Word Aware: The Complete Guide to the STAR Approach for

Implement the Word Aware STAR approach to enhance vocabulary teaching, focusing on word selection, Goldilocks words, and strategies for diverse learners.

Implement the Word Aware STAR approach to enhance vocabulary teaching, focusing on word selection, Goldilocks words, and strategies for diverse learners.

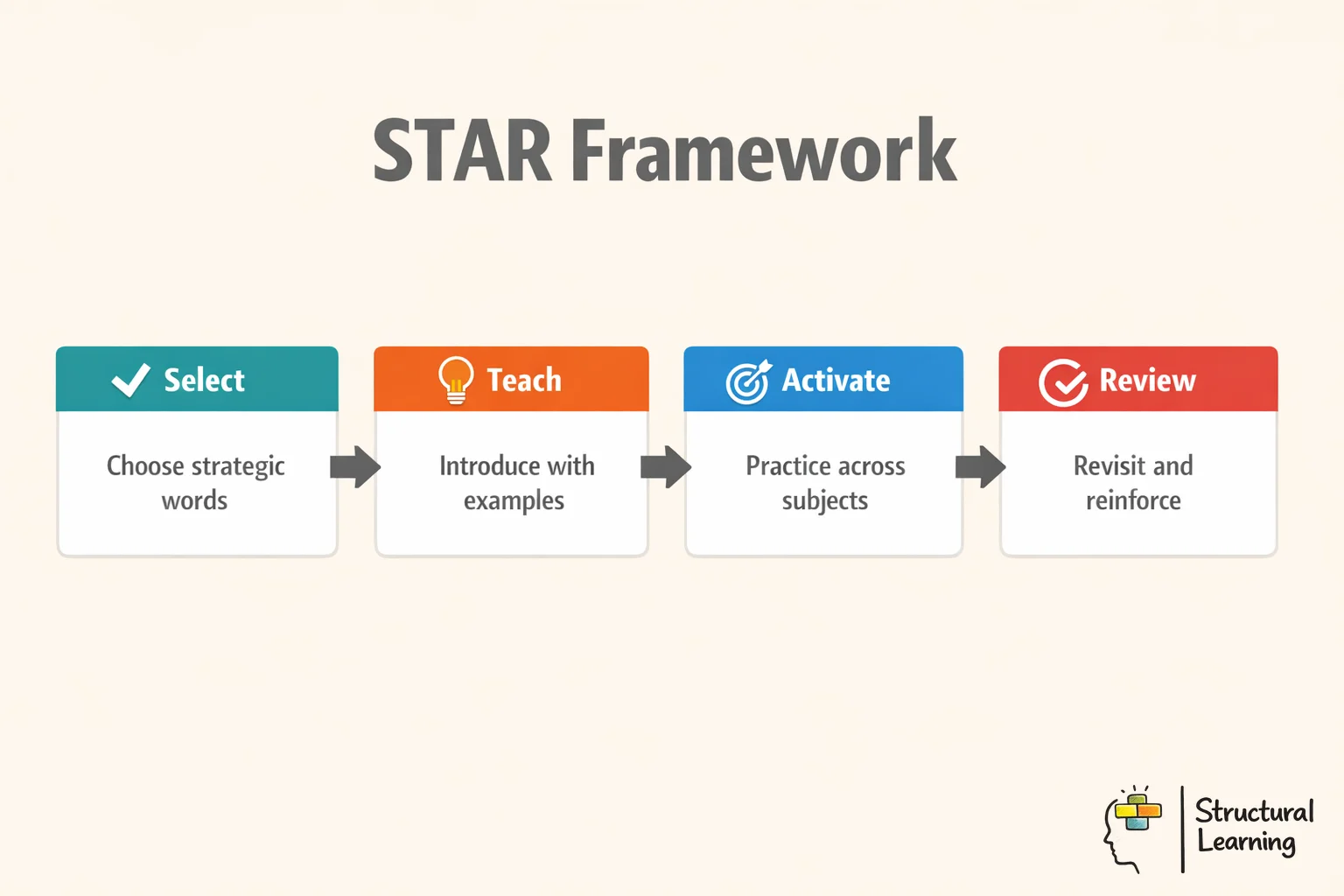

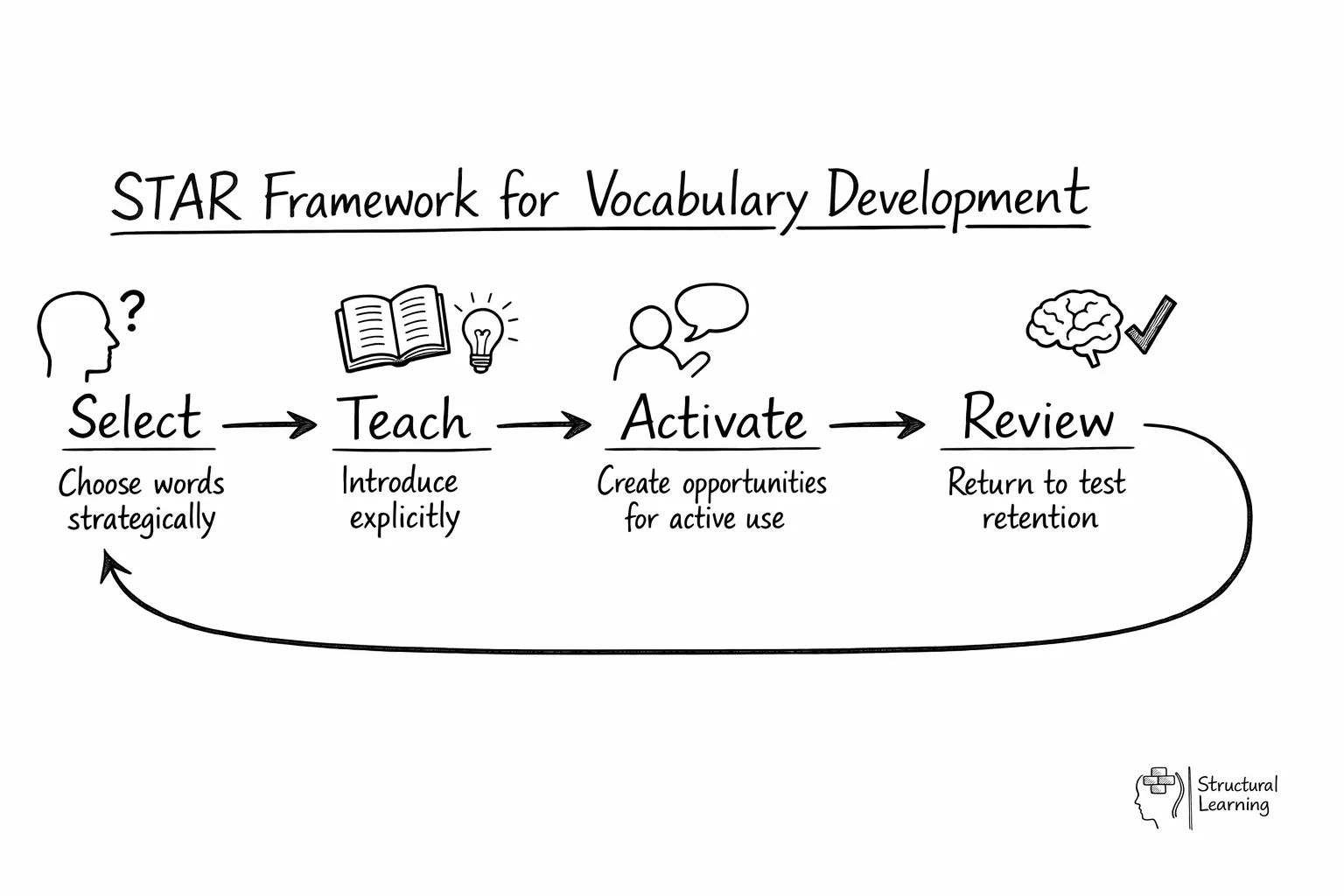

Word Aware is a research-based vocabulary programme created by speech and language therapists Anna Branagan and Stephen Parsons. The approach changes how schools teach vocabulary by moving beyond simple definitions to deep, lasting word knowledge. Through the STAR framework (Select, Teach, Activate, Review), children encounter target words in meaningful contexts across the school day, building the rich vocabulary knowledge that underpins Reading comprehension, Academic success, and communication skills.

Vocabulary knowledge at school entry is one of the strongest predictors of later academic achievement. Children from disadvantaged backgrounds often start school with much smaller vocabularies than their peers. This creates a gap that widens without direct help. Word Aware gives schools a structured, whole-school approach to vocabulary teaching. This closes the gap while helping all learners.

