The Testing Effect: How Retrieval Practice Strengthens Learning

Discover how the testing effect transforms learning by using quizzes as powerful learning tools rather than assessments, with proven strategies for every subject.

Discover how the testing effect transforms learning by using quizzes as powerful learning tools rather than assessments, with proven strategies for every subject.

You've just taught a brilliant lesson. Students nodded along, answered questions, and seemed to grasp the material. Yet three weeks later, during the assessment, blank faces stare back at you. What went wrong? The answer lies partly in the Ebbinghaus Forgetting Curve - our natural tendency to forget information rapidly without reinforcement.

The testing effect demonstrates that actively retrieving information from memory strengthens learning more effectively than passive review methods like re-reading or highlighting.

Implementation note: While the evidence for retrieval practise is strong, the Education Endowment Foundation notes a distinction between laboratory studies and classroom implementation. Most school-based studies use researcher-designed questions often identical to the final test, whereas real-world teacher implementation may show different results. The Donoghue & Hattie (2021) meta-analysis found that feedback is an important moderator of effect sizes.

For practical resources, see the Chartered College of Teaching retrieval practise guidance and The Learning Scientists.

Jumping straight into retrieval practise without proper preparation is like teaching a lesson without planning; it rarely ends well. The difference between successful implementation and another failed initiative often lies in how thoughtfully you establish the foundations.

Start by auditing your current assessment practices. How often do students actively recall information versus passively reviewing it? Track a typical week in your classroom: count instances of genuine retrieval (closed-book questions, brain dumps, practise tests) against passive activities (re-reading, highlighting, copying notes). Most teachers discover they're doing far less retrieval practise than they thought.

Next, establish clear routines that make retrieval practise predictable rather than threatening. Begin each lesson with a five-minute "knowledge check" using whiteboards or quick-fire questions from previous topics. This transforms testing from a high-stakes event into a regular learning tool. Year 7 maths teacher Sarah Mills starts every lesson with three questions: one from yesterday, one from last week, and one from last term. Her students now expect it, prepare for it, and actually request more practise questions.

Consider your feedback systems before implementing retrieval practise. Without timely correction, students might reinforce incorrect information through repeated retrieval. Simple solutions work best: self-marking with answer keys, paired checking, or whole-class review immediately after retrieval activities. The key is ensuring students know what they got right or wrong within the same lesson.

Finally, communicate the purpose clearly to students. Explain that these aren't tests to catch them out, but tools to strengthen their memory. Show them the research; students often become more engaged when they understand the science behind what you're asking themto do.

| Technique | How It Works | Effectiveness | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Free Recall | Students write everything they remember without prompts or cues | ★★★★★ Highest | Building strong memory traces; identifying knowledge gaps; deepest encoding |

| Cued Recall | Prompts or partial information trigger retrieval (e.g., fill-in-blanks) | ★★★★☆ High | Supporting struggling learners; vocabulary; definitions; scaffolded practice |

| Short-Answer Questions | Open-ended questions requiring generated responses | ★★★★☆ High | Factual knowledge; conceptual understanding; quick formative assessment |

| Multiple Choice | Recognition from options (must be well-designed with plausible distractors) | ★★★☆☆ Moderate | Large classes; quick checks; diagnostic testing; exam preparation |

| Elaborative Retrieval | Recall plus explanation of why/how (connecting to prior knowledge) | ★★★★★ Highest | Deep understanding; transfer; complex concepts; higher-order thinking |

| Concept Mapping from Memory | Creating visual representations of knowledge without notes | ★★★★☆ High | Relationships between ideas; schema building; revision summaries |

| Teach-Back | Students explain content to peers as if teaching | ★★★★★ Highest | Identifying misconceptions; consolidation; social learning; metacognition |

Based on research by Roediger & Butler (2011), Karpicke & Blunt (2011), and Rowland (2014). The testing effect works because retrieval strengthens memory traces more than re-reading, highlighting, or passive review.

