Teaching Wisdom: Timeless Principles for Effective Education

Discover timeless teaching principles that truly work. Learn from experienced educators about what matters most in the classroom and why it endures.

Discover timeless teaching principles that truly work. Learn from experienced educators about what matters most in the classroom and why it endures.

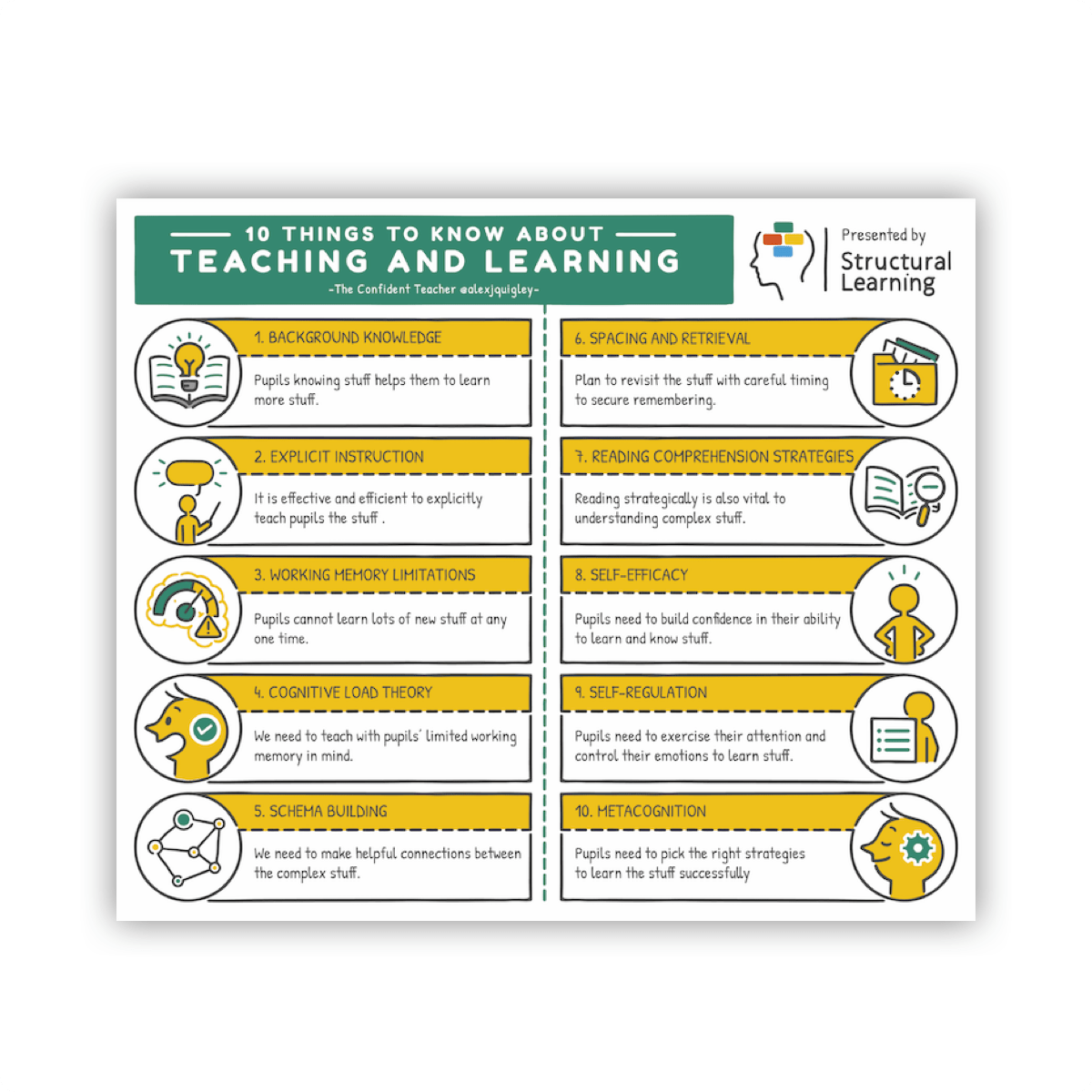

Effective teaching is based on evidence from cognitive scienceand educational psychology, not mysterious talent or instinct. The core principles include focusing on student thinking, building strong knowledge foundations, using explicit instruction, and implementing deliberate practise with feedback. These research-backed strategies work consistently across different subjects and age groups.

Effective teaching is not mysterious or dependent on innate talent. Decades of research in cognitive science, educational psychology, and classroom studies have identified principles that consistently support learning across subjects and age groups. These principles often contradict popular assumptions but provide a reliable foundation for instructional decisions.

Alex Quigley, a former English teacher and Director of Huntington Research School, distilled key insights from educational research into accessible principles that every teacher can apply. His work, along with contributions from researchers like Barak Rosenshine, John Sweller, and Robert Bjork, provides a framework for thinking about teaching strategiesthat cuts through educational fads.

