain actually processes information and can limit a student's perceived potential.

* Neuroplasticity provides the "why" for growth mindset: When students understand that their brains can physically grow, they often show higher levels of persistence and resilience.

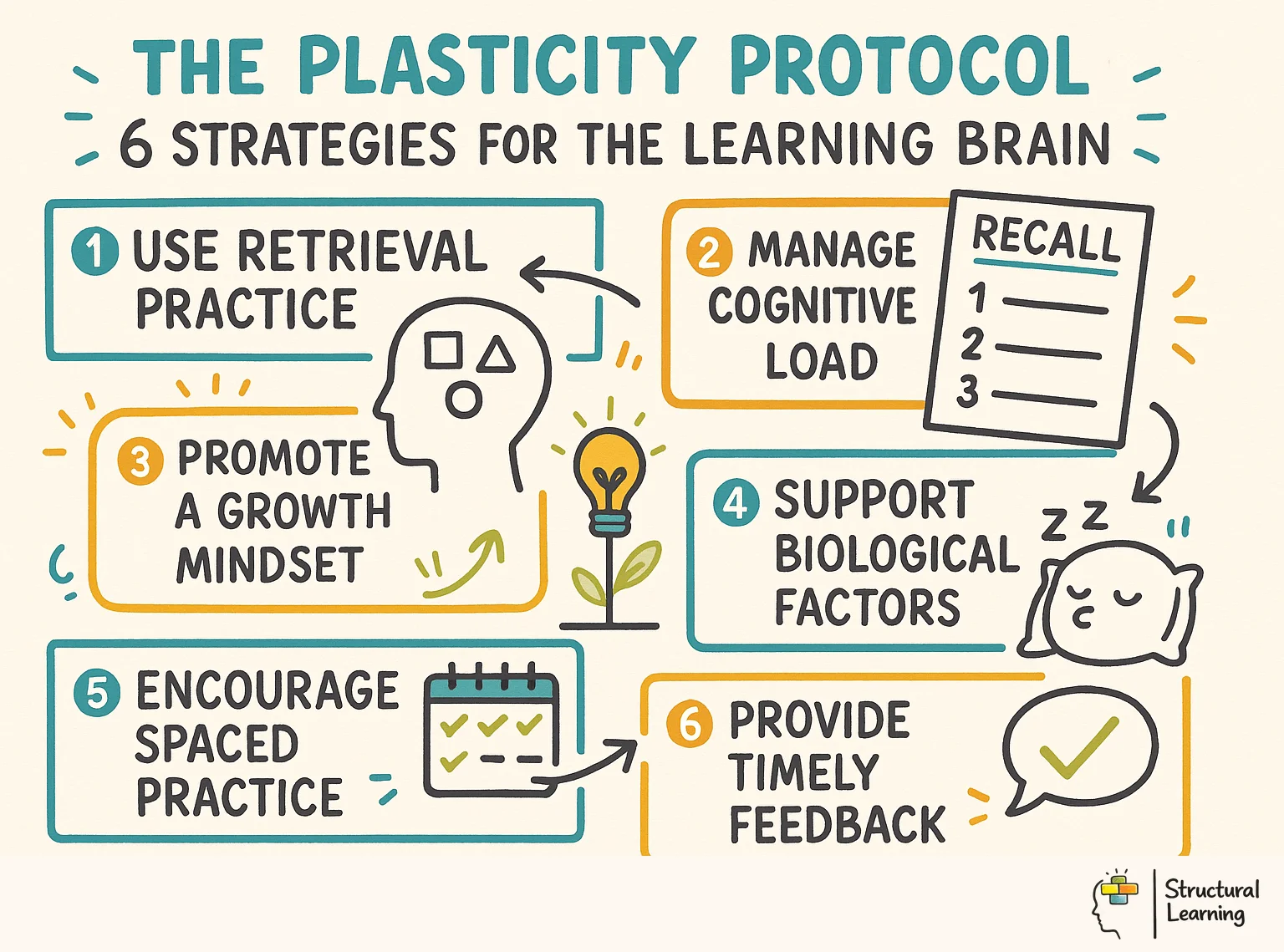

* Classroom strategies must align with cognitive load: Plasticity occurs most efficiently when tasks are challenging enough to trigger change but not so difficult that they overwhelm working memory.

Neuroplasticity refers to the brain's ability to modify its own structure and function based on experience. It is the physical manifestation of learning. When a student masters a new mathematical concept or learns a second language, their brain is physically different than it was before the lesson. This change happens at several levels, from individual molecules at the synapse to large scale remapping of the cerebral cortex.

Historically, scientists believed the brain was "hardwired" after early childhood. This rigid view suggested that if a child did not master a skill during a specific window, the opportunity was lost forever. Michael Merzenich, one of the pioneers of plasticity research, challenged this dogma. His work demonstrated that the brain remains "plastic" and adaptable well into old age. He showed that with the right kind of intensive training, the brain can rewrite its own maps.

In the classroom, neuroplasticity means that intelligence is not a fixed trait. It is more like a muscle that develops through targeted use. This does not mean that every student starts from the same point or that learning is effortless. It does mean that the ceiling for what a student can achieve is far higher than we previously thought. For a sceptical teacher, this is not just "positive thinking" but a biological fact.