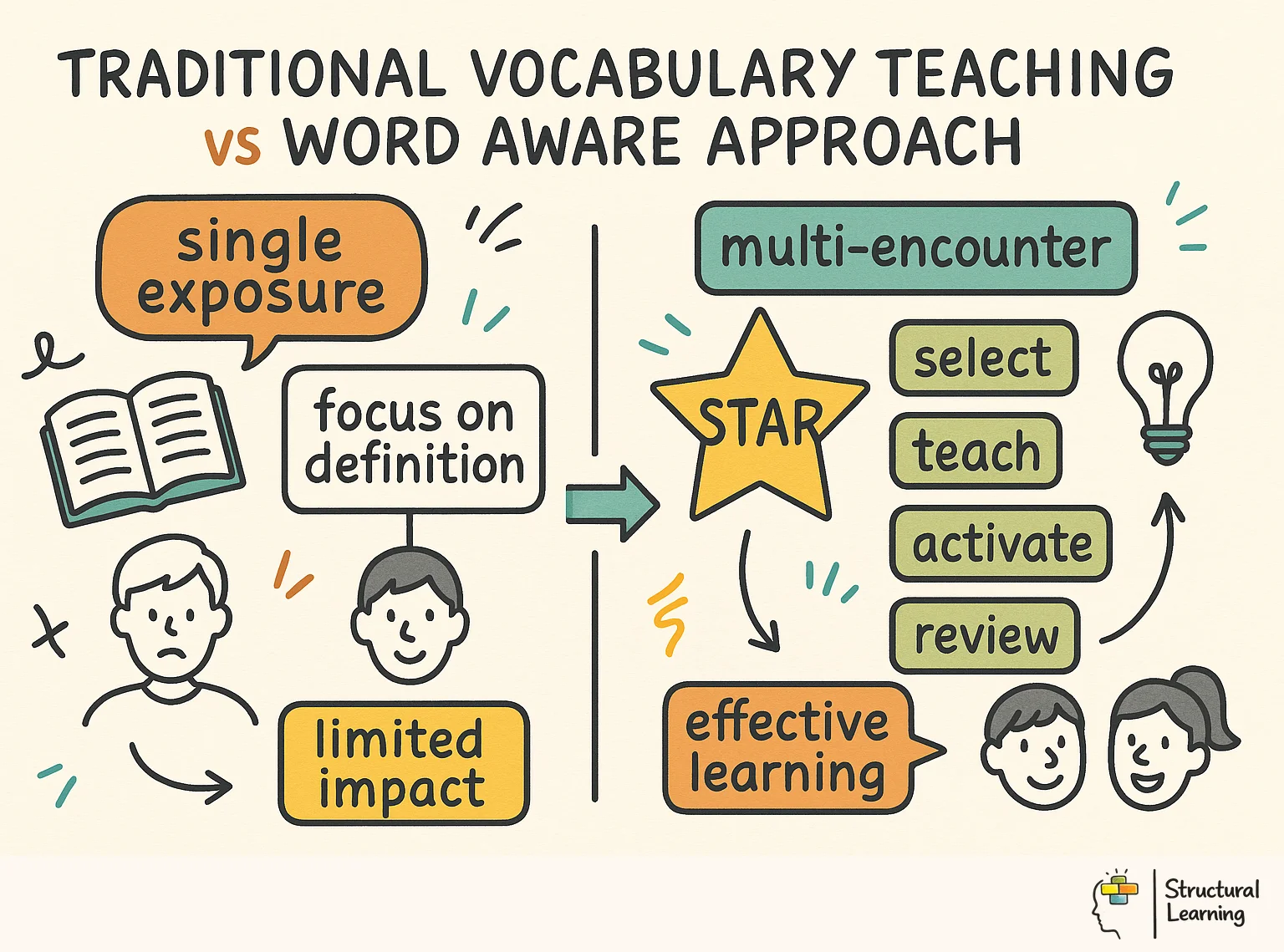

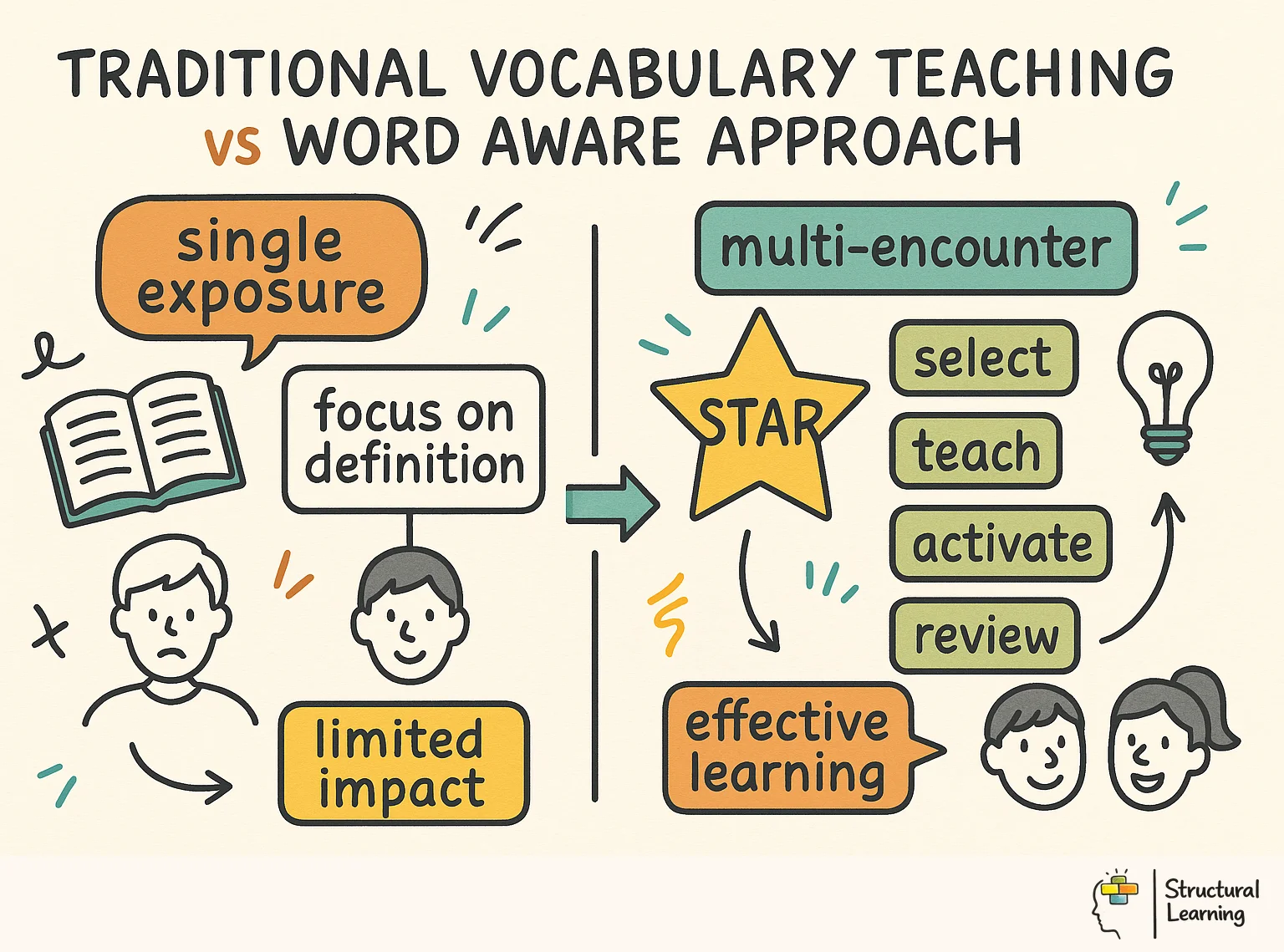

Word Aware is a whole-school vocabulary programme based on research into how children learn new words effectively. Anna Branagan and Stephen Parsons developed this approach. They are experienced speech and language therapists. They saw that traditional vocabulary teaching fails to create lasting word knowledge. This teaching usually involves definitions and single exposures.

The programme centres on the STAR framework, a four-step process for teaching vocabulary:

Select, Choose words strategically, prioritising words that children will encounter across subjects and contexts, and that are within reach of current understanding.

Teach, Introduce words explicitly using child-friendly definitions, examples, images, and connections to known concepts.

Activate: Create multiple opportunities for children to use target words actively in speaking and writing across the curriculum.

Review, Return to words regularly, testing retention and deepening understanding over time.

Word Aware differs from traditional vocabulary instruction in several important ways. Rather than teaching words in isolation, it embeds vocabulary development across the curriculum. Rather than relying on dictionary definitions, it uses child-friendly explanations with concrete examples. Rather than assuming one exposure is sufficient, it plans for twelve or more meaningful encounters with each word.

Word Aware draws on decades of vocabulary research, particularly the work of Blachowicz and Fisher (2010) on effective vocabulary instruction. Understanding this evidence helps teachers appreciate why the approach works and use it with fidelity.