Students remember what they actively think about during lessons, not necessarily what teachers intend them to learn. If students spend time thinking about irrelevant details like decorating a poster rather than the content, they will remember the decoration process instead. Teachers must design activities that direct student thinking towards the key learning objectives.

Daniel Willingham's observation that "memory is the residue of thought" has profound implications for teaching. Students remember what they think about during a lesson, not what the teacher intended them to think about. If students spend a lesson thinking about how to decorate a poster rather than the historical concepts it represents, they will remember poster design, not history.

This principle suggests teachers should constantly ask: "What will students actually be thinking about during this activity?" Activities that are engaging but cognitively unfocused, such as elaborate games or competitive elements, may be remembered for the wrong reasons. The most effective activities are those where thinking about the content is unavoidable.

Critical thinking, problem-solving, and creativity all depend on having rich background knowledge in the subject area. Students cannot think critically about topics they know little about because thinking skills are not separate from content knowledge. Building strong knowledge foundations enables students to analyse, evaluate, and create effectively.

A persistent myth suggests that teaching knowledge is outdated because students can "just look things up." Research consistently contradicts this. Working memory, where conscious thinking occurs, can only hold a limited amount of information. Background knowledge stored in long-term memory frees up working memory for higher-order thinking.

Expert chess players can remember board positions that beginners cannot because they recognise patterns rather than individual pieces. Similarly, students with rich vocabulary can focus on comprehension rather than decoding. Teaching knowledge is not opposed to teaching thinking, it is the precondition for it.

Research consistently shows that clear explanations, worked examples, and guided practise lead to better learning outcomes than discovery-based approaches for most objectives. Explicit instruction reduces cognitive load and provides students with accurate mental models before they practise independently. This structured approach helps students learn more efficiently and avoid developing misconceptions.

Barak Rosenshine's Principles of Instruction synthesise decades of research on effective teaching. The findings consistently favour explicit instruction: clear explanations, worked examples, guided practise with feedback, and independent practise. This is especially true for novice learners who lack the background knowledge to benefit from discovery approaches.

This does not mean lecturing without student involvement. Effective explicit instruction involves constant checking for understanding, high-frequency questioning, and scaffolded practise. The goal is to reduce cognitive load by providing clear guidance rather than expecting students to discover insights independently.

Teachers can manage cognitive load by breaking complex tasks into smaller steps and presenting information in chunks that match students' processing capacity. Remove unnecessary distractions from learning materials and use worked examples to demonstrate procedures before asking students to solve problems independently. Gradually increase complexity as students develop expertise.

John Sweller's Cognitive Load Theory explains why some lessons overwhelm students while others enable learning. Working memory is limited, and presenting too much new information simultaneously causes cognitive overload. Effective teaching sequences information carefully, builds on prior knowledge, and uses techniques like worked examples and dual coding(words plus images) to reduce unnecessary load.

Split attention, where students must mentally integrate information from multiple sources, increases load. Placing labels directly on diagrams rather than in separate legends, and synchronising speech with visuals, reduces this burden. These seemingly small design decisions significantly impact learning.

Retrieval practise strengthens memory by requiring students to actively recall information rather than passively reviewing it. Regular quizzing, self-testing, and practise problems force the brain to reconstruct knowledge, making it more durable and accessible. This active retrieval is more effective than re-reading or highlighting for long-term retention.

Testing is not just for assessment, it is one of the most powerful learning strategies available. The act of retrieving information from memory strengthens the memory trace more effectively than re-reading or re-studying. This "testing effect" has been replicated across hundreds of studies.

Low-stakes quizzing at the start of lessons, flashcard practise, and asking students to write everything they remember about a topic before reviewing notes all harness retrieval practise. The effort involved in retrieval, even when partially unsuccessful, is precisely what makes it effective.

Spaced practise distributes learning over time rather than concentrating it in single sessions, leading to better long-term retention. The forgetting that occurs between practise sessions actually strengthens memory when information is successfully retrieved again. Teachers should revisit important concepts multiple times across weeks and months rather than covering them intensively once.

Distributed practise, where study sessions are spaced over time, produces better long-term retention than massed practise, where the same total time is spent in one session. This spacing effect is one of the most strong findings in learning science, yet school schedules often work against it.

Teachers can build spacing into their practise by regularly revisiting previous topics, interleaving practise of different skills, and designing cumulative assessments that require retrieval of material from earlier in the course. The forgetting that occurs between sessions is not a bug but a feature, the effort of re-learning is what builds durable memory.

Effective feedback must be specific, timely, and include opportunities for students to act on it immediately. Simply marking errors without giving students time to correct them wastes the learning potential of feedback. Teachers should build in dedicated time for students to respond to feedback and improve their work based on the guidance provided.

Feedback is only effective when students use it to improve. Detailed written comments that students glance at before filing away have limited impact. Effective feedback systems build in structured time for students to respond to feedback, revise their work, or demonstrate improvement.

The timing and focus of feedback also matter. Immediate feedback on practise activities helps students correct errors before they become ingrained. Feedback should focus on the task and how to improve rather than on the learner's personal qualities.

