Encoding Strategies for Long-Term Learning

Explore encoding strategies that help teachers turn classroom experiences into lasting memories, using practical techniques for deeper student understanding.

Explore encoding strategies that help teachers turn classroom experiences into lasting memories, using practical techniques for deeper student understanding.

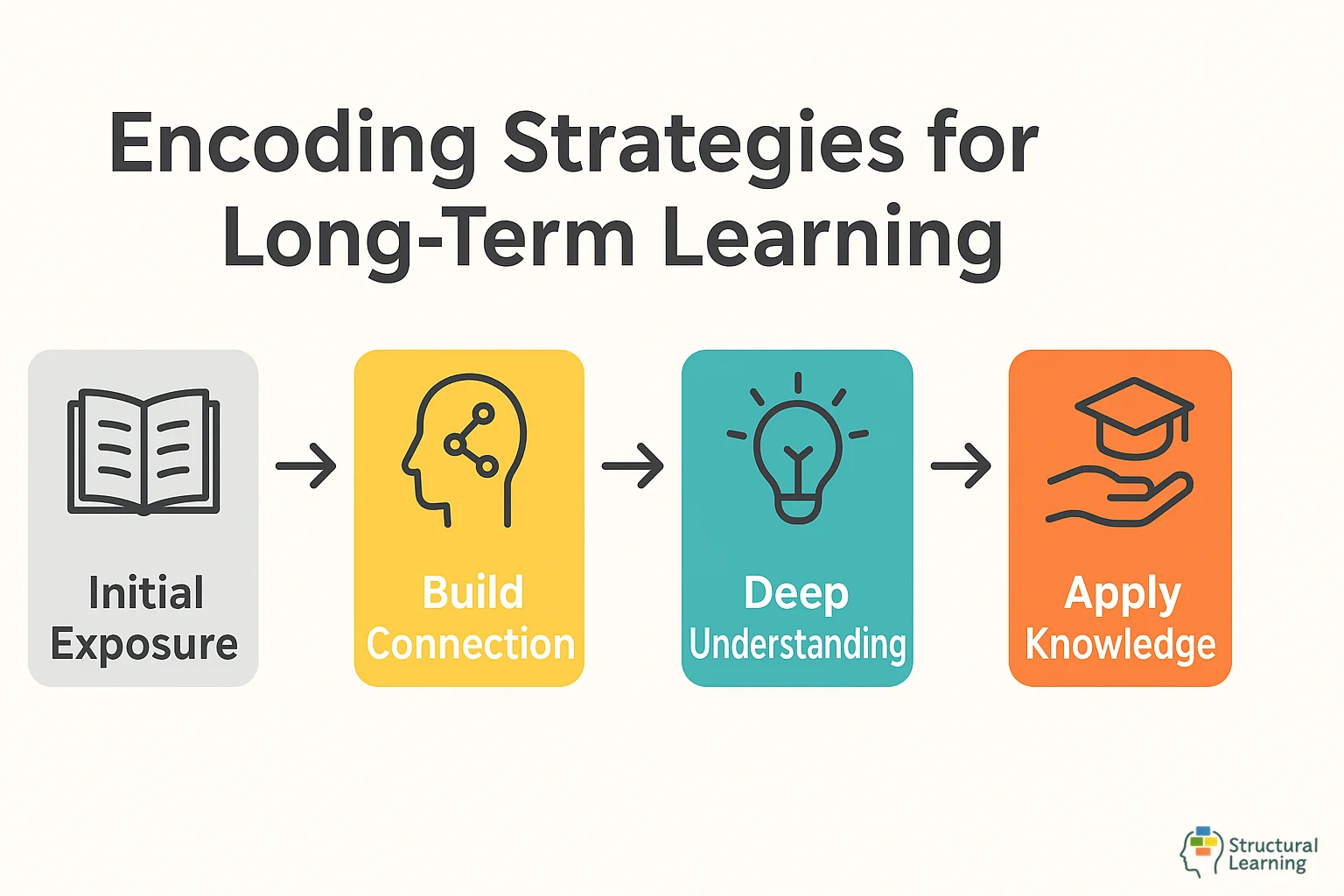

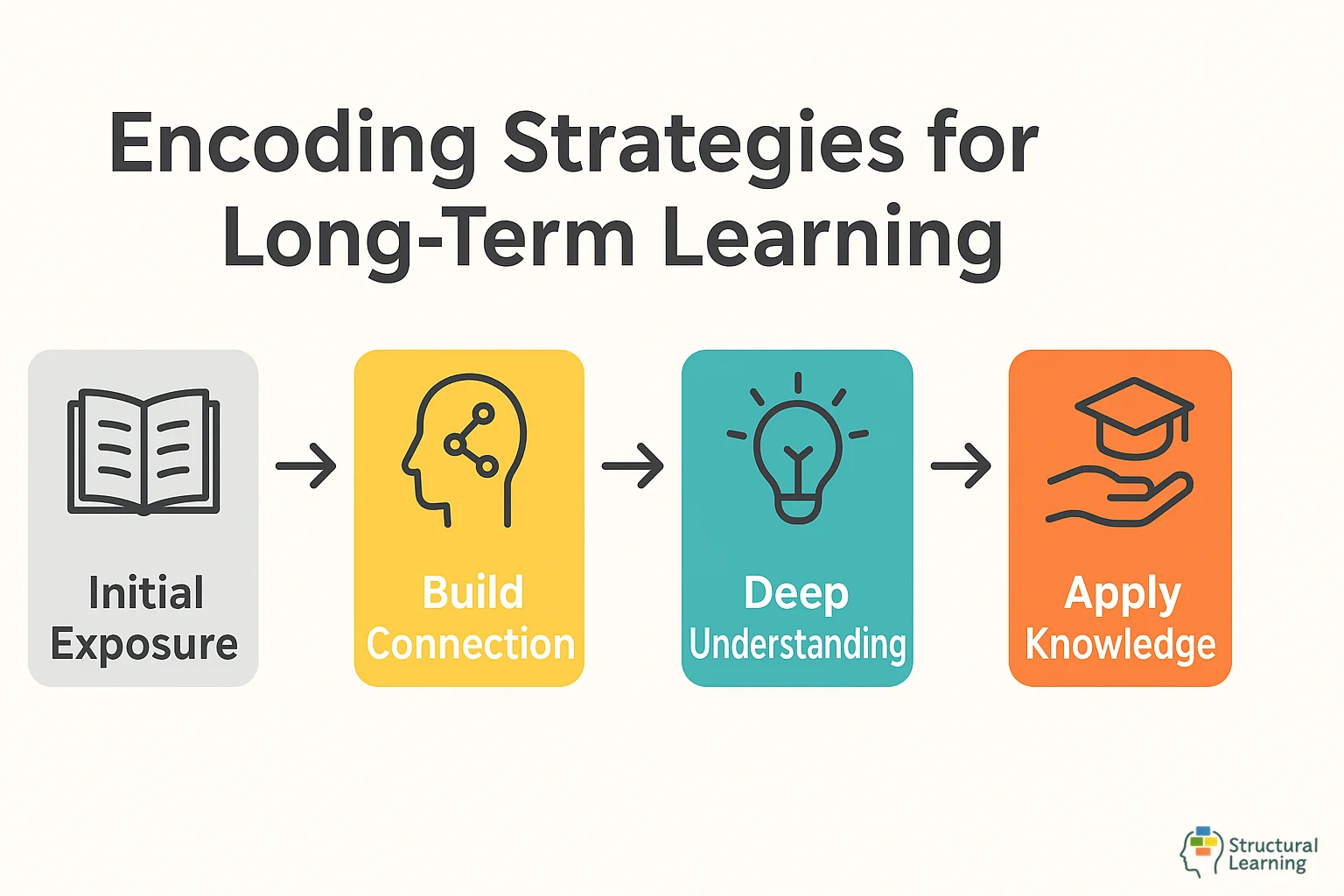

Effective encoding strategies form the foundation of successful long-term learning, transforming how students process and retain information in their memory systems. When educators implement research-backed encoding techniques such as elaborative processing, dual coding, and spaced retrieval practise, they dramatically increase the likelihood that new knowledge will stick with students far beyond the classroom. These powerful methods work by creating multiple pathways to stored information and strengthening neural connections through strategic repetition and meaningful associations. The difference between students who remember what they learn and those who forget lies not in natural ability, but in the specific encoding techniques their teachers choose to employ.