The process is often described as "neurons that fire together, wire together." This phrase, attributed to Donald Hebb, simplifies a complex biological reality. When two neurons communicate frequently, the connection between them becomes more efficient. This efficiency is what allows a student to move from slow, effortful decoding of words to fluent, automatic reading. The "wiring" is the physical evidence of hours of classroom work.

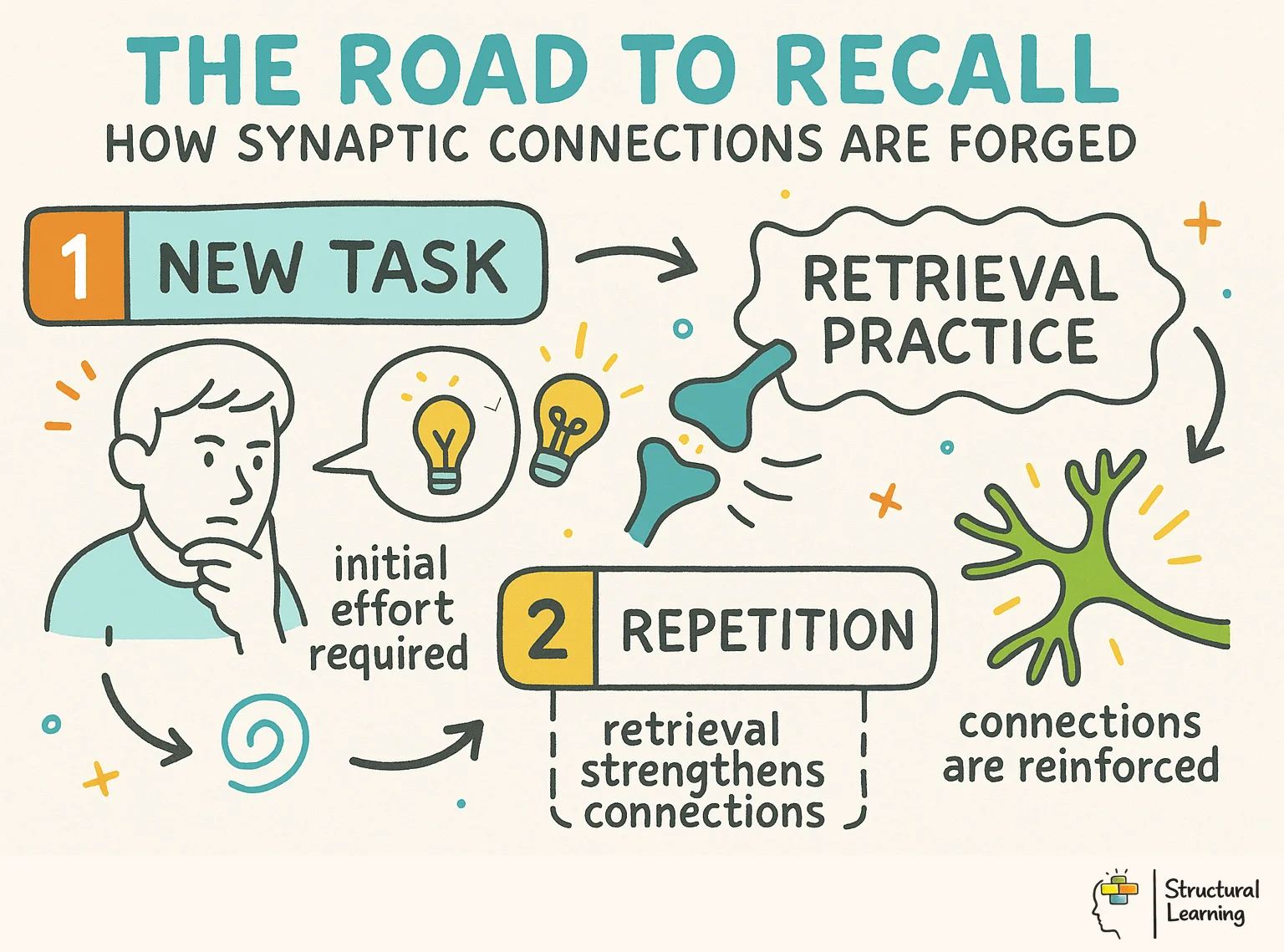

To understand how a student's brain changes, we must look at the synapse. This is the tiny gap where two neurons communicate. Learning involves a process called Long-Term Potentiation (LTP). When a student repeats a task or recalls information, the sending neuron releases more neurotransmitters and the receiving neuron becomes more sensitive. This makes the signal stronger and easier to trigger in the future.

This is not just a chemical change. It is a structural one. New synaptic "buds" can grow, and existing connections can be coated in a fatty substance called myelin. Myelin acts like insulation on an electrical wire. It can speed up neural signals by up to a hundred times. This is why a Year 11 student can solve an algebra problem in seconds that would have taken them ten minutes in Year 7. Their pathways are better insulated.