Student motivation typically follows from experiencing success rather than preceding it, contrary to popular belief. When students master skills and understand content, they become more motivated to continue learning in that area. Teachers should structure lessons to ensure all students experience regular success through appropriate challenge levels and scaffolding.

A common assumption is that learning should be made fun to motivate students. Research suggests the relationship often works the other way: students become motivated when they experience success and develop competence. Reducing challenge in pursuit of engagement may actually undermine motivation.

This suggests prioritising high expectations, effective instruction, and the satisfaction of genuine achievement over entertainment value. When students understand material, can answer questions correctly, and see themselves improving, motivation follows naturally.

Reading comprehension underlies success in every academic subject because it enables students to independently access knowledge and continue learning. Strong readers can learn from textbooks, online resources, and other materials without constant teacher support. Developing reading skills, including vocabulary and background knowledge, should be a priority across all subject areas.

Reading underpins success across all subjects. Students who read widely develop larger vocabularies, more background knowledge, and greater reading fluency, creating a virtuous cycle. Those who struggle to read fall further behind as the reading demands of the curriculum increase.

This makes systematic phonics instruction in early years, explicit vocabulary teaching throughout school, and substantial reading practise essential priorities. Teachers across all subjects can support reading development by teaching subject-specific vocabulary and using reading strategies like reciprocal reading.

Effective teachers continuously update their practise based on research evidence and reflection on student outcomes. Professional development should focus on understanding the science of learning and translating research into classroom applications. Teachers benefit from collaborating with colleagues to test and refine evidence-based strategies in their specific contexts.

Effective teaching is complex, and no initial training can fully prepare teachers for every situation they will encounter. The best teachers maintain a stance of inquiry, engaging with research, reflecting on their practise, and seeking feedback from colleagues and students.

Professional learning communities, lesson study, and engagement with educational research all support ongoing development. The principles outlined here are not fixed prescriptions but starting points for thoughtful professional judgement.

Start by selecting one or two principles that address current classroom challenges and implement them systematically. Monitor student learningoutcomes to assess effectiveness and adjust implementation based on results. Gradually incorporate additional principles while maintaining successful practices, building a coherent approach grounded in learning science.

| Principle | Common Pitfall | Evidence-Informed Alternative |

|---|---|---|

| Memory is residue of thought | Engaging activities that distract from content | Activities where thinking about content is unavoidable |

| Knowledge enables thinking | Teaching "skills" without building knowledge | Systematic knowledge building before complex tasks |

| Explicit instruction works | Expecting students to discover key insights | Clear explanations with worked examples |

| Manage cognitive load | Presenting too much new information at once | Sequencing information and using dual coding |

| Retrieval practise | Re-reading notes as revision strategy | Regular low-stakes quizzing and recall activities |

| Spacing beats cramming | Teaching topics once and moving on | Regular revisiting and interleaved practise |

| Feedback acted upon | Detailed comments students never use | Structured response time built into lessons |

| Motivation follows success | Reducing challenge to boost engagement | High expectations with effective scaffolding |

The most effective teachers share common practices grounded in cognitive science rather than relying on intuition alone. These fundamental principles provide a reliable framework for making instructional decisions that genuinely support student learning.

The principle of cognitive load management recognises that working memory has strict limits. When teachers break complex tasks into smaller steps and provide worked examples before independent practise, students learn more efficiently. For instance, when teaching essay writing, showing studentsan annotated model paragraph before asking them to write their own reduces cognitive overload and improves outcomes.

Another cornerstone is the testing effect, which demonstrates that retrieval practise strengthens memory far more than re-reading notes. Teachers can harness this by starting lessons with low-stakes quizzes on previous content, using mini-whiteboards for quick recall activities, or implementing regular knowledge checks through questioning. Research by Roediger and Karpicke shows that students who practise retrieval retain 50% more information after a week compared to those who simply review material.

Spaced practise complements retrieval by distributing learning over time. Rather than teaching fractions intensively for two weeks then moving on, maths teachers might introduce the concept, return to it weekly with increasing complexity, and integrate fraction problems into other topics throughout the year. This approach, supported by Ebbinghaus's forgetting curve research, leads to more durable learning.

These principles work because they align with how human memory actually functions, not how we might assume it works. By understanding and applying these evidence-based strategies, teachers can make informed decisions that maximise learning for all students, regardless of subject or year group.

Cognitive load theory, developed by John Sweller, reveals that working memory can only process a limited amount of information at once. When students' working memory becomes overloaded, learning stops. Understanding how to manage cognitive load transforms lesson planning from guesswork into deliberate design.

Three types of cognitive load affect learning: intrinsic load (the natural difficulty of the material), extraneous load (unnecessary mental effort from poor instruction), and germane load (productive thinking that builds understanding). Effective teachers reduce extraneous load whilst maximising germane load, allowing students to focus their mental resources on what matters.

