Context-Dependent Learning: A Teacher's Guide

Discover how context shapes memory and learning, with practical strategies to help students retrieve knowledge across different situations and exams.

Discover how context shapes memory and learning, with practical strategies to help students retrieve knowledge across different situations and exams.

Context-dependent learning is a powerful memory principle that can dramatically improve your students' exam performance by teaching them to recall information in varied environments. When students learn and practise material in different contexts, different rooms, seating arrangements, or conditions, they build stronger, more flexible memory pathways that work even under exam pressure. This technique explains why some students excel in classroom discussions but struggle during tests: they've only strengthened their memory in one specific context. By strategically varying the learning environment, you can help students access their knowledge anywhere, anytime. Here's how to harness this principle to transform your teaching and boost your students' results.

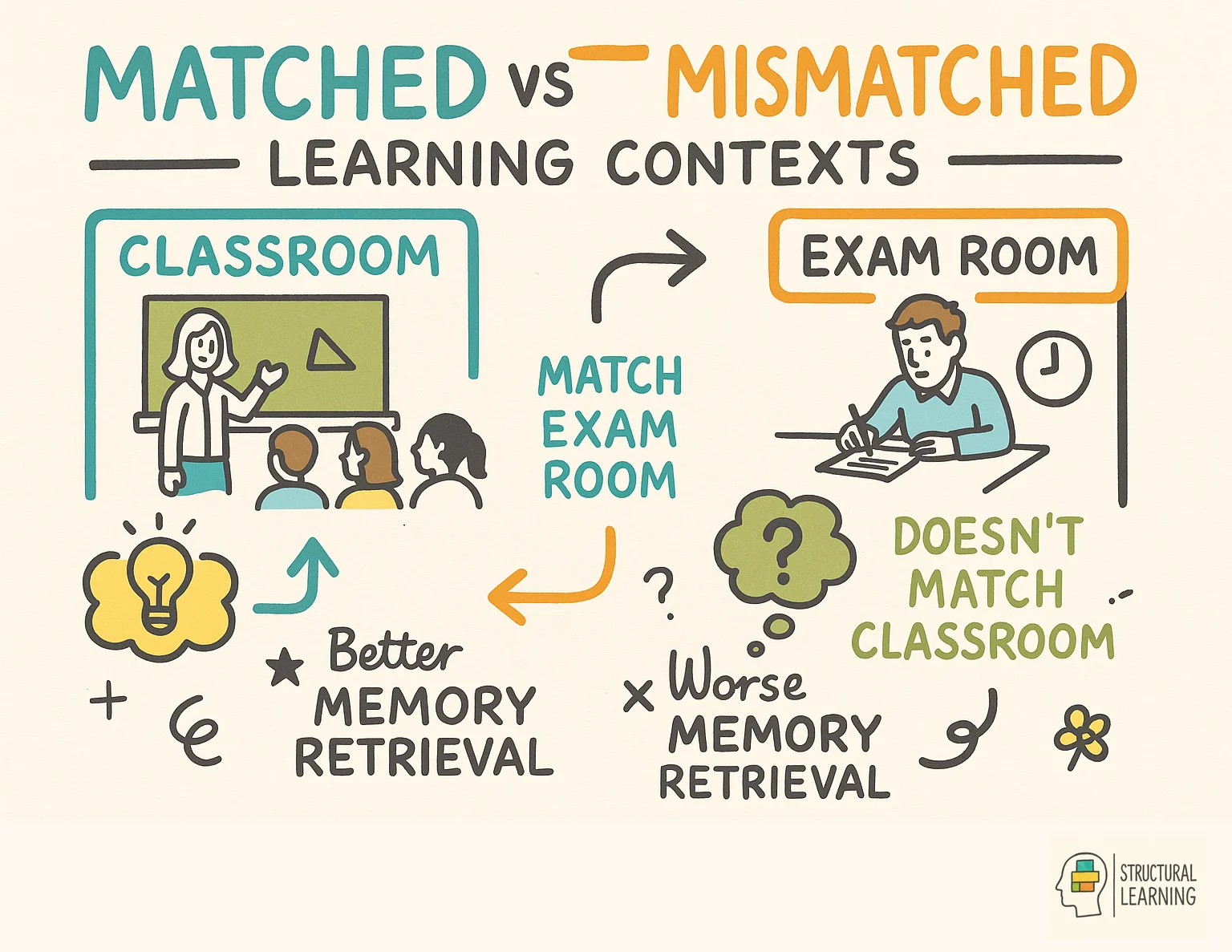

This frustrating phenomenon has a scientific explanation. Context-dependent learning describes how the context in which we learn becomes linked to what we learn. When retrieval context matches learning context, memory works well. When contexts differ, retrieval becomes harder, even though the information is still there.

Understanding context-dependent learning helps teachers prepare students for the reality that exams, assessments, and real-world applications rarely occur in the exact conditions where learning happened. This insight should inform how we design learning objectivesand plan lessons. By deliberately varying learning contexts and teaching students about how context affects memory, we can build more transferable knowledge through effective supporting student learning strategies.

Context-dependent learning means students remember information better when the retrieval environment matches where they learned it. The physical location, sounds, and even smells during learning become retrieval cues that help access memories. Teachers can improve student performance by varying practise contexts and explicitly teaching about these memory effects.