Synaptic pruning is the equally important opposite of this process. The brain is an energy-intensive organ and cannot keep every connection it ever makes. If a pathway is not used, the brain eventually "prunes" it away to save resources. This explains why students forget content over the summer holidays if they do not revisit it. Pruning ensures the brain remains efficient by focusing on the pathways that are used most frequently.

Norman Doidge, in his work on the brain's adaptability, describes this as "competitive plasticity." The different areas of the brain are constantly competing for space. If a student spends hours practising the piano, the area of the brain responsible for finger movement will physically expand into neighbouring territory. Conversely, if a student stops reading, the literacy pathways will begin to shrink. The classroom is a constant battleground for neural real estate.

The concept of "critical periods" has often been misinterpreted by educators. It is true that there are "sensitive periods" where the brain is exceptionally primed for certain types of learning. Language acquisition is a classic example. Children who learn a second language before age seven typically achieve native-like fluency because their brains are in a state of hyper-plasticity for phonemes and syntax.

However, the "window" does not slam shut. While it may be more difficult to learn a language as an adult, neuroplasticity ensures it is still possible. The adult brain uses different mechanisms to achieve the same result. Instead of the effortless "absorption" seen in toddlers, adults rely on conscious attention and deliberate strategies. Teachers should avoid telling students it is "too late" to learn a skill. The brain remains capable of change as long as it is challenged.

In a primary setting, teachers see the peak of this sensitive period. Children's brains are creating trillions of synapses, many of which will later be pruned. This is why early intervention is so critical. If a child has a hearing difficulty or a vision problem during these years, the brain may remap itself in ways that are hard to undo later. The biological stakes are high in the early years, but they remain significant throughout secondary education.

For secondary teachers, the focus shifts to the "second window" of plasticity during adolescence. The teenage brain undergoes a massive structural overhaul, particularly in the prefrontal cortex. This area is responsible for planning, impulse control, and metacognition. While this period is often associated with risk-taking, it is also a time of profound cognitive growth. Adolescents are biologically primed to develop high-level reasoning skills if the curriculum provides the right stimulus.

Carol Dweck's work on growth mindset is often cited alongside neuroplasticity. The two concepts are related but distinct. Neuroplasticity is the physical mechanism, while growth mindset is the psychological belief in that mechanism. A student who believes their intelligence can grow is more likely to engage in the hard work that actually triggers neural change. Without the effort, the plasticity does not happen.

A common "false growth mindset" occurs when teachers praise effort alone. Simply trying hard does not change the brain if the student is using an ineffective strategy. Dweck has clarified that growth mindset must involve trying new strategies and seeking help when stuck. Neuroplasticity requires "deliberate practise," a concept championed by K. Anders Ericsson. This involves working at the edge of one's capability, which is where the most significant neural changes occur.

Teachers must be careful not to present neuroplasticity as a magical solution. It is a slow, physically demanding process. If a student is told their brain can grow but they do not see immediate results, they may become more discouraged. We should frame plasticity as a "long game." It is the result of consistent, daily habits rather than a sudden "aha" moment. The biology supports the effort, but it does not replace it.

Another caveat is that some cognitive traits have a stronger genetic component than others. While everyone's brain is plastic, the rate and ease of change can vary. This is why some students require five repetitions to master a concept while others need fifty. Acknowledging this reality helps teachers avoid the trap of "toxic positivity." We celebrate that everyone can improve, while respecting that the process looks different for every individual.

Retrieval practise is perhaps the most powerful tool for driving neuroplasticity in the classroom. When a student takes a low-stakes quiz or tries to explain a concept from memory, they are not just "checking" what they know. They are physically strengthening the neural pathway associated with that information. This is why being tested on material is far more effective for long-term retention than simply re-reading it.

Barak Rosenshine's Principles of Instruction align perfectly with these neural mechanics. His emphasis on daily and weekly review ensures that pathways are revisited before they can be pruned. Each time a student retrieves a memory, that memory becomes more "stable" and easier to access. In neurological terms, the connections are becoming more efficient and the myelin sheath is thickening. This is the biological basis of fluency.

Consider the difference between a student who reads their notes ten times and a student who reads them once and then tests themselves nine times. The first student is creating a "familiarity" that feels like learning but is actually shallow. The second student is forcing their brain to reconstruct the information. This reconstruction is what triggers the release of the chemicals needed for synaptic growth. Effortful retrieval is the signal the brain needs to prioritise that specific information.

In the classroom, this means we should prioritise "active recall" over passive consumption. Instead of showing a video and hoping it sticks, we should pause every five minutes and ask students to write down three key facts. These small, frequent "test" events act as biological signals. They tell the brain: "This information is important; build a permanent road to it." Over time, these small roads become motorways of knowledge.

Neuroplasticity does not happen in a vacuum. It requires a specific biological environment. One of the most critical factors is Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF). This protein acts like "fertiliser" for the brain. It encourages the growth of new neurons and protects existing ones. Research shows that physical exercise is one of the most effective ways to increase BDNF levels. A short burst of activity before a challenging lesson can literally prime the brain for change.