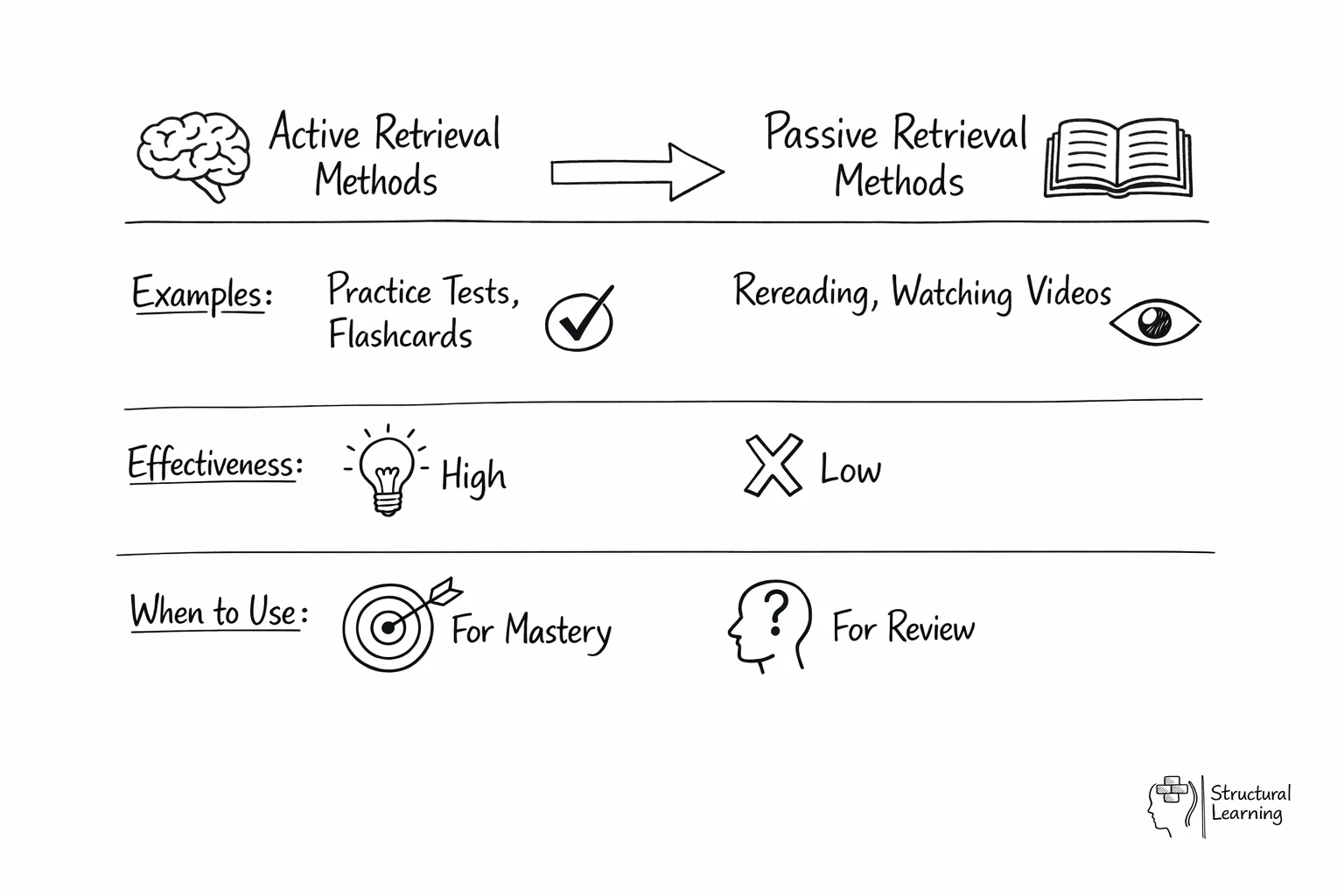

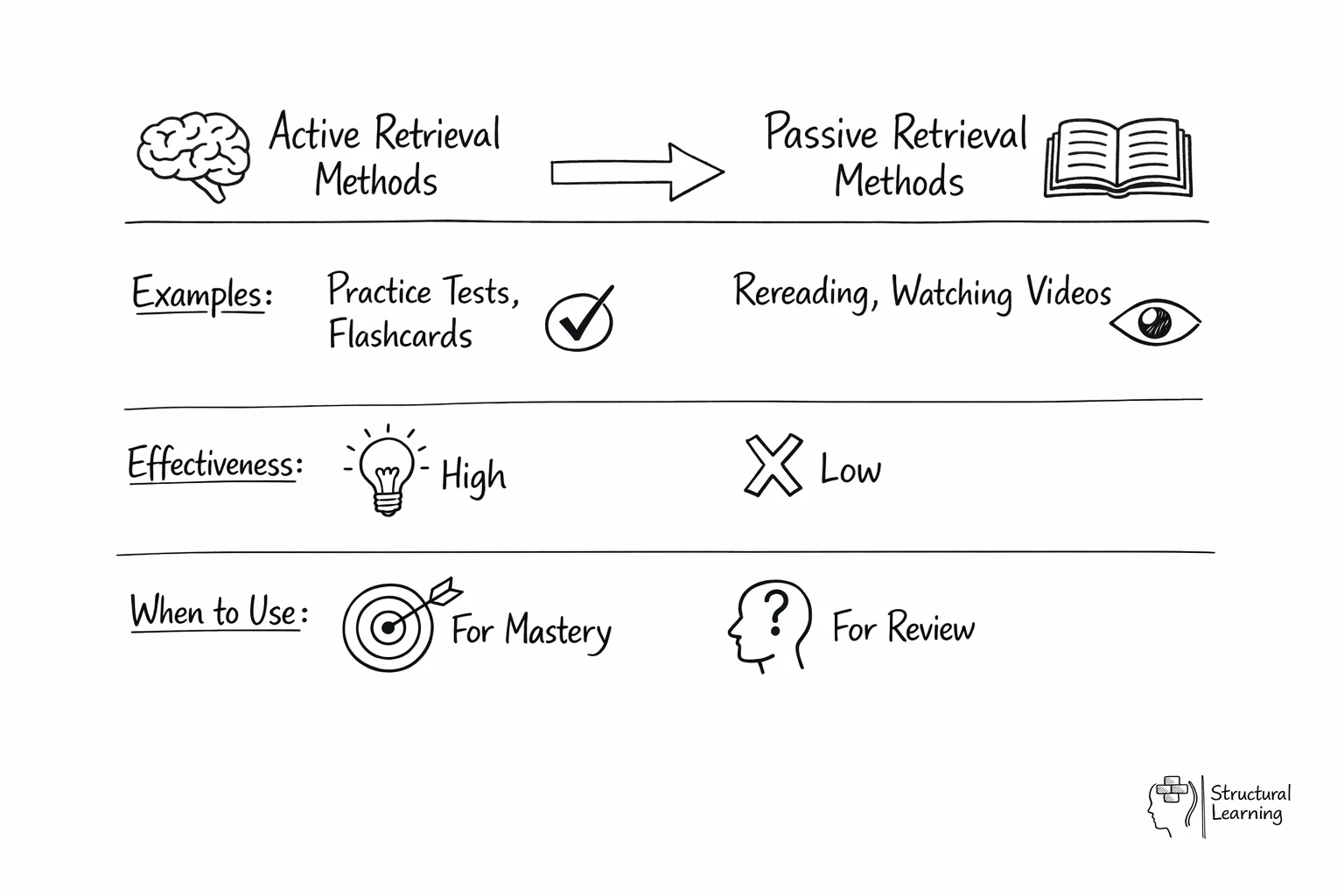

Not all retrieval practise is created equal. Understanding the distinction between active and passive methods can transform how you implement testing in your classroom, moving beyond simple recall to deeper, more durable learning.

retrieval practice methods with examples and usage guidance" loading="lazy">

retrieval practice methods with examples and usage guidance" loading="lazy">Active retrieval methods require students to generate information from memory without visible cues. Think of a Year 9 student writing everything they remember about photosynthesis on a blank sheet, or primary pupils using mini whiteboards to answer multiplication questions from memory. These methods force the brain to work harder, creating stronger memory pathways. Research by Karpicke and Blunt (2011) found that students who practised active retrieval retained 50% more information after one week compared to those who simply reviewed their notes.

