Fluency Illusions: Why Students Think They Know More Than They Do

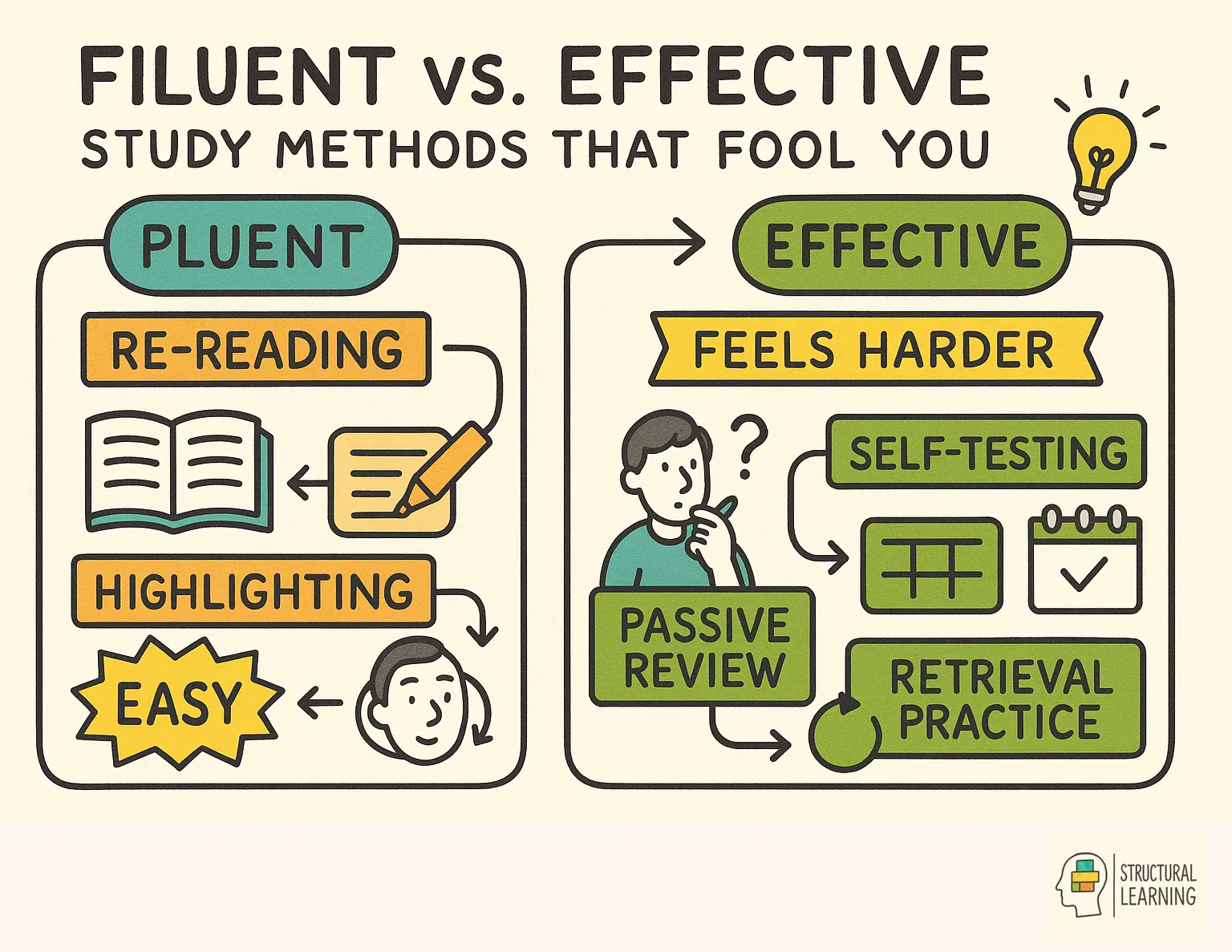

Fluency illusions cause students to overestimate their learning when material feels easy to process, leading to poor study choices and unexpected exam failures.

Fluency illusions cause students to overestimate their learning when material feels easy to process, leading to poor study choices and unexpected exam failures.

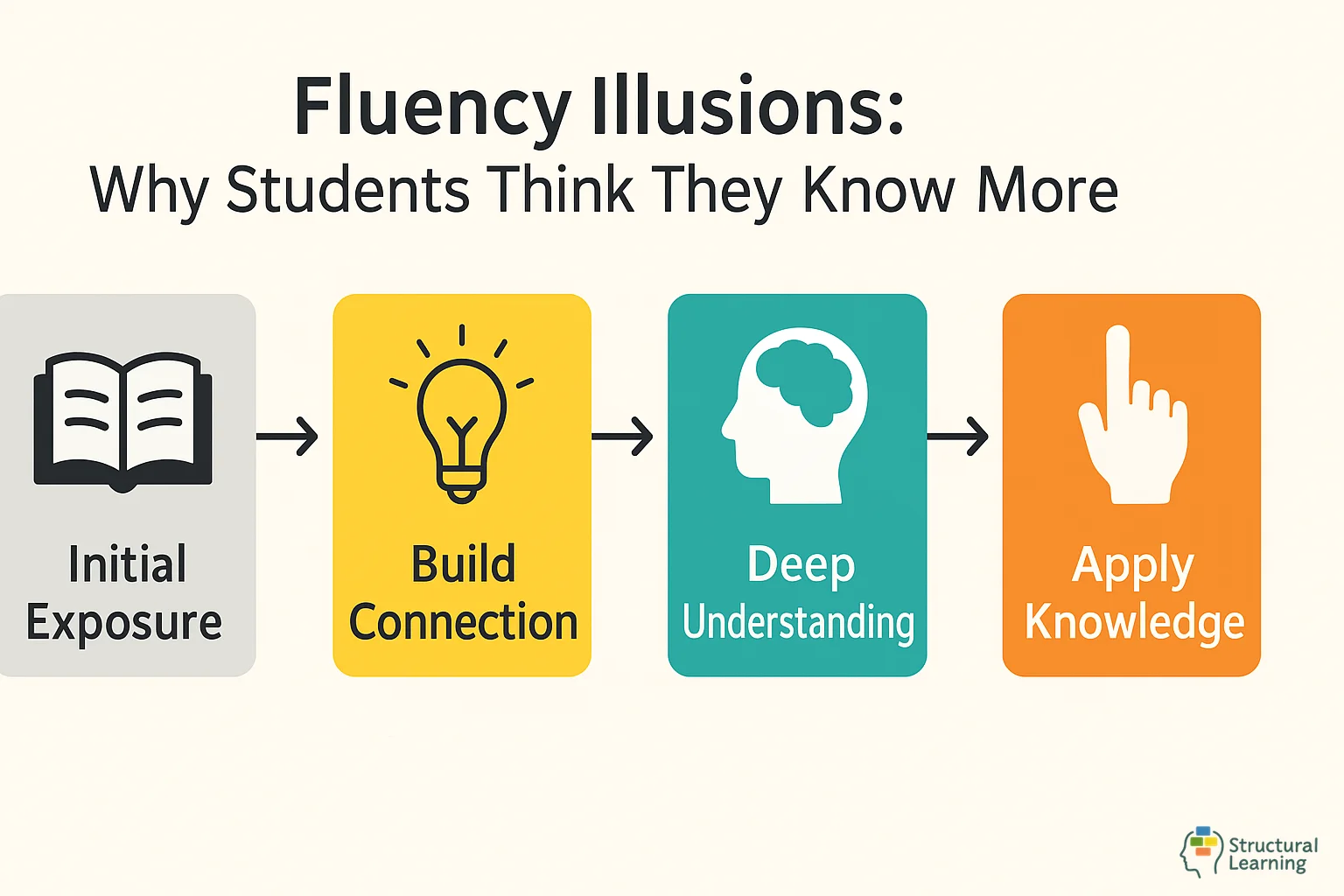

Every teacher has witnessed the disconnect: a student insists they've studied thoroughly, yet performs poorly on the assessment. The student isn't lying or making excuses. They genuinely believed they knew the material. This gap between perceived and actual knowledge represents one of the most significant obstacles to effective learning. When students can't accurately judge what they know, they make poor decisions about how to study, when to stop studying, and which material needs more attention and how to transfer knowledge effectively.