Sleep is equally essential. Most of the structural changes triggered during the school day actually occur while the student is asleep. During deep sleep, the brain "replays" the neural patterns formed during the day, a process called consolidation. This is when the chemical changes at the synapse are converted into permanent structural changes. A student who stays up late gaming is not just tired the next day; they are actively sabotaging the learning they did the day before.

For busy teachers, this suggests that "wellbeing" is not a separate topic from "attainment." If a student is chronically sleep-deprived, no amount of high-quality instruction will result in significant plasticity. The brain simply lacks the biological resources to build new connections. Educating students about the "biology of learning" can be a powerful motivator. When they understand that sleep is when their "brain grows," they may take their bedtime more seriously.

Nutrition also plays a supporting role. The brain uses about twenty per cent of the body's total energy. It requires a steady supply of glucose and specific fatty acids to build myelin and maintain cell membranes. While teachers cannot control what students eat at home, they can advocate for healthy school meals and encourage students to stay hydrated. A hungry brain is a rigid brain, focused on survival rather than structural expansion.

Neuroplasticity offers a hopeful framework for supporting neurodivergent students. In the past, conditions like dyslexia or ADHD were seen as permanent "deficits." We now understand that these brains are simply wired differently. While certain pathways may be less efficient, neuroplasticity allows the brain to build "workarounds." This is the core of many successful interventions for learning difficulties.

In students with dyslexia, for example, the pathways connecting the visual and auditory parts of the brain are often weaker. Targeted, intensive phonics instruction can physically strengthen these connections. In some cases, the brain can even learn to use different areas in the right hemisphere to compensate for weaknesses in the left. This remapping is a direct result of the brain's plastic nature. It takes more effort and time, but the physical change is possible.

For students with ADHD, the challenge often lies in the pathways related to dopamine and executive function. Neuroplasticity suggests that these "attention muscles" can be trained. Techniques like mindfulness or structured planning routines can, over time, strengthen the prefrontal cortex. The goal is not to "cure" neurodivergence but to help the student build the most efficient neural version of themselves. This shifts the focus from "what is wrong with the student" to "how can we help this brain adapt."

Teachers should be aware that neuroplasticity can also work against a student. If a child with autism is repeatedly exposed to overwhelming sensory environments, their brain may become "hyper-plastic" in its stress response. They are literally becoming better at being stressed. This is why a calm, predictable classroom environment is so important. We want the brain to be plastic in its learning pathways, not in its anxiety circuits.

The popularity of "brain-based learning" has unfortunately led to the spread of several neuromyths. These are oversimplified or misunderstood scientific concepts that have no evidence base. One of the most persistent is "learning styles." The idea that some students are "visual" and others are "auditory" is entirely unsupported by neuroscience. The brain is highly interconnected; we process information using multiple senses simultaneously.

Believing in learning styles can actually limit neuroplasticity. If a student thinks they "can't do" auditory tasks, they may avoid the very activities that would strengthen those neural pathways. They become trapped in a self-fulfilling prophecy of limited growth. Effective teaching involves "dual coding," where we present information in both visual and verbal forms. This creates multiple neural pathways to the same concept, making it more likely to stick.

Another common myth is that we only use ten per cent of our brains. This is completely false. Imaging technology shows that almost every part of the brain is active over a twenty-four-hour period. Even during sleep, the brain is busy consolidating memories and cleaning out toxins. The "ten per cent" myth is often used to sell expensive "brain training" programmes that have little impact on classroom performance. The best brain training is a rigorous, well-designed curriculum.

The "left-brain vs right-brain" distinction is also a gross oversimplification. While some functions are lateralised, the two halves of the brain are in constant communication through a massive bridge called the corpus callosum. There is no such thing as a "purely creative" right-brain student or a "purely logical" left-brain student. Every complex task, from writing a poem to solving an equation, requires the whole brain to work in harmony.

| Claim / Concept | Scientific Status | Evidence Summary |

| :--- | :--- | :--- |

| Neuroplasticity | Fact | Extensive evidence from MRI and cellular biology shows the brain changes structure based on experience. |

| Learning Styles | Myth | Multiple large-scale reviews find no evidence that teaching to a "style" improves learning outcomes. |

| Retrieval Practise | Fact | Strong evidence shows that active recall strengthens neural pathways more effectively than re-reading. |

| 10% Brain Usage | Myth | Brain scans show all areas of the brain are active throughout the day, even during rest. |

| Critical Periods | Nuance | "Sensitive periods" exist for early skills, but the brain remains plastic and capable of learning throughout life. |

| Left vs Right Brain | Myth | While some functions are lateralised, all complex tasks require both hemispheres to work together. |

| BDNF and Exercise | Fact | Physical activity is proven to increase the proteins that support synaptic growth and neural health. |

| Brain Gym | Myth | No credible scientific evidence supports the claim that specific body movements can "switch on" parts of the brain. |

To harness neuroplasticity, we must move beyond the "one-off" lesson. Since plasticity is a structural change, it requires repetition and time. Spacing is a vital strategy here. Instead of teaching a topic in a single block, we should "space" the practise out over days, weeks, and months. This forces the brain to repeatedly reconstruct the pathway, which is the signal it needs to make the change permanent.