Practical strategies for managing cognitive load include breaking complex tasks into smaller steps. When teaching long division, for instance, explicitly teach each step separately before combining them. This segmenting prevents overwhelm and builds confidence. Similarly, when introducing Shakespeare to Year 9 students, provide modern English translations alongside the original text initially, reducing the cognitive demands of unfamiliar language whilst students grasp plot and character.

Another powerful approach involves using worked examples before independent practise. Rather than asking students to solve quadratic equations immediately, show step-by-step solutions first, gradually removing scaffolding as expertise develops. This 'fading' process, supported by extensive research, prevents cognitive overload whilst building competence.

Visual aids and dual coding also reduce cognitive load. Combining diagrams with verbal explanations when teaching the water cycle, or using graphic organisers for essay planning, helps students process information through multiple channels without overwhelming working memory. These strategies aren't just helpful additions; they're essential tools for making complex content accessible to all learners.

The science of memory reveals a counterintuitive truth: forgetting is essential to learning. When students actively retrieve information from memory, rather than simply re-reading notes, they strengthen neural pathways and create durable understanding. This principle, combined with strategic spacing of practise sessions, forms the foundation of effective long-term learning.

Retrieval practise works because it mirrors how we use knowledge in real situations. When a student recalls a historical date, solves a maths problem from memory, or explains a scientific concept without notes, they're doing more than demonstrating knowledge; they're strengthening it. Research by Roediger and Karpicke shows that students who practise retrieval outperform those who repeatedly study material by margins of 50% or more on delayed tests.

Practical strategies for implementing retrieval practise include starting lessons with brief quizzes on previous content, using exit tickets that require students key ideas without resources, and incorporating regular low-stakes testing. For instance, a Year 9 science teacher might begin each lesson with three questions about last week's topic, requiring written answers without textbooks. A primary teacher could use "brain dumps" where pupils write everything they remember about a topic before starting new content.

Spaced learning complements retrieval by distributing practise over time. Rather than massing practise in single sessions, teachers should revisit key concepts at increasing intervals. A practical approach involves the "1-3-7 rule": review new material after one day, then three days, then weekly. This spacing effect, first documented by Hermann Ebbinghaus, can double retention rates compared to massed practise, making it one of the most reliable findings in educational psychology.

The core principles about memory, cognitive load, and effective practise apply across subjects. However, the specific application will vary. Subjects with extensive knowledge bases (history, science) may emphasise knowledge building more heavily, while subjects with procedural skills (mathematics, languages) may emphasise deliberate practise. The principles inform rather than dictate specific approaches.

Far from opposing creativity, these principles support it. Creativity requires combining existing knowledge in new ways, so building knowledge enables rather than limits creativity. Higher-order thinking depends on having relevant information readily available in long-term memory rather than consuming working memory. Explicit instruction on creative techniques can also be effective.

The curriculum often demands covering extensive content. Prioritisation is essential: identify the most important concepts and ensure these are taught thoroughly with adequate practise, while less critical content receives lighter treatment. Spiralling back to core concepts throughout the year supports both coverage and depth.

Start by implementing evidence-informed practices in your own classroom. Collect data on their effectiveness. Share successes informally with interested colleagues. When appropriate, raise questions about the evidence base for school initiatives. Change often happens gradually through demonstration rather than confrontation.

These peer-reviewed studies provide the research foundation for the strategies discussed in this article:

Getting Explicit Instruction Right View study ↗

Richard Holden & Fabio I. Martinenghi (2025)

This groundbreaking study provides concrete evidence for the effectiveness of properly implemented explicit instruction on student test performance, addressing the ongoing debate between inquiry-based learning and direct teaching methods. The research offers teachers practical guidance on how to correctly implement explicit instruction techniques, moving beyond theoretical arguments to show measurable improvements in student outcomes. For educators seeking evidence-based teaching strategies, this paper provides the scientific backing needed to confidently use direct instruction methods in their classrooms.

The impact of teaching games for understanding and direct instruction models on volleyball passing skills based on arm strength View study ↗

2 citations

Zaniar Dwi Prihatin Ciptadi et al. (2025)

This study reveals how different teaching approaches work better for students with varying physical abilities, specifically comparing tactical game understanding versus direct skill instruction in volleyball. The research demonstrates that matching teaching methods to individual student characteristics, such as arm strength, can significantly improve learning outcomes. Physical education teachers and coaches will find valuable insights on how to tailor their instruction to maximise each student's potential based on their unique abilities.

Teaching verb spelling through explicit direct instruction View study ↗

3 citations

Robert J. P. M. Chamalaun et al. (2022)

This research proves that interactive explicit direct instruction dramatically improves students' ability to spell challenging verb forms that sound alike but are spelled differently. The study shows that when teachers provide clear, step-by-step guidance on grammatical functions rather than leaving students to figure it out themselves, spelling accuracy increases significantly. Language arts teachers will discover practical techniques for making grammar instruction more engaging and effective, particularly for those tricky spelling rules that students typically struggle to master.