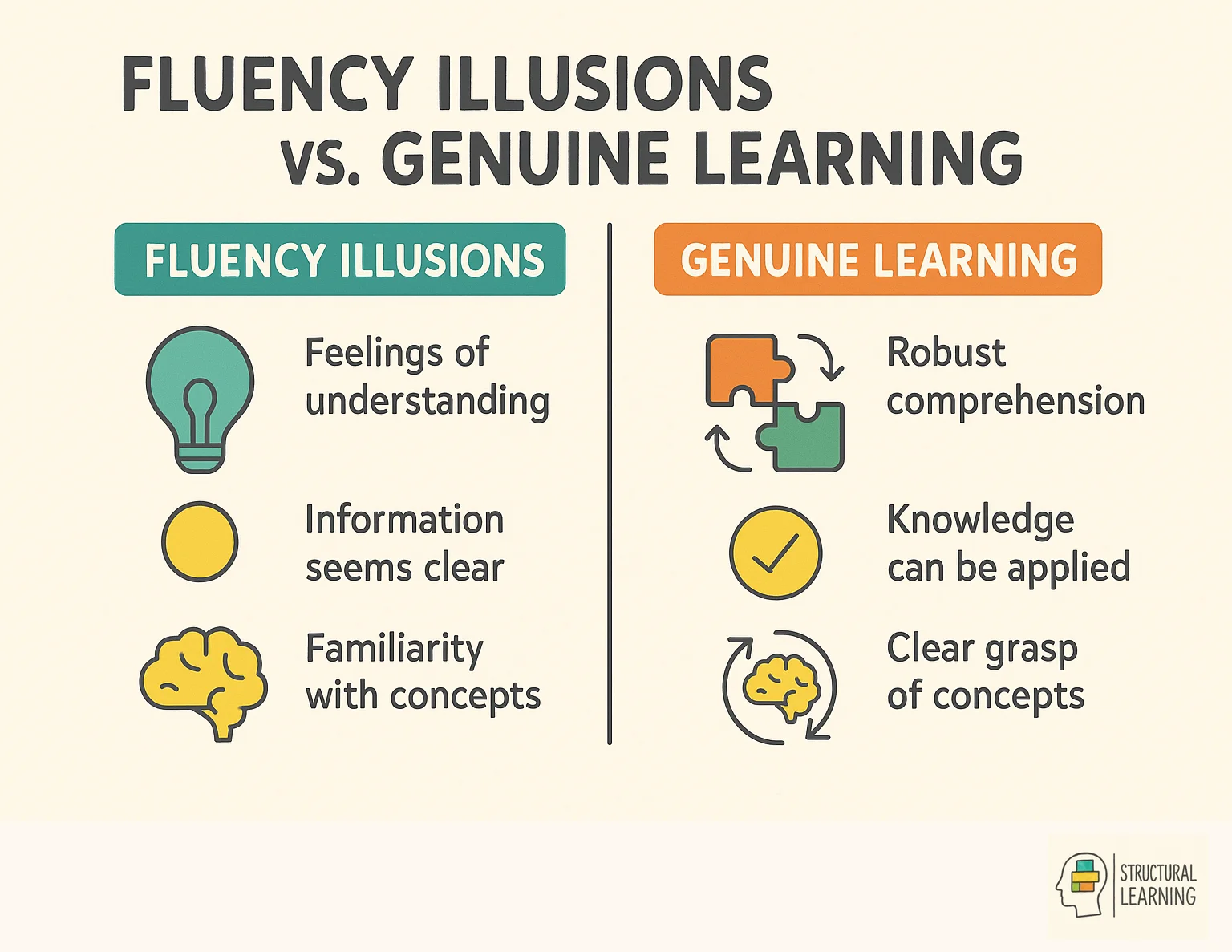

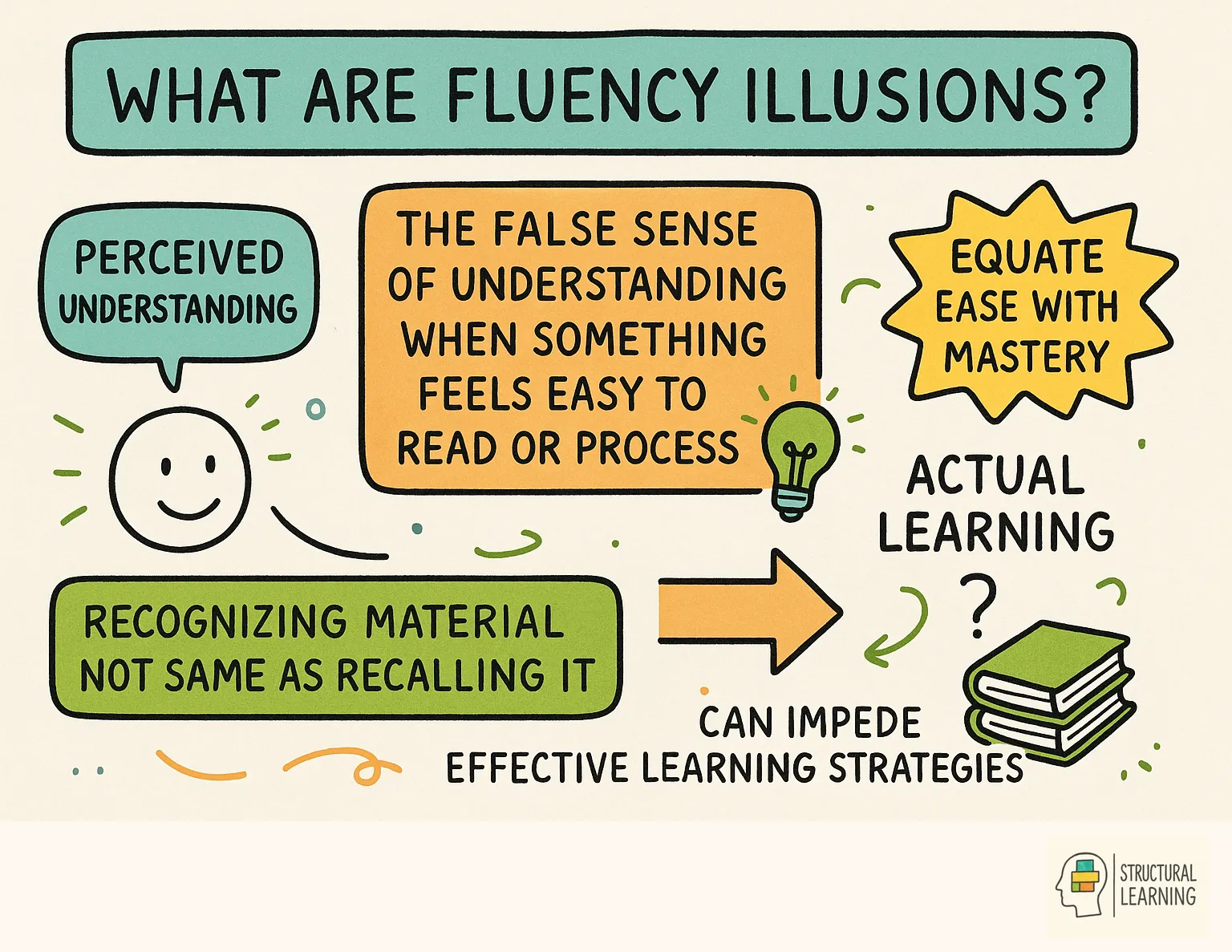

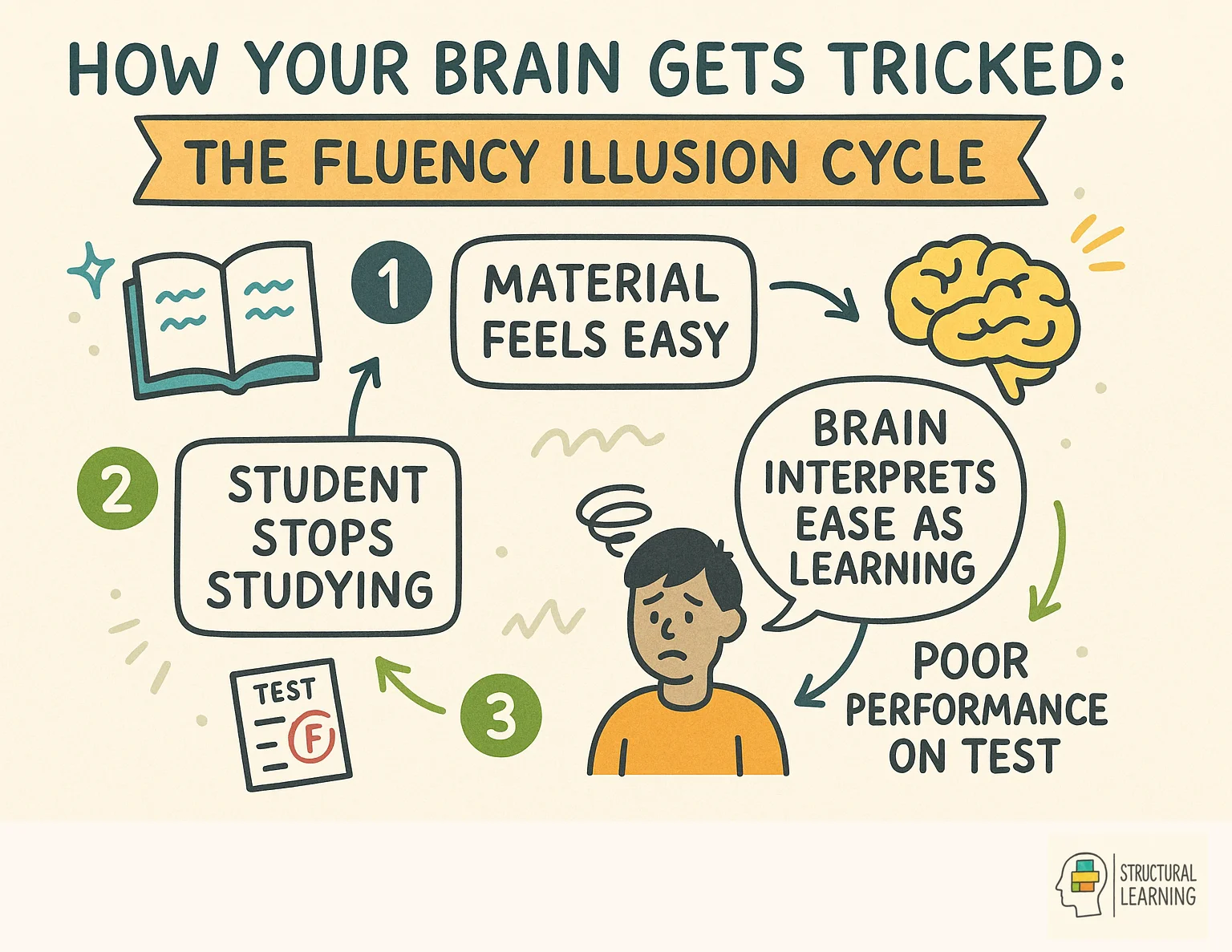

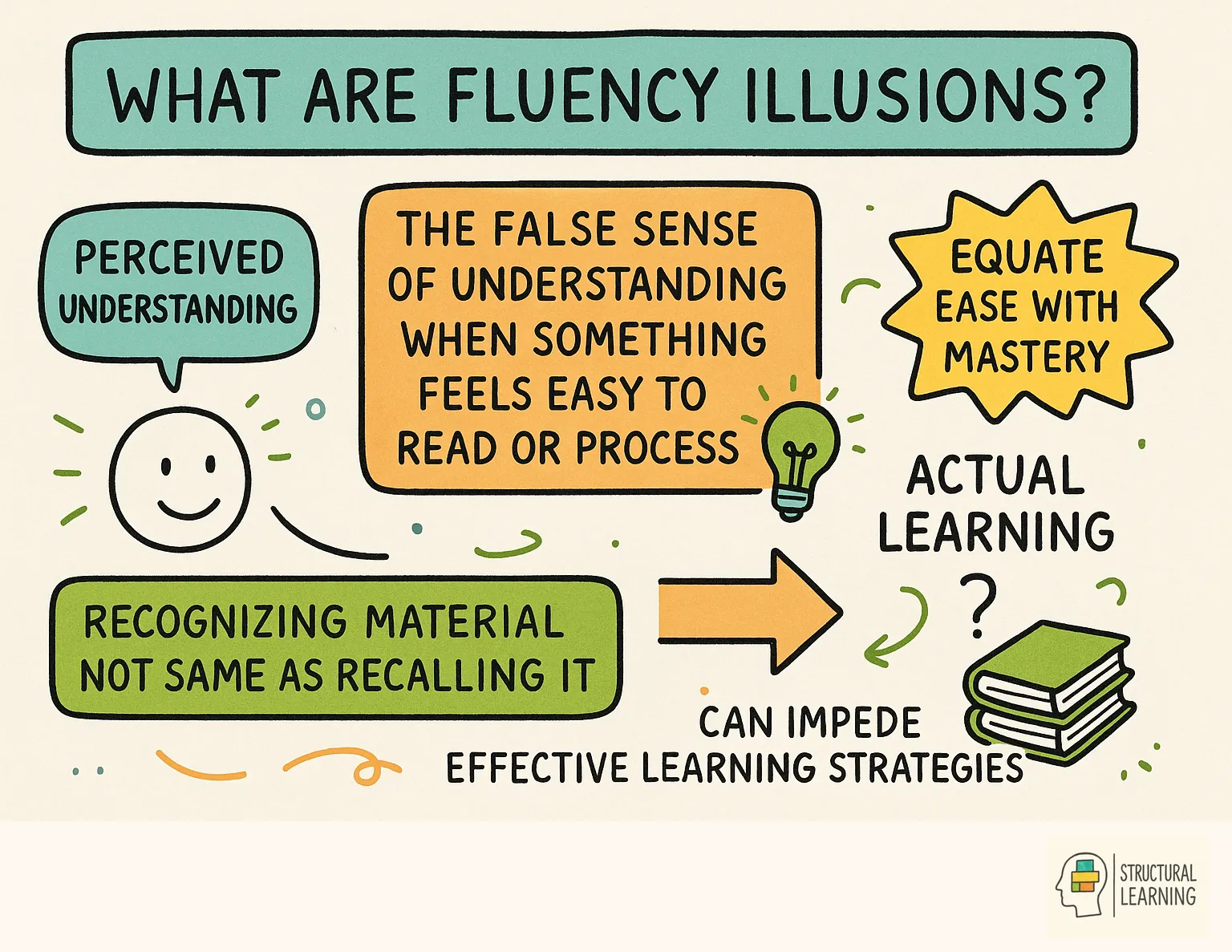

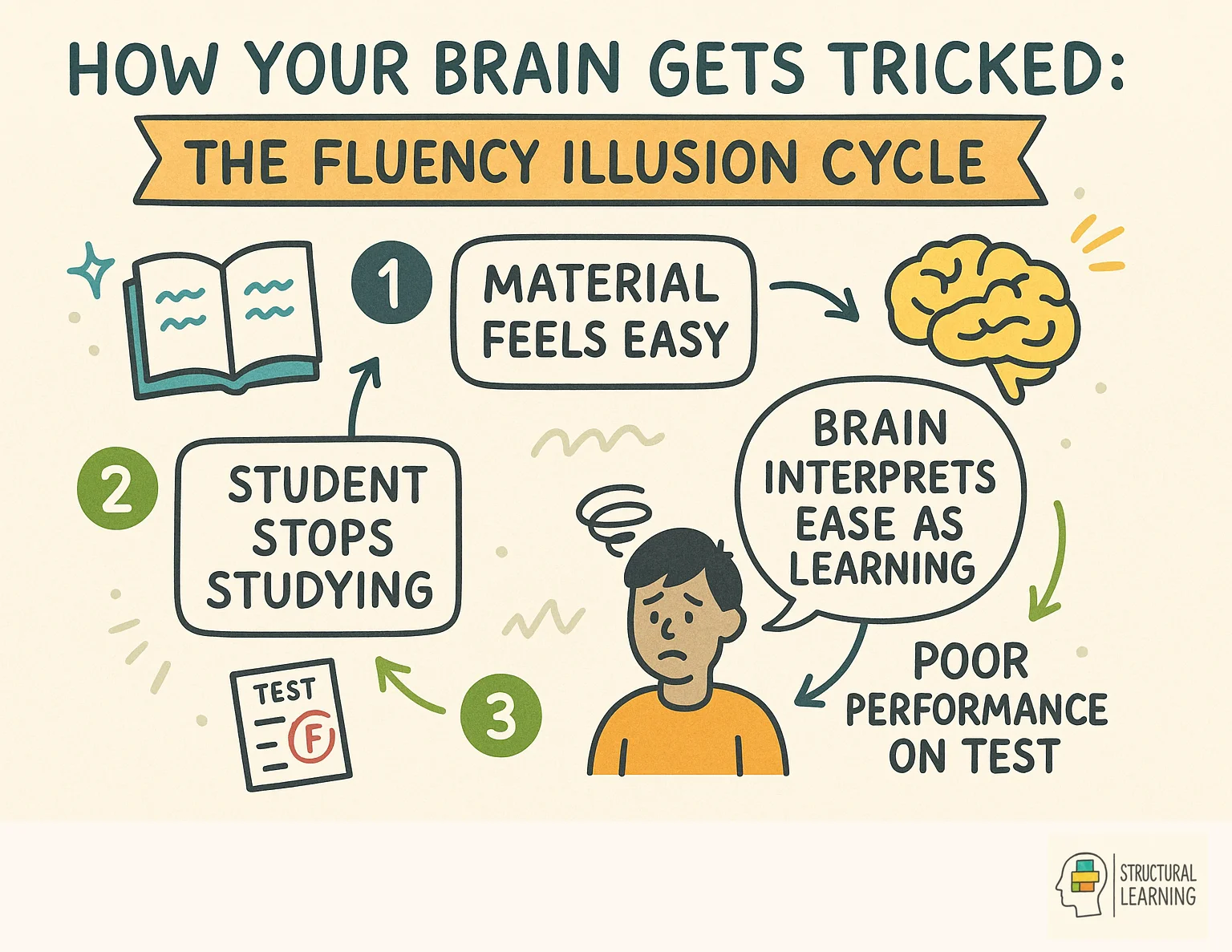

The psychological mechanisms behind these misjudgments are now well understood. Fluency illusions, also called illusions of competence or illusions of knowing, occur when the ease of processing information creates a false sense of learning. Material that feels smooth and easy to understand gets mistaken for material that has been learned. This confusion between current comprehension and future recall leads students systematically astray.

Key Takeaways

Fluency illusions occur when students mistake the ease of processing information for actual learning, leading them to overestimate what they'll remember later. This happens because material that feels smooth and familiar during study creates false confidence about future recall ability. Students experiencing fluency illusions believe they know material better than they actually do, causing poor study decisions.

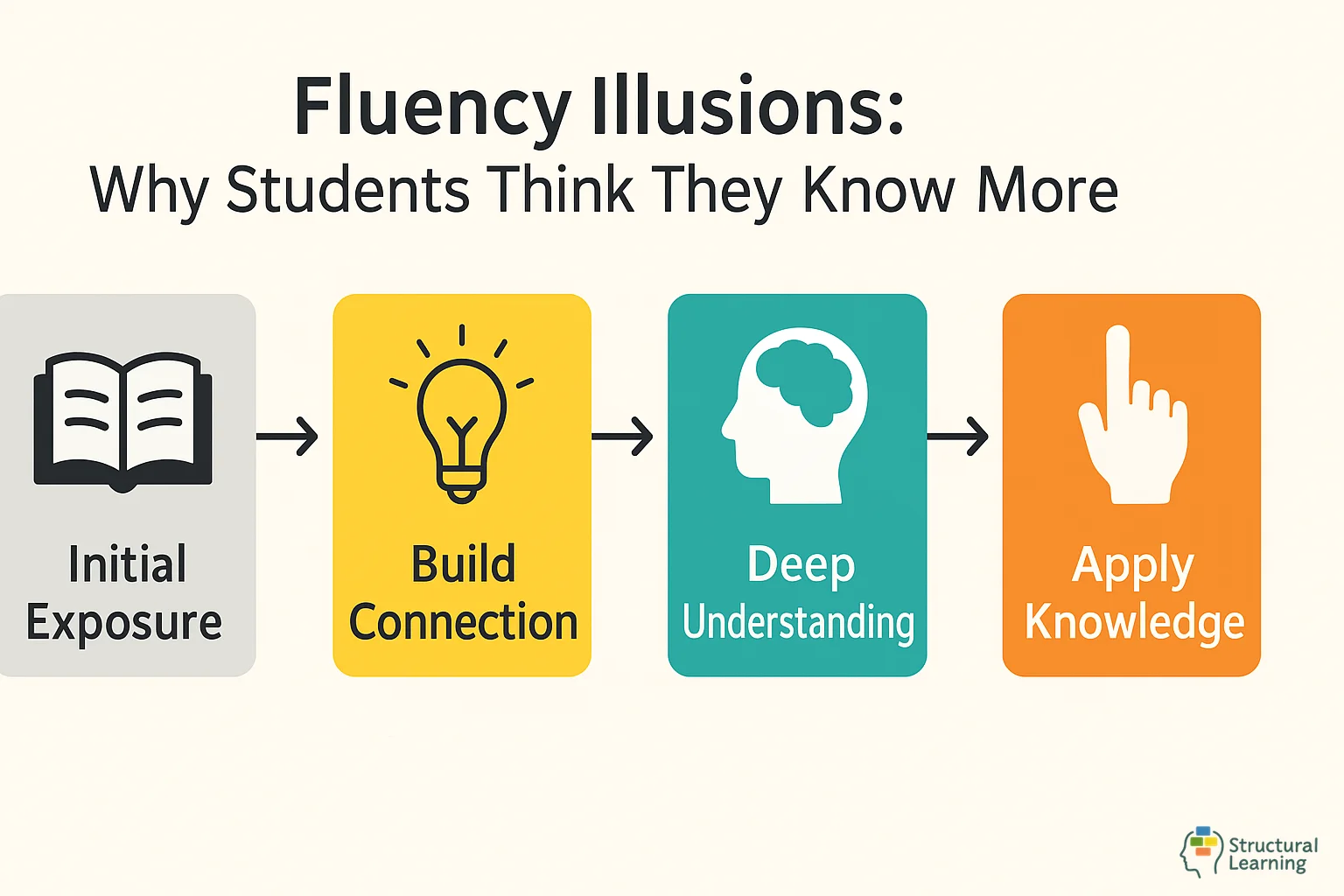

Processing fluency refers to the subjective ease with which information is perceived, understood, or retrieved. When you read a sentence in a clear font, it feels more fluent than the same sentence in a difficult-to-read typeface. When you recognise a familiar face, that recognition feels fluent compared to trying to identify someone you've met only once.

The brain uses fluency as a cue for many judgments. Fluent processing generally signals familiarity, truth, and liking. Statements that are easier to process are rated as more likely to be true. Products with pronounceable names are preferred over those with unpronounceable names. These effects occur automatically, below conscious awareness.

In learning contexts, fluency creates particular problems. When students re-read a textbook chapter, the material becomes increasingly fluent with each pass. Sentences that initially required effort to parse now flow smoothly. This fluency feels like understanding, like learning has occurred. But fluency during study predicts recognition in the moment, not recall in the future. The student can smoothly process the material while it's in front of them but may be unable to retrieve it when the book is closed.

