Student Wellbeing: Strategies for Promoting Mental Health in Schools

Explore evidence-based strategies to enhance student wellbeing, support mental health, build resilience, and foster a nurturing school environment.

Explore evidence-based strategies to enhance student wellbeing, support mental health, build resilience, and foster a nurturing school environment.

Student wellbeing directly affects academic performance because anxiety, stress, and emotional dysregulation reduce cognitive capacity for learning, compromising working memory, attenti on, and higher-order thinking skills. Conversely, students who experience academic success develop greater confidence, resilience, and motivation, creating a positive cycle where wellbeing and learning reinforce each other.

The relationship between wellbeing and learning is bidirectional. Students who are anxious, stressed, or emotionally dysregulated have reduced cognitive capacity for learning. Working memory, attention, and higher-order thinking can be particularly impacted in students with developmental delays, making wellbeing support even more crucial for their academic success.hinking and metacognitive skills are all compromised when students are in a state of threat or distress. Conversely, students who experience success in learning develop greater confidence, resilience, and improved student motivation.

This understanding has shifted how schools approach wellbeing, from seeing it as separate from the academic mission to recognising it as fundamental. The Department for Education's guidance emphasises that schools have a role in promoting mental health and wellbeing for all children, not just intervening when problems arise.

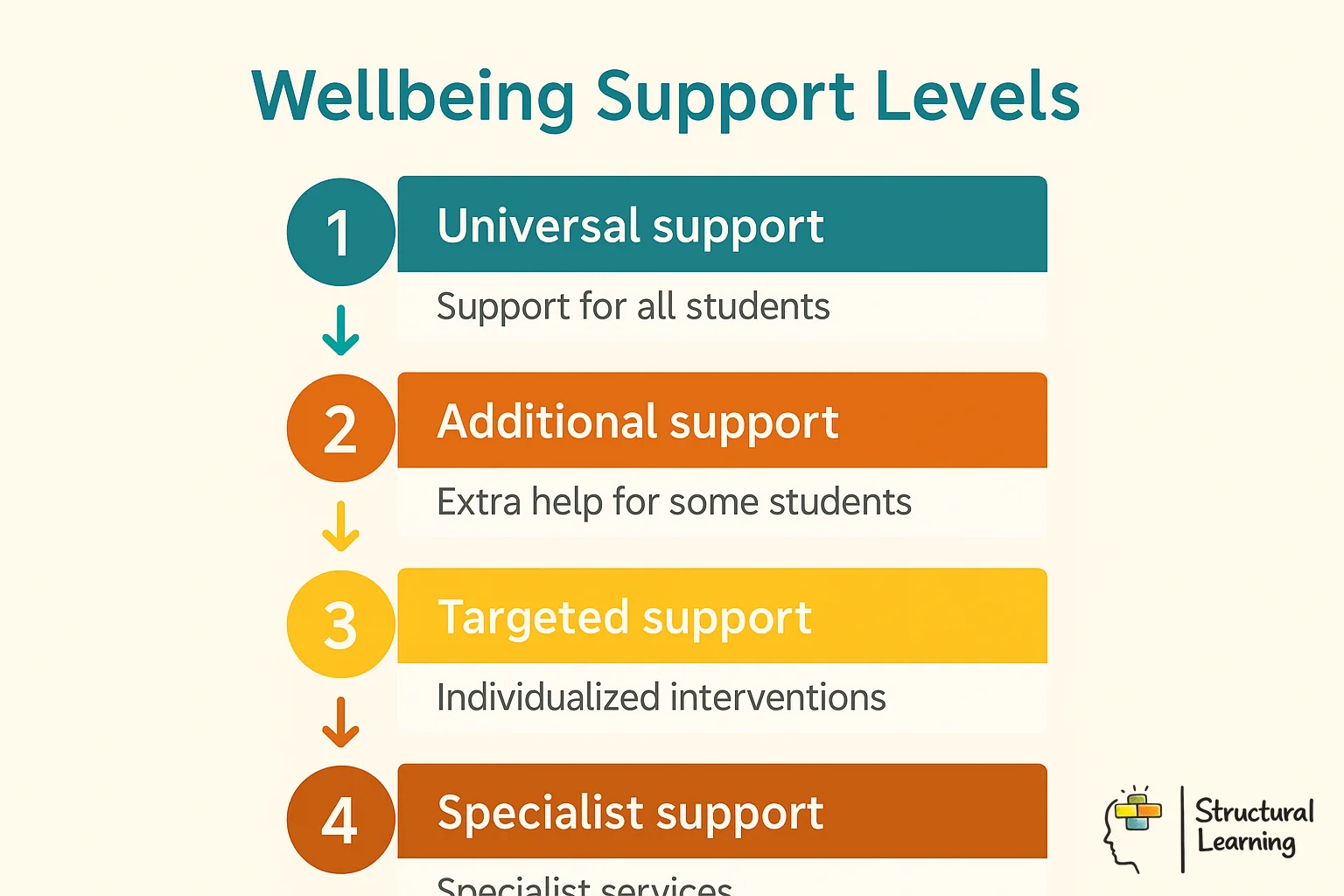

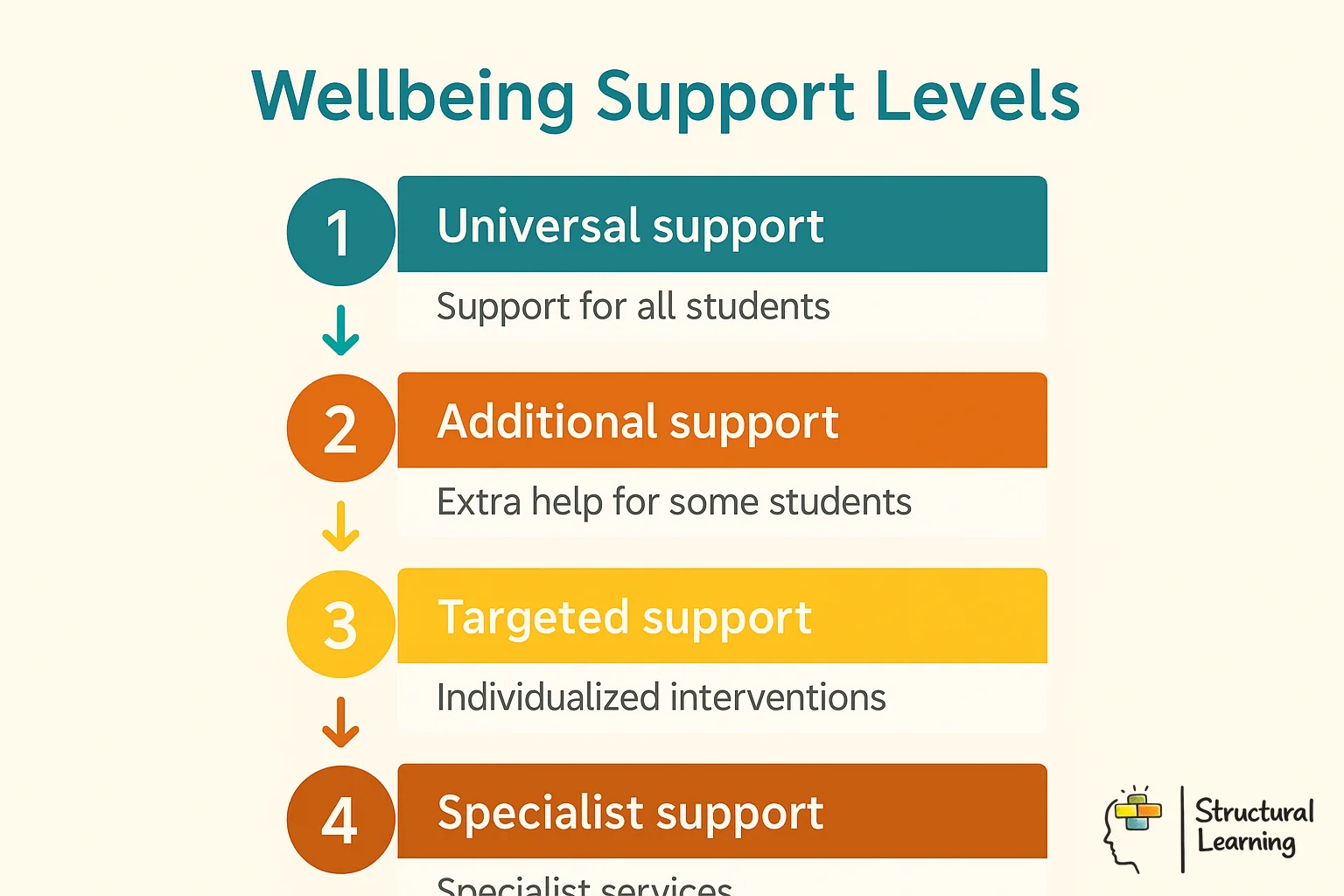

The Public Health England model describes wellbeing support at three levels: Universal (for all students) includes positive school climate and social-emotional skill building; Targeted (for some students) provides additional support for at-risk groups; and Specialist (for few students) offers intensive interventions. This tiered approach ensures all students receive foundational support while those with greater needs access appropriate additional help.