Passive retrieval methods, whilst still valuable, provide more scaffolding. Multiple-choice questions, matching exercises, or cloze activities where students fill in missing words all fall into this category. These methods still engage retrieval processes but offer recognition cues that reduce cognitive load. For instance, when teaching Shakespeare, you might start with multiple-choice questions about character motivations before progressing to open-ended essay questions.

The key is progression. Begin with passive methods to build confidence, particularly with struggling learners or new content. A Year 7 French class might start with matching vocabulary to images, then progress to writing sentences from memory. Similarly, GCSE science revision could move from multiple-choice questions about chemical equations to writing balanced equations without prompts.

Consider mixing methods within a single lesson. Start with a quick multiple-choice warm-up, follow with paired verbal explanations (active), then finish with students creating their own test questions. This variety maintains engagement whilst gradually increasing challenge, ensuring all learners can access the benefits of..

Making retrieval practise work in your classroom doesn't require a complete overhaul of your teaching methods. Here's a straightforward approach to get started:

Step 1: Start small with exit tickets. In the final five minutes of each lesson, ask students to write down three key points from memory without looking at their notes. This simple activity activates retrieval whilst the material is still fresh. For example, after a Year 9 history lesson on the Industrial Revolution, students might recall three changes to working conditions.

Step 2: Build in regular low-stakes quizzing. Begin each lesson with five quick-fire questions about previous topics. Keep these informal; use mini whiteboards or verbal responses to reduce anxiety. A maths teacher might start Monday's lesson asking students to solve problems from last Wednesday's work on algebraic expressions.

Step 3: Space your practise intervals. Rather than testing content immediately, wait a day, then a week, then a fortnight. This spacing forces effortful retrieval, which strengthens memory pathways. Research by Cepeda et al. (2006) suggests optimal spacing intervals depend on how long you need students to remember the material.

Step 4: Provide immediate, specific feedback. When students retrieve incorrectly, address misconceptions straight away. Instead of simply marking answers wrong, explain why and provide the correct information. This combination of retrieval plus feedback creates what Roediger and Butler (2011) call "test-enhanced learning."

Step 5: Track and adjust. Keep notes on which topics need more retrieval practise. If students consistently struggle with certain concepts, increase the frequency of retrieval opportunities for those areas whilst maintaining spaced practise for mastered content.

These evidence-based retrieval practice activities harness the testing effect to strengthen student memory and understanding. Regular, low-stakes retrieval practice is one of the most powerful learning strategies available - transforming classrooms from places where information is delivered to places where knowledge is actively constructed and retained.

The testing effect is one of the most robust findings in cognitive psychology - retrieval practice consistently outperforms re-reading, re-studying, and highlighting by substantial margins. The key is making retrieval regular, low-stakes, and spaced over time. Start with one technique, embed it into your routine, then gradually expand your retrieval practice toolkit. Students may initially resist because retrieval feels harder than passive study, but the dramatic improvements in retention quickly demonstrate its value.

For primary students, keep retrieval practise sessions short and focused, typically 5-10 minutes maximum. Young children have limited attention spans, so brief, frequent sessions work better than longer testing periods. Aim for little and often rather than lengthy retrieval activities that might overwhelm or discourage learners.

Provide immediate, specific feedback that explains why answers are correct or incorrect rather than just marking them right or wrong. Focus on the thinking process behind the answer and guide students towards the correct response when they struggle. This transforms mistakes into learning opportunities rather than just highlighting gaps in knowledge.

Frame retrieval practise as brain training rather than testing, emphasising that struggle and mistakes are signs of learning happening. Start with low-stakes activities and celebrate effort over accuracy initially. Once students experience the confidence boost from improved recall, they typically become more willing participants in the process.