Asher Koriat and Robert Bjork's influential research at UCLA demonstrated this phenomenon clearly. In their studies, participants learned word pairs and made predictions about how well they would remember them. Pairs that were easy to process during study, such as those with obvious semantic relationships, received high predictions. Yet on actual recall tests, these easy-to-encode pairs were often poorly remembered. The fluency of encoding misled judgments about future retrieval.

Students misjudge their learning because the brain confuses current comprehension with future recall ability, a metacognitive error driven by processing fluency. When information feels easy to understand in the moment, students assume they'll remember it later, but ease of processing doesn't guarantee retention. This systematic bias leads students to stop studying too early and focus on the wrong material.

Understanding fluency illusions requires grasping how metacognition operates. Metacognition refers to thinking about thinking, our ability to monitor and regulate our own cognitive processes. Effective learning depends on accurate metacognition: knowing what you know, identifying what you don't know, and adjusting study strategies accordingly.

When metacognitive judgments are accurate, students allocate study time wisely, focus on material that needs attention, and stop studying when they've genuinely mastered content. When judgments are inaccurate, students waste time on already-learned material, neglect material that needs work, and stop studying prematurely.

Judgments of learning (JOLs) are predictions about future memory performance. When students rate how well they'll remember something, they're making JOLs. Research consistently shows that JOLs are heavily influenced by processing fluency, even when fluency doesn't predict actual recall.

The problem intensifies because students often lack awareness of these biases. They believe their sense of knowing is accurate. When told they performed poorly despite feeling prepared, students often attribute the failure to unfair test questions or bad luck rather than recognising their metacognitive error.

