Updated on

February 17, 2026

Motivation in Education: What Teachers Need to Know

|

February 17, 2026

Updated on

February 17, 2026

|

February 17, 2026

Motivation acts as the engine of the classroom. It determines how much effort a student puts into a task and how long they persist when things get difficult. Understanding the mechanics of motivation allows teachers to move beyond simple rewards and punishments. This article explores the cognitive science behind student engagement and provides practical ways to apply these theories in a UK school setting.

* Motivation is a cognitive process influenced by environment and past experiences.

* Intrinsic motivation leads to higher levels of persistence and deeper conceptual understanding.

* Extrinsic rewards can jumpstart engagement but may undermine long-term interest if used poorly.

* Students must feel a sense of competence to maintain their drive for a subject.

* Autonomy allows students to feel they have some control over their learning process.

* How students explain their failures directly impacts their willingness to try again.

* A task must be seen as both achievable and valuable for a student to engage with it.

Motivation is the internal drive that directs behaviour towards a specific goal. In an educational context, it involves the desire to learn, achieve, and master new skills. Teachers often see motivation as a fixed trait that a student either possesses or lacks. However, cognitive science shows that motivation is dynamic and can be nurtured through specific classroom conditions.

Psychologists typically divide motivation into two main categories: intrinsic and extrinsic. Intrinsic motivation comes from within the individual. A student reads a book because they find the story interesting or solve a puzzle because they enjoy the challenge. This form of motivation is highly stable and leads to the best learning outcomes.

Extrinsic motivation is driven by external factors such as grades, stickers, or the avoidance of detention. While these can be effective in the short term, they do not always lead to a genuine love for the subject. If the reward is removed, the behaviour often stops. Educators must balance these two types to ensure students remain engaged even when external incentives are not present.

The transition from extrinsic to intrinsic motivation is a goal for many teachers. This process requires a shift in how students perceive the value of their schoolwork. When a student sees the utility of a skill, they are more likely to engage with it for its own sake. Understanding the research behind these drives is the first step towards building a motivated classroom.

Several key theories provide a framework for understanding why students engage with their work. These theories offer a scientific basis for classroom strategies. By looking at the work of major psychologists, we can see the patterns that govern student behaviour.