The Public Health England model describes support at three levels:

This includes a positive school climate, strong relationships, inclusive teaching practices, opportunities for physical activity, and curriculum content that build s social-emotional skills. Universal approaches aim to promote wellbeing and build resilience across the student population.

Some students need additional support, such as small group interventions for anxiety, social skills groups, or mentoring programmes. These approaches address emerging concerns b efore they escalate.

A small proportion of students require specialist support from mental health professionals, either w ithin school (educational psychologists, counsellors) or through external services (CAMHS). Schools need clear pathways for referral and communication with specialist services.

Teachers can create a supportive classroom by establishing predictable routines, building positive relationships with all students, and developing a culture where mistakes are viewed as learning opportunities. Key strategies include greeting students at the door, using inclusive teaching practices that accommodate different learning styles, and maintaining consistent expectations while showing flexibility for individual needs.

| Element | Practices |

|---|---|

| Physical environment | Calm displays, adequate lighting, quiet areas available, predictable layout |

| Emotional safety | Mistakes are learning opportunities, no public humiliation, clear expectations fairly enforced |

| Relationships | Learn names quickly, show genuine interest, regular positive interactions with every student |

| Predictability | Consistent routines, clear expectations, advance warning of changes |

| Autonomy support | Appropriate choices, student voice, explaining the "why" behind expectations |

| Belonging | Inclusive language, representing diverse identities, cooperative learning structures |

Research by Professor Carol Dweck emphasises the importance of developing a growth mindset culture where mistakes are viewed as learning opportunities rather than failures. Teachers can implement this by celebrating effort over achievement, using phrases like 'not yet' instead of 'can't do', and sharing their own learning experiences with students.

Physical environment plays a crucial role in supporting wellbeing. Create calm spaces within the classroom using soft lighting, plants, and designated quiet areas where students can self-regulate when feeling overwhelmed. Display positive affirmations and student achievements to build a sense of belonging and pride.

Establishing predictable routines helps students feel secure and reduces anxiety. Begin each day with a brief check-in circle where students can share their emotional state using simple scales or emotion cards. This practice, supported by research from the Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence, helps normalise discussions about feelings whilst providing early intervention opportunities when students need additional mental health support.

Warning signs include sudden changes in behaviour such as withdrawal from friends, declining academic performance, increased irritability, difficulty concentrating, changes in sleep or appetite, expressing feelings of hopelessness or worthlessness, and physical symptoms such as headaches or stomach aches. Being alert to these signs and responding with empathy and appropriate support can significantly improve outcomes for students experiencing mental health challenges.

Implementing early intervention strategies requires a whole-school approach where all staff members are trained to recognise these warning signs consistently. Evidence-based observation techniques include maintaining brief weekly check-ins with students showing concerning patterns, documenting specific behavioural changes rather than general impressions, and creating classroom environments where students feel safe to express difficulties. Teachers should look for clusters of warning signs rather than isolated incidents, as mental health challenges rarely present through single symptoms.

Practical identification strategies include establishing baseline understanding of each student's typical behaviour, academic performance, and social interactions during the first term. When changes occur, consider environmental factors such as family circumstances, peer relationships, or academic pressures that may contribute to declining student wellbeing. Effective mental health support begins with building trusted relationships where students feel comfortable seeking help, combined with clear referral pathways to appropriate support services within the school community.

Prioritising teacher wellbeing is crucial for creating a sustainable and supportive school environment. Schools can implement strategies such as workload management, access to professional development on self-care and stress management, creating supportive staff communities, and ensuring access to mental health resources. Recognising and addressing the pressures teachers face is vital for promoting both teacher and student wellbeing.

Teacher wellbeing directly impacts student wellbeing. Overworked, stressed teachers are less able to provide the consistent, supportive relationships that students need. Strategies to support teacher wellbeing include:

Effective measurement of student wellbeing requires a multi-dimensional approach that captures both quantitative data and qualitative insights. Schools can implement regular wellbeing surveys using validated tools such as the Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale, alongside observational assessments that track behavioural indicators like attendance patterns, peer interactions, and engagement levels. Research by Seligman and colleagues on positive psychology demonstrates that measuring factors such as emotional regulation, social connections, and sense of purpose provides a more comprehensive picture than traditional deficit-focused approaches.

The key to successful monitoring lies in establishing baseline data and tracking changes over time rather than relying on snapshot assessments. Schools should collect data at multiple points throughout the academic year, involving students, teachers, and parents in the process. This triangulated approach ensures that wellbeing measures reflect genuine student experiences rather than temporary fluctuations. Simple classroom-based tools, such as daily mood check-ins or weekly reflection journals, can complement formal assessments while building students' self-awareness and emotional vocabulary.