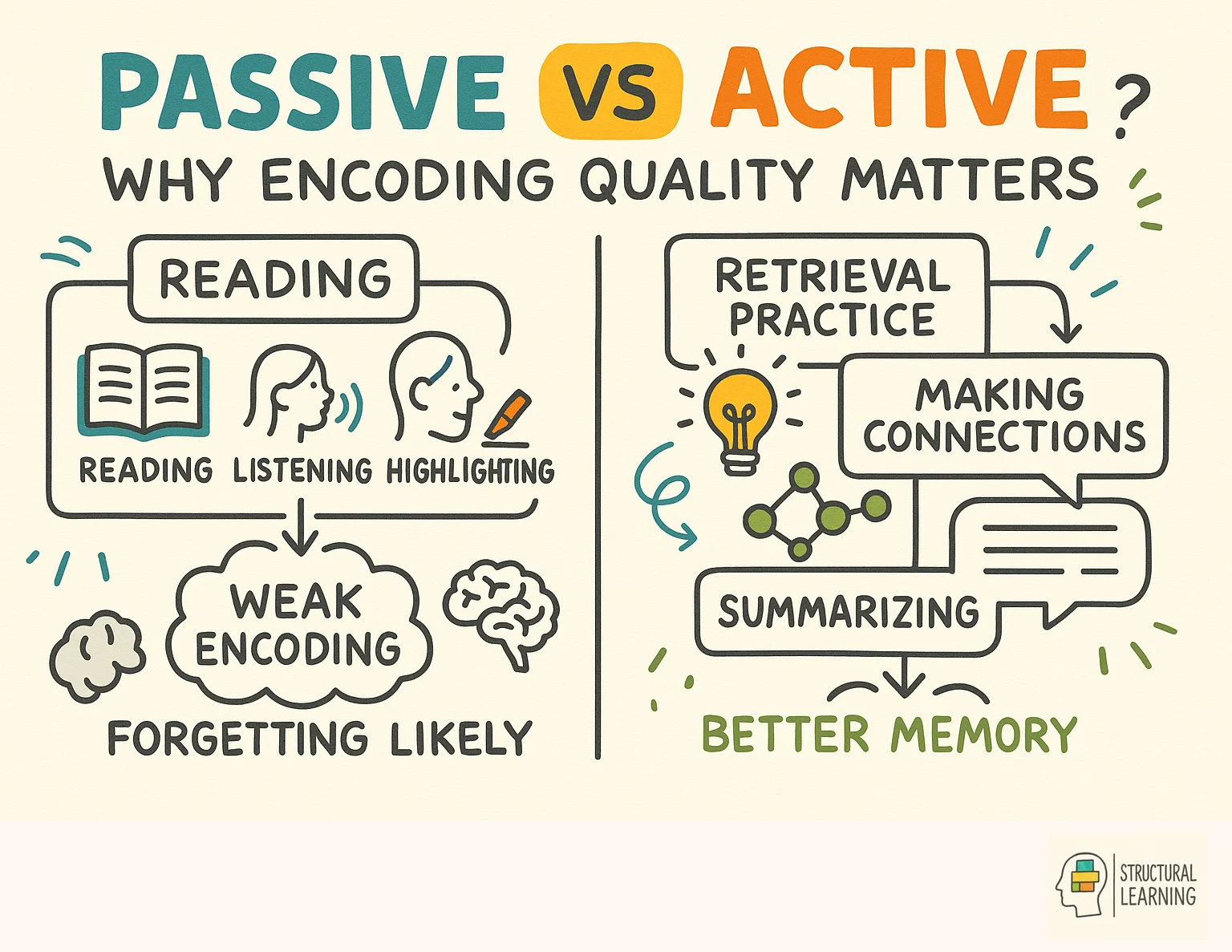

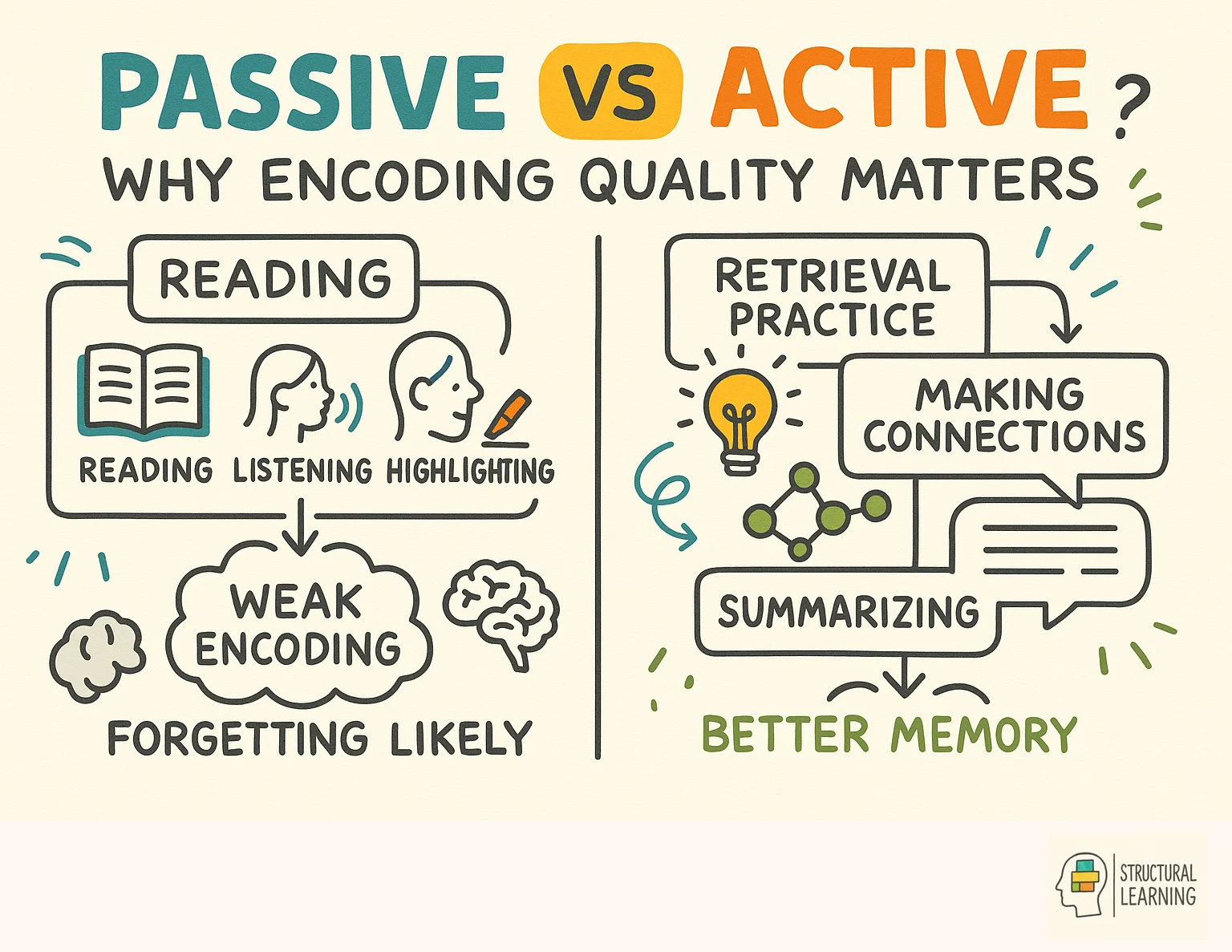

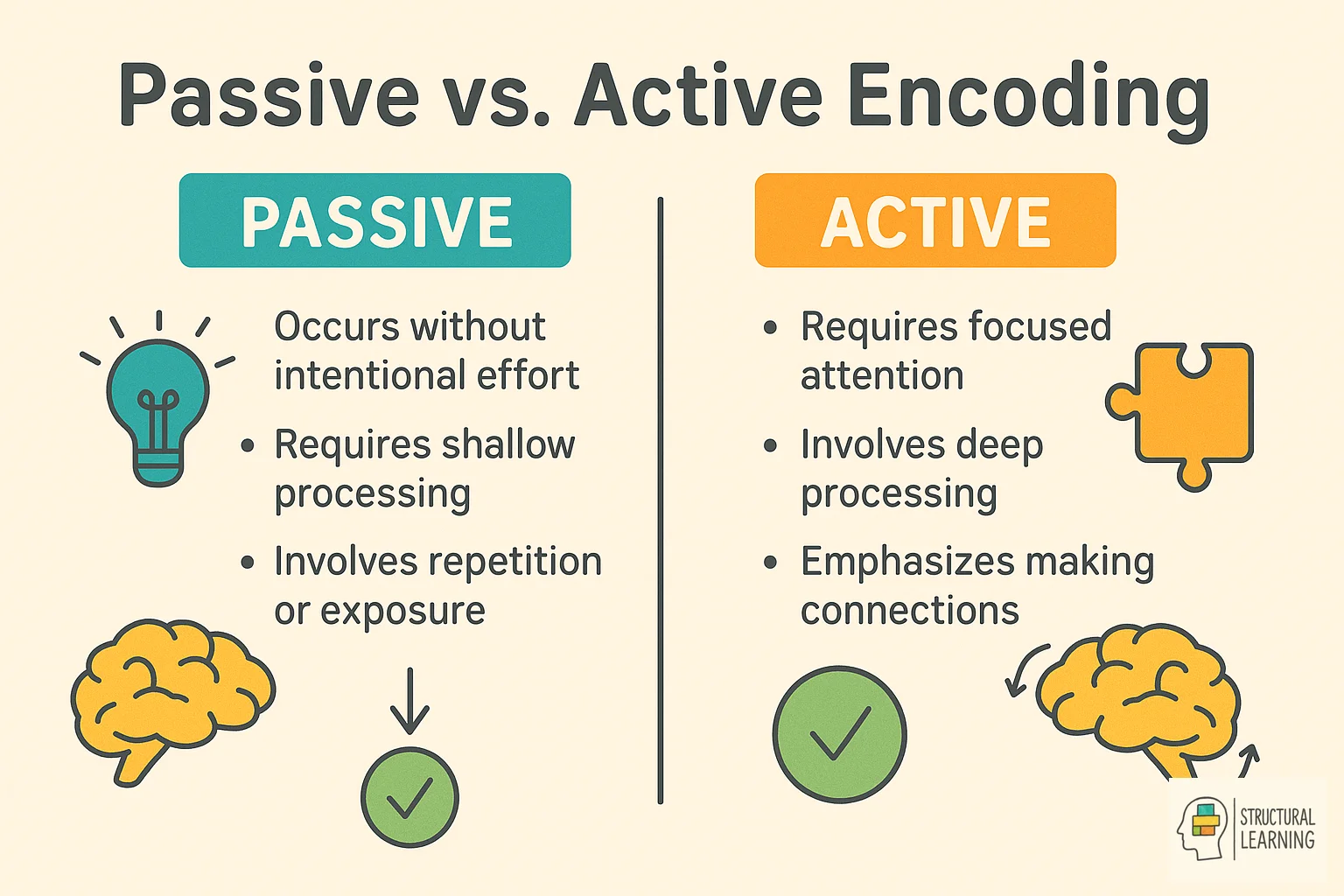

Encoding is the process of transforming experiences into memory traces. It's the gateway to learning: without effective encoding, there's nothing to retrieve later. Yet much classroom practise focuses on exposure to information rather than active processing of it. Students read, listen, and highlight, but these passive activities often produce weak encoding that leads to rapid forgetting. Without techniques like spaced practise, even well-encoded information may not transfer effectively to long-term memory.