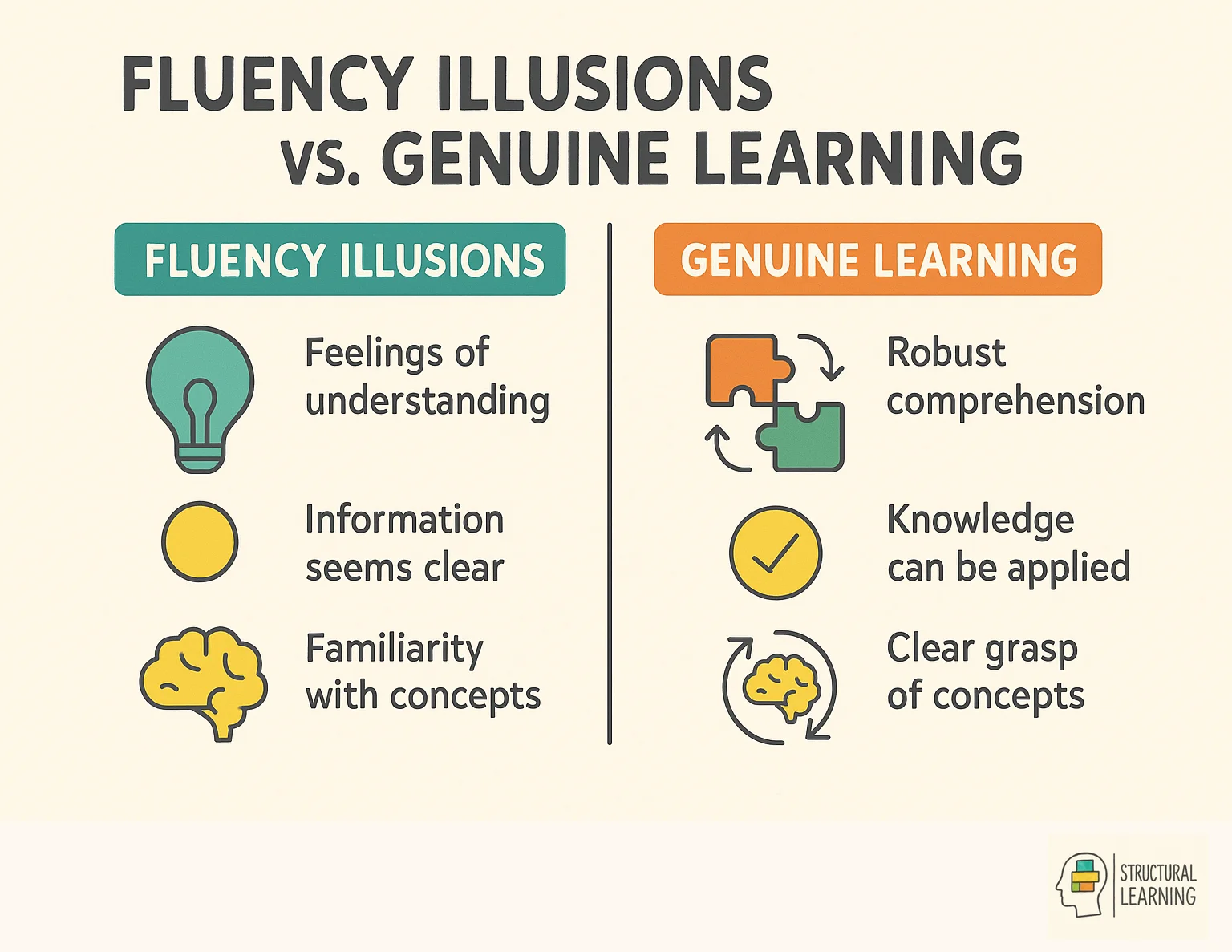

Re-reading creates strong fluency illusions because repeated exposure makes text feel increasingly familiar without building retrieval strength. Students mistake this growing familiarity for learning, when they're actually just recognising words they've seen before rather than encoding meaning. Research shows re-reading produces minimal learning gains compared to active recall strategies.

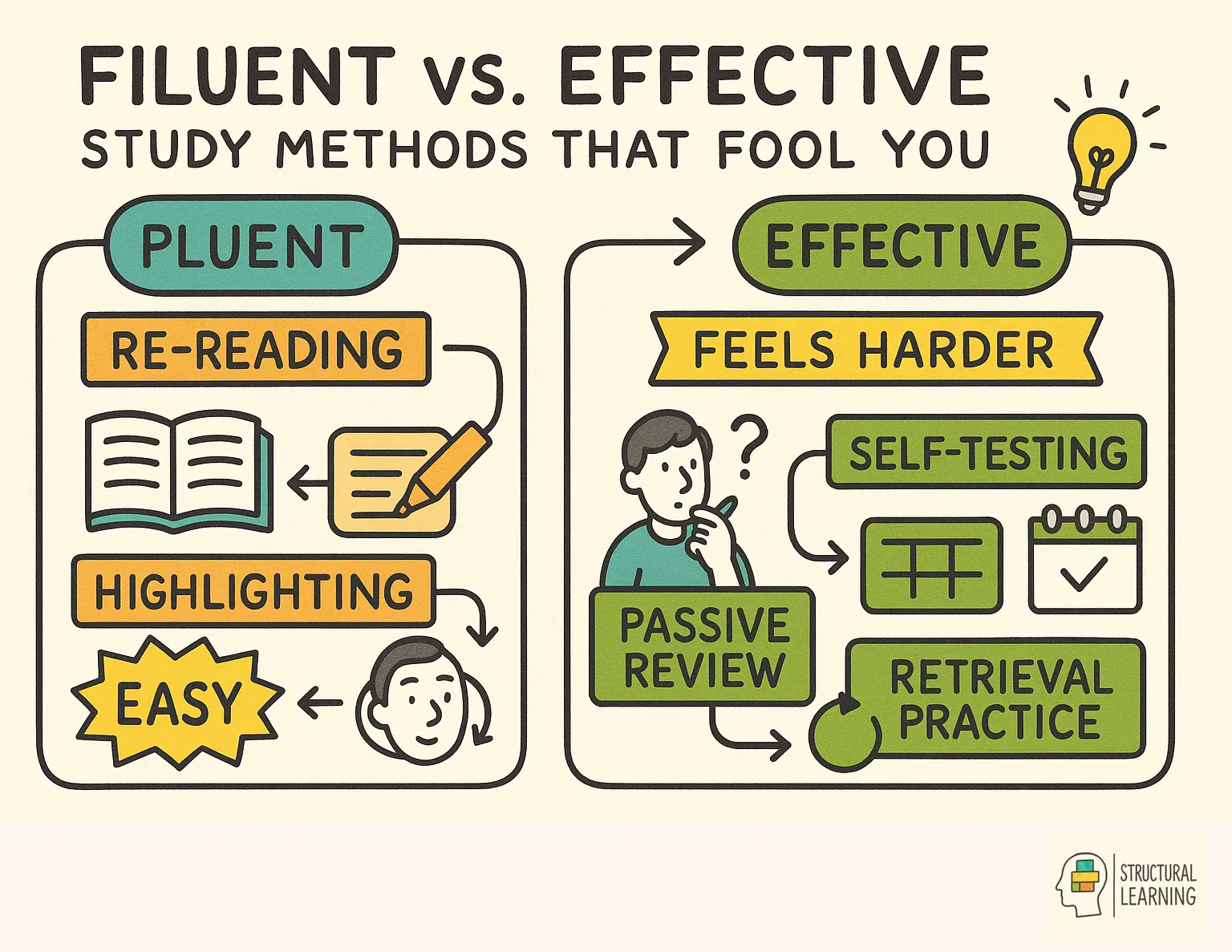

Re-reading is among the most popular study strategies, and among the least effective. Surveys consistently show that students favour re-reading over more effortful strategies like self-testing. The popularity of re-reading likely stems from the powerful fluency illusions it generates.

Each time students re-read material, processing becomes easier. Words and sentences that required attention on first reading now flow automatically. This increasing fluency creates a compelling sense of learning. Students feel they're mastering the material because it feels increasingly comfortable.

Research by Jeffrey Karpicke and colleagues has demonstrated that re-reading produces minimal learning benefits compared to retrieval practise, despite students' preferences for re-reading and their beliefs that it works well. In one study, students who re-read material predicted they would remember 50% more than students who engaged in retrieval practise. The actual results showed the opposite: retrieval practise dramatically outperformed re-reading.

The fluency generated by re-reading represents recognition, not recall. Students can recognise material as familiar when they see it again, but this recognition doesn't translate to the ability to produce information from memory when cues are absent. Yet it's recall, not recognition, that most assessments require.

Encoding fluency refers to how easily information goes into memory during initial learning, while retrieval fluency measures how easily it comes out when needed. Students often confuse high encoding fluency (material feels easy to understand) with future retrieval success, but these are separate processes. Material that's harder to encode often produces stronger memories than material that feels easy initially.

Researchers distinguish between two types of fluency that affect metacognitive judgments.

Encoding fluency refers to the ease of initially processing and storing information. When material is presented clearly, connects to prior knowledge, or has obvious internal structure, encoding feels easy. Students learning well-organised information experience high encoding fluency.

Retrieval fluency refers to the ease of accessing information from memory. When a memory comes to mind quickly and effortlessly, retrieval is fluent. When you strain to recall something that eventually surfaces, retrieval is disfluent.

Both types of fluency influence metacognitive judgments, but they can point in different directions. Information that was easy to encode may be difficult to retrieve later. Information that required effort to encode may be easily retrieved.

The critical insight is that retrieval conditions at test often differ dramatically from encoding conditions during study. During study, the information is present; during testing, it must be generated from memory. Fluency during study doesn't guarantee fluency during test, but students often assume it does.

Benjamin, Bjork, and Schwartz's research coined the term "mismeasure of memory" to describe situations where retrieval fluency at one time predicts poor memory at a later time. Items that come to mind quickly during immediate testing may be poorly remembered on delayed tests, while items that require more effort initially may be more durably stored.

Fluency illusions manifest when students claim they studied hard but fail tests, insist they understand material during lessons but can't apply it later, or rely heavily on re-reading and highlighting. Teachers often see students reviewing notes passively, avoiding practise problems because the material already feels familiar, or expressing surprise at poor test performance. These behaviours indicate students are mistaking recognition for recall ability.

Fluency illusions manifest in predictable ways in educational settings.

Students often highlight or underline text while reading, believing this active engagement enhances learning. Research suggests highlighting provides minimal benefit and may create fluency illusions. The highlighted passages become visually distinctive on subsequent reading, creating false confidence. Students recognise their highlights and feel they know the material.

In mathematics and science, students frequently study worked examples. When solutions are laid out step by step, following along feels easy. Students understand each step as they read it. But understanding a solution someone else produced differs fundamentally from generating a solution oneself. The fluency of following along doesn't translate to the ability to solve similar problems independently. This connects to challenges with mathematical understanding.

Students who attend lectures and follow along may experience high fluency as the instructor explains concepts. The explanation makes sense in the moment. But when students attempt to reconstruct that understanding on their own, they discover gaps and confusions that weren't apparent while the instructor was filling in the details.

Study groups can create fluency illusions when stronger students do most of the explaining. Weaker students nod along, understanding the explanations in the moment, and leave feeling confident. But they've engaged in recognition, not recall. They understood when information was provided but can't generate it independently.

