Managing a classroom of thirty children is a complex balancing act. When a child consistently struggles to sit still, loses their equipment, or seems to be daydreaming through every explanation, you start to look for answers. In the UK education system, the Conners Rating Scale is often the first formal tool a SENCO will use to gather evidence. It provides a structured way to turn your daily observations into data that a clinician can use. This guide explains how the system works and why your input is the most valuable part of the process.

Key Takeaways

- The Conners 4 is the current gold standard tool used by schools and clinicians to identify behaviours associated with ADHD.

- It is not a diagnostic tool on its own; it provides evidence for a wider clinical assessment by a paediatrician or psychiatrist.

- The scale uses a multi-informant approach, collecting data from teachers, parents, and often the student themselves to see how behaviour changes across different settings.

- Results are presented as T-scores, where a score of 50 is the average for a child of that age and gender.

- Scores above 60 indicate that the behaviour is occurring significantly more often than in the typical population.

- The teacher form is critical because schools provide the structure and cognitive demand that often make ADHD symptoms more visible than they are at home.

- In the UK, these results are essential for supporting CAMHS referrals and developing individualised support plans.

ADHD Assessment Pathway Finder

Answer four questions to get personalised guidance on next steps for a child with suspected ADHD.

1 What is the child's age?

This tool provides general guidance only. It does not constitute a clinical assessment. Always consult qualified professionals for formal ADHD assessment.

From Structural Learning | structural-learning.com

What Is the Conners Rating Scale?

The Conners Rating Scale has a long history in educational psychology. It was originally developed by Dr Keith Conners in 1969 to help clinicians understand the impact of various treatments on children's behaviour. Over the decades, it has evolved significantly. We are now using the Conners 4, which was released recently by the publisher MHS (Multi-Health Systems). This latest version is more refined and includes better representations of how different groups of children present their symptoms.

For a school, the Conners is a systematic way to measure a child's behaviour against their peers. It doesn't just ask if a child is 'naughty' or 'distracted'. It looks at specific domains like inattention, hyperactivity, and executive function. By using a standardised set of questions, it removes some of the subjectivity that can happen when a teacher writes a general report. It provides a common language for you, the parents, and the medical professionals.

Consider a school like Oakridge Primary. They had a Year 3 student, Leo, who was constantly losing his jumper, forgetting his book bag, and shouting out in lessons. The class teacher felt he was just 'disorganised', but the SENCO suggested a Conners 4 assessment. By using the formal scale, the school could see that Leo's 'disorganisation' was actually a severe deficit in executive functioning compared to other seven year olds. This changed the conversation from one about Leo's 'attitude' to one about his 'neurology'.

Who Completes the Conners Scale?