The good news is that decades of cognitive science research have identified evidence-based memory strategies that reliably produce stronger, more durable memories. These aren't mysterious techniques; they're practical approaches that teachers can embed into everyday instruction, often supporting self-regulated learning in the process.

Memory encoding is the transformation of experiences into neural patterns that can be stored and retrieved later. The quality of initial encoding determines how well information will be remembered, with active processing techniques producing stronger memories than passive exposure. Teachers can improve student learning by embedding evidence-based encoding strategies into everyday instruction.

| Feature | Shallow Processing | Deep Processing |

|---|---|---|

| Focus | Surface features (appearance, sound) | Meaning and connections |

| Examples | Copying notes, highlighting text, memorizing location | Explaining concepts, making connections, applying to new situations |

| Memory Strength | Weak, easily forgotten | Strong, durable memories |

| Effort Required | Low effort, fast processing | Higher effort, slower processing |

| Classroom Activities | Reading without discussion, reviewing flashcards | Explaining meaning, generating connections |

| Retention Rate | Poor long-term retention | Better retention with less review time |

Memory encoding represents the critical first stage in the learning process, determining whether information becomes accessible for future use or disappears entirely. For educators, understanding encoding fundamentals means recognising that learning is not passive absorption but an active process requiring deliberate instructional design.

The encoding process involves three key stages: attention capture, information processing, and storage pathway activation. During attention capture, students must focus on relevant information whilst filtering out distractions. Information processing then transforms this attended information through various cognitive operations, such as connecting new concepts to existing knowledge or creating mental representations. Finally, storage pathway activation determines whether information enters working memory briefly or progresses to long-term memory for permanent retention.

Effective encoding instruction requires teachers to orchestrate these stages deliberately. Rather than simply presenting information and hoping students absorb it, educators must design activities that guide attention, structure processing, and strengthen storage pathways. This approach transforms teaching from information delivery to cognitive facilitation, significantly improving student learning outcomes.

Successful classroom implementation of encoding strategies involves managing cognitive load through techniques such as chunking information into manageable segments, providing clear organisational frameworks, and using multiple sensory channels. For instance, when teaching historical events, teachers might combine visual timelines with verbal explanations and hands-on activities, allowing students to process information through different pathways. This multi-modal approach strengthens encoding by creating multiple retrieval routes whilst preventing working memory overload.

Understanding encoding fundamentals also helps educators recognise why traditional lecture-heavy approaches often fail. When students passively listen without engaging their encoding processes, information rarely transfers to long-term memory. Instead, effective teachers use interactive questioning, peer discussions, and application exercises that actively engage memory processes, ensuring robust encoding and improved retention across diverse learning contexts.

Encoding refers to the initial processing of information that creates a memory trace. When you pay attention to something, your brain converts that experience into neural patterns that can be stored and later retrieved. The nature of this processing determines how well the information will be remembered.

Think of encoding as translation. Your experiences exist in the external world; encoding translates them into the internal language of your neural networks. Poor translation produces garbled messages that are hard to understand later. Good translation produces clear representations that remain accessible over time.

Research on working memory limitations helps explain encoding constraints. Working memory can hold only a limited amount of information at once, so encoding must be selective. What receives attention gets encoded; what doesn't is lost before it reaches long-term storage. This highlights the importance of metacognitive awareness in helping students direct their attention effectively.

In classroom implementation, educators can use these multiple encoding pathways through deliberate instructional design. For instance, when teaching historical events, combining timeline visuals (visual encoding) with storytelling techniques (auditory encoding) and discussions about cause-and-effect relationships (semantic encoding) creates multiple retrieval routes for the same information. This multi-modal approach accommodates diverse learning preferences whilst strengthening memory consolidation for all students.

Working memory constraints significantly influence encoding effectiveness, particularly when cognitive load exceeds students' processing capacity. Teachers can support optimal encoding by chunking complex information into manageable segments, providing clear organisational structures, and eliminating extraneous details during initial learning phases. Additionally, encouraging students to elaborate on new information through questioning, summarising, or connecting to prior knowledge activates deeper semantic encoding processes, transforming surface-level memorisation into meaningful understanding that transfers across contexts and persists in long-term memory.

| Encoding Type | Processing Level | Student Activity | Memory Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structural Encoding | Shallow (visual features) | Noticing if a word is in capitals or what colour something is | Weak, quickly forgotten; brief retention only |

| Phonemic Encoding | Shallow (acoustic features) | Repeating information, focusing on sound or rhythm | Moderate; better than structural but still limited |

| Semantic Encoding | Deep (meaning-based) | Thinking about what information means and how it relates to prior knowledge | Strong; durable long-term memories formed |

| Elaborative Encoding | Deep (connection-building) | Creating links between new and existing knowledge through explanation | Very strong; multiple retrieval pathways created |

| Self-Referential Encoding | Deep (personal connection) | Relating information to personal experiences or oneself | Excellent; the "self-reference effect" produces superior recall |

| Organisational Encoding | Deep (structure-building) | Categorising, grouping, or structuring information hierarchically | Strong; organised information is easier to retrieve |

Based on Craik and Lockhart's Levels of Processing Theory (1972) and subsequent encoding research. The key insight: how information is processed during learning matters more than how long it's studied. Five minutes of deep processing beats twenty minutes of shallow processing.

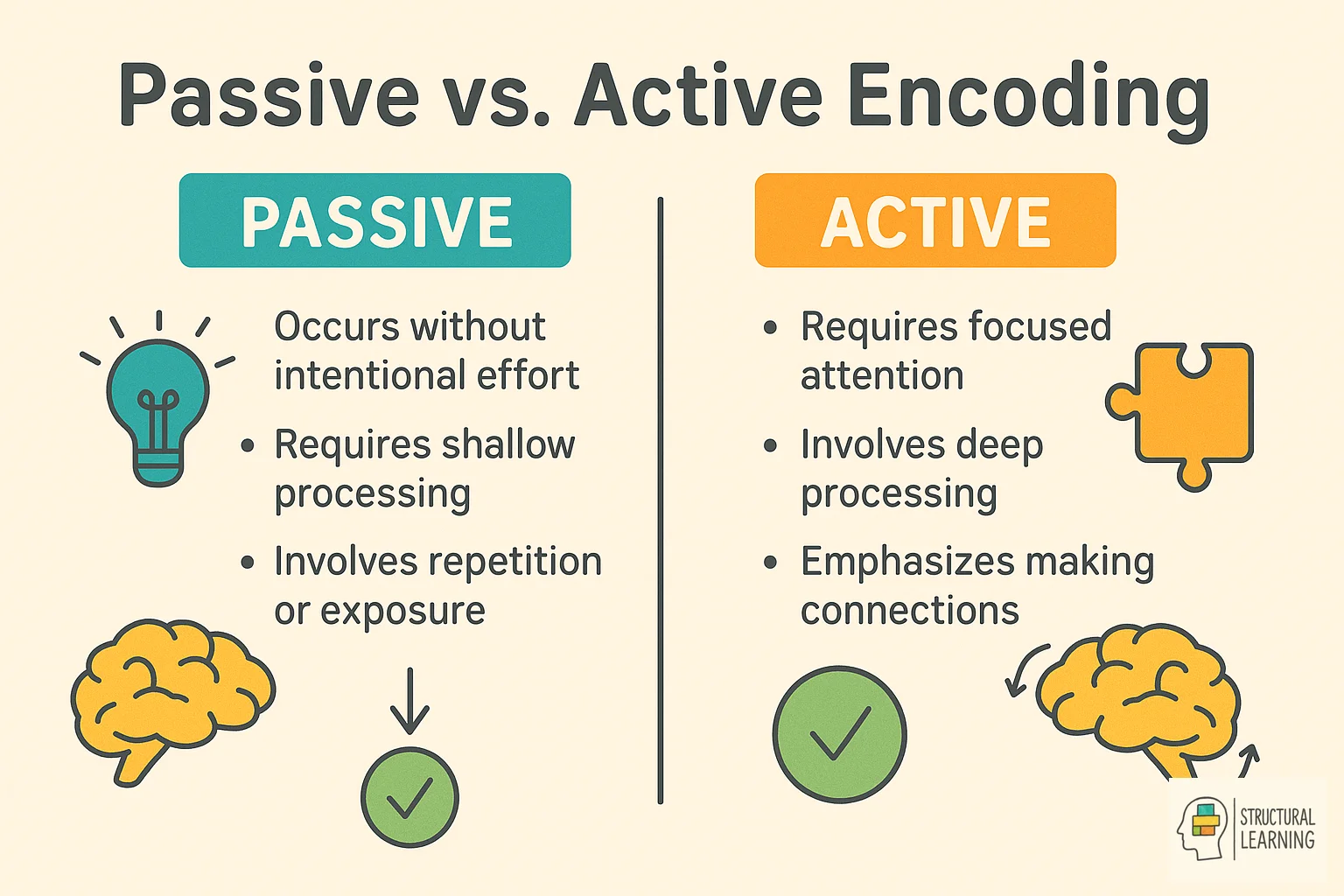

The Levels of Processing Theory states that deeper, more meaningful processing of information leads to better memory retention than shallow processing. Shallow processing involves surface features like appearance or sound, while deep processing engages with meaning, connections, and applications. Teachers can apply this by designing activities that require students to explain, compare, or apply concepts rather than just memorize facts.