Retrieval Practise "in the Wild": Teachers' Reported Use of Retrieval Practise in the Classroom View study ↗

1 citations

Gareth Bates & James Shea (2024)

This comprehensive survey reveals how teachers are actually using retrieval practise techniques in real classrooms, bridging the gap between research recommendations and everyday teaching reality. The study uncovers both the successes and challenges teachers face when implementing memory-strengthening activities like quizzing and recall exercises in their daily instruction. Teachers will gain valuable insights into how their colleagues are practically applying retrieval practise strategies and learn from both effective implementations and common pitfalls to avoid.

A metacognitive retrieval practise intervention to improve undergraduates' monitoring and control processes and use of performance feedback for classroom learning. View study ↗

26 citations

MeganClaire Cogliano et al. (2020)

This intervention study demonstrates how combining retrieval practise with metacognitive training helps students become better at monitoring their own learning and using feedback effectively. The research shows that when students learn to think about their thinking while practising recall, they develop stronger self-regulation skills and make better use of teacher feedback. Educators at all levels will find practical strategies for helping students become more independent learners who can accurately assess their own understanding and take meaningful action to improve.

Effective teaching is based on evidence from cognitive scienceand educational psychology, not mysterious talent or instinct. The core principles include focusing on student thinking, building strong knowledge foundations, using explicit instruction, and implementing deliberate practise with feedback. These research-backed strategies work consistently across different subjects and age groups.

Effective teaching is not mysterious or dependent on innate talent. Decades of research in cognitive science, educational psychology, and classroom studies have identified principles that consistently support learning across subjects and age groups. These principles often contradict popular assumptions but provide a reliable foundation for instructional decisions.

Alex Quigley, a former English teacher and Director of Huntington Research School, distilled key insights from educational research into accessible principles that every teacher can apply. His work, along with contributions from researchers like Barak Rosenshine, John Sweller, and Robert Bjork, provides a framework for thinking about teaching strategiesthat cuts through educational fads.

Students remember what they actively think about during lessons, not necessarily what teachers intend them to learn. If students spend time thinking about irrelevant details like decorating a poster rather than the content, they will remember the decoration process instead. Teachers must design activities that direct student thinking towards the key learning objectives.

Daniel Willingham's observation that "memory is the residue of thought" has profound implications for teaching. Students remember what they think about during a lesson, not what the teacher intended them to think about. If students spend a lesson thinking about how to decorate a poster rather than the historical concepts it represents, they will remember poster design, not history.

This principle suggests teachers should constantly ask: "What will students actually be thinking about during this activity?" Activities that are engaging but cognitively unfocused, such as elaborate games or competitive elements, may be remembered for the wrong reasons. The most effective activities are those where thinking about the content is unavoidable.

Critical thinking, problem-solving, and creativity all depend on having rich background knowledge in the subject area. Students cannot think critically about topics they know little about because thinking skills are not separate from content knowledge. Building strong knowledge foundations enables students to analyse, evaluate, and create effectively.

A persistent myth suggests that teaching knowledge is outdated because students can "just look things up." Research consistently contradicts this. Working memory, where conscious thinking occurs, can only hold a limited amount of information. Background knowledge stored in long-term memory frees up working memory for higher-order thinking.

Expert chess players can remember board positions that beginners cannot because they recognise patterns rather than individual pieces. Similarly, students with rich vocabulary can focus on comprehension rather than decoding. Teaching knowledge is not opposed to teaching thinking, it is the precondition for it.

Research consistently shows that clear explanations, worked examples, and guided practise lead to better learning outcomes than discovery-based approaches for most objectives. Explicit instruction reduces cognitive load and provides students with accurate mental models before they practise independently. This structured approach helps students learn more efficiently and avoid developing misconceptions.

Barak Rosenshine's Principles of Instruction synthesise decades of research on effective teaching. The findings consistently favour explicit instruction: clear explanations, worked examples, guided practise with feedback, and independent practise. This is especially true for novice learners who lack the background knowledge to benefit from discovery approaches.

This does not mean lecturing without student involvement. Effective explicit instruction involves constant checking for understanding, high-frequency questioning, and scaffolded practise. The goal is to reduce cognitive load by providing clear guidance rather than expecting students to discover insights independently.

Teachers can manage cognitive load by breaking complex tasks into smaller steps and presenting information in chunks that match students' processing capacity. Remove unnecessary distractions from learning materials and use worked examples to demonstrate procedures before asking students to solve problems independently. Gradually increase complexity as students develop expertise.

John Sweller's Cognitive Load Theory explains why some lessons overwhelm students while others enable learning. Working memory is limited, and presenting too much new information simultaneously causes cognitive overload. Effective teaching sequences information carefully, builds on prior knowledge, and uses techniques like worked examples and dual coding(words plus images) to reduce unnecessary load.

Split attention, where students must mentally integrate information from multiple sources, increases load. Placing labels directly on diagrams rather than in separate legends, and synchronising speech with visuals, reduces this burden. These seemingly small design decisions significantly impact learning.