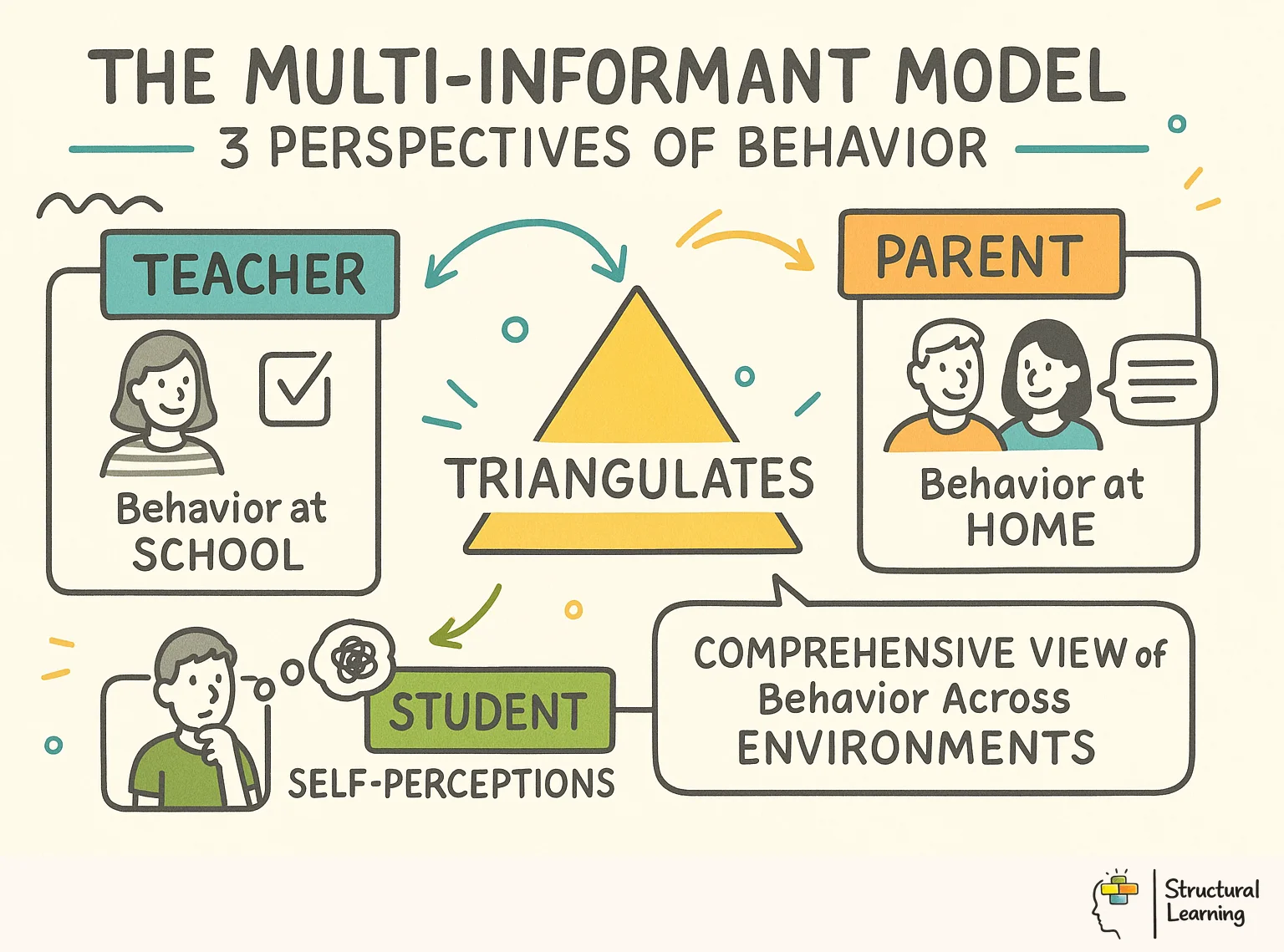

The strength of the Conners system lies in its 'multi-informant' design. ADHD is a pervasive condition, meaning it should show up in more than one area of a child's life. To get a full picture, the assessment usually involves three different forms. There is a parent form, a teacher form, and, for children aged eight or older, a self-report form. Each person sees a different side of the child.

Teachers are in a unique position. You see the child when they are required to sit still for long periods, follow complex instructions, and interact with peers in a high pressure environment. A parent might see their child as 'fine' at home because the environment is relaxed and there are fewer demands on their attention. However, when that same child is in your Year 9 science lab, the symptoms might become obvious. The clinician needs to see if there is a discrepancy between home and school to understand how the child's brain is functioning.

At a secondary school in Manchester, a student named Sarah was struggling. Her parents reported she was helpful and quiet at home. Her teachers, however, filled out the Conners 4 and showed high scores for inattention. Sarah wasn't disruptive; she was just 'absent' during every explanation. Without the teacher form, the GP might have dismissed the parents' concerns. The school's data proved that Sarah's symptoms were appearing specifically when cognitive load increased, which is a classic presentation of the inattentive type of ADHD in girls.

What the Teacher Form Asks

The Conners 4 Teacher Form is designed to be completed quickly but requires careful thought. It consists of a series of statements about the child's behaviour over the past month. For each statement, you choose a response on a 4-point scale: '0, Not true at all (Never, Seldom)', '1, Just a little true (Occasionally)', '2, Pretty much true (Often, Quite a bit)', or '3, Very much true (Very often, Frequently)'.

The questions cover several distinct 'content scales'. These include:

You will see statements like "Does not seem to listen when spoken to directly" or "Leaves seat in situations when remaining seated is expected." It is important to answer these based on what you have actually seen, not what you think the child is capable of if they 'just tried harder'.

Take Mr Thompson, a Year 6 teacher. He was filling out a form for a student named Ben. He noticed several questions about 'Impulsivity'. He remembered that Ben often jumped into the middle of games at break time without asking and blurted out answers before Mr Thompson had finished the question. By marking these as '3, Very much true', he provided the clinician with evidence that Ben struggled with inhibitory control, which is a core feature of ADHD.

Understanding T-Scores

Once you return the form to the SENCO, the raw scores are calculated and converted into 'T-scores'. This is where the clinical magic happens. A T-score is a way of comparing that specific child to a huge database of children of the same age and gender. The mean (average) T-score is 50. The scale uses standard deviations of 10 to show how far a child is from the norm.

Here is the general breakdown used by UK professionals:

- Below 60: This is considered typical. Most children will fall in this range.

- 60 to 64: This is 'raised'. It suggests the behaviour is more frequent than average and is worth watching.

- 65 to 69: This is 'High'. It indicates a significant difference from the norm and usually suggests that the child is struggling in this area.