Most importantly, data collection must translate into practical findings that inform targeted interventions. Schools should establish clear protocols for responding to concerning trends, whether at individual, classroom, or whole-school levels. Regular staff training on interpreting wellbeing data ensures that early warning signs are recognised and appropriate support mechanisms are activated promptly.

Effective parent engagement in student mental health requires schools to move beyond traditional communication methods and establish genuine partnerships built on trust and shared understanding. Research by Joyce Epstein demonstrates that when families are actively involved in their children's wellbeing, students show improved emotional regulation and academic outcomes. Schools can creates this collaboration by providing parents with accessible mental health literacy, including information about recognising early warning signs, understanding developmental changes, and knowing when to seek additional support.

Creating multiple touchpoints throughout the school year ensures consistent engagement rather than crisis-driven contact. Regular wellbeing workshops, informal coffee mornings with school counsellors, and clear communication channels help normalise mental health conversations. Schools should also consider cultural and linguistic diversity when designing engagement strategies, ensuring materials are translated appropriately and culturally sensitive approaches are adopted for different family backgrounds.

Practical implementation begins with establishing a whole-school approach that positions parents as equal partners in the mental health support network. This includes involving families in developing individual wellbeing plans, providing home-school communication tools that track emotional as well as academic progress, and offering flexible meeting times to accommodate working parents. When schools create these supportive frameworks, families feel helped to contribute meaningfully to their children's mental health journey.

A comprehensive whole-school mental health policy should establish clear frameworks for prevention, early intervention, and support across all areas of school life. Research by Kathryn Weare emphasises that effective policies integrate mental health considerations into curriculum planning, staff training protocols, and student support systems. Essential components include explicit procedures for identifying at-risk students, referral pathways to appropriate services, and guidelines for creating psychologically safe learning environments that promote positive mental health outcomes.

The policy must address both reactive and proactive approaches, incorporating evidence-based strategies for crisis response alongside preventative measures such as social-emotional learning programmes and peer support initiatives. Staff wellbeing provisions are equally crucial, as teachers experiencing stress cannot effectively support student mental health. Clear protocols should outline how mental health considerations influence behaviour management approaches, academic expectations, and communication with families.

Implementation requires practical tools including staff training schedules, resource allocation plans, and monitoring systems to evaluate policy effectiveness. Schools should establish regular review cycles that incorporate feedback from students, staff, and families, ensuring the policy remains responsive to community needs. Regular audits of current practice against policy objectives help identify gaps and celebrate successes in promoting student wellbeing.

Effective crisis intervention requires schools to establish clear, evidence-based protocols that prioritise immediate safety whilst connecting students with appropriate support. Research by Suldo and colleagues demonstrates that schools with structured response frameworks significantly improve outcomes during mental health emergencies. These protocols should include immediate risk assessment procedures, defined roles for staff members, and streamlined pathways to professional mental health services.

The most effective crisis response systems adopt a tiered approach that matches intervention intensity to student need. Initial responses should focus on ensuring physical safety and emotional stabilisation, followed by comprehensive risk assessment conducted by trained personnel. Schools must maintain clear documentation procedures and establish robust communication channels with parents, external agencies, and relevant healthcare professionals to ensure continuity of care.

Classroom teachers play a crucial role in early identification and initial response, making regular training essential for all staff. Practical strategies include recognising warning signs, implementing de-escalation techniques, and understanding when to escalate concerns to designated mental health leads. Schools should regularly review and practice these protocols through simulation exercises, ensuring all staff feel confident in their ability to respond appropriately whilst maintaining the supportive classroom environment that underpins effective student wellbeing initiatives.

Mental health strategies must be carefully tailored to developmental stages, as the cognitive and emotional needs of primary pupils differ substantially from those of secondary students. Primary-aged children benefit from concrete, structured approaches that focus on emotional vocabulary building and routine establishment. Research by Marc Brackett demonstrates that emotional literacy programmes at this age create foundational skills for lifelong wellbeing, with activities like feeling wheels and mindfulness breathing proving particularly effective in classroom settings.

Secondary students require more sophisticated interventions that acknowledge their developing autonomy and complex social relationships. Cognitive-behavioural approaches become more viable, as adolescents can engage with abstract concepts about thought patterns and emotional regulation. However, peer influence intensifies significantly during these years, making whole-school approaches to mental health stigma reduction particularly crucial for this age group.

Practical implementation involves adapting communication styles and intervention complexity. Primary teachers might use visual emotion charts and simple coping strategies, whilst secondary educators can introduce concepts like stress management techniques and critical thinking about negative thought patterns. Both age groups benefit from consistent, predictable support structures, but the delivery methods must reflect developmental appropriateness to ensure maximum engagement and effectiveness.