Retrieval practise strengthens memory by requiring students to actively recall information rather than passively reviewing it. Regular quizzing, self-testing, and practise problems force the brain to reconstruct knowledge, making it more durable and accessible. This active retrieval is more effective than re-reading or highlighting for long-term retention.

Testing is not just for assessment, it is one of the most powerful learning strategies available. The act of retrieving information from memory strengthens the memory trace more effectively than re-reading or re-studying. This "testing effect" has been replicated across hundreds of studies.

Low-stakes quizzing at the start of lessons, flashcard practise, and asking students to write everything they remember about a topic before reviewing notes all harness retrieval practise. The effort involved in retrieval, even when partially unsuccessful, is precisely what makes it effective.

Spaced practise distributes learning over time rather than concentrating it in single sessions, leading to better long-term retention. The forgetting that occurs between practise sessions actually strengthens memory when information is successfully retrieved again. Teachers should revisit important concepts multiple times across weeks and months rather than covering them intensively once.

Distributed practise, where study sessions are spaced over time, produces better long-term retention than massed practise, where the same total time is spent in one session. This spacing effect is one of the most strong findings in learning science, yet school schedules often work against it.

Teachers can build spacing into their practise by regularly revisiting previous topics, interleaving practise of different skills, and designing cumulative assessments that require retrieval of material from earlier in the course. The forgetting that occurs between sessions is not a bug but a feature, the effort of re-learning is what builds durable memory.

Effective feedback must be specific, timely, and include opportunities for students to act on it immediately. Simply marking errors without giving students time to correct them wastes the learning potential of feedback. Teachers should build in dedicated time for students to respond to feedback and improve their work based on the guidance provided.

Feedback is only effective when students use it to improve. Detailed written comments that students glance at before filing away have limited impact. Effective feedback systems build in structured time for students to respond to feedback, revise their work, or demonstrate improvement.

The timing and focus of feedback also matter. Immediate feedback on practise activities helps students correct errors before they become ingrained. Feedback should focus on the task and how to improve rather than on the learner's personal qualities.

Student motivation typically follows from experiencing success rather than preceding it, contrary to popular belief. When students master skills and understand content, they become more motivated to continue learning in that area. Teachers should structure lessons to ensure all students experience regular success through appropriate challenge levels and scaffolding.

A common assumption is that learning should be made fun to motivate students. Research suggests the relationship often works the other way: students become motivated when they experience success and develop competence. Reducing challenge in pursuit of engagement may actually undermine motivation.

This suggests prioritising high expectations, effective instruction, and the satisfaction of genuine achievement over entertainment value. When students understand material, can answer questions correctly, and see themselves improving, motivation follows naturally.

Reading comprehension underlies success in every academic subject because it enables students to independently access knowledge and continue learning. Strong readers can learn from textbooks, online resources, and other materials without constant teacher support. Developing reading skills, including vocabulary and background knowledge, should be a priority across all subject areas.

Reading underpins success across all subjects. Students who read widely develop larger vocabularies, more background knowledge, and greater reading fluency, creating a virtuous cycle. Those who struggle to read fall further behind as the reading demands of the curriculum increase.

This makes systematic phonics instruction in early years, explicit vocabulary teaching throughout school, and substantial reading practise essential priorities. Teachers across all subjects can support reading development by teaching subject-specific vocabulary and using reading strategies like reciprocal reading.

Effective teachers continuously update their practise based on research evidence and reflection on student outcomes. Professional development should focus on understanding the science of learning and translating research into classroom applications. Teachers benefit from collaborating with colleagues to test and refine evidence-based strategies in their specific contexts.

Effective teaching is complex, and no initial training can fully prepare teachers for every situation they will encounter. The best teachers maintain a stance of inquiry, engaging with research, reflecting on their practise, and seeking feedback from colleagues and students.

Professional learning communities, lesson study, and engagement with educational research all support ongoing development. The principles outlined here are not fixed prescriptions but starting points for thoughtful professional judgement.

Start by selecting one or two principles that address current classroom challenges and implement them systematically. Monitor student learningoutcomes to assess effectiveness and adjust implementation based on results. Gradually incorporate additional principles while maintaining successful practices, building a coherent approach grounded in learning science.

| Principle | Common Pitfall | Evidence-Informed Alternative |

|---|---|---|

| Memory is residue of thought | Engaging activities that distract from content | Activities where thinking about content is unavoidable |

| Knowledge enables thinking | Teaching "skills" without building knowledge | Systematic knowledge building before complex tasks |

| Explicit instruction works | Expecting students to discover key insights | Clear explanations with worked examples |

| Manage cognitive load | Presenting too much new information at once | Sequencing information and using dual coding |

| Retrieval practise | Re-reading notes as revision strategy | Regular low-stakes quizzing and recall activities |

| Spacing beats cramming | Teaching topics once and moving on | Regular revisiting and interleaved practise |

| Feedback acted upon | Detailed comments students never use | Structured response time built into lessons |

| Motivation follows success | Reducing challenge to boost engagement | High expectations with effective scaffolding |

The most effective teachers share common practices grounded in cognitive science rather than relying on intuition alone. These fundamental principles provide a reliable framework for making instructional decisions that genuinely support student learning.