The vocabulary gap is real and has serious consequences. Hart and Risley's important research made a key finding. Children from low-income families hear about 30 million fewer words by age three than children from higher-income families. Later research has debated the exact figures, but the basic finding remains true. Children enter school with very different vocabulary sizes. This gap affects their later Explicit instruction accelerates learning: Stahl and Fairbanks' meta-analysis found that explicit vocabulary instruction produces significant gains in word knowledge and reading comprehension. Results are better when teaching goes beyond definitions. It should include many contexts, meaningful use, and links to previous knowledge.

Multiple exposures are essential: Research consistently shows that single exposures to new words produce little lasting learning. Beck and McKeown suggest children need about twelve meaningful meetings with a word. This helps the word move from recognition to active use. Word Aware operationalises this finding through the STAR framework.

Context matters: Words learned in rich, meaningful contexts are retained better than words learned through rote memorisation. The approach's emphasis on activation across contexts reflects this principle.

One of Word Aware's most practical contributions is its classification of words into three tiers, helping teachers prioritise which words deserve intensive teaching.

Anchor Words are basic, high-frequency words that most children acquire through everyday language exposure. Examples include "big", "happy", "run", and "house". These words rarely need explicit teaching for typically Developing children, though they may require attention for children with language difficulties or English as an additional language. Anchor words form the foundation upon which other vocabulary builds.

Goldilocks Words are the priority targets for vocabulary instruction. These are words that are:

Examples include "fortunate", "merchant", "absurd", "coincidence", and "analyse". These words are perfect for direct teaching. Children are unlikely to learn them by chance but can understand them when taught directly. Goldilocks words significantly expand children's expressive range and reading comprehension.

Step-on Words are specialist, technical vocabulary tied to specific subjects or domains. Examples include "photosynthesis", "denominator", "peninsula", and "alliteration". These words are essential within their domains but may not transfer to other contexts. While important for subject-specific understanding, they are not the primary focus of whole-school vocabulary development.

This classification helps teachers make strategic decisions about vocabulary instruction. Rather than teaching every unknown word, teachers can focus their limited time on Goldilocks words that give the best results. Step-on words are still taught within their specific subject contexts. They are not part of whole-school vocabulary development.

The key insight is that not all words are created equal. Schools should focus systematic instruction on Goldilocks words. They should also ensure proper support for Anchor words and subject-specific teaching of Step-on words. This approach will maximise the impact of vocabulary instruction.