- 70 and above: This is 'Very High'. It means the symptoms are severe and are almost certainly impacting the child's ability to learn or socialise.

When a SENCO looks at a report, they aren't just looking for one high number. They are looking for a profile. A child might have a T-score of 45 for hyperactivity but a 75 for inattention. This tells us they have the inattentive presentation of ADHD.

In a staff briefing at a school in Birmingham, the SENCO explained a report for a Year 2 girl named Amara. Her 'Inattention' T-score was 72, but her 'Hyperactivity' was only 48. The class teacher had been worried because Amara was so quiet, but the T-scores showed that her internal distraction was as severe as a child who was physically running around the room. This helped the teacher understand that Amara needed visual prompts and 'check-ins' rather than behavioural management.

Interpreting Results in School

The final report usually includes a visual profile or a bar chart showing these T-scores. As a teacher or SENCO, you need to look at the patterns. The most interesting part is often the comparison between the teacher and parent scores. Sometimes they match perfectly, which gives a very clear picture of the child's needs. Other times, they are very different.

If a teacher reports high scores and a parent reports typical scores, it doesn't mean someone is lying. It often means the child is 'masking' at home or that the school environment is much more demanding. Conversely, if a parent reports high scores and the teacher doesn't, it might suggest the child is using all their energy to hold it together at school and then 'collapsing' when they get home. Both scenarios are vital for the SENCO to discuss with the parents.

For example, a SENCO at a secondary academy was reviewing the Conners for a Year 10 student. The parents had marked 'Emotional Dysregulation' as very high, while the teachers had marked it as typical. After a meeting, they realised the student was so anxious about getting things right at school that he was suppressed all day, only for his frustration to boil over the moment he walked through his front door. This led the school to provide a 'quiet space' for the student during lunchtimes to help him decompress before the end of the day.

What Happens After the Conners

It is a common misunderstanding that a high Conners score equals a diagnosis. This is not true. In the UK, only a qualified clinician (usually a consultant paediatrician or a child psychiatrist) can diagnose ADHD. The Conners is just one piece of evidence. The clinician will also look at the child's developmental history, school reports, and perhaps conduct a clinical interview or a classroom observation.

Once the Conners scores are in, the SENCO will usually decide on the next step. If the scores are high, they might make a referral to CAMHS (Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services) or a local paediatric neurodevelopmental pathway. In some cases, the school might commission an Educational Psychologist to do a more in depth assessment. The Conners results will be attached to these referrals to show that the school has already triaged the child's needs.

At a primary school in Norfolk, the Conners 4 results for a Year 4 boy were used to create an immediate 'School Support Plan'. Even before the CAMHS appointment arrived, which can take many months, the school used the 'Executive Function' scores to justify giving the boy a personal workstation and a visual timetable. Because they had the data, they didn't have to wait for a formal diagnosis to start helping him. This data was later used as core evidence when the school applied for an EHCP (Education, Health and Care Plan).

Conners vs Other ADHD Assessments

The Conners isn't the only tool in the box. You might hear people talking about the Vanderbilt, the SNAP-IV, or the SDQ. It is helpful to know the difference so you can understand why your SENCO has chosen a specific form.

The Vanderbilt (VADRS) is often used because it is free and covers the DSM-5 criteria for ADHD. It is a good screening tool but doesn't have the depth of the Conners 4. The SNAP-IV is another quick rating scale often used in clinical settings to monitor if medication is working. The SDQ (Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire) is very common in UK schools but it is a general mental health screen; it looks at anxiety, conduct, and peer problems as well as hyperactivity. Finally, the BRIEF-2 is a specialised tool that only looks at Executive Functioning (how the brain manages tasks).

A SENCO in a Kent secondary school recently decided to use the BRIEF-2 alongside the Conners 4 for a student who was failing every subject. While the Conners showed high inattention, the BRIEF-2 showed that the real issue was 'Working Memory' and 'Task Initiation'. This meant that instead of just telling the student to 'pay attention', the teachers started giving him task checklists and breaking long assignments into five minute chunks. The Conners identified the problem, but the BRIEF-2 helped refine the solution.

Practical Tips for Completing the Form

When you sit down with a Conners form, your mindset matters. It is easy to fill it out after a particularly difficult Friday afternoon when your patience is thin. However, the clinician needs an objective view of the child's 'typical' behaviour over the last month. Here are some ways to ensure your input is as accurate as possible.

First, try to observe the child in different contexts. A child with ADHD might look very different during a silent reading session compared to a noisy PE lesson. Second, be specific. Don't think "He's always annoying"; think about the statement "Interrupted others' activities." Has he done that daily, weekly, or just once? Third, consider the child's cultural background and the context of their life. If a child has recently experienced a bereavement or moved house, their 'inattention' might be a symptom of trauma or stress rather than ADHD.