The principle of cognitive load management recognises that working memory has strict limits. When teachers break complex tasks into smaller steps and provide worked examples before independent practise, students learn more efficiently. For instance, when teaching essay writing, showing studentsan annotated model paragraph before asking them to write their own reduces cognitive overload and improves outcomes.

Another cornerstone is the testing effect, which demonstrates that retrieval practise strengthens memory far more than re-reading notes. Teachers can harness this by starting lessons with low-stakes quizzes on previous content, using mini-whiteboards for quick recall activities, or implementing regular knowledge checks through questioning. Research by Roediger and Karpicke shows that students who practise retrieval retain 50% more information after a week compared to those who simply review material.

Spaced practise complements retrieval by distributing learning over time. Rather than teaching fractions intensively for two weeks then moving on, maths teachers might introduce the concept, return to it weekly with increasing complexity, and integrate fraction problems into other topics throughout the year. This approach, supported by Ebbinghaus's forgetting curve research, leads to more durable learning.

These principles work because they align with how human memory actually functions, not how we might assume it works. By understanding and applying these evidence-based strategies, teachers can make informed decisions that maximise learning for all students, regardless of subject or year group.

Cognitive load theory, developed by John Sweller, reveals that working memory can only process a limited amount of information at once. When students' working memory becomes overloaded, learning stops. Understanding how to manage cognitive load transforms lesson planning from guesswork into deliberate design.

Three types of cognitive load affect learning: intrinsic load (the natural difficulty of the material), extraneous load (unnecessary mental effort from poor instruction), and germane load (productive thinking that builds understanding). Effective teachers reduce extraneous load whilst maximising germane load, allowing students to focus their mental resources on what matters.

Practical strategies for managing cognitive load include breaking complex tasks into smaller steps. When teaching long division, for instance, explicitly teach each step separately before combining them. This segmenting prevents overwhelm and builds confidence. Similarly, when introducing Shakespeare to Year 9 students, provide modern English translations alongside the original text initially, reducing the cognitive demands of unfamiliar language whilst students grasp plot and character.

Another powerful approach involves using worked examples before independent practise. Rather than asking students to solve quadratic equations immediately, show step-by-step solutions first, gradually removing scaffolding as expertise develops. This 'fading' process, supported by extensive research, prevents cognitive overload whilst building competence.

Visual aids and dual coding also reduce cognitive load. Combining diagrams with verbal explanations when teaching the water cycle, or using graphic organisers for essay planning, helps students process information through multiple channels without overwhelming working memory. These strategies aren't just helpful additions; they're essential tools for making complex content accessible to all learners.

The science of memory reveals a counterintuitive truth: forgetting is essential to learning. When students actively retrieve information from memory, rather than simply re-reading notes, they strengthen neural pathways and create durable understanding. This principle, combined with strategic spacing of practise sessions, forms the foundation of effective long-term learning.

Retrieval practise works because it mirrors how we use knowledge in real situations. When a student recalls a historical date, solves a maths problem from memory, or explains a scientific concept without notes, they're doing more than demonstrating knowledge; they're strengthening it. Research by Roediger and Karpicke shows that students who practise retrieval outperform those who repeatedly study material by margins of 50% or more on delayed tests.

Practical strategies for implementing retrieval practise include starting lessons with brief quizzes on previous content, using exit tickets that require students key ideas without resources, and incorporating regular low-stakes testing. For instance, a Year 9 science teacher might begin each lesson with three questions about last week's topic, requiring written answers without textbooks. A primary teacher could use "brain dumps" where pupils write everything they remember about a topic before starting new content.

Spaced learning complements retrieval by distributing practise over time. Rather than massing practise in single sessions, teachers should revisit key concepts at increasing intervals. A practical approach involves the "1-3-7 rule": review new material after one day, then three days, then weekly. This spacing effect, first documented by Hermann Ebbinghaus, can double retention rates compared to massed practise, making it one of the most reliable findings in educational psychology.

The core principles about memory, cognitive load, and effective practise apply across subjects. However, the specific application will vary. Subjects with extensive knowledge bases (history, science) may emphasise knowledge building more heavily, while subjects with procedural skills (mathematics, languages) may emphasise deliberate practise. The principles inform rather than dictate specific approaches.

Far from opposing creativity, these principles support it. Creativity requires combining existing knowledge in new ways, so building knowledge enables rather than limits creativity. Higher-order thinking depends on having relevant information readily available in long-term memory rather than consuming working memory. Explicit instruction on creative techniques can also be effective.

The curriculum often demands covering extensive content. Prioritisation is essential: identify the most important concepts and ensure these are taught thoroughly with adequate practise, while less critical content receives lighter treatment. Spiralling back to core concepts throughout the year supports both coverage and depth.