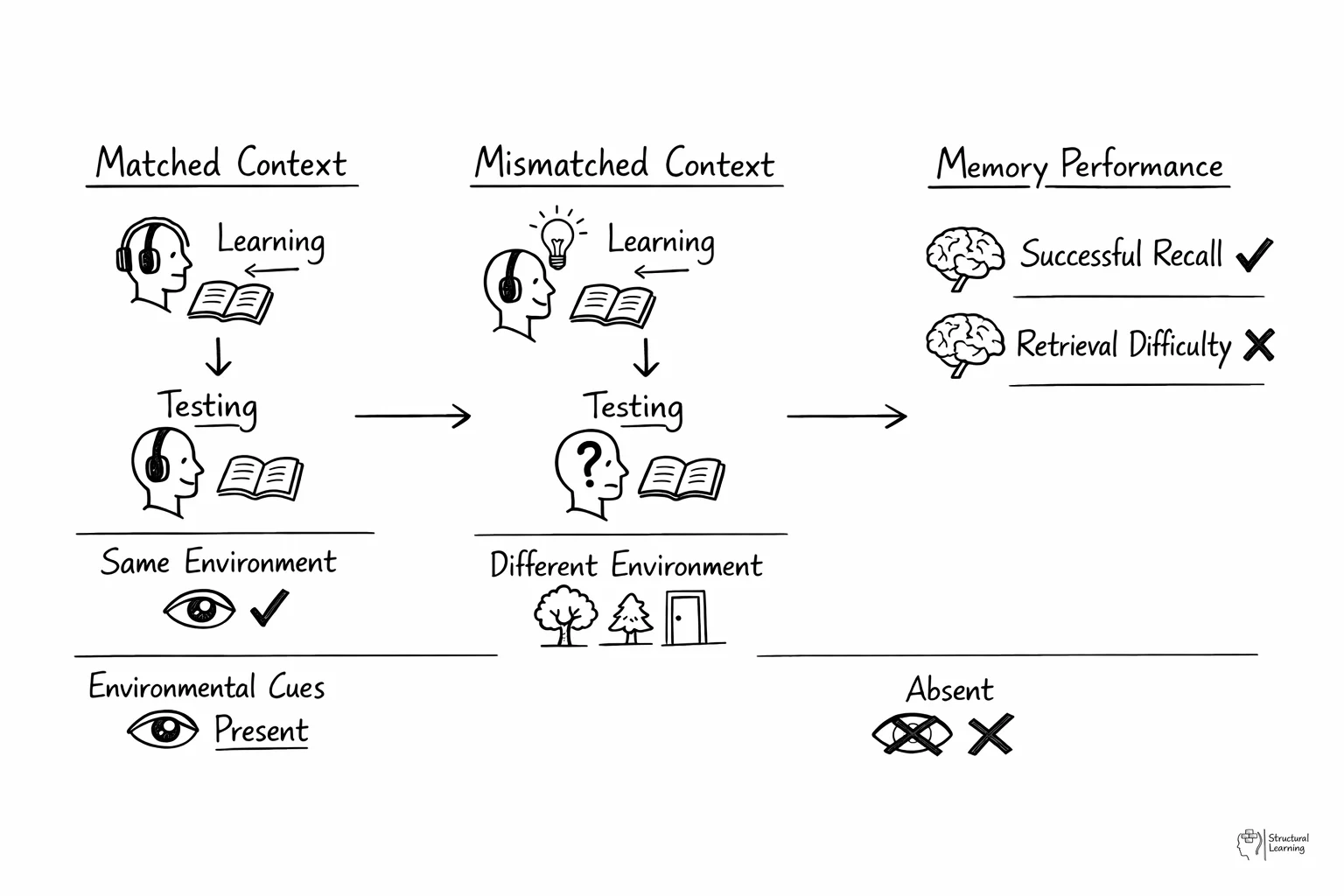

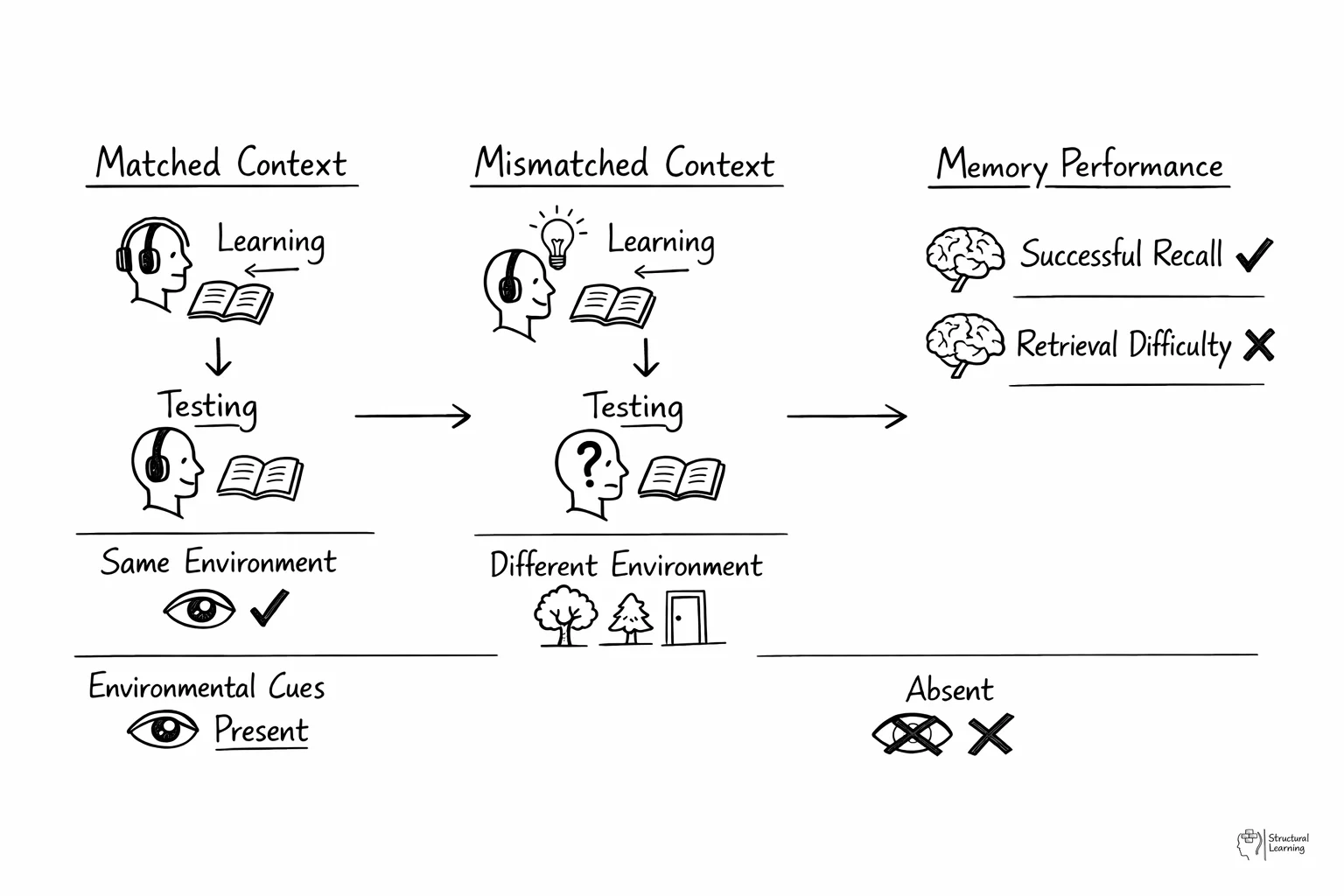

Context-dependent memory refers to the improved ability to retrieve information when the external environment at retrieval matches the environment at encoding. The sights, sounds, smells, and physical circumstances present during learning become associated with the memory and can later serve as retrieval cues.

The classic demonstration comes from Godden and Baddeley's 1975 experiment with scuba divers. Divers learned word lists either underwater or on dry land, then were tested in either the same or different environment. Those tested in the same environment they learned in remembered about 50% more than those tested in a different environment.

Research Update: A 2021 replication study by Murre and colleagues, published in Royal Society Open Science, failed to reproduce the original Godden and Baddeley (1975) scuba diver findings under similar conditions. This suggests that while context-dependent memory effects are real, they may be smaller and more variable than the classic study indicated. The Smith and Vela (2001) meta-analysis provides more strong support for the general phenomenon. Mental reinstatement strategies remain valuable for students who cannot physically return to learning contexts.

This finding has been replicated across many contexts. This finding has been replicated across many contexts, from oracy skillsdevelopment to academic subjects. Students who learn in one classroom and are tested in another often perform worse than those tested where they learned. Even subtle environmental changes can affect retrieval.

Context dependence reflects a fundamental feature of how memory works. Memories aren't stored as isolated files but as patterns of neural activation that include contextual elements. When you encounter the same context again, those contextual cues help reactivate the complete memory pattern.

The brain encodes environmental details alongside the actual information being learned, creating multiple retrieval pathways. When students encounter similar environmental cues later, these activate the associated memories through a process called cue-dependent retrieval. This happens automatically and explains why students often perform better in their regular classroom than in unfamiliar exam halls.

Understanding why context matters helps teachers design instruction that builds transferable knowledge.

Endel Tulving's encoding specificity principle states that retrieval cues are effective only to the extent that they were encoded along with the target information. Information is always learned in a context, and that context becomes part of what's encoded.

When you learn something in a particular room, aspects of that room become associated with the memory. The colour of the walls, the arrangement of desks, the ambient sounds all get encoded alongside the academic content. These contextual elements then serve as retrieval cues.

Retrieval works by pattern matching. When you encounter cues similar to what was encoded, the complete memory pattern becomes activated. Contextual cues help discriminate between similar memories, directing retrieval towards information learned in this specific setting.

In a familiar classroom, the visual environment activates memories of previous learning in that space. This contextual priming makes related academic content more accessible. In an unfamiliar exam hall, these cues are absent.

Mental reinstatement can partly substitute for physical context reinstatement. If students mentally imagine the original learning context, they can sometimes access context-dependent memories even when physically in a different environment.

This has practical implications. Teaching students to visualise where they learned information, what was happening, and how they felt can support retrieval in novel contexts.

State-dependent memory means students recall information better when their internal state (mood, energy level, or physical condition) matches their state during learning. A calm student who learned material while relaxed may struggle to recall it when anxious during a test. Teachers can help by teaching relaxation techniques and ensuring students practise under various emotional conditions.

Closely related to context-dependent memory is state-dependent memory, where internal states at encoding and retrieval affect memory accessibility.