In 1972, Fergus Craik and Robert Lockhart proposed the levels of processing framework, which remains influential for understanding encoding.

Shallow processing focuses on surface features of information: what it looks like, what it sounds like. Reading words without thinking about their meaning constitutes shallow processing. So does noting that a fact appeared on page 47 without engaging with what the fact means.

Shallow processing produces weak, easily forgotten memories. It's fast and requires little effort, which is why students often default to it. But the speed comes at a cost to retention.

Deep processing engages with meaning and connections. When you think about what something means, how it relates to what you already know, or why it matters, you're processing deeply. This semantic processing creates richer, more elaborate memory traces.

Deep processing takes more effort than shallow processing, but the investment pays off in better retention. Students who spend five minutes processing deeply often remember more than students who spend twenty minutes processing shallowly.

Much traditional instruction inadvertently encourages shallow processing. Copying notes from a board, reading passages without discussion, and reviewing flashcards without explaining relationships all constitute shallow processing.

Teachers can shift towards deep processing by asking students to explain meaning, generate connections, and apply information to new situations. Any activity that requires thinking about what something means, rather than just what it looks like, promotes deep encoding.

The five most effective encoding strategies are elaborative interrogation (asking why questions), self-explanation (students explaining concepts in their own words), dual coding (combining visual and verbal information), concrete examples (linking abstract concepts to specific instances), and generation effect (having students produce information rather than just read it). These strategies work because they require active mental processing and create multiple retrieval pathways. Teachers can incorporate these by building them into lesson activities and homework assignments.

Research has identified several encoding strategies that reliably produce strong memories. These strategies can be taught explicitly and embedded into classroom routines.

Elaboration involves adding meaning and connections to new information. Rather than storing isolated facts, elaboration links new learning to existing knowledge, creating multiple retrieval pathways.

Elaboration takes many forms:

Elaborative interrogation is a specific technique that prompts students to explain why facts are true. When students generate explanations, they create elaborated memory traces that persist longer than unelaborated information.

In the classroom, build elaboration into instruction by regularly pausing to ask: "Why is this the case?" "How does this connect to what we learned last week?" "Can you think of an example from your own experience?"

Organisation involves imposing structure on information. Organised information is easier to encode and retrieve than scattered, disorganised content.

Effective organisation strategies include:

Organisation works partly by chunking information. Rather than encoding many separate items, learners encode a smaller number of organised chunks. Each chunk serves as a retrieval cue for its contents.

Teachers can support organisational encoding by making structure explicit. Don't just present information; show how it's organised. Use consistent structures across lessons so students can fit new information into familiar frameworks.

Visualisation creates mental images of information. Visual memories are distinct from verbal memories, and encoding information in both forms produces stronger retention than either alone.

Dual coding theory, developed by Allan Paivio, explains this advantage. Information encoded both verbally and visually benefits from two independent memory traces. If one trace fades, the other may remain accessible.

Visualisation strategies include:

Encourage students to create mental pictures as they learn. Ask: "Can you picture this?" "What would this look like?" "Draw what you're imagining."

Information connected to ourselves is encoded more strongly than impersonal information. This self-reference effect provides a powerful encoding strategy.

When students relate new learning to their own experiences, opinions, or goals, they process it more deeply and remember it better. The personal connection creates elaboration and emotional engagement that strengthen encoding.

Classroom applications include:

This explains why personalised examples often produce better learning than generic ones. Asking "How does this apply to your life?" produces stronger encoding than presenting the same information in decontextualised form.

Distinctive information stands out in memory. When encoding produces a unique, differentiated representation, retrieval becomes easier because the memory is less likely to be confused with similar information.

Strategies promoting distinctiveness:

When teaching similar concepts, emphasise what distinguishes them. This distinctive encoding reduces confusion and interference at retrieval.

Attention acts as the gateway to encoding because information must be consciously processed to create strong memory traces. Without focused attention, information bypasses working memory and never gets encoded into long-term storage. Teachers can support attention by minimising distractions, using attention-grabbing techniques at key moments, and breaking lessons into shorter segments with clear focus points.

Encoding requires attention. Information that doesn't receive attention cannot be encoded, no matter how long it's presented. This makes attention the gateway to all learning.

Classrooms present multiple stimuli competing for attention. Students must selectively attend to relevant information while ignoring distractions. Teachers can support selective attention by clearly signalling what's important and reducing competing stimuli.

Learning requires maintaining attention over time. Attention naturally fluctuates, with most students showing declining focus after 10-20 minutes. Varying instructional activities, building in movement, and strategic timing of key content helps maintain attention throughout lessons.

When attention is divided between multiple demanding tasks, encoding of each task suffers. Students who check their phones during instruction encode less than those who focus completely. Similarly, overly complex instruction that demands attention to multiple elements simultaneously can overwhelm attention capacity.

Research on cognitive load theoryaddresses how instructional design affects attention and encoding. Managing cognitive load ensures sufficient attention remains available for encoding target content.

Working memory can only hold about 4-7 chunks of information at once, creating a bottleneck for encoding new material into long-term memory. When working memory is overloaded, encoding quality suffers and students struggle to form lasting memories. Teachers can accommodate these limits by chunking information into meaningful units, providing scaffolding, and allowing processing time between new concepts.

Working memory is the cognitive system that holds and manipulates information during encoding. It serves as the workspace where new information is processed before entering long-term memory.

Working memory has severe capacity limitations. Most people can hold only 3-5 chunks of information simultaneously. When encoding demands exceed working memory capacity, some information is lost.

Teachers can support encoding by breaking content into manageable chunks. Present a few ideas at a time, allow processing before moving on, and don't overload working memory with unnecessary complexity.

Deep processing requires working memory resources. If working memory is overwhelmed by too much information, students default to shallow processing because they lack the capacity for deeper engagement.

Reduce extraneous cognitive loadto free resources for encoding. Eliminate unnecessary complexity, ensure materials are well-designed, and provide scaffolds that reduce working memory burden.

Students with relevant prior knowledge can encode new information more efficiently because they can chunk it into existing schemas. This is why activating prior knowledge at the start of lessons supports encoding: it prepares mental structures to receive new information.

Encoding and retrieval are interconnected processes where the way information is initially encoded determines how easily it can be retrieved later. Strong encoding creates multiple retrieval cues and pathways, while poor encoding leaves few ways to access the memory. Teachers should align encoding activities with how students will need to retrieve and use the information, such as encoding math concepts through problem-solving if that's how they'll be tested.

Encoding and retrieval are intimately connected. The conditions at encoding shape what retrieval cues will be effective later. This principle, called encoding specificity, has important implications for learning.

Information is encoded along with context: where you learned it, what you were thinking, what was happening around you. These contextual elements become linked to the memory and can serve as retrieval cues.

This explains why students sometimes perform better in the room where they learned material, or why returning to a topic can trigger recall of related information. The context provides cues that access the encoded memory.

Retrieval is most successful when it matches the type of processing used during encoding. If you encoded information by thinking about its meaning, tests that require meaning-based retrieval will succeed. If you encoded by rote repetition, meaning-based questions may fail even though the information is stored.

This principle suggests that encoding should match anticipated retrieval. If students will need to apply concepts to novel problems, they should practise application during encoding. If they will need to recall factual details, they should encode those details specifically.

These evidence-based encoding strategies help teachers design instruction that creates durable, retrievable memories. When students process information deeply during initial learning, they build strong memory traces that resist forgetting and transfer flexibly to new situations.

The research on encoding is unambiguous: quality of initial processing determines quality of later memory. Teachers who understand encoding design instruction that engages students' minds actively with meaning and connections, not just passive exposure to information. The key question isn't "Did students see this content?" but "Did students process it deeply enough to remember it?" Every instructional choice either promotes or undermines effective encoding - choose activities that require thinking about meaning, and memories will follow.

Different subjects benefit from specific encoding strategies based on the type of information being learned. Math and science benefit from worked examples and visual representations, while language arts benefits from elaboration and making connections to prior texts. History and social studies encoding improves through timeline creation and cause-effect mapping, demonstrating that teachers should match encoding techniques to their content area.

Effective encoding strategies vary somewhat across subject areas, reflecting different knowledge structures and learning goals.

Science encoding benefits from:

Visual encoding is particularly important in science, where processes, structures, and relationships benefit from diagrammatic representation.

Mathematical encoding benefits from:

Mathematics requires encoding both procedures and the concepts that underpin them. Encoding procedures without understanding leads to fragile, inflexible knowledge.

Historical encoding benefits from:

Historical understanding requires encoding events within causal narratives, not as isolated facts.

Language encoding benefits from:

Vocabulary instruction is most effective when words are encoded through meaningful use rather than isolated memorisation.

Teachers can help students understand encoding by explaining how memory works using simple analogies and demonstrating the difference between passive reading and active processing. Show students specific encoding techniques like self-testing and elaboration, then provide guided practise with AI-enhanced feedback. Regular metacognitive discussions about which strategies work best for different types of content help students become independent learners.

Helping students understand encoding supports metacognition and independent learning. Students who understand how memory works can adopt more effective study strategies.

Students often rely on shallow processing (re-reading, highlighting) because it feels productive. Teaching the distinction between shallow and deep processing helps students understand why these strategies often fail.

Demonstrate encoding strategies explicitly. Show students how to elaborate, organise, and visualise. Think aloud while encoding to make these processes visible.

Give students structured opportunities to practise encoding strategies with feedback. Initially scaffold the strategies, then gradually release responsibility as students develop competence.