Start by implementing evidence-informed practices in your own classroom. Collect data on their effectiveness. Share successes informally with interested colleagues. When appropriate, raise questions about the evidence base for school initiatives. Change often happens gradually through demonstration rather than confrontation.

These peer-reviewed studies provide the research foundation for the strategies discussed in this article:

Getting Explicit Instruction Right View study ↗

Richard Holden & Fabio I. Martinenghi (2025)

This groundbreaking study provides concrete evidence for the effectiveness of properly implemented explicit instruction on student test performance, addressing the ongoing debate between inquiry-based learning and direct teaching methods. The research offers teachers practical guidance on how to correctly implement explicit instruction techniques, moving beyond theoretical arguments to show measurable improvements in student outcomes. For educators seeking evidence-based teaching strategies, this paper provides the scientific backing needed to confidently use direct instruction methods in their classrooms.

The impact of teaching games for understanding and direct instruction models on volleyball passing skills based on arm strength View study ↗

2 citations

Zaniar Dwi Prihatin Ciptadi et al. (2025)

This study reveals how different teaching approaches work better for students with varying physical abilities, specifically comparing tactical game understanding versus direct skill instruction in volleyball. The research demonstrates that matching teaching methods to individual student characteristics, such as arm strength, can significantly improve learning outcomes. Physical education teachers and coaches will find valuable insights on how to tailor their instruction to maximise each student's potential based on their unique abilities.

Teaching verb spelling through explicit direct instruction View study ↗

3 citations

Robert J. P. M. Chamalaun et al. (2022)

This research proves that interactive explicit direct instruction dramatically improves students' ability to spell challenging verb forms that sound alike but are spelled differently. The study shows that when teachers provide clear, step-by-step guidance on grammatical functions rather than leaving students to figure it out themselves, spelling accuracy increases significantly. Language arts teachers will discover practical techniques for making grammar instruction more engaging and effective, particularly for those tricky spelling rules that students typically struggle to master.

Retrieval Practise "in the Wild": Teachers' Reported Use of Retrieval Practise in the Classroom View study ↗

1 citations

Gareth Bates & James Shea (2024)

This comprehensive survey reveals how teachers are actually using retrieval practise techniques in real classrooms, bridging the gap between research recommendations and everyday teaching reality. The study uncovers both the successes and challenges teachers face when implementing memory-strengthening activities like quizzing and recall exercises in their daily instruction. Teachers will gain valuable insights into how their colleagues are practically applying retrieval practise strategies and learn from both effective implementations and common pitfalls to avoid.

A metacognitive retrieval practise intervention to improve undergraduates' monitoring and control processes and use of performance feedback for classroom learning. View study ↗

26 citations

MeganClaire Cogliano et al. (2020)

This intervention study demonstrates how combining retrieval practise with metacognitive training helps students become better at monitoring their own learning and using feedback effectively. The research shows that when students learn to think about their thinking while practising recall, they develop stronger self-regulation skills and make better use of teacher feedback. Educators at all levels will find practical strategies for helping students become more independent learners who can accurately assess their own understanding and take meaningful action to improve.

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/teaching-and-learning-wisdom#article","headline":"Teaching Wisdom: Timeless Principles for Effective Education","description":"Explore enduring principles of effective teaching that transcend trends. Discover wisdom from experienced educators about what really matters in the...","datePublished":"2022-03-07T12:34:34.290Z","dateModified":"2026-01-26T10:09:32.212Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/teaching-and-learning-wisdom"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/6942a4c248a8ef4b8c60a241_6225fb662f6a5945cfd87431_Alex%2520Quigleys%252010%2520things.png","wordCount":3410},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/teaching-and-learning-wisdom#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"Teaching Wisdom: Timeless Principles for Effective Education","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/teaching-and-learning-wisdom"}]},{"@type":"FAQPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/teaching-and-learning-wisdom#faq","mainEntity":[{"@type":"Question","name":"Do these principles apply to all subjects?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"The core principles about memory, cognitive load, and effective practise apply across subjects. However, the specific application will vary. Subjects with extensive knowledge bases (history, science) may emphasise knowledge building more heavily, while subjects with procedural skills (mathematics, l"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What about creativity and higher-order thinking?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Far from opposing creativity, these principles support it. Creativity requires combining existing knowledge in new ways, so building knowledge enables rather than limits creativity. Higher-order thinking depends on having relevant information readily available in long-term memory rather than consumi"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"How do I balance coverage with depth?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"The curriculum often demands covering extensive content. Prioritisation is essential: identify the most important concepts and ensure these are taught thoroughly with adequate practise, while less critical content receives lighter treatment. Spiralling back to core concepts throughout the year suppo"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What if my school promotes approaches that contradict this research?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Start by implementing evidence-informed practices in your own classroom. Collect data on their effectiveness. Share successes informally with interested colleagues. When appropriate, raise questions about the evidence base for school initiatives. Change often happens gradually through demonstration "}}]}]}