Resentment and Teacher Burnout: Recognising the Warning Signs

Feeling drained but can't pinpoint why? Explore the hidden link between resentment and teacher burnout, plus gentle strategies for recovery.

Feeling drained but can't pinpoint why? Explore the hidden link between resentment and teacher burnout, plus gentle strategies for recovery.

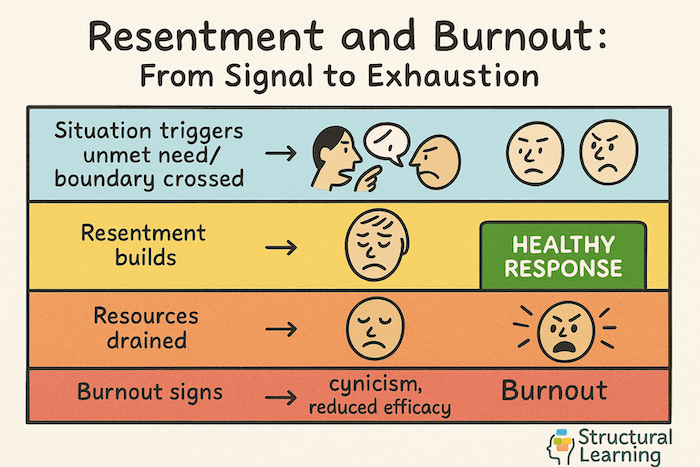

We often think of burnout as exhaustion from working too hard. Too many emails, too many deadlines, too much of everything. But quietly, tucked underneath the busy-ness and stress, another feeling can be growing. Not loud, not obvious, but slowly and steadily building. It's resentment.

Let's just take a moment with that.

Resentment is one of those emotions that doesn't always shout. Sometimes it simmers. It's a mix: anger, frustration, disappointment, a sense of being wronged or let down. You might not even notice it at first. But it sticks. It lingers. And left unchecked, it can weigh you down more than you realise.

According to the APA Dictionary of Psychology, resentment is "a feeling of persistent ill will or anger due to a perceived insult or injustice." For me, that word persistent is key. It's not always big or dramatic, but it lasts.

We might hold onto resentment as a shield. A way to protect ourselves from sadness. Or to stop us from having to let go. Either way, it takes up space, emotional space.

Unlike temporary frustration or disappointment, resentment becomes a persistent emotional state that colours how teachers view their work, colleagues, and students. It often manifests as a sense of unfairness - feeling that one's efforts go unrecognised whilst others seem to coast by with less responsibility.

The distinction between healthy frustration and damaging resentment lies in duration and intensity. Frustration typically motivates action or fades with time, but resentment festers. It creates what psychologists call 'rumination cycles' - repetitive thoughts about perceived injustices that actually strengthen negative emotions rather than resolving them. For teachers, this can transform what was once a fulfiling vocation into a source of chronic stress and cynicism.

Addressing resentment matters profoundly because it directly impacts both teacher wellbeing and student outcomes. Research shows that teachers experiencing chronic resentment demonstrate reduced empathy, decreased classroom engagement, and higher rates of burnout. Students, remarkably attuned to emotional atmospheres, often mirror their teacher's underlying attitudes. When resentment takes hold in educational settings, it creates ripple effects that extend far beyond individual professional experience, potentially affecting entire school cultures and student learning environments.

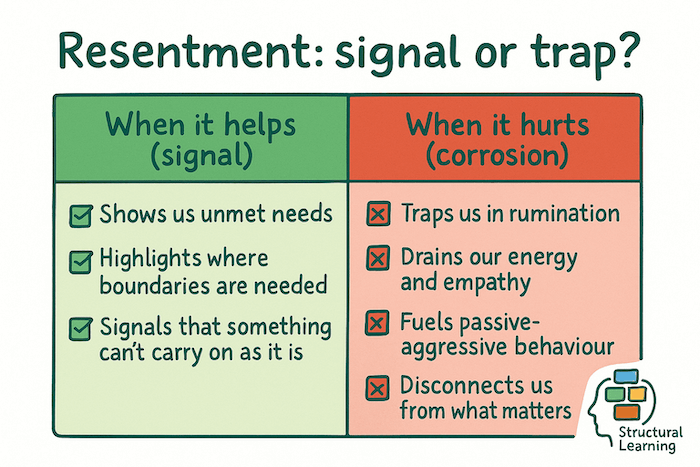

Absolutely, yes. Like most emotions, resentment has a message. It tells us that something's off. That a boundary has been crossed. That our values are being nudged, maybe even ignored. Psychology Today puts it beautifully: it may have a bad name, but it keeps us safe. It helps us notice the wrongdoing. It might even push us towards making a change.

In that way, it can be part of a healing process.

But, if we don't notice it or do something with it, resentment turns stale. It festers. It stops being protective and starts being corrosive.

When Resentment Helps

When Resentment Hurts

Sometimes, resentment doesn't come out as a full confession. It slips into our everyday words:

"Why am I always the one who has to…?" "No one even notices what I do." "They just expect me to pick up the slack." "I'm running on empty but no one cares." "It's not fair."