Memories encoded in a particular mood are more accessible when that mood recurs. Happy memories are more easily retrieved when happy; sad memories when sad. This creates self-reinforcing patterns that can contribute to depression or anxiety.

For teachers, this suggests that creating positive emotional states during learning may support retrieval in similar positive states. However, since exams often produce anxiety, learning in consistently positive states might create a mismatch.

Studies have shown that memory is better when the pharmacological state at retrieval matches encoding. Students who drink coffee while studying retrieve better when caffeinated during testing than when uncaffeinated, for example.

This isn't an argument for constant caffeine consumption, but it illustrates how internal states, like external contexts, become associated with memories.

Physical states also matter. Learning while hungry versus satiated, tired versus alert, or active versus sedentary can create state-dependent memory effects. This adds complexity to the relationship between context and retrieval.

Context-dependent learning suggests teachers should vary where and how students practise important concepts rather than always using the same classroom setup. Students need exposure to different contexts during learning to build flexible knowledge that transfers to new situations. This includes changing seating arrangements, using different rooms, and practising skills in conditions similar to AI-powered assessment environments.

Context dependence has several practical implications for teaching and learning.

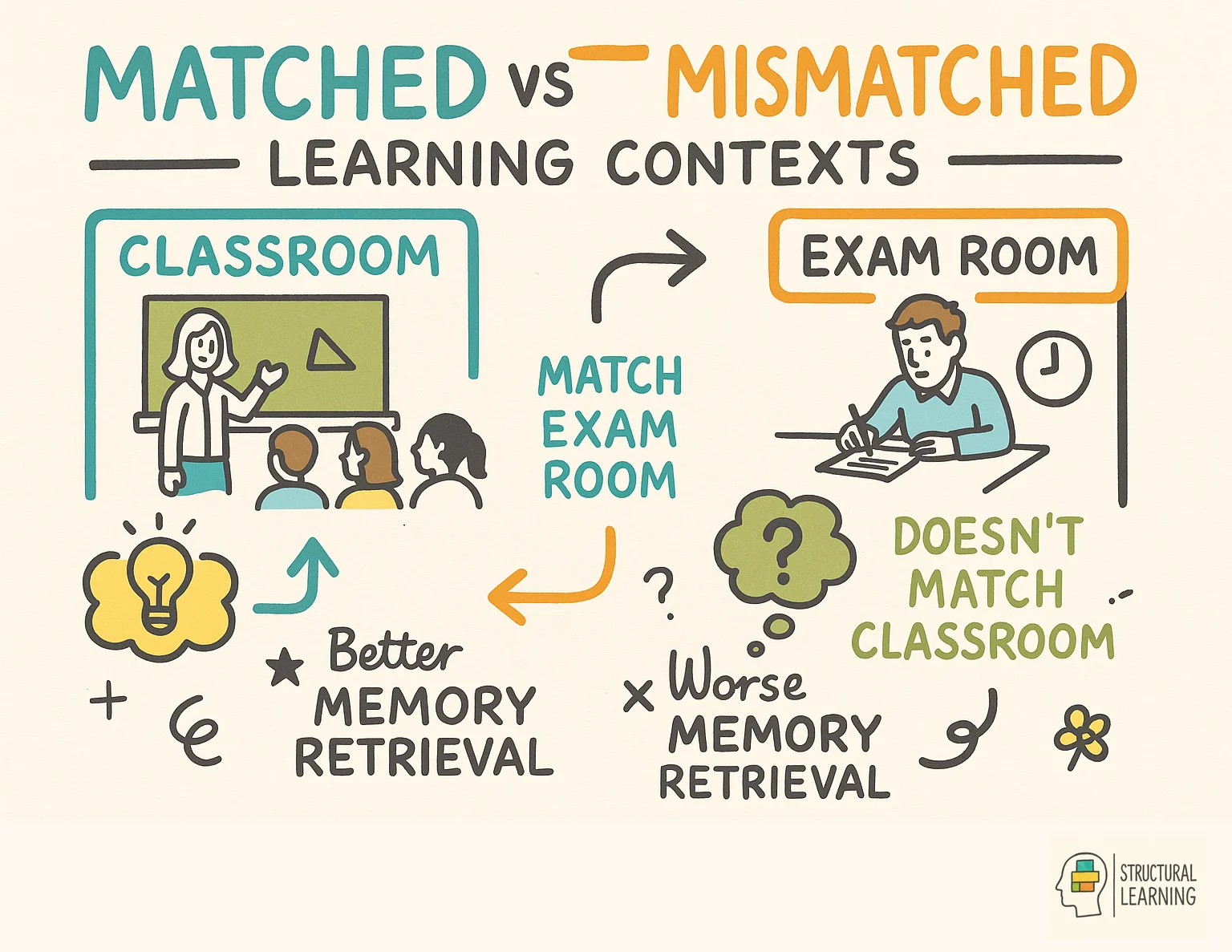

Students typically learn in familiar classrooms but take high-stakes exams in unfamiliar halls. This context mismatch can impair retrieval, adding to exam anxiety a genuine cognitive disadvantage.

Schools can address this by:

If learning is too tied to a single context, knowledge becomes inflexible. Students may know something perfectly in the classroom where they learned it but struggle to apply the same knowledge elsewhere.

The solution is varied practise: learning and retrieving in multiple contexts. When information is encoded across different environments, it becomes associated with multiple contextual cues, making it accessible from more retrieval situations.

This principle explains why learning only in the classroom can produce poor transfer to real-world applications. Varied learning contexts produce more flexible, applicable knowledge.

Homework provides learning opportunities outside the classroom context. This variation can actually strengthen memory by creating additional contextual associations.

Students who only study in one location might consider deliberately varying their study environments. The short-term inconvenience may pay off in more flexible retrieval.

Teachers can use interleaving practise across different classroom spaces and vary the physical setup during learning activities. Having students teach concepts to peers in different locations builds context-independent understanding. Regular practise tests in the actual exam room also helps students adapt to that specific environment before high-stakes assessments.

Several strategies help students build context-independent knowledge.

When possible, vary where learning and practise occur. Conduct some revision in different classrooms, outside spaces, or even corridors. The variety produces memories associated with multiple contexts.

This is especially important for content that students will need to retrieve in novel situations, such as exam halls or real-world applications.

Varying how content is presented creates different encoding contexts even within the same physical space. The same content encountered through reading, discussion, diagram analysis, and hands-on activity builds multiple memory traces with different contextual associations.

Dual coding, presenting information both verbally and visually, creates multiple encoding routes tha t don't all depend on the same contextual cues.

Practising the same type of problem repeatedly in the same format creates context-dependent procedural knowledge. Varying problem formats, wordings, and presentation styles builds more flexible skills.

Interleaving different problem types naturally varies context, as does mixing old and new content in practise sessions.

If exams will occur in unfamiliar environments, practise retrieval in varied and unfamiliar settings. This builds tolerance for context change and creates memories associated with multiple contextual cues.

Retrieval practise conducted only in the regular classroom produces retrieval skills tuned to that context. Retrieval practised across contexts produces more strong skills.

Students can partly compensate for context mismatch by mentally reinstating the learning context. Before attempting retrieval, they visualise where they learned the material, what was happening, and how they felt.

This technique doesn't fully eliminate context effects, but it can help bridge the gap between learning and testing environments. Students facing exams in unfamiliar halls might benefit from spending a moment visualising their classroom before beginning.

While external context is hard to control, internal cues can be made more consistent. Encouraging students to adopt consistent pre-study and pre-exam routines may create state-dependent bridges between learning and testing.

Taking a few deep breaths, reviewing key concepts briefly, or engaging in a consistent mental preparation routine could help align internal states across contexts.

Transfer improves when students practise applying knowledge in multiple contexts from the beginning rather than mastering it in one setting first. Teachers should explicitly connect new situations to previous learning and help students identify underlying principles that remain constant across contexts. Using real-world examples and field trips provides authentic contexts that enhance transfer.

Context dependence relates closely to transfer of learning: the application of knowledge and skills to new situations.