Interleaving is another powerful technique. This involves mixing up different types of problems or topics within a single practise session. For example, in a maths lesson, instead of doing twenty identical "long division" problems, students should do a mix of addition, division, and fractions. This is harder for the student and feels slower, but it leads to better long-term retention. Neurologically, it forces the brain to "choose" the right pathway each time, strengthening the decision-making circuits.

Dual coding helps build "redundant" pathways. By combining a clear diagram with a verbal explanation, we give the brain two ways to find the information later. If the visual pathway is a bit weak, the verbal one can pick up the slack. This is not about "learning styles" but about providing the brain with the richest possible set of cues. It is like building two bridges over a river instead of one.

Finally, formative feedback is the "GPS" for neuroplasticity. If a student is building a new neural pathway, they need to know if they are going in the right direction. Constant, small corrections prevent the "wiring in" of misconceptions. Once a mistake is "hardwired" through repeated practise, it is much harder to fix. Early and frequent feedback ensures that the plasticity we are triggering is accurate and useful.

Does neuroplasticity mean that anyone can be a genius?

No. While everyone's brain is plastic, we all start with different genetic baselines and predispositions. Neuroplasticity means that everyone can improve significantly from their starting point, but it does not guarantee an identical outcome for everyone. It shifts the focus from "innate ability" to "achievable progress."

How long does it take for a neural pathway to become "permanent"?

There is no single answer, as it depends on the complexity of the task and the intensity of the practise. However, research suggests it takes weeks of consistent practise to move from a temporary chemical change to a permanent structural change. This is why "cramming" for an exam rarely leads to long-term knowledge.

Can you have "too much" neuroplasticity?

In some rare clinical cases, yes. Excessive plasticity can be linked to conditions like chronic pain or phantom limb syndrome, where the brain becomes "too good" at sending pain signals. In an educational context, however, the goal is to channel plasticity into useful academic and social skills.

Is neuroplasticity the same as "brain training"?

Not exactly. "Brain training" often refers to generic games or puzzles that claim to improve IQ. Most research shows these have little "transfer" to real-world tasks. The most effective "brain training" is the specific learning of a difficult subject, such as physics, history, or a musical instrument.

Does technology use affect neuroplasticity?

Yes. Everything we do affects the brain's structure. Constant multitasking or "doom-scrolling" can strengthen the pathways related to rapid, shallow attention and weaken those related to deep, focused concentration. This is why it is important to balance digital use with periods of deep, uninterrupted work.

Can older teachers still benefit from neuroplasticity?

Absolutely. While the rate of plasticity slows down slightly with age, the adult brain remains remarkably adaptable. Learning new teaching methods or technologies actually helps keep the brain healthy. The "plasticity" we encourage in our students is the same process that keeps our own minds sharp.

Start your next lesson with a three-minute "brain dump. " Ask your students to write down everything they can remember from the previous lesson without looking at their notes. This simple act of retrieval practise provides the biological signal their brains need to start building permanent neural pathways. Do not worry about marking these; the value is in the effort of the retrieval itself.

For decades, many educators operated under the assumption that the brain was a fixed vessel. We believed that once a child reached a certain age, their cognitive potential was largely determined. Modern neuroscience has proven this view entirely incorrect. The brain is not a static machine but a dynamic, living organ that physically changes in response to every lesson, interaction, and challenge.

Understanding neuroplasticity allows teachers to move beyond the frustration of "stuck" students. It provides the biological evidence that every learner possesses the capacity for structural change. This article examines how these changes occur and what they mean for daily classroom practise. We will strip away the hype to focus on the hard science that helps students build stronger, more resilient neural networks.

* Neural pathways are physically forged through effort: Learning is a biological process of building and strengthening synaptic connections rather than just acquiring information.

* The brain remains plastic throughout life: While "sensitive periods" exist for certain skills, the adult brain retains a remarkable ability to reorganise itself and learn new complex tasks.

* Retrieval practise is the primary driver of structural change: Actively pulling information from memory strengthens the neural "roads" that make future recall faster and more reliable.

* Sleep and physical health are non-negotiable for plasticity: Biological factors like rest and exercise release the proteins necessary for new synapses to stabilise.

* Neuromyths hinder effective teaching: Concepts like "learning styles" ignore how the brain actually processes information and can limit a student's perceived potential.

* Neuroplasticity provides the "why" for growth mindset: When students understand that their brains can physically grow, they often show higher levels of persistence and resilience.

* Classroom strategies must align with cognitive load: Plasticity occurs most efficiently when tasks are challenging enough to trigger change but not so difficult that they overwhelm working memory.

Neuroplasticity refers to the brain's ability to modify its own structure and function based on experience. It is the physical manifestation of learning. When a student masters a new mathematical concept or learns a second language, their brain is physically different than it was before the lesson. This change happens at several levels, from individual molecules at the synapse to large scale remapping of the cerebral cortex.

Historically, scientists believed the brain was "hardwired" after early childhood. This rigid view suggested that if a child did not master a skill during a specific window, the opportunity was lost forever. Michael Merzenich, one of the pioneers of plasticity research, challenged this dogma. His work demonstrated that the brain remains "plastic" and adaptable well into old age. He showed that with the right kind of intensive training, the brain can rewrite its own maps.