Listen out for these types of phrases. Are you using them a lot? They're little flares. Signs that something deeper is stirring if being used frequently. These statements reflect a simmering sense of being taken for granted. The impact of feeling this over a prolonged period can lead to teacher burnout.

The frequency and intensity of negative language patterns can serve as early warning signs of deepening resentment. When casual staffroom conversations consistently centre on what's wrong rather than what's working, or when teachers find themselves using absolutes like 'always' and 'never' to describe colleagues, pupils, or leadership, it suggests that resentment is becoming entrenched. This linguistic shift matters because the words we use don't just reflect our feelings - they actively reinforce them, creating cycles where negative language strengthens negative emotions.

Recognising these patterns offers opportunities for intervention in educational settings. Teachers might notice when their internal dialogue becomes dominated by complaints, or when they struggle to recall recent positive interactions with pupils or colleagues. Simple practices like ending each day by identifying one thing that went well, or consciously reframing generalised frustrations into specific, solvable problems, can help interrupt the cycle. The goal isn't to suppress legitimate concerns about classroom practice or school environment, but to prevent resentment from becoming the default lens through which all professional experiences are viewed.

Resentment doesn't appear overnight. It is an emotion, and it is information. It's usually a cumulative emotional response to unmet needs, ignored boundaries, and prolonged imbalance. Common causes include:

Chronic Overfunctioning, You're doing too much, too often, with too little return.

Lack of Boundaries, You say "yes" even when your gut says "please say no."

Unspoken Expectations, Hoping others just know what you need or want.

People-Pleasing, Putting others' needs ahead of your own, over and over again.

Perceived Injustice, Watching others be recognised while you stay invisible.

Understanding these patterns is part of reflective practise, which helps teachers develop greater emotional intelligence.

The physical and emotional demands of teaching, combined with inadequate resources, create a perfect storm for resentment. When teachers face overcrowded classrooms, outdated materials, or insufficient support staff, the daily struggle to maintain educational standards becomes overwhelming. This frustration intensifies when school leadership appears disconnected from classroom realities, making decisions that teachers know will be difficult or impossible to implement effectively.

Communication breakdowns within school hierarchies further fuel these negative feelings. Teachers often report feeling that their concerns about student needs, curriculum changes, or workplace conditions are either ignored or dismissed. When feedback flows only downward and professional experience isn't valued in decision-making processes, educators can develop a sense of powerlessness that transforms into resentment over time. The situation becomes more pronounced when teachers observe resources being allocated to initiatives they consider ineffective, whilst essential classroom needs remain unmet.

Resentment is more than a feeling. It's a drain on internal resources. When it becomes chronic, it wears down our capacity for empathy, creativity, and motivation. It narrows our perspectives and keeps us linked to the past. This emotional burden can significantly impact our wellbeing and ability to connect with students. Bearing in mind our pull towards negativity bias, it can leave us struggling to maintain the resilience needed for effective teaching. The resulting disconnection often affects our classroom management and reduces our engagement with both students and colleagues. When we're caught in these cycles, even implementing basic educational strategies like scaffolding becomes more challenging. Supporting students with special educational needs requires additional emotional capacity that resentment can erode. Developing self-regulation skills - both for ourselves and our students - becomes crucial for breaking these patterns and developing healthier social-emotional learning environments.

The physiological impact of sustained resentment compounds these psychological effects. Research by Dr. Charlotte vanOyen Witvliet demonstrates that holding onto grievances triggers chronic stress responses, improving cortisol levels and disrupting sleep patterns. For teachers, this manifests as Sunday night anxiety, difficulty switching off after school, and that familiar feeling of being 'emotionally drained' even during holidays. The constant activation of stress hormones impairs memory consolidation and creative problem-solving - precisely the cognitive functions teachers rely upon for effective classroom practice.

Perhaps most concerning is how resentment distorts professional relationships through what psychologists call 'attribution bias'. Teachers experiencing burnout-related resentment begin interpreting neutral interactions negatively, seeing criticism where none exists or assuming malicious intent from leadership decisions. This creates isolation within school communities precisely when collegial support becomes most crucial. The resulting workplace tension feeds back into the resentment cycle, as strained relationships provide fresh grievances to nurture.

Breaking this cycle requires recognising that resentment is not simply an emotional response but a cognitive habit that can be interrupted. Simple strategies like the 'two-minute rule' - consciously redirecting thoughts when resentful rumination begins - can help preserve mental resources for more constructive educational focus.

The distinction between productive and destructive resentment becomes particularly evident in everyday classroom practice. For instance, a teacher feeling resentful about inadequate resources might channel this emotion into researching grant opportunities, collaborating with colleagues to share materials, or presenting evidence-based proposals to school leadership. This transforms initial frustration into meaningful professional advocacy that benefits both teacher wellbeing and student outcomes.