No, vary your retrieval practise questions to include different formats and difficulty levels whilst covering the same core concepts. This builds flexible understanding rather than rote memorisation of specific question types. Mix direct recall questions with application problems to strengthen both basic knowledge and deeper understanding.

Replace some passive review time with active retrieval rather than adding extra content to your lessons. Use transition moments like the start of lessons, after breaks, or while waiting for late arrivals to squeeze in quick retrieval activities. Even 2-3 minutes of focused recall can be more effective than longer periods of passive note-taking.

These peer-reviewed studies provide the research foundation for the strategies discussed in this article:

Hattie's Visible Learning Evaluation Model in Learning Strategies and Publication of Scientific Work of IKIP Siliwangi Students View study ↗

1 citations

Suhud Suhud (2024)

This study applied John Hattie's influential research on effective teaching practices to evaluate learning strategies at an Indonesian teacher training institute. By analysing student responses across sixty different aspects of learning, researchers identified which teaching approaches worked best for different programmes. The findings offer educators concrete examples of how to systematically evaluate and improve their own teaching methods using evidence-based frameworks.

DISFLUENCY IN ENGLISH LANGUAGE TEACHING? View study ↗

1 citations

Laura Buechel (2020)

This research explored whether making learning slightly more difficult on purpose, including using a harder-to-read font called Sans Forgetica, can actually improve student learning in English language classrooms. The study with Swiss preservice teachers demonstrates how introducing productive challenges like spacing out lessons and mixing up topics can strengthen long-term retention. Teachers can apply these 'desirable difficulties' to help students build more durable knowledge rather than relying on methods that feel easy but fade quickly.

True-false tests enhance retention relative to rereading. View study ↗

9 citations

Oyku Uner et al. (2021)

College students who reviewed material using true-false questions remembered significantly more information two days later compared to students who simply reread the same content. This research validates what many teachers instinctively know: even simple quizzing formats are more powerful for learning than passive review methods. The findings encourage educators to replace some rereading and highlighting activities with quick true-false checks to boost student retention.

A case study of the use of the Hattie and Timperley feedback model on written feedback in thesis examination in higher education View study ↗

9 citations

Ivonne Lipsch-Wijnen & K. Dirkx (2022)

Researchers analysed how effectively the widely-used Hattie and Timperley feedback framework actually works in practise by examining written comments on student theses. The study reveals practical insights about which types of feedback comments most effectively guide student improvement and learning. This research helps teachers move beyond generic praise or criticism to provide more targeted, actionable feedback that genuinely advances student understanding.

A spaced-repetition approach to enhance medical student learning and engagement in medical pharmacology View study ↗

41 citations

Dylan Jape et al. (2022)

Medical students using spaced-repetition techniques showed dramatically improved retention and confidence when learning complex pharmacology concepts compared to traditional study methods. The research demonstrates how strategically timing review sessions, with increasing intervals between practise, helps students master and retain difficult material long-term. These findings offer any educator teaching challenging subjects a proven method to help students build lasting expertise rather than cramming for short-term recall.

You've just taught a brilliant lesson. Students nodded along, answered questions, and seemed to grasp the material. Yet three weeks later, during the assessment, blank faces stare back at you. What went wrong? The answer lies partly in the Ebbinghaus Forgetting Curve - our natural tendency to forget information rapidly without reinforcement.

The testing effect demonstrates that actively retrieving information from memory strengthens learning more effectively than passive review methods like re-reading or highlighting.

Implementation note: While the evidence for retrieval practise is strong, the Education Endowment Foundation notes a distinction between laboratory studies and classroom implementation. Most school-based studies use researcher-designed questions often identical to the final test, whereas real-world teacher implementation may show different results. The Donoghue & Hattie (2021) meta-analysis found that feedback is an important moderator of effect sizes.

For practical resources, see the Chartered College of Teaching retrieval practise guidance and The Learning Scientists.