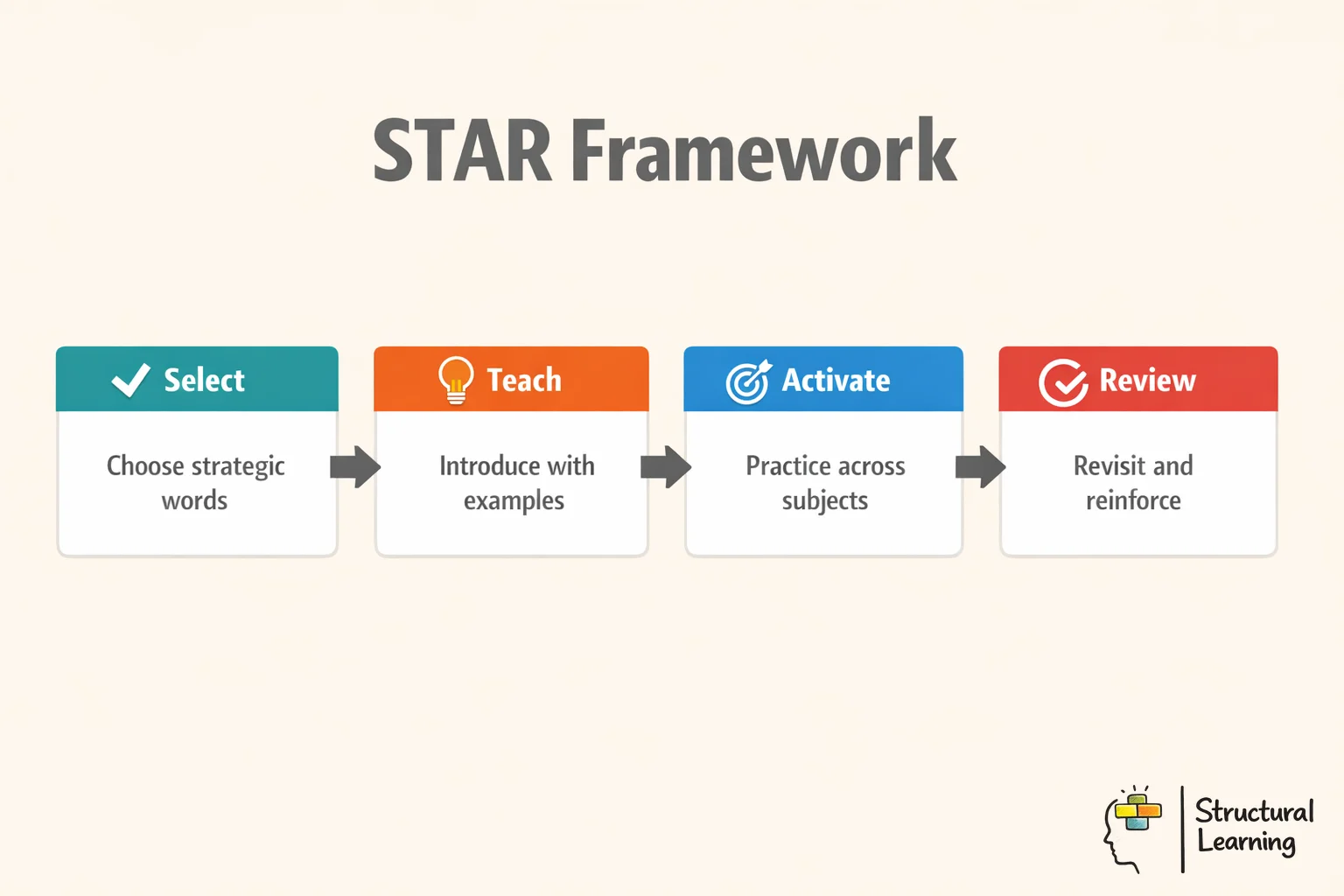

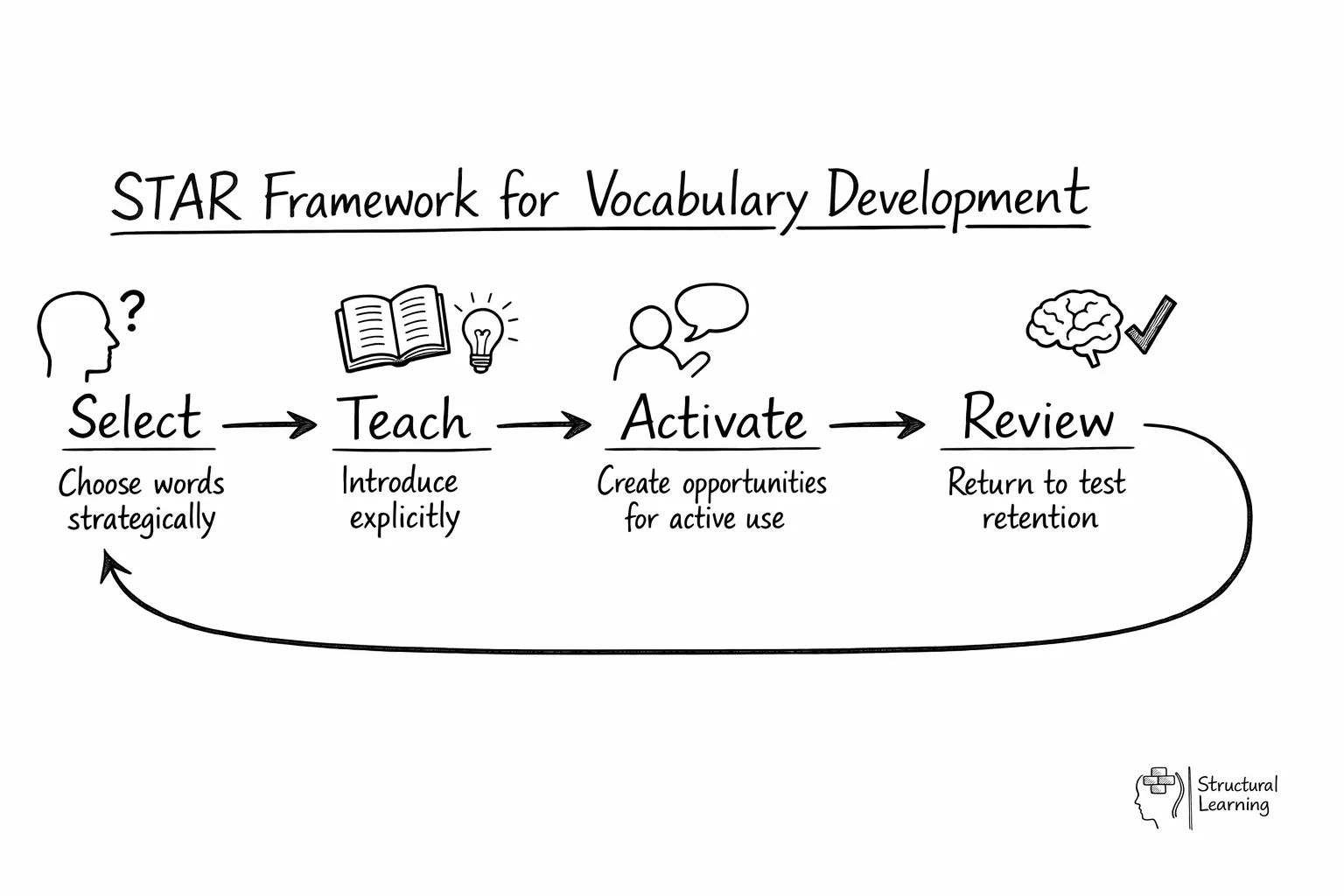

The STAR framework provides a practical structure for implementing Word Aware in classrooms. Each component serves a specific purpose in building deep word knowledge.

Select requires strategic thinking about which words to prioritise. Teachers consider the curriculum ahead, identifying words that appear across subjects and contexts. They avoid teaching every unfamiliar word. Instead, they focus on Goldilocks words that offer the best learning potential. Effective selection also considers children's prior knowledge, choosing words that stretch understanding without overwhelming learners.

Teach goes beyond simple definitions to build rich word knowledge. Teachers introduce words using child-friendly definitions that connect to known concepts. They give many examples showing the word in different contexts. They use images and gestures when helpful, and clearly discuss word relationships. The teaching phase establishes a foundation for all subsequent encounters with the word.

Activate creates opportunities for children to use target words actively. This might involve discussion activities, writing tasks, drama, or cross-curricular connections. The goal is to move beyond passive recognition to active production. Teachers plan activation opportunities across subjects, ensuring words appear in science investigations, history discussions, and creative writing.

Review ensures long-term retention through systematic revisiting. This is not simply testing whether children remember definitions, but deepening understanding through new contexts and connections. Review activities might explore synonyms and antonyms, word families, or subtle meaning differences. Regular review transforms short-Term learning into lasting vocabulary growth.

Successful Word Aware implementation requires whole-school commitment and systematic planning. Schools that achieve the greatest impact follow several key strategies.

Start with staff training: All teachers need to understand the rationale behind Word Aware and feel confident implementing the STAR framework. Training should be practical, providing opportunities to practise word selection and teaching techniques. Teachers need to see the approach modelled before implementing it themselves.

Create consistent visual displays: Word Aware walls in every classroom show target words with child-friendly definitions and images. These displays are interactive, with children encouraged to use displayed words in their spoken and written work. Consistency across classrooms reinforces the message that vocabulary development is everyone's responsibility.