In the classroom, neuroplasticity means that intelligence is not a fixed trait. It is more like a muscle that develops through targeted use. This does not mean that every student starts from the same point or that learning is effortless. It does mean that the ceiling for what a student can achieve is far higher than we previously thought. For a sceptical teacher, this is not just "positive thinking" but a biological fact.

The process is often described as "neurons that fire together, wire together." This phrase, attributed to Donald Hebb, simplifies a complex biological reality. When two neurons communicate frequently, the connection between them becomes more efficient. This efficiency is what allows a student to move from slow, effortful decoding of words to fluent, automatic reading. The "wiring" is the physical evidence of hours of classroom work.

To understand how a student's brain changes, we must look at the synapse. This is the tiny gap where two neurons communicate. Learning involves a process called Long-Term Potentiation (LTP). When a student repeats a task or recalls information, the sending neuron releases more neurotransmitters and the receiving neuron becomes more sensitive. This makes the signal stronger and easier to trigger in the future.

This is not just a chemical change. It is a structural one. New synaptic "buds" can grow, and existing connections can be coated in a fatty substance called myelin. Myelin acts like insulation on an electrical wire. It can speed up neural signals by up to a hundred times. This is why a Year 11 student can solve an algebra problem in seconds that would have taken them ten minutes in Year 7. Their pathways are better insulated.

Synaptic pruning is the equally important opposite of this process. The brain is an energy-intensive organ and cannot keep every connection it ever makes. If a pathway is not used, the brain eventually "prunes" it away to save resources. This explains why students forget content over the summer holidays if they do not revisit it. Pruning ensures the brain remains efficient by focusing on the pathways that are used most frequently.

Norman Doidge, in his work on the brain's adaptability, describes this as "competitive plasticity." The different areas of the brain are constantly competing for space. If a student spends hours practising the piano, the area of the brain responsible for finger movement will physically expand into neighbouring territory. Conversely, if a student stops reading, the literacy pathways will begin to shrink. The classroom is a constant battleground for neural real estate.

The concept of "critical periods" has often been misinterpreted by educators. It is true that there are "sensitive periods" where the brain is exceptionally primed for certain types of learning. Language acquisition is a classic example. Children who learn a second language before age seven typically achieve native-like fluency because their brains are in a state of hyper-plasticity for phonemes and syntax.

However, the "window" does not slam shut. While it may be more difficult to learn a language as an adult, neuroplasticity ensures it is still possible. The adult brain uses different mechanisms to achieve the same result. Instead of the effortless "absorption" seen in toddlers, adults rely on conscious attention and deliberate strategies. Teachers should avoid telling students it is "too late" to learn a skill. The brain remains capable of change as long as it is challenged.

In a primary setting, teachers see the peak of this sensitive period. Children's brains are creating trillions of synapses, many of which will later be pruned. This is why early intervention is so critical. If a child has a hearing difficulty or a vision problem during these years, the brain may remap itself in ways that are hard to undo later. The biological stakes are high in the early years, but they remain significant throughout secondary education.

For secondary teachers, the focus shifts to the "second window" of plasticity during adolescence. The teenage brain undergoes a massive structural overhaul, particularly in the prefrontal cortex. This area is responsible for planning, impulse control, and metacognition. While this period is often associated with risk-taking, it is also a time of profound cognitive growth. Adolescents are biologically primed to develop high-level reasoning skills if the curriculum provides the right stimulus.

Carol Dweck's work on growth mindset is often cited alongside neuroplasticity. The two concepts are related but distinct. Neuroplasticity is the physical mechanism, while growth mindset is the psychological belief in that mechanism. A student who believes their intelligence can grow is more likely to engage in the hard work that actually triggers neural change. Without the effort, the plasticity does not happen.

A common "false growth mindset" occurs when teachers praise effort alone. Simply trying hard does not change the brain if the student is using an ineffective strategy. Dweck has clarified that growth mindset must involve trying new strategies and seeking help when stuck. Neuroplasticity requires "deliberate practise," a concept championed by K. Anders Ericsson. This involves working at the edge of one's capability, which is where the most significant neural changes occur.

Teachers must be careful not to present neuroplasticity as a magical solution. It is a slow, physically demanding process. If a student is told their brain can grow but they do not see immediate results, they may become more discouraged. We should frame plasticity as a "long game." It is the result of consistent, daily habits rather than a sudden "aha" moment. The biology supports the effort, but it does not replace it.

Another caveat is that some cognitive traits have a stronger genetic component than others. While everyone's brain is plastic, the rate and ease of change can vary. This is why some students require five repetitions to master a concept while others need fifty. Acknowledging this reality helps teachers avoid the trap of "toxic positivity." We celebrate that everyone can improve, while respecting that the process looks different for every individual.

Retrieval practise is perhaps the most powerful tool for driving neuroplasticity in the classroom. When a student takes a low-stakes quiz or tries to explain a concept from memory, they are not just "checking" what they know. They are physically strengthening the neural pathway associated with that information. This is why being tested on material is far more effective for long-term retention than simply re-reading it.