Educational settings often provide natural opportunities for this transformation. When teachers feel resentful about excessive marking loads, productive responses might include exploring peer assessment strategies, implementing focused feedback techniques, or working with department heads to establish more sustainable marking policies. The school environment becomes a space for collaborative problem-solving rather than isolated grievance.

The crucial factor is timeframe and action orientation. Healthy resentment serves as a temporary signal - alerting teachers to problems that require attention, then dissolving once constructive steps are taken. When resentment persists despite efforts to address underlying issues, it may indicate deeper systemic problems requiring professional support or significant changes to one's educational context. Teachers must learn to recognise when their professional experience is being enriched versus diminished by these emotional responses.

Recognising the early warning signs of resentment requires honest self-reflection about your emotional responses to everyday classroom situations. Christina Maslach's seminal research on burnout reveals that resentment often manifests as cynical thoughts about students, colleagues, or the education system itself. Ask yourself: Do you find yourself frequently criticising pupils' behaviour rather than seeking solutions? Are you increasingly irritated by colleagues' requests for collaboration? These subtle shifts in perspective often precede more serious burnout symptoms.

Physical and behavioural indicators provide equally important clues about your professional wellbeing. Teachers experiencing early-stage resentment commonly report feeling drained after interactions that previously energised them, such as parent consultations or staff meetings. You might notice yourself avoiding the staffroom, declining invitations to school events, or feeling genuinely relieved when pupils are absent. Sleep disruption, particularly ruminating about school issues, often accompanies these behavioural changes.

Implementing a weekly emotional check-in can help identify concerning patterns before they become entrenched. Consider rating your enthusiasm for teaching on a scale of one to ten each Friday, noting specific triggers that affected your score. When ratings consistently fall below your personal baseline, it's time to seek support from colleagues, mentors, or school leadership before resentment undermines your classroom practice.

Transforming resentment into resilience requires deliberate strategies that address both immediate emotional responses and long-term professional wellbeing. Research by Kristin Neff on self-compassion shows that teachers who practice kind, non-judgemental self-talk recover more quickly from challenging classroom situations. When you notice resentment building, pause and ask: "What would I tell a colleague facing this same situation?" This simple reframe activates the supportive voice you naturally use with others, breaking the cycle of self-criticism that fuels professional burnout.

Boundary-setting becomes crucial in educational settings where demands often exceed capacity. Start small by identifying one non-essential task you can delegate, decline, or modify this week. Albert Bandura's work on self-efficacy demonstrates that teachers who feel control over their professional environment experience significantly less emotional exhaustion. This might mean closing your laptop at a specific time each evening or designating Sunday as a work-free day.

Finally, cultivate what researchers call "micro-recovery" moments throughout your teaching day. Between lessons, practice three deep breaths or mentally acknowledge one thing that went well in the previous class. These brief interventions, supported by occupational psychology research, help prevent the accumulation of daily stresses that typically manifest as resentment towards students, colleagues, or the education system itself.

School leaders hold the key to transforming toxic environments that breed resentment into thriving communities that sustain teacher wellbeing. Research by Christine Maslach on organisational factors in burnout reveals that workplace fairness, manageable workloads, and meaningful recognition are far more powerful predictors of job satisfaction than individual resilience training. Leaders must move beyond surface-level wellness initiatives to address the structural issues that leave teachers feeling undervalued and overwhelmed.

Creating genuine support starts with establishing transparent communication channels where teachers can voice concerns without fear of judgment. Regular one-to-one meetings focused on professional growth rather than compliance, collaborative decision-making processes that include classroom practitioners, and clear, consistent policies around behaviour management all contribute to a sense of agency and respect. When teachers feel heard and valued as professionals, resentment struggles to take root.

Most importantly, school leaders must model the behaviour they wish to see throughout their organisation. This means acknowledging mistakes openly, celebrating both small wins and major achievements, and protecting teaching time from unnecessary interruptions. Simple actions like providing adequate resources, respecting planning time, and offering genuine appreciation for daily efforts create ripple effects that strengthen the entire school culture.

Recognising when professional support is needed requires honest self-reflection about the severity and persistence of resentment in your educational practice. If feelings of bitterness towards students, colleagues, or the school system are affecting your classroom effectiveness for more than a few weeks, or if you're experiencing physical symptoms like chronic fatigue, headaches, or sleep disturbances, it's time to seek additional help. Warning signs include finding yourself consistently negative about teaching, avoiding professional development opportunities, or feeling emotionally detached from students' progress.

Several support options are available within educational settings and beyond. Your school's employee assistance programme often provides confidential counselling services specifically designed for workplace stress. Teaching unions offer professional support and guidance, whilst occupational health services can address both physical and psychological aspects of teacher wellbeing. Additionally, seeking support from a qualified therapist or counsellor who understands educational environments can provide valuable strategies for managing resentment and rebuilding professional satisfaction.

Remember that seeking help demonstrates professional responsibility, not weakness. Early intervention prevents more serious burnout and protects both your wellbeing and your students' educational experience. Consider reaching out when self-help strategies aren't providing relief within a reasonable timeframe, typically four to six weeks of consistent effort.