Use prompts that encourage students to monitor their encoding:

Effective classroom routines that support encoding include starting lessons with retrieval practise of previous material, using think-pair-share for active processing, and ending with exit tickets that require elaboration. Build in regular brain breaks to prevent cognitive overload and establish consistent patterns for introducing new concepts. These routines create predictable opportunities for deep processing without adding extra planning burden.

Embedding encoding strategies in classroom routines ensures consistent application.

Begin lessons by activating prior knowledge relevant to new content. This prepares schemas for encoding and creates connection points for new information.

Pause regularly to prompt encoding. After presenting key concepts, ask students to explain, visualise, connect, or apply. These encoding activities take minimal time but substantially improve retention.

End lessons with activities that consolidate encoding. Summarisation, connection-making, and retrieval practise all strengthen the memories formed during the lesson.

Timing these encoding routines strategically throughout the school day maximises their effectiveness. Morning lessons benefit from 'memory bridge' activities where students spend the first five minutes connecting previous day's learning to current objectives through quick verbal sharing or written reflections. This primes their cognitive systems for optimal information processing. Similarly, post-break transitions offer valuable encoding opportunities - rather than diving straight into new content, use two-minute recap discussions to reactivate dormant neural networks from earlier lessons.

Physical movement can significantly enhance these daily encoding routines. Incorporate 'walk and talk' moments where students move around the classroom whilst discussing key concepts, or use simple gestures to represent important ideas. Research demonstrates that motor activity during learning strengthens memory consolidation pathways. Additionally, vary your encoding strategies across different subjects - use visual organisers for complex topics, rhythmic patterns for sequential information, and storytelling techniques for abstract concepts. This variety prevents cognitive habituation whilst catering to diverse learning preferences, ensuring consistent memory encoding throughout your instructional day.

Successful transfer from encoding to long-term retention requires spaced practise, where students revisit material at increasing intervals over time. Interleaving different topics during practise sessions strengthens memory consolidationbetter than b locked practise. Teachers should design review cycles that bring back previously encoded material in new contexts, forcing reprocessing that strengthens memory traces.

Encoding is necessary but not sufficient for lasting learning. Strong encoding provides the foundation, but consolidation and retrieval practise are also required for durable retention.

A complete approach to memory combines:

Teachers who address all three processes maximise their impact on long-term learning.

The transfer from working memory to long-term memory requires specific conditions that teachers can deliberately create. Spaced repetition proves most effective, with information reviewed at increasing intervals rather than massed practice. Introduce concepts initially, revisit them within 24 hours, then again after three days, one week, and one month for optimal retention.

Meaningful connections accelerate this transfer process. When students link new information to existing knowledge, personal experiences, or cross-curricular content, multiple neural pathways form, creating redundant storage systems. Encourage students to explain how new concepts relate to their lives or previous learning, strengthening these connective pathways.

Elaborative encoding strategies further enhance long-term retention by requiring deeper cognitive processing. Rather than simple rehearsal, students should engage with material through questioning, summarising, and teaching others. For instance, having students create concept maps or analogies forces them to process information meaningfully rather than superficially, promoting robust memory formation.

Sleep and consolidation time also play crucial roles in long-term transfer. Avoid cramming multiple new concepts into single lessons. Instead, introduce key ideas with sufficient processing time, allowing the brain's natural consolidation processes to work overnight. This spacing gives the hippocampus time to replay and strengthen memories, facilitating successful long-term storage and retrieval when needed.

Begin by replacing passive activities with active ones, such as turning reading assignments into guided note-taking with specific prompts for elaboration. Start each lesson with a brief retrieval practise of yesterday's content and end with students explaining one key concept to a partner. Choose one encoding strategy to master at a time, implementing it consistently for several weeks before adding another.

Begin improving encoding in your classroom with these manageable changes.

Ask "why" and "how" questions that require explanation rather than recognition. Every lesson should include moments where students must explain concepts in their own words.

Use graphic organisers to support organisational encoding. Maps, webs, and hierarchies help students see and encode structure.

Connect to prior knowledge explicitly at lesson beginnings. Activating relevant schemas prepares the cognitive context for new encoding.

Reduce cognitive load by chunking information and eliminating unnecessary complexity. What remains should receive full processing attention.

Build encoding pauses into instruction. After presenting key content, stop and prompt encoding activity before moving on.

These strategies don't require additional time. They redirect existing instructional time towards activities that produce genuine learning rather than the illusion of understanding.

Essential research includes Craik and Lockhart's levels of processing framework, Roediger and Karpicke's work on the testing effect, and Dunlosky's review of effective learning techniques. These foundational papers provide evidence for why certain encoding strategies work and how to implement them effectively. Teachers can access practical summaries through organisations like the Learning Scientists and Retrieval Practise websites.

The following papers provide deeper exploration of encoding and its educational applications.

This foundational paper introduced the levels of processing framework that transformed memory research. The authors argued that memory depends on depth of processing during encoding, with semantic processing producing superior retention. The paper launched extensive research on how encoding strategies affect learning.

This research established elaborative interrogation as an effective encoding strategy. The authors found that prompting students to explain why facts are true substantially improved memory for those facts. The technique works by generating elaborated connections between new and existing knowledge.

This comprehensive review evaluated ten learning techniques including several encoding strategies. Elaborative interrogation and self-explanation received positive ratings, while commonly used strategies like highlighting and re-reading were rated as less effective.

Allan Paivio explains dual coding theory and its educational implications. The paper describes how combining verbal and visual encoding produces stronger memories than either alone, supporting the use of diagrams, imagery, and multimedia in instruction.

While focused on retrieval, this paper demonstrates how encoding and retrieval interact. The research shows that retrieval practise produces better retention than elaborative studying, highlighting the importance of active processing over passive review.

Experiences are transformed through the process of encoding into memory traces that can be stored and retrieved later. Without effective encoding, there's nothing for students to retrieve from memory, making it the gateway to all learning. The quality of initial encoding determines how well information will be remembered, regardless of how many times students review it afterwards.

Teachers can promote deep processing by asking students to explain meaning, generate connections, and apply information to new situations rather than just copying notes or highlighting text. Build regular pauses into lessons to ask questions like 'Why is this the case?' or 'How does this connect to what we learned last week?' Any activity that requires thinking about what something means, rather than just what it looks like, promotes deep encoding.

The five most effective strategies are elaborative interrogation (asking why questions), self-explanation (students explaining concepts in their own words), dual coding (combining visual and verbal information), concrete examples (linking abstract concepts to specific instances), and the generation effect (having students produce information rather than just read it). These strategies work because they require active mental processing and create multiple retrieval pathways in memory.

These activities constitute shallow processing, which focuses only on surface features like appearance rather than meaning and connections. Shallow processing produces weak, easily forgotten memories because it requires minimal mental effort and creates limited retrieval pathways. Students who spend five minutes processing deeply often remember more than those who spend twenty minutes processing shallowly.

Elaborative interrogation involves prompting students to explain why facts are true, which creates elaborated memory traces that persist longer than unelaborated information. Teachers can build this into instruction by regularly asking questions like 'Why is this the case?', 'How does this connect to previous learning?', or 'Can you think of an example from your own experience?' This technique helps students link new information to existing knowledge, creating multiple retrieval pathways.

Organisation involves imposing structure on information, making it easier to encode and retrieve than scattered, disorganised content. It works by chunking information into smaller, structured units where each chunk serves as a retrieval cue for its contents. Teachers can support organisational encoding by making structure explicit and using consistent frameworks across lessons so students can fit new information into familiar patterns.

Dual coding theory explains that information encoded both verbally and visually benefits from two independent memory traces, producing stronger retention than either form alone. If one memory trace fades, the other may remain accessible, providing students with multiple pathways to retrieve information. Teachers should combine visual and verbal information presentation to take advantage of this dual encoding benefit.

These peer-reviewed studies provide the research foundation for the strategies discussed in this article:

HOW DOES GRANTING TEACHER AUTONOMY INFLUENCE CLASSROOM INSTRUCTION? LESSONS FROM INDONESIA'S CURRICULUM REFORM IMPLEMENTATION View study ↗

6 citations

R. W. Nihayah et al. (2023)

This study examined Indonesia's curriculum reform that gave teachers more freedom to adapt their teaching to student needs and local contexts. The research found that when teachers have greater autonomy to modify curriculum and teaching methods, students become more engaged and achieve better learning outcomes. For educators, this suggests that having flexibility to tailor instruction to your specific classroom situation can significantly improve student success.

Effects of Teachers' Roles as Scaffoldingin Classroom Instruction View study ↗

4 citations

Zheren Wang (2024)

This research analysed how teachers can effectively support student learning by acting as scaffolds, providing temporary support that students gradually become independent from. Drawing on classroom examples and educational theory, the study shows how different teacher roles can guide students towards deeper understanding. Teachers will find practical insights into when and how to adjust their support levels to help students progress from dependence to independence in their learning.

R. M. Gagné's Objective-Based Instructional Model and Creativity Education: Exploring Possibilities for University Classroom Application View study ↗

Soo-dong Kim & Jung-yoon

This study explored how teaching cognitive strategies explicitly can boost creativity in college students, using a structured instructional approach that aligns teaching methods with how students actually learn. The research suggests that when teachers deliberately teach thinking strategies and ensure good retention and transfer, students develop stronger creative abilities. This finding is valuable for educators who want to creates both critical thinking skillsand creative problem-solving in their classrooms.

Online Learning Modules Based on Spacing and Testing Effects Improve Medical Student Performance on Anatomy Examinations View study ↗

1 citations

D. Baatar et al. (2017)

Medical students who used online modules designed around spaced practise and frequent testing significantly outperformed their peers on anatomy exams. The study demonstrated that breaking learning into smaller chunks delivered over time, combined with regular self-testing, leads to better long-term retention than traditional cramming methods. Teachers across all subjects can apply these findings by spacing out content delivery and incorporating frequent low-stakes quizzes to help students retain information more effectively.