Barak Rosenshine's Principles of Instruction align perfectly with these neural mechanics. His emphasis on daily and weekly review ensures that pathways are revisited before they can be pruned. Each time a student retrieves a memory, that memory becomes more "stable" and easier to access. In neurological terms, the connections are becoming more efficient and the myelin sheath is thickening. This is the biological basis of fluency.

Consider the difference between a student who reads their notes ten times and a student who reads them once and then tests themselves nine times. The first student is creating a "familiarity" that feels like learning but is actually shallow. The second student is forcing their brain to reconstruct the information. This reconstruction is what triggers the release of the chemicals needed for synaptic growth. Effortful retrieval is the signal the brain needs to prioritise that specific information.

In the classroom, this means we should prioritise "active recall" over passive consumption. Instead of showing a video and hoping it sticks, we should pause every five minutes and ask students to write down three key facts. These small, frequent "test" events act as biological signals. They tell the brain: "This information is important; build a permanent road to it." Over time, these small roads become motorways of knowledge.

Neuroplasticity does not happen in a vacuum. It requires a specific biological environment. One of the most critical factors is Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF). This protein acts like "fertiliser" for the brain. It encourages the growth of new neurons and protects existing ones. Research shows that physical exercise is one of the most effective ways to increase BDNF levels. A short burst of activity before a challenging lesson can literally prime the brain for change.

Sleep is equally essential. Most of the structural changes triggered during the school day actually occur while the student is asleep. During deep sleep, the brain "replays" the neural patterns formed during the day, a process called consolidation. This is when the chemical changes at the synapse are converted into permanent structural changes. A student who stays up late gaming is not just tired the next day; they are actively sabotaging the learning they did the day before.

For busy teachers, this suggests that "wellbeing" is not a separate topic from "attainment." If a student is chronically sleep-deprived, no amount of high-quality instruction will result in significant plasticity. The brain simply lacks the biological resources to build new connections. Educating students about the "biology of learning" can be a powerful motivator. When they understand that sleep is when their "brain grows," they may take their bedtime more seriously.

Nutrition also plays a supporting role. The brain uses about twenty per cent of the body's total energy. It requires a steady supply of glucose and specific fatty acids to build myelin and maintain cell membranes. While teachers cannot control what students eat at home, they can advocate for healthy school meals and encourage students to stay hydrated. A hungry brain is a rigid brain, focused on survival rather than structural expansion.

Neuroplasticity offers a hopeful framework for supporting neurodivergent students. In the past, conditions like dyslexia or ADHD were seen as permanent "deficits." We now understand that these brains are simply wired differently. While certain pathways may be less efficient, neuroplasticity allows the brain to build "workarounds." This is the core of many successful interventions for learning difficulties.

In students with dyslexia, for example, the pathways connecting the visual and auditory parts of the brain are often weaker. Targeted, intensive phonics instruction can physically strengthen these connections. In some cases, the brain can even learn to use different areas in the right hemisphere to compensate for weaknesses in the left. This remapping is a direct result of the brain's plastic nature. It takes more effort and time, but the physical change is possible.

For students with ADHD, the challenge often lies in the pathways related to dopamine and executive function. Neuroplasticity suggests that these "attention muscles" can be trained. Techniques like mindfulness or structured planning routines can, over time, strengthen the prefrontal cortex. The goal is not to "cure" neurodivergence but to help the student build the most efficient neural version of themselves. This shifts the focus from "what is wrong with the student" to "how can we help this brain adapt."

Teachers should be aware that neuroplasticity can also work against a student. If a child with autism is repeatedly exposed to overwhelming sensory environments, their brain may become "hyper-plastic" in its stress response. They are literally becoming better at being stressed. This is why a calm, predictable classroom environment is so important. We want the brain to be plastic in its learning pathways, not in its anxiety circuits.

The popularity of "brain-based learning" has unfortunately led to the spread of several neuromyths. These are oversimplified or misunderstood scientific concepts that have no evidence base. One of the most persistent is "learning styles." The idea that some students are "visual" and others are "auditory" is entirely unsupported by neuroscience. The brain is highly interconnected; we process information using multiple senses simultaneously.

Believing in learning styles can actually limit neuroplasticity. If a student thinks they "can't do" auditory tasks, they may avoid the very activities that would strengthen those neural pathways. They become trapped in a self-fulfilling prophecy of limited growth. Effective teaching involves "dual coding," where we present information in both visual and verbal forms. This creates multiple neural pathways to the same concept, making it more likely to stick.

Another common myth is that we only use ten per cent of our brains. This is completely false. Imaging technology shows that almost every part of the brain is active over a twenty-four-hour period. Even during sleep, the brain is busy consolidating memories and cleaning out toxins. The "ten per cent" myth is often used to sell expensive "brain training" programmes that have little impact on classroom performance. The best brain training is a rigorous, well-designed curriculum.