Jumping straight into retrieval practise without proper preparation is like teaching a lesson without planning; it rarely ends well. The difference between successful implementation and another failed initiative often lies in how thoughtfully you establish the foundations.

Start by auditing your current assessment practices. How often do students actively recall information versus passively reviewing it? Track a typical week in your classroom: count instances of genuine retrieval (closed-book questions, brain dumps, practise tests) against passive activities (re-reading, highlighting, copying notes). Most teachers discover they're doing far less retrieval practise than they thought.

Next, establish clear routines that make retrieval practise predictable rather than threatening. Begin each lesson with a five-minute "knowledge check" using whiteboards or quick-fire questions from previous topics. This transforms testing from a high-stakes event into a regular learning tool. Year 7 maths teacher Sarah Mills starts every lesson with three questions: one from yesterday, one from last week, and one from last term. Her students now expect it, prepare for it, and actually request more practise questions.

Consider your feedback systems before implementing retrieval practise. Without timely correction, students might reinforce incorrect information through repeated retrieval. Simple solutions work best: self-marking with answer keys, paired checking, or whole-class review immediately after retrieval activities. The key is ensuring students know what they got right or wrong within the same lesson.

Finally, communicate the purpose clearly to students. Explain that these aren't tests to catch them out, but tools to strengthen their memory. Show them the research; students often become more engaged when they understand the science behind what you're asking themto do.

| Technique | How It Works | Effectiveness | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Free Recall | Students write everything they remember without prompts or cues | ★★★★★ Highest | Building strong memory traces; identifying knowledge gaps; deepest encoding |

| Cued Recall | Prompts or partial information trigger retrieval (e.g., fill-in-blanks) | ★★★★☆ High | Supporting struggling learners; vocabulary; definitions; scaffolded practice |

| Short-Answer Questions | Open-ended questions requiring generated responses | ★★★★☆ High | Factual knowledge; conceptual understanding; quick formative assessment |

| Multiple Choice | Recognition from options (must be well-designed with plausible distractors) | ★★★☆☆ Moderate | Large classes; quick checks; diagnostic testing; exam preparation |

| Elaborative Retrieval | Recall plus explanation of why/how (connecting to prior knowledge) | ★★★★★ Highest | Deep understanding; transfer; complex concepts; higher-order thinking |

| Concept Mapping from Memory | Creating visual representations of knowledge without notes | ★★★★☆ High | Relationships between ideas; schema building; revision summaries |

| Teach-Back | Students explain content to peers as if teaching | ★★★★★ Highest | Identifying misconceptions; consolidation; social learning; metacognition |

Based on research by Roediger & Butler (2011), Karpicke & Blunt (2011), and Rowland (2014). The testing effect works because retrieval strengthens memory traces more than re-reading, highlighting, or passive review.

Not all retrieval practise is created equal. Understanding the distinction between active and passive methods can transform how you implement testing in your classroom, moving beyond simple recall to deeper, more durable learning.

retrieval practice methods with examples and usage guidance" loading="lazy">

retrieval practice methods with examples and usage guidance" loading="lazy">Active retrieval methods require students to generate information from memory without visible cues. Think of a Year 9 student writing everything they remember about photosynthesis on a blank sheet, or primary pupils using mini whiteboards to answer multiplication questions from memory. These methods force the brain to work harder, creating stronger memory pathways. Research by Karpicke and Blunt (2011) found that students who practised active retrieval retained 50% more information after one week compared to those who simply reviewed their notes.

Passive retrieval methods, whilst still valuable, provide more scaffolding. Multiple-choice questions, matching exercises, or cloze activities where students fill in missing words all fall into this category. These methods still engage retrieval processes but offer recognition cues that reduce cognitive load. For instance, when teaching Shakespeare, you might start with multiple-choice questions about character motivations before progressing to open-ended essay questions.

The key is progression. Begin with passive methods to build confidence, particularly with struggling learners or new content. A Year 7 French class might start with matching vocabulary to images, then progress to writing sentences from memory. Similarly, GCSE science revision could move from multiple-choice questions about chemical equations to writing balanced equations without prompts.