Learning from errors versus explicit instruction in preparation for a test that counts. View study ↗

14 citations

Janet Metcalfe et al. (2024)

This two-year study with college students found that learning from mistakes, when combined with proper feedback, can be more effective than direct instruction for preparing students for important exams. Contrary to traditional beliefs that errors harm learning, the research shows that making and correcting mistakes actually strengthens understanding when done correctly. Teachers can use this insight to create safe spaces for students to make errors and learn from them, rather than always providing answers upfront.

Effective assessment of encoding strategies requires teachers to look beyond traditional testing methods and examine whether students are genuinely transferring information into long-term memory. Delayed retrieval assessments, administered weeks after initial instruction, provide crucial insights into encoding effectiveness that immediate quizzes cannot reveal. Hermann Ebbinghaus's forgetting curve demonstrates that without proper encoding, most information disappears within days, making these delayed assessments essential for evaluating true learning retention.

Classroom observation during encoding activities offers equally valuable assessment data. Teachers should monitor whether students are actively engaging with elaborative rehearsal techniques, making meaningful connections between concepts, or simply engaging in rote repetition. Signs of effective encoding include students asking connecting questions, drawing links to prior knowledge, and demonstrating visual or verbal organisation strategies during learning tasks.

Regular retrieval practice sessions serve both instructional and assessment purposes, allowing teachers to gauge encoding success whilst simultaneously strengthening memory consolidation. Simple techniques such as exit tickets requiring students to explain concepts in their own words, or brief weekly reviews of previously taught material, reveal which encoding strategies are working and which require reinforcement or modification in future lessons.

Effective encoding strategies must be adapted to accommodate the diverse cognitive profiles present in every classroom. John Sweller's cognitive load theory demonstrates that students with varying working memory capacities require different approaches to process and store information effectively. While some learners thrive with simultaneous visual and auditory inputs, others become overwhelmed and benefit from sequential presentation of materials. Understanding these individual differences enables educators to design encoding experiences that improve learning for all students rather than following a one-size-fits-all approach.

Practical differentiation involves offering multiple encoding pathways within the same lesson. For instance, when introducing new vocabulary, provide visual learners with graphic organisers and concept maps, whilst offering kinaesthetic learners opportunities to manipulate word cards or engage in role-play activities. Students with strong auditory processing can benefit from discussion-based encoding, whilst those requiring additional processing time should receive materials in advance. This multi-modal approach ensures that each student can access their most effective encoding channel whilst still participating in shared learning experiences.

Implementation requires systematic observation and flexible instructional design. Monitor student responses to different encoding strategies and adjust accordingly, recognising that individual preferences may vary across subjects or content complexity. Create classroom routines that naturally incorporate various encoding approaches, allowing students to self-select strategies that align with their cognitive strengths whilst gradually building competence in alternative methods.

Effective encoding strategies form the foundation of successful long-term learning, transforming how students process and retain information in their memory systems. When educators implement research-backed encoding techniques such as elaborative processing, dual coding, and spaced retrieval practise, they dramatically increase the likelihood that new knowledge will stick with students far beyond the classroom. These powerful methods work by creating multiple pathways to stored information and strengthening neural connections through strategic repetition and meaningful associations. The difference between students who remember what they learn and those who forget lies not in natural ability, but in the specific encoding techniques their teachers choose to employ.

Encoding is the process of transforming experiences into memory traces. It's the gateway to learning: without effective encoding, there's nothing to retrieve later. Yet much classroom practise focuses on exposure to information rather than active processing of it. Students read, listen, and highlight, but these passive activities often produce weak encoding that leads to rapid forgetting. Without techniques like spaced practise, even well-encoded information may not transfer effectively to long-term memory.

The good news is that decades of cognitive science research have identified evidence-based memory strategies that reliably produce stronger, more durable memories. These aren't mysterious techniques; they're practical approaches that teachers can embed into everyday instruction, often supporting self-regulated learning in the process.

Memory encoding is the transformation of experiences into neural patterns that can be stored and retrieved later. The quality of initial encoding determines how well information will be remembered, with active processing techniques producing stronger memories than passive exposure. Teachers can improve student learning by embedding evidence-based encoding strategies into everyday instruction.

| Feature | Shallow Processing | Deep Processing |

|---|---|---|

| Focus | Surface features (appearance, sound) | Meaning and connections |

| Examples | Copying notes, highlighting text, memorizing location | Explaining concepts, making connections, applying to new situations |

| Memory Strength | Weak, easily forgotten | Strong, durable memories |

| Effort Required | Low effort, fast processing | Higher effort, slower processing |

| Classroom Activities | Reading without discussion, reviewing flashcards | Explaining meaning, generating connections |

| Retention Rate | Poor long-term retention | Better retention with less review time |

Memory encoding represents the critical first stage in the learning process, determining whether information becomes accessible for future use or disappears entirely. For educators, understanding encoding fundamentals means recognising that learning is not passive absorption but an active process requiring deliberate instructional design.

The encoding process involves three key stages: attention capture, information processing, and storage pathway activation. During attention capture, students must focus on relevant information whilst filtering out distractions. Information processing then transforms this attended information through various cognitive operations, such as connecting new concepts to existing knowledge or creating mental representations. Finally, storage pathway activation determines whether information enters working memory briefly or progresses to long-term memory for permanent retention.

Effective encoding instruction requires teachers to orchestrate these stages deliberately. Rather than simply presenting information and hoping students absorb it, educators must design activities that guide attention, structure processing, and strengthen storage pathways. This approach transforms teaching from information delivery to cognitive facilitation, significantly improving student learning outcomes.

Successful classroom implementation of encoding strategies involves managing cognitive load through techniques such as chunking information into manageable segments, providing clear organisational frameworks, and using multiple sensory channels. For instance, when teaching historical events, teachers might combine visual timelines with verbal explanations and hands-on activities, allowing students to process information through different pathways. This multi-modal approach strengthens encoding by creating multiple retrieval routes whilst preventing working memory overload.

Understanding encoding fundamentals also helps educators recognise why traditional lecture-heavy approaches often fail. When students passively listen without engaging their encoding processes, information rarely transfers to long-term memory. Instead, effective teachers use interactive questioning, peer discussions, and application exercises that actively engage memory processes, ensuring robust encoding and improved retention across diverse learning contexts.

Encoding refers to the initial processing of information that creates a memory trace. When you pay attention to something, your brain converts that experience into neural patterns that can be stored and later retrieved. The nature of this processing determines how well the information will be remembered.

Think of encoding as translation. Your experiences exist in the external world; encoding translates them into the internal language of your neural networks. Poor translation produces garbled messages that are hard to understand later. Good translation produces clear representations that remain accessible over time.

Research on working memory limitations helps explain encoding constraints. Working memory can hold only a limited amount of information at once, so encoding must be selective. What receives attention gets encoded; what doesn't is lost before it reaches long-term storage. This highlights the importance of metacognitive awareness in helping students direct their attention effectively.

In classroom implementation, educators can use these multiple encoding pathways through deliberate instructional design. For instance, when teaching historical events, combining timeline visuals (visual encoding) with storytelling techniques (auditory encoding) and discussions about cause-and-effect relationships (semantic encoding) creates multiple retrieval routes for the same information. This multi-modal approach accommodates diverse learning preferences whilst strengthening memory consolidation for all students.

Working memory constraints significantly influence encoding effectiveness, particularly when cognitive load exceeds students' processing capacity. Teachers can support optimal encoding by chunking complex information into manageable segments, providing clear organisational structures, and eliminating extraneous details during initial learning phases. Additionally, encouraging students to elaborate on new information through questioning, summarising, or connecting to prior knowledge activates deeper semantic encoding processes, transforming surface-level memorisation into meaningful understanding that transfers across contexts and persists in long-term memory.

| Encoding Type | Processing Level | Student Activity | Memory Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structural Encoding | Shallow (visual features) | Noticing if a word is in capitals or what colour something is | Weak, quickly forgotten; brief retention only |

| Phonemic Encoding | Shallow (acoustic features) | Repeating information, focusing on sound or rhythm | Moderate; better than structural but still limited |

| Semantic Encoding | Deep (meaning-based) | Thinking about what information means and how it relates to prior knowledge | Strong; durable long-term memories formed |

| Elaborative Encoding | Deep (connection-building) | Creating links between new and existing knowledge through explanation | Very strong; multiple retrieval pathways created |

| Self-Referential Encoding | Deep (personal connection) | Relating information to personal experiences or oneself | Excellent; the "self-reference effect" produces superior recall |

| Organisational Encoding | Deep (structure-building) | Categorising, grouping, or structuring information hierarchically | Strong; organised information is easier to retrieve |

Based on Craik and Lockhart's Levels of Processing Theory (1972) and subsequent encoding research. The key insight: how information is processed during learning matters more than how long it's studied. Five minutes of deep processing beats twenty minutes of shallow processing.

The Levels of Processing Theory states that deeper, more meaningful processing of information leads to better memory retention than shallow processing. Shallow processing involves surface features like appearance or sound, while deep processing engages with meaning, connections, and applications. Teachers can apply this by designing activities that require students to explain, compare, or apply concepts rather than just memorize facts.

In 1972, Fergus Craik and Robert Lockhart proposed the levels of processing framework, which remains influential for understanding encoding.

Shallow processing focuses on surface features of information: what it looks like, what it sounds like. Reading words without thinking about their meaning constitutes shallow processing. So does noting that a fact appeared on page 47 without engaging with what the fact means.

Shallow processing produces weak, easily forgotten memories. It's fast and requires little effort, which is why students often default to it. But the speed comes at a cost to retention.