Promoting student wellbeing is not merely a trend, but a fundamental shift in education, recognising that mental health and learning are intrinsically linked. By implementing a whole-school approach, offering tiered support, and helping teachers with the skills and resources they need, schools can create environments where all students feel safe, supported, and ready to learn.

Ultimately, investing in student wellbeing is an investment in their future. A generation of resilient, emotionally intelligent young people are better equipped to navigate the challenges of the modern world and contribute positively to society. Prioritising wellbeing in schools is essential for developing academic success and for nurturing well-rounded, thriving individuals.

The most effective wellbeing initiatives begin with simple, manageable steps that can be embedded into existing routines. For instance, introducing five-minute mindfulness sessions at the start of lessons, establishing peer mentoring programmes, or creating quiet spaces for students to decompress can yield immediate benefits. These foundational changes help build confidence and momentum whilst demonstrating commitment to the whole-school approach.

Professional development plays a crucial role in sustaining wellbeing initiatives. Regular training sessions enable staff to recognise early warning signs, implement classroom-based mental health support strategies, and understand when to refer students to specialist services. This capacity building ensures that early intervention becomes second nature rather than an afterthought, creating a robust safety net for vulnerable students.

Looking ahead, successful schools will be those that view wellbeing not as a separate initiative but as an integral part of their educational mission. By embedding evidence-based mental health practices into policies, curriculum planning, and daily interactions, schools create environments where both students and staff can thrive academically, socially, and emotionally.

For those seeking to examine deeper into the research and evidence supporting student wellbeing initiatives, the following academic papers provide valuable insights:

Student wellbeing directly affects academic performance because anxiety, stress, and emotional dysregulation reduce cognitive capacity for learning, compromising working memory, attenti on, and higher-order thinking skills. Conversely, students who experience academic success develop greater confidence, resilience, and motivation, creating a positive cycle where wellbeing and learning reinforce each other.

The relationship between wellbeing and learning is bidirectional. Students who are anxious, stressed, or emotionally dysregulated have reduced cognitive capacity for learning. Working memory, attention, and higher-order thinking can be particularly impacted in students with developmental delays, making wellbeing support even more crucial for their academic success.hinking and metacognitive skills are all compromised when students are in a state of threat or distress. Conversely, students who experience success in learning develop greater confidence, resilience, and improved student motivation.

This understanding has shifted how schools approach wellbeing, from seeing it as separate from the academic mission to recognising it as fundamental. The Department for Education's guidance emphasises that schools have a role in promoting mental health and wellbeing for all children, not just intervening when problems arise.

The Public Health England model describes wellbeing support at three levels: Universal (for all students) includes positive school climate and social-emotional skill building; Targeted (for some students) provides additional support for at-risk groups; and Specialist (for few students) offers intensive interventions. This tiered approach ensures all students receive foundational support while those with greater needs access appropriate additional help.

The Public Health England model describes support at three levels:

This includes a positive school climate, strong relationships, inclusive teaching practices, opportunities for physical activity, and curriculum content that build s social-emotional skills. Universal approaches aim to promote wellbeing and build resilience across the student population.

Some students need additional support, such as small group interventions for anxiety, social skills groups, or mentoring programmes. These approaches address emerging concerns b efore they escalate.

A small proportion of students require specialist support from mental health professionals, either w ithin school (educational psychologists, counsellors) or through external services (CAMHS). Schools need clear pathways for referral and communication with specialist services.

Teachers can create a supportive classroom by establishing predictable routines, building positive relationships with all students, and developing a culture where mistakes are viewed as learning opportunities. Key strategies include greeting students at the door, using inclusive teaching practices that accommodate different learning styles, and maintaining consistent expectations while showing flexibility for individual needs.

| Element | Practices |

|---|---|

| Physical environment | Calm displays, adequate lighting, quiet areas available, predictable layout |

| Emotional safety | Mistakes are learning opportunities, no public humiliation, clear expectations fairly enforced |

| Relationships | Learn names quickly, show genuine interest, regular positive interactions with every student |

| Predictability | Consistent routines, clear expectations, advance warning of changes |

| Autonomy support | Appropriate choices, student voice, explaining the "why" behind expectations |

| Belonging | Inclusive language, representing diverse identities, cooperative learning structures |

Research by Professor Carol Dweck emphasises the importance of developing a growth mindset culture where mistakes are viewed as learning opportunities rather than failures. Teachers can implement this by celebrating effort over achievement, using phrases like 'not yet' instead of 'can't do', and sharing their own learning experiences with students.

Physical environment plays a crucial role in supporting wellbeing. Create calm spaces within the classroom using soft lighting, plants, and designated quiet areas where students can self-regulate when feeling overwhelmed. Display positive affirmations and student achievements to build a sense of belonging and pride.