Transfer is difficult partly because learning contexts differ from application contexts. Knowledge encoded in a classroom context may not activate when needed in a workplace, home, or novel problem-solving situation.

The more learning is tied to specific contextual cues, the harder transfer becomes. This is why transfer of learning requires deliberate attention rather than occurring automatically.

To support transfer, learning should occur across varied contexts and with explicit attention to how knowledge applies beyond the immediate situation. Discuss when and where the learning would be useful. Practise applying knowledge to varied scenarios.

Abstract principles transfer better than context-specific procedures because they're encoded less tightly to particular circumstances. Teaching underlying principles alongside specific examples supports flexible application.

Knowledge intended for real-world use should be practised in contexts approximating real-world conditions. Learning only in idealised classroom conditions can produce knowledge that feels unavailable when actually needed.

This is why practical applications, field trips, simulations, and authentic tasks support transfer. They create learning associated with contexts similar to eventual use.

Subjects requiring rote memorization like vocabulary, historical dates, and scientific formulas show the strongest context effects. Mathematics and problem-solving subjects are moderately affected, while conceptual understanding in subjects like literature shows less context dependence. Physical skills in PE and arts subjects are highly context-sensitive and require practise in performance settings.

Context effects appear across all subject areas, though their strength varies.

Language learningshows strong context effects. Vocabulary learned in classroom drills may not come to mind in actual conversations. Phrases practised in one context may feel unavailable in another.

This argues for practising language in varied communicative contexts rather than only through repetitive drills. Role plays, conversations about varied topics, and language use outside formal lessons all build more flexible linguistic knowledge.

Mathematical procedures learned in textbook problem contexts may not transfer to word problems, real-world applications, or differently formatted questions. The surface features of how problems appear can create context dependence.

Varying problem formats and presentation styles during learning builds more flexible mathematical knowledge. Including problems with unfamiliar surface features helps break context dependence.

Scientific knowledge often fails to transfer from classroom contexts to everyday reasoning. Students may correctly answer school science questions while maintaining everyday misconceptions in out-of-school contexts.

Addressing this requires explicitly connecting school science to everyday phenomena and practising scientific reasoning in varied contexts beyond formal instruction.

Historical knowledge can become tied to the specific narratives and contexts in which it was taught. Students may struggle to recognise the same historical principles operating in unfamiliar periods or regions.

Comparing cases, drawing parallels across time periods, and practising historical reasoning with varied examples builds more transferable historical thinking.

Some researchers hypothesise that students with anxiety, ADHD, or autism spectrum conditions may show stronger context-dependent effects, as environmental changes could be more transformative to their cognitive processes. However, research in this area remains limited and findings are mixed. Younger students and those new to a subject also rely more heavily on contextual cues. Teachers can provide extra support by gradually introducing context variations and teaching explicit memory strategies.

Students vary in how strongly context affects their memory.

Students with higher working memorycapacity may be less susceptible to context dependence because they can more effectively use internal retrieval strategies that don't rely on external cues.

Students with working memory limitations might benefit more from context consistency or more intensive practise with mental reinstatement strategies.

Anxious students may show stronger context effects because anxiety consumes cognitive resources that could otherwise support flexible retrieval. High-stakes testing contexts that produce anxiety are particularly problematic.

Reducing exam anxiety through familiarisation, practise, and stress management may indirectly reduce context dependence effects for anxious students.

Students with strong prior knowledge can rely more on internal conceptual connections and less on external contextual cues. Their knowledge is better integrated into stable schemas that don't depend heavily on context for activation.

Building strong conceptual understanding, not just isolated facts, produces more context-independent knowledge.

Students should study in multiple locations and vary their study conditions, including noise levels and time of day. Creating mental contexts through visualision and self-testing in different environments builds stronger, more flexible memories. Teaching the material to others and using varied practise problems helps develop understanding that transcends specific contexts.

Students can use context research to improve their own learning and revision.

Rather than always studying in the same place, varying study locations produces memories associated with multiple contexts. This reduces dependence on any single environment for retrieval.

Practising under exam-like conditions creates memories associated with contexts similar to actual exams. Timed practise in quiet, unfamiliar settings may transfer better to exam halls than relaxed practise in comfortable home environments.

Before attempting recall, mentally return to where the learning occurred. Visualise the room, the page, the discussion. This partial reinstatement can improve retrieval even when physical context differs.

Students who understand context dependence can make better study decisions. Knowing that learning in only one context produces inflexible knowledge encourages deliberate variation.

Metacognitive awareness of how memory works supports better learning strategies.

Schools can redesign assessment practices to include familiar context elements or provide practise sessions in exam venues. Professional development should train teachers to vary instructional contexts and explicitly discuss memory strategies with students. Creating flexible learning spaces that can be reconfigured supports deliberate context variation in daily teaching.

Context-dependent learning reveals that memory is not just about what we learn but where and how we learn it. This has practical implications for instruction, revision, and assessment.

Teachers can support context-independent learning by:

Students can reduce context dependence by:

The goal isn't to eliminate context effects, which are deeply embedded in how memory works, but to build knowledge flexible enough to survive context changes.

Godden and Baddeley's 1975 underwater learning study provides the foundational evidence for environmental context effects. Smith and Vela's 2001 meta-analysis synthesizes decades of classroom-relevant research on context-dependent memory. Bjork and Bjork's work on desirable difficulties explains why varied practise contexts improve long-term retention despite making initial learning harder.

The following papers provide deeper exploration of context effects and their implications.

The classic underwater experiment demonstrating context-dependent memory. Scuba divers remembered word lists better when tested in the same environment where they learned, establishing context reinstatement as a powerful factor in retrieval.

Endel Tulving's foundational paper on encoding specificity, explaining how retrievalcues only work if they were encoded with the target information. This theoretical framework underpins understanding of context-dependent memory.

This study examines how context affects different aspects of memory, distinguishing between familiarity and recollection. The research helps explain when context effects are strongest and why.

Eric Eich's research on state-dependent memory demonstrates that internal states, like external contexts, become associated with memories. This extends context dependence beyond physical environments.

This comprehensive review synthesises research on context effects in memory, examining when effects are strongest and strategies for overcoming context dependence. The paper addresses educational implications directly.

���

Context-dependent memory is the brain's tendency to recall information more effectively when the retrieval environment matches the original learning environment. Put simply, students remember better when they're in the same place, mood, or situation where they first learnt the material. This phenomenon, first demonstrated by Godden and Baddeley's 1975 underwater study, shows that divers who learnt word lists underwater recalled them better underwater than on dry land, and vice versa.

The implications for teaching are profound. When students revise exclusively in their bedrooms, their memory becomes tied to that specific context; the familiar posters, desk arrangement, and even background sounds all become retrieval cues. Move them to an unfamiliar exam hall, and these contextual anchors vanish, making recall significantly harder. This explains why capable students sometimes underperform in tests despite knowing the material well.

Context extends beyond physical location. Internal states matter too: if students learn whilst relaxed and well-rested, they may struggle to access that knowledge when anxious during exams. Even seemingly trivial details like background music, room temperature, or the presence of classmates can become part of the memory trace.

As teachers, we can turn this principle to our advantage. Try teaching the same topic in different classrooms, or occasionally hold revision sessions in the sports hall where exams take place. Encourage students to vary their study locations at home, perhaps alternating between the kitchen table, library, and bedroom. When introducing crucial exam content, deliberately create neutral conditions that mirror test environments: silence, individual work, and timed practise. This builds what researchers call "context-independent" memories that remain accessible regardless of surroundings.

Context-dependent learning shows that students remember information best when their retrieval environment matches where they originally learnt it. This psychological principle, first documented by Godden and Baddeley in their underwater memory experiments, explains why pupils often struggle to recall classroom knowledge during exams in unfamiliar halls.

The core mechanism involves environmental cues becoming encoded alongside the actual learning material. When students study in their usual classroom, everything from the wall displays to the seating arrangement becomes part of their memory network. Remove these cues, and accessing the information becomes significantly harder, even though the knowledge remains intact.