Deep processing engages with meaning and connections. When you think about what something means, how it relates to what you already know, or why it matters, you're processing deeply. This semantic processing creates richer, more elaborate memory traces.

Deep processing takes more effort than shallow processing, but the investment pays off in better retention. Students who spend five minutes processing deeply often remember more than students who spend twenty minutes processing shallowly.

Much traditional instruction inadvertently encourages shallow processing. Copying notes from a board, reading passages without discussion, and reviewing flashcards without explaining relationships all constitute shallow processing.

Teachers can shift towards deep processing by asking students to explain meaning, generate connections, and apply information to new situations. Any activity that requires thinking about what something means, rather than just what it looks like, promotes deep encoding.

The five most effective encoding strategies are elaborative interrogation (asking why questions), self-explanation (students explaining concepts in their own words), dual coding (combining visual and verbal information), concrete examples (linking abstract concepts to specific instances), and generation effect (having students produce information rather than just read it). These strategies work because they require active mental processing and create multiple retrieval pathways. Teachers can incorporate these by building them into lesson activities and homework assignments.

Research has identified several encoding strategies that reliably produce strong memories. These strategies can be taught explicitly and embedded into classroom routines.

Elaboration involves adding meaning and connections to new information. Rather than storing isolated facts, elaboration links new learning to existing knowledge, creating multiple retrieval pathways.

Elaboration takes many forms:

Elaborative interrogation is a specific technique that prompts students to explain why facts are true. When students generate explanations, they create elaborated memory traces that persist longer than unelaborated information.

In the classroom, build elaboration into instruction by regularly pausing to ask: "Why is this the case?" "How does this connect to what we learned last week?" "Can you think of an example from your own experience?"

Organisation involves imposing structure on information. Organised information is easier to encode and retrieve than scattered, disorganised content.

Effective organisation strategies include:

Organisation works partly by chunking information. Rather than encoding many separate items, learners encode a smaller number of organised chunks. Each chunk serves as a retrieval cue for its contents.

Teachers can support organisational encoding by making structure explicit. Don't just present information; show how it's organised. Use consistent structures across lessons so students can fit new information into familiar frameworks.

Visualisation creates mental images of information. Visual memories are distinct from verbal memories, and encoding information in both forms produces stronger retention than either alone.

Dual coding theory, developed by Allan Paivio, explains this advantage. Information encoded both verbally and visually benefits from two independent memory traces. If one trace fades, the other may remain accessible.

Visualisation strategies include:

Encourage students to create mental pictures as they learn. Ask: "Can you picture this?" "What would this look like?" "Draw what you're imagining."

Information connected to ourselves is encoded more strongly than impersonal information. This self-reference effect provides a powerful encoding strategy.

When students relate new learning to their own experiences, opinions, or goals, they process it more deeply and remember it better. The personal connection creates elaboration and emotional engagement that strengthen encoding.

Classroom applications include:

This explains why personalised examples often produce better learning than generic ones. Asking "How does this apply to your life?" produces stronger encoding than presenting the same information in decontextualised form.

Distinctive information stands out in memory. When encoding produces a unique, differentiated representation, retrieval becomes easier because the memory is less likely to be confused with similar information.

Strategies promoting distinctiveness:

When teaching similar concepts, emphasise what distinguishes them. This distinctive encoding reduces confusion and interference at retrieval.

Attention acts as the gateway to encoding because information must be consciously processed to create strong memory traces. Without focused attention, information bypasses working memory and never gets encoded into long-term storage. Teachers can support attention by minimising distractions, using attention-grabbing techniques at key moments, and breaking lessons into shorter segments with clear focus points.

Encoding requires attention. Information that doesn't receive attention cannot be encoded, no matter how long it's presented. This makes attention the gateway to all learning.

Classrooms present multiple stimuli competing for attention. Students must selectively attend to relevant information while ignoring distractions. Teachers can support selective attention by clearly signalling what's important and reducing competing stimuli.

Learning requires maintaining attention over time. Attention naturally fluctuates, with most students showing declining focus after 10-20 minutes. Varying instructional activities, building in movement, and strategic timing of key content helps maintain attention throughout lessons.

When attention is divided between multiple demanding tasks, encoding of each task suffers. Students who check their phones during instruction encode less than those who focus completely. Similarly, overly complex instruction that demands attention to multiple elements simultaneously can overwhelm attention capacity.

Research on cognitive load theoryaddresses how instructional design affects attention and encoding. Managing cognitive load ensures sufficient attention remains available for encoding target content.

Working memory can only hold about 4-7 chunks of information at once, creating a bottleneck for encoding new material into long-term memory. When working memory is overloaded, encoding quality suffers and students struggle to form lasting memories. Teachers can accommodate these limits by chunking information into meaningful units, providing scaffolding, and allowing processing time between new concepts.

Working memory is the cognitive system that holds and manipulates information during encoding. It serves as the workspace where new information is processed before entering long-term memory.

Working memory has severe capacity limitations. Most people can hold only 3-5 chunks of information simultaneously. When encoding demands exceed working memory capacity, some information is lost.

Teachers can support encoding by breaking content into manageable chunks. Present a few ideas at a time, allow processing before moving on, and don't overload working memory with unnecessary complexity.

Deep processing requires working memory resources. If working memory is overwhelmed by too much information, students default to shallow processing because they lack the capacity for deeper engagement.

Reduce extraneous cognitive loadto free resources for encoding. Eliminate unnecessary complexity, ensure materials are well-designed, and provide scaffolds that reduce working memory burden.

Students with relevant prior knowledge can encode new information more efficiently because they can chunk it into existing schemas. This is why activating prior knowledge at the start of lessons supports encoding: it prepares mental structures to receive new information.

Encoding and retrieval are interconnected processes where the way information is initially encoded determines how easily it can be retrieved later. Strong encoding creates multiple retrieval cues and pathways, while poor encoding leaves few ways to access the memory. Teachers should align encoding activities with how students will need to retrieve and use the information, such as encoding math concepts through problem-solving if that's how they'll be tested.

Encoding and retrieval are intimately connected. The conditions at encoding shape what retrieval cues will be effective later. This principle, called encoding specificity, has important implications for learning.

Information is encoded along with context: where you learned it, what you were thinking, what was happening around you. These contextual elements become linked to the memory and can serve as retrieval cues.

This explains why students sometimes perform better in the room where they learned material, or why returning to a topic can trigger recall of related information. The context provides cues that access the encoded memory.

Retrieval is most successful when it matches the type of processing used during encoding. If you encoded information by thinking about its meaning, tests that require meaning-based retrieval will succeed. If you encoded by rote repetition, meaning-based questions may fail even though the information is stored.

This principle suggests that encoding should match anticipated retrieval. If students will need to apply concepts to novel problems, they should practise application during encoding. If they will need to recall factual details, they should encode those details specifically.

These evidence-based encoding strategies help teachers design instruction that creates durable, retrievable memories. When students process information deeply during initial learning, they build strong memory traces that resist forgetting and transfer flexibly to new situations.

The research on encoding is unambiguous: quality of initial processing determines quality of later memory. Teachers who understand encoding design instruction that engages students' minds actively with meaning and connections, not just passive exposure to information. The key question isn't "Did students see this content?" but "Did students process it deeply enough to remember it?" Every instructional choice either promotes or undermines effective encoding - choose activities that require thinking about meaning, and memories will follow.

Different subjects benefit from specific encoding strategies based on the type of information being learned. Math and science benefit from worked examples and visual representations, while language arts benefits from elaboration and making connections to prior texts. History and social studies encoding improves through timeline creation and cause-effect mapping, demonstrating that teachers should match encoding techniques to their content area.

Effective encoding strategies vary somewhat across subject areas, reflecting different knowledge structures and learning goals.

Science encoding benefits from:

Visual encoding is particularly important in science, where processes, structures, and relationships benefit from diagrammatic representation.

Mathematical encoding benefits from:

Mathematics requires encoding both procedures and the concepts that underpin them. Encoding procedures without understanding leads to fragile, inflexible knowledge.

Historical encoding benefits from:

Historical understanding requires encoding events within causal narratives, not as isolated facts.

Language encoding benefits from:

Vocabulary instruction is most effective when words are encoded through meaningful use rather than isolated memorisation.

Teachers can help students understand encoding by explaining how memory works using simple analogies and demonstrating the difference between passive reading and active processing. Show students specific encoding techniques like self-testing and elaboration, then provide guided practise with AI-enhanced feedback. Regular metacognitive discussions about which strategies work best for different types of content help students become independent learners.

Helping students understand encoding supports metacognition and independent learning. Students who understand how memory works can adopt more effective study strategies.

Students often rely on shallow processing (re-reading, highlighting) because it feels productive. Teaching the distinction between shallow and deep processing helps students understand why these strategies often fail.

Demonstrate encoding strategies explicitly. Show students how to elaborate, organise, and visualise. Think aloud while encoding to make these processes visible.

Give students structured opportunities to practise encoding strategies with feedback. Initially scaffold the strategies, then gradually release responsibility as students develop competence.

Use prompts that encourage students to monitor their encoding:

Effective classroom routines that support encoding include starting lessons with retrieval practise of previous material, using think-pair-share for active processing, and ending with exit tickets that require elaboration. Build in regular brain breaks to prevent cognitive overload and establish consistent patterns for introducing new concepts. These routines create predictable opportunities for deep processing without adding extra planning burden.

Embedding encoding strategies in classroom routines ensures consistent application.

Begin lessons by activating prior knowledge relevant to new content. This prepares schemas for encoding and creates connection points for new information.

Pause regularly to prompt encoding. After presenting key concepts, ask students to explain, visualise, connect, or apply. These encoding activities take minimal time but substantially improve retention.