Establishing predictable routines helps students feel secure and reduces anxiety. Begin each day with a brief check-in circle where students can share their emotional state using simple scales or emotion cards. This practice, supported by research from the Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence, helps normalise discussions about feelings whilst providing early intervention opportunities when students need additional mental health support.

Warning signs include sudden changes in behaviour such as withdrawal from friends, declining academic performance, increased irritability, difficulty concentrating, changes in sleep or appetite, expressing feelings of hopelessness or worthlessness, and physical symptoms such as headaches or stomach aches. Being alert to these signs and responding with empathy and appropriate support can significantly improve outcomes for students experiencing mental health challenges.

Implementing early intervention strategies requires a whole-school approach where all staff members are trained to recognise these warning signs consistently. Evidence-based observation techniques include maintaining brief weekly check-ins with students showing concerning patterns, documenting specific behavioural changes rather than general impressions, and creating classroom environments where students feel safe to express difficulties. Teachers should look for clusters of warning signs rather than isolated incidents, as mental health challenges rarely present through single symptoms.

Practical identification strategies include establishing baseline understanding of each student's typical behaviour, academic performance, and social interactions during the first term. When changes occur, consider environmental factors such as family circumstances, peer relationships, or academic pressures that may contribute to declining student wellbeing. Effective mental health support begins with building trusted relationships where students feel comfortable seeking help, combined with clear referral pathways to appropriate support services within the school community.

Prioritising teacher wellbeing is crucial for creating a sustainable and supportive school environment. Schools can implement strategies such as workload management, access to professional development on self-care and stress management, creating supportive staff communities, and ensuring access to mental health resources. Recognising and addressing the pressures teachers face is vital for promoting both teacher and student wellbeing.

Teacher wellbeing directly impacts student wellbeing. Overworked, stressed teachers are less able to provide the consistent, supportive relationships that students need. Strategies to support teacher wellbeing include:

Effective measurement of student wellbeing requires a multi-dimensional approach that captures both quantitative data and qualitative insights. Schools can implement regular wellbeing surveys using validated tools such as the Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale, alongside observational assessments that track behavioural indicators like attendance patterns, peer interactions, and engagement levels. Research by Seligman and colleagues on positive psychology demonstrates that measuring factors such as emotional regulation, social connections, and sense of purpose provides a more comprehensive picture than traditional deficit-focused approaches.

The key to successful monitoring lies in establishing baseline data and tracking changes over time rather than relying on snapshot assessments. Schools should collect data at multiple points throughout the academic year, involving students, teachers, and parents in the process. This triangulated approach ensures that wellbeing measures reflect genuine student experiences rather than temporary fluctuations. Simple classroom-based tools, such as daily mood check-ins or weekly reflection journals, can complement formal assessments while building students' self-awareness and emotional vocabulary.

Most importantly, data collection must translate into practical findings that inform targeted interventions. Schools should establish clear protocols for responding to concerning trends, whether at individual, classroom, or whole-school levels. Regular staff training on interpreting wellbeing data ensures that early warning signs are recognised and appropriate support mechanisms are activated promptly.

Effective parent engagement in student mental health requires schools to move beyond traditional communication methods and establish genuine partnerships built on trust and shared understanding. Research by Joyce Epstein demonstrates that when families are actively involved in their children's wellbeing, students show improved emotional regulation and academic outcomes. Schools can creates this collaboration by providing parents with accessible mental health literacy, including information about recognising early warning signs, understanding developmental changes, and knowing when to seek additional support.

Creating multiple touchpoints throughout the school year ensures consistent engagement rather than crisis-driven contact. Regular wellbeing workshops, informal coffee mornings with school counsellors, and clear communication channels help normalise mental health conversations. Schools should also consider cultural and linguistic diversity when designing engagement strategies, ensuring materials are translated appropriately and culturally sensitive approaches are adopted for different family backgrounds.

Practical implementation begins with establishing a whole-school approach that positions parents as equal partners in the mental health support network. This includes involving families in developing individual wellbeing plans, providing home-school communication tools that track emotional as well as academic progress, and offering flexible meeting times to accommodate working parents. When schools create these supportive frameworks, families feel helped to contribute meaningfully to their children's mental health journey.

A comprehensive whole-school mental health policy should establish clear frameworks for prevention, early intervention, and support across all areas of school life. Research by Kathryn Weare emphasises that effective policies integrate mental health considerations into curriculum planning, staff training protocols, and student support systems. Essential components include explicit procedures for identifying at-risk students, referral pathways to appropriate services, and guidelines for creating psychologically safe learning environments that promote positive mental health outcomes.