The "left-brain vs right-brain" distinction is also a gross oversimplification. While some functions are lateralised, the two halves of the brain are in constant communication through a massive bridge called the corpus callosum. There is no such thing as a "purely creative" right-brain student or a "purely logical" left-brain student. Every complex task, from writing a poem to solving an equation, requires the whole brain to work in harmony.

| Claim / Concept | Scientific Status | Evidence Summary |

| :--- | :--- | :--- |

| Neuroplasticity | Fact | Extensive evidence from MRI and cellular biology shows the brain changes structure based on experience. |

| Learning Styles | Myth | Multiple large-scale reviews find no evidence that teaching to a "style" improves learning outcomes. |

| Retrieval Practise | Fact | Strong evidence shows that active recall strengthens neural pathways more effectively than re-reading. |

| 10% Brain Usage | Myth | Brain scans show all areas of the brain are active throughout the day, even during rest. |

| Critical Periods | Nuance | "Sensitive periods" exist for early skills, but the brain remains plastic and capable of learning throughout life. |

| Left vs Right Brain | Myth | While some functions are lateralised, all complex tasks require both hemispheres to work together. |

| BDNF and Exercise | Fact | Physical activity is proven to increase the proteins that support synaptic growth and neural health. |

| Brain Gym | Myth | No credible scientific evidence supports the claim that specific body movements can "switch on" parts of the brain. |

To harness neuroplasticity, we must move beyond the "one-off" lesson. Since plasticity is a structural change, it requires repetition and time. Spacing is a vital strategy here. Instead of teaching a topic in a single block, we should "space" the practise out over days, weeks, and months. This forces the brain to repeatedly reconstruct the pathway, which is the signal it needs to make the change permanent.

Interleaving is another powerful technique. This involves mixing up different types of problems or topics within a single practise session. For example, in a maths lesson, instead of doing twenty identical "long division" problems, students should do a mix of addition, division, and fractions. This is harder for the student and feels slower, but it leads to better long-term retention. Neurologically, it forces the brain to "choose" the right pathway each time, strengthening the decision-making circuits.

Dual coding helps build "redundant" pathways. By combining a clear diagram with a verbal explanation, we give the brain two ways to find the information later. If the visual pathway is a bit weak, the verbal one can pick up the slack. This is not about "learning styles" but about providing the brain with the richest possible set of cues. It is like building two bridges over a river instead of one.

Finally, formative feedback is the "GPS" for neuroplasticity. If a student is building a new neural pathway, they need to know if they are going in the right direction. Constant, small corrections prevent the "wiring in" of misconceptions. Once a mistake is "hardwired" through repeated practise, it is much harder to fix. Early and frequent feedback ensures that the plasticity we are triggering is accurate and useful.

Does neuroplasticity mean that anyone can be a genius?

No. While everyone's brain is plastic, we all start with different genetic baselines and predispositions. Neuroplasticity means that everyone can improve significantly from their starting point, but it does not guarantee an identical outcome for everyone. It shifts the focus from "innate ability" to "achievable progress."

How long does it take for a neural pathway to become "permanent"?

There is no single answer, as it depends on the complexity of the task and the intensity of the practise. However, research suggests it takes weeks of consistent practise to move from a temporary chemical change to a permanent structural change. This is why "cramming" for an exam rarely leads to long-term knowledge.

Can you have "too much" neuroplasticity?

In some rare clinical cases, yes. Excessive plasticity can be linked to conditions like chronic pain or phantom limb syndrome, where the brain becomes "too good" at sending pain signals. In an educational context, however, the goal is to channel plasticity into useful academic and social skills.

Is neuroplasticity the same as "brain training"?

Not exactly. "Brain training" often refers to generic games or puzzles that claim to improve IQ. Most research shows these have little "transfer" to real-world tasks. The most effective "brain training" is the specific learning of a difficult subject, such as physics, history, or a musical instrument.

Does technology use affect neuroplasticity?

Yes. Everything we do affects the brain's structure. Constant multitasking or "doom-scrolling" can strengthen the pathways related to rapid, shallow attention and weaken those related to deep, focused concentration. This is why it is important to balance digital use with periods of deep, uninterrupted work.

Can older teachers still benefit from neuroplasticity?

Absolutely. While the rate of plasticity slows down slightly with age, the adult brain remains remarkably adaptable. Learning new teaching methods or technologies actually helps keep the brain healthy. The "plasticity" we encourage in our students is the same process that keeps our own minds sharp.

Start your next lesson with a three-minute "brain dump. " Ask your students to write down everything they can remember from the previous lesson without looking at their notes. This simple act of retrieval practise provides the biological signal their brains need to start building permanent neural pathways. Do not worry about marking these; the value is in the effort of the retrieval itself.

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/neuroplasticity-education-teachers-need-know#article","headline":"Neuroplasticity in Education: What Teachers Need to Know About the Learning Brain","description":"Learn about Neuroplasticity in Education: What Teachers Need to Know About the Learning Brain. A comprehensive guide for teachers.","datePublished":"2026-02-17T10:41:33.067Z","dateModified":"2026-02-17T13:57:35.075Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/neuroplasticity-education-teachers-need-know"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/699445dc4d3eaf652adb8ba3_69944565ab9ffb241250efb8_neuroplasticity-in-education-w-comparison-1771324772937.webp","wordCount":3561},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/neuroplasticity-education-teachers-need-know#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"Neuroplasticity in Education: What Teachers Need to Know About the Learning Brain","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/neuroplasticity-education-teachers-need-know"}]}]}