For teachers, this presents both a challenge and an opportunity. The challenge: most assessments occur in different environments from where learning happens. The opportunity: by understanding this principle, you can deliberately prepare students for context changes. Try rotating your teaching locations weekly; use the library, outdoor spaces, or even rearrange your classroom furniture regularly. This builds what researchers call "context-independent memories" that students can access anywhere.

Another practical strategy involves teaching students to create internal context cues. Before important topics, have pupils adopt a specific posture, breathing pattern, or mental visualisation they can recreate during exams. Research shows these self-generated cues can substitute for missing environmental triggers.

Most importantly, explicitly discuss this phenomenon with your students. When they understand why practising in varied conditions improves exam performance, they're more likely to embrace changes in their learning environment rather than resist them. This metacognitive awareness transforms context-dependent learning from a limitation into a tool for academic success.

The brain doesn't store memories as isolated facts; it weaves them into rich networks that include sensory details from the learning environment. When students study in your classroom, their brains automatically encode the squeaky chair, the poster on the wall, even the smell of whiteboard markers alongside the curriculum content. These environmental cues become retrieval triggers, helping students access information later.

This happens through a process called encoding specificity. During learning, the hippocampus, your brain's memory hub, binds together the content (what you're learning) with the context (where and how you're learning it). Later, when students encounter similar environmental cues, these act as memory prompts, making recall easier. However, when the context changes dramatically, such as moving from a familiar classroom to an exam hall, students lose these helpful triggers.

Research by Godden and Baddeley demonstrated this powerfully: divers who learnt word lists underwater recalled them better underwater than on land, and vice versa. While we can't submerge our students, we can apply this principle practically. Try teaching the same topic in three different locations: your regular classroom, the library, and outdoors. This forces students' brains to create multiple retrieval routes to the same information, reducing dependence on any single context.

Another effective strategy involves teaching students to become aware of their internal context. Before a lesson, ask students to note their mood and energy level. Then, during revision, encourage them to practise recalling information whilst deliberately varying their internal state: when tired, alert, anxious, or calm. This builds context-independent memory that survives the stress and unfamiliarity of exam conditions.

Context-dependent learning means students remember information better when the retrieval environment matches where they learned it. The physical location, sounds, and even smells during learning become retrieval cues that help access memories. This explains why students who know material perfectly in class may struggle in unfamiliar exam halls.

Teachers should vary where and how students practise important concepts rather than always using the same classroom setup. This includes changing seating arrangements, using different rooms, and practising skills in conditions similar to assessment environments. Teachers should also familiarise students with exam venues before tests and teach mental reinstatement techniques.

Context-dependent memory relates to external environmental factors like location, sounds, and smells present during learning. State-dependent memory refers to internal conditions such as mood, energy level, or physical condition. Both types become associated with memories and can affect retrieval when conditions match or mismatch.

Students experience context mismatch when they learn in familiar classrooms but take exams in unfamiliar halls, creating a genuine cognitive disadvantage. The visual environment of their regular classroom activates memories of previous learning, whilst unfamiliar exam halls lack these contextual cues. This context dependence adds to exam anxiety and can impair memory retrieval.

Teachers can familiarise students with exam venues before exams and practise retrieval in varied physical locations. They should teach mental reinstatement techniques, helping students visualise where they learned information and how they felt. Creating positive emotional states during learning may also support retrieval in similar positive states.

Godden and Baddeley's 1975 experiment showed that divers who were tested in the same environment they learned in remembered about substantially more than those tested in a different environment. This classic study demonstrates that memories aren't stored as isolated files but as patterns that include contextual elements. When you encounter the same context again, those cues help reactivate the complete memory pattern.

Teachers should deliberately vary learning contexts during initial instruction to produce more flexible, transferable knowledge. Lesson planning should include exposure to different contexts during learning rather than consistent environmental conditions. This approach helps students build knowledge that can be accessed in various situations, including formal assessments and real-world applications.

These peer-reviewed studies provide the research foundation for the strategies discussed in this article:

Teaching Children With Hearing Loss to Recognise Speech: Gains Made With Computer-Based Auditory and/or Speechreading Training View study ↗

12 citations

N. Tye‐Murray et al. (2021)

This research demonstrates that children with hearing loss learn speech recognition best when training conditions match real-world situations where they need to use these skills. The study reveals how computer-based training programmes can be designed to maximise transfer to actual classroom conversations and interactions. For teachers working with hearing-impaired students, this highlights the importance of practising communication skills in contexts that mirror the environments where students will actually need to apply them.

Self-regulated Learning in Physical Education: An Analysis of Perceived Teacher Learning Support and Perceived Motivational Climate as Context Dependent Predictors in Upper Secondary School View study ↗

19 citations

Aron Laxdal et al. (2020)

This study of over 550 high school students found that the classroom environment teachers create directly impacts students' ability to manage their own learning in physical education. Students developed stronger self-regulation skills when teachers provided supportive learning environments rather than competitive, ego-focused climates. The findings emphasise how teachers' approach to motivation and support must be tailored to the specific subject context to help students become independent learners.

The Application of Transfer-Appropriate Processing for Enhancing Reading Comprehension of Chinese High Schoolers View study ↗

Shaoying Sun (2024)

This research shows that Chinese high school students learning English significantly improved their reading comprehension when practise activities closely matched the types of thinking required in actual reading tasks. The study demonstrates how aligning teaching methods with the cognitive processes students need for real reading situations leads to better skill transfer. Teachers can apply this principle by ensuring their reading instruction mirrors the mental strategies students will use when reading independently.

Environment Context Variability and Incidental Word Learning: A Virtual Reality Study View study ↗

5 citations

Francisco Rocabado et al. (2022)

Using virtual reality technology, researchers discovered that students learned vocabulary more effectively when the visual environment remained consistent between learning and testing situations. This study reveals how environmental context affects memory formation and retrieval, suggesting that dramatic changes in classroom setup or learning environments can hinder student performance. Teachers should consider maintaining consistent visual and contextual cues when introducing new vocabulary to improve student retention and recall.

Analysis of the Relationship Between Motivation and Learning Outcomes of Chinese Language Education Students Class of 2022 Semarang State University in the Chuji Hanyu Xiezuo Xia Course View study ↗

This study examined how student motivation directly correlates with academic success in a basic Chinese writing course at the university level. The research provides evidence that understanding and developing student motivation is particularly crucial in language learning contexts where students face significant cognitive challenges. For language teachers, this underscores the importance of identifying and nurturing different types of motivation to improve learning outcomes in skill-specific courses like writing.

Context-dependent learning is a powerful memory principle that can dramatically improve your students' exam performance by teaching them to recall information in varied environments. When students learn and practise material in different contexts, different rooms, seating arrangements, or conditions, they build stronger, more flexible memory pathways that work even under exam pressure. This technique explains why some students excel in classroom discussions but struggle during tests: they've only strengthened their memory in one specific context. By strategically varying the learning environment, you can help students access their knowledge anywhere, anytime. Here's how to harness this principle to transform your teaching and boost your students' results.

This frustrating phenomenon has a scientific explanation. Context-dependent learning describes how the context in which we learn becomes linked to what we learn. When retrieval context matches learning context, memory works well. When contexts differ, retrieval becomes harder, even though the information is still there.

Understanding context-dependent learning helps teachers prepare students for the reality that exams, assessments, and real-world applications rarely occur in the exact conditions where learning happened. This insight should inform how we design learning objectivesand plan lessons. By deliberately varying learning contexts and teaching students about how context affects memory, we can build more transferable knowledge through effective supporting student learning strategies.

Context-dependent learning means students remember information better when the retrieval environment matches where they learned it. The physical location, sounds, and even smells during learning become retrieval cues that help access memories. Teachers can improve student performance by varying practise contexts and explicitly teaching about these memory effects.

Context-dependent memory refers to the improved ability to retrieve information when the external environment at retrieval matches the environment at encoding. The sights, sounds, smells, and physical circumstances present during learning become associated with the memory and can later serve as retrieval cues.