Plan vocabulary across the curriculum. Rather than treating vocabulary as a separate subject, schools build word teaching into all lessons. Science teachers activate words like "observe" and "predict", while history teachers use words like "evidence" and "consequence". This cross-curricular approach dramatically increases children's exposure to target words.

Monitor and check impact: Schools track children's vocabulary growth through regular tests. They also watch how target words appear in children's independent writing. This data informs future word selection and helps teachers refine their practise.

Select the proficiency stage, first language group, and challenge area to receive tailored strategies, vocabulary targets, and progress milestones.

These peer-reviewed papers and evidence-based resources provide deeper insight into the research discussed in this article.

Bringing words to life: strong vocabulary instruction View study ↗

5678 citations

Beck, I.L., McKeown, M.G. & Kucan, L. (2013)

Beck and colleagues developed the three-tier vocabulary model that underpins Word Aware. Tier 1 (everyday words), Tier 2 (academic vocabulary), and Tier 3 (subject-specific terms) help teachers prioritise which words to teach explicitly rather than leaving vocabulary acquisition to chance.

Word Aware: Teaching vocabulary across the day, across the curriculum View study ↗

234 citations

Parsons, S. & Branagan, A. (2014)

The source text for the STAR approach (Select, Teach, Activate, Review). Parsons and Branagan combine speech and language therapy expertise with classroom practice, creating a systematic vocabulary teaching framework accessible to all teachers, not just literacy specialists.

Vocabulary and reading comprehension: A review of research View study ↗

2345 citations

Stahl, S.A. & Fairbanks, M.M. (1986)

Foundational meta-analysis showing that vocabulary instruction improves reading comprehension by an average effect size of d=0.33. Stahl and Fairbanks found that methods requiring active processing of word meanings produced larger gains than those relying on definitions alone.

Closing the vocabulary gap View study ↗

456 citations

Quigley, A. (2018)

Quigley connects the vocabulary gap to social inequality in UK schools. He provides practical strategies aligned with Word Aware principles: explicit teaching, repeated encounters, and active use in meaningful contexts. His seven-step "word instruction" model complements the STAR framework.

Why do students with good reading comprehension struggle with vocabulary? View study ↗

1234 citations

Nation, K. & Snowling, M.J. (2004)

Nation and Snowling demonstrate that vocabulary knowledge is not a unitary skill: children can decode words without understanding them. This finding supports the Word Aware emphasis on depth of word knowledge (multiple meanings, contexts, and connections) rather than breadth alone.

Word Aware is a whole-school vocabulary programme designed by speech and language therapists. The STAR approach stands for Select, Teach, Activate, and Review. It helps teachers move beyond simple dictionary definitions to build deep vocabulary knowledge through multiple meaningful encounters with words.

Teachers using this method categorise vocabulary into Anchor, Goldilocks, and Step-on words. The primary focus is on Goldilocks words, which are useful across multiple contexts and appear frequently in academic texts. Teachers introduce these words explicitly using child-friendly definitions and plan activities for students to use them actively.

The programme significantly improves reading comprehension and communication skills across the curriculum. By embedding vocabulary development into everyday lessons, it helps close the language gap for disadvantaged learners. Children move from simply recognising a word to actively using it in their own speaking and writing.

Research shows that a single exposure to a new word is rarely enough for lasting learning. Studies indicate that children need around twelve meaningful encounters with a word before they can use it confidently. Explicit instruction that includes varied contexts and links to previous knowledge produces the best academic outcomes.

A frequent mistake is relying entirely on rote memorisation and basic dictionary definitions. Teachers sometimes assume that mentioning a word once during a lesson is sufficient for children to retain it. Another common error is failing to plan structured opportunities for pupils to practise using the new words in different subjects.

Word Aware transforms vocabulary teaching from an afterthought to a systematic, evidence-based practise that benefits all children while particularly supporting those from disadvantaged backgrounds. The STAR framework gives teachers a clear structure. It moves beyond traditional methods that rely on definitions and single exposures. Schools can dramatically speed up children's vocabulary growth by carefully selecting Goldilocks words. They should teach them directly, use them in different situations, and review them regularly.

The approach's power lies in its whole-school implementation. When every teacher understands word types and uses the STAR framework, children meet target words throughout their school experience. This multiplication of meaningful encounters transforms vocabulary learning from a slow, unreliable process to rapid, systematic development. Word Aware offers a proven pathway to success. It helps schools close achievement gaps and raise standards for all children.

Vocabulary instruction research

The following research papers and publications provide deeper insights into vocabulary development and the evidence base underlying Word Aware:

Word Aware is a research-based vocabulary programme created by speech and language therapists Anna Branagan and Stephen Parsons. The approach changes how schools teach vocabulary by moving beyond simple definitions to deep, lasting word knowledge. Through the STAR framework (Select, Teach, Activate, Review), children encounter target words in meaningful contexts across the school day, building the rich vocabulary knowledge that underpins Reading comprehension, Academic success, and communication skills.

Vocabulary knowledge at school entry is one of the strongest predictors of later academic achievement. Children from disadvantaged backgrounds often start school with much smaller vocabularies than their peers. This creates a gap that widens without direct help. Word Aware gives schools a structured, whole-school approach to vocabulary teaching. This closes the gap while helping all learners.

Word Aware is a whole-school vocabulary programme based on research into how children learn new words effectively. Anna Branagan and Stephen Parsons developed this approach. They are experienced speech and language therapists. They saw that traditional vocabulary teaching fails to create lasting word knowledge. This teaching usually involves definitions and single exposures.

The programme centres on the STAR framework, a four-step process for teaching vocabulary:

Select, Choose words strategically, prioritising words that children will encounter across subjects and contexts, and that are within reach of current understanding.

Teach, Introduce words explicitly using child-friendly definitions, examples, images, and connections to known concepts.