Consider mixing methods within a single lesson. Start with a quick multiple-choice warm-up, follow with paired verbal explanations (active), then finish with students creating their own test questions. This variety maintains engagement whilst gradually increasing challenge, ensuring all learners can access the benefits of..

Making retrieval practise work in your classroom doesn't require a complete overhaul of your teaching methods. Here's a straightforward approach to get started:

Step 1: Start small with exit tickets. In the final five minutes of each lesson, ask students to write down three key points from memory without looking at their notes. This simple activity activates retrieval whilst the material is still fresh. For example, after a Year 9 history lesson on the Industrial Revolution, students might recall three changes to working conditions.

Step 2: Build in regular low-stakes quizzing. Begin each lesson with five quick-fire questions about previous topics. Keep these informal; use mini whiteboards or verbal responses to reduce anxiety. A maths teacher might start Monday's lesson asking students to solve problems from last Wednesday's work on algebraic expressions.

Step 3: Space your practise intervals. Rather than testing content immediately, wait a day, then a week, then a fortnight. This spacing forces effortful retrieval, which strengthens memory pathways. Research by Cepeda et al. (2006) suggests optimal spacing intervals depend on how long you need students to remember the material.

Step 4: Provide immediate, specific feedback. When students retrieve incorrectly, address misconceptions straight away. Instead of simply marking answers wrong, explain why and provide the correct information. This combination of retrieval plus feedback creates what Roediger and Butler (2011) call "test-enhanced learning."

Step 5: Track and adjust. Keep notes on which topics need more retrieval practise. If students consistently struggle with certain concepts, increase the frequency of retrieval opportunities for those areas whilst maintaining spaced practise for mastered content.

These evidence-based retrieval practice activities harness the testing effect to strengthen student memory and understanding. Regular, low-stakes retrieval practice is one of the most powerful learning strategies available - transforming classrooms from places where information is delivered to places where knowledge is actively constructed and retained.

The testing effect is one of the most robust findings in cognitive psychology - retrieval practice consistently outperforms re-reading, re-studying, and highlighting by substantial margins. The key is making retrieval regular, low-stakes, and spaced over time. Start with one technique, embed it into your routine, then gradually expand your retrieval practice toolkit. Students may initially resist because retrieval feels harder than passive study, but the dramatic improvements in retention quickly demonstrate its value.

For primary students, keep retrieval practise sessions short and focused, typically 5-10 minutes maximum. Young children have limited attention spans, so brief, frequent sessions work better than longer testing periods. Aim for little and often rather than lengthy retrieval activities that might overwhelm or discourage learners.

Provide immediate, specific feedback that explains why answers are correct or incorrect rather than just marking them right or wrong. Focus on the thinking process behind the answer and guide students towards the correct response when they struggle. This transforms mistakes into learning opportunities rather than just highlighting gaps in knowledge.

Frame retrieval practise as brain training rather than testing, emphasising that struggle and mistakes are signs of learning happening. Start with low-stakes activities and celebrate effort over accuracy initially. Once students experience the confidence boost from improved recall, they typically become more willing participants in the process.

No, vary your retrieval practise questions to include different formats and difficulty levels whilst covering the same core concepts. This builds flexible understanding rather than rote memorisation of specific question types. Mix direct recall questions with application problems to strengthen both basic knowledge and deeper understanding.

Replace some passive review time with active retrieval rather than adding extra content to your lessons. Use transition moments like the start of lessons, after breaks, or while waiting for late arrivals to squeeze in quick retrieval activities. Even 2-3 minutes of focused recall can be more effective than longer periods of passive note-taking.

These peer-reviewed studies provide the research foundation for the strategies discussed in this article:

Hattie's Visible Learning Evaluation Model in Learning Strategies and Publication of Scientific Work of IKIP Siliwangi Students View study ↗

1 citations

Suhud Suhud (2024)

This study applied John Hattie's influential research on effective teaching practices to evaluate learning strategies at an Indonesian teacher training institute. By analysing student responses across sixty different aspects of learning, researchers identified which teaching approaches worked best for different programmes. The findings offer educators concrete examples of how to systematically evaluate and improve their own teaching methods using evidence-based frameworks.