Foresight bias occurs when students overestimate how well they'll remember information in the future based on how easy it feels to understand right now. Students looking at their notes before a test cannot imagine not knowing the answers, creating unrealistic confidence about their preparation. This bias is strongest when students have study materials in front of them, making it hard to simulate actual testing conditions.

Koriat and Bjork identified a specific metacognitive error they termed the "foresight bias." During study, learners have access to information that won't be available at test. They must discount this information when predicting future recall but often fail to do so adequately.

Consider learning the word pair "bread-butter." During study, seeing both words together, the association seems obvious and memorable. Both words are present; their connection is visible. Students predict high recall. But at test, only "bread" appears, and students must generate "butter" from memory. The presence of both words during study created fluency that won't exist at test.

The foresight bias explains why students overpredict memory for obviously related pairs but underpredict for unrelated pairs. The obvious relationship creates fluency during study, but this fluency doesn't help at test when the target word is absent.

Effective study methods like self-testing and spaced practise feel harder because they introduce desirable difficulties that slow down initial learning but improve retention. Students avoid these methods because the struggle feels like failure, when it actually signals deeper processing and stronger memory formation. The methods that feel easiest produce the weakest learning, while challenging strategies that feel ineffective produce the best results.

Robert Bjork's concept of desirable difficulties identifies learning conditions that reduce current performance but enhance long-term retention. These include spacing practise over time, interleaving different topics, and testing rather than restudying.

Desirable difficulties feel harder because they are harder in the moment. Spaced practise feels less smooth than massed practise. Interleaved practise feels more confusing than blocked practise. Testing feels more effortful than restudying. This difficulty creates disfluency.

The cruel irony is that the strategies producing the weakest fluency often produce the strongest learning, while strategies producing the strongest fluency often produce the weakest learning. Students' preferences, guided by fluency, lead them towards ineffective strategies and away from effective ones.

When students space their practise and experience difficulty retrieving information from earlier sessions, they may conclude they're learning poorly. They might switch to massed practise, which feels more effective because material remains fresh and retrieval is fluent. In doing so, they sacrifice long-term learning for short-term comfort.

Students can overcome fluency illusions by using self-testing without looking at notes, spacing out practise sessions, and teaching material to others. The key is replacing passive review with active retrieval practise that reveals what they actually know versus what merely feels familiar. Regular low-stakes quizzing helps students calibrate their self-assessments to match their true knowledge level.

Fortunately, research identifies approaches that can improve metacognitive accuracy and reduce fluency illusions.

Judgments of learning made immediately after studying are heavily influenced by encoding fluency and tend to be poorly calibrated. Judgments made after a delay, when encoding fluency has dissipated, prove more accurate.

Thomas Nelson and John Dunlosky discovered that delaying JOLs until some time after study dramatically improves their predictive validity. When students wait before judging their learning, they're forced to actually retrieve information rather than judge based on the ease of just having processed it.

Teachers can encourage delayed judgment by asking students to predict their test performance not at the end of a study session but at a later time, perhaps the next day.

Testing oneself provides direct evidence of what one can and cannot retrieve. Unlike re-reading, which always feels successful because the material is present, self-testing reveals gaps in knowledge. When students attempt to recall information and fail, their metacognitive judgments become more accurate.

Self-testing also produces the testing effect: the act of retrieving information strengthens memory for that information. So self-testing simultaneously improves learning and improves awareness of learning.

Generating information rather than reading itprovided reduces fluency illusions. When students must produce rather than recognise, they gain accurate AI-enhanced feedback about what they know. Active learning strategies that require generation force students to confront the limits of their knowledge.

Teaching students about fluency illusions can help them recognise and correct their own metacognitive errors. When students understand that fluency doesn't equal learning, they can deliberately override their intuitions.

This metacognitive training is particularly valuable because it addresses the root cause of poor study choices. Students don't choose ineffective strategies because they're lazy or uninformed about better strategies. They choose ineffective strategies because those strategies create illusions of effectiveness. Breaking the illusion requires understanding its source.

Teachers should explicitly teach students about fluency illusions and build frequent retrieval practise into lessons through quizzes, cold calling, and problem sets. Explaining why difficult practise feels hard but works better helps students persist with challenging strategies. Teachers can model accurate self-assessment by having students predict quiz scores before taking them, then comparing predictions to actual results.

Teachers can structure their instruction and assessment to reduce fluency illusions and promote accurate self-assessment.

Design learning activities that introduce productive challenges. Space practise over time. Interleave topics rather than blocking by type. Require retrieval rather than recognition. These approaches produce less fluent but more durable learning.

Students may initially resist these approaches because they feel harder. Explaining the research on desirable difficulties can help students understand why the difficulty is productive.

Regular quizzes and retrieval opportunities serve dual purposes: they enhance learning through the testing effect, and they provide accurate feedback that calibrates metacognition. Students who test themselves frequently develop more realistic assessments of what they know.

When students perform poorly despite confidence, explicitly address the metacognitive error. "You felt prepared, but your performance suggests your sense of knowing wasn't accurate. Let's discuss why that might have happened." This feedback helps students recognise the fluency trap.

Show students how to test themselves effectively. Provide practise questions, encourage creation of flashcards, and teach techniques like the blank page method (writing down everything you can remember about a topic). These memorisation strategies provide the self-assessment opportunities students need.

Homework that requires retrieval from memory provides better metacognitive calibration than homework that allows students to look everything up. Consider including some questions students must attempt before consulting their notes.

Student beliefs about effective learning strongly influence susceptibility to fluency illusions, with those believing in passive strategies more likely to fall prey to false confidence. Students who think learning should feel easy abandon effective strategies when they encounter difficulty, while those who expect challenge persist longer. Teaching students that struggle indicates learning, not failure, helps them make better study choices.

Fluency illusions interact with students' beliefs about learning. Students who believe learning should feel easy may interpret difficulty as evidence of failure rather than productive struggle. These beliefs compound fluency illusions by encouraging avoidance of beneficial difficulties.

Addressing mindsets about effort and struggle can support better metacognition. When students understand that difficulty often signals effective learning, they're less likely to interpret disfluency as failure and more likely to persist through productive challenges. This connects to attribution theory and how students explain their successes and failures.

Carol Dweck's research on growth mindset suggests that students who believe abilities can be developed through effort are more likely to embrace challenges. These students may be less susceptible to fluency illusions because they don't expect learning to always feel easy.

Some students naturally possess stronger metacognitive accuracy due to factors like prior experience with self-testing, higher working memory capacity, and explicit instruction in self-monitoring. Students with learning differences may experience stronger fluency illusions because compensatory strategies can mask knowledge gaps during study. Teaching metacognitive skills explicitly helps all students, but especially benefits those who struggle with accurate self-assessment.

Not all students are equally susceptible to fluency illusions. Research identifies several factors that influence metacognitive accuracy.

Experts in a domain tend to have more accurate metacognition within that domain. Their extensive knowledge provides better benchmarks for judging new learning. They know what it feels like to truly understand something versus merely recognising it.

Novices, lacking these benchmarks, are more susceptible to fluency illusions. The smooth processing they experience may be their first encounter with certain material, leaving them no basis for comparison.

Students differ in their general metacognitive abilities. Some students naturally monitor their learning more accurately than others. These differences may stem from prior experiences, instruction, or cognitive characteristics.

Importantly, metacognitive skills can be taught. Students with initially poor metacognition can improve through instruction and practise.

Younger students tend to have poorer metacognition than older students. Children's metacognitive abilities develop throughout childhood and adolescence. Teachers of younger students should be particularly attentive to providing external feedback since students may not yet have developed reliable internal monitoring.

Digital learning environmentscan amplify fluency illusions through features like immediate access to answers, multimedia presentations that feel engaging but lack depth, and the ability to pause and replay content. Students watching educational videos often experience strong illusions of learning because the content feels clear and well-explained in the moment. Online platforms need built-in retrieval practise and self-testing to counteract these digital fluency traps.

Digital learning environments may exacerbate fluency illusions in several ways.

Online courses often allow easy access to materials, enabling repeated re-reading that generates fluency without learning. The ability to quickly search for information may reduce the perceived need for genuine learning, since students can always look things up.

Video lectures can create powerful comprehension illusions. Following along with a clear explanation feels easy and productive. Students may need explicit guidance to pause videos and test themselves rather than passively watching.

However, digital environments also offer opportunities for combating illusions. Built-in quizzes, spaced review systems, and retrieval practise tools can provide the self-testing that calibrates metacognition.

Fluency illusions in group settings occur when smooth discussions create false confidence about collective understanding, with members assuming others' apparent comprehension reflects deep knowledge. Groups can combat this by assigning rotating roles for questioning and summarising, ensuring each member demonstrates individual understanding. Structured protocols like think-pair-share force individual retrieval before group discussion, reducing collective fluency illusions.

Fluency illusions affect not only individual study but also collaborative learning and classroom interactions.

When teachers explain concepts clearly, students experience fluency as they follow along. This fluency may create false confidence that persists until assessment reveals gaps. Teachers might deliberately introduce productive confusion or require students to generate explanations themselves rather than simply receiving clear ones.

In classroom discussions, students who can follow others' reasoning may believe they could produce similar reasoning themselves. Teachers can check this by calling on students to extend, apply, or replicate reasoning rather than simply agreeing with it.

Key foundational papers include Bjork's work on desirable difficulties, Dunlosky's research on study strategies, and Koriat's studies on metacognitive illusions. The book 'Make It Stick' by Brown, Roediger, and McDaniel translates this research into practical classroom applications. Current research focuses on digital learning environments and individual differences in metacognitive monitoring accuracy.

Research on fluency illusions bridges metacognition, memory, and educational psychology. These foundational papers offer deeper exploration of the phenomenon and its implications.

This landmark paper demonstrated how the presence of information during study creates fluency that misleads judgments about future recall. Using paired-associate learning, Koriat and Bjork showed that participants dramatically overestimated their memory for items that were easy to process during study but absent during retrieval. The paper introduced the concept of foresight bias and established the core theoretical framework for understanding fluency illusions.

This research demonstrated that retrieval fluency at one time point can actively mislead predictions about memory at later time points. Items retrieved quickly on immediate tests were often poorly remembered on delayed tests, yet participants predicted the opposite. The paper illuminates how the cues people use to judge their learning can systematically lead them astray.

This paper examined how accurately students predict their performance on reading comprehension tests. The researchers found generally poor accuracy, with students failing to distinguish well-understood from poorly understood material. The findings have direct implications for study behaviour, as students cannot effectively allocate study time without accurate self-assessment.

This study examined why students prefer restudying over retrieval practise despite the superior effectiveness of retrieval. The researchers found that students base their preferences on immediate performance feedback rather than long-term learning. Restudying feels more successful because it produces fluency, leading students to choose strategies that feel good over strategies that work.

This follow-up paper examined how to reduce fluency illusions. The researchers found that conditions forcing learners to rely on retrieval fluency rather than encoding fluency improved metacognitive accuracy. The paper offers practical implications for designing study conditions that support accurate self-assessment.