Activate: Create multiple opportunities for children to use target words actively in speaking and writing across the curriculum.

Review, Return to words regularly, testing retention and deepening understanding over time.

Word Aware differs from traditional vocabulary instruction in several important ways. Rather than teaching words in isolation, it embeds vocabulary development across the curriculum. Rather than relying on dictionary definitions, it uses child-friendly explanations with concrete examples. Rather than assuming one exposure is sufficient, it plans for twelve or more meaningful encounters with each word.

Word Aware draws on decades of vocabulary research, particularly the work of Blachowicz and Fisher (2010) on effective vocabulary instruction. Understanding this evidence helps teachers appreciate why the approach works and use it with fidelity.

The vocabulary gap is real and has serious consequences. Hart and Risley's important research made a key finding. Children from low-income families hear about 30 million fewer words by age three than children from higher-income families. Later research has debated the exact figures, but the basic finding remains true. Children enter school with very different vocabulary sizes. This gap affects their later Explicit instruction accelerates learning: Stahl and Fairbanks' meta-analysis found that explicit vocabulary instruction produces significant gains in word knowledge and reading comprehension. Results are better when teaching goes beyond definitions. It should include many contexts, meaningful use, and links to previous knowledge.

Multiple exposures are essential: Research consistently shows that single exposures to new words produce little lasting learning. Beck and McKeown suggest children need about twelve meaningful meetings with a word. This helps the word move from recognition to active use. Word Aware operationalises this finding through the STAR framework.

Context matters: Words learned in rich, meaningful contexts are retained better than words learned through rote memorisation. The approach's emphasis on activation across contexts reflects this principle.

One of Word Aware's most practical contributions is its classification of words into three tiers, helping teachers prioritise which words deserve intensive teaching.

Anchor Words are basic, high-frequency words that most children acquire through everyday language exposure. Examples include "big", "happy", "run", and "house". These words rarely need explicit teaching for typically Developing children, though they may require attention for children with language difficulties or English as an additional language. Anchor words form the foundation upon which other vocabulary builds.

Goldilocks Words are the priority targets for vocabulary instruction. These are words that are:

Examples include "fortunate", "merchant", "absurd", "coincidence", and "analyse". These words are perfect for direct teaching. Children are unlikely to learn them by chance but can understand them when taught directly. Goldilocks words significantly expand children's expressive range and reading comprehension.

Step-on Words are specialist, technical vocabulary tied to specific subjects or domains. Examples include "photosynthesis", "denominator", "peninsula", and "alliteration". These words are essential within their domains but may not transfer to other contexts. While important for subject-specific understanding, they are not the primary focus of whole-school vocabulary development.

This classification helps teachers make strategic decisions about vocabulary instruction. Rather than teaching every unknown word, teachers can focus their limited time on Goldilocks words that give the best results. Step-on words are still taught within their specific subject contexts. They are not part of whole-school vocabulary development.

The key insight is that not all words are created equal. Schools should focus systematic instruction on Goldilocks words. They should also ensure proper support for Anchor words and subject-specific teaching of Step-on words. This approach will maximise the impact of vocabulary instruction.

The STAR framework provides a practical structure for implementing Word Aware in classrooms. Each component serves a specific purpose in building deep word knowledge.

Select requires strategic thinking about which words to prioritise. Teachers consider the curriculum ahead, identifying words that appear across subjects and contexts. They avoid teaching every unfamiliar word. Instead, they focus on Goldilocks words that offer the best learning potential. Effective selection also considers children's prior knowledge, choosing words that stretch understanding without overwhelming learners.

Teach goes beyond simple definitions to build rich word knowledge. Teachers introduce words using child-friendly definitions that connect to known concepts. They give many examples showing the word in different contexts. They use images and gestures when helpful, and clearly discuss word relationships. The teaching phase establishes a foundation for all subsequent encounters with the word.

Activate creates opportunities for children to use target words actively. This might involve discussion activities, writing tasks, drama, or cross-curricular connections. The goal is to move beyond passive recognition to active production. Teachers plan activation opportunities across subjects, ensuring words appear in science investigations, history discussions, and creative writing.

Review ensures long-term retention through systematic revisiting. This is not simply testing whether children remember definitions, but deepening understanding through new contexts and connections. Review activities might explore synonyms and antonyms, word families, or subtle meaning differences. Regular review transforms short-Term learning into lasting vocabulary growth.

Successful Word Aware implementation requires whole-school commitment and systematic planning. Schools that achieve the greatest impact follow several key strategies.

Start with staff training: All teachers need to understand the rationale behind Word Aware and feel confident implementing the STAR framework. Training should be practical, providing opportunities to practise word selection and teaching techniques. Teachers need to see the approach modelled before implementing it themselves.

Create consistent visual displays: Word Aware walls in every classroom show target words with child-friendly definitions and images. These displays are interactive, with children encouraged to use displayed words in their spoken and written work. Consistency across classrooms reinforces the message that vocabulary development is everyone's responsibility.

Plan vocabulary across the curriculum. Rather than treating vocabulary as a separate subject, schools build word teaching into all lessons. Science teachers activate words like "observe" and "predict", while history teachers use words like "evidence" and "consequence". This cross-curricular approach dramatically increases children's exposure to target words.

Monitor and check impact: Schools track children's vocabulary growth through regular tests. They also watch how target words appear in children's independent writing. This data informs future word selection and helps teachers refine their practise.

Select the proficiency stage, first language group, and challenge area to receive tailored strategies, vocabulary targets, and progress milestones.

These peer-reviewed papers and evidence-based resources provide deeper insight into the research discussed in this article.

Bringing words to life: strong vocabulary instruction View study ↗

5678 citations

Beck, I.L., McKeown, M.G. & Kucan, L. (2013)

Beck and colleagues developed the three-tier vocabulary model that underpins Word Aware. Tier 1 (everyday words), Tier 2 (academic vocabulary), and Tier 3 (subject-specific terms) help teachers prioritise which words to teach explicitly rather than leaving vocabulary acquisition to chance.