DISFLUENCY IN ENGLISH LANGUAGE TEACHING? View study ↗

1 citations

Laura Buechel (2020)

This research explored whether making learning slightly more difficult on purpose, including using a harder-to-read font called Sans Forgetica, can actually improve student learning in English language classrooms. The study with Swiss preservice teachers demonstrates how introducing productive challenges like spacing out lessons and mixing up topics can strengthen long-term retention. Teachers can apply these 'desirable difficulties' to help students build more durable knowledge rather than relying on methods that feel easy but fade quickly.

True-false tests enhance retention relative to rereading. View study ↗

9 citations

Oyku Uner et al. (2021)

College students who reviewed material using true-false questions remembered significantly more information two days later compared to students who simply reread the same content. This research validates what many teachers instinctively know: even simple quizzing formats are more powerful for learning than passive review methods. The findings encourage educators to replace some rereading and highlighting activities with quick true-false checks to boost student retention.

A case study of the use of the Hattie and Timperley feedback model on written feedback in thesis examination in higher education View study ↗

9 citations

Ivonne Lipsch-Wijnen & K. Dirkx (2022)

Researchers analysed how effectively the widely-used Hattie and Timperley feedback framework actually works in practise by examining written comments on student theses. The study reveals practical insights about which types of feedback comments most effectively guide student improvement and learning. This research helps teachers move beyond generic praise or criticism to provide more targeted, actionable feedback that genuinely advances student understanding.

A spaced-repetition approach to enhance medical student learning and engagement in medical pharmacology View study ↗

41 citations

Dylan Jape et al. (2022)

Medical students using spaced-repetition techniques showed dramatically improved retention and confidence when learning complex pharmacology concepts compared to traditional study methods. The research demonstrates how strategically timing review sessions, with increasing intervals between practise, helps students master and retain difficult material long-term. These findings offer any educator teaching challenging subjects a proven method to help students build lasting expertise rather than cramming for short-term recall.

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/testing-effect-retrieval-practice#article","headline":"The Testing Effect: How Retrieval Practice Strengthens Learning","description":"Discover how the testing effect transforms classroom learning by using quizzes as learning tools rather than mere assessments, with evidence-based...","datePublished":"2025-12-29T10:11:34.536Z","dateModified":"2026-01-26T10:09:32.212Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/testing-effect-retrieval-practice"},"wordCount":1892},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/testing-effect-retrieval-practice#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"The Testing Effect: How Retrieval Practice Strengthens Learning","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/testing-effect-retrieval-practice"}]},{"@type":"FAQPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/testing-effect-retrieval-practice#faq","mainEntity":[{"@type":"Question","name":"How long should retrieval practise sessions be in primary school?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"For primary students, keep retrieval practise sessions short and focused, typically 5-10 minutes maximum. Young children have limited attention spans, so brief, frequent sessions work better than longer testing periods. Aim for little and often rather than lengthy retrieval activities that might ove"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What's the best way to give feedback during retrieval practise?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Provide immediate, specific feedback that explains why answers are correct or incorrect rather than just marking them right or wrong. Focus on the thinking process behind the answer and guide students towards the correct response when they struggle. This transforms mistakes into learning opportuniti"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"How can I convince reluctant students to embrace retrieval practise?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Frame retrieval practise as brain training rather than testing, emphasising that struggle and mistakes are signs of learning happening. Start with low-stakes activities and celebrate effort over accuracy initially. Once students experience the confidence boost from improved recall, they typically be"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"Should retrieval practise questions be exactly the same as exam questions?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"No, vary your retrieval practise questions to include different formats and difficulty levels whilst covering the same core concepts. This builds flexible understanding rather than rote memorisation of specific question types. Mix direct recall questions with application problems to strengthen both "}}]}]}