The classic demonstration comes from Godden and Baddeley's 1975 experiment with scuba divers. Divers learned word lists either underwater or on dry land, then were tested in either the same or different environment. Those tested in the same environment they learned in remembered about 50% more than those tested in a different environment.

Research Update: A 2021 replication study by Murre and colleagues, published in Royal Society Open Science, failed to reproduce the original Godden and Baddeley (1975) scuba diver findings under similar conditions. This suggests that while context-dependent memory effects are real, they may be smaller and more variable than the classic study indicated. The Smith and Vela (2001) meta-analysis provides more strong support for the general phenomenon. Mental reinstatement strategies remain valuable for students who cannot physically return to learning contexts.

This finding has been replicated across many contexts. This finding has been replicated across many contexts, from oracy skillsdevelopment to academic subjects. Students who learn in one classroom and are tested in another often perform worse than those tested where they learned. Even subtle environmental changes can affect retrieval.

Context dependence reflects a fundamental feature of how memory works. Memories aren't stored as isolated files but as patterns of neural activation that include contextual elements. When you encounter the same context again, those contextual cues help reactivate the complete memory pattern.

The brain encodes environmental details alongside the actual information being learned, creating multiple retrieval pathways. When students encounter similar environmental cues later, these activate the associated memories through a process called cue-dependent retrieval. This happens automatically and explains why students often perform better in their regular classroom than in unfamiliar exam halls.

Understanding why context matters helps teachers design instruction that builds transferable knowledge.

Endel Tulving's encoding specificity principle states that retrieval cues are effective only to the extent that they were encoded along with the target information. Information is always learned in a context, and that context becomes part of what's encoded.

When you learn something in a particular room, aspects of that room become associated with the memory. The colour of the walls, the arrangement of desks, the ambient sounds all get encoded alongside the academic content. These contextual elements then serve as retrieval cues.

Retrieval works by pattern matching. When you encounter cues similar to what was encoded, the complete memory pattern becomes activated. Contextual cues help discriminate between similar memories, directing retrieval towards information learned in this specific setting.

In a familiar classroom, the visual environment activates memories of previous learning in that space. This contextual priming makes related academic content more accessible. In an unfamiliar exam hall, these cues are absent.

Mental reinstatement can partly substitute for physical context reinstatement. If students mentally imagine the original learning context, they can sometimes access context-dependent memories even when physically in a different environment.

This has practical implications. Teaching students to visualise where they learned information, what was happening, and how they felt can support retrieval in novel contexts.

State-dependent memory means students recall information better when their internal state (mood, energy level, or physical condition) matches their state during learning. A calm student who learned material while relaxed may struggle to recall it when anxious during a test. Teachers can help by teaching relaxation techniques and ensuring students practise under various emotional conditions.

Closely related to context-dependent memory is state-dependent memory, where internal states at encoding and retrieval affect memory accessibility.

Memories encoded in a particular mood are more accessible when that mood recurs. Happy memories are more easily retrieved when happy; sad memories when sad. This creates self-reinforcing patterns that can contribute to depression or anxiety.

For teachers, this suggests that creating positive emotional states during learning may support retrieval in similar positive states. However, since exams often produce anxiety, learning in consistently positive states might create a mismatch.

Studies have shown that memory is better when the pharmacological state at retrieval matches encoding. Students who drink coffee while studying retrieve better when caffeinated during testing than when uncaffeinated, for example.

This isn't an argument for constant caffeine consumption, but it illustrates how internal states, like external contexts, become associated with memories.

Physical states also matter. Learning while hungry versus satiated, tired versus alert, or active versus sedentary can create state-dependent memory effects. This adds complexity to the relationship between context and retrieval.

Context-dependent learning suggests teachers should vary where and how students practise important concepts rather than always using the same classroom setup. Students need exposure to different contexts during learning to build flexible knowledge that transfers to new situations. This includes changing seating arrangements, using different rooms, and practising skills in conditions similar to AI-powered assessment environments.

Context dependence has several practical implications for teaching and learning.

Students typically learn in familiar classrooms but take high-stakes exams in unfamiliar halls. This context mismatch can impair retrieval, adding to exam anxiety a genuine cognitive disadvantage.

Schools can address this by:

If learning is too tied to a single context, knowledge becomes inflexible. Students may know something perfectly in the classroom where they learned it but struggle to apply the same knowledge elsewhere.

The solution is varied practise: learning and retrieving in multiple contexts. When information is encoded across different environments, it becomes associated with multiple contextual cues, making it accessible from more retrieval situations.

This principle explains why learning only in the classroom can produce poor transfer to real-world applications. Varied learning contexts produce more flexible, applicable knowledge.

Homework provides learning opportunities outside the classroom context. This variation can actually strengthen memory by creating additional contextual associations.

Students who only study in one location might consider deliberately varying their study environments. The short-term inconvenience may pay off in more flexible retrieval.

Teachers can use interleaving practise across different classroom spaces and vary the physical setup during learning activities. Having students teach concepts to peers in different locations builds context-independent understanding. Regular practise tests in the actual exam room also helps students adapt to that specific environment before high-stakes assessments.

Several strategies help students build context-independent knowledge.

When possible, vary where learning and practise occur. Conduct some revision in different classrooms, outside spaces, or even corridors. The variety produces memories associated with multiple contexts.

This is especially important for content that students will need to retrieve in novel situations, such as exam halls or real-world applications.

Varying how content is presented creates different encoding contexts even within the same physical space. The same content encountered through reading, discussion, diagram analysis, and hands-on activity builds multiple memory traces with different contextual associations.

Dual coding, presenting information both verbally and visually, creates multiple encoding routes tha t don't all depend on the same contextual cues.

Practising the same type of problem repeatedly in the same format creates context-dependent procedural knowledge. Varying problem formats, wordings, and presentation styles builds more flexible skills.

Interleaving different problem types naturally varies context, as does mixing old and new content in practise sessions.

If exams will occur in unfamiliar environments, practise retrieval in varied and unfamiliar settings. This builds tolerance for context change and creates memories associated with multiple contextual cues.

Retrieval practise conducted only in the regular classroom produces retrieval skills tuned to that context. Retrieval practised across contexts produces more strong skills.

Students can partly compensate for context mismatch by mentally reinstating the learning context. Before attempting retrieval, they visualise where they learned the material, what was happening, and how they felt.

This technique doesn't fully eliminate context effects, but it can help bridge the gap between learning and testing environments. Students facing exams in unfamiliar halls might benefit from spending a moment visualising their classroom before beginning.

While external context is hard to control, internal cues can be made more consistent. Encouraging students to adopt consistent pre-study and pre-exam routines may create state-dependent bridges between learning and testing.

Taking a few deep breaths, reviewing key concepts briefly, or engaging in a consistent mental preparation routine could help align internal states across contexts.

Transfer improves when students practise applying knowledge in multiple contexts from the beginning rather than mastering it in one setting first. Teachers should explicitly connect new situations to previous learning and help students identify underlying principles that remain constant across contexts. Using real-world examples and field trips provides authentic contexts that enhance transfer.

Context dependence relates closely to transfer of learning: the application of knowledge and skills to new situations.

Transfer is difficult partly because learning contexts differ from application contexts. Knowledge encoded in a classroom context may not activate when needed in a workplace, home, or novel problem-solving situation.

The more learning is tied to specific contextual cues, the harder transfer becomes. This is why transfer of learning requires deliberate attention rather than occurring automatically.

To support transfer, learning should occur across varied contexts and with explicit attention to how knowledge applies beyond the immediate situation. Discuss when and where the learning would be useful. Practise applying knowledge to varied scenarios.

Abstract principles transfer better than context-specific procedures because they're encoded less tightly to particular circumstances. Teaching underlying principles alongside specific examples supports flexible application.

Knowledge intended for real-world use should be practised in contexts approximating real-world conditions. Learning only in idealised classroom conditions can produce knowledge that feels unavailable when actually needed.