End lessons with activities that consolidate encoding. Summarisation, connection-making, and retrieval practise all strengthen the memories formed during the lesson.

Timing these encoding routines strategically throughout the school day maximises their effectiveness. Morning lessons benefit from 'memory bridge' activities where students spend the first five minutes connecting previous day's learning to current objectives through quick verbal sharing or written reflections. This primes their cognitive systems for optimal information processing. Similarly, post-break transitions offer valuable encoding opportunities - rather than diving straight into new content, use two-minute recap discussions to reactivate dormant neural networks from earlier lessons.

Physical movement can significantly enhance these daily encoding routines. Incorporate 'walk and talk' moments where students move around the classroom whilst discussing key concepts, or use simple gestures to represent important ideas. Research demonstrates that motor activity during learning strengthens memory consolidation pathways. Additionally, vary your encoding strategies across different subjects - use visual organisers for complex topics, rhythmic patterns for sequential information, and storytelling techniques for abstract concepts. This variety prevents cognitive habituation whilst catering to diverse learning preferences, ensuring consistent memory encoding throughout your instructional day.

Successful transfer from encoding to long-term retention requires spaced practise, where students revisit material at increasing intervals over time. Interleaving different topics during practise sessions strengthens memory consolidationbetter than b locked practise. Teachers should design review cycles that bring back previously encoded material in new contexts, forcing reprocessing that strengthens memory traces.

Encoding is necessary but not sufficient for lasting learning. Strong encoding provides the foundation, but consolidation and retrieval practise are also required for durable retention.

A complete approach to memory combines:

Teachers who address all three processes maximise their impact on long-term learning.

The transfer from working memory to long-term memory requires specific conditions that teachers can deliberately create. Spaced repetition proves most effective, with information reviewed at increasing intervals rather than massed practice. Introduce concepts initially, revisit them within 24 hours, then again after three days, one week, and one month for optimal retention.

Meaningful connections accelerate this transfer process. When students link new information to existing knowledge, personal experiences, or cross-curricular content, multiple neural pathways form, creating redundant storage systems. Encourage students to explain how new concepts relate to their lives or previous learning, strengthening these connective pathways.

Elaborative encoding strategies further enhance long-term retention by requiring deeper cognitive processing. Rather than simple rehearsal, students should engage with material through questioning, summarising, and teaching others. For instance, having students create concept maps or analogies forces them to process information meaningfully rather than superficially, promoting robust memory formation.

Sleep and consolidation time also play crucial roles in long-term transfer. Avoid cramming multiple new concepts into single lessons. Instead, introduce key ideas with sufficient processing time, allowing the brain's natural consolidation processes to work overnight. This spacing gives the hippocampus time to replay and strengthen memories, facilitating successful long-term storage and retrieval when needed.

Begin by replacing passive activities with active ones, such as turning reading assignments into guided note-taking with specific prompts for elaboration. Start each lesson with a brief retrieval practise of yesterday's content and end with students explaining one key concept to a partner. Choose one encoding strategy to master at a time, implementing it consistently for several weeks before adding another.

Begin improving encoding in your classroom with these manageable changes.

Ask "why" and "how" questions that require explanation rather than recognition. Every lesson should include moments where students must explain concepts in their own words.

Use graphic organisers to support organisational encoding. Maps, webs, and hierarchies help students see and encode structure.

Connect to prior knowledge explicitly at lesson beginnings. Activating relevant schemas prepares the cognitive context for new encoding.

Reduce cognitive load by chunking information and eliminating unnecessary complexity. What remains should receive full processing attention.

Build encoding pauses into instruction. After presenting key content, stop and prompt encoding activity before moving on.

These strategies don't require additional time. They redirect existing instructional time towards activities that produce genuine learning rather than the illusion of understanding.

Essential research includes Craik and Lockhart's levels of processing framework, Roediger and Karpicke's work on the testing effect, and Dunlosky's review of effective learning techniques. These foundational papers provide evidence for why certain encoding strategies work and how to implement them effectively. Teachers can access practical summaries through organisations like the Learning Scientists and Retrieval Practise websites.

The following papers provide deeper exploration of encoding and its educational applications.

This foundational paper introduced the levels of processing framework that transformed memory research. The authors argued that memory depends on depth of processing during encoding, with semantic processing producing superior retention. The paper launched extensive research on how encoding strategies affect learning.

This research established elaborative interrogation as an effective encoding strategy. The authors found that prompting students to explain why facts are true substantially improved memory for those facts. The technique works by generating elaborated connections between new and existing knowledge.

This comprehensive review evaluated ten learning techniques including several encoding strategies. Elaborative interrogation and self-explanation received positive ratings, while commonly used strategies like highlighting and re-reading were rated as less effective.

Allan Paivio explains dual coding theory and its educational implications. The paper describes how combining verbal and visual encoding produces stronger memories than either alone, supporting the use of diagrams, imagery, and multimedia in instruction.

While focused on retrieval, this paper demonstrates how encoding and retrieval interact. The research shows that retrieval practise produces better retention than elaborative studying, highlighting the importance of active processing over passive review.

Experiences are transformed through the process of encoding into memory traces that can be stored and retrieved later. Without effective encoding, there's nothing for students to retrieve from memory, making it the gateway to all learning. The quality of initial encoding determines how well information will be remembered, regardless of how many times students review it afterwards.

Teachers can promote deep processing by asking students to explain meaning, generate connections, and apply information to new situations rather than just copying notes or highlighting text. Build regular pauses into lessons to ask questions like 'Why is this the case?' or 'How does this connect to what we learned last week?' Any activity that requires thinking about what something means, rather than just what it looks like, promotes deep encoding.

The five most effective strategies are elaborative interrogation (asking why questions), self-explanation (students explaining concepts in their own words), dual coding (combining visual and verbal information), concrete examples (linking abstract concepts to specific instances), and the generation effect (having students produce information rather than just read it). These strategies work because they require active mental processing and create multiple retrieval pathways in memory.

These activities constitute shallow processing, which focuses only on surface features like appearance rather than meaning and connections. Shallow processing produces weak, easily forgotten memories because it requires minimal mental effort and creates limited retrieval pathways. Students who spend five minutes processing deeply often remember more than those who spend twenty minutes processing shallowly.

Elaborative interrogation involves prompting students to explain why facts are true, which creates elaborated memory traces that persist longer than unelaborated information. Teachers can build this into instruction by regularly asking questions like 'Why is this the case?', 'How does this connect to previous learning?', or 'Can you think of an example from your own experience?' This technique helps students link new information to existing knowledge, creating multiple retrieval pathways.

Organisation involves imposing structure on information, making it easier to encode and retrieve than scattered, disorganised content. It works by chunking information into smaller, structured units where each chunk serves as a retrieval cue for its contents. Teachers can support organisational encoding by making structure explicit and using consistent frameworks across lessons so students can fit new information into familiar patterns.

Dual coding theory explains that information encoded both verbally and visually benefits from two independent memory traces, producing stronger retention than either form alone. If one memory trace fades, the other may remain accessible, providing students with multiple pathways to retrieve information. Teachers should combine visual and verbal information presentation to take advantage of this dual encoding benefit.

These peer-reviewed studies provide the research foundation for the strategies discussed in this article:

HOW DOES GRANTING TEACHER AUTONOMY INFLUENCE CLASSROOM INSTRUCTION? LESSONS FROM INDONESIA'S CURRICULUM REFORM IMPLEMENTATION View study ↗

6 citations

R. W. Nihayah et al. (2023)

This study examined Indonesia's curriculum reform that gave teachers more freedom to adapt their teaching to student needs and local contexts. The research found that when teachers have greater autonomy to modify curriculum and teaching methods, students become more engaged and achieve better learning outcomes. For educators, this suggests that having flexibility to tailor instruction to your specific classroom situation can significantly improve student success.

Effects of Teachers' Roles as Scaffoldingin Classroom Instruction View study ↗

4 citations

Zheren Wang (2024)

This research analysed how teachers can effectively support student learning by acting as scaffolds, providing temporary support that students gradually become independent from. Drawing on classroom examples and educational theory, the study shows how different teacher roles can guide students towards deeper understanding. Teachers will find practical insights into when and how to adjust their support levels to help students progress from dependence to independence in their learning.

R. M. Gagné's Objective-Based Instructional Model and Creativity Education: Exploring Possibilities for University Classroom Application View study ↗

Soo-dong Kim & Jung-yoon

This study explored how teaching cognitive strategies explicitly can boost creativity in college students, using a structured instructional approach that aligns teaching methods with how students actually learn. The research suggests that when teachers deliberately teach thinking strategies and ensure good retention and transfer, students develop stronger creative abilities. This finding is valuable for educators who want to creates both critical thinking skillsand creative problem-solving in their classrooms.

Online Learning Modules Based on Spacing and Testing Effects Improve Medical Student Performance on Anatomy Examinations View study ↗

1 citations

D. Baatar et al. (2017)

Medical students who used online modules designed around spaced practise and frequent testing significantly outperformed their peers on anatomy exams. The study demonstrated that breaking learning into smaller chunks delivered over time, combined with regular self-testing, leads to better long-term retention than traditional cramming methods. Teachers across all subjects can apply these findings by spacing out content delivery and incorporating frequent low-stakes quizzes to help students retain information more effectively.

Learning from errors versus explicit instruction in preparation for a test that counts. View study ↗

14 citations

Janet Metcalfe et al. (2024)

This two-year study with college students found that learning from mistakes, when combined with proper feedback, can be more effective than direct instruction for preparing students for important exams. Contrary to traditional beliefs that errors harm learning, the research shows that making and correcting mistakes actually strengthens understanding when done correctly. Teachers can use this insight to create safe spaces for students to make errors and learn from them, rather than always providing answers upfront.