Word Aware: Teaching vocabulary across the day, across the curriculum View study ↗

234 citations

Parsons, S. & Branagan, A. (2014)

The source text for the STAR approach (Select, Teach, Activate, Review). Parsons and Branagan combine speech and language therapy expertise with classroom practice, creating a systematic vocabulary teaching framework accessible to all teachers, not just literacy specialists.

Vocabulary and reading comprehension: A review of research View study ↗

2345 citations

Stahl, S.A. & Fairbanks, M.M. (1986)

Foundational meta-analysis showing that vocabulary instruction improves reading comprehension by an average effect size of d=0.33. Stahl and Fairbanks found that methods requiring active processing of word meanings produced larger gains than those relying on definitions alone.

Closing the vocabulary gap View study ↗

456 citations

Quigley, A. (2018)

Quigley connects the vocabulary gap to social inequality in UK schools. He provides practical strategies aligned with Word Aware principles: explicit teaching, repeated encounters, and active use in meaningful contexts. His seven-step "word instruction" model complements the STAR framework.

Why do students with good reading comprehension struggle with vocabulary? View study ↗

1234 citations

Nation, K. & Snowling, M.J. (2004)

Nation and Snowling demonstrate that vocabulary knowledge is not a unitary skill: children can decode words without understanding them. This finding supports the Word Aware emphasis on depth of word knowledge (multiple meanings, contexts, and connections) rather than breadth alone.

Word Aware is a whole-school vocabulary programme designed by speech and language therapists. The STAR approach stands for Select, Teach, Activate, and Review. It helps teachers move beyond simple dictionary definitions to build deep vocabulary knowledge through multiple meaningful encounters with words.

Teachers using this method categorise vocabulary into Anchor, Goldilocks, and Step-on words. The primary focus is on Goldilocks words, which are useful across multiple contexts and appear frequently in academic texts. Teachers introduce these words explicitly using child-friendly definitions and plan activities for students to use them actively.

The programme significantly improves reading comprehension and communication skills across the curriculum. By embedding vocabulary development into everyday lessons, it helps close the language gap for disadvantaged learners. Children move from simply recognising a word to actively using it in their own speaking and writing.

Research shows that a single exposure to a new word is rarely enough for lasting learning. Studies indicate that children need around twelve meaningful encounters with a word before they can use it confidently. Explicit instruction that includes varied contexts and links to previous knowledge produces the best academic outcomes.

A frequent mistake is relying entirely on rote memorisation and basic dictionary definitions. Teachers sometimes assume that mentioning a word once during a lesson is sufficient for children to retain it. Another common error is failing to plan structured opportunities for pupils to practise using the new words in different subjects.

Word Aware transforms vocabulary teaching from an afterthought to a systematic, evidence-based practise that benefits all children while particularly supporting those from disadvantaged backgrounds. The STAR framework gives teachers a clear structure. It moves beyond traditional methods that rely on definitions and single exposures. Schools can dramatically speed up children's vocabulary growth by carefully selecting Goldilocks words. They should teach them directly, use them in different situations, and review them regularly.

The approach's power lies in its whole-school implementation. When every teacher understands word types and uses the STAR framework, children meet target words throughout their school experience. This multiplication of meaningful encounters transforms vocabulary learning from a slow, unreliable process to rapid, systematic development. Word Aware offers a proven pathway to success. It helps schools close achievement gaps and raise standards for all children.

Vocabulary instruction research

The following research papers and publications provide deeper insights into vocabulary development and the evidence base underlying Word Aware:

<script type="application/ld+json">{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/word-aware-complete-guide-star-approach#article","headline":"Word Aware: The Complete Guide to the STAR Approach for Vocabulary Development","description":"Implement the Word Aware STAR approach to enhance vocabulary teaching, focusing on word selection, Goldilocks words, and strategies for diverse learners.","datePublished":"2026-01-20T09:45:08.465Z","dateModified":"2026-02-02T15:08:15.289Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/word-aware-complete-guide-star-approach"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/696f4ea45987f3125105be7c_696f4e086cb64098d37fe266_word-aware-the-complete-guide--comparison-1768902147826.webp","wordCount":1857},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/word-aware-complete-guide-star-approach#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"Word Aware: The Complete Guide to the STAR Approach for Vocabulary Development","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/word-aware-complete-guide-star-approach"}]},{"@type":"FAQPage","mainEntity":[{"@type":"Question","name":"What is the Word Aware STAR approach in education?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Word Aware is a whole-school vocabulary programme designed by speech and language therapists. The STAR approach stands for Select, Teach, Activate, and Review. It helps teachers move beyond simple dictionary definitions to build deep vocabulary knowledge through multiple meaningful encounters with words."}},{"@type":"Question","name":"How do teachers implement Word Aware in the classroom?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Teachers using this method categorise vocabulary into Anchor, Goldilocks, and Step-on words. The primary focus is on Goldilocks words, which are useful across multiple contexts and appear frequently in academic texts. Teachers introduce these words explicitly using child-friendly definitions and plan activities for students to use them actively."}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What are the benefits of the Word Aware programme for learning?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"The programme significantly improves reading comprehension and communication skills across the curriculum. By embedding vocabulary development into everyday lessons, it helps close the language gap for disadvantaged learners. Children move from simply recognising a word to actively using it in their own speaking and writing."}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What does educational research say about vocabulary retention?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Research shows that a single exposure to a new word is rarely enough for lasting learning. Studies indicate that children need around twelve meaningful encounters with a word before they can use it confidently. Explicit instruction that includes varied contexts and links to previous knowledge produces the best academic outcomes."}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What are common mistakes when teaching vocabulary in schools?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"A frequent mistake is relying entirely on rote memorisation and basic dictionary definitions. Teachers sometimes assume that mentioning a word once during a lesson is sufficient for children to retain it. Another common error is failing to plan structured opportunities for pupils to practise using the new words in different subjects."}}]}]}</script>