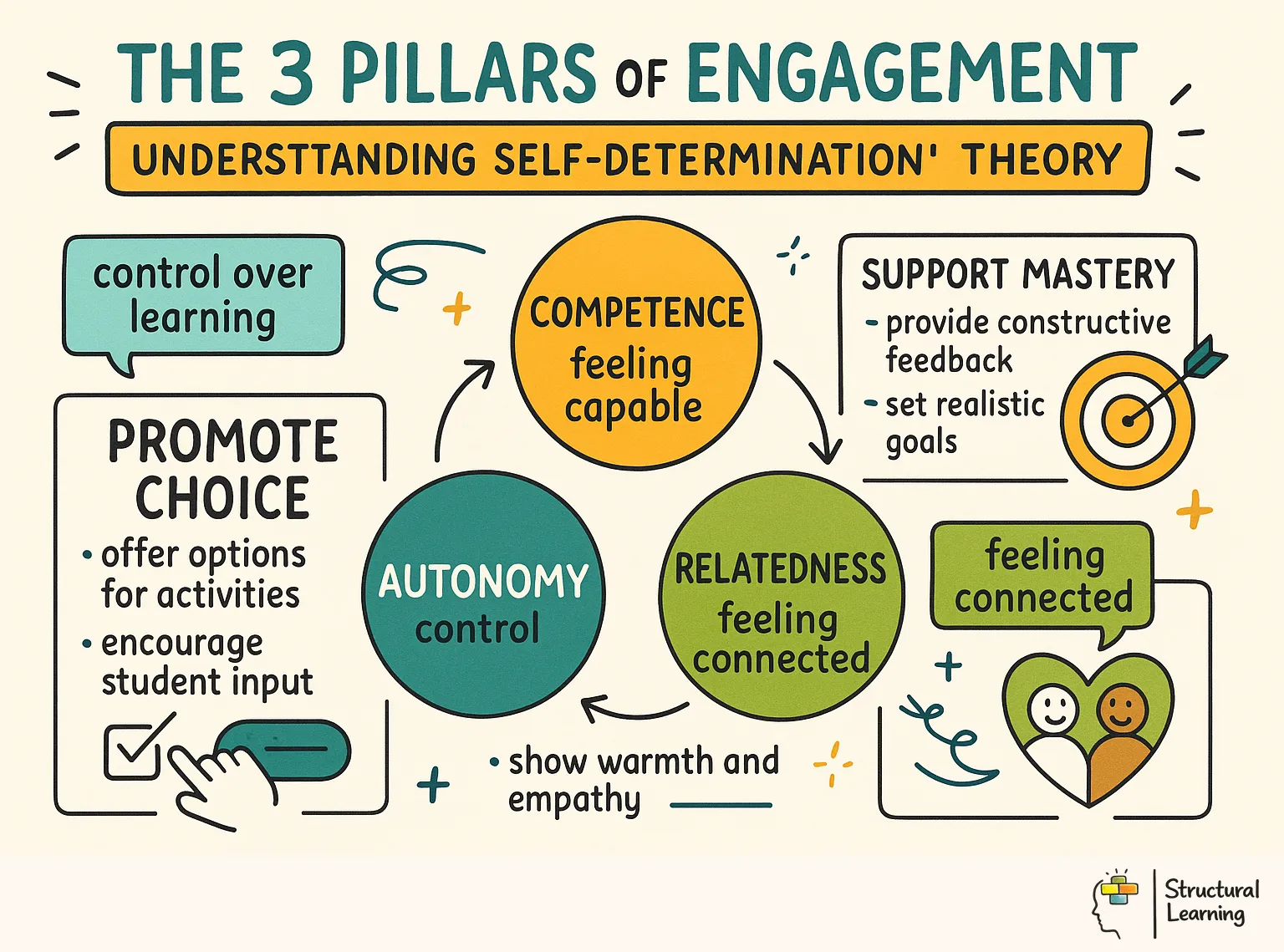

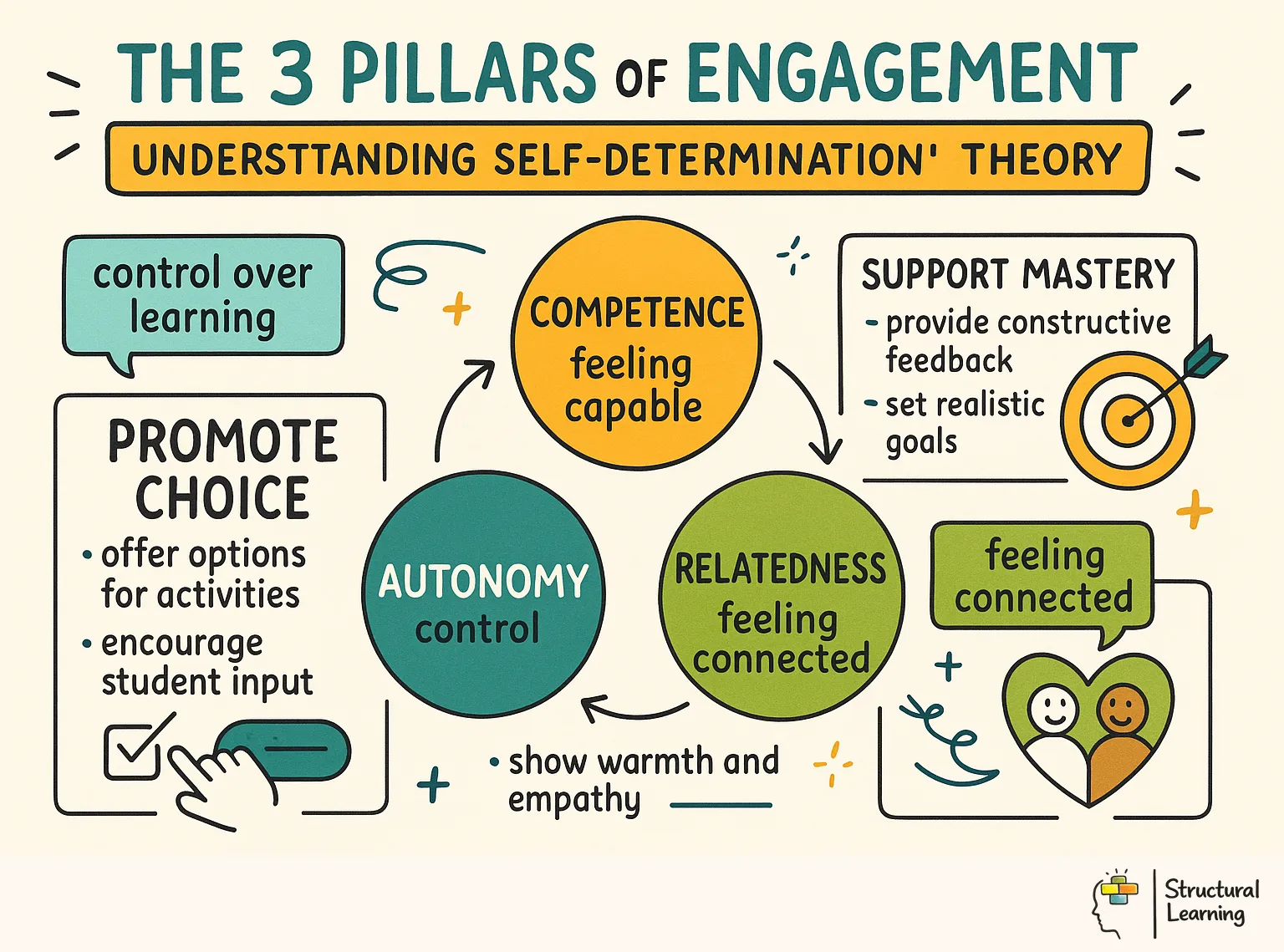

Self-Determination Theory, developed by Edward Deci and Richard Ryan, is one of the most influential models in education. It suggests that all humans have three basic psychological needs: autonomy, competence, and relatedness. When these needs are met, students show high levels of intrinsic motivation. If these needs are thwarted, motivation drops significantly.

Autonomy refers to the need to feel in control of one's actions. Students who feel forced into a task often show resentment and minimal effort. Competence is the feeling of being effective and capable in a particular area. Relatedness involves feeling connected to others and having a sense of belonging within the school community.

Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi introduced the concept of "Flow" to describe a state of total absorption in a task. When a student is in a state of flow, they lose track of time and become completely focused on what they are doing. This state occurs when there is a perfect balance between the challenge of the task and the skills of the student.

If a task is too easy, the student becomes bored. If it is too difficult, they become anxious and give up. Teachers must find the "sweet spot" where the challenge is high enough to be interesting but low enough to be manageable. Achieving flow in the classroom requires clear goals and immediate feedback.

Bernard Weiner's Attribution Theory looks at how students explain their successes and failures. These explanations, or attributions, fall into three categories: locus of causality, stability, and controllability. A student might attribute a bad grade to a lack of effort (internal, unstable, controllable) or to the difficulty of the test (external, stable, uncontrollable).

Students with high motivation tend to attribute success to their own effort and ability. They see failure as a temporary setback that can be overcome with more work. Conversely, discouraged students often believe their failures are due to a permanent lack of ability. Changing these attributions is vital for helping students regain their drive.

Jacquelynne Eccles developed the Expectancy-Value Theory to explain why students choose specific tasks. The theory suggests that motivation is the product of two factors: the expectation of success and the perceived value of the task. If a student believes they cannot succeed, they will not try, regardless of how important the task is.

Similarly, if they think they can succeed but find the task pointless, they will show little interest. Value can be defined by interest, importance, or utility. Teachers must work on both sides of this equation by building confidence and explaining why the material matters.

Applying these theories requires a shift in teaching practise. We can categorise effective strategies into four main areas: autonomy, mastery, purpose, and belonging. These areas align with the findings of cognitive science and provide a roadmap for teachers.

Autonomy does not mean letting students do whatever they want. Instead, it involves providing choices within a structured environment. You might allow students to choose which topic to research for a project or which format to use for their final presentation. This sense of choice gives students a feeling of ownership over their work.

When students have a say in their learning, they are more likely to take responsibility for the outcome. Teachers can also provide autonomy by involving students in setting classroom rules. Small choices, such as the order in which tasks are completed, can make a big difference. This approach reduces the feeling of being controlled and increases genuine engagement.

Mastery is closely linked to the concept of competence in Self-Determination Theory. Students are motivated when they can see themselves getting better at something. To support mastery, teachers should break complex tasks into smaller, manageable steps. This allows students to experience frequent small wins, which builds momentum.

Effective scaffolding is essential for mastery. Provide enough support so the student can succeed, then slowly remove that support as they become more proficient. High-quality feedback that focuses on the process rather than just the result also helps. When a student knows exactly what they did right and what to do next, their motivation remains high.

Students often ask, "Why are we learning this?" Providing a clear purpose is a powerful way to increase the perceived value of a task. Connect lesson content to real-world applications or to the students' own interests. Showing how a mathematical concept is used in engineering or how a historical event shaped the modern world can spark curiosity.

Purpose can also be internal. Help students see how mastering a particular skill will help them reach their personal goals. When learning feels relevant, the effort required seems more worthwhile. Avoid vague answers like "because it is on the exam" as these focus on extrinsic pressure rather than genuine purpose.

A student who feels isolated or unwelcome in the classroom is unlikely to be motivated. Relatedness and a sense of belonging are fundamental human needs. Build a positive classroom culture where every student feels valued and respected. Encourage collaborative work where students can support each other and share ideas.

Teacher-student relationships are a vital part of belonging. Taking an interest in a student's life outside of the subject can build trust and rapport. When students feel that their teacher cares about their progress, they are more likely to put in the effort. A safe, supportive environment allows students to take risks without the fear of being mocked.

There are several myths about motivation that can lead teachers astray. Addressing these misconceptions is essential for developing a more effective approach.

Some people believe that giving a reward for a task always destroys intrinsic interest. This is a simplification of the research. Rewards can actually increase motivation if they are used to recognise competence. For example, a certificate for mastering a difficult skill can make a student feel proud and more likely to continue.

The danger lies in using rewards as a form of control or for tasks that the student already finds interesting. If a student loves reading, giving them a sticker for every book might make them focus on the sticker rather than the story. Use rewards sparingly and focus them on effort and achievement rather than mere compliance.

The label "lazy" is often used to describe students who show little effort in class. However, this term rarely explains the underlying cause of the behaviour. What looks like laziness is often a defence mechanism against a fear of failure. If a student believes they cannot succeed, they may stop trying to protect their self-esteem.

Low motivation can also be a sign of underlying cognitive overload or a lack of prerequisite knowledge. If the work is consistently too hard, the student will eventually give up. Instead of labelling a student as lazy, look for the barriers that are preventing them from engaging. Addressing these barriers is more effective than simple reprimands.

It is common to hear teachers say that a student "just isn't motivated." This implies that motivation is a permanent trait like height or eye colour. In reality, motivation varies from day to day and from subject to subject. A student might be highly driven in PE but struggle to find any interest in History.

Because motivation is dynamic, it can be influenced by the teacher's actions and the classroom environment. By changing the way a task is presented or by providing more support, a teacher can turn a disengaged student into a motivated one. Viewing motivation as something that can be developed is a more helpful approach for both teachers and students.

To see how these theories work in practise, let's look at some examples from different subjects in a UK secondary school.

In a Year 9 English class, a teacher is introducing Shakespeare's Macbeth. To build autonomy, the teacher allows students to choose how they will demonstrate their understanding of a key scene. Some might write a modern-day script, while others create a storyboard or film a short performance. This choice increases engagement with the text.

To support mastery, the teacher uses retrieval practise to ensure all students remember the key plot points before moving on to complex analysis. By making the text feel accessible, the teacher builds the students' competence. Connecting the themes of ambition and guilt to modern political events provides a sense of purpose. This makes the centuries-old play feel relevant to their lives today.

A Maths teacher is working on quadratic equations with a Year 10 group. Many students find this topic intimidating and struggle with the high cognitive load. To build competence, the teacher uses worked examples and broken-down steps. This prevents students from feeling overwhelmed and allows them to experience success early in the lesson.

The teacher also explains the utility of quadratics in fields like architecture and ballistics. This adds a layer of purpose to the abstract symbols on the board. For students who finish early, the teacher offers a "challenge zone" with more complex problems. This provides the right level of challenge to help students enter a state of flow.

In a Year 8 Science lab, students are learning about chemical reactions. The teacher builds a sense of belonging by organising the class into small research teams. Each team is responsible for a different part of the experiment and must share their findings with the rest of the group. This collaborative approach taps into the need for relatedness.

To build autonomy, teams can choose which variables they want to test within a set framework. The teacher provides immediate feedback during the practical work, which is essential for maintaining flow. Seeing the visible results of a reaction provides a sense of mastery. The students can see that their actions have a direct and predictable effect.

A PE teacher is leading a session on football skills for a Year 7 class. Some students are highly skilled, while others have never played before. To maintain flow for everyone, the teacher sets different levels of challenge for the same drill. Beginners focus on basic ball control, while more advanced players work on passing under pressure.

The teacher avoids using public praise for the "best" players, as this can discourage those who are still learning. Instead, they focus on individual progress and effort. This encourages an internal locus of control, where students see their improvement as a result of their own hard work. Building a team spirit during the session addresses the need for belonging and makes the lesson more enjoyable.

Motivation does not exist in a vacuum. It is closely linked to several other key concepts in cognitive science and education.

Carol Dweck's work on Growth Mindset is deeply connected to Attribution Theory. A student with a growth mindset believes that their intelligence and abilities can be developed through effort. This leads to a more positive attributional style, where failure is seen as a chance to learn rather than a sign of low ability.

Teachers can support both motivation and a growth mindset by praising effort and strategy rather than innate talent. When a student understands that their brain can literally get stronger through practise, they are more likely to stay motivated. This belief in the possibility of improvement is the foundation of long-term drive.

Retrieval practise is the act of pulling information from long-term memory. While it is often seen as a revision tool, it also has a significant impact on motivation. When a student successfully retrieves information, it builds their sense of competence. They feel that they are actually learning and making progress.

Regular, low-stakes quizzes can provide a sense of achievement without the pressure of a formal exam. This frequent feedback allows students to see their own growth, which is a powerful motivator. If a student feels they are constantly forgetting what they have learned, their motivation will quickly fade.

Cognitive Load Theory suggests that our working memory has a limited capacity. If a task is too complex and exceeds this capacity, the student will become frustrated and disengaged. This link between cognitive load and motivation is vital for lesson design. By managing the load, teachers can keep students in the "sweet spot" required for flow.

Breaking down tasks and providing clear instructions reduces unnecessary cognitive strain. This makes the work feel more achievable, which increases the expectation of success in the Expectancy-Value model. A well-designed lesson that respects the limits of human memory is naturally more motivating.

| Theory | Focus | Key Driver | Classroom Application | Limitation |

| :--- | :--- | :--- | :--- | :--- |

| Self-Determination | Internal Needs | Autonomy, Competence, Relatedness | Provide choices and build strong relationships. | Hard to balance all three needs for 30 students at once. |

| Flow Theory | State of Mind | Balance of Challenge and Skill | Set tasks that are neither too easy nor too hard. | The "sweet spot" is different for every student in the room. |

| Attribution Theory | Explanations | Internal vs External Locus of Control | Help students see effort as the key to success. | Deep-seated beliefs about ability are difficult to change. |

| Expectancy-Value | Decision Making | Belief in Success x Perceived Worth | Build confidence and explain real-world relevance. | Students may value things that are not academic. |

Can too much autonomy be a bad thing?

Yes, if students are given choices without enough knowledge or structure, they can become overwhelmed. This is known as the "choice paradox." Always provide a clear framework and ensure students have the necessary skills to make an informed decision. Start with small choices and gradually increase them as students become more independent.

How do I motivate a student who has given up completely?

Focus on building competence through very small, achievable tasks. These students often suffer from "learned helplessness" and need to experience success to break the cycle. Provide heavy scaffolding and celebrate every small win. Over time, these positive experiences can rebuild their expectation of success and their willingness to try.

Are sticker charts always a bad idea in primary school?

Sticker charts are not inherently bad, but they should be used carefully. They are most effective for encouraging compliance with basic routines or for jumpstarting engagement in a new area. However, they should never be the only reason a student does their work. Try to transition from stickers to verbal praise that focuses on the specific effort the student has made.

Is it possible for a task to be too motivating?

While rare, it is possible for the excitement of a task to distract from the actual learning goals. For example, a highly entertaining game might make students focus more on winning than on the subject content. This is sometimes called "seductive details." Ensure that the core learning objective remains the central focus of the activity.

How does anxiety affect motivation?

High levels of anxiety can kill motivation by making the expectation of success very low. When a student is anxious, their working memory is occupied by worrying thoughts, which increases cognitive load. Create a "low-threat, high-challenge" environment where it is safe to make mistakes. Reducing the pressure can often reveal the student's underlying drive.

Can I use these theories with students who have SEND?

Absolutely. In fact, these theories are often even more important for students with Special Educational Needs and Disabilities. These students may face more barriers to competence and autonomy. Tailoring the challenge to their specific needs and ensuring they feel a sense of belonging can have a transformative effect on their engagement.

Choose one student in your class who seems disengaged. Over the next week, conduct a "Motivation Audit" by observing their responses to different tasks. Does the work seem too hard (low competence)? Do they feel they have no say in the lesson (low autonomy)? Do they seem disconnected from their peers (low belonging)? Once you have identified a potential barrier, make one small change to address it and observe the impact on their behaviour.

Motivation acts as the engine of the classroom. It determines how much effort a student puts into a task and how long they persist when things get difficult. Understanding the mechanics of motivation allows teachers to move beyond simple rewards and punishments. This article explores the cognitive science behind student engagement and provides practical ways to apply these theories in a UK school setting.

* Motivation is a cognitive process influenced by environment and past experiences.

* Intrinsic motivation leads to higher levels of persistence and deeper conceptual understanding.

* Extrinsic rewards can jumpstart engagement but may undermine long-term interest if used poorly.

* Students must feel a sense of competence to maintain their drive for a subject.

* Autonomy allows students to feel they have some control over their learning process.

* How students explain their failures directly impacts their willingness to try again.

* A task must be seen as both achievable and valuable for a student to engage with it.

Motivation is the internal drive that directs behaviour towards a specific goal. In an educational context, it involves the desire to learn, achieve, and master new skills. Teachers often see motivation as a fixed trait that a student either possesses or lacks. However, cognitive science shows that motivation is dynamic and can be nurtured through specific classroom conditions.

Psychologists typically divide motivation into two main categories: intrinsic and extrinsic. Intrinsic motivation comes from within the individual. A student reads a book because they find the story interesting or solve a puzzle because they enjoy the challenge. This form of motivation is highly stable and leads to the best learning outcomes.

Extrinsic motivation is driven by external factors such as grades, stickers, or the avoidance of detention. While these can be effective in the short term, they do not always lead to a genuine love for the subject. If the reward is removed, the behaviour often stops. Educators must balance these two types to ensure students remain engaged even when external incentives are not present.

The transition from extrinsic to intrinsic motivation is a goal for many teachers. This process requires a shift in how students perceive the value of their schoolwork. When a student sees the utility of a skill, they are more likely to engage with it for its own sake. Understanding the research behind these drives is the first step towards building a motivated classroom.

Several key theories provide a framework for understanding why students engage with their work. These theories offer a scientific basis for classroom strategies. By looking at the work of major psychologists, we can see the patterns that govern student behaviour.

Self-Determination Theory, developed by Edward Deci and Richard Ryan, is one of the most influential models in education. It suggests that all humans have three basic psychological needs: autonomy, competence, and relatedness. When these needs are met, students show high levels of intrinsic motivation. If these needs are thwarted, motivation drops significantly.

Autonomy refers to the need to feel in control of one's actions. Students who feel forced into a task often show resentment and minimal effort. Competence is the feeling of being effective and capable in a particular area. Relatedness involves feeling connected to others and having a sense of belonging within the school community.

Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi introduced the concept of "Flow" to describe a state of total absorption in a task. When a student is in a state of flow, they lose track of time and become completely focused on what they are doing. This state occurs when there is a perfect balance between the challenge of the task and the skills of the student.

If a task is too easy, the student becomes bored. If it is too difficult, they become anxious and give up. Teachers must find the "sweet spot" where the challenge is high enough to be interesting but low enough to be manageable. Achieving flow in the classroom requires clear goals and immediate feedback.

Bernard Weiner's Attribution Theory looks at how students explain their successes and failures. These explanations, or attributions, fall into three categories: locus of causality, stability, and controllability. A student might attribute a bad grade to a lack of effort (internal, unstable, controllable) or to the difficulty of the test (external, stable, uncontrollable).

Students with high motivation tend to attribute success to their own effort and ability. They see failure as a temporary setback that can be overcome with more work. Conversely, discouraged students often believe their failures are due to a permanent lack of ability. Changing these attributions is vital for helping students regain their drive.

Jacquelynne Eccles developed the Expectancy-Value Theory to explain why students choose specific tasks. The theory suggests that motivation is the product of two factors: the expectation of success and the perceived value of the task. If a student believes they cannot succeed, they will not try, regardless of how important the task is.

Similarly, if they think they can succeed but find the task pointless, they will show little interest. Value can be defined by interest, importance, or utility. Teachers must work on both sides of this equation by building confidence and explaining why the material matters.

Applying these theories requires a shift in teaching practise. We can categorise effective strategies into four main areas: autonomy, mastery, purpose, and belonging. These areas align with the findings of cognitive science and provide a roadmap for teachers.

Autonomy does not mean letting students do whatever they want. Instead, it involves providing choices within a structured environment. You might allow students to choose which topic to research for a project or which format to use for their final presentation. This sense of choice gives students a feeling of ownership over their work.

When students have a say in their learning, they are more likely to take responsibility for the outcome. Teachers can also provide autonomy by involving students in setting classroom rules. Small choices, such as the order in which tasks are completed, can make a big difference. This approach reduces the feeling of being controlled and increases genuine engagement.

Mastery is closely linked to the concept of competence in Self-Determination Theory. Students are motivated when they can see themselves getting better at something. To support mastery, teachers should break complex tasks into smaller, manageable steps. This allows students to experience frequent small wins, which builds momentum.

Effective scaffolding is essential for mastery. Provide enough support so the student can succeed, then slowly remove that support as they become more proficient. High-quality feedback that focuses on the process rather than just the result also helps. When a student knows exactly what they did right and what to do next, their motivation remains high.

Students often ask, "Why are we learning this?" Providing a clear purpose is a powerful way to increase the perceived value of a task. Connect lesson content to real-world applications or to the students' own interests. Showing how a mathematical concept is used in engineering or how a historical event shaped the modern world can spark curiosity.

Purpose can also be internal. Help students see how mastering a particular skill will help them reach their personal goals. When learning feels relevant, the effort required seems more worthwhile. Avoid vague answers like "because it is on the exam" as these focus on extrinsic pressure rather than genuine purpose.

A student who feels isolated or unwelcome in the classroom is unlikely to be motivated. Relatedness and a sense of belonging are fundamental human needs. Build a positive classroom culture where every student feels valued and respected. Encourage collaborative work where students can support each other and share ideas.

Teacher-student relationships are a vital part of belonging. Taking an interest in a student's life outside of the subject can build trust and rapport. When students feel that their teacher cares about their progress, they are more likely to put in the effort. A safe, supportive environment allows students to take risks without the fear of being mocked.

There are several myths about motivation that can lead teachers astray. Addressing these misconceptions is essential for developing a more effective approach.

Some people believe that giving a reward for a task always destroys intrinsic interest. This is a simplification of the research. Rewards can actually increase motivation if they are used to recognise competence. For example, a certificate for mastering a difficult skill can make a student feel proud and more likely to continue.

The danger lies in using rewards as a form of control or for tasks that the student already finds interesting. If a student loves reading, giving them a sticker for every book might make them focus on the sticker rather than the story. Use rewards sparingly and focus them on effort and achievement rather than mere compliance.

The label "lazy" is often used to describe students who show little effort in class. However, this term rarely explains the underlying cause of the behaviour. What looks like laziness is often a defence mechanism against a fear of failure. If a student believes they cannot succeed, they may stop trying to protect their self-esteem.

Low motivation can also be a sign of underlying cognitive overload or a lack of prerequisite knowledge. If the work is consistently too hard, the student will eventually give up. Instead of labelling a student as lazy, look for the barriers that are preventing them from engaging. Addressing these barriers is more effective than simple reprimands.

It is common to hear teachers say that a student "just isn't motivated." This implies that motivation is a permanent trait like height or eye colour. In reality, motivation varies from day to day and from subject to subject. A student might be highly driven in PE but struggle to find any interest in History.

Because motivation is dynamic, it can be influenced by the teacher's actions and the classroom environment. By changing the way a task is presented or by providing more support, a teacher can turn a disengaged student into a motivated one. Viewing motivation as something that can be developed is a more helpful approach for both teachers and students.

To see how these theories work in practise, let's look at some examples from different subjects in a UK secondary school.

In a Year 9 English class, a teacher is introducing Shakespeare's Macbeth. To build autonomy, the teacher allows students to choose how they will demonstrate their understanding of a key scene. Some might write a modern-day script, while others create a storyboard or film a short performance. This choice increases engagement with the text.

To support mastery, the teacher uses retrieval practise to ensure all students remember the key plot points before moving on to complex analysis. By making the text feel accessible, the teacher builds the students' competence. Connecting the themes of ambition and guilt to modern political events provides a sense of purpose. This makes the centuries-old play feel relevant to their lives today.

A Maths teacher is working on quadratic equations with a Year 10 group. Many students find this topic intimidating and struggle with the high cognitive load. To build competence, the teacher uses worked examples and broken-down steps. This prevents students from feeling overwhelmed and allows them to experience success early in the lesson.

The teacher also explains the utility of quadratics in fields like architecture and ballistics. This adds a layer of purpose to the abstract symbols on the board. For students who finish early, the teacher offers a "challenge zone" with more complex problems. This provides the right level of challenge to help students enter a state of flow.

In a Year 8 Science lab, students are learning about chemical reactions. The teacher builds a sense of belonging by organising the class into small research teams. Each team is responsible for a different part of the experiment and must share their findings with the rest of the group. This collaborative approach taps into the need for relatedness.

To build autonomy, teams can choose which variables they want to test within a set framework. The teacher provides immediate feedback during the practical work, which is essential for maintaining flow. Seeing the visible results of a reaction provides a sense of mastery. The students can see that their actions have a direct and predictable effect.

A PE teacher is leading a session on football skills for a Year 7 class. Some students are highly skilled, while others have never played before. To maintain flow for everyone, the teacher sets different levels of challenge for the same drill. Beginners focus on basic ball control, while more advanced players work on passing under pressure.

The teacher avoids using public praise for the "best" players, as this can discourage those who are still learning. Instead, they focus on individual progress and effort. This encourages an internal locus of control, where students see their improvement as a result of their own hard work. Building a team spirit during the session addresses the need for belonging and makes the lesson more enjoyable.

Motivation does not exist in a vacuum. It is closely linked to several other key concepts in cognitive science and education.

Carol Dweck's work on Growth Mindset is deeply connected to Attribution Theory. A student with a growth mindset believes that their intelligence and abilities can be developed through effort. This leads to a more positive attributional style, where failure is seen as a chance to learn rather than a sign of low ability.

Teachers can support both motivation and a growth mindset by praising effort and strategy rather than innate talent. When a student understands that their brain can literally get stronger through practise, they are more likely to stay motivated. This belief in the possibility of improvement is the foundation of long-term drive.

Retrieval practise is the act of pulling information from long-term memory. While it is often seen as a revision tool, it also has a significant impact on motivation. When a student successfully retrieves information, it builds their sense of competence. They feel that they are actually learning and making progress.

Regular, low-stakes quizzes can provide a sense of achievement without the pressure of a formal exam. This frequent feedback allows students to see their own growth, which is a powerful motivator. If a student feels they are constantly forgetting what they have learned, their motivation will quickly fade.

Cognitive Load Theory suggests that our working memory has a limited capacity. If a task is too complex and exceeds this capacity, the student will become frustrated and disengaged. This link between cognitive load and motivation is vital for lesson design. By managing the load, teachers can keep students in the "sweet spot" required for flow.

Breaking down tasks and providing clear instructions reduces unnecessary cognitive strain. This makes the work feel more achievable, which increases the expectation of success in the Expectancy-Value model. A well-designed lesson that respects the limits of human memory is naturally more motivating.

| Theory | Focus | Key Driver | Classroom Application | Limitation |

| :--- | :--- | :--- | :--- | :--- |

| Self-Determination | Internal Needs | Autonomy, Competence, Relatedness | Provide choices and build strong relationships. | Hard to balance all three needs for 30 students at once. |

| Flow Theory | State of Mind | Balance of Challenge and Skill | Set tasks that are neither too easy nor too hard. | The "sweet spot" is different for every student in the room. |

| Attribution Theory | Explanations | Internal vs External Locus of Control | Help students see effort as the key to success. | Deep-seated beliefs about ability are difficult to change. |

| Expectancy-Value | Decision Making | Belief in Success x Perceived Worth | Build confidence and explain real-world relevance. | Students may value things that are not academic. |

Can too much autonomy be a bad thing?

Yes, if students are given choices without enough knowledge or structure, they can become overwhelmed. This is known as the "choice paradox." Always provide a clear framework and ensure students have the necessary skills to make an informed decision. Start with small choices and gradually increase them as students become more independent.

How do I motivate a student who has given up completely?

Focus on building competence through very small, achievable tasks. These students often suffer from "learned helplessness" and need to experience success to break the cycle. Provide heavy scaffolding and celebrate every small win. Over time, these positive experiences can rebuild their expectation of success and their willingness to try.

Are sticker charts always a bad idea in primary school?

Sticker charts are not inherently bad, but they should be used carefully. They are most effective for encouraging compliance with basic routines or for jumpstarting engagement in a new area. However, they should never be the only reason a student does their work. Try to transition from stickers to verbal praise that focuses on the specific effort the student has made.

Is it possible for a task to be too motivating?

While rare, it is possible for the excitement of a task to distract from the actual learning goals. For example, a highly entertaining game might make students focus more on winning than on the subject content. This is sometimes called "seductive details." Ensure that the core learning objective remains the central focus of the activity.

How does anxiety affect motivation?

High levels of anxiety can kill motivation by making the expectation of success very low. When a student is anxious, their working memory is occupied by worrying thoughts, which increases cognitive load. Create a "low-threat, high-challenge" environment where it is safe to make mistakes. Reducing the pressure can often reveal the student's underlying drive.

Can I use these theories with students who have SEND?

Absolutely. In fact, these theories are often even more important for students with Special Educational Needs and Disabilities. These students may face more barriers to competence and autonomy. Tailoring the challenge to their specific needs and ensuring they feel a sense of belonging can have a transformative effect on their engagement.

Choose one student in your class who seems disengaged. Over the next week, conduct a "Motivation Audit" by observing their responses to different tasks. Does the work seem too hard (low competence)? Do they feel they have no say in the lesson (low autonomy)? Do they seem disconnected from their peers (low belonging)? Once you have identified a potential barrier, make one small change to address it and observe the impact on their behaviour.

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/motivation-education-teachers-need-know#article","headline":"Motivation in Education: What Teachers Need to Know","description":"Learn about Motivation in Education: What Teachers Need to Know. A comprehensive guide for teachers.","datePublished":"2026-02-17T10:47:10.892Z","dateModified":"2026-02-17T13:57:47.126Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/motivation-education-teachers-need-know"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/6994472ed3f93df8e1d1b042_699446b7913dd1af24a603e4_motivation-in-education-what-t-comparison-1771325111142.webp","wordCount":3222},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/motivation-education-teachers-need-know#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"Motivation in Education: What Teachers Need to Know","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/motivation-education-teachers-need-know"}]}]}