The policy must address both reactive and proactive approaches, incorporating evidence-based strategies for crisis response alongside preventative measures such as social-emotional learning programmes and peer support initiatives. Staff wellbeing provisions are equally crucial, as teachers experiencing stress cannot effectively support student mental health. Clear protocols should outline how mental health considerations influence behaviour management approaches, academic expectations, and communication with families.

Implementation requires practical tools including staff training schedules, resource allocation plans, and monitoring systems to evaluate policy effectiveness. Schools should establish regular review cycles that incorporate feedback from students, staff, and families, ensuring the policy remains responsive to community needs. Regular audits of current practice against policy objectives help identify gaps and celebrate successes in promoting student wellbeing.

Effective crisis intervention requires schools to establish clear, evidence-based protocols that prioritise immediate safety whilst connecting students with appropriate support. Research by Suldo and colleagues demonstrates that schools with structured response frameworks significantly improve outcomes during mental health emergencies. These protocols should include immediate risk assessment procedures, defined roles for staff members, and streamlined pathways to professional mental health services.

The most effective crisis response systems adopt a tiered approach that matches intervention intensity to student need. Initial responses should focus on ensuring physical safety and emotional stabilisation, followed by comprehensive risk assessment conducted by trained personnel. Schools must maintain clear documentation procedures and establish robust communication channels with parents, external agencies, and relevant healthcare professionals to ensure continuity of care.

Classroom teachers play a crucial role in early identification and initial response, making regular training essential for all staff. Practical strategies include recognising warning signs, implementing de-escalation techniques, and understanding when to escalate concerns to designated mental health leads. Schools should regularly review and practice these protocols through simulation exercises, ensuring all staff feel confident in their ability to respond appropriately whilst maintaining the supportive classroom environment that underpins effective student wellbeing initiatives.

Mental health strategies must be carefully tailored to developmental stages, as the cognitive and emotional needs of primary pupils differ substantially from those of secondary students. Primary-aged children benefit from concrete, structured approaches that focus on emotional vocabulary building and routine establishment. Research by Marc Brackett demonstrates that emotional literacy programmes at this age create foundational skills for lifelong wellbeing, with activities like feeling wheels and mindfulness breathing proving particularly effective in classroom settings.

Secondary students require more sophisticated interventions that acknowledge their developing autonomy and complex social relationships. Cognitive-behavioural approaches become more viable, as adolescents can engage with abstract concepts about thought patterns and emotional regulation. However, peer influence intensifies significantly during these years, making whole-school approaches to mental health stigma reduction particularly crucial for this age group.

Practical implementation involves adapting communication styles and intervention complexity. Primary teachers might use visual emotion charts and simple coping strategies, whilst secondary educators can introduce concepts like stress management techniques and critical thinking about negative thought patterns. Both age groups benefit from consistent, predictable support structures, but the delivery methods must reflect developmental appropriateness to ensure maximum engagement and effectiveness.

Promoting student wellbeing is not merely a trend, but a fundamental shift in education, recognising that mental health and learning are intrinsically linked. By implementing a whole-school approach, offering tiered support, and helping teachers with the skills and resources they need, schools can create environments where all students feel safe, supported, and ready to learn.

Ultimately, investing in student wellbeing is an investment in their future. A generation of resilient, emotionally intelligent young people are better equipped to navigate the challenges of the modern world and contribute positively to society. Prioritising wellbeing in schools is essential for developing academic success and for nurturing well-rounded, thriving individuals.

The most effective wellbeing initiatives begin with simple, manageable steps that can be embedded into existing routines. For instance, introducing five-minute mindfulness sessions at the start of lessons, establishing peer mentoring programmes, or creating quiet spaces for students to decompress can yield immediate benefits. These foundational changes help build confidence and momentum whilst demonstrating commitment to the whole-school approach.

Professional development plays a crucial role in sustaining wellbeing initiatives. Regular training sessions enable staff to recognise early warning signs, implement classroom-based mental health support strategies, and understand when to refer students to specialist services. This capacity building ensures that early intervention becomes second nature rather than an afterthought, creating a robust safety net for vulnerable students.

Looking ahead, successful schools will be those that view wellbeing not as a separate initiative but as an integral part of their educational mission. By embedding evidence-based mental health practices into policies, curriculum planning, and daily interactions, schools create environments where both students and staff can thrive academically, socially, and emotionally.