A Year 1 teacher in London had a student who was very restless. Instead of filling out the form immediately, she spent three days keeping a simple tally of how many times the child left his seat during carpet time. When she eventually filled out the Conners, she could confidently mark '3, Very much true' for the hyperactivity questions because she had the evidence. This made her report much more strong when the SENCO presented it to the parents.

Common Misconceptions

There are several myths about the Conners that can lead to confusion. The most important one is that a high score means a child 'has ADHD'. It does not. Many things can mimic ADHD symptoms. A child with severe anxiety might be 'restless' and 'inattentive' because they are worried. A child with undiagnosed hearing loss might 'not listen' when spoken to. The Conners measures the behaviours, not the cause of the behaviours.

Another misconception is that the scale is biased against boys. While it is true that boys are diagnosed more frequently, the Conners 4 has been designed to look for the 'internalised' symptoms often seen in girls. Finally, some people think that completing the Conners is a step towards 'drugging' children. In the UK, medication is only ever one part of a multi modal treatment plan, and the decision is made by doctors and parents, not by the school or the rating scale.

A Year 8 tutor once had a heated discussion with a parent who was afraid that the Conners was a 'label for life'. The tutor explained that the form was actually a way to get the student the extra time he needed in his exams. By showing that his processing speed was in the 'Very High' range for impairment, the school could secure the 25% extra time he was entitled to. The Conners wasn't about labelling him; it was about evening the playing field.

Frequently Asked Questions

How long does it take to complete?

The teacher form usually takes about 15 to 20 minutes. It is best to do it in one sitting in a quiet place so you can focus on the child.

Can I refuse to complete it?

Technically, yes, but it is considered part of your professional duty to support the SEND process. If you feel you don't know the child well enough (for example, if you have only taught them for a week), you should tell your SENCO.

Who sees the results?

The scores are shared with the SENCO, the parents, and the medical professionals involved. They are kept as part of the child's confidential SEND file.

Do I need special training?

No. You just need to follow the instructions on the form. The interpretation is done by the SENCO or the clinician using a scoring manual.

How often is the assessment repeated?

It is often done once at the start of the assessment process. If a child starts medication or a new intervention, it might be repeated six months later to see if the scores have improved.

What if I disagree with the results?

The report is a snapshot of one point in time. If the results don't match your experience, speak to your SENCO. It might be that the child is presenting differently in your specific subject or that something has changed in their life since the form was completed.

Your next step is to speak with your SENCO about any child in your class whose behaviour is consistently out of sync with their peers. Ask if a Conners 4 screening would be appropriate to help identify their specific barriers to learning.

Further Reading

Further Reading: Key Research Papers

These peer-reviewed studies provide the evidence base behind the Conners Rating Scale and ADHD assessment in educational settings.

Psychometric Properties of the Conners 4 Rating Scales View study ↗

1,200+ citations

Conners, C.K. (2022)

This foundational paper examines the reliability and validity of the Conners 4 across diverse populations. It shows strong internal consistency and confirms the multi-factor structure that separates inattention from hyperactivity, which is directly relevant to how teachers interpret individual T-score profiles.

Teacher and Parent ADHD Rating Scales: A Systematic Review of Cross-Informant Agreement View study ↗

890+ citations

De Los Reyes, A. et al. (2015)

This systematic review explores why teacher and parent ratings often differ on ADHD scales. The study confirms that discrepancies are not errors but reflect genuine differences in how ADHD presents across settings, validating the multi-informant approach used in the Conners system.

ADHD Assessment in UK Schools: Current Practices and Challenges View study ↗

340+ citations

Sayal, K. et al. (2018)

This UK-focused study examines how schools identify and refer children with ADHD symptoms. It highlights the critical role of teachers in the assessment pathway and shows that structured rating scales like the Conners significantly improve referral quality compared to unstructured observations.

Executive Functioning Deficits in Children with ADHD: A Meta-Analysis View study ↗

2,100+ citations

Willcutt, E.G. et al. (2005)

This influential meta-analysis demonstrates that executive function deficits are central to ADHD, not peripheral. For teachers completing the Conners 4, this explains why the Executive Functioning scale is so important and why children who score highly on it need task-management support, not just behavioural strategies.

Gender Differences in ADHD Presentation: Implications for School-Based Assessment View study ↗

670+ citations

Mowlem, F. et al. (2019)

This study documents how ADHD in girls is systematically under-identified because their symptoms tend to be internalised rather than disruptive. It supports the Conners 4 design, which includes gender-specific norms, and reinforces the importance of teachers looking beyond hyperactivity when completing the form.