This is why practical applications, field trips, simulations, and authentic tasks support transfer. They create learning associated with contexts similar to eventual use.

Subjects requiring rote memorization like vocabulary, historical dates, and scientific formulas show the strongest context effects. Mathematics and problem-solving subjects are moderately affected, while conceptual understanding in subjects like literature shows less context dependence. Physical skills in PE and arts subjects are highly context-sensitive and require practise in performance settings.

Context effects appear across all subject areas, though their strength varies.

Language learningshows strong context effects. Vocabulary learned in classroom drills may not come to mind in actual conversations. Phrases practised in one context may feel unavailable in another.

This argues for practising language in varied communicative contexts rather than only through repetitive drills. Role plays, conversations about varied topics, and language use outside formal lessons all build more flexible linguistic knowledge.

Mathematical procedures learned in textbook problem contexts may not transfer to word problems, real-world applications, or differently formatted questions. The surface features of how problems appear can create context dependence.

Varying problem formats and presentation styles during learning builds more flexible mathematical knowledge. Including problems with unfamiliar surface features helps break context dependence.

Scientific knowledge often fails to transfer from classroom contexts to everyday reasoning. Students may correctly answer school science questions while maintaining everyday misconceptions in out-of-school contexts.

Addressing this requires explicitly connecting school science to everyday phenomena and practising scientific reasoning in varied contexts beyond formal instruction.

Historical knowledge can become tied to the specific narratives and contexts in which it was taught. Students may struggle to recognise the same historical principles operating in unfamiliar periods or regions.

Comparing cases, drawing parallels across time periods, and practising historical reasoning with varied examples builds more transferable historical thinking.

Some researchers hypothesise that students with anxiety, ADHD, or autism spectrum conditions may show stronger context-dependent effects, as environmental changes could be more transformative to their cognitive processes. However, research in this area remains limited and findings are mixed. Younger students and those new to a subject also rely more heavily on contextual cues. Teachers can provide extra support by gradually introducing context variations and teaching explicit memory strategies.

Students vary in how strongly context affects their memory.

Students with higher working memorycapacity may be less susceptible to context dependence because they can more effectively use internal retrieval strategies that don't rely on external cues.

Students with working memory limitations might benefit more from context consistency or more intensive practise with mental reinstatement strategies.

Anxious students may show stronger context effects because anxiety consumes cognitive resources that could otherwise support flexible retrieval. High-stakes testing contexts that produce anxiety are particularly problematic.

Reducing exam anxiety through familiarisation, practise, and stress management may indirectly reduce context dependence effects for anxious students.

Students with strong prior knowledge can rely more on internal conceptual connections and less on external contextual cues. Their knowledge is better integrated into stable schemas that don't depend heavily on context for activation.

Building strong conceptual understanding, not just isolated facts, produces more context-independent knowledge.

Students should study in multiple locations and vary their study conditions, including noise levels and time of day. Creating mental contexts through visualision and self-testing in different environments builds stronger, more flexible memories. Teaching the material to others and using varied practise problems helps develop understanding that transcends specific contexts.

Students can use context research to improve their own learning and revision.

Rather than always studying in the same place, varying study locations produces memories associated with multiple contexts. This reduces dependence on any single environment for retrieval.

Practising under exam-like conditions creates memories associated with contexts similar to actual exams. Timed practise in quiet, unfamiliar settings may transfer better to exam halls than relaxed practise in comfortable home environments.

Before attempting recall, mentally return to where the learning occurred. Visualise the room, the page, the discussion. This partial reinstatement can improve retrieval even when physical context differs.

Students who understand context dependence can make better study decisions. Knowing that learning in only one context produces inflexible knowledge encourages deliberate variation.

Metacognitive awareness of how memory works supports better learning strategies.

Schools can redesign assessment practices to include familiar context elements or provide practise sessions in exam venues. Professional development should train teachers to vary instructional contexts and explicitly discuss memory strategies with students. Creating flexible learning spaces that can be reconfigured supports deliberate context variation in daily teaching.

Context-dependent learning reveals that memory is not just about what we learn but where and how we learn it. This has practical implications for instruction, revision, and assessment.

Teachers can support context-independent learning by:

Students can reduce context dependence by:

The goal isn't to eliminate context effects, which are deeply embedded in how memory works, but to build knowledge flexible enough to survive context changes.

Godden and Baddeley's 1975 underwater learning study provides the foundational evidence for environmental context effects. Smith and Vela's 2001 meta-analysis synthesizes decades of classroom-relevant research on context-dependent memory. Bjork and Bjork's work on desirable difficulties explains why varied practise contexts improve long-term retention despite making initial learning harder.

The following papers provide deeper exploration of context effects and their implications.

The classic underwater experiment demonstrating context-dependent memory. Scuba divers remembered word lists better when tested in the same environment where they learned, establishing context reinstatement as a powerful factor in retrieval.

Endel Tulving's foundational paper on encoding specificity, explaining how retrievalcues only work if they were encoded with the target information. This theoretical framework underpins understanding of context-dependent memory.

This study examines how context affects different aspects of memory, distinguishing between familiarity and recollection. The research helps explain when context effects are strongest and why.

Eric Eich's research on state-dependent memory demonstrates that internal states, like external contexts, become associated with memories. This extends context dependence beyond physical environments.

This comprehensive review synthesises research on context effects in memory, examining when effects are strongest and strategies for overcoming context dependence. The paper addresses educational implications directly.

���

Context-dependent memory is the brain's tendency to recall information more effectively when the retrieval environment matches the original learning environment. Put simply, students remember better when they're in the same place, mood, or situation where they first learnt the material. This phenomenon, first demonstrated by Godden and Baddeley's 1975 underwater study, shows that divers who learnt word lists underwater recalled them better underwater than on dry land, and vice versa.

The implications for teaching are profound. When students revise exclusively in their bedrooms, their memory becomes tied to that specific context; the familiar posters, desk arrangement, and even background sounds all become retrieval cues. Move them to an unfamiliar exam hall, and these contextual anchors vanish, making recall significantly harder. This explains why capable students sometimes underperform in tests despite knowing the material well.

Context extends beyond physical location. Internal states matter too: if students learn whilst relaxed and well-rested, they may struggle to access that knowledge when anxious during exams. Even seemingly trivial details like background music, room temperature, or the presence of classmates can become part of the memory trace.

As teachers, we can turn this principle to our advantage. Try teaching the same topic in different classrooms, or occasionally hold revision sessions in the sports hall where exams take place. Encourage students to vary their study locations at home, perhaps alternating between the kitchen table, library, and bedroom. When introducing crucial exam content, deliberately create neutral conditions that mirror test environments: silence, individual work, and timed practise. This builds what researchers call "context-independent" memories that remain accessible regardless of surroundings.

Context-dependent learning shows that students remember information best when their retrieval environment matches where they originally learnt it. This psychological principle, first documented by Godden and Baddeley in their underwater memory experiments, explains why pupils often struggle to recall classroom knowledge during exams in unfamiliar halls.

The core mechanism involves environmental cues becoming encoded alongside the actual learning material. When students study in their usual classroom, everything from the wall displays to the seating arrangement becomes part of their memory network. Remove these cues, and accessing the information becomes significantly harder, even though the knowledge remains intact.

For teachers, this presents both a challenge and an opportunity. The challenge: most assessments occur in different environments from where learning happens. The opportunity: by understanding this principle, you can deliberately prepare students for context changes. Try rotating your teaching locations weekly; use the library, outdoor spaces, or even rearrange your classroom furniture regularly. This builds what researchers call "context-independent memories" that students can access anywhere.

Another practical strategy involves teaching students to create internal context cues. Before important topics, have pupils adopt a specific posture, breathing pattern, or mental visualisation they can recreate during exams. Research shows these self-generated cues can substitute for missing environmental triggers.

Most importantly, explicitly discuss this phenomenon with your students. When they understand why practising in varied conditions improves exam performance, they're more likely to embrace changes in their learning environment rather than resist them. This metacognitive awareness transforms context-dependent learning from a limitation into a tool for academic success.