---

Key research: Karpicke & Roediger (2008) demonstrated in Science that students who practiced retrieval significantly outperformed those who restudied, despite the restudying group's higher confidence in their learning, a striking illustration of fluency illusions.

For UK practitioners, the Chartered College of Teaching provides evidence-based resources on metacognition. The Learning Scientists offer free classroom resources on combating fluency illusions through retrieval practise.

When students process information easily, their brains interpret this ease as mastery. This misinterpretation stems from metacognitive monitoring, our ability to assess our own learning. Research by Bjork and Bjork (2011) shows that we rely on processing fluency, how smoothly information flows through our minds, as a proxy for learning. The smoother the processing, the more confident we become about our knowledge, regardless of whether we could actually retrieve that information later.

This psychological trap affects all learners because our brains naturally seek efficiency. When Year 10 students re-read their biology notes for the third time, the familiar words and concepts flow effortlessly. Their metacognitive system incorrectly signals 'mission accomplished', even though they might struggle to define photosynthesis without their notes. The same mechanism explains why students feel confident after watching revision videos; passive consumption feels deceptively productive.

Teachers can help students recognise these false signals by making the distinction visible. Try this classroom demonstration: show students a completed maths problem, then ask them to rate their ability to solve similar problems. Next, present a blank problem of the same type. The gap between their confidence ratings and actual performance illustrates fluency illusions perfectly. Another effective strategy involves 'delayed judgements of learning'; ask students to predict their test performance immediately after studying, then again the next day. The overnight drop in confidence often matches reality more closely, teaching students that immediate feelings of knowing are unreliable guides to actual learning.

When students review their notes or re-read textbook chapters, the material feels increasingly familiar and comfortable. This growing ease creates a powerful psychological experience: the content seems obvious, almost predictable. Students report thinking 'of course I know this' as their eyes glide effortlessly across previously studied pages. The brain interprets this smooth processing as evidence of mastery, when it merely signals recognition.

Consider what happens during a typical revision session. A Year 10 student preparing for a history exam reads through their notes on the causes of World War One. The second time through, everything makes perfect sense; the connections feel clear and the facts seem memorable. The student closes their notebook, confident they've learnt the material. Yet when faced with an essay question requiring them to analyse these causes, their mind goes blank. The fluency of reading created an illusion that dissolved under the pressure of production.

This phenomenon intensifies with repeated exposure. Each additional reading makes the material feel more familiar, strengthening the illusion whilst adding little to actual retention. Students often describe the shock of exam day: 'I knew it all when I was revising, but I couldn't remember anything when I needed to write it down.' They're describing the collapse of a fluency illusion, not a failure of effort.

Teachers can help students recognise these experiences. Ask them to predict their test scores immediately after studying, then compare these predictions to actual results. Most will discover they consistently overestimate their performance. This metacognitive awareness, though initially uncomfortable, helps students understand why challenging study methods that feel difficult actually work better than comfortable ones that create false confidence.

Fluency illusions occur when students mistake the ease of processing information for actual learning, leading them to overestimate what they'll remember later. This causes students to make poor study decisions, such as stopping revision too early or focusing on the wrong material, ultimately resulting in disappointing assessment performance despite genuine confidence.

Teachers can introduce frequent low-stakes testing and self-assessment opportunities to help students calibrate their actual knowledge against their perceived understanding. By explaining the concept of fluency illusions directly and showing studentshow familiar material doesn't equal mastered material, educators can help develop more accurate metacognitive awareness.

Re-reading creates powerful fluency illusions because repeated exposure makes text feel increasingly familiar, which students mistake for genuine learning. Research shows that whilst students who re-read material predict they'll remember 50% more than those using retrieval practise, the actual results demonstrate the opposite, with retrieval practise dramatically outperforming re-reading.

Teachers should encourage active recall strategies such as self-testing, explaining concepts aloud without notes, and spaced practise sessions. These methods feel more difficult than passive re-reading but produce stronger, more durable learning and help students develop more accurate judgements about their knowledge.

Parents can ask their children to explain topics without looking at their notes or textbooks, and encourage them to test themselves regularly rather than simply re-reading material. When children claim they 'know it all' after brief revision, parents can gently challenge this by asking specific questions or requesting demonstrations of the knowledge.

Recognition involves identifying familiar information when you see it again (like re-reading notes), whilst recall requires producing information from memory without cues. Most assessments require recall rather than recognition, which explains why students who feel confident after re-reading often struggle in exams that demand active retrieval of knowledge.

Teachers can incorporate regular retrieval practise into lessons, use spaced repetition of key concepts, and avoid over-relying on highlighting or passive review activiti es. Setting homework that requires students to generate answers rather than simply read material will help build genuine understanding whilst providing more accurate feedback about learning progress.

These peer-reviewed studies provide the research foundation for the strategies discussed in this article:

DISFLUENCY IN ENGLISH LANGUAGE TEACHING? View study ↗

1 citations

Laura Buechel (2020)

This study tested whether making learning slightly more difficult on purpose, such as using a harder-to-read font called Sans Forgetica, actually helps students learn better. The research with 72 preservice teachers explores the counterintuitive idea that when materials feel too easy to read, students may develop false confidence about their understanding. Teachers can apply this by strategically introducing productive challenges that force deeper processing rather than letting students coast on surface-level familiarity.

A Data-Driven Analysis of Cognitive Learning and Illusion Effects in University Mathematics View study ↗

Rodolfo Bojorque et al. (2025)

This current study reveals how video-based instruction and digital learning tools can trick students into thinking they understand math concepts better than they actually do. When learning feels smooth and effortless through polished videos or self-paced digital materials, students often mistake this fluency for genuine comprehension. The research provides crucial insights for educators using technology, showing why regular assessment and reflection are essential to combat these learning illusions.

The Illusion of Knowing in College: A Field Study of Students with a Teacher-Centred Educational Past View study ↗

10 citations

M. Pilotti et al. (2019)

Students who grew up with traditional, memorization-heavy teaching methods consistently overestimate how well they'll perform on tests and in class. The study found that having students predict their performance and then reflect on the gaps between predictions and actual results helps break this overconfidence cycle. This research highlights why teachers need to help students develop realistic self-assessment skills, especially when transitioning from passive learning environments to more demanding academic settings.

Re-examining the testing effect as a learning strategy: the advantage of retrieval practise over concept mapping as a methodological artifact View study ↗

3 citations

Roland Mayrhofer et al. (2023)

This important study challenges previous research that seemed to show retrieval practise (like flashcards or practise tests) was superior to concept mapping for learning. The researchers discovered that earlier studies had an unfair comparison because students doing concept maps weren't given time to actually memorize the information afterwards. For teachers, this means both retrieval practise and concept mapping can be valuable tools, and the key is ensuring students have adequate time to process information regardless of the learning method used.

Metacognitive illusion or self-regulated learning? Assessing engineering students' learning strategies against the backdrop of recent advances in cognitive science View study ↗

35 citations

Maria Cervin-Ellqvist et al. (2020)

Engineering students often believe they're using effective study strategies when they're actually relying on methods that create illusions of learning rather than deep understanding. However, the study also found that some students do successfully self-regulate their learning by adapting their strategies based on what actually works. This research emphasizes the importance of teaching students how to evaluate the effectiveness of their own study methods and providing explicit instruction in evidence-based learning strategies.

Every teacher has witnessed the disconnect: a student insists they've studied thoroughly, yet performs poorly on the assessment. The student isn't lying or making excuses. They genuinely believed they knew the material. This gap between perceived and actual knowledge represents one of the most significant obstacles to effective learning. When students can't accurately judge what they know, they make poor decisions about how to study, when to stop studying, and which material needs more attention and how to transfer knowledge effectively.

The psychological mechanisms behind these misjudgments are now well understood. Fluency illusions, also called illusions of competence or illusions of knowing, occur when the ease of processing information creates a false sense of learning. Material that feels smooth and easy to understand gets mistaken for material that has been learned. This confusion between current comprehension and future recall leads students systematically astray.

Key Takeaways

Fluency illusions occur when students mistake the ease of processing information for actual learning, leading them to overestimate what they'll remember later. This happens because material that feels smooth and familiar during study creates false confidence about future recall ability. Students experiencing fluency illusions believe they know material better than they actually do, causing poor study decisions.

Processing fluency refers to the subjective ease with which information is perceived, understood, or retrieved. When you read a sentence in a clear font, it feels more fluent than the same sentence in a difficult-to-read typeface. When you recognise a familiar face, that recognition feels fluent compared to trying to identify someone you've met only once.

The brain uses fluency as a cue for many judgments. Fluent processing generally signals familiarity, truth, and liking. Statements that are easier to process are rated as more likely to be true. Products with pronounceable names are preferred over those with unpronounceable names. These effects occur automatically, below conscious awareness.

In learning contexts, fluency creates particular problems. When students re-read a textbook chapter, the material becomes increasingly fluent with each pass. Sentences that initially required effort to parse now flow smoothly. This fluency feels like understanding, like learning has occurred. But fluency during study predicts recognition in the moment, not recall in the future. The student can smoothly process the material while it's in front of them but may be unable to retrieve it when the book is closed.

Asher Koriat and Robert Bjork's influential research at UCLA demonstrated this phenomenon clearly. In their studies, participants learned word pairs and made predictions about how well they would remember them. Pairs that were easy to process during study, such as those with obvious semantic relationships, received high predictions. Yet on actual recall tests, these easy-to-encode pairs were often poorly remembered. The fluency of encoding misled judgments about future retrieval.

Students misjudge their learning because the brain confuses current comprehension with future recall ability, a metacognitive error driven by processing fluency. When information feels easy to understand in the moment, students assume they'll remember it later, but ease of processing doesn't guarantee retention. This systematic bias leads students to stop studying too early and focus on the wrong material.

Understanding fluency illusions requires grasping how metacognition operates. Metacognition refers to thinking about thinking, our ability to monitor and regulate our own cognitive processes. Effective learning depends on accurate metacognition: knowing what you know, identifying what you don't know, and adjusting study strategies accordingly.

When metacognitive judgments are accurate, students allocate study time wisely, focus on material that needs attention, and stop studying when they've genuinely mastered content. When judgments are inaccurate, students waste time on already-learned material, neglect material that needs work, and stop studying prematurely.

Judgments of learning (JOLs) are predictions about future memory performance. When students rate how well they'll remember something, they're making JOLs. Research consistently shows that JOLs are heavily influenced by processing fluency, even when fluency doesn't predict actual recall.

The problem intensifies because students often lack awareness of these biases. They believe their sense of knowing is accurate. When told they performed poorly despite feeling prepared, students often attribute the failure to unfair test questions or bad luck rather than recognising their metacognitive error.

Re-reading creates strong fluency illusions because repeated exposure makes text feel increasingly familiar without building retrieval strength. Students mistake this growing familiarity for learning, when they're actually just recognising words they've seen before rather than encoding meaning. Research shows re-reading produces minimal learning gains compared to active recall strategies.

Re-reading is among the most popular study strategies, and among the least effective. Surveys consistently show that students favour re-reading over more effortful strategies like self-testing. The popularity of re-reading likely stems from the powerful fluency illusions it generates.

Each time students re-read material, processing becomes easier. Words and sentences that required attention on first reading now flow automatically. This increasing fluency creates a compelling sense of learning. Students feel they're mastering the material because it feels increasingly comfortable.