For those seeking to examine deeper into the research and evidence supporting student wellbeing initiatives, the following academic papers provide valuable insights:

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/promoting-students-wellbeing#article","headline":"Student Wellbeing: Strategies for Promoting Mental Health in Schools","description":"Discover evidence-based approaches to promoting student wellbeing. Learn practical strategies for supporting mental health, building resilience, and...","datePublished":"2022-01-24T16:41:15.456Z","dateModified":"2026-01-26T10:09:32.212Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/promoting-students-wellbeing"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/696a1848bde78487fd84425e_696a18471dd92ab244277545_promoting-students-wellbeing-infographic.webp","wordCount":1624},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/promoting-students-wellbeing#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"Student Wellbeing: Strategies for Promoting Mental Health in Schools","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/promoting-students-wellbeing"}]},{"@type":"FAQPage","mainEntity":[{"@type":"Question","name":"Why Does Student Wellbeing Impact Academic Performance?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Student wellbeing directly affects academic performance because anxiety, stress, and emotional dysregulation reduce cognitive capacity for learning, compromising working memory, attenti on, and higher-order thinking skills. Conversely, students who experience academic success develop greater confidence, resilience, and motivation, creating a positive cycle where wellbeing and learning reinforce each other."}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What Are the Three Levels of School Wellbeing Support?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"The Public Health England model describes wellbeing support at three levels: Universal (for all students) includes positive school climate and social-emotional skill building; Targeted (for some students) provides additional support for at-risk groups; and Specialist (for few students) offers intensive interventions. This tiered approach ensures all students receive foundational support while those with greater needs access appropriate additional help."}},{"@type":"Question","name":"How Can Teachers Create a Mentally Healthy Classroom Environment?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Teachers can create a supportive classroom by establishing predictable routines, building positive relationships with all students, and developing a culture where mistakes are viewed as learning opportunities. Key strategies include greeting students at the door, using inclusive teaching practices that accommodate different learning styles, and maintaining consistent expectations while showing flexibility for individual needs."}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What Are the Warning Signs of Poor Student Mental Health?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Warning signs include sudden changes in behaviour such as withdrawal from friends, declining academic performance, increased irritability, difficulty concentrating, changes in sleep or appetite, expressing feelings of hopelessness or worthlessness, and physical symptoms such as headaches or stomach aches. Being alert to these signs and responding with empathy and appropriate support can significantly improve outcomes for students experiencing mental health challenges."}},{"@type":"Question","name":"How Can Schools Support Teacher Wellbeing?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Prioritising teacher wellbeing is crucial for creating a sustainable and supportive school environment. Schools can implement strategies such as workload management, access to professional development on self-care and stress management, creating supportive staff communities, and ensuring access to mental health resources. Recognising and addressing the pressures teachers face is vital for promoting both teacher and student wellbeing."}},{"@type":"Question","name":"How Can Schools Measure and Monitor Student Wellbeing Effectively?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Effective measurement of student wellbeing requires a multi-dimensional approach that captures both quantitative data and qualitative insights. Schools can implement regular wellbeing surveys using validated tools such as the Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale, alongside observational assessments that track behavioural indicators like attendance patterns, peer interactions, and engagement levels. Research by Seligman and colleagues on positive psychology demonstrates that measuring factors"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"How Can Schools Engage Parents in Supporting Student Mental Health?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Effective parent engagement in student mental health requires schools to move beyond traditional communication methods and establish genuine partnerships built on trust and shared understanding. Research by Joyce Epstein demonstrates that when families are actively involved in their children's wellbeing, students show improved emotional regulation and academic outcomes. Schools can creates this collaboration by providing parents with accessible mental health literacy , including information abou"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What Should Be Included in a Whole-School Mental Health Policy?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"A comprehensive whole-school mental health policy should establish clear frameworks for prevention, early intervention, and support across all areas of school life. Research by Kathryn Weare emphasises that effective policies integrate mental health considerations into curriculum planning, staff training protocols, and student support systems. Essential components include explicit procedures for identifying at-risk students, referral pathways to appropriate services, and guidelines for creating "}},{"@type":"Question","name":"How Should Schools Respond to Mental Health Crises?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Effective crisis intervention requires schools to establish clear, evidence-based protocols that prioritise immediate safety whilst connecting students with appropriate support. Research by Suldo and colleagues demonstrates that schools with structured response frameworks significantly improve outcomes during mental health emergencies. These protocols should include immediate risk assessment procedures, defined roles for staff members, and streamlined pathways to professional mental health servi"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"How Do Mental Health Strategies Differ Across Age Groups?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Mental health strategies must be carefully tailored to developmental stages, as the cognitive and emotional needs of primary pupils differ substantially from those of secondary students. Primary-aged children benefit from concrete, structured approaches that focus on emotional vocabulary building and routine establishment. Research by Marc Brackett demonstrates that emotional literacy programmes at this age create foundational skills for lifelong wellbeing, with activities like feeling wheels an"}}]}]}