The brain doesn't store memories as isolated facts; it weaves them into rich networks that include sensory details from the learning environment. When students study in your classroom, their brains automatically encode the squeaky chair, the poster on the wall, even the smell of whiteboard markers alongside the curriculum content. These environmental cues become retrieval triggers, helping students access information later.

This happens through a process called encoding specificity. During learning, the hippocampus, your brain's memory hub, binds together the content (what you're learning) with the context (where and how you're learning it). Later, when students encounter similar environmental cues, these act as memory prompts, making recall easier. However, when the context changes dramatically, such as moving from a familiar classroom to an exam hall, students lose these helpful triggers.

Research by Godden and Baddeley demonstrated this powerfully: divers who learnt word lists underwater recalled them better underwater than on land, and vice versa. While we can't submerge our students, we can apply this principle practically. Try teaching the same topic in three different locations: your regular classroom, the library, and outdoors. This forces students' brains to create multiple retrieval routes to the same information, reducing dependence on any single context.

Another effective strategy involves teaching students to become aware of their internal context. Before a lesson, ask students to note their mood and energy level. Then, during revision, encourage them to practise recalling information whilst deliberately varying their internal state: when tired, alert, anxious, or calm. This builds context-independent memory that survives the stress and unfamiliarity of exam conditions.

Context-dependent learning means students remember information better when the retrieval environment matches where they learned it. The physical location, sounds, and even smells during learning become retrieval cues that help access memories. This explains why students who know material perfectly in class may struggle in unfamiliar exam halls.

Teachers should vary where and how students practise important concepts rather than always using the same classroom setup. This includes changing seating arrangements, using different rooms, and practising skills in conditions similar to assessment environments. Teachers should also familiarise students with exam venues before tests and teach mental reinstatement techniques.

Context-dependent memory relates to external environmental factors like location, sounds, and smells present during learning. State-dependent memory refers to internal conditions such as mood, energy level, or physical condition. Both types become associated with memories and can affect retrieval when conditions match or mismatch.

Students experience context mismatch when they learn in familiar classrooms but take exams in unfamiliar halls, creating a genuine cognitive disadvantage. The visual environment of their regular classroom activates memories of previous learning, whilst unfamiliar exam halls lack these contextual cues. This context dependence adds to exam anxiety and can impair memory retrieval.

Teachers can familiarise students with exam venues before exams and practise retrieval in varied physical locations. They should teach mental reinstatement techniques, helping students visualise where they learned information and how they felt. Creating positive emotional states during learning may also support retrieval in similar positive states.

Godden and Baddeley's 1975 experiment showed that divers who were tested in the same environment they learned in remembered about substantially more than those tested in a different environment. This classic study demonstrates that memories aren't stored as isolated files but as patterns that include contextual elements. When you encounter the same context again, those cues help reactivate the complete memory pattern.

Teachers should deliberately vary learning contexts during initial instruction to produce more flexible, transferable knowledge. Lesson planning should include exposure to different contexts during learning rather than consistent environmental conditions. This approach helps students build knowledge that can be accessed in various situations, including formal assessments and real-world applications.

These peer-reviewed studies provide the research foundation for the strategies discussed in this article:

Teaching Children With Hearing Loss to Recognise Speech: Gains Made With Computer-Based Auditory and/or Speechreading Training View study ↗

12 citations

N. Tye‐Murray et al. (2021)

This research demonstrates that children with hearing loss learn speech recognition best when training conditions match real-world situations where they need to use these skills. The study reveals how computer-based training programmes can be designed to maximise transfer to actual classroom conversations and interactions. For teachers working with hearing-impaired students, this highlights the importance of practising communication skills in contexts that mirror the environments where students will actually need to apply them.

Self-regulated Learning in Physical Education: An Analysis of Perceived Teacher Learning Support and Perceived Motivational Climate as Context Dependent Predictors in Upper Secondary School View study ↗

19 citations

Aron Laxdal et al. (2020)

This study of over 550 high school students found that the classroom environment teachers create directly impacts students' ability to manage their own learning in physical education. Students developed stronger self-regulation skills when teachers provided supportive learning environments rather than competitive, ego-focused climates. The findings emphasise how teachers' approach to motivation and support must be tailored to the specific subject context to help students become independent learners.

The Application of Transfer-Appropriate Processing for Enhancing Reading Comprehension of Chinese High Schoolers View study ↗

Shaoying Sun (2024)

This research shows that Chinese high school students learning English significantly improved their reading comprehension when practise activities closely matched the types of thinking required in actual reading tasks. The study demonstrates how aligning teaching methods with the cognitive processes students need for real reading situations leads to better skill transfer. Teachers can apply this principle by ensuring their reading instruction mirrors the mental strategies students will use when reading independently.

Environment Context Variability and Incidental Word Learning: A Virtual Reality Study View study ↗

5 citations

Francisco Rocabado et al. (2022)

Using virtual reality technology, researchers discovered that students learned vocabulary more effectively when the visual environment remained consistent between learning and testing situations. This study reveals how environmental context affects memory formation and retrieval, suggesting that dramatic changes in classroom setup or learning environments can hinder student performance. Teachers should consider maintaining consistent visual and contextual cues when introducing new vocabulary to improve student retention and recall.

Analysis of the Relationship Between Motivation and Learning Outcomes of Chinese Language Education Students Class of 2022 Semarang State University in the Chuji Hanyu Xiezuo Xia Course View study ↗

This study examined how student motivation directly correlates with academic success in a basic Chinese writing course at the university level. The research provides evidence that understanding and developing student motivation is particularly crucial in language learning contexts where students face significant cognitive challenges. For language teachers, this underscores the importance of identifying and nurturing different types of motivation to improve learning outcomes in skill-specific courses like writing.

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/context-dependent-learning-teachers-guide#article","headline":"Context-Dependent Learning: A Teacher's Guide","description":"Discover how context shapes memory and learning, with practical strategies for helping students retrieve knowledge across different situations and exam...","datePublished":"2025-12-29T10:28:42.668Z","dateModified":"2026-01-26T10:09:32.212Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/context-dependent-learning-teachers-guide"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/69666c015020dd5be3d12c26_69666c006ba5e8d2dcccbebe_context-dependent-learning-teachers-guide-infographic.webp","wordCount":5136},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/context-dependent-learning-teachers-guide#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"Context-Dependent Learning: A Teacher's Guide","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/context-dependent-learning-teachers-guide"}]},{"@type":"FAQPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/context-dependent-learning-teachers-guide#faq","mainEntity":[{"@type":"Question","name":"How can teachers practically apply context-dependent learning principles in their lessons?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Teachers should vary where and how students practise important concepts rather than always using the same classroom setup. This includes changing seating arrangements, using different rooms, and practising skills in conditions similar to assessment environments. Teachers should also familiarise stud"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What is the difference between context-dependent and state-dependent memory?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Context-dependent memory relates to external environmental factors like location, sounds, and smells present during learning. State-dependent memory refers to internal conditions such as mood, energy level, or physical condition. Both types become associated with memories and can affect retrieval wh"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"Why do students sometimes perform worse in exam halls compared to their regular classroom?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Students experience context mismatch when they learn in familiar classrooms but take exams in unfamiliar halls, creating a genuine cognitive disadvantage. The visual environment of their regular classroom activates memories of previous learning, whilst unfamiliar exam halls lack these contextual cue"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"How can teachers help students overcome the challenges of context-dependent learning during assessments?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Teachers can familiarise students with exam venues before exams and practise retrieval in varied physical locations. They should teach mental reinstatement techniques, helping students visualise where they learned information and how they felt. Creating positive emotional states during learning may "}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What does the scuba diving experiment reveal about learning contexts?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Godden and Baddeley's 1975 experiment showed that divers who were tested in the same environment they learned in remembered about substantially more than those tested in a different environment. This classic study demonstrates that memories aren't stored as isolated files but as patterns that includ"}}]}]}