Research by Jeffrey Karpicke and colleagues has demonstrated that re-reading produces minimal learning benefits compared to retrieval practise, despite students' preferences for re-reading and their beliefs that it works well. In one study, students who re-read material predicted they would remember 50% more than students who engaged in retrieval practise. The actual results showed the opposite: retrieval practise dramatically outperformed re-reading.

The fluency generated by re-reading represents recognition, not recall. Students can recognise material as familiar when they see it again, but this recognition doesn't translate to the ability to produce information from memory when cues are absent. Yet it's recall, not recognition, that most assessments require.

Encoding fluency refers to how easily information goes into memory during initial learning, while retrieval fluency measures how easily it comes out when needed. Students often confuse high encoding fluency (material feels easy to understand) with future retrieval success, but these are separate processes. Material that's harder to encode often produces stronger memories than material that feels easy initially.

Researchers distinguish between two types of fluency that affect metacognitive judgments.

Encoding fluency refers to the ease of initially processing and storing information. When material is presented clearly, connects to prior knowledge, or has obvious internal structure, encoding feels easy. Students learning well-organised information experience high encoding fluency.

Retrieval fluency refers to the ease of accessing information from memory. When a memory comes to mind quickly and effortlessly, retrieval is fluent. When you strain to recall something that eventually surfaces, retrieval is disfluent.

Both types of fluency influence metacognitive judgments, but they can point in different directions. Information that was easy to encode may be difficult to retrieve later. Information that required effort to encode may be easily retrieved.

The critical insight is that retrieval conditions at test often differ dramatically from encoding conditions during study. During study, the information is present; during testing, it must be generated from memory. Fluency during study doesn't guarantee fluency during test, but students often assume it does.

Benjamin, Bjork, and Schwartz's research coined the term "mismeasure of memory" to describe situations where retrieval fluency at one time predicts poor memory at a later time. Items that come to mind quickly during immediate testing may be poorly remembered on delayed tests, while items that require more effort initially may be more durably stored.

Fluency illusions manifest when students claim they studied hard but fail tests, insist they understand material during lessons but can't apply it later, or rely heavily on re-reading and highlighting. Teachers often see students reviewing notes passively, avoiding practise problems because the material already feels familiar, or expressing surprise at poor test performance. These behaviours indicate students are mistaking recognition for recall ability.

Fluency illusions manifest in predictable ways in educational settings.

Students often highlight or underline text while reading, believing this active engagement enhances learning. Research suggests highlighting provides minimal benefit and may create fluency illusions. The highlighted passages become visually distinctive on subsequent reading, creating false confidence. Students recognise their highlights and feel they know the material.

In mathematics and science, students frequently study worked examples. When solutions are laid out step by step, following along feels easy. Students understand each step as they read it. But understanding a solution someone else produced differs fundamentally from generating a solution oneself. The fluency of following along doesn't translate to the ability to solve similar problems independently. This connects to challenges with mathematical understanding.

Students who attend lectures and follow along may experience high fluency as the instructor explains concepts. The explanation makes sense in the moment. But when students attempt to reconstruct that understanding on their own, they discover gaps and confusions that weren't apparent while the instructor was filling in the details.

Study groups can create fluency illusions when stronger students do most of the explaining. Weaker students nod along, understanding the explanations in the moment, and leave feeling confident. But they've engaged in recognition, not recall. They understood when information was provided but can't generate it independently.

Foresight bias occurs when students overestimate how well they'll remember information in the future based on how easy it feels to understand right now. Students looking at their notes before a test cannot imagine not knowing the answers, creating unrealistic confidence about their preparation. This bias is strongest when students have study materials in front of them, making it hard to simulate actual testing conditions.

Koriat and Bjork identified a specific metacognitive error they termed the "foresight bias." During study, learners have access to information that won't be available at test. They must discount this information when predicting future recall but often fail to do so adequately.

Consider learning the word pair "bread-butter." During study, seeing both words together, the association seems obvious and memorable. Both words are present; their connection is visible. Students predict high recall. But at test, only "bread" appears, and students must generate "butter" from memory. The presence of both words during study created fluency that won't exist at test.

The foresight bias explains why students overpredict memory for obviously related pairs but underpredict for unrelated pairs. The obvious relationship creates fluency during study, but this fluency doesn't help at test when the target word is absent.

Effective study methods like self-testing and spaced practise feel harder because they introduce desirable difficulties that slow down initial learning but improve retention. Students avoid these methods because the struggle feels like failure, when it actually signals deeper processing and stronger memory formation. The methods that feel easiest produce the weakest learning, while challenging strategies that feel ineffective produce the best results.

Robert Bjork's concept of desirable difficulties identifies learning conditions that reduce current performance but enhance long-term retention. These include spacing practise over time, interleaving different topics, and testing rather than restudying.

Desirable difficulties feel harder because they are harder in the moment. Spaced practise feels less smooth than massed practise. Interleaved practise feels more confusing than blocked practise. Testing feels more effortful than restudying. This difficulty creates disfluency.

The cruel irony is that the strategies producing the weakest fluency often produce the strongest learning, while strategies producing the strongest fluency often produce the weakest learning. Students' preferences, guided by fluency, lead them towards ineffective strategies and away from effective ones.

When students space their practise and experience difficulty retrieving information from earlier sessions, they may conclude they're learning poorly. They might switch to massed practise, which feels more effective because material remains fresh and retrieval is fluent. In doing so, they sacrifice long-term learning for short-term comfort.

Students can overcome fluency illusions by using self-testing without looking at notes, spacing out practise sessions, and teaching material to others. The key is replacing passive review with active retrieval practise that reveals what they actually know versus what merely feels familiar. Regular low-stakes quizzing helps students calibrate their self-assessments to match their true knowledge level.

Fortunately, research identifies approaches that can improve metacognitive accuracy and reduce fluency illusions.

Judgments of learning made immediately after studying are heavily influenced by encoding fluency and tend to be poorly calibrated. Judgments made after a delay, when encoding fluency has dissipated, prove more accurate.

Thomas Nelson and John Dunlosky discovered that delaying JOLs until some time after study dramatically improves their predictive validity. When students wait before judging their learning, they're forced to actually retrieve information rather than judge based on the ease of just having processed it.

Teachers can encourage delayed judgment by asking students to predict their test performance not at the end of a study session but at a later time, perhaps the next day.

Testing oneself provides direct evidence of what one can and cannot retrieve. Unlike re-reading, which always feels successful because the material is present, self-testing reveals gaps in knowledge. When students attempt to recall information and fail, their metacognitive judgments become more accurate.

Self-testing also produces the testing effect: the act of retrieving information strengthens memory for that information. So self-testing simultaneously improves learning and improves awareness of learning.

Generating information rather than reading itprovided reduces fluency illusions. When students must produce rather than recognise, they gain accurate AI-enhanced feedback about what they know. Active learning strategies that require generation force students to confront the limits of their knowledge.

Teaching students about fluency illusions can help them recognise and correct their own metacognitive errors. When students understand that fluency doesn't equal learning, they can deliberately override their intuitions.

This metacognitive training is particularly valuable because it addresses the root cause of poor study choices. Students don't choose ineffective strategies because they're lazy or uninformed about better strategies. They choose ineffective strategies because those strategies create illusions of effectiveness. Breaking the illusion requires understanding its source.

Teachers should explicitly teach students about fluency illusions and build frequent retrieval practise into lessons through quizzes, cold calling, and problem sets. Explaining why difficult practise feels hard but works better helps students persist with challenging strategies. Teachers can model accurate self-assessment by having students predict quiz scores before taking them, then comparing predictions to actual results.

Teachers can structure their instruction and assessment to reduce fluency illusions and promote accurate self-assessment.

Design learning activities that introduce productive challenges. Space practise over time. Interleave topics rather than blocking by type. Require retrieval rather than recognition. These approaches produce less fluent but more durable learning.

Students may initially resist these approaches because they feel harder. Explaining the research on desirable difficulties can help students understand why the difficulty is productive.

Regular quizzes and retrieval opportunities serve dual purposes: they enhance learning through the testing effect, and they provide accurate feedback that calibrates metacognition. Students who test themselves frequently develop more realistic assessments of what they know.

When students perform poorly despite confidence, explicitly address the metacognitive error. "You felt prepared, but your performance suggests your sense of knowing wasn't accurate. Let's discuss why that might have happened." This feedback helps students recognise the fluency trap.

Show students how to test themselves effectively. Provide practise questions, encourage creation of flashcards, and teach techniques like the blank page method (writing down everything you can remember about a topic). These memorisation strategies provide the self-assessment opportunities students need.

Homework that requires retrieval from memory provides better metacognitive calibration than homework that allows students to look everything up. Consider including some questions students must attempt before consulting their notes.

Student beliefs about effective learning strongly influence susceptibility to fluency illusions, with those believing in passive strategies more likely to fall prey to false confidence. Students who think learning should feel easy abandon effective strategies when they encounter difficulty, while those who expect challenge persist longer. Teaching students that struggle indicates learning, not failure, helps them make better study choices.

Fluency illusions interact with students' beliefs about learning. Students who believe learning should feel easy may interpret difficulty as evidence of failure rather than productive struggle. These beliefs compound fluency illusions by encouraging avoidance of beneficial difficulties.

Addressing mindsets about effort and struggle can support better metacognition. When students understand that difficulty often signals effective learning, they're less likely to interpret disfluency as failure and more likely to persist through productive challenges. This connects to attribution theory and how students explain their successes and failures.

Carol Dweck's research on growth mindset suggests that students who believe abilities can be developed through effort are more likely to embrace challenges. These students may be less susceptible to fluency illusions because they don't expect learning to always feel easy.

Some students naturally possess stronger metacognitive accuracy due to factors like prior experience with self-testing, higher working memory capacity, and explicit instruction in self-monitoring. Students with learning differences may experience stronger fluency illusions because compensatory strategies can mask knowledge gaps during study. Teaching metacognitive skills explicitly helps all students, but especially benefits those who struggle with accurate self-assessment.

Not all students are equally susceptible to fluency illusions. Research identifies several factors that influence metacognitive accuracy.

Experts in a domain tend to have more accurate metacognition within that domain. Their extensive knowledge provides better benchmarks for judging new learning. They know what it feels like to truly understand something versus merely recognising it.

Novices, lacking these benchmarks, are more susceptible to fluency illusions. The smooth processing they experience may be their first encounter with certain material, leaving them no basis for comparison.

Students differ in their general metacognitive abilities. Some students naturally monitor their learning more accurately than others. These differences may stem from prior experiences, instruction, or cognitive characteristics.

Importantly, metacognitive skills can be taught. Students with initially poor metacognition can improve through instruction and practise.

Younger students tend to have poorer metacognition than older students. Children's metacognitive abilities develop throughout childhood and adolescence. Teachers of younger students should be particularly attentive to providing external feedback since students may not yet have developed reliable internal monitoring.

Digital learning environmentscan amplify fluency illusions through features like immediate access to answers, multimedia presentations that feel engaging but lack depth, and the ability to pause and replay content. Students watching educational videos often experience strong illusions of learning because the content feels clear and well-explained in the moment. Online platforms need built-in retrieval practise and self-testing to counteract these digital fluency traps.

