Attention and Learning: A Cognitive Science Approach

Examine how attention influences learning in classrooms and apply evidence-based strategies to enhance student focus and minimize distractions effectively.

Examine how attention influences learning in classrooms and apply evidence-based strategies to enhance student focus and minimize distractions effectively.

Cognitive science reveals that attention functions as the gateway to all learning, determining which information enters our working memory and gets processed into long-term knowledge. This fundamental relationship explains why students can sit through an entire lesson yet retain virtually nothing, or conversely, why a single moment of focused attention can lead to breakthrough understanding. Research shows that attention operates through multiple interconnected systems in the brain, each playing a distinct role in how we filter, sustain, and direct our mental resources towards learning tasks. Understanding these mechanisms offers educators powerful insights into why traditional teaching methods often fail to capture student focus, and more importantly, what actually works instead.

Attention is the gateway to learning. Information that doesn't receive attention cannot be encoded, consolidated, or retrieved. No matter how brilliantly you teach, students who aren't attending won't learn. Yet attention is finite, effortful, and increasingly competed for by devices, distractions, and demanding schedules.

Understanding how attention works gives teachers practical strategies for capturing and maintaining student focus. Cognitive science has revealed that attention isn't a single system but a set of interconnected processes that can be supported, trained, and improved through instructional design, skills that are fundamental to self-regulated learning.

working memory" loading="lazy">

working memory" loading="lazy">

Attention refers to the cognitive processes that select information for further processing while filtering out irrelevant stimuli. Your brain is constantly bombarded with far more sensory information than it can handle. Attention determines what gets through.

Think of attention as a spotlight in a dark theatre. The spotlight illuminates only a small portion of the stage at any moment. What falls within the beam is visible; what falls outside remains in darkness. Attention works similarly, selecting certain information for conscious processing while the rest fades into the background.

But attention is more complex than a simple spotlight. Modern cognitive science describes attention as comprising multiple systems that work together.

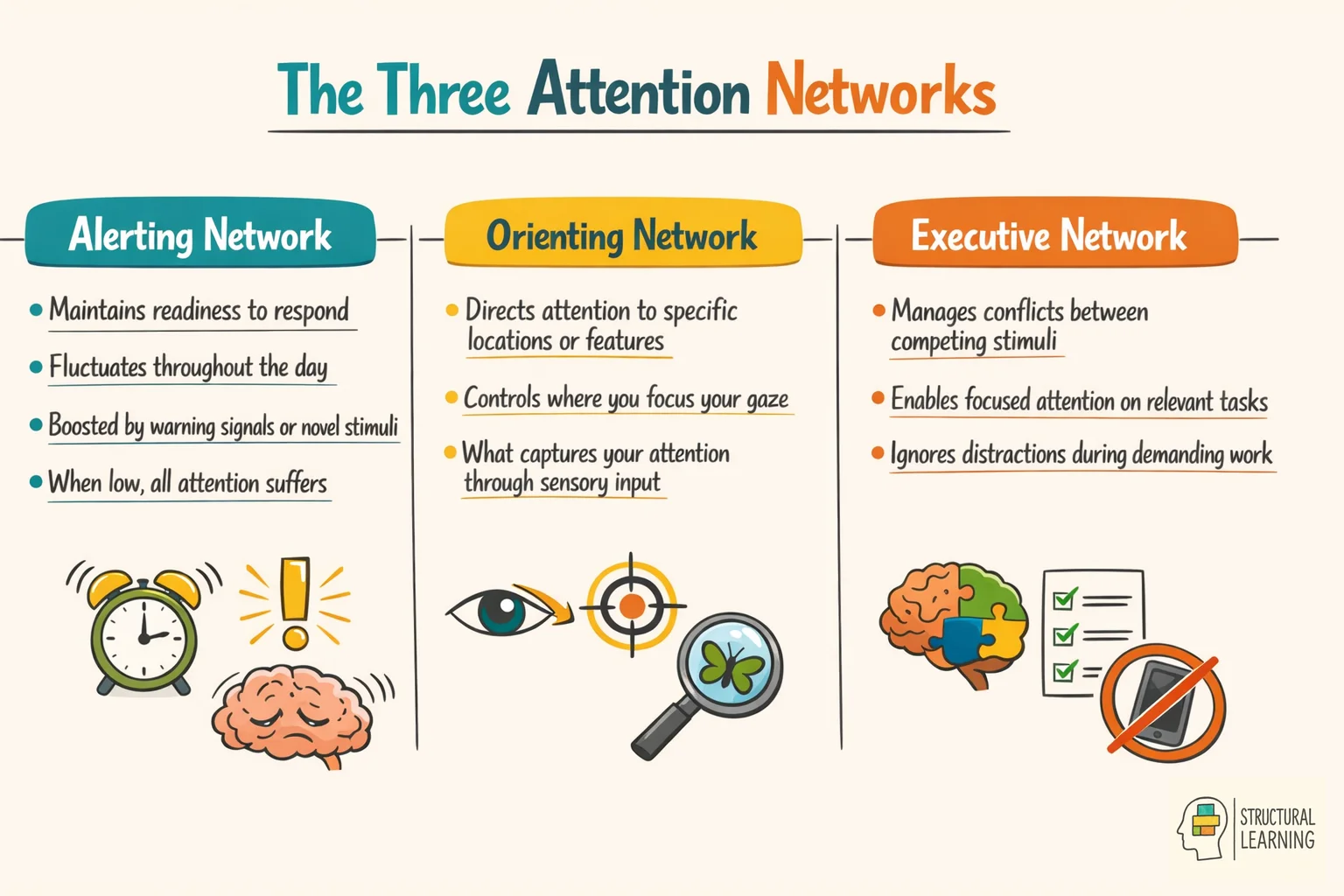

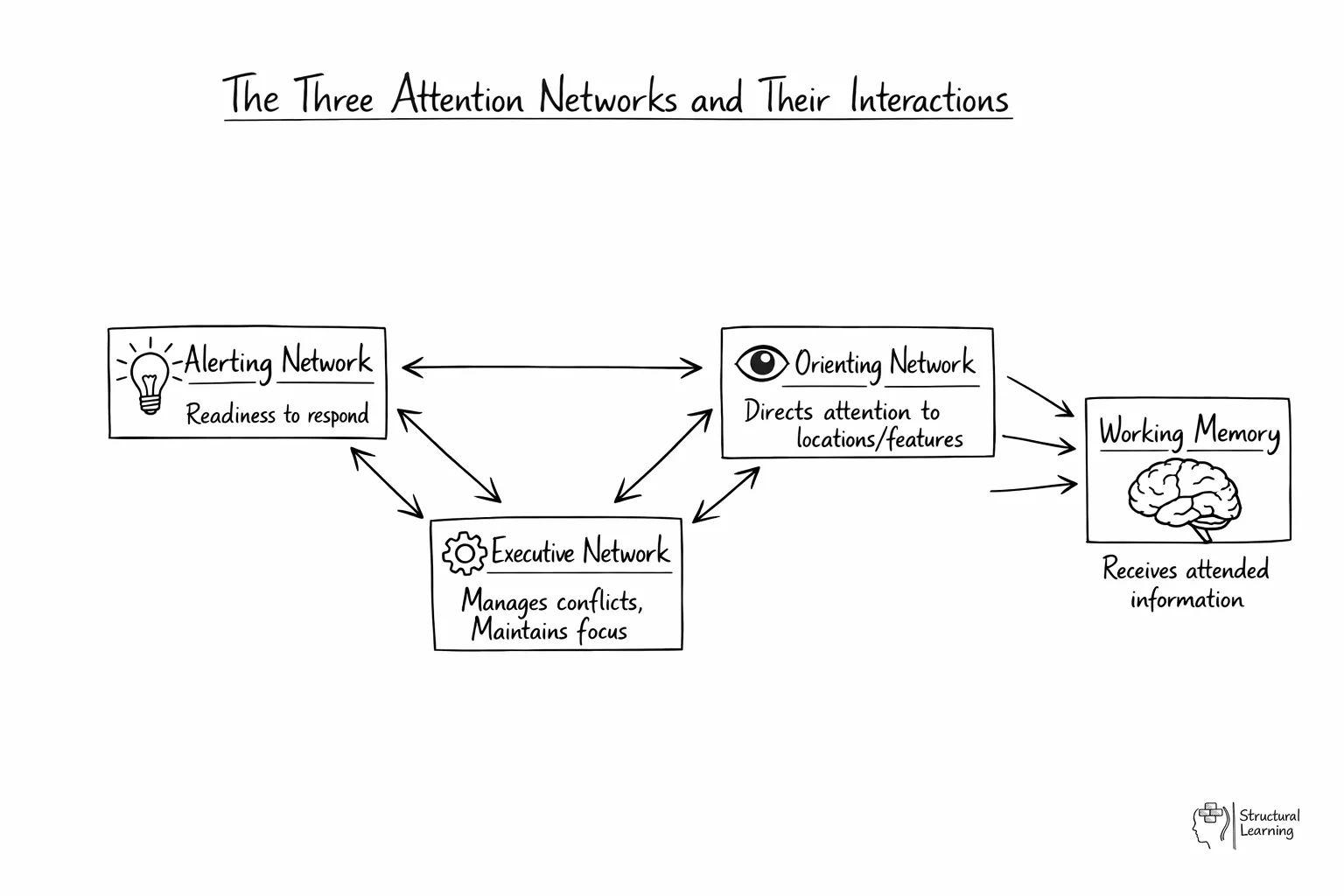

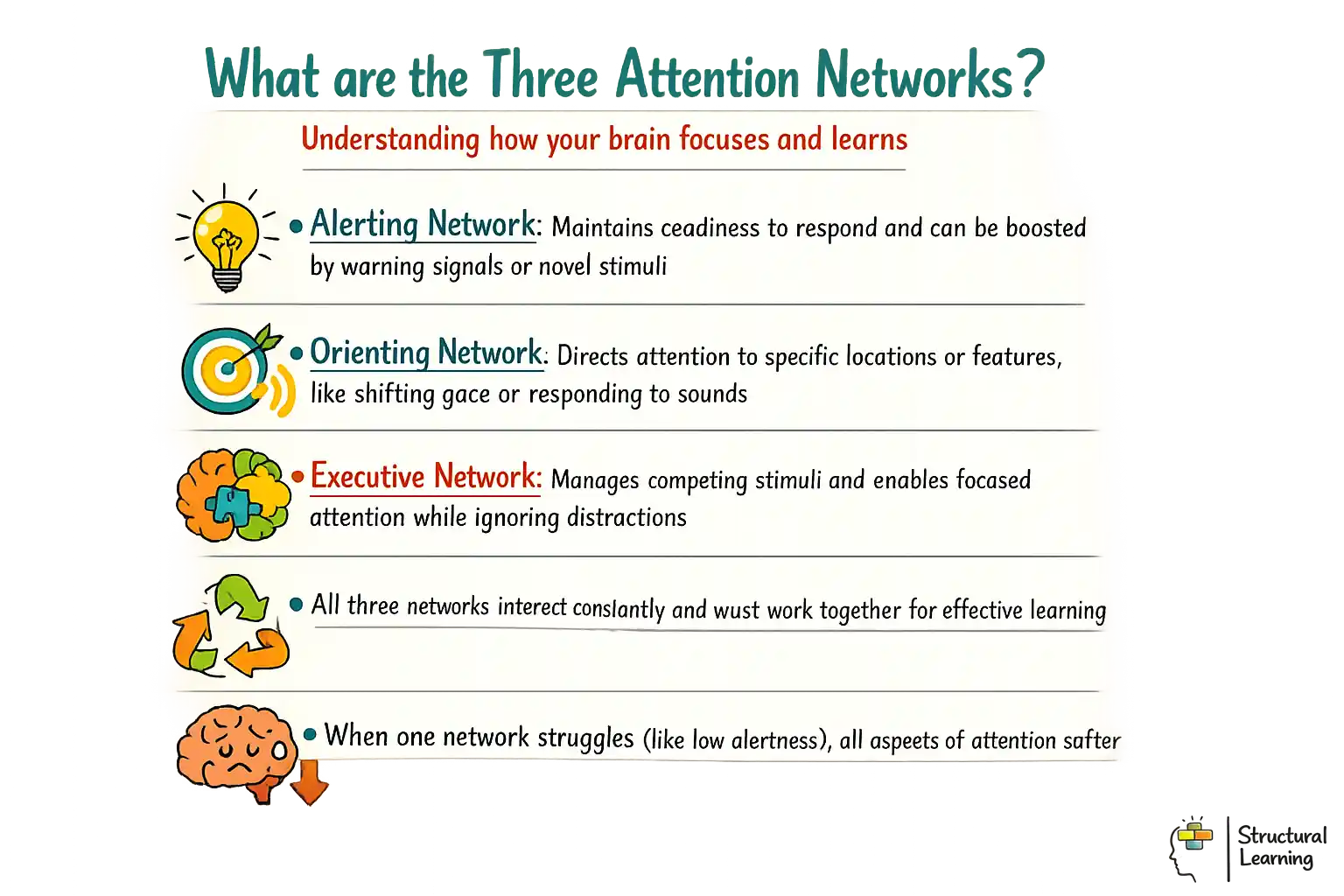

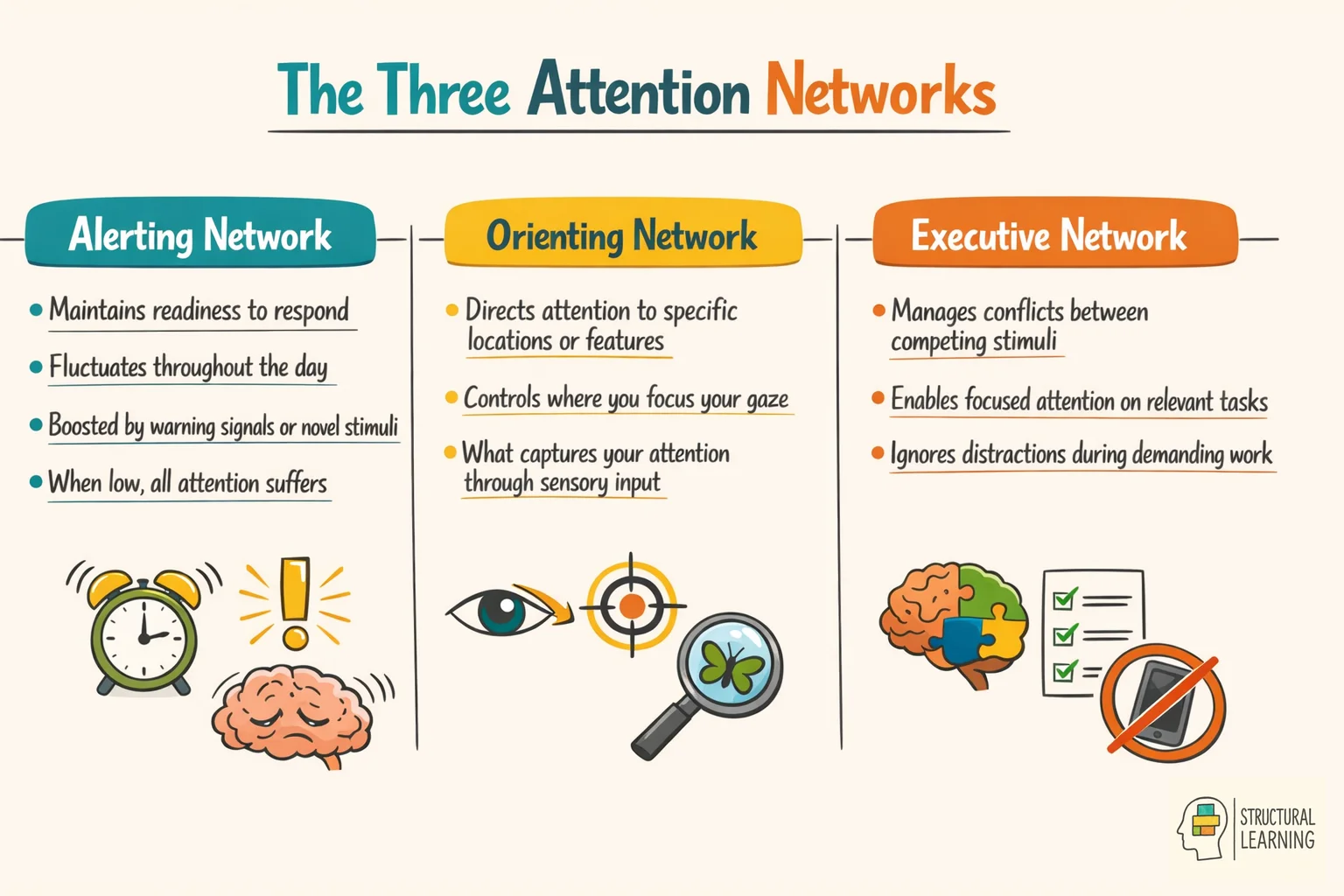

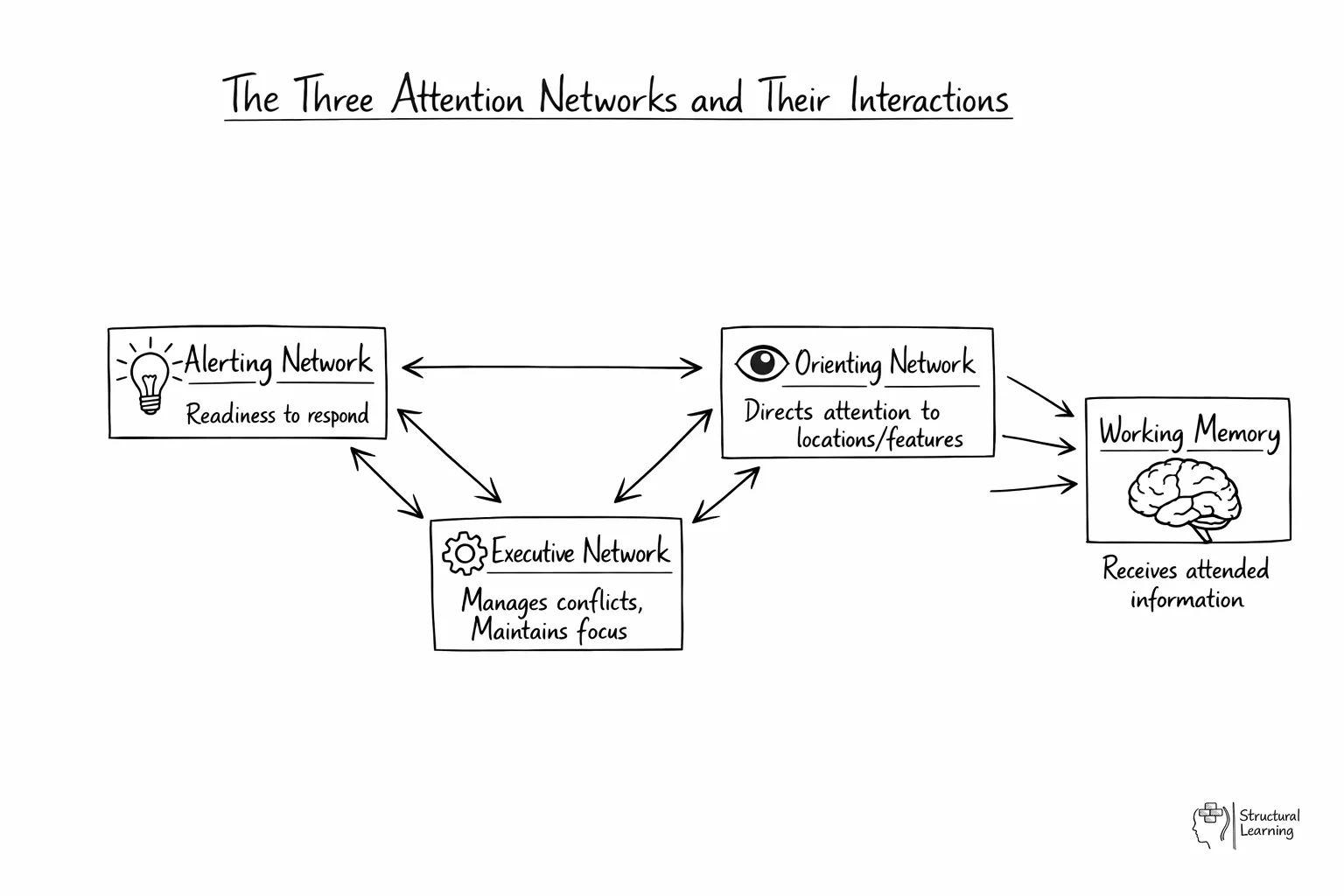

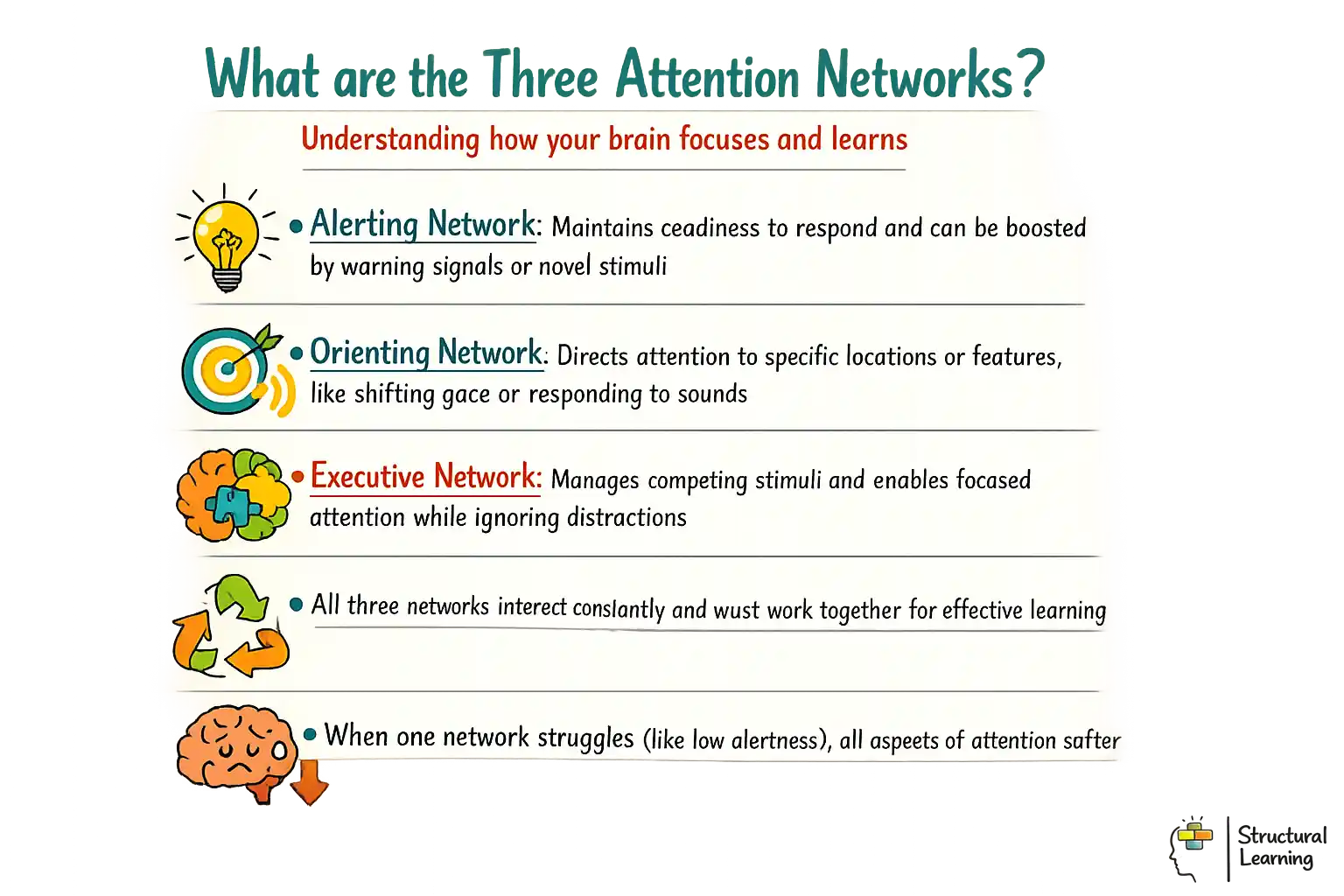

Michael Posner and colleagues identified three interconnected attention networks that serve different functions.

The alerting network maintains a state of readiness to respond. Alertness fluctuates throughout the day and can be temporarily boosted by warning signals or novel stimuli. When alertness is low, all aspects of attention suffer.

The orienting network directs attention to specific locations or features. When you shift your gaze to look at something, or when a loud sound captures your attention, the orienting network is at work.

The executive network manages conflicts between competing stimuli and enables focused attention on task-relevant information. This system is critical for ignoring distractions and maintaining concentration on demanding tasks. Students with ADHD often struggle particularly with this executive function.

These networks interact constantly. A well-rested student with appropriate alertness can orient to the teacher and use executive control to maintain focus despite distractions. A tired student may struggle with all three.

Attention acts as the gateway that determines which information enters working memory for processing. Without focused attention, information cannot move from sensory input to working memory, preventing encoding and learning. The limited capacity of both systems means that excessive cognitive load or divided attention severely impairs learning outcomes.

| Attention Type | Definition | Classroom Example | Support Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Selective | Focus on one stimulus | Listening to teacher | Reduce distractions |

| Sustained | Maintain focus over time | Extended reading | Chunked activities |

| Divided | Multiple tasks simultaneously | Note-taking while listening | Reduce demands |

| Executive | Control and regulation | Ignoring distractions | Self-monitoring training |

Attention is intimately connected to memory. Working memory holds information in mind while we think about it, and attention determines what enters working memory in the first place.

Information must be attended to before it can be encoded into memory. This makes attention the critical first stage of learning. If students aren't attending during instruction, they can't be learning, regardless of how well the material is presented.

Teachers sometimes assume that if information is presented, students will absorb it. But presentation without attention produces no learning. The challenge isn't just making information available; it's ensuring it receives attention through engagement strategies.

Cognitive load theory explains how attention limits constrain learning. When instructional demands exceed attention capacity, learning suffers. Well-designed instruction manages attention demands to ensure essential information receives adequate processing.

High cognitive load consumes attention resources, leaving less available for the learning itself. Reducing extraneous load frees attention for productive engagement with content. Teachers can provide scaffolding to support students' attention and reduce unnecessary demands.

The three attention systems are alerting (maintaining vigilance and readiness), orienting (directing focus to specific stimuli), and executive control (managing conflicts and sustaining focus). These systems work together like a coordinated network, with alerting preparing the brain, orienting selecting targets, and executive control maintaining focus despite distractions. Teachers can design active learning activities that engage each system appropriately to improve student learning. For students with special educational needs, understanding these attention systems becomes particularly important.

Understanding different aspects of attention helps teachers address specific attention challenges. This knowledge also helps in providing appropriate feedback to students about their attention and learning processes, particularly when combined with social-emotional learning support.

Cognitive science reveals that attention functions as the gateway to all learning, determining which information enters our working memory and gets processed into long-term knowledge. This fundamental relationship explains why students can sit through an entire lesson yet retain virtually nothing, or conversely, why a single moment of focused attention can lead to breakthrough understanding. Research shows that attention operates through multiple interconnected systems in the brain, each playing a distinct role in how we filter, sustain, and direct our mental resources towards learning tasks. Understanding these mechanisms offers educators powerful insights into why traditional teaching methods often fail to capture student focus, and more importantly, what actually works instead.

Attention is the gateway to learning. Information that doesn't receive attention cannot be encoded, consolidated, or retrieved. No matter how brilliantly you teach, students who aren't attending won't learn. Yet attention is finite, effortful, and increasingly competed for by devices, distractions, and demanding schedules.

Understanding how attention works gives teachers practical strategies for capturing and maintaining student focus. Cognitive science has revealed that attention isn't a single system but a set of interconnected processes that can be supported, trained, and improved through instructional design, skills that are fundamental to self-regulated learning.

working memory" loading="lazy">

working memory" loading="lazy">

Attention refers to the cognitive processes that select information for further processing while filtering out irrelevant stimuli. Your brain is constantly bombarded with far more sensory information than it can handle. Attention determines what gets through.

Think of attention as a spotlight in a dark theatre. The spotlight illuminates only a small portion of the stage at any moment. What falls within the beam is visible; what falls outside remains in darkness. Attention works similarly, selecting certain information for conscious processing while the rest fades into the background.

But attention is more complex than a simple spotlight. Modern cognitive science describes attention as comprising multiple systems that work together.

Michael Posner and colleagues identified three interconnected attention networks that serve different functions.

The alerting network maintains a state of readiness to respond. Alertness fluctuates throughout the day and can be temporarily boosted by warning signals or novel stimuli. When alertness is low, all aspects of attention suffer.

The orienting network directs attention to specific locations or features. When you shift your gaze to look at something, or when a loud sound captures your attention, the orienting network is at work.

The executive network manages conflicts between competing stimuli and enables focused attention on task-relevant information. This system is critical for ignoring distractions and maintaining concentration on demanding tasks. Students with ADHD often struggle particularly with this executive function.

These networks interact constantly. A well-rested student with appropriate alertness can orient to the teacher and use executive control to maintain focus despite distractions. A tired student may struggle with all three.

Attention acts as the gateway that determines which information enters working memory for processing. Without focused attention, information cannot move from sensory input to working memory, preventing encoding and learning. The limited capacity of both systems means that excessive cognitive load or divided attention severely impairs learning outcomes.

| Attention Type | Definition | Classroom Example | Support Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Selective | Focus on one stimulus | Listening to teacher | Reduce distractions |

| Sustained | Maintain focus over time | Extended reading | Chunked activities |

| Divided | Multiple tasks simultaneously | Note-taking while listening | Reduce demands |

| Executive | Control and regulation | Ignoring distractions | Self-monitoring training |

Attention is intimately connected to memory. Working memory holds information in mind while we think about it, and attention determines what enters working memory in the first place.

Information must be attended to before it can be encoded into memory. This makes attention the critical first stage of learning. If students aren't attending during instruction, they can't be learning, regardless of how well the material is presented.

Teachers sometimes assume that if information is presented, students will absorb it. But presentation without attention produces no learning. The challenge isn't just making information available; it's ensuring it receives attention through engagement strategies.

Cognitive load theory explains how attention limits constrain learning. When instructional demands exceed attention capacity, learning suffers. Well-designed instruction manages attention demands to ensure essential information receives adequate processing.

High cognitive load consumes attention resources, leaving less available for the learning itself. Reducing extraneous load frees attention for productive engagement with content. Teachers can provide scaffolding to support students' attention and reduce unnecessary demands.

The three attention systems are alerting (maintaining vigilance and readiness), orienting (directing focus to specific stimuli), and executive control (managing conflicts and sustaining focus). These systems work together like a coordinated network, with alerting preparing the brain, orienting selecting targets, and executive control maintaining focus despite distractions. Teachers can design active learning activities that engage each system appropriately to improve student learning. For students with special educational needs, understanding these attention systems becomes particularly important.

Understanding different aspects of attention helps teachers address specific attention challenges. This knowledge also helps in providing appropriate feedback to students about their attention and learning processes, particularly when combined with social-emotional learning support.

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/attention-learning-cognitive-science#article","headline":"Attention and Learning: A Cognitive Science Approach","description":"Explore how attention shapes learning in the classroom, with evidence-based strategies to support student focus and reduce distraction in an increasingly dem...","datePublished":"2025-12-29T10:25:19.323Z","dateModified":"2026-01-26T10:09:32.212Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/attention-learning-cognitive-science"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/696e0daf618053e96d4c4fc1_6968c95cd7b993ad80823482_6968c95ac3dd6b460c63680f_attention-learning-cognitive-science-infographic.webp","wordCount":4046},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/attention-learning-cognitive-science#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"Attention and Learning: A Cognitive Science Approach","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/attention-learning-cognitive-science"}]}]}