Digital learning environments may exacerbate fluency illusions in several ways.

Online courses often allow easy access to materials, enabling repeated re-reading that generates fluency without learning. The ability to quickly search for information may reduce the perceived need for genuine learning, since students can always look things up.

Video lectures can create powerful comprehension illusions. Following along with a clear explanation feels easy and productive. Students may need explicit guidance to pause videos and test themselves rather than passively watching.

However, digital environments also offer opportunities for combating illusions. Built-in quizzes, spaced review systems, and retrieval practise tools can provide the self-testing that calibrates metacognition.

Fluency illusions in group settings occur when smooth discussions create false confidence about collective understanding, with members assuming others' apparent comprehension reflects deep knowledge. Groups can combat this by assigning rotating roles for questioning and summarising, ensuring each member demonstrates individual understanding. Structured protocols like think-pair-share force individual retrieval before group discussion, reducing collective fluency illusions.

Fluency illusions affect not only individual study but also collaborative learning and classroom interactions.

When teachers explain concepts clearly, students experience fluency as they follow along. This fluency may create false confidence that persists until assessment reveals gaps. Teachers might deliberately introduce productive confusion or require students to generate explanations themselves rather than simply receiving clear ones.

In classroom discussions, students who can follow others' reasoning may believe they could produce similar reasoning themselves. Teachers can check this by calling on students to extend, apply, or replicate reasoning rather than simply agreeing with it.

Key foundational papers include Bjork's work on desirable difficulties, Dunlosky's research on study strategies, and Koriat's studies on metacognitive illusions. The book 'Make It Stick' by Brown, Roediger, and McDaniel translates this research into practical classroom applications. Current research focuses on digital learning environments and individual differences in metacognitive monitoring accuracy.

Research on fluency illusions bridges metacognition, memory, and educational psychology. These foundational papers offer deeper exploration of the phenomenon and its implications.

This landmark paper demonstrated how the presence of information during study creates fluency that misleads judgments about future recall. Using paired-associate learning, Koriat and Bjork showed that participants dramatically overestimated their memory for items that were easy to process during study but absent during retrieval. The paper introduced the concept of foresight bias and established the core theoretical framework for understanding fluency illusions.

This research demonstrated that retrieval fluency at one time point can actively mislead predictions about memory at later time points. Items retrieved quickly on immediate tests were often poorly remembered on delayed tests, yet participants predicted the opposite. The paper illuminates how the cues people use to judge their learning can systematically lead them astray.

This paper examined how accurately students predict their performance on reading comprehension tests. The researchers found generally poor accuracy, with students failing to distinguish well-understood from poorly understood material. The findings have direct implications for study behaviour, as students cannot effectively allocate study time without accurate self-assessment.

This study examined why students prefer restudying over retrieval practise despite the superior effectiveness of retrieval. The researchers found that students base their preferences on immediate performance feedback rather than long-term learning. Restudying feels more successful because it produces fluency, leading students to choose strategies that feel good over strategies that work.

This follow-up paper examined how to reduce fluency illusions. The researchers found that conditions forcing learners to rely on retrieval fluency rather than encoding fluency improved metacognitive accuracy. The paper offers practical implications for designing study conditions that support accurate self-assessment.

---

Key research: Karpicke & Roediger (2008) demonstrated in Science that students who practiced retrieval significantly outperformed those who restudied, despite the restudying group's higher confidence in their learning, a striking illustration of fluency illusions.

For UK practitioners, the Chartered College of Teaching provides evidence-based resources on metacognition. The Learning Scientists offer free classroom resources on combating fluency illusions through retrieval practise.

When students process information easily, their brains interpret this ease as mastery. This misinterpretation stems from metacognitive monitoring, our ability to assess our own learning. Research by Bjork and Bjork (2011) shows that we rely on processing fluency, how smoothly information flows through our minds, as a proxy for learning. The smoother the processing, the more confident we become about our knowledge, regardless of whether we could actually retrieve that information later.

This psychological trap affects all learners because our brains naturally seek efficiency. When Year 10 students re-read their biology notes for the third time, the familiar words and concepts flow effortlessly. Their metacognitive system incorrectly signals 'mission accomplished', even though they might struggle to define photosynthesis without their notes. The same mechanism explains why students feel confident after watching revision videos; passive consumption feels deceptively productive.

Teachers can help students recognise these false signals by making the distinction visible. Try this classroom demonstration: show students a completed maths problem, then ask them to rate their ability to solve similar problems. Next, present a blank problem of the same type. The gap between their confidence ratings and actual performance illustrates fluency illusions perfectly. Another effective strategy involves 'delayed judgements of learning'; ask students to predict their test performance immediately after studying, then again the next day. The overnight drop in confidence often matches reality more closely, teaching students that immediate feelings of knowing are unreliable guides to actual learning.

When students review their notes or re-read textbook chapters, the material feels increasingly familiar and comfortable. This growing ease creates a powerful psychological experience: the content seems obvious, almost predictable. Students report thinking 'of course I know this' as their eyes glide effortlessly across previously studied pages. The brain interprets this smooth processing as evidence of mastery, when it merely signals recognition.

Consider what happens during a typical revision session. A Year 10 student preparing for a history exam reads through their notes on the causes of World War One. The second time through, everything makes perfect sense; the connections feel clear and the facts seem memorable. The student closes their notebook, confident they've learnt the material. Yet when faced with an essay question requiring them to analyse these causes, their mind goes blank. The fluency of reading created an illusion that dissolved under the pressure of production.

This phenomenon intensifies with repeated exposure. Each additional reading makes the material feel more familiar, strengthening the illusion whilst adding little to actual retention. Students often describe the shock of exam day: 'I knew it all when I was revising, but I couldn't remember anything when I needed to write it down.' They're describing the collapse of a fluency illusion, not a failure of effort.

Teachers can help students recognise these experiences. Ask them to predict their test scores immediately after studying, then compare these predictions to actual results. Most will discover they consistently overestimate their performance. This metacognitive awareness, though initially uncomfortable, helps students understand why challenging study methods that feel difficult actually work better than comfortable ones that create false confidence.

Fluency illusions occur when students mistake the ease of processing information for actual learning, leading them to overestimate what they'll remember later. This causes students to make poor study decisions, such as stopping revision too early or focusing on the wrong material, ultimately resulting in disappointing assessment performance despite genuine confidence.

Teachers can introduce frequent low-stakes testing and self-assessment opportunities to help students calibrate their actual knowledge against their perceived understanding. By explaining the concept of fluency illusions directly and showing studentshow familiar material doesn't equal mastered material, educators can help develop more accurate metacognitive awareness.

Re-reading creates powerful fluency illusions because repeated exposure makes text feel increasingly familiar, which students mistake for genuine learning. Research shows that whilst students who re-read material predict they'll remember 50% more than those using retrieval practise, the actual results demonstrate the opposite, with retrieval practise dramatically outperforming re-reading.

Teachers should encourage active recall strategies such as self-testing, explaining concepts aloud without notes, and spaced practise sessions. These methods feel more difficult than passive re-reading but produce stronger, more durable learning and help students develop more accurate judgements about their knowledge.

Parents can ask their children to explain topics without looking at their notes or textbooks, and encourage them to test themselves regularly rather than simply re-reading material. When children claim they 'know it all' after brief revision, parents can gently challenge this by asking specific questions or requesting demonstrations of the knowledge.

Recognition involves identifying familiar information when you see it again (like re-reading notes), whilst recall requires producing information from memory without cues. Most assessments require recall rather than recognition, which explains why students who feel confident after re-reading often struggle in exams that demand active retrieval of knowledge.

Teachers can incorporate regular retrieval practise into lessons, use spaced repetition of key concepts, and avoid over-relying on highlighting or passive review activiti es. Setting homework that requires students to generate answers rather than simply read material will help build genuine understanding whilst providing more accurate feedback about learning progress.

These peer-reviewed studies provide the research foundation for the strategies discussed in this article:

DISFLUENCY IN ENGLISH LANGUAGE TEACHING? View study ↗

1 citations

Laura Buechel (2020)

This study tested whether making learning slightly more difficult on purpose, such as using a harder-to-read font called Sans Forgetica, actually helps students learn better. The research with 72 preservice teachers explores the counterintuitive idea that when materials feel too easy to read, students may develop false confidence about their understanding. Teachers can apply this by strategically introducing productive challenges that force deeper processing rather than letting students coast on surface-level familiarity.

A Data-Driven Analysis of Cognitive Learning and Illusion Effects in University Mathematics View study ↗

Rodolfo Bojorque et al. (2025)

This current study reveals how video-based instruction and digital learning tools can trick students into thinking they understand math concepts better than they actually do. When learning feels smooth and effortless through polished videos or self-paced digital materials, students often mistake this fluency for genuine comprehension. The research provides crucial insights for educators using technology, showing why regular assessment and reflection are essential to combat these learning illusions.

The Illusion of Knowing in College: A Field Study of Students with a Teacher-Centred Educational Past View study ↗

10 citations

M. Pilotti et al. (2019)

Students who grew up with traditional, memorization-heavy teaching methods consistently overestimate how well they'll perform on tests and in class. The study found that having students predict their performance and then reflect on the gaps between predictions and actual results helps break this overconfidence cycle. This research highlights why teachers need to help students develop realistic self-assessment skills, especially when transitioning from passive learning environments to more demanding academic settings.

Re-examining the testing effect as a learning strategy: the advantage of retrieval practise over concept mapping as a methodological artifact View study ↗

3 citations

Roland Mayrhofer et al. (2023)

This important study challenges previous research that seemed to show retrieval practise (like flashcards or practise tests) was superior to concept mapping for learning. The researchers discovered that earlier studies had an unfair comparison because students doing concept maps weren't given time to actually memorize the information afterwards. For teachers, this means both retrieval practise and concept mapping can be valuable tools, and the key is ensuring students have adequate time to process information regardless of the learning method used.

Metacognitive illusion or self-regulated learning? Assessing engineering students' learning strategies against the backdrop of recent advances in cognitive science View study ↗

35 citations

Maria Cervin-Ellqvist et al. (2020)

Engineering students often believe they're using effective study strategies when they're actually relying on methods that create illusions of learning rather than deep understanding. However, the study also found that some students do successfully self-regulate their learning by adapting their strategies based on what actually works. This research emphasizes the importance of teaching students how to evaluate the effectiveness of their own study methods and providing explicit instruction in evidence-based learning strategies.

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/fluency-illusions-students-think-they-know#article","headline":"Fluency Illusions: Why Students Think They Know More Than They Do","description":"Fluency illusions cause students to overestimate their learning when material feels easy to process, leading to poor study choices and unexpected exam failures.","datePublished":"2025-12-29T18:43:16.203Z","dateModified":"2026-02-11T13:17:46.939Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/fluency-illusions-students-think-they-know"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/69666b35fbbdccff517a0bae_69666b33067ddae629190bf9_fluency-illusions-students-think-they-know-infographic.webp","wordCount":6091},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/fluency-illusions-students-think-they-know#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"Fluency Illusions: Why Students Think They Know More Than They Do","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/fluency-illusions-students-think